1. Introduction

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, James Clerk Maxwell in 1860 and Ludwig Boltzmann in 1871 formulated the probability law governing the distribution of molecular speeds in a gas at a given temperature. This formulation, now known as the Maxwell–Boltzmann (MB(

)) distribution, constitutes a fundamental statistical model in classical kinetic theory, describing the distribution of molecular speeds in an ideal gas at thermal equilibrium. Recently, the MB law underpins key thermodynamic relations, such as pressure, diffusion, and thermal transport. Owing to these properties, the distribution finds extensive applications across physics, chemistry, and statistical mechanics, as well as in emerging domains such as engineering reliability analysis, where it serves as a flexible model for lifetime and degradation data (see Rowlinson [

1] for details).

Let

Y be a non-negative continuous random variable representing a lifetime. If

, where

denotes a scale parameter, then the probability density function (PDF;

) and cumulative distribution function (CDF;

) of

Y are given, respectively, by

and

where

denote the gamma and incomplete-gamma functions, respectively.

Function (

2) admits the following equivalent form:

where

Moreover, we investigated two unknown time metrics—namely the reliability function (RF;

) and hazard rate function (HRF;

) of the MB(

) distribution—at distinct time

, which are given, respectively, by

and

Taking several configurations of

,

Figure 1 indicates that the MB’s PDF (

1) behaves like a right-skewed or unimodal density shape, while the MB’s HRF (

5) is strictly increasing for

.

Over roughly the last decade, the MB model has evolved into a well-established tool in reliability research, attracting wide-ranging investigations under diverse censoring and sampling schemes. For example, Krishna and Malik [

2,

3] analyzed the model under conventional Type-II censoring (T2-C) and Type-II progressive censoring (T2-PC), respectively. Tomer and Panwar [

4] considered its application in a Type-I hybrid progressive censoring (T1-HPC), while Chaudhary and Tomer [

5] examined stress–strength reliability settings with T2-PC data. Pathak et al. [

6] studied the distribution in the context of the T2-PC plan incorporating binomial removals under step-stress partially accelerated life testing. More recently, Elshahhat et al. [

7] discussed the MB reliability metrics using samples created from a generalized T2-HPC strategy. These studies, among others, illustrate the model’s adaptability to a variety of experimental designs and reinforce its value as a versatile lifetime distribution for modern engineering reliability analysis.

The T2-PC has become a well-established tool in both reliability engineering and survival analysis, primarily because it offers greater operational flexibility than the T2-C framework. A key advantage of T2-PC is its capacity to progressively withdraw the functioning units that were investigated during the experimental design, which is particularly valuable in large-scale industrial testing or long-term clinical investigations. In a standard T2-PC arrangement,

m failures are targeted from

n identical experimental units, with a predetermined censoring plan

fixed prior to commencement. Following the first observed failure

, a randomly chosen set of

surviving units is removed from the remaining

items. Upon the second failure

, a further

units are withdrawn from the updated risk set of

items, and this process then continues. Once the

mth failure occurs, all remaining

survivors are censored, marking the end of the experiment [

8].

Within the broader class of hybrid censoring schemes, Kundu and Joarder [

9] introduced the T1-HPC plan. In this setting,

n test units are placed under a progressive censoring scheme

, and the termination time is defined as

, where

t is a fixed inspection time. While this approach limits the maximum test duration, it can lead to a small number of observed failures, thereby reducing the precision of statistical inference. To address this drawback, Ng et al. [

10] developed the adaptive Type-II progressive censoring (AT2-PC) strategy, where the number of failures

m is fixed in advance but the censoring vector

can be adaptively modified during the experiment. The AT2-PC retains the sequential removal structure of T2-PC while improving estimation efficiency.

However, for test items with exceptionally long lifetimes, the AT2-PC framework may still lead to excessively prolonged experiments. To mitigate this, Yan et al. [

11] recently proposed the improved AT2-PC (IAT2-PC) model. This generalization of both T1-HPC and AT2-PC incorporates two finite time thresholds—

and

, where

—to control the total test duration. Under IAT2-PC,

m failures are planned from

n starting units, with removals specified by

. After each failure

, a designated number

of surviving units is randomly withdrawn from the remaining set. The numbers of observed failures by times

and

are recorded as

and

, respectively, providing additional structure to the stopping rules while ensuring sufficient data for analysis.

Subsequently, the observed data collected by the practitioner will be one of the following censoring fashions:

Case-1: As , stop the test at .

Case-2: As , reset as , stop the test at .

Case-3: As , reset as , stop the test at .

Let

denote a sample of size

, which is obtained under an IAT2-PC from a continuous population characterized by PDF

and CDF

. The joint likelihood function (LF) for this sample can be expressed as

where

for simplicity. To distinguish,

Table 1 summarizes the math operators defined in the LF (

6). For further clarification, a flowchart of the IAT2-PC plan is designed in

Figure 2.

For clarity, we provide a simple example to illustrate the choices of

,

, and

in practice. Suppose

is a T2-PC sample with

, obtained using

from a continuous lifetime population with

. Consequently, the practitioner records one scenario for the three cases of the IAT2-PC plan based on several choices of

and

, as summarized in

Table 2.

It should be noted here that the IAT2-PC design can be considered an extension for several common censoring schemes, including the following:

When

and

, then the T1-HPC scheme by Kundu and Joarder [

9] applies;

When

, then the AT2-PC scheme by Ng et al. [

10] applies;

When

, then the T2-PC scheme by Balakrishnan and Cramer [

8] applies;

When

,

for

, and

, then the T2-C scheme by Bain and Engelhardt [

12] applies.

Remark 1. The IAT2-PC scheme can be considered an extension of the T1-HPC, AT2-PC, T2-PC, and T2-C schemes.

In the IAT2-PC mechanism, the first threshold

functions as an early warning for the elapsed experimental time, signaling that the study has reached a predefined interim stage. In contrast, the second threshold

defines the absolute maximum duration for the experiment. Should

be attained before the occurrence of the predetermined number of failures

m, the study is forcibly terminated at time

. This refinement directly addresses the limitation of the AT2-PC design (by Ng et al. [

10]), where no explicit upper bound on total test duration was guaranteed. By imposing the constraint

, the improved censoring scheme ensures that the experiment cannot exceed the designated maximum time, thereby enhancing its practical applicability. In the reliability literature, using likelihood-based (

6) inference, analogous approaches have been applied to various lifetime distributions, including Weibull [

13], Burr Type-III [

14], Nadarajah-Haghighi [

15], power half-normal [

16], and inverted XLindley [

17] models.

In reliability theory and lifetime analysis, the development of efficient statistical models under complex censoring schemes has become increasingly important for modern engineering applications. Classical censoring methods often fail to balance experimental cost, information retention, and statistical precision, particularly when dealing with large-scale life tests in engineering systems. The MB distribution, though originally arising in statistical physics, has recently attracted attention in reliability modeling due to its flexibility in characterizing diverse failure mechanisms with monotonic hazard structures. However, its potential remains underexplored in censored reliability contexts. On the other hand, the IAT2-PC scheme has emerged as a promising design for life-testing experiments, allowing dynamic adjustments in the number of units removed during the test, thereby enhancing efficiency while maintaining the robustness of parameter inference. Motivated by these considerations, this study aims to integrate the MB model with an IAT2-PC plan, thereby providing a more powerful and cost-effective approach to engineering failure modeling and statistical inference. However, the objectives of this study can be summarized in six outlines:

This study is the first to investigate the MB distribution under the IAT2-PC scheme, extending its scope in reliability analysis.

Likelihood-based inference is developed for model parameters under IAT2-PC, and the existence and uniqueness of the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) of MB() is established with numerical evidence.

Bayesian estimation methods are proposed using an inverted-gamma prior and Markov chain Monte Carlo techniques, with derivations of posterior summaries and Bayes credible intervals (BCIs).

Several interval estimation strategies were compared, including asymptotic (normal and log-normal) intervals and Bayesian (BCI and HPD) intervals, to provide robust inference tools.

A comprehensive Monte Carlo simulation study evaluating the precision and efficiency of the proposed estimators under various censoring designs was conducted, demonstrating the advantages of the Bayesian framework.

Two real engineering datasets were analyzed, confirming the practical applicability of the proposed modeling framework in real-world reliability experiments.

The structure of the rest of this study is organized as follows.

Section 2 and

Section 3 present the frequentist and Bayesian estimation methodologies, respectively.

Section 5 provides Monte Carlo simulation results. Two genuine engineering applications are analyzed in

Section 6. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes the main conclusions and key insights derived from this work.

2. Likelihood Inference

This section is devoted to the ML estimation of the MB model parameters, namely

,

, and

. Under the assumption of approximate normality for the corresponding estimators,

ACI estimators were obtained by employing the observed Fisher information (FI) matrix in combination with the delta approach. Utilizing the expressions in (

1), (

2), and (

6), Equation (

6) can be equivalently written as follows:

Equivalently, the log-LF of (

7) becomes

Thereafter, the MLE of

, represented by

, is determined by maximizing (

8), resulting in the following nonlinear expression:

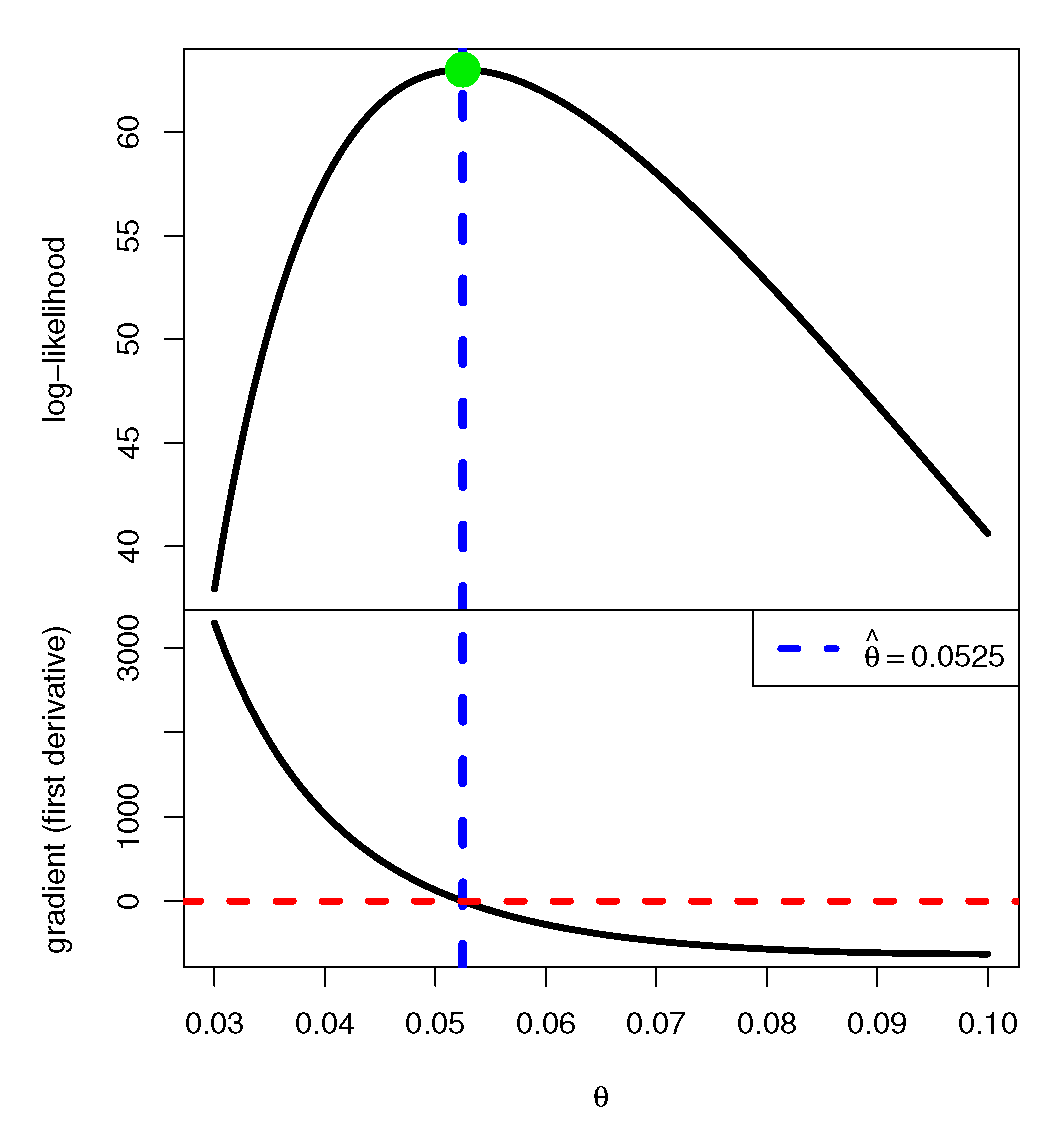

Remark 2. The MLE of θ, based on the log-LF in (8), exists and is unique for . From Equation (

9), it is clear that the MLE

of

does not admit a closed-form solution. Consequently, it becomes important to assess both the existence and uniqueness of

. Given the complexity of the score function in (

9), an analytical verification is challenging. To overcome this, we investigated these properties numerically by generating an IAT2-PC sample from the MB distribution with parameters

under the configuration

,

,

, and a uniform T2-PC scheme with

for

. The resulting MLE values of

were 0.4833 and 2.4643 for the two respective cases.

Figure 3 depicts the log-LF (

8) alongside the score function from (

9) as functions of

over a selected range. As shown, the vertical lines corresponding to the MLE intersect the log-likelihood curve at its maximum and cross the score function at zero. These findings confirm that the MLE of

exists and is unique for each considered scenario.

Although providing an analytical proof of concavity is challenging due to the nonlinear structure of the likelihood, the uniqueness of the MLE can be justified under general conditions requiring the observed information matrix to be positive definite. Our numerical experiments, including eigenvalue analyses from different initial values, consistently confirm concavity in practice and thus offer strong evidence for uniqueness (see

Figure 3).

After obtaining

, the MLEs of the RF and HRF—denoted by

and

, respectively—can be readily determined from Equations (

4) and (

5) for

as follows:

and

respectively. The Newton–Raphson (NR) algorithm, implemented through the

maxLik package (by Henningsen and Toomet [

18]) in the R programming environment, was employed to efficiently compute the fitted estimates

,

, and

.

3. Bayesian Inference

This section is devoted to deriving both point and credible Bayesian estimates for

,

, and

. Within the Bayesian framework, the specification of prior distributions and loss functions is fundamental. As highlighted by Bekker and Roux [

19] and Elshahhat et al. [

7], selecting an appropriate prior is often nontrivial with no universally accepted guideline. Considering that the MB parameter

is strictly positive, the inverted-gamma

distribution offers a natural and versatile prior choice. Accordingly, we assume

, where

denote the hyperparameters. The Inv.G distribution (

10) is a flexible prior for positive parameters, with heavier tails than the gamma and less mass near zero. Its shape varies with parameter values, and it yields simple posterior forms. Other conjugate priors, such as gamma, normal-inverse-gamma, and inverse-gamma-gamma, can also be considered.

To evaluate the sensitivity of the results to prior selection, we additionally considered a conjugate gamma prior. The posterior summaries derived under this alternative prior were nearly indistinguishable from those obtained with the proposed Inv.G prior, indicating that the Bayesian inference is robust to reasonable variations in prior specification.

Then, the prior PDF, denoted by

, is given by

where

denotes the gamma function, and

and

are known. From (

7) and (

10), the posterior PDF (say

) of

is

where its normalized term (say,

) is given by

We then adopted the squared-error loss (SEL) function as the primary loss criterion, owing to its widespread use and symmetric nature in Bayesian analysis. Nevertheless, the proposed approach can be readily extended to alternative loss functions. Levering the SEL, the Bayesian estimated (say

) of

is acquired by the posterior-mean as follows:

Given the posterior distribution in (

11) and the nonlinear form of the LF in (

7), the Bayes estimates of

,

, and

under SEL are analytically intractable. Therefore, we employed the MCMC method to generate Markovian samples from (

11), which were subsequently used to compute the Bayesian estimates and construct the corresponding BCI/HPD intervals for each parameter. Although the posterior density of

in (

11) does not correspond to any standard continuous distribution, using the same censoring setting provided in plotting

Figure 3,

Figure 4 indicates that its conditional form closely approximates a normal distribution. Consequently, following Algorithm 1, the Metropolis–Hastings (M–H) algorithm is applied to update the posterior samples of

, after which the Bayes estimates for

,

, and

are obtained.

| Algorithm 1 The M-H Algorithm for Sampling , , and |

- 1:

Input: Initial estimate , estimated variance , total iterations , burn-in , confidence level - 2:

Output: Posterior mean - 3:

Set - 4:

Set - 5:

whiledo - 6:

Generate - 7:

Compute acceptance ratio: - 8:

Generate - 9:

if then - 10:

Set - 11:

else - 12:

Set - 13:

end if - 14:

Update and using in ( 4) and ( 5) - 15:

Increment - 16:

end while - 17:

Discard the first samples as burn-in - 18:

Define - 19:

|

5. Monte Carlo Comparisons

To assess the accuracy and practical utility of the estimators for , , and derived in the preceding sections, we conducted a series of Monte Carlo simulation experiments. Following the steps outlined in Algorithm 3, the IAT2-PC procedure was executed 1000 times for each chosen value of the shape parameter (specifically, and ), enabling the computation of both point estimates and interval estimates for the parameters of interest. For a fixed , the corresponding reliability and hazard function estimates, , are obtained as for and for . The simulations are carried out under multiple configurations defined by combinations of threshold parameters , total sample sizes n, effective sample sizes m, and censoring schemes . In particular, we considered , , and .

Table 3 lists, for each value of

n, the selected values of

m along with the corresponding T2–PC schemes

. For brevity, a notation such as ‘A1[1]

(

,

)’ indicates that five units are removed at each stage for the first four censoring stages. After this, the practitioner stopped the removal process for the remaining stages.

| Algorithm 3 Simulate IAT2-PC Dataset from MB Lifespan Population. |

- 1:

Input: Set values for n, m, , and - 2:

Set the true value of MB() parameter. - 3:

Generate m independent uniform random variables - 4:

for to m do - 5:

Compute - 6:

end for - 7:

for to m do - 8:

Compute - 9:

end for - 10:

for to m do - 11:

Compute - 12:

end for - 13:

Observe failures at time - 14:

Remove observations - 15:

Set truncated sample size: - 16:

Generate order statistics from truncated distribution: - 16:

PDF: - 17:

if

then - 18:

Case 1: End test at - 19:

else if

then - 20:

Case 2: End test at - 21:

else if

then - 22:

Case 3: End test at - 23:

end if

|

To further examine the sensitivity of the proposed estimation procedures within the Bayesian framework, we investigated two distinct sets of hyperparameters for each MB distribution. Adopting the prior elicitation approach outlined by Kundu [

22], the hyperparameters

and

in the Inv.G prior PDF are specified. Then, we adopted two prior groups (PGs) for

for each value of MB(

) as follows:

At : PG-1:(2.5,6) and PG-2:(5,11);

At : PG-1:(7.5,6) and PG-2:(15,11).

Bayesian inference always depends on the choice of prior beliefs. A sensitivity analysis checks how much the results change when different reasonable priors are used. This is especially important when prior knowledge is uncertain, partly subjective, or when guidelines require that results be shown to be reliable. To test the strength and trustworthiness of the findings, the sensitivity analysis was performed with four kinds of priors: informative (using PG-2 as a representative case), noninformative (when

), weakly informative (when

), and overdispersed (when

).

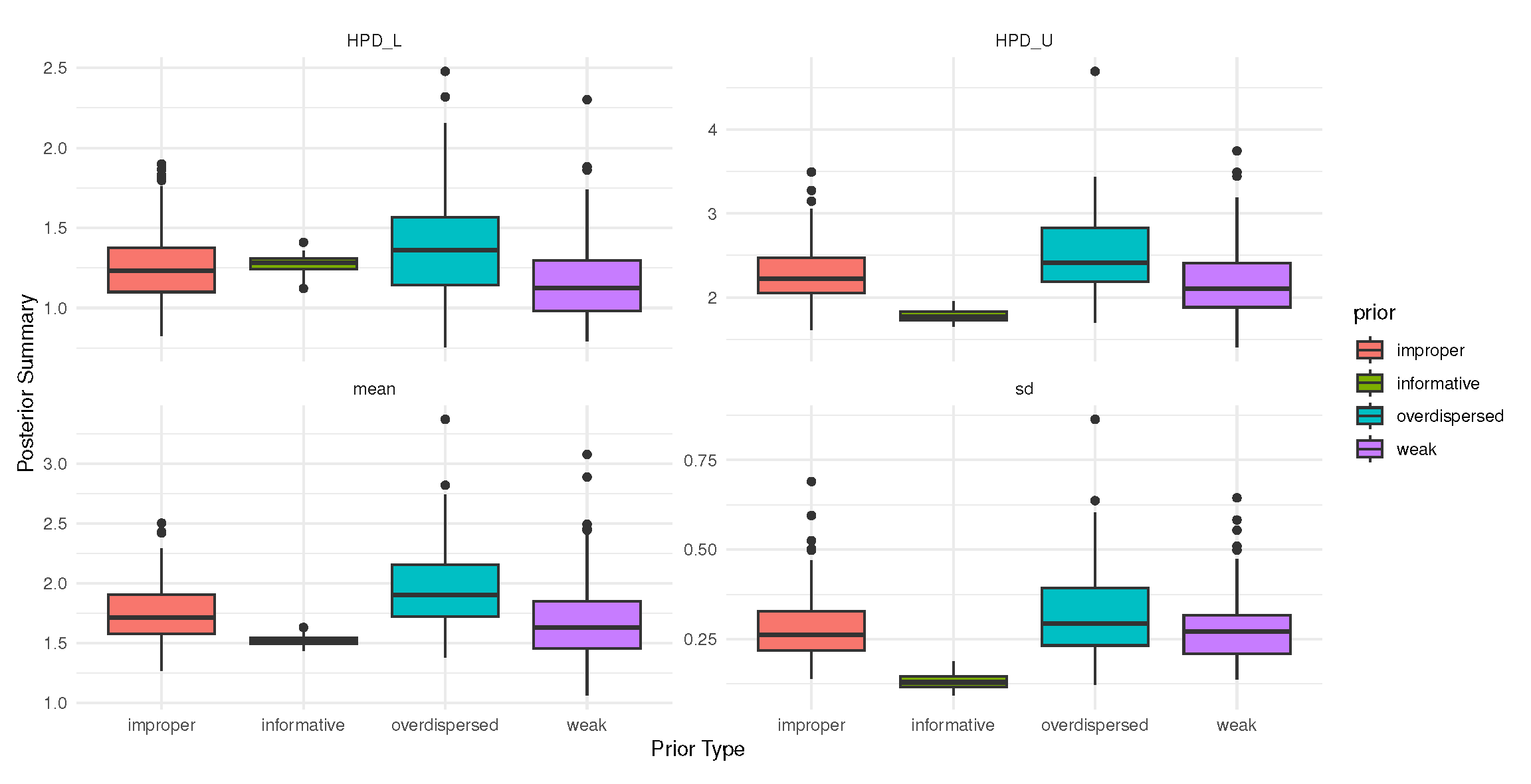

Figure 5 illustrates the sensitivity of posterior estimates for

to four predefined prior types. It shows that posterior means are robust across different prior choices, while posterior uncertainty (credible interval width and standard deviation) is highly sensitive to prior informativeness. Informative priors yield the most concentrated posterior distributions, whereas improper and overdispersed priors produce wider spreads, reflecting higher uncertainty. For further details on the sensitivity analysis of posterior estimates under two (or more) different prior choices, see Alotaibi et al. [

23].

Once 1000 IAT2-PC datasets were generated, the frequentist estimates and their corresponding 95% ACI[NA] and ACI[NL] estimates for

,

, and

were computed using the

maxLik package (Henningsen and Toomet [

18]) in the R software environment (version 4.2.2).

For the Bayesian analysis, 12,000 MCMC samples were drawn, with the first 2000 iterations discarded as burn-in. The resulting Bayesian estimates, along with their 95% BCI and HPD interval estimates for

,

, and

, were computed using the coda package (Plummer et al. [

24]) within the same R environment. For the Bayesian implementation, we employed the M–H algorithm with Gaussian proposal distributions centered at the current state. The proposal variances were tuned in preliminary runs to maintain acceptance rates between 0.80 and 0.95, ensuring good mixing properties. All parameters were restricted to the positive domain, consistent with the support of the MB distribution. Across all simulation settings, the monitored acceptance rates confirmed the stable performance of the chains.

Then, to evaluate the offered estimators obtained for the MB() parameter, we calculated the following metrics:

Mean Point Estimate:

Root Mean Squared Error:

Mean Relative Absolute Bias:

Average Interval Length:

Coverage Percentage:

where denotes the estimate of obtained from the ith sample, represents the indicator function, and denotes the two-sided asymptotic (or credible) interval for . The same precision measures can analogously be applied to and .

In

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6, the point estimation results—including mean point estimates (MPEs; 1st column), root mean squared errors (RMSEs; 2nd column), and mean relative absolute biases (ARABs; 3rd column)—for

,

, and

are reported. Correspondingly,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 present the average interval lengths (AILs; 1st column) and coverage probabilities (CPs; 2nd column) for the same parameters. In the

Supplementary File, the simulation results associated with

,

, and

when

are provided. The key findings, emphasizing configurations with the lowest RMSEs, ARABs, and AILs alongside the highest CPs, are summarized as follows:

Across all configurations, the estimation results for , , and exhibited satisfactory performance.

Increasing the total sample size n (or the effective sample size m) leads to improved estimation accuracy for all parameters. A comparable improvement was observed when the total number of removals, , was reduced.

Higher threshold values () enhance estimation precision, as evidenced by reductions in RMSEs, ARABs, and AILs, along with corresponding increases in CPs.

When the value of increases, the following apply:

- –

Both the RMSEs and ARABs of and tend to increase while those of tend to decrease;

- –

The AILs of tend to increase while those of and tend to decrease;

- –

The CPs of increase while those of and decrease.

The Bayesian estimators obtained via MCMC, together with their credible intervals, demonstrated greater robustness compared to frequentist estimators, primarily due to the incorporation of informative Inv.G priors.

For all considered values of , the Bayesian estimator under PG-2 consistently outperformed other approaches. This superiority is attributable to the lower prior variance of PG-2 relative to PG-1. A similar advantage was observed when comparing credible intervals (BCI and HPD) to asymptotic intervals (ACI[NA] and ACI[NL]).

A comparative assessment of the T2–PC designs listed in

Table 3 revealed the following:

- –

For and , configurations C ( and ) yielded the most accurate point and interval estimates;

- –

For , configurations A ( and ) provided the highest estimation accuracy.

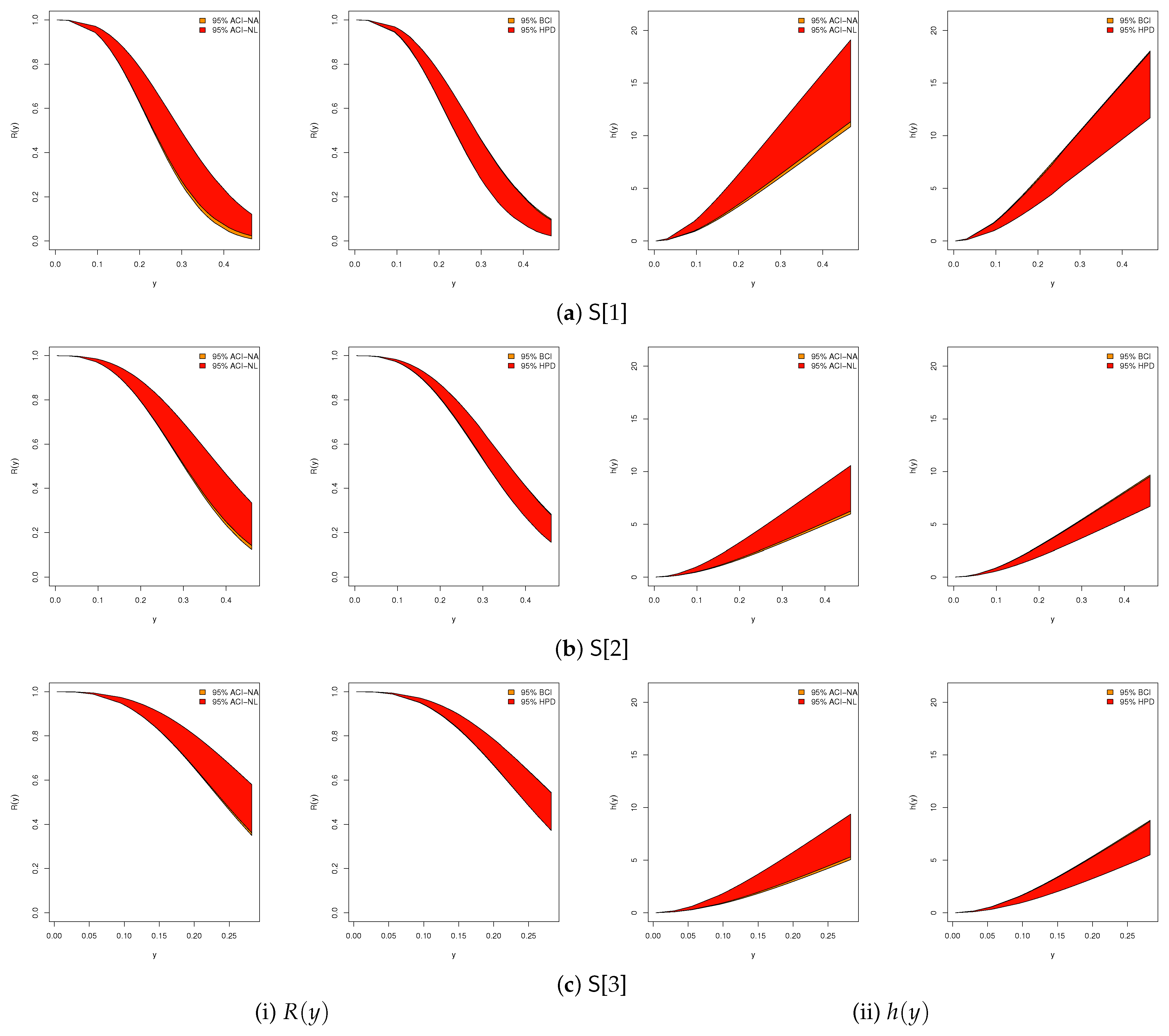

Regarding interval estimation methods, the following apply:

- –

The ACI[NA] method outperforms ACI[NL] for estimating and , while the ACI[NL] method performs better for ;

- –

The HPD method yields superior interval estimates for all parameters compared to BCI;

- –

Overall, Bayesian interval estimators (BCI or HPD) surpass asymptotic interval estimators (ACI[NA] or ACI[NL]) in performance.

In conclusion, for analyzing the Maxwell–Boltzmann lifetimes under the proposed sampling strategy, the Bayesian framework implemented via the MCMC methodology—particularly using the M–H algorithm with Inv.G prior knowledge—is recommended as the most effective approach.