4.1. End Effector Deformation Visualization

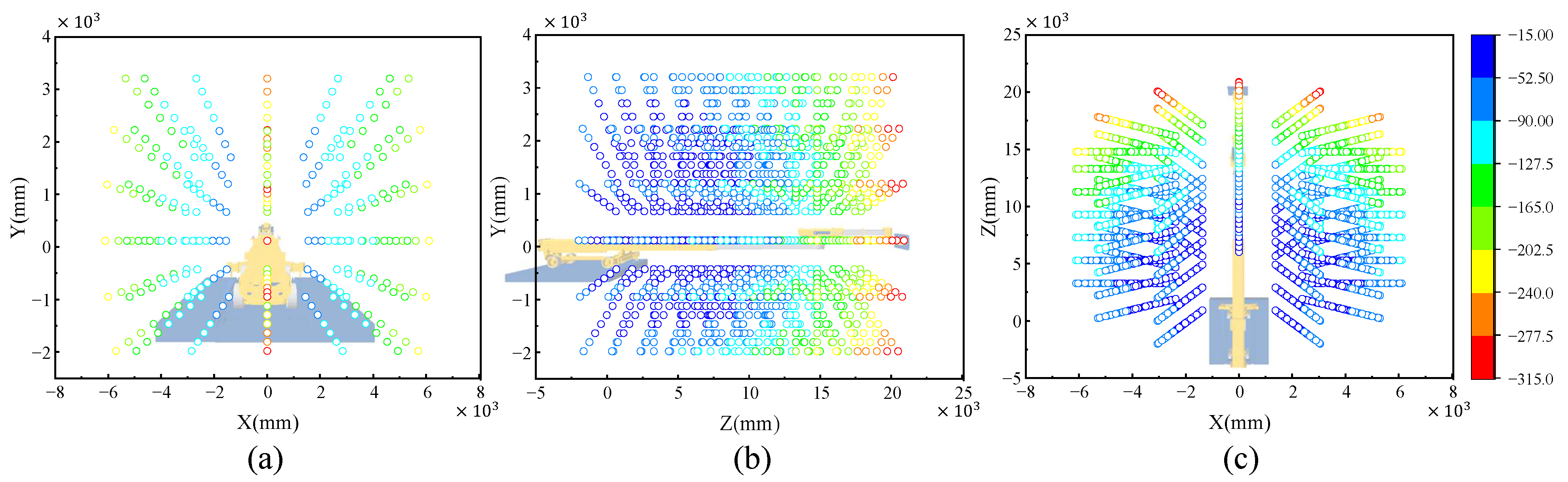

In a working space, end effector deformation visualization can help us to investigate the actual end effector position of different joint configurations. As shown in

Figure 12, all the solved FE simulation solutions from the offline deformation dataset are plotted in the working space. To analyze the end deformation distribution, three projection maps are provided on the X–Y, Y–Z, and X–Z planes. Every end effector position is calculated by the forward kinematic model and expressed in the base coordinate system

. A total of 3528 circles are displayed, and their colors represent the corresponding deformation magnitudes. It can be observed that the redder the color, the greater the deformation, while the bluer the color, the smaller the deformation. As illustrated in

Figure 12c, deformation gradually increases along the positive direction of the

Z-axis. In the 0 to 10,000 mm range, the main deformations fall between −15 mm and −90 mm, represented by blue circles, indicating that the deformations are relatively small. However, when the end effector moves into the range of 12,000 mm to 20,000 mm, the deformation increases significantly, ranging from −90 mm to −277.5 mm. The number of red circles accounts for a small proportion compared with the others and is primarily distributed at the distal end of the working space. The reason is that the upper arm and forearm are both significantly extended, resulting in the end effector being located at a far distance from the fixed base support. As a result, the moment increases, leading to greater bending deformation. Therefore, for the liners installed at the far conical surface, more compensation and adjustment should be given.

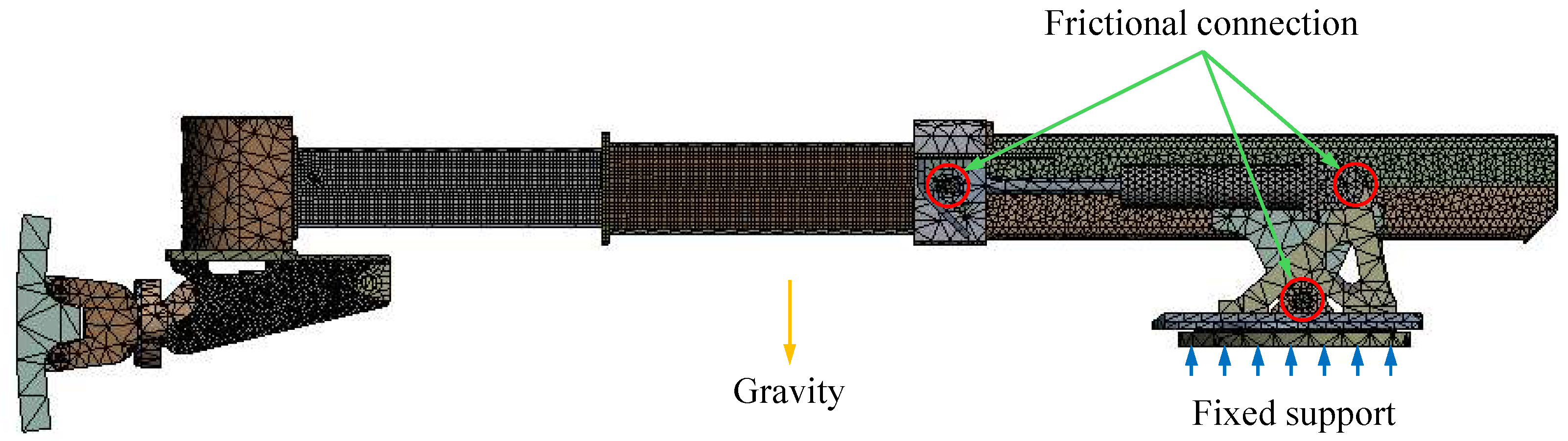

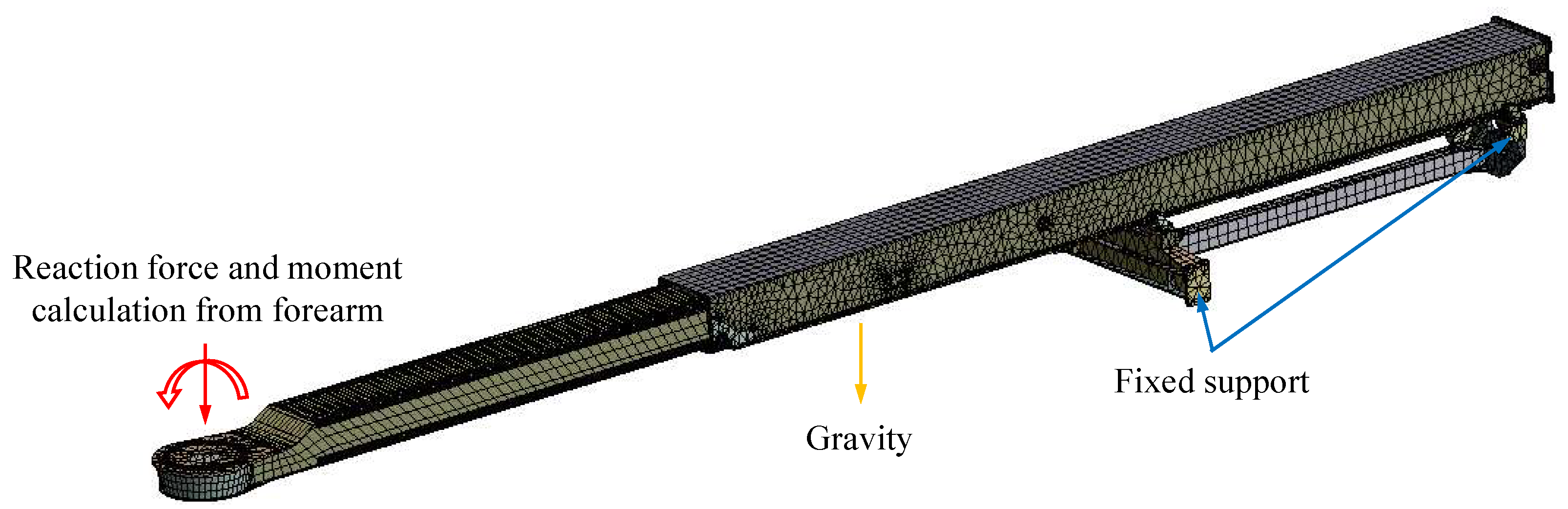

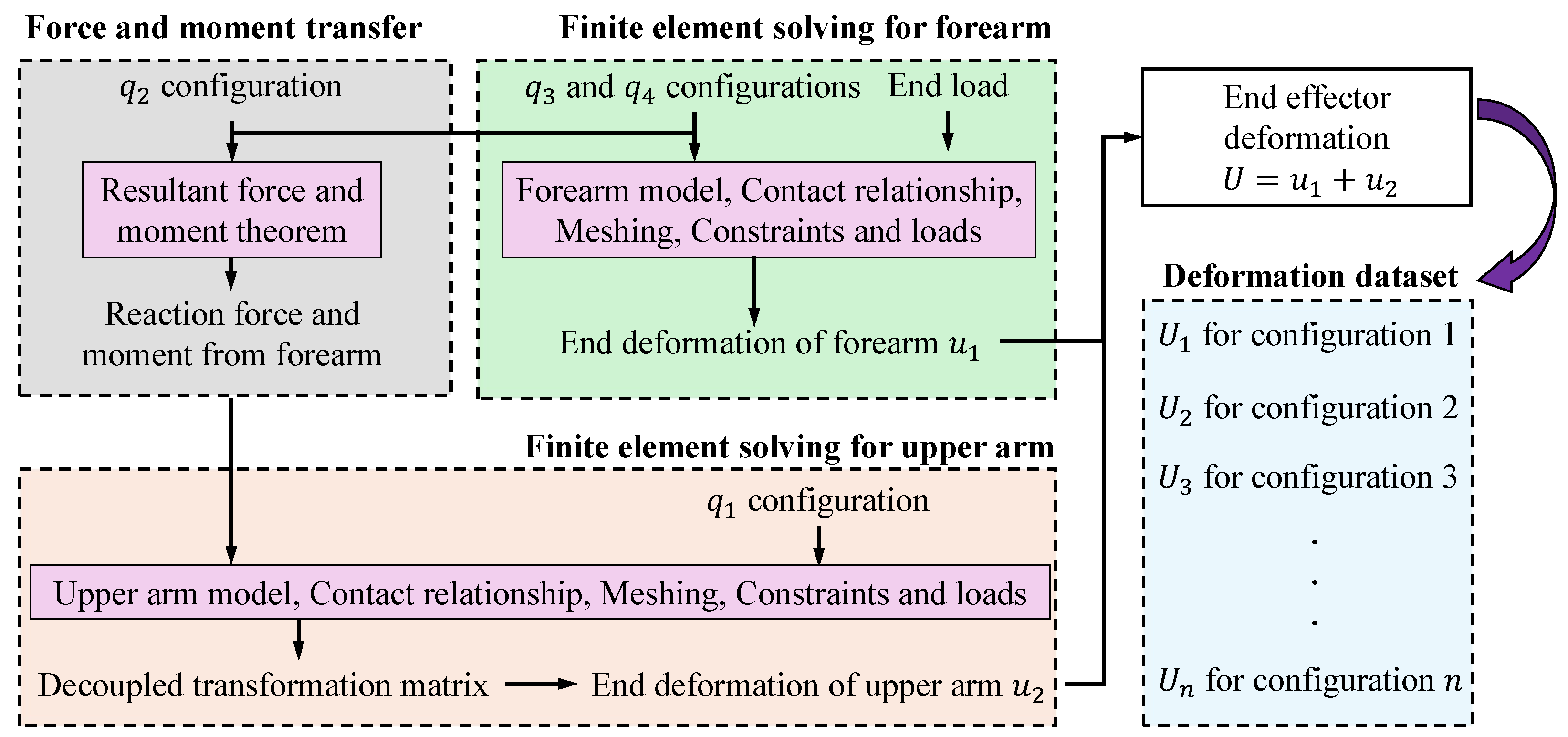

4.2. Manipulator Decomposition Necessity

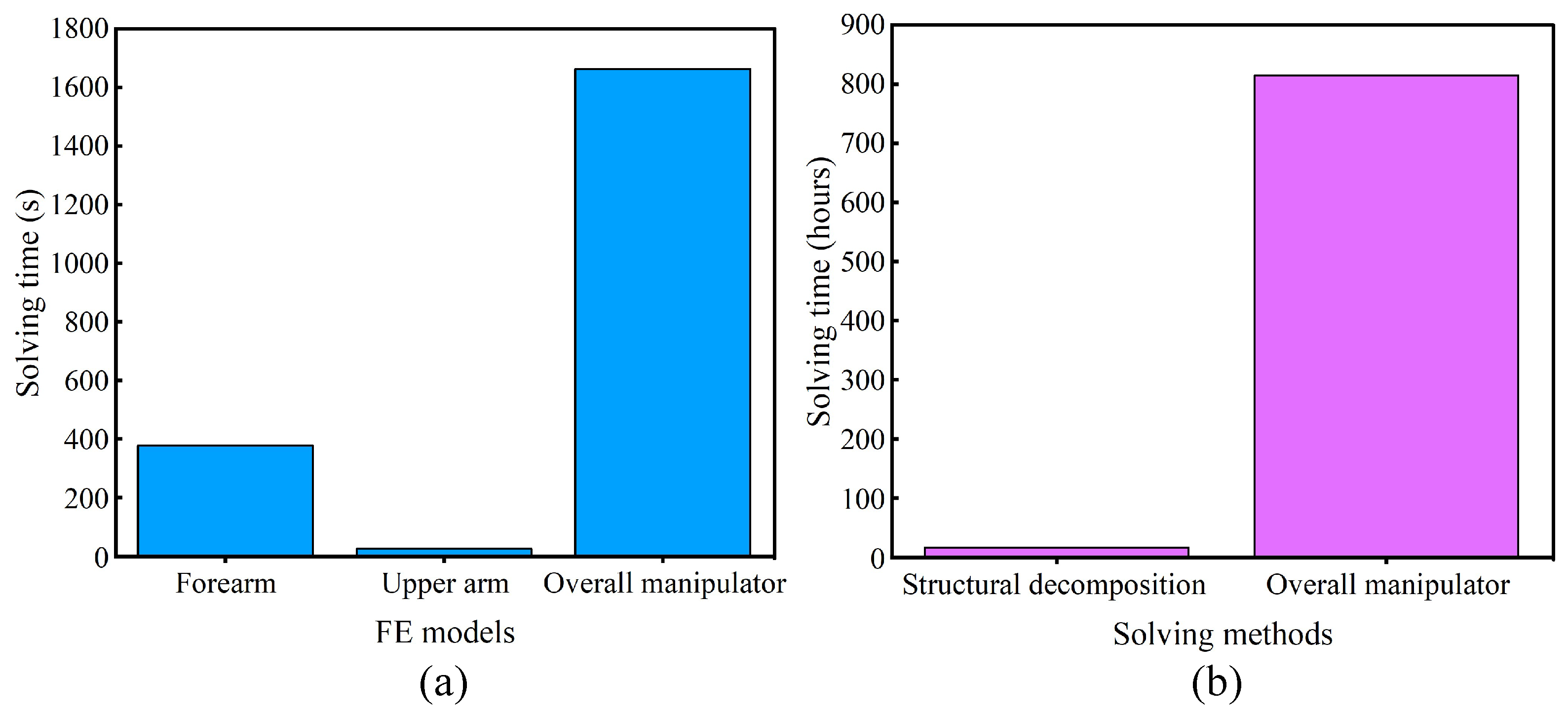

In this section, the necessity of the proposed separate FE modeling and decoupling operation is discussed. One of the key advantages of manipulator decomposition is the significant improvement in computational efficiency. The average FE solving times are presented in

Table 6. For the separate FE models, the forearm and upper arm individual solving needs

s and

s to obtain the end deformation results. However, the solving time of the overall manipulator FE model reaches

s, which is approximately 4.1 times longer than the total time of the individual components, as presented in

Figure 13a. In addition, the total solving time of different methods should be calculated to further demonstrate the advantages of separate solving. As shown in

Table 4, joints

and

each have six different configurations, while joints

and

each have seven configurations. A total of 1764 FE models are established and should be solved. Therefore, the establishment of the end deformation dataset needs about 814.87 h (33.95 days), which is inefficient and unacceptable. In comparison, the proposed separate modeling method completes all FE sample solving only needs 17.14 h, according to the formula

. As presented in

Figure 13b, manipulator decomposition has a huge advantage. On the other hand, the individual solving for the upper arm can be conducted through scripting automation in ANSYS 2022 R1 since the reaction force and moment are calculated as discussed in

Section 3.3. Conversely, overall FE modeling requires manual configuration adjustments, which makes it infeasible and inefficient for establishing the end deformation dataset. The advantages and weaknesses of each solving method are summarized in

Table 7, which explains the reason why structural decomposition and separate solving are necessary.

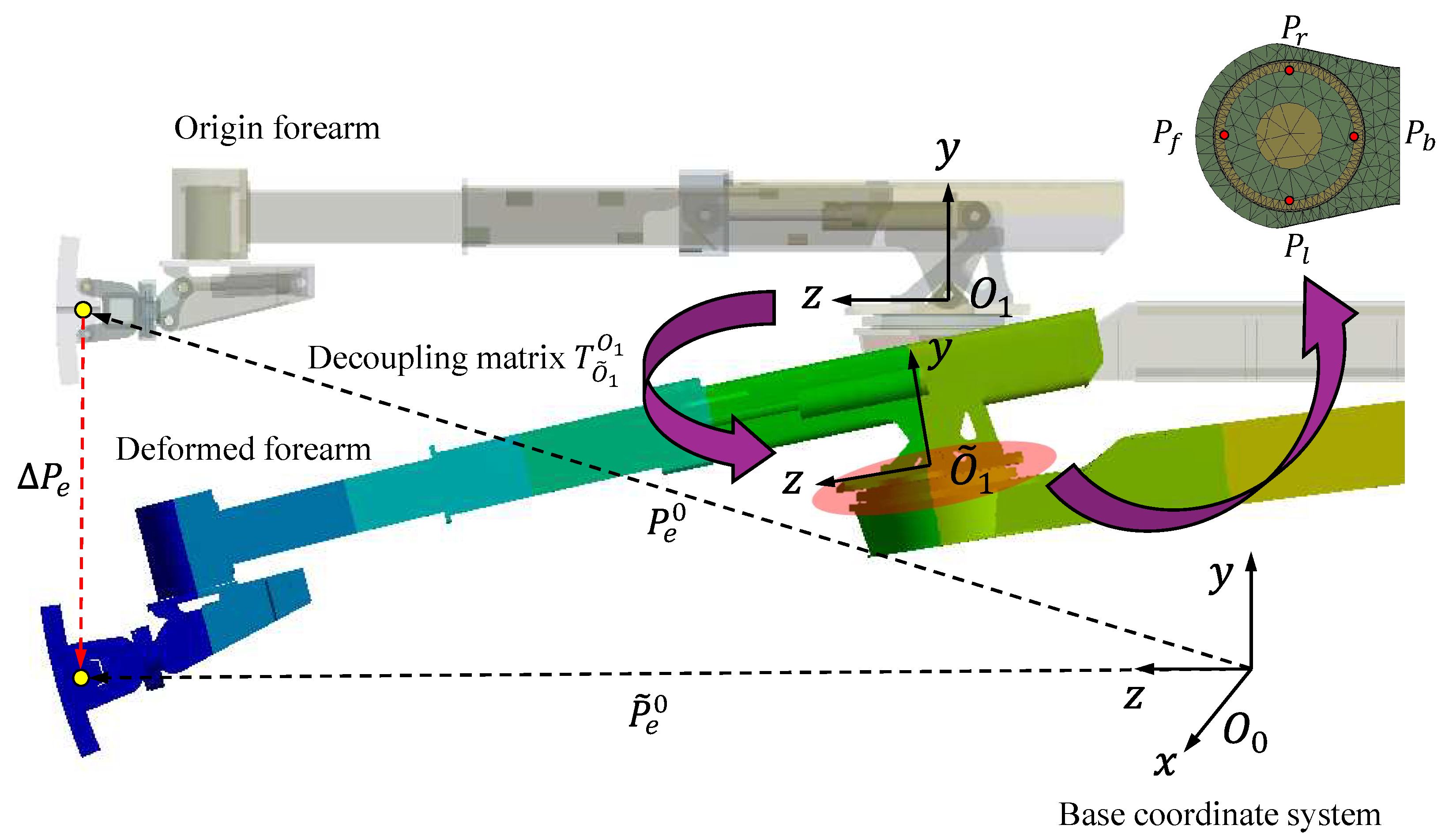

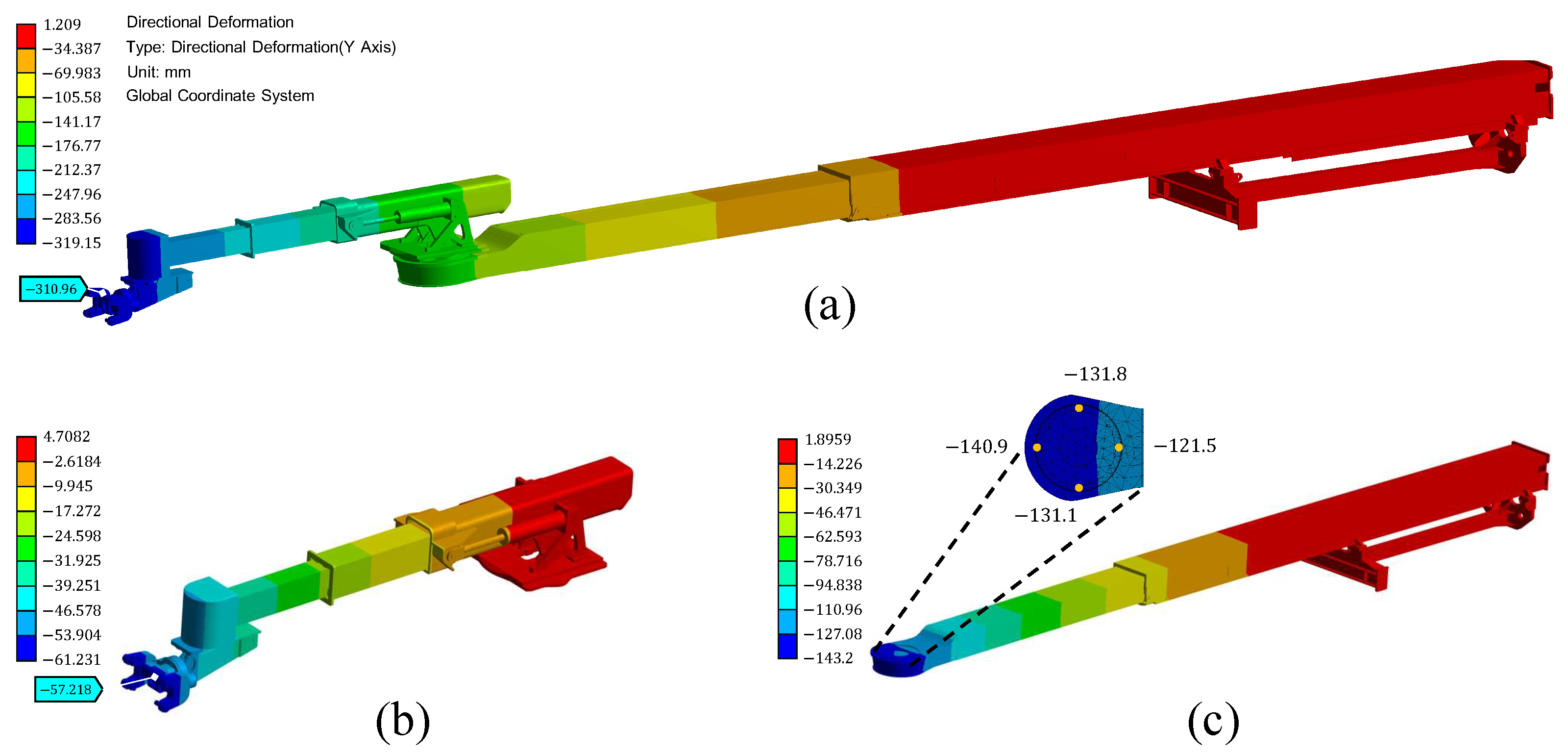

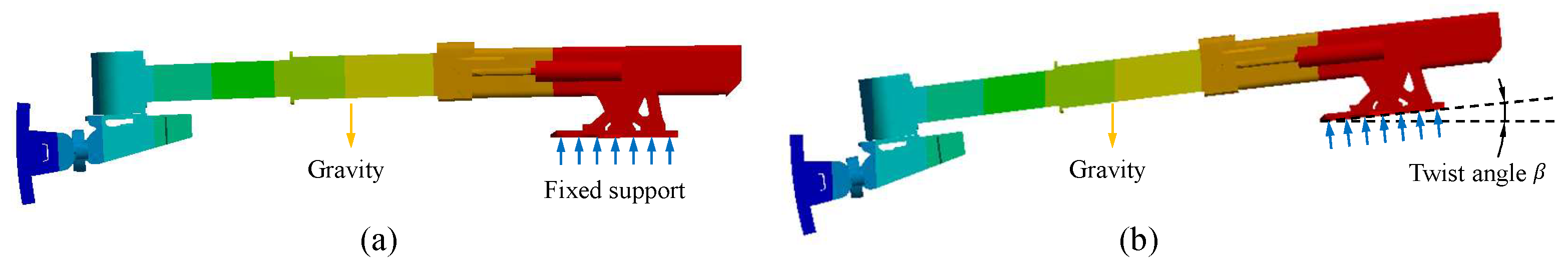

4.4. Simulation Error Analysis

From the above comparison experiments, it can be found that the results of the overall and separate FE simulations have small errors in end deformation. The reason is that individual separate FE solving has two main problems: coupling relationship ignorance and boundary condition distortion. Fortunately, the coupling relationship is considered and discussed in

Section 3.5, and the proposed decoupling matrix can solve the effect of upper arm deformation on end effector positioning accuracy. However, for the separate forearm FE model, the actual fixed support condition at the turntable cannot be known in advance. For the same joint configuration, the boundary conditions of separate and overall FE simulations are shown in

Figure 16a and b, respectively. In the overall FE simulation, there is a twist angle

at the plane of the turntable, which is different from the theoretical fixed support in the separate FE simulation. Furthermore, this twist angle can only be obtained from the overall FE solution. Although this error cannot be considered in our proposed method, the effects are limited and acceptable, as elaborated in the following discussion.

A quantitative analysis is conducted to investigate the effect of forearm boundary distortion. As presented in

Table 10, the FE models with seven different configurations of the joint

are solved to find out the error changes across the entire workspace. Based on the range of twist angles generated by the overall FE simulation, 11 different fixed support conditions (twist angle

) are designed to assess the negative influence of boundary condition distortion. It can be observed that end effector deformation decreases as the twist angle increases, which can be explained by the reduction in the reaction moment. In the fully extended configuration, the difference between the minimum and maximum values is only 2.9 mm. Although the boundary distortion errors arising from the structural decomposition are inevitable, the influence is limited and insignificant for the mill relining manipulator.

4.5. Effectiveness Validation of Online End Deformation Calculation

For the above-mentioned two special joint configurations, the end deformation can be directly found from the established offline discrete deformation dataset. However, the end effector deformation of random joint configurations requires the proposed online calculation algorithm. Therefore, this section focuses on validating the significance of the decoupling operation and the effectiveness of the proposed KAN online prediction algorithm. As presented in

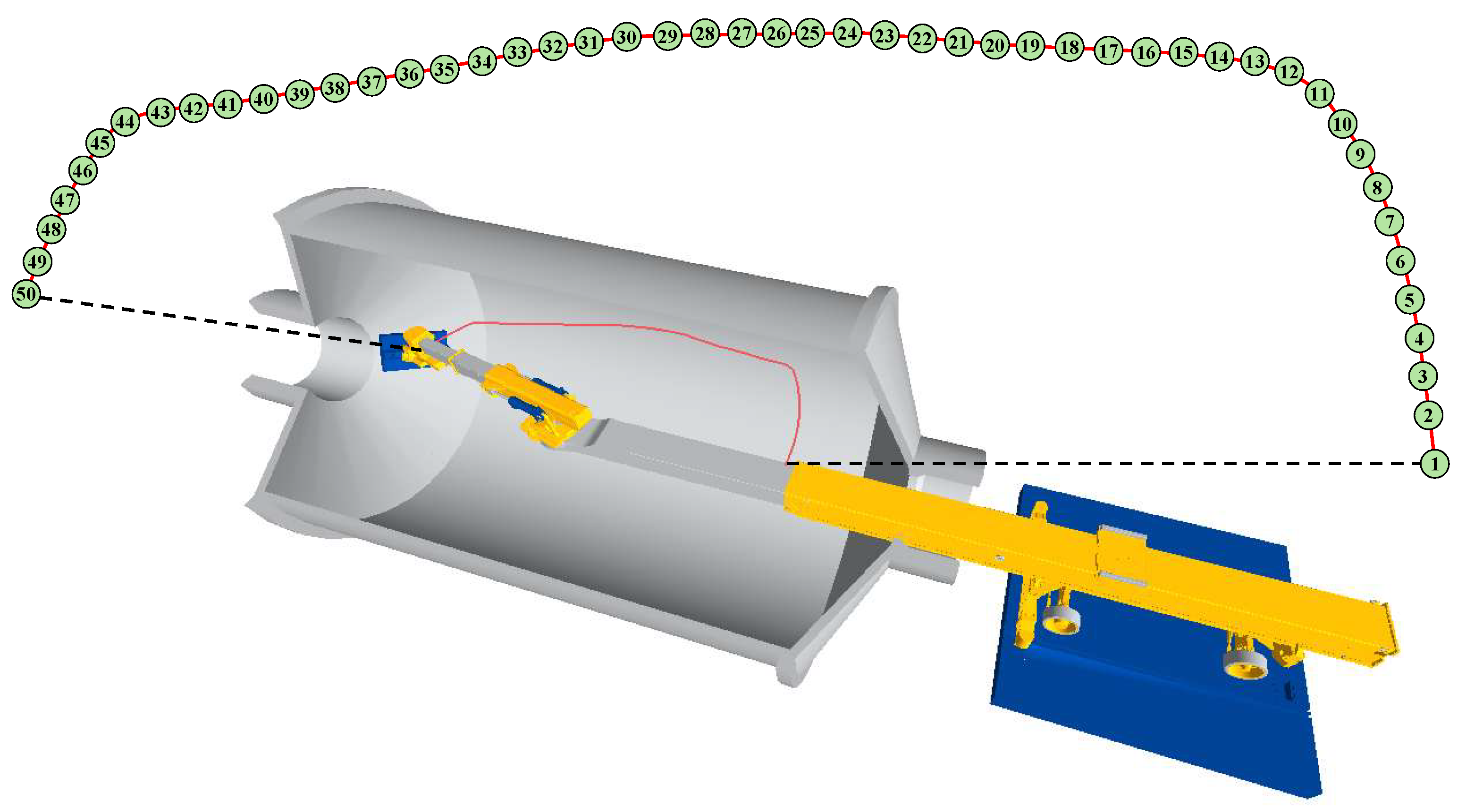

Figure 17, the mill liner has to be moved from the transfer cart to the target far conical surface. The red trajectory illustrates the motion path of the manipulator’s end effector. For this liner exchange task, all joint configurations are random and not included in the offline dataset, indicating that this simulation experiment is closer to the practical engineering application. It should be noted that this task assumes the manipulator is operated at a low speed. Therefore, gravity is the dominant factor on end deformation during this dynamic process rather than the inertial, Coriolis, and centrifugal forces. On this basis, the end deformation for each joint configuration can be calculated using FE static models.

Each path node is associated with a corresponding joint configuration. Therefore, from the entire motion path, 50 path nodes are selected and used as the test samples to predict end effector deformation. It can be seen that the selected path nodes are uniformly distributed along the end trajectory. Furthermore, four other solving algorithms are introduced as the comparison groups to demonstrate the superiority of the proposed method. As shown in

Table 11, IJDW denotes the interpolation algorithm based on joint distance weight, while the coupling relationship is not considered. Different from IJDW, IJDW-D takes the decoupling operation into account so that the significance of the proposed decoupling method can be verified through these comparison experiments. The Radial Basis Function (RBF) [

36] and MLP are involved to demonstrate the advantage of the proposed KAN method in the field of neural networks. KAN-4 and KAN-7 are the proposed online end deformation prediction algorithms based on the KAN neural network. For KAN-4, the designed inputs are

,

,

, and

, which are consistent with the dimensions of the established offline dataset. However, KAN-7 denotes that the architecture of KAN has seven input neurons, that is,

to

. It should be noted that the values of

to

are 0 during training, whereas the actual configurations are used during end deformation prediction. All joint values are normalized before being input into the network. All prediction algorithms have one output representing end deformation. Except for the RBF, the other networks have 10 hidden neurons for model fitting. Due to the designed network having few parameters, Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) [

37] is employed as the optimization strategy instead of Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) [

38] or Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) [

39]. LM is a Jacobian-based training algorithm and has a high convergence speed. The model is considered to have converged when the gradient norm falls below 1 × 10

or the maximum iteration number of 200 is reached. Different from learnable activation functions in the KAN, the activation functions of the MLP network in the hidden and output layers are set as tansig and purelin, respectively. Unlike MLP, the KAN has another parameter of the order of the B-spline curve, which is set as 3 in this study. To avoid overfitting and underfitting, the spread of RBF is set as 10 based on the grid search method. Although the density of the established end deformation dataset is sparse and uniformly distributed, L1-norm and L2-norm regularization methods are also involved during KAN training, each with a coefficient of 1 × 10

.

In the following experiments, five metrics are used in this paper to evaluate the performance of different methods: coefficient of multiple determination (

), mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean square error (MSE). Their calculation formulas are expressed in Equations (

13)–(

17), where

is the reference value generated by the overall manipulator FE solving,

denotes the predicted result by different algorithms, and

represents the mean value of all

.

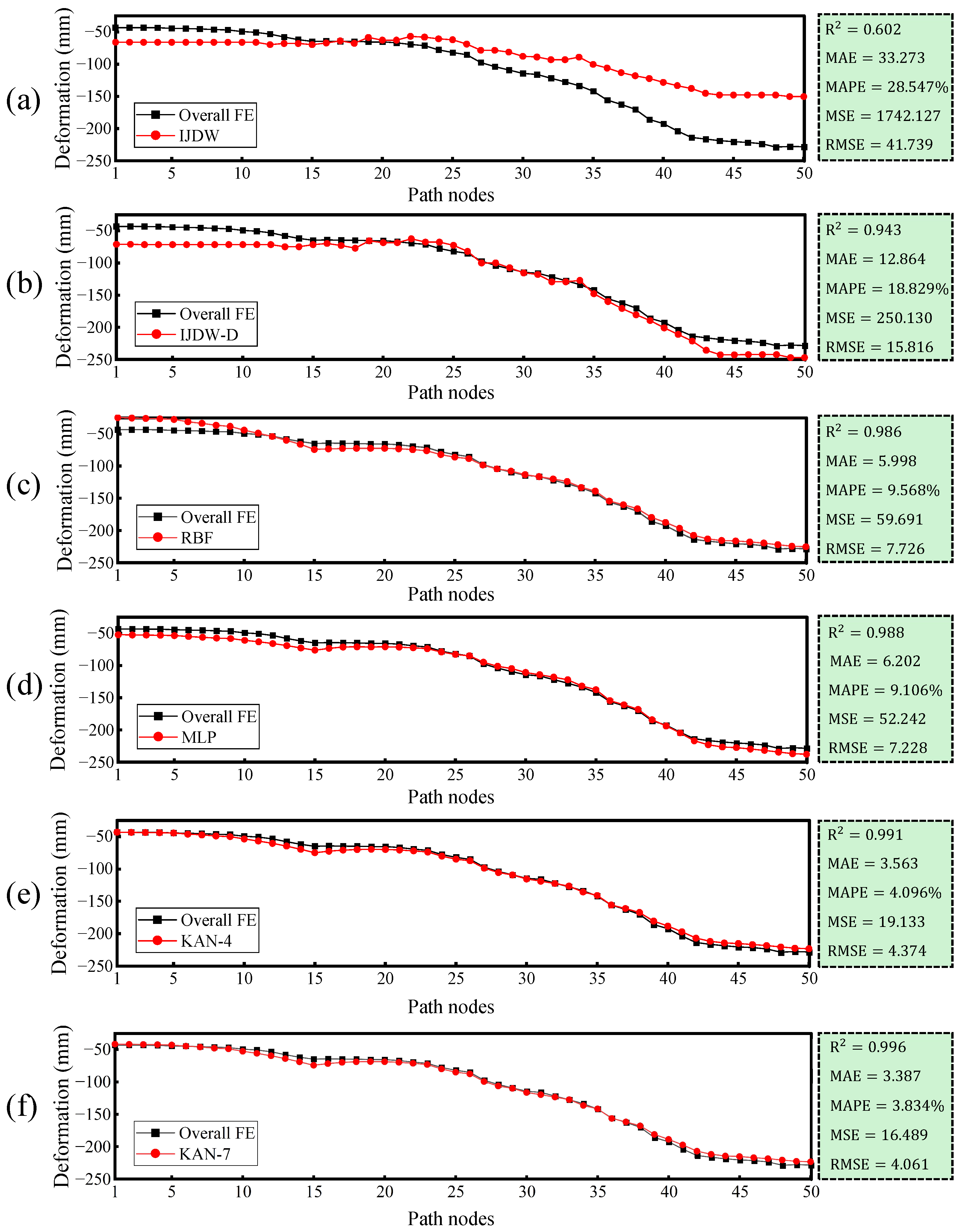

As presented in

Table 12, all joint configurations of the 50 path nodes are used as test samples. In the simulation experiment, the overall manipulator FE model is solved, and its results are used as the reference. Based on the established offline end deformation dataset, the different algorithms are used to solve each FE model of each path node. As presented in

Table 13, the predicted end effector deformation by IJDW is distorted due to the lack of consideration of the coupling relationship. Especially for the remote path nodes, the maximum end deformation error reaches 77.9 mm. As presented in

Figure 18a, an X-shaped comparison result is observed between the reference and predicted values. The explanation is that, as the extension length increases, the coupling effect between the forearm and the upper arm becomes more pronounced. Compared with IJDW, the end deformation errors of IJDW-D are reduced due to the incorporation of the decoupling operation. As illustrated in

Figure 18b, all metrics have a great improvement. For instance,

has been increased to 0.943 from 0.602. Although the effectiveness and necessity of the proposed decoupling method are demonstrated through this comparison experiment, the end deformation prediction accuracy remains insufficient. Therefore, the neural network is introduced to further improve the performance of end deformation prediction. It can be found that RBF and MLP neural networks with a decoupling operation further reduce the prediction errors, particularly at both boundary nodes. As shown in

Figure 18c,d, the trends of the red and black curves tend to coincide, and the corresponding

values indicate that the models exhibit high fitting performances. The best performance is achieved by the proposed KAN-based network since it is more suitable for this lightweight fitting problem. As shown in

Figure 18f, KAN-7 exhibits a slight improvement over KAN-4. The reason is that the additional three inputs enrich the learnable features during model training. For the results achieved from KAN-7, the values of

, MAE, MAPE, MSE, and RMSE are 0.996, 3.387, 3.834%, 16.489, and 4.061, respectively. Compared with the MLP algorithm, the MAE, MAPE, MSE, and RMSE decrease by 2.815, 5.719%, 35.753, and 3.167, respectively, while the

value increases by 0.008. The capability of end effector deformation prediction is further improved. The superiority of the KAN model is further evidenced by the red curve in

Figure 18f, which almost coincides with the black reference line. Compared with other algorithms, the KAN has smaller parameters, and its learnable activation functions have a better capability for fitting nonlinear mapping. In addition, the spline-based activation functions of the KAN can focus not only on global features but also on local features. For instance, changes in end deformation arise from modifications to an individual joint. All the above discussion explains why KAN can achieve excellent performance across all metrics. Although the end trajectory comparison between the overall FE simulation and the predicted deformation is not visually significant at the scale of the whole grinding mill, we also provide simulation videos in the

Supplementary Materials.

In addition, it should be clarified that the average prediction time for one sample is 0.016 s. This fast calculation method can be deployed on devices with limited computational capability, such as control systems based on programmable logic controllers (PLCs) or embedded platforms. In contrast, the overall FE static method is more suitable for the laboratory environment equipped with high-performance computers rather than real industrial scenarios. The reason is that its long model-solving time makes it unable to provide real-time feedback to a manipulator’s control system. In addition, if different payloads are incorporated as variables to expand the training dataset, the model will exhibit higher generalizability in predicting end deformation under varying liner weights. In summary, the proposed online end deformation calculation method can satisfy real-time manipulator motion control and can be integrated into a digital twin system.