Abstract

In this article, we show how to define a metric on the finite power multisets of positive real numbers. The metric, based on the minimal matching, consists of two parts: the matched part and the mismatched part. We also give some concrete applications and examples to demonstrate the validity of this metric.

1. Introduction

A multiset, unlike a Cantorian set, is a collection of elements whose instances might be multiple (the number of its instances of an element is named multiplicity). The cardinality of a multiset A is defined by the sum of the multiplicities with respect to their corresponding elements and is denoted by . For example, the cardinality of multiset is 7, i.e., . Though unconventional, the theory of multisets has well been developed (see Reference [1]) and it also has various applications in many situations (see Reference [2]). From practical point of view, multisets are easier to represent or simulate than mathematical objects with multiple instances. In this article, we mainly focus on the finite power multisets of positive real numbers.

Let denote the set of all positive real numbers. Let denote the set of natural numbers including 0. Let power multiset denote the set of all the sub-multisets of . Suppose is an arbitrary set of some sub-multisets in ( each multiset is finite) of . We call a finite power multiset of positive real numbers. The main result in this article is to define a metric on based on the concept of minimal matching. The distance between any two multisets consists of two separated parts: the matched part and mismatched part. Matching has been an important problem and has wide applications in the fields of artificial intelligence, graph theories, and operation research (see References [3,4,5]). In this article, we come up with a new metric which is based on the concept of minimal matching. This metric is used to measure the distance between any two finite multisets of positive real numbers. Though what we define in this article is a standard metric, the whole setting could also be extended to other generalized metrics, for example, –metric (see Reference [6]).

2. Definitions

In this section, we introduce and present multisets via the forms of functions. The basic concepts could be found in many textbooks or journals (see, e.g., References [7,8]). Let denote the set , i.e., the set of all the functions from to . Let denote the domain of a function f. Let set be the non-zero domain of f.

2.1. Multisets

Let denote all the finite multi-subsets of , i.e., . Each element in is simply named a multiset in this article. If for all , , we say f is a multi-subset of g, denoted by . Let be arbitrary.

Definition 1.

(Empty Multiset) We call the zero function in the empty multiset.

Definition 2.

(Equality =) if and only if and .

Definition 3.

(Intersection ∧) The intersection of f and g, denoted by the function , is defined by for all .

Definition 4.

(Union ∨) The union of f and g, denoted by the function , is defined by for all .

Definition 5.

(Difference ⊖) Exclusion of g from f, denoted by the function , is defined by .

Each multiset f in could be uniquely represented by the following descending form (named a representative descending form):

or in brief ; or by the following ascending form (named a representative ascending form):

or in brief , where and and for all . Let .

Definition 6.

(Descending) Define the element in f by function as follows:

Definition 7.

(Ascending) Define the element in f by function as follows:

2.2. Background

In this article, we show how to define a metric on (see Introduction). For any Cantorian set S, we use to denote the cardinality of S. Let d be an arbitrary metric on satisfying

for all . Observe that d is a metric (for our generalization purpose) on , which lays a foundation for our latter definition of a metric on . Let be arbitrary. Let denote the set of all the functions from A to B, in which the repeated elements are deemed distinct.

Example 1.

Suppose and , and . Then, . For clarity, one could simply associate A and B with their ranked multiplicities as follows: and and ρ could also be represented by . To save space, we simply use for the representation in this article.

For any function , we use and to denote its domain and codomain, respectively. For the previous example, and . We use to denote the image , in particular to denote the image of and to denote the pre-image of S. If , we use to denote whose domain is restricted to S. One candidate in mind is .

Definition 8.

(Bijective embeddings) Define

Example 2.

Suppose ρ is defined in Example 1. Since , by the above definition, one has . On the other hand, suppose , then , since . Note that . Moreover, if , then ; similarly, if , then . Take A and B in Example 1 for example. One has .

Definition 9.

For any function , we call it a a matched function. We call a matched pair. Every remaining element in is called a mismatched element.

On this basis, we could define the distance for the matched elements and the distance for the mismatched elements as follows:

Definition 10.

For any , define

where and and denote the domain and codomain of φ, respectively. represents the distance of all the matched elements (or the sum of the distances of all the matched pairs), while represents the distance of all the mismatched elements in the range. iff . For example, if and is defined by , then the matched part yields , where denotes the th repetition of i and the mismatched part . Next, we define the set of all minimal distances consisting of the matched parts and the mismatched parts.

Definition 11.

(Minimal matched functions) Define

Definition 12.

(Distance function) Define by

By the definition, one has for any . In the following, we show that is indeed a metric. The reasoning will be proceeded by their relations (i.e., larger, less than and equal to) between cardinalities of , and C, i.e., , and . To validate that is a metric, we need to consider all the 27 relations between and : for example, . In order to facilitate our computing, we encode the 27 relations by the following set

in which each represents the relation and , respectively, where , and 3 represent the relation and > correspondingly. For example, represents the relation , and . By the transitivity of their cardinalities, only 13 of the 27 relations are valid (shown in Lemma 1). Moreover, these 13 relations could be further reduced to 8 relations by the symmetry of , i.e.,

as shown in Corollary 1. If is a bijective function, we use to denote its inverse function. In the following, let , and be arbitrary. Before we proceed further, we have the definitions:

- We use to denote , if and to denote , if .

- We use to denote , if and to denote , if .

- We use to denote , if and to denote , if .

Though there are 27 relations between the cardinalities of , and C, only 13 of them are valid as shown in the following lemma.

Lemma 1.

There are only 13 relations which do not violate the transitivity property in terms of their cardinalities:

Proof.

The result follows immediately from their relations. Take the relation for example. Recall that represents the relation , in which the property of transitivity holds. One could verify that each of the other 12 relations also holds the transitivity property. However, the other 15 relations fail the transitivity property: for example ( i.e., ). ☐

Lemma 2.

(Non-negative, symmetric)

- .

- iff .

- .

Proof.

The first statement follows immediately from the definition and the third one follows from the fact that . Here we show the second one. Suppose , then , where I is the identity function. Suppose . Then, there are two cases: either or . For the former one, one has , i.e., . For the latter one, one has and thus , i.e., . Hence, we have shown iff . ☐

In the following, we show the triangle inequality of . Let us show the following corollary first.

Corollary 1.

To show δ satisfy the triangle inequality, it suffices to consider the following eight relations:

Proof.

By Equation (7) and Lemma 1, A and C are interchangeable, i.e., the relations

are equivalent to (respectively)

☐

By this corollary, we only need to consider the triangle inequality of the above-mentioned eight relations.

Lemma 3.

If , then .

Proof.

Since , it follows

and

Since , by the definition of d, it follows

i.e., . ☐

Lemma 4.

If , then .

Proof.

By the definition , it follows

where denotes . Furthermore,

Henceforth, by the properties of d and the definition of

☐

Lemma 5.

If , then .

Proof.

By the definition , it follows

Henceforth, by the triangle inequality of d

☐

Lemma 6.

If , then .

Proof.

Since

By the triangle inequality of d and the definitions of

☐

Lemma 7.

If , then .

Proof.

By the definitions,

where denotes . Moreover,

Hence, by the triangle inequality of d and the definitions of

☐

Lemma 8.

If , then .

Proof.

By the definitions of

where denotes ;

Furthermore,

Then, by the triangle inequality of d and the definitions of

☐

Lemma 9.

If , then .

Proof.

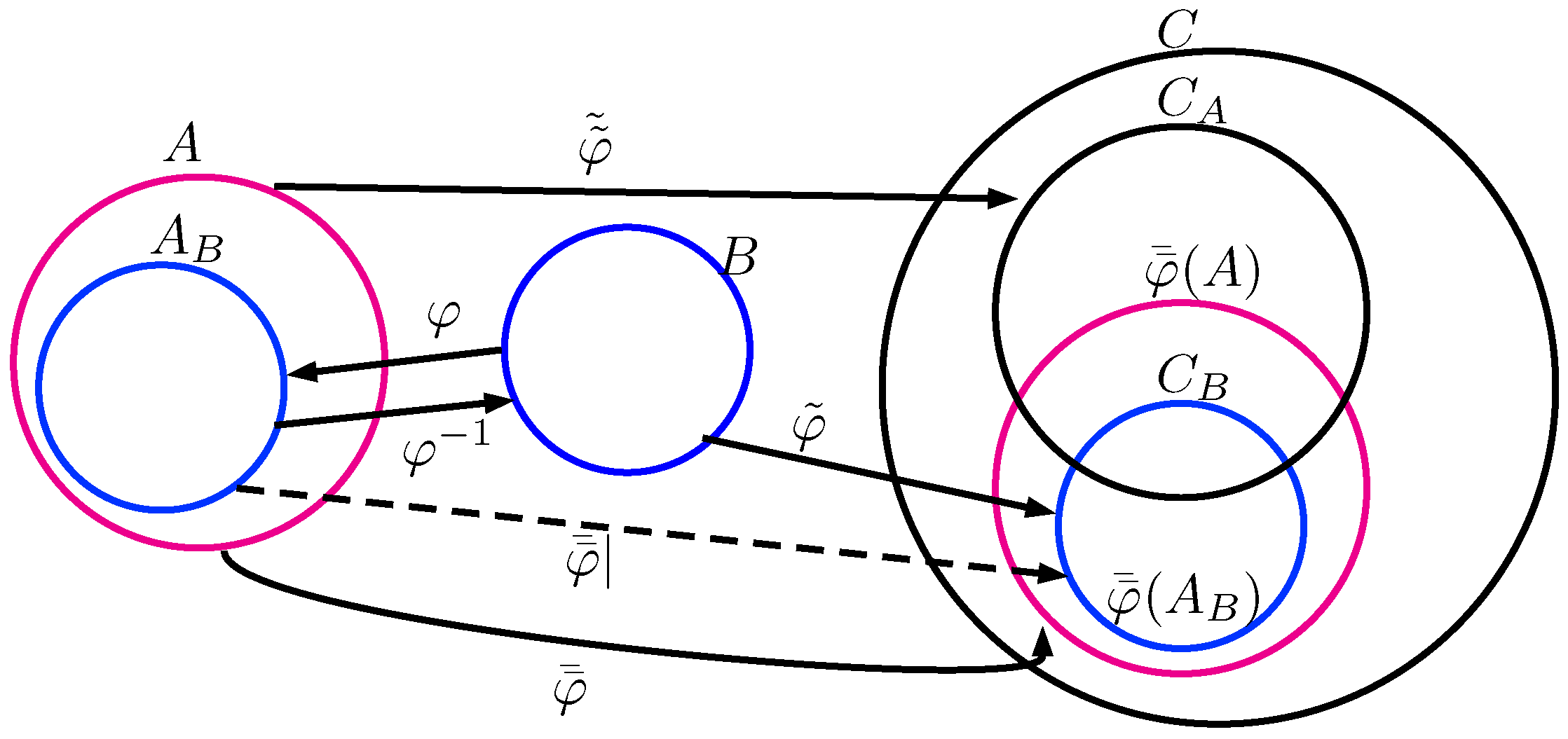

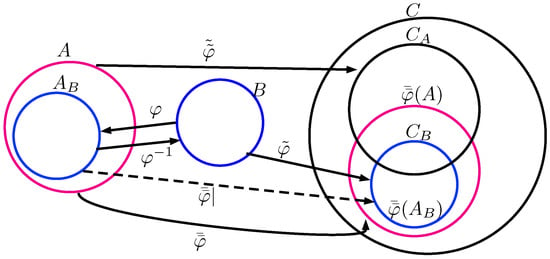

We derive the three components one by one. Firstly, suppose is a function satisfying (as shown in Figure 1), i.e., for all . By the definitions of

Figure 1.

Triangle Inequality for case.

Secondly,

Thirdly,

Hence,

☐

Lemma 10.

If , then .

Proof.

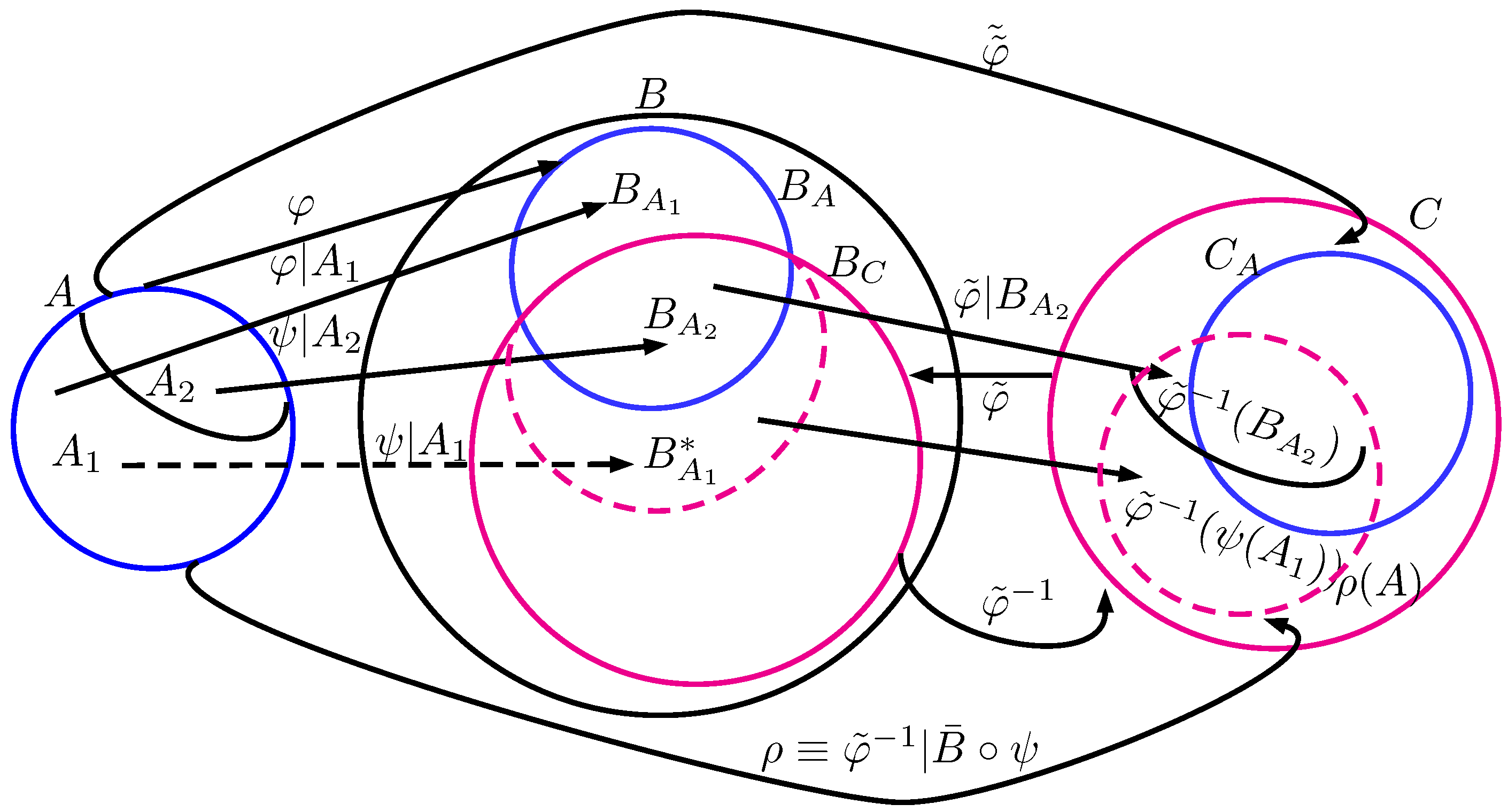

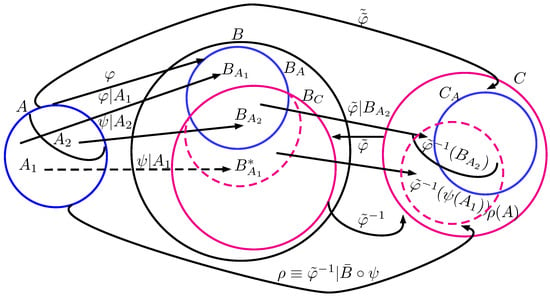

Suppose . Suppose . Suppose Choose a function , in which , i.e., . Suppose , where . Let denote the composition (or simply ). Then, and

as shown in Figure 2. Furthermore, by the definition of ,

Figure 2.

Triangle Inequality for case.

Theorem 1.

is a metric space.

Proof.

By Lemmas 2–10 and Corollary 1, the result follows immediately. ☐

3. Applications and Computations

In this section, we give a group of numerical data and demonstrate how to compute their distances (or adjacency matrix) via the metric . In order to facilitate our computing, we show the following lemmas first. Let be arbitrary.

3.1. Lemmas

Lemma 11.

If and , then .

Proof.

Suppose , suppose , where . Let . Then,

Furthermore, we consider the following cases:

- : Then,

- : Then,

- : Then,Hence, we have shown

☐

Lemma 12.

Let be arbitrary. Let be arbitrary such that . Then, such that for all and .

Proof.

If , then one simply chooses to be . If , then one could choose for all and and . Then, one has . By Lemma 11, one has

which together with yields

i.e.,

i.e., , i.e., . ☐

Corollary 2.

If and with , then , where and for all .

Proof.

By applying Lemma 12 repeatedly, the result follows immediately. ☐

This corollary directly facilitates our computation in the next section. In addition, one could also simplify and redefine the metric by the result of this corollary.

3.2. Computation

In the following, we demonstrate the computation of our metric via a group of simulated data. Suppose

is defined as follows:

- ;

- ;

- ;

- ;

- ;

- .

Suppose the distance function over is defined by

Then, our metric (defined in Equation (6)) derived from this d could be applied. We could then obtain the adjacency matrix of via the following two methods:

- (Method One) List all the permutations and find the optimal permutation and its associated distance, which is the summation of the matched and mismatched parts.

- (Method Two) List all the combinations and find the optimal combination and its associated distance, which is the summation of the matched and mismatched parts.

Method One comes directly from the definition. By Corollary 2, Method Two is also justified. To demonstrate this, let us first compute . If Method One is applied, then one has to compute all the 665,280 permutations, and measure the matched distances between these permutations and and the mismatched distances between these permutations and . If Method Two is applied, then one sorts the set first, and then sorts each of the combinations to measure the matched part between each sorted combination and sorted , and the mismatched part between the sorted combination and . Both methods agree as follows:

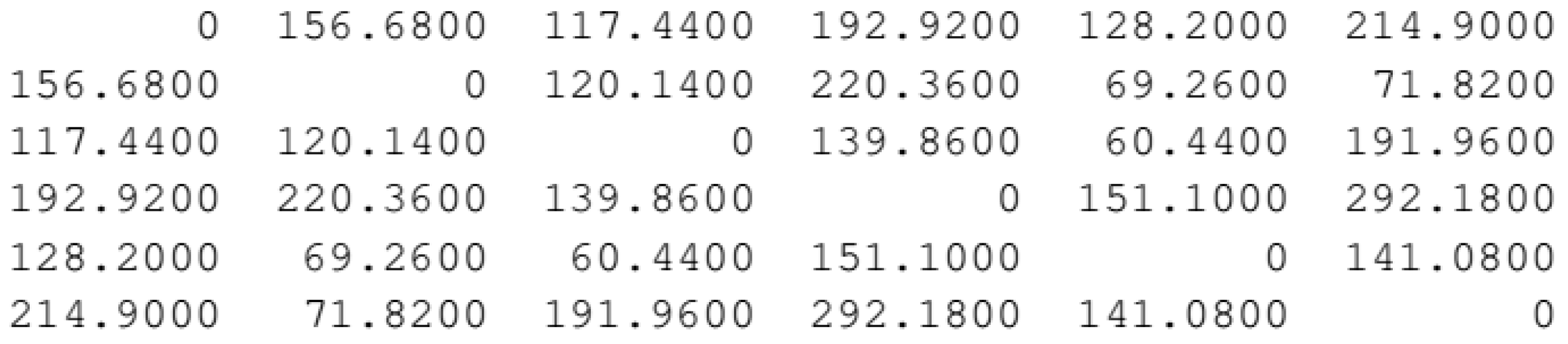

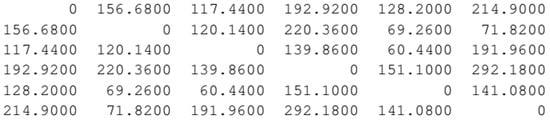

in which the matched distance is and the mismatched distance , where the optimal is defined as follows: . Proceed similarly, the distances for other pairs could also be obtained and the resulting adjacency matrix is demonstrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Adjacency Matrix .

One could verify that this adjacency matrix satisfies all the metric axioms, in particular, for all .

4. Real World Applications

In addition to some trivial applications, one could consider other handy applications, for example, by replacing the usual Euclidean metric with our metric in the following fields: –means, clustering analysis, graph comparisons, etc. (see Reference [2]). These are frequently-used techniques in analyzing data or theoretical computations. The author has also succeeded in defining a novel metric for graphs based on the metric defined in this article. This enables one to measure the distances between any two graphical structures or networks. The idea for the derived metric is to measure the differences between any two graphs by induction on vertexes. Suppose there are two graphs and with the same set of vertices V. For each vertex , one could then generate two multisets whose elements are the lengths between v and its respective set of endpoints in and . Then, he could compute the distances via the minimal sum of matched elements and mismatched elements as defined in this article. This approach yields a new metric for graphs.

4.1. Example

Let us consider a concrete example. Suppose the government in a country is trying to associate a village (among three candidate villages: VL1,VL2,VL3) which produces maize with the wholesalers which sell maize. In VL1, there are five farmers; in VL2, there are six farmers; in VL3, there are 10 farmers. The expected annual yields of maize for each farmer in VL1 are tons; the ones in VL2 are tons; and the ones in VL3 are tons. On the other hand, suppose there are four wholesalers whose annual demands are tons, respectively. The government policy is to associate a village with the wholesalers based on the criterion that the total discrepancy between the village and the wholesalers must be minimal and the condition that each farmer could only exclusively sign the contract with exactly one wholesaler. Assume the government adopts the metric defined in this article. The results could be computed as follows Table 1.

Table 1.

Analysis of Optimal Matchings.

Since the total discrepancy (i.e., matched part plus mismatched part) between VL2 and the wholesalers is minimal (or ), the government should associate VL2 with the wholesalers. Henceforth, the government should pick VL2 to sign the contract with the four wholesalers exclusively. In doing so, the total dissatisfaction (or discrepancy) from both the farmer and the wholesalers would be minimal.

4.2. Characteristic and Analysis

The main characteristic of our metric is that it takes the minimal discrepancy into consideration. For the usual metrics, one hardly associates a metric with the minimal matching via combinations or permutations of all sorts of choices. Our method successfully combines the usual definition of a metric with the concept of an optimal choice. With these two concepts combined, one could pick up an optimal decision purely based on the metric defined in this article. This approach gives one a much more direct decision-making process. In addition, since this metric consists of two parts: the matched and mismatched parts, it would provide one with much more insightful knowledge of the discrepancy between mathematical objects.

5. Conclusions

We have defined a metric on a finite power multiset of positive real numbers via the concept of minimal matchings, in which the distances of any two multisets consist of two parts: the distance of the matched part and the distance of the mismatched part. We also implement this metric by an adjacency matrix. A concrete example is also included in this article. In addition to the adjacency matrix, we show another definitional computation to facilitate our computing of the metric. The metric defined in this article could be further applied in some real problems regarding artificial intelligence, clustering, or some other theoretical mathematical research.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (Grant No. 2017J01566).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Blizard, W.D. Multiset Theory. Notre Dame J. Form. Log. 1988, 30, 36–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Yohanna, T.; Singh, J.N. An overview of the applications of multisets. Novi Sad J. Math. 2007, 37, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mémoli, F. Gromov–Wasserstein distances and the metric approach to object matching. Found. Comput. Math. 2011, 11, 417–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, A.; Ram, M.M. Graph Theory; Springer: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, E.K.P.; Zak, S.H. An Introduction to Optimization; Jonh Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karapınar, E.; Yıldız-Ulus, A.; Erhan, İ.M. Cyclic Contractions on G-Metric Spaces. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012, 2012, 182947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, A. Mathematics of Multisets; Multiset Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Blizard, W.D. Real-valued multisets and fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1989, 33, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).