1. Introduction

The global railway industry is increasingly prioritizing the optimization of equipment operation and maintenance to ensure the safety, efficiency, and reliability of rail transit systems. As electrified rail networks expand and mature, the focus shifts from new construction to enhancing the performance and longevity of existing infrastructure. Among the critical components, the pantograph-catenary (or rigid conductor) system is fundamental for continuous power supply to electric vehicles [

1], making its intelligent operation and maintenance (IOM) a subject of extensive research and development [

2,

3]. Effective inspection and detection are fundamental to developing IOM and prognostics and health management (PHM) strategies for these systems. In this regard, the requirements for and validation of measurements of the dynamic interaction between pantograph and overhead contact wire are specified in international standards [

4,

5]. Furthermore, national transport authorities in various regions have also defined technical specifications for the assessment of metro and light rail pantograph-catenary systems [

6].

At the implementation level, engineers and scientific researchers worldwide have developed a variety of test schemes for pantograph and catenary (PAC) systems, which can be broadly categorized into contact and non-contact methods. For contact-based approaches, the measurement of contact force can be accomplished by embedding fiber Bragg grating strain gauges into the pantograph strip, leveraging the transfer function of contact force and strain response [

7,

8]. Recently, an optical fiber force sensor specifically designed for pantograph-catenary contact force has been developed and tested, considering various conflicting requirements such as encumbrance, mass, static and fatigue strength, and sensitivity [

9]. The advantages of such devices over classical electrical-based transducers have been analyzed through laboratory and in-line tests. Concurrently, institutions like the Jena Institute of Photonic Technology (IPHT) in Germany have also proposed similar optical fiber sensing technologies for continuous on-site monitoring of contact forces [

10].

Conversely, for non-contact systems, with the universal application of industrial cameras, image processing-based technologies have been widely used in the geometric parameter testing of pantograph-catenary systems. However, these vision-based technologies face inherent challenges in real-world operational environments due to various interferences, including light changes, dynamic backgrounds, foreign object occlusion, and changes in pantograph attitude. To address these complexities, numerous computer vision and machine vision technologies have been employed for detecting and tracking targets from images, including feature-based image matching techniques [

11], edge detection technology [

12], Hough transforms [

13], binocular vision technology [

14], and neural networks [

15,

16]. In 2020, a multi-step detection strategy consisting of real-time tracking, pixel-level detection, and filter-based optimization modules for extracting the contact point of pantograph and catenary system was proposed [

17]. This strategy employed kernel correlation filters, contact point regression residual networks, and Kalman filters to ensure the robustness and real-time performance of the recognition algorithm.

With the increasing maturity of data mining and big data technologies, the cross-application of contact and non-contact equipment has also grown. For example, measurements from acceleration sensors have been used to identify catenary wavelength [

18] and to perform condition-based monitoring of overhead catenary [

19]. Inversely, image processing technologies have been applied to predict pantograph-catenary contact force [

20], as well as arcing [

21]. Such integrated approaches are highly desirable for rail operators seeking to optimize equipment operation and maintenance.

Despite these advancements, significant research gaps persist in accurately predicting the dynamic stagger of Overhead Rigid Conductor Systems (ORCS) and precisely locating their section overlaps using cost-effective and robust contact-based measurements. While traditional methods for stagger measurement have predominantly relied on visual inspection systems [

22], these are susceptible to environmental interferences and can incur high operational costs. The accurate knowledge of dynamic stagger is crucial for understanding and predicting the wear profile of the pantograph strip [

23,

24], thereby enabling the identification of abnormal wear positions and proactive maintenance to prevent costly failures and ensure operational safety.

Abnormal wear events in PAC systems, observed in various urban rail networks, underscore the urgent need for improved monitoring techniques. This emphasis on the need for accurate dynamic stagger data directly relates to the prediction of pantograph strip wear and the implementation of proactive maintenance strategies, thereby significantly enhancing the safety and economic efficiency of railway operations. Thus, the significance of this research extends beyond purely academic interest, offering solutions to critical safety and economic issues in practical operations. Given the novelty of this integrated approach, there is a notable absence of directly related prior work that simultaneously addresses dynamic stagger prediction and overlap localization using force measurements in this specific context.

To address the aforementioned critical gaps, this paper proposes a novel data processing framework that utilizes force transducer measurements from pantograph strip brackets to predict dynamic stagger for ORCS, as well as to locate ORCS section overlaps. Our primary goal is to predict the distribution of dynamic stagger by using the bracket force on both sides of a pantograph strip. To achieve this, two key objectives are pursued: (1) to precisely identify single-point and two-point contact states during the sliding friction between the pantograph and contact wire, which is essential for determining the position of rigid conductor section overlap, and (2) to predict the contact wire stagger with high precision in the single-point contact area within a rigid conductor section. For the first issue, we employ peak analysis technology on the minimum and maximum components of a difference matrix. This matrix is the result of the difference operator on the predictive stagger that uses the bracket force of the pantograph strip as input. For the latter, we first deduce the theoretical formula of stagger under the quasi-static assumption for a moving load problem, and then carefully set up a Butterworth filter to remove the pulsation in the calculated stagger.

From an application perspective, our research offers a significant contribution by enabling the acquisition of dynamic stagger information from contact-type sensors. This innovation holds the potential to replace expensive industrial cameras for pantograph and catenary monitoring, thereby substantially improving the cost-effectiveness and robustness of condition monitoring equipment used by rail operators. In practical operation, the predicted stagger can serve also as a data-quality and sensor-health indicator: persistent or systematic discrepancies between the predicted stagger and independently measured geometry (e.g., from video-based inspection) can flag sensor malfunction, installation drift, or data-acquisition anomalies and thus trigger targeted inspection or recalibration. In addition, the predicted stagger probability distribution can assist maintenance prioritization by identifying locations with higher likelihood of extreme stagger and associated pantograph-strip wear. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

Novel Integrated Framework: We introduce a pioneering data processing framework that uniquely combines force transducer measurements, a beam model, sophisticated peak analysis, and zero-phase filtering to simultaneously predict dynamic stagger and precisely locate section overlaps in ORCS. This integrated approach offers a unified and comprehensive solution to a complex, multi-faceted engineering challenge.

Cost-Effective and Robust Alternative: Our methodology provides a robust and economically viable alternative to traditional, often expensive and environmentally sensitive, visual inspection systems. By leveraging readily available force measurements, the framework significantly reduces operational costs and enhances reliability in diverse environmental conditions, directly benefiting rail operators.

Enhanced Predictive Maintenance Capabilities: The accurate prediction of dynamic stagger is critical for understanding pantograph strip wear profiles, enabling proactive identification of abnormal wear positions. This capability facilitates timely maintenance interventions, preventing costly failures, extending equipment lifespan, and ensuring the continuous operational safety of rail transit systems.

Demonstrated Versatility Across ORCS Geometries: Through rigorous experimental validation on real-world data from both triangular and sinusoidal ORCS layouts, the framework has proven its exceptional applicability and accuracy. The adaptive nature of our kurtosis-based optimization ensures its effectiveness across varying ORCS designs, highlighting its broad utility in diverse railway networks.

Advancement in Measurement and Instrumentation: This research significantly advances the field of railway measurement and instrumentation by introducing a novel and highly effective method for dynamic stagger measurement. It enriches the scope of measurement science and technology within rail transit applications, proposing a new framework for condition monitoring solutions.

A systematic comparison among existing stagger monitoring strategies is summarized in

Table 1. Traditional vision-based methods using industrial cameras are costly and highly sensitive to lighting and dust, requiring regular calibration and protected installation [

17,

25,

26]. Accelerometer/force hybrid schemes provide richer dynamic information but often involve multi-sensor synchronization and additional wiring, increasing maintenance complexity [

18,

27]. In contrast, the present approach relies solely on bracket-force measurements, offering a compact, low-cost, and lighting-independent alternative suitable for confined or poorly illuminated sections [

28,

29]. The quantitative parameters are compiled from representative references in the field. The table highlights that the proposed method provides the best trade-off between cost, environmental robustness, spatio-temporal accuracy, and ease of deployment, making it suitable for large-scale, harsh-environment applications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details the problem setup, including the characteristics of ORCS and the fundamental mechanical model.

Section 3 elaborates on the proposed methodology and its implementation, covering stagger variation analysis, zero-phase filtering, and peak analysis for overlap identification.

Section 4 and

Section 5 present the experimental validation results using field test data from ORCS with triangular and sinusoidal stagger layouts, respectively. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings and outlining directions for future work.

2. Problem Setup

Accurate measurement and prediction of dynamic stagger and precise localization of section overlaps are paramount for ensuring the safety, operational efficiency, and predictive maintenance of electrified rail transit systems. Deviations in stagger can lead to uneven wear of pantograph strips and contact wires, potentially causing abnormal wear events and compromising current collection quality. Traditional visual inspection systems, while capable of geometric measurements, often struggle with robustness in varying environmental conditions (e.g., light changes, occlusions) and can incur high operational costs. This necessitates the exploration of alternative, more resilient, and cost-effective monitoring solutions.

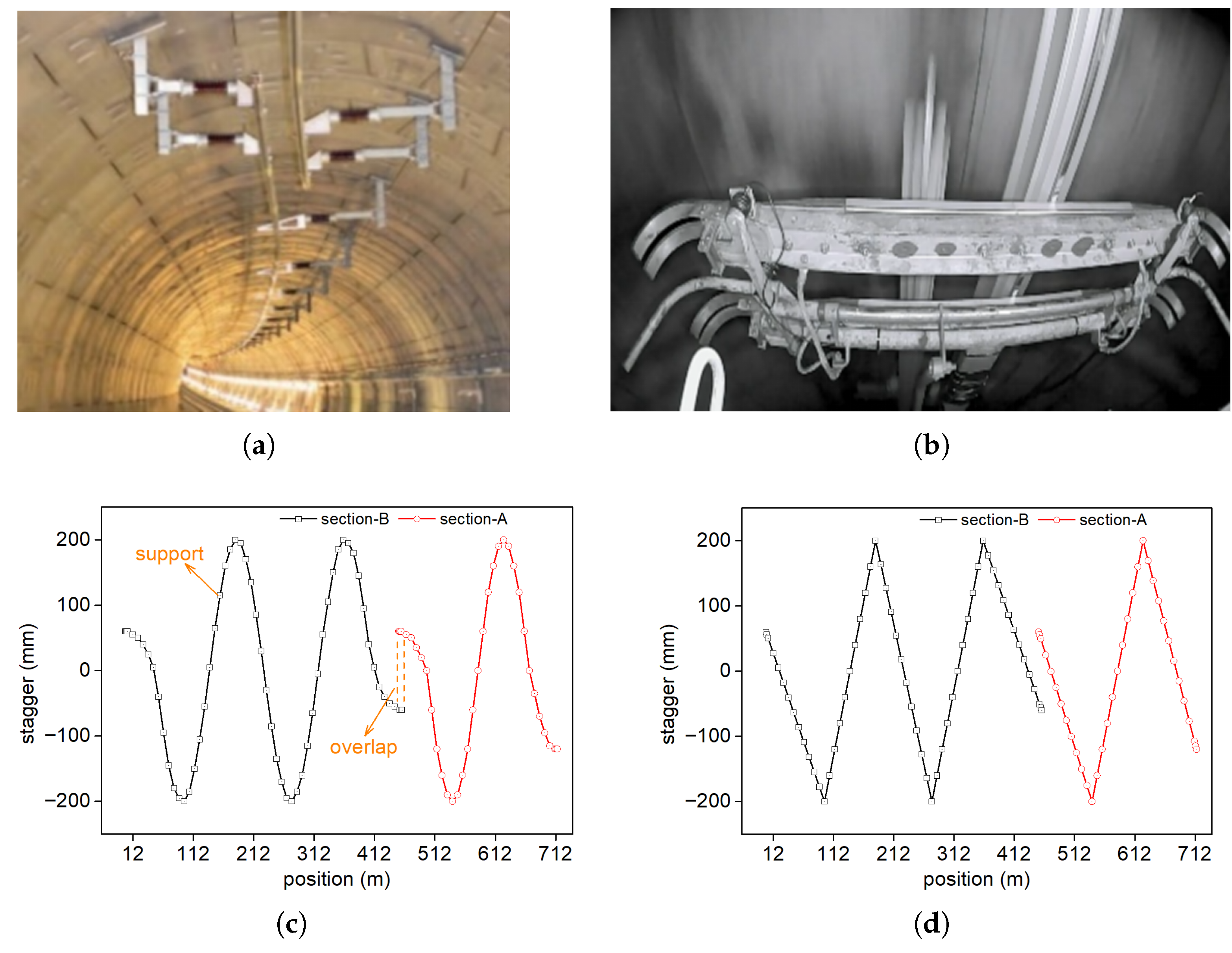

The Overhead Rigid Conductor System (ORCS) is widely adopted in urban rail transit networks (

Figure 1a). It comprises a rigid conductor rail, typically an extruded aluminum alloy profile, to which the contact wire is clamped on the underside. Along a railway line, the ORCS is composed of multiple conductor rail sections, varying in length from tens to hundreds of meters. Adjacent sections are connected through an overlapped area (

Figure 1b), where a clearance, typically ranging from 120 mm to 260 mm, is maintained between the closest edges of the two conductor rails to provide electrical sectioning.

The stagger layout of rigid conductors or contact wires commonly features two primary types: triangular waveform and sinusoidal waveform.

Figure 1c,d illustrate how these two layouts vary with chainage. As the pantograph traverses an overlap section in the direction of increasing chainage, the contact wire on one side (e.g., with negative stagger) exits the pantograph strip zone, while the contact wire on the other side (e.g., with positive stagger) enters it. In practical applications, both L-in-R-out (left-in-right-out) and R-in-L-out (right-in-left-out) overlap arrangements are utilized (

Figure 1b). These two distinct stagger layouts, and their visual identification differences (e.g., the visually challenging overlap points in sinusoidal waveform layouts), highlight the limitations of traditional or simple measurement methods and underscore the necessity of developing a robust algorithmic solution capable of adapting to various ORCS geometries.

Affected by the elastic distribution of the conductor rail [

30], vehicle vibration, and the dynamic interaction between the pantograph and the catenary [

31], the pantograph response usually exhibits dynamic oscillations, which are commonly observed in rail transit systems [

32,

33].

Figure 2 illustrates the variations in the left and right bracket forces of a pantograph strip over time under triangular and sinusoidal waveform inputs. Due to the zig-zag arrangement of the contact wire, the contact point moves laterally along the pantograph strip, resulting in alternating changes of the left and right bracket forces. Therefore, the dynamic stagger of the contact wire can be inferred from such bracket force signals.

To establish a foundational understanding of the relationship between bracket forces and stagger, we consider a simplified beam model for the pantograph strip under a moving load (

Figure 3). By initially ignoring dynamic effects and adopting a quasi-static assumption, the position

y and magnitude

of the load can be deduced from the left (

) and right (

) bracket forces through a straightforward mechanical analysis:

where

y represents the lateral position of the contact point on the pantograph strip,

and

are the forces measured by the left and right bracket force transducers, respectively, and

L is the effective length of the pantograph strip.

denotes the total contact force. The primary geometric variables are defined using SI units (meters, m):

y (stagger position),

L (effective strip length), and

d (overlap clearance). Throughout this paper, the sign convention is established such that the right side of the contact wire/pantograph strip is defined as positive (

), and the left side is negative.

Equations (

1) and (

2) are derived under a quasi-static assumption. Consequently, this work does not utilize these formulas to establish a direct, bijective mapping between bracket forces and dynamic stagger under high-frequency vibration or transient conditions (a pursuit reserved for future research). Instead, it provides a physics-based entry point for the data-driven stagger calculation method, supplying the fundamental calculational rules that, when augmented by low-pass filtering, enable the robust extraction of geometric trends. It also offers theoretical insight into the characteristic step-changes of bracket forces occurring at rigid conductor section overlaps, thereby providing a cognitive basis to guide the parameter tuning and optimization of the peak-identification process.

Applying this beam model to a real-world pantograph-catenary system allows for the direct calculation of contact wire stagger from the pantograph strip’s bracket forces using Equation (

1). However, achieving high-precision stagger prediction in practical scenarios necessitates addressing two primary challenges:

Accurately locating the position of rigid conductor section overlaps;

Effectively removing the oscillating components present in the calculated stagger signals, which arise from dynamic interactions and noise.

It is worth noting that this initial quasi-static assumption, while simplifying the mechanical modeling and making the derivation of the stagger formula straightforward, simultaneously introduces discrepancies with real-world dynamic effects. Therefore, the subsequent effective removal of oscillating components from the calculated stagger signal is not merely simple noise processing but a necessary compensation for the impact of this model simplification, reflecting a sophisticated engineering consideration in balancing simplification with practical complexity in system modeling.

3. Methodology and Implementation

This section presents our proposed data processing framework for predicting ORCS stagger and identifying section overlaps using pantograph bracket force measurements. Building upon the challenges identified in

Section 2, particularly the need for accurate overlap localization and effective noise reduction in stagger signals, this framework systematically transforms raw force data into precise stagger information and robust overlap detections, integrating theoretical analysis with advanced signal processing techniques.

3.1. Stagger Variation Analysis Within Overlaps

The analysis of stagger variation within ORCS overlaps is fundamental to understanding the characteristic signatures that enable overlap identification.

Figure 4 illustrates two distinct cases as a pantograph traverses an ORCS overlap. For the L-in-R-out scenario depicted in

Figure 4, assuming quasi-static conditions, we can analyze the stagger at different contact states.

When the pantograph strip contacts the contact wire at one single point (

), the stagger

is given by

where

is the stagger at time

, and

and

are the right and left bracket forces at time

, respectively.

When two contact points are present (

), if

represents the stagger difference caused by the zig-zag layout at different positions of the same contact wire, then the stagger

can be expressed as

It is crucial to note that applying Equation (

1) to calculate stagger in a two-point contact scenario implicitly assumes a single equivalent external force at the current position. Based on the equivalence principle of spatial forces, the application point

of the equivalent force corresponding to

and

can be expressed in relation to

:

where

and

are the right and left bracket forces at time

,

and

are the contact forces at the two contact points, and

d is the clearance between the two conductor rails in the overlap.

The proportion of

to the total force

can be defined as

:

Then

can be expressed as

Upon returning to single-point contact (

), the stagger

of the newly entering contact wire is

where

and

are the right and left bracket forces at time

.

Using Equations (

3), (

7) and (

8), we further analyze the stagger variance induced by changes in the number of contact points, which is instrumental for locating rigid conductor overlap position. When contact transitions from single-point to two-point, the stagger variance is determined by subtracting Equation (

3) from Equation (

7):

Conversely, when returning to single-point contact from two-point contact, by subtracting Equation (

7) from Equation (

8), the stagger variance is

Similarly, for the left-out-right-in case (also shown in

Figure 4), the stagger variance caused by the change in contact point number can be derived as

From Equations (

9)–(

12), several critical insights were derived:

(1) Regardless of whether it is a L-in-R-out or left-out-right-in case, when the contact switches from a single point to two points and then restores, the sum of stagger variance is , where d is the clearance between the two conductor rails in the overlap.

(2) Within the section overlap, two-point contact states persist for a certain duration. Since and vary simultaneously with mileage, this results in a distinct variance pattern of the calculated stagger within continuous two-point contact states. This kind of stagger variance is not always smaller than the variance caused by the contact points number switching.

Equation (

7) also implies that:

(3) At the precise moment of switching from single-point to two-point contact, the calculated stagger will deflect towards the side where the new contact wire has entered. If and d have different signs, the concavity or convexity of the calculated stagger curve at the overlap will remain unchanged; otherwise, it will change. These characteristic deflections form the basis for algorithmic overlap detection.

3.2. Zero-Phase Filter for Calculated Stagger

The analysis presented in

Section 3.1 is based on the quasi-static assumption, which simplifies the mechanical interaction. However, real-world measurements are inherently affected by dynamic phenomena, such as vehicle vibrations and the elastic response of the catenary system. To accurately extract the underlying stagger signal and prepare it for robust analysis, it is essential to filter out these dynamic fluctuations and noise.

For this purpose, we employ a discrete-time filter. The selection principle for such a filter involves determining a system (characterized by a transfer function or difference equation) that approximates a desired impulse or frequency response within a specified tolerance. Filters can be broadly classified into infinite impulse response (IIR) and finite impulse response (FIR) systems. Considering their phase characteristics and design complexity, we chose the IIR Butterworth low-pass filter as the primary filtering tool in this work.

For the employed low-pass filter, the stopband frequency is set to achieve an amplitude attenuation of 60 dB, corresponding to a tolerance . For the passband frequency, we define , where is the frequency at which the response power is attenuated by half, resulting in an amplitude attenuation to 0.7079, corresponding to .

To eliminate the phase delay introduced by the filter, which is critical for preserving the accurate spatial (and thus temporal) positioning of stagger deflections and overlap points, zero-phase filtering technology is adopted. This technique ensures that the filtered signal’s features, such as the characteristic deflections at overlap sections, remain perfectly aligned with their original physical locations without artificial temporal shifts. In a measurement system where physical localization is paramount, any temporal distortion would directly translate into spatial errors, making zero-phase filtering a critical design choice for ensuring measurement accuracy. The process involves:

Filtering the input signal in the forward direction (forward filter);

Reversing the obtained result and passing it through the filter again (reverse filter);

Reversing the newly obtained result back to its original orientation (reverse output).

This forward and reverse filtering process can be mathematically represented as

where

represents the input signal in the discrete time domain,

is the impulse response of the filter,

N is the length of the signal, and

are their respective Discrete Fourier Transforms (DFT) in the frequency domain.

Ultimately, we obtain:

which confirms that the output signal exhibits zero-phase distortion, and the effective transfer function of the zero-phase filter is equivalent to the squared magnitude of the original filter’s transfer function. This ensures that the filtered stagger signal accurately reflects the true physical stagger without any temporal displacement.

3.3. Peak Analysis for Overlap Identification

The filtered stagger signals, while cleaner, still contain various peaks arising from different factors. To accurately identify the specific peaks corresponding to ORCS section overlaps, a robust peak analysis methodology is employed. Peaks can be characterized by several eigen attributes, including width, height, threshold, distance, prominence, and so on (

Figure 5). In this work, we primarily utilize peak distance and peak prominence to distinguish relevant peaks and precisely locate overlap positions within the predicted stagger history.

Peak prominence quantifies how much a peak stands out relative to its surrounding signal, considering both its intrinsic height and its local context. An isolated low peak can be more prominent than a higher peak that is part of a generally high signal range. To measure the prominence of a peak, a horizontal line is extended from the peak to both the left and right until it intersects the original signal curve (either due to a higher peak or the signal endpoint). This defines two intervals around the peak. The prominence is then determined by the vertical distance between the peak point and the higher of the minimum values found within these two intervals.

We apply this peak analysis to the stagger difference signals (derived from Equations (

9)–(

12)) to identify the location of section overlaps. As discussed in

Section 3.1, the variance of predicted stagger within continuous two-point contact states can sometimes be comparable to or even larger than the variance caused by the switching of contact points. To effectively distinguish the effects of

(stagger difference) and

(force proportion), we introduce the length of the signal segment

N as an additional parameter for the difference operator. For a given maximum lag

N (in samples), we construct a difference matrix

as follows:

where

denotes the filtered predicted stagger signal at sample

t, and

L is the total signal length. Each row of

captures the incremental changes from position

t over distances ranging from 1 to

N samples.

The kurtosis of the difference result is then used to determine the optimal length, . Kurtosis, a measure of the “tailedness” of a probability distribution, is particularly effective here because it quantifies the sharpness of the peaks in the difference signal. A higher kurtosis indicates a more distinct and isolated peak, which is characteristic of the sharp transitions occurring at overlap boundaries, while suppressing the more continuous variations caused by and within the overlap. This allows for a more precise identification of the true overlap-induced changes. Here we use the biased excess kurtosis, computed on standardized windows as , where is the k-th central moment in the window. This combined approach of difference matrix and kurtosis optimization represents a sophisticated signal processing strategy designed to precisely identify true overlap events from complex signal variations, surpassing the capabilities of simple peak detection.

Once is determined, loop differences are performed on the predictive stagger for all lengths less than . This process generates a difference matrix, where rows correspond to sample points and columns correspond to the lengths of the difference operator (less than ). Finally, the minimum and maximum components of this difference matrix are extracted and used as input for the peak analysis algorithm.

3.4. Implementation

The overall data processing framework for predicting ORCS stagger using bracket force measurements is systematically illustrated in

Figure 6. The implementation follows a sequential, multi-step approach:

Initial Stagger Calculation: The dynamic stagger is initially calculated using Equation (

1), assuming a single-point contact between the pantograph and the contact wire along the entire ORCS. This provides a raw stagger signal.

Pulsation Removal: The calculated stagger signal is then processed to remove dynamic pulsations and noise using the zero-phase Butterworth filter, as detailed in

Section 3.2. This step yields a smoothed and more accurate stagger history.

Difference Matrix Generation: For each sampling point

, the difference between

and each point in the segment

of the predictive stagger is calculated with a predefined segment length

N. The optimal difference length,

, is determined by analyzing the kurtosis of the difference results, as described in

Section 3.3. The corresponding difference matrix, which captures characteristic changes in stagger, is then saved.

Difference Array Extraction: The maximum and minimum values of each row in the generated difference matrix are calculated. This results in two distinct difference arrays, which are synchronized with the stagger timestamp. These arrays highlight potential overlap locations.

Overlap Center Determination: Peak analysis is performed on both the maximum and minimum difference arrays. This step identifies prominent peaks that correspond to the center of overlap sections, distinguishing between L-in-R-out and R-in-L-out cases based on the sign of the peak.

Overlap Boundary Determination: Building upon the identified overlap centers, further peak analysis with adjusted settings is applied to precisely determine the start and end points of each overlap section.

Stagger Segmentation: Finally, the stagger data is segmented based on the identified overlap boundaries, allowing for the extraction and analysis of stagger within individual ORCS sections.

3.5. Time Complexity

The most computationally intensive procedure is the Difference Matrix Generation and Kurtosis Optimization. This process involves computing the difference matrix

D and subsequently calculating the kurtosis for

difference vectors, leading to a time complexity

T of

Since the maximum search length is a small, predefined constant (e.g., 50), the entire framework, including filtering and peak analysis, exhibits an effectively linear time complexity with respect to the signal length, which is highly suitable for large-scale application. The primary memory requirement S is dominated by the storage of the difference matrix . Thus, the memory usage is linearly related to the number of samples: .

3.6. Parameter Settings

To ensure reproducibility of the low-pass filter, the raw bracket-force signals were sampled at and the filter specifications (passband , stopband , and the required 60 dB attenuation) were supplied to MATLAB’s built-in design routines, which automatically computed the internal coefficients. The filter was realized as a fifth-order Butterworth low-pass and applied in zero-phase form using filtfilt() to avoid group-delay distortion. Based on the observed dynamics of the pantograph–rigid-catenary interaction (for example, the dominant excitation frequency is below 5 Hz under 80 km/h and 6 m span), the stopband edge was fixed at while the passband edge was tuned in the range 0.2–2 Hz according to the measurement section and dominant vibration content.

For the search and peak detection stages we used the following practical defaults and grid ranges. The maximum difference segment search length () was fixed at 50 (Triangular) or 100 (Sinusoidal) samples with a step size of 1 sample. The grid search for the optimal Peak Prominence was conducted in the range of to with a step of . The Minimum Peak Distance was set based on the shortest expected ORCS support spacing.

4. Experiments on Triangular ORCS Layout

This section details the experimental validation of the proposed data processing framework using field test data acquired from a representative urban rail transit line featuring a triangular ORCS stagger layout. The analysis focuses on optimizing key algorithmic parameters and rigorously assessing the framework’s performance against measured data. The bracket forces ( and ) were measured using proprietary transducers installed on the pantograph strip bracket seat. The system was validated at vehicle speeds ranging from 60 km/h (16.67 m/s) to 80 km/h (22.2 m/s) on an ORCS section featuring a nominal 200 mm (0.2 m) clearance and ∼200 m section length. Before processing, the raw signals underwent mandatory data cleaning to ensure input quality: instantaneous outliers were suppressed using a thresholding based on a local median filter; saturation data points were flagged; and small missing data segments were filled via linear interpolation.

Field testing was conducted on a metro line, which constitutes the second phase of an existing project and includes six subway stations. According to the relevant design documentation and drawings of the ORCS, the entire rigid conductor system comprises 25 overlaps, with 24 being of the L-in-R-out type and the remaining one being R-in-L-out. In compliance with established technical specifications in reference [

6], comprehensive measurements were performed, including contact force, geometric parameters of the ORCS, vibration acceleration of the pantograph head, arcing, and so on. The measurement of contact force was specifically carried out on the pantograph using force transducers installed at the pantograph strip bracket seat, enabling the derivation of stagger information from the bracket forces.

A segment of the bracket forces from the first strip in the forward direction of the vehicle is presented in the bottom plot of

Figure 2. The signals exhibit a periodic pattern of approximately 10 s (0.1 Hz), which corresponds to the oscillating period of the transversal motion of the bracket seat. This motion effectively reproduces the stagger of the contact wire (with a 200 m section length) at the vehicle’s running speed of 80 km/h. Utilizing these bracket forces, the raw stagger signal was calculated using Equation (

1) and subsequently filtered by the Butterworth filter with a passband frequency (

) of 1 Hz and a stopband frequency (

) of 2 Hz.

The results of this initial processing are shown in

Figure 7a, with

Figure 7b providing a zoomed-in view of the signals between 50 s and 80 s. While it is visually apparent to locate the section overlaps in

Figure 7b—as the stagger at 52 s, 62 s, and 74 s deflects towards the side where the new contact wire enters-this visual identification is insufficient for automated detection by a computer algorithm.

Figure 7a displays 25 similar overlap-related patterns, which are in strong agreement with the ORCS design documentation. It is important to note that, due to a side effect of the filter, the stagger deflection distance observed in the overlap is slightly less than the actual clearance (200 mm) between the conductor rails.

Obtaining a smooth stagger signal for the entire metro line is merely a preliminary step. A key objective of this work is to automatically identify and locate overlaps within the calculated and smoothed stagger data using advanced data processing techniques, specifically the difference operator, peak analysis, and filtering.

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.3 provide a detailed description of the application and optimization of these technologies.

4.1. Length of the Difference Operator

As discussed in

Section 3.3, both the stagger difference (

) and the force allocation proportion (

) influence the results of the difference operator.

Figure 8 compares the peak prominence observed at different difference lengths (

N). When the first-order difference of the predictive stagger is directly calculated (

), numerous local outliers are visible, but their amplitude remains within 10 mm (

Figure 8a). As

N increases to 50, the amplitude of these local outliers rises to 200 mm, approaching the actual clearance between conductor rails. However, at this larger

N, these local outliers become submerged in interference noise, and their relative prominence decreases (

Figure 8b).

To effectively distinguish the effects of

and

and identify the optimal difference length for overlap detection, we plotted the kurtosis of the difference results for difference lengths

N ranging from 1 to 50. As shown in

Figure 9a, the kurtosis initially increases and then decreases with increasing

N. This behavior indicates that at smaller difference lengths,

plays a more significant role in shaping the signal, while beyond a certain range,

becomes dominant. The local maximum kurtosis corresponds to the optimal difference length (

), signifying the point where the difference operator most effectively highlights the sharp, distinct changes associated with overlap transitions while suppressing continuous variations.

Using this optimal difference length (

), we performed the difference operation for each length less than

. The resulting difference matrix is presented as a color map in

Figure 9b, with the predictive stagger scaled in amplitude for visual interpretation. As clearly depicted, at the first 24 overlap positions, the matrix exhibits a local minimum (indicated by blue vertical lines intermixed with red ones), which corresponds to the L-in-R-out overlaps. Conversely, at the last overlap position, the matrix shows a prominent local maximum (indicated by a distinct red vertical line), signifying the R-in-L-out overlap. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the difference operator and kurtosis-based optimization in identifying overlap types.

4.2. Peak Prominence Settings

The accurate identification of overlaps from the difference matrix relies heavily on appropriate peak detection parameters. We focused on two critical performance metrics for our peak recognizer: precision (how many identified overlaps are real) and recall (how many real overlaps are successfully recognized). To ensure a rigorous and reproducible assessment of overlap localization accuracy, we first define the evaluation tolerance window (

). Based on the filter sensitivity analysis, the observed spatial deviation of the inflection point at the overlap ends is approximately

at a running speed of

. We therefore set the maximum acceptable localization error as a tolerance window

. A detected overlap is counted as a True Positive (TP) only if its center falls within

of the documented ground truth center. The ground truth was established by meticulous frame-by-frame video checking, and the labeling error is considered negligible (≪1 m).

Table 2 presents the confusion matrix used for evaluating our peak analysis.

To comprehensively evaluate the recognizer’s performance [

34], especially prioritizing the successful recognition of all real overlaps (recall), we employed the weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall, the

-score. Given our emphasis on maintenance economy and safety, we set

(>1) in the

-score calculation:

Figure 10 plots the

-score as a function of peak prominence when identifying overlaps from the difference matrix. The results indicate that with a small prominence, not all peaks caused by actual overlaps are detected. Conversely, if the prominence is set too high, some real overlaps are erroneously discarded. The most suitable peak prominence was determined to be 42 mm, at which the

-score achieved a perfect score of 1. This signifies that the peak recognizer achieved both 100% precision and 100% recall, successfully identifying all real overlaps without any false positives or false negatives.

The perfect score (

) achieved for both layouts (summarized in

Table 3) was confirmed under the strict localization tolerance

. The absolute counts (TP/FP/FN: 25/0/0 for triangular and 7/0/0 for sinusoidal) and the calculated

confidence intervals (via the Bootstrap method) statistically validate the high reliability of our framework, confirming that the results are not due to an overly wide tolerance window or insufficient sample size, but rather the robust design of the algorithm.

Utilizing the optimal difference length (

) and the optimal peak prominence (42 mm),

Figure 11a presents the peak results identified from the minimum and maximum components of the difference matrix. By cross-referencing with the ORCS design documentation and drawings, it was confirmed that all 25 real overlaps were successfully identified. Furthermore, the analysis correctly distinguished the types: the first 24 overlaps were confirmed as L-in-R-out, and the last one as R-in-L-out. Given the precise location of each overlap center, the start and end points of the overlaps were subsequently determined through further peak analysis with adjusted settings.

Figure 11b illustrates the predicted stagger segment for each rigid conductor section, with the identified start and end points clearly marked.

4.3. Effects of the Filter Parameters

To assess the impact of the Butterworth filter parameters on the accuracy of stagger prediction, a comprehensive comparison between the predicted stagger and field measurements was conducted. With the initial settings of the Butterworth filter (

), the predicted stagger, as shown in

Figure 12d, demonstrates strong agreement with the measurements in terms of both amplitude and periodicity.

Given that the stagger distribution is crucial for understanding the wear characteristics of pantograph strips, the Bhattacharyya distance (B-dist) was employed to quantitatively evaluate the discrepancy between the measured and predicted stagger distributions. For rigorous analysis, the histograms in

Figure 12 were generated using a defined range of

, utilizing 60 bins (10 mm resolution per bin), and were normalized to the Probability Density Function (PDF). It is noted that the sample counts were not artificially balanced across intervals; instead, we ensured sectional consistency by comparing the stagger histories extracted from the identical physical ORCS segments, thereby maintaining the true spatial distribution characteristics for direct comparison. A smaller Bhattacharyya distance indicates a closer resemblance between the two distributions, with a zero distance implying identical distributions. For the overall ORCS, a comparison between

Figure 12a (measured stagger distribution) and

Figure 12b (predicted stagger distribution) reveals similar shapes, with a low B-dist of 0.0115. For a more granular assessment,

Figure 12c presents the B-dist for each individual ORCS section. The average B-dist across all sections was 0.0734, with a maximum of 0.1319 and a minimum of 0.0348, further confirming the high consistency between predicted and measured values.

To assess the sectional consistency across the 25 distinct ORCS segments, we analyzed the statistical variance of B-dist, KS (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) test, and EMD (Earth Mover’s Distance), as illustrated in

Figure 13. The average EMD across all sections was

, confirming high distribution fidelity even at the local level. While the overall KS test showed a significant difference (

), the low B-dist Mean (0.0734) and low EMD Mean (15.31 mm) collectively affirm that the discrepancies are minimal in magnitude, reflecting slight localized model biases rather than fundamental differences in the core distribution shape.

To systematically assess the sensitivity of the framework to filter parameters, we fixed the stopband frequency at 5 Hz, considering that the maximum frequency corresponding to ORCS support spacing in typical operating conditions does not exceed 5.5 Hz (e.g., for a 120 km/h running speed over 6 m ORCS support spacing). We then varied the passband frequency across a range from 0.2778 Hz to 1.9778 Hz, with increments of 0.1 Hz.

For these 18 different passband frequencies,

Figure 14a illustrates the coefficient of variation (mean value over standard deviation) of the B-dist for each ORCS section. The results show that within the specified passband frequency range, the B-dist variance coefficient exhibits a step-wise descent across three stages. Beyond a certain limit, it begins to change, but the amplitude of this change remains minimal (less than 0.02). To visualize the filter effects more intuitively,

Figure 14b presents a comparison between the predicted stagger history at several typical frequencies and the stagger measurements.

This comparison reveals that the pre-specified filter parameters have negligible impact on the predicted results within the main ORCS sections. However, they do affect the position of the inflection point at the ends of the overlap sections. The observed inflection point deviation range is approximately 0.2 s in time, which corresponds to a spatial deviation of about 4.4 m at a vehicle running speed of 80 km/h. For the purpose of locating the overlap section, this 4.4-m deviation is considered acceptable according to relevant positioning accuracy specifications [

35], as it is less than the distance between two adjacent ORCS supports. The low Bhattacharyya distance and robustness to changes in filter parameters collectively provide evidence for the framework’s practical deployability and reliability under varying operating conditions. This indicates that the system can operate reliably even with slight variations in environmental conditions or sensor noise, without requiring continuous calibration, which is a critical factor for long-term successful deployment.

Furthermore, the framework’s robustness against speed fluctuations was assessed by varying the vehicle speed ratio across

. As shown in

Figure 15, the stability of the distribution fidelity was maintained, with the EMD exhibiting a low Coefficient of Variation of

across the

to

speed range. This low variability, combined with the filter’s low sensitivity, confirms the stability of the prediction accuracy under typical operational speed changes, which is vital for real-world deployment.

4.4. Comparative Analysis with Baseline Methods

To quantitatively prove the efficacy of our proposed approach, a comparative analysis was conducted against three simplified baseline methods (

Table 4). Baselines 1 and 2 employed basic signal differentiation or smoothing techniques followed by fixed-threshold peak detection. Baseline 3 attempted a coarse localization using only the zero-crossings or extrema of the raw force ratio signal, bypassing the stagger calculation entirely. The results clearly demonstrate the quantitative superiority of the proposed framework. While Baselines 1 and 2 achieved a high Recall of

, they exhibited an unacceptably high False Positive (FP) rate (11 and 23 false alarms, respectively). This high FP count drastically reduced their Precision (B1:

; B2:

). By contrast, the proposed method isolates the sharp transition signature, achieved perfect Precision (

) with zero false alarms. This represents a significant reduction in the false alarm rate, indicating a

improvement in precision over the best competing baseline (B1). Furthermore, the proposed method exhibited perfect localization accuracy (

), demonstrating

lower error than the best baseline (

). Baseline 3, which attempted coarse localization, completely failed to identify the overlaps, underscoring the necessity of the full stagger prediction and difference matrix processing chain. This quantitative evidence validates that the complexity introduced by the adaptive Kurtosis Optimization is essential for reliably distinguishing true overlap events from continuous noise and signal fluctuations, which simpler fixed-parameter methods fail to achieve.

5. Application to Sinusoidal ORCS Layout

Having demonstrated the framework’s efficacy on a triangular ORCS layout, this section extends the validation to a sinusoidal ORCS configuration to further confirm its broad applicability and robustness across different common ORCS designs.

To provide a comprehensive assessment, we applied the developed data processing framework to field testing data obtained from another urban rail transit line, which features a sinusoidal ORCS stagger layout. The analysis focused on the ORCS section between two metro stations. The measured data included pantograph strip bracket forces, as well as ORCS geometry measurements acquired through image-based technology. Prior knowledge of the ORCS overlap configuration was established by meticulously checking recorded video frame by frame, revealing 7 overlaps along this ORCS section: 6 of which were R-in-L-out, and the remaining one was L-in-R-out.

Figure 16 presents a comparison between the predicted and measured stagger, with the curves of one-point difference on the stagger also included. Several key observations emerged from this comparison:

The measured stagger signal notably “lost” one L-in-R-out overlap, indicating a limitation in the direct measurement or visual interpretation for this specific layout.

Both the measured and predicted stagger signals showed no distinct stagger deflection at the overlap points, making it inherently difficult to visually locate the section overlaps for this sinusoidal configuration.

Applying a one-point difference to the predicted stagger did make the overlap indication clearer, but the prominence of these indications was still not sufficiently large for robust automatic detection.

Similarly, a one-point difference on the measured stagger presented several peaks, but it was impossible to reliably distinguish whether these local outliers were genuinely caused by section overlaps or by other noise sources.

Figure 16.

Stagger history and the one-point difference results in sinusoidal stagger layout. (a) Predicted stagger. (b) Measured stagger.

Figure 16.

Stagger history and the one-point difference results in sinusoidal stagger layout. (a) Predicted stagger. (b) Measured stagger.

These observations highlight the challenges associated with visually identifying overlaps in sinusoidal layouts and underscore the necessity of a more sophisticated algorithmic approach, such as the one proposed in this work.

Following the methodology outlined in

Section 3, the same data processing steps, including Butterworth filtering, difference matrix calculation, and peak analysis, were applied to the bracket forces obtained from the sinusoidal ORCS. Compared to the raw predicted stagger shown in

Figure 16a, the overlap indication (peak prominence) in

Figure 17a is significantly clearer, achieved with an optimal difference length (

) of 50. This larger

for the sinusoidal layout, compared to

for the triangular layout, demonstrates the adaptive nature of our kurtosis-based optimization, which successfully adjusts to the distinct characteristics of different ORCS geometries. This adaptive variation in

proves our framework’s universality and robustness, indicating that it is capable of intelligently adapting to different railway infrastructures, which is crucial for widespread deployment.

As shown in

Figure 17b, our data processing framework successfully located all 7 sinusoidal ORCS overlaps. Regarding the local oscillation observed in the predicted stagger near

mm in

Figure 17b, this phenomenon is primarily attributed to the local back-and-forth friction at the pantograph strip, a conclusion supported by the observation of the same oscillating pattern in the measured stagger (

Figure 16b) and confirmed by recorded video footage.

Similar to the triangular ORCS validation, the Bhattacharyya distance (B-dist) was employed to quantitatively evaluate the discrepancy between the measured and predicted stagger distributions in the sinusoidal scenario. As depicted in

Figure 17c (measured stagger distribution) and

Figure 17d (predicted stagger distribution), the two distributions exhibit a very similar appearance, with a corresponding B-dist of 0.0517. This further confirms the framework’s accuracy and reliability for sinusoidal ORCS. Compared to the triangular ORCS, the sinusoidal stagger layout tends to result in more contact points at the

mm position along the pantograph strip but fewer at the middle position, reflecting the inherent geometric differences between the two layouts.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study has successfully proposed and validated an innovative data processing framework that significantly advances the online monitoring of Overhead Rigid Conductor Systems (ORCS). By leveraging force measurements from pantograph strip brackets, the framework achieves accurate prediction of dynamic stagger and precise localization of section overlaps. In operational deployment, significant and persistent prediction–measurement residuals may be used as automated alarms for sensor faults or data issues, while the predicted stagger distribution can inform maintenance prioritization; threshold values should be determined by site-specific commissioning. This achievement is of substantial significance in the field of measurement and instrumentation science and technology, offering a robust and cost-effective alternative to traditional, often expensive and environmentally sensitive, visual inspection systems.

Throughout this work, we skillfully applied a beam model for the moving load problem, deriving a formula for calculating the external load’s position based on a quasi-static assumption. This theoretical foundation enabled the effective prediction of ORCS stagger in real-world pantograph-catenary interaction scenarios. Through in-depth theoretical analysis of the stagger variation principles as the pantograph traverses an overlap, we innovatively proposed using the minimum and maximum components of a difference matrix, derived from the predicted stagger, as input for a sophisticated peak analysis. This novel approach successfully achieved accurate localization of section overlap positions. Concurrently, the effectiveness of the zero-phase Butterworth filter in removing dynamic pulsations from the calculated stagger was comprehensively verified, confirming its crucial role in ensuring the precision and reliability of the stagger signal.

Rigorous comparison with comprehensive field test measurements and detailed design documents demonstrated the framework’s excellent applicability across both triangular and sinusoidal stagger layouts of rigid conductors. The framework not only accurately predicts the dynamic stagger of the contact wire but also precisely locates section overlap positions, showcasing its robustness and versatility. This achievement provides a novel and highly effective method for dynamic stagger measurement in ORCS, significantly enhancing the technical capabilities in this domain and enriching the scope of measurement and instrumentation science and technology within rail transit applications.

Looking ahead, considering the stringent time delay requirements of online monitoring systems and the diverse geometric measurement needs of ORCS, our future efforts will focus on developing an online version of this data processing framework. Furthermore, we aim to design an efficient algorithm for accurately calculating the height of the ORCS using bracket force measurements. This series of continuous research endeavors will further promote the in-depth development and widespread application of advanced measurement technology in the rail transit field, providing stronger technical support for the safe and efficient operation of rail transit systems, and contributing more innovative achievements to the broader field of measurement and instrumentation science and technology.