A Flexible Bivariate Lifetime Model with Upper Bound: Theoretical Development and Lifetime Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Definitions and Properties

2.1. The Bivariate T-Y Family

2.2. Construction of a Bivariate Bounded Model Using Log-Logistic and Gompertz Distributions

- the Gompertz distribution’s capacity to model monotone exponential-like growth or decay; and

- the log-logistic distribution’s flexibility in generating unimodal or bathtub-shaped hazard rate functions.

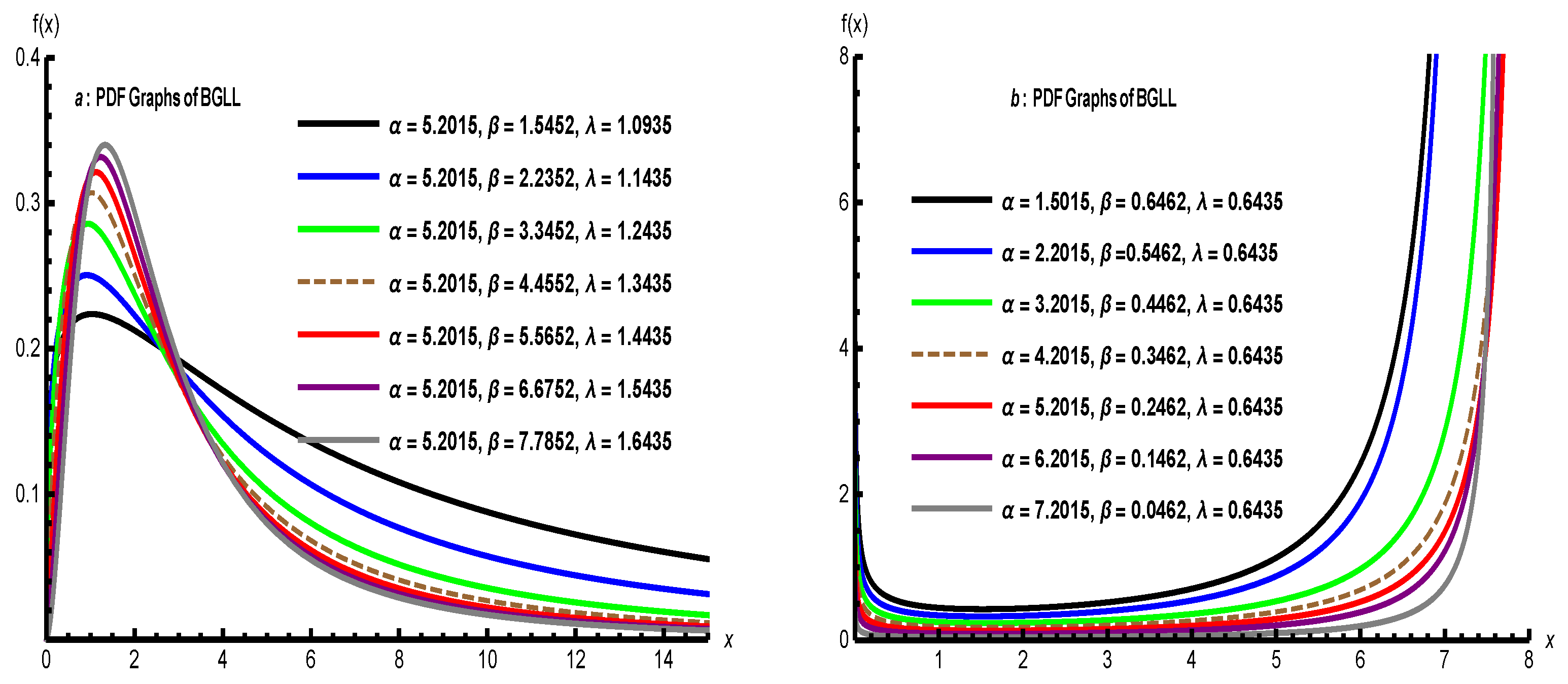

The Upper BGLL Distribution

- As ,

- As ,

- It decreases when (maximum at ).

- It increases when (maximum at ).

- as : ;

- as : .

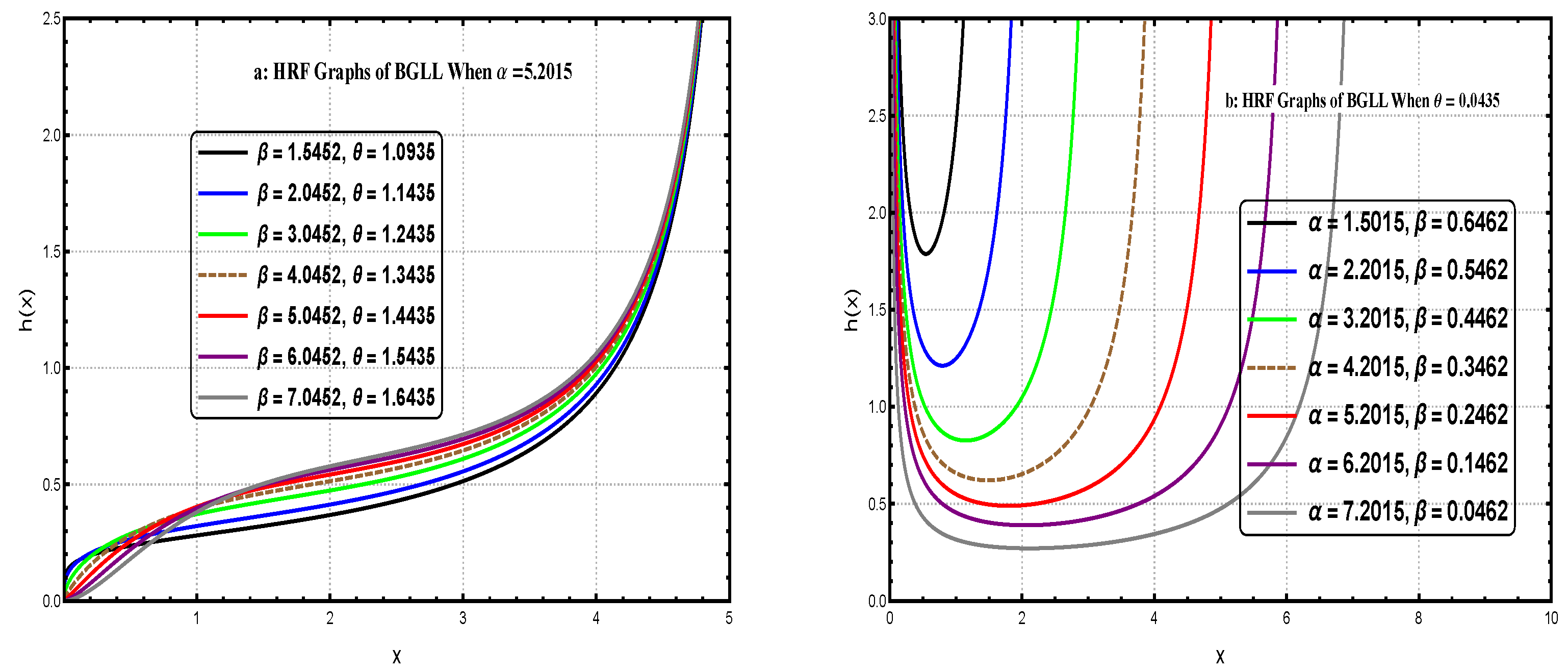

- For and : HRF is initially increasing (IFR property) and may have a maximum point (unimodal).

- For and : HRF is bathtub (BTS property).

- For : h() = is strictly increasing.

- When : when :

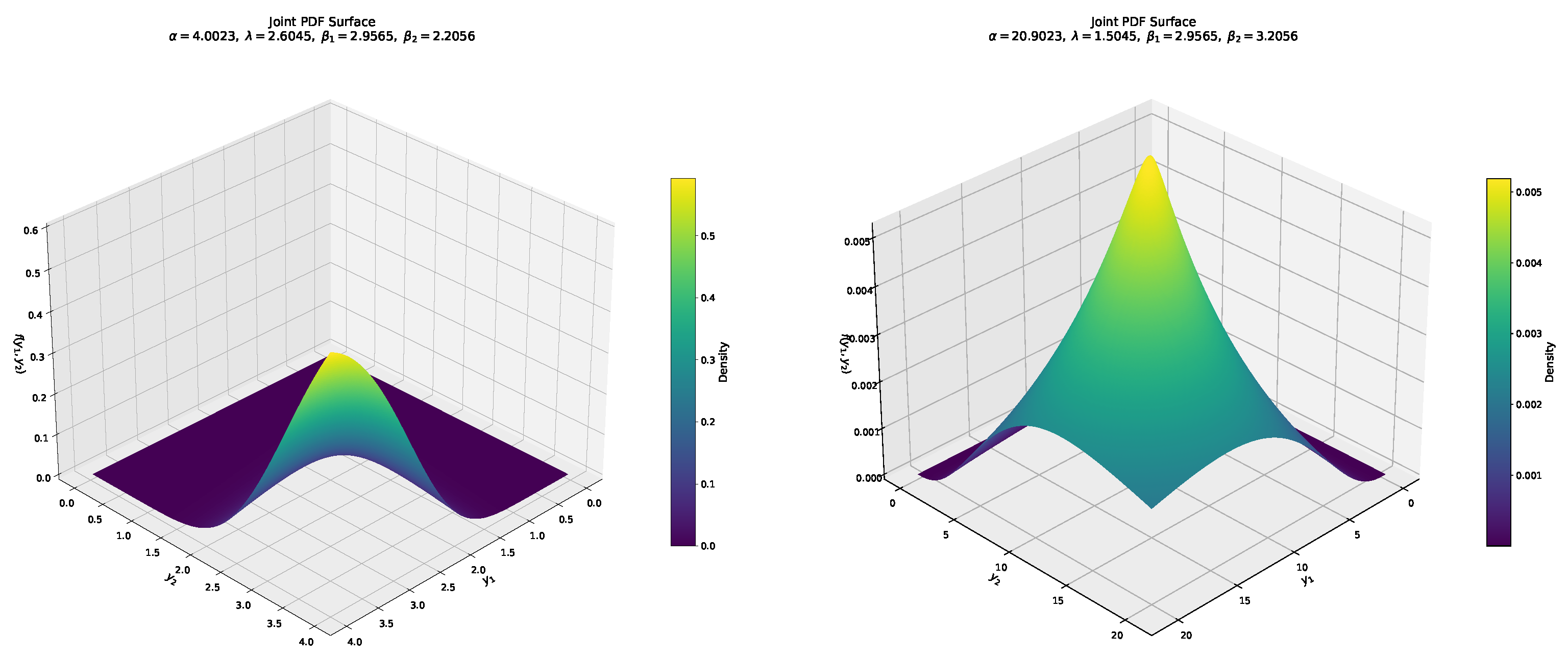

2.3. Bivariate Bounded Gompertz Log-Logistic Distribution

3. Bivariate Bounded Gompertz–Log-Logistic Distribution with Clayton Copula

3.1. The BBGLL Construction with Clayton Copula

3.1.1. Dependence Measures

- (1)

- Kendall’s τ and Spearman’s ρ:

- (2)

- As , (independence); as , (perfect positive dependence).

3.1.2. Tail Dependence and Tail Orders

- Upper-tail dependence, i.e., (asymptotic independence).

- Lower-tail dependence, i.e., .

- Upper-tail order, i.e., (intermediate tail dependence).

- Lower-tail order, i.e., (strictly faster than any power-law decay).

3.1.3. Positive Quadrant Dependence

3.1.4. Survival Function

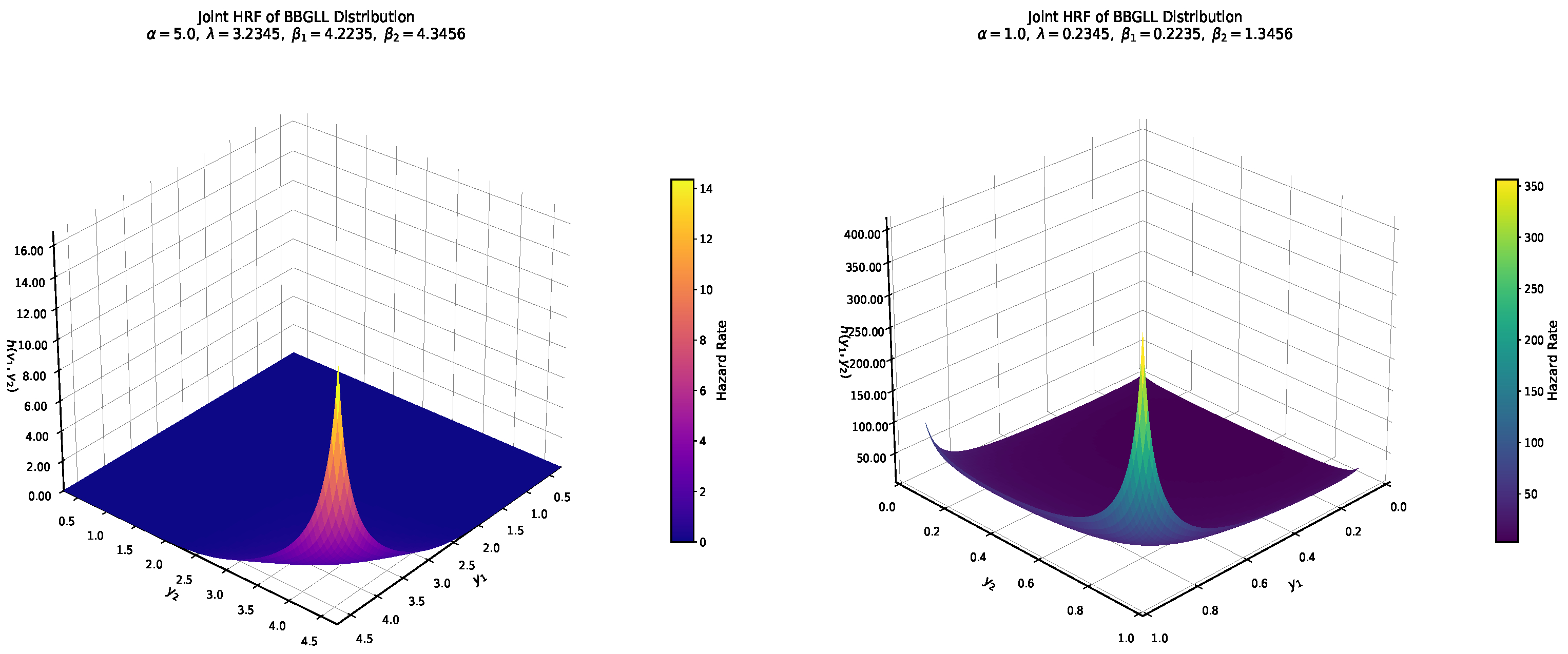

3.1.5. Hazard Rate Function

3.1.6. Conditional Densities

- Generate .

- Compute

- Compute the BGLL marginal values

- Return .

3.2. Main Properties

Moment Properties

3.3. Estimation Methods

3.3.1. Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

- Simulate pairs from a Clayton copula using the conditional distribution method.

- Transform to using the inverse marginal CDFs.

- Estimate MLEs for each sample.

- Compute averages, biases, and MSEs across replicates.

- Generate plots for bias and MSE.

3.3.2. Inference Functions for Margins (IFM) Estimation

3.3.3. Semi-Parametric Estimation Procedure

3.3.4. Simulation Metrics

3.3.5. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals

4. Real-Life Data Application

- Bounded support: many lifetime phenomena, such as biological growth or mechanical degradation, evolve within natural or technological limits.

- Asymmetric marginal shapes: the Gompertz–log-logistic mixture captures early acceleration and late deceleration of failure intensity.

- Implicit dependence through the shared rate parameter (): this allows for interpretable correlation between components.

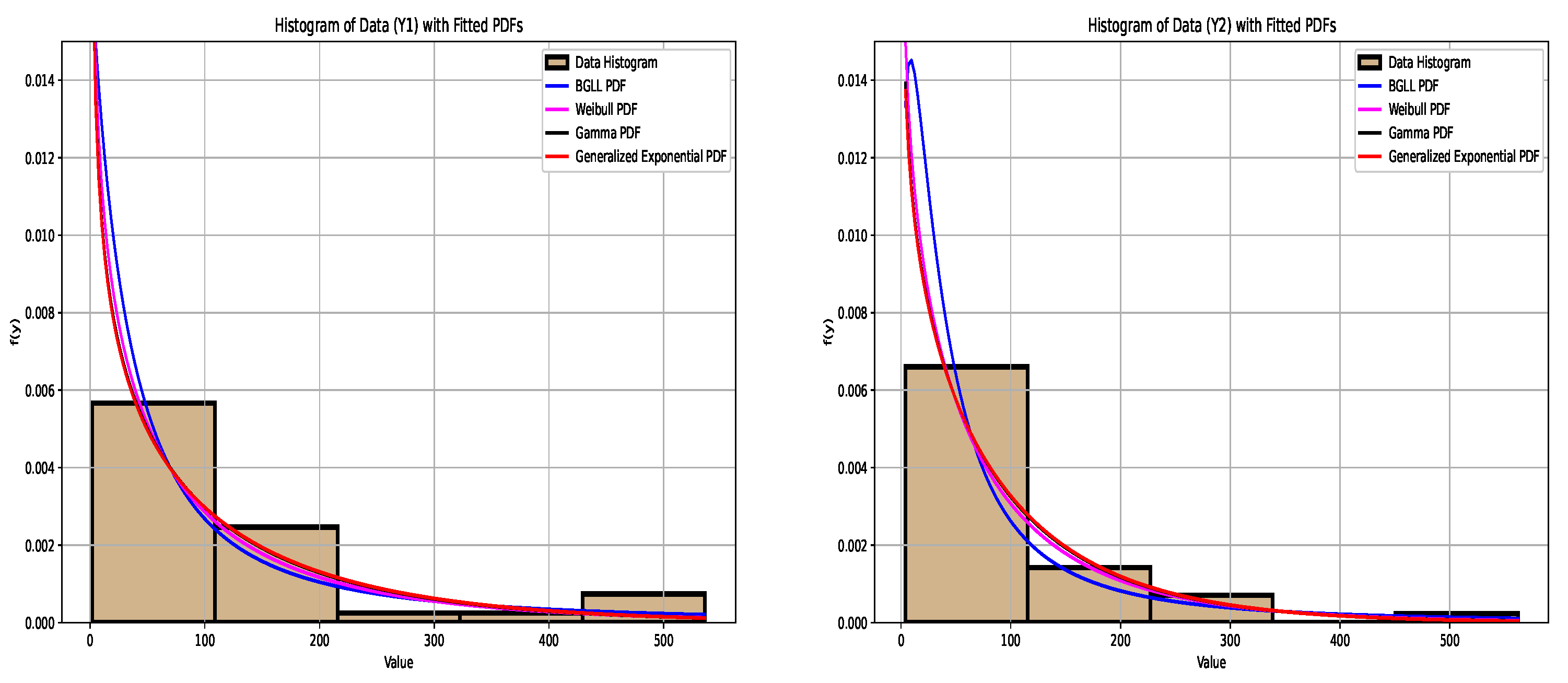

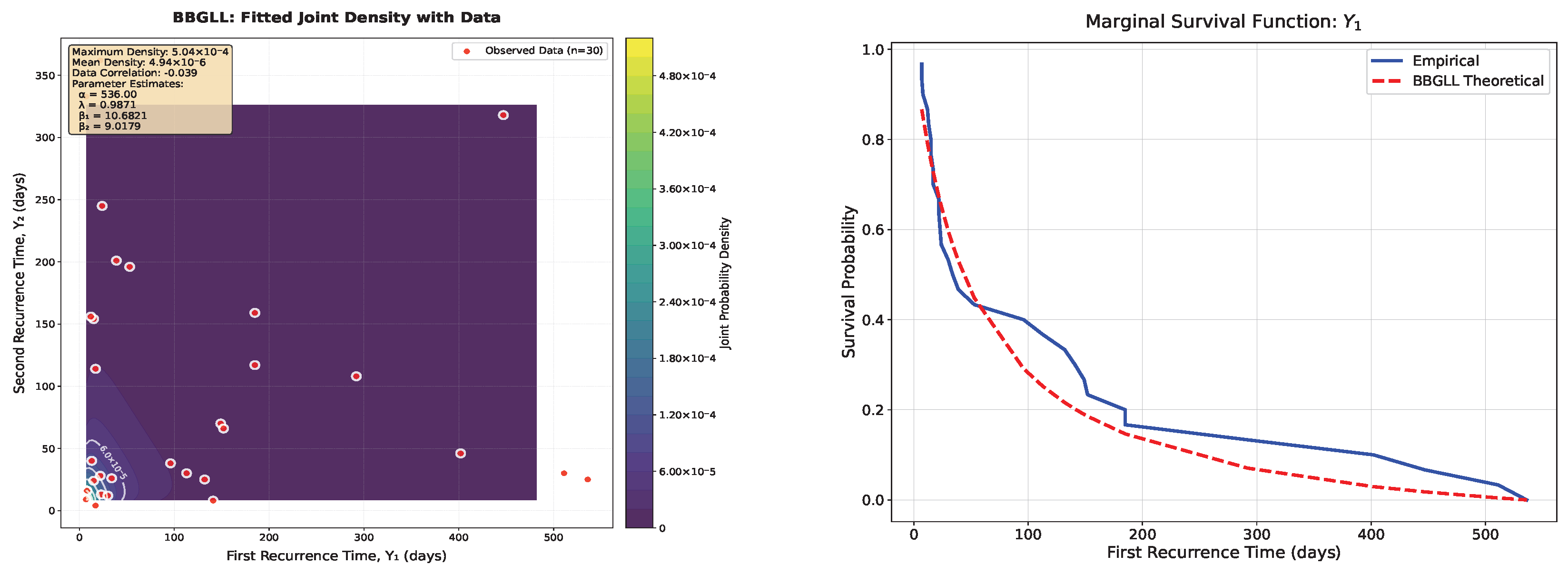

4.1. Interpretation of Marginal BGLL and Data Analysis

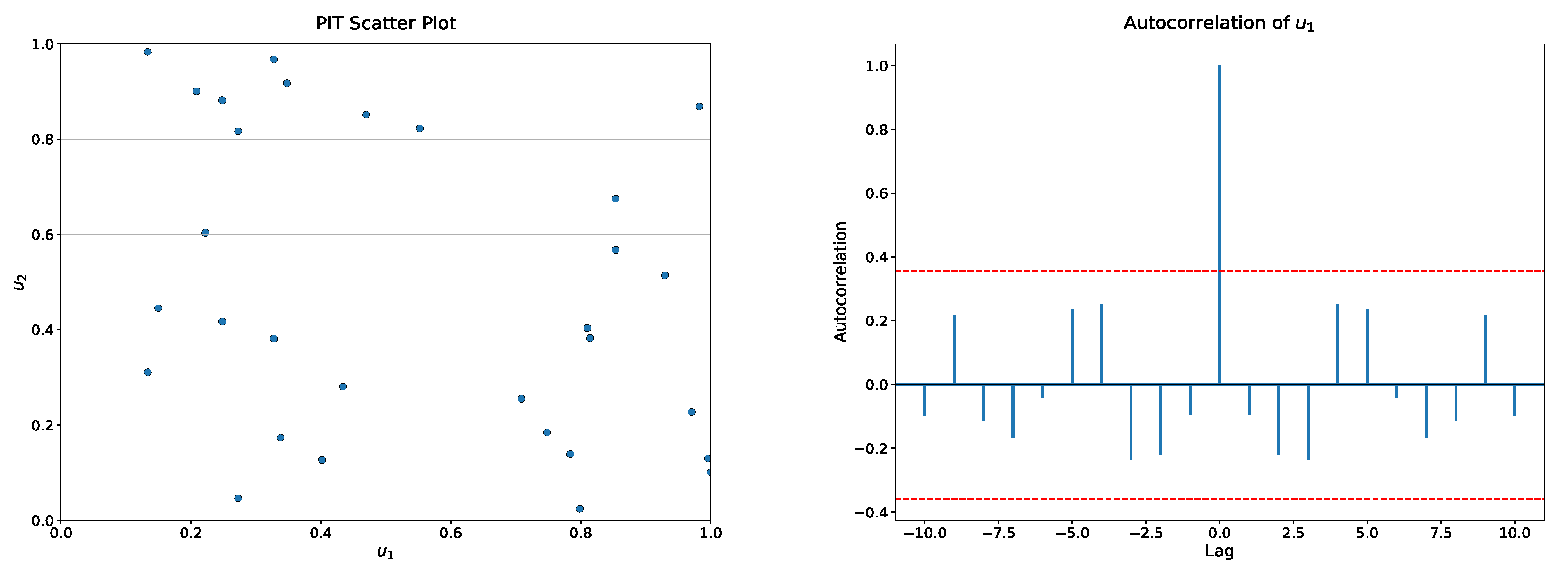

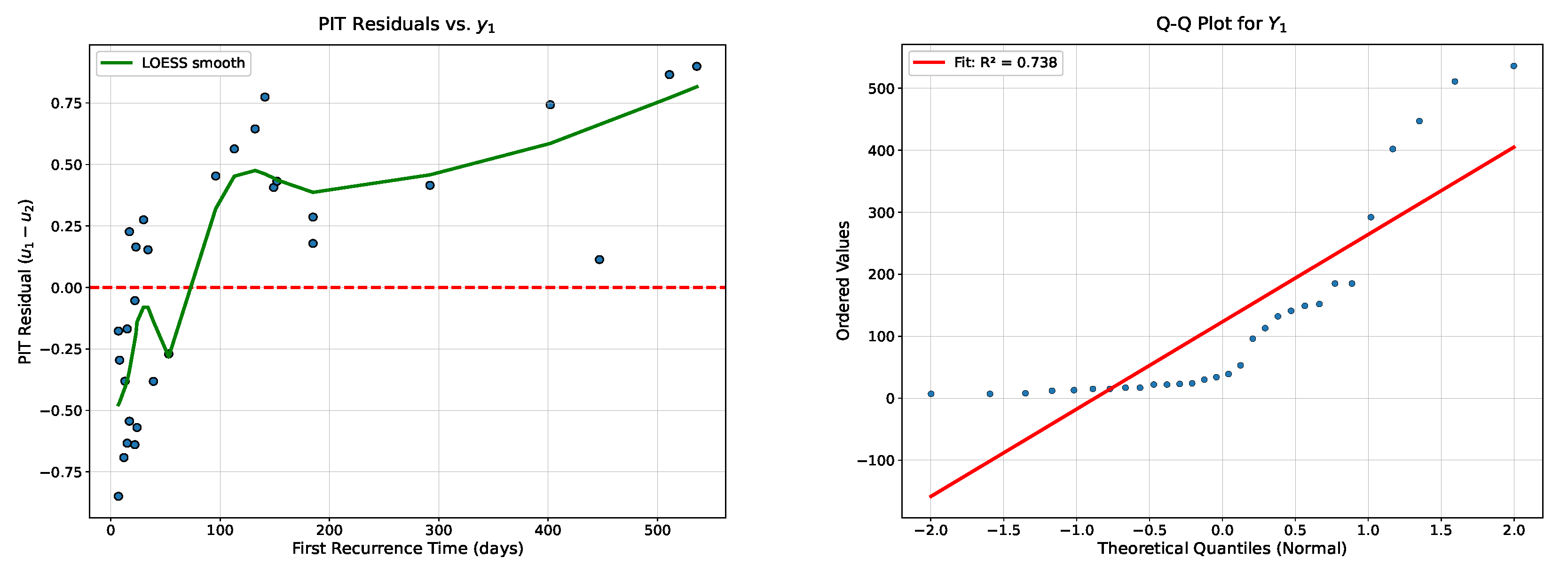

4.2. Probability Integral Transform (PIT) Analysis

5. Conclusions

- A significant construction principle combining the log-logistic and Gompertz mechanisms within a bounded support, offering richer tail behavior and greater shape adaptability than classical bivariate models.

- A complete derivation of the main statistical properties, including joint survival and hazard functions, conditional densities, and moment structure, all presented in analytically consistent and interpretable forms.

- jointly controls decay rate and interdependence;

- shape the local hazard asymmetry;

- defines the natural operational bound.

- Generalized dependence structures: Although this paper used a shared exponential kernel through , extensions to alternative dependence mechanisms (e.g., Farlie–Gumbel–Morgenstern or Archimedean-type kernels) could adapt the model to different correlation profiles.

- Multivariate extensions: The TY-based construction principle can be generalized to d-dimensional bounded lifetime data, enabling the modeling of multiple correlated subsystems under a unified bounded framework.

- Applied domains: Potential applications include biological growth modeling, environmental bounded processes, mechanical fatigue under constraints, and bounded reliability networks where dependence and saturation coexist.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nadarajah, S.; Kotz, S. The beta exponential distribution. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2006, 91, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.M.; Ortega, E.M.; Nadarajah, S. The Kumaraswamy Weibull distribution with application to failure data. J. Frankl. Inst. 2010, 347, 1399–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah, S.; Tahir, M. Parameter induction in continuous univariate distributions. An. Acad. Bras. CiêNcias 2015, 87, 539–568. [Google Scholar]

- Sklar, M. Fonctions de répartition à n dimensions et leurs marges. Ann. L’Isup 1959, 8, 229–231. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, H. Multivariate Models and Dependence Concepts; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen, R.B. An Introduction to Copulas, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Durante, F.; Sempi, C. Principles of Copula Theory; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; Volume 474. [Google Scholar]

- Genest, C.; Favre, A.C. Everything you always wanted to know about copula modeling but were afraid to ask. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2007, 12, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.M.; Emura, T.; Fan, T.H. Reliability inference for a copula-based series system life test under multiple type-I censoring. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2016, 65, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, C.A.; Nadarajah, S.; Moala, F.A.; Bakouch, H.S.; Alghamdi, S. Bayesian Inference for Copula-Linked Bivariate Generalized Exponential Distributions: A Comparative Approach. Axioms 2025, 14, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, D.G. A model for association in bivariate life tables and its application in epidemiological studies of familial tendency in chronic disease incidence. Biometrika 1978, 65, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbe, P.; Genest, C.; Ghoudi, K.; Rémillard, B. On Kendall’s process. J. Multivar. Anal. 1996, 58, 197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.K.; Zimmer, D.M. Copula modeling: An introduction for practitioners. Found. Trends® Econom. 2007, 1, 1–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, H. Dependence Modeling with Copulas; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Muse, A.H. On the log-logistic distribution and its generalizations: A survey. Int. J. Stat. Probab. 2021, 10, 93–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, I.; Ng, H.K.T. Hidden truncation models: Theory and applications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2025, 17, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, D. Einfache beispiele zweidimensionaler verteilungen. Mitteilingsblatt Math. Stat. 1956, 8, 234–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ganji, M.; Bevrani, H.; Hami Golzar, N. A new method for generating continuous bivariate distribution families. J. Iran. Stat. Soc. 2022, 17, 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. Estimating the association parameter for copula models under dependent censoring. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. Stat. Methodol. 2003, 65, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Frees, E.W.; Zhang, Z. A generalized beta copula with applications in modeling multivariate long-tailed data. Insur. Math. Econ. 2011, 49, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilchrist, C.A.; Aisbett, C.W. Regression with frailty in survival analysis. Biometrics 1991, 47, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotz, S.; Balakrishnan, N.; Johnson, N.L. Continuous Multivariate Distributions, Volume 1: Models and Applications (Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics); John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Elaal, M.K.; Jarwan, R.S. Inference of bivariate generalized exponential distribution based on copula functions. Appl. Math. Sci. 2017, 11, 1155–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Size | Pearson | Spearman | Kendall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0.3984 | 0.3452 | 0.2449 |

| 40 | 0.4034 | 0.3502 | 0.2450 |

| 65 | 0.4062 | 0.3518 | 0.2440 |

| 125 | 0.4078 | 0.3540 | 0.2438 |

| 195 | 0.4103 | 0.3573 | 0.2454 |

| 250 | 0.4105 | 0.3571 | 0.2450 |

| 500 | 0.4110 | 0.3577 | 0.2449 |

| Sample Size | Pearson | Spearman | Kendall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0.3430 | 0.3159 | 0.2232 |

| 40 | 0.3459 | 0.3200 | 0.2230 |

| 65 | 0.3473 | 0.3215 | 0.2221 |

| 125 | 0.3488 | 0.3236 | 0.2220 |

| 195 | 0.3514 | 0.3268 | 0.2235 |

| 250 | 0.3512 | 0.3266 | 0.2232 |

| 500 | 0.3518 | 0.3271 | 0.2231 |

| Sample Size | Pearson | Spearman | Kendall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0.1294 | 0.1160 | 0.0807 |

| 40 | 0.1294 | 0.1163 | 0.0797 |

| 65 | 0.1294 | 0.1163 | 0.0790 |

| 125 | 0.1308 | 0.1175 | 0.0793 |

| 195 | 0.1328 | 0.1198 | 0.0805 |

| 250 | 0.1329 | 0.1198 | 0.0804 |

| 500 | 0.1331 | 0.1199 | 0.0803 |

| Sample Size | Bias | MSE | Lower CI | Upper CI | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.0061 | 0.0001 | 1.2281 | 1.2288 | 0.99 |

| 40 | −0.0036 | 0.0000 | 1.2306 | 1.2311 | 0.99 |

| 65 | −0.0024 | 0.0000 | 1.2320 | 1.2323 | 0.99 |

| 125 | −0.0012 | 0.0000 | 1.2332 | 1.2334 | 0.98 |

| 195 | −0.0008 | 0.0000 | 1.2337 | 1.2338 | 0.98 |

| 250 | −0.0006 | 0.0000 | 1.2339 | 1.2340 | 0.97 |

| 500 | −0.0002 | 0.0000 | 1.2342 | 1.2344 | 0.96 |

| 25 | 0.0801 | 0.0685 | 0.3891 | 0.4202 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 0.0516 | 0.0371 | 0.3645 | 0.3877 | 0.99 |

| 65 | 0.0382 | 0.0215 | 0.3539 | 0.3716 | 0.99 |

| 125 | 0.0197 | 0.0090 | 0.3384 | 0.3500 | 0.98 |

| 195 | 0.0196 | 0.0075 | 0.3388 | 0.3494 | 0.98 |

| 250 | 0.0129 | 0.0052 | 0.3329 | 0.3419 | 0.97 |

| 500 | 0.0109 | 0.0036 | 0.3317 | 0.3392 | 0.96 |

| 25 | 1.0401 | 8.0651 | 3.1997 | 3.5295 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 0.5740 | 3.2004 | 2.7929 | 3.0040 | 0.99 |

| 65 | 0.3681 | 1.4975 | 2.6198 | 2.7654 | 0.99 |

| 125 | 0.1900 | 0.5870 | 2.4680 | 2.5610 | 0.98 |

| 195 | 0.1724 | 0.4555 | 2.4560 | 2.5378 | 0.98 |

| 250 | 0.1154 | 0.3170 | 2.4052 | 2.4745 | 0.97 |

| 500 | 0.0763 | 0.1821 | 2.3743 | 2.4273 | 0.96 |

| 25 | 0.1183 | 0.1285 | 1.6403 | 1.6826 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 0.0659 | 0.0664 | 1.5936 | 1.6246 | 0.99 |

| 65 | 0.0507 | 0.0401 | 1.5819 | 1.6060 | 0.99 |

| 125 | 0.0253 | 0.0184 | 1.5602 | 1.5769 | 0.98 |

| 195 | 0.0237 | 0.0138 | 1.5597 | 1.5741 | 0.98 |

| 250 | 0.0156 | 0.0101 | 1.5526 | 1.5651 | 0.97 |

| 500 | 0.0119 | 0.0058 | 1.5503 | 1.5598 | 0.96 |

| Sample Size | Bias | MSE | Lower CL | Upper CL | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.0107 | 0.0002 | 1.0231 | 1.0244 | 0.99 |

| 40 | −0.0065 | 0.0001 | 1.0276 | 1.0285 | 0.99 |

| 65 | −0.0041 | 0.0000 | 1.0301 | 1.0306 | 1.00 |

| 125 | −0.0021 | 0.0000 | 1.0323 | 1.0325 | 0.98 |

| 195 | −0.0013 | 0.0000 | 1.0331 | 1.0333 | 0.98 |

| 250 | −0.0011 | 0.0000 | 1.0333 | 1.0334 | 0.98 |

| 500 | −0.0005 | 0.0000 | 1.0339 | 1.0340 | 0.99 |

| 25 | 2.1208 | 44.2963 | 7.0533 | 7.8373 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 1.0254 | 15.7964 | 6.1111 | 6.5886 | 0.99 |

| 65 | 0.5508 | 7.7252 | 5.7061 | 6.0445 | 1.00 |

| 125 | 0.2335 | 3.1887 | 5.4472 | 5.6687 | 0.98 |

| 195 | 0.1490 | 2.0831 | 5.3836 | 5.5634 | 0.98 |

| 250 | 0.0098 | 1.3728 | 5.2610 | 5.4076 | 0.98 |

| 500 | 0.0041 | 0.8956 | 5.2697 | 5.3876 | 0.99 |

| 25 | 0.1718 | 0.4864 | 1.0543 | 1.1383 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 0.0851 | 0.2027 | 0.9822 | 1.0371 | 0.99 |

| 65 | 0.0403 | 0.1092 | 0.9444 | 0.9851 | 1.00 |

| 125 | 0.0234 | 0.0496 | 0.9340 | 0.9618 | 0.98 |

| 195 | 0.0179 | 0.0358 | 0.9306 | 0.9542 | 0.98 |

| 250 | −0.0008 | 0.0228 | 0.9142 | 0.9331 | 0.98 |

| 500 | −0.0020 | 0.0154 | 0.9147 | 0.9302 | 0.99 |

| 25 | 0.0986 | 0.1233 | 1.8209 | 1.8628 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 0.0438 | 0.0628 | 1.7716 | 1.8023 | 0.99 |

| 65 | 0.0247 | 0.0408 | 1.7554 | 1.7804 | 1.00 |

| 125 | 0.0084 | 0.0195 | 1.7428 | 1.7603 | 0.98 |

| 195 | 0.0039 | 0.0148 | 1.7395 | 1.7547 | 0.98 |

| 250 | −0.0045 | 0.0099 | 1.7325 | 1.7450 | 0.98 |

| 500 | −0.0027 | 0.0069 | 1.7353 | 1.7457 | 0.99 |

| Sample Size | Bias | MSE | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.2038 | 0.0775 | 19.8190 | 19.8425 | 1.00 |

| 40 | −0.1265 | 0.0307 | 19.9005 | 19.9155 | 1.00 |

| 65 | −0.0831 | 0.0130 | 19.9466 | 19.9563 | 1.00 |

| 125 | −0.0419 | 0.0034 | 19.9900 | 19.9951 | 1.00 |

| 195 | −0.0265 | 0.0015 | 20.0063 | 20.0097 | 1.00 |

| 250 | −0.0221 | 0.0009 | 20.0111 | 20.0137 | 1.00 |

| 500 | −0.0108 | 0.0002 | 20.0231 | 20.0244 | 1.00 |

| 25 | 2.7259 | 175.8817 | 17.2460 | 18.8548 | 1.00 |

| 40 | 1.7477 | 95.4554 | 16.4764 | 17.6680 | 1.00 |

| 65 | 0.9155 | 44.5243 | 15.8303 | 16.6496 | 1.00 |

| 125 | 0.5141 | 19.1914 | 15.5690 | 16.1083 | 1.00 |

| 195 | 0.5422 | 13.0651 | 15.6452 | 16.0882 | 1.00 |

| 250 | 0.1506 | 9.0702 | 15.2887 | 15.6616 | 1.00 |

| 500 | 0.1311 | 4.8373 | 15.3195 | 15.5916 | 1.00 |

| 25 | 4.6981 | 408.4917 | 24.4042 | 26.8410 | 1.00 |

| 40 | 2.5984 | 174.1152 | 22.7211 | 24.3247 | 1.00 |

| 65 | 1.3996 | 93.0438 | 21.7326 | 22.9156 | 1.00 |

| 125 | 0.7974 | 37.8744 | 21.3437 | 22.1001 | 1.00 |

| 195 | 0.8093 | 27.7004 | 21.4115 | 22.0562 | 1.00 |

| 250 | 0.1898 | 18.4382 | 20.8485 | 21.3802 | 1.00 |

| 500 | 0.1973 | 9.6835 | 20.9293 | 21.3142 | 1.00 |

| 25 | 0.2124 | 1.2350 | 5.8880 | 6.0232 | 1.00 |

| 40 | 0.1198 | 0.6838 | 5.8123 | 5.9137 | 1.00 |

| 65 | 0.0773 | 0.4187 | 5.7807 | 5.8603 | 1.00 |

| 125 | 0.0437 | 0.1964 | 5.7596 | 5.8142 | 1.00 |

| 195 | 0.0476 | 0.1415 | 5.7676 | 5.8139 | 1.00 |

| 250 | 0.0075 | 0.1049 | 5.7306 | 5.7707 | 1.00 |

| 500 | 0.0120 | 0.0550 | 5.7407 | 5.7697 | 1.00 |

| Size | Average Bias | Average MSE | CI Lower | CI Upper | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.007 | 0.000 | 1.228 | 1.228 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −0.004 | 0.000 | 1.229 | 1.230 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −0.003 | 0.000 | 1.232 | 1.232 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 1.233 | 1.233 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 1.234 | 1.234 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 1.234 | 1.234 | 1.0 |

| 500 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.234 | 1.234 | 1.0 |

| 25 | 0.019 | 0.054 | 0.329 | 0.358 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −0.001 | 0.026 | 0.313 | 0.333 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −0.014 | 0.013 | 0.303 | 0.318 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.022 | 0.007 | 0.297 | 0.307 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.032 | 0.005 | 0.288 | 0.296 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.034 | 0.003 | 0.288 | 0.292 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −0.034 | 0.003 | 0.288 | 0.292 | 1.0 |

| 25 | 6.201 | 125.820 | 7.947 | 9.105 | 1.0 |

| 40 | 4.708 | 45.543 | 6.733 | 7.332 | 1.0 |

| 65 | 4.044 | 27.420 | 6.163 | 6.575 | 1.0 |

| 125 | 3.588 | 17.530 | 5.778 | 6.046 | 1.0 |

| 195 | 3.275 | 12.906 | 5.508 | 5.691 | 1.0 |

| 250 | 3.183 | 12.052 | 5.422 | 5.593 | 1.0 |

| 500 | 3.154 | 10.763 | 5.423 | 5.535 | 1.0 |

| 25 | 0.014 | 0.101 | 1.538 | 1.577 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −0.015 | 0.059 | 1.513 | 1.542 | 0.999 |

| 65 | −0.033 | 0.033 | 1.499 | 1.521 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.051 | 0.020 | 1.484 | 1.500 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.062 | 0.014 | 1.475 | 1.487 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.066 | 0.013 | 1.471 | 1.483 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −0.067 | 0.009 | 1.472 | 1.480 | 1.0 |

| Size | Average Bias | Average MSE | CI Lower | CI Upper | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.028 | 0.001 | 1.005 | 1.008 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −0.018 | 0.001 | 1.015 | 1.017 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −0.012 | 0.000 | 1.022 | 1.023 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.006 | 0.000 | 1.028 | 1.029 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.004 | 0.000 | 1.030 | 1.031 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.003 | 0.000 | 1.032 | 1.033 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −0.002 | 0.000 | 1.033 | 1.033 | 1.0 |

| 25 | 0.920 | 29.637 | 5.912 | 6.577 | 1.0 |

| 40 | 0.599 | 13.911 | 5.695 | 6.151 | 1.0 |

| 65 | 0.319 | 8.630 | 5.462 | 5.824 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.061 | 2.819 | 5.159 | 5.367 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.069 | 1.796 | 5.173 | 5.339 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.219 | 1.387 | 5.034 | 5.178 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −0.266 | 0.704 | 5.009 | 5.108 | 1.0 |

| 25 | 1.773 | 6.797 | 2.579 | 2.815 | 1.0 |

| 40 | 1.697 | 4.794 | 2.536 | 2.707 | 1.0 |

| 65 | 1.628 | 3.888 | 2.484 | 2.622 | 1.0 |

| 125 | 1.525 | 2.803 | 2.407 | 2.492 | 1.0 |

| 195 | 1.529 | 2.646 | 2.419 | 2.488 | 1.0 |

| 250 | 1.482 | 2.430 | 2.376 | 2.436 | 1.0 |

| 500 | 1.472 | 2.278 | 2.376 | 2.417 | 1.0 |

| 25 | 0.027 | 0.117 | 1.749 | 1.791 | 1.0 |

| 40 | 0.020 | 0.071 | 1.746 | 1.779 | 1.0 |

| 65 | 0.001 | 0.046 | 1.731 | 1.758 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.015 | 0.021 | 1.719 | 1.737 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.014 | 0.014 | 1.722 | 1.737 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.029 | 0.011 | 1.708 | 1.720 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −0.029 | 0.006 | 1.710 | 1.719 | 1.0 |

| Size | Average Bias | Average MSE | CI Lower | CI Upper | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.358 | 0.231 | 19.657 | 19.697 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −0.213 | 0.090 | 19.808 | 19.835 | 0.999 |

| 65 | −0.138 | 0.036 | 19.889 | 19.905 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.070 | 0.010 | 19.960 | 19.969 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.047 | 0.004 | 19.985 | 19.990 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.036 | 0.003 | 19.995 | 19.999 | 0.999 |

| 500 | −0.019 | 0.001 | 20.014 | 20.017 | 0.998 |

| 25 | 15.348 | 875.077 | 29.105 | 32.240 | 1.0 |

| 40 | 13.988 | 523.464 | 28.190 | 30.435 | 0.999 |

| 65 | 12.718 | 321.472 | 27.259 | 28.825 | 1.0 |

| 125 | 12.266 | 226.520 | 27.050 | 28.131 | 1.0 |

| 195 | 11.456 | 177.620 | 26.359 | 27.203 | 1.0 |

| 250 | 11.321 | 160.015 | 26.296 | 26.996 | 0.999 |

| 500 | 11.264 | 144.375 | 26.328 | 26.848 | 0.998 |

| 25 | 110.265 | 37,037.046 | 121.413 | 140.966 | 1.0 |

| 40 | 94.324 | 16,843.520 | 109.721 | 120.777 | 0.999 |

| 65 | 85.648 | 10,841.493 | 102.903 | 110.243 | 1.0 |

| 125 | 80.890 | 8042.076 | 99.414 | 104.214 | 1.0 |

| 195 | 76.721 | 6743.746 | 95.831 | 99.461 | 1.0 |

| 250 | 75.033 | 6217.337 | 94.455 | 97.461 | 0.999 |

| 500 | 74.267 | 5830.383 | 94.091 | 96.293 | 0.998 |

| 25 | 1.268 | 3.587 | 6.924 | 7.098 | 1.0 |

| 40 | 1.170 | 2.494 | 6.847 | 6.979 | 0.999 |

| 65 | 1.131 | 1.942 | 6.824 | 6.925 | 1.0 |

| 125 | 1.102 | 1.559 | 6.809 | 6.882 | 1.0 |

| 195 | 1.058 | 1.340 | 6.772 | 6.830 | 1.0 |

| 250 | 1.025 | 1.209 | 6.743 | 6.792 | 0.999 |

| 500 | 1.025 | 1.137 | 6.749 | 6.786 | 0.998 |

| Size | Average Bias | Average MSE | CI Lower | CI Upper | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.007 | 0.000 | 1.227 | 1.228 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −0.004 | 0.000 | 1.230 | 1.231 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −0.003 | 0.000 | 1.232 | 1.232 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 1.233 | 1.233 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 1.234 | 1.234 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 1.234 | 1.234 | 1.0 |

| 500 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.234 | 1.234 | 0.998 |

| 25 | −0.325 | 0.105 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −0.325 | 0.105 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −0.325 | 0.105 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.324 | 0.105 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 |

| 195 | −0.324 | 0.105 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.324 | 0.105 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 |

| 500 | −0.324 | 0.105 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 |

| 25 | −2.325 | 5.403 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −2.325 | 5.403 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −2.325 | 5.403 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −2.324 | 5.403 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 |

| 195 | −2.324 | 5.403 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −2.324 | 5.403 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 |

| 500 | −2.324 | 5.403 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 |

| 25 | −1.543 | 2.381 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −1.543 | 2.381 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −1.543 | 2.381 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −1.543 | 2.381 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 |

| 195 | −1.543 | 2.381 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −1.543 | 2.381 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 |

| 500 | −1.543 | 2.381 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 |

| Size | Average Bias | Average MSE | CI Lower | CI Upper | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.014 | 0.002 | 1.017 | 1.024 | 0.644 |

| 40 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 1.035 | 1.041 | 0.621 |

| 65 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 1.044 | 1.051 | 0.604 |

| 125 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 1.054 | 1.059 | 0.597 |

| 195 | 0.023 | 0.002 | 1.055 | 1.060 | 0.569 |

| 250 | 0.023 | 0.001 | 1.056 | 1.060 | 0.624 |

| 500 | 0.027 | 0.002 | 1.059 | 1.064 | 0.600 |

| 25 | −5.324 | 28.350 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.644 |

| 40 | −5.324 | 28.350 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.621 |

| 65 | −5.324 | 28.350 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.604 |

| 125 | −5.324 | 28.350 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.597 |

| 195 | −5.324 | 28.350 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.569 |

| 250 | −5.324 | 28.350 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.624 |

| 500 | −5.324 | 28.350 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.600 |

| 25 | −0.925 | 0.855 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.644 |

| 40 | −0.925 | 0.855 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.621 |

| 65 | −0.925 | 0.855 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.604 |

| 125 | −0.924 | 0.854 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.597 |

| 195 | −0.924 | 0.855 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.569 |

| 250 | −0.923 | 0.853 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.624 |

| 500 | −0.924 | 0.854 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.600 |

| 25 | −1.743 | 3.039 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.644 |

| 40 | −1.743 | 3.039 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.621 |

| 65 | −1.743 | 3.039 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.604 |

| 125 | −1.743 | 3.039 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.597 |

| 195 | −1.743 | 3.039 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.569 |

| 250 | −1.743 | 3.039 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.624 |

| 500 | −1.743 | 3.039 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.600 |

| Size | Average Bias | Average MSE | CI Lower | CI Upper | Conv. Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −0.342 | 0.213 | 19.674 | 19.712 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −0.214 | 0.086 | 19.808 | 19.832 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −0.137 | 0.036 | 19.889 | 19.906 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −0.075 | 0.011 | 19.955 | 19.964 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −0.048 | 0.005 | 19.983 | 19.989 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −0.037 | 0.003 | 19.995 | 20.000 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −0.018 | 0.001 | 20.015 | 20.017 | 1.0 |

| 25 | −15.325 | 234.840 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −15.325 | 234.840 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −15.325 | 234.840 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −15.325 | 234.840 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −15.325 | 234.840 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −15.325 | 234.840 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −15.325 | 234.840 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 25 | −20.925 | 437.835 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −20.925 | 437.835 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −20.925 | 437.835 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −20.925 | 437.835 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −20.925 | 437.835 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −20.925 | 437.835 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −20.925 | 437.835 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| 25 | −5.743 | 32.984 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 40 | −5.743 | 32.984 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 65 | −5.743 | 32.984 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 125 | −5.743 | 32.984 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 195 | −5.743 | 32.984 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 250 | −5.743 | 32.984 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| 500 | −5.743 | 32.984 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.0 |

| Model | AIC | BIC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBGLL | 536.000 | 10.682 | — | 9.017 | 0.987 | 336.671 | 681.343 | 686.948 |

| FGMBW | 0.751 | 100.119 | 0.924 | 98.246 | 0.348 | 338.907 | 687.814 | 694.826 |

| FGMBG | 0.677 | 175.526 | 0.923 | 107.753 | 0.379 | 339.492 | 688.984 | 695.986 |

| FGMBGE | 0.666 | 0.006 | 0.925 | 0.009 | 0.378 | 339.545 | 689.090 | 696.106 |

| Model | AD* | CVM | KS | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBGLL | 1.4293 | 0.1915 | 0.1406 | 0.9600 |

| FGMBW | 1.3049 | 0.2290 | 0.1457 | 0.7450 |

| FGMBG | 346.4534 | 7.3315 | 0.7121 | 0.0000 |

| FGMBGE | 6.0462 | 0.8997 | 0.4333 | 0.0065 |

| Parameter | Estimate | Std. Error | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 536.0000 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| 0.9871 | 0.1024 | 0.7866 | 1.1882 | |

| 10.6821 | 4.3092 | 2.2726 | 19.1646 | |

| 9.0179 | 3.2458 | 2.6866 | 15.4102 |

| Distribution | KS | p-Values | CvM | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGLL | 0.106 | 0.745 | 0.058 | 0.708 | |

| Weibull | 0.128 | 0.515 | 0.108 | 0.625 | |

| Gamma | 0.148 | 0.336 | 0.154 | 0.815 | |

| G-exp | 0.152 | 0.309 | 0.164 | 0.855 |

| Distribution | KS | p-Values | CvM | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGLL | 0.104 | 0.763 | 0.086 | 1.123 | |

| Weibull | 0.113 | 0.674 | 0.096 | 0.593 | |

| Gamma | 0.131 | 0.484 | 0.128 | 0.765 | |

| G-exp | 0.134 | 0.459 | 0.134 | 0.795 |

| Parameter | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| (upper bound) | 536.0 | Maximum recurrence time (days) |

| (shape/dependence) | 0.9871 | Kendall’s |

| ( scale) | 10.6821 | First recurrence shape parameter |

| ( scale) | 9.0179 | Second recurrence shape parameter |

| Goodness-of-Fit Tests | p-Value | Interpretation |

| KS test for uniformity | 0.4600 | Well-calibrated |

| KS test for uniformity | 0.7249 | Well-calibrated |

| PIT independence test | 0.0628 | Appropriate dependence |

| Data Summary | ||

| Mean (days) | 123.3 | 99.1 |

| Median (days) | 36.5 | 43.0 |

| Range (days) | [7.0, 536.0] | [4.0, 362.0] |

| Correlation with | 1.000 | −0.039 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alghamdi, S.; Hussain, T.; Bakouch, H.S.; Kachour, M. A Flexible Bivariate Lifetime Model with Upper Bound: Theoretical Development and Lifetime Application. Axioms 2025, 14, 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14120930

Alghamdi S, Hussain T, Bakouch HS, Kachour M. A Flexible Bivariate Lifetime Model with Upper Bound: Theoretical Development and Lifetime Application. Axioms. 2025; 14(12):930. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14120930

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlghamdi, Shuhrah, Tassaddaq Hussain, Hassan S. Bakouch, and Maher Kachour. 2025. "A Flexible Bivariate Lifetime Model with Upper Bound: Theoretical Development and Lifetime Application" Axioms 14, no. 12: 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14120930

APA StyleAlghamdi, S., Hussain, T., Bakouch, H. S., & Kachour, M. (2025). A Flexible Bivariate Lifetime Model with Upper Bound: Theoretical Development and Lifetime Application. Axioms, 14(12), 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14120930