CAD-Integrated Automatic Gearbox Design with Evolutionary Algorithm Gear-Pair Dimensioning and Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm-Driven Bearing Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

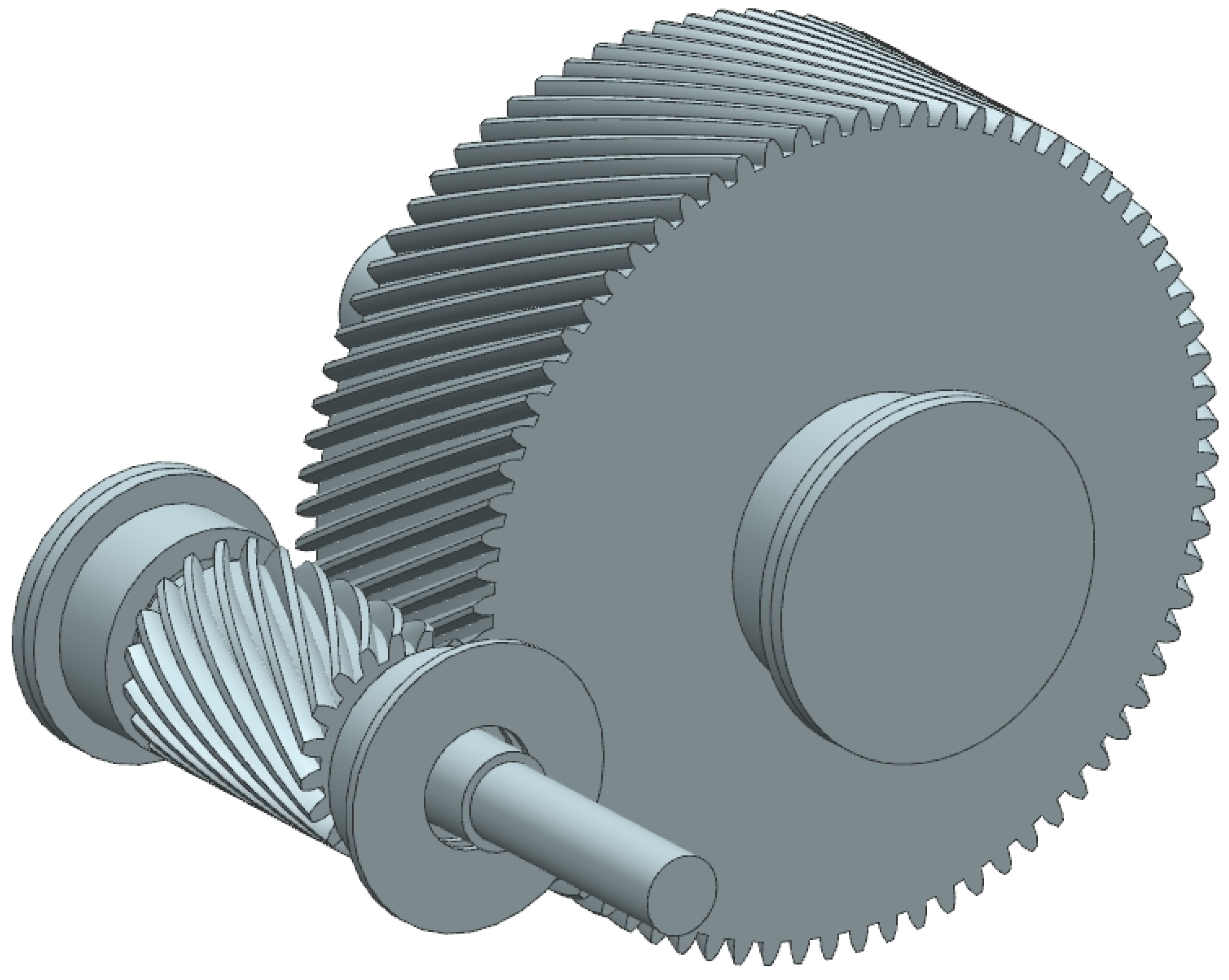

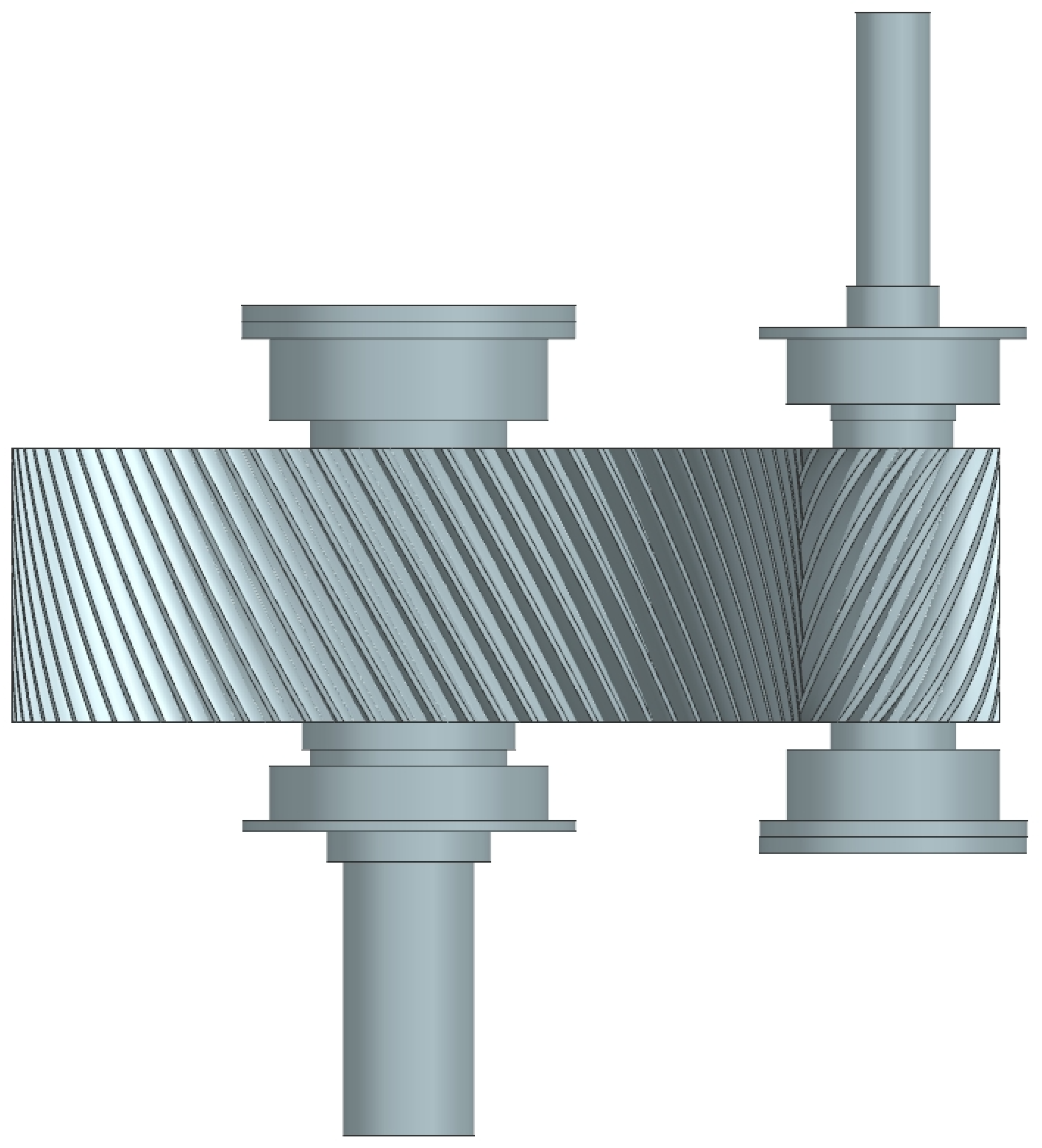

1.2. Aims of the Paper

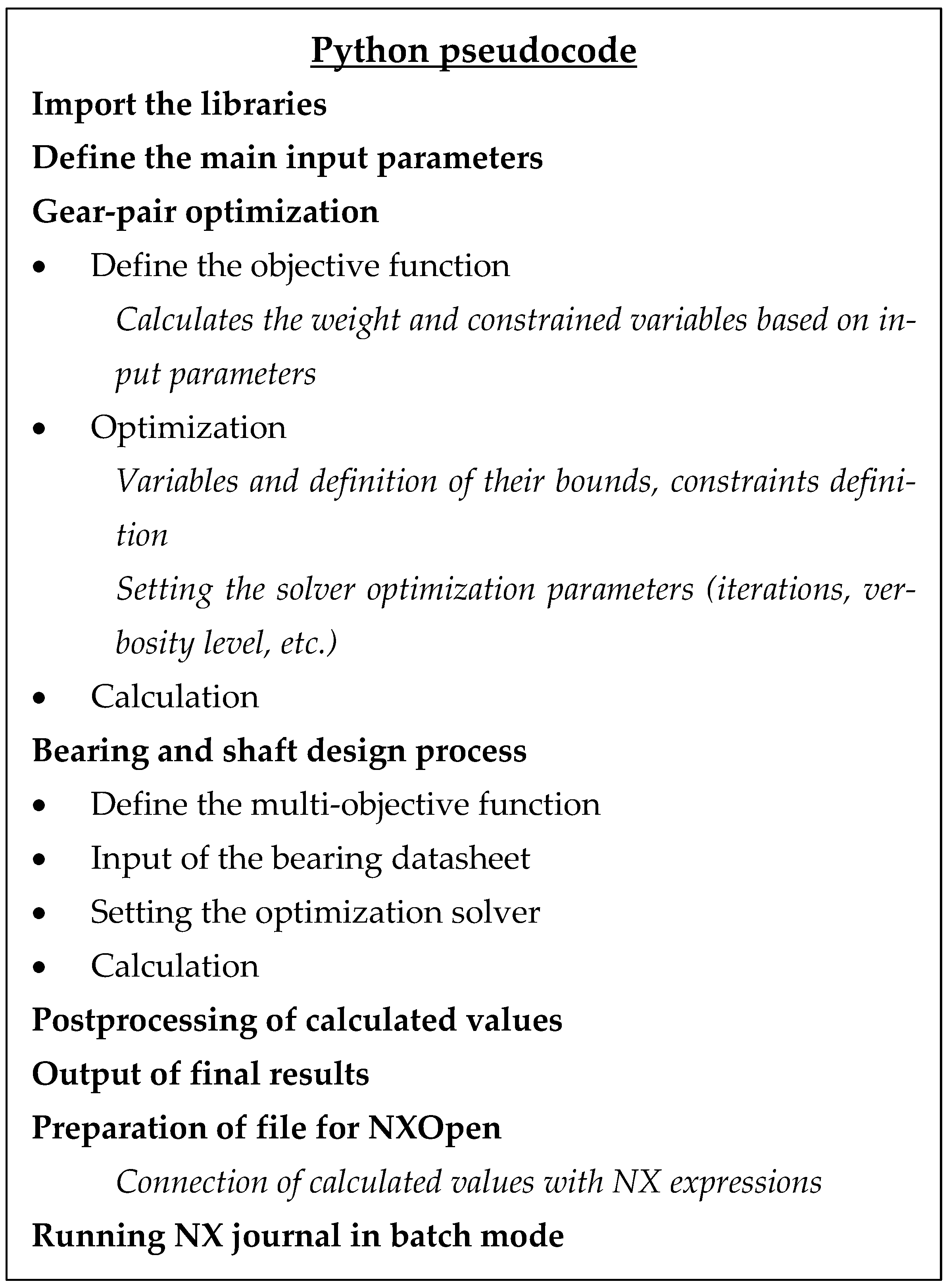

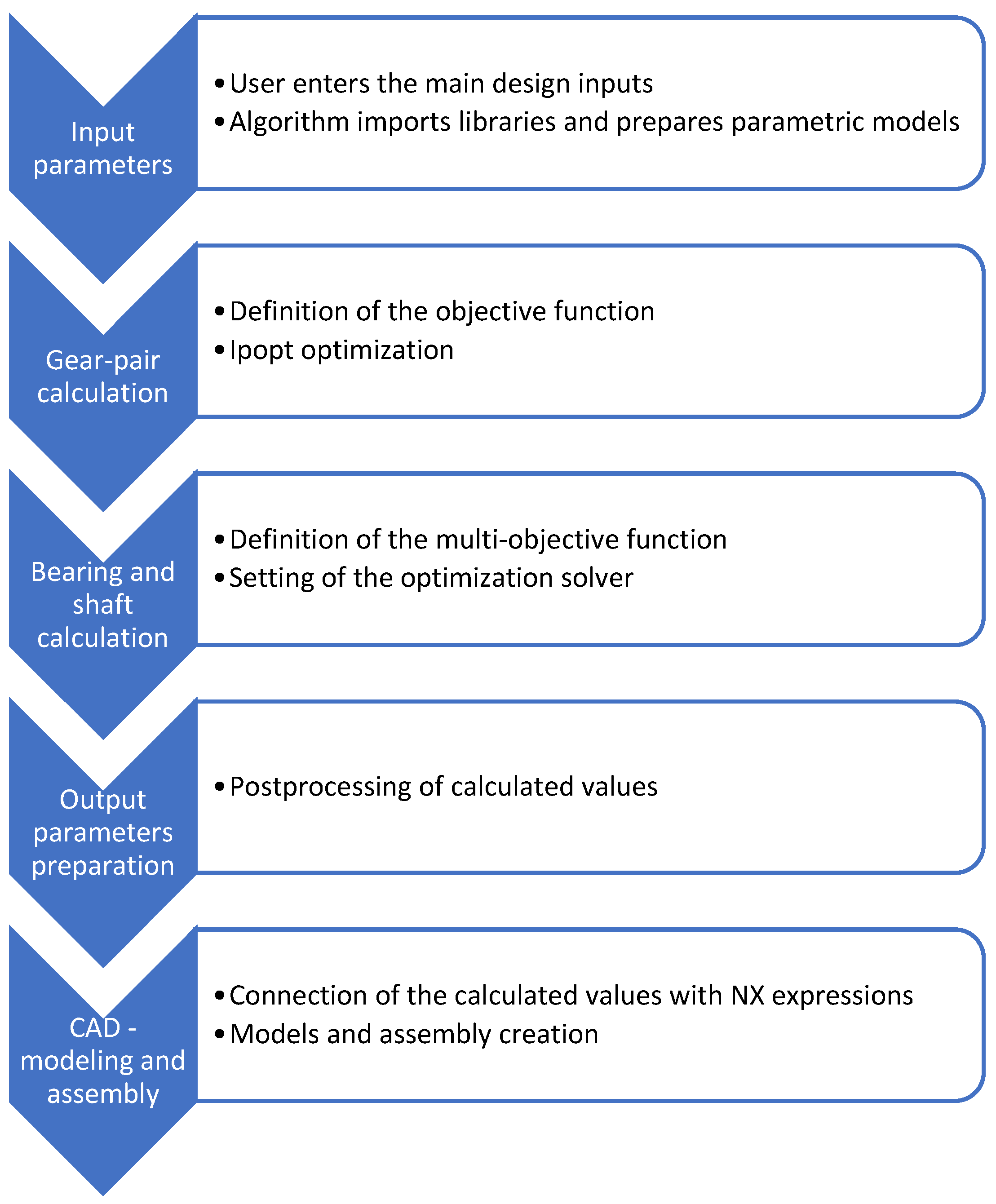

2. Methodology

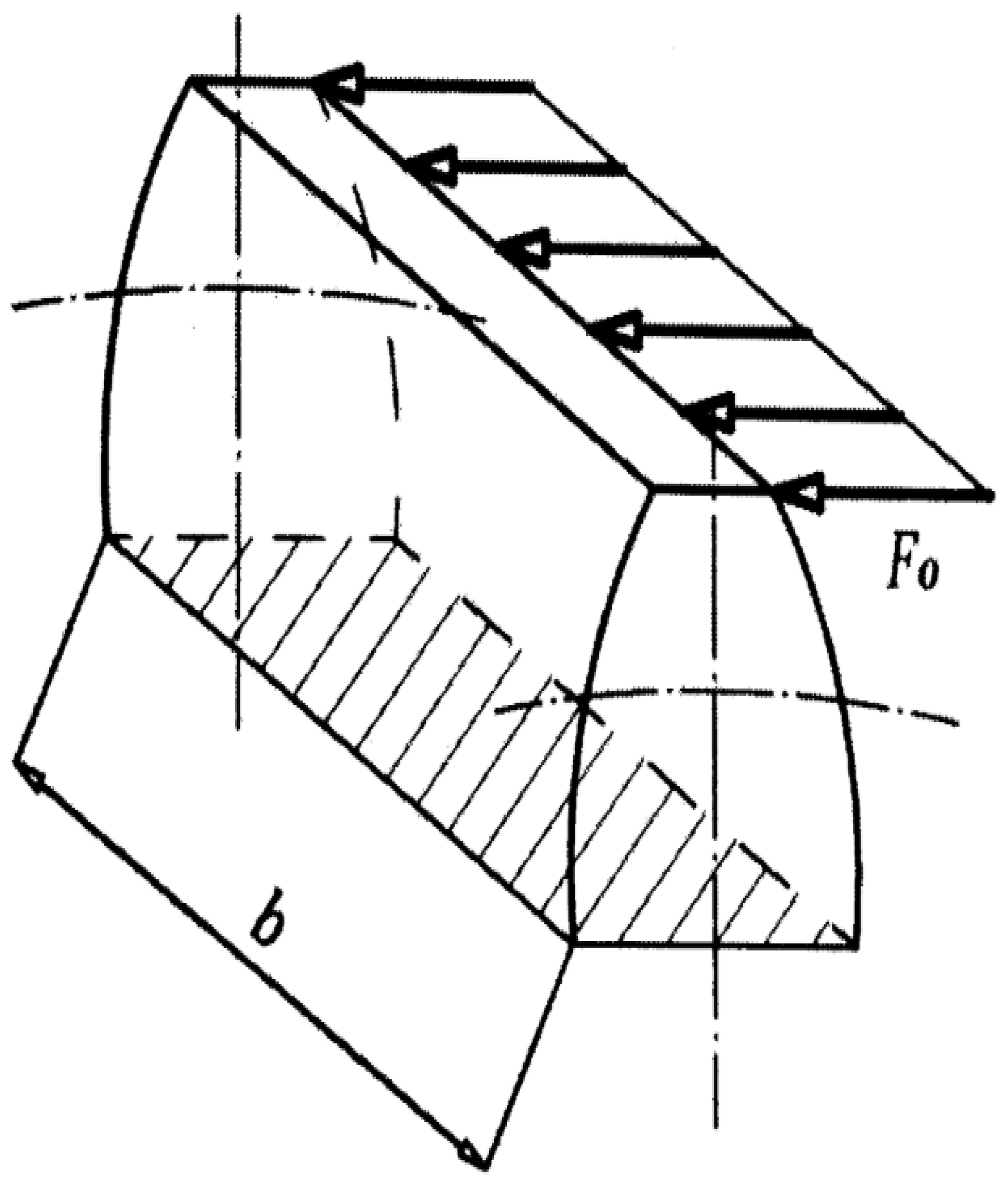

2.1. Gear Dimensioning

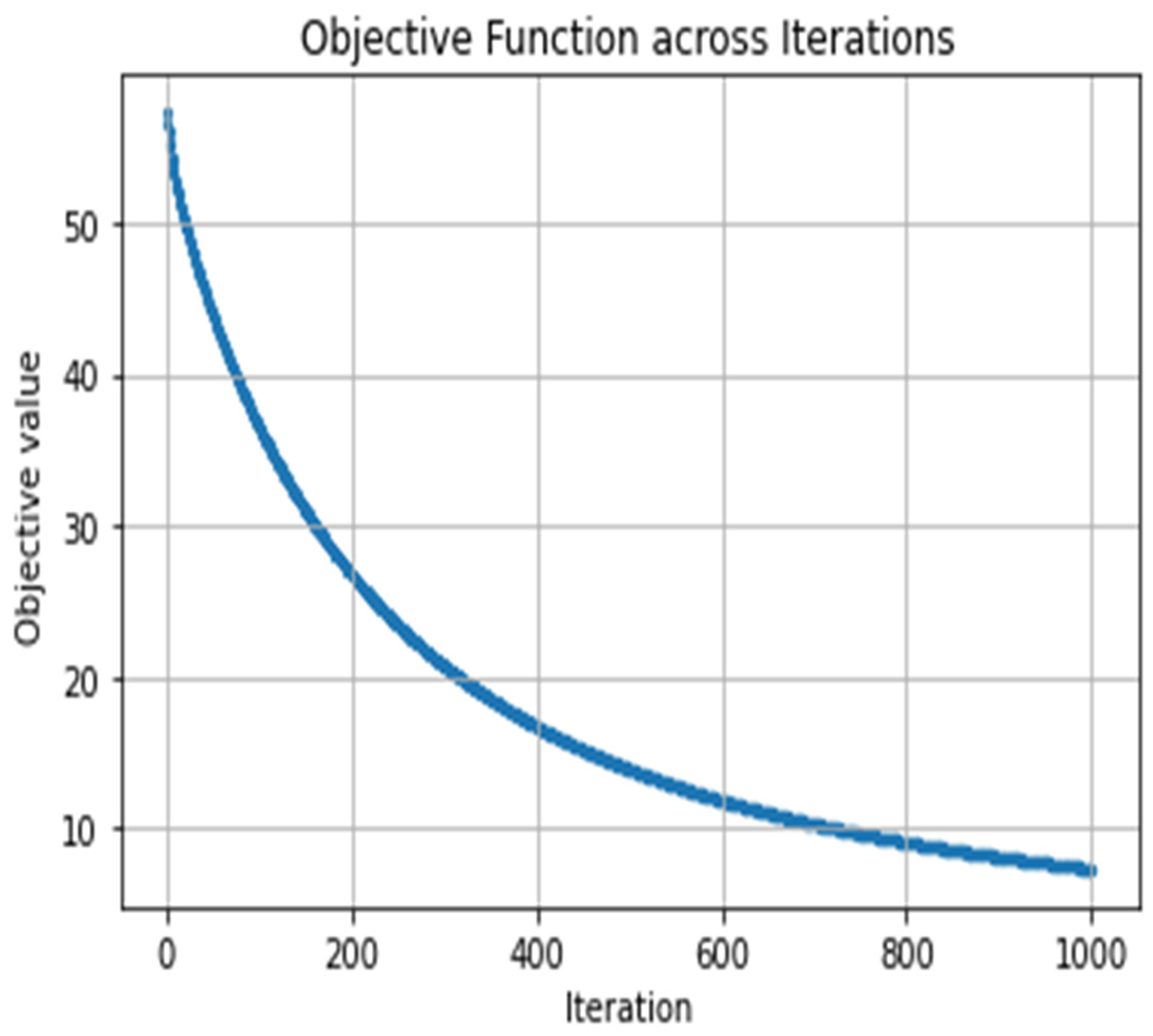

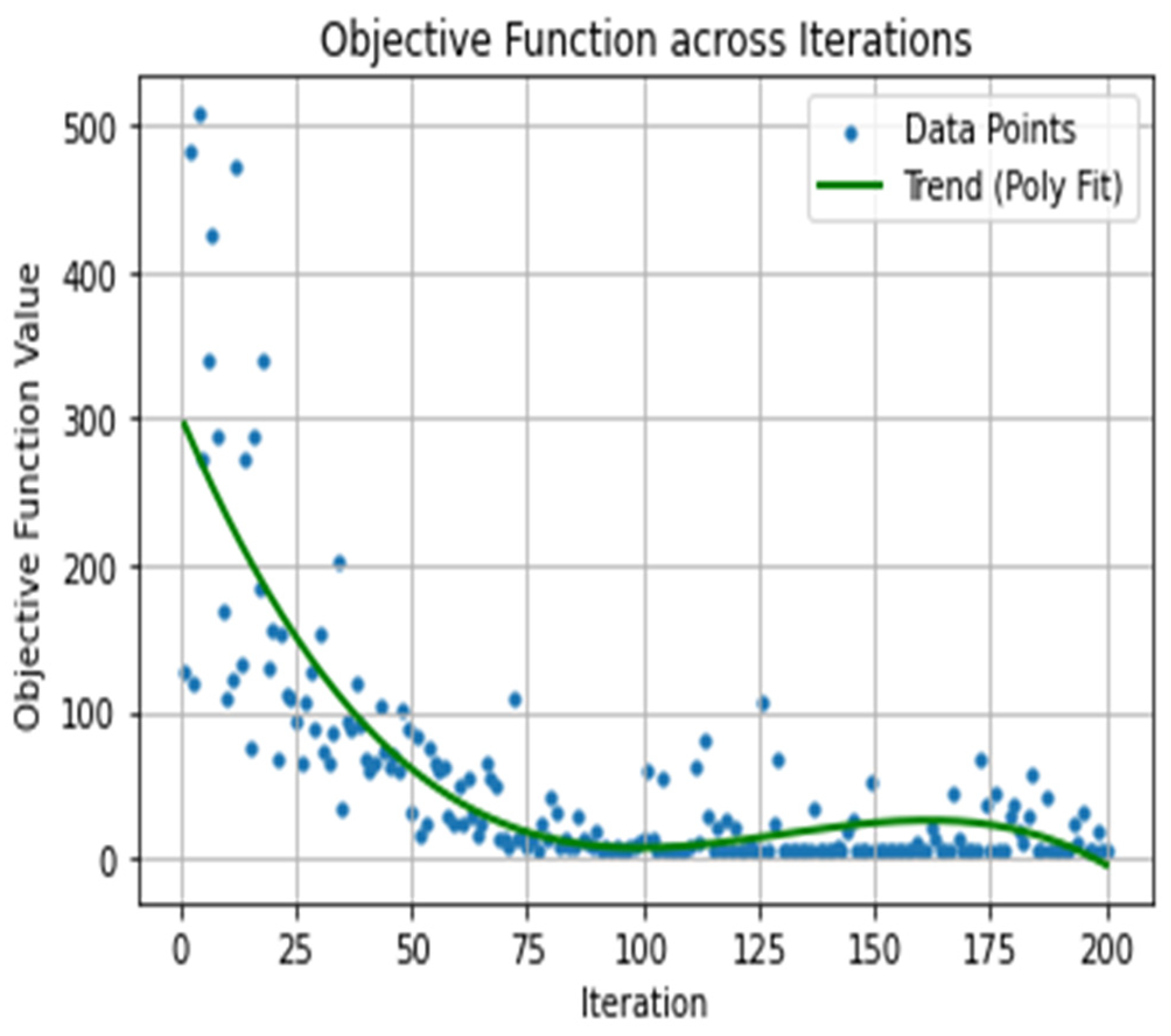

2.2. Ipopt

3. Choosing the Bearings

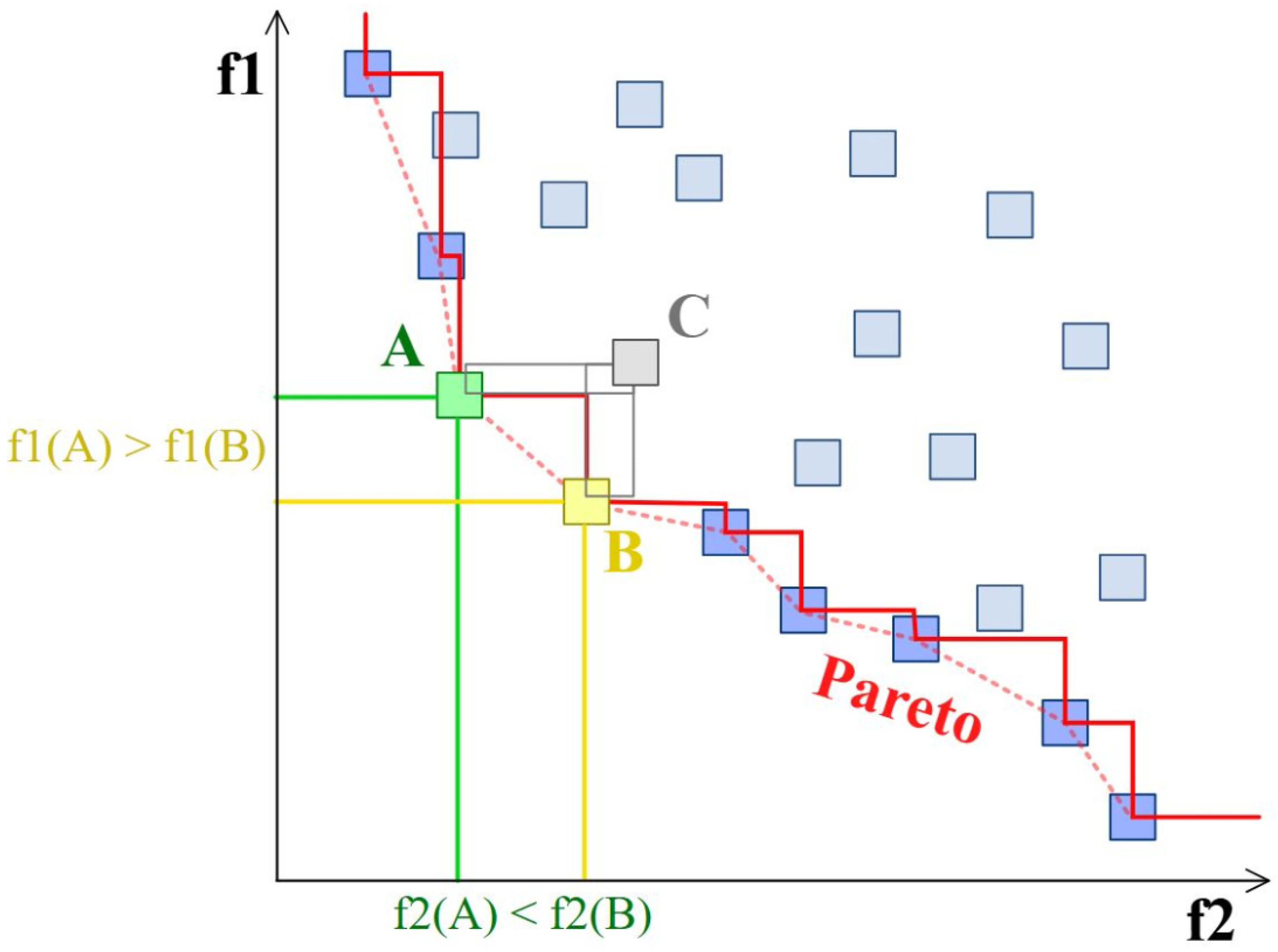

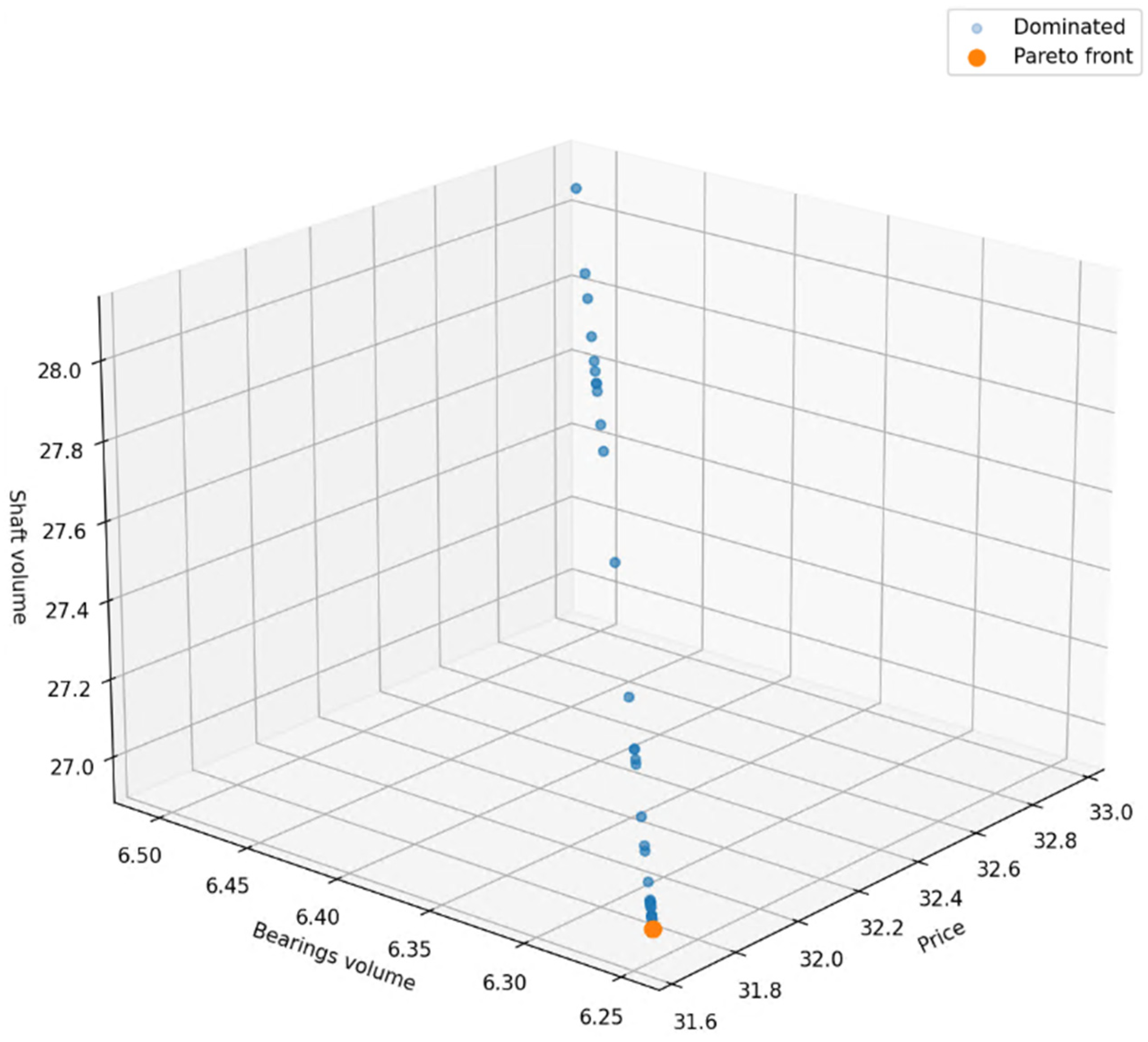

3.1. Application of the NSGA-II Algorithm on Bearing Evaluation

3.2. Optimization Process

4. Connection Between Python and Siemens NX

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| NSGA-II | Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm |

| EAs | Evolutionary Algorithms |

| Ipopt | Interior Point OPTimizer |

| GVF | Gas Void Fraction |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes Equations |

| GAFR | Genetic Algorithm For Features Recognition |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| MA | Moving Average |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

References

- Zelinka, I. Evoluční Výpočetní Techniky: Principy A Aplikace; BEN—Technická Literature: Praha, Czech Republic, 2009; ISBN 978-80-7300-218-3. [Google Scholar]

- Weise, T. Global Optimization Algorithms—Theory and Application; Free Software Foundation: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hoseiniasl, M.; Fesharaki, J. 3D Optimization of Gear Train Layout Using Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2020, 6, 823–840. [Google Scholar]

- Gologlu, C.; Zeyveli, M. A genetic approach to automate preliminary design of gear drives. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 57, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabi, S.; Fesharaki, J.; Yazdipoor, M. Gear train optimization based on minimum volume/weight design. Mech. Mach. Theory 2014, 73, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.; Ramkumar, P.; Shankar, K. Multi-objective optimization of the two-stage helical gearbox with tribological constraints. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 138, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liao, D. The Elite Multi-parent Crossover Evolutionary Optimization Algorithm to Optimum Design of Automobile Gearbox. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computational Intelligence, Shanghai, China, 7–8 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mendi, F.; Başkal, T.; Boran, K.; Boran, F. Optimization of module, shaft diameter and rolling bearing for spur gear through genetic algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 8058–8064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swantner, A.; Campbell, M. Topological and parametric optimization of gear trains. Eng. Optim. 2012, 44, 1351–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, M.; Rossit, D.A.; González, B.; Frutos, M. Proposal and Comparative Study of Evolutionary Algorithms for Optimum Design of a Gear System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 3482–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, E.B.; Changenet, C.; Bruyère, J.; Rigaud, E.; Perret-Liaudet, J. Multi-objective optimization of gear unit design to improve efficiency and transmission error. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 171, 104499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustynenko, O.; Bondarenko, O.; Serykov, V. Solving the Problem of Optimal Design for a Two-Stage Reducer by using a Modified Evolutionary Algorithm. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences 317, 7th International BAPT Conference “Power Transmissions 2020”, Borovets, Bulgaria, 10–13 June 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, Y.; Kulkarni, M.S. Multi-objective optimization with solution ranking for design of spur gear pair considering multiple failure modes. Tribol. Int. 2023, 180, 108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonisoli, E.; Velardocchia, M.; Moos, S.; Tornincasa, S.; Galvagno, E. Gearbox Design by Means of Genetic Algorithm and CAD/CAE Methodologies. In Proceedings of the SAE 2010 World Congress & Exhibition, Detroit, MI, USA, 13–15 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, C. Shape Optimization of Helico-axial Multiphase Pump Impeller Based on Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2009 Fifth International Conference on Natural Computation, Tianjian, China, 14–16 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, I.; Case, K.; Wood, R. Genetic algorithms in computer-aided design. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 117, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Tigga, A.; Kumar, A. Feature extraction from large CAD databases using genetic algorithm. Comput.-Aided Des. 2005, 37, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryazanov, A. Automated 3D modeling of working turbine blades. Russ. Eng. Res. 2016, 36, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirra, G.; Pugnale, A. Exploring a Design Space Of Shell and Tensile Structures Generated by AI from Historical Precedents. J. Int. Assoc. Shell Spatial Struct. 2022, 63, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Cao, R.; Li, Z.; Zang, Y.; Sun, L. Deep3DSketch-im: Rapid high-fidelity AI 3D model generation by single freehand sketches. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2024, 25, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Sinha, S.; Sheikh, T.; Stricker, D.; Ali, S.; Afzal, M. Text2CAD: Generating Sequential CAD Models from Beginner-to-Expert Level Text Prompts. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 7552–7579. [Google Scholar]

- Krátký, J.; Krónerová, E.; Hosnedl, S. Obecné Strojní Části 2 Základní a Složené Převodové Mechanismy, Plzeň: Západočeská Univerzita v Plzni; University of West Bohemia: Pilsen, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shigley, J.E.; Budynas, R.; Nisbett, K. Shigley’s Mechanical Engineering Design; Mcgraw-Hill Series in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ČSN 01 4607; Ozubená Kola Čelní s Evolventním Ozubením. Základní Profil. Česká Agentura pro Standardizaci: Prague, Czech Republic, 1978.

- Bynum, M.L.; Hackebeil, G.; Hart, W.E.; Laird, D.C.; Nicholson, L.B.; Siirola, J.D.; Watson, J.; Woodruff, L.D. Pyomo—Optimization Modeling in Python; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nocedal, J.; Wächter, A.; Waltz, R. Adaptive barrier strategies for nonlinear interior methods. SIAM J. Optim. 2009, 19, 1674–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächter, A. An Interior Point Algorithm for Large-Scale Nonlinear Optimization with Applications in Process Engineering; Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wächter, A.; Biegler, L. On the implementation of a primal-dual interior point filter line search algorithm for large-scale nonlinear programming. Math. Program. 2006, 106, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächter, A.; Biegler, L. Line search filter methods for nonlinear programming: Local convergence. SIAM J. Optim. 2005, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächter, A.; Biegler, L. Line search filter methods for nonlinear programming: Motivation and global convergence. SIAM J. Optim. 2005, 16, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ČSN ISO 281 (02 4607); Valivá Ložiska—Dynamická Únosnost a Trvanlivost. Česká Agentura pro Standardizaci: Prague, Czech Republic, 2008.

- ISO 281:2007; Rolling Bearings—Dynamic Load Ratings and Rating Life. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Dréo, J. 9 May 2006. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Front_pareto.svg (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: Nsga-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NXjournaling. Beginning Journaling Using NX Journal. Available online: https://nxjournaling.com (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Siemens. Getting Started with NX Open; Siemens: Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Constraint | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Module | >0.3 |

| 2 | Gear width | >10 mm |

| 3 | Number of teeth—Gear1 | >17 |

| 4 | Number of teeth—Gear2 | >17 |

| 5 | Tooth root stress (actual) (according to the Bach formula) | <10 MPa |

| 6 | Gear width | |

| 7 | Gear width | >10 m |

| 8 | Gear width | <30 m |

| Name | Constraint | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shaft diameter = Bearing inner diameter | |

| 2 | Shaft stress | <60 MPa |

| 3 | Bearing durability | >1,000,000 revolutions |

| 4 | Reference speed limit of bearing | >actual speed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fait, D. CAD-Integrated Automatic Gearbox Design with Evolutionary Algorithm Gear-Pair Dimensioning and Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm-Driven Bearing Selection. Machines 2026, 14, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010036

Fait D. CAD-Integrated Automatic Gearbox Design with Evolutionary Algorithm Gear-Pair Dimensioning and Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm-Driven Bearing Selection. Machines. 2026; 14(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleFait, David. 2026. "CAD-Integrated Automatic Gearbox Design with Evolutionary Algorithm Gear-Pair Dimensioning and Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm-Driven Bearing Selection" Machines 14, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010036

APA StyleFait, D. (2026). CAD-Integrated Automatic Gearbox Design with Evolutionary Algorithm Gear-Pair Dimensioning and Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm-Driven Bearing Selection. Machines, 14(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010036