Multi-Stage Domain-Adapted 6D Pose Estimation of Warehouse Load Carriers: A Deep Convolutional Neural Network Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Problem Statement

2.1. The Use of Synthetic Data for Training Convolutional Neural Networks

2.2. Domain Adaptation Networks

2.3. Deep Learning Approaches for 6D Pose Estimation

2.4. Problem Statement and Contribution

3. Warehouse Pose Estimation Datasets

3.1. Real Single-Pallet Pose Dataset (RPP)

3.2. Warehouse Synthetic Single-Pallet Pose Dataset (WSPP)

3.3. Randomized Synthetic Single-Pallet Pose Dataset (RSPP)

4. Methodology

4.1. CUT Network

4.2. Pose Estimation Network

4.2.1. Baseline: Single-Stage Pose Estimation and Refinement Pipeline

- (a)

- Single-Stage Scenario-1: Basic RefinerThe first trained model is a basic refiner that is trained on 50k images from RSPP.

- (b)

- Single-Stage Scenario-2: WSPP RefinerRetraining the basic refiner using 50k additional images is expected to enhance its performance even if the data was not adapted. To ensure that the adaptation enhances the performance more than just retraining using additional non-adapted synthetic data, WSPP data is used to re-train the CosyPose refiner along with the original 50k images from RSPP. This refiner, which is trained on non-adapted WSPP data, is named the WSPP refiner.

- (c)

- Single-Stage Scenario-3: Adapted RefinerThe CosyPose model is trained again using the 50k adapted-WSPP images (Section 4.1) in addition to the 50k images from RSPP. This model aims at showcasing the ability of the domain adaptation approach in enhancing its performance when no real labeled data is available for training. This refiner is referred to in the paper as the adapted refiner.

4.2.2. The Proposed Multi-Stage Pose Estimation and Refinement Pipeline

- (a)

- Multi-stage Refinement Scenario-1: Basic + FinerThe first multi-stage model is constructed by adding the finer refiner after the basic refiner, as shown in Figure 12a. The initial pose estimate is refined first by the basic refiner for 2 iterations, as this provides an excellent trade-off between performance and inference speed. Afterwards, the pose is refined again for 4 iterations by the finer refiner. The intuition is that the finer refiner should be able to refine the small pose errors that the basic refiner was unable to enhance.

- (b)

- Multi-stage Refinement Scenario-2: Adapted + FinerThis modeling scenario uses the adapted refiner developed in Section 4.2.1 followed by a finer refiner, as shown in Figure 12b, to enhance the overall performance of the multi-stage pose refinement pipeline. Similarly to the first multi-stage scenario, the pose estimate is refined for two iterations using the adapted refiner, and then refined again for four iterations by the finer refiner.

4.3. Performance Analysis on the Real Test Dataset (RPP)

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Performance of the Single-Stage Refinement Pipeline

5.2. Performance of the Multi-Stage Refinement Pipeline

5.3. In-Depth Analysis of the Proposed Multi-Stage Domain-Adapted 6D Pose Estimation Approach

5.4. Computation Time and Efficiency

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fragapane, G.; Ivanov, D.; Peron, M.; Sgarbossa, F.; Strandhagen, J.O. Increasing flexibility and productivity in Industry 4.0 production networks with autonomous mobile robots and smart intralogistics. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 308, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtsis, D.; Tsolakis, N. Trends in Industrial Informatics and Supply Chain Management. Int. J. New Technol. Res. 2018, 4, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedilioglu, O.; Lieret, M.; Schottenhamml, J.; Würfl, T.; Blank, A.; Maier, A.; Franke, J. RGB-D-based human detection and segmentation for mobile robot navigation in industrial environments. VISIGRAPP 2021, 4, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, C.; Baek, I.; Cho, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S. Pallet recognition with multi-task learning for automated guided vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, J.; Prakash, A.; Acuna, D.; Brophy, M.; Jampani, V.; Anil, C.; To, T.; Cameracci, E.; Boochoon, S.; Birchfield, S. Training deep networks with synthetic data: Bridging the reality gap by domain randomization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 969–977. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, J.; Fong, R.; Ray, A.; Schneider, J.; Zaremba, W.; Abbeel, P. Domain randomization for transferring deep neural networks from simulation to the real world. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, J.; To, T.; Sundaralingam, B.; Xiang, Y.; Fox, D.; Birchfield, S. Deep object pose estimation for semantic robotic grasping of household objects. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.10790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2017, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2223–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J.; Tzeng, E.; Park, T.; Zhu, J.Y.; Isola, P.; Saenko, K.; Efros, A.; Darrell, T. Cycada: Cycle-consistent adversarial domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning 2018, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1989–1998. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.; Efros, A.A.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, J.Y. Contrastive Learning for Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2020, Virtual, 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, S.; Huang, Y.; Yi, R.; Zhu, C.; Xu, K. CycleDiff: Cycle Diffusion Models for Unpaired Image-to-image Translation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.06625. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.; Song, J.; Meng, C.; Ermon, S. Dual diffusion implicit bridges for image-to-image translation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.08382. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, G.; Park, T.; Narasimhan, S.; Zhu, J.Y. One-step image translation with text-to-image models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.12036. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Lin, Z.; Wang, F.; Liu, S. CycleVAR: Repurposing Autoregressive Model for Unsupervised One-Step Image Translation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.23347. [Google Scholar]

- Hinterstoisser, S.; Cagniart, C.; Ilic, S.; Sturm, P.; Navab, N.; Fua, P.; Lepetit, V. Gradient response maps for real-time detection of textureless objects. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011, 34, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collet, A.; Martinez, M.; Srinivasa, S.S. The MOPED framework: Object recognition and pose estimation for manipulation. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2011, 30, 1284–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Schmidt, T.; Narayanan, V.; Fox, D. Posecnn: A convolutional neural network for 6d object pose estimation in cluttered scenes. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.00199. [Google Scholar]

- Lepetit, V.; Moreno-Noguer, F.; Fua, P. Epnp: An accurate o (n) solution to the pnp problem. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2009, 81, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Bao, H. Pvnet: Pixel-wise voting network for 6dof pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 4561–4570. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random sample consensus: A paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodaň, T.; Sundermeyer, M.; Drost, B.; Labbé, Y.; Brachmann, E.; Michel, F.; Rother, C.; Matas, J. BOP challenge 2020 on 6D object localization. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 2020, Virtual, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 577–594. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Song, J.; Huang, Q. Hybridpose: 6d object pose estimation under hybrid representations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2020, Virtual, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, B.; Sinha, S.N.; Fua, P. Real-time seamless single shot 6d object pose prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 292–301. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Fua, P.; Wang, W.; Salzmann, M. Single-stage 6d object pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2020, Virtual, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2930–2939. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Ji, X.; Xiang, Y.; Fox, D. Deepim: Deep iterative matching for 6d pose estimation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 2018, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 683–698. [Google Scholar]

- Labbé, Y.; Carpentier, J.; Aubry, M.; Sivic, J. CosyPose: Consistent multi-view multi-object 6D pose estimation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.08465. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, Y.; Song, R.; Li, J.; Hu, Y. Shape-constraint recurrent flow for 6d object pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2023, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 4831–4840. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Lin, K.Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Rnnpose: 6-dof object pose estimation via recurrent correspondence field estimation and pose optimization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 4669–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Vutukur, S.R.; Yu, H.; Shugurov, I.; Busam, B.; Yang, S.; Ilic, S. Nerf-pose: A first-reconstruct-then-regress approach for weakly-supervised 6d object pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 2023, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 2123–2133. [Google Scholar]

- Haugaard, R.L.; Buch, A.G. Surfemb: Dense and continuous correspondence distributions for object pose estimation with learnt surface embeddings. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 6749–6758. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Mao, Y.; Bala, R.; Hadap, S. Mrc-net: 6-dof pose estimation with multiscale residual correlation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2024, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 10476–10486. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Sun, W.; Yang, H.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, C.; Zheng, J.; Liu, X.; Rahmani, H.; Sebe, N.; Mian, A. Deep learning-based object pose estimation: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.07801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, C.; Shome, R.; Bekris, K.E.; De Souza, A.F. A dataset for improved rgbd-based object detection and pose estimation for warehouse pick-and-place. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2016, 1, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epic Games. Unreal Engine; Epic Games, Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hinterstoisser, S.; Lepetit, V.; Ilic, S.; Holzer, S.; Bradski, G.; Konolige, K.; Navab, N. Model based training, detection and pose estimation of texture-less 3d objects in heavily cluttered scenes. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision 2012, Daejeon, Korea, 5–9 November 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 548–562. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Iwase, S.; Kitani, K.M. Stereobj-1m: Large-scale stereo image dataset for 6d object pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 2021, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10870–10879. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Resolution | Training Size | Validation Size | Test Size | Synthetic | Real |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPP | - | - | k | ✕ | ✓ | |

| WSPP | 50k | 5k | - | ✓ | ✕ | |

| RSPP | 50k | 5k | - | ✓ | ✕ | |

| Adapted-WSPP | 50k | 5k | - | ✓ | ✕ |

| (cm) | (deg) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | Roll | Pitch | Yaw | |

| Mean | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| STD | 30 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| (cm) | (deg) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | Roll | Pitch | Yaw | |

| Mean | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| STD | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

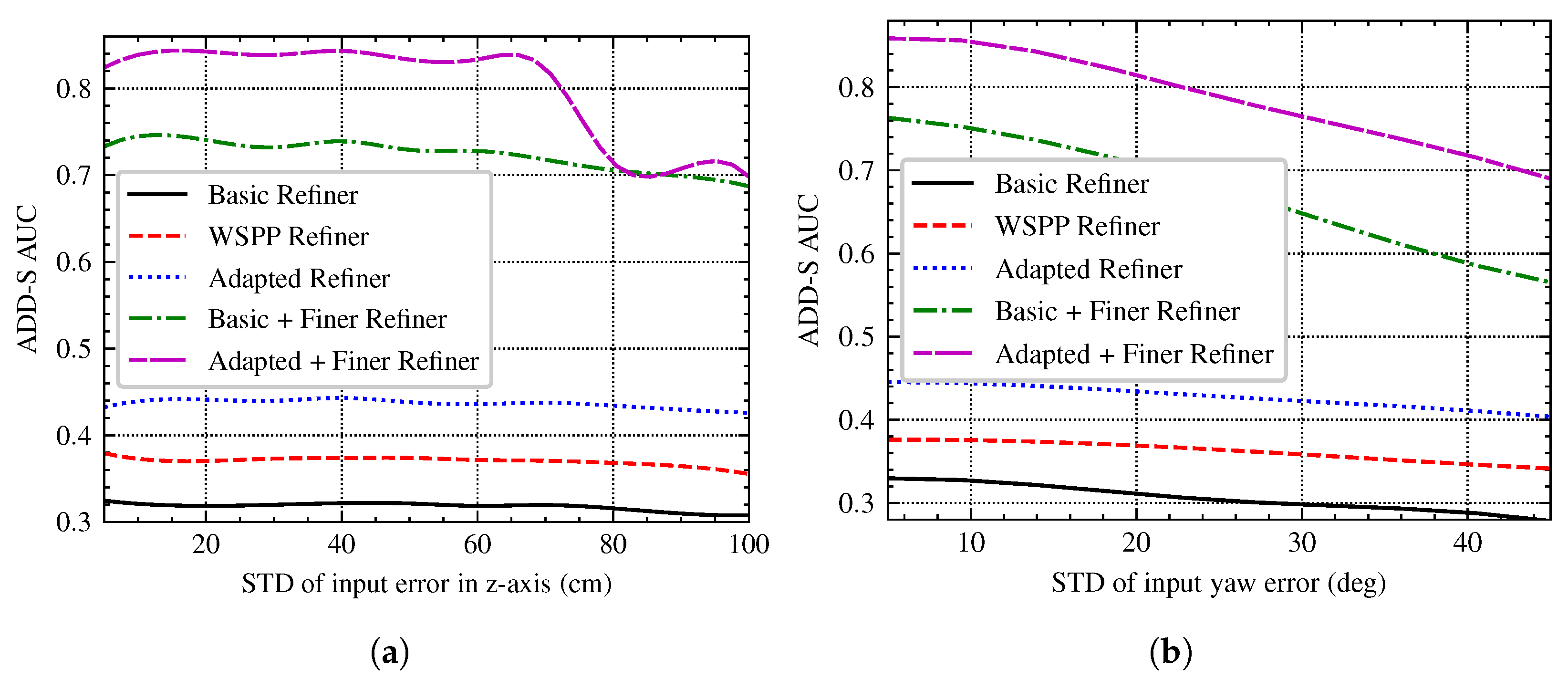

| Exp. | STD (cm) | STD (deg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | Roll | Pitch | Yaw | |

| 1 | 30 | 30 | 10–100 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| 2 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 15 | 15–45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

ElMoaqet, H.; Rashed, M.; Bakr, M. Multi-Stage Domain-Adapted 6D Pose Estimation of Warehouse Load Carriers: A Deep Convolutional Neural Network Approach. Machines 2025, 13, 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121126

ElMoaqet H, Rashed M, Bakr M. Multi-Stage Domain-Adapted 6D Pose Estimation of Warehouse Load Carriers: A Deep Convolutional Neural Network Approach. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121126

Chicago/Turabian StyleElMoaqet, Hisham, Mohammad Rashed, and Mohamed Bakr. 2025. "Multi-Stage Domain-Adapted 6D Pose Estimation of Warehouse Load Carriers: A Deep Convolutional Neural Network Approach" Machines 13, no. 12: 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121126

APA StyleElMoaqet, H., Rashed, M., & Bakr, M. (2025). Multi-Stage Domain-Adapted 6D Pose Estimation of Warehouse Load Carriers: A Deep Convolutional Neural Network Approach. Machines, 13(12), 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121126