Abstract

The operation of an aero-engine involves various non-stationary processes of acceleration and deceleration, with rotational speed varying in response to changing working conditions to meet different power requirements. To investigate the nonlinear dynamic behaviour of cracked blades under variable rotational speed conditions, this study constructed a rotating blade model with edge-penetrating cracks and proposes a component modal synthesis method that accounts for time-varying rotational speed. The nonlinear response behaviours of cracked blades were examined under three distinct operating conditions: spinless, steady speed, and non-constant speed. The findings indicated a competitive relationship between the effects of rotational speed fluctuations and unbalanced excitation on crack nonlinearity. Variations in rotational speed dominated when rotational speed perturbation was minimal; conversely, aerodynamic forces dominated when the effects of rotational speed were pronounced. An increase in rotational speed perturbation enhanced the super-harmonic nonlinearity induced by cracks, elevated the nonlinear damage index (NDI), and accentuated the crack breathing effect. As the perturbation coefficient increased, the super-harmonic nonlinearity of the crack intensified, resulting in a more complex vibration form and phase diagram.

1. Introduction

Turbine blades are fundamental components of rotating machinery, including aviation engines, where their structural integrity is critical to the safe operation of the entire system. These blades operate in environments characterized by extreme conditions, often subjected to significant centrifugal and aerodynamic loads as well as alternating unbalanced excitation forces. As a result, rotating blades are prone to various forms of failure, with cracks being among the most common. With the increasing power of engines, these blades are frequently required to function under variable operating conditions. Understanding the nonlinear dynamic response of cracked blades under varying speed conditions is essential for ensuring the safety of aircraft engines.

Crack initiation and propagation are highly dependent on the applied loading conditions. Cracks do not always remain in an open state; instead, they may undergo a nonlinear process of periodic opening and closing. A significant body of research has been conducted by scholars on the modelling of cracked blades. Shen et al. [1] employed a bilinear spring–mass model and a square wave function to simulate the stiffness change process of a breathing cracked beam. Furthermore, the response characteristics of the system were analysed in the time domain and the harmonic components were examined in the frequency domain. Pugno et al. [2] derived the nonlinear equations of motion based on the assumptions of a periodic response and the cracks being continuously opened and closed. The nonlinear dynamic response behaviour of beams containing multiple breathing cracks under simple harmonic excitation was analysed from time to frequency domain. Chondros et al. [3] conducted a theoretical analysis of the vibration characteristics of simply supported beams containing breathing cracks and discovered that the crack-induced eigenvalue alterations were associated with the bilinear characteristics of the cracked system. Bovsunovsky et al. [4] presented the phenomenon of superharmonic vibration of a breathing cracked beam. Loutridis et al. [5] investigated the dynamic behaviour of cantilever beams with breathing cracks under harmonic excitation and demonstrated that the depth of the crack can be determined by the degree of harmonic distortion. In addition to beam theory, finite element (FE) theory has been employed extensively in the modelling of cracked blades. Andreaus [6,7] established a cantilever beam model utilising the two-dimensional finite element method (FEM), simulated the respiration behaviour of cracks by contact algorithms, and calculated its nonlinear response. Liu et al. [8,9] devised a cracked hexahedral element that considers the respiration effect based on the strain energy release rate and validated it by comparing the results of FEM with the results of contact calculations. Zhao et al. [10] developed a cracked beam element that considers the breathing effect and employed this cracked beam unit in conjunction with a Timoshenko beam element to create a pre-twisted cracked blade model. Guan et al. [11] developed FE models of edge-cracked blades and surface-cracked blades that incorporated the breathing effect and conducted simulations of the breathing effect using a spring element.

The advancement of modelling theory has facilitated the investigation of nonlinear characteristics associated with cracks. The utilisation of time-domain simulations in conjunction with frequency-domain features and nonlinear modal analysis has been employed in a multitude of applications. These time-domain frequency-domain features can be employed for the identification of cracks. Eroglu et al. [12] employed a modelling approach to investigate the behaviour of planar curved beams containing cracks. The differential evolution method is employed for the purpose of solving the aforementioned identification problem. Zeng et al. [13] constructed three FE models of crack-breathing beams based on three common crack types. They then identified the severity of the cracks through the use of phase diagrams and evaluated the strength of crack breathing through the analysis of contact stress distribution. Shen et al. [14] derived a coupled expression for the dynamic stiffness and crack depth of a cantilever beam and proposed a method for detecting cracks in such structures based on the power ratio of harmonic components. SEO et al. [15] employed a deep learning approach to accurately predict the location and size of turbine blade cracks using frequency response function data obtained from FE analysis. Wang et al. [16] proposed a dynamic contact breathing crack model for rotating blades based on self-programmed non-coordinated hexahedral elements, and the breathing effect was simulated using spring elements. A breathing crack quantification index was employed for the purpose of characterising the nonlinear level of breathing cracks. Yang et al. [17] developed a coupled vibration model that incorporates the nonlinear effects of shaft and blade flexibility, oscillating motion of the offset blade disc structure, and blade breathing cracks. They also investigated the influence of conditional parameters, including blade imbalance, blade aerodynamic forces, and crack depth, on the aforementioned crack indicators. In order to analyse the failure mechanism of blade cracking and to study the effect of blade cracking on the three-dimensional blade tip clearance of the blade disc, Zhang et al. [18] established a kinetic model based on the continuum theory, which considers blade cracking. In a study by Wang et al. [19], a FE model of a microcracked blade was developed. The model was used to demonstrate that frequency reduction and the appearance of superharmonics can be used as indicators of the presence and severity of blade cracks.

Given that the blades are operating at high speeds, it is essential to consider the impact of rotation speed on the nonlinear vibration response of cracked blades. A significant body of research has been conducted by scholars on the vibration characteristics of breathing cracked blades under rotating conditions. Saito et al. [20] employed a multi-harmonic hybrid approach in the time-frequency domain to analyse the forced vibration response of a cracked blade. Additionally, they investigated the influence of crack length and rotational speed on the resonant frequency. Xu et al. [21] put forth a power flow-based methodology for the nonlinear mechanical behaviour of rotating blades containing breathing cracks, particularly for tiny cracks with insignificant breathing effects. Additionally, they elucidated the influence of crack parameters on the breathing behaviour of cracked blades. Yang et al. [22] developed a rotationally cracked blade model incorporating rotational softening, centrifugal stiffening, Koch’s effect, and crack closure, based on the continuous beam theory and strain energy release rate. They introduced an NDI to characterise the nonlinearities caused by blade cracking and solved the nonlinear response of the cracked blade. Zhang et al. [23] developed a rotating blade cracking dynamics model based on shear beam theory, which considers three-dimensional tip clearance. The model introduces axial and circumferential aerodynamic loads to calculate the nonlinear response of the cracked blade. Lin et al. [24] investigated the influence of rotational speed on the nonlinear vibration of the cracked blade, with a particular focus on radial and torsional vibration.

Studies on the nonlinear response of cracked blades have often assumed a constant rotational speed, introducing rotational effects into the kinetic equations through methods such as centrifugal loading. However, in practice, blades do not operate at a fixed rotational speed but rather in a quasi-steady state, with slight perturbations around a constant speed. Some researchers suggest that these speed perturbations can be modelled as a linear superposition of a constant rotational speed and a simple harmonic perturbation. The impact of time-varying angular velocities on the vibration of Euler beams was first explored by Kammer et al. in 1987 [25], where the time-varying angular velocity was simplified as the sum of a steady-state value and a minor periodic variation. In a pre-twisted, variable-section cantilever beam model, Young [26] introduced simplified boundary conditions for time-varying angular velocity and found that such variations induce instability in the dynamic parameters of the beam. Yang et al. [27] further discovered that a 2:1 internal resonance is particularly sensitive to changes in system parameters, and they demonstrated that increasing the pre-twist angle while decreasing the stagger angle can mitigate the instability caused by time-varying rotational speeds. Yao et al. [28,29] formulated the dynamic equations for pre-twisted, thin-walled rotating cantilever beams based on Euler beam theory and Hamilton’s principle. They also calculated aerodynamic forces using first-order piston theory and solved the nonlinear response of variable-speed blades under aerodynamic excitation. Georgiades et al. [30,31] constructed a model for a pre-twisted composite beam subjected to variable rotational speeds and analysed its nonlinear response using the multiscale regression method. Similarly, Arvin [32] developed a model for a variable-speed rotating Euler beam, incorporating geometric nonlinearities, and employed the Galerkin method for discretization. The nonlinear vibration was then computed using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method. Zeng et al. [33] used FEM to model a blade with breathing cracks, investigating the nonlinear response of the cracked blade during the acceleration phase. Liu et al. [34] also utilized FEM to model a variable-speed composite cantilever plate, considering geometric nonlinearities, and examined the impact of various structural parameters on the blade’s nonlinear dynamic behaviour. Eftekhari et al. [35] previously developed dynamic equations for rotating pre-twisted beams with time-varying angular velocity perturbations and airflow disturbances. Their findings revealed nonlinear phenomena such as jumps, saturation, and double jumps in the beam’s dynamic behaviour. Lotfan et al. [36] used a geometrically exact method to derive the dynamic equations for functional gradient beams with periodic rotational speed perturbations, showing that these beams experience rotational speed fluctuations at the perturbation frequency, with their damping coefficients and functional gradient material properties exhibiting complex nonlinear behaviour.

In summary, most studies on time-varying rotational speed perturbations have focused on healthy beam models, primarily investigating geometric nonlinearities. Furthermore, research on the vibration behaviour of breathing cracked blades has largely been conducted under steady-state rotational speed conditions. However, there remains a lack of systematic studies on the dynamic behaviour and nonlinear response of cracked blades under rotational speed perturbations. In terms of modelling, the FEM using contact elements is more accurate but less efficient for modelling cracked blades with complex blade shapes. To balance accuracy and efficiency, a large number of researchers [8,9,10,16] have used methods such as self-programmed cracked elements, but none of them locally refined the mesh near the cracks, so the dynamic behaviour near the cracks was not calculated in detail. The Component Modal Synthesis (CMS) method allows the reduction of degrees of freedom for complex meshes, but there is still room for improvement in contact calculations under variable speed conditions.

This paper proposes a reduced-order modelling method for pre-twisted cracked blades with edge penetration cracks. The improved methodology (CMS–Solid), based on CMS, retains solid elements near the crack and effectively accounts for the influence of variable rotational velocity on the crack. This approach reduces the degrees of freedom (DOF) in the FE model of the blade, enabling precise calculation of crack breathing behaviour. The effect of cosine speed perturbation on the breathing behaviour and nonlinear response of the cracked blade is also examined, providing a theoretical reference for diagnosing cracking faults and blade failure under speed perturbation conditions.

The framework of this paper is as follows: in Section 2, the blade model with breathing crack is developed by using CMS–Solid and verified; in Section 3, the nonlinear dynamic characteristics of the cracked blade under speed perturbation conditions are investigated; finally, several conclusions and some notes on future work are drawn in Section 4.

2. Dynamic Modeling of Variable Speed Cracked Blade

2.1. FE Modeling of Variable Speed Turbine Blades with Edge Penetration Crack

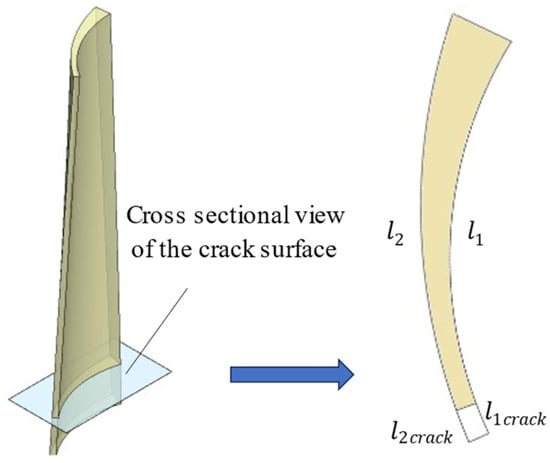

Although modelling the entire blade disc structure allows for a more comprehensive consideration of the symmetry of the disc, a substantial body of literature has modelled it from the perspective of a single cracked blade. The use of a single blade allows for a more detailed examination of the cracked breathing behaviour, while also reducing the computational resources required. A pre-twisted blade model is used to simulate an aero-engine turbine blade, incorporating edge penetration cracks into the intact turbine blade model, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The schematic of edge penetration cracked blade.

The dimensionless crack depth for rectangular edge penetration cracks is defined as follows:

where l1 and l2 represent the lengths between the abaxial blade surface and the blade basin surface at the section where the blade crack is located, η1 is the dimensionless crack depth, and l1crack and l2crack are the lengths of the edge penetration crack between the abaxial blade surface and the blade basin surface.

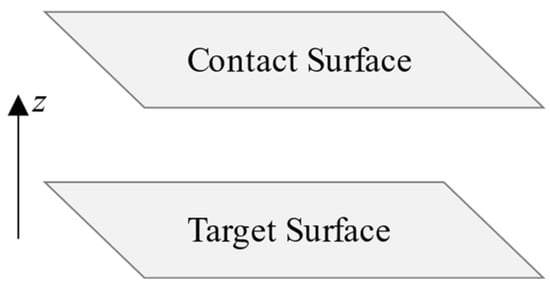

Throughout the operational lifespan of an aircraft blade, cracks do not remain persistently open but instead exhibit a cyclical pattern of opening and closing. By incorporating contact and target elements on both sides of the compromised surface, the crack gap can be expressed as follows:

where gn denotes the gap distance of the nth contact pair, represents the z-direction displacement of the target node, represents the z-direction displacement of the contact node, and ε is the intrusion tolerance (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of cracked surface contact calculation.

If gn > 0, the crack opens and the contact calculation is not applied; if gn ≤ 0, the crack closes and the contact iteration algorithm is applied. The contact stiffness is optimized using the Generalized Lagrange Multiplier method during the contact iteration.

Centrifugal loads arising from rotational effects are introduced into the dynamic equations as initial stresses. The non-constant speed is represented as the superposition of a constant speed and a cyclic speed perturbation, with the time-varying speed ω(t) expressed as follows:

where ω0 denotes the steady velocity, k is the velocity perturbation amplitude coefficient, and ω1 is the velocity perturbation frequency. The aerodynamic force on the blade is expressed as follows:

The constant speed condition is incorporated into the stiffness term as a rotational effect, while the variable speed condition is introduced as a time-varying force boundary condition. The kinetic equation of the breathing cracked blade under non-constant speed conditions is expressed as follows:

where M is the mass matrix, Kstr is the structural stiffness matrix, Kc is the centrifugal stiffness matrix, and Ks is the rotational softening matrix. FΩ is the external excitation force caused by rotational speed perturbations, introduced into the kinetic equation through the inertial load under the corresponding acceleration. The damping matrix C is used to model the structural damping of the blade as Rayleigh damping:

Kcrack is the total crack stiffness matrix corresponding to the crack contact stiffness, with the same dimensions as the total stiffness matrix, where:

where Kn is the initial value of the contact stiffness, i is the number of iterations of the contact, and λi+1 is the Lagrange multiplier, defined as follows:

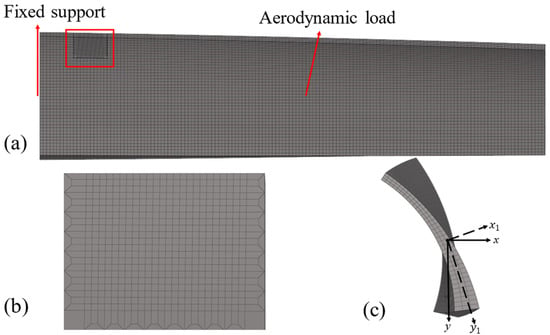

The edge penetration crack is prefabricated at the front end of the turbine blade near the root. The FE model of the cracked blade is shown in Figure 3. Eight-node hexahedral elements are used for discretization, with the mesh near the crack refined using the progressive mesh generation method for greater accuracy. The target element is selected for the cracked surface near the root of the blade, while the contact element is selected for the cracked surface near the blade tip. The contact algorithm employs the Generalized Lagrange method to establish normal frictionless contact. The stable working speed is set at the first-order subcritical speed of 6250 rpm, and the blade material and other parameters are presented in Table 1.

Figure 3.

FE model of the cracked blade: (a) edge penetration of the cracked blade, (b) progressive meshing of the cracked region, (c) top view of the blade.

Table 1.

Parameters of cracked blade.

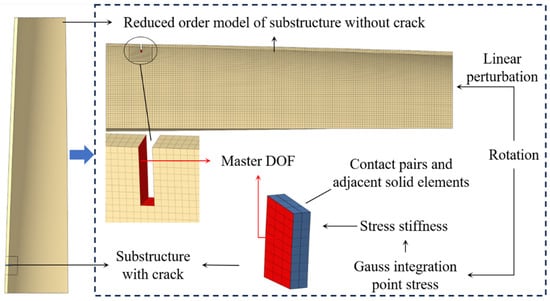

2.2. CMS–Solid Method for Cracked Blade at Time-Varying Rotational Speeds

The presence of cracks necessitates local mesh refinement in the vicinity of the cracks, significantly increasing the number of DOFs in the FE model. To enhance computational efficiency, it is crucial to identify an appropriate method for reducing the DOF in the structure. The contact elements and their adjacent layers of solid elements are designated as the cracked zone, while the remainder of the structure is treated as the uncracked zone. The uncracked zone is selected as the substructure for reduction using the CMS method. Concurrently, the cracked zone is retained as the unreduced substructure, allowing for the subsequent introduction of the time-varying stress–stiffness matrix as the contact element. This matrix provides the initial iterative stiffness influenced by the time-varying rotational speed. For the FE model of the non-cracked zone substructure, the vibration equation can be expressed as follows:

where the interface force FInterface at the substructure interface is cancelled out by internal forces during model assembly, thereby eliminating any potential for distortion.

In the case of non-cracked zone substructures, assuming that a represents the number of principal modes selected, i the number of internal DOF of the substructure, and j denotes the interfacial DOF of the substructure. The modal matrix of the substructure can be expressed in blocks as follows:

where Φia represents the principal modes selected for the substructure. The eigenvectors are obtained by solving the eigenvalue equations of dimension i and truncating at the first a orders. Ψij corresponds to the constrained modes, with the associated j sets of static displacement vectors obtained by solving the static equations in Equation (9). This process is carried out sequentially, with the j interface DOF taking specific element values while the remaining DOF are set to zero.

From the modal expansion equation,

The coordinate transformation formula for the substructure can be expressed as follows:

where qa denotes the principal modal coordinates and qj represents the fixed interface modal coordinates of the substructure. When a << i, a significant reduction in DOF is achieved. The dynamic equation of the substructure after condensation can then be expressed as follows:

where the superscript * represents the post-condensation matrix with dimensions a + j.

However, dividing a continuum into two substructures without considering the interaction at the interfaces when calculating the rotational effects on each substructure separately may lead to an underestimation of the accuracy of the CMS method. To improve the precision of the CMS method, an equivalent centrifugal load is employed to account for the rotational impact. The stress at the Gaussian integration points of each element is determined by calculating the element stress of the entire cracked blade in its rotating state. This stress file is then imported into the elements to obtain the corresponding initial stress–stiffness matrix, which is induced by rotation, for subsequent substructure calculations. By solving the stiffness matrix in the context of the complete structure’s rotational state, the rotational effects on both substructures are fully considered. When the element stiffness matrix is expressed, the equation can be written as follows:

where Ke is the element stiffness matrix, is the element stiffness matrix generated by material parameters, is the element centrifugal stiffening matrix, and is the element rotational softening matrix. In FEM, the element stiffness matrix comprises both the structural stiffness matrix and the stress–stiffness matrix, as expressed by:

where represents the stiffness matrix generated by the initial stress. The stress stiffening matrix and rotational softening matrix are derived from the equivalent rotational effect through this stress stiffening matrix, as follows:

When the element type is known, the integral in the equation can be converted into a Gaussian integral, allowing the corresponding stress matrix to be obtained by inputting the Gaussian integration point stress of the element and group. By adjusting the intensity of the input stresses, the rotational movement of the structure can be regulated, thereby enabling the transformation of time-varying rotational velocity into the stress–stiffness matrix Kσ. The dynamic equations of the substructure in the cracked zone can be expressed as follows:

By expanding the earlier equation with the stress–stiffness matrix and splicing the matrices and vectors according to the nodal DOF, the dynamic equations of the reduced model, which preserves the crack region in the substructure, are obtained:

In the post-reduction matrix, the superscript ′ denotes the number of DOF in the cracked region that have not been reduced, including the interface DOF. Consequently, the dimensions of the post-reduction matrix are a + b. Figure 4 illustrates the deceleration flow of the CMS–Solid method presented in this paper, considering time-varying rotational speeds.

Figure 4.

Reduction flow of the CMS–Solid, accounting for time-varying rotational speeds.

To linearise Equation (18), the Newton–Raphson method is employed, and the response is subsequently calculated using the Newmark-β method. Although time marching and nonlinear modal analysis provides a superior analysis of nonlinearities, the method of extracting frequency-domain data through time-domain simulation yields more time-dependent information. Furthermore, the cracked blade model presented in this paper is a continuous elastomer with a complex shape, exhibiting a greater number of modal frequencies and modal coupling. The utilisation of nonlinear modal analysis presents certain challenges. Therefore, a time-domain simulation was employed to extract frequency-domain data via Fourier variation.

2.3. Model Verification

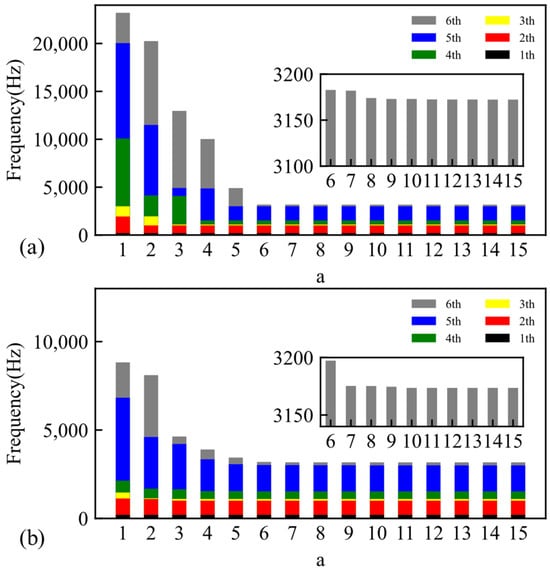

To validate the effectiveness and accuracy of this method in addressing the response of cracked blades, both stable and unsteady speed conditions were examined. The effects of a on the first six-order natural frequencies are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Effects of a on the first six-order frequencies convergence: (a) CMS, (b) CMS–Solid.

When a ≥ 10, the natural frequencies are almost unchanged. When the modal truncation number a is selected as 10, the reduced model exhibits a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. The reduced model was truncated by selecting the first ten modes. Table 2 compares the number of nodes across three methods: the FEM, the CMS, and the CMS–Solid method. The number of nodes and DOFs in the two reduced models constitutes less than 1% of those in the FE model. In subsequent calculations, the same modal truncation number and reduction substructure were employed, with the node and DOF counts identical to those presented in Table 2; thus, they are not repeated here.

Table 2.

Comparison of nodes between the reduced model and the FE model.

First, results were compared under stationary blade conditions, excluding rotational effects. The cracked blade, considering the breathing effect, represents a nonlinear system with nonlinear boundary conditions. Before performing the modal analysis, the system was linearised. The contact element retained the stiffness value of the initial state during modal calculation. In the modal solution, the breathing cracked blade was simplified to an open cracked blade. Constraints were applied at the root of the blade to conduct the modal analysis, and the resulting frequency data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequency of open cracked blades under spinless conditions.

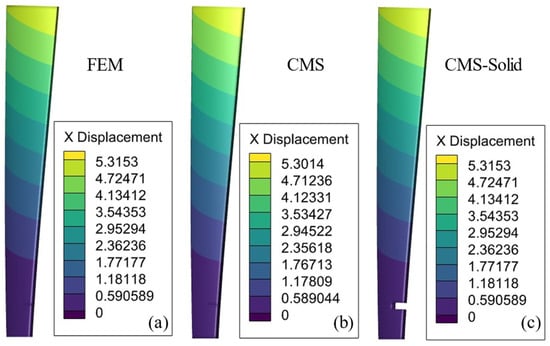

As shown in the table, the frequency errors for each mode are less than 0.2%, indicating that the modal truncation of the reduced model is highly accurate. Both CMS and CMS–Soild have good accuracy in the frequency range of 0–3000 Hz. To further assess the applicability of the reduced method in a nonlinear context, a quasi-static working condition was selected for evaluation. A load of 0.05 MPa was applied to the backwind side of the blade, and the static results from the three methods are presented in Figure 6. The extreme values of the blade tip’s x-direction displacement are provided in Table 4.

Figure 6.

x-direction displacement: (a) FE model, (b) CMS model, and (c) CMS–Solid model.

Table 4.

Extreme values of x-direction displacement of the blade tip.

As illustrated in the graphs, the CMS model exhibits an error of 0.26% compared to the FE model at the displacement extremes. By contrast, the CMS–Solid model demonstrates no error, confirming its accuracy based on the available data. Figure 7 shows the difference in displacements in the x-direction calculated by the CMS method and the CMS–Solid method using the FEM; the CMS method results in a difference in displacements due to the inability to obtain the initial iterative stiffnesses, whereas the CMS–Solid method fits the FEM well at all nodes. The CMS–Solid model, therefore, offers superior precision in the absence of rotational effects.

Figure 7.

x-direction displacement difference with FE model: (a) CMS model, (b) CMS–Solid model.

A steady rotational speed of 6250 rpm was selected for calculation under operating conditions that account for rotational effects. A modal analysis of the open-cracked blade was conducted, and the resulting first six natural frequencies are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Frequency of open-cracked blades at a steady rotational speed.

As illustrated in Table 5, the frequency errors between the two reduction methods and the FEM results do not exceed 0.2%. Both the CMS and CMS–Solid methods demonstrate high accuracy within the linear domain, suggesting that these methods provide effective model reduction when the first ten modes are retained. The frequency range in question encompasses a span of 0 to 3000 Hz, which is approximately 30 times the frequency corresponding to the operating speed of 6250 rpm as discussed in this paper. This ensures that the modal truncation is not a contributing factor to the accuracy of the response calculation.

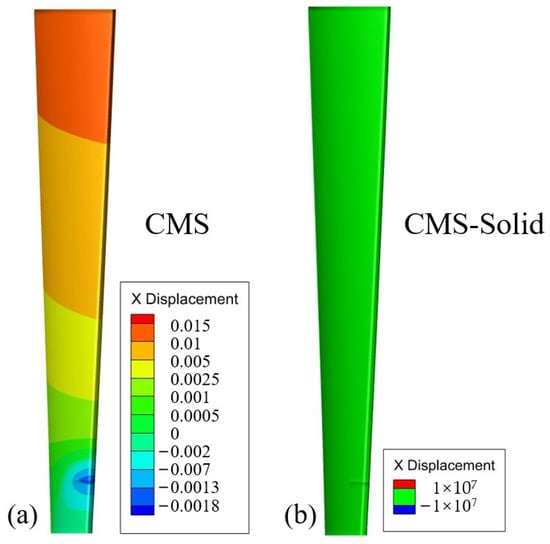

The blade was subjected to unbalanced excitation on the leeward side and in the axial direction, with the excitation frequency fe matching the rotational speed. A solution was carried out considering the contact effects, specifically the crack breathing behaviour to further verify the accuracy of these reduction methods in the nonlinear domain. The frequency domain results were obtained through a Fourier transform based on the time-domain response data. The corresponding response and frequency domain results are depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison of dynamic responses for three calculation methods at a steady rotational speed: (a) steady-state time-domain response results, (b) frequency-domain results.

The time-domain response results and the frequency-domain response results shown in Figure 8 are in high agreement with the calculated results of the edge-penetrating cracked blade in the literature [11], both of which show a significant second harmonic frequency. This proves the accuracy of the modelling in this paper. The CMS method exhibits a lower degree of error at the valley compared to the peak. This difference arises because the crack opens when the tip response is less than 0 and closes when it is greater than 0 during a vibration cycle. Once the crack closes, the contact elements must read the material parameters of both elements as the initial stiffness during the stiffness iteration. This results in larger errors in the contact calculations due to the reduction of all solid elements in the CMS method. Conversely, when the crack is open, contact is not involved in the calculation, and the system can be approximated as an open-cracked blade, thereby reducing the error. In contrast, the CMS–Solid method maintains the solid elements on both sides of the contact during modelling. Consequently, the initial stiffness required for the contact iterations can be consistently obtained throughout the course of vibration calculations. This ensures that the CMS–Solid method exhibits superior accuracy compared to the CMS method in crack breathing calculations. The CMS–Solid method demonstrates superior accuracy in both the time and frequency domains compared to the CMS method.

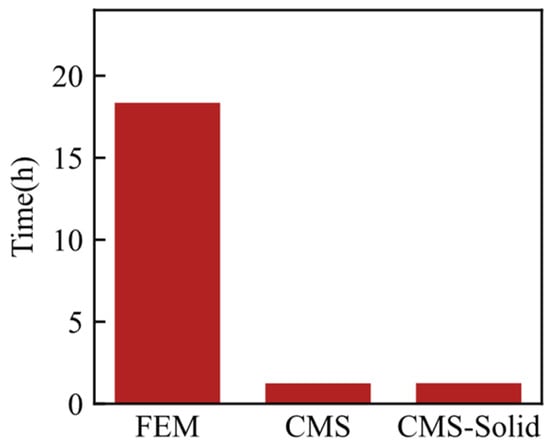

The response calculations were performed on all three models using the same computing device, which was equipped with an Intel Core i7-12700H processor and 32 GB of RAM. The device employed 4-core parallel computing. The computation times for the transient response are shown in Figure 9. Both reduced-order models demonstrate faster computation times than the FEM.

Figure 9.

Calculation time for transient response across three calculation methods.

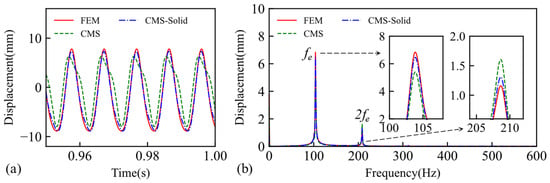

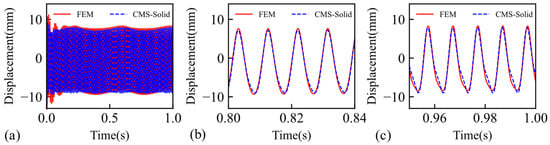

The efficacy of the CMS–Solid method in maintaining the integrity of the cracked region has been validated under steady-speed conditions. Time-varying control of the cracked blade speed can be achieved by controlling the stress at the Gaussian integration points of the elements in a time-varying manner. For a time-varying cosine rotational speed perturbation, the FEM and the CMS–Solid method with a preserved crack region were employed for the calculations. The amplitude and frequency of the rotational speed perturbation were defined as 2.5% of the steady rotational speed, affecting the blade’s back surface and axial imbalance excitation. The resulting time-domain response is illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Comparison of dynamic responses between FEM and CMS–Solid method at unsteady rotational speed: (a) overall response curve, (b) response magnification, and (c) response magnification.

The number of nodes used by the CMS–Solid method does not exceed 1% of those used by the FEM, resulting in a considerably faster convergence speed. The time-range curves indicate minimal disparity between the FEM and the crack region-preserving reduction method. The selected steady-state time-range response portion of the curve was Fourier transformed to yield the frequency domain diagram depicted in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Comparison of frequency domains between FEM and CMS–Solid method at unsteady rotational speeds.

As the rotational speed varies, the excitation frequency also varies and is represented in the spectrum by a series of bands, as illustrated in the shaded area of the above figure. The minute protrusions observed in the lower frequency bands of the spectrum are not noise; rather, they represent a reflection in the spectrum of the excitation of the blade due to the frequency of the rotational speed perturbation. Despite the limitations of the CMS–Solid model to compare results only with the FEM, there is a large body of literature [6,7,11,13,19] validating the high accuracy of the finite element method for modelling cracked blades. While slight discrepancies exist between the FEM and the CMS–Solid method in the time domain, the amplitude-frequency response curves demonstrate that the CMS–Solid method effectively captures the frequency domain information of the cracked blade response under variable rotational speeds, exhibiting a satisfactory correlation with the FEM. The CMS–Solid method consistently demonstrates superior accuracy compared to the CMS method, regardless of whether the solid elements are in a no-spin condition, steady speed condition, or cosine perturbation speed condition.

3. Characterisation of the Variable Speed Cracked Blade Vibrations

3.1. Effects of Closed-Loop Speed Perturbations

When the cracked blade was subjected to closed-loop rotational speed control, the frequency of the speed disturbance was assumed to match the frequency corresponding to the amplitude of the rotational speed disturbance. Under these conditions, the time-varying rotational speed ω(t) can be expressed as follows:

The aerodynamic force on the blade is then expressed as follows:

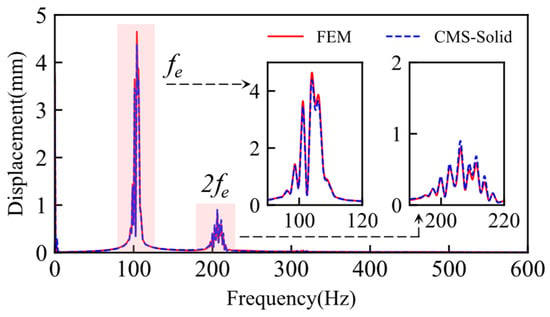

Although computational fluid dynamics was not used for the aerodynamic calculations, a sinusoidal function of the speed perturbation was introduced as a simplification due to the fact that the speed perturbation is relatively small compared to the steady speed. The aerodynamic model from the literature [20] was selected for response calculations to more accurately describe the effects of aerodynamic forces on cracked blades. The aerodynamic forces were decomposed into axial aerodynamic forces with a smaller amplitude (0.005 MPa) and aerodynamic forces on the blade basin surface with a slightly larger amplitude (0.05 MPa). Additionally, the effects of the dimensionless rotational speed perturbation amplitude on the nonlinear response of the crack were examined. The perturbation amplitude, ranging from 0 to 10%, was used in transient response calculations across several conditions. The sampling frequency corresponded to the stable rotational speed frequency of the structure. The results of the dynamic response are presented in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

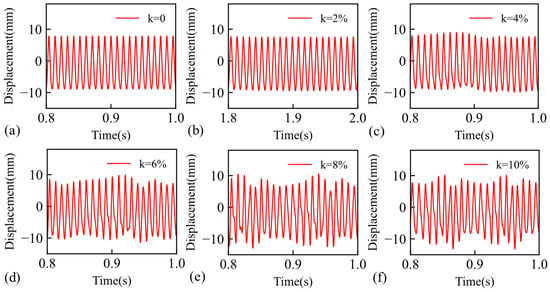

Figure 12.

x-direction response of the cracked blade tip for different amplitudes of rotational speed disturbance: (a) k = 0, (b) k = 2%, (c) k = 4%, (d) k = 6%, (e) k = 8%, and (f) k = 10%.

Figure 13.

Enlarged x-direction response of the cracked blade tip for different amplitudes of rotational speed disturbance: (a) k = 0, (b) k = 2%, (c) k = 4%, (d) k = 6%, (e) k = 8%, and (f) k = 10%.

With the increasing rotational speed perturbation coefficient, the overall waveform of the time-range response curve exhibited greater fluctuations. First, the rotational speed perturbation influenced the degree of fluctuation in the overall response. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that speed perturbation affects the stiffness matrix through rotational effects, continuously altering the static equilibrium position of the cracked blade. The rotational speed perturbation was incorporated into the response calculation as a time-varying stiffness term. Second, the perturbation affected the aerodynamic excitation frequency. As the perturbation coefficient increased, a notable super-harmonic response component emerged within the vibration waveform. When the perturbation coefficient was low, its impact primarily manifested as a shift in the static equilibrium position. Conversely, as the coefficient increased, the influence was characterised predominantly by the super-harmonic nonlinearity of the cracks under aerodynamic excitation. To further elucidate the impact of rotational speed perturbation on the frequency domain, spectral data for two types of cracked blades were obtained through Fourier transformation of the response curve, as illustrated in Figure 14.

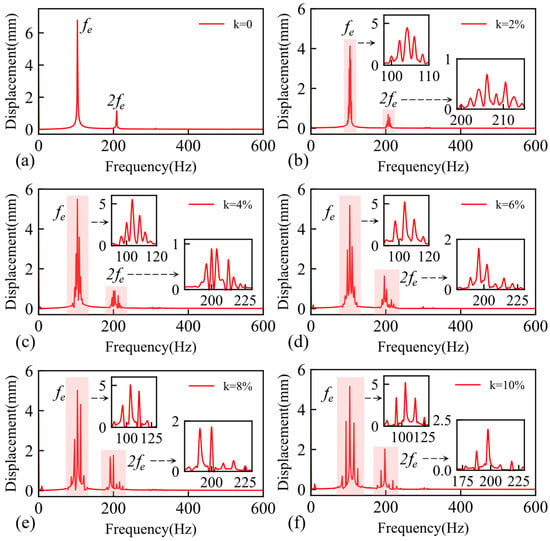

Figure 14.

Frequency spectrum of the cracked blade for different speed disturbance amplitudes: (a) k = 0, (b) k = 2%, (c) k = 4%, (d) k = 6%, (e) k = 8%, and (f) k = 10%.

As illustrated in Figure 14, variations in excitation frequency due to changes in rotational speed gave rise to a series of peaks in the spectrum. These peaks became increasingly dispersed as the rotational speed perturbation coefficient increased. The amplitude of the second harmonic frequency initially decreased and then increased. At low perturbation coefficients, the effect on aerodynamic frequency was minimal, and the cracked super-harmonic nonlinearities were not particularly sensitive to minor perturbations. However, the amplitude decreased due to the increased number of peaks, as smaller perturbations did not significantly enhance the energy share of super-harmonic oscillations. Additionally, variable rotational speeds broadened the spectral range for the octave, leading to a reduction in peak intensity. When the rotational speed perturbation coefficient was large, it substantially altered the aerodynamic frequency. In this scenario, the cracked blade’s response was primarily influenced by unbalanced aerodynamic excitation, enhancing the crack’s super-harmonic nonlinearity and increasing the amplitude of the second harmonic frequency. The spectral analysis considered only the effect of amplitude. To further understand the nonlinear behaviour of rotational speed perturbation coefficients in response to a breathing crack, the steady-state displacement response was extracted, and the steady-state velocity response was analysed in the phase plane (Figure 15).

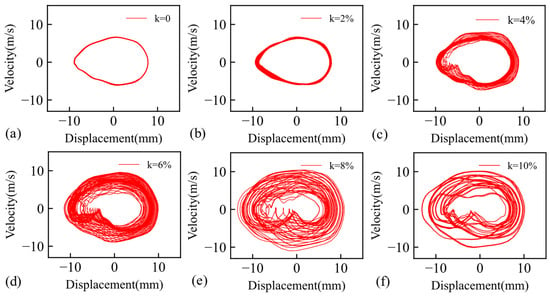

Figure 15.

Phase diagram of cracked blade at different speed disturbance amplitudes: (a) k = 0, (b) k = 2%, (c) k = 4%, (d) k = 6%, (e) k = 8%, and (f) k = 10%.

As the rotational speed disturbance coefficient increased, the range of the phase trajectory broadened, and the phase diagram became more complex. The rotational speed perturbation results in a non-constant rotational speed for the cracked blade, which in turn affects the equilibrium position of the blade at all times. This leads to a discrepancy in the phase track lines at each revolution, as they do not coincide with each other. Consequently, the extent of the phase track line range variation can be employed as a metric for assessing the magnitude of the rotational speed perturbation, particularly when the frequency of the perturbation differs from that of the stabilised rotational speed. At a perturbation coefficient of 2%, the trajectory widened without significant fluctuation, indicating that the primary influence on the phase diagram was the alteration in the static equilibrium position caused by the speed perturbation. As the coefficient increased, sharp fluctuations appeared on the inner side of the phase diagram, making the trajectory more intricate. This complexity can be attributed to the increased proportion of the super-harmonic component generated by crack nonlinearity, which modified the phase diagram. The occurrence of sharp wave pairs can result in a rapid alteration of the blade’s vibration speed within a relatively brief timeframe. This phenomenon has the potential to compromise the blade’s safety.

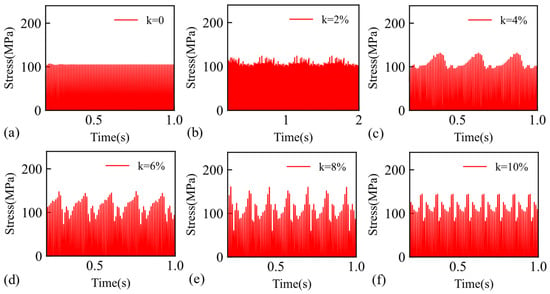

The time-course curve of the contact pressure on the cracked surface, shown in Figure 16, reflected the breathing behaviour of the structure. In the absence of disturbance, the peak contact stress remained stable. However, fluctuations in rotational speed induced corresponding fluctuations in crack contact stress. The amplitude of these stress changes was directly proportional to the amplitude of the rotational speed perturbation. The periodic fluctuation pattern of peak contact stress was similar to that of the response curve. Additionally, variations in peak contact stress were influenced by time-varying rotational speed and unbalanced aerodynamic excitation. In cases of minor rotational speed perturbation, the alteration of the static equilibrium position due to speed changes predominated, with a cosine trend observed in peak stress variation. As the perturbation increased, the influence of unbalanced aerodynamic excitation became more significant, causing the loss of the cosine variation pattern in peak contact stress. When the rotational speed perturbation coefficient exceeded 4%, the contact stress increased substantially, potentially compromising the safe operation of airfoil blades. Therefore, the effects of rotational speed perturbation must be considered in examining the nonlinear response of cracked blades.

Figure 16.

Time-course curves of contact stresses of cracked blade at different rotational speed disturbance amplitudes: (a) k = 0, (b) k = 2%, (c) k = 4%, (d) k = 6%, (e) k = 8%, and (f) k = 10%.

3.2. Effects of Speed Disturbances Due to Disc Shaft Failures

In cases of bearing or magazine failures, the rotational speed perturbation is typically correlated with the rotational speed. It can be assumed that the frequency of rotational speed perturbation in a cracked blade under fault conditions is equal to the frequency of the steady rotational speed. The time-varying rotational speed ω(t) can be expressed as follows:

Thus, the aerodynamic force on the blade can be expressed as follows:

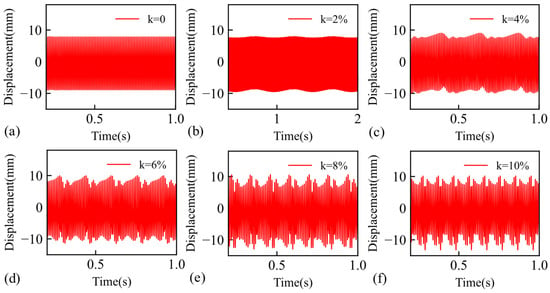

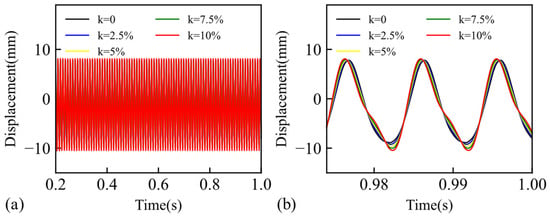

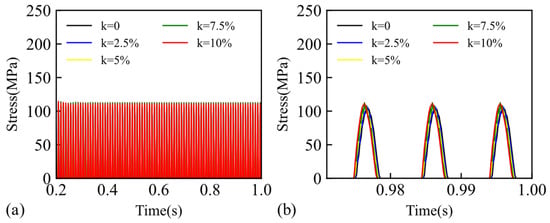

The dimensionless rotational speed perturbation amplitude k, ranging from 0% to 10%, was selected across five conditions for transient response calculations. The sampling frequency corresponded to the stable rotational speed frequency, and the calculation time was set to 1 s. The results of the dynamic response are presented in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

x-direction response of cracked blade with varying amplitudes of rotational speed perturbation: (a) overall response curve, (b) magnified response curve.

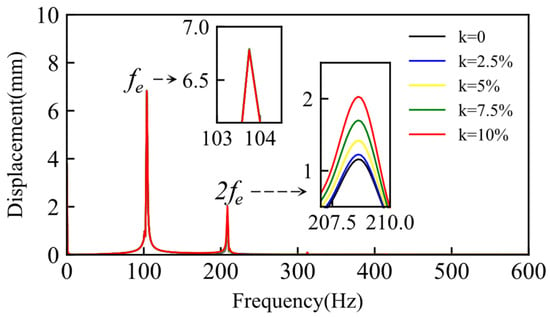

When the rotational speed perturbation frequency equalled the steady rotational speed frequency, the blade completed one full rotational speed change within a single vibration response cycle. As the rotational speed perturbation increased, the amplitude of the response curve increased, accompanied by a substantial increase in the super-harmonic response component. This led to a phase shift in the peak occurrence and an intensification of the super-harmonic nonlinearity associated with the cracks. The steady-state portion of the response curve was selected for Fourier transformation to investigate the effects of rotational speed perturbation on the amplitude–frequency response. The resulting frequency response curve is shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Frequency spectrum of a cracked blade for different speed disturbance amplitudes.

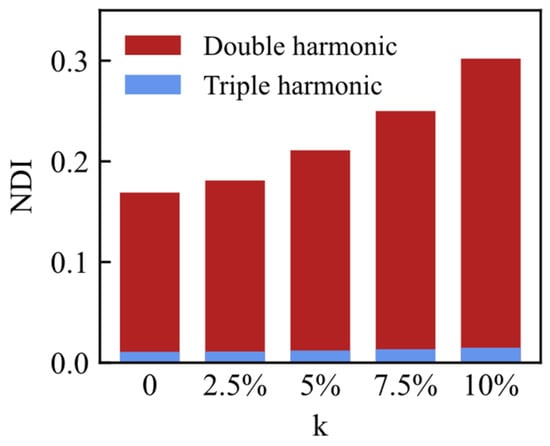

The presence of the crack introduced a second super-harmonic component and a third harmonic component into the vibration response. As the perturbation coefficient increased, the proportion of the second harmonic component gradually rose, as evidenced by the spectrogram, which showed an increase in the peak value at the second frequency. This reflects the enhanced super-harmonic nonlinearity of the crack. The NDI is typically employed to quantify the nonlinear effects of crack faults. The relative amplitude (Hs) of the super-harmonic or subharmonic component is expressed relative to the amplitude (Hb) of the fundamental harmonic component, as follows:

To further quantify the effect of the rotational speed perturbation coefficient on the nonlinearity of the cracked blade, the nonlinear damage indices at different coefficients were calculated separately, as illustrated in Figure 19. With an increase in the rotational speed perturbation coefficient, the NDI of the second harmonic component exhibited a continuous increase, while the change in the NDI of the third harmonic component was less pronounced. The increase in the rotational speed perturbation factor significantly enhanced the percentage of super-harmonic components due to crack nonlinearity. Additionally, it had a considerable impact on the percentage of second harmonic components, nearly doubling the original nonlinear damage index. However, the effects on the lower harmonic energy and higher-order harmonic components were less prominent.

Figure 19.

NDI of a cracked blade under varying rotational speed disturbance amplitudes.

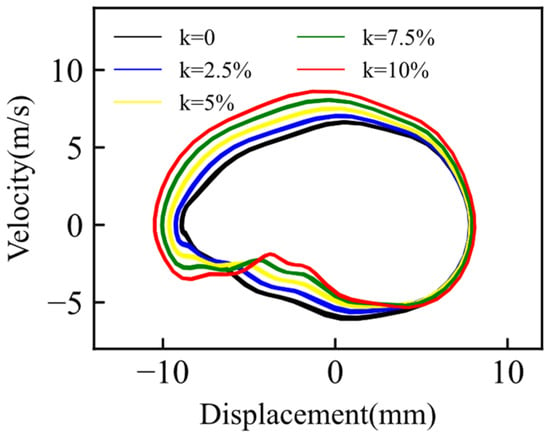

Super-harmonic components and the NDI effectively characterise the nonlinear behaviour of breathing cracks. However, spectral analysis only considers the amplitude information of blade vibration, neglecting data that might provide valuable insights into crack damage. The steady-state displacement response was extracted, and the steady-state velocity response was examined in the phase plane to further analyse the effects of the rotational speed perturbation coefficient on the nonlinear response of a breathing-cracked blade (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Phase diagram of cracked blades at different rotational speed disturbance amplitudes.

As the rotational speed perturbation coefficient increased, the phase diagram exhibited greater inward concavity and a more complex shape, primarily because of the increased proportion of the super-harmonic component in the vibration response. For perturbation coefficients lower than 2.5%, no significant inward concavity was observed in the phase-track line. However, as the perturbation coefficient increased further, the bending amplitude of the phase-track line also increased, leading to noticeable asymmetry. The complexity of the bending in the phase track line can serve as a criterion for assessing the magnitude of the rotational speed perturbation’s impact in the presence of a fault. At the point of crack closure, the phase track lines under different RPM disturbance coefficients exhibited minimal variation and nearly overlapped. This finding is in accordance with the conclusion presented in the existing literature [25], which suggests that the phase track lines overlap during the process of crack closure. When the crack parameters remained constant, this phenomenon provided a basis for assessing the crack state, with crack opening occurring at the dispersed phase track lines and closure at the overlapping phase track lines.

Figure 21 illustrates the time-course curve of contact pressure at the crack surface, reflecting the breathing behaviour of the structure. Evaluating crack contact stress visually represented the extent of crack breathing. The crack opens when the contact stress is minimal and closes when the contact stress is non-zero. Furthermore, the magnitude of the peak contact stress indicated the strength of crack breathing, while the width of the peak indicated the speed of crack breathing. In the event of a speed disturbance caused by shaft disc failure, an increase in the disturbance factor was observed to correspond with a proportional increase in the peak value of time-range contact stress, along with a strengthened closure effect of crack breathing. Additionally, an increase in the perturbation factor resulted in a phase shift in crack breathing, with a slight advancement in the timing of crack closure.

Figure 21.

Time course of contact stresses on a cracked blade under different rotational speed disturbance amplitudes: (a) overall contact stresses and (b) magnified view of contact stresses.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents a modal synthesis method that more accurately considers the impact of time-varying rotational speed on crack breathing behaviour. This approach retains the solid elements on both sides of the crack, thereby providing stiffness for contact calculations. The results are compared with those obtained using FEM analyses at stationary, steady, and unsteady rotational speeds, thus verifying the validity of the proposed method. Based on this foundation, a reduction model containing edge-penetrating cracks is established using the CMS method, and nonlinear response calculations are conducted for two different forms of rotational speed perturbation. The following conclusions are drawn:

- For cracked blades subjected to closed-loop rotational speed perturbation control, a competition exists between the effects of rotational speed changes and unbalanced excitation on crack nonlinearity. In scenarios with low perturbations, the variation in rotational speed is the dominant factor. Conversely, at higher perturbation levels, aerodynamic excitation becomes the primary influence. When the cracked blade experiences control by fault speed disturbance, the response is predominantly characterised by the effects of crack super-harmonic nonlinearity under aerodynamic excitation.

- An increase in the rotational speed perturbation coefficient results in a higher proportion of second harmonic components and a reinforcement of the super-harmonic nonlinearity associated with crack generation. The rotational speed perturbation significantly affects the proportion of second harmonic components while exerting a relatively weaker influence on lower harmonic energy and higher harmonic components.

- Non-constant rotational speed has a more substantial effect on the nonlinear vibration of cracked blades. In comparison to a steady rotational speed, a non-constant rotational speed leads to an increased vibration range of the blade, enhanced super-harmonic nonlinearity due to cracks, a higher nonlinear damage index, and an intensified breathing effect of the cracks. These factors consequently raise safety concerns, including the potential for contact between the cracked blade and the magazine and an accelerated fatigue fracture of the cracked blade. Therefore, the impact of rotational speed fluctuations on cracked blades must be considered in investigations involving such blades.

- Non-linear intensity of crack breathing can be efficiently assessed with the NDI. The shape of the phase diagram can reflect the state of crack breathing, with cracks closing where the phase track lines overlap and opening where the phase track lines are dispersed. The degree of inward depression of the phase track lines can reflect the magnitude of the RPM disturbance. The greater the speed disturbance, the greater the extent of the phase track lines.

In future work, we will try to optimise to obtain more accurate aerodynamic equations. The effect of aerodynamic damping and non-linear damping at the crack on the cracked blade will be considered and discussed for different crack shapes and other parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.F. and B.S.; methodology, B.S. and J.Z.; software, B.S. and J.Z.; validation, S.F.; formal analysis, C.F., S.F. and J.Z.; resources, C.F.; data curation, C.F. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.; writing—review and editing, B.S.; visualisation, B.S.; supervision, C.F.; funding acquisition, C.F., S.F. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation (Grant nos. 12202368), the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2022NSFSC1997, 2023NSFSC0068), the Key Laboratory of Vibration and Control of Aero Propulsion System, Ministry of Education, Northeastern University of China (No. VCAME202205).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shen, M.H.H.; Chu, Y.C. Vibrations of beams with a fatigue crack. Comput. Struct. 1992, 45, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugno, N.; Surace, C.; Ruotolo, R. Evaluation of the non-linear dynamic response to harmonic excitation of a beam with several breathing cracks. J. Sound Vib. 2000, 235, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondros, T.G.; Dimarogonas, A.D.; Yao, J. Vibration of a beam with a breathing crack. J. Sound Vib. 2001, 239, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovsunovsky, A.P.; Surace, C. Consideration regarding superharmonic vibrations of a cracked beam and the variation in damping caused by the presence of the crack. J. Sound Vib. 2005, 288, 865–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutridis, S.; Douka, E.; Hadjileontiadis, L.J. Forced vibration behavior and crack detection of cracked beams using instantaneous frequency. NDT E Int. 2005, 38, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreaus, U.; Casini, P.; Vestroni, F. Nonlinear dynamics of a cracked cantilever beam under harmonic excitation. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2007, 42, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreaus, U.; Baragatti, P. Cracked beam identification by numerically analysing the nonlinear behaviour of the harmonically forced response. J. Sound Vib. 2011, 330, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, D. Crack modeling of rotating blades with cracked hexahedral finite element method. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2014, 46, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, D.; Chu, F. Influence of alternating loads on nonlinear vibration characteristics of cracked blade in rotor system. J. Sound Vib. 2015, 353, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.G.; Zeng, J.; Ma, H.; Ni, K.X.; Wen, B.C. Dynamic analysis of cracked rotating blade using cracked beam element. Results Phys. 2018, 19, 103360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Xiong, Q.; Ma, H.; Wang, W.; Ni, K.X.; Wu, Z.Y.; Yin, X.M.; Zhao, S.T.; Zhang, X.X. Comparison of nonlinear vibration responses induced by edge crack and surface crack of compressor blades. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 216, 111465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, U.; Tufekci, E. Crack modeling and identification in curved beams using differential evolution. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2017, 131, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Ma, H.; Zhang, W.S.; Wen, B.C. Dynamic characteristic analysis of cracked cantilever beams under different crack types. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2017, 74, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.J.; Gu, F.S.; Yang, Y.M.; Hu, H.F.; Guan, F.J. Theoretical and experimental harmonic analysis of cracked blade vibration. Measurement 2023, 222, 113681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.W.; Han, J.S. Deep learning approach for predicting crack initiation position and size in a steam turbine blade using frequency response and model order reduction. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 1971–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.W.; Ma, H.; Zhao, C.G.; Wu, Z.Y.; Wang, H.J. Dynamic contact characteristics of a rotating twisted variable-section blade with breathing crack. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 858–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Z.B.; Mao, Z.; Chen, X.F. Coupling vibration mechanism of multistage blisk-rotor system with blade crack. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 202, 105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.D.; Xiong, Y.W.; Fan, B.C.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, X.; Dai, F. Research on dynamic characteristics of three-dimensional tip clearance with regard to blade crack depth and location of rotary blade-disk-shaft coupling system. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 4273–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, T.Y.; Wang, Z.W.; Liu, W.Y.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.H. Simulation and experimental research on vibration response of microcracked compressor blades under variable working conditions. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 216, 109766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Castanier, M.P.; Pierre, C.; Poudou, O. Efficient nonlinear vibration analysis of the forced response of rotating cracked blades. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2009, 4, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.L.; Chen, Z.S.; Xiong, Y.P.; Yang, Y.M.; Tao, L.M. Nonlinear Dynamic Behaviors of Rotated Blades with Small Breathing Cracks Based on Vibration Power Flow Analysis. Shock Vib. 2016, 2016, 4197203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Mao, Z.; Wu, S.M.; Chen, X.F.; Yan, R.Q. Nonlinear dynamic behavior of rotating blade with breathing crack. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021, 16, 196–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.D.; Xiong, Y.W.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.H.; Fan, B.C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, J.H. Dynamic modeling of rotary blade crack with regard to three-dimensional tip clearance. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 544, 117414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.W.; Wei, Z.L.; Wu, B.; Zhang, J.H.; Dai, H.W. Nonlinear characteristics and radial-bending-torsional vibration of a blade with breathing crack. J. Sound Vib. 2025, 595, 118734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammer, D.C.; Schlack, A.L. Effects of nonconstant spin rate on the vibration of a rotating beam. J. Appl. Mech.-Trans. ASME 1987, 54, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.H. Dynamic-response of a pretwisted, tapered beam with nonconstant rotating speed. J. Sound Vib. 1991, 150, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.M.; Tsao, S.M. Dynamics of a pretwisted blade under nonconstant rotating speed. Comput. Struct. 1997, 62, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.H.; Chen, Y.P.; Zhang, W. Nonlinear vibrations of blade with varying rotating speed. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 68, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.P. Analysis on nonlinear oscillations and resonant responses of a compressor blade. ACTA Mech. 2014, 225, 3483–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiades, F.; Latalski, J.; Warminski, J. Equations of motion of rotating composite beam with a nonconstant rotation speed and an arbitrary preset angle. Mecc. J. Ital. Assoc. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2014, 49, 1833–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiades, F. Nonlinear dynamics of a spinning shaft with non-constant rotating speed. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018, 93, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvin, H. On parametrically excited vibration and stability of beams with varying rotating speed. Iran. J. Sci. Technol.-Trans. Mech. Eng. 2019, 43, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Chen, K.K.; Ma, H.; Duan, T.T.; Wen, B.C. Vibration response analysis of a cracked rotating compressor blade during run-up process. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 118, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, G.; Cui, F.; Xi, A. Nonlinear vibration analysis of composite blade with variable rotating speed using Chebyshev polynomials. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2020, 82, 103976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftejkhari, M.; Owhadi, S. Nonlinear dynamics of the rotating beam with time varying speed under aerodynamic loads. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2022, 10, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfan, S.; Anamagh, M.R.; Bediz, B.; Cigeroglu, E. Nonlinear resonances of axially functionally graded beams rotating with varying speed including Coriolis effects. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 107, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).