Improved FMEA Risk Assessment Based on Load Sharing and Its Application to a Magnetic Lifting System

Abstract

1. Introduction

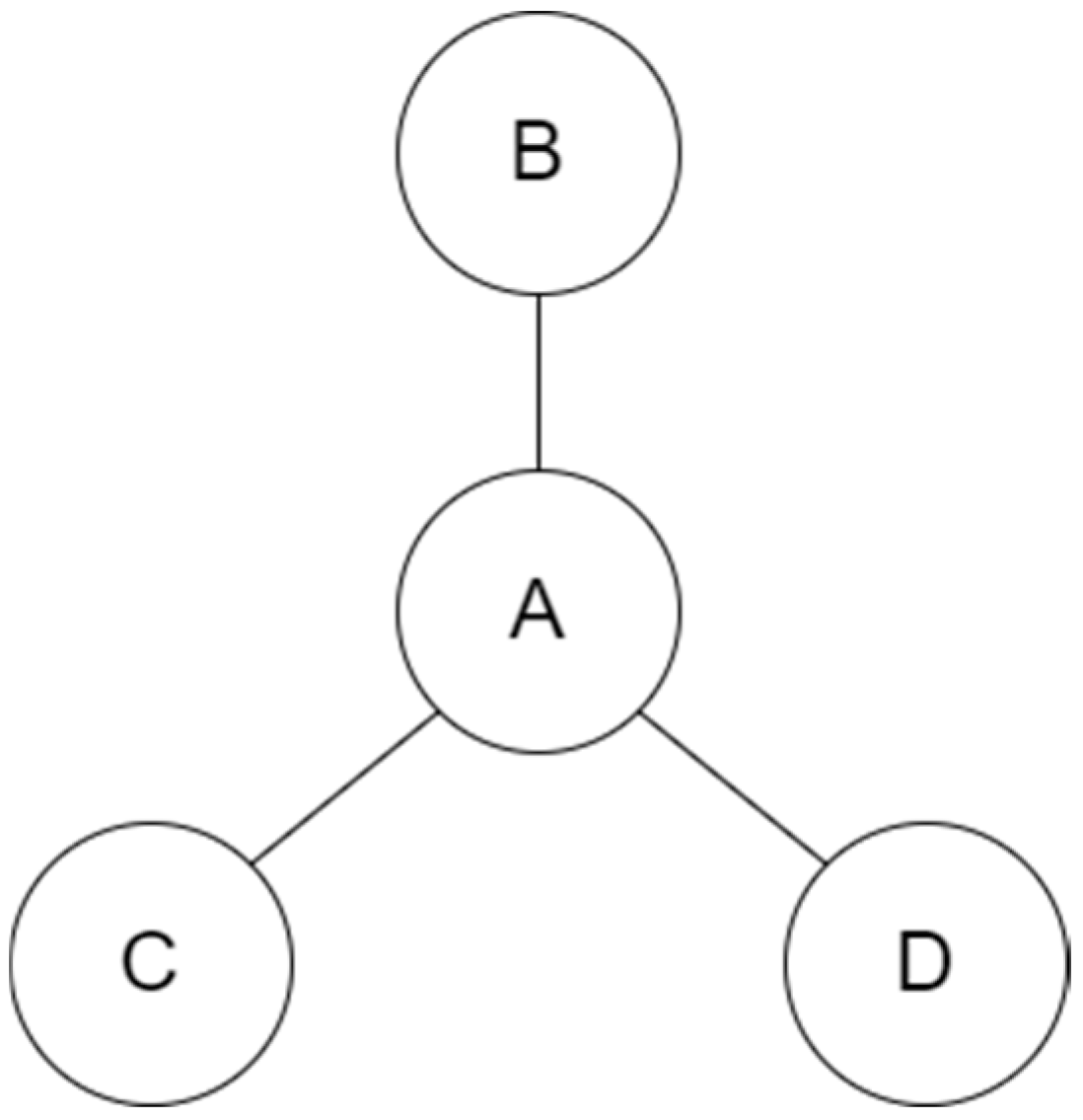

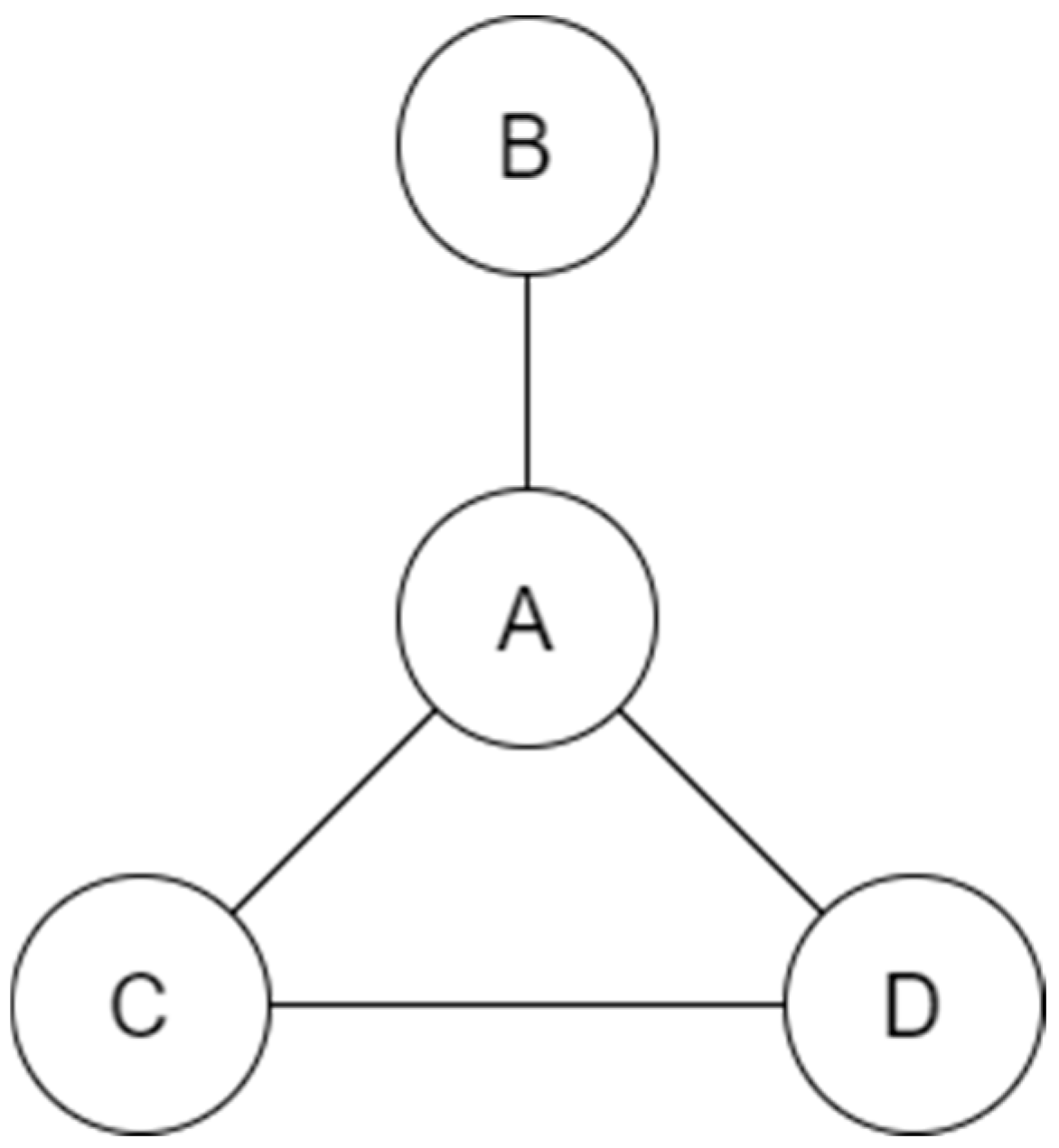

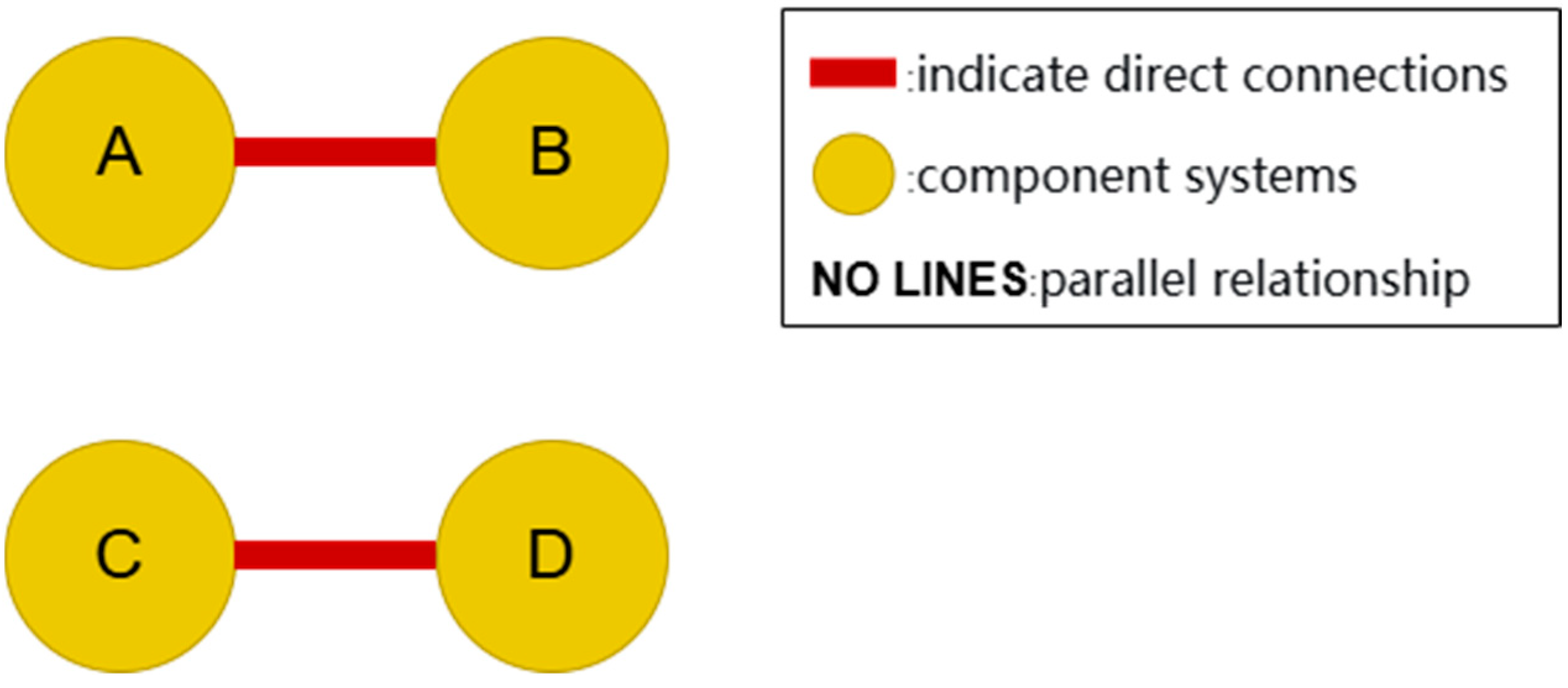

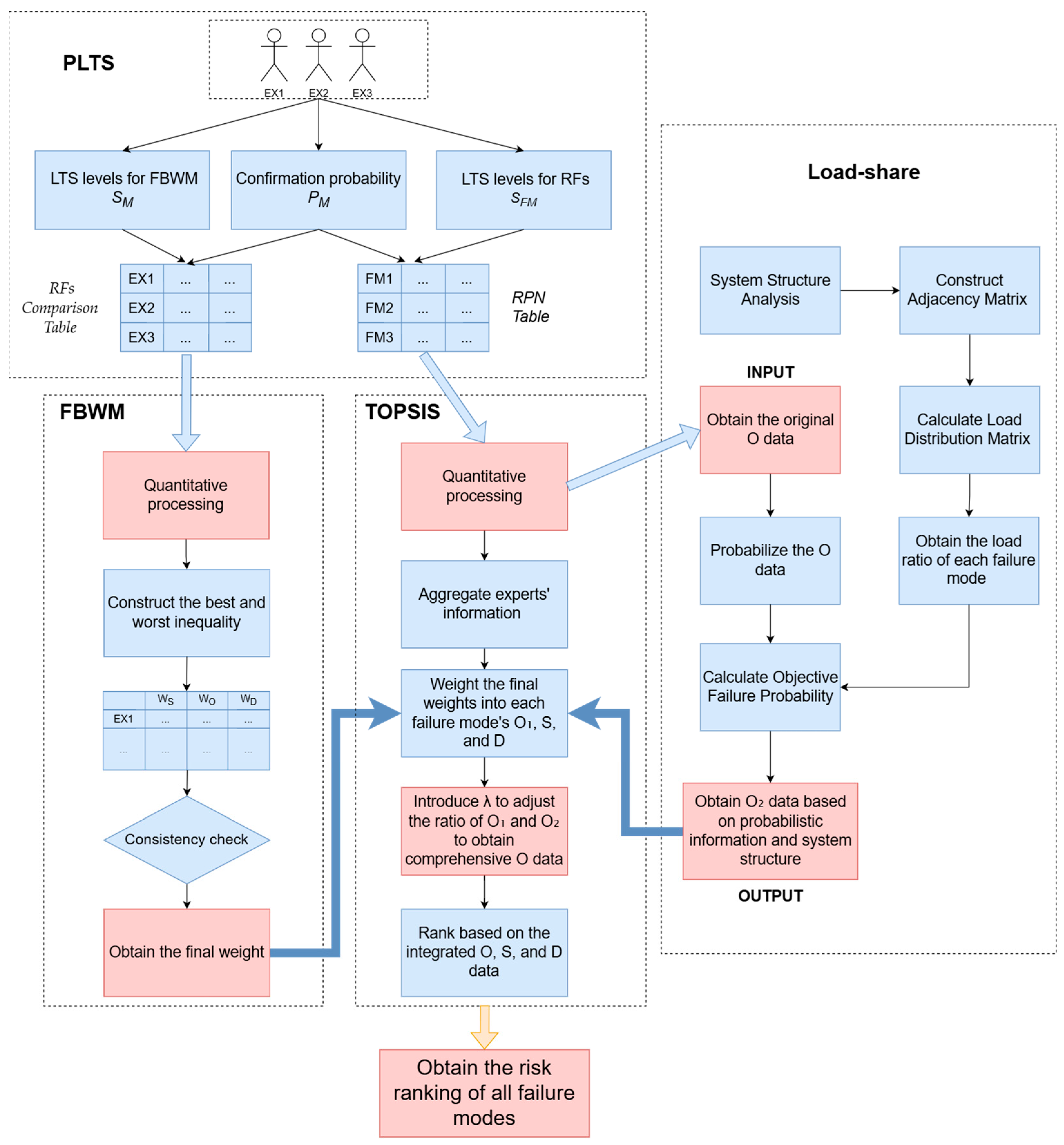

2. Load Sharing Method

3. Methodology

3.1. PLTS

3.2. FBWM

3.3. FMEA and Load Sharing

3.4. TOPSIS

4. Application of Multi-Magnetic System

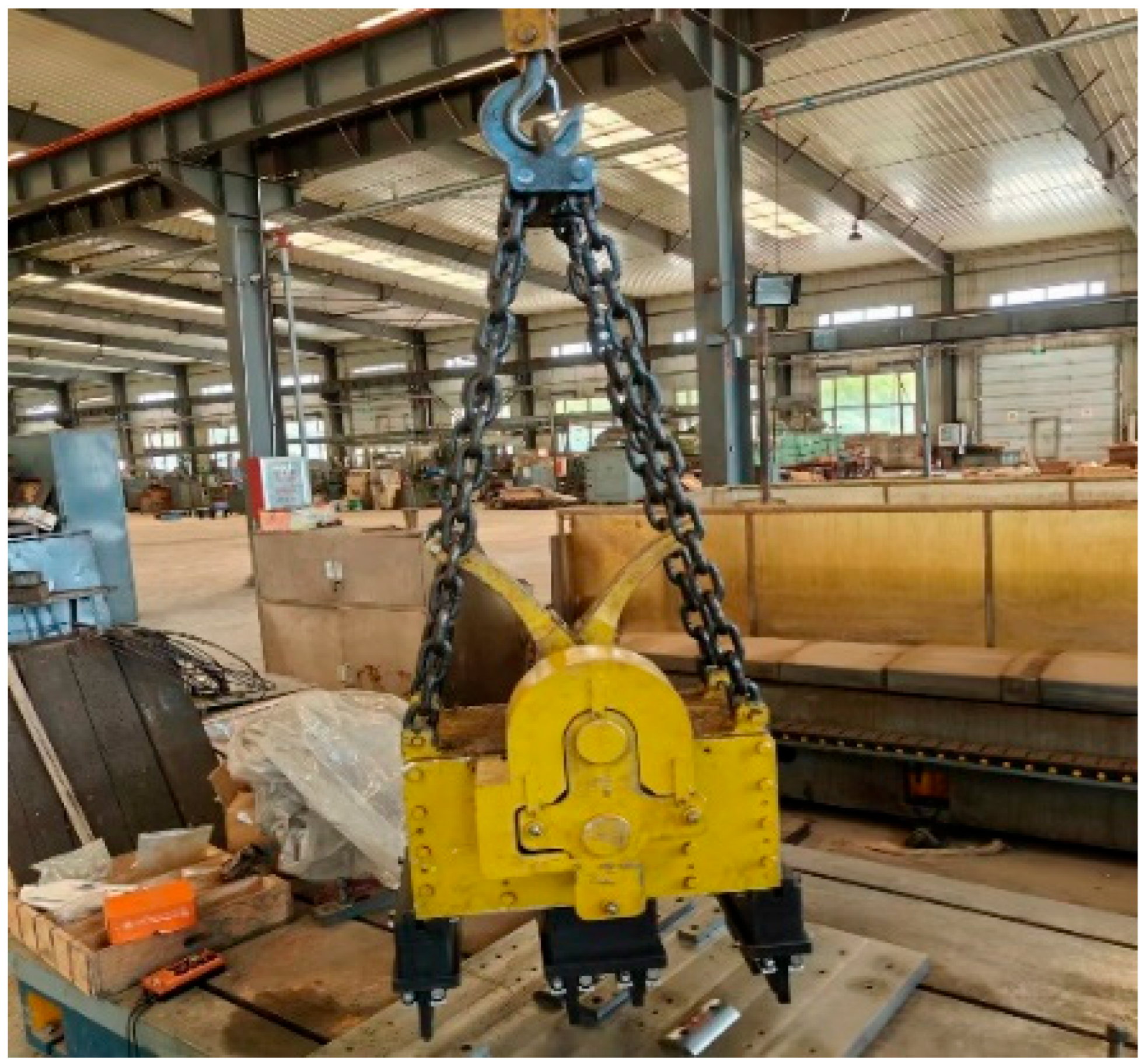

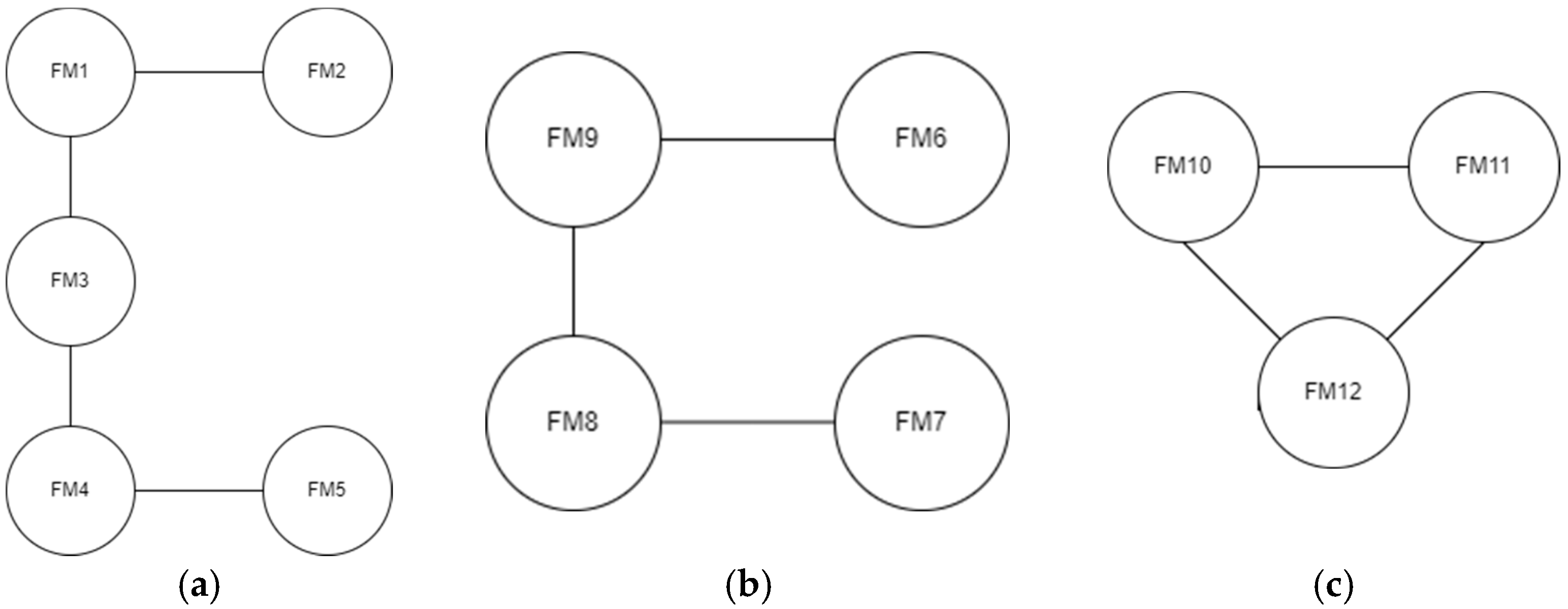

4.1. Case of Magnetic Crane

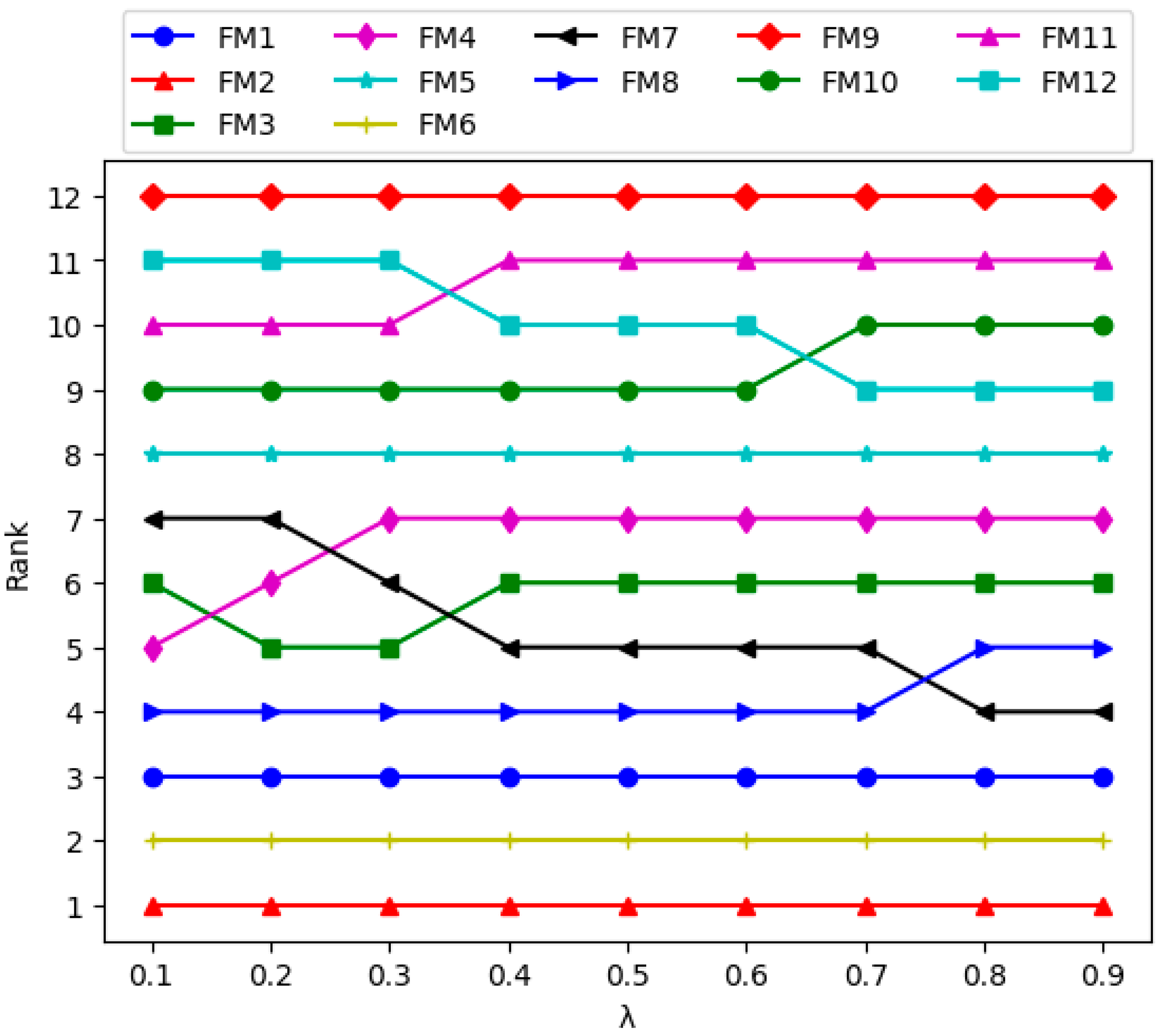

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

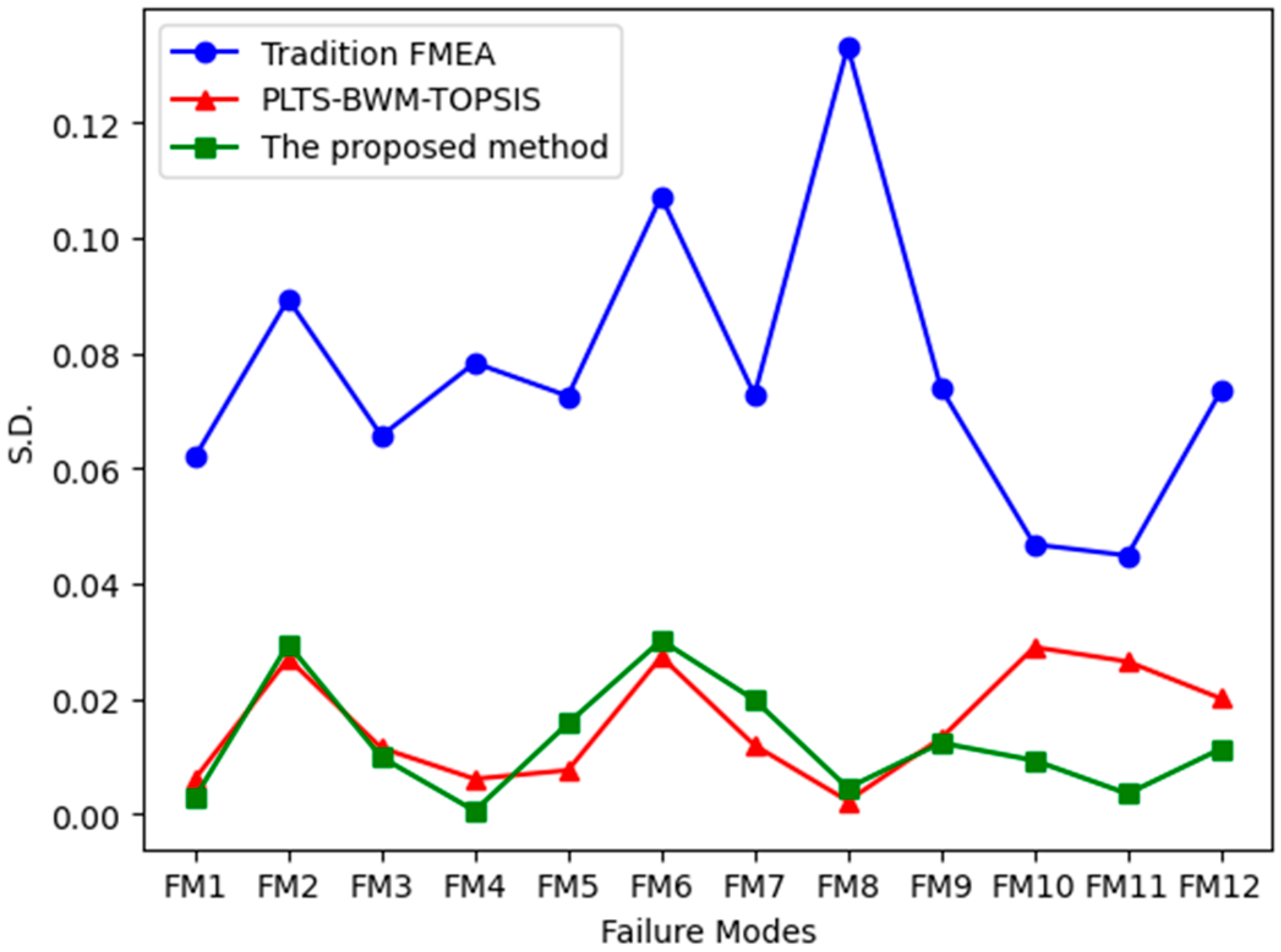

4.3. Comparative Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Derivation When Components Are Mutually Independent

Appendix A.2. Derivation When Components Are Interrelated

References

- Wang, L.; Li, B.; Hu, B.; Shen, G.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, Y. Failure mode effect and criticality analysis of ultrasound device by classification tracking. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, W.; Nie, W. Literature review and prospect of the development and application of FMEA in manufacturing industry. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 1409–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, J.E.; Alban, J.S.; Balseca, M.S.; Bustamante Villagómez, D.F.; Mancheno Falconi, M.G.; Garcia, M.V.J.S. Enhancing Institutional Sustainability Through Process Optimization: A Hybrid Approach Using FMEA and Machine Learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 17, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, L.; Li, X.-Y.; Liu, H.-C. A novel method for failure mode and effects analysis using fuzzy evidential reasoning and fuzzy Petri nets. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 11, 2381–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Song, S.; Zhou, D.; Pang, S.; Wei, C. Canonical triangular interval type-2 fuzzy set linguistic distribution assessment TODIM approach: A case study of FMEA for electric vehicles DC charging piles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 223, 119826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A. Risk assessment of crane operation hazards using modified FMEA approach with Z-Number and set pair analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z. Probabilistic linguistic term sets in multi-attribute group decision making. Inf. Sci. 2016, 369, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadinia, B.; Liao, H. Group decision making based on the relationships between the information measures for additive and multiplicative linguistic term sets. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 7901–7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Han, X.; Xu, Z.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Zhan, J. Fusion of probabilistic linguistic term sets for enhanced group decision-making: Foundations, survey and challenges. Inf. Fusion 2025, 116, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, X.; Xu, Z.; Liao, H.; Herrera, F. Probabilistic double hierarchy linguistic term set and its use in designing an improved VIKOR method: The application in smart healthcare. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2021, 72, 2611–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-C.; Ran, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G. Group risk assessment in failure mode and effects analysis using a hybrid probabilistic hesitant fuzzy linguistic MCDM method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 188, 116013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.-W.; Shiue, W.; Liou, J.J.; Tzeng, G.-H. A hybrid MCDM-based FMEA model for identification of critical failure modes in manufacturing. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 15733–15745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Ahmad, K.; Khan, Z.A.; Ahmad, S. Analysing the failure modes of water treatment plant using FMEA based on fuzzy AHP and fuzzy VIKOR methods. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 16821–16836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Díaz, H.; Soares, C. A failure analysis of floating offshore wind turbines using AHP-FMEA methodology. Ocean Eng. 2021, 234, 109261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamučar, D.; Ecer, F.; Cirovic, G.; Arlasheedi, M. Application of improved best worst method (BWM) in real-world problems. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.J.; Guo, B.H.; Huang, S.-W.; Yang, Y.-T. Failure mode and effect analysis using interval type-2 fuzzy and multiple-criteria decision-making methods. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X. Barrier assessment of EV business model innovation in China: An MCDM-based FMEA. Transp. Environ. 2024, 136, 104404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchekar, P.; Bhongade, A.S.; Rehman, A.U.; Mian, S.H. Assessing the Critical Factors Leading to the Failure of the Industrial Pressure Relief Valve Through a Hybrid MCDM-FMEA Approach. Machines 2024, 12, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafizadeh, E.; Hossein Mousavizadegan, S. A comprehensive risk assessment framework for composite Lenj Hulls: Integrating FMEA with CRITIC-CODAS. Civ. Eng. Environ. Syst. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, Y.; Huang, X. Optimal inspection-based maintenance strategy for k-out-of-n: G load-sharing systems consisting of three-state components. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 209, 111446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Gupta, P.K. Load-sharing system model and its application to the real data set. Math. Comput. Simul. 2012, 82, 1615–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seikh, M.R.; Chatterjee, P. Sustainable strategies for electric vehicle adoption: A confidence level-based interval-valued spherical fuzzy MEREC-VIKOR approach. Inf. Sci. 2025, 699, 121814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abadi, A.M.; Handhal, A.M.; Abdulhasan, M.A.; Ali, W.L.; Hassan, J.; Al Aboodi, A.H. Optimal siting of large photovoltaic solar farms at Basrah governorate, Southern Iraq using hybrid GIS-based Entropy-TOPSIS and AHP-TOPSIS models. Renew. Energy 2025, 241, 122308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadian, M.; Otaghsara, S.K.; Yazdani, M.; Ignatius, J. A state-of the-art survey of TOPSIS applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 13051–13069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y. A multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) framework for designing an optimal state-specific hybrid maintenance policy for a series k-out-of-n load-sharing system. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 265, 111587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejčí, J.; Stoklasa, J. Aggregation in the analytic hierarchy process: Why weighted geometric mean should be used instead of weighted arithmetic mean. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 114, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, S.; Rastegar, M.; Dehghanian, P. An fbwm-topsis approach to identify critical feeders for reliability centered maintenance in power distribution systems. Manuf. Rev. 2020, 15, 3893–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Shi, Z.; Bai, J. FMEA Risk Assessment Method for Aircraft Power Supply System Based on Probabilistic Language-TOPSIS. Aerospace 2025, 12, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trung, D.D. Development of data normalization methods for multi-criteria decision making: Applying for MARCOS method. Manuf. Rev. 2022, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Tang, Y. Modeling and fusing the uncertainty of FMEA experts using an entropy-like measure with an application in fault evaluation of aircraft turbine rotor blades. Entropy 2018, 20, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, C.; Chen, X. Risk analysis and mitigation of pressurization test for civil aircraft airtight cabin doors based on FMEA. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3080, 012142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure Group | Function | Item | Failed Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission Mechanism | Magnetic Circuit Switching | FM1 | Ratcheting Chain Fracture |

| FM2 | Box Chain Fracture | ||

| FM3 | Ratchet Wear | ||

| FM4 | Gear Wear | ||

| FM5 | Rotating Shaft Wear | ||

| Magnetic System | Lifting Heavy Objects | FM6 | Permanent Magnet Failure |

| FM7 | Outer Yoke Failure | ||

| FM8 | Inner Yoke Failure | ||

| FM9 | Pole Shoe Failure | ||

| Movable Pole Face Mechanism | Achieve a higher degree of fit with the workpiece surface | FM10 | T-Type Movable Pole Jamming |

| FM11 | Stopper Movable Pole Jamming | ||

| FM12 | Cam Jamming |

| Expert | Experience | Years of Study |

|---|---|---|

| EX1 | Responsible for the full-cycle development of the multi-magnetic system lifting permanent magnets, from design to manufacturing | 10 |

| EX2 | The critical optimization of the movable pole face mechanism | 3 |

| EX3 | Design phase of the movable pole face mechanism | 3 |

| Best | S | O | D | S | O | D | Worst | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX1 | S | D | ||||||

| EX2 | S | D | ||||||

| EX3 | S | D |

| Best | S | O | D | S | O | D | Worst | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX1 | S | 1 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 2.2 | 1 | D |

| EX2 | S | 1 | 2.5 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 2.2 | 1 | D |

| EX3 | S | 1 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2 | 1 | D |

| CR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX1 | 0.64798851 | 0.23706897 | 0.11494253 | 0.02666667 |

| EX2 | 0.62875817 | 0.25359477 | 0.11764706 | 0.00877578 |

| EX3 | 0.54251012 | 0.30364372 | 0.15384615 | 0.01142857 |

| 0.607304011 | 0.264471973 | 0.128224016 |

| S | O | D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM1 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM2 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM3 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM4 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM5 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM6 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM7 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM8 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM9 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM10 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM11 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 | ||||

| FM12 | EX1 | |||

| EX2 | ||||

| EX3 |

| FM1 | 0.453223 | 0.001 | 0.315083 | 0.001 |

| FM2 | 1.001 | 0.278934 | 0.060916 | 0.095683 |

| FM3 | 0.415722 | 0.044372 | 0.092396 | 0.309919 |

| FM4 | 0.396597 | 0.009089 | 0.247468 | 0.370786 |

| FM5 | 0.355375 | 0.29524 | 0.146524 | 0.46141 |

| FM6 | 0.811309 | 0.283377 | 0.001 | 0.551302 |

| FM7 | 0.400407 | 0.287615 | 0.003615 | 0.591554 |

| FM8 | 0.377912 | 0.095868 | 0.412672 | 1.001 |

| FM9 | 0.046779 | 0.094768 | 0.40677 | 0.967412 |

| FM10 | 0.001 | 1.001 | 1.001 | 0.030928 |

| FM11 | 0.011105 | 1.001 | 0.800413 | 0.071771 |

| FM12 | 0.027902 | 1.001 | 0.589698 | 0.801735 |

| S | O | D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FM1 | 0.275244 | 0.041798 | 0.000128 |

| FM2 | 0.607911 | 0.04494 | 0.012269 |

| FM3 | 0.25247 | 0.018086 | 0.039739 |

| FM4 | 0.240855 | 0.033926 | 0.047544 |

| FM5 | 0.215821 | 0.058417 | 0.059164 |

| FM6 | 0.492711 | 0.037605 | 0.07069 |

| FM7 | 0.243169 | 0.038511 | 0.075851 |

| FM8 | 0.229507 | 0.067247 | 0.128352 |

| FM9 | 0.028409 | 0.066321 | 0.124045 |

| FM10 | 0.000607 | 0.264736 | 0.003966 |

| FM11 | 0.006744 | 0.238212 | 0.009203 |

| FM12 | 0.016945 | 0.210348 | 0.102802 |

| RANK | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM1 | 0.420488 | 0.275659 | 0.395978 | 3 |

| FM2 | 0.248567 | 0.608019 | 0.709816 | 1 |

| FM3 | 0.441619 | 0.254958 | 0.366015 | 6 |

| FM4 | 0.44106 | 0.245394 | 0.35748 | 7 |

| FM5 | 0.44843 | 0.226779 | 0.335865 | 8 |

| FM6 | 0.261122 | 0.49752 | 0.655803 | 2 |

| FM7 | 0.432402 | 0.254926 | 0.370895 | 5 |

| FM8 | 0.426839 | 0.266934 | 0.384757 | 4 |

| FM9 | 0.612544 | 0.13585 | 0.181522 | 12 |

| FM10 | 0.619911 | 0.246681 | 0.284656 | 9 |

| FM11 | 0.613435 | 0.220398 | 0.26432 | 11 |

| FM12 | 0.594014 | 0.218571 | 0.268983 | 10 |

| FM1 | FM2 | FM3 | FM4 | FM5 | FM6 | FM7 | FM8 | FM9 | FM10 | FM11 | FM12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 2 | 0.2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 3 | 0.3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 4 | 0.4 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 10 |

| 5 | 0.5 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 10 |

| 6 | 0.6 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 10 |

| 7 | 0.7 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| 8 | 0.8 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| 9 | 0.9 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| FMEA | PLTS-FBWM-TOPSIS | This Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | RANK | RANK | RANK | |||

| FM1 | 56.15464 | 10 | 0.417681 | 3 | 0.395978 | 3 |

| FM2 | 81.03893 | 3 | 0.688908 | 1 | 0.709816 | 1 |

| FM3 | 59.51582 | 9 | 0.368913 | 6 | 0.366015 | 6 |

| FM4 | 70.99446 | 4 | 0.373307 | 5 | 0.35748 | 7 |

| FM5 | 65.76415 | 8 | 0.330949 | 8 | 0.335865 | 8 |

| FM6 | 97.21092 | 2 | 0.628241 | 2 | 0.655803 | 2 |

| FM7 | 65.9413 | 7 | 0.35927 | 7 | 0.370895 | 5 |

| FM8 | 120.7705 | 1 | 0.409778 | 4 | 0.384757 | 4 |

| FM9 | 66.99181 | 5 | 0.216856 | 12 | 0.181522 | 12 |

| FM10 | 42.41067 | 11 | 0.299069 | 9 | 0.284656 | 9 |

| FM11 | 40.6663 | 12 | 0.256036 | 10 | 0.26432 | 11 |

| FM12 | 66.54952 | 6 | 0.237386 | 11 | 0.268983 | 10 |

| FMEA | PLTS-FBWM-TOPSIS | This Method | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S.D. | S.D. | S.D. | |

| FM1 | 0.061956 | 0.006072 | 0.002804 |

| FM2 | 0.089411 | 0.02695 | 0.029429 |

| FM3 | 0.065664 | 0.011418 | 0.009803 |

| FM4 | 0.078329 | 0.00605 | 0.0005 |

| FM5 | 0.072558 | 0.00755 | 0.015694 |

| FM6 | 0.107253 | 0.02727 | 0.030127 |

| FM7 | 0.072753 | 0.011893 | 0.019782 |

| FM8 | 0.133247 | 0.002238 | 0.004481 |

| FM9 | 0.073912 | 0.013117 | 0.012297 |

| FM10 | 0.046792 | 0.028929 | 0.009267 |

| FM11 | 0.044867 | 0.026442 | 0.003473 |

| FM12 | 0.073424 | 0.020027 | 0.011247 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Ding, N. Improved FMEA Risk Assessment Based on Load Sharing and Its Application to a Magnetic Lifting System. Machines 2025, 13, 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121113

Sun B, Wang L, Zhang J, Ding N. Improved FMEA Risk Assessment Based on Load Sharing and Its Application to a Magnetic Lifting System. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121113

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Bo, Lei Wang, Jian Zhang, and Ning Ding. 2025. "Improved FMEA Risk Assessment Based on Load Sharing and Its Application to a Magnetic Lifting System" Machines 13, no. 12: 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121113

APA StyleSun, B., Wang, L., Zhang, J., & Ding, N. (2025). Improved FMEA Risk Assessment Based on Load Sharing and Its Application to a Magnetic Lifting System. Machines, 13(12), 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121113