Design and Anti-Impact Performance Study of a Parallel Vector Thruster

Abstract

1. Introduction

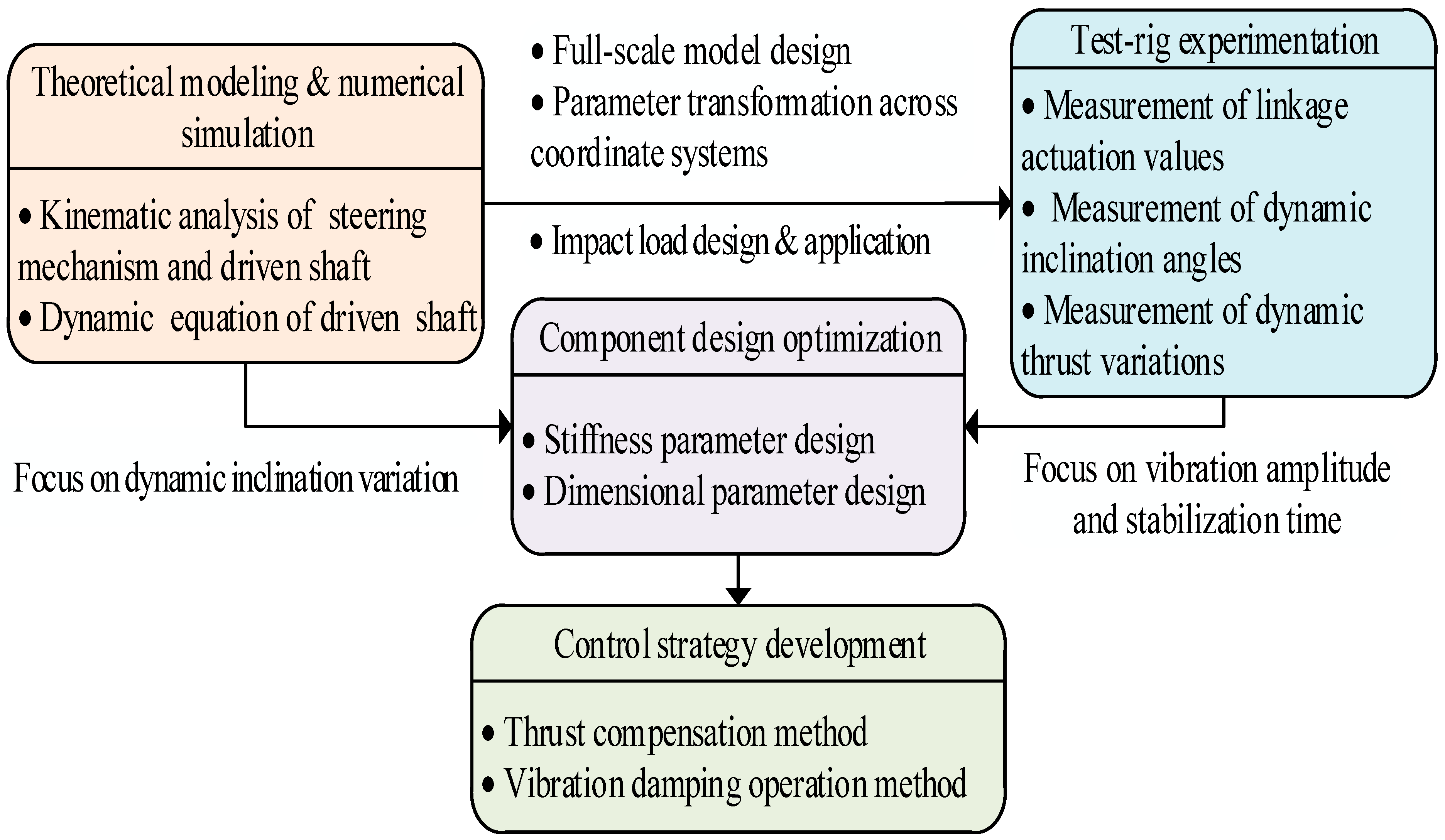

2. Kinematic and Dynamic Analysis of Vector Thruster Components

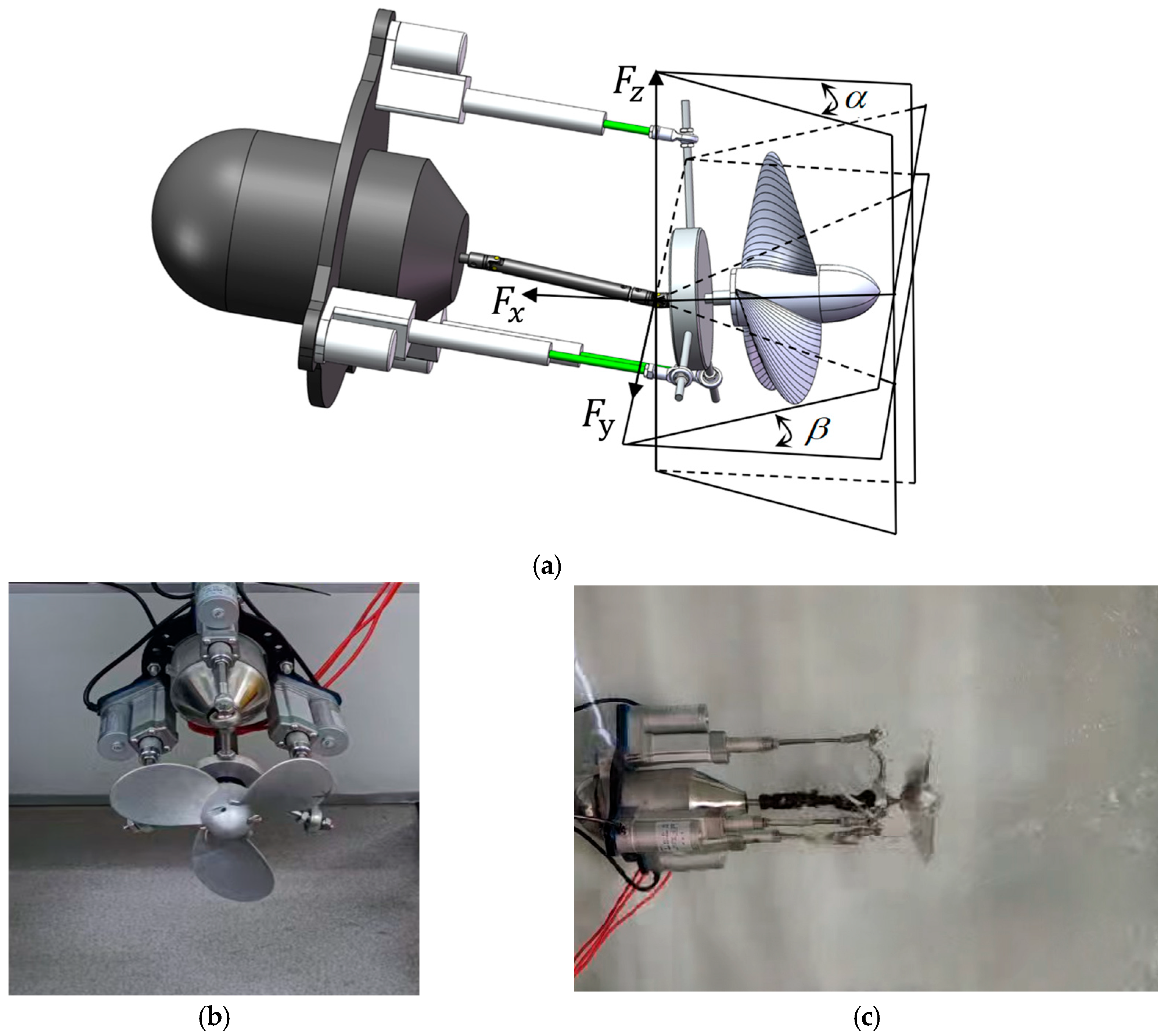

2.1. The Design Philosophy and Implementation

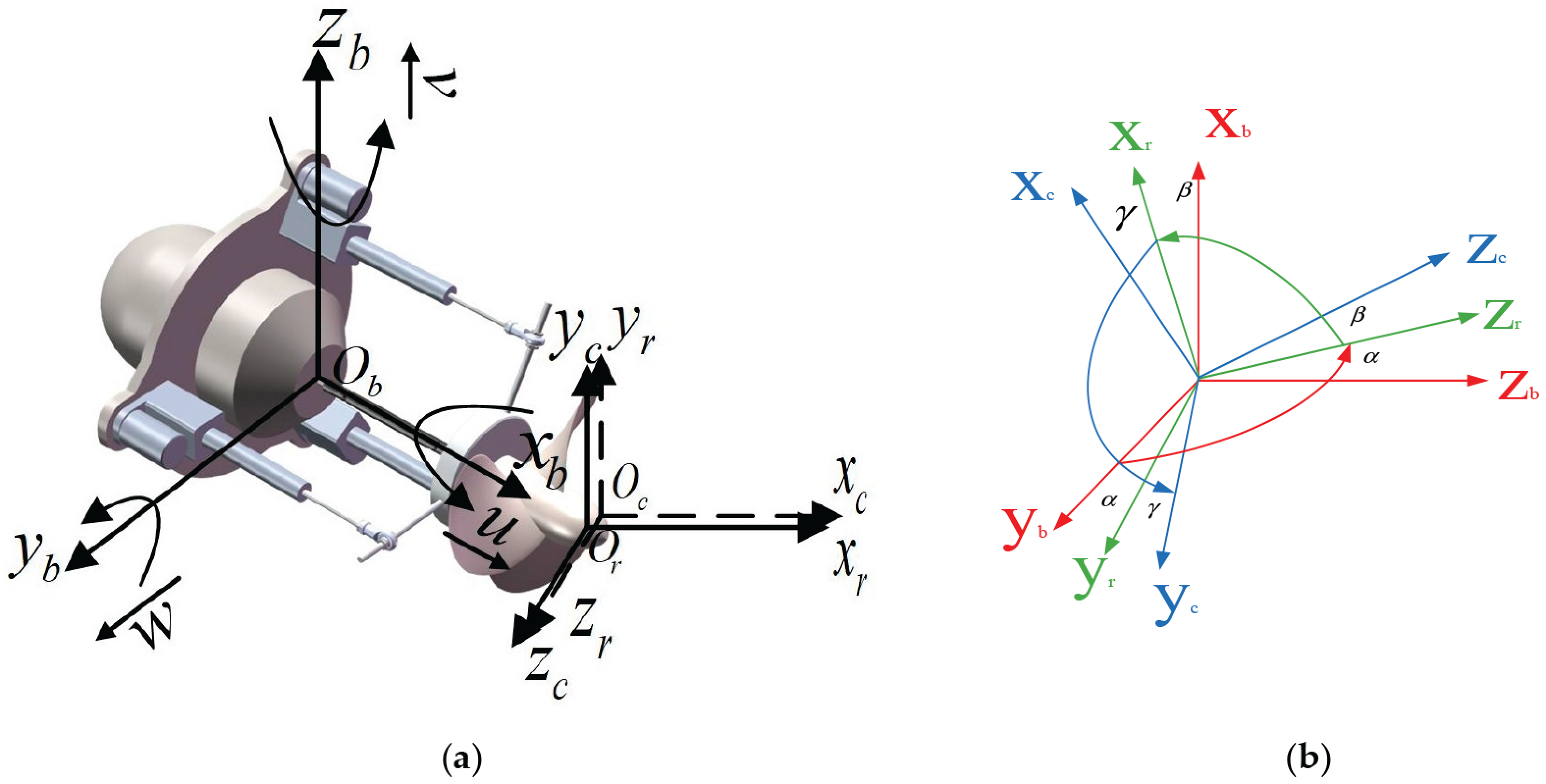

2.2. The Construction of Dynamic Equations

- (1)

- Base coordinate system fixed on AUV , denoted by ;

- (2)

- Rotation coordinate system on the geometry center of the propeller as the original point, denoted by ;

- (3)

- Rotation coordinate system on the mass center of the propeller as the original point. , denoted by .

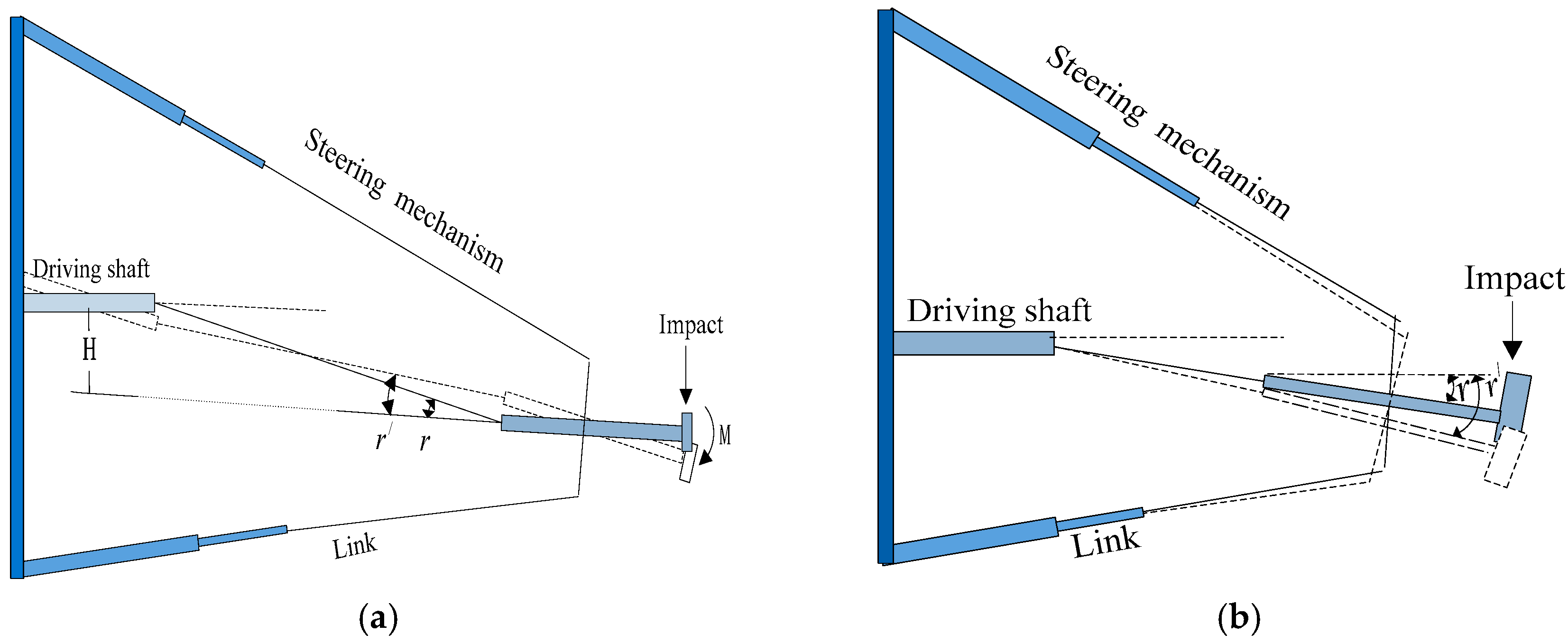

2.3. Dynamic Response of the Steering Mechanism Under Impact Load

2.4. Dynamic Response of Driven Shaft Under Impact Load

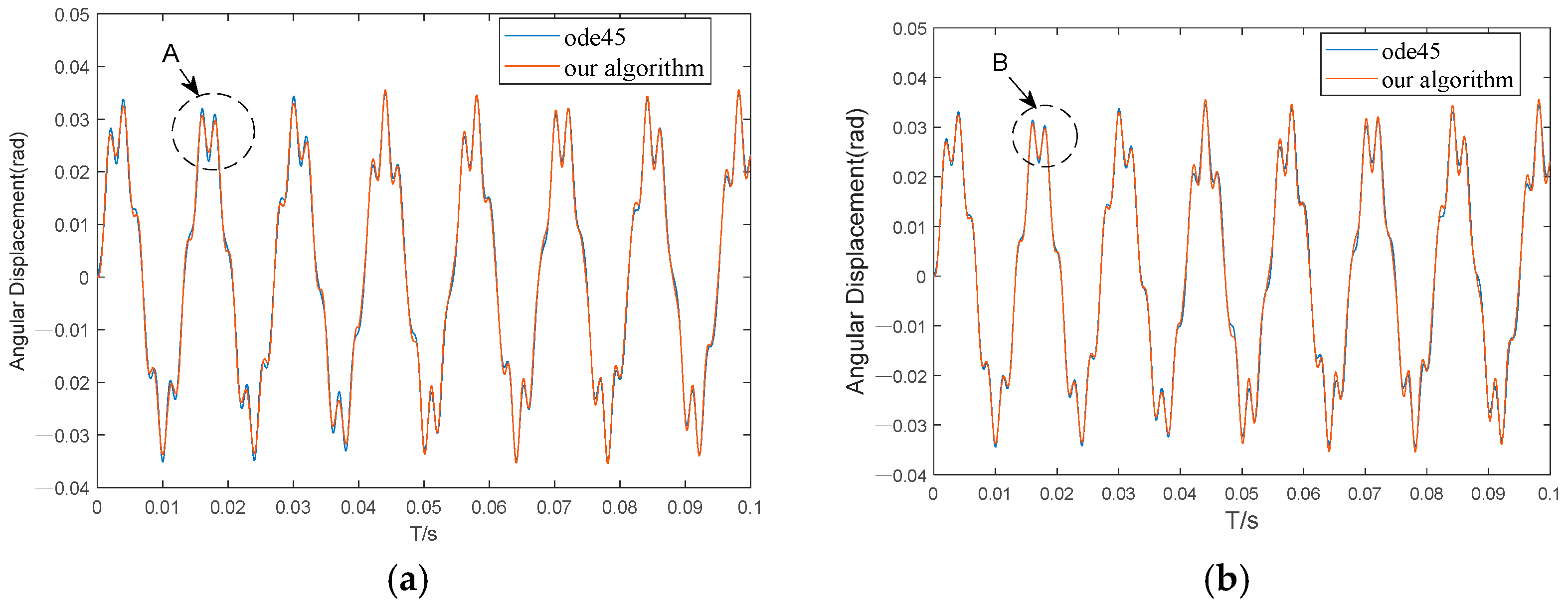

3. Vibration Characteristic Analysis Based on Numerical Simulation

3.1. Numerical Simulation Method

- (1)

- Assign each parameter of the shafting: set the initial inclination angle , set the initial geometric position of the drive shaft and steering mechanism. Set the time t = 0; and set the angular acceleration and angular displacement of the driving shaft, the driven shaft, and the intermediate shaft to all 0.

- (2)

- Impact load parameters were determined through a combined approach of theoretical calculation and experimental adjustment. Initial baseline load values were obtained by calculating the torque of a four-blade propeller according to DNV standards. Given the system’s high sensitivity to impact loads, iterative experimental adjustments were subsequently performed on the load amplitude, duration, and application point to achieve optimal system response. The parameters ultimately set in this study were an impact force of 0.1 kN and a pulse width of 10 ms. Besides, we applied the impact load at t = 1 s to ensure that the load was imposed on a fully stabilized system, thereby facilitating a consistent and meaningful comparison of the resulting parameters.

- (3)

- Based on the applied impact loads, a dynamic response analysis was conducted separately for the steering mechanism and the drive shaft. This analysis yielded key parameters including the length of the tie rod, the spatial position of the propeller, and the resulting bending moment.

- (4)

- The dynamic inclination angle is chosen as the analysis parameter and is designated as . At each time step (), the time-varying spatial position of the propeller is calculated and substituted into Equation (8). With the inclination angle updated (→ ), the system’s vibration equations at these two angular positions are expressed as follows:

- (5)

- Suppose the acceleration varies linearly within the time step . Using γ and β as the parameters governing the accuracy and stability of the Newmark algorithm, the update Equations for the state variables can be derived as follows:

- (6)

- Steps 3–5 are repeated iteratively over each interval until the phase trajectory converges. The resulting state parameters are subsequently used to calculate other vibration characteristics.

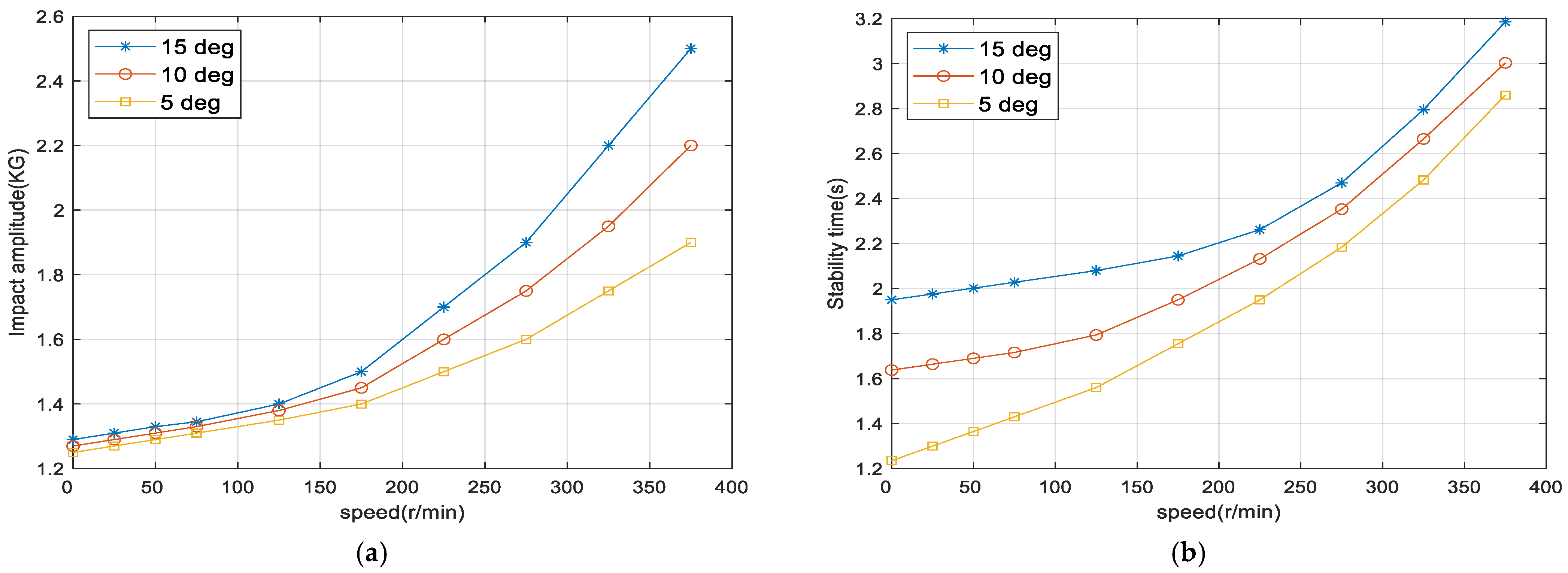

3.2. Vibration Characteristics Under Different Structural Parameters

3.3. Vibration Characteristics Under Different Operating Conditions

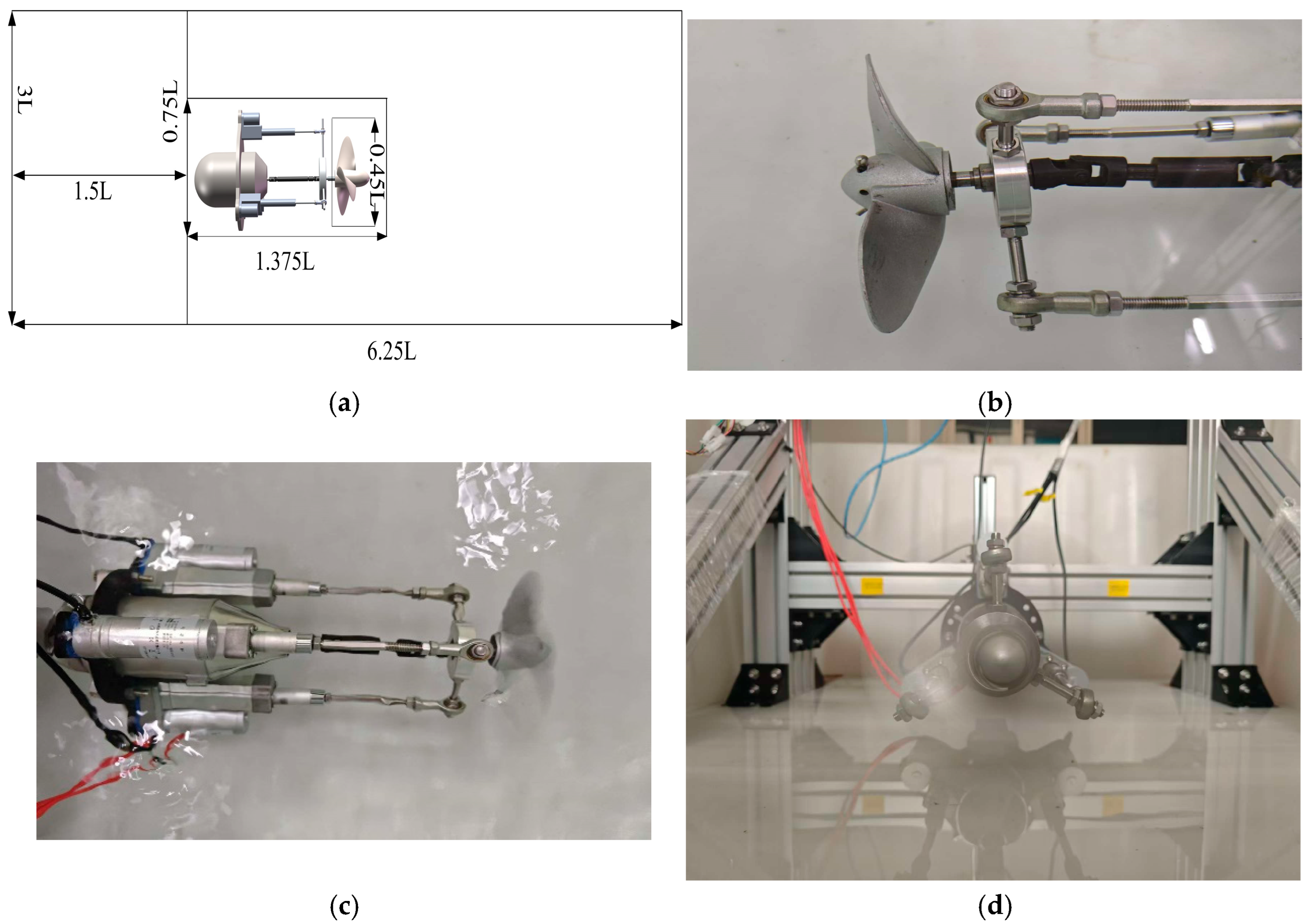

4. Dynamic Inclination Angle and Thrust Analysis Based on a Test Rig

- The three-axis force sensor (Model: DET G10) has 3 channels, with an accuracy error of ±0.1% ± 30 g, a tension resolution of 0.001 kg, and an internal data update frequency of up to 100 Hz, enabling it to meet the testing standards for underwater vector thrusters.

- The vibration sensor (Model: 5E106) has a range of 10 mm, a sensitivity of 1 V/mm, and a frequency response of 0–10,000 Hz. The sensors were installed on the base, thrust sensor mount, and vectoring mechanism, with specific installation details shown in Figure 10b, Figure 10c, and Figure 10d, respectively.

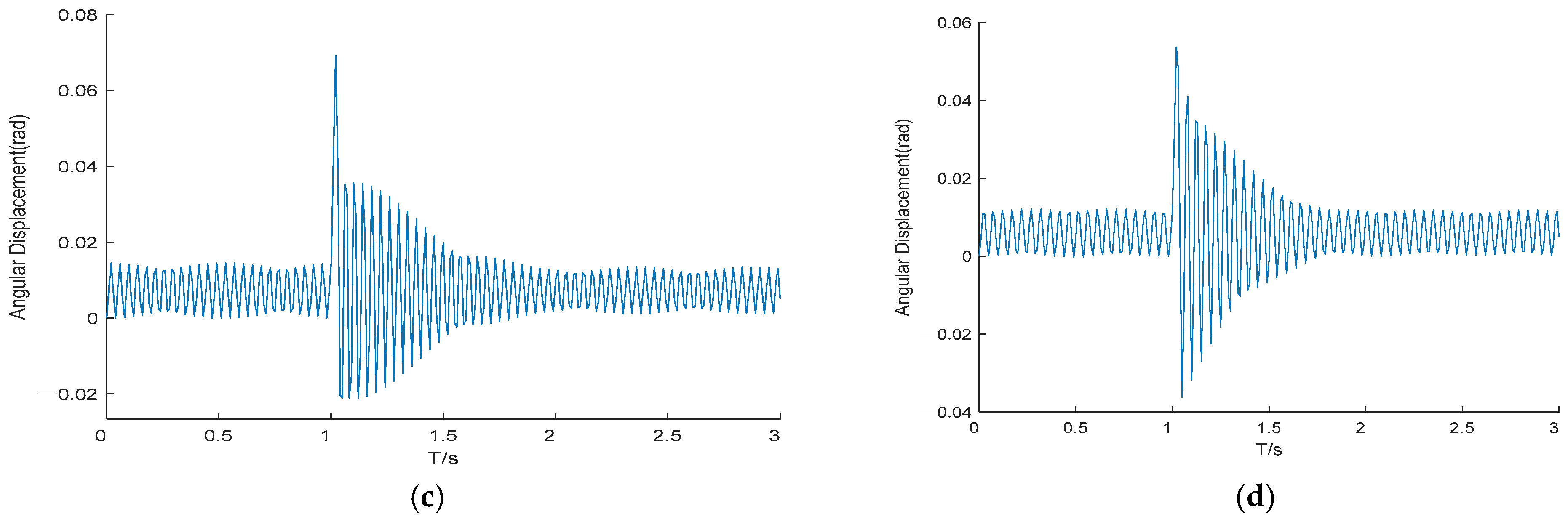

- The test tank had a diameter of 3L and contained a flow path in which the propeller length was defined as the reference length L; the front section (inlet to thruster) measured 1.5 L and the rear section (thruster to outlet) measured 3.375 L, as illustrated in Figure 11a.

- Figure 12b–d depict three key operational states of the system: (b) the initial standby state before startup; (c) stable underwater operation (side view); and (d) surface-level operation (front view). During the experiments, the load application system integrated into the test bench was capable of applying various types of loads while simultaneously acquiring data, thereby facilitating comprehensive dynamic performance analysis.

- Signal filtering is employed to manage noise, with the test rig capable of capturing vibrations below 10 kHz. An adjustable software filter is provided to smooth the raw data accordingly.

- Measurement synchronization is achieved through a hardware-triggered procedure, which simultaneously activates all data acquisition channels with a temporal accuracy better than 0.1 ms, thereby minimizing errors caused by timing misalignment.

- Sensor Calibration Adjusted for Environmental Variability: Laboratory tests with vibration isolation remain susceptible to measurement fluctuations in inclination angle due to confined-flow effects such as recirculation and turbulence. Conversely, outdoor experiments—while providing an open flow field—introduce variability from wind, waves, and fixture stability. Therefore, the built-in parameter calibration function must be employed to compensate for these environmental shifts and for drift due to prolonged operation.

5. Discussion

- When impact loads act on the universal-joint vector thruster, they induce distinct dynamic responses in both the driven shaft and the steering mechanism. The dynamic response is highly dependent on factors such as the position, stiffness, and inclination angle of the steering mechanism within the thruster. These two types of responses interact with each other, forming a positive feedback loop that complicates the vibration behavior and ultimately degrades the system’s dynamic performance.

- Due to the strong nonlinear coupling between the universal joint and the steering mechanism under different operating conditions as well as structural parameters, the calculation of the impact load response in the time domain becomes highly complex. However, iterative simulation calculations based on the Newmark method can be effectively applied to the impact load response analysis of the vector thruster. However, as both the numerical simulations and the experimental setup involve significant simplifications, future work should prioritize more sophisticated hydrodynamic calculations, focusing particularly on developing higher-fidelity models through transient fluid–structure interaction analysis to enhance computational precision.

- Both the fluctuation amplitude of the inclination angle and the vibration stabilization time increase with the stiffness ratio, but the increase in stabilization time is more pronounced. During the operation of the vector thruster, both the vibration amplitude and the stabilization time increase with larger inclination angles. However, systems with higher length ratios exhibit a more pronounced growth in amplitude as the inclination angle increases. These fluctuations in inclination angle directly affect the thrust characteristics of the thruster. Therefore, in the design of vector thrusters, stiffness and dimensional parameters must be reasonably selected to enhance anti-impact performance.

- Given the presence of thrust loss and the significant influence of structural parameters on impact response, it remains essential to determine the operational load range through parameter analysis and to promptly increase rotational speed upon impact for compensation. Looking ahead, future implementations should integrate flexible couplings to absorb transient vibrations, incorporate damping materials to dissipate impact energy, and develop active control schemes for real-time compensation. This integrated approach would substantially improve the operational reliability of propulsion systems under dynamic loading conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, J.M.; Zou, X.Y.; Zheng, Z.H. Research on the wake field characteristics and maneuverability of vector pump-jet propulsion. Ship Sci. Technol. 2023, 45, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kadiyam, J.; Mohan, S.; Deshmukh, D.; Seo, T. Simulation-based semi-empirical comparative study of fixed and vectored thruster configurations for an underwater vehicle. Ocean Eng. 2021, 234, 109231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.; Halder, A.; Benedict, M.; Young, Y.L. A control scheme for 360° thrust vectoring of cycloidal propellers with forward speed. Ocean Eng. 2022, 249, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.X.; Li, J.B. Investigating the vibration characteristics of vector thrusters under complex inclination angle variations. Ships Offshore Struct. 2024, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.S.; Ding, H.; Feng, T.C. An approximation method for calculating characteristics of propeller in waves. J. Ship Mech. 1999, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X. Research on Hydrodynamic Performance of Propeller in Heaving Condition. Master’s Thesis, College of Shipbuilding Engineering, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.M.; Wu, C.S. Effect of heaving on propeller performance in open water. Chin. J. Hydrodyn. 2015, 30, 284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.Y.; Huang, S. Study of the rudder with additional thrust fins used by non-linear vortex lattice method. J. Hua Zhong Univ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 34, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Politis, G.K. Application of a BEM time stepping algorithm in understanding complex unsteady propulsion hydrodynamic phenomena. Ocean Eng. 2011, 38, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.H.; Yan, X.P.; Liu, Z.L. Research on impact response relationship between the rotating speed and lateral vibration. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. (Transp. Sci. Eng.) 2008, 32, 997. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.G.; Zhou, R.P. Studies of the nonlinear shock response of propulsive shafting of vessels. J. Vib. Eng. 2005, 17, 854–856. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan, K.; Barik, C.R.; Sha, O.P. Shock transmission through universal joint of cutter suction dredger. Ocean Eng. 2021, 233, 109231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Pang, F.Z.; Wang, X.R. Coupled vibration mechanism of equipment and ship hull structure. J. Ship Mech. 2013, 17, 680–688. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Du, J.Y. Shock response analysis on ship power shaft system. J. Vib. Shock 2011, 30, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu, F.I.; Petrescu, R.V. The structure, geometry, and kinematics of a universal joint. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2019, 10, 1713–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dong, L.X.; Gan, X.H. Kinematic characteristics analysis of an unmanned boat shafting based on universal joint. Ship Sci. Technol. 2023, 45, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, R.P.; Wang, M.S. Simulation of Nonlinear Torsional Vibration of Universal Joint Based on MATLAB. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2011, 33, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Grządziela, A.; Kluczyk, M.; Piskur, P.; Naus, K. Shock impact simulation model along with the harmonic effect of the working device. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchemin, M.; Berlioz, A.; Ferraris, G. Dynamic behavior and stability of a rotor under base excitation. J. Vib. Acoust. 2006, 128, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperakis, A.S. An Integrated Approach to Naval Ship Survivability in Preliminary Ship Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University College London, London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- An, K.; Wang, W.D. Transmission performance and fault analysis of a vehicle universal joint. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaee-Nasab, F.S.; Moosavian, S.A.A. Self-tuning tracking control of AUVs for inspection task with ocean turbulences and uncertainties. Ocean Eng. 2024, 295, 116843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.S. CFD-based hydrodynamic performance investigation of autonomous underwater vehicles: A survey. Ocean Eng. 2024, 305, 117911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.X.; Li, J.B. Coupled vibration characteristics of marine shafting with complex change of inclination under ice loads. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2023, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Islam, M.; Veitch, B. Unsteady hydromechanics of a steering podded propeller unit. Ocean Eng. 2009, 36, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotomalala, Q.; Khoun, L.; Leblond, C. An advanced semi-analytical model for the study of naval shock problems. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 511, 116317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Parameter | Model | Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Name | P4119 | Maximum Blade Sectional Area (m2) | 0.086 |

| Diameter (m) | 0.305 | Blade Section Shape | NACA66-mod |

| Blade Number | 3 | Propeller Hub Length (m) | 0.156 |

| Hub Diameter Ratio | 0.2 | Blade Area Ratio (BAR) | 0.6 |

| Vertical Inclination | [−0.436, 0.436] | Horizontal Inclination | [−0.436, 0.436] |

| Speed (r/min) | Structural Parameters | Amplitude of Fluctuation | Settling Time (s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q1 (cm) | q2 (cm) | q3 (cm) | r (deg) | K | Inclination Angle (rad) | Thrust (KG) | ||

| 100 | 22.1 | 22.1 | 30.3 | 5 | 1.0 | 0.031 | 1.34 | 1.5 |

| 22.1 | 30.3 | 22.1 | 5 | 1.2 | 0.036 | 1.40 | 1.7 | |

| 200 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 32.5 | 10 | 1.0 | 0.043 | 1.71 | 2.0 |

| 14.7 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 20 | 1.2 | 0.047 | 1.94 | 2.2 | |

| 300 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 32.5 | 10 | 1.0 | 0.055 | 2.48 | 2.6 |

| 14.7 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 20 | 1.2 | 0.058 | 2.51 | 2.7 | |

| 400 | 36.0 | 14.7 | 36.0 | 20 | 1.0 | 0.069 | 3.59 | 3.5 |

| 14.7 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 20 | 1.2 | 0.072 | 3.65 | 3.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, L.; Li, J. Design and Anti-Impact Performance Study of a Parallel Vector Thruster. Machines 2025, 13, 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121149

Dong L, Li J. Design and Anti-Impact Performance Study of a Parallel Vector Thruster. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121149

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Liangxiong, and Jubao Li. 2025. "Design and Anti-Impact Performance Study of a Parallel Vector Thruster" Machines 13, no. 12: 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121149

APA StyleDong, L., & Li, J. (2025). Design and Anti-Impact Performance Study of a Parallel Vector Thruster. Machines, 13(12), 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121149