1. Introduction

There are a myriad of sources of data incompleteness, such as manual entry errors, technical failures in data collection systems, incomplete survey responses, and unobserved/latent variables. Such gaps usually correspond to either random anomalies or patterns in the data-generating procedure. In order to interpret the implications of such missing values, some researchers often rely on imputation methods not only to provide missing values but also to investigate the sources and the nature of the respective missingness. This would involve establishing whether the missing values are a mechanism of the observed data or are due to the properties of the larger population from which the data were sampled. Before the groundbreaking research of Rubin [

1], the statistical community did not pay much attention to the possibility of the missing data impacting the analysis. The model applied by Rubin [

1] to classify the missing data mechanisms has formed a foundation for contemporary statistical analysis. On the basis of the correlation of the absence of data with the other values in the dataset, there are three dominant types that are distinguished according to this model, such as Missing at Random (MAR), Not Missing at Random (NMAR), and Missing Completely at Random (MCAR). MCAR is defined as the situation in which the likelihood of the missingness is independent of both observed and unobserved data. MAR enables the missingness to be a function of known variables and not the unknown values. NMAR occurs when the missing data is directly related to the unobserved amount and the mechanism is not negligible. MCAR guarantees that the derivations of the theoretical results will be unbiased, MAR produces systematic bias without modeling, and NMAR generally demands an explicit specification of the mechanism of missing data. This categorization of data has had a significant influence on the methodological development and practical efforts of dealing with incomplete data [

2].

The arithmetic mean is a simple and generally popular measure of central tendency, and its applicability is vast both in the field of science and in practice. It is not only essential in the simplified view of data summarization, but a vital resource in other areas like survey sampling, economics, and environmental monitoring. With such a wide applicability, better accuracy of the estimation of the mean is crucial—particularly when the data to be analyzed are missing or incomplete, which is the case when dealing with survey research and observational studies. Imputation-based strategies have become a common way of dealing with missing observations. Several writers have made contributions to this growing discipline. In one case, ref. [

3] introduced ratio-based estimators that were intended to maximize the precision of mean estimation when imputation is applied. Based on this, Diana and Perri [

4] suggested regression-type estimators that combine auxiliary variables. Al-Omari et al. [

5] optimized ratio-type estimators with known correlation coefficients and used ranked set sampling to maximize the efficiency of estimators, which were further refined by Al-Omari and Bouza [

6]. Refs. [

7,

8] refined optimal imputation schemes to suit the mean estimation, whereas ref. [

9] designed exponential-type estimators to manage the situation of missing data specifically. According to the analysis of refs. [

10,

11], ref. [

12] established imputation-based estimators that use resilient covariance matrices such as Minimum Covariance Determinant (MCD) and Minimum Volume Ellipsoid (MVE). To obtain a more extensive overview of the latest trends in the field of imputation-based mean estimation, interested readers should read the latest article of Pandey et al. [

13], where the authors extensively cover the methodological progress in this field of study.

It is noteworthy that extreme values or outliers may severely skew the estimate of the mean, especially when there is data contamination and classical techniques like the arithmetic mean are used. Acknowledging this shortcoming, a ground-breaking finding by Zaman and Bulut [

14] proposed powerful imputation-based mean estimators that were built on MCD and MVE estimators. These methods are very outlier-tolerant and best suited to non-normally distributed data. Based on this, Bulut and Zaman [

15] went on to develop this methodology. In addition, they optimized the estimation process in a range of sampling designs by maximizing the selection of strong covariance matrices. In another development, Zaman and Bulut [

16] extended the application of MCD and MVE methods to the estimation of the means and the estimation of another simple parameter that is sensitive to outliers, the variance. The effectiveness of this line of research was extended by Shahzad et al. [

12] by adapting the useful framework to the environment of missing data. They designed estimators that can withstand both missingness and contamination, a twofold criticism that is commonly faced by survey and observational research, by integrating MCD and MVE estimators into imputation methods. Alomair and Shahzad [

17] added more innovation by using the same robust framework in the median ranked set sampling scheme. Alomair et al. [

18] created robust mean estimators in the framework of systematic sampling to incorporate MCD-based methods to improve the quality of estimates in a systematic, periodic method of data collection in a structured manner. Their contribution is important to bridge the gap between sound statistical procedures and practical sampling procedures applied in environmental and industrial surveys and to emphasize the increased topicality of robust estimation in the context of real data gathering.

Despite the growing literature on sound statistical techniques, no literature to date focuses specifically on the estimation of the population average under MRCD when the data is incomplete and when an outlier possibly skews it. Guided by this gap, the current research aims to create a type of robust mean estimator within the MRCD framework that would be effective in addressing the twofold challenges of missingness and extreme observations. As far as we know, this is the first study to operationalize MRCD to directly estimate the mean under these circumstances, thus introducing a new contribution in the research of robust statistical inference.

The remainder of this article provides a detailed description of the conceptual and methodological framework of the proposed methods of mean estimation.

Section 2 starts by considering classic imputation-based estimators, especially those produced under ordinary least-squares (OLS) assumptions. These are ratio- and regression-based estimators, including those suggested by [

3], that can be used as the reference point to innovate further.

Section 3 of this study shifts the emphasis to the shortcomings of OLS-based procedures, specifically to their sensitivity to outliers, which has a broader definition as a set of anomalous observations that may bias the estimation of parameters. In

Section 3.2, a new class of mean estimators is presented that are constructed on a logarithmic transformation and MRCD basis. These estimators take advantage of the stabilizing effects of logarithms to work with skewed and heavy-tailed distributions by adding log-based components, as well as giving MRCD the ability to resist anomalies and missingness. All of these sections together constitute the theoretical framework of this paper, creating a strong argument for the relevance and rigour of the suggested methodology when dealing with imperfections of real-world data.

Section 4 and

Section 5 give a numerical study and the conclusions, respectively.

2. Conventional Imputation-Based Mean Estimators

Suppose a countable population, composed of finite elements, has a size of

G and a Simple Random Sample without Replacement (SRSWOR) of size

is selected. Let X and Y represent the study and auxiliary variables, respectively. In the chosen sample, certain units respond, while others do not. Assume that the ratio of participating individuals is denoted by

, participating individuals are a subset denoted by

, and non-participating individuals are a subset represented by

. For units that provide responses, the sample mean of participating individuals of

Y is given by

When the dataset includes non-response, it becomes necessary to impute missing values for those units. Let the imputed values be defined as follows:

in which the imputed value of the non-responsive unit at the

position is denoted as

.

According to this method of imputation, the estimator of

, can be stated as

Considering

, the observed responses, the mean imputation approach yields a frequently used estimator of the population mean:

The measure of dispersion of

is represented by

where

is the population variance of

Y.

The literature has discussed various imputation methods to improve the estimation of

, in particular under SRS, to reduce the issue of missing data in a practical survey setup. It is necessary to mention that Kadilar and Cingi [

3] performed a systematic analysis of the traditional ratio-type regression estimators that are based on the OLS framework, which is specifically designed to be applied to situations where there are missing data in sample surveys. They divided their analysis into three different cases, all of which considered various patterns of data incompleteness. Case I assumes that only

Y is missing and that

X is fully observed. Case II is a more complicated case, where both

are missing. Still, the population value of

X,

, is known. Lastly, Case III is the most general and difficult case where the missing data are on both Y and X, and the average of the population

is unknown as well. In all these situations, Kadilar and Cingi [

3] suggested special estimators to enhance accuracy in estimating the population means when partial data exists. The overall shape of estimators of the study variable Y based on these frameworks is given in their work, and it has the following form:

By derivation, the MSE of Equation (

6) is

with

, variances

, and covariance

.

Rather et al. [

19] developed M-type mean estimators using Uk’s redescending coefficient

of Khalil et al. [

20]. By following Kadilar and Cingi [

3], we can obtain the imputed versions of Rather et al. [

19] estimators for all the three discussed situations:

By derivation, the MSE of Equation (

10) is

For more details about redescending M estimators, readers can see [

21].

3. MRCD and Proposed Estimators

The OLS approach is commonly considered a paradigmatic parametric method of statistical modeling mainly because of its ease of calculation and its interpretability. It works especially well in the estimation of parameters in a linear regression model, as long as the classical conditions of OLS, including linearity, homoscedasticity, and independence, are met. In such a perfect scenario, OLS produces the Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUEs), as underlined by ref. [

22]. Nonetheless, the significant weakness of OLS is that it is vulnerable to extreme values that can lead to the misrepresentation of parameter estimates and diminish the reliability of the results. This weakness is reflected by its breakdown point, also defined by Ref. [

23] and elaborated by ref. [

24], the lowest fraction of contaminated data that can lead an estimator to produce arbitrarily inaccurate results. In OLS estimators, the breakdown point is as small as

, which means that they are not very robust when anomalous data are present. Seber and Lee [

25] describe the process of this sensitivity and explain two key factors that cause it: (i) the fact that the use of squared residuals magnifies the effect of large deviations, which in turn disproportionately affect the estimation process, and (ii) the fact that a non-robust average, like the arithmetic mean, causes large deviations to have a significant effect, especially when large squared residuals are involved. Such properties explain why there is a need to consider alternative strong approaches when handling datasets that tend to have anomalies.

In contrast to the OLS procedure, which is extremely sensitive to outliers and is based on equally dispersed, normally distributed errors, the Minimum Regularized Covariance Determinant (MRCD) estimator is a powerful alternative to investigate multivariate data. MRCD aims to provide a more stable estimation in cases where a significant percentage of the data is contaminated, as data extremes are down-weighted or ignored in subset selection. In comparison to OLS, which may be highly distorted due to a single influential point, MRCD will be highly efficient on clean data with a significant increase in robustness when outliers or leverage points are present, as explained by Boudt et al. [

26]. In addition, MRCD presents a regularization procedure that makes the covariance matrix positive-definite in high dimensions where standard covariance estimators notoriously break down. It is especially useful in contemporary datasets with a large variable-to-sample ratio, as it allows successful estimation without overfitting or singularity concerns, as Hubert et al. [

27] point out. Therefore, MRCD is an efficient instrument of sound statistical inference, which successfully manages to address the two extremes of theoretical resilience and practical application.

3.1. Statistical Foundations of MRCD

MRCD is an enhancement of the classical MCD(CMCD) estimator, scaled to a high-dimensional data structure where

. CMCD aims to estimate the location and scatter of the data with the smallest determinant of the sample covariance matrix of the CMCD-based subset of the data. Nevertheless, the method fails to be stable or defined in high-dimensional problems because of the problem of singularity in the covariance matrix. MRCD lifts this restriction by adding a regularization term. With a target matrix

T (well-conditioned positive-definite matrix) and a regularization parameter,

, the MRCD covariance of a subset

H is expressed as follows:

with

= covariance matrix of the subset

H of the sample. This convex combination is also positive-definite even in the case of a singular

, which makes MRCD a viable robust estimation tool in high-dimensional models [

26].

In terms of computational requirements of MRCD, the regularization parameter is used to regulate the extent of shrinkage towards the target matrix T, with smaller values emphasizing the subset covariance and larger values promoting numerical stability with contamination or when close to a singularity. Similarly, the selection of T is a determinant factor in estimator behavior; typical selections are the identity matrix or a diagonal matrix of robust scale estimates, both of which are positive-definite and stabilize the optimization process. These elements have a significant effect on the accuracy and stability of the final MRCD-based estimators.

MRCD is not sensitive to normality or homoscedasticity, which makes it highly flexible to use in real-world scenarios. The target matrix T may be specified by a priori choice or default to the identity, and the regularization parameter may typically be chosen based on information about the data, e.g., minimizing the condition number or maximizing cross-validated performance, etc.

To ensure clarity and reproducibility, we used the MRCD implementation in our study based exactly on the algorithm and defaults of the

CovMrcd() function of the

rrcov package in

R. In this implementation,

T is not constructed manually as a target matrix, but

CovMrcd() will create

T in the form of a positive-definite matrix that is reduced to a diagonal matrix of robust scale estimates of the sample covariance matrix, which is how Boudt et al. [

26] discuss the construction of

T. Similarly

is not user-specified but an internally selected parameter of the algorithm to meet the condition number and positive-definiteness requirements of an MRCD procedure. The size of the subset is chosen automatically by

CovMrcd() according to the desired trimming proportion (default

), and this is the equivalent of a breakdown point of about 25%. Lastly, according to the design of

CovMrcd, the formulation of MRCD is calculated on the entire-case respondent set

because the default incomplete observations are not included in the formulation. The resulting strong location and scatter estimates are further utilized directly in our suggested imputation estimator equations.

3.2. Proposed Estimators

Classical mean estimators are highly sensitive and therefore unreliable in the presence of outliers or missing observations. In comparison, MRCD provides a subset-based approach that isolates clean data and regularizes the covariance structure, hence permitting strong location estimation. Precisely, the mean estimate is obtained as the subset

H chosen by MRCD as follows:

Logarithmic transformations have proven to be very useful in handling variables that vary dramatically in scale or are skewed in distribution. The functions prove particularly useful in modeling such phenomena as exponential growth, decay, and asymmetric data, which are regularly employed in such fields as epidemiology, environmental science, and economic analysis. Inspired by all these benefits, the current work integrates the utilization of logarithmic terms in the construction of new estimators. By following [

13,

28,

29], we suggest three new estimators that will integrate the robustness of MRCD with the stabilizing characteristics of the logarithmic-Sin transformation. The estimators are intended to be computationally efficient and methodologically simplified, with the only use of a logarithmic-Sin component.

Let

and

be the subsets of the sample with respect to respondents and non-respondents, respectively, under the MRCD framework. In order to offset missing values under this framework, the imputation strategies presented below have been proposed, which focus on enhancing the accuracy of estimation but maintain robustness:

where

,

,

,

, and

are the MRCD-based averages. Further, it is important to note that, in coming lines, any notation containing

in the subscript represents that it is calculated through MRCD. The constants,

,

, and

should be solved to ensure the minimization of the resulting MSE. The resulting point estimator obtained through the chosen strategy of imputation is presented by

Equation (15) can be used to find the point estimators of the average value of Y, denoted as

, using the imputation method described in Equations (12)–(14) in the following way:

3.3. Properties of , , and

When assessing the usefulness of a particular estimator, one must bear in mind the area in which it is specified. The estimators that have been postulated in this paper are founded on the logarithmic transformation,

, which automatically presupposes that the input variable,

x, should be positive. This field of application constrains the usage of such estimators to datasets in which the values of

x all exceed one. Alternatively, the use of transformations such as

eases this limitation owing to the fact that the domain of the sine function can take a wider range of

x, hence making the estimator more versatile in a variety of empirical situations. Also, in large-sample limits, the suggested estimators are consistent; i.e., when

is large, the estimators converge to the true value, i.e.,

. Two important measures are used to evaluate the performance and dependability of such estimators, which are bias and MSE. These measures are analytically expressed under the condition of the big size sample and using appropriate transformations of the corresponding error terms, as will be described below. The error terms (

’s) with their expectations are

and

where

and

are the population CVs,

are the population variance of study and auxiliary variables, respectively, and

is the correlation between these variables. All these characteristics are calculated using the MRCD location and covariance matrix. It is also worth noting that all the characteristics used in this section were computed using the MRCD method. This is one of the major differences between

and

.

To estimate the bias and MSE of the new estimators, we will start by performing suitable transformations on Equations (16)–(18). These are then extended out in the Taylor series approximation of the logarithmic function with sine, which is

Upon performing the algebraic expansion and simplification, the following forms of the estimators are obtained:

Using large-sample approximations and error expansion, the MSEs of the estimators are derived as follows:

We optimize the MSE expressions with respect to

and

and obtain the best (optimum) constants:

Substituting these optimal values into the corresponding MSE formulas, we get the minimum MSE formulas of both estimators:

Finally, using the optimized values of the constants, the corresponding biases of the estimators are computed as follows:

The main difficulty in applying the suggested imputation-based estimators is the reasonable choice of the constants

,

, and

. These constants are optimally determined to reduce the MSE and are given based on the established parameter,

. Reddy’s [

30] study states that the parameter

K is likely to be stable over time, among different populations and datasets as well. The stability means that, with known

K, the proposed estimators can be easily used in real-life situations with little calibration. Nevertheless, the actual value of the

K may be unavailable in many real-life cases. In these situations, we suggest calculating the constants

,

, and

by means of sample-based statistics, which are as follows:

and the quantities correlation

, mean

, and CVs

are computed using the obtainable

observations. For more details about derivations, please see [

13].

The resulting estimators have the same asymptotic properties, especially in terms of MSE behavior, by substituting the unknown constants in the proposed methodology with their sample-based estimators. This substitution does not jeopardize the statistical efficiency, so the useful implementation of the estimators is also robust and well-grounded. Consequently, the suggested MRCD-based imputation estimators are highly useful in empirical studies and do not contradict their optimal counterparts. These feature makes them a viable and effective substitute for conventional estimators, particularly with missing data and outliers.

4. Numerical Study

We combine an empirical validation strategy with theoretical rigor to ensure that we firmly evaluate both the existing and the proposed estimators. This methodology is operationalized by employing five structured populations. Two of them are based on real datasets, which have been chosen to capture realistic complexities of the real world like non-normality, outliers, and missing values. The other three populations are artificially reproduced under different distributional conditions and contamination to represent different conditions in reality. The actual and the simulated data will be provided to give an insight into the efficiency of the estimator in a wide range of circumstances. The MSE and PRE are effective indicators of accuracy and efficiency, which are the primary points of comparison. Using such a structure, we shall present a weighted and realistic evaluation of the practical feasibility of the estimators.

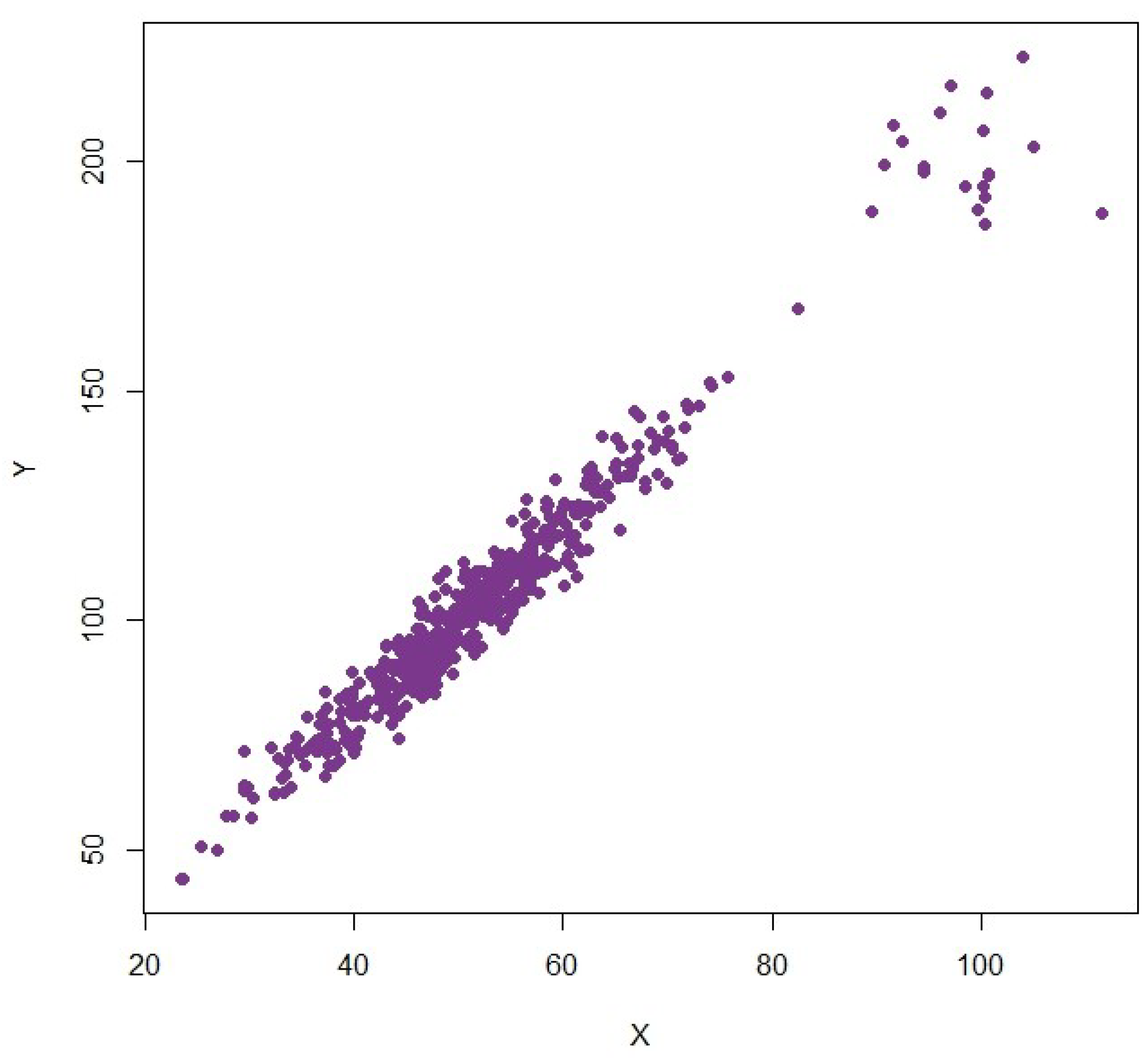

4.1. Simulated Population 1: Bivariate Normal with Injected Outliers

The initial simulated population is created with the help of a bivariate normal distribution to illustrate classical linear association, which is often supposed in numerous statistical approaches. Here

In order to contaminate the data, we choose 20 outliers through the creation of extreme values of distributions with shifted means:

Such outliers are combined with the main data to create a population size of 500 units. This structure provides a controlled environment to evaluate the effect of high-leverage points on traditional and robust estimators.

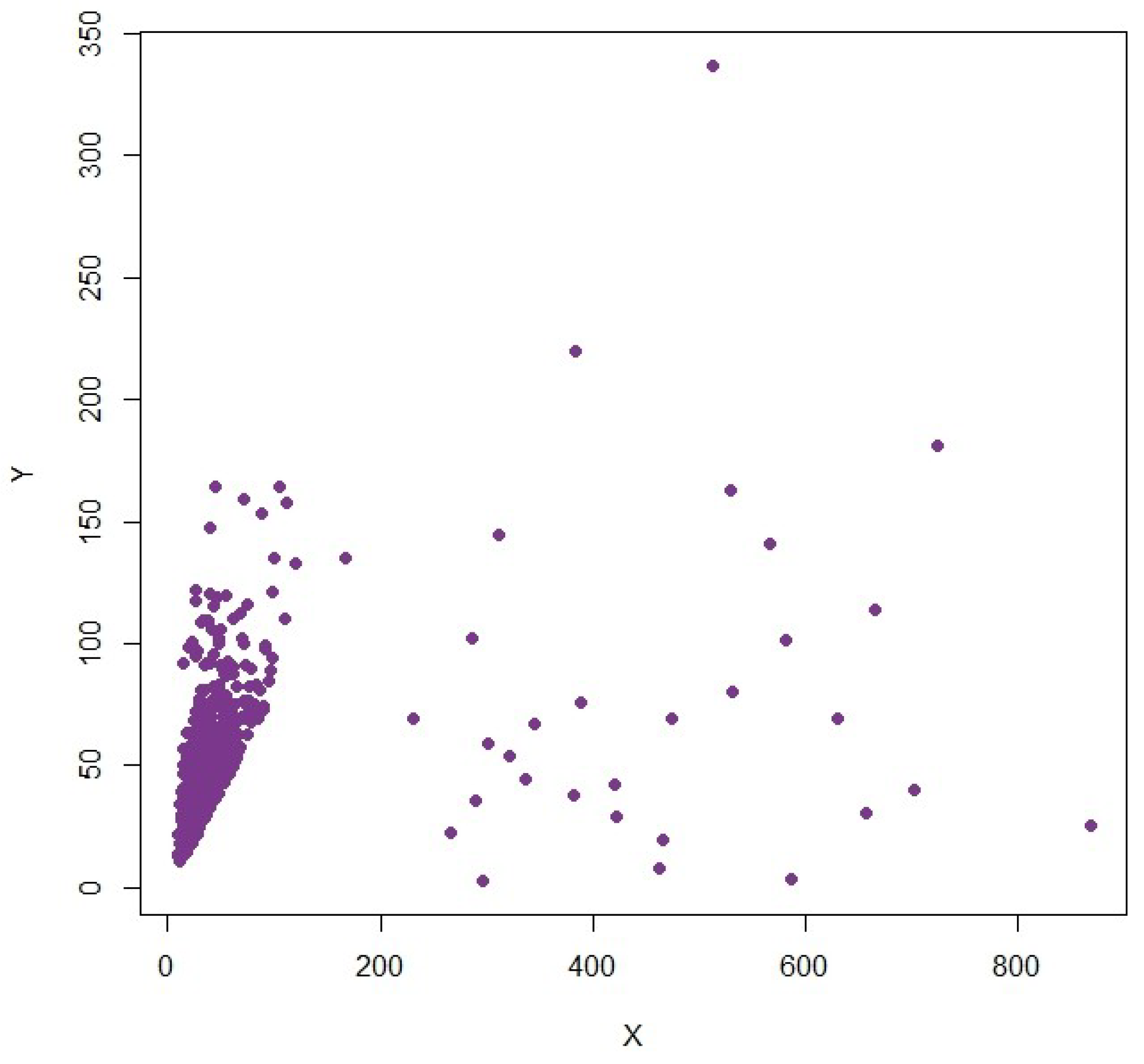

4.2. Simulated Population 2: Log-Normal and Exponential Distributions with Outliers

The second population models a scenario where the data is highly skewed, which is very common in economics and biomedical applications, like studies on income and expenditure. The auxiliary variable, X, will be distributed as a lognormal distribution with parameters, i.e., Lognormal (). The study variable Y is generated using an exponential distribution with the rate parameter of 0.05, and a linear term is included, i.e., . Further, 30 additional values of Xout and Yout are used to add outliers Xout = Lognormal () and Yout = (). Hence, the dataset contains 500 units, and associated with it are high positive skewness and contamination, which qualify it as an appropriate test case to assess robustness in non-normal states.

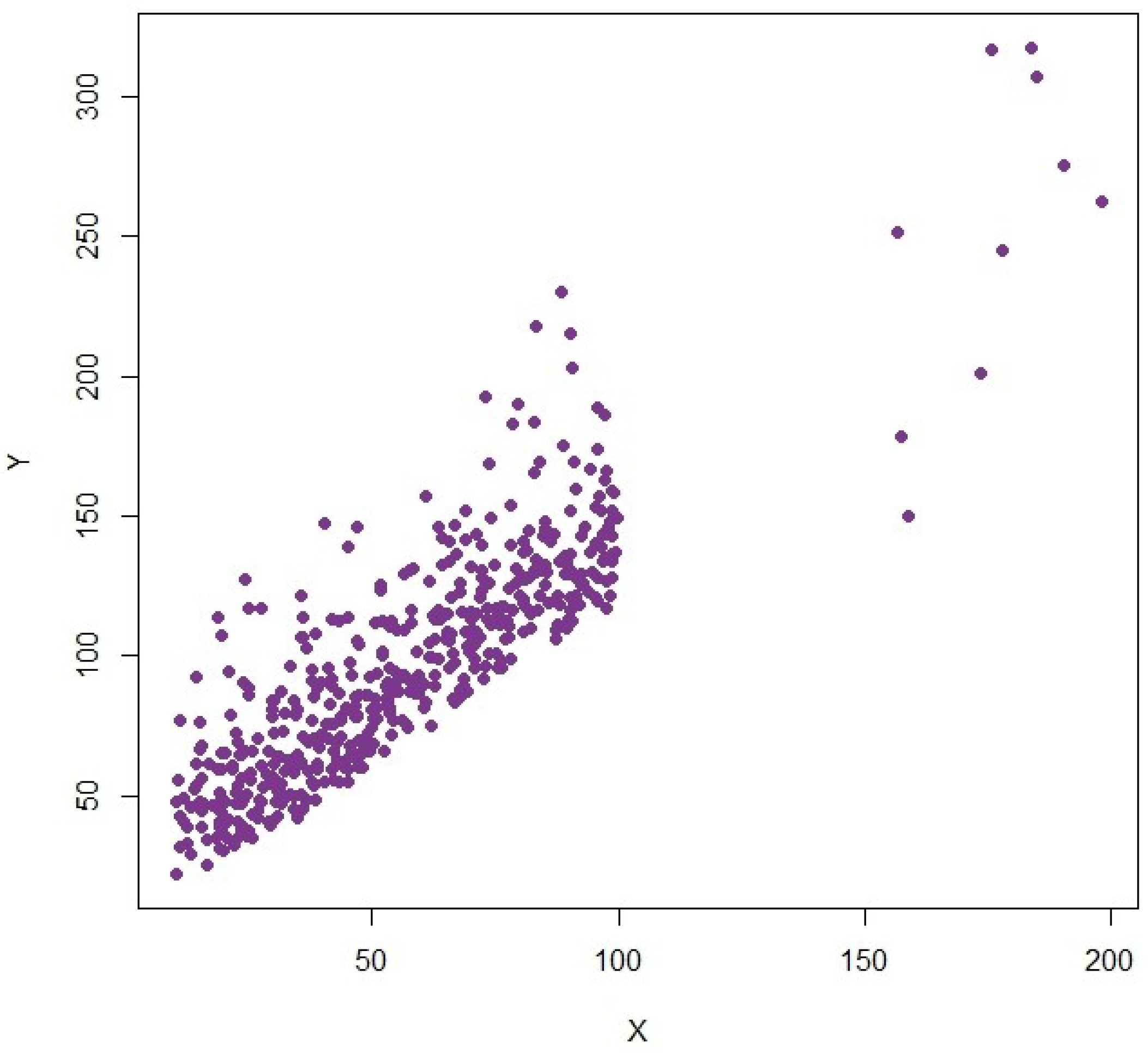

4.3. Simulated Population 3: Uniform and Gamma Distributions with Extreme Events

The third simulated population represents data commonly found in environmental monitoring and engineering studies, where values are often bounded on one end and subject to sporadic extreme events. The auxiliary variable, in this population, is described by a uniform distribution, which will be generated within the range of factors [10, 100] to provide a wide and limited distribution of possible values. The study variable

Y is drawn from a gamma distribution with shape 2 and scale 15 and adjusted with a linear term

. Further, 10 outliers are included with

and

. This structure produces a dataset of 500 observations with mild right-skewness and localized extremes, making it an ideal population for stress-testing estimators under realistic field conditions. The variation plots are provided in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

In order to put incomplete observations in the simulated populations, a simple and reproducible missingness mechanism was used. Once the entire data had been generated, random selection of a given proportion ( say 10 %) of units was made, and the values of those units in the study variable, Y, were assigned a missing value. In order to capture the partial unavailability in the auxiliary variable too, a smaller fraction of observations was further given missing values in X. This general missingness mechanism provides a uniform and regulated measure of missing data in all the simulated settings.

Note that in all the above three simulated populations,

,

, and

. MSE and PRE results of all the simulated populations are provided in

Table 1 and

Table 2 with varying sample sizes. PREs are computed with respect to

.

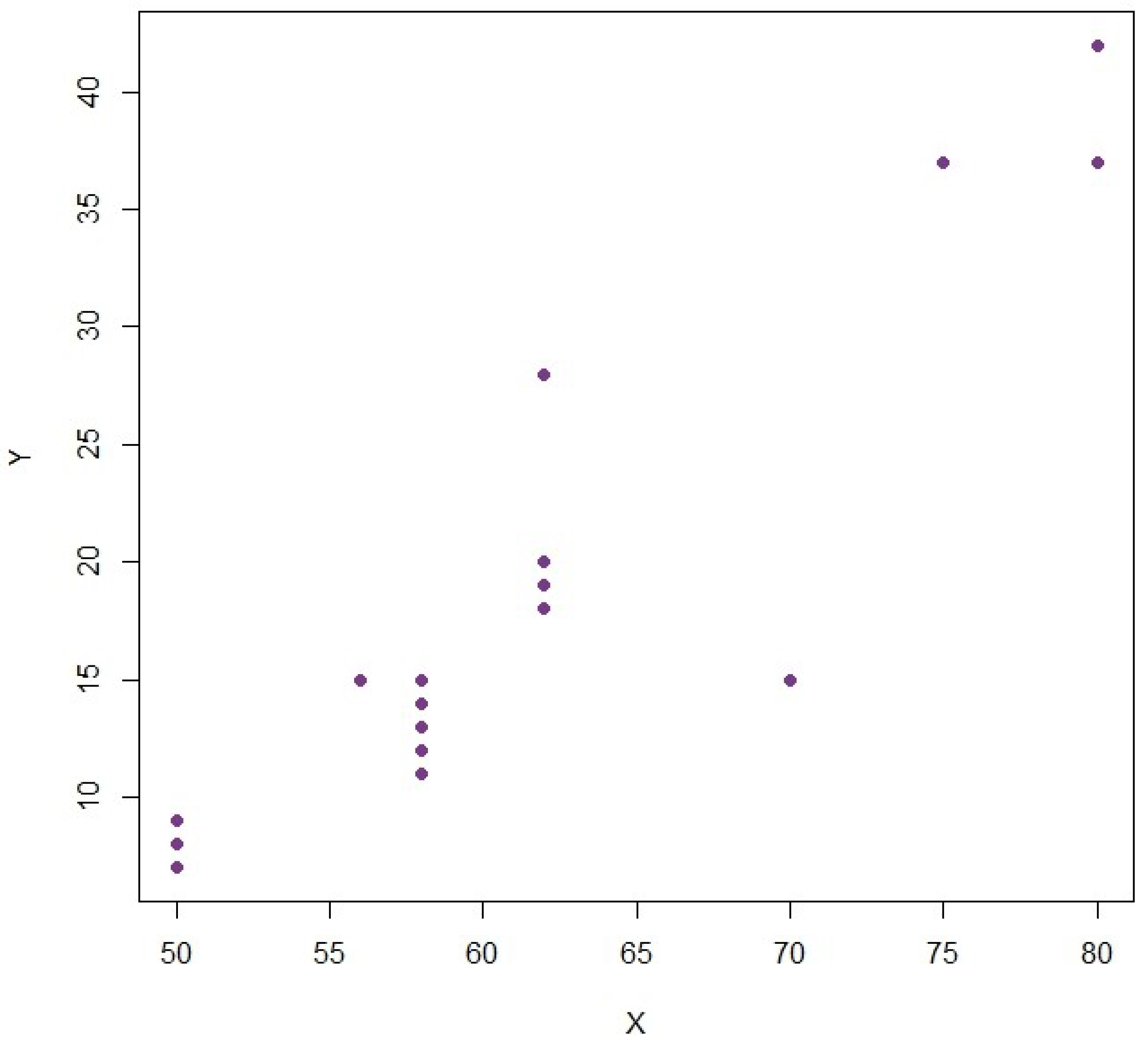

4.4. Real-World Population: Stackloss Plant Data

As a real-world example of our estimators, we use the stackloss dataset, which can be found in R. The data comprise 21 observations from an industrial chemical plant engaged in the oxidation of ammonia to nitric acid. The variable

X, which is referred to as Air-flow, is the frequency of the air flowing to cool the plant, whose values lie approximately between 50 and 80 units. The variable

Y, called stackloss, is a tenfold percentage of ammonia feed, which is not absorbed in the absorption column so

Y is an inverse measure of the efficiency of the plant. This dataset is especially pertinent to the extent that it is known to have moderate non-idealities (skewness residual and possible leverage points in both variables) in it, and therefore it can serve as a practical test ground to examine the robustness of mean estimation techniques in the presence of moderate non-idealities and a realistic data structure. Further,

,

, and

. The scatter plot showing anomalies is provided in

Figure 4. MSE and PRE results are provided in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

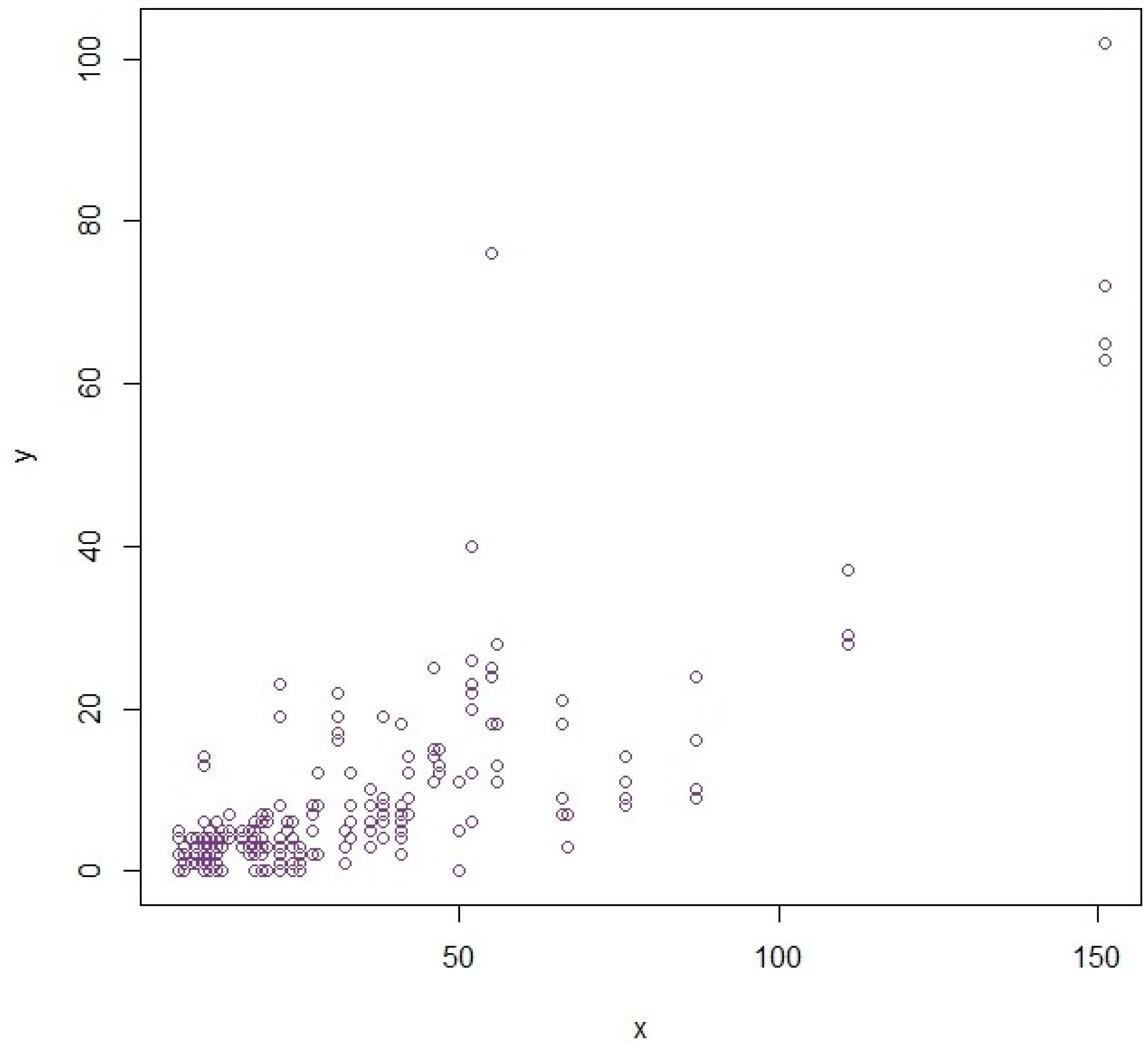

4.5. Real-World Population: Epil Data

We examine a popular dataset of the frequency of epilepsy seizures as another empirical demonstration of the proposed estimators. The dataset is known as epil and it is publicly available via the

MASS package in R. It documents the amount of epileptic seizures the patient experiences during a given monitoring period. In our analysis, Y is the outcome variable, which is the total number of seizures that have been observed in the follow-up period, whereas X is the auxiliary variable, which is the number of seizures that have been experienced before the treatment is administered. Further,

,

, and

. The scatter plots for both real-world populations showing anomalies are provided in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. MSE and PRE results are provided in

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

4.6. Discussion

The detailed outcomes of the artificial and application-based numerical study are presented in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6, which correspond to three distinct missing data scenarios. These tables summarize the relative performance of the traditional and newly suggested estimators at different degrees of contamination. The findings are found to give similar trends in all cases, summarized and discussed as follows.

- Case-I:

Where

Y has missing values and the auxiliary variable is completely observed:

- Case-II:

When there are missing observations in both (or both) variables, but the mean of

X is known:

- Case-III:

Where both variables have partial missingness and the mean of

X is not known:

According to the numerical data results of all three scenarios, the following are the main findings:

Table 1 shows the values of MSE of different estimators used on three simulated populations (SP-1, SP-2, and SP-3) with different sample sizes (4, 8, and 12%). There is a definite trend, as the proposed MRCD-based estimators (

,

, and

) are always lower in the calculation of the MSE results, contrasted to the traditional and M-type ratio-based estimators (

,

,

,

,

, and

). It is interesting to observe that the larger the percentage of missing data, the lower the values of the MSE of all estimators, which indicates a higher level of relative stability of the suggested approaches in more demanding conditions. These findings strongly support the view that suggests that the MRCD-based methods are less sensitive to missing data and outliers; hence, such methods are more appropriate for the practical estimation process in real-life contexts where irregularities in data are widespread.

The PRE of the same estimators of the three simulated populations with different levels of sample sizes and missingness is reported in

Table 2. The PRE values are used to give a relative estimate of the performance of estimators against various sample sizes. The PRE results of the new MRCD-based estimators, especially

, are extremely large (e.g., more than 1900, with SP-1 at 4%), indicating high relative efficiency with less contaminated data. However, these inflated PRE values can also be caused by more missingness. Conversely, the current OLS-based and M-type estimators have low PRE values, usually with values between 100 and 150, which implies low resistance to the effects of outliers and non-normality. Moreover, the fact that the PRE of the MRCD-based proposed estimators increases gradually with a higher degree of missingness indicates their versatility and usefulness on incomplete data. In general, the PRE analysis supports the enhanced effectiveness of the new estimators, as the estimators demonstrate a strong level of robustness and stability in work under various conditions of data.

According to

Table 3, MSE values of nine estimators on the real-world stackloss plant data are reported. The proposed MRCD-based estimators have the lowest MSE (2.3529), with

indicating high accuracy in calculating the population average. It is closely preceded by

with an MSE of (3.7248), and

has a slightly greater MSE of (4.3127). However, the performance of the existing estimators is varied. It is remarkable that

’s MSE (4.6597) is much lower than the MSE values of (11.3628) and (11.0766), the MSE of

and

, respectively. This observation demonstrates that the MRCD-based estimators

are competitive in comparison with (

,

,

,

,

, and

) when there are complex data conditions. The findings also suggest that the performance of estimators may be data-dependent and that, therefore, they should be carefully selected depending on structural features like the existence of anomalies and variation structure.

Table 4 describes the PRE values of the same estimators as

Table 3. The PRE outcomes validate the optimality of

(maximum PRE of 889.91), followed by

(562.15) and

(485.51). These values are consistent with their respective low MSEs that once again confirm their high empirical performance. Again, the best of the existing estimators is clearly

(PRE = (449.35)), which is better than two other estimators, namely,

(184.27) and

(189.04). This also shows the strength and real-world efficiency of

in the OLS-based framework. However, the consistently lower PREs of OLS-based and M-type estimators compared to MRCD-based estimators on this dataset suggests that MRCD methods are designed for robustness; their full advantages are more evident in highly skewed or outlier-contaminated datasets like the stackloss example considered in the current article. Further, a similar type of result behavior can be found in

Table 5 and

Table 6 for epil data.

The proposed MRCD-based estimators do not suffer numerically in the stackloss real-life example, though the data are relatively small, since the MRCD CovMrcd algorithm uses deterministic initialization and regularization to ensure that the scatter matrix is positive-definite. This guarantees that despite the small sample size, the resulting robust location–scatter estimates will be well-conditioned and can be used in the proposed imputation estimators.

These results clearly prove the optimality of the proposed estimator class at different levels of contamination and missingness. Their empirical performance gives them strong rationale to be applied in the real-world setting where data is imperfect.

The large PRE values measured in both simulation and the real data applications show significant efficiency gains of the proposed MRCD-based estimators as compared to the classical and M-type estimators. Practically, a large PRE implies that the suggested estimator will reach an equivalent estimation precision with a much smaller effective sample size, which immediately leads to an increased level of reliability of mean estimates in situations where data either has outliers or missing values or is highly heterogeneous. Indicatively, in real-world data that is contaminated like in the stackloss and epil applications, high PRE values indicate the better capability of the estimator to extract stable information using distorted or partially observed data, resulting in more reliable summaries to make decisions.

Even though MRCD is computationally intensive when compared to OLS and classical M-type estimators because of its repetitive C-step refinements and subset search mechanism, its complexity is still feasible with common survey sampling sample sizes. In a way, modern applications (e.g., using CovMrcd in the rrcov package) use deterministic initialization and effective concentration algorithms, where strong scatter estimation can be obtained in milliseconds to seconds on moderately dimensional problems. Hence, the computational cost increment is small as compared to the significant improvements in stability and performance exhibited in the empirical findings.

5. Conclusions

This paper suggests a powerful statistical method of estimating the mean when both outliers and missing data are present through the use of the MRCD method. In contrast to the classic imputation-based approaches, which are extremely sensitive to contamination of data and non-normality, the MRCD-based estimators proposed in this paper are highly resistant to these irregularities. We introduce three new estimators,

,

, and

, each of which is specific to different patterns of missingness and auxiliary information availability. Their mathematical basis uses logarithmic transformations, which provide greater flexibility and strength. Three different synthetic populations with varying distributional structures and contamination levels, and actual stackloss data, were used to conduct a comprehensive performance of the estimators.The estimates indicate that the new estimators are consistently more robust than the standard ratio-type OLS regression and M-type estimators (

,

,

,

,

, and

) in a variety of situations. In the case of a known population value of the auxiliary variable,

was the most efficient and accurate estimator in terms of the maximum PRE and minimum MSE. The obtained results, therefore, affirm the applicability and the relevance of MRCD in practical situations, especially in scenarios where the data is lost or biased due to the presence of outliers. This methodology can be used in sampling surveys, tracking industries, and also in the analysis of environmental data because of its high performance. Research can be performed in the future on how it can be expanded to larger sampling schemes, such as stratified or systematic sampling, and how it can be used in high-dimensional and dual-auxiliary inputs [

31].