1. Introduction

There is a growing need to automate the continuous operation and management of various systems. We often call these self-adaptive systems if they are built around a controller that manages the system and its resources. A controller generates actions to maintain such a system within expected quality ranges based on monitored system data as the input. Self-adaptive systems are widely used in environments where manual adjustment is neither feasible nor reliable. This ranges from industrial production machines or power management systems to fully softwareised environments such as cloud applications, which are all examples of virtualised or cyber-physical systems that are suited to be governed by a control-theoretic solution to continuously and automatically adjust the system [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In particular, resources used by a complex system can be dynamically adjusted and need to ensure dedicated quality management.

Today, we can observe that automation of control also extends to its construction. For instance, during development, AI techniques can be employed if a sufficient amount of data is available to generate the models that form the core functions of this self-adaption [

5]. Thus, we focus here on the automated construction of controllers and their required quality properties, and not on the application systems that these controllers control.

Performance or robustness are the most frequent quality concerns that can be found for self-adaptive controller-managed systems, i.e., controllers monitor and analyse the target system in terms of the dynamic properties of the latter. Consequently, these quality concepts for the system would need to be reinterpreted for a controller as a software-based system. Our objective here is to conduct a wider review of quality metrics beyond these two, also including fairness, sustainability, and explainability, which are common concerns for AI techniques such as machine learning (ML) in general, as part of a responsible AI concern, but need a specific investigation for applications to the controller context here.

Machine learning (ML) is a good example of a construction mechanism to motivate the need for this investigation. In the ML model construction, accuracy, precision, and recall are generally used to assess the quality of prediction or classification models. However, the construction causes concerns related to the responsible AI concept that aims at the fairness, transparency, explainability, and ethical behaviour of these machine-generated controllers. The quality concerns of reinforcement learning (RL) as a widely used mechanism for controller construction have been investigated for specific concerns [

6,

7,

8]. Two challenges arise: firstly, the construction outcome looks different for software controllers than for other typical ML applications, and secondly, the quality management of these controllers themselves needs to be automated, what is often referred to as DevOps automation in the software domain [

9,

10].

In this paper, we address a coherent system of broad principles and practices to design and manage controllers for self-adaptive systems. Specifically, we present a catalogue of classified controller quality metrics as the main contribution to controller construction. To frame this metrics catalogue, we introduce a reference architecture for controllers within a quality management framework. This is often considered as part of a continuous change process in a DevOps-style (or also referred to as AIOps if the software operations process is AI-controlled) that allows for continuous quality monitoring to mediate quality deficiencies. Since change is ubiquitous, we address change in a two-layered quality management framework covering the system and the controller layer.

Our method is based on (i) a review of survey papers as secondary contributions that we systematically selected to cover AI and controller perspectives and (ii) a further consideration of individual primary solution contributions for the specific aspects from machine learning to resource management to change detection in order to supplement the survey findings and define our framework, taking the state-of-the-art into account. A two-layered feedback loop has already been proposed as a natural consequence of mapping quality control into a continuous feedback loop to monitor quality [

11,

12]. We based this work on the two-layered loop [

13] and used the review papers covering their respective focal concern to form a coherent conceptual framework here that provides a comprehensive set of metrics to allow this two-layered controller loop to be realised. While different controller construction mechanisms are covered, due to the popularity and relevance of reinforcement learning and control theory as established mechanisms, these are specifically singled out to provide insights into the potential implementation of the proposed results.

For automatically generated controllers, their automated continued quality management becomes an important concern. While metrics for qualities of systems that a controller manages have been explored, our investigation specifically focuses on AI-related properties of AI-constructed controllers. The novelty lies in the definition of common qualities for AI-generated controller software, rather than the quality metrics that the system under observation is meant to maintain that have been proposed so far. Furthermore, the AI qualities are combined into a comprehensive catalogue with specific definitions for controllers, which has also not been done.

The paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, we review related work. In

Section 3, we present a reference architecture as the first contribution component that frames the outcome.

Section 4 provides an overview of reinforcement learning and control theory as two prevalent techniques to give a more concrete context.

Section 5 then defines a metrics catalogue for controllers.

Section 6 discusses the findings and presents a use case. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper with some future work indications.

2. Related Work

In this section, we discuss the controller quality perspective covering individual metrics but also general quality frameworks. The detection of quality change is a central task.

Traditional system-level quality metrics such as performance or robustness have been widely investigated as the goal of controllers. Performance is interpreted often as latency or the response-time behaviour of a system or robustness during the disturbances caused in the system execution and monitoring. In contrast, we focus here only on the quality metrics of the controller itself. Here, we consider specifically AI techniques for controller construction and will consequently propose a catalogue of AI-related metrics, which has not yet been presented in a comprehensive framework [

14,

15,

16].

A range of individual quality metrics have been investigated, in particular for the construction of controllers employing reinforcement learning, which is a widely used technique.Reinforcement learning (RL) is a suitable approach to derive solutions for control systems. The work in [

7] covers the link between RL performance and the notion of stability that stems from the control area. Ref. [

8] is a good example of an RL application for a control problem that requires high degrees of performance. Robustness and performance are covered in [

6] to cover recent deep reinforcement learning trends. Robustness is also investigated in [

17]. The ability to deal with disturbances from the environment is often seen as an important property of control systems that act in environments with a lot of uncertainty.

However, beyond classical performance metrics, recently in the wider ML and AI context other concerns such as explainability or sustainability have been looked at. Attention has been given to these from the perspective of the environment and the users and/or subjects of a solution. Another concrete direction is the fairness of the solution. Ref. [

18] looks at this in the context of Markov processes, which define the central probabilistic behaviour of control systems. While explainability has now been widely recognised for prediction and classification approaches, RL has received less attention. One example is [

19], which reviews explainability concerns for RL. A survey of this aspect is provided by [

20]. Explanations for self-adaptive systems are addressed in [

21,

22]. As a wider societal concern that also has a cost impact for users, sustainability through, for example, energy and resource consumption is also investigated [

23].

In [

24], RL is discussed in the context of a MAPE-K (Monitor, Adapt, Plan and Execute stages based on a shared Knowledge component) loop integration. Meta-learning refers to the need to relearn if adaptations are required to adjust to drift. A meta policy can deal with adaptation to new tasks and environmental conditions. Here, specifically, the cost of RL is considered, since meta-learning should work with small volumes of data and quick convergence.

If a set of metrics needs to be implemented, i.e., needs to be monitored, analysed, and converted into recommendations or remedial actions if quality concerns are detected, then a systematic engineering approach is needed that explains the architecture of the system in question and devises a process for quality management. Ref. [

25] provides an overview of the AutoML domain, which is a notion to cover automated approaches to managing the AI model creation and quality management. Another term used in this context is AI engineering. For instance, Ref. [

26] approaches such a generic framework from a software engineering perspective, aiming to define principles that define a systematic engineering approach. Similarly, Ref. [

5] investigates common engineering practices and how they change in the presence of ML.

In [

27], a three-layered reference architecture based on the MAPE-K pattern is presented that separates dynamic monitoring feedback (for managing context information for the monitoring and adaptation setting), adaptation feedback (to control the adaptive behaviour of the target system in terms of functional and non-functional properties), and objectives feedback (to control changes to the adaptation goals such as settling time or stability).

Model checking of controller models is the concern in [

28]. The application system is managed in terms of throughput, resource usage, cost, and safety, as these systems are largely impacted by sensor failure or response time deficiencies. The controller is assessed in terms of liveness and safety properties using the UPPAAL model checker. The solution is embedded in a comprehensive process model for controller construction, where the verification of controller models, e.g., in terms of possible paths of the four MAPE processing steps, is most relevant to our perspective.

Our objective is to monitor quality and to react to changes and unexpected behaviour or uncertainties, which are pointed out in [

29] as important concerns. The distinction between drift and anomaly as central forms of unexpected behaviour—and also other concepts such as rare events or novelty detection—is often not clear, as Ref. [

30] shows with a review of connected concepts. We will provide formal definitions later after motivating the metrics selection. There we also refer in more detail to concrete techniques. Thus, we introduce only some selected review papers here. Several drift detectors have been proposed, as surveyed by Refs. [

31,

32]. Examples of drift analysis are found in [

33,

34]. For instance, Ref. [

33] states that different diversity levels in an ensemble of learning machines are required to attain better accuracy, i.e., different classifiers are used. Another example is [

34], which uses Spiking Neural Networks for drift detection combined with a notion of evolution to detect changes. Equally, for anomaly detection, the number of proposed solutions is large, as the review in [

35] shows. We will later introduce anomaly detection techniques specific to our context of continuous sensor data in a technical systems setting.

Another layered architecture is presented in [

36], where the lower layer as usual deals with the managed system adaptation. The upper layer, called the lifelong learning loop, focuses on changes in ML-generated controllers. In particular, concept drift is addressed here as a cause of the needed adaption of the controller to changing requirements. The solution is knowledge management, e.g., encoding unlabelled data and detecting new tasks to deal with changes.

In summary, we can note that many controller quality frameworks exist, but that a comprehensive analysis of AI properties has not been carried out. Reinforcement learning is the prevalent ML technique used—which is the reason why we focussed our investigation of this construction technique. However, the reviewed surveys and other papers show that only aspects such as robustness or performance are addressed for controller constructions. Explainability or fairness are not well covered for RL-approaches in general and are only investigated for more general AI-constructed software contexts. The quality of RL-constructed controllers is specifically a research gap. These latter quality concerns in particular need a formalisation, which we will provide later on in

Section 5 after introducing a reference architecture and RL basic to frame these concerns in

Section 3 and

Section 4.

3. Reference Architecture for Controller Quality

Our focus is self-adaptive systems, specifically the construction and architecture of controllers that deal with quality problems and adapt the resources used by the system.

3.1. State-of-the-Art and Motivation of Framework

The review of the state-of-the-art results in two concerns that have not been sufficiently addressed:

Firstly, relevant quality metrics are performance, robustness, fairness, explainability and sustainability, but these need to be adjusted to AI-constructed controllers;

Secondly, a systematic quality management framework is needed to embed these metrics into a coherent framework.

A respective framework consisting of metrics and a quality management process is needed to provide a systematic, quality-driven controller construction and management approach. The presented work provides core principles and practices in this context. The need to automate quality management of control is exacerbated by the fact that this context is about environments where a manual adjustment is neither feasible nor reliable.

Therefore, we need to identify and define quality criteria for the automation of system adaptation where AI is used to construct controllers.

3.2. Controller Quality Requirements

Run-time monitoring of critical systems is always important. Due to the utilisation of ML to construct software, there is no direct control by expert development engineers, and thus quality needs to be managed differently. This requires, for instance, explainability of the ML models to understand quality implications. Machine learning models are normally evaluated for their effectiveness, generally in terms of metrics such as accuracy, precision, and recall that capture the performance. Two challenges emerge for controllers and their quality:

The usual ML performance measures of accuracy, precision, and recall do not naturally apply for all construction methods, requiring a different notion of performance and also the need to take uncertainty and disturbances in the form of robustness in the environment into account;

To better judge the quality of controllers themselves, other concerns such as explainability, but also fairness or sustainability, are important.

What is effectively needed is an engineering approach for self-adaptation controllers, which is part of what is often called AI Engineering [

26]. We investigate this specifically for controller construction for self-adaptive software systems.

3.3. Resource Management and Motivational Example

We now return to ML and prediction and classification model accuracy examples and translate this to reinforcement learning and control theory and relevant quality concerns. A motivational use case is controllers for resource management [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41] that can be applied in virtualised and cyber-physical environments, e.g., cloud or IoT settings. Hong et al. [

42] review this for resource management. System adaption is required for the resource configuration, including the monitoring of resource utilisation and respective application performance and the application of generated rules for resource management to meet quality requirements [

12,

43,

44]. The rules adjust the resource configuration (e.g., size) to improve performance and other qualities. A prevalent example is RL, which employs a reward principle applicable in the self-adaptation loop to reward improvements and penalise deteriorations.

The problem shall be described using a concrete example:

The problem could be a resource controller for cloud adaptation. This could employ the following rule: if Workload > 80% then double (Resource-Size). The concrete problem is whether this rule is optimal and whether the recommendation space considered by the controller is complete.

The remediation can be an RL-generated controller that provides an actionable recommendation for a 60% workload as a verified test case. Then, this recommendation can be scaled up to 80%.

- -

The model could reward a good utilisation rate (e.g., 60–80%);

- -

The model could penalise costly resource consumption, e.g., high monetary costs for cloud resources or energy consumption.

Performance in this case would be determined the accuracy of how well the controllers maintain a 60–80% workload, or robustness would be determined by to what extent noise in the training data affects the controllers’ behaviour.

In particular, AI-driven controller generation requires proper quality monitoring and analysis of a defined set of comprehensive quality criteria. Furthermore, detected quality deficiencies need to be analysed as part of a root cause analysis. From this, suitable remedies need to be recommended and enacted.

3.4. Reference Architecture for Quality Management

The quality management of controller models is the challenge here. The accuracy or effectiveness against the real world could mean that a predictor predicts accurately or that an adaptor manages to effectively improve the system’s performance. However, as the above discussion shows, more than the traditional performance and cost improvement needs to be addressed. While discrimination is not a direct issue for software, a notion of technical fairness and aspects of accountability and explainability need to be dealt with.

Self-adaptive systems and the decision models at the core of respective controllers are suitable for AI-based creation due to the availability of monitoring and actuation data for training. The controller model aims to enact an action, e.g., to adapt resources in the edge, divert traffic in IoT settings, or instruct the machines that are controlled. This implements a dynamic control loop, governed by predefined quality goals [

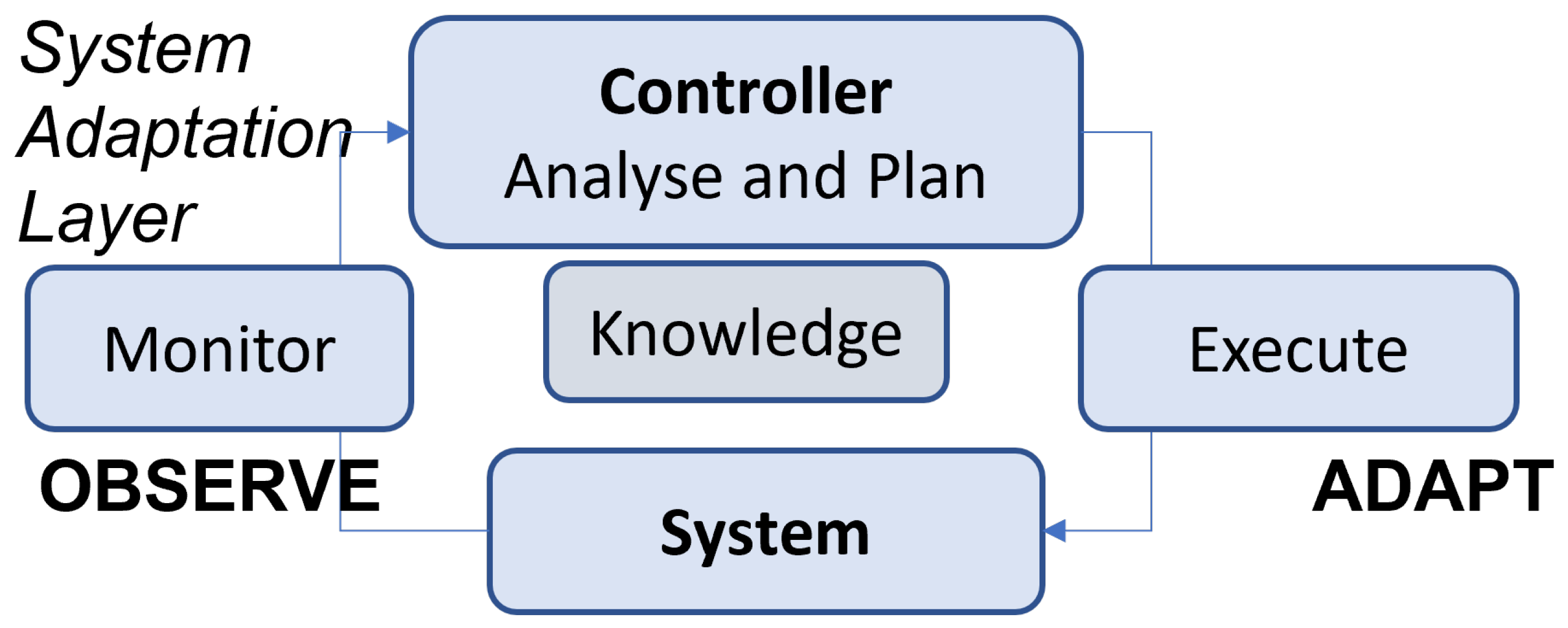

10]. These self-adaptive systems governed by a controller implement a feedback loop, see

Figure 1, following the MAPE-K architecture pattern. MAPE-K control loops provide a template for self-managing systems [

45]. The managed element is often part of a cyber-physical environment. The MAPE-K loop consists of four phases in the form of a continuous loop:

Monitor: The environment with the managed element is continuously monitored. The observed data can cover various data formats about the physical and digital environment. Usually, some form of aggregation or filtering happens.

Analyse: The current system situation based on the monitored observations is analysed. The reasoning can derive higher-level information that might result in a change or management request.

Plan: Based on a change request, a plan with corresponding management actions is created. The aim is actions that allow the managed element to fulfil its goals and objectives again if concerns have been identified. This can include basic decisions such as an undo or redo, but also complex strategies including structural modification and migration of the underlying system.

Execute: A change plan would be executed by an actuator in the operational environment of the managed element.

Knowledge as a key part of the control loop is shared between all phases. Relevant knowledge for these autonomic systems can range from topology information to historical logs to metrics definitions to management policies. This knowledge, or model, can also be continuously updated.

Figure 1.

Base system architecture—a controller loop based on the MAPE-K pattern with (M)onitor, (A)dapt, (P)lan, and (E)xecute stages based on a shared (K)nowledge component.

Figure 1.

Base system architecture—a controller loop based on the MAPE-K pattern with (M)onitor, (A)dapt, (P)lan, and (E)xecute stages based on a shared (K)nowledge component.

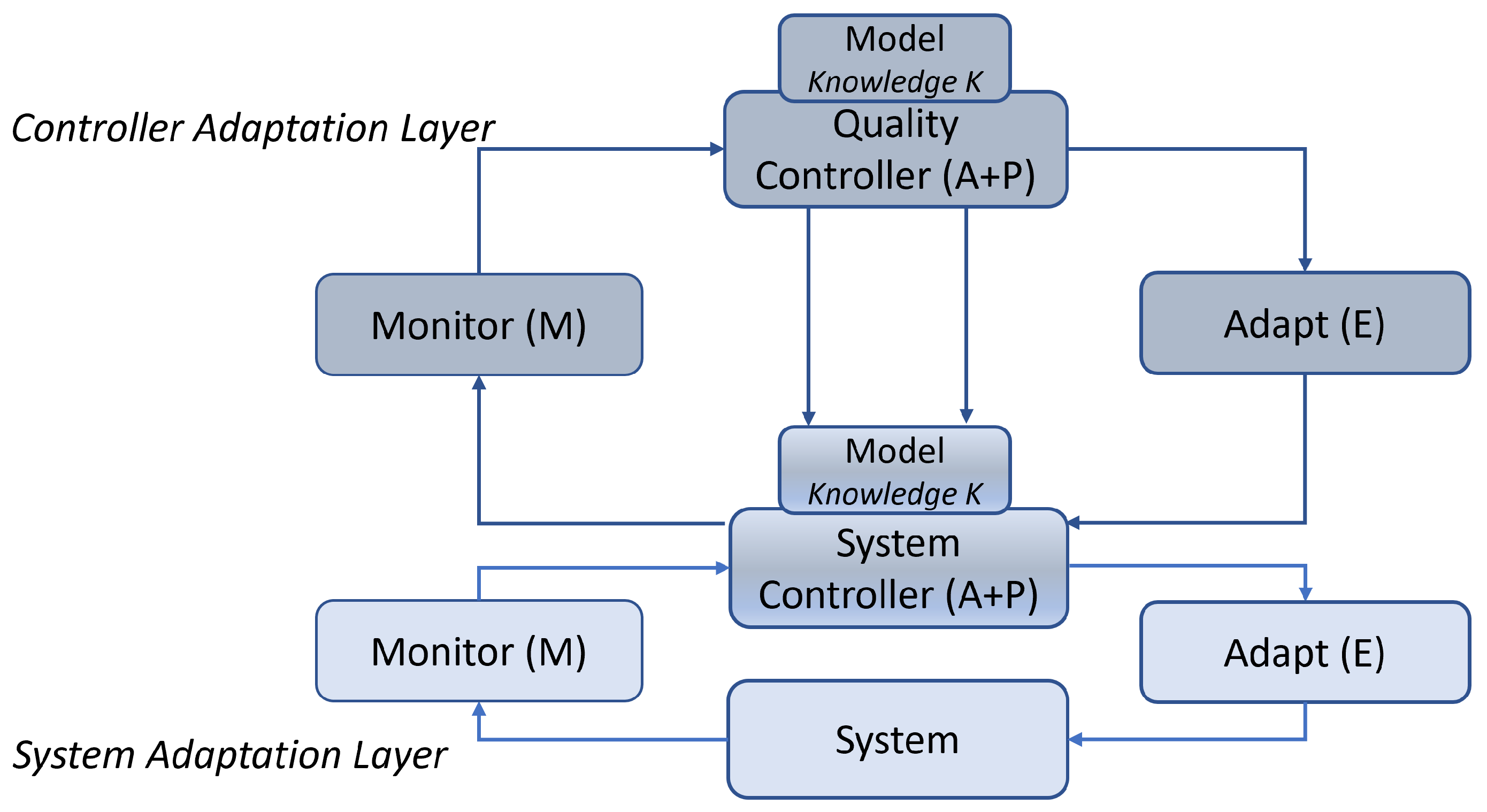

We propose a two-layered MAPE-K-based controller reference architecture, where the knowledge component K (the ‘model’) is the item of concern for the second layer, together with the full MAPE-K actions. The system is the item of concern for the first layer. The reference architecture provides a meta-learning layer that monitors several quality metrics, but also validates the metrics and their respective success criteria in a second loop—see

Figure 2. The lower layer (Layer 1) is a controller for self-adaptive systems. The upper layer (Layer 2) is an intelligent quality monitoring and analysis framework aligned with the requirements of a (generated) controller for self-adaptive systems.

Figure 2 builds on the MAPE-K loop in these two layers. The upper loop is the focus of this paper, but needs to take on board the lower layer’s behaviour.

We define controllers as a state–transition system of states

S, actions

A, a transition function

and a reward function

that allows us to measure the quality of the chosen action in a given state—see Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Controller structure—definition |

| States |

| Actions |

| Probabilistic transition function |

| Reward function |

3.5. Controller Quality Management at the Upper Layer

An important question concerns the automation of the upper loop. If full automation is the ultimate objective, this creates some challenges regarding metrics and their measurability and should thus guide the solution. These challenges are as follows: automate model construction, automate the model use and evaluation, and recommend a model learning configuration adjustment. The upper meta-learning loop design follows the MAPE-K pattern:

Monitor: We need reward functions for model quality, i.e., adaptor quality based on a range of metrics that are linked to the application system and its aspects—from data quality in the input (requiring robustness) [

46,

47] to sustainability (requiring lower cost and environment damage) as two examples.

Analyse: We need to implement an analysis consisting of problem identification and root cause analysis for model quality problems and feeding into explainability aspects through a (partial) dependency determination to identify which of the system factors would improve the targeted quality the most.

Plan/Execute: The solution would need to recommend and if possible also enact these recommendations. For example, a rule update for the cloud adaptor could be recommended, with model recreation being done. This could in very concrete terms be a readjustment of training data size or ratio. Also, remedial actions for an identified root cause can be considered.

This upper loop would implement a meta-learning process, which is a learning process to adapt the controller through a continuous testing and experimentation process. We call this the knowledge-learning layer.

In order to develop a solution, we follow the Engineering Research guidelines proposed by the ACM SIGSOFT Empirical Standards committee as the methodological framework [

48]. In [

10], a systematic construction process based on the identification of goals and actuation needs, resulting in suitable models and the final controller, is discussed. To frame the controller design, we use the MAPE-K architecture pattern for system adaption.

5. Controller Quality Metrics

The aim is to automatically monitor and analyse the quality of the system controller for the lower layer, as far as possible, using a defined set of metrics. This metrics set takes the controller construction into account. Our selection and definition rationale below is given for an RL-constructed controller type. In this section, we introduce our metrics framework, starting with a conceptual outline, before defining each of the five selected metrics in more detail.

5.1. Method

Two activities are needed for this metrics framework: the selection of suitable metric categories and the precise definition of the selected metrics.

For the first step, we systematically surveyed review articles covering common bibliographic databases such as Scopus, Google Scholar, and IEEE Xplore. We used suitable search terms both for AI-generated software in general (AI, ML, and RL as acronyms and in their extended term variant) and specific controller-oriented ones (controller, self-adaptation, DevOps, AIOps, and also quality) to identify publications with relevant metrics. The surveys included here were selected based on publication quality (considering only peer-reviewed conferences and journals) and relevance (assessing the extent of recent AI technology coverage).

For the second step, again the review papers served as a baseline. Here, however, metric definitions were either selected among options or were adapted to meet the needs of controllers as a specific type of AI-generated software model, in contrast to a wider coverage in the first step.

5.2. Metrics—Selection and Catalogue

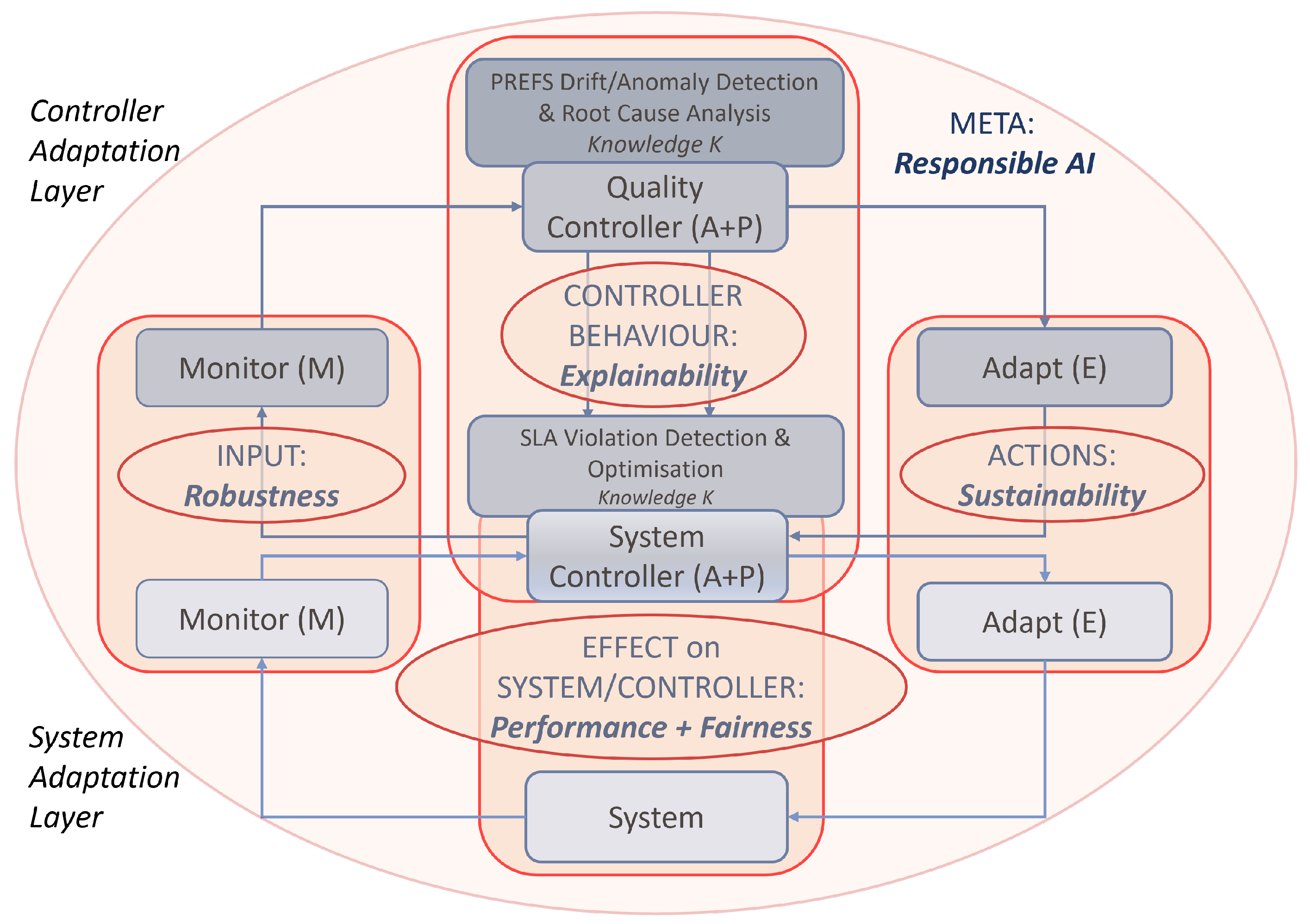

In

Figure 3, the selected quality metrics are indicated. Performance and fairness directly affect the system quality. Robustness is a guard against external uncertainties and influences. Sustainability has an effect on the environment. Explainability allows understandability, e.g., to provide a governance assurance on the actual controller function.

We can classify the metrics based on whether they relate to the control task at hand or affect the resources that this task consumes. For the task, we also indicate whether the control function is directly affected (core), it could be influenced by its direct context (environment), it could skew the results by favouring certain outcomes (bias), it could be related to the responsibility for the task (governance), or it could have an impact on resources (such as energy as one selected concern). The properties are those of a controller, not the application system.

Performance addresses the core quality management function of a controller;

Robustness relates to the input of monitoring the environment and subsequent MAPE phases;

Explainability concerns the governance of the control and quality framework in order to allow for trustworthy behaviour;

Fairness refers to the avoidance of bias in controller decisions and the effect on controller or system performance;

Sustainability relates to the effect of controller actions on the consumption of resources in the environment in terms of cost and energy.

Both positive and negative measurements can be valued, e.g., by rewarding or penalising them, respectively. We measure concerns that directly influence the task at hand, i.e., how well the solution can perform its job. In a second category of quality targets, the environment is addressed. This includes resources and their consumption, e.g., in terms of energy consumption, but also the human or organisation in charge of the system in a governance concern, e.g., in terms of explainability. We also add an impact direction, i.e., whether the concern is internal, influenced by external forces (inwards through disturbances), or influences external aspects (outwards on parts of the environment). This is indicated in

Table 1.

We add another metric at a meta-level that deals with the encompassing concern of responsible AI in order to adjust and tailor the above foundational metrics.

Responsible AI serves as a meta-level aspect that allows us to prioritise and balance the direct quality metrics (performance, robustness, explainability, fairness, sustainability).

All of these metrics will be individually motivated and defined in the next subsections in the following format covering a number of perspectives:

Justification: why the metric is needed;

Assumptions: contextual assumptions;

Rationale: motivation of the definition;

Definition: defined metric;

Example: illustration of metric.

5.3. Performance

Justification: Generally, the performance of a controller refers to the ability to effectively achieve (and optimise) a technical objective. This could be expressed in terms of a function on system performance and cost, e.g., , with as a sample goal. While this works for many monitored application systems, we need here a definition that in more concrete terms takes the objectives and the construction of the controller into account.

Assumptions: We assume that the quality of a controller action in a given state can be quantified through a reward function R. The performance for controllers is the overall achievement of the model towards an optimal reward. We look at reinforcement learning as the prevalent construction technique.

Rationale: The reward is the central guiding performance measure of RL-based controllers, as discussed in the previous section. Reward optimisation is built into approaches like SARSA or Q-learning to optimise the reward [

6,

50]. The performance of a reinforcement learning algorithm can be determined by defining the cumulative reward as a function of the number of learning steps. Better rewards are better performance. Thus, this concept is the basis of the performance definition here.

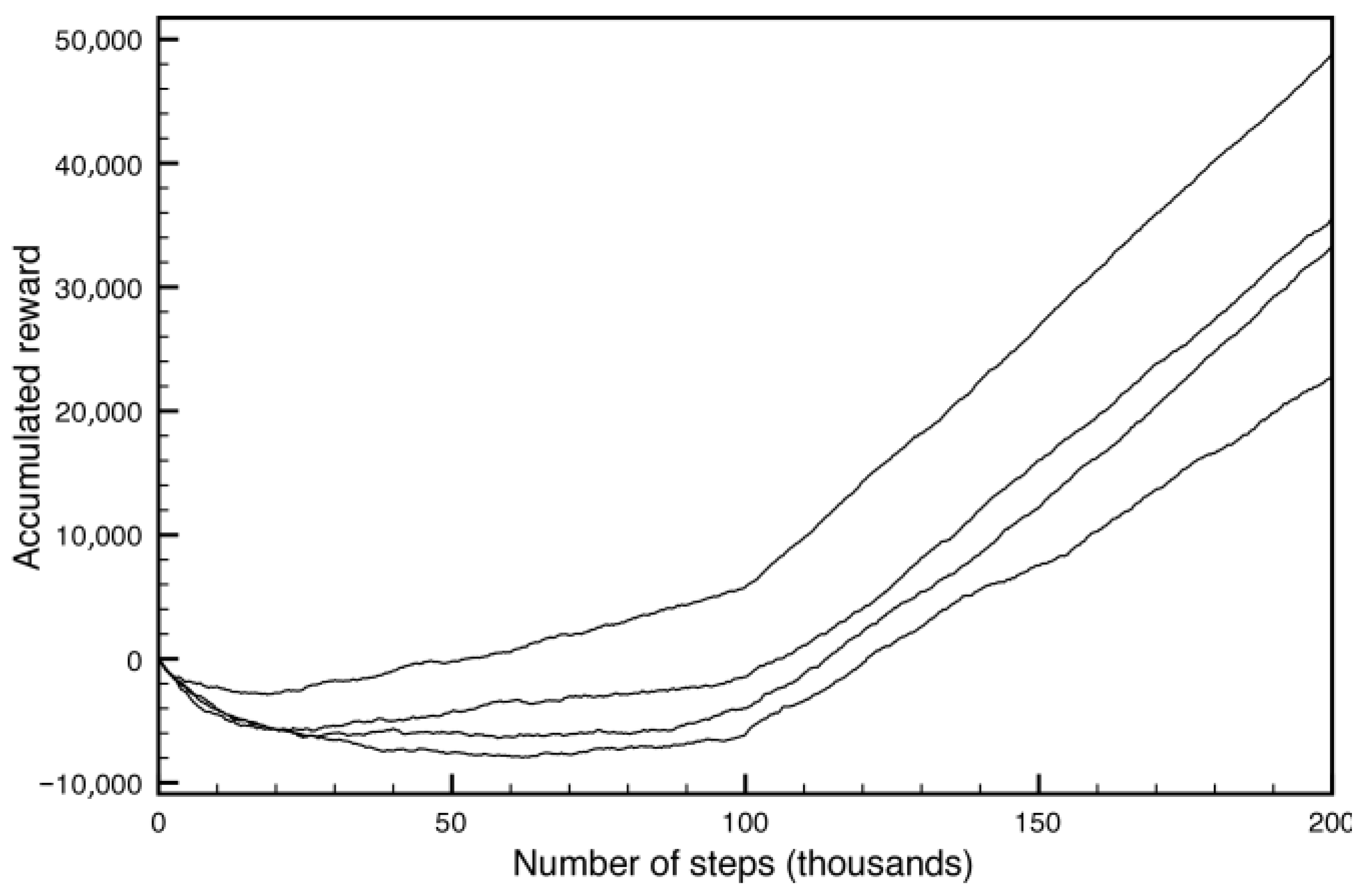

Definition: Different performances emerge depending on the chosen learning rate

for the Q-function (which influences to what extent newly acquired information overrides old information). Three different parameters are important for the performance evaluation in a system where the reward varies over time—see

Figure 4 for an illustration that shows an eventual decrease and increase while the controller is learning. This time-varying performance can be analysed with three parameters:

Convergence: the asymptotic slope of a performance graph indicates the quality of the policy after stabilisation of the RL algorithm at the end;

Initial Loss: the lowest point of the curve (minimum) indicates how much reward is often sacrificed before the performance begins to improve;

Return on Investment: the zero crossing after the initial loss gives an indication of recovery time, i.e., of how long it takes to recover from initial, often unavoidable learning costs.

Note that the second and third cases only apply if there are positive and negative rewards. Also, note that the cumulative reward is a measure of the total reward, but algorithms such as Q-learning or SARSA use discounted rewards, modelled using the discount factor . A flattened graph would indicate that the learning process has finished with a defined policy.

A slightly different perspective emerges for control theory-based controllers. Control theory aims for stability of the systems, i.e., the signal (output action of a controller) should be bounded and minimise fluctuations of the technique system objective, defined in terms of SLA metrics. Notions of convergence, loss and return on investment are applicable to assess the achievement of stability. A reward function could consider these parameters.

Another possibility to define performance is, instead of referring to accumulated rewards, measuring the average reward. This would be a measure of the quality of the learned policy.

Example: The metric is connected to the performance of the learning process. A positive impact on the convergence and loss criteria can be generated by using expert models in the training. For instance, a fuzzy logic rule system has been successfully used for this purpose [

52].

5.4. Robustness

Justification: Robustness is the ability to accept, i.e., deal with a wide range of monitored input cases. This includes for instance uncertainties, noise, non-deterministic behaviour, and other disturbances. These are typical for cyber-physical and distributed systems where sensors, connections, or computation can fail in different locations. Robustness concerns arise in non-deterministic behaviour situations and needs repeated experiments in the evaluation. When controllers are constructed with disturbances present, robustness against these is required.

Assumptions: We use the term disturbances to capture the multitude of external factors [

17]. Disturbances can be classified into three possible contexts: observations, actions, and dynamics of the environment that the controller interacts with, thus giving the following disturbance classes:

Observation disturbances happen when the observers (e.g., sensors) used cannot detect the exact state of the system;

Action disturbances happen when the actuation of the system ultimately is not the same as the one specified by the control output, thus causing a difference between actual and expected action;

External dynamics disturbances are disturbances that are applied directly to the system. These are environmental factors or external forces.

Rationale: Disturbances can be classified into different behavioural patterns for the observed system quality over time—see

Figure 5. The patterns are important, as the evaluation of a controller’s robustness is often carried out using simulations based on disturbances being injected into the system following these patterns.

Figure 5 shows the five patterns in two broader categories—three non-periodic and two periodic ones—following the classification in [

17].

Definition: The patterns are important to identify disturbance types in a robustness metric. Thus, we define them first.

Non-periodic disturbance patterns are the following:

White Noise Disturbances: These indicate the natural stochastic noise that an agent encounters in real world situations. Noise can be applied, ranging from zero with increasing values of standard deviation.

Step Disturbances: These model a system change with one sudden and sustained change. The magnitude of the step can vary.

Impulse Disturbances: These show system behaviour with a sudden, but only very short temporary change. The impulse magnitude can vary, as above.

Periodic disturbance patterns are the following:

Saw Wave Disturbances: these are cyclic waves that increase linearly to a given magnitude and instantaneously drop back to a starting point in a repeated way. Thus, this pattern combines characteristics of the step and impulse disturbances but is here in contrast applied periodically.

Triangle Wave Disturbances: These are also cyclic waves that, as above, repeatedly increase linearly to a given magnitude and decrease at the same rate to a starting point (and not suddenly as above). This is very similar to the saw wave, but exhibits a more sine-wave-like behaviour.

We can quantify robustness by relating the performance metrics (as above in the ‘Performance’ section) as a ratio between an ideal and a disturbed setting:

This can be calculated for all disturbance patterns. The closer the ratio is to 1, the more robust the controller is.

Example: White noise is often caused in distributed environments such as edge clouds due to outages and anomalies in the system operation and monitoring. Here, the training needs to consider these disturbances. Another example is extended, hardly noticeable slopes that might be caused by drift in the application.

5.5. Explainability

Justification: Explainability is important, in general, for AI, in order to improve the trustworthiness of the solutions. For technical settings such as controllers, explainability is beneficial since it could aid a root cause analysis for quality deficiencies. The explainability of the controller actions is a critical factor in mapping observed model deficiencies back to system-level properties via the monitored input data to the model creation.

Explainability is a meta-quality aiding to improve the controller quality assessment. Since how and why ML algorithms create their models is generally not always obvious, a notion of explainability can help to understand deficiencies in the other four criteria and remedy them.

Assumptions: Explainability differs depending on the construction mechanism, being typically more challenging for ML-constructed controllers than for fuzzy or probability-based ones where the construction is manual on an explicitly defined function or theory. For example, if fuzzy logic is applied, the deciding function is the membership function. Explainability for RL is less mature than for other ML approaches.

Rationale: While explainability is a very broad concern, we introduce here definitions and taxonomies that are relevant for a technical controller setting and allow us to define basic metrics based on observations that can be obtained in the controller construction and deployment. The metrics defined can be used to automatically create indicators or recommendations. Here, however, a full automation of a reconfiguration or other correction would be difficult.

Definition: A number of taxonomies for ML explanations have been proposed in recent years. We focus here on [

20] to propose a classification of explainability into three types. Note that we extend these three classes by concrete measurements for our setting.

Feature importance (FI) explanations: These identify features (or metrics in our case) that have an effect on an action a proposed by a controller for an input state s. FI explanations provide an action-level perspective of the controller. For each action, the immediate situation causing an action selection is considered.

Assume system metrics . Then has an effect if for all , meaning that the quality difference between two subsequent states from state s with action a is the greatest for metric (or feature) .

Learning process and MDP (LPM) explanations: These show past experiences or the components of the Markov decision process (MDP) that have led to the current controller behaviour. LPM explanations provide information about the effects of the training or the MDP, e.g., how the controller handles the rewards.

The effect can be measured in terms of the quality function for two controllers (or underlying MDP) instances and with fixed data for training and testing, i.e., is better than , if for selected system states s and actions a.

Policy-level (PL) explanations: These show the long-term behaviour of the controller as caused by its policy. They are used to evaluate the overall competency of the controller to achieve its objectives.

The PL explainability definition follows LPM measurement ‘is better than’, but here consider variations in data sets, even in terms of features or metrics used.

Other explainability taxonomies also exist. For instance, [

19] distinguishes two types in terms of their temporal scope:

Reactive explanations focus on the immediate moment, i.e., only consider a short time horizon and momentary information, such as direct state changes of the controller, as in FI;

Proactive explanations focus on longer-term consequences, thus considering information about an anticipated future and changes, such as those that LPM and PL represent.

A reactive explanation provides an answer to the question “what happened?”. A proactive explanation answers the question “why has something happened?”. These can then be further classified in terms of how an explanation was created. Beyond the simple measurements that can serve as indicators of the explanation, more complex explanatory models could be constructed. Reactive explanations could be policy simplifications, reward decompositions, or feature contributions and visual methods. Proactive explanations could be structural causal models, explanations in terms of consequences, hierarchical policies, and relational reinforcement learning solutions. More research is needed here.

Example: In a concrete situation, it might need to be determined of some lower layer metric (such as cost over performance) or some strategy (for instance for storage management) is favoured. A remediation could use explicit weightings to level out disbalances.

5.6. Fairness

Justification: Specifically where humans are involved, the fairness of decisions becomes crucial, and any bias towards or against specific groups needs to be identified. This concern can also be transferred from the human viewpoint to the technical domain, creating a notion of technical fairness that avoids preferences that could be given to specific technical settings without a reason. An example of an unfair controller would be a bias toward a specific management strategy. For instance, historically an overprovisioning strategy could have been followed, without that having been objectively justified.

Assumptions: We assume that, as for humans, past technical behaviour and decisions can be detrimental.

Rationale: The definition we propose there was originally referring to states and the quality of actions in these for RL, but can be adapted to all controllers that follow our definition, as there is always a state in which an action is executed, which in turn can be evaluated. This ensures that the long-term reward of a chosen action a is greater than that of , and there is no bias that would lead to a selection not guided by optimal performance. Fair controllers must implement the distribution of actions, with a somewhat heavier weight put on better-performing actions judged in terms of (possibly discounted) long-term reward. Actions cannot be suggested without having a positive effect on the objective performance of the system as defined above.

Definition: Fairness can be defined in a precise way. We follow the definition given by [

18] if a quality function

Q or reward function

R is defined:

A policy is fair if in a given state s a controller does not choose a possible action a with probability higher than another action unless its quality is better, i.e., .

The above definition is often referred to as exact fairness, i.e., quality measured as the potential long-term discounted reward. Possible alternatives shall also be introduced. Approximate-choice fairness requires a controller to never choose a worse action with a probability substantially higher than that of a better action. Approximate-action fairness requires a controller to never favour an action of substantially lower quality than that of a better action.

A number of fairness remedies that are known in the ML domain include the improvement of data labelling through so-called protected attributes. An example is the automation of critical situation assessment, where technical bias could treat specific failures or failure management strategies differently. Here, for instance, a high risk of failure based on past experience might be considered, which could have a probability of discrimination based on certain events that have occurred and could be biassed against or towards these, be that through pre-processing (before ML training) or in-processing (while training). The challenges are to find bias and remove this bias through a control loop, e.g., using favourable data labels as protected attributes to manage fairness. Examples in the edge controller setting are if smaller or bigger device clusters could be favoured wrongly or if specific types of recommended topologies or recommended configuration sizes (messages, storage, etc.) exist.

Example: Often, underprovisioning in the form of a static resource allocation happens in manual systems due to unawareness of scalability options or the aim for simplicity. In case of high demand, this would slow down the system and possibly disadvantage users. Here, favourable labels reflecting user impact could be identified.

5.7. Sustainability

Justification: General economic and ecological sustainability goals are important societal concerns that also should find their application in computing, here specifically in terms of cost- and energy-efficiency of the model creation and model-based decision processes within a controller.

Assumptions: Sustainability is often used synonymously with environmentally sustainable, e.g., in terms of lower carbon emissions [

23]. Thus, we focus on environmental sustainability here.

Rationale: While different measures can be proposed in this environmental sustainability context, we choose energy consumption here as the core of our sustainability definition because it can often be determined in computing environments.

Definition: Energy-efficiency can be defined through widely accepted and measurable metrics. We present two such metrics with examples of common tools to measure them:

These metrics are often put into comparison with performance metrics to assess performance in terms of costs. Similarly to the robustness case, a ratio allows us to indicate a possible trade-off between performance and sustainability to define sustainability. We can relate the performance to the cost or resource consumption it causes:

This can be applied to various resource or cost types. Sustainability focusing on the consumption of resources is often considered and measured through penalties in the value or quality calculation.

Example: Overprovisioning is an effective resource allocation strategy from a system performance perspective but generally causes the highest energy consumption overhead. Explicit penalisation of sustainability defects needs to be introduced.

5.8. Responsible AI (Meta-Level)

Responsible AI serves as a meta-level concern to prioritise and balance the five core quality metrics of performance, robustness, explainability, fairness, and sustainability that were defined above.

Justification: Responsible AI acts as a guiding principle, ensuring that the implementation and configuration of AI-based controllers align with societal, ethical, and operational goals.

Assumptions: Responsible AI metrics are derived as aggregate quality measures influencing controller priorities. Instead of direct measurements, these metrics act as evaluative tools guiding trade-offs among competing quality objectives. They reflect the risks and impacts of quality failures at a systemic level.

Rationale: By framing Responsible AI as a meta-level concern, it integrates seamlessly with the PREFS-R framework. Metrics like “Risk of Quality Failure” and “Impact Assessment” serve as overarching tools to evaluate the likelihood, severity, and consequences of deviations from expected behaviours across foundational metrics (e.g., performance, robustness).

Definition: Our analysis prioritises ethical considerations in Responsible AI, focusing on its role as a meta-level framework that evaluates and balances the foundational core quality metrics (fairness, explainability, sustainability, robustness, and performance). Responsible AI addresses trade-offs and contextual priorities by introducing two overarching meta-metrics:

Risk of Quality Failure (Meta-Risk Analysis): Measures the likelihood and severity of performance or robustness falling below critical thresholds of each identified risk

i.

- -

Likelihood: Based on statistical evaluation of operational data, considering external disturbances, internal errors, or drift;

- -

Severity: Defined by the impact on system reliability, safety, or user trust.

Ethical Damage/Cost Score (Impact Evaluation): Quantifies potential damage across societal, environmental, and technical dimensions using weighted criteria.

- -

Damage refers to measurable consequences, such as resource wastage, and privacy breaches;

- -

Weights prioritise different concerns based on the context of the application (e.g., sustainability vs. robustness).

Example: In traffic systems, performance and robustness often dominate, but in medical contexts with humans directly involved as the controlled subjects, fairness and explainability play a more significant role. Sustainability might be more dominating in resource-constrained environments.