Gain-Enhanced Correlation Fusion for PMSM Inter-Turn Faults Severity Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup and Dataset

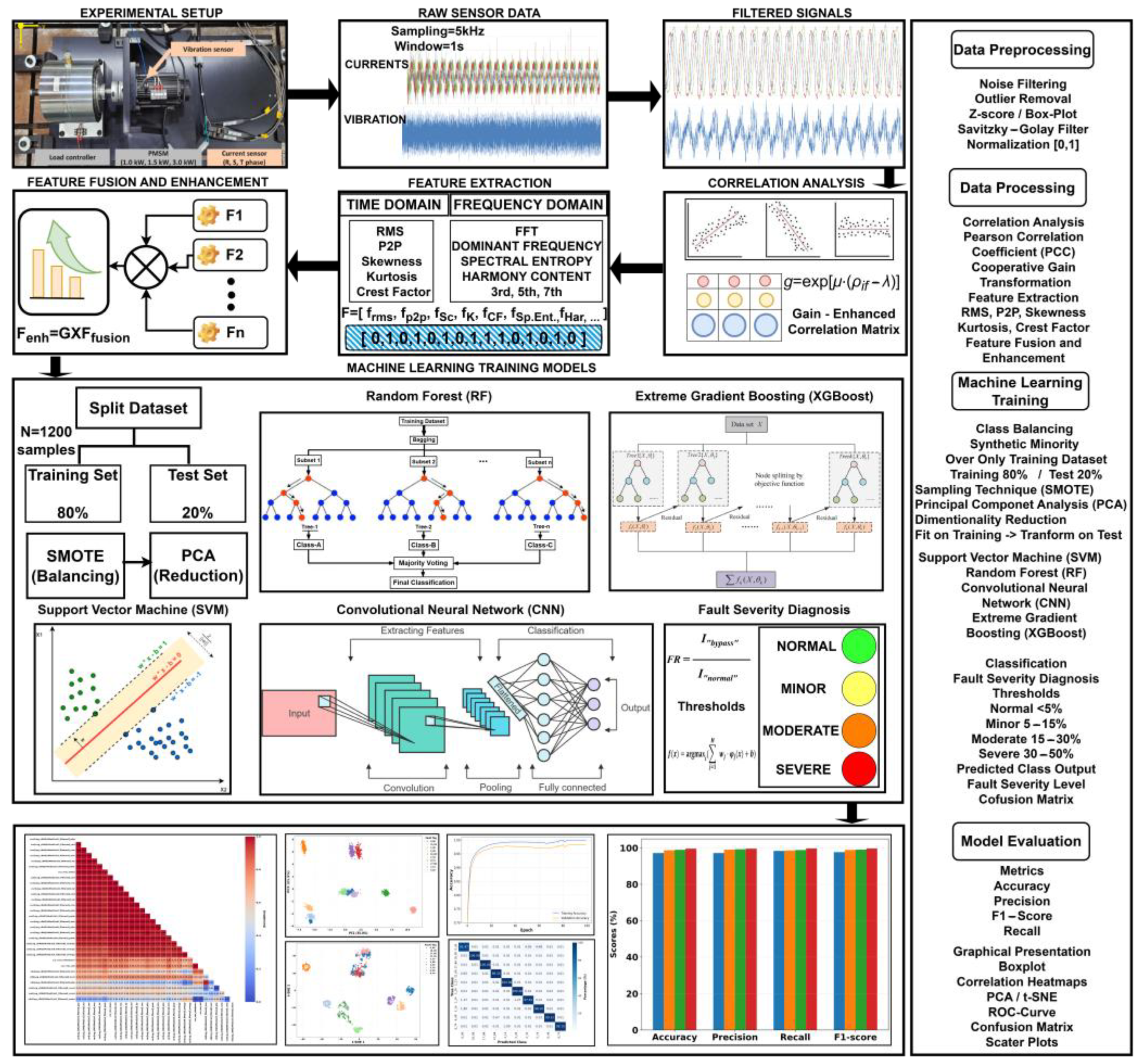

3. Proposed Methodology

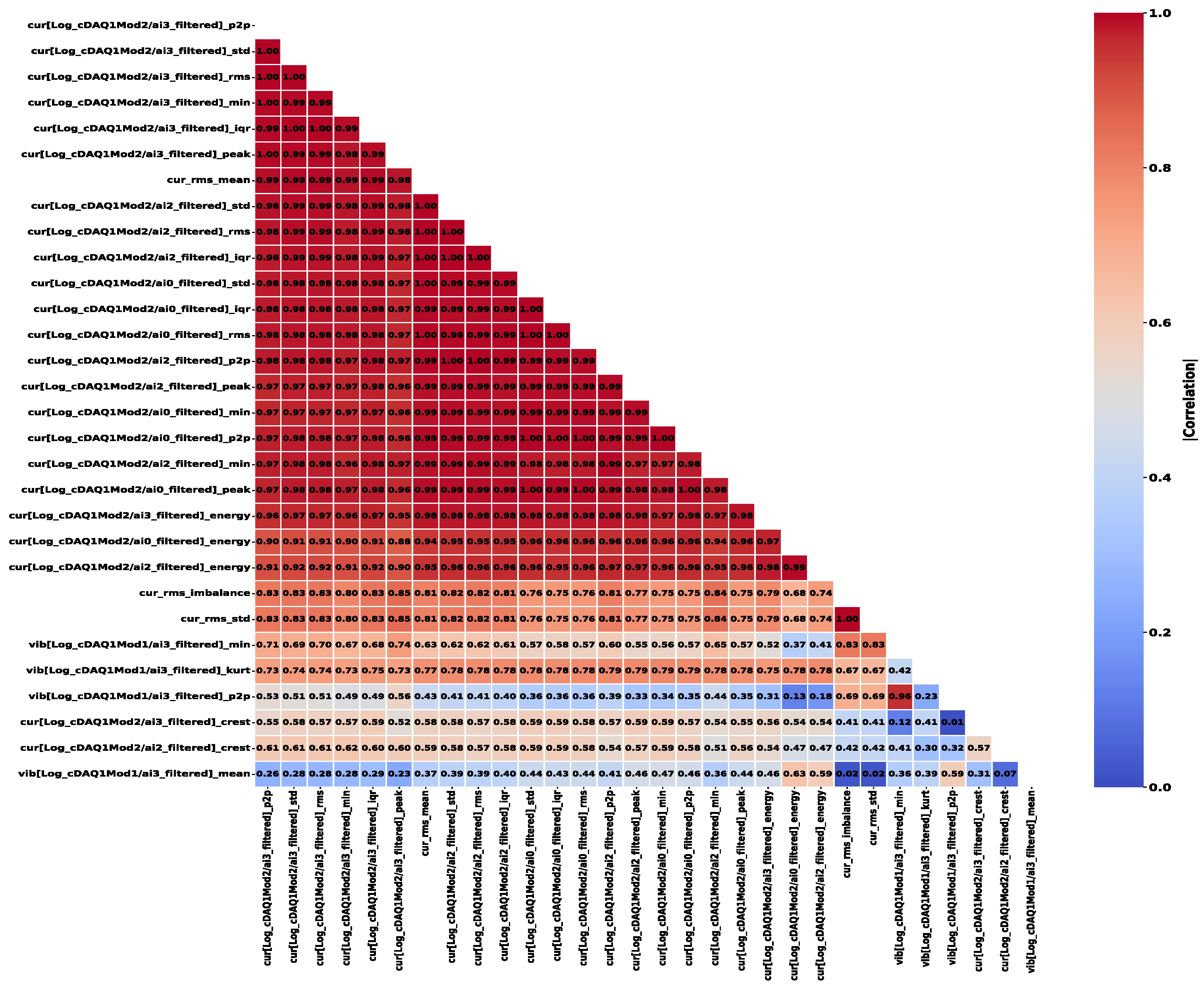

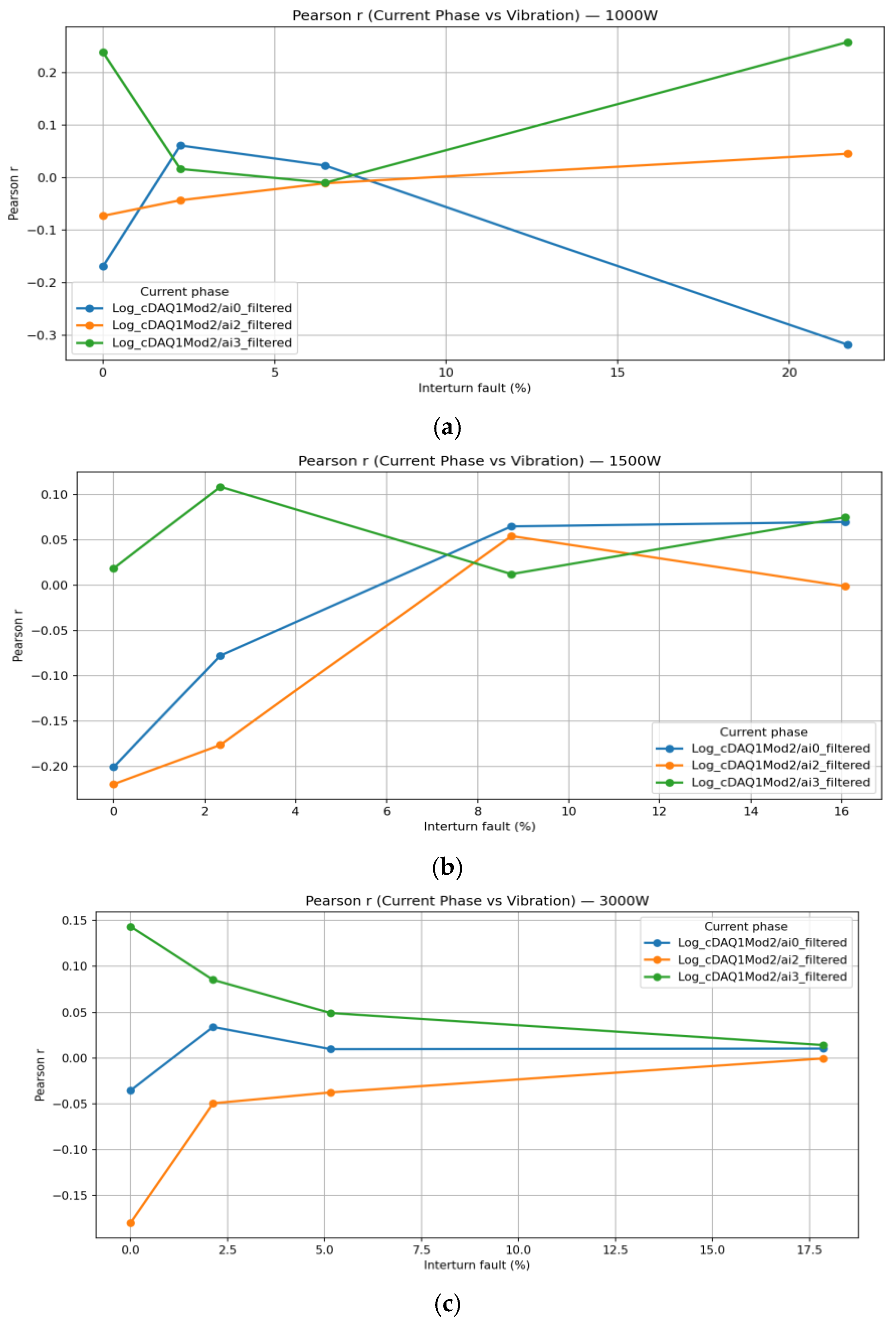

3.1. Correlation Analysis Between Vibration and Current Signals

3.2. Cooperative Gain Transformation

3.3. Mathematical Model

- Root Mean Square (RMS): Measures the magnitude of the signal.

- Peak-to-Peak (P2P): Measures the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the signal.

- Skewness and Kurtosis: Statistical measures of asymmetry and the peakedness of the signal distribution.

- Spectral Entropy: Measures the complexity of the frequency distribution.

- Dominant Frequency: The frequency with the highest power in the spectrum.

- Harmonic Analysis: Analysis of the harmonic content of the signal to detect faults.

3.4. Fault Severity Classification

4. Results

4.1. Signal Filtering

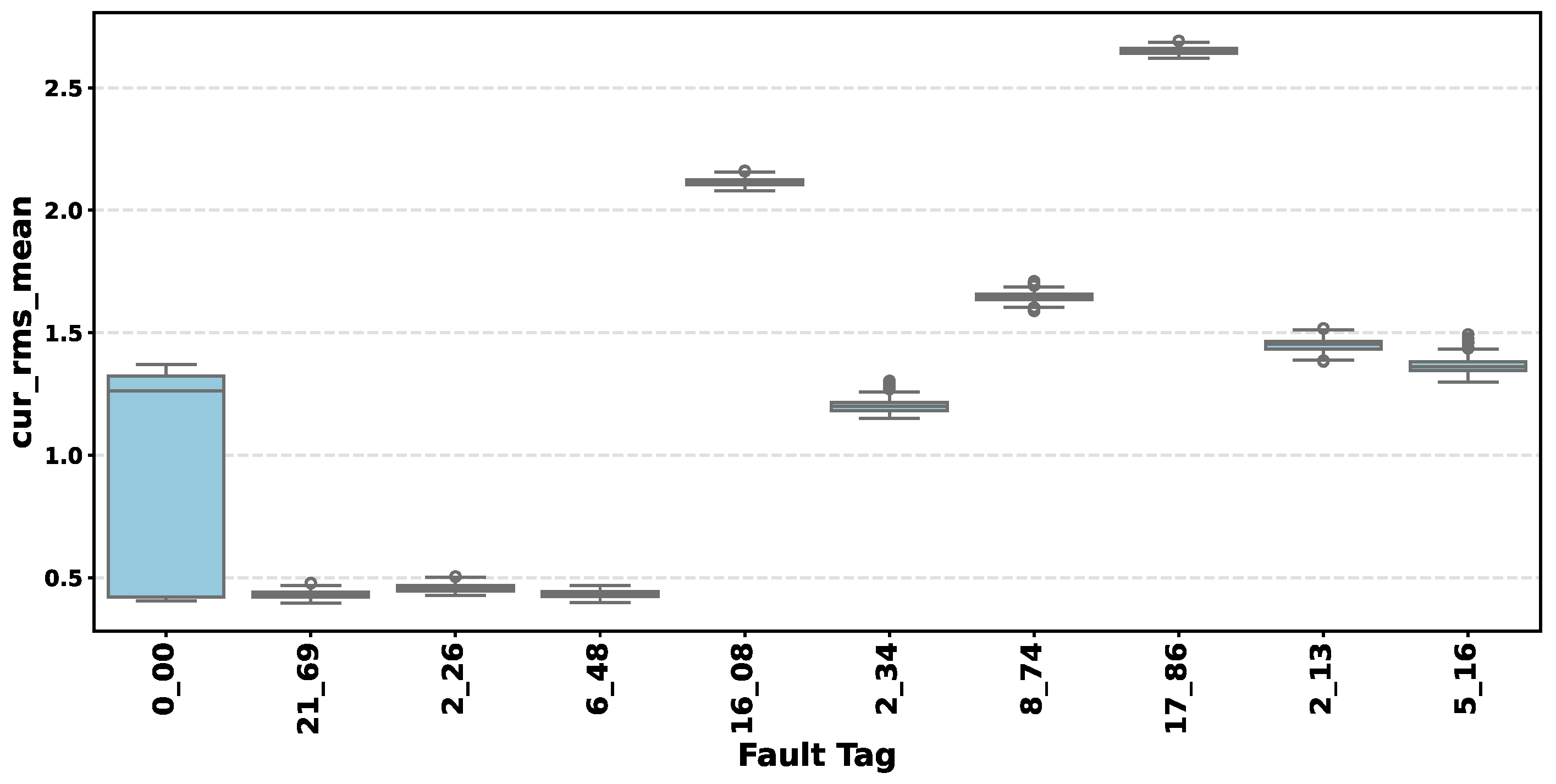

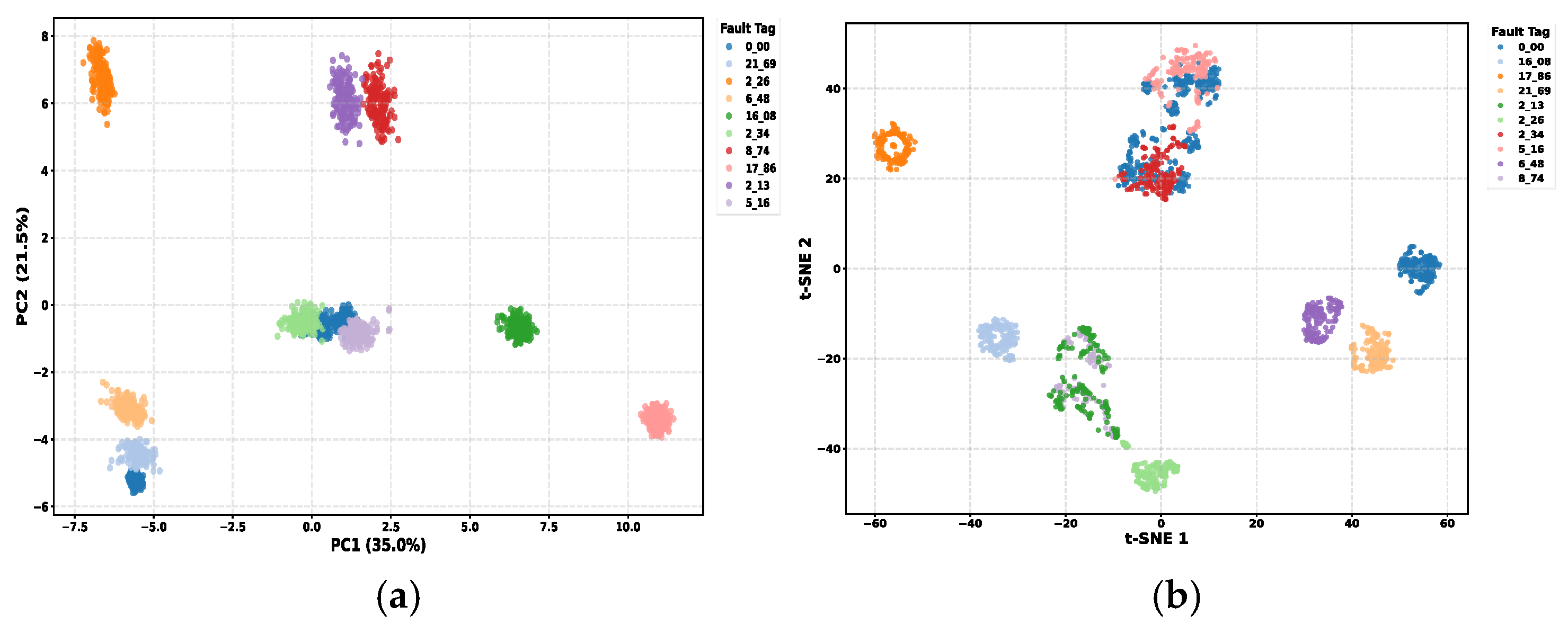

4.2. Feature Extraction

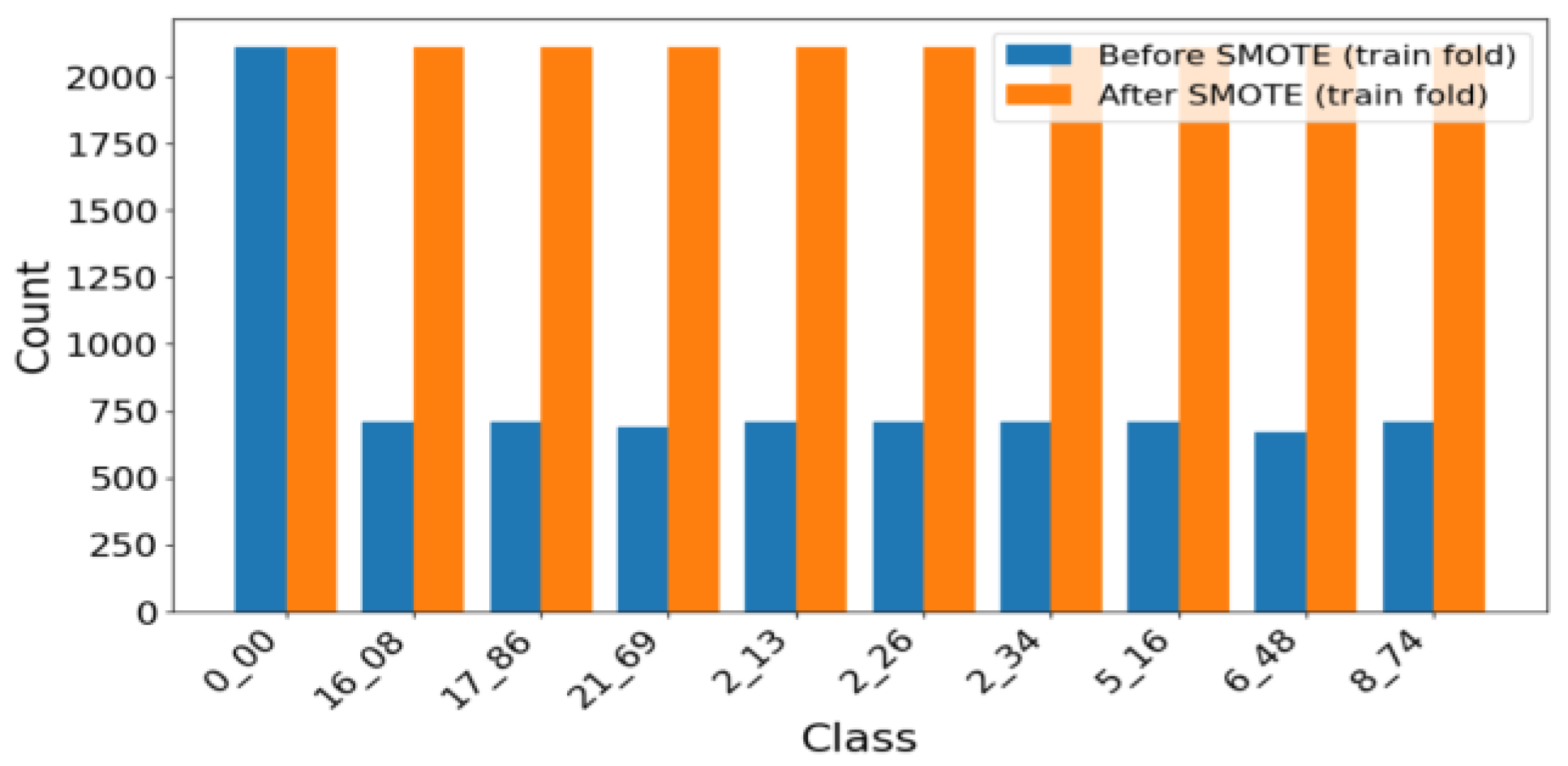

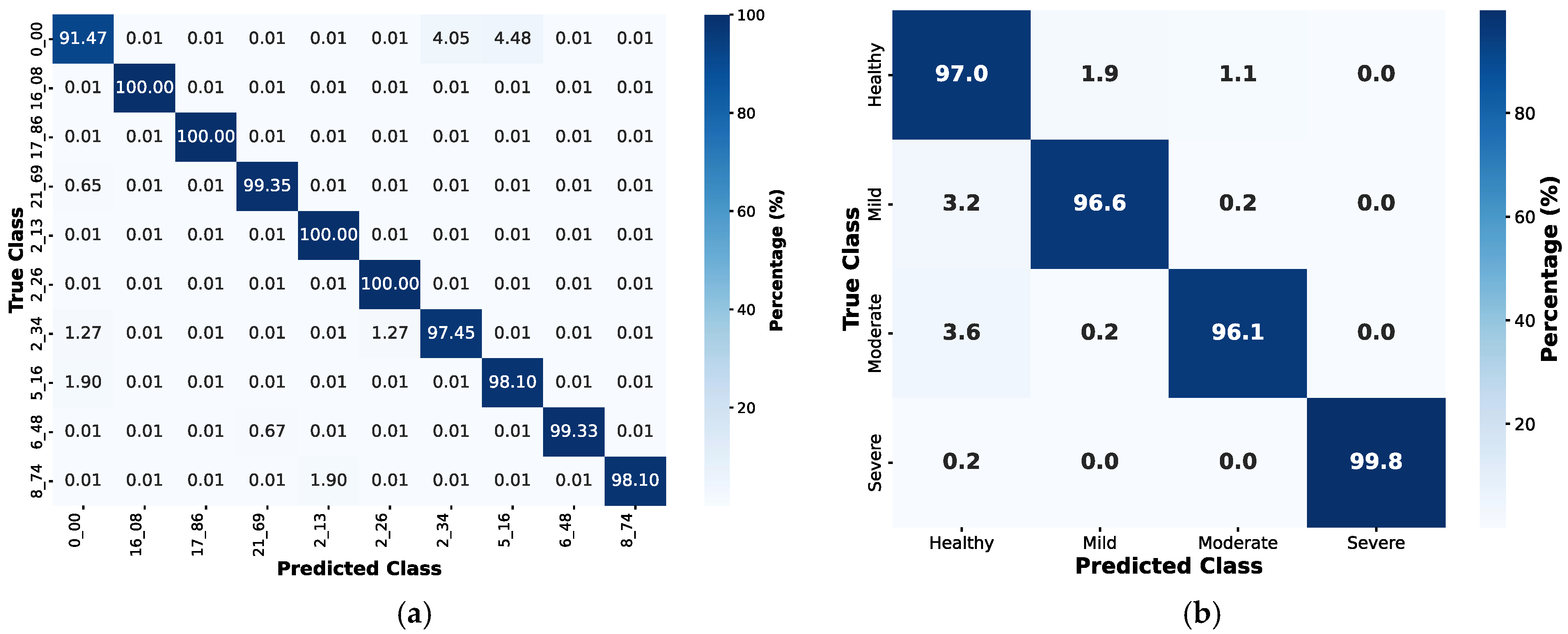

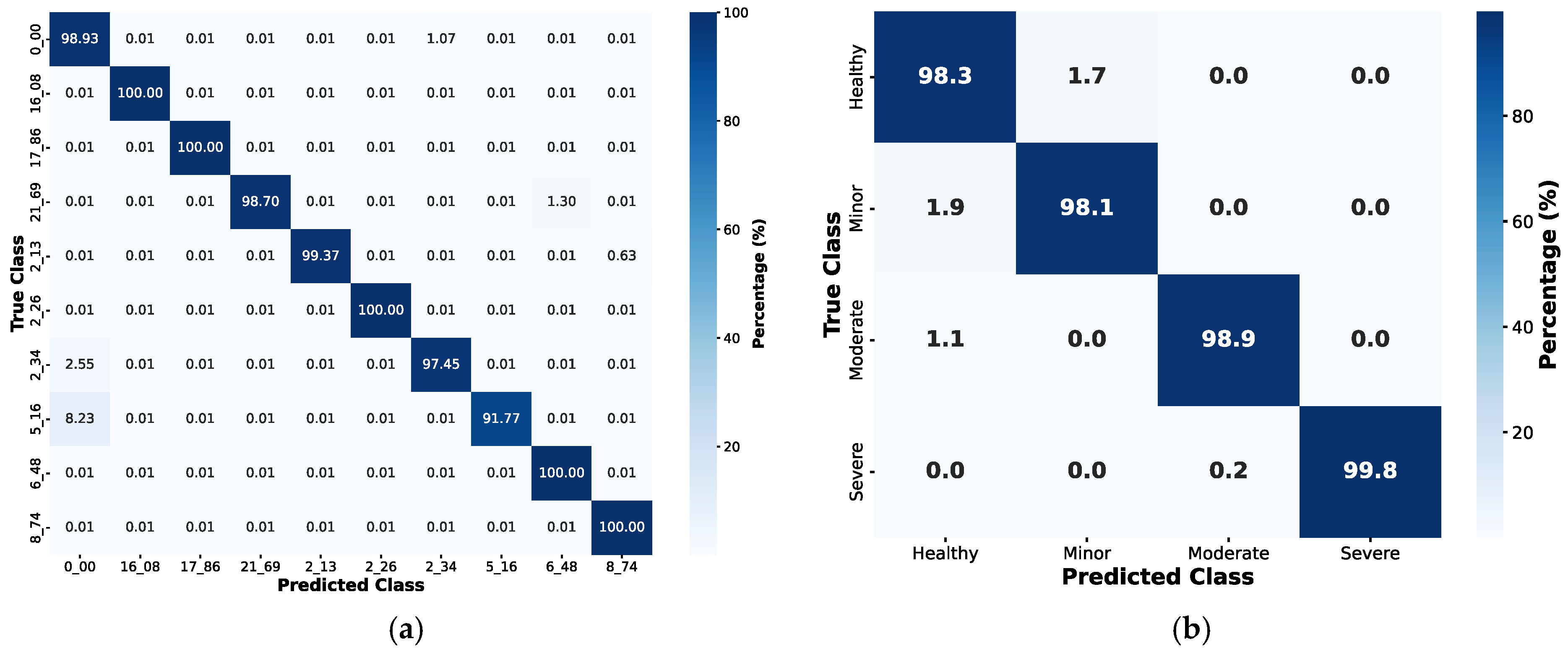

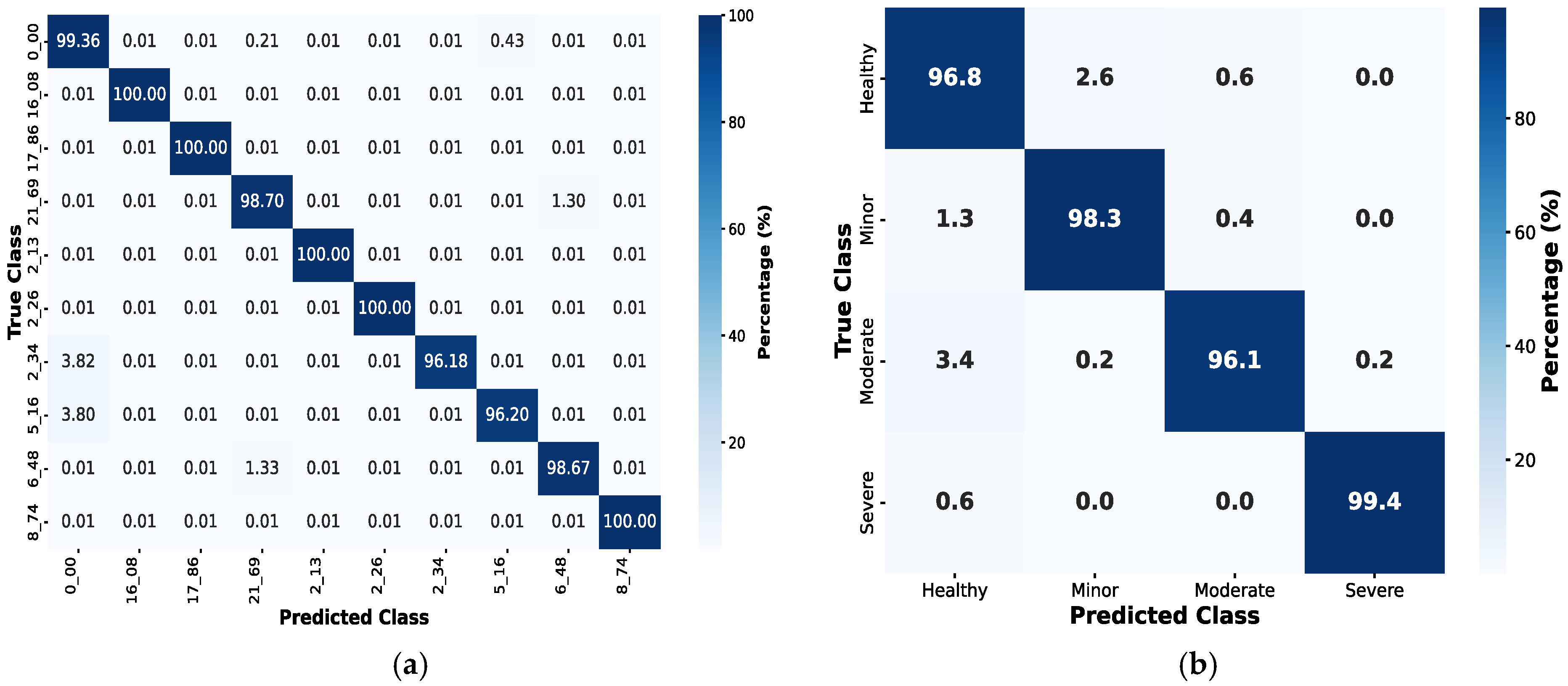

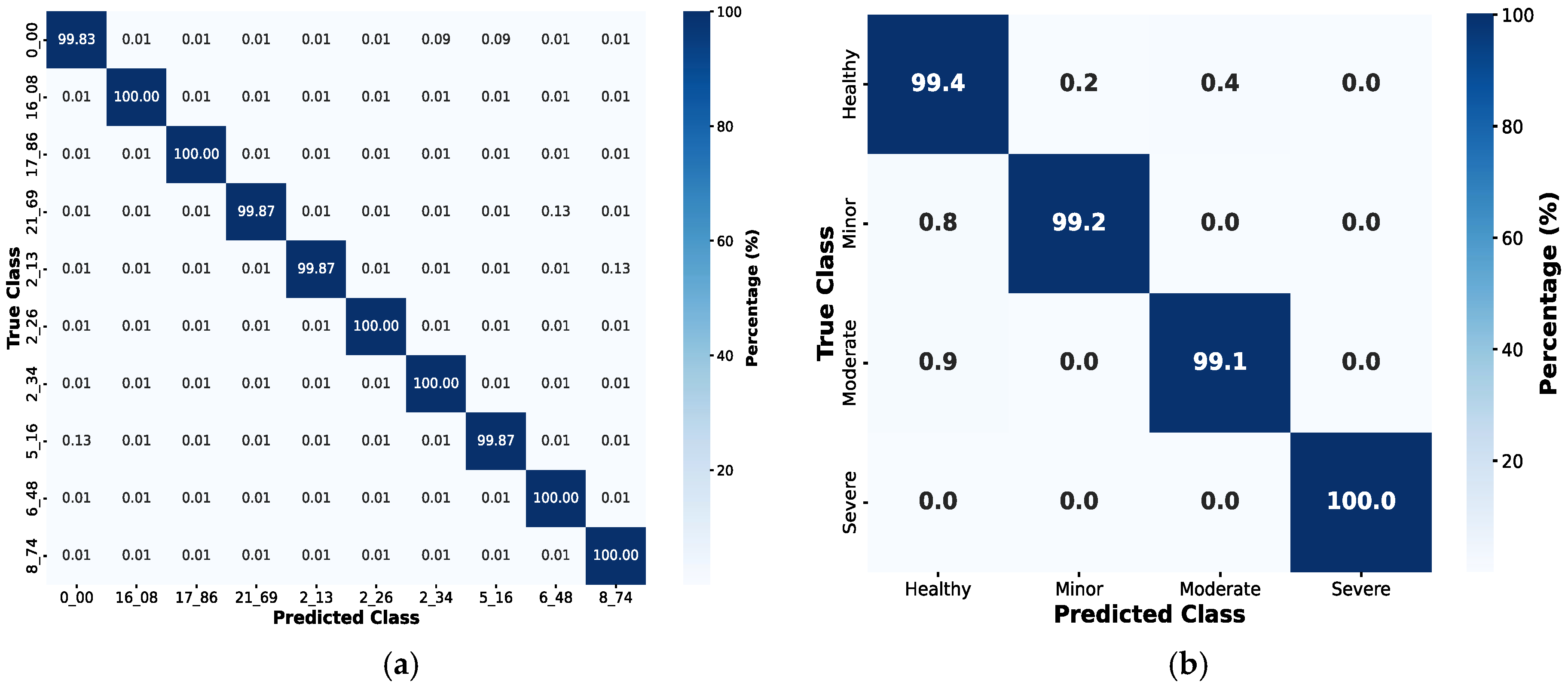

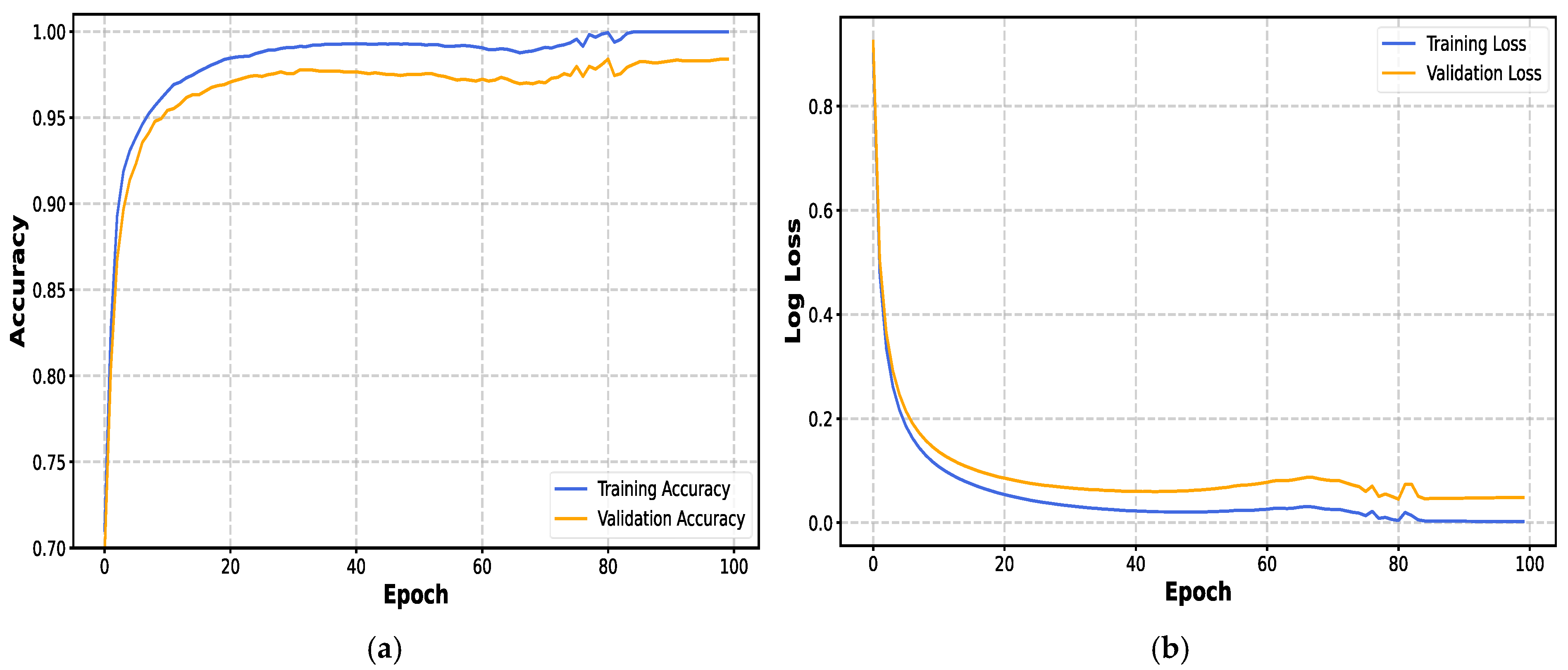

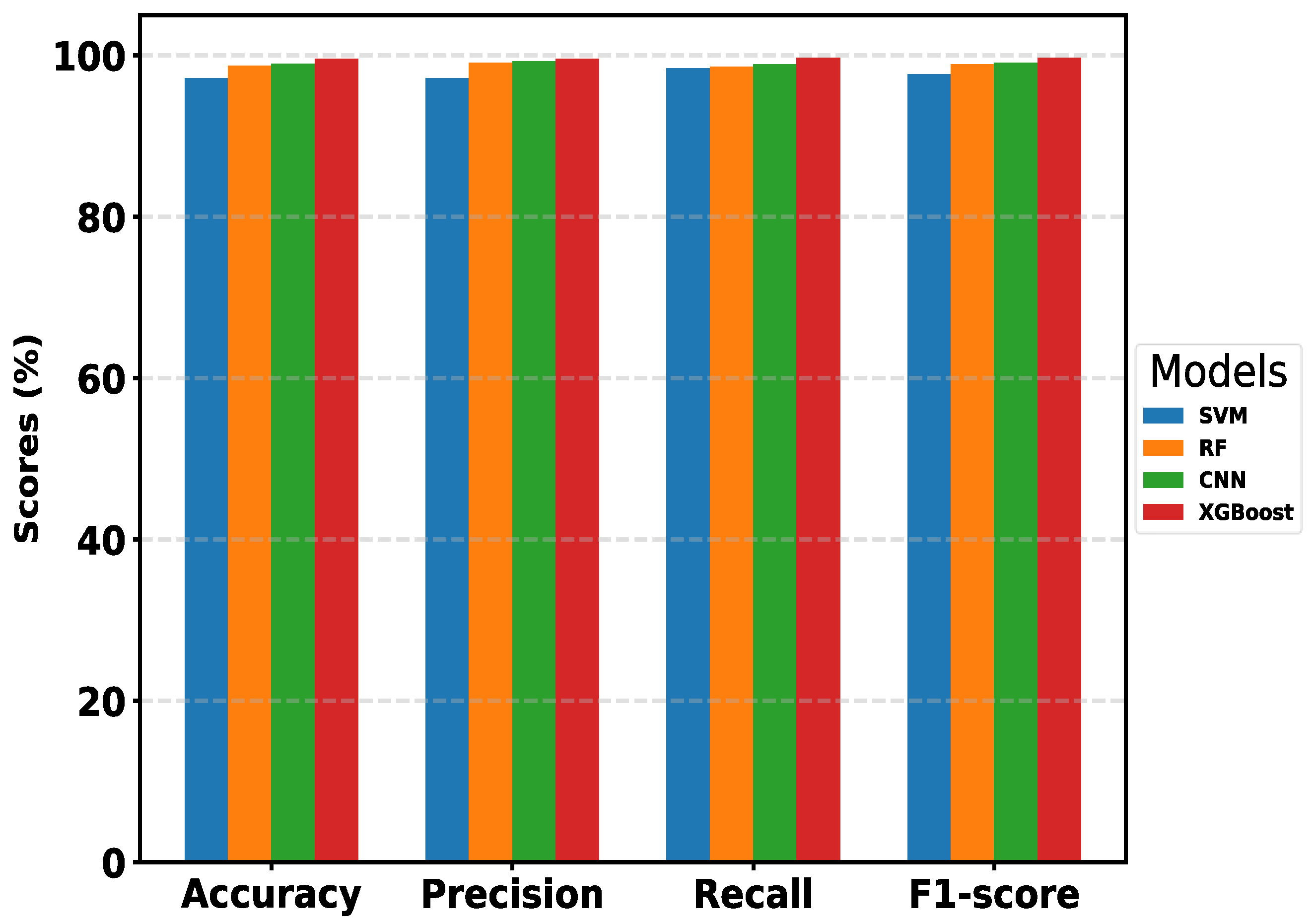

4.3. Fault Diagnosis Using Machine Learning Algorithms

5. Discussion

- Integration of additional sensors: Future research could incorporate temperature or acoustic emission sensors to enable multimodal fault detection under varying operational conditions.

- Deep learning and transfer learning approaches: Applying attention-based CNN or transfer learning models could enhance early fault identification while reducing data dependency.

- Adaptive cooperative gain: Introducing an adaptive gain mechanism that dynamically adjusts according to noise levels or load variations could further stabilize fault detection.

- Real-time embedded implementation: Deploying the proposed method on embedded/edge platforms (e.g., FPGA or Raspberry Pi) would validate its suitability for real-time industrial use.

- Predictive and reinforcement learning integration: Combining the current model with PU-learning or reinforcement learning can enable predictive maintenance and estimation of Remaining Useful Life (RUL).

- Secure IoT-based communication: Future systems should ensure encrypted and interference-free data transmission, enabling reliable cloud-based monitoring in smart factories [37].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMSM | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| STFT | Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| PCC | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

| GECF | Gain-Enhanced Correlation Fusion |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| FPSM | Flux Switching Permanent Magnet |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| RF | Random Forest |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolution Neural Network |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| ITSC | Inter Turn Short Circuit |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MCSA | Motor Current Signal Analysis |

| t-SNE | t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding |

| RUL | Remain Useful Life |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

References

- He, T.; Zhu, Z.; Eastham, F.; Wang, Y.; Bin, H.; Wu, D.; Gong, L.; Chen, J. Permanent Magnet Machines for High-Speed Applications. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergakis, A.; Salinas, M.; Gkiolekas, N.; Gyftakis, K.N. A Review of Condition Monitoring of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: Techniques, Challenges and Future Directions. Energies 2025, 18, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, V.I.; Karakatsanis, T.S.; Efstathiou, D.E. Recent Advances of Artificial Intelligence Methods in PMSM Condition Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis in Elevator Systems. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudelina, K.; Vaimann, T.; Asad, B.; Rassolkin, A.; Kallaste, A.; Demidova, G. Trends and Challenges in Intelligent Condition Monitoring of Electrical Machines Using Machine Learning. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Wylomanska, A.; Zimroz, R.; Xiang, J.; Antoni, J. Critical challenges and advances in vibration signal processing for non-stationary condition monitoring. Advan. Eng. Infor. 2025, 65, 103290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolleti, M.A.; Gentile, F.R.; Donolo, P.D.; Bossio, G.R. Online detection of interturn short-circuit fault in induction motor based on 5th harmonic current tracking using Vold-Kalman filter. Int. J. Elect. Comp. Eng. 2023, 13, 3593–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Azar, Z.; Clark, R.; Wu, Z. Fault Detection of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: An Overview. Energies 2025, 18, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Dong, X.; Chen, Y. Motor Fault Diagnostics Based on Current Signatures: A Review. IEEE Trans. Instr. Mes. 2023, 72, 3520919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yin, Z.; Yuan, D.; Yuan, M. Fault Diagnosis of Inter-turn Short Circuit of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Based on Voltage Residual Vector. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Power Electronics and Application Conference and Exposition (PEAC), Guangzhou, China, 4–7 November 2022; pp. 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.K.; Tran, M.Q.; Weng, P.Y. Fusion of Vibration and Current Signatures for the Fault Diagnosis of Induction Machines. Shock Vib. 2019, 2019, 7176482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudelina, K.; Asad, B.; Vaimann, T.; Rassolkin, A.; Kallaste, A.; Khang, H.V. Methods of Condition Monitoring and Fault Detection for Electrical Machines. Energies 2021, 14, 7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, P.; Wolkiewicz, M. Machine Learning-Based Stator Current Data-Driven PMSM Stator Winding Fault Diagnosis. Sensors 2022, 22, 9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ji, B.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Li, W. An Overview of Diagnosis Methods of Stator Winding Inter-Turn Short Faults in Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motors for Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Kong, W.; Fu, M.; Ma, J. Early-Stage Fault Diagnosis of Motor Bearing Based on Kurtosis Weighting and Fusion of Current–Vibration Signals. Sensors 2024, 24, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, R.; Liu, Z.; Peng, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S. Fault diagnosis of inter-turn short circuit in turbogenerator rotor windings based on vibration-current signal fusion. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lai, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Song, Q. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Inter-Turn Short Circuit Faults in PMSMs for Agricultural Machinery Based on Data Fusion and Bayesian Optimization. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.F.; Saleem, F.; Umar, M.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, J.-M. A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Bearing Fault Diagnosis Using Continuous Wavelet Transform and Attention-Enhanced Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction. Sensors 2025, 25, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagri, I.; Tahiry, K.; Hraiba, A.; Touil, A.; Mousrij, A. Vibration Signal Analysis for Intelligent Rotating Machinery Diagnosis and Prognosis: A Comprehensive Systematic Literature Review. Vibration 2024, 7, 1013–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan Ebrahimi, S.; Choux, M.; Huynh, V.K. Real-Time Detection of Incipient Inter-Turn Short Circuit and Sensor Faults in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives Based on Generalized Likelihood Ratio Test and Structural Analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsuga, Á.; Dineva, A. Early Detection of ITSC Faults in PMSMs Using Transformer Model and Transient Time-Frequency Features. Energies 2025, 18, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liang, S.; Wang, C. Fault Detection of Stator Inter-Turn Short-Circuit in PMSM on Stator Current and Vibration Signal. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgacem, A.M.; Hadef, M.; Ali, E.; Elsayed, S.K.; Paramasivam, P.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. Fault Diagnosis of inter-turn short circuits in PMSM based on deep regulated neural network. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2024, 18, 1991–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romdhane, M.; Naoui, M.; Mansouri, A. PMSM Inter-Turn Short Circuit Fault Detection Using the Fuzzy-Extended Kalman Filter in Electric Vehicles. Electronics 2023, 12, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Yun, S.-H.; Lim, Y.-S.; Cheong, S.; Park, Y.-H. Vibration and Current Dataset of Three-Phase Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors with Stator Faults. Data Brief 2023, 47, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Song, X.; Liao, Z.; Jia, B. Bearing Fault Feature Enhancement and Diagnosis Based on Savitzky–Golay Filtering Gramian Angular Field. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 87991–88005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Liang, G.; Huang, Z.; Song, X.; Liao, Z. Rotating Machinery Structural Faults Feature Enhancement and Diagnosis Based on Multi-Sensor Information Fusion. Machines 2025, 13, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Guan, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z. Data-Driven Based Hybrid Predictive Model for the PMSM Drive System. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Predictive Control of Electrical Drives and Power Electronics (PRECEDE), Wuhan, China, 16–19 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, G.G.B.; Tominaga, R.N.; Avila, S.L.; Machado, R.M.; Salles, M.B.C.; Carmo, B.S. Improvements in Stacking Deep Learning Models for Current and Vibration Signature Analysis in Rotating Machines. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference (IEMDC), Houston, TX, USA, 18–21 May 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacha, A.; El Idrissi, R.; Janati Idrissi, K.; Lmai, F. Comprehensive dataset for fault detection and diagnosis in inverter-driven permanent magnet synchronous motor systems. Data Brief 2025, 58, 111286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Liang, L.; Zheng, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, D. Anomaly Detection of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Based on Improved DWT-CNN Multi-Current Fusion. Sensors 2024, 24, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Zhu, N.; Peng, D.; Ren, L.; Wang, H. Deep Adaptive Wavelet Autoencoder with Mutually Independent Empirical Cumulative Distribution for Unsupervised Motor Anomaly Detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 162, 112446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, K.J.; Hsieh, M.F.; Chen, B.J.; Huang, S.F. Machine Learning for Inter-Turn Short-Circuit Fault Diagnosis in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE Trans. Mag. 2022, 58, 8204307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Cornejo, J.J.; Ibarra-Manzano, M.A.; Gonzalez-Parada, A.; Castro-Sanchez, R.; Almanza-Ojeba, D.L. Classification of inter-turn short-circuit faults in induction motors based on quaternion analysis. Measurement 2023, 222, 113680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femia, A.; Sala, G.; Vancini, L.; Rizzoli, G.; Mengoni, M.; Zarri, L. A Machine-Learning-Based Interturn Short-Circuit Diagnosis for Multi-Three-Phase Brushless Motors. IEEE J. Emer. Sel. Top. Ind. Electr. 2023, 4, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Wu, Q.; Feng, X.; Lin, Q. Research on early-stage stator fault diagnosis method for permanent magnet synchronous motors based on VMD decomposition and BiTCN-transformer parallel network. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 045439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, V.I.; Karakatsanis, T.S.; Efstathiou, D.E.; Vlachou, E.I.; Vologiannidis, S.D.; Balaska, V.E.; Gasteratos, A.C. Condition Monitoring and Fault Prediction in PMSM Drives Using Machine Learning for Elevator Applications. Machines 2025, 13, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, E.I.; Vlachou, V.I.; Efstathiou, D.E.; Karakatsanis, T.S. Overview of IoT Security Challenges and Sensors Specifications in PMSM for Elevator Applications. Machines 2024, 12, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, N.; De Luca, A.; Perfetto, D.; Lamanna, G.; Annaz, F.; De Oliveira, M. Domain-Adaptive Graph Attention Semi-Supervised Network for Temperature-Resilient SHM of Composite Plates. Sensors 2025, 25, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Symbol | PMSM I | PMSM II | PMSM III |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rated power | 1 kW | 1.5 kw | 3 kW | |

| Input voltage (AC) | V | 380 V | 380 V | 380 V |

| Frequency | f | 60 Hz | 60 Hz | 60 Hz |

| Number of phases | Ph | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Number of Pole | p | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Nominal current | 1.6 A | 2.4 A | 4.8 A | |

| Rated speed | 3000 rpm | 3000 rpm | 3000 rpm | |

| Rated torque | 3.18 Nm | 4.77 Nm | 9.55 Nm | |

| Magnetic flux density | B | 400 mT | 350 mT | 300 mT |

| Rotor inertia | J | 2.07 kgm2 | 7.48 kgm2 | 14.34 kgm2 |

| Inter-turn resistance value | Rit | 0.1385 Ohm | 0.0958 Ohm | 0.1087 Ohm |

| Parameters | Peak (A) | Rms (A) | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000_Normal | 1.15 | 0.43 | 0.073 | −1.33 |

| 1000_2% ITSC | 6.57 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 7.58 |

| 1000_6% ITSC | 1.45 | 0.46 | −0.044 | −1.03 |

| 1000_21% ITSC | 1.50 | 0.48 | 0.097 | −1.19 |

| 1500_Normal | 9.03 | 1.38 | 0.015 | −0.63 |

| 1500_2% ITSC | 8.98 | 1.34 | 0.075 | 0.36 |

| 1500_8% ITSC | 9.72 | 1.74 | 0.057 | −0.43 |

| 1500_16% ITSC | 9.19 | 2.25 | −0.016 | −1.25 |

| 3000_Normal | 7.25 | 1.45 | −0.070 | −1.08 |

| 3000_2% ITSC | 6.18 | 1.52 | 0.036 | −1.26 |

| 3000_5% ITSC | 9.54 | 1.52 | 0.003 | −0.16 |

| 3000_17% ITSC | 9.59 | 2.92 | 0.014 | −1.33 |

| Parameters | Peak (A) | Rms (A) | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000_Normal | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.077 | −1.52 |

| 1000_2% ITSC | 1.05 | 0.50 | −0.047 | −1.46 |

| 1000_6% ITSC | 0.90 | 0.45 | −0.048 | −1.38 |

| 1000_21% ITSC | 0.95 | 0.46 | 0.10 | −1.39 |

| 1500_Normal | 2.27 | 1.33 | −0.009 | −1.48 |

| 1500_2% ITSC | 2.35 | 1.27 | −0.009 | −1.44 |

| 1500_8% ITSC | 2.84 | 1.67 | −0.008 | −1.48 |

| 1500_16% ITSC | 3.70 | 2.20 | −0.005 | −1.50 |

| 3000_Normal | 2.43 | 1.40 | −0.065 | −1.48 |

| 3000_2% ITSC | 2.38 | 1.48 | 0.029 | −1.47 |

| 3000_5% ITSC | 2.82 | 1.45 | −0.057 | −1.44 |

| 3000_17% ITSC | 4.75 | 2.88 | 0.023 | −1.45 |

| Parameters | Peak (g) | Rms (g) | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000_Normal | 1.77 | 0.32 | −0.10 | 0.23 |

| 1000_2% ITSC | 0.085 | 0.036 | 0.37 | −1.02 |

| 1000_6% ITSC | 2.28 | 0.47 | 0.028 | 0.87 |

| 1000_21% ITSC | 1.77 | 1.67 | −0.061 | −0.31 |

| 1500_Normal | 1.35 | 0.48 | −0.010 | −0.60 |

| 1500_2% ITSC | 1.27 | 0.50 | 0.001 | −0.87 |

| 1500_8% ITSC | 0.086 | 0.036 | 0.37 | −1.01 |

| 1500_16% ITSC | 1.21 | 0.42 | 0.024 | −0.74 |

| 3000_Normal | 1.09 | 0.37 | −0.048 | −0.70 |

| 3000_2% ITSC | 0.083 | 0.036 | 0.39 | −0.98 |

| 3000_5% ITSC | 1.00 | 0.35 | −0.05 | −0.81 |

| 3000_17% ITSC | 0.76 | 0.22 | −0.40 | −0.21 |

| Parameters | Peak (g) | Rms (g) | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000_Normal | 0.34 | 0.12 | −0.45 | 0.26 |

| 1000_2% ITSC | 0.084 | 0.033 | 0.41 | −0.58 |

| 1000_6% ITSC | 0.34 | 0.089 | −0.78 | 0.92 |

| 1000_21% ITSC | 0.30 | 0.30 | −0.58 | −0.13 |

| 1500_Normal | 0.077 | 0.020 | −0.27 | −0.12 |

| 1500_2% ITSC | 0.094 | 0.018 | −0.091 | −0.093 |

| 1500_8% ITSC | 0.083 | 0.033 | 0.41 | −0.57 |

| 1500_16% ITSC | 0.083 | 0.024 | −0.22 | −0.31 |

| 3000_Normal | 0.094 | 0.031 | 0.19 | −0.26 |

| 3000_2% ITSC | 0.082 | 0.033 | 0.44 | −0.51 |

| 3000_5% ITSC | 0.10 | 0.029 | 0.18 | −0.47 |

| 3000_17% ITSC | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.11 | −1.20 |

| Model | Hyperparameter | Values Tested | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | Kernel C Gamma | RBF [0.1, 1, 10] [0.01, 0.1, 1] | Grid search with 5-fold CV |

| Random Forest | n estimators max depth | [50, 100, 200] [None, 10, 20, 30] | Random search with 5-fold CV |

| CNN | Number of Layers Neurons per Layer Learning rate Batch size | [3, 4, 5] [64, 128, 256] [0.001, 0.01, 0.1] [16, 32, 64] | Random search with 5-fold CV |

| XGBoost | Learning rate n estimators max depth Subsample | [0.01, 0.1, 0.3] [50, 100, 200] [3, 6, 10] [0.8, 1.0] | Grid search with 5-fold CV |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Confidence Interval (95%) | McNemar p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | RF | CNN | XGBoost | ||||||

| SVM | 97.2% | 0.972 | 0.984 | 0.977 | [91.0%, 93.2%] | - | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.008 |

| RF | 98.7% | 0.991 | 0.986 | 0.989 | [90.0%, 92.5%] | 0.001 | - | 0.035 | 0.012 |

| CNN | 99.0% | 0.993 | 0.989 | 0.991 | [90.3%, 92.8%] | 0.023 | 0.035 | - | 0.014 |

| XGBoost | 99.6% | 0.996 | 0.997 | 0.997 | [91.2%, 93.6%] | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.014 | - |

| Method | Signals | Classifier | Accuracy | Comput. Cost | Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | Current + Vibration | Gain-Enhanced Fusion + ML Classifiers | 97–100% | Low | Improved sensitivity via signal correlation, low computational cost |

| [22] | Current + Vibration | Deep Regulated Neural Network | 91–97% | High | Data fusion with ConvLSTM regulation for high accuracy |

| [32] | Current d-q axis | SVM + CNN | 98–99.7% | Medium High | Hybrid model, early ITSC detection with limited data |

| [33] | Current | Decision tree | 79.48–99.9% | Low | Quaternion analysis, multi-class ITSC classification |

| [34] | Voltage + FEA | SVM, KNN, MLP, XGBoost, GNB | 96.2–99% | High | Multi-phase PMSM diagnosis, FEM-based dataset, SVM most robust |

| Model | File Size (MB) | Mean ms/Sample | p95 ms/Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM (RBF) + SMOTE | 2.2063 | 0.726339 | 1.153855 |

| RF + SMOTE | 30.5683 | 30.004478 | 42.729025 |

| CNN + SMOTE | 6.2532 | 4.502312 | 6.253210 |

| XGBoost + SMOTE | 4.7017 | 1.480621 | 2.496020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vlachou, V.I.; Karakatsanis, T.S.; Kudelina, K.; Efstathiou, D.E.; Vologiannidis, S.D. Gain-Enhanced Correlation Fusion for PMSM Inter-Turn Faults Severity Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Machines 2026, 14, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010134

Vlachou VI, Karakatsanis TS, Kudelina K, Efstathiou DE, Vologiannidis SD. Gain-Enhanced Correlation Fusion for PMSM Inter-Turn Faults Severity Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Machines. 2026; 14(1):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010134

Chicago/Turabian StyleVlachou, Vasileios I., Theoklitos S. Karakatsanis, Karolina Kudelina, Dimitrios E. Efstathiou, and Stavros D. Vologiannidis. 2026. "Gain-Enhanced Correlation Fusion for PMSM Inter-Turn Faults Severity Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms" Machines 14, no. 1: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010134

APA StyleVlachou, V. I., Karakatsanis, T. S., Kudelina, K., Efstathiou, D. E., & Vologiannidis, S. D. (2026). Gain-Enhanced Correlation Fusion for PMSM Inter-Turn Faults Severity Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Machines, 14(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010134