Abstract

We continue the presentation of new results in the calculus for interval-valued functions of a single real variable. We start here with the results presented in part I of this paper, namely, a general setting of partial orders in the space of compact intervals (in midpoint-radius representation) and basic results on convergence and limits, continuity, gH-differentiability, and monotonicity. We define different types of (local) minimal and maximal points and develop the basic theory for their characterization. We then consider some interesting connections with applied geometry of curves and the convexity of interval-valued functions is introduced and analyzed in detail. Further, the periodicity of interval-valued functions is described and analyzed. Several examples and pictures accompany the presentation.

1. Introduction

Interval arithmetic and interval analysis initiated with [1,2,3], in relation with the algebraic aspects of how arithmetical operations can be defined for intervals and how to solve problems like algebraic, differential, integral equations or others when intervals are involved. Recently, the interest for this topic increased significantly, in particular after the implementation of specific tools and classes in the C++ and Julia (among others) programming languages, or in computational systems like MATLAB or Mathematica. The research activity in the calculus for interval-valued or set-valued functions (of one or more variables) is now very extended, particularly in connection with the more general calculus for fuzzy-valued functions with applications to almost all fields of applied mathematics. One of the first contributions in the interval-valued calculus is [4] (1979). Similar ideas, in the more general setting of fuzzy valued functions (see, e.g., [5,6]), were developed in [7,8,9]. Contributions in this area are contained, among others, in the papers on gH-differentiability (see, e.g., [10,11,12,13,14,15]; see also [16,17]) and in papers on interval and fuzzy optimization and decision making (e.g, [11,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]). The multidimensional convex case is analyzed in [27].

This paper is part II of our work on the calculus for interval-valued functions. In part I, we have presented a discussion of partial orders in the space of real intervals, with properties on limits, continuity, gH-differentiability and monotonicity for functions .

In this part, we present a discussion on extremal points (Section 3), concavity and convexity (Section 4) with the use of gH-derivative for its complete analysis; an illustrative example is given in Section 5. Periodicity of interval valued functions is outlined in Section 6 and illustrated with the help of some famous plane curves; conclusions and hints for further work are given in Section 7.

2. Basic Results on Interval Valued Functions

We denote by the family of all bounded closed intervals in , i.e.,

The well-known midpoint-radius representation is very useful: for , define the midpoint and radius , respectively, by

so that and . We will denote an interval by or, in midpoint notation, by ; so

Using midpoint notation, the Minkowski-type operations, for and are:

- ,

- ,

- ,

- .

The -difference of two intervals always exists and, in midpoint notation, is given by

the -addition for intervals is defined by

Endowed with Pompeiu–Hausdorff distance , defined by

with and given also as (here, for , ), the metric space is complete.

In part I we have introduced a family of general partial order relations, in terms of the gH-comparison index, as follows:

Definition 1.

Given two intervals and and , (eventually and/or ) we define the following order relation, denoted ,

The space is a lattice [28,29]. A strict partial order and a strong partial order (asymmetric and transitive) are defined as follows:

Definition 2.

Given and and , (eventually and/or ) we define the following (strict) order relation, denoted ,

and the following (strong) order relation, denoted ,

We have seen in part I that, by varying the two parameters and , we can obtain a continuum of partial order relations for intervals and, in particular, we have the following equivalences [29]:

- (Part I, Proposition 6): If A and B are two intervals, then it holds that

- (1)

- ,

- (2)

- ,

- (3)

- ,

- (4)

- ,

- (5)

- .

- (Part I, Remark 2).

- (Part I, Proposition 7-e)are the sets of intervals dominated by A, dominating A and incomparable with A, respectively.

- (Part I, Proposition 8) for all ,

- (Part I, Proposition 9) For , and all ,where and are the opposite intervals of A and B.

- (Part I, Lemma 1) For the lattice with , and for any it is(1a) ⟹ (in the right part of implication, is not involved);(1b) ⟹ (in the right part of implication, is not involved);(2) ;(3) assuming , then .

Recall that, from

the reverse order is defined by , i.e.,

An interval-valued function is defined to be any with and for all . In midpoint representation, we write where is the midpoint value of interval and is the nonnegative half-length of :

so that

In the half-plane , , each interval is identified with the point .

We will consider the same example functions adopted in part I:

Example 1.

Let , , in midpoint notation, i.e., , . For we have and for it is ; the values of where the midpoint function is minimal or maximal are, approximately, with interval value and with interval value .

Example 2.

Let , , . Function is differentiable on with and is differentiable with for and ; at these two points the left and right derivatives exist: , , , . Function is gH-differentiable on (including the points and ) and ; right and left gH-derivatives exist at and , respectively. At the points , , and , the gH-derivatives are (approximately) , , , .

Limits and continuity can be characterized, in the Pompeiu–Hausdorff metric for intervals, by the -difference. Recalling Proposition 10 in part I, we have that, for a function , an interval and an accumulation point , we have

where the limits are in the metric . If, in addition, , we have

In midpoint notation, let and . Then the limits and continuity can be expressed, respectively, as

and

The gH-derivative for an interval-valued function, expressed in terms of the difference quotient by gH-difference, is defined as follows:

Definition 3.

Let and h be such that . Then the gH-derivative of a function at is defined as

if the limit exists. The interval satisfying (6) is called the generalized Hukuhara derivative of F (gH-derivative for short) at .

Recall that if is not differentiable or if its left and right derivatives do not have the same absolute value, then does not exist, but possibly the left and right gH-derivatives , exist and we have , , where and are the notations for left and right derivatives.

The right gH-derivative of F at is while, to the left, it is defined as . The gH-derivative exists at if and only if the left and right derivatives at exist and are the same interval. In terms of midpoint representation , the existence of the left and right derivatives and is required with (in particular if exists) so that

For a gH-differentiable function, higher-order gH-derivatives are defined analogously to the ordinary case, using the gH-differences applied to the gH-derivatives of previous order:

Definition 4.

Let be gH-differentiable on and and h be such that . The second order gH-derivative of at is defined as

if the limit exists.

The interval satisfying (8) is called the second order gH-derivative of F at .

Inductively, if the gH-derivatives of orders of exist on , denoted respectively by , the gH-derivative of order k is defined as

if the limit exists.

The interval satisfying (9) is called the k-order gH-derivative of F at .

In terms of notation, we will denote also by . The class of functions with continuous gH-derivatives of orders at all points for , will be denoted by ; in particular, will denote the class of continuous functions on (with right and left continuity at the extremal points).

Remark 1.

In the case of an interval-valued function in the form , , with where and (assuming that has at most a finite number of zeros in [a,b]) have derivatives , for , we have that has all the gH-derivatives , i=1,…,k. Indeed, either does not change sign or it changes sign at a finite set of points , we have that the absolute value function has derivative at all points with ; on the other hand, considering left and right derivatives at each , it is for all ; it follows that has always left and right derivatives with the same absolute values and this ensures that, at all points , . Considering that has the same form as , it is immediate to conclude inductively that the same form is valid for all .

3. Extrema of Interval Valued Functions

The three concepts of monotonicity defined in part I (simple, strict and strong), based on the orders , and , translate into different concepts of extrema. We will adopt the following terminology:

Definition 5.

If , we say that dominates with respect to the partial order (for short, -dominates ), or equivalently that is -dominated by .

We say that and are incomparable with respect to if both and are not valid.

Analogous domination rules are defined in terms of the strict and strong order relations and , respectively.

Remark 2.

Observe that if and , i.e., if and are -dominating each other, then and vice-versa, i.e., reciprocal dominance is equivalent to coincidence; the same remains true if the two orders for the dominance are obtained with different pairs , , and (), i.e., if and , then and vice-versa.

Let us now define the important definitions of order-based minimum and maximum points for an interval valued function.

Definition 6.

Let be an interval-valued function and . Consider the order with , . We say that, with respect to ,

- (a)

- is a local lattice-minimum point of F (-point for short) if there exists such that for all , i.e., if all around are -dominated by ;

- (b)

- is a local lattice-maximum point of F (-point for short) if there exists such that for all , i.e., if all around -dominate .

In case (a) we say that is a -min-point for F and in case (b) we say that is a -max-point.

Conditions (a) or (b) in the definition above imply that if there exists such that and then it is impossible to have nor (unless and ); this means that, except for trivial cases, if then and are -incomparable or coincident.

Remark that a lattice-type extremal value corresponds, locally, to the smallest or greatest elements in the lattice ; it is clear that condition (a) implies that a min-point of F is necessarily a local minimum of the midpoint function , while condition (b) implies that a max-point of F is a local maximum of . It follows that a min-point or a max-point of F are to be searched, respectively, among the minimum or the maximum points of the midpoint function . But this is not sufficient; indeed, lattice-type minimality and maximality, with respect to the partial order can be recognized exactly in terms of the three function , and , as we will see in this section.

It will be useful to explicitly write the conditions for -dominance of a general interval , with respect to the intervals and , that characterize the minimality and the maximality of a point (for min) or a point (for max). Without explicit distinction between strict or strong dominance, we have

and

Proposition 1.

Let be an interval-valued function. Then

- (a)

- is a min-point of F if and only if it is a minimum of and and it is a maximum of ;

- (b)

- is a max-point of F if and only if it is a maximum of and and it is a minimum of .

Proof.

In particular, for the order, obtained with , , we have , and the conditions to have a min-point are equivalent to having simultaneously a minimum for and (and automatically for ); on the other hand, max-point conditions are equivalent to have the same maximum points for and , in the ordinary sense.

The discussion above highlights the restricting notion of a lattice-extreme point, as it is not frequent that simultaneous extrema occur for the three functions , and . The following definition is more general, as it considers the possibility that intervals for different x are locally incomparable with respect to the actual order relation.

Definition 7.

Let be an interval-valued function and . We say that, with respect to the order and the corresponding strict order ,

(c) is a local best-minimum point of F (best-min for short) if:

(c.1) it is a local minimum for the midpoint function , and

(c.2) there exists and no point with such that ;

(d) is a local best-maximum point of F (best-max for short) if:

(d.1) it is a local maximum for the midpoint function , and

(d.2) there exists and no point with such that .

Remark 3.

The definitions above are clearly valid also for points coincident with one of a or b. It is also evident that a lattice-type extremum is also a best-type extremum.

Definitions of strict and strong (local) extremal points can be given by considering the strict or the strong orders associated to the lattice order .

Definition 8.

Let be an interval-valued function. With respect to an order and the associated strict order or strong order , we say that

- -

- a best-min point is a strict (respectively strong) best-minimum point if there exists and no point with (or , respectively);

- -

- a best-max point is a strict (respectively strong) best-maximum point if there exists and no point with (or , respectively).

Remark 4.

It is clear that the definitions of lattice-type and best-type extremality do not require any assumptions on continuity of the interval-valued function F on ; in the case of continuity (or left/right continuity) the existence of extreme points is also related to the local left and/or right monotonicity of F (with respect to the same partial order ).

In order to illustrate basic properties of the various concepts of min/max ()-extremality, we will consider a continuous function and will suppose that there exist two points such that is a local minimum point and is a local maximum point, in one of the types defined above.

In the half plane of points , , the intervals and have midpoint representation, respectively,

It is immediate that if is a lattice-minimum point, i.e., there exists a neighborhood of such that all satisfy (10), then no such is incomparable with ; analogously, if is a lattice-maximum point, i.e., there exists a neighborhood of such that all satisfy (11), then no such is incomparable with . We can express this fact by saying that the (local) min-efficient frontier for the -point is concentrated into the single interval ; analogously, the (local) max-efficient frontier for the max-point is concentrated into the single interval .

When instead and are best-type extrema and not lattice-type, then it is important to identify the intervals , in particular with x in a neighborhood of or , that are not min-dominated by (or do not max-dominate ); clearly, these are necessarily ()-incomparable with (or with , respectively).

Corresponding to a minimum and to a maximum point of F, we are then interested in identifying the locally (min/max)-efficient intervals and what we will call the local min or max efficient frontier for and around points and , respectively.

In the half plane the conditions to recognize the ()-based dominance and incomparability, assuming and , can be written by considering the two lines through with equations

and the two lines through with equations

For any define the following sets of points (sets of intervals in midpoint representation)

The intervals belonging to are -dominated by interval and the ones belonging to are -dominated by interval . If and are not lattice-type extrema of F, then there exist points around (respectively, ) such that (respectively, ). The first step in finding the efficient frontier for a strict minimum and a strict maximum is the following:

Proposition 2.

Let be an interval-valued function with values in the lattice endowed by a partial order , . Let be local strict best-min and local strict best-max points of F. Then, there exist , , and (all belonging to ) such that, respectively,

- 1.

- is incomparable with , for all , ;

- 2.

- is incomparable with , for all , .

Proof.

The proof follows immediately from the definition of strict best-min and best-max points and from the fact that the sets and are indeed intervals (eventually singletons). □

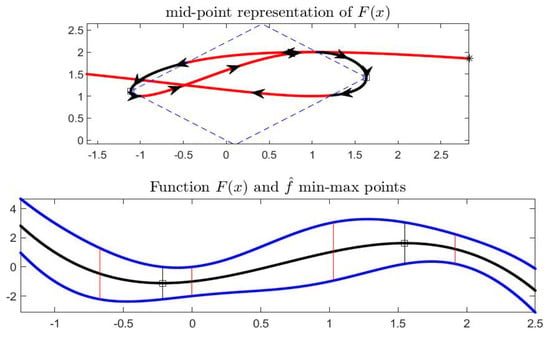

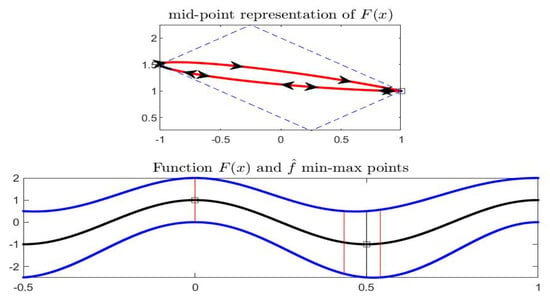

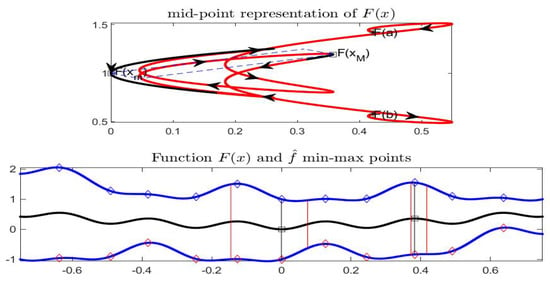

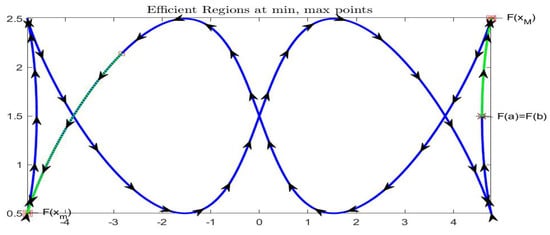

With reference to Example 1, function has a local minimum point and a local maximum point ; with the partial order , i.e., and , the locally non-dominated points corresponding to and are black colored in the top picture of Figure 1; we have and , marked with vertical red colored lines around and in the bottom picture.

Figure 1.

Local min and max points of in Example 1; function has a minimum point at and a maximum at . Black colored intervals in midpoint representation (top picture) are not dominated by for the local min and are not dominated by for the local max. They correspond to the domain subintervals and delimited by vertical red lines in the bottom picture.

The intervals for a minimum, or for a maximum, are not difficult to determine; for example, for a minimum point , a simple algorithm is to move on left and right of by small steps of length at points , until is not dominated by and at points , until is not dominated by ; if is the first dominated value on left and is the first dominated value on right, the extremes and are found by appropriate bisection iterations to refine the search up to a prescribed precision. An analogous procedure can be designed for a maximum point , by moving on the left and right until points and with and dominated by ; in this case the extremes and are found by bisections up to a prescribed precision.

A first consequence of Proposition 2 is a sufficient condition for a lattice-type extremal point.

Proposition 3.

Let ; if (respectively, ) is a minimum point (a maximum point) of function and (or ) then is a lattice min-point (respectively is a lattice max-point) of and vice versa.

Proof.

Indeed, in this cases, we have and . □

A second consequence of the last proposition is that the efficient intervals , relative to the best-min point or to the best-max point , in the case where they are not lattice extrema, are to be searched among the points and , respectively.

The final step is now to characterize the points of and that contain, respectively, , and are such that all the corresponding define the local efficient frontier of F around and , respectively.

We start with a formal definition of the min/max efficient frontier:

Definition 9.

Let be an interval-valued function and let be local strict best-min and local strict best-max points of F with respect to the partial order , .

- (a)

- The (local) min-efficient frontier of function F associated to the best-min point (or to the best-min interval-value ) is the set of interval-values such that:

- (a.1)

- ,

- (a.2)

- if and then and are ()-incomparable,

- (a.3)

- no other set containing has property (a.2).

The set of points such that are the local min-efficient points corresponding to and is denoted by .

- (b)

- The (local) max-efficient frontier of function F associated to the best-max point (or to the best-max interval-value ) is the set of interval-values such that:

- (b.1)

- ,

- (b.2)

- if and then and are ()-incomparable,

- (b.3)

- no other set containing has property (b.2).

The set of points such that are the local max-efficient points corresponding to and is denoted by .

Clearly, the efficient frontiers or are subsets of the interval in Proposition 2; but their characterization is not easy, as we can imagine in cases where the function has possible inflexion or angular points, tangency of high order, multiple nodes, fractal-like or complex pathological patterns (see, e.g., [30]). In those cases it is not immediate to determine which points are not dominated by others of the same interval, or possibly the efficient frontiers may not be intervals.

In the case where function represents locally a convex plane curve, standard results in elementary differential geometry (see, e.g., [31], chapter 2) are of help in our context. We recall briefly some facts.

Let be the curve, in the half-plane with parametric equations , and parameter and assume that the curve is simple (no multiple points) and differentiable (i.e., both and are differentiable at internal points); one says that the curve has the convexity property if each of its points is such that the curve lies on one side of the tangent line to this point. In our setting, the convexity of is required only locally, by considering the restriction of to points around (or ). More precisely, let’s fix the notion of local convexity of by distinguishing the case of a minimum to the case of a maximum point.

Assumption 1.

For a min point (not a lattice min) we will assume that there exist (not both equal to zero) such that the curve corresponding to the restriction of to the interval is simple and convex; this happens if the portion of plane on right of the curve, i.e., the set

is convex; in this case, the following portion of the half plane is convex and bounded

where , and , .

It is not restrictive to assume that interval is the biggest subinterval of where the curve is locally convex.

Assumption 2.

For a max point (not a lattice max), assuming the existence of such that the curve on interval is simple and convex, we obtain that the portion of plane on left of the curve, i.e.,

is convex; in this case, the following set is convex and bounded

where, this time,

,

and similarly for and in terms of .

It is not restrictive to assume that interval is the biggest subinterval of where the curve is locally convex.

Under Assumptions 1 or 2 (using the same notation) we can prove the following results:

Proposition 4.

Let be a partial order on and let be such that is a local min point of and Assumption (A) is satisfied. Then there exist two points with and such that, for ,

- (1)

- either maximizes and minimizes ,

- (2)

- or minimizes and maximizes .

Furthermore, interval is the local efficient frontier of Definition 9.

In particular, if and are internal to the local convexity region and , are differentiable, then

Proof.

Consider the two lines with equations and ; points of the curve in common with one of the two lines will satisfy the equations and . Solving for and one obtains and and at such common points the two lines have equations: and . Now, by condition (A), the intercepts and , as functions of x, are monotonic around ; then the maximum value of the is attained at a point and the has a minimum value attained at a point .

By taking and , it is clear that conclusions (1) or (2) are satisfied.

If the points and are internal to the convexity region , then the derivatives of and at the attained max and min points (respectively) will be zero; this proves conditions (17). They mean that the line of equation is tangent to the curve at point and the line is tangent to at point .

The proof concludes by observing that the efficient region is exactly the interval ; indeed, by local convexity,

- (a)

- no points with are dominated (or dominate) other points in the same interval, and

- (b)

- points with and (if any) are dominated by and by , respectively.

□

Proposition 5.

Let be a partial order on and let be such that is a local max point of and Assumption (B) is satisfied. Then there exist two points with and such that, for ,

- (1)

- either minimizes and maximizes ,

- (2)

- or maximizes and minimizes .

Furthermore, interval is the local efficient frontier of Definition 9.

In particular, if and are internal to the local convexity region and , are differentiable, then

Proof.

We can proceed analogously to the proof of Proposition 4; in this case, under condition (B), two points and are obtained by minimizing the intercept and by maximizing , respectively. Taking and , the tangency conditions with the curve are exactly the ones in (18). □

A procedure for the efficient frontiers corresponding to a minimum or maximum point can be obtained in a similar way as for determining the intervals , or ; e.g., for a minimum, we move on left and right of by small steps and , until the monotonicity of intercepts or is interrupted in two consecutive points or, equivalently, until a point is found which dominates the next one. Also in this case, we can refine the search by appropriate bisections.

A complete example with several possible situations is presented in Section 5.

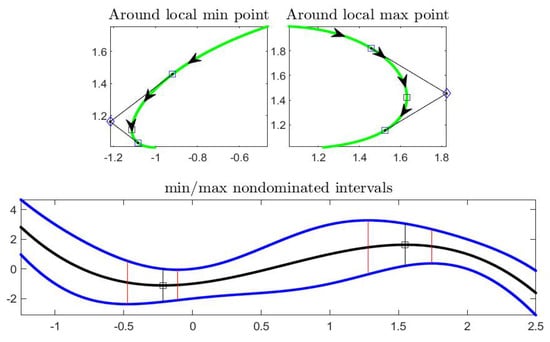

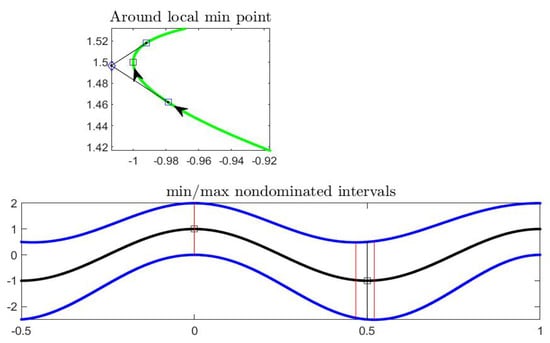

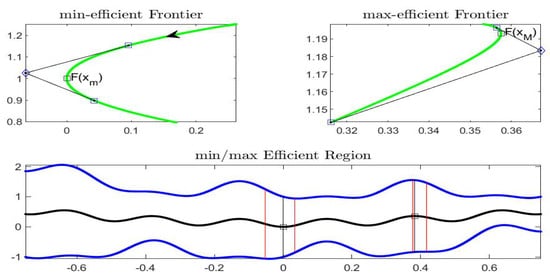

With reference to Example 1, the efficient frontiers are and (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Efficient frontiers for min and max points of in Example 1. The top pictures show the efficient frontier for (left) and for (right) with the tangent lines to the curve F. In the bottom picture, the efficient frontiers are delimited by vertical red segments containing the min and the max points.

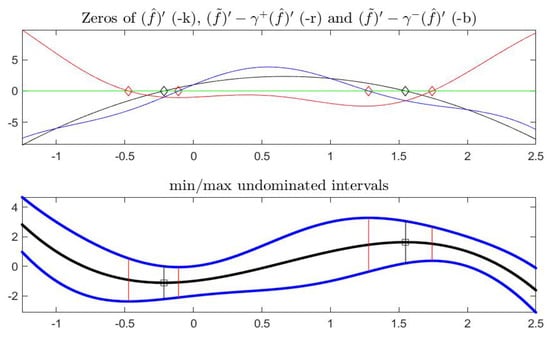

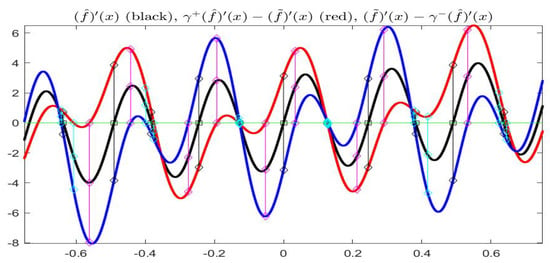

In the next Figure 3, the first derivatives of the three functions , and are visualized (the second is changed in sign with respect to the notation in conditions (A) and (B)); by checking appropriate monotonicity of the three derivatives, we see that condition (A) is satisfied in a neighborhood of and condition (B) is valid around . Corresponding to the relevant points, the three derivatives are zero, according to Propositions 4 and 5 (picture on top).

Figure 3.

Efficient frontier for min and max points of in Example 1. The top picture reproduces the derivatives of the three relevant functions , and .

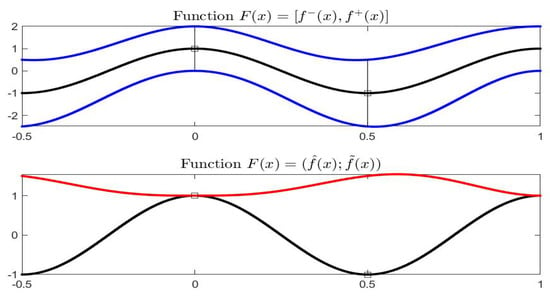

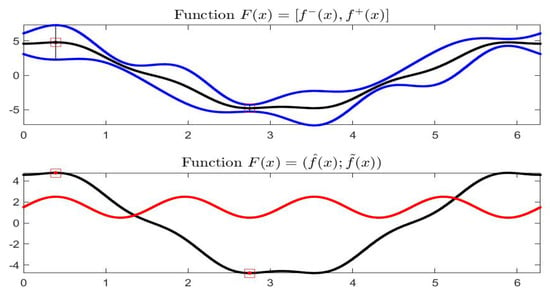

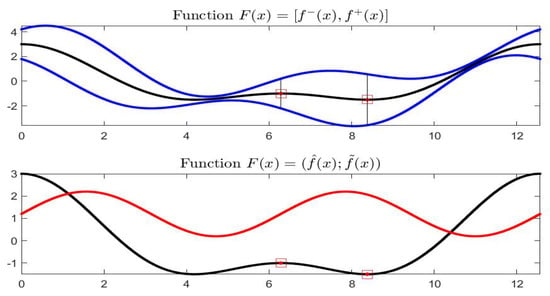

Consider the function (midpoint notation) of Example 2 with . Figure 4 contains the graph of in interval form (top picture) and in midpoint form (bottom).

Figure 4.

Interval (top) and midpoint (bottom) representations of function in Example 2.

The point with is a local maximum of function and the point with is a local minimum of .

Let us chose, e.g., and ; Figure 5 shows the ()-dominance for the interval-values with x around and . In midpoint representation, appears on the left portion of the top picture and on the right portion; the parallelogram contains the intervals (in red color) of the graph of F that are ()-dominated by and ()-dominated by . The bottom picture marks the intervals and and shows the intervals and corresponding to the points around and with dominated interval-values. Clearly, results in a local (and global on the considered domain of F) lattice-maximum point of F, while is a local (and global) best-minimum point. Indeed, we have that reduces to the single point while is the interval , approximated numerically as it is depending on the actual values of and .

Figure 5.

Local min and max points of F(x) in Example 2; function has a minimum point at and a maximum at . Black colored intervals in midpoint representation (top picture) are not dominated by for the local min and are not dominated by for the local max. They correspond to the domain subintervals delimited by vertical red lines in the bottom picture.

The local min-efficient frontier corresponding to the best-min point , i.e., the points in , can be easily computed (see below) and are pictured in Figure 6. In the top picture, the green points are the ones min-dominated by , corresponding to the points in ; the efficient frontier is identified in the mid-point graph of by the green points intercepted by the lines with angular coefficients , and “tangent” to the graph of F (see below for the details). In the bottom part of the same Figure, the min-efficient frontier is evidenced by vertical lines around , corresponding to the points .

Figure 6.

Efficient frontiers for min and max points of in Example 2. The top picture shows the efficient frontier for with the tangent lines to the curve F. In the bottom picture, the efficient frontiers are delimited by vertical red segments containing the min and max points (the max point is lattice type maximum).

We conclude this section to see how local extremality of a point (minimum) or (maximum) is connected to the left and/or right gH-derivatives , or to the gH-derivative if the two are equal.

Let and be a partial order. Suppose first that , exists (here ). We have seen that if is a local minimum or maximum point, then so that ; as a consequence, a necessary condition for a local min or max at a point of differentiability is that . If also (i.e., if ), then . Otherwise, if , by the continuity of , there exists a neighborhood of where is ()-incomparable with . So, we have the following Fermat-like property:

Proposition 6.

Let , , F gH-differentiable at and be a partial order on .

- (1)

- If is a lattice extremum for F (a lattice-min or a lattice-max point), then ;

- (2)

- If is a best-extremum for F (a best-min or a best-max point), then .

Also contrapositive versions of the statements are evident: if , then is not a local extremum for F.

In the cases where F has left or right gH-derivatives at (or they are not equal), necessary conditions for a lattice-min or a best-min (respectively, a lattice-max or a best-max) can be easily deduced according to Proposition 14 in part I.

Proposition 7.

Let , and be a partial order on . Suppose that F has left and right gH-derivatives at (if or we consider only the right or the left gH-derivatives, respectively)

- (1.a)

- If is a lattice minimum point for F, then and ;

- (1.b)

- If is a lattice maximum point for F, then and ;

- (2.a)

- If is a best-minimum point for F, then .

- (2.b)

- If is a best-maximum point for F, then .

The following are sufficient conditions based on the “sign” of left and right gH-derivatives, analogous to the well known situation for single-valued functions.

Proposition 8.

Let , and be a partial order on . Suppose that F has left and right gH-derivatives at (if or we consider only the right or the left gH-derivatives, respectively)

- (a)

- If and , then is a best minimum point for F;

- (b)

- If and , then is a best maximum point for F.

4. Concavity and Convexity of Interval-Valued Functions

We have three types of convexity, similar to the monotonicity and local extremum concepts.

Definition 10.

Let be a function and let , be a partial order for intervals. We say that

- (a-i)

- F is ()-convex on if and only if and all ;

- (a-ii)

- F is ()-concave on if and only if and all .

- (b-i)

- is strictly ()-convex on if and only if and all ;

- (b-i)

- F is strictly ()-concave on if and only if and all .

- (c-i)

- F is strongly ()-convex on if and only if and all ;

- (c-iii)

- F is strongly ()-concave on if and only if and all .

The convexity of a function is related to the concavity of function , as follows:

Proposition 9.

Let and be a given partial order with , . Consider also the partial order . Then is ()-convex if and only if is ()-concave. In particular, if , then F is ()-convex if and only if is ()-concave.

Proof.

We know (part I, Proposition 9) that, for intervals , it is if and only if ; in the last partial order, the roles of and are interchanged by changing their sign so that and . The proof follows immediately. □

The following result expresses the ()-convexity of F in terms of the convexity of functions , and :

Proposition 10.

Let and be a given partial order; then

- 1.

- F is ()-convex if and only if is convex, is concave and is convex;

- 2.

- F is ()-concave if and only if is concave, is convex and is concave.

Proof.

For 1., let and and denote . Condition means

From the first inequality, is convex; the second inequality becomes

i.e., is concave. The third inequality is

i.e., is convex. To prove 2., we can proceed in a similar way. □

Strict ()-convexity (respectively, concavity) of F in terms of functions , and can be easily deduced: in this case, the midpoint function is strictly convex (respectively, concave), is concave (respectively, convex) and is convex (respectively, concave). Strong convexity of F corresponds to strict convexity and/or concavity of , and (in the right way).

It is interesting to remark that an interval-valued function which is both ()-convex and ()-concave on exhibits a strong linearity, in the sense that both and are linear on ; indeed, from one obtains

Proposition 11.

Let be ()-convex or ()-concave; then F is continuous on .

Proof.

From Proposition 10, the three functions , and are convex or concave, hence they are continuous on the internal points of . As and both and are continuous, we have that and are continuous and F is continuous. □

From Proposition 10, several ways to analyze ()-convexity (or concavity) in terms of the first or second derivatives of functions , and can be easily deduced.

Proposition 12.

Let with differentiable and ;

- 1.

- If the first order detivatives and exist, then:

- (1-a)

- F is ()-convex on if and only if , and are increasing (nondecreasing) on ;

- (1-b)

- F is ()-concave on if and only if , and are decreasing (nonincreasing) on ;

- 2.

- If the second order derivatives and exist and are continuous, then:

- (2-a)

- F is ()-convex on if and only if , and on ;

- (2-b)

- F is ()-concave on if and only if , and on .

Proof.

The proof follows from well-known results in elementary calculus. □

In order to connect concavity and convexity with the monotonicity of the gH-derivative and, for a partial order with , with the “sign” of the second-order gH-derivative, we need the following well known result on real convex functions:

Lemma 1.

For a function to be convex on , a necessary and sufficient condition is that for all the incremental function , defined by is nondecreasing for . Furthermore, g admits left and right derivatives at any and .

Proof.

Consider (both different from ); after simple manipulations, we have

On the other hand, from the convexity of g, we have for all and, taking (this is not restrictive because the right-hand side in (19) is symmetric with respect to , and ) we obtain and, combining with the second line in (19),

To prove the last part, the incremental function is nondecreasing and admits left and right limits at , with ; on the other hand, clearly, and and this completes the proof. □

Proposition 13.

Let for all . Consider the incremental functions of and , defined for , by

and let and be the incremental functions of and respectively, given by

Then

- 1.

- F is ()-convex on if and only if , and are nondecreasing in .

- 2.

- F is ()-concave on if and only if , and are nonincreasing in .

Proof.

From Proposition 10, the three functions , and are convex (in case 1.) or concave (in case 2.); by virtue of Lemma 1 their incremental functions , and are either non decreasing (in case 1.) or non increasing (in case 2.) and the conclusion follows. □

Proposition 14.

Let and let , . If F is ()-convex or ()-concave on , then and both exist on . If then also and .

Proof.

We know that F is ()-convex if and only if , and are convex; from the second part of Lemma 1, their left and right derivatives exist so that also and exist. It follows that and with , , . If then , and , so exists. □

Remark 5.

Analogously to the relationship between the sign of second derivative and convexity for ordinary functions, we can establish conditions for convexity of interval functions and the sign of the second order gH-derivative ; for example, a sufficient condition for strong -convexity (i.e., with respect to the partial order with ) is the following (compare with Proposition 12):

- 1.

- If then is strongly concave at .

- 2.

- If then is strongly convex at .

A simple case is the function of Example 2, for which the second-order gH-derivative exist for all with . is strongly convex for and strongly concave for ; if we have so that cannot be strongly convex nor concave.

5. Complete Discussion of an Example

We conclude the presentation of our results with a complete discussion of the following example.

Complete Example: function is defined by and for . In this example, we have chosen , . Remark that both and are differentiable so that, in midpoint notation, the first order gH-derivative is and the second order gH-derivative is (see [12,14]).

All computations are performed with a precision of at least five decimal digits.

Internally to , we consider eleven points where is locally minimal or maximal (we will ignore the first and last ones as too near to boundaries a, b). They are marked in Figure 7 by a blue diamond symbol. They are denoted corresponding to the rows in Table 1.

Figure 7.

Interval-valued function (top) of the Complete Example. Bottom picture gives functions (black color) and (red).

Table 1.

Relevant points of in the Complete Example.

The two points and , corresponding to a local minimum and maximum of and marked, in the -plane, with a square symbol, will be analyzed in detail. The vertical segments in top of Figure 7 represent intervals and .

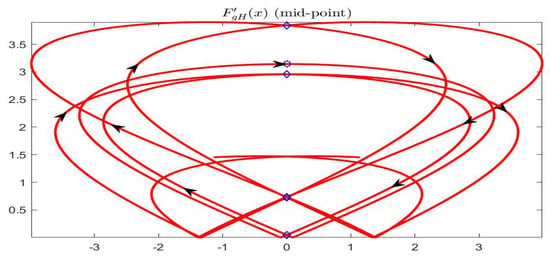

Figure 8 gives the first order gH-derivative of ; remark that, according to fourth column in Table 1, we always have and .

Figure 8.

Complete Example: first order gH-derivative in interval form; black curve is .

In Figure 9 the gH-derivative is pictured in midpoint half plane ; the points where are marked in correspondence with the value on the abscissa (compare also with Table 1).

Figure 9.

Complete Example: first order gH-derivative in midpoint form.

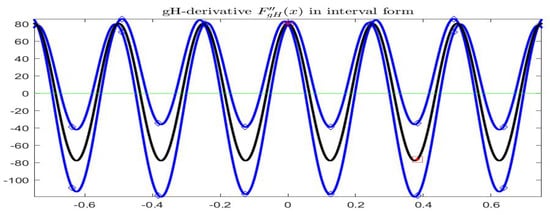

The second order gH-derivative, represented in Figure 10, shows that the intervals , as expected, are entirely positive at the minima and negative at the maxima. Remark that in no points the first and second derivatives of are simultaneously zero.

Figure 10.

Complete Example: second order gH-derivative in interval form; the black curve is .

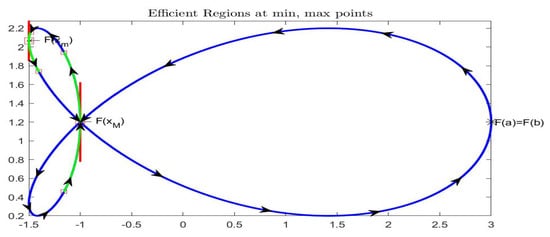

In this example, where both and have continuous second order derivative, the convexity region is particularly simple to identify, due to a well known Theorem based on the sign of the curvature of curve associated to . We consider the following function (its sign coincides with the sign of the curvature of at x). We then search for the points, on the left and right of , at which the sign of has the same sign of . Analogous result is valid for (see Chapter 6 in [32] for the general result). In our example we find the interval around and the interval around (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Complete Example: local convexity of curve corresponding to and (top picture). In the bottom picture, the values of x corresponding to local convex portion of are delimited by red vertical lines.

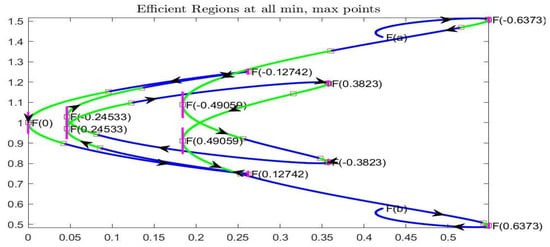

From the local convexity of the curve , the efficient regions corresponding to and are computed under Assumption 1 for min and Assumption 2 for max; the resulting intervals, illustrated in Figure 12, are, respectively, around and the interval for .

Figure 12.

Complete Example: (top) efficient regions corresponding to and (top picture), obtained by tangency conditions. (Bottom) the efficient regions around the min and max points are delimited by vertical red lines.

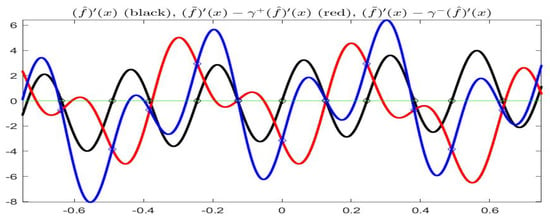

The next Figure 13 gives the three functions , , ; as we have seen in part I, their sign gives information on the monotonicity of . In particular, if all three functions (observe that the second function is changed in sign with respect to the properties in part I) have the same sign (hence are also not zero) at a point x, then is strictly increasing or decreasing with respect to the partial order . The same information can be eventually deduced from the sigh of the tree derivatives , , , given in Figure 14; at points where the three derivatives have different signs, then function is not -monotonic.

Figure 13.

Complete Example: functions , , .

Figure 14.

Complete Example: functions , , .

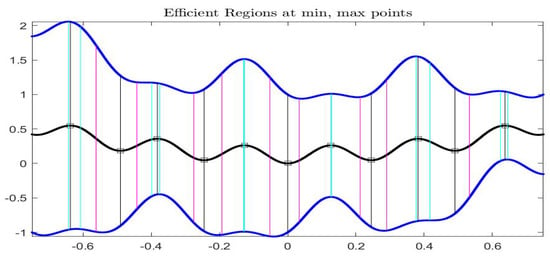

The results of our analysis, as described for the min and max points and , are visualized in Figure 15, giving the midpoint representation of . Here, we see the position of point , with the delimiters , of the efficient region (in green color); analogously, the position of the max point is evidenced, with the delimiters , of the efficient region . Clearly, the two points correspond to local best-min and best-max points (not of lattice type).

Figure 15.

Complete Example: function is represented in midpoint form, together with the efficient points corresponding to and .

The last three Figures summarize, respectively, the computations for all the local minima and maxima considered in Table 1. The first Figure 16 reproduces in interval form, with the visualization of the six local maxima and the five local minima, classified according to the computations. The points , in the first column of Table 1, together with corresponding interval values (as in the second column) are marked with a vertical segment in black color. Correspondingly, the efficient regions are delimited by vertical lines (cyan-colored for max points and magenta for min points). There are two local maxima, corresponding to with and with which are lattice max-points: the efficient frontier coincides with the point itself and the two maximal intervals dominate locally all the near intervals (in the figure, the black and cyan vertical lines are coincident). This is also visible in Figure 17 in terms of the values of the three derivatives , and evaluated at and at the points defining the efficient regions: for the two lattice maxima, the three derivative are zero, while in the other minima or maxima only is zero and the other two derivatives do not have (at least generally) the same sign (but one or both may possibly be zero).

Figure 16.

Complete Example: function is represented in interval form, and all the zeros of are classified as min or max points; all the efficient regions are delimited by vertical lines (cyan-colored for six max points and magenta for five min points). The black vertical lines are the intervals , .

Figure 17.

Complete Example: functions , and are evaluated at classified min and max points and the corresponding efficient frontiers are delimited by vertical lines (cyan-colored for max and magenta for min points).

Finally, Figure 18 summarizes all the computations by the midpoint visualization of our function , with all the points and the corresponding efficient regions.

Figure 18.

Complete Example: function is represented in midpoint form, and all local minima (five points) and maxima (six points) are marked together with corresponding efficient regions.

6. An Outline of Periodic Interval-Valued Functions (and Famous Plane Curves)

Considering points where the trajectory of an interval-valued function crosses itself, i.e., , exist with (equivalently and , it follows that periodicity of F is also easy to describe.

Definition 11.

A function is said to be periodic if, for some nonzero constant , it occurs that for all with (i.e., for all ). A nonzero constant T for which this is verified, is called a period of the function and if there exists a least positive constant T with this property, it is called the fundamental period.

Obviously, if F has a period T, then this also implies that: , so that and , for all , i.e., and are periodic with period T; remark that if T is the fundamental period of F, this does not necessarily imply that T is fundamental period for both and . On the other hand, the periodicity of and does not necessarily imply the periodicity of F.

Proposition 15.

Let be a continuous function such that with periodic of period and of period . Then it holds that:

- (1)

- if the periods and are commensurable, i.e., (, such that p and q are coprime) then the function F is periodic of period , i.e,. T is the least common multiple between and (i.e., );

- (2)

- if the periods and are not commensurable, i.e., , then function F is not periodic.

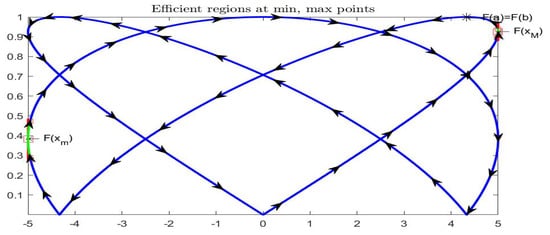

Periodic Example 1: consider the function defined by periodic functions and . Figure 19 and Figure 20 picture for . On this interval, function has two minimal and two maximal points (see bottom picture in Figure 19). We have chosen with and with , located in Figure 20, where also the points corresponding to efficient regions and are given in green color. Here and giving the -order.

Figure 19.

Periodic Example 1: Function is pictured on top and functions , on bottom. Marked points correspond to and , where the two functions are differentiable.

Figure 20.

Periodic Example 1: midpoint representation of function ; marked points are and and the efficient and points are marked in green color.

Periodic Example 2 (Siamese fishes): function is defined by periodic functions and . Figure 21 and Figure 22 picture for . Internal to this interval, function has two minimal and three maximal points (see bottom picture in Figure 21); we have chosen with and with , located in Figure 22, where also the points corresponding to efficient regions and are given in green color. Here and .

Figure 21.

Periodic Example 2 (Siamese fishes): function is pictured on top and functions , on bottom. Marked points correspond to and , where the two functions are differentiable.

Figure 22.

Periodic Example 2 (Siamese fishes): midpoint representation of function ; marked points are and and the efficient and points are marked in green color.

Periodic Example 3 (big fish): function is defined by periodic functions and . Figure 23 and Figure 24 picture for . Internal to this interval, function has two minimal and one maximal points (see bottom picture in Figure 23); we have chosen with and with , located in Figure 24, where also the points corresponding to efficient regions and are given in green color. Here and .

Figure 23.

Periodic Example 3 (big fish): function is pictured on top and functions , on bottom. Marked points correspond to and , where the two functions are differentiable.

Figure 24.

Periodic Example 3 (big fish): midpoint representation of function ; marked points are and and the efficient and sets of points are marked in green color.

7. Conclusions and Further Work

In the first part of this work (part I, see [33]) we have introduced a general framework for ordering intervals, using a comparison index based on gH-difference; the suggested approach includes most of the partial orders proposed in the literature and preserves important desired properties, including that the space of real intervals is a lattice with the bounded property (all bounded sets of intervals have a supremum and an infimum interval).

The monotonicity properties are then defined and analyzed in [33] in terms of the suggested partial orders; the relevant connections with gH-derivative are also established.

In this paper (part II), we define concepts related to extremal points (local/global minimum or maximum), using the same general partial orders described in part I, and we analyze the important concepts of concavity and convexity; furthermore, we establish the connections between extremality, convexity, and concavity with first-order and second-order gH-derivatives.

Interesting connections with differential geometry and with periodic curves (as in [30,31,32]) are sketched and briefly analyzed.

We consider these notes as a first step in the mathematical analysis for interval functions of a single variable. Appropriate extensions to study the case of interval functions of more variables (initiated with a recent paper [14]) have been considered and will be the subject of future research.

As we have said in the introduction to part I, the scope of this paper is not to discuss problems in the arithmetic with intervals, extended intervals (Kautcher arithmetic), modal intervals, directed intervals (these are some of the terms and approaches proposed in the very extended literature related to interval analysis) or in the structure of spaces of intervals (semi-linearity, quasi-linearity).

Our setting here is the standard interval analysis, based on Minkowski-type operations (also said to be based on the extension principle), with the supplement of gH-difference and gH-addition (not to be substitutes of standard difference and addition). Surely, a well-documented survey to describe and compare the different approaches raised since the origins of intervals in various fields of mathematics should be of great interest and importance, in particular, to reconstruct the (seemingly different) motivations and to describe the (in most cases equivalent) proposals presented in the literature. A specifically dedicated paper in this sense is one of our future research interests.

Several additional properties and applications can be possibly established, in particular with reference to specific problems and questions such as, e.g., the study of almost-periodicity for interval-valued functions in constructive mathematics (see [34,35,36]) or the solution of interval differential equations (IDE), including the extension of ordinary and partial differential equations to the interval-valued case using gH-derivatives (examples of reflected and advanced differential equations of special type are described, e.g., in [37]).

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally in writing the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Moore, R.E. Interval Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.E. Method and Applications of Interval Analysis; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.E.; Kearfott, R.B.; Cloud, M.J. Introduction to Interval Analysis; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, S. Calculus for interval functions of real variable. Computing 1979, 22, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Okuda, T.; Asai, K. On Fuzzy Mathematical Programming. J. Cybern. 1974, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdegay, J.L. Progress on Fuzzy Mathematical Programming: A personal perspective. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2015, 281, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L. A generalization of Hukuhara difference and division for interval and fuzzy arithmetic. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2010, 161, 1564–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L.; Bede, B. Generalized Hukuhara differentiability of interval-valued functions and interval differential equations. Nonlinear Anal. 2009, 71, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L. A generalization of Hukuhara difference. In Soft Methods for Handling Variability and Imprecision; Dubois, D., Lubiano, M.A., Prade, H., Gil, M.A., Grzegorzewski, P., Hryniewicz, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bede, B.; Stefanini, L. Generalized differentiability of fuzzy-valued functions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2013, 230, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalco-Cano, Y.; Román-Flores, H.; Jiménez-Gamero, M.D. Generalized derivative and π-derivative for set-valued functions. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181, 2177–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalco-Cano, Y.; Rufian-Lizana, A.; Roman-Flores, H.; Jimenez-Gamero, M.D. Calculus for interval-valued functions using generalized Hukuhara derivative and applications. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2013, 219, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalco-Cano, Y.; Rufian-Lizana, A.; Roman-Flores, H.; Osuna-Gomez, R. A note on generalized convexity for fuzzy mappings through a linear ordering. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2013, 231, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L.; Arana-Jimenez, M. Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions for interval and fuzzy optimization in several variables under total and directional generalized differentiability. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2019, 362, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, L.; Bede, B. Generalized fuzzy differentiability with LU-parametric representations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2014, 257, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bede, B. Mathematics of Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Logic; Series: Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing n. 295; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bede, B.; Gal, S.G. Generalizations of the differentiability of fuzzy-number-valued functions with applications to fuzzy differential equations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2005, 151, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalco-Cano, Y.; Lodwick, W.A.; Osuna-Gomez, R.; Rufian-Lizana, A. The Karush-Kuhn-Tucker optimality conditions for fuzzy optimization problems. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Mak. 2016, 15, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Gomez, R.; Chalco-Cano, Y.; Hernandez-Jimenez, B.; Ruiz-Garzon, G. Optimality conditions for generalized differentiable interval-valued functions. Inf. Sci. 2015, 321, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Gomez, R.; Chalco-Cano, Y.; Rufián-Lizana, A.; Hernandez-Jimenez, B. Necessary and sufficient conditions for fuzzy optimality problems. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2016, 296, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Pal, T.K. On comparing interval numbers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 127, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Pal, T.K. Fuzzy Preference Ordering of Interval Numbers in Decision Problems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Gong, D.; Zeng, X.; Geng, N. An ensemble framework for assessing solutions of interval programming problems. Inf. Sci. 2018, 436–437, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C. The Karush-Kuhn-Tucker optimality conditions in an optimization problem with interval-valued objective function. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 176, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C. The optimality conditions for optimization problems with convex constraints and multiple fuzzy-valued objective functions. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Mak. 2009, 8, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.L.; Sorini, L.; Stefanini, L. A new approach to linear programming with interval costs. In Proceedings of the FUZZ-IEEE 2017 Conference, Naples, Italy, 9–12 July 2017; Article Number 8015661. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanini, L.; Bede, B. A new gH-difference for multi-dimensional convex sets and convex fuzzy sets. Axioms 2019, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.L.; Stefanini, L. A comparison index for interval ordering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium series on Computational Intelligence (FOCI 2011), Paris, France, 11–15 April 2011; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, M.L.; Stefanini, L. A comparison index for interval ordering based on generalized Hukuhara difference. Soft Comput. 2012, 16, 1931–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovenski, V. Modeling of Curves and Surfaces with MATLAB; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, C. Elementary Differential Geometry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, A.; Abbena, E.; Salamon, S. Modern Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces with Mathematica, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanini, L.; Guerra, M.L.; Amicizia, B. Interval analysis and calculus for interval-valued functions of a single variable. Part I: Partial orders, gH-derivative, monotonicity. Axioms 2019. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Besicovitch, A.S. Almost Periodic Functions; Dover Publications Inc.: Mineola, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Brom, J. The theory of almost periodic functions in constructive mathematics. Pac. J. Math. 1977, 70, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, D.; Shah, R.; Li, T. Almost periodic and asymptotically almost periodic functions: Part I. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, K.-S.; Li, T. Oscillatory and periodic solutions of differential equations with piecewise constant generalized mixed arguments. Math. Nachrichten 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).