Block–Neighborhood-Based Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm for Distributed Resource-Constrained Hybrid Flow Shop with Machine Breakdown

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Literature Review of Distributed Hybrid Flow Shop

2.2. Scheduling Problem with Machine Breakdown

2.3. Scheduling Problem with Resource Constraints

2.4. Literature Analysis

3. Problem Description

3.1. Distributed Hybrid Flow Shop Scheduling

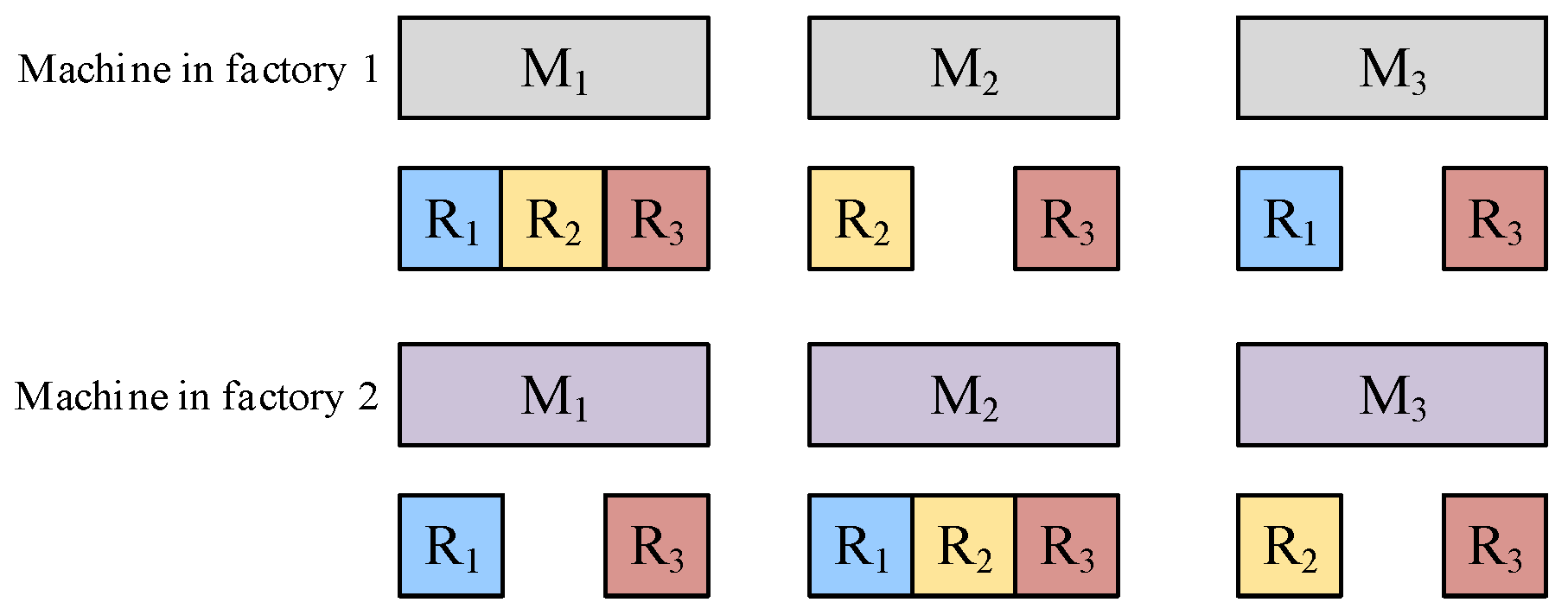

3.2. Resource Constraints

3.3. Machine Breakdown

3.4. Notations and Parameters

| Indices | |

| Index of jobs. | |

| Index of stages. | |

| Index of machines. | |

| Index of factories. | |

| Index of resources. | |

| Index of machine processing positions. | |

| Index of failure. | |

| Parameters | |

| Number of stages. | |

| Number of factories. | |

| Number of jobs. | |

| Number of machines. | |

| Number of resource types. | |

| Number of failures. | |

| A large number. | |

| The operation associated with job j at the sth position. | |

| The collection of machines in the sth stage. | |

| Processing time of job j in machine m at stage s. | |

| The beginning time of the operation of job j in factory f during the sth stage. | |

| The end time of the operation of the job j in factory f during the sth stage. | |

| The begin time of processing at the rth position on machine m within factory f. | |

| The end time of processing at the rth position on machine m within factory f. | |

| The start time of a breakdown at the rth position, involving failure b, on machine m within factory f. | |

| The completion time of a breakdown at the rth position, involving failure b, on machine m within factory f. | |

| The start time of waiting for resource res at the rth position on machine m within factory f. | |

| The completion time of waiting for resource res at the rth position on machine m within factory f. | |

| Unit energy consumption except machine energy. | |

| The wait time for resource res for job j on machine m at the rth position in stage s within factory f. | |

| The duration of failure b for job j on machine m at the rth position during stage s in factory f. | |

| Unit energy consumption of waiting resource of machine m. | |

| Unit energy consumption of failure of machine m. | |

| Unit energy consumption of processing machine m. | |

| Decision variables | |

| A binary variable (0/1), assigned the value 1 when job j is being processed at the rth position on machine m during stage s in factory f. | |

| A binary variable (0/1), with the value 1 when job j is being processed with resource res at the rth position on machine m during stage s in factory f. | |

| A binary variable (0/1), with a value of 1 when job j is in the processing stage s within factory f. | |

| A binary variable (0/1), set to 1 when job j is being processed with failure b at the rth position on machine m during stage s in factory f. | |

| The DRCHFSP-MB mathematical model can be formulated. | |

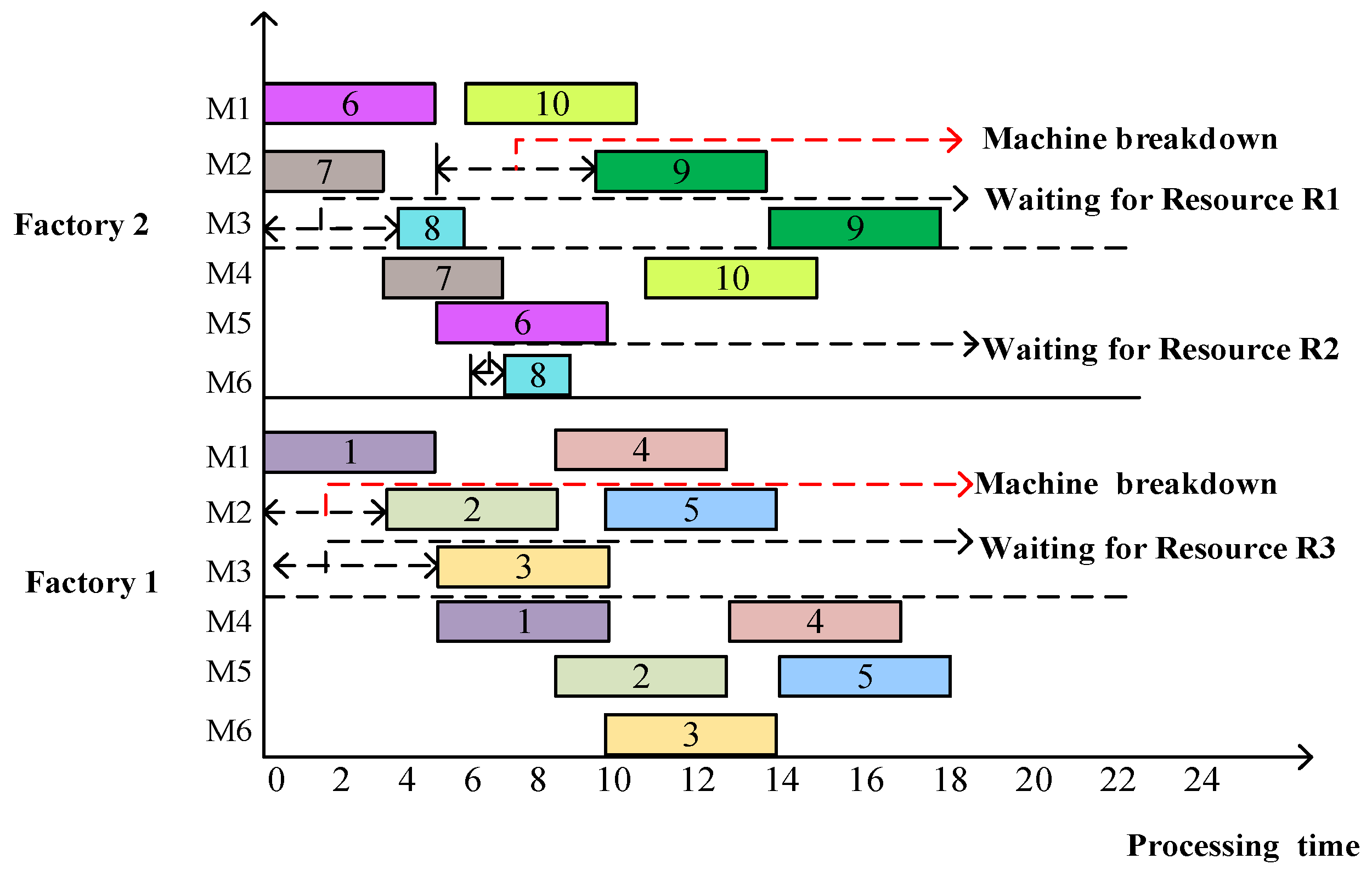

3.5. Problem-Specific Example

3.6. Problem-Specific Properties

4. The Proposed Algorithm

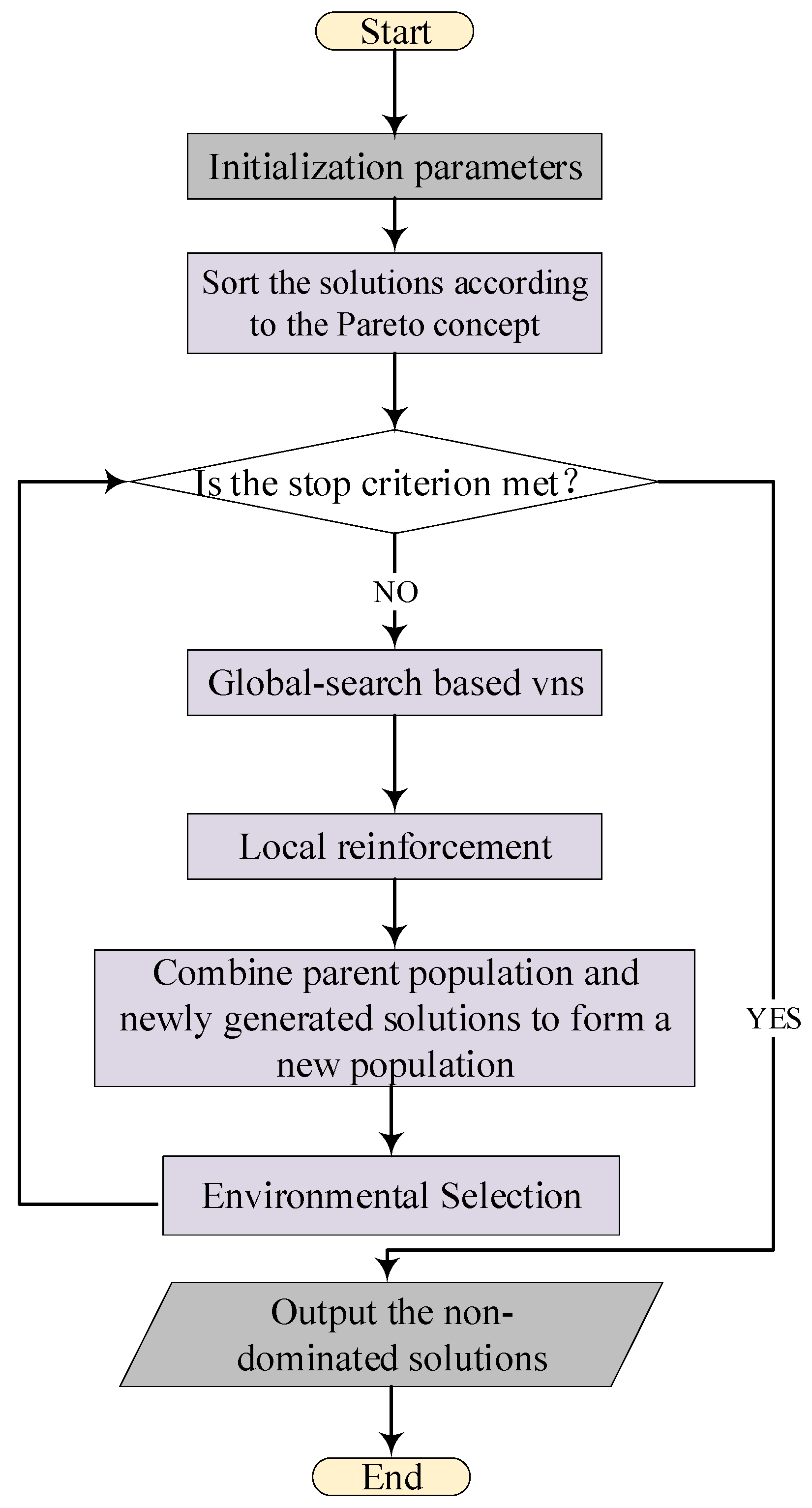

4.1. BNMOEA

4.2. Encoding

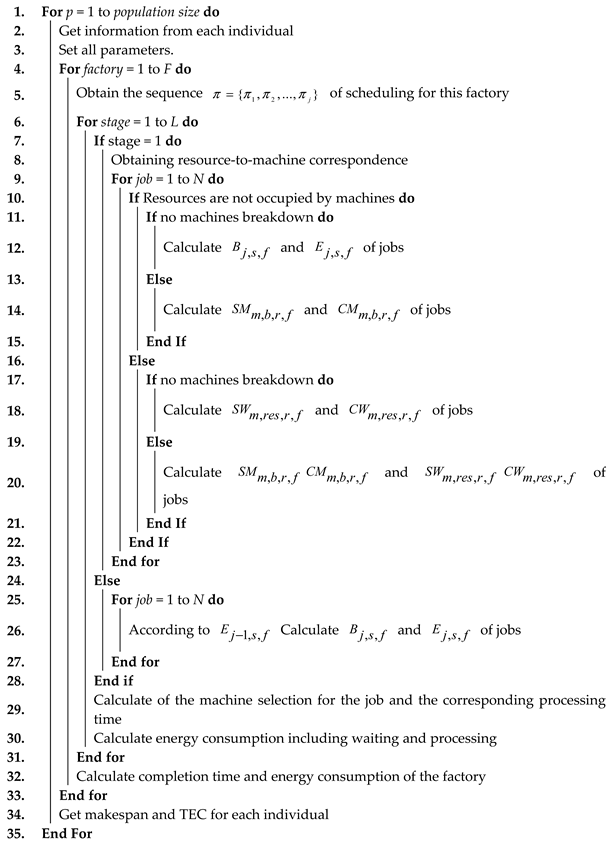

4.3. Decoding

| Algorithm 1 Decoding mechanism |

|

4.4. Population Initialization

| Algorithm 2 Hybrid initialization method |

|

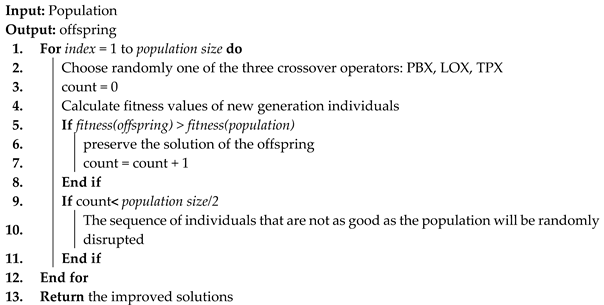

4.5. Global Search

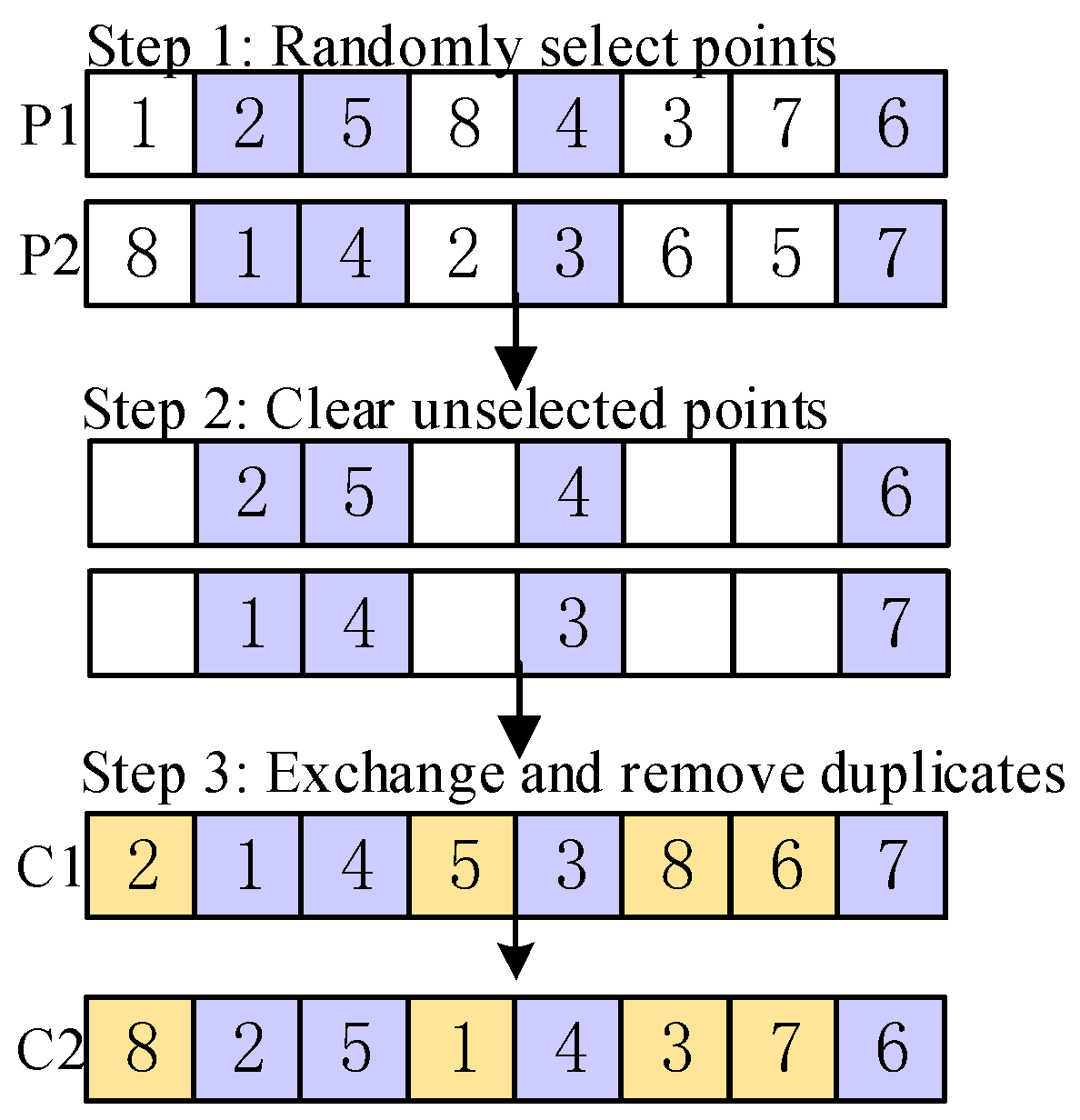

- Position-based Crossover

| Algorithm 3 Global search |

|

- 2.

- Linear order crossover

- 3.

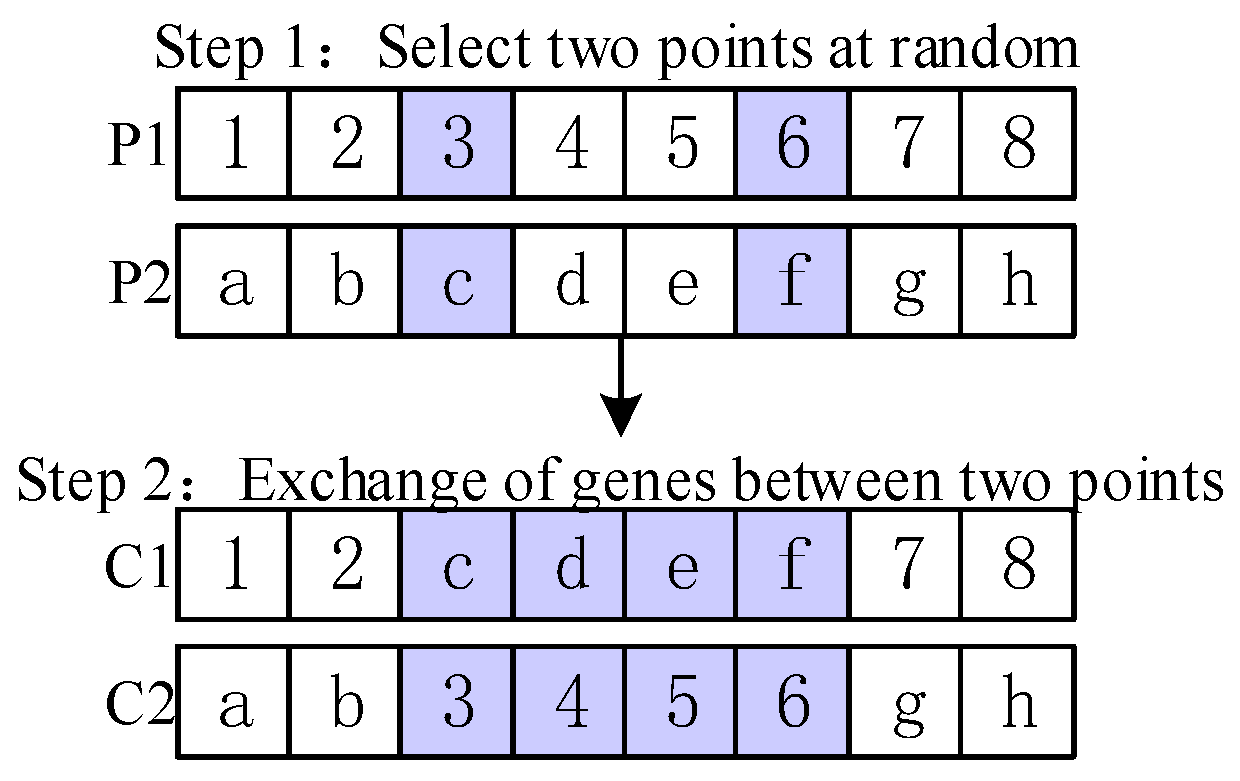

- Two-points crossover

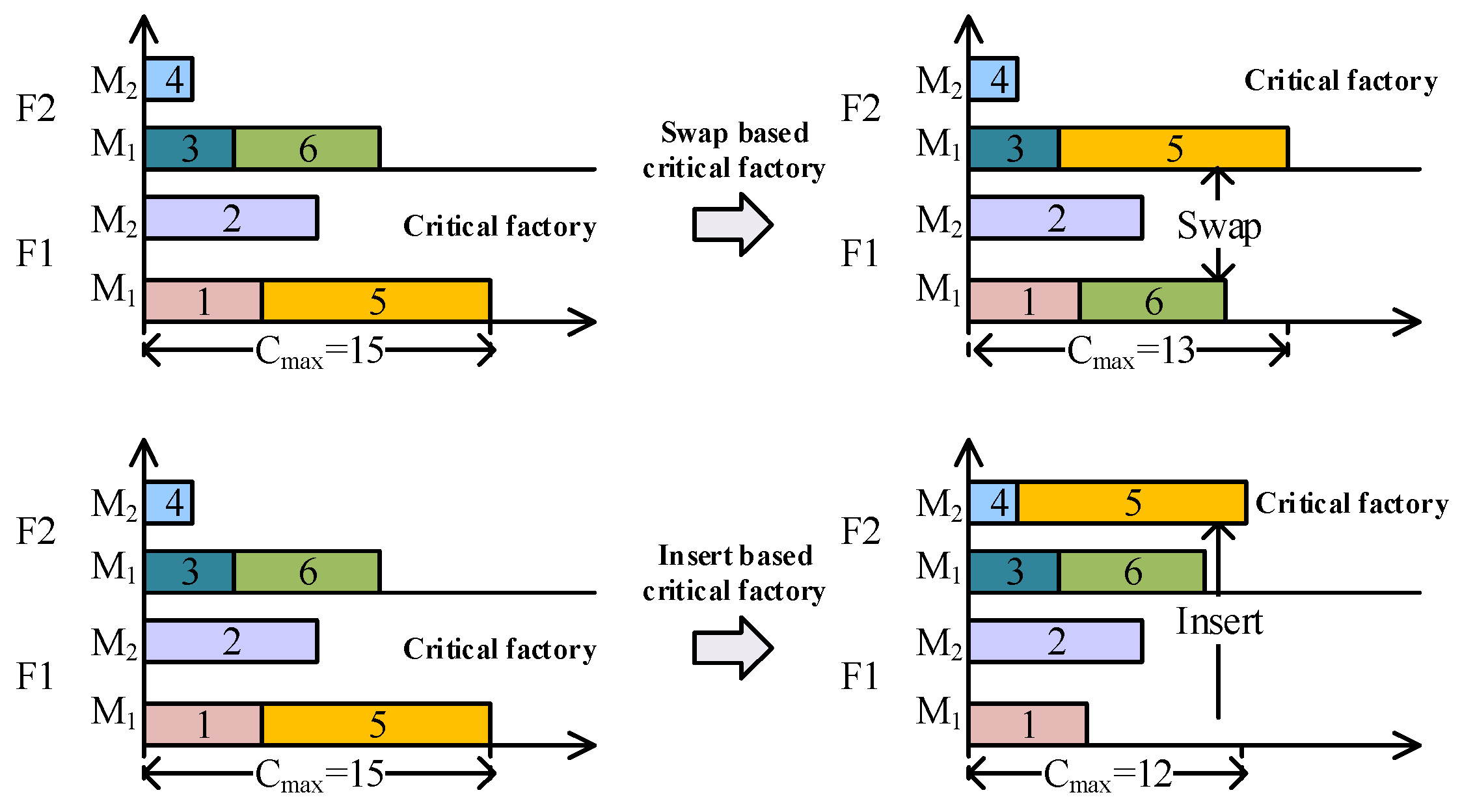

4.6. Local Reinforcement-Based Critical Factory

| Algorithm 4 Local reinforcement-based critical factory |

|

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Experimental Settings

5.2. Performance Indicators

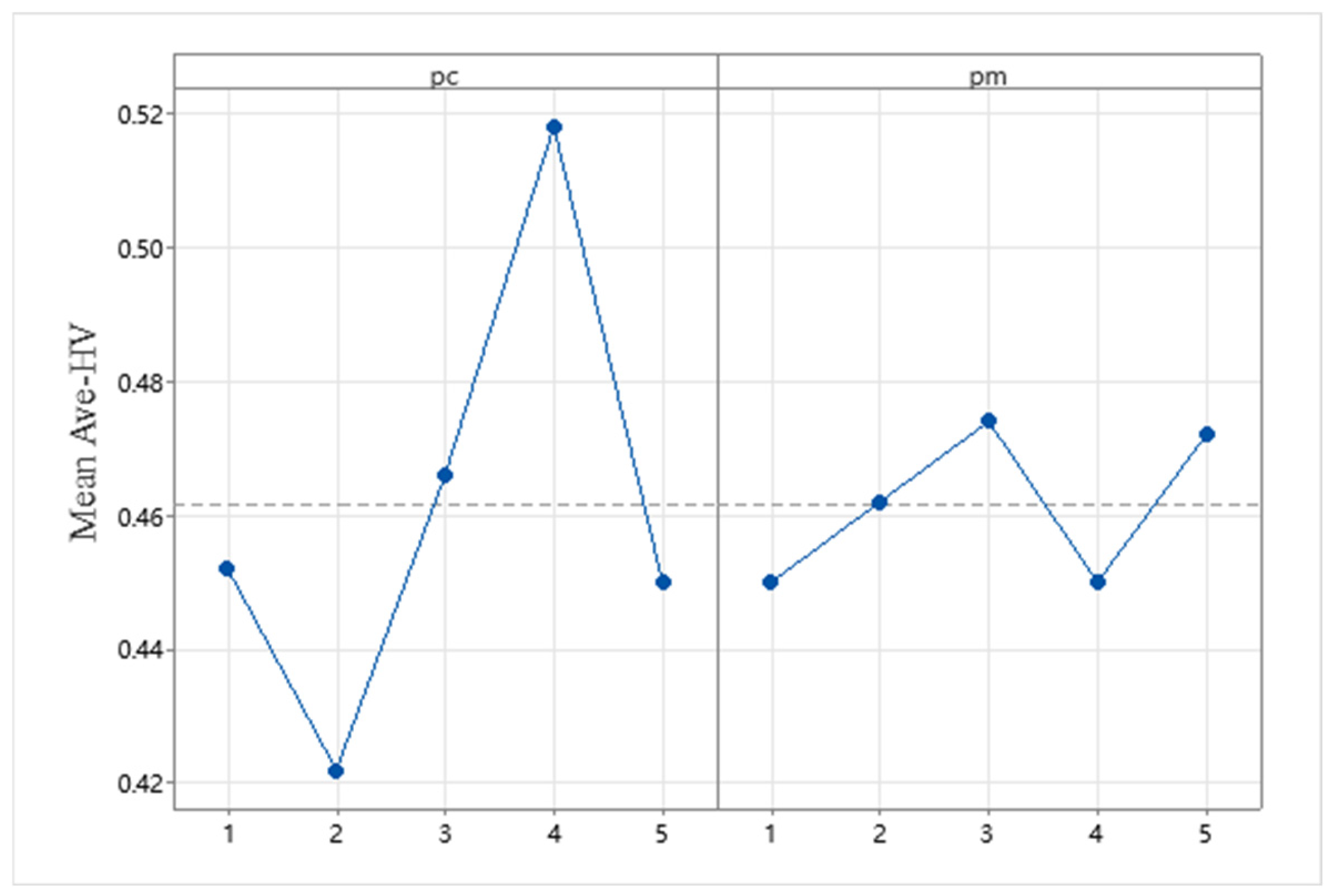

5.3. Parameter Setting

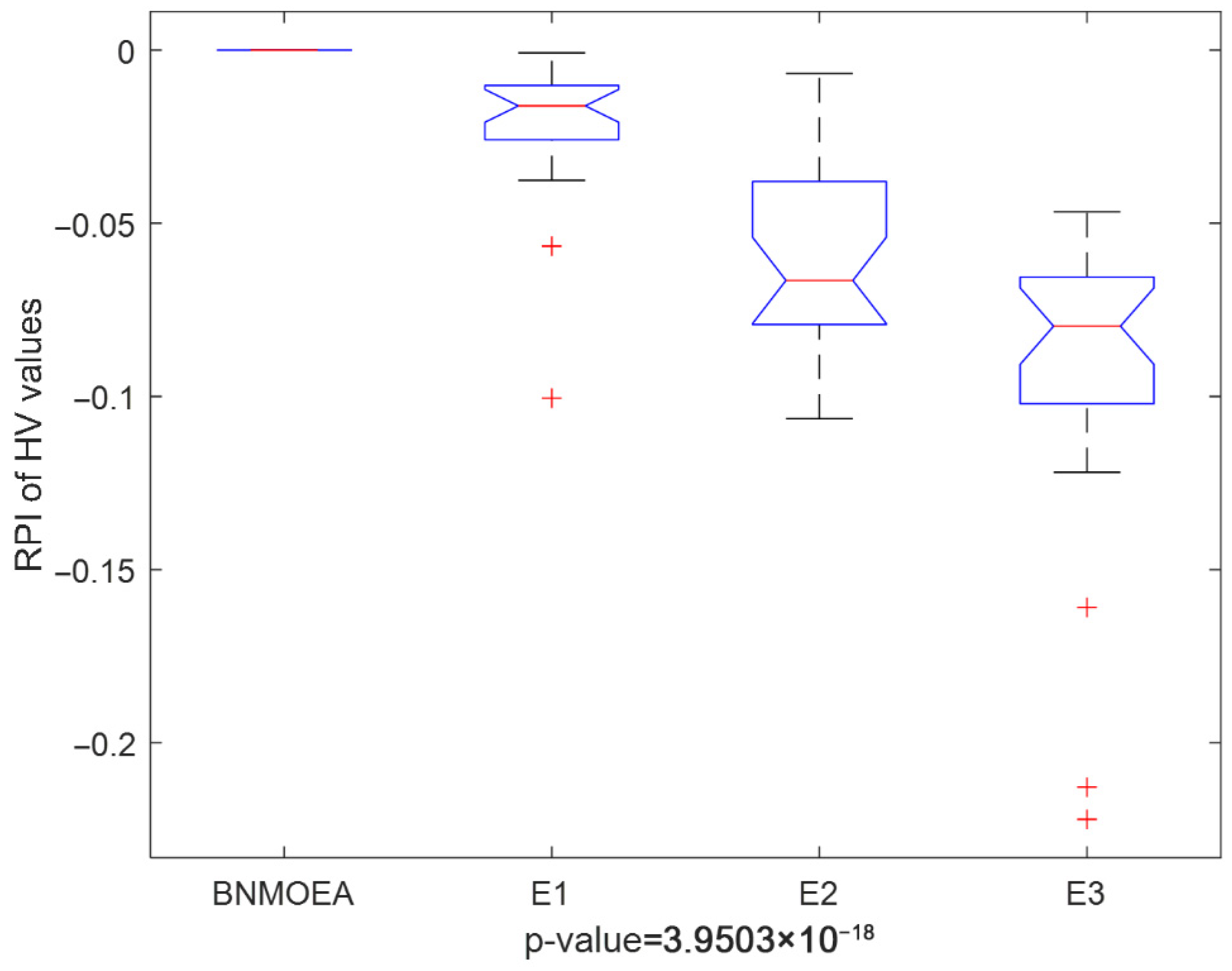

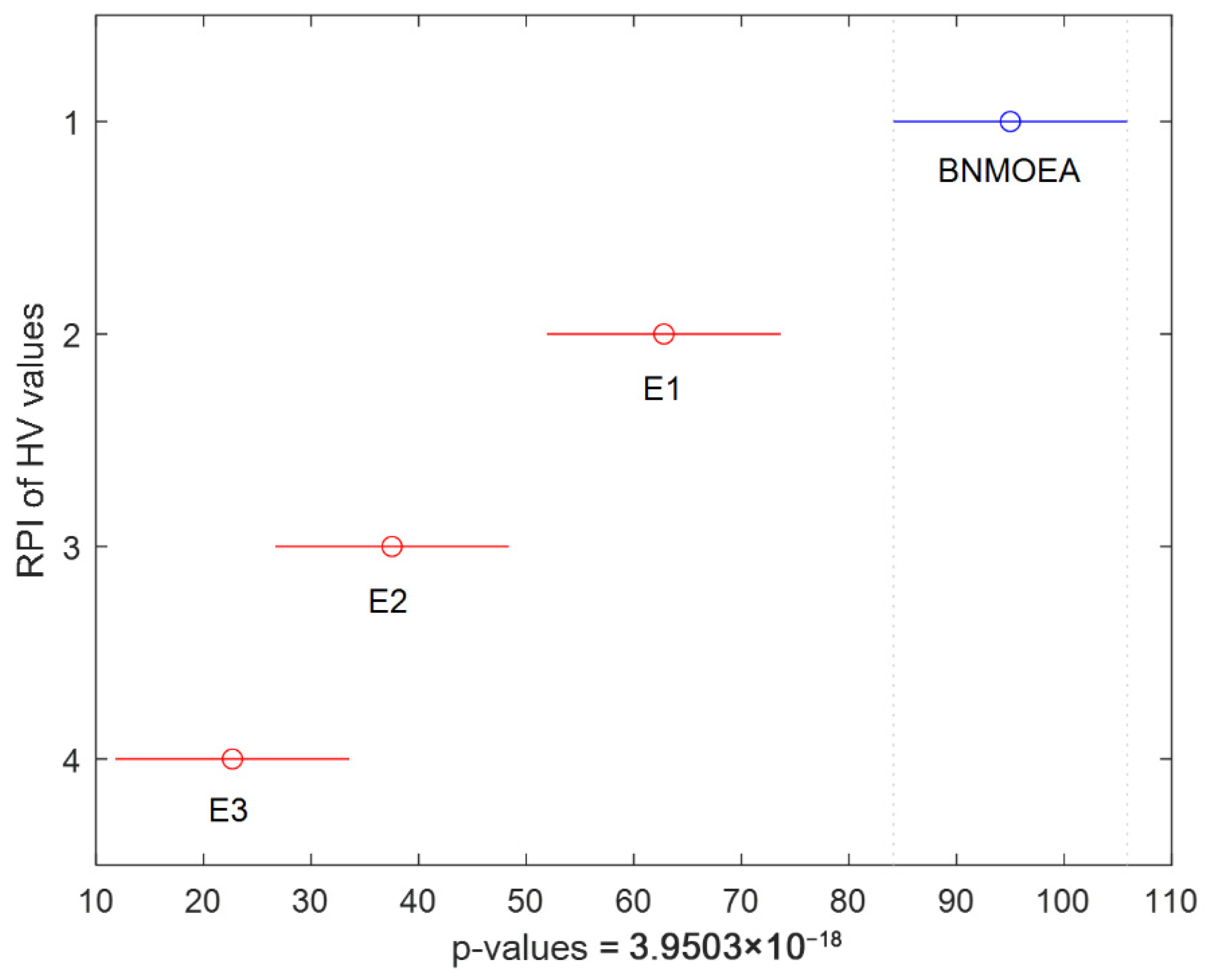

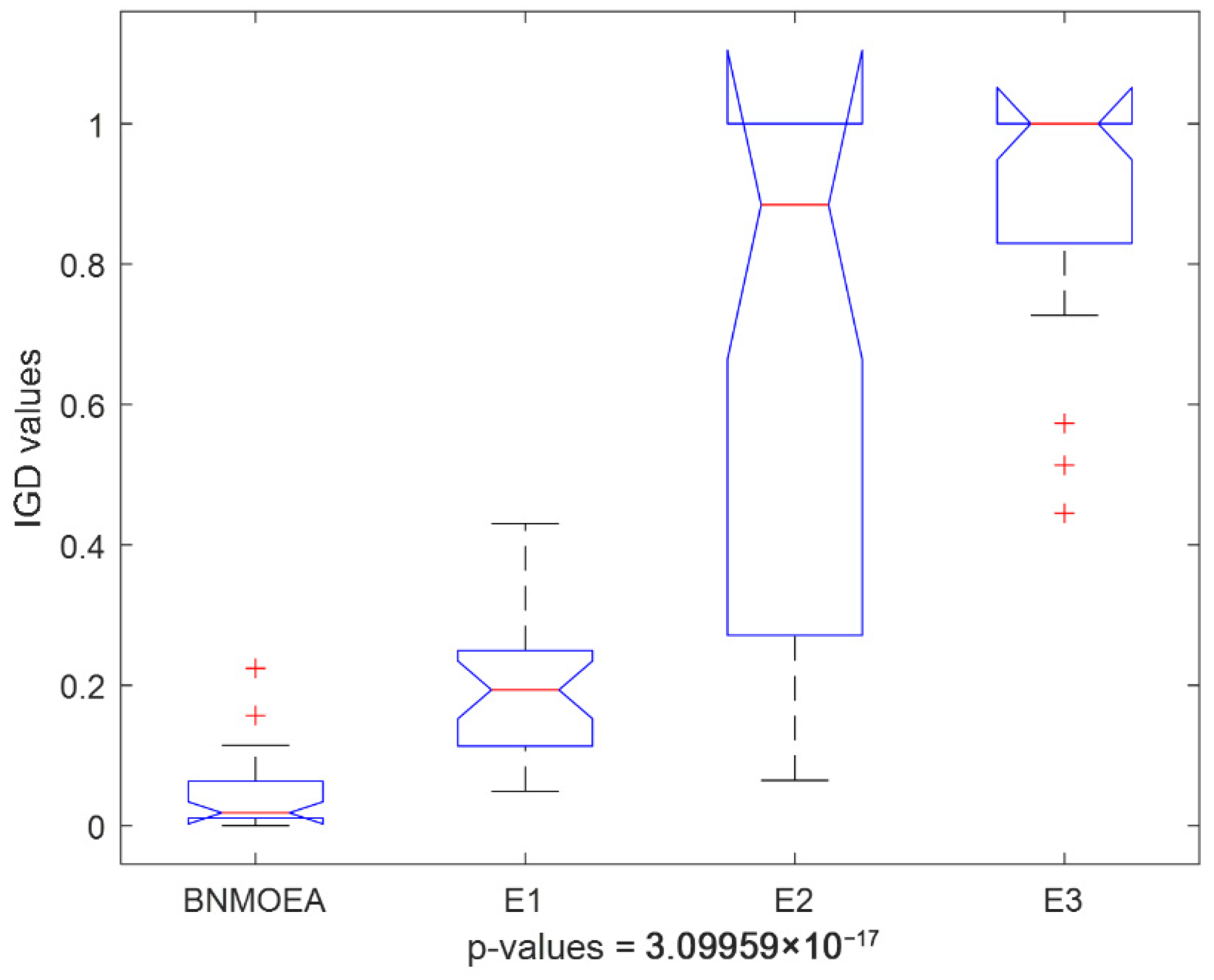

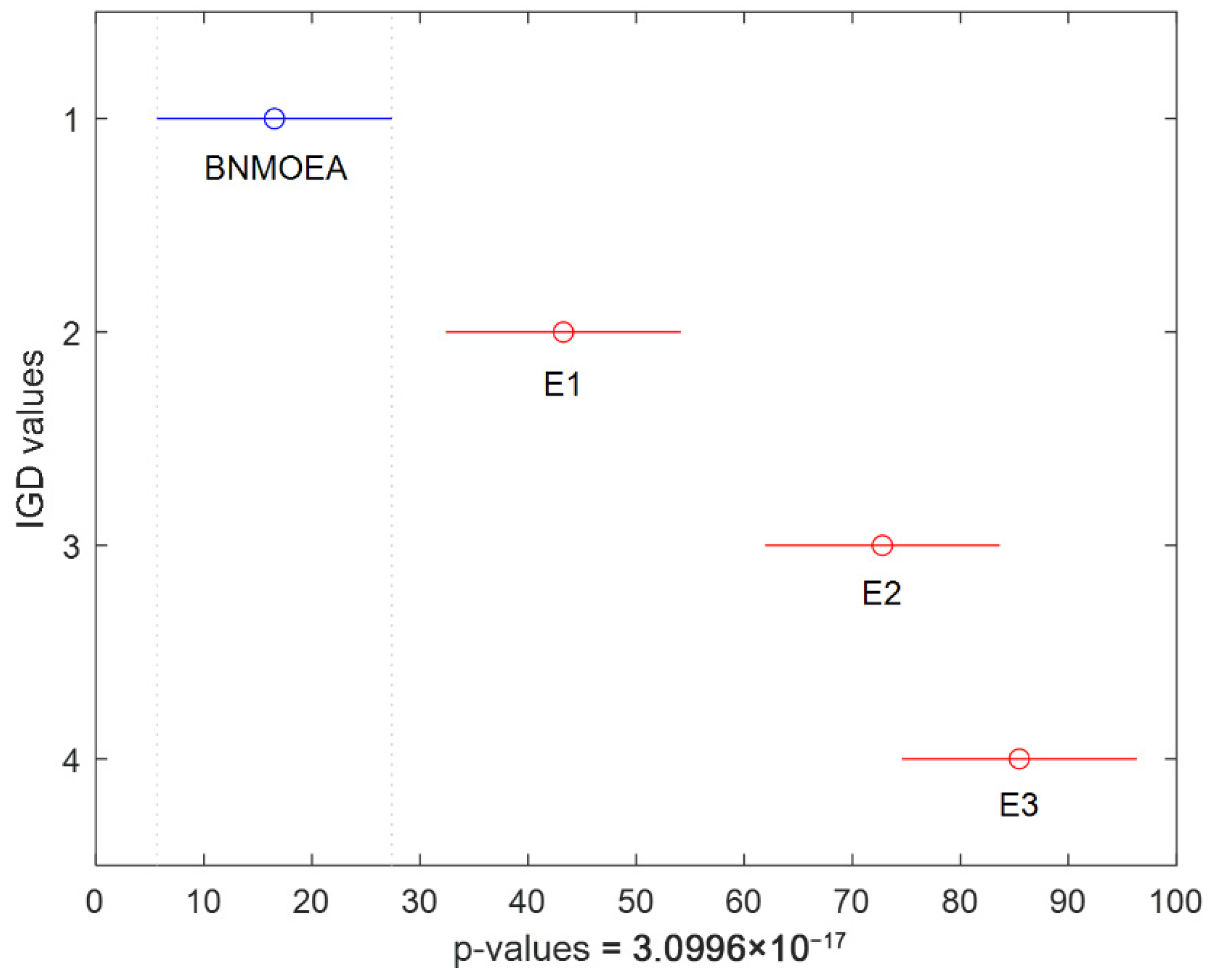

5.4. Ablation Experiments

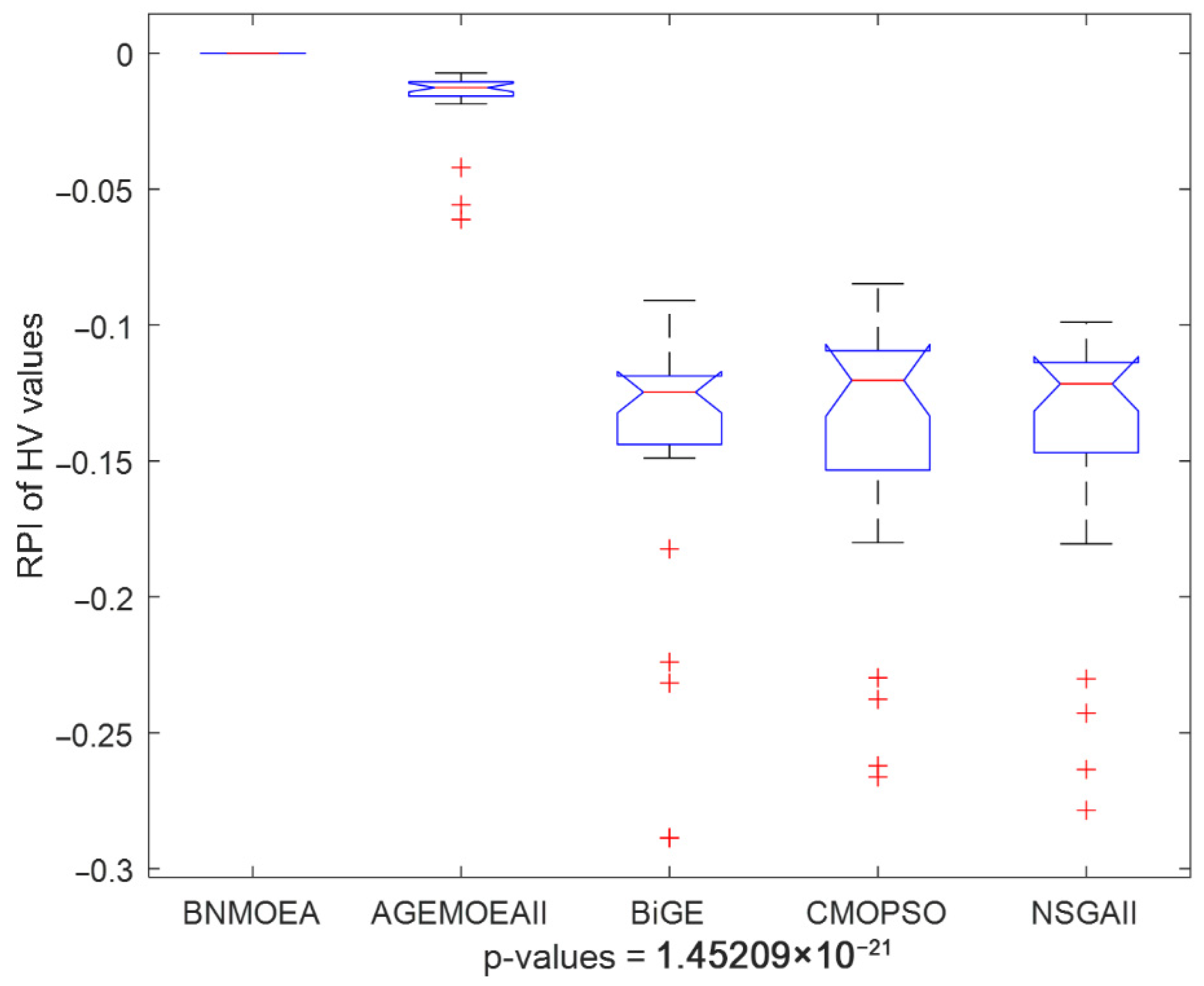

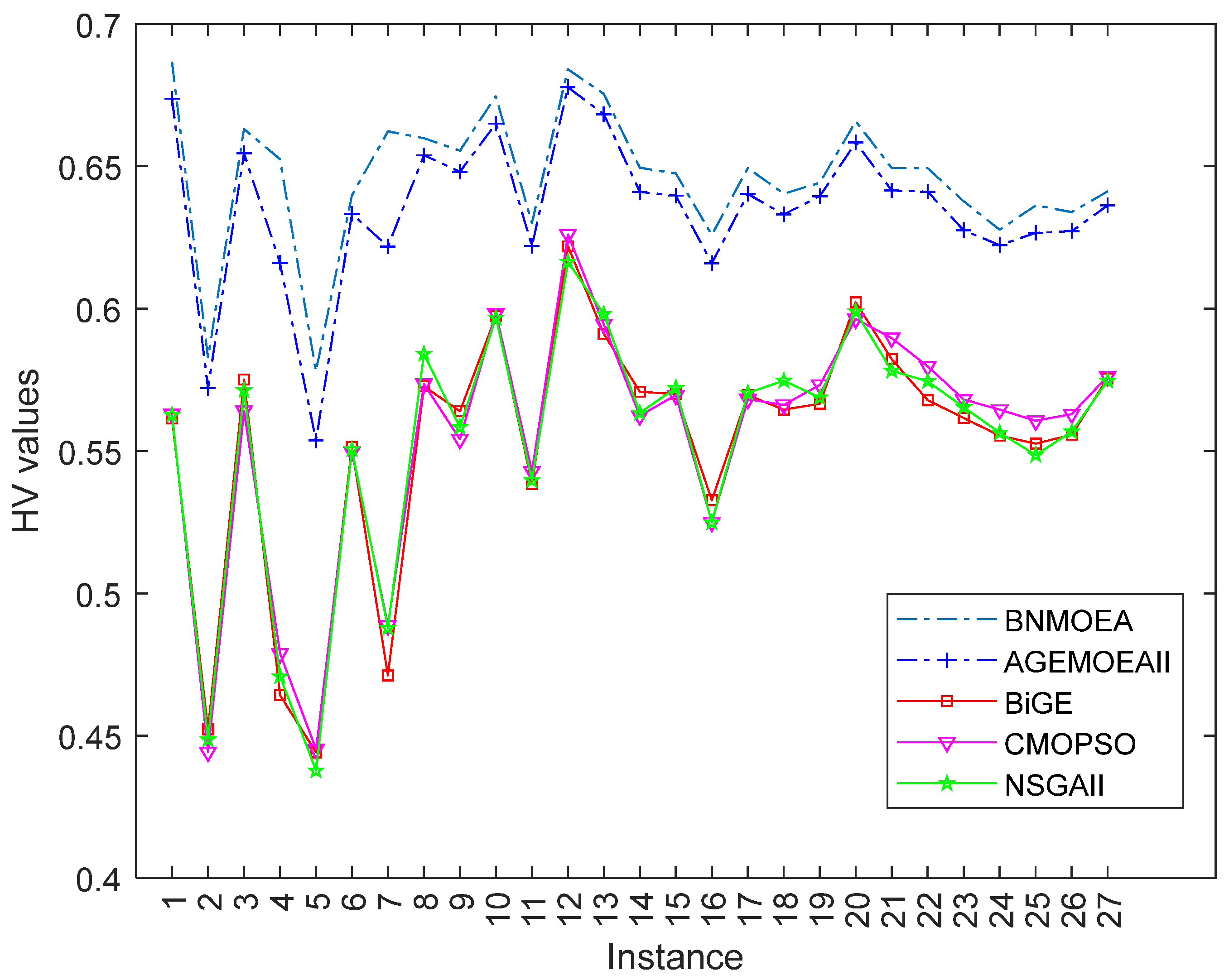

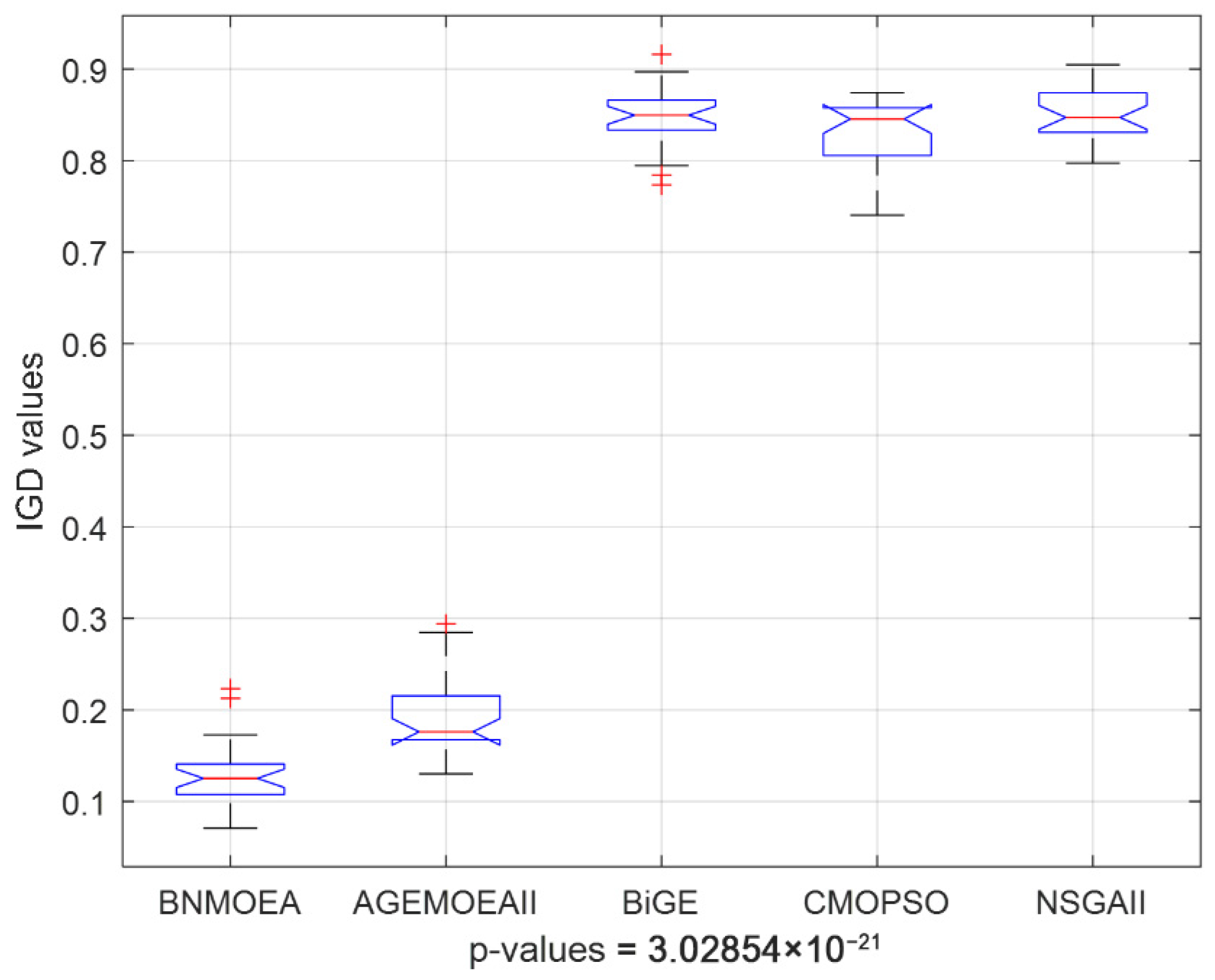

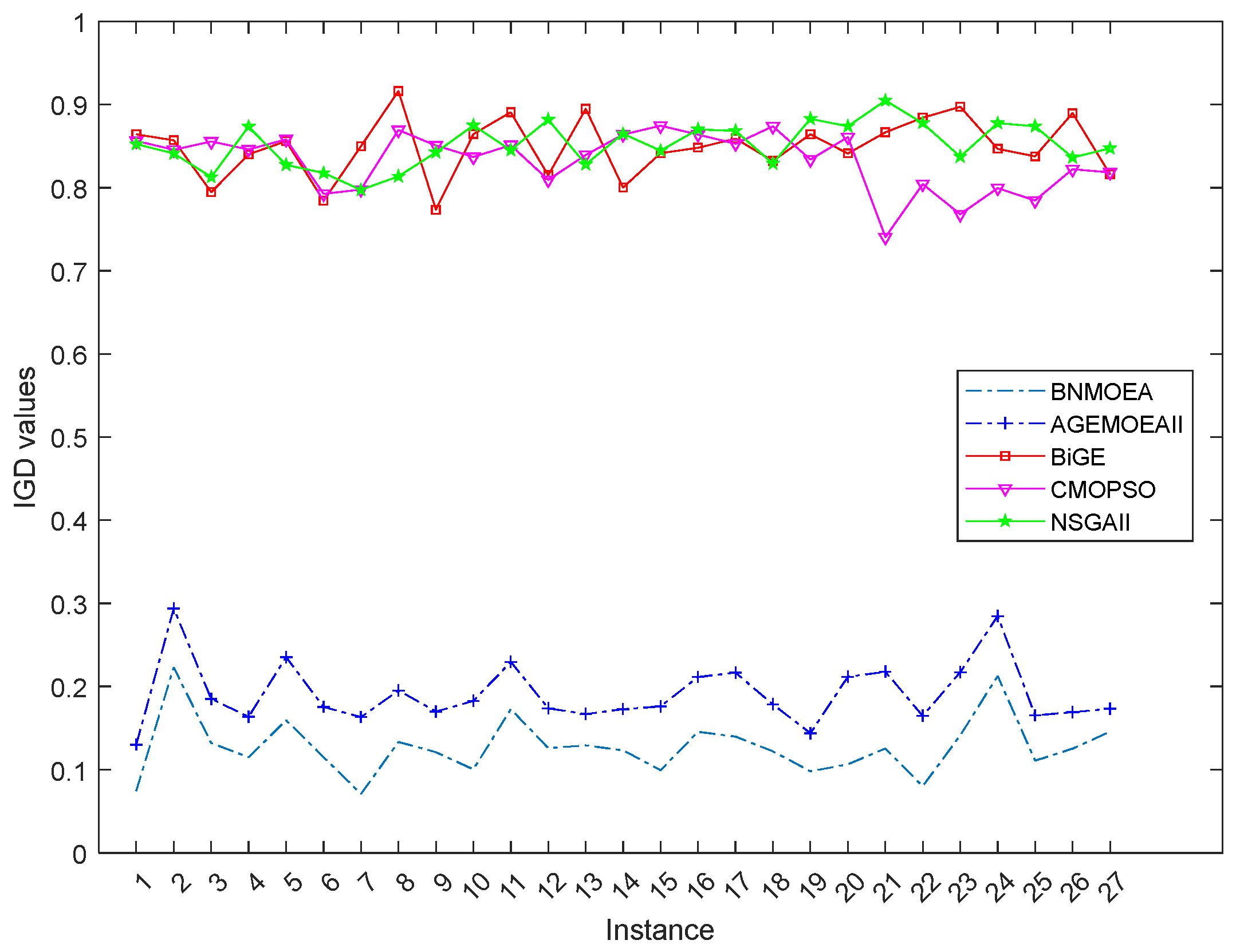

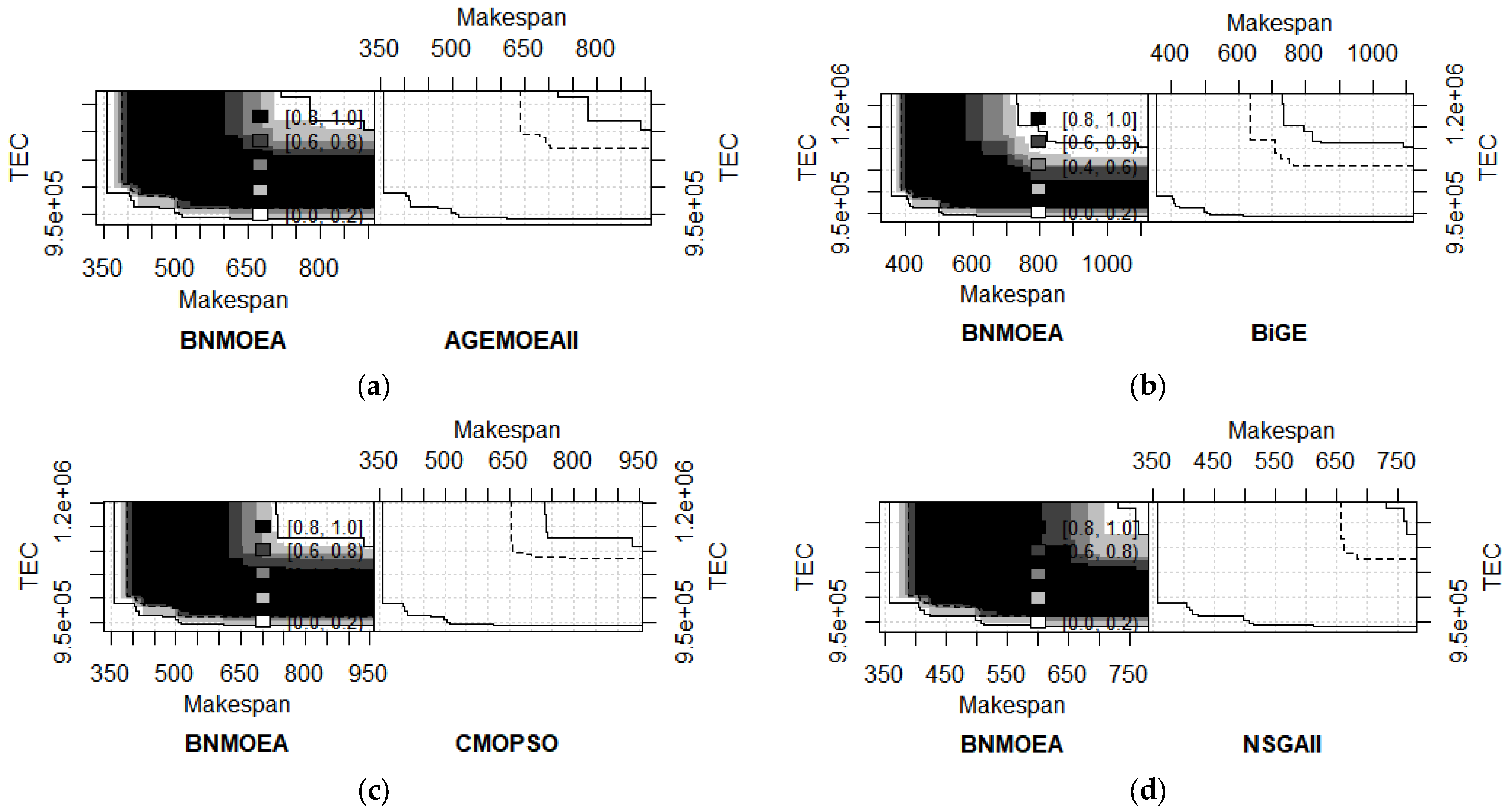

5.5. Analysis of Comparative Algorithms

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Gao, K.; Duan, P. A hybrid graph-based imitation learning method for a realistic distributed hybrid flow shop with family setup time. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 7291–7304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Li, J.; Du, Z.; Yu, X.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Li, J. A Q-learning driven multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for worker fatigue dual-resource-constrained distributed hybrid flow shop. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 175, 106919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Du, B.; Huang, G.Q.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Hybrid flow shop scheduling considering machine electricity consumption cost. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 146, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liao, W.; Zhang, L. Hybrid energy-efficient scheduling measures for flexible job-shop problem with variable machining speeds. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 197, 116785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Pan, Q.K.; Gao, L.; Li, X. Multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling problem considering machine switching off-on operation. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 39, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtahi, Z.; Sahraeian, R. Robust and Stable Flow Shop Scheduling Problem Under Uncertain Processing Times and Machines Disruption. Int. J. Eng. Trans. A Basics 2021, 34, 935–947. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.M.H.; Sana, S.S.; Rostami, M. Assembly flow shop scheduling problem considering machine eligibility restrictions and auxiliary resource constraints. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2022, 9, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, K.C.; Lin, S.W. Minimizing makespan for the distributed hybrid flowshop scheduling problem with multiprocessor tasks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 92, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, F.; Pan, Q.K.; Gao, L.; Tasgetiren, M.F. An artificial bee colony algorithm for the distributed hybrid flowshop scheduling problem. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 39, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhou, R.; Lei, D. Dynamic shuffled frog-leaping algorithm for distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling with multiprocessor tasks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 90, 103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Duan, P.; Pan, Q. Knowledge-Based Reinforcement Learning and Estimation of Distribution Algorithm for Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2022, 7, 1036–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, R.; Chu, F.; Yu, J. Variable neighborhood search-based methods for integrated hybrid flow shop scheduling with distribution. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 8917–8936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, J. A cooperative coevolution algorithm for multi-objective fuzzy distributed hybrid flow shop. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 194, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Shao, Z.; Pi, D. Modeling and multi-neighborhood iterated greedy algorithm for distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling problem. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 194, 105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, L. A Bi-Population Cooperative Memetic Algorithm for Distributed Hybrid Flow-Shop Scheduling. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2021, 5, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Shao, Z.; Pi, D. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on multiple neighborhoods local search for multi-objective distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 183, 115453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B. A wale optimization algorithm for distributed flow shop with batch delivery. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 13181–13194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, L. A Cooperative Memetic Algorithm with Learning-Based Agent for Energy-Aware Distributed Hybrid Flow-Shop Scheduling. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2022, 26, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yin, L. A Pareto-based hybrid iterated greedy algorithm for energy-efficient scheduling of distributed hybrid flowshop. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 204, 117555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Shao, Z.; Pi, D. A network memetic algorithm for energy and labor-aware distributed heterogeneous hybrid flow shop scheduling problem. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2022, 75, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Gao, K.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, B.; Sang, H.; Zhang, C. Novel MILP and CP models for distributed hybrid flowshop scheduling problem with sequence-dependent setup times. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2022, 71, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.; Su, B. A multi-class teaching–learning-based optimization for multi-objective distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 263, 110252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Sun, H. Toward automated algorithm configuration for distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling with multiprocessor tasks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 264, 110309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Zandieh, M.; Alem-Tabriz, A. Scheduling hybrid flow shop with sequence-dependent setup times and machines with random breakdowns. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 42, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, M.; Gholami, M. An immune algorithm for scheduling a hybrid flow shop with sequence-dependent setup times and machines with random breakdowns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 47, 6999–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, E.; Sadjadi, S.J. A hybrid method for flowshops scheduling with condition-based maintenance constraint and machines breakdown. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Choi, S.H. A decomposition-based approach to flexible flow shop scheduling under machine breakdown. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 50, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabi, M.; Ghomi, S.M.T.F.; Jolai, F. A two-stage hybrid flowshop scheduling problem in machine breakdown condition. J. Intell. Manuf. 2011, 24, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Huang, Y.; Qin, H. A fuzzy logic-based hybrid estimation of distribution algorithm for distributed permutation flowshop scheduling problems under machine breakdown. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2017, 67, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adressi, A.; Tasouji Hassanpour, S.; Azizi, V. Solving group scheduling problem in no-wait flexible flowshop with random machine breakdown. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2016, 5, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazayeli, M.; Aleagha, M.R.; Bashirzadeh, R.; Shafaei, R. A hybrid meta-heuristic algorithm for flowshop robust scheduling under machine breakdown uncertainty. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2016, 29, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidgar, H.; Rad, S.T.; Shafaei, R. Scheduling of assembly flow shop problem and machines with random breakdowns. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 29, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Gong, D.; Jin, Y.; Pan, Q. Evolutionary Multiobjective Blocking Lot-Streaming Flow Shop Scheduling with Machine Breakdowns. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 49, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadayonirad, S.; Seidgar, H.; Fazlollahtabar, H.; Shafaei, R. Robust scheduling in two-stage assembly flow shop problem with random machine breakdowns: Integrated meta-heuristic algorithms and simulation approach. Assem. Autom. 2019, 39, 944–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichelvam, M.K.; Geetha, M. A hybrid algorithm to solve the stochastic flow shop scheduling problems with machine break down. Int. J. Enterp. Netw. Manag. 2019, 10, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidgar, H.; Fazlollahtabar, H.; Zandieh, M. Scheduling two-stage assembly flow shop with random machines breakdowns: Integrated new self-adapted differential evolutionary and simulation approach. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 8377–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branda, A.; Castellano, D.; Guizzi, G.; Popolo, V. Metaheuristics for the flow shop scheduling problem with maintenance activities integrated. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Xu, Y. A multi-dimensional co-evolutionary algorithm for multi-objective resource-constrained flexible flowshop with robotic transportation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 170, 112689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, S.S.; Hwang, S.T. GA-based resource-constrained flow-shop scheduling model for mixed precast production. Autom. Constr. 2002, 11, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarboui, B.; Damak, N.; Siarry, P.; Rebai, A. A combinatorial particle swarm optimization for solving multi-mode resource-constrained project scheduling problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 195, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnamian, J.; Fatemi Ghomi, S.M.T. Hybrid flowshop scheduling with machine and resource-dependent processing times. Appl. Math. Model. 2011, 35, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, M.; Asokan, P.; Anilkumar, N.; Page, T. A GRASP algorithm for flexible job-shop scheduling problem with limited resource constraints. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 2409–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.C.E.; Lin, B.M.T.; Huang, H.L. Resource-constrained flowshop scheduling with separate resource recycling operations. Comput. Oper. Res. 2012, 39, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Lee, C.K.; Ho, W. Multi-level genetic algorithm for the resource-constrained re-entrant scheduling problem in the flow shop. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2013, 26, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożejko, W.; Hejducki, Z.; Uchroński, M.; Wodecki, M. Solving Resource-Constrained Construction Scheduling Problems with Overlaps by Metaheuristic. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2014, 20, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laribi, I.; Yalaoui, F.; Belkaid, F.; Sari, Z. Heuristics for solving flow shop scheduling problem under resources constraints. IFAC-Pap. 2016, 49, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.; Chakrabortty, R.; Ryan, M. Memetic algorithm for solving resource constrained project scheduling problems. Autom. Constr. 2020, 111, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Fernandez-Viagas, V.; Framinan, J. Solving the hybrid flow shop scheduling problem with limited human resource constraint. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 146, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufellouh, R.; Belkaid, F. Bi-objective optimization algorithms for joint production and maintenance scheduling under a global resource constraint: Application to the permutation flow shop problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 122, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Gao, K.; Pan, Q. Optimizing dynamic flexible job shop scheduling using an evolutionary multi-task optimization framework and genetic programming. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2025, 29, 1502–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Deng, Q.; Gong, G.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Q. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms with heuristic decoding for hybrid flow shop scheduling problem with worker constraint. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A.; Hosseini, S.M.H. Auxiliary resource planning in a flexible flow shop scheduling problem considering stage skipping. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 138, 105625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhao, F.; Yu, Y. Two-stage learning scatter search algorithm for the distributed hybrid flow shop scheduling problem with machine breakdown. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 259, 125344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Y. PlatEMO: A MATLAB platform for evolutionary multi-objective optimization [educational forum]. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2017, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panichella, A. An improved Pareto front modeling algorithm for large-scale many-objective optimization. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 9–13 July 2022; pp. 565–573. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, R.; Qiu, J.; Jin, Y. A competitive mechanism based multi-objective particle swarm optimizer with fast convergence. Inf. Sci. 2018, 427, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, X. Bi-goal evolution for many-objective optimization problems. Artif. Intell. 2015, 228, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Duan, P. A Reinforcement Learning Approach for Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem with Crane Transportation and Setup Times. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 5695–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.S.; Li, J.Q.; Song, H.N.; Gao, K.Z.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.K.; Zheng, Z.X. Solving the permutation flow shop scheduling problem with sequence-dependent setup time via iterative greedy algorithm and imitation learning. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 234, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, J.; Zhou, Y. Genetic programming hyper-heuristic-based solution for dynamic energy-efficient scheduling of hybrid flow shop scheduling with machine breakdowns and random job arrivals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, J. Tri-objective lot-streaming scheduling optimization for hybrid flow shops with uncertainties in machine breakdowns and job arrivals using an enhanced genetic programming hyper-heuristic. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 172, 106817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Y.; Gao, K.; Xiao, X.; Duan, P. Bi-population balancing multi-objective algorithm for fuzzy flexible job shop with energy and transportation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 4686–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Xu, Y. HGNP: A PCA-based heterogeneous graph neural network for a family distributed flexible job shop. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 200, 110855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ibáñez, M.; Paquete, L.; Stützle, T. Exploratory analysis of stochastic local search algorithms in biobjective optimization. In Experimental Methods for the Analysis of Optimization Algorithms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Duan, P.; Du, Y.; Ning, C. An adaptive collaborative optimization algorithm for hybrid flow shop with group setup times and consistent sublots. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 150, 116354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Duan, P.; Li, J. Uncertain Interruptibility Multiobjective Flexible Job Shop via Deep Reinforcement Learning Based on Heterogeneous Graph Self-Attention. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 18598–18612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candan, G.; Yazgan, H. Genetic algorithm parameter optimisation using Taguchi method for a flexible manufacturing system scheduling problem. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factory | Stage | Machine | Resource Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R3 | |||

| 1 | 1 | M1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | M2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | M3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | M4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2 | M5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | M6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1 | M1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | M2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1 | M3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | M4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | M5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | M6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Stage | Job | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J1 | J2 | J3 | J4 | J5 | J6 | J7 | J8 | J9 | J10 | |

| 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| Parameter | Factor Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| pc | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| pm | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Order | pc | pm | Ave_HV |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.42 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.46 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 0.47 |

| 4 | 1 | 4 | 0.46 |

| 5 | 1 | 5 | 0.44 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 |

| 7 | 2 | 2 | 0.49 |

| 8 | 2 | 3 | 0.58 |

| 9 | 2 | 4 | 0.53 |

| 10 | 2 | 5 | 0.43 |

| 11 | 3 | 1 | 0.56 |

| 12 | 3 | 2 | 0.42 |

| 13 | 3 | 3 | 0.44 |

| 14 | 3 | 4 | 0.50 |

| 15 | 3 | 5 | 0.43 |

| 16 | 4 | 1 | 0.46 |

| 17 | 4 | 2 | 0.42 |

| 18 | 4 | 3 | 0.46 |

| 19 | 4 | 4 | 0.47 |

| 20 | 4 | 5 | 0.46 |

| 21 | 5 | 1 | 0.44 |

| 22 | 5 | 2 | 0.50 |

| 23 | 5 | 3 | 0.49 |

| 24 | 5 | 4 | 0.58 |

| 25 | 5 | 5 | 0.53 |

| Inst | Best | HV Values | RPI Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNMOEA | E1 | E2 | E3 | BNMOEA | E1 | E2 | E3 | ||

| 20 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.7014 | 0.7014 | 0.6978 | 0.6961 | 0.6202 | 0.0000 | −0.0051 | −0.0076 | −0.1158 |

| 20 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6787 | 0.6787 | 0.6532 | 0.6453 | 0.5960 | 0.0000 | −0.0376 | −0.0492 | −0.1219 |

| 20 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6712 | 0.6712 | 0.6624 | 0.6667 | 0.6016 | 0.0000 | −0.0131 | −0.0067 | −0.1037 |

| 20 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6814 | 0.6814 | 0.6748 | 0.6726 | 0.6271 | 0.0000 | −0.0097 | −0.0129 | −0.0797 |

| 20 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6804 | 0.6804 | 0.6419 | 0.6445 | 0.5356 | 0.0000 | −0.0566 | −0.0528 | −0.2128 |

| 20 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6625 | 0.6625 | 0.6451 | 0.6460 | 0.6109 | 0.0000 | −0.0263 | −0.0249 | −0.0779 |

| 20 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6910 | 0.6910 | 0.6799 | 0.6781 | 0.5375 | 0.0000 | −0.0161 | −0.0187 | −0.2221 |

| 20 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6984 | 0.6984 | 0.6282 | 0.6745 | 0.5860 | 0.0000 | −0.1005 | −0.0342 | −0.1609 |

| 20 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6703 | 0.6703 | 0.6516 | 0.6528 | 0.6290 | 0.0000 | −0.0279 | −0.0261 | −0.0616 |

| 60 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6680 | 0.6680 | 0.6555 | 0.6242 | 0.6305 | 0.0000 | −0.0187 | −0.0656 | −0.0561 |

| 60 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6361 | 0.6361 | 0.6284 | 0.5739 | 0.5742 | 0.0000 | −0.0121 | −0.0978 | −0.0973 |

| 60 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6768 | 0.6768 | 0.6704 | 0.6352 | 0.6452 | 0.0000 | −0.0095 | −0.0615 | −0.0467 |

| 60 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6622 | 0.6622 | 0.6532 | 0.6106 | 0.6150 | 0.0000 | −0.0136 | −0.0779 | −0.0713 |

| 60 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6628 | 0.6628 | 0.6486 | 0.6257 | 0.6251 | 0.0000 | −0.0214 | −0.0560 | −0.0569 |

| 60 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6688 | 0.6688 | 0.6538 | 0.6150 | 0.6123 | 0.0000 | −0.0224 | −0.0804 | −0.0845 |

| 60 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6637 | 0.6637 | 0.6422 | 0.5931 | 0.5949 | 0.0000 | −0.0324 | −0.1064 | −0.1037 |

| 60 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6726 | 0.6726 | 0.6516 | 0.6291 | 0.6287 | 0.0000 | −0.0312 | −0.0647 | −0.0653 |

| 60 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6756 | 0.6756 | 0.6677 | 0.6227 | 0.6349 | 0.0000 | −0.0117 | −0.0783 | −0.0602 |

| 100 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6693 | 0.6693 | 0.6628 | 0.6159 | 0.6324 | 0.0000 | −0.0097 | −0.0798 | −0.0551 |

| 100 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6544 | 0.6544 | 0.6539 | 0.5966 | 0.6030 | 0.0000 | −0.0008 | −0.0883 | −0.0785 |

| 100 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6675 | 0.6675 | 0.6584 | 0.6146 | 0.6153 | 0.0000 | −0.0136 | −0.0793 | −0.0782 |

| 100 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6885 | 0.6885 | 0.6795 | 0.6408 | 0.6317 | 0.0000 | −0.0131 | −0.0693 | −0.0825 |

| 100 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6616 | 0.6616 | 0.6589 | 0.6173 | 0.6172 | 0.0000 | −0.0041 | −0.0670 | −0.0671 |

| 100 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6752 | 0.6752 | 0.6586 | 0.6303 | 0.6305 | 0.0000 | −0.0246 | −0.0665 | −0.0662 |

| 100 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6580 | 0.6580 | 0.6519 | 0.6009 | 0.6041 | 0.0000 | −0.0093 | −0.0868 | −0.0819 |

| 100 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6706 | 0.6706 | 0.6560 | 0.6176 | 0.6147 | 0.0000 | −0.0218 | −0.0790 | −0.0834 |

| 100 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6563 | 0.6563 | 0.6416 | 0.6079 | 0.5976 | 0.0000 | −0.0224 | −0.0737 | −0.0894 |

| Avg | 0.6712 | 0.6712 | 0.6566 | 0.6314 | 0.6093 | 0.0000 | −0.0217 | −0.0597 | −0.0919 |

| Inst | Best | IGD Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNMOEA | E1 | E2 | E3 | ||

| 20 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.0183 | 0.0183 | 0.0819 | 0.0646 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.0147 | 0.0147 | 0.1729 | 0.3199 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.0101 | 0.0101 | 0.2141 | 0.1652 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.0103 | 0.0103 | 0.1069 | 0.1653 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.1147 | 0.1147 | 0.2504 | 0.1769 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.0147 | 0.0147 | 0.0765 | 0.0907 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.0269 | 0.0269 | 0.1391 | 0.2061 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.0711 | 0.0711 | 0.3292 | 0.3687 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.0367 | 0.0367 | 0.3674 | 0.2548 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.0870 | 0.0870 | 0.2043 | 1.0000 | 0.7915 |

| 60 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.0397 | 0.0397 | 0.4303 | 0.7603 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.0238 | 0.0238 | 0.1687 | 1.0000 | 0.5134 |

| 60 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.0251 | 0.0251 | 0.1554 | 1.0000 | 0.9748 |

| 60 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.0109 | 0.0109 | 0.1325 | 1.0000 | 0.4452 |

| 60 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0788 | 1.0000 | 0.8079 |

| 60 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.0212 | 0.0212 | 0.0493 | 1.0000 | 0.9121 |

| 60 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.0036 | 0.0036 | 0.3392 | 1.0000 | 0.7271 |

| 60 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.0112 | 0.0112 | 0.1511 | 1.0000 | 0.5732 |

| 100 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.0043 | 0.0043 | 0.1935 | 1.0000 | 0.8946 |

| 100 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.0031 | 0.0031 | 0.0608 | 1.0000 | 0.8149 |

| 100 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.1570 | 0.1570 | 0.2476 | 0.8717 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.1061 | 0.1061 | 0.2052 | 1.0000 | 0.8736 |

| 100 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.0160 | 0.0160 | 0.0980 | 0.6622 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.0138 | 0.0138 | 0.2846 | 0.8844 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.0803 | 0.0803 | 0.2263 | 0.9097 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.0125 | 0.0125 | 0.1975 | 0.9981 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.2242 | 0.2242 | 0.2877 | 0.8609 | 1.0000 |

| Avg | 0.0429 | 0.0429 | 0.1944 | 0.6948 | 0.9010 |

| Instance_Scale | HV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNMOEA | AGEMOEAII | BiGE | CMOPSO | NSGAII | |

| 20 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.7036 | 0.6975 | 0.6512 | 0.6425 | 0.6787 |

| 20 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6463 | 0.6183 | 0.5551 | 0.5399 | 0.558 |

| 20 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6784 | 0.6725 | 0.6521 | 0.6379 | 0.6373 |

| 20 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6692 | 0.6642 | 0.5699 | 0.5679 | 0.5739 |

| 20 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6522 | 0.6568 | 0.5331 | 0.5243 | 0.5215 |

| 20 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6513 | 0.6481 | 0.6262 | 0.6195 | 0.6161 |

| 20 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6808 | 0.6703 | 0.5559 | 0.5348 | 0.6425 |

| 20 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.7094 | 0.6682 | 0.6312 | 0.6283 | 0.6345 |

| 20 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6657 | 0.663 | 0.6424 | 0.6326 | 0.6284 |

| 60 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6885 | 0.6804 | 0.6405 | 0.6485 | 0.6373 |

| 60 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6466 | 0.6464 | 0.6088 | 0.6219 | 0.5827 |

| 60 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6965 | 0.688 | 0.6434 | 0.659 | 0.6488 |

| 60 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6852 | 0.6832 | 0.66 | 0.6299 | 0.6455 |

| 60 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6628 | 0.6514 | 0.6319 | 0.6142 | 0.6207 |

| 60 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6613 | 0.6561 | 0.6084 | 0.6054 | 0.6192 |

| 60 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6463 | 0.6303 | 0.5763 | 0.5723 | 0.5747 |

| 60 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6662 | 0.6531 | 0.616 | 0.6126 | 0.6134 |

| 60 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6547 | 0.6552 | 0.6124 | 0.6026 | 0.613 |

| 100 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6543 | 0.6561 | 0.6038 | 0.6111 | 0.6086 |

| 100 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6767 | 0.6695 | 0.6269 | 0.6329 | 0.632 |

| 100 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6611 | 0.6474 | 0.6093 | 0.6317 | 0.6087 |

| 100 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.663 | 0.6512 | 0.6113 | 0.6075 | 0.6117 |

| 100 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.653 | 0.6539 | 0.5984 | 0.611 | 0.6047 |

| 100 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6463 | 0.6366 | 0.6015 | 0.5957 | 0.5889 |

| 100 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6511 | 0.6506 | 0.5957 | 0.6086 | 0.5978 |

| 100 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6555 | 0.646 | 0.6026 | 0.6038 | 0.6055 |

| 100 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6529 | 0.6463 | 0.6273 | 0.6104 | 0.6117 |

| Avg | 0.7036 | 0.6975 | 0.6512 | 0.6425 | 0.6787 |

| Instance_Scale | HV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNMOEA | AGEMOEAII | BiGE | CMOPSO | NSGAII | |

| 20 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6619 | 0.6499 | 0.4988 | 0.4970 | 0.5035 |

| 20 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.5655 | 0.5493 | 0.3684 | 0.3712 | 0.3892 |

| 20 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6497 | 0.6384 | 0.5200 | 0.5086 | 0.5128 |

| 20 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6097 | 0.5754 | 0.3549 | 0.3927 | 0.4113 |

| 20 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.5474 | 0.5403 | 0.3605 | 0.3615 | 0.3664 |

| 20 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6319 | 0.6227 | 0.5143 | 0.5065 | 0.5124 |

| 20 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6310 | 0.5587 | 0.3564 | 0.4474 | 0.3703 |

| 20 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6456 | 0.6419 | 0.5112 | 0.5201 | 0.5407 |

| 20 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6477 | 0.6393 | 0.5311 | 0.5076 | 0.5379 |

| 60 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6622 | 0.6562 | 0.5566 | 0.5646 | 0.5375 |

| 60 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6186 | 0.6074 | 0.4904 | 0.4952 | 0.4894 |

| 60 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6717 | 0.6662 | 0.6020 | 0.6061 | 0.5907 |

| 60 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6677 | 0.6576 | 0.5493 | 0.5570 | 0.5621 |

| 60 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6343 | 0.6294 | 0.5185 | 0.5140 | 0.5066 |

| 60 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6322 | 0.6240 | 0.5244 | 0.5363 | 0.5048 |

| 60 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6165 | 0.6039 | 0.4940 | 0.4669 | 0.4686 |

| 60 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6383 | 0.6283 | 0.5289 | 0.5173 | 0.5286 |

| 60 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6333 | 0.6219 | 0.5279 | 0.5311 | 0.5361 |

| 100 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6385 | 0.6273 | 0.5334 | 0.5371 | 0.5227 |

| 100 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6560 | 0.6472 | 0.5745 | 0.5399 | 0.5717 |

| 100 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6394 | 0.6318 | 0.5628 | 0.5464 | 0.5474 |

| 100 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6391 | 0.6291 | 0.5123 | 0.5552 | 0.5430 |

| 100 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6290 | 0.6165 | 0.5285 | 0.5305 | 0.5420 |

| 100 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6171 | 0.6128 | 0.4936 | 0.5411 | 0.5133 |

| 100 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6255 | 0.6178 | 0.5144 | 0.5262 | 0.4982 |

| 100 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6206 | 0.6159 | 0.5199 | 0.5226 | 0.5202 |

| 100 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6287 | 0.6264 | 0.5417 | 0.5490 | 0.5362 |

| Avg | 0.6318 | 0.6198 | 0.5033 | 0.5092 | 0.5061 |

| Instance_Scale | HV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNMOEA | AGEMOEAII | BiGE | CMOPSO | NSGAII | |

| 20 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6866 | 0.6738 | 0.5614 | 0.5630 | 0.5627 |

| 20 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.5827 | 0.5721 | 0.4522 | 0.4442 | 0.4486 |

| 20 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6631 | 0.6546 | 0.5751 | 0.5641 | 0.5713 |

| 20 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6525 | 0.6161 | 0.4642 | 0.4788 | 0.4708 |

| 20 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.5780 | 0.5537 | 0.4441 | 0.4452 | 0.4377 |

| 20 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6399 | 0.6333 | 0.5514 | 0.5498 | 0.5506 |

| 20 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6623 | 0.6218 | 0.4711 | 0.4887 | 0.4878 |

| 20 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6599 | 0.6539 | 0.5727 | 0.5736 | 0.5841 |

| 20 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6555 | 0.6481 | 0.5640 | 0.5541 | 0.5584 |

| 60 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6747 | 0.6650 | 0.5974 | 0.5983 | 0.5968 |

| 60 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6300 | 0.6220 | 0.5384 | 0.5428 | 0.5397 |

| 60 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6841 | 0.6778 | 0.6219 | 0.6261 | 0.6164 |

| 60 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6754 | 0.6683 | 0.5912 | 0.5945 | 0.5981 |

| 60 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6495 | 0.6410 | 0.5708 | 0.5624 | 0.5634 |

| 60 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6475 | 0.6397 | 0.5700 | 0.5696 | 0.5721 |

| 60 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6259 | 0.6159 | 0.5327 | 0.5250 | 0.5249 |

| 60 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6494 | 0.6403 | 0.5696 | 0.5682 | 0.5704 |

| 60 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6404 | 0.6331 | 0.5645 | 0.5662 | 0.5747 |

| 100 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.6442 | 0.6395 | 0.5666 | 0.5732 | 0.5687 |

| 100 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.6658 | 0.6584 | 0.6022 | 0.5964 | 0.5990 |

| 100 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.6494 | 0.6415 | 0.5823 | 0.5897 | 0.5782 |

| 100 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.6493 | 0.6411 | 0.5679 | 0.5797 | 0.5745 |

| 100 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.6377 | 0.6275 | 0.5616 | 0.5681 | 0.5654 |

| 100 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.6277 | 0.6223 | 0.5554 | 0.5645 | 0.5564 |

| 100 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.6363 | 0.6266 | 0.5526 | 0.5606 | 0.5486 |

| 100 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.6339 | 0.6272 | 0.5557 | 0.5629 | 0.5568 |

| 100 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.6412 | 0.6363 | 0.5755 | 0.5762 | 0.5746 |

| Avg | 0.6460 | 0.6352 | 0.5531 | 0.5550 | 0.5537 |

| Instance_Scale | IGD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNMOEA | AGEMOEAII | BiGE | CMOPSO | NSGAII | |

| 20 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.0130 | 0.0354 | 0.4317 | 0.3924 | 0.1645 |

| 20 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.0001 | 0.0786 | 0.4639 | 0.5245 | 0.4250 |

| 20 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.0388 | 0.0782 | 0.4351 | 0.3844 | 0.3751 |

| 20 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.0459 | 0.0373 | 0.4755 | 0.4481 | 0.5390 |

| 20 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.0020 | 0.0023 | 0.5398 | 0.4919 | 0.2546 |

| 20 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.0155 | 0.0653 | 0.3309 | 0.3481 | 0.3720 |

| 20 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.0251 | 0.0571 | 0.2961 | 0.4959 | 0.2452 |

| 20 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.0322 | 0.0510 | 0.4906 | 0.4877 | 0.4320 |

| 20 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.0345 | 0.0864 | 0.2351 | 0.3625 | 0.4070 |

| 60 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.0160 | 0.0452 | 0.3761 | 0.6159 | 0.4611 |

| 60 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.0016 | 0.0018 | 0.4273 | 0.3450 | 0.4978 |

| 60 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.0276 | 0.0384 | 0.3533 | 0.3733 | 0.4963 |

| 60 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.0297 | 0.0558 | 0.2188 | 0.2648 | 0.3809 |

| 60 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.0565 | 0.0928 | 0.3092 | 0.5152 | 0.5003 |

| 60 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.0142 | 0.0499 | 0.5475 | 0.4919 | 0.5647 |

| 60 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.0001 | 0.0517 | 0.4194 | 0.4862 | 0.5095 |

| 60 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.0505 | 0.0785 | 0.5340 | 0.5123 | 0.5517 |

| 60 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.0379 | 0.0491 | 0.4029 | 0.5043 | 0.3905 |

| 100 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.0280 | 0.0267 | 0.4489 | 0.5738 | 0.6166 |

| 100 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.0047 | 0.0442 | 0.5130 | 0.5247 | 0.5381 |

| 100 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.0190 | 0.0223 | 0.4932 | 0.1898 | 0.4804 |

| 100 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.0243 | 0.0254 | 0.5765 | 0.3019 | 0.4021 |

| 100 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.0381 | 0.0272 | 0.5053 | 0.3628 | 0.5284 |

| 100 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.0001 | 0.1471 | 0.4093 | 0.3978 | 0.6482 |

| 100 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.0272 | 0.0719 | 0.3729 | 0.4022 | 0.4823 |

| 100 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.0090 | 0.0071 | 0.5893 | 0.5886 | 0.4820 |

| 100 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.0656 | 0.0898 | 0.2630 | 0.3435 | 0.4936 |

| Avg | 0.0243 | 0.0525 | 0.4244 | 0.4344 | 0.4533 |

| Instance_Scale | IGD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNMOEA | AGEMOEAII | BiGE | CMOPSO | NSGAII | |

| 20 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.1759 | 0.3616 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.3386 | 0.6134 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.2769 | 0.5081 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.2222 | 0.3363 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.4439 | 0.5420 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.2114 | 0.4592 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.1243 | 0.3091 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.2950 | 0.3945 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 20 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.2263 | 0.4334 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.2149 | 0.3834 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.2928 | 0.3609 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.2983 | 0.3664 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.1967 | 0.3090 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.2188 | 0.3648 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.2326 | 0.2863 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.3031 | 0.4003 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.2738 | 0.5292 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 60 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.2454 | 0.3816 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.1913 | 0.3105 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.2463 | 0.4595 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.3210 | 0.3288 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.1780 | 0.4326 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.3072 | 0.4415 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.3761 | 0.4185 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.2072 | 0.2988 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.2984 | 0.3110 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 100 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.2666 | 0.2534 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Avg | 0.2586 | 0.3924 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Instance_Scale | IGD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNMOEA | AGEMOEAII | BiGE | CMOPSO | NSGAII | |

| 20 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.0745 | 0.1301 | 0.8642 | 0.8562 | 0.8523 |

| 20 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.2231 | 0.2940 | 0.8570 | 0.8455 | 0.8411 |

| 20 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.1320 | 0.1851 | 0.7946 | 0.8554 | 0.8127 |

| 20 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.1149 | 0.1637 | 0.8399 | 0.8459 | 0.8734 |

| 20 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.1593 | 0.2353 | 0.8558 | 0.8581 | 0.8274 |

| 20 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.1151 | 0.1755 | 0.7843 | 0.7924 | 0.8175 |

| 20 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.0709 | 0.1632 | 0.8496 | 0.7977 | 0.7973 |

| 20 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.1333 | 0.1952 | 0.9161 | 0.8692 | 0.8136 |

| 20 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.1211 | 0.1699 | 0.7734 | 0.8507 | 0.8424 |

| 60 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.1004 | 0.1826 | 0.8645 | 0.8368 | 0.8749 |

| 60 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.1728 | 0.2296 | 0.8907 | 0.8512 | 0.8451 |

| 60 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.1260 | 0.1738 | 0.8150 | 0.8093 | 0.8818 |

| 60 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.1291 | 0.1668 | 0.8947 | 0.8392 | 0.8280 |

| 60 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.1232 | 0.1728 | 0.8000 | 0.8638 | 0.8648 |

| 60 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.0993 | 0.1761 | 0.8415 | 0.8743 | 0.8445 |

| 60 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.1455 | 0.2115 | 0.8481 | 0.8638 | 0.8701 |

| 60 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.1398 | 0.2167 | 0.8589 | 0.8529 | 0.8684 |

| 60 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.1220 | 0.1785 | 0.8321 | 0.8736 | 0.8291 |

| 100 × 2 × 2 × 3 | 0.0981 | 0.1438 | 0.8641 | 0.8337 | 0.8828 |

| 100 × 2 × 3 × 4 | 0.1064 | 0.2117 | 0.8412 | 0.8607 | 0.8739 |

| 100 × 2 × 4 × 5 | 0.1254 | 0.2178 | 0.8666 | 0.7405 | 0.9047 |

| 100 × 3 × 2 × 4 | 0.0802 | 0.1647 | 0.8841 | 0.8043 | 0.8777 |

| 100 × 3 × 3 × 5 | 0.1412 | 0.2171 | 0.8971 | 0.7679 | 0.8374 |

| 100 × 3 × 4 × 3 | 0.2127 | 0.2847 | 0.8467 | 0.7995 | 0.8775 |

| 100 × 4 × 2 × 5 | 0.1109 | 0.1653 | 0.8375 | 0.7845 | 0.8739 |

| 100 × 4 × 3 × 3 | 0.1253 | 0.1691 | 0.8895 | 0.8221 | 0.8362 |

| 100 × 4 × 4 × 4 | 0.1456 | 0.1733 | 0.8159 | 0.8183 | 0.8472 |

| Avg | 0.1277 | 0.1914 | 0.8490 | 0.8321 | 0.8517 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Lin, S.; Li, J. Block–Neighborhood-Based Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm for Distributed Resource-Constrained Hybrid Flow Shop with Machine Breakdown. Machines 2025, 13, 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121115

Xu Y, Lin S, Li J. Block–Neighborhood-Based Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm for Distributed Resource-Constrained Hybrid Flow Shop with Machine Breakdown. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121115

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ying, Shulan Lin, and Junqing Li. 2025. "Block–Neighborhood-Based Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm for Distributed Resource-Constrained Hybrid Flow Shop with Machine Breakdown" Machines 13, no. 12: 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121115

APA StyleXu, Y., Lin, S., & Li, J. (2025). Block–Neighborhood-Based Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm for Distributed Resource-Constrained Hybrid Flow Shop with Machine Breakdown. Machines, 13(12), 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121115