The Role of Graphite-like Carbon Films in Mitigating Fretting Wear of Slewing Bearings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hertzian Contact Theory

2.2. Archard Wear Model

2.3. Friction and Wear

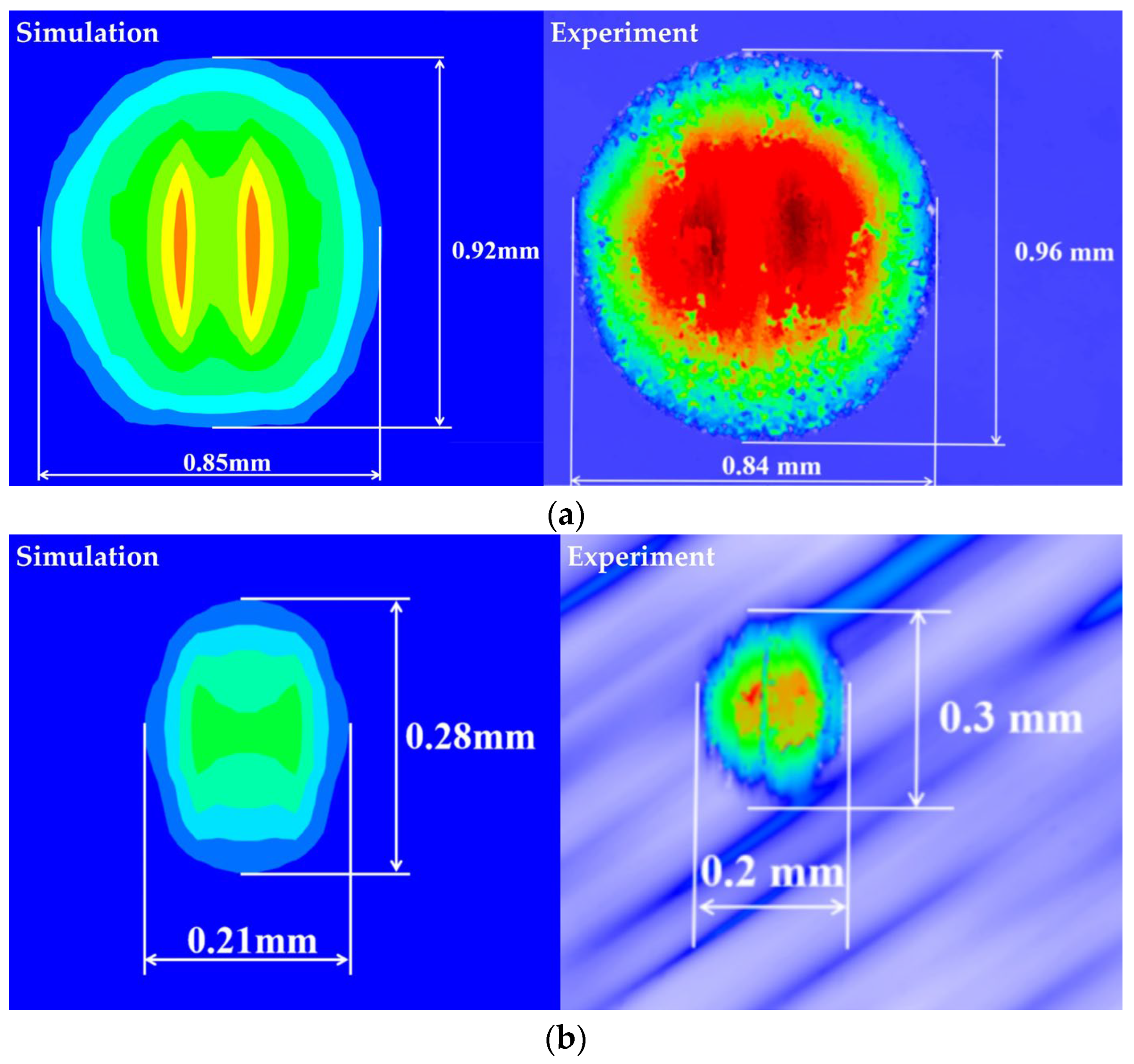

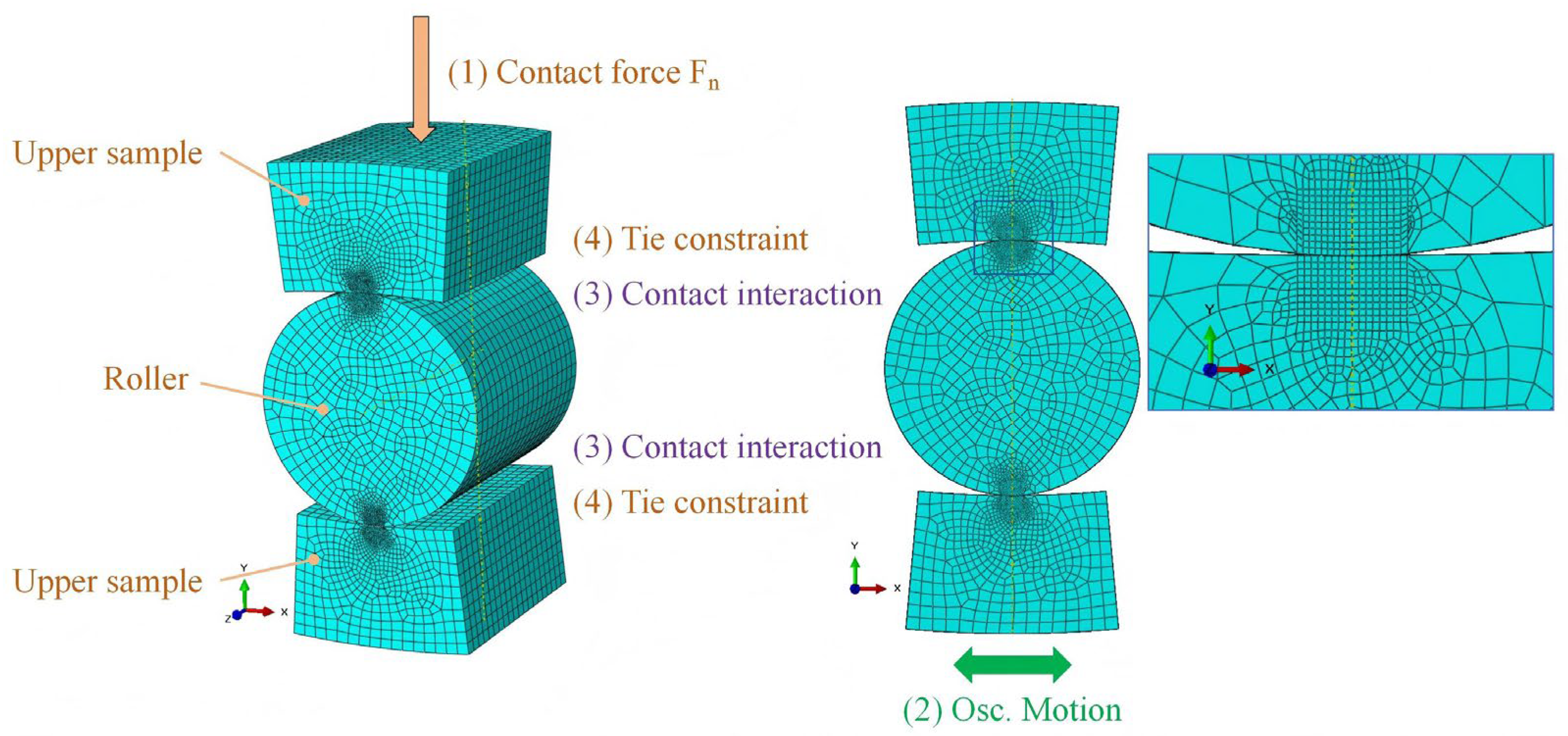

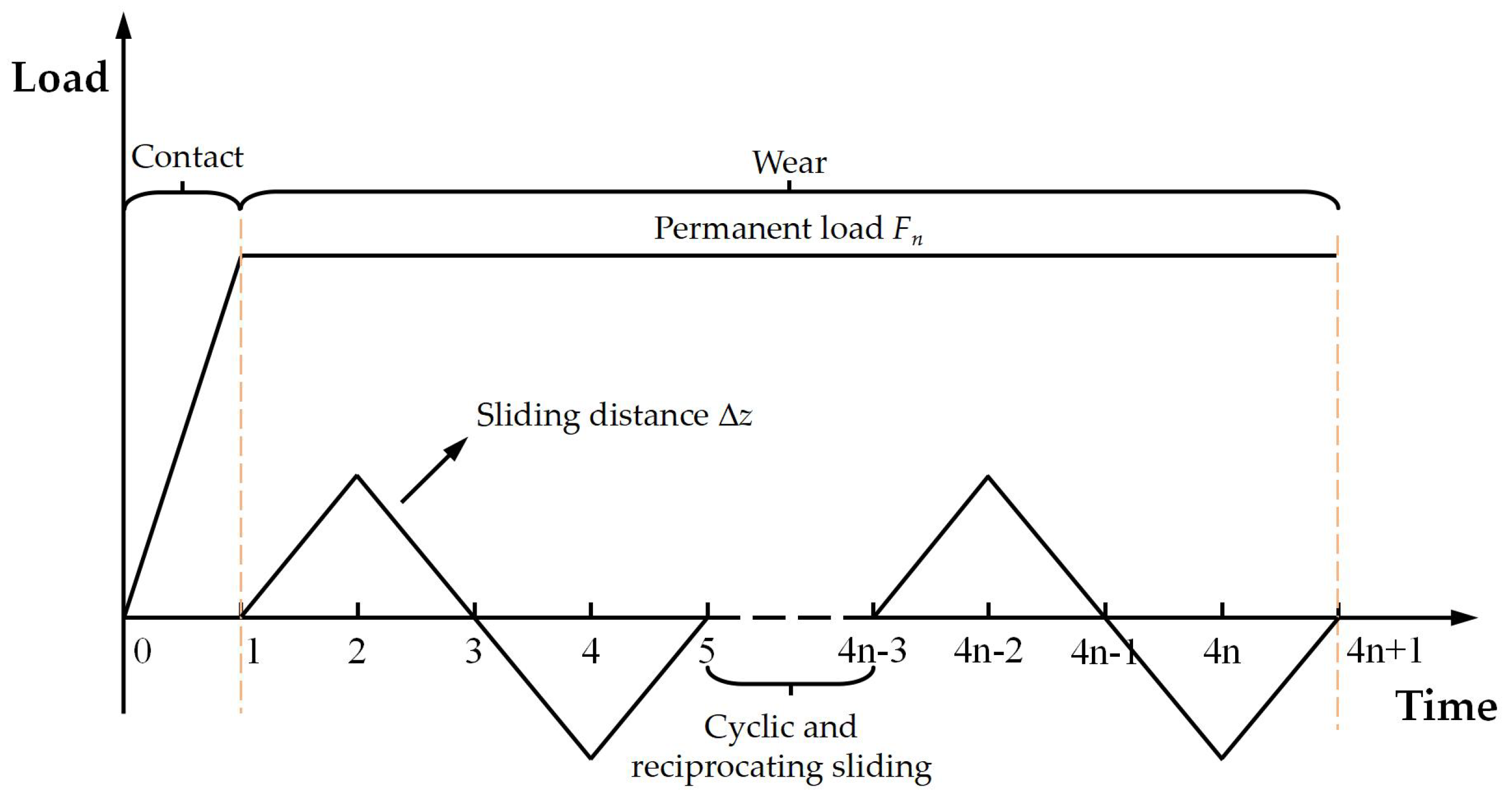

2.4. Fretting Wear Simulation Analysis

3. Analysis of Results

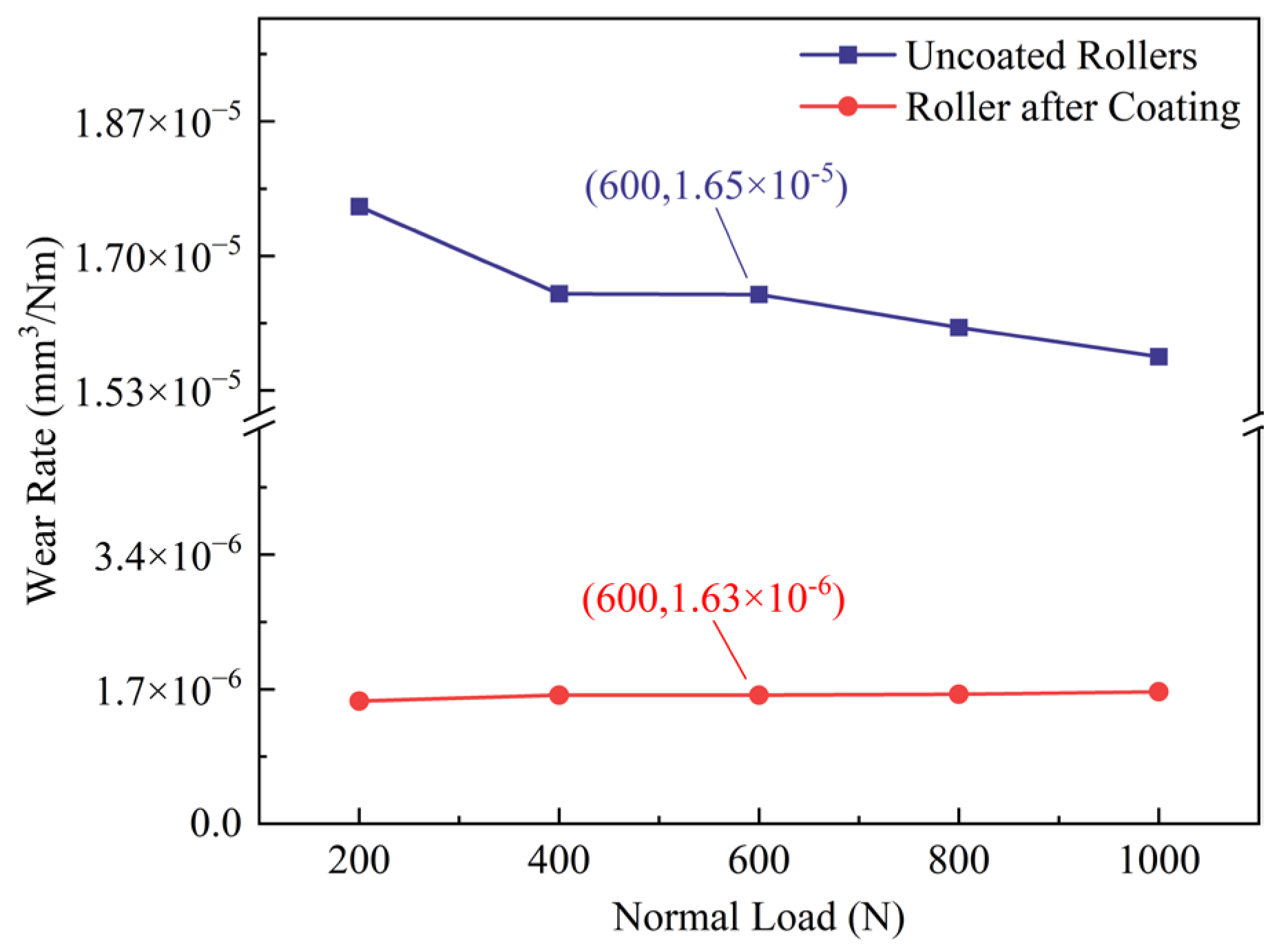

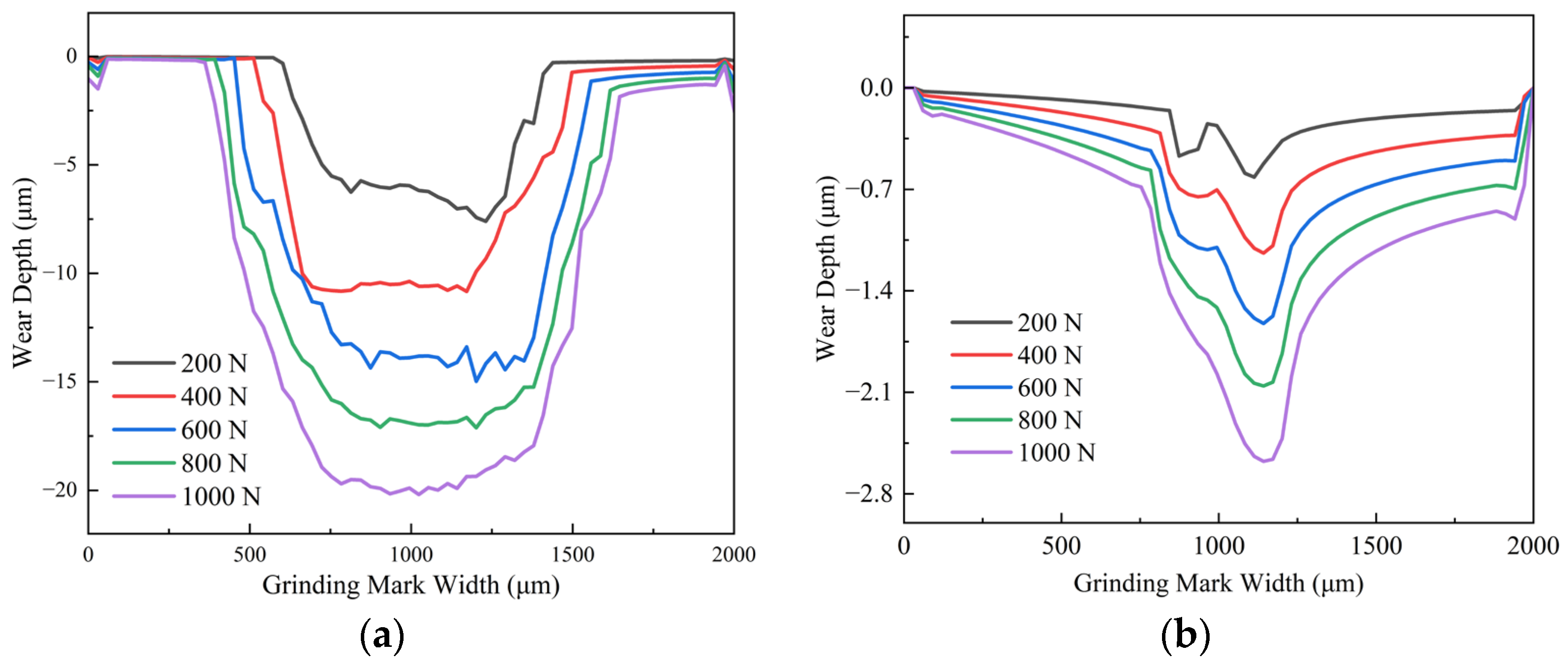

3.1. Normal Load

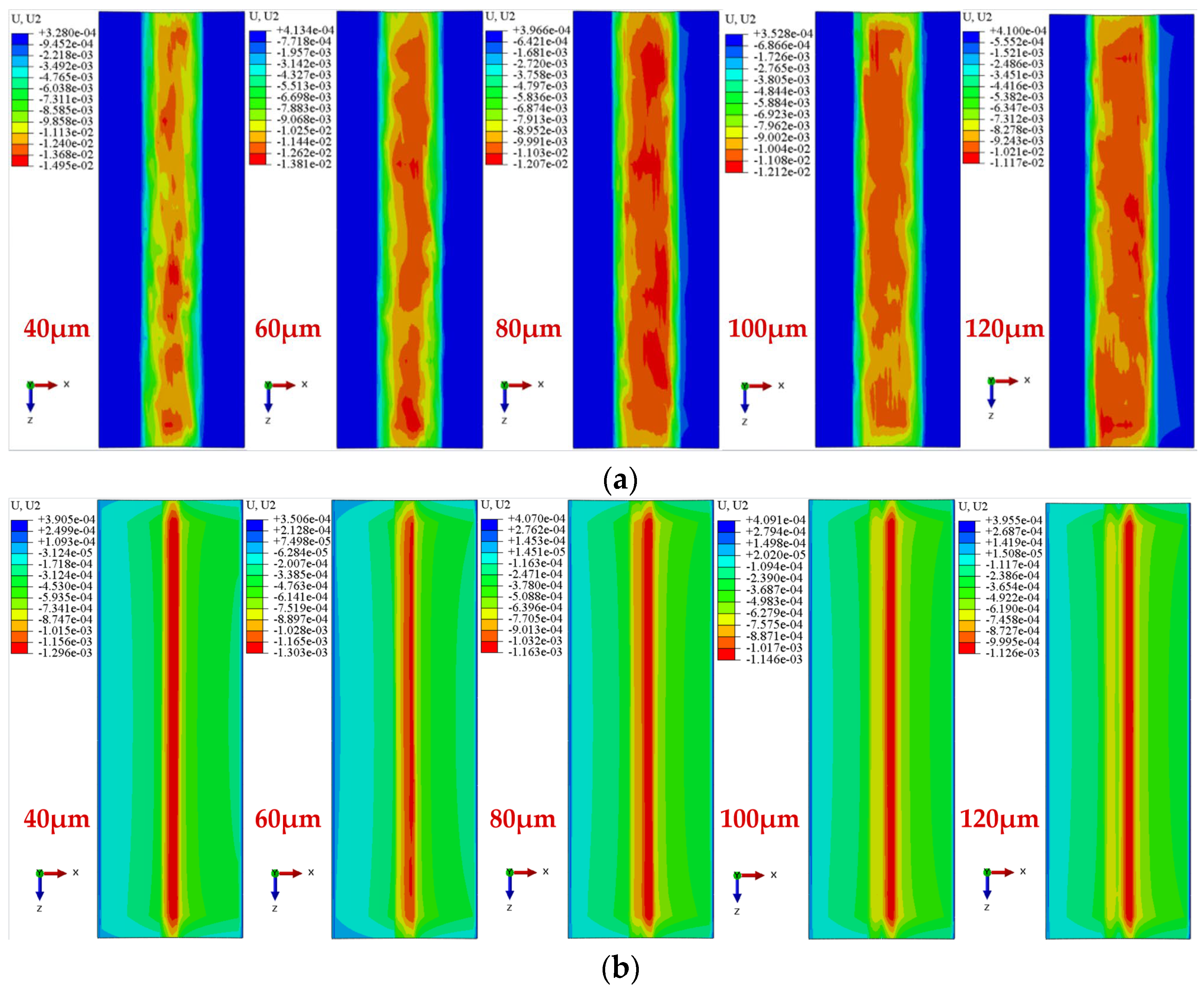

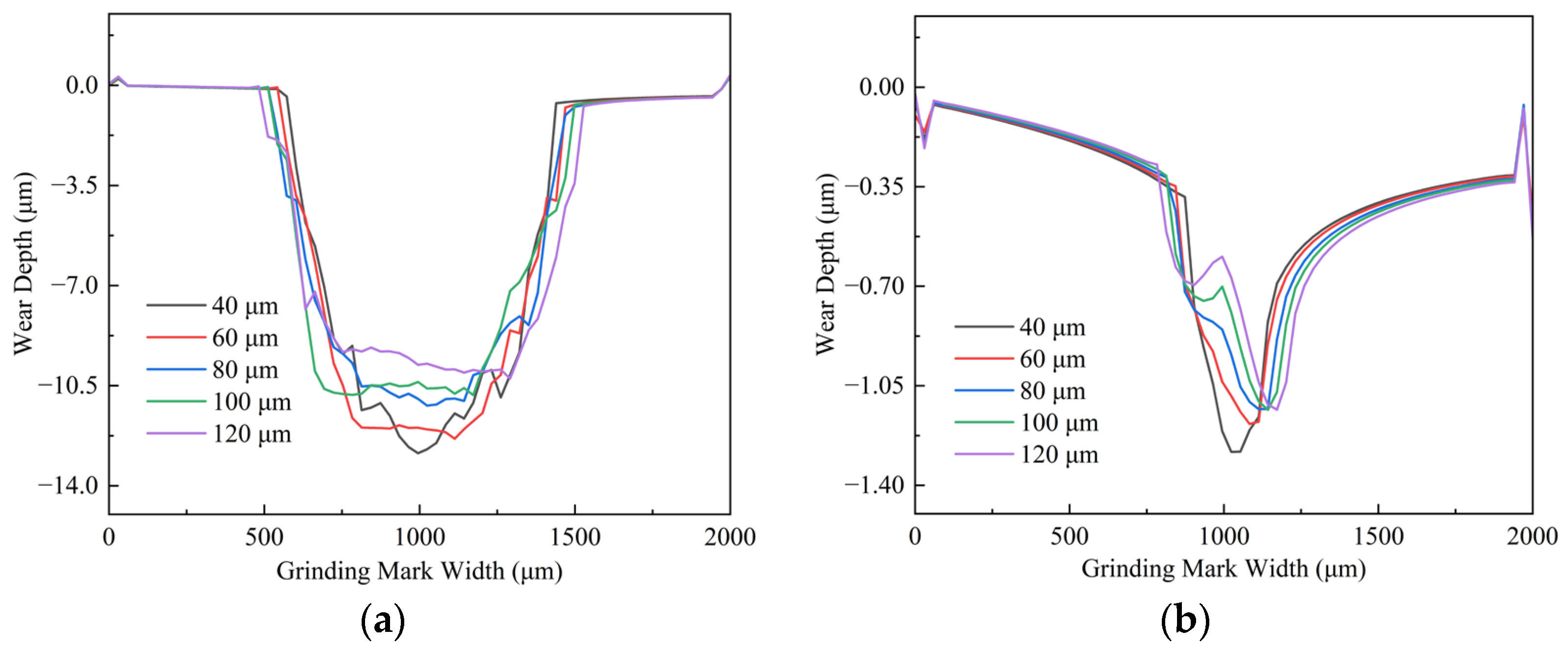

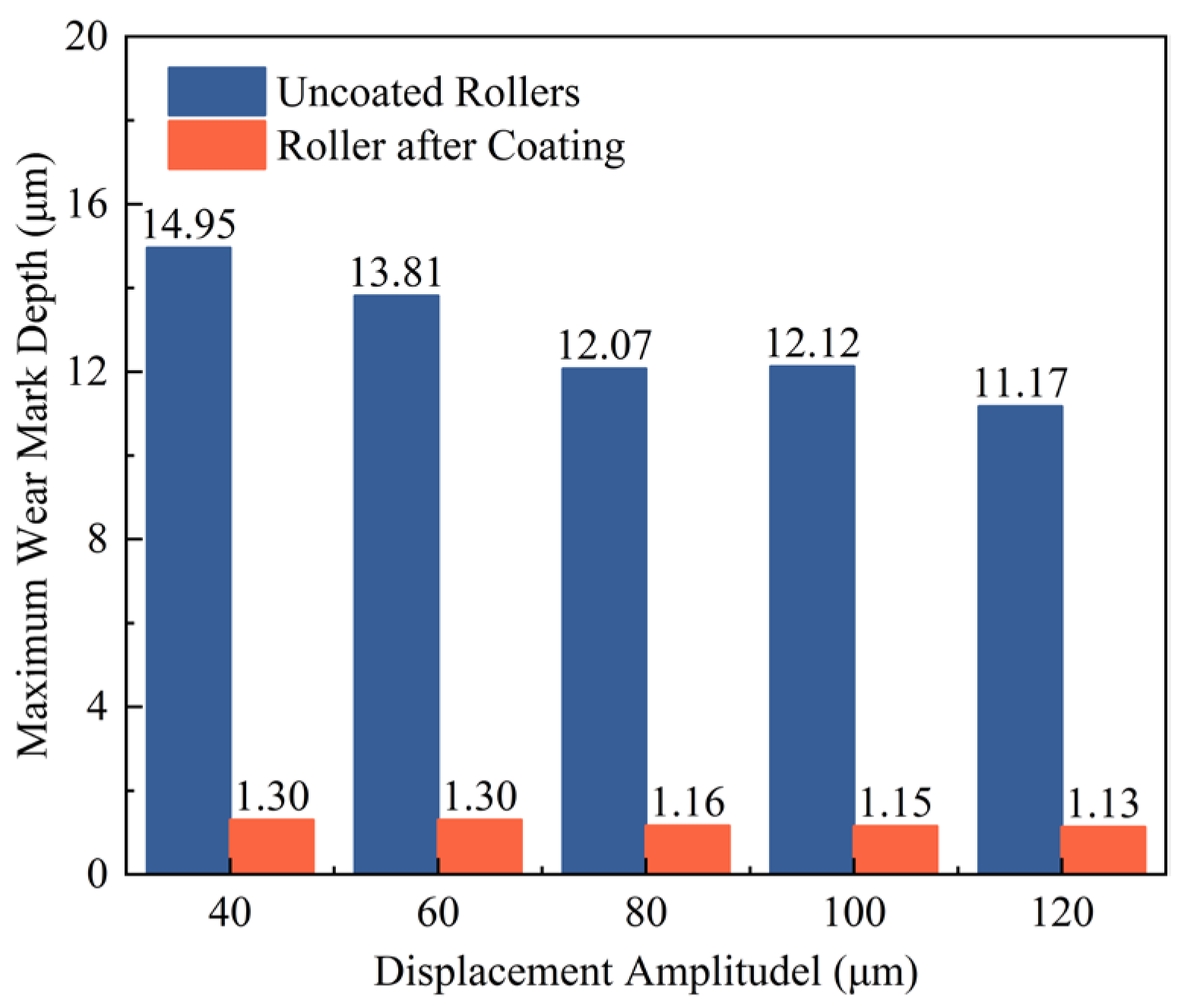

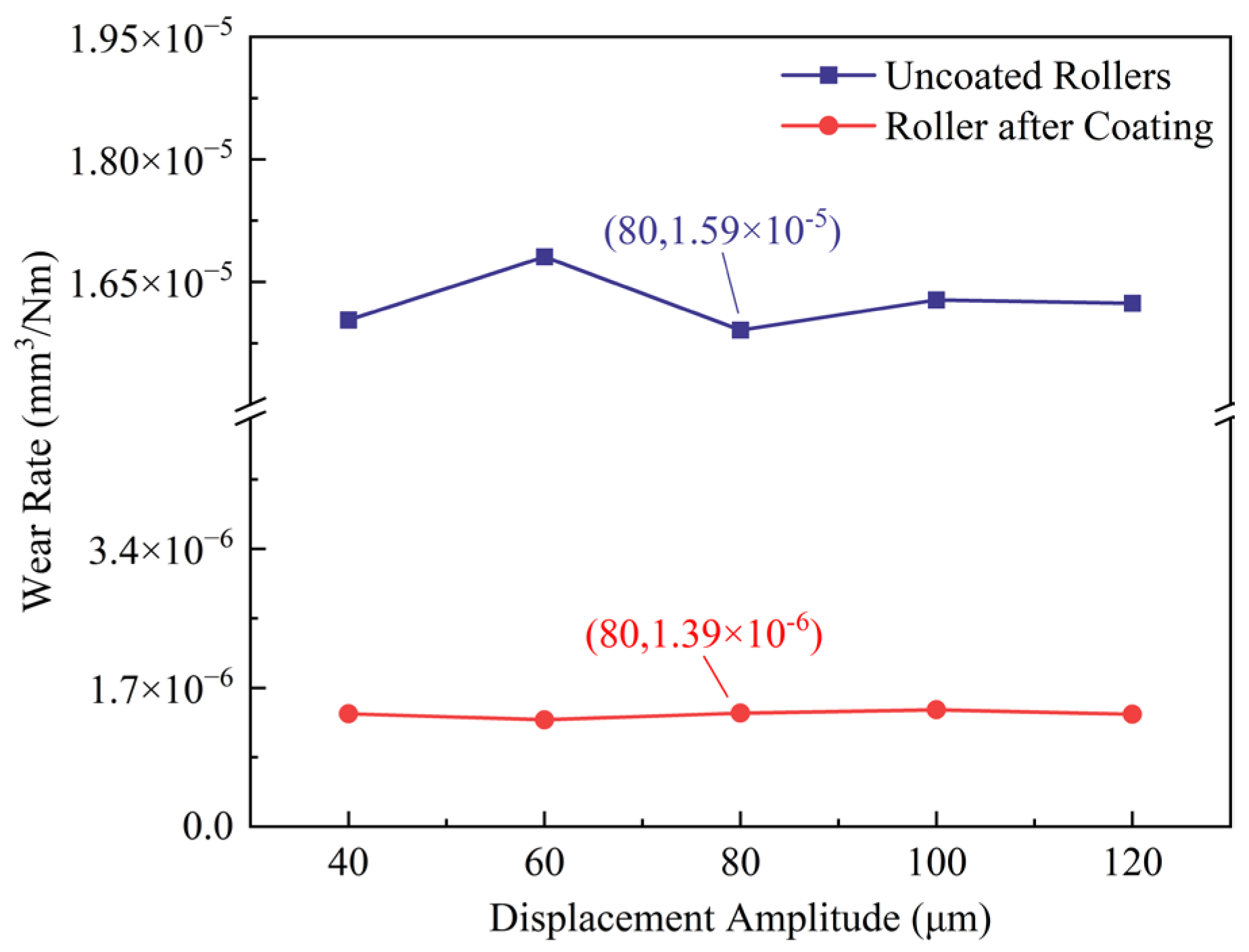

3.2. Displacement Amplitude

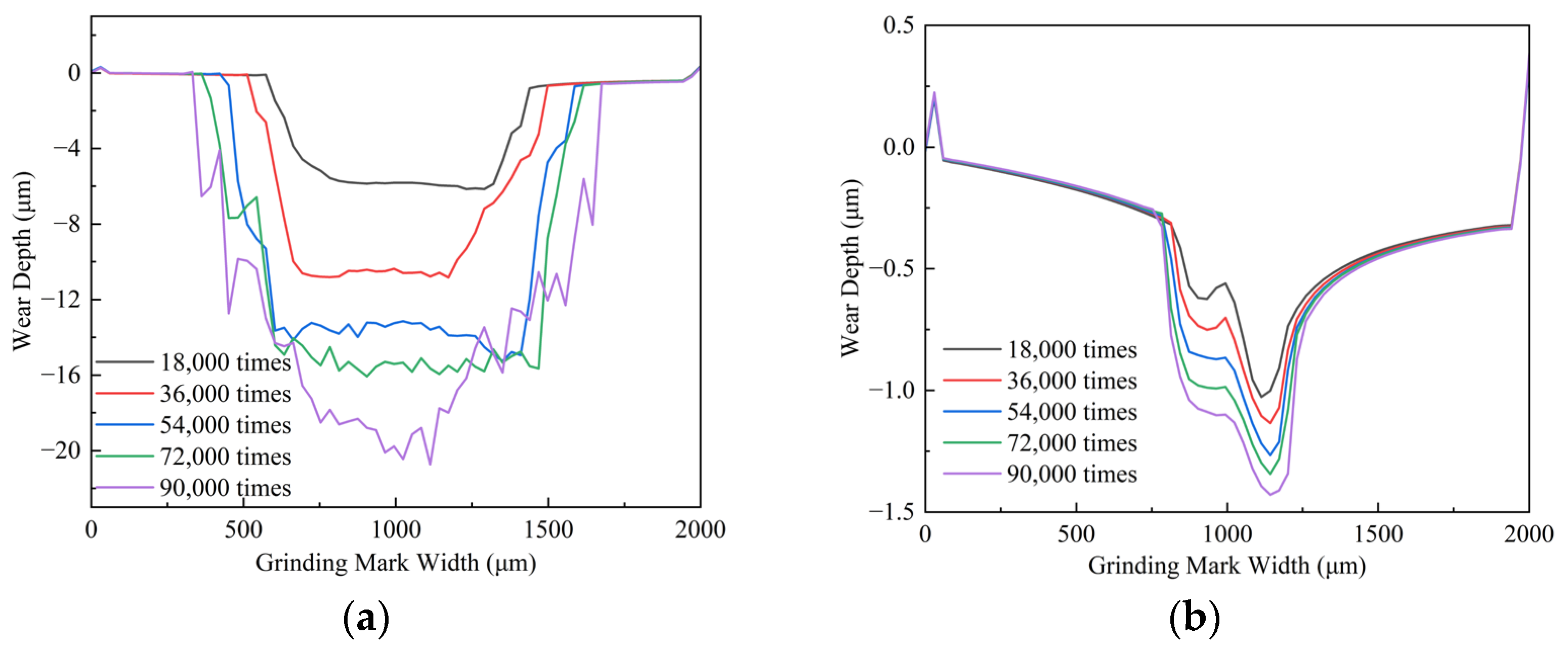

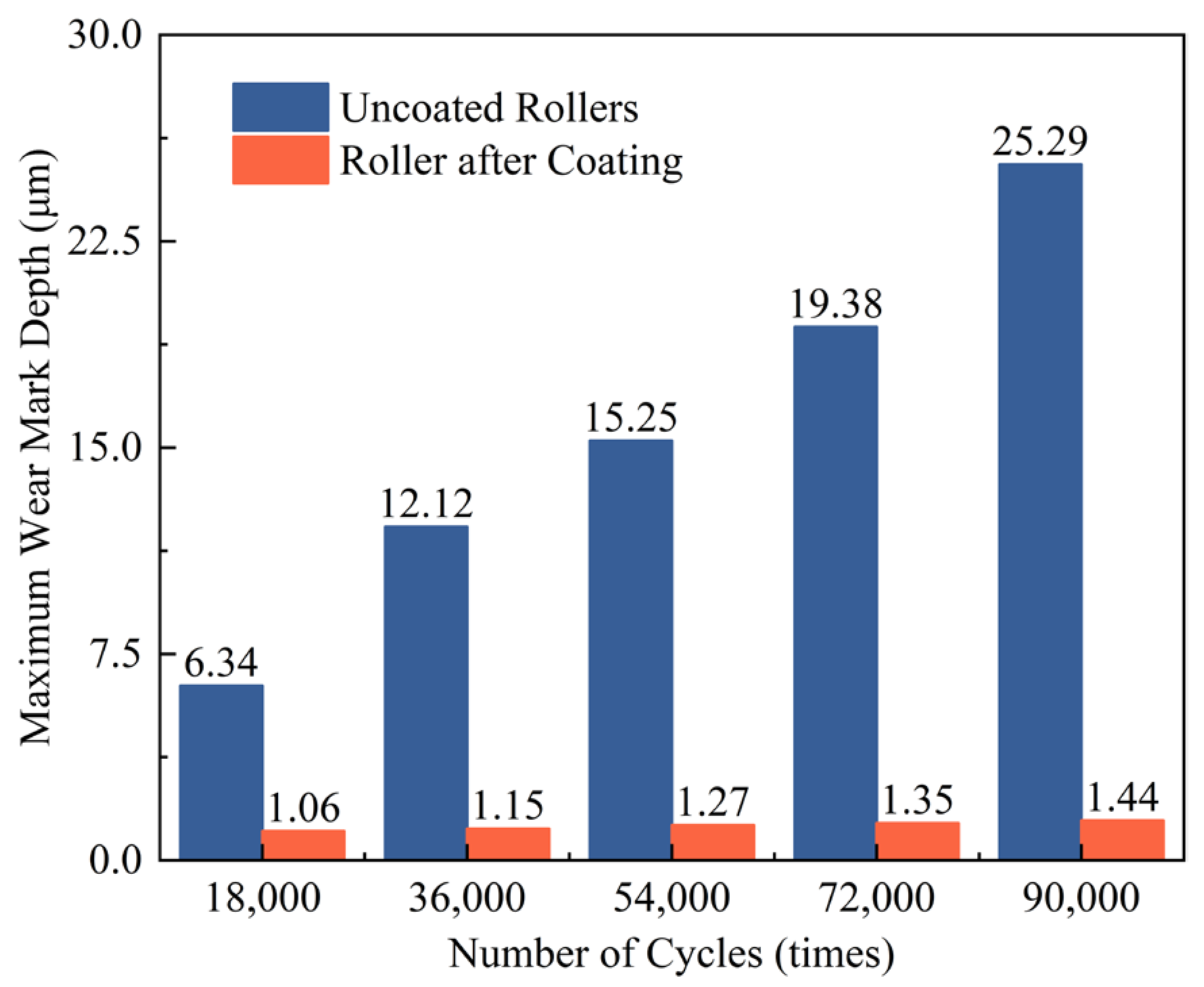

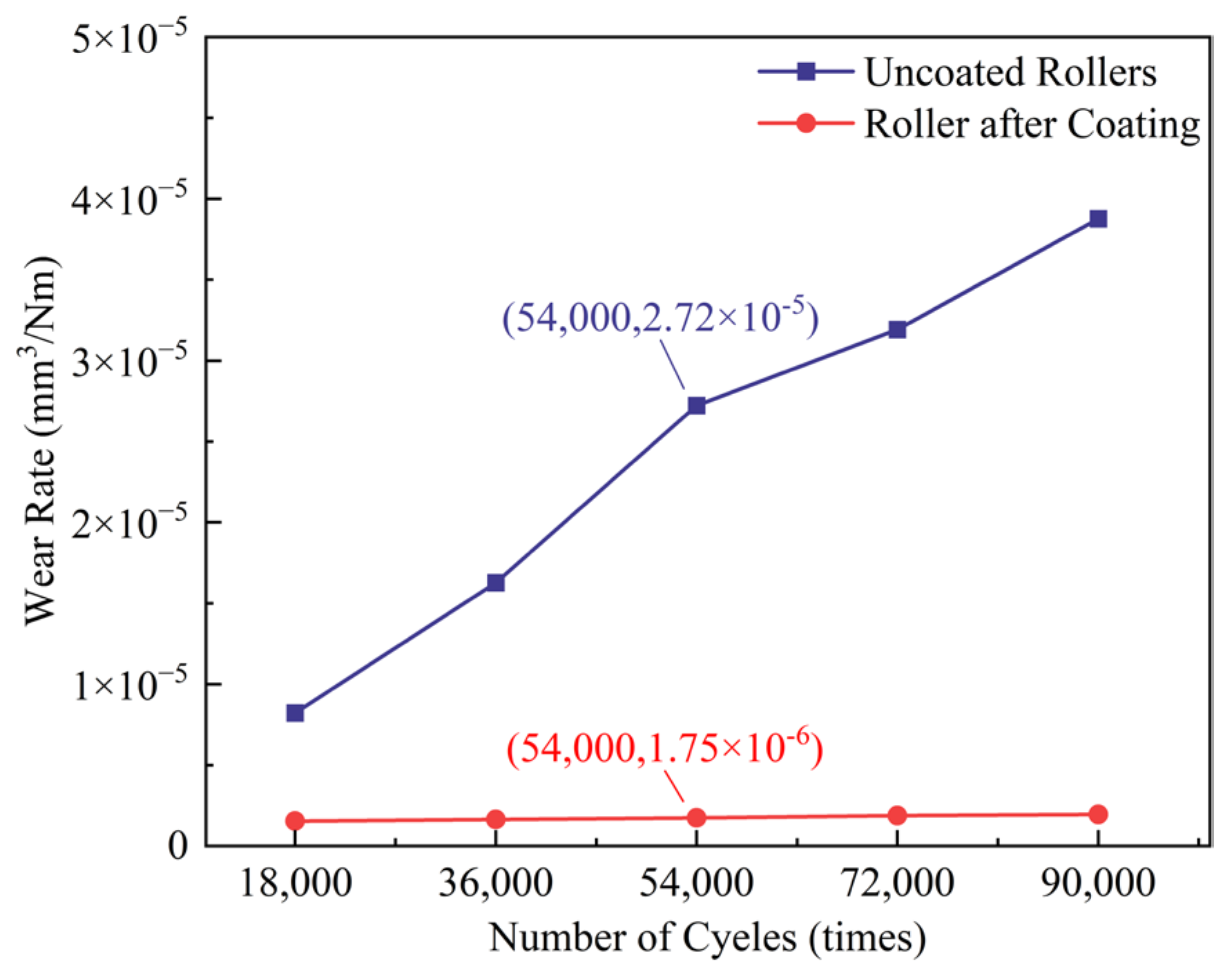

3.3. Number of Cycles

4. Test Verification

4.1. Preparation of Graphite-like Carbon-Based Thin Film Rollers

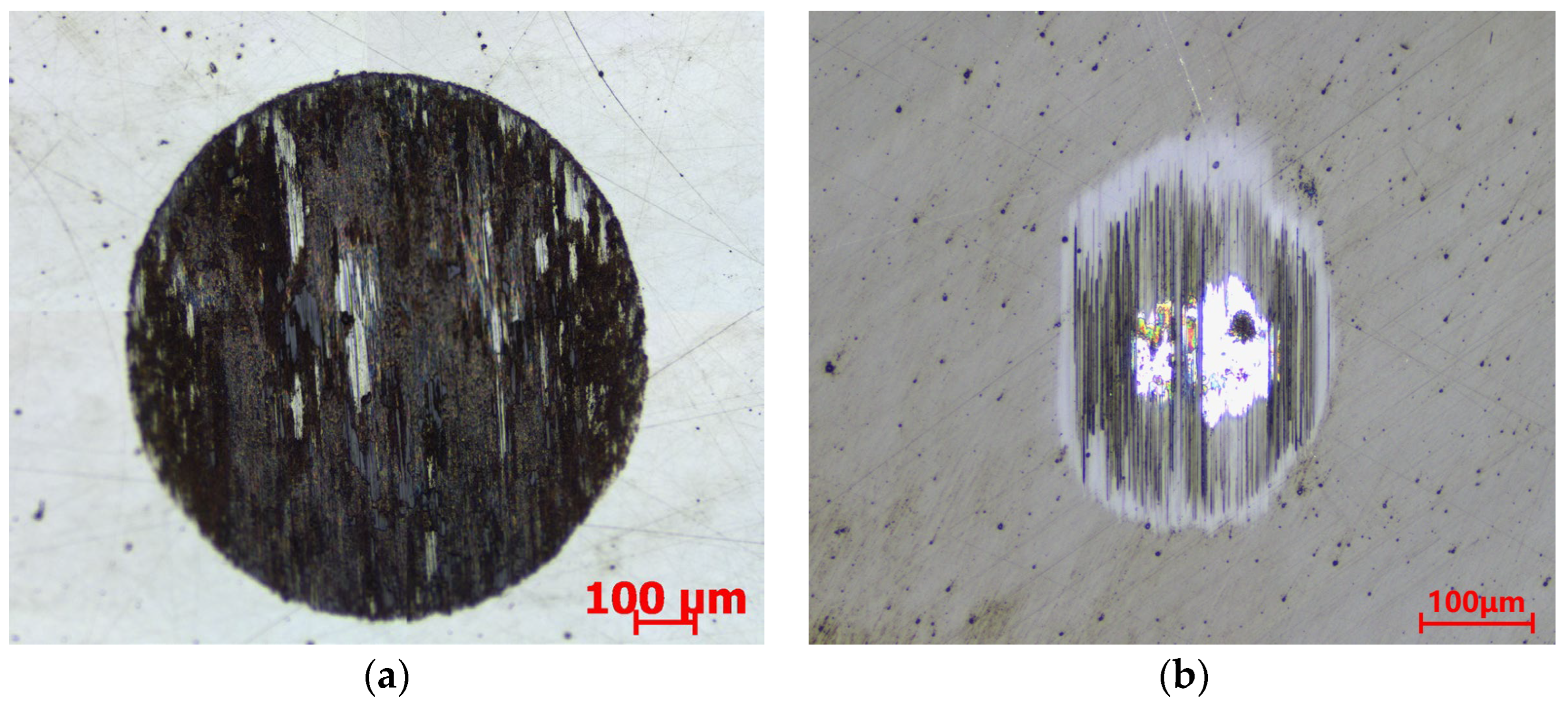

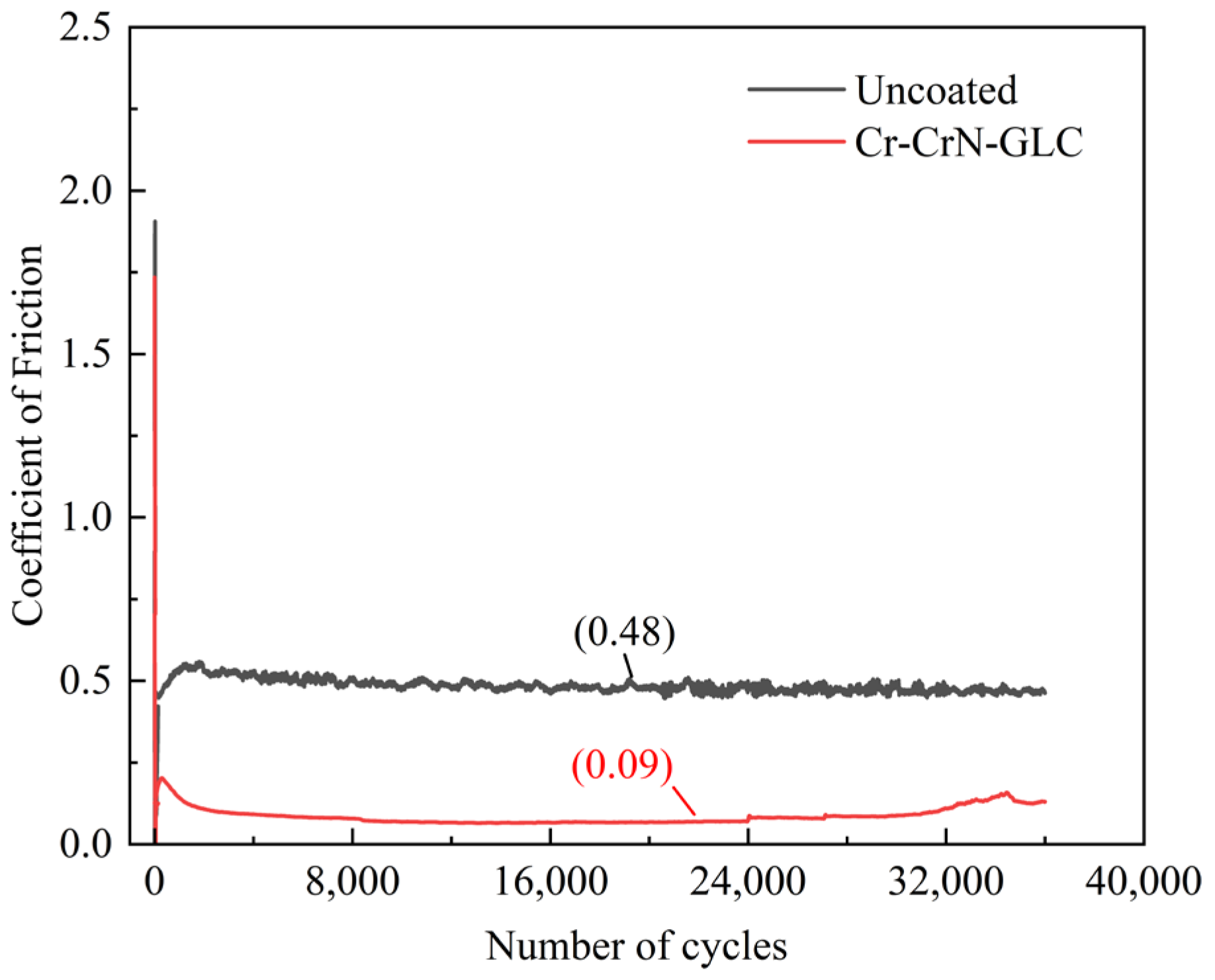

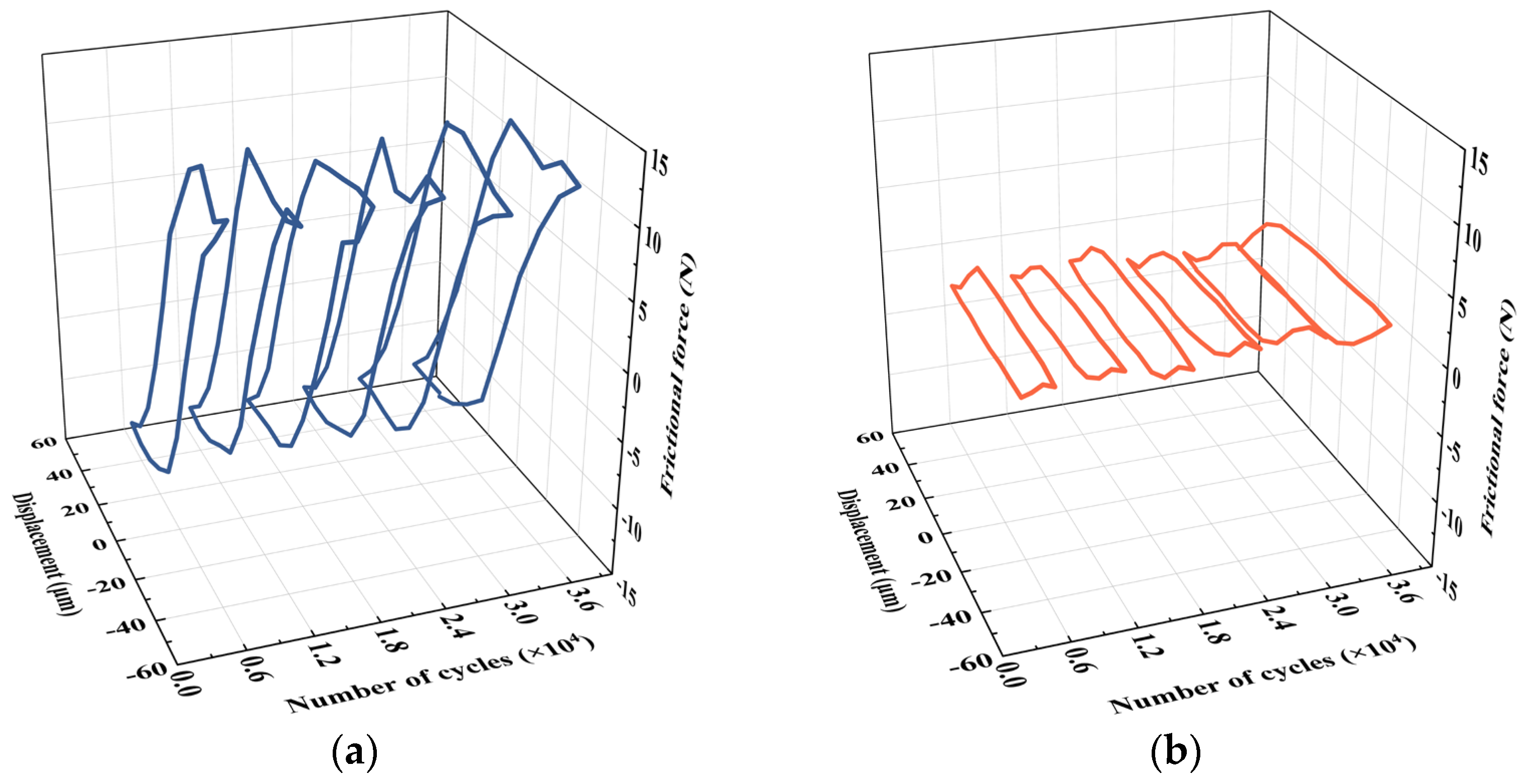

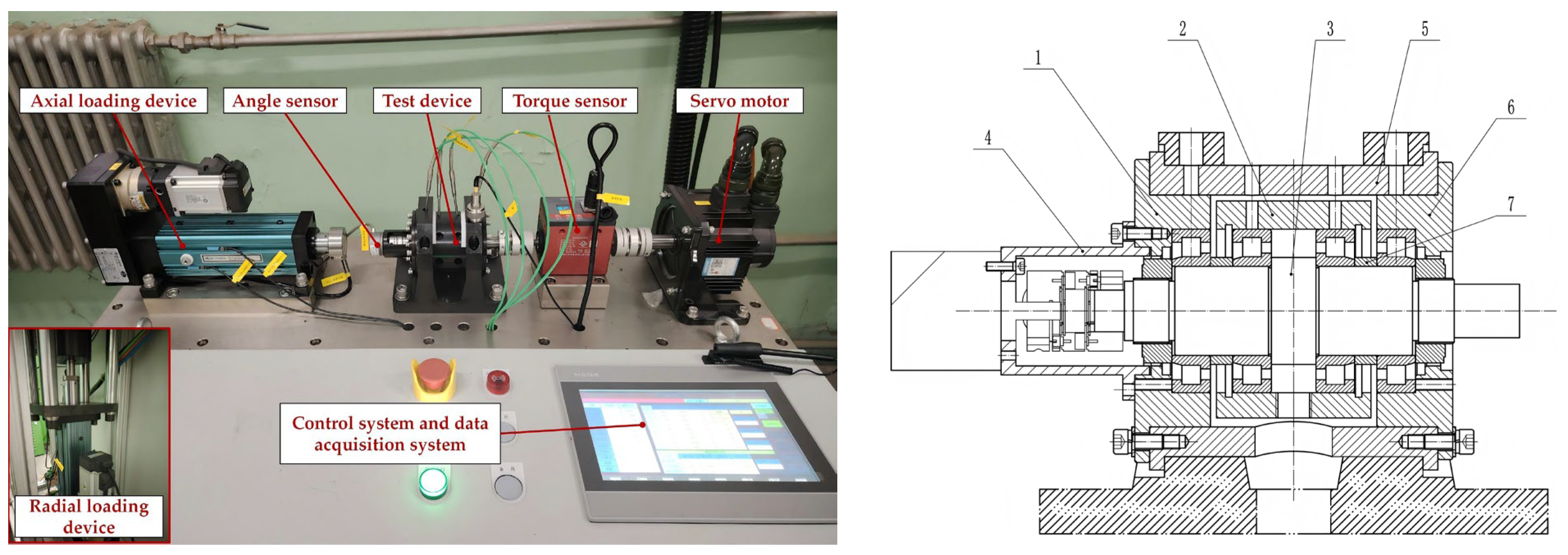

4.2. Micro-Motion Testing

5. Conclusions

- By comparing the ball–disc fretting wear simulation model with experimental results, the wear coefficients of the uncoated and coated roller–inner ring pairs under dry friction were determined to be k1 = 3.125 × 10−8 and k2 = 4.5 × 10−10, respectively.

- With increasing normal load (Fn), the maximum wear depth and width of both coated and uncoated raceways increase gradually, with the uncoated raceways exhibiting greater sensitivity to load variations. After coating, the wear rate is reduced by approximately one order of magnitude and demonstrates improved stability. Displacement amplitude (D) has a relatively minor influence on the maximum wear depth for both coated and uncoated rollers, whereas wear width increases progressively with displacement amplitude. Compared to the uncoated condition, the average wear depth after coating with GLC film is reduced by approximately 90.56%. As the number of loading cycles (N) increases, wear scar morphology evolves, exhibiting blurred boundaries, delamination, and spalling. The wear evolution of the rollers and inner rings after being coated with GLC film is relatively stable, indicating that the GLC film has good anti-fretting wear performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Novaković, B.; Radovanović, L.; Vidaković, D.; Đorđević, L.; Radišić, B. Evaluating wind turbine power plant reliability through fault tree analysis. Appl. Eng. Lett. 2023, 8, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazović, T.; Marinković, A.; Atanasovska, I.; Sedak, M.; Stojanović, B. From innovation to standardization—A century of rolling bearing life formula. Machines 2024, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Zhao, D.; Shangguan, L. Review of wind power bearing wear analysis and intelligent lubrication Method research. Coatings 2023, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xia, X.T.; Qiu, M. Analysis and Control of Fretting Wear for Blade Bearing in Wind Turbine. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2010, 26–28, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Cause Analysis and Preventive Measures for Fretting Wear of Doubly-F’ed Wind Turbine Rotor Shaft. Bearing 2024, 9, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, H.D.M.; Araújo, A.M.; Bouchonneau, N. A review of wind turbine bearing condition monitoring: State of the art and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillas, D.; Olave, M.; Llavori, I.; Ulacia, I.; Larrañaga, J.; Zurutuza, A.; Lopez, A. A novel formulation for radial fretting wear: Application to false brinelling in thrust bearings. Wear 2022, 488, 204078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.H.; Zhou, Z.R. On the mechanisms of various fretting wear modes. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.A. Fretting-fatigue damage-factor determination. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 1965, 87, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sadeghi, F. Effects of fretting wear on rolling contact fatigue. Tribol. Int. 2024, 192, 109204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, B.; Balak, V.; Carboga, C. Dry sliding wear behavior of boron-doped AISI 1020 steels. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2017, 132, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, Y.H. Effects of displacement amplitude on fretting wear behaviors and mechanism of Inconel 600 alloy. Wear 2013, 304, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, E.H.; Long, H. Fretting wear in raceway-ball contact under wind turbine pitch bearing operating conditions. Wear 2025, 564, 205696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.M.; Li, X.; Yan, H.N. Simulation and experimental study of titanium alloy fretting wear under alternating biaxial loading. Mech. Electr. Eng. 2024, 41, 1251–1259+1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Yang, M.; Shu, B. Fretting wear behaviour of high-nitrogen stainless bearing steel under lubrication condition: H. Lin et al. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2020, 27, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Eom, K.; Geringer, J. Literature review on fretting wear and contact mechanics of tribological coatings. Coatings 2019, 9, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.H.; Cai, Z.B.; Zhou, Z.R. Fretting Wear under Special Conditions; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 212–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, A.N.; Li, Y.C.; Fan, H.H. High Temperature Tribological Properties of Ti-GLC Films Deposited on Different Bearing Steel Substrates. China Surf. Eng. 2022, 35, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.R. Research on The Dynamic Contact Behavior of Amorphous Carbon Filmsat Micro/Nano Scale. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2021; pp. 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; He, W.; Xu, L.; Zhang, G.A.; Nie, X.; Liao, B.; Li, Y. Tribological performance of GLC, WC/GLC and TiN films on the carburized M50NiL steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 361, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Yang, G.S.; Yang, M.X. Influence of Modulation Periodicity on Tribo-corrosion Properties of Magnetron-sputtered Film Consisting of Multiple Alternating Layers of Cr and Graphite-like Carbon. Mater. Rev. 2024, 38, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y. Effect of the graphitization mechanism on the friction and wear behavior of DLC films based on molecular dynamics simulations. Langmuir 2023, 39, 1905–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.H.; Fridrici, V.; Geringer, J. Influence of diamond-like carbon coatings and roughness on fretting behaviors of Ti–6Al–4V for neck adapter–femoral stem contact. Wear 2018, 406, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xue, Q. Influence of Ti target current on microstructure and properties of Ti-doped graphite-like carbon films. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinedo, B.; Mendoza, G.; López-Ortega, A. Tribological investigation on WC/C coatings applied on bearings subjected to fretting wear. Tribol. Lett. 2024, 72, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Wang, Y.X.; Chen, K.X. Effect of Cr Doping on the Microstructure and Tribological Performances of Graphite -like Carbon Films. Chin. J. Tribol. 2015, 32, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F. Study on Fretting Wear Behavior of Titanium Alloy in Aero-Engine. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, A.; Yoon, C.; Caruana, J. Development of an Advanced Wear Simulation Model for a Racing Slick Tire Under Dynamic Acceleration Loading. Machines 2025, 13, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Zheng, M. Study on Friction and Wear Performance of Bionic Function Surface in High-Speed Ball Milling. Machines 2025, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storchak, M.; Melnyk, O.; Stepchyn, Y. Effect of Friction Model Type on Tool Wear Prediction in Machining. Machines 2025, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Xue, Y. A Study on the Wear Characteristics of a Point Contact Pair of Angular Contact Ball Bearings Under Mixed Lubrication. Machines 2025, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Chen, J.; Gao, X.H. Numerical Simulation of Radial Fretting Behaviors on Wind Turbine Slewing Bearings. Mach. Des. Manuf. 2013, 8, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, M.; Ramalho, A.; Ramos, F. Electrical performance of textured stainless steel under fretting. Tribol. Int. 2017, 110, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.H.; Chen, F.H.; Cai, Z.B. Fretting Wear Properties of Laser-cladded MoNbTaVW Refractory High-entropy Alloy Coatings. Mater. Rev. 2024, 38, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrbacher, H.; Blanpain, B.; Celis, J.P. Oxidational wear of TiN coatings on tool steel and nitrided tool steel in unlubricated fretting. Wear 1995, 188, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.J.; Yin, D.; Tang, L.C. Numerical Calculation and Analysis of The Effect of Fretting Contact Conditions on The Wear Rate of Zircaloy. Eng. Mech. 2016, 33, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.M.; Shi, X.H.; Xu, M.H. Analysis of Fretting Wear and Fretting Protection for Wind Turbine Pitch Bearing. Lubr. Eng. 2009, 34, 110–112+117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.H.; Ren, Y.P.; He, T. Study on Fretting Wear Behaviour of Plasma Nitriding Layer of 31CrMoV9 Steel. J. Tribol. 2024, 44, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serial Number | Steps | N2 Flow Rate | Cr Target Current (A) | C Target Current (A) | Matrix Bias Voltage (A) | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Substrate cleaning | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 200→400 | 20 |

| 2 | Target cleaning | 0 | 0.3→5 | 0 | 400→120 | 5 |

| 3 | Cr focuses on the bottom layer | 0 | 5 | 0.2 | 120→65 | 10 |

| 4 | CrN/C transition layer | 0 | 5→0.2 | 0.2→5 | 60 | 30 |

| 5 | CrN bearing layer | 90→60 | 5→0.2 | 0.2→5 | 60 | 25 |

| 6 | GLC working layer | 0 | 0.2 | 5 | 60 | 160 |

| Serial Number | Parameter | Numerical Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maximum load/kN | 5 |

| 2 | Maximum stroke in the X direction/mm | 150 |

| 3 | Maximum stroke in the Y direction/mm | 250 |

| 4 | Maximum stroke in the Z direction/mm | 150 |

| 5 | Speed range in the X direction/mm·s−1 | 0.002~6 |

| 6 | Speed range in the Y direction/mm·s−1 | 0.002~50 |

| 7 | Speed range in the Z direction/mm·s−1 | 0.002~10 |

| 8 | Highest frequency/Hz | 70 |

| Part | Material | Density (kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roller | GCr15 | 7.8 × 103 | 210 | 0.3 |

| Inner circle | 42CrMo4 | 7.85 × 103 | 210 | 0.29 |

| GLC Coating | Cr-CrN-GLC | 4.1 × 103 | 175 | 0.2 |

| Serial Number | Parameter | Numerical Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inner Diameter/mm | 30 |

| 2 | Outer Diameter/mm | 55 |

| 3 | Width/mm | 13 |

| 4 | Swing angle/(°) | 0–3 |

| 5 | Swing frequency/Hz | 3 |

| 6 | Loading frequency/Hz | 3 |

| 7 | Radial Load/N | 400–6000 |

| 8 | Loading time/h | 150 |

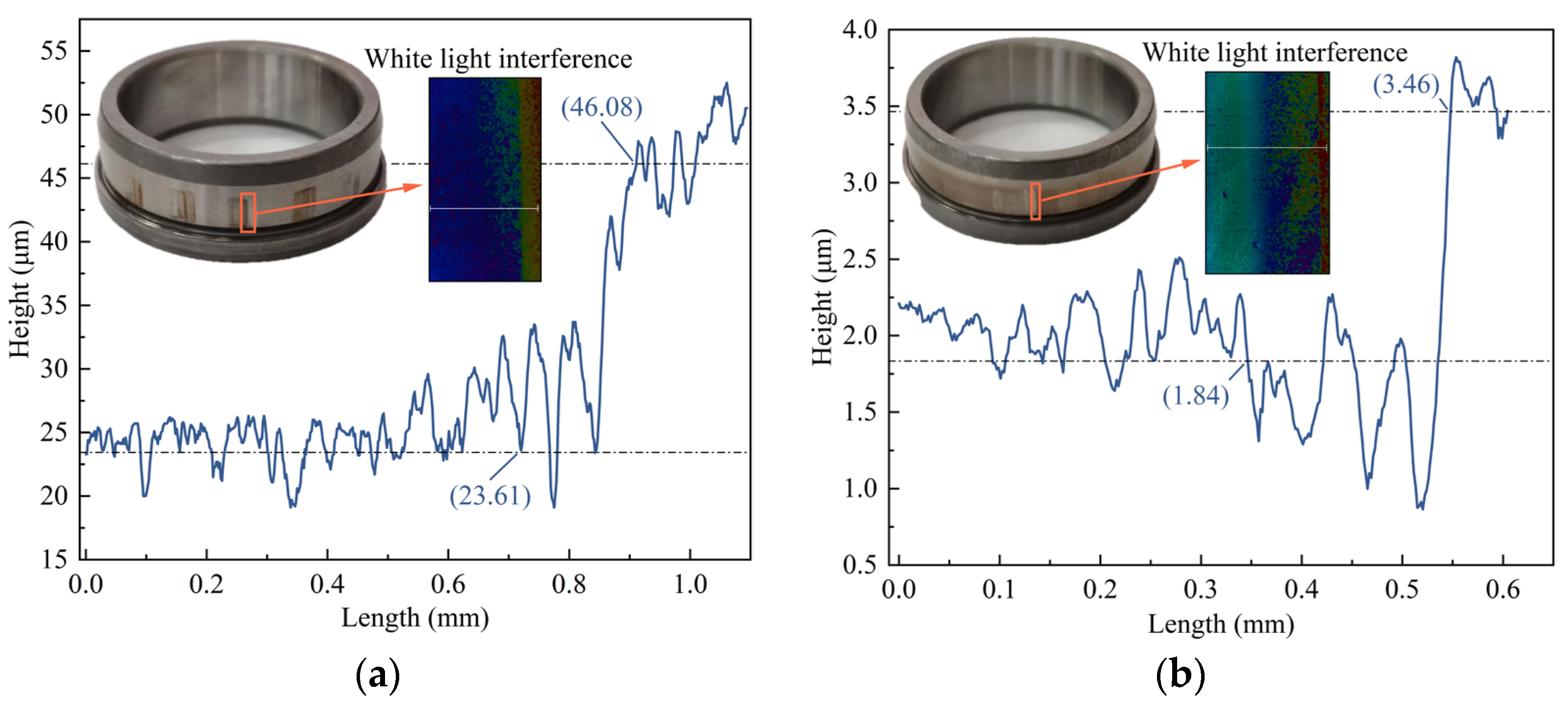

| Serial Number | Coating Condition | Simulation (μm) | Experiment (μm) | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uncoated | 23.29 | 22.47 | 3.65% |

| 2 | Coated | 1.69 | 1.62 | 4.32% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, X.; Zuo, X.; Yang, M.; Zhu, D.; Li, Q.; Jiang, C.; Mao, J. The Role of Graphite-like Carbon Films in Mitigating Fretting Wear of Slewing Bearings. Machines 2025, 13, 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121110

Pang X, Zuo X, Yang M, Zhu D, Li Q, Jiang C, Mao J. The Role of Graphite-like Carbon Films in Mitigating Fretting Wear of Slewing Bearings. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121110

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Xiaoxu, Xu Zuo, Minghao Yang, Dingkang Zhu, Qiaoshuo Li, Chongfeng Jiang, and Jingxi Mao. 2025. "The Role of Graphite-like Carbon Films in Mitigating Fretting Wear of Slewing Bearings" Machines 13, no. 12: 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121110

APA StylePang, X., Zuo, X., Yang, M., Zhu, D., Li, Q., Jiang, C., & Mao, J. (2025). The Role of Graphite-like Carbon Films in Mitigating Fretting Wear of Slewing Bearings. Machines, 13(12), 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121110