1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have become the cornerstone of modern portable energy storage, powering everything from portable electronics [

1] to mobile devices, electric vehicles and large-scale energy storage systems as they have an unmatchable combination of high energy density (measuring at 120–220 Wh kg

−1) [

2,

3,

4] and power density, besides having environmentally benign features, a wide operating temperature range, low self-discharge rate, no memory effect, high efficiency, and long cycle life [

5]. Due to their versatility and reliability, LIBs are extensively utilized across a range of environments, enduring both extremely hot and cold temperatures.

Many studies have examined and investigated how low temperatures affect LIBs, with the results showing very poor performance under cold temperatures, mostly described as below 0 °C. Under cold temperatures, LIBs have a low discharge capacity. As shown in previous studies, LIBs lose most energy and capacity as the temperature reaches below −10 °C [

6]. Zhang et al. [

7] showed that graphite only retains 12% of its normal room temperature capacity at −20 °C. Three main factors cause this lack of performance: (1) low charge-transfer rate; (2) low solid diffusivity of lithium-ion in the electrode and (3) reduced ionic conductivity in the electrolyte [

8,

9,

10]. In addition to these established limitations, recent studies show that low-temperature performance loss in lithium-ion batteries results from several physical and chemical effects. One major factor is the increase in SEI resistance, which leads to higher overpotentials at low temperatures and makes Li

+ transport across the interface much more difficult [

11]. Other work has shown that cooling causes the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) and Cathode Electrolyte Interphase (CEI) layers to become more resistive, which encourages lithium plating and dendrite formation during charging, leading to permanent capacity loss and safety concerns [

12]. Additional research also points to slower reaction kinetics at the electrode surfaces as the electrolyte becomes more viscous or begins to freeze [

13].

Low-temperature operation reduces both on-load voltage and extractable capacity in lithium-ion cells because total polarization increases as temperature falls. This behavior stems from concurrent increases in ohmic, interfacial, and mass-transport losses: electrolyte conductivity drops as viscosity rises [

14]; SEI/CEI layers become more resistive [

15]; and charge-transfer kinetics at both electrodes slow markedly at low temperature [

16]. Together, these effects raise internal resistance and produce larger iR and kinetic overpotentials at a given current.

Electrolyte and interphase engineering have therefore focused on reducing transport limitations and interfacial barriers at sub-zero conditions. Recent work demonstrates that low-melting, low-viscosity solvent blends and localized high-concentration electrolytes (LHCEs) with fluorinated diluents and FSI-based salts sustain substantially higher low-temperature capacity by maintaining higher κeff and forming LiF-rich, conductive interphases [

17,

18,

19]. Additives such as LiPO

2F

2 further decrease interfacial overpotentials by stabilizing SEI/CEI and facilitating Li+ desolvation at the anode [

20]. Quantitatively, electrochemical impedance studies report that charge-transfer resistance can increase by factors of two to four between 25 °C and −20 °C depending on chemistry and electrode design, while effective ionic transport across porous electrodes degrades as

,

, and

fall with temperature [

21,

22].

A second, safety-critical constraint is lithium plating during cold charging. Elevated polarization drives the graphite potential toward 0 V vs. Li/Li+, impeding intercalation and promoting metallic Li deposition. Plating consumes cyclable lithium and can evolve into mossy or dendritic morphologies, in severe cases risking internal short circuits [

23,

24]. These mechanistic limits collectively explain the characteristic losses in power, capacity, and charge acceptance under sub-zero operation.

Crucially, cell geometry and electrode architecture modulate the severity of these low-temperature penalties. For a fixed C-rate, larger absolute current and higher areal loading/thicker electrodes increase local current density and diffusion path length, raising

and

as

,

, and

all fall with temperature [

25]. Electrode porosity and tortuosity (

), particle size, separator properties, and current-collector/tab design further determine κeff, distribution of current, and heat generation. Recent analyses emphasize that cell format (e.g., 18650/26650) and internal design (tab placement, “tabless” architectures) can substantially alter low-temperature performance by redistributing current and shortening effective transport [

26,

27]. Consequently, format-dependent differences at sub-zero temperatures cannot be attributed to chemistry alone; they emerge from the interaction between chemistry, areal loading/thickness, pore structure, and current-collection geometry.

Diagnostics have also evolved to better resolve cold-temperature behavior. Beyond capacity–voltage curves, incremental capacity analysis (ICA), differential voltage analysis (DVA), and EIS provide feature-level insight into kinetic and transport limitations. However, under deep-cold, ICA signals are noisy and peaks broaden/split due to heterogeneous kinetics, making signal processing a nontrivial source of bias. Recent studies review ICA/DVA best practices and filtering strategies, but few explicitly tailor denoising to sub-zero conditions where over-smoothing can obscure diagnostic peaks [

28,

29].

Given the limitations inflicted by cold temperatures, this research aims to address a gap in the literature and investigate how different chemistries and sizes of LIBs are affected by cold temperatures without the interference of any warming-up methodologies.

This comparison helps highlight which cell formats and chemistries are naturally better suited for low-temperature operation, with larger formats and chemistries exhibiting lower resistance growth emerging as more promising candidates.

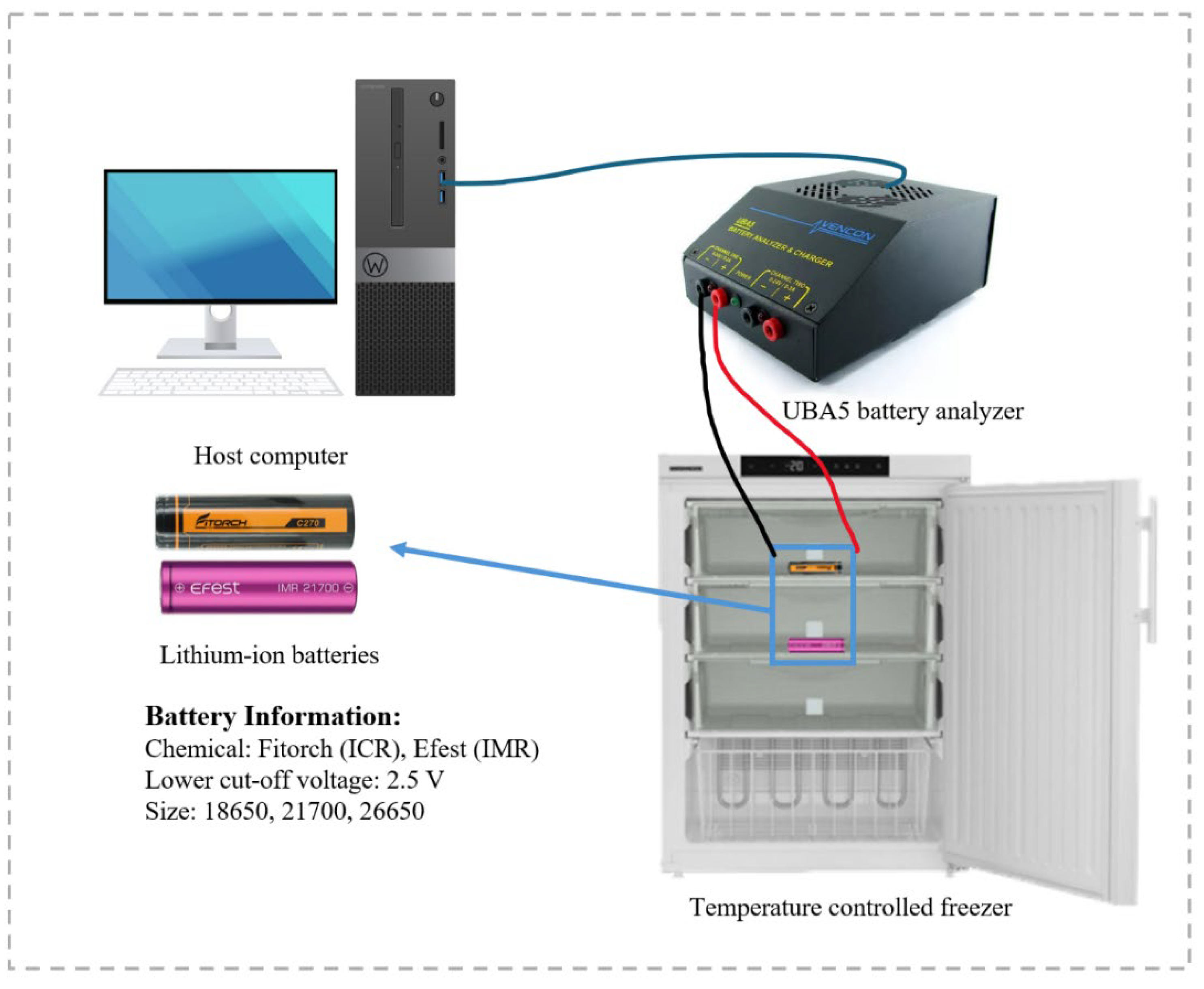

Our study seeks to address this gap by comparing the performance of three different battery sizes (18650, 21700, and 26650). The 18650 battery has a diameter of 18 mm and a length of 65 mm. The 21700 battery, slightly larger, measures 21 mm in diameter and 70 mm in length. The 26650 battery features a diameter of 26 mm and a length of 65 mm. The batteries were sourced from two manufacturers: Efest, utilizing Lithium Manganese Oxide (LiMn2O4) abbreviated as IMR, and Fitorch, utilizing Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LiCoO2) abbreviated as ICR, as their respective cathode chemistries. The selection of the three sizes (18650, 21700, and 26650) was informed by their significant industry relevance, wide-ranging applications, emerging technological trends, and strong market demand. To broaden the scope of our evaluations and enrich the analysis, batteries from two distinct chemistries/manufacturers were utilized. This strategy was intended to amass more comprehensive data, establish a broader base for comparison, and discern whether commonalities exist among different chemistries or if each type exhibits unique characteristics.

By performing controlled charge–discharge cycles at temperatures of +25 °C, −10 °C, −15 °C, −20 °C, −25 °C, and −30 °C, key performance metrics, including internal resistance, coulombic efficiency, discharge voltage profiles, and capacity retention, were examined. The research seeks to improve the understanding of lithium-ion batteries’ response to cold temperatures, taking into account factors such as battery chemistry and size.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as below:

Unified deep sub-zero benchmark: Compared 18650/21700/26650 formats and two commercial chemistries (ICR; IMR) from +25 to −30 °C under identical protocols, quantifying capacity/energy, coulombic efficiency, and internal resistance.

Mechanistic evidence via ICA: Revealed size- and chemistry-dependent peak shifts and fragmentation with decreasing temperature, directly indicating kinetic and interfacial limitations that underpin the observed performance trends.

Methodological contribution: Proposed an adaptive hybrid filtering (AHF) method for low-temperature ICA that uses local skewness, kurtosis, and variance to preserve peaks while suppressing noise.

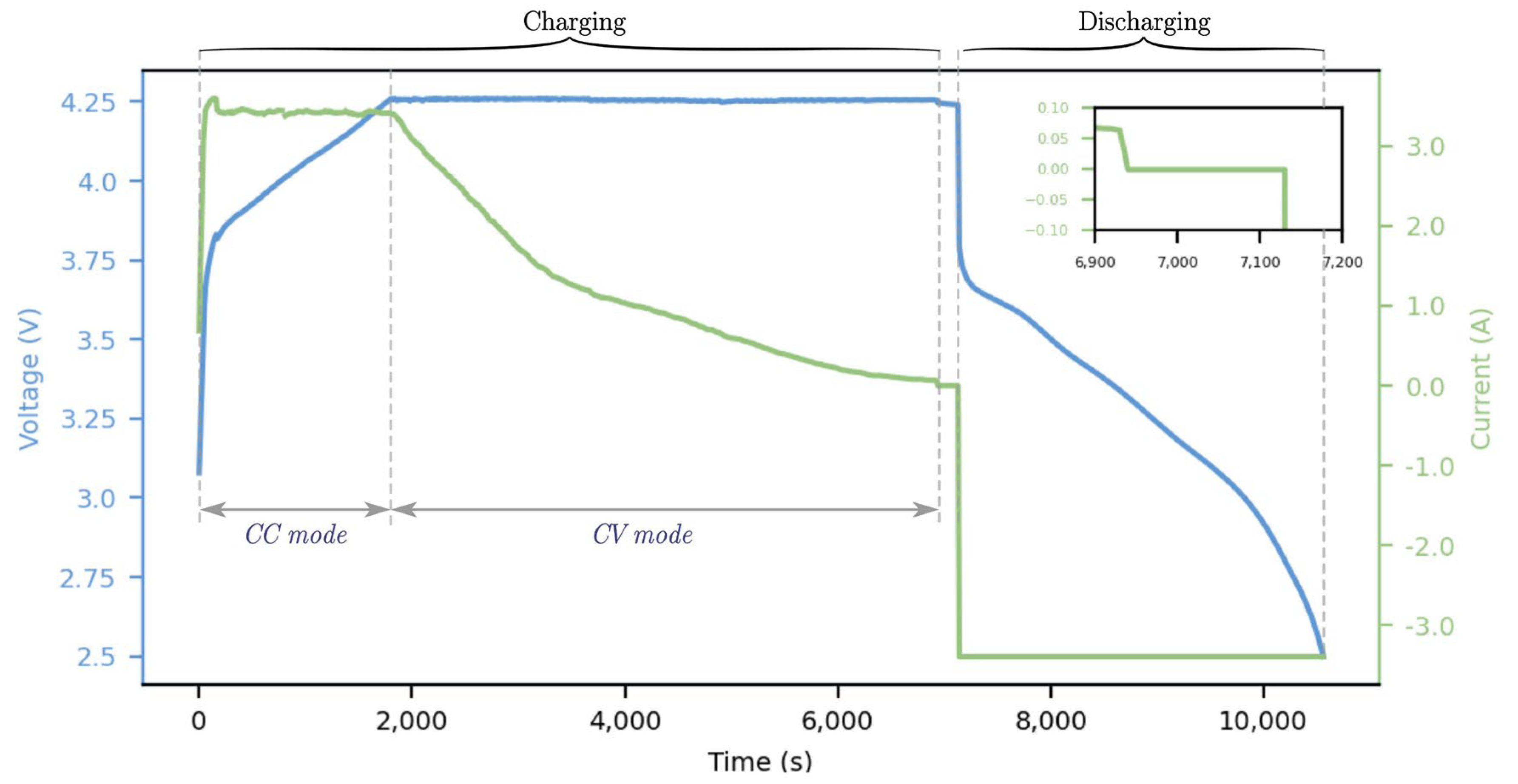

3. Examination of Performance Metrics

To fully grasp the behaviour of LIBs examined in this research, we meticulously evaluated experimental data using a range of performance indicators. We considered metrics such as discharge performance, capacity degradation, internal resistance, coulombic efficiency, and additional pivotal factors influencing battery behaviour.

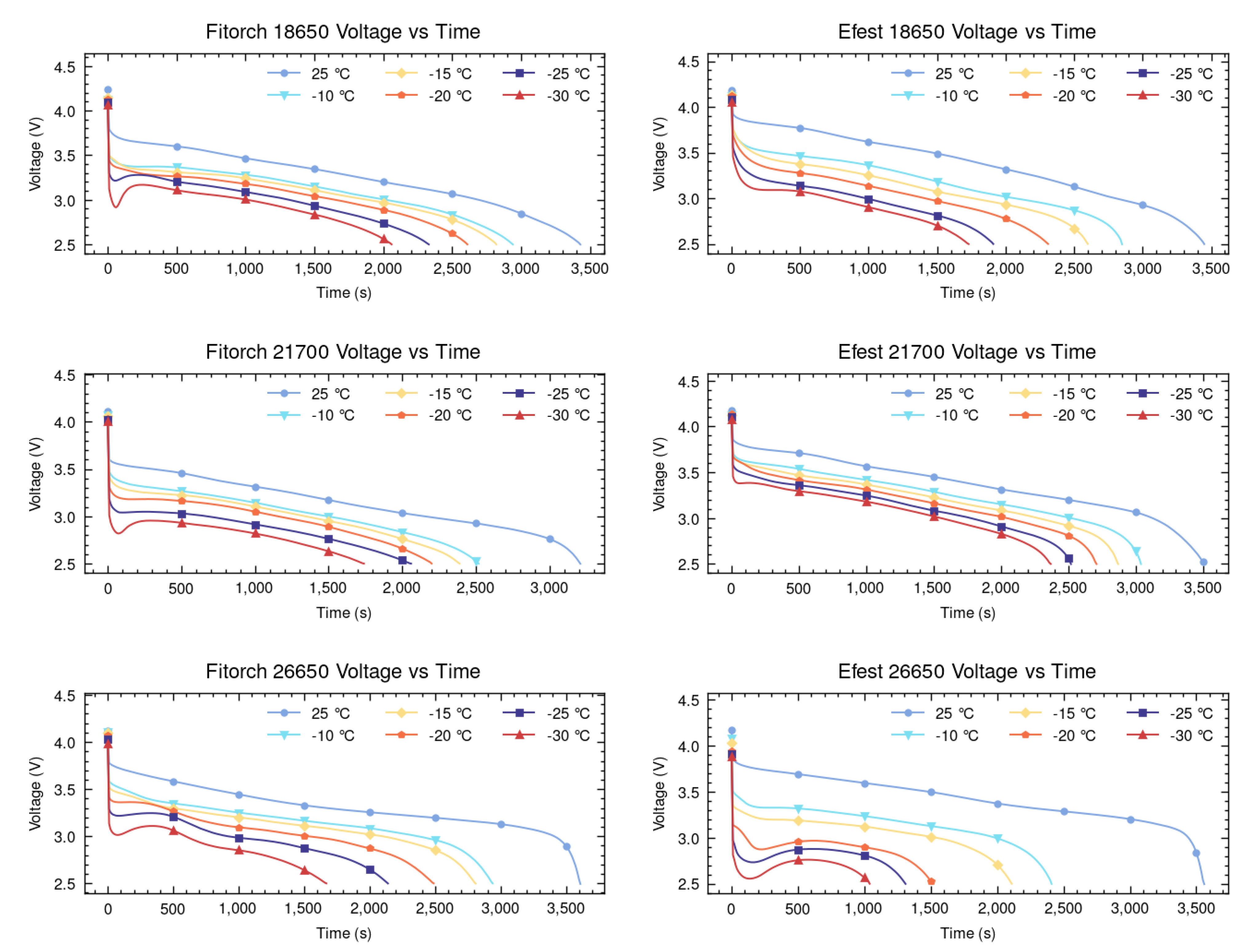

3.1. Discharging Performance

The effects of temperature on the discharging characteristics of LIBs with different sizes (18650, 21700, and 26650) and chemistries (LiCoO

2 and LiMn

2O

4) are presented in

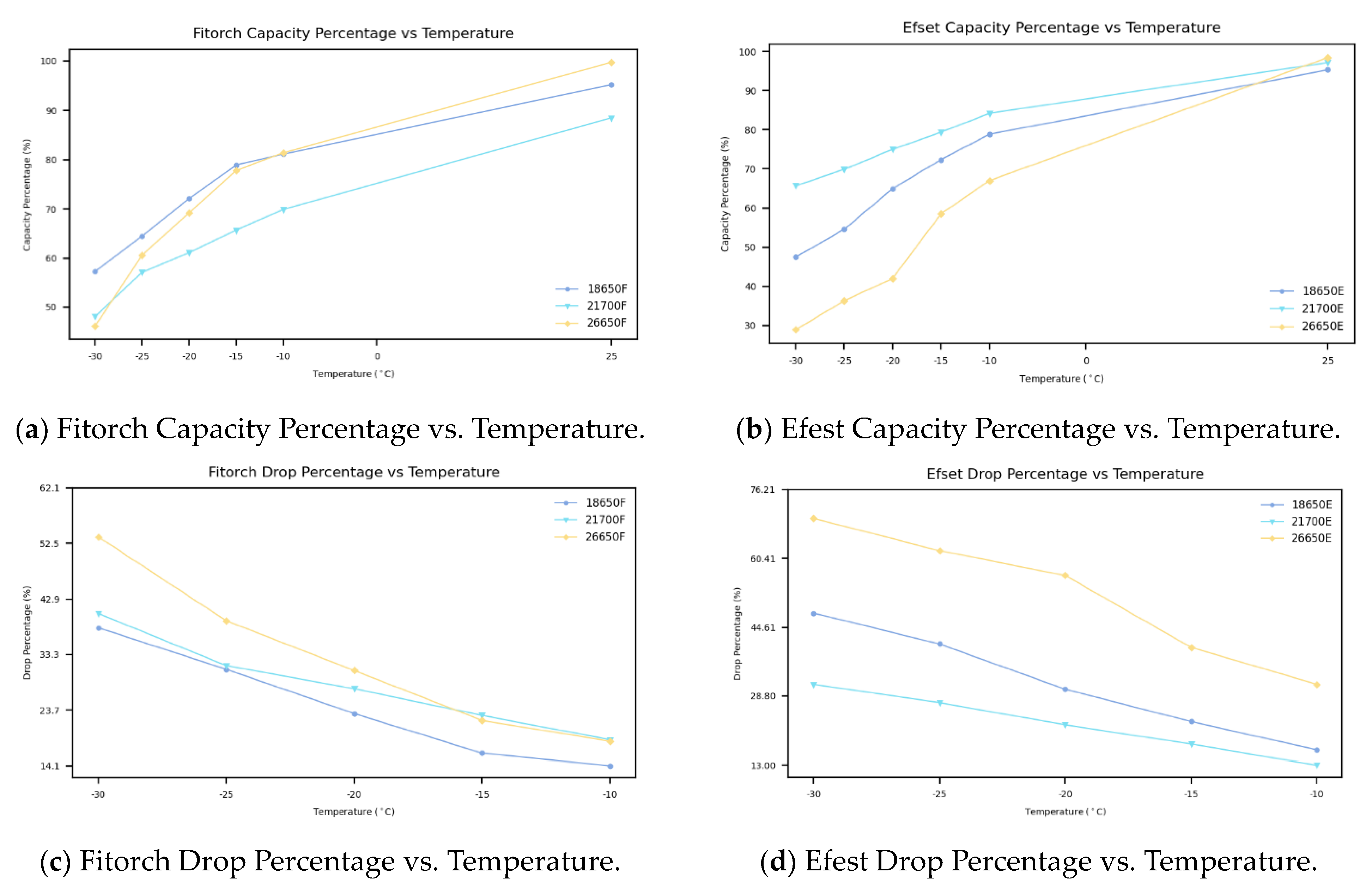

Figure 3. The figure, as well-documented in the literature, illustrates that a decrease in temperature leads to a substantial increase in voltage drop upon discharge, which consequently diminishes the operational voltage range and usable capacity. The 18650 and 21700 batteries show a similar degree of consistency in their performance across the different cold temperatures for both chemistries. Both Fitorch 18650 and Efest 18650 batteries show steady voltage at +25 °C but exhibit sharp performance declines as temperatures drop, particularly at −20 °C and −30 °C, as expected. The 21700 batteries show similar trends to the 18650 batteries but generally retain slightly better performance at lower temperatures for the Efest batteries, while falling behind moderately for the Fitorch batteries. However, both types of 26650 batteries experience the most significant reduction in the voltage range across all temperatures, with the Efest variant nearly reaching failure.

Additional analysis has been conducted to investigate the decrease in capacity between batteries of different sizes and chemical compositions, as presented in

Figure 4. The capacity values were normalized as percentages based on their nominal capacities to facilitate comparison between different batteries. This conversion allows for a more straightforward comparison of capacity drops, irrespective of the varying nominal capacities of the different battery sizes. The capacity drop analysis shows that the 26650 battery experiences the highest capacity drop, with the Fitorch 26650 battery at an average drop of 32.72% and the Efest 26650 battery at an average drop of 51.96%, making it the most affected by colder temperatures. In comparison, the 18650 and 21700 batteries perform better, with a similar capacity drop between them. For the 18650 batteries, the Efest battery shows an average drop of 31.69%, while the Fitorch battery shows an average drop of 24.44%. The Efest 21700 battery exhibits an average drop of 22.36%, while the Fitorch 21700 battery exhibits an average drop of 28.11%. The aforementioned analysis demonstrates that capacity declines vary between chemistries, even among batteries of identical size; this variation suggests that cold temperatures exert distinct impacts on each battery chemistry within the same-size classification.

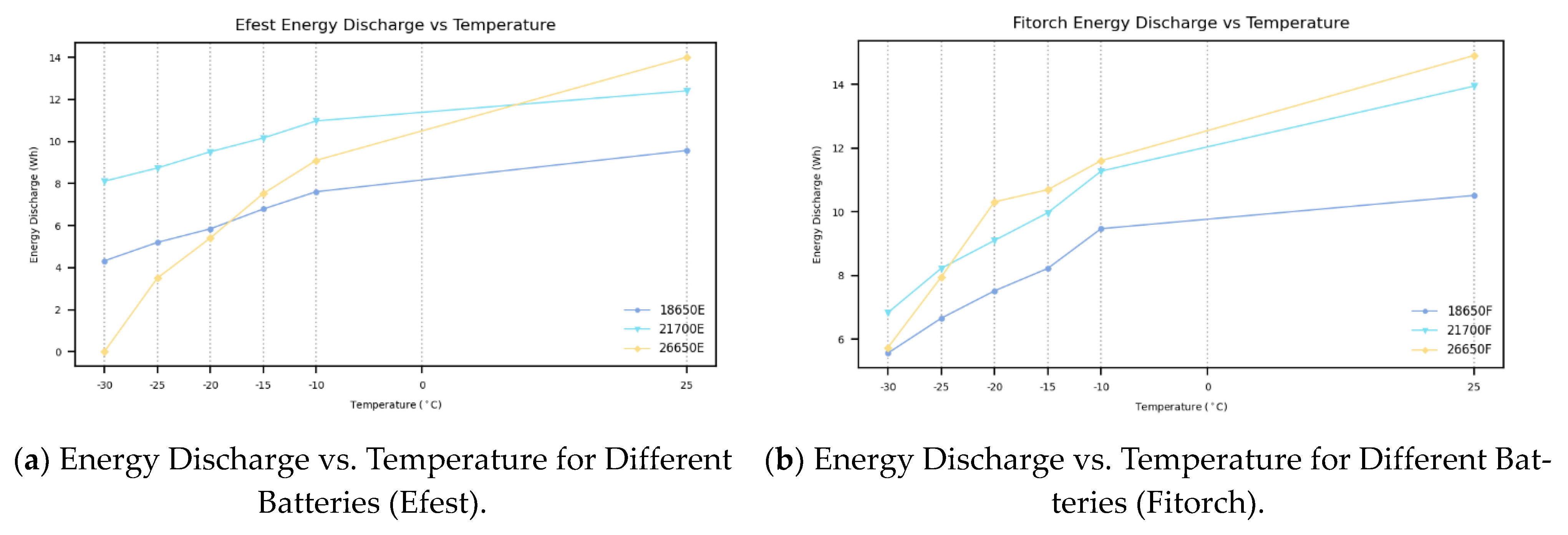

The analysis of energy discharge across various LIB sizes at different temperatures and different chemistries provides additional perspective, yielding several significant insights that bolster our conclusion. As shown in the experimental data in

Figure 5, both battery chemistries have seen a clear decline in energy discharge as the temperature decreases. Among the Efest batteries, the 26650 displays the highest discharge energy at room temperature, yet it demonstrates the poorest consistency at cold temperatures. The 21700 shows the best consistency and discharge energy through the various cold temperatures tested. Most significantly, the 18650 batteries, while relatively stable at lower temperatures, consistently display the lowest energy discharge across all tests. This limited energy discharge capacity highlights a critical limitation, making 18650 batteries less suitable for high-energy applications, such as electric vehicles, portable power tools, and large-scale energy storage systems, where both high discharge energy and resilience to temperature fluctuations are essential.

3.2. Coulombic Efficiency

Another angle to examine a battery’s performance is its coulombic efficiency (CE). CE is the ratio of the total charge extracted from the battery during discharge to the total charge put into the battery over a full cycle [

31]. The CE (

) can be expressed mathematically as:

where:

is the total charge extracted from the battery during discharge.

is the total charge put into the battery during charge.

LIBs exhibit some of the highest CE ratings among rechargeable batteries, generally achieving 99% or higher. In contrast, lead-acid batteries typically attain a CE of approximately 90%, whereas nickel-based batteries demonstrate efficiencies in the vicinity of 80%.

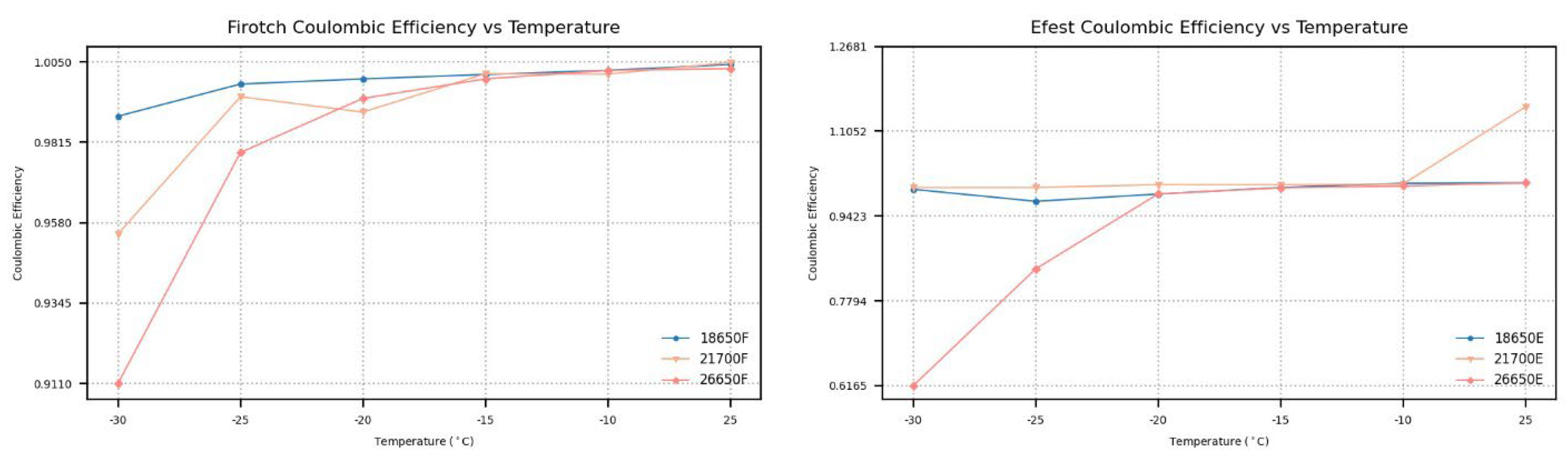

In

Figure 6, the CE at different temperatures is demonstrated, highlighting how temperature affects the battery’s charge–discharge efficiency. The 18650 batteries consistently show near-unit CE throughout the temperature spectrum with minimal fluctuations. Similarly, the 26650 batteries demonstrate efficiencies proximal to unity at ambient temperatures; however, their CE notably diminishes with decreasing temperature. For Fitorch batteries, the CE is reduced to 91%, and for Efest batteries, the CE plummets to 61%, reflecting a substantial degradation in performance at −30 °C (

Figure 6). The 21700 batteries maintain an efficiency close to unity, suggesting resilient performance over diverse temperature ranges. Notably, the CE should not surpass unity, yet a slight margin of error is present, likely attributable to the manual soldering process when affixing the batteries to the wires connected to the UBA5.

3.3. Effect of Temperature on Internal Resistance

Many studies, including those conducted by Łebkowski [

32] and Hande [

33], have demonstrated that lower temperatures significantly impact the internal resistance of Li-ion cells, resulting in their increase. However, this increase in internal resistance varies across different battery sizes and different chemistries. The next comparative analysis shown in

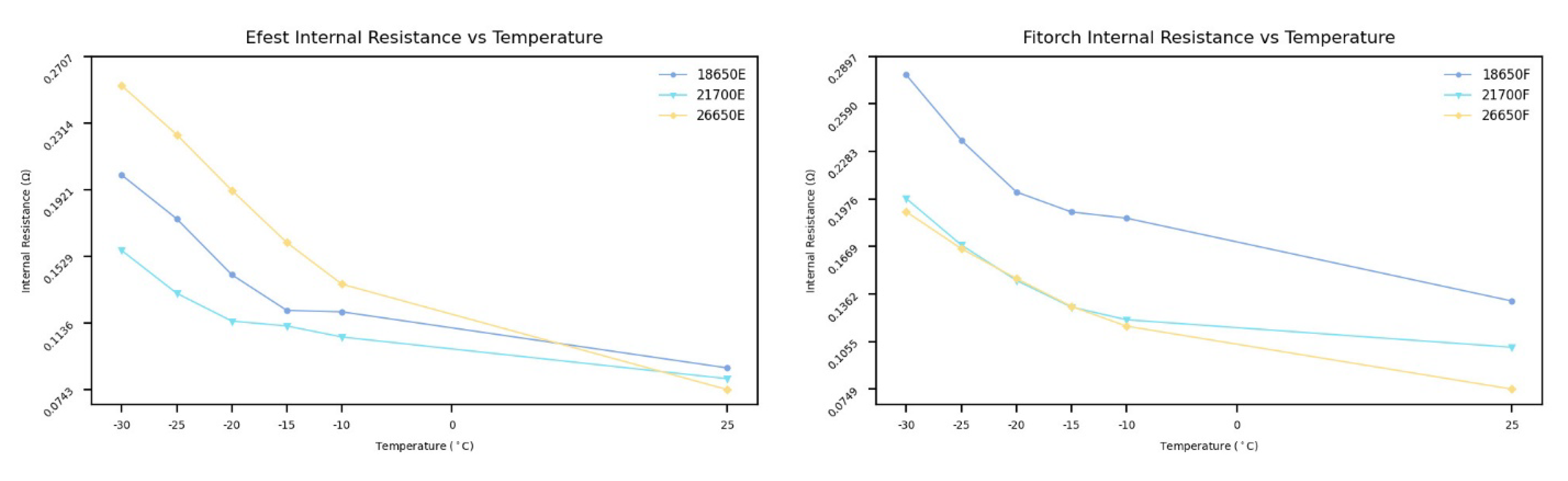

Figure 7, reveals that while all sizes experience an increase in internal resistance at low temperatures, the magnitude of this increase differs among the 18650, 21700, and 26650 batteries.

The examination revealed that Efest 26650 batteries exhibit the highest internal resistance, while Efest 21700 batteries demonstrate the lowest. On the other hand, the Fitorch 18650 batteries exhibit the highest internal resistance, and the Fitorch 26650 batteries exhibit the lowest. These findings underscore the distinct characteristics imparted by different chemistries on various battery sizes. On average, Efest batteries (IMR) displayed lower internal resistances for 18650 and 21700 sizes, with values of 0.117 and 0.141 , respectively. In contrast, Fitorch batteries (ICR) exhibited higher resistances of 0.143 for the 18650 format and 0.204 for the 21700 format. An exception to this pattern was observed in the 26650 batteries, where Fitorch batteries demonstrated a lower average internal resistance (0.137 ) compared with Efest batteries (0.174 ). These findings imply that IMR chemistry batteries generally possess lower internal resistance than those with ICR chemistry.

Quantitatively, the magnitude of the chemistry-driven differences is significant. For the 18650 format, the ICR cell exhibited approximately 22% higher internal resistance compared with the IMR version. For the 21700 size, the difference was even more pronounced, with the ICR cell showing a 44% higher resistance. For the 26650 format, the trend reversed: the IMR cell exhibited a 27% higher resistance than the ICR equivalent, demonstrating that cell geometry and electrode design can outweigh chemistry effects.

Temperature dependence further highlights these differences. Across all tested cells, internal resistance increased markedly as temperature decreased. When cooled from 25 °C to –10 °C, resistance typically increased by 35–50%, and by 80–120% at –20 °C. At –30 °C, the increase exceeded 150% for certain cells, indicating severe kinetic limitations at deep sub-zero temperatures. The Fitorch 21700 cell showed the largest temperature-driven increase, while the Efest 21700 cell exhibited the smallest, underscoring the combined influence of chemistry, electrode structure, and manufacturing design on low-temperature performance.

The differences in internal resistance identified in the previous discussion are consistent with established electrochemical behavior found in the literature. The lower resistance associated with IMR cells aligns with the findings of Thackeray et al. [

34] and Goodenough and Park [

35], who attributed the favorable kinetic performance of LiMn

2O

4 to its three-dimensional spinel structure and inherently lower charge-transfer resistance compared with the layered LiCoO

2 system. The higher resistance trends observed for ICR cells correspond with prior reports of increased polarization and interfacial impedance in LCO-based chemistries. Finally, the influence of cell geometry and electrode design highlighted earlier is strongly supported by Waldmann et al. [

36], who demonstrated that factors such as electrode thickness and diffusion path length can significantly alter internal resistance, sometimes exceeding the effects of chemistry alone.

3.4. Incremental Capacity Analysis

The Incremental Capacity Analysis (ICA) is a powerful diagnostic tool used to evaluate the health and performance of LIBs. Incremental Capacity (IC) quantifies how a battery’s capacity (

) changes in response to small variations in voltage (

), expressed as

. The resulting IC values are plotted against the battery’s voltage (

) to generate what is known as the Incremental Capacity curve. This curve reveals characteristic peaks that correspond to various electrochemical processes within the battery. These characteristic peaks provide valuable insights into the battery’s state of charge, internal resistance, and the presence of any degradation mechanisms [

37]. It is important to note that only discharge IC curves are evaluated in this study.

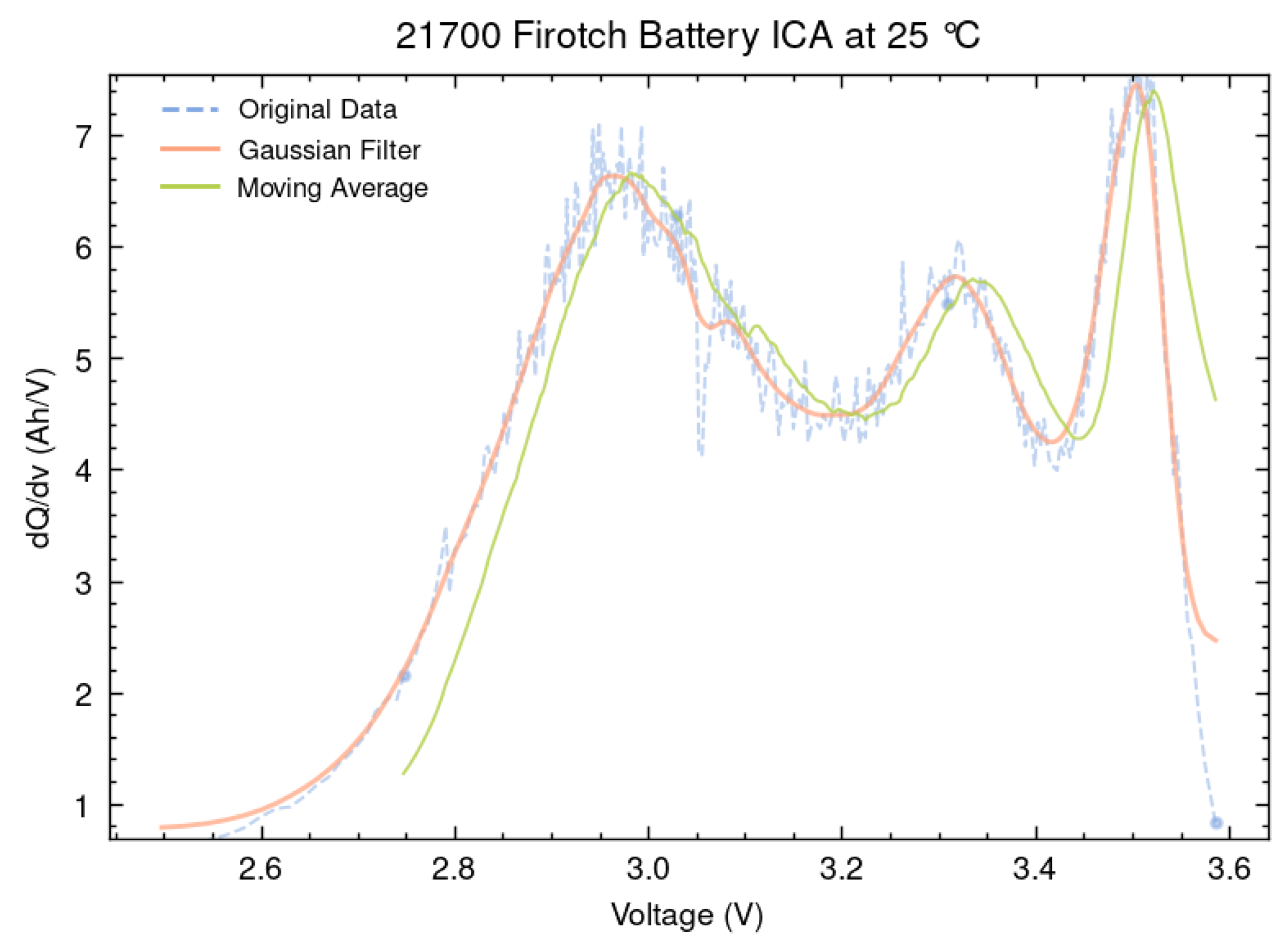

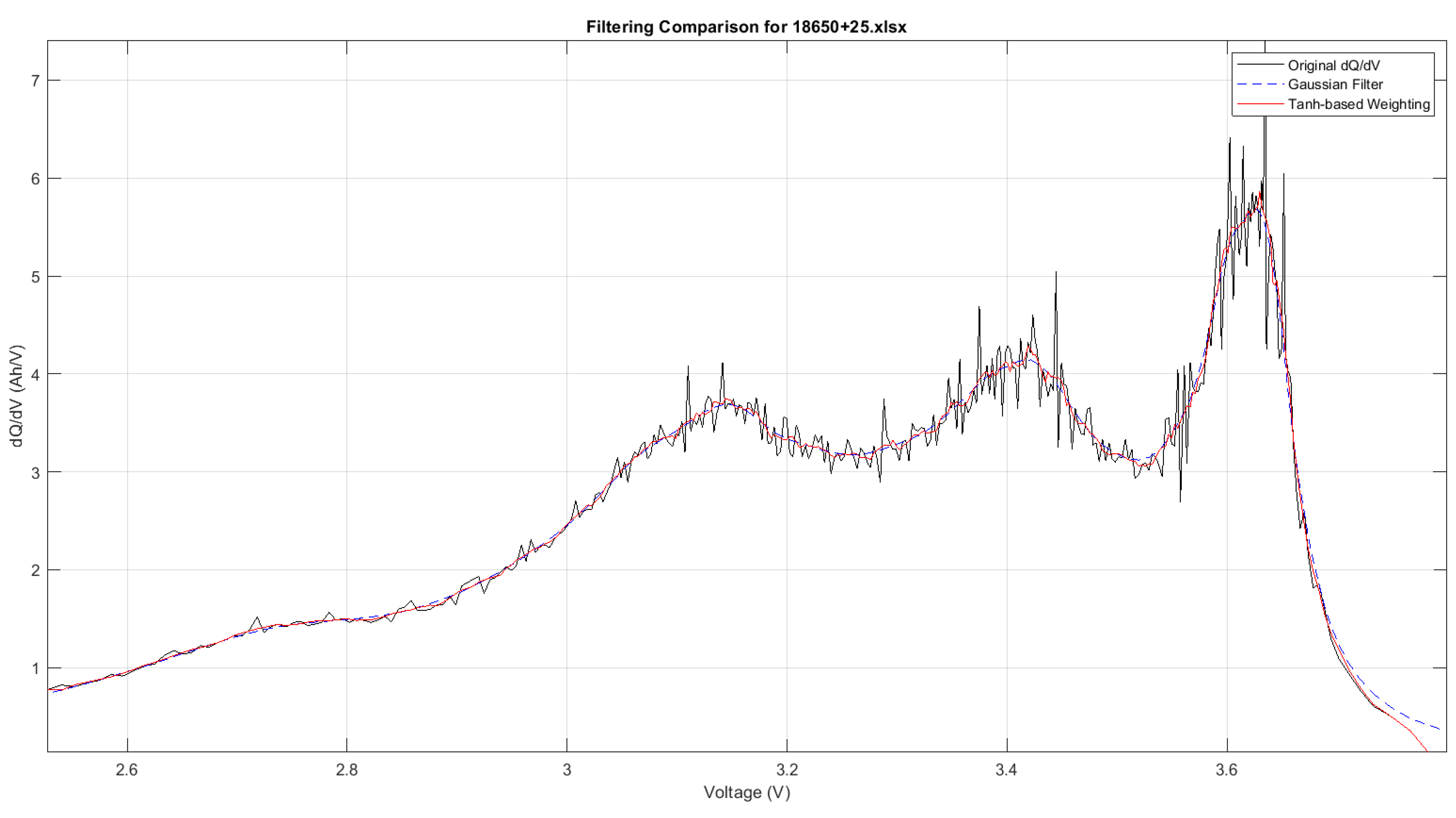

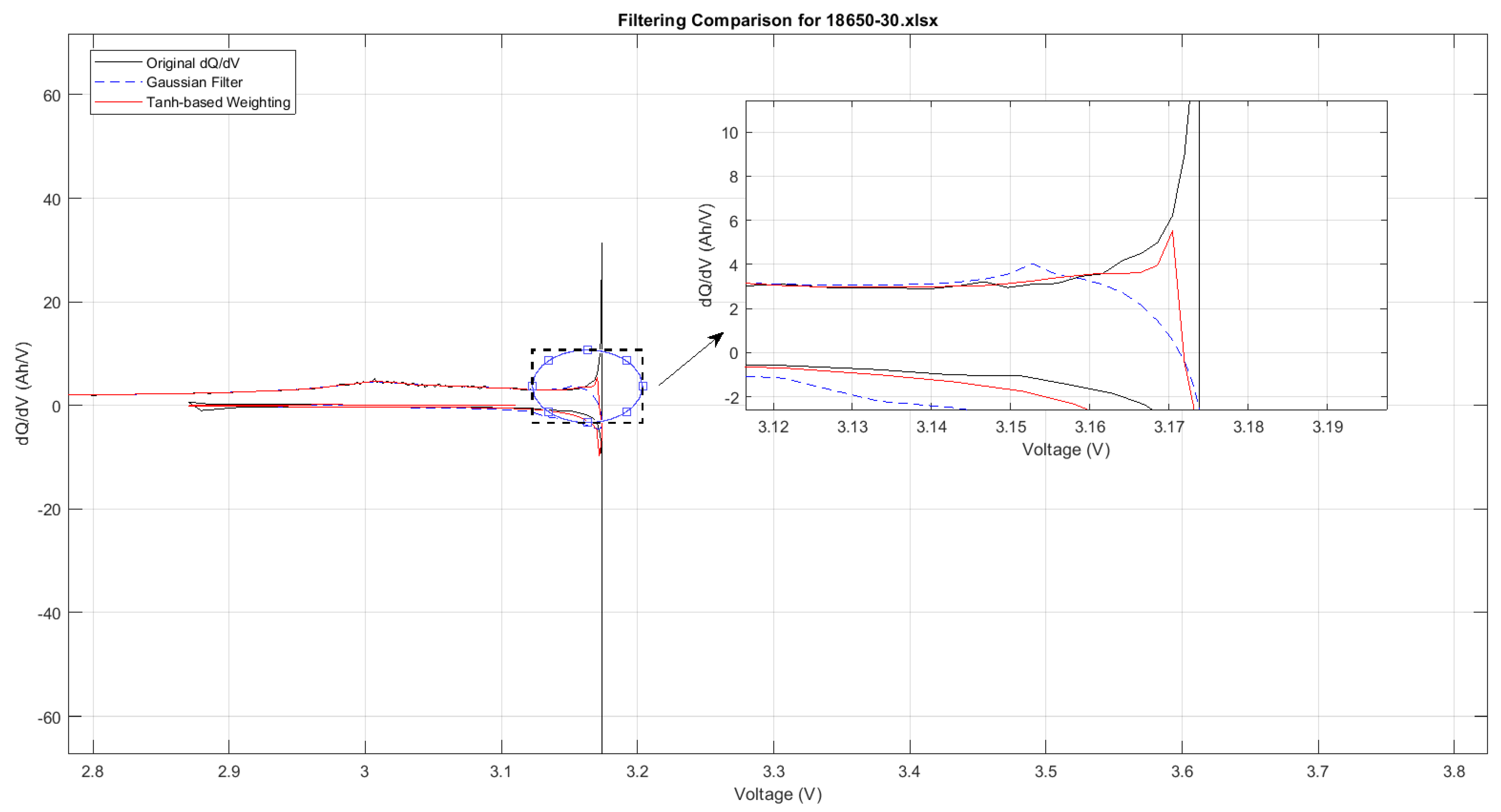

In the ICA of lithium-ion batteries, filtering techniques play a critical role in reducing noise and enhancing the visibility of key diagnostic features such as peak positions and magnitudes. A wide range of filters have been proposed in the literature, including Savitzky–Golay, Weighted Recursive Averaging, and Kalman-based approaches, each offering distinct advantages in preserving signal fidelity or adapting to dynamic data. However, among these, the Moving Average filter and the Gaussian filter remain the most widely adopted due to their consistent performance across various datasets. As shown in

Figure 8, this study focuses specifically on these two filters for ICA signal processing. The Moving Average Filter is renowned for its simplicity and computational efficiency, making it suitable for real-time applications; however, it is less effective at managing outliers. It works by averaging a specified number of neighbouring data points to smooth short-term fluctuations while preserving overall trends.

The Moving Average Filter is mathematically represented as shown in Equation (2):

where

represents the original input data points,

is the filtered output data point,

is the total number of data points in the averaging window (set to 20 in this analysis), and

.

The Gaussian filter applies weights to data points based on a Gaussian distribution, effectively attenuating the influence of outliers and providing a natural smoothing effect. Its behaviour is governed by the Gaussian function, as shown in Equation (3):

where

represents the Gaussian weights,

is the mean (typically set to 0), and

is the standard deviation. The filtered data point

is calculated as the convolution of the original data points

with the Gaussian weights, as expressed in Equation (4):

A comparative analysis of the outcomes derived from the Moving Average filter and the Gaussian filter demonstrates that while both are effective at reducing noise, the Gaussian filter exhibits greater precision. As depicted in

Figure 8, the Gaussian filter closely mirrors the trajectory of the data, whereas the Moving Average filter tends to diverge slightly. Consequently, the Gaussian filter emerges as the more favourable option for detailed ICA comparative analyses where data integrity is critical.

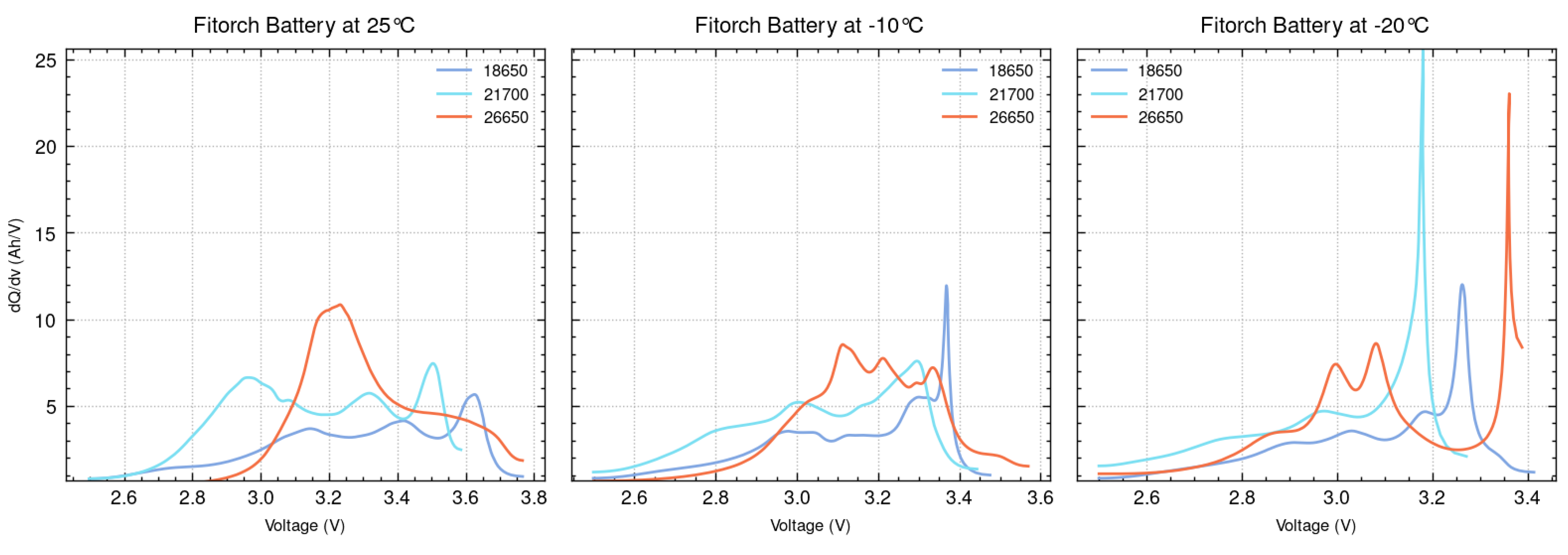

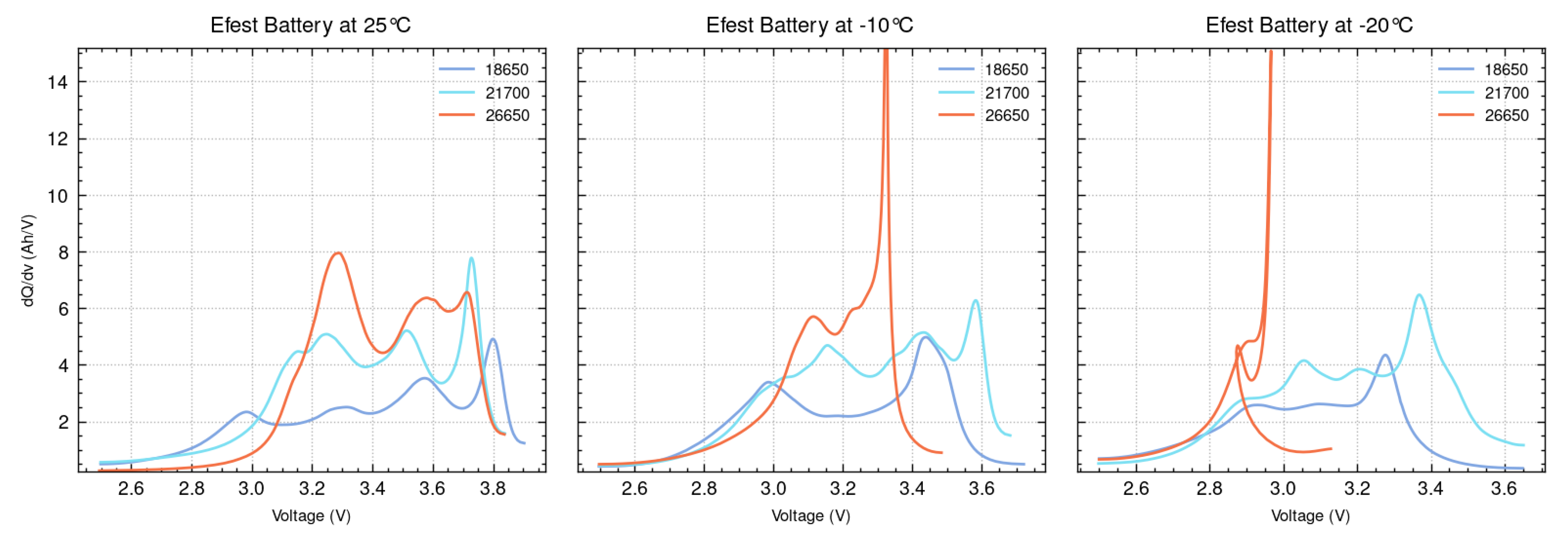

ICA is conducted for the 18650, 21700, and 26650 batteries across various temperatures. To demonstrate the overall trend, results at three representative temperatures (+25 °C, −10 °C, and −20 °C) are selected for detailed analysis and are presented in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. Comparing the ICA plots at these temperatures, all three battery types exhibit noticeable shifts in their peaks, highlighting the influence of temperature on their electrochemical behavior and overall performance. These peak shifts typically occur at lower voltages compared to the +25 °C case, indicating that the voltage at which certain electrochemical processes occur is lower at colder temperatures. This behavior is attributed to the significant impact of lower temperatures on the kinetics of lithium-ion intercalation and de-intercalation, which result in increased internal resistance, slower reaction rates, altered phase transitions, and diminished electrochemical activity.

The pronounced peaks in the ICA graphs for both the 18650 and 21700 batteries from Efest and Fitorch at lower temperatures highlight slower lithium-ion transport and reduced reaction rates, resulting in high and unstable peaks. While the 18650 and 21700 batteries exhibit a decline in performance under colder conditions, their electrochemical behavior is less severely affected compared to the 26650 batteries. At +25 °C, the Fitorch 26650 battery displayed a single, prominent peak around 3.2 volts; however, at −10 °C, this dominant peak fragmented into multiple smaller peaks, indicating that its electrochemical reactions become more distributed and less uniform. Furthermore, the Efest 26650 batteries show the most substantial changes in their overall ICA graph composition across all temperatures, suggesting that they are much more affected by low temperatures. These findings demonstrate that the 26650 battery experiences the greatest disruption in electrochemical processes and elevated internal stress, as evidenced by the ICA.

Despite the superior performance of the Gaussian filter compared to the moving average filter, the Gaussian filter has several disadvantages; for example, it tends to over-smooth critical peaks, thereby obscuring key feature distinctions. To remedy this, in the next section, a novel hybrid filtering technique is introduced that amalgamates the advantages of various approaches to overcome these issues and enhance peak detection fidelity. In ICA, precision in peak detection is imperative for discerning nuanced variations in battery performance, such as changes in internal resistance, degradation patterns, and capacity loss over time. Accurately identified peaks yield vital information regarding the battery’s electrochemical dynamics, thereby facilitating more precise diagnostics, refined SOH evaluations, and the formulation of charging strategies that adeptly correspond to the battery’s current state [

38].

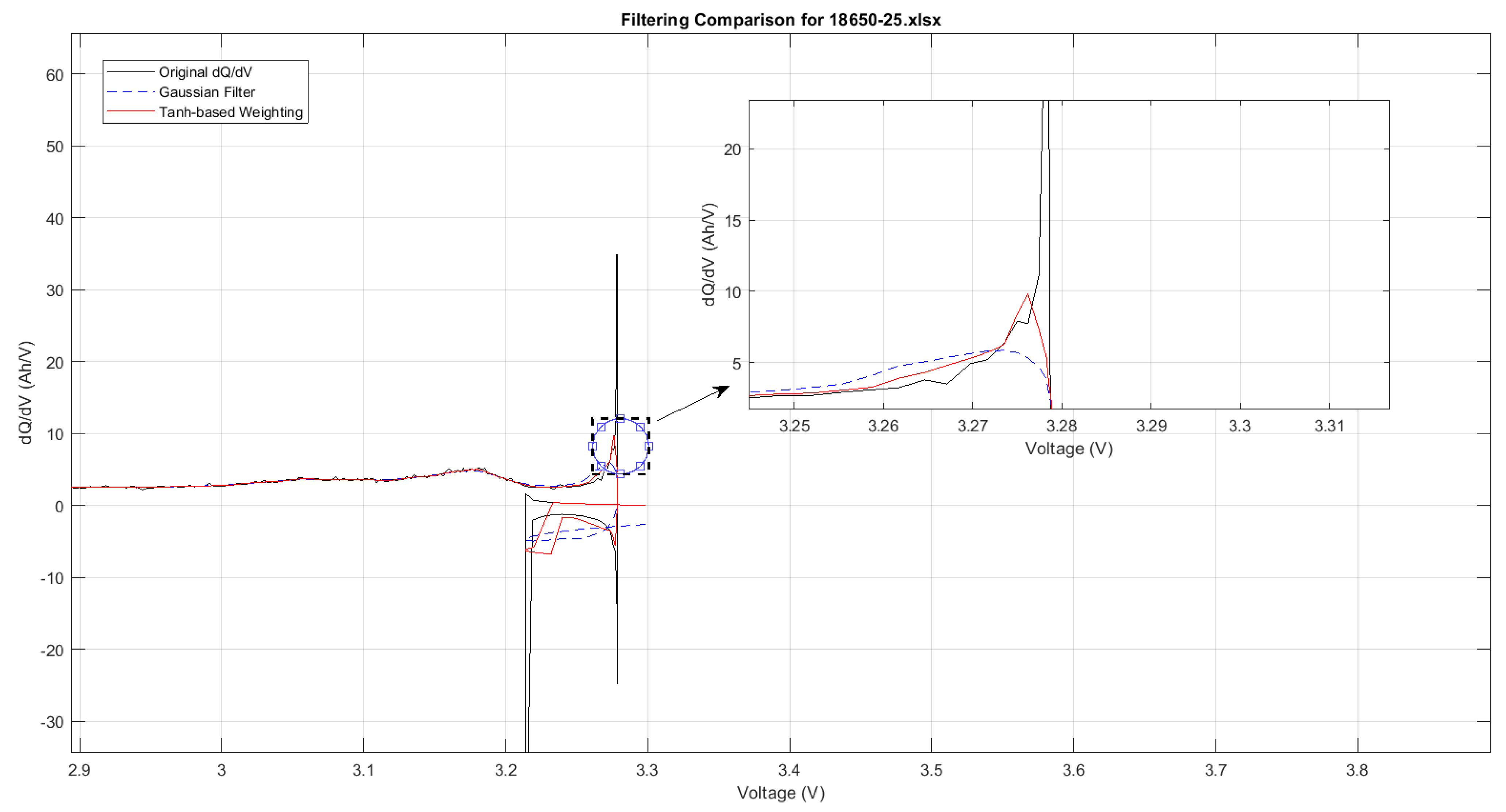

4. Adaptive Hybrid Filtering for Incremental Capacity Analysis of Lithium-Ion Batteries at Low Temperatures

During ICA at low temperatures, we identified a critical observation regarding the limitations of Gaussian filtering. While Gaussian filtering is commonly used to smooth noisy data, it tends to overly smooth important peaks in the ICA curves under challenging conditions, such as low temperatures. The Gaussian filter applies a uniform smoothing across all data points, thereby neglecting the need for varying levels of sensitivity in different regions of the curve. These peaks are crucial for identifying early degradation indicators and understanding long-term battery performance. Over-smoothing these features can obscure significant details and hinder accurate analysis.

In this section, we propose a novel Adaptive Hybrid Filtering (AHF) technique to address these challenges. The AHF adapts the smoothing process to retain critical features while effectively reducing noise by integrating local signal statistics such as skewness, kurtosis, and variance. Skewness, kurtosis, and variance are calculated for a local window of data to inform the adaptive filtering process, as defined in Equations (5)–(7), respectively. This application of adaptive smoothing, informed by local statistical properties, represents a novel contribution to the low-temperature lithium-ion battery signal analysis field, as it has not been previously employed in this context.

where

is the mean and

is the standard deviation of the data in the local window.

In this study, various weighting techniques were investigated across different window sizes, incorporating local statistics such as skewness, kurtosis, and variance. These methods were systematically evaluated to assess their efficacy in maintaining signal integrity while effectively reducing noise. A selection of these weighting techniques is presented in

Table 2, summarizing their formulations and applications. Among the weighting techniques investigated, the Tanh-based weighting formula demonstrated the most effective balance between noise reduction and the preservation of critical features.

This weight is then used to combine the local mean of the data with the Gaussian-filtered output:

where

is the Gaussian-filtered signal and

is the local mean.

In regions with high statistical values, indicating noisy or sharp transitions, the weight decreases, giving greater importance to the Gaussian filtered signal to smooth these regions while still retaining some influence from the local mean to preserve broader trends that would otherwise be completely removed by Gaussian filtering. Conversely, in regions with low statistical values—where the signal is stable, the weight increases, prioritizing the local mean to retain fine details, while the Gaussian-filtered signal provides subtle smoothing to avoid overfitting.

Figure 11 demonstrates how the Gaussian filter and the AHF perform at +25 °C. The AHF retains the sharp peaks and important transitions while smoothing noise effectively, showing its superior adaptability to the Gaussian filter at room temperature.

Battery behaviour becomes more sensitive at lower temperatures, making the preservation of peaks even more critical for accurate analysis.

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 demonstrate filtering performance at −25 °C and −30 °C, respectively. The AHF outperforms the Gaussian filter in both cases by retaining peaks and transitions while minimizing noise.

To find the quantitative performance differences between the filters and further evaluate the performance of the proposed AHF method, we utilize three metrics to assess accuracy, noise reduction, and feature preservation: Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and the Coefficient of Determination (R

2), defined as follows:

where:

is the actual value of the signal;

is the filtered value;

is the mean of the actual values;

is the number of data points in the signal.

MAE measures the average of all prediction errors, giving an intuitive sense of how far predicted values deviate from actual battery performance on a typical basis. Meanwhile, RMSE places extra emphasis on larger errors, illustrating the model’s handling of sudden or extreme deviations that often occur in low-temperature conditions. Finally, the R

2 statistic captures how well the variation in the observed data is explained by the model, providing an overall measure of prediction quality. The comparative study summarized in

Table 3 clearly demonstrates that the proposed AHF approach outperforms the Gaussian filter, showing superior results across all evaluation metrics, including MAE, RMSE, and R

2.

Compared to recent methods, such as the genetic marginalized particle filter [

39] and the LSTM-weighted fading extended Kalman filter [

40], the AHF technique offers unique advantages in detecting the electrochemical features. While these techniques emphasize broad temperature adaptation for state estimation, AHF excels in preserving critical electrochemical features by dynamically adjusting smoothing parameters based on real-time data analysis. This makes AHF particularly effective in retaining essential diagnostic details under low-temperature conditions, enhancing battery health assessments and degradation analysis.

As temperatures decrease, the advantages of the AHF become even more pronounced, particularly in terms of error reduction. This shows that the proposed AHF is more robust and capable of handling the complex behaviours of LIBs in harsh conditions.

5. Conclusions

An experimental study examining LIBs, based on size and chemistry, demonstrated varied effects of low temperatures on performance. The study revealed that different battery sizes and chemistries respond distinctively to cold conditions. The 18650 and 21700 batteries exhibited similar performance consistency under cold conditions, with the 21700 displaying a slight advantage in energy discharge, making it more suitable for applications requiring thermal stability along with significant energy output. In contrast, the 26650 batteries from both evaluated manufacturers displayed optimal energy discharge at room temperature but significantly deteriorated performance at −30 °C. The Efest 26650 preserved only 30.4% of its capacity at −30 °C, whereas the Fitorch 26650 maintained approximately 46.36%. The analysis also included two different chemistries, highlighting that not all chemistries perform equally under low temperatures due to variations in internal resistance and discharge capacity. To further emphasize these findings, an ICA was performed and showed that the 26650 exhibited very unstable behaviour under low temperatures.

These results emphasize the necessity of considering both the size and chemistry of batteries when evaluating their performance in cold settings. Future studies should explore a broader range of chemistries and battery sizes to determine which configurations perform optimally in cold conditions without preheating.

Moreover, in this study, an Adaptive Hybrid Filtering (AHF) approach was proposed for ICA of lithium-ion batteries, particularly focusing on its effectiveness across a range of temperatures, including cold extremes. The AHF method dynamically adjusts the smoothing based on local signal statistics, such as skewness, kurtosis, and variance, thereby offering an adaptive filtering process tailored to the specific characteristics of each segment of the ICA curve.

Future work will extend the present study by examining a broader range of cell chemistries. In particular, incorporating LiFePO4 (LFP) batteries, one of the most commercially dominant chemistries, would enable a more complete comparison of cold-temperature behavior across widely used cathode materials.

Future work should also address the limitations associated with the commercial cells used in this study. Detailed anode compositions and electrolyte formulations are not publicly disclosed, which restricts the ability to fully correlate low-temperature mechanisms with internal material properties. Studies using cells with fully known chemistries or direct collaboration with manufacturers would allow for deeper insight into these effects.