1. Introduction

Rotary transmission systems are fundamental in many industrial and vehicular applications, as they adapt the working point in terms of torque and angular speed of two or more rotating machines. While most of the transmission systems are geared mechanically, magnetic gears have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional ones. Magnetic transmissions exploit the contactless interaction between magnetic fields to transfer torque [

1]. Furthermore, they inherently offer other advantages like reduced acoustic noise and vibration, reduced wear, and intrinsic overload protection [

2]. These features make magnetic gears attractive in applications where reliability and efficiency are critical, including wind energy systems, electric vehicles, and actuators [

3]. Among the various magnetic gear topologies, the coaxial magnetic gear (CMG) is particularly appealing due to its compactness [

4], high torque density, and suitability for integration with electrical machines [

5].

Despite these advantages, the practical deployment of CMGs remains limited, primarily due to challenges in their design and performance prediction [

6,

7]. Finite element analysis (FEA) has become the standard approach for evaluating magnetic gear characteristics [

8]. While three-dimensional (3D) FEA provides the most accurate predictions by accounting for leakage flux and axial end effects, it is computationally demanding and unsuitable for multiple parametric sweeps or optimization studies. On the other hand, two-dimensional (2D) FEA is computationally efficient but tends to overestimate torque capability, as it neglects axial end effects [

9]. The literature confirms that these phenomena play a significant role in CMGs, especially due to the relatively short active length of these devices [

3,

10]. Consequently, there is a compromise between fast but simplified models and accurate but computationally expensive simulations, which hinders the design and optimization of CMGs. To overcome this trade-off, several strategies have been proposed in the literature. Analytical and lumped magnetic equivalent circuit models have been proposed to offer rapid evaluation and design intuition [

11], but the linear material assumption can underestimate saturation effects and loss mechanisms [

12]. Analytical models offer much faster computation times than FEA at the cost of losing accuracy and modeling flexibility [

13]. These methods improve design robustness, but their implementation often requires careful calibration between models.

This study proposes a hybrid design and optimization framework for CMGs. It combines an initial optimization step based on genetic algorithms and 2D FEA. Subsequently, 3D FEA models are exploited to refine the design, considering end effects. The method is applied to a speed multiplier for vehicle chassis actuators.

The sequel of this work is organized as follows.

Section 2 outlines the working principle of the studied solution. Then,

Section 3 presents the design methodology.

Section 4 applies the methodology to a particular case study and discusses the results in terms of average transmitted torque, torque ripple, unbalance forces, and efficiency, comparing these outcomes between 3D and 2D models. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the work.

2. Operating Principle and Topology Selection

High torque density and intrinsic overload protection make magnetic gears suitable for their use in multiple applications, such as automotive actuators [

14], wind turbines [

15], and aircraft propulsion [

16]. Moreover, the magnetic gear’s contactless torque transmission yields favorable performance in acoustic noise when compared against traditional mechanical gears [

7].

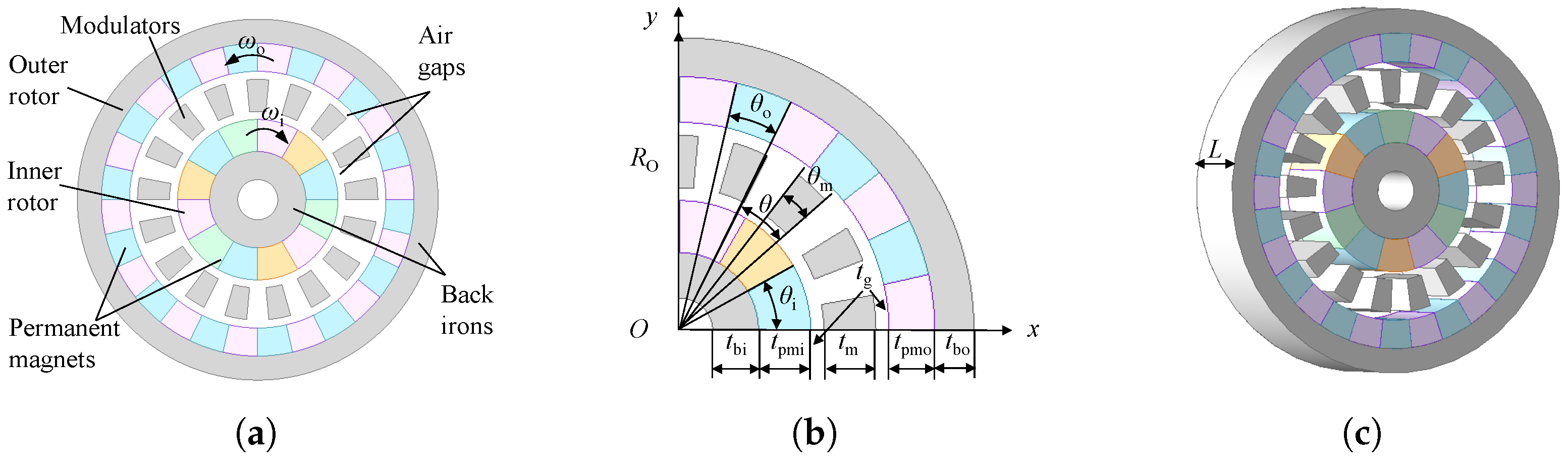

In this paper, a coaxial magnetic gear (CMG) with surface-mounted permanent magnets (PMs) is investigated as a replacement for the conventional mechanical gearbox in an automotive chassis actuator [

17], aiming to achieve contactless torque transmission, reduced noise, and enhanced energy efficiency. The magnetic gear setup is shown in

Figure 1a; it is divided into three components: (i) an inner rotor with

pole pairs and angular speed

, which serves as the high-speed shaft; (ii) an outer rotor with

pole pairs and angular speed

, used as the low-speed shaft; and (iii) an intermediate ferromagnetic modulator stage (cage rotor) with

pole pieces.

Figure 1b,c show the geometric parameters used in this study,

and

represent the permanent-magnet (PM) thickness in the inner and outer rotor, respectively;

and

are the inner and outer back-iron thickness;

is the modulator thickness;

is the thickness of each of the two air gaps; the outer rotor radius is

;

and

are the angular spans of the inner and outer PMs;

, with

being the modulator angular span.

and

denote the number of segments per pole for inner and outer rotors. The parameters shown in

Table 1 can be selected in a preliminary phase [

18]. Hence, they remain unchanged during the 2D optimization and 3D validation in the following sections.

The CMG offers multiple operating modes depending on which member is fixed. When the modulators are fixed, the transmission ratio

is given by [

11]

where the minus sign indicates that the inner and outer rotors rotate in opposite directions. The inner and outer rotors operate as the low-speed and high-speed rotors, respectively, and the absolute transmission ratio is

. Furthermore, the number of pole pieces on the modulation stage should be [

19]

In this work, modulators are selected as the stationary member, as this configuration enables a more compact and mechanically robust integration into an automotive chassis actuator. The objective of this study is not to identify globally optimal pole combinations but to evaluate geometric optimization trends under a fixed harmonic mode.

The instantaneous power balance of the magnetic gear stage can be expressed as

where

,

, and

are the torques experienced by the inner rotor, outer rotor, and modulators, respectively.

and

are the inner and outer rotor speeds, respectively. The modulators are stationary, therefore, they do not contribute to mechanical power.

represents the total power loss of the system.

The volumetric torque density (VTD) is defined in this work as a volume-based performance index, following a commonly adopted definition in the magnetic gear literature [

7,

20,

21,

22].

where

is the maximum torque,

L is the axial stack length, and

is the outer rotor radius.

This definition of VTD follows common practice in literature and represents the torque normalized by the total cylindrical envelope volume of the magnetic gear. It should be noted that electromagnetic torque is physically produced by shear stresses. The present definition represents a global packaging-level torque density and may overestimate the local shear-based torque density, which depends on the effective radius.

One of the most important measures of a magnetic gear’s performance is its stall torque, also denoted as maximum or pull-out torque. Pole slipping between the rotors results from the magnetic coupling’s inability to sustain synchronous functioning when the applied load goes beyond this limit [

23]. This phenomenon emphasizes how crucial it is to assess the torque limit in the design phase to guarantee functionality under known loads.

With the selected dimensions and parameters for the coaxial radial flux magnetic gear model, 2D finite-element simulations are set up in Ansoft Maxwell 2025R1. The starting point of the simulation was obtained from the unloaded (no-external-torque) condition, which is used solely to initialize the solution. Then, the stall torque is calculated as a function of mechanical angle when only the inner rotor is rotating.

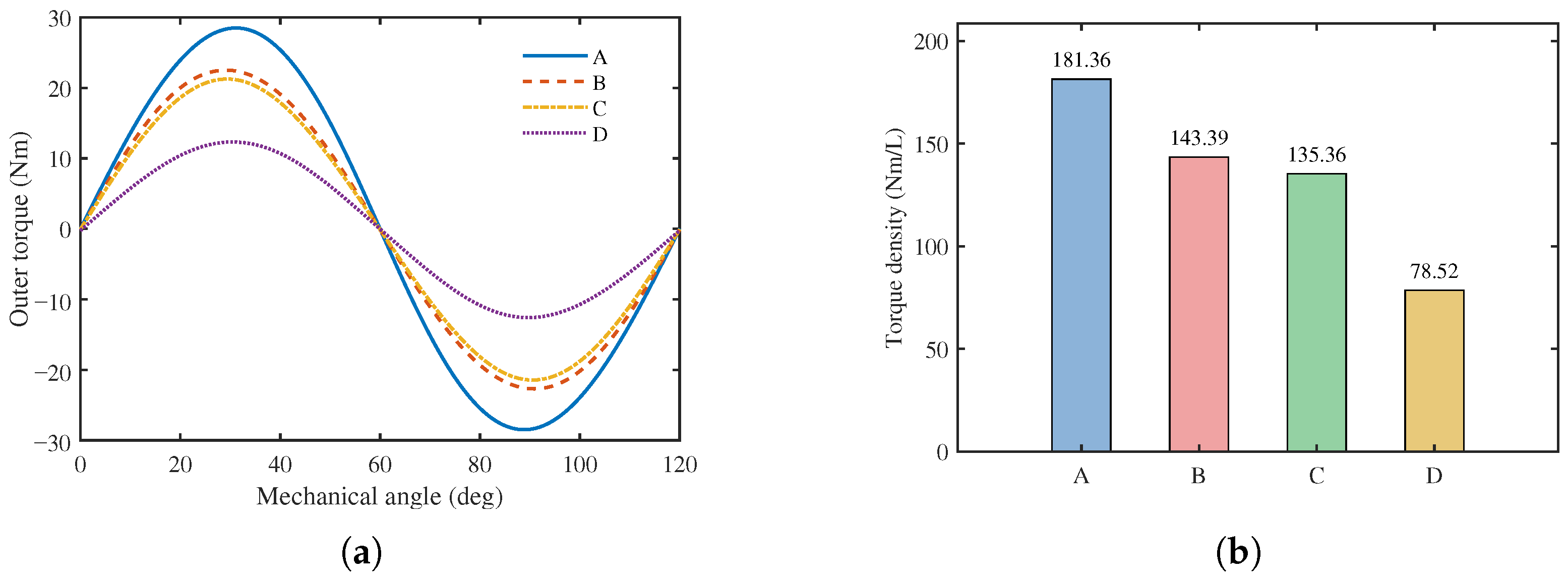

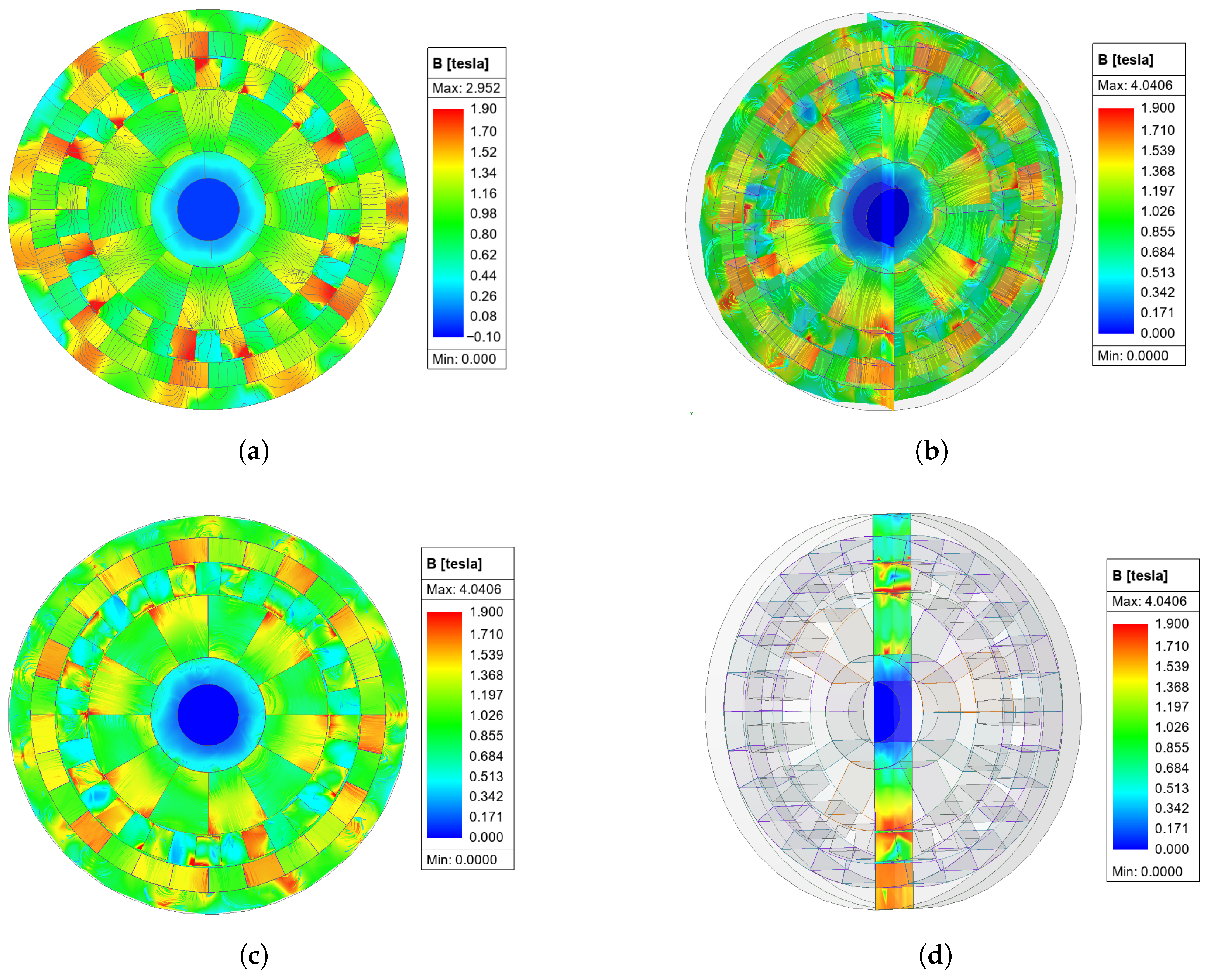

Four CMG topologies were evaluated under identical geometric and material constraints, as shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2a illustrates a topology with Halbach PM arrays on both rotors, with two segments per pole (

,

);

Figure 2b uses a Halbach array only for the inner rotor, with two segments per pole on inner rotor and one segment per pole on outer rotor (

,

);

Figure 2c exhibits pure radial magnetization on both rotors i.e., one segment per pole both rotors (

,

);

Figure 2c exploits tangential magnetization on both rotors, with one segment per pole in both cases (

,

). The torque angle curves and volumetric torque densities are shown in

Figure 3. It can be seen that the Halbach array delivers the highest torque performance, with a torque density of 181.36 Nm/L, followed by the Habach array on the inner rotor, with a torque density of 143.39 Nm/L. Despite its advantage in VTD, the Halbach array both rotors requires a significantly large number of small PM pieces on the outer rotor. Its practical implementation is hindered by the high part count and tight assembly tolerances, more complex magnetization, increased risk of chipping, rotor unbalance at speed, and higher cost [

19]. The Halbach array on only the inner rotor offers a more favorable trade-off, as it retains a competitive torque waveform and VTD while substantially simplifying the rotor build and improving robustness. Therefore, the Halbach array on the inner rotor is selected for subsequent optimization and 3D validation. The other two types have significantly lower torque densities and are therefore not considered.

3. Design Method

3.1. Finite Element Modeling

FEA has been widely used for magnetic transmissions since the early works of the 90s [

24] and remains the standard tool for accurate nonlinear evaluation. This study proposes full coaxial magnetic gear models that solve the magnetoquasistatic Maxwell equations using the

–

formulation with nonlinear materials [

25]. 2D and 3D models are built in cylindrical coordinates; the outer boundary is magnetically insulated, and periodicity is applied where appropriate. Nonlinear

B-

H properties are assigned to steel domains; the inner back iron is solid, while the modulators and outer back irons employ homogenized laminations (0.35 mm) [

26]. Demagnetization effects are inherently captured by the solver when the local magnetic field approaches or exceeds the intrinsic coercivity. PMs are grade N50 NdFeB, consistent with prior magnetic gear prototypes that included this material for high torque density [

27]. Kinematics are set to follow the absolute transmission ratio,

calculated with Equation (

1), through sliding bands in 2D, and rotating subdomains in 3D [

28]. Domains are meshed with quadratic elements with local refinement in the air gaps, at PM edges, and near modulator tips. Solutions are computed in the time domain to identify the dominant electrical harmonics. Torque is computed using the Maxwell stress tensor and losses are calculated from the field solution [

29]. Both 2D and 3D models are built in cylindrical coordinates to match the coaxial geometry. The computational domain is truncated with magnetic insulation at the outer boundary, while periodicity is imposed where appropriate.

In this study, the second-order elements with targeted mesh refinement were employed. In the 2D model, the refinement is concentrated along the air gap boundaries and at the permanent-magnet–air interfaces to ensure accurate torque prediction. In the 3D model, additional refinement is introduced at the PM edges, the modulator surfaces, and across the full axial extent of the air gap, where flux fringing and end effects significantly influence torque ripple and eddy current loss. This mesh strategy guarantees consistent accuracy in resolving the torque transmission and loss evaluation.

3.2. Losses and Efficiency

The Bertotti iron loss separation model was used to calculate the iron loss,

, which can be divided into three parts: hysteresis loss, eddy currents, and excess [

29,

30].

where

collects the steel regions (e.g., inner and outer back irons and modulators),

is the volume of the region,

r,

is the magnitude of the

th harmonic of the local flux density,

is the fundamental electrical frequency, and

are material coefficients.

The excess losses are typically a minor component of the overall iron loss [

31]. Therefore, they are neglected in this study. Permanent magnets (PMs) eddy current loss is computed via the time domain

(equivalently

) volume integral [

32]. Conversely, a hybrid approach to evaluate eddy current losses in PMs [

33] is exploited. An equivalent current sheet is first obtained from a 2D analytical model, which is then applied in a 3D FEA to capture end effects. The eddy current loss in PMs over one electrical period

is

where

is the PMs volume,

is the electrical period,

J is the eddy current density (A/m

2),

is the electrical conductivity of the PM (S/m), and

is the instantaneous volumetric eddy current loss density (W/m

3).

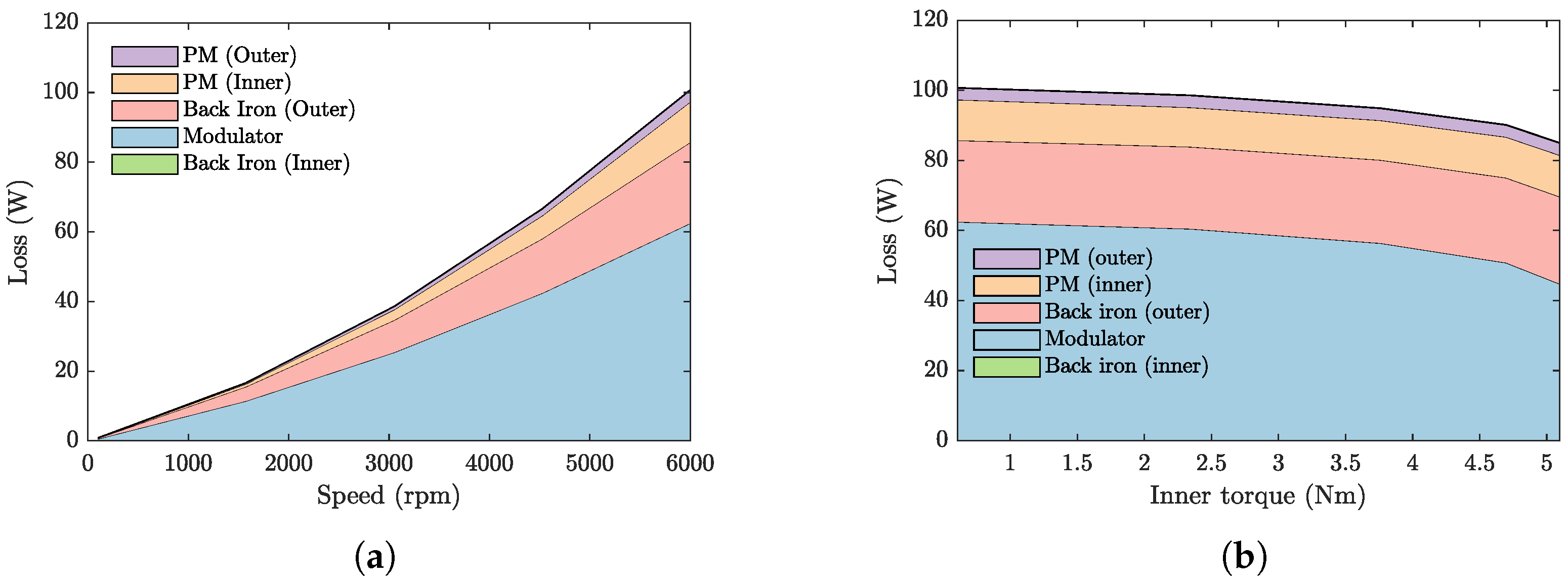

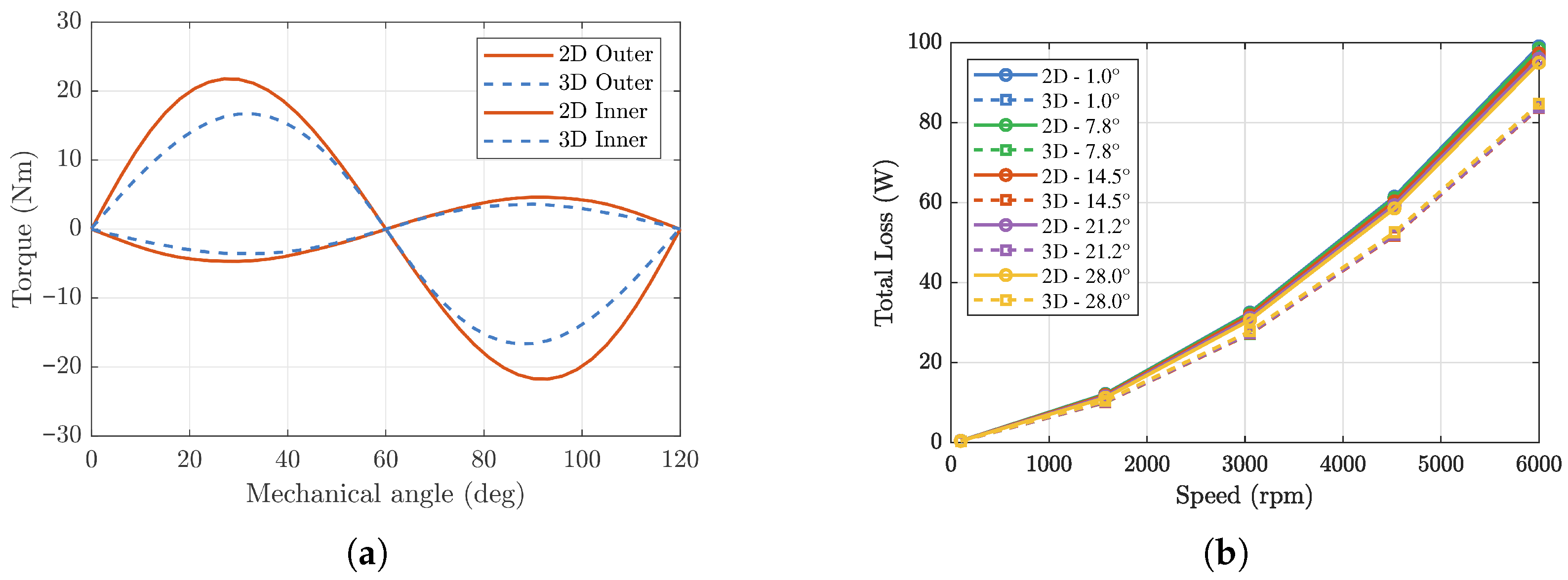

As illustrated in

Figure 4, component-wise electromagnetic loss distributions under two scenarios:

Figure 4a shows the variation of total and distributed losses with speed for a torque-angle of

(maximum torque), and

Figure 4b shows the variation of losses with transmitted inner torque at a constant inner rotor speed of 6000 r/min. Each color region denotes the contribution of the outer PMs, inner PMs, outer back iron, modulators, and inner back iron.The CMG total losses increase rapidly with the inner rotor speed and decrease smoothly with the inner rotor torque. The modulators and outer back iron emerge as the dominant contributors. This behavior is consistent with core loss physics: electromagnetic losses scale strongly with electrical frequency and with local flux density harmonics, so iron regions experiencing large alternating flux near the modulator tips and back iron dominate [

34]. Although the Halbach configuration reduces the radial leakage inside PMs, it does not eliminate the tangential harmonic components introduced by modulation. These alternating components penetrate the PMs and increase with rotational speed, meaning that PM eddy-current losses can become non-negligible under high-speed operation, even if they remain lower than the iron losses at moderate speeds. Since eddy-current losses scale approximately with the square of the electrical frequency, their increase at high speed is particularly pronounced. Consequently, to obtained improved performance in CMGs, the design should primarily focus on reducing the dominant iron losses through geometric optimization or the use of low-loss laminated materials, while also accounting for potential PM losses in high-speed applications.

The efficiency of the CMG is calculated by using the torque, iron losses and PM losses, following the expression adapted from [

35]. Other types of losses are neglected.

3.3. Hybrid Stochastic Optimization

In this section, we present a hybrid stochastic optimization method used to maximize the torque transmission capability of the CMG. Hybrid stochastic optimization may provide, in principle, a satisfactory compromise between computational effort and accuracy in estimating torque performance, making it suitable for magnetic gear design. To this end, a combination of 2D FEA, GA, and 3D parametric model is employed. In this hybrid strategy, the 2D FEA is fast and suitable for GA-based global space search, while 3D FEA is accurate and captures the essential end effects. This strategy is computationally efficient for exploration and physically reliable for final validation, ensuring both speed and accuracy in optimizing the CMG torque performance.

In this work, several pilot convergence tests were performed before the final optimization. The population size of 100, 35 generations, crossover probability of 0.7, and mutation probability of 0.1 were selected in magnetic gear optimization. Parameter ranges of this order have been reported in [

5,

8,

28] as providing a good balance between exploration and computational cost. Increasing the population to 150 or decreasing it to 50 did not improve the solution quality, while significantly affecting computation time. Similarly, crossover probabilities in the range 0.6–0.8 and mutation probabilities of 0.05–0.15 exhibited comparable convergence trends. The chosen configuration therefore represents a robust and computationally efficient setting rather than an attempt to fine-tune GA hyperparameters.

The proposed CMG with a hybrid Halbach array (only inner rotor) involves many coupled design variables. With the proposed topology fixed parameters in

Table 1, we employed a genetic algorithm in MATLAB coupled with a 2D finite-element model in Finite Element Method Magnetics (FEMM) to maximize the VTD [

36]. The search enforced the radial envelope constraint

initialized from the bounds

,

, and

.

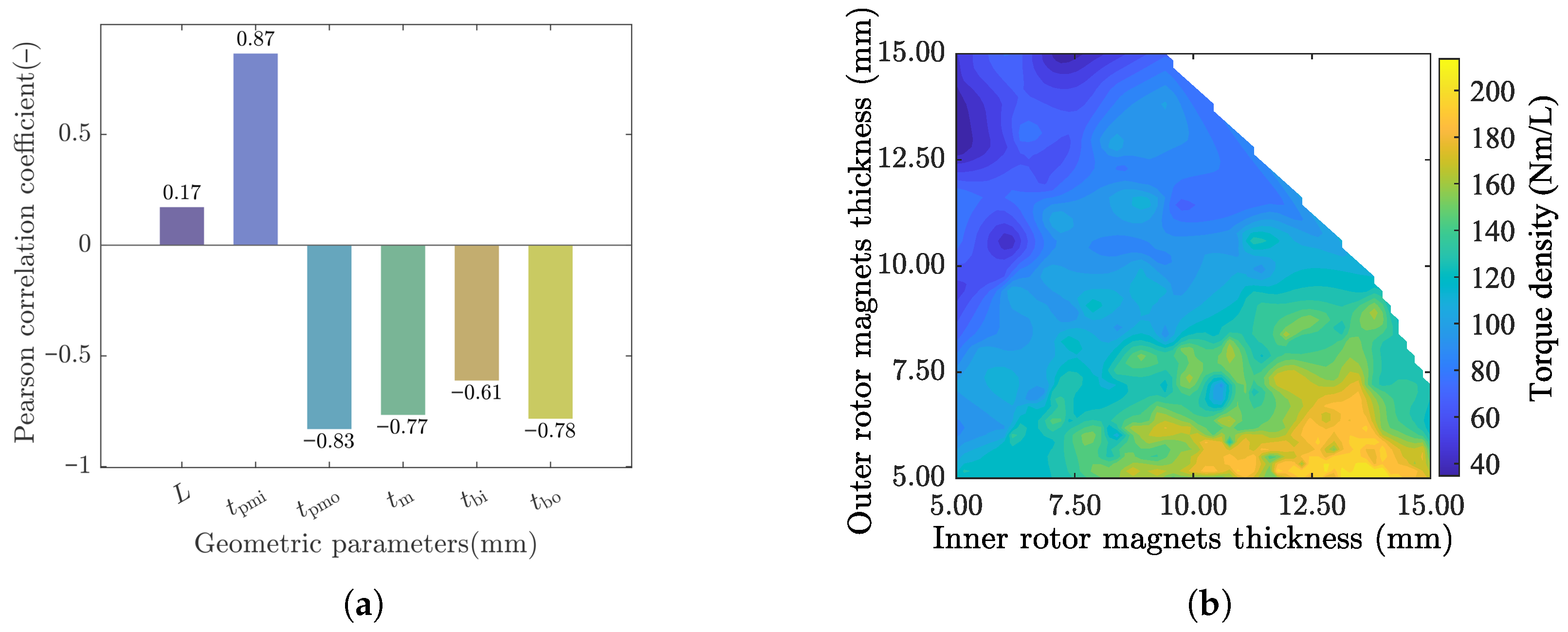

The full optimization population over the design space is shown in

Figure 5. It can be seen how the volumetric torque density varies with structural parameters, revealing strong positive correlations between VTD and the optimized parameters, especially for the inner magnet thickness.

For computational efficiency, a screening sensitivity analysis precedes the GA to fix low-influence variables. Subsequently, the GA queries the fast model for evolution while optimal designs are checked with 3D FEA to account for end effects. This analysis reveals how individual variables influence the CMG’s electromagnetic performance. Parameters with the largest impact are retained for optimization, while low-influence variables are fixed to nominal values, thereby shrinking the search space, shortening calculation time, and improving optimization efficiency.

To quantify the influence of each design variable on the objective, the Pearson correlation coefficient [

37] is employed. For a design variable,

, and the objective,

y, the Pearson coefficient is defined as

where

and

are the standard deviations of

and

y, respectively. A positive value indicates that increasing

tends to increase the objective, whereas a negative value indicates the opposite trend. To indicate direction (beneficial vs. detrimental performance), the sign of the bars in the plots is taken from the correlation while the bar height reflects the magnitude. Larger values denote stronger influence. In

Figure 6a, the inner PM thickness,

, is most beneficial (∼+0.87); the outer PM thickness,

, and the modulator thickness,

, are strongly detrimental (∼

and

); the back irons,

, are moderately detrimental (∼

); and the stack length,

L, is weakly positive (∼+0.17).

Figure 6b shows that the

contour reveals a high VTD ridge at larger

with smaller

, guiding the design toward higher

, lower

.

The refined search ranges and fixed inputs used for subsequent evaluation are summarized in

Table 2.

3.4. Validation Plan and Metrics

Three components of axial end effects, leakage, fringing, and escaping have been reported [

13], where leakage denotes flux bypassing the intended path, fringing refers to lateral flux spreading at magnetic discontinuities, and escaping describes flux leaving the active region without re-entering the air gap. The last one is particularly important for CMG because the torque transmission depends on precise harmonic modulation across the modulators.

Figure 7 shows the magnetic flux density distributions obtained from the 2D and 3D FEA models of the proposed magnetic gear.

Figure 7a shows the idealized steady-state flux pattern in 2D FEA, where end effects are neglected and the magnetic field is evenly distributed along the axial direction. In contrast, the 3D FEA results in the influence of axial flux leakage and non-uniform field distribution caused by the axial length. The half cross-section in

Figure 7b visualizes the internal magnetic flux distribution, while the front view in

Figure 7c confirms the periodic modulation of flux density. The cross section in

Figure 7d shows the axial variation of the magnetic flux density, demonstrating that non-uniform axial flux patterns are inherently in the 3D model. In contrast, the 2D FEA relies on the assumption of axial uniformity, which cannot capture these features. This discrepancy in modeling is also a primary contributor to the differences in evaluation results between 2D and 3D FEA.

To quantify the extent of the correlation between 2D and 3D FEA results, the results obtained from the 2D FEM model are used as a reference approximation, whereas the 3D FEM results are regarded as the more accurate prediction. The 3D-2D ratios of torque,

, and loss,

, between the 2D evaluation and the 3D are defined as [

9,

13]

where

and

represent the predicted steady state electromagnetic stall torque from 2D and 3D FEA, respectively. Similarly,

and

are the corresponding losses (including core loss and eddy current loss) averaged over one electrical period.

Most 2D–3D discrepancies originate from axial end effects and the associated axial flux leakage. The 2D–3D deviation is not a constant offset but varies across the design space. Although space-mapping or surrogate corrections are possible, the parameter dependence of end effects makes a single global correction unreliable without extensive 3D sampling.

4. Results and Discussion

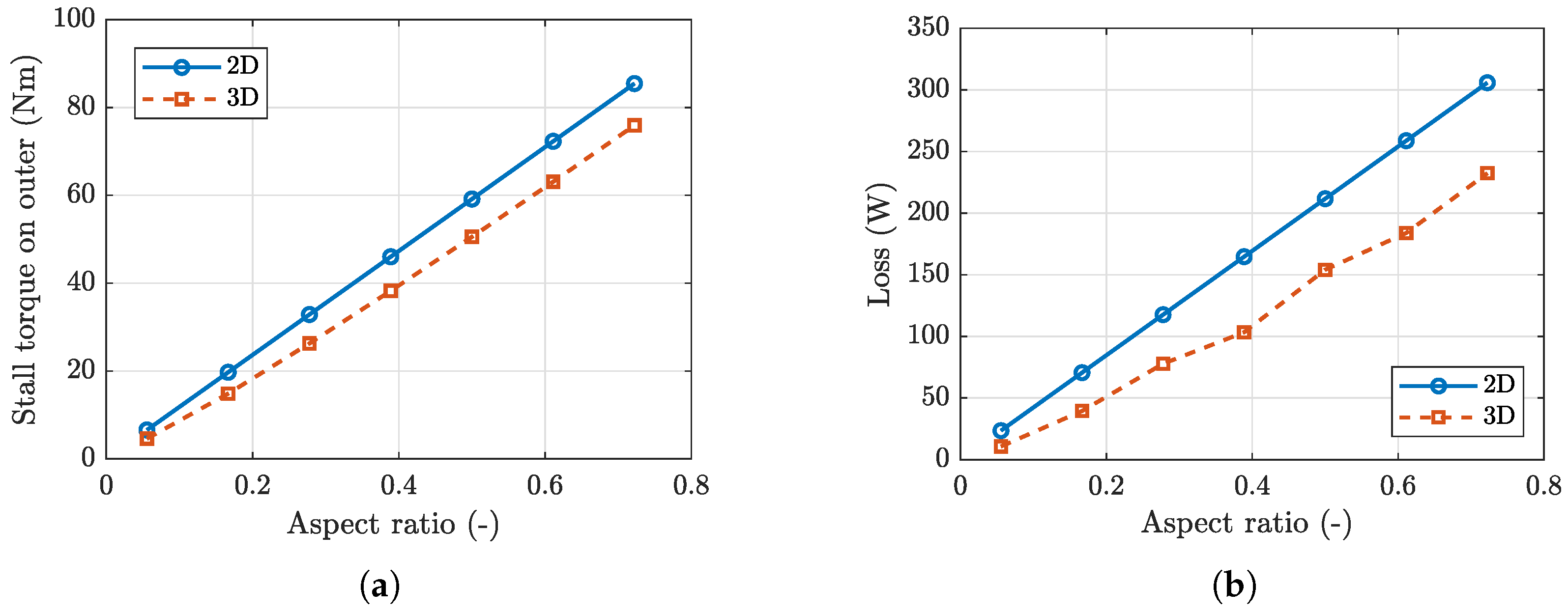

A first analysis was conducted to study the influence of several parameters on the stall torque and electromagnetic loss. For torque, we take the magnitude of the mean stall torque to avoid sign issues. The design was evaluated by 2D and 3D FEM with different CMG axial lengths. In the case of the axial length between

and

, which corresponds to an aspect ratio range between 0.056 to 0.722 (

). All simulations by 2D and 3D FEA have significantly different stall torque and loss versus aspect ratio curves, as shown in

Figure 8.

Both the stall torque and the electromagnetic loss increase with aspect ratio, and become slightly sub-linear for short stacks due to end-region leakage and fringing. The 3D predictions remain below the 2D results because only the 3D model captures these end-region and three-dimensional effects.

The effect of the inner magnet thickness on the stall torque and loss is illustrated in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. In the simulated model, the outer magnet thickness and modulator thickness were kept constant. It can be seen that the 2D and 3D results follow similar trends, 3D predictions remaining slightly lower, because only the 3D FEA captures end-region and 3D effects. The torque and loss normalized by magnet thickness decrease as the magnet thickness increases; however, this trend mainly reflects the normalization and the diminishing incremental benefit of adding more magnet volume, rather than a fundamental loading limit. This observation is consistent with the diminishing-return behavior discussed in [

13].

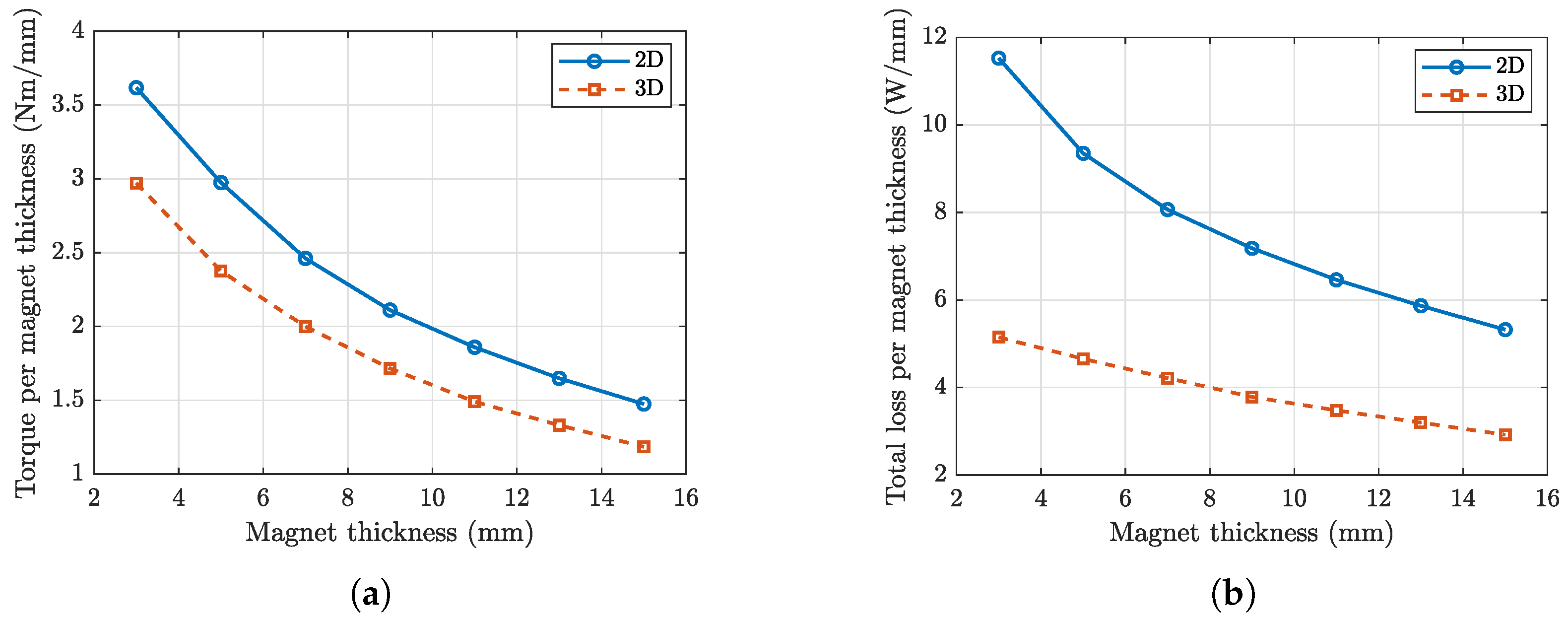

The impact of the axial length (stack length

L) on the CMG with a hybrid Halbach array is shown in

Figure 11a. An axial length

was selected from optimal resolutions, as this still guarantees a high VTD. The stall torque (maximum torque) increases with the stack length,

L. Correspondingly, the volumetric torque density shows a small but measurable rise, because the torque grows slightly faster than the active volume as the relative influence of 3D fringing and edge effects diminishes with increasing axial length. Across the range, the 3D FEA predictions are systematically lower than the 2D results because the 3D FEA captures effects that are absent in 2D, including axial end phenomena, three-dimensional fringing, edge saturation, and harmonic distortion, which have been reported in [

7,

25,

38]. As a result, 2D FEA tends to overestimate the torque capability, whereas 3D FEA provides a more realistic prediction at the cost of higher computational effort.

Wong et al. reported that reducing the axial length of the modulators,

, leads to an improvement in volumetric torque density, owing to increased flux concentration and altered harmonic coupling [

18]. Accordingly,

Figure 11b demonstrates the torque transmission at different lamination axial lengths,

, with the axial lengths of inner and outer rotors fixed at

. It can be seen that maximum torque and VTD occur when

. These yielded stall torque and VTD of 16.51 Nm and 161.88 Nm/L, with an improvement of 1.5 %. Thus, the value of

was decreased to 15.8 mm for the final design.

4.1. Torque Transmission

In a magnetic gear, the torque is transmitted between the rotors through the magnetic coupling established by the modulators. The electromagnetic torque on each rotor fluctuates periodically with time, producing torque ripple due to the spatial harmonics in the air-gap flux. Prior work has already demonstrated the need to assess torque ripple and electromagnetic force harmonics in flux-modulated converters from a structural standpoint [

25]. Additionally, higher losses can be attributed to increased bearing friction due to unbalanced forces [

39]. However, the converter studied in literature differs from the present topology and assumes conventionally manufactured modulators. Here, we quantify the torque ripple and the radial and tangential forces (X, Y force components) for our design. The torque ripple coefficient

quantifies the relative torque variation over one steady-state period and is defined as

where

,

, and

are the maximum, minimum, and average electromagnetic torque, respectively.

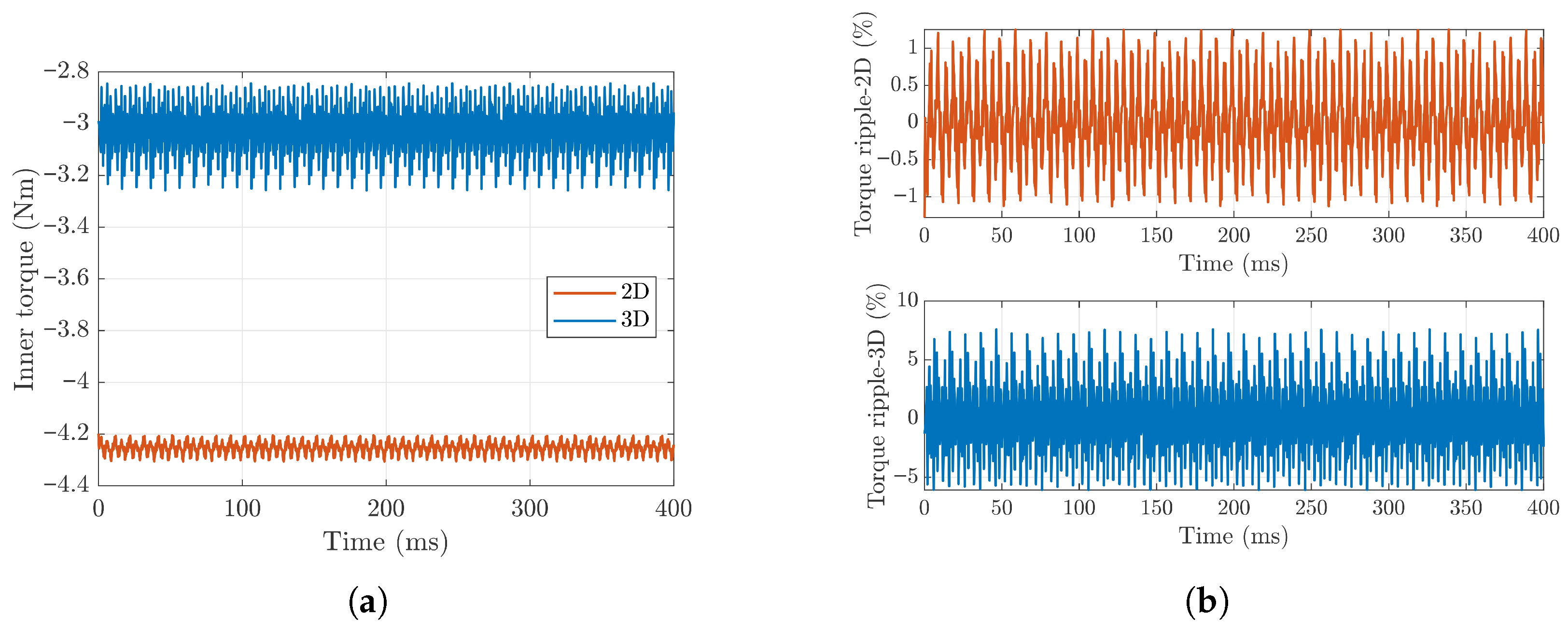

The instantaneous torque responses of the inner and outer rotors (load angle of

, inner rotor speed of 6000 r/min) are illustrated in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. The transient simulation was carried out over a total duration of 400 ms with 2000 uniformly spaced sampling points, corresponding to a time step of

. It can be observed that the 3D FEA predicts a noticeably higher torque ripple compared with the 2D FEA. Specifically, the torque ripple coefficient of the inner rotor increases from 1.27% (2D FEA) to 6.83% (3D FEA), while the torque ripple of the outer rotor rises from 0.84% (2D FEA) to 1.67% (3D FEA). The higher torque ripple predicted in 3D arises from end effects, leakage flux, and additional 3D harmonic components, which are not captured in the 2D formulation. These axial variations in the air gaps increase the periodic torque fluctuation on the inner rotor.

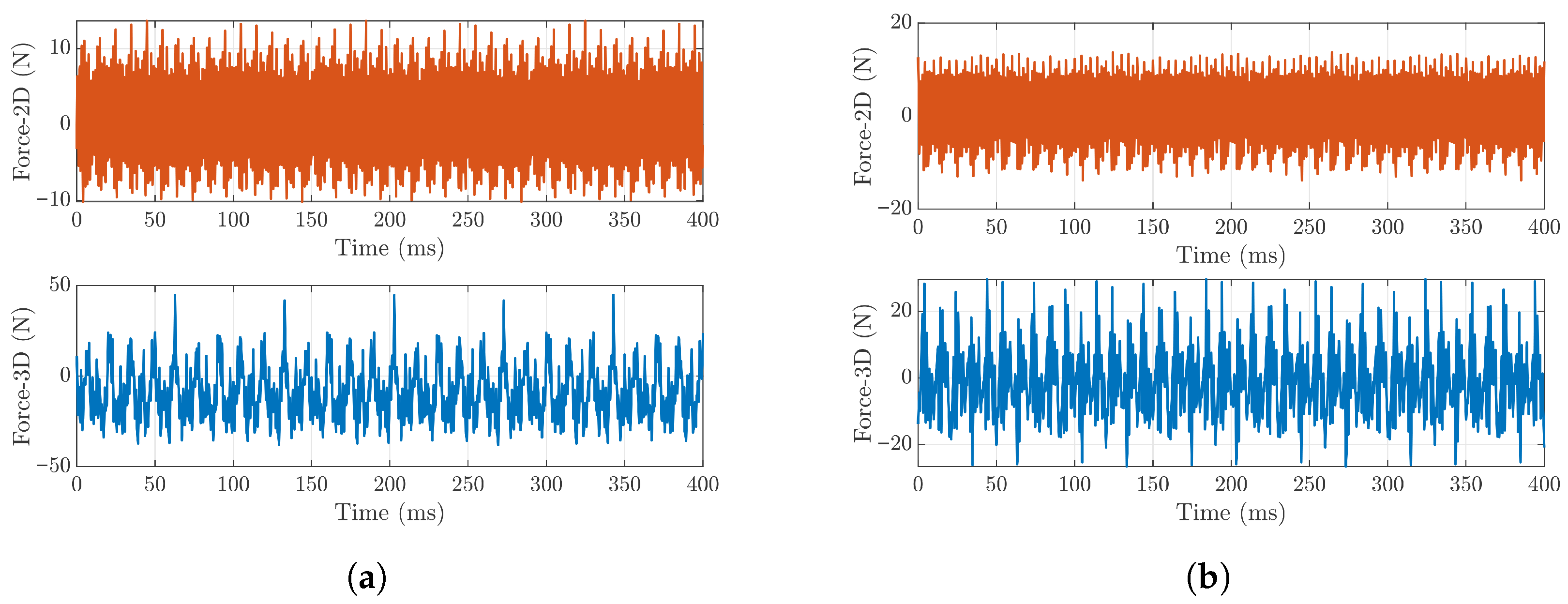

4.2. Unbalance Force

In this subsection, the unbalance forces acting on the modulators (stator) are investigated. These forces can contribute to vibration, acoustic noise, and mechanical stress in practical applications [

40], making them important design considerations. Both radial force, X component (

), and tangential force, Y component (

), exhibit significantly different characteristics, as illustrated in

Figure 14. The force in 3D shows larger fluctuation amplitudes and richer harmonic content, mainly due to the axial flux components and the end effect. In contrast, the smoother force in 2D tends to underestimate the magnitude of the force. These discrepancies are consistent with the torque ripple behavior observed earlier [

25], indicating that the simplified 2D approximation neglects key spatial variations of the magnetic field.

The relationship between unbalance electromagnetic forces and torque ripple is not universal, it depends on the CMG topology, the number of modulators, and harmonic interactions as reported in [

22]. As reported in [

38], an odd number of modulators inherently introduces radial unbalance force. However, our design still exhibits low torque ripple. This is mainly because the Halbach magnetization and the pole pair mismatch reduce the amplitude of the dominant torque ripple harmonics. Overall, the comparison results indicate that while 2D FEA provides a reasonable estimation of average torque, it underpredicts torque ripple and force harmonics. Therefore, 3D simulations are fundamental for accurate assessment of dynamic performance and mechanical reliability.

4.3. Efficiency Estimation

Magnetic gear losses are dominated by operating speed and vary only mildly with load torque, as shown in

Figure 15a, consistent with prior observations [

31]. A comparison of 2D and 3D FEA as

Table 3 shows that the 2D model overestimates VTD by about 24% relative to the 3D model, which lies within the 20–40% overestimation range reported in the literature [

39,

41]. While absolute magnitudes differ, the operating point trends predicted by 2D and 3D are consistent (i.e., similar variation across speed and load angle), with small point-wise deviations when trends are compared. The operating points selected in this study are representative of typical CMG usage; however, they do not exhaustively cover all possible load angles or speed conditions.

Figure 15b depicts total loss versus speed for multiple initial inner rotor angles (which correspond to different torque loading conditions). Both 2D and 3D results exhibit a comparable monotonic increase in loss with speed. However, their absolute values differ. Notably, the 3D FEA predicts lower total loss than the 2D FEA, and the relative discrepancy in loss is larger than that for torque. This is because at the operating conditions, the axial flux spreading and the relatively large electromagnetic skin depth reduce the effective radial flux gradients within the PMs and back iron. In the 3D FEA, these axial leakage paths naturally soften the local

distribution that drives eddy current formation. Conversely, the 2D FEA constrains the field to remain strictly uniform along the axial direction and forces all eddy current loops to close within the

r-

plane, thereby artificially strengthening the induced currents. As a result, the 2D FEA tends to overestimate both PMs and iron eddy losses, whereas the 3D FEA captures the attenuation of end region fields and the reduced eddy current circulation.

Such behavior has also been reported in several low-frequency, low aspect ratio PM devices [

9,

32,

42,

43,

44,

45], where 3D simulations exhibit lower losses than 2D due to weakened axial current paths and reduced flux concentration near magnet edges. This confirms that, in the frequency range and geometric regime relevant to this study, loss end effects are more dominant than torque end effects, leading to a larger 2D and 3D discrepancy in loss predictions.

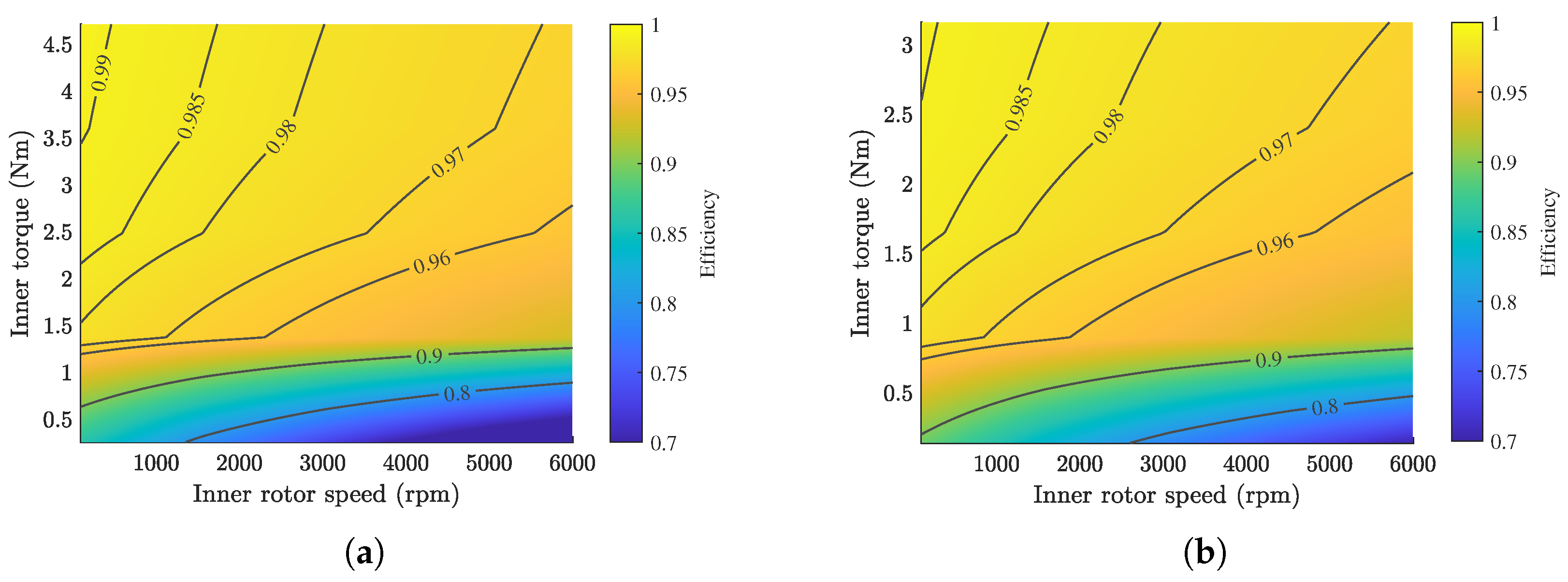

The efficiency maps in

Figure 16 (with inner rotor speed from 100 r/min to 6000 r/min) further confirm a common trend in both models: efficiency increases with load torque, and losses scale primarily with speed, in agreement with [

20,

46].

Although an experimental prototype is not included in the present study, the accuracy of 3D FEA for coaxial magnetic gears has been widely reported in the literature. Experimental validations in [

18,

20,

26] show that 3D simulations typically predict the transmitted torque within 8–15% of measurements, while 2D FEA tends to overestimate torque by 20–40% [

39,

41] due to the absence of axial end effects. Similarly, iron loss (core loss) and PM eddy current loss predictions generally exhibit 10–20% [

31,

33,

47] deviation from experimental results, depending on lamination anisotropy and material properties. The 24% torque difference between the 2D and 3D predictions observed in this work therefore lies well within the range reported in prior CMG validation studies, indicating that the adopted 3D model exhibits representative physical accuracy.

After 3D verification (and minor rounding to catalog available dimensions), we selected the geometry that maximizes VTD while meeting loss and efficiency targets. The final design parameters of the proposed CMG are summarized in

Table 4.

4.4. Computation Time Comparison

To quantify the computational benefit of the proposed hybrid strategy, the evaluation times of the 2D and 3D FEA were benchmarked on a workstation equipped with an Intel® CoreTM i9-185H processor (2.30 GHz, 14 cores) and 64 GB RAM.

A single 2D FEA torque–angle evaluation requires only 0.8–1.5 s, enabling rapid population-based optimization. In contrast, a transient 3D FEA simulation requires 35–55 min per design point. This corresponds to a slowdown of approximately 1200–2000× relative to 2D analysis. Comparable 2D–3D computation costs have been reported in the literature [

35,

48].

During optimization, the GA evaluates roughly 2500–3000 candidates. A 3D FEA search would therefore require several weeks of computation, whereas the proposed hybrid workflow completes the 2D optimization stage within 3–4 h and the 3D refinement within 10–15 h. Thus, the full optimization and validation process is completed within four working days. The computation time is summarized in

Table 5.