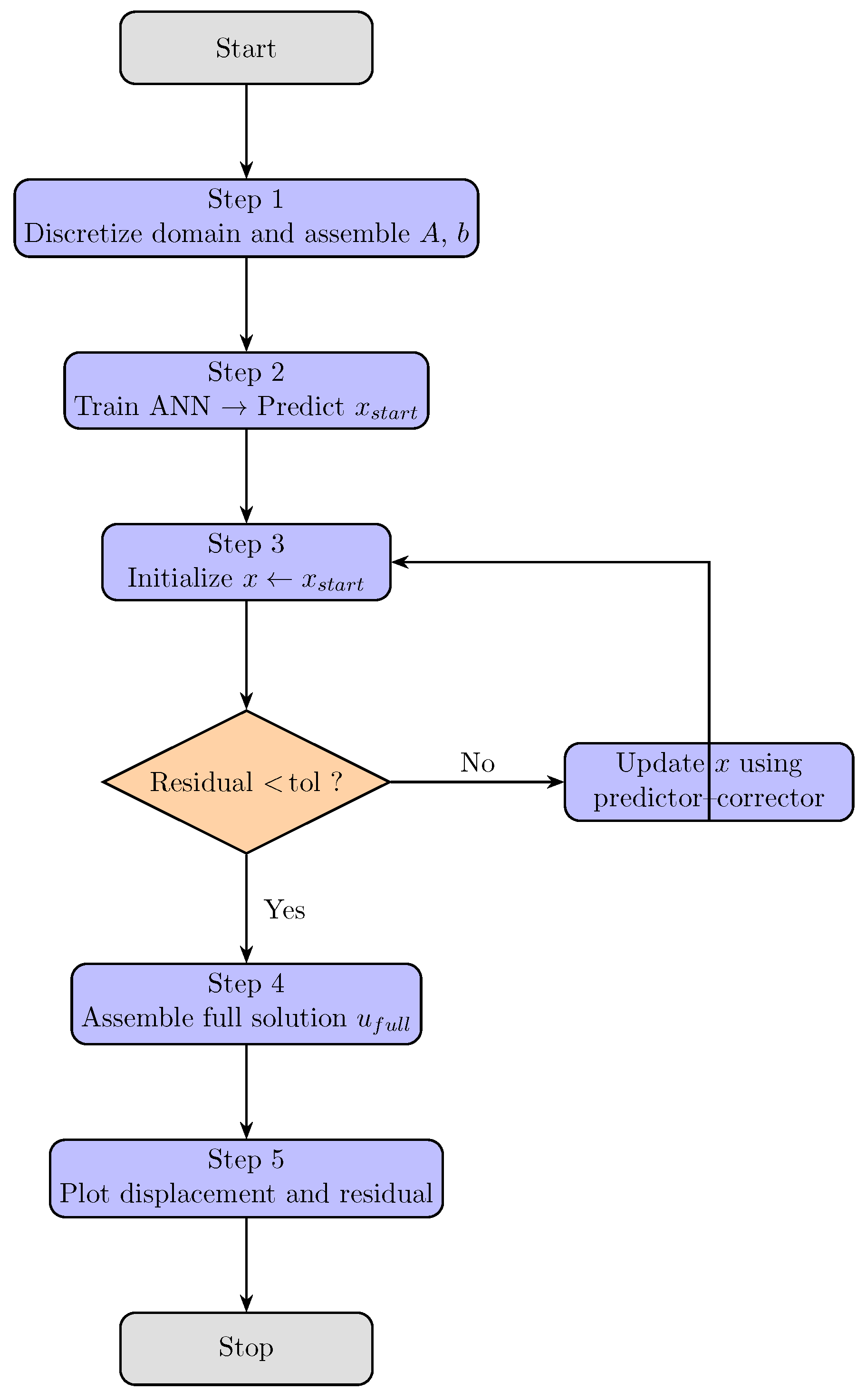

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the hybrid ANN-based numerical solver (SMV–AN) for AVEs.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the hybrid ANN-based numerical solver (SMV–AN) for AVEs.

Figure 2.

ANN-based framework for solving the discretized absolute boundary value problem. The input layer encodes the discretized grid points, and the ANN hidden layers (32–64–32 neurons with ReLU activations) produce an initial approximation . This estimate is subsequently refined by a two-step iterative nonlinear solver (e.g., implemented in MATLAB), yielding a final solution with accuracy up to .

Figure 2.

ANN-based framework for solving the discretized absolute boundary value problem. The input layer encodes the discretized grid points, and the ANN hidden layers (32–64–32 neurons with ReLU activations) produce an initial approximation . This estimate is subsequently refined by a two-step iterative nonlinear solver (e.g., implemented in MATLAB), yielding a final solution with accuracy up to .

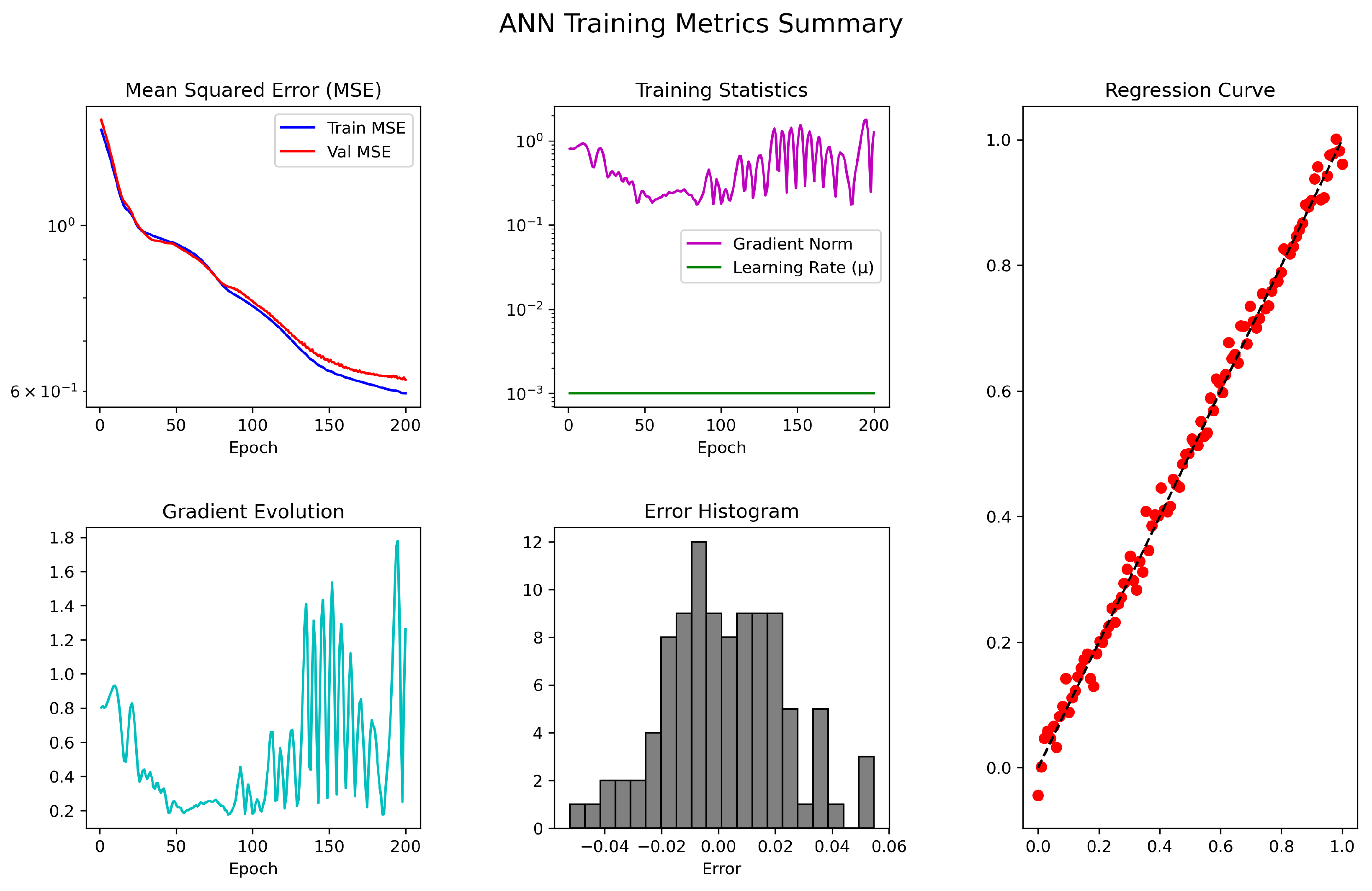

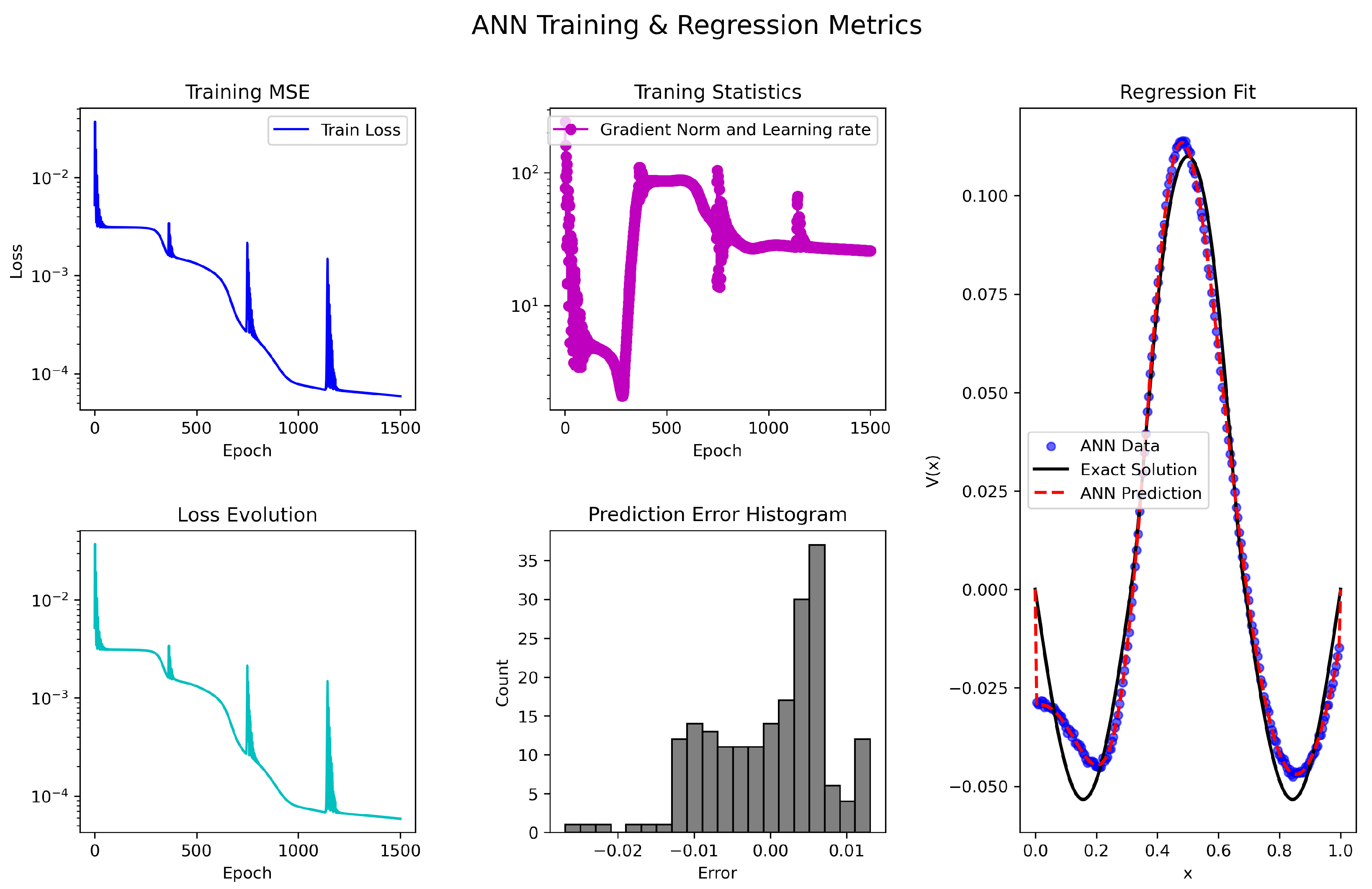

Figure 3.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

37).

Figure 3.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

37).

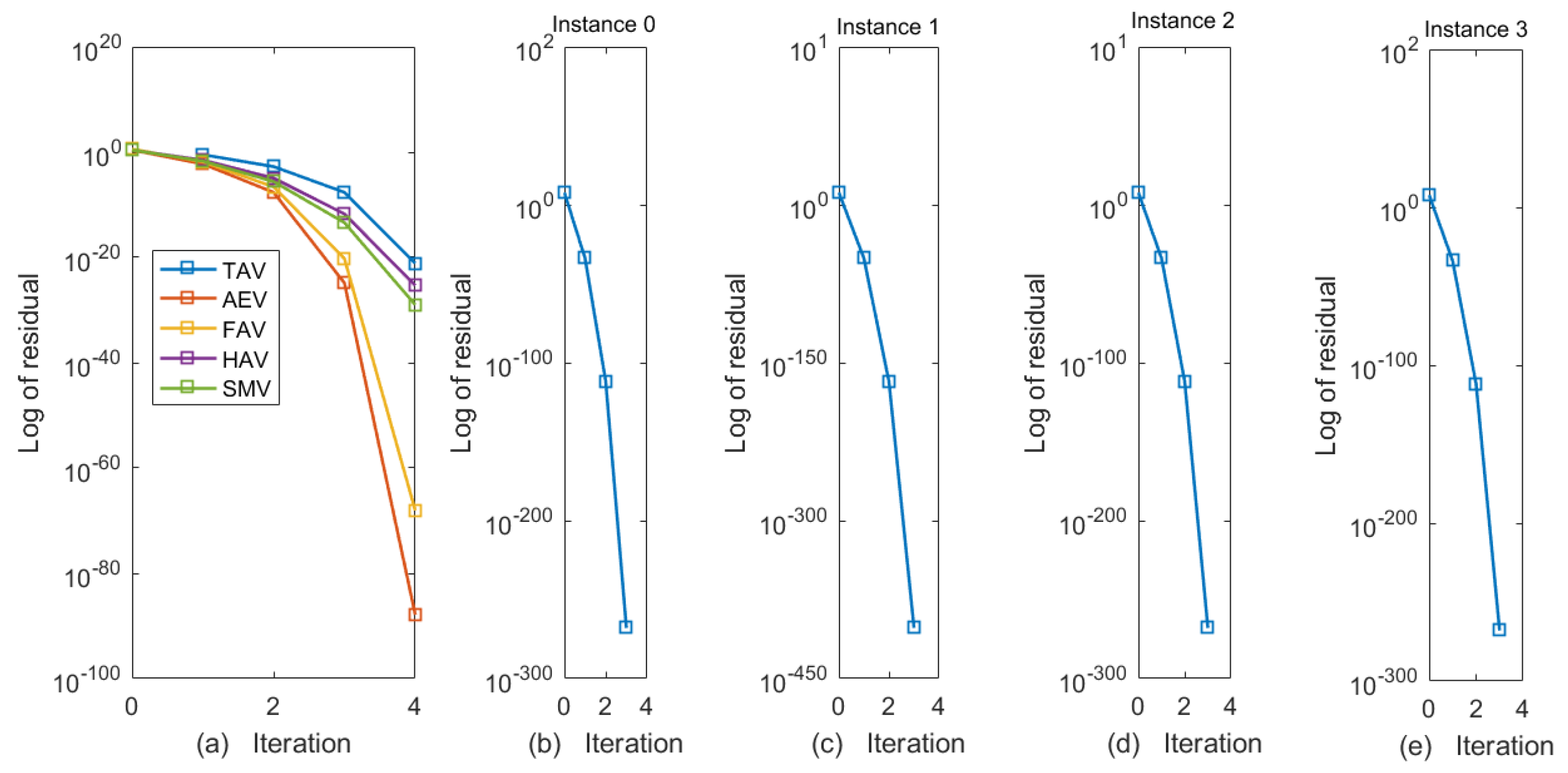

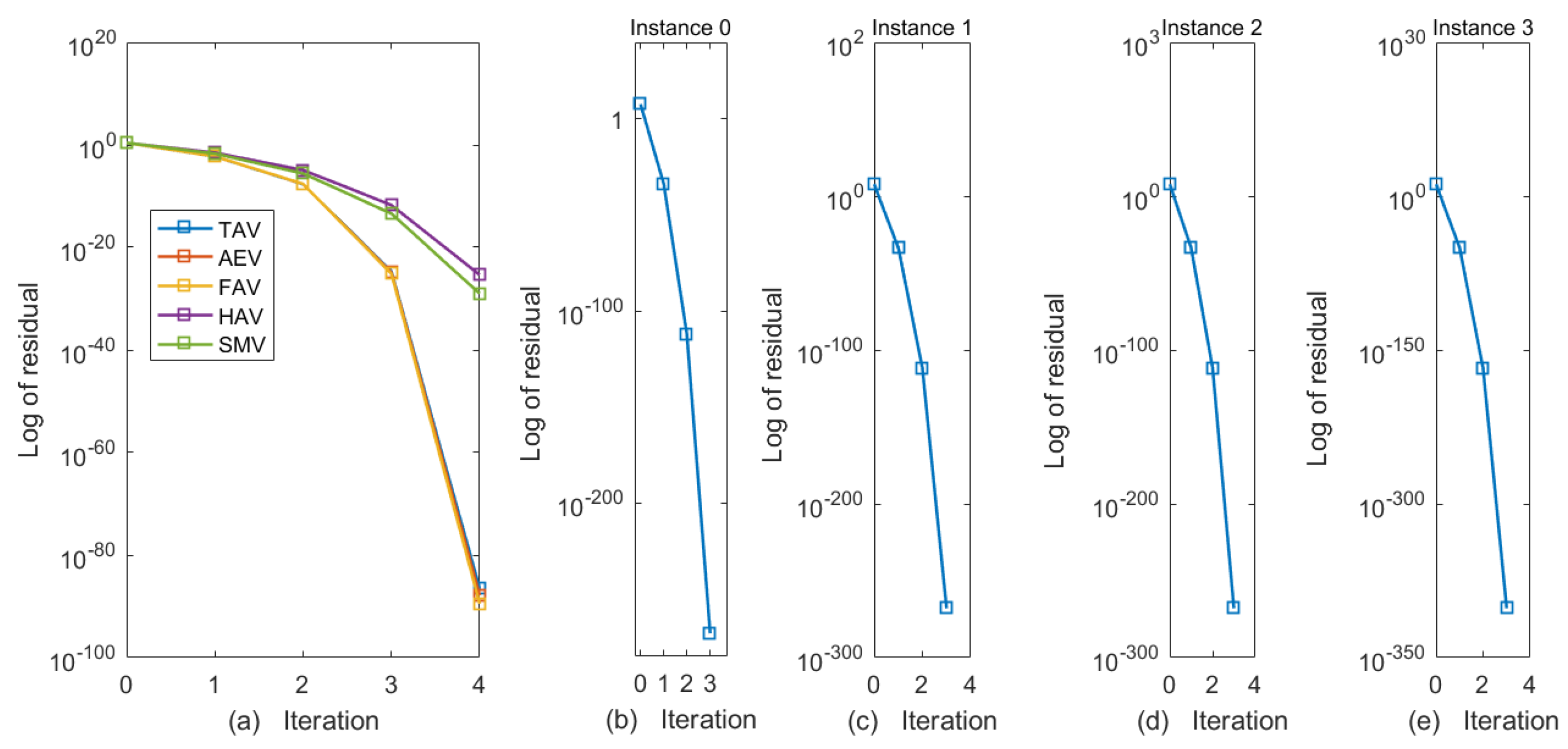

Figure 4.

(a–e) Residual norm comparison of classical vs. proposed schemes (a) and SMV-ANN performance over Instants 0–3 (b–e) for AVEs in Example 1.

Figure 4.

(a–e) Residual norm comparison of classical vs. proposed schemes (a) and SMV-ANN performance over Instants 0–3 (b–e) for AVEs in Example 1.

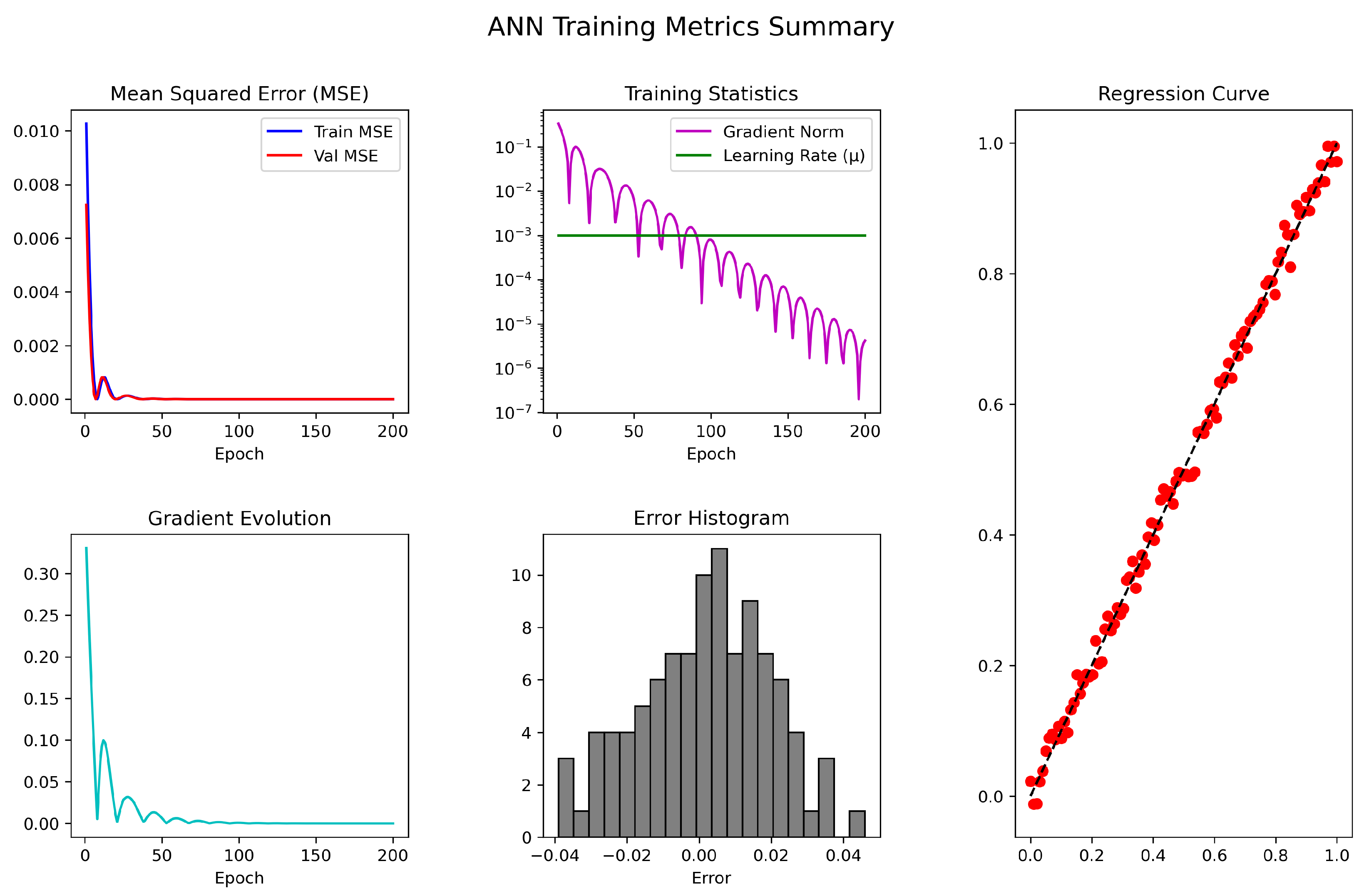

Figure 5.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

38).

Figure 5.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

38).

Figure 7.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

39).

Figure 7.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

39).

Figure 8.

(a–e) Residual norm comparison of classical vs. proposed schemes (a) and SMV-ANN performance over Instants 0–3 (b–e) for AVEs in Example 3.

Figure 8.

(a–e) Residual norm comparison of classical vs. proposed schemes (a) and SMV-ANN performance over Instants 0–3 (b–e) for AVEs in Example 3.

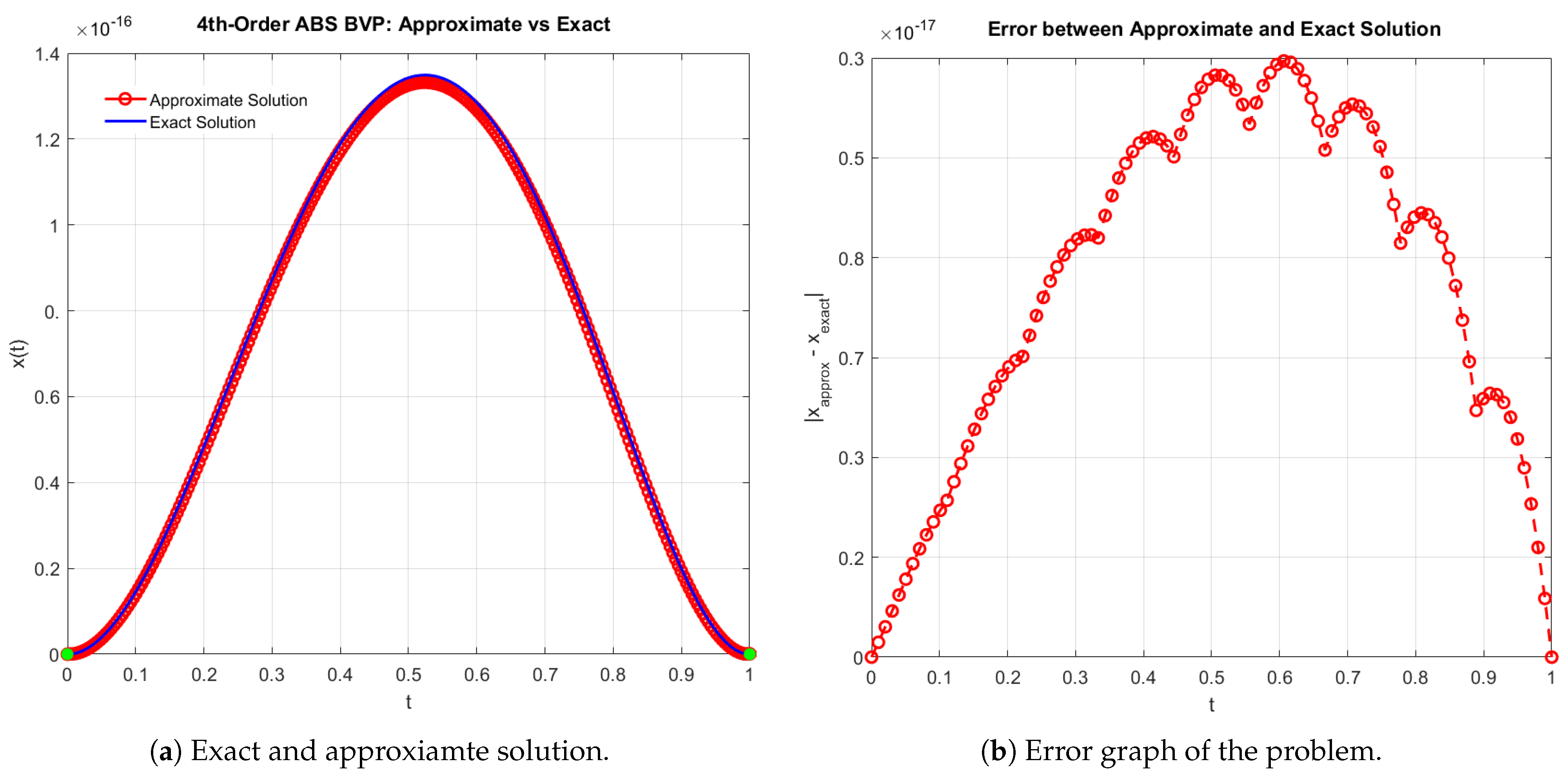

Figure 9.

(a,b) Comparison of exact and approximate solutions for the ABVP in Example 4.

Figure 9.

(a,b) Comparison of exact and approximate solutions for the ABVP in Example 4.

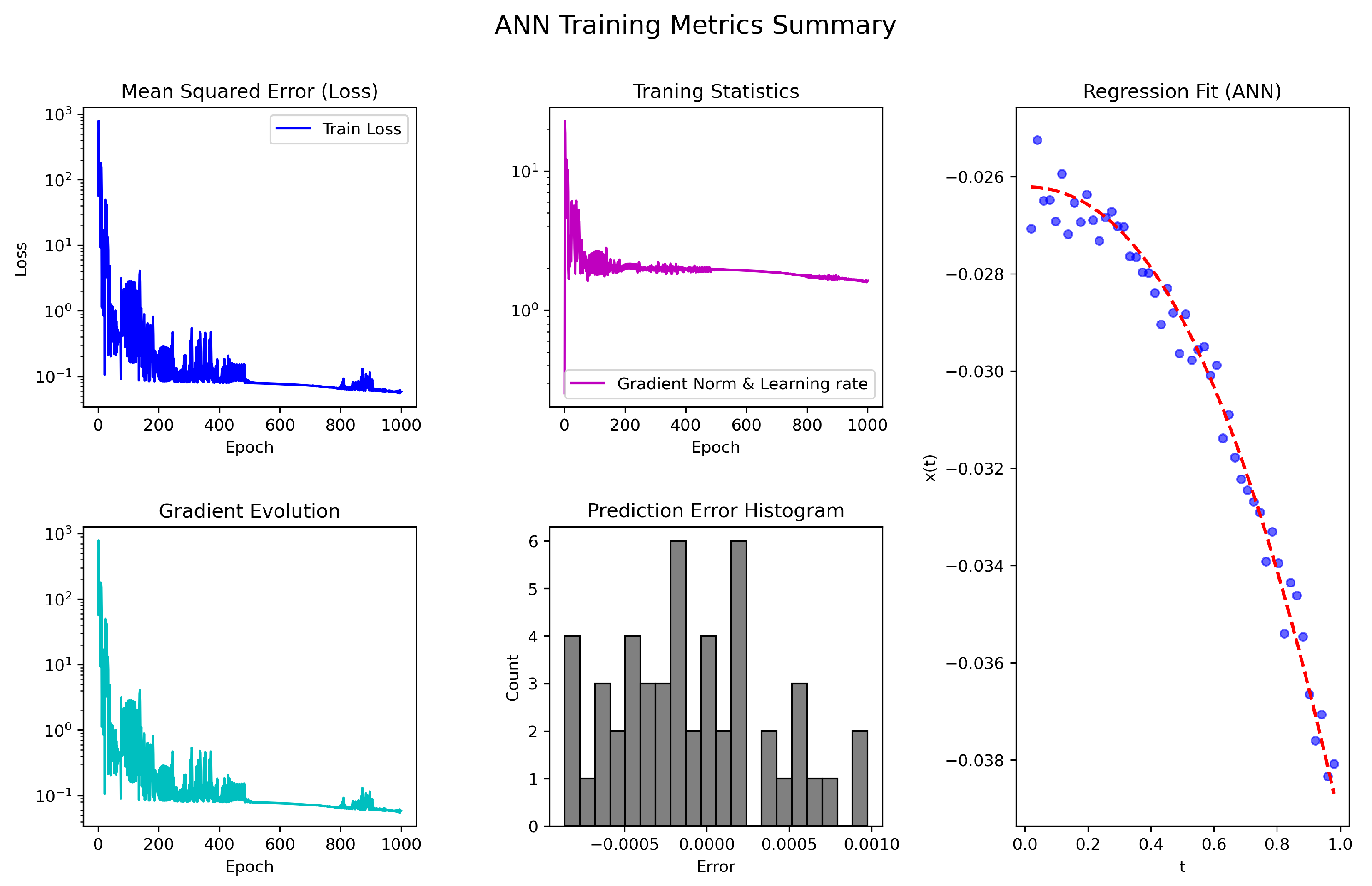

Figure 10.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

44).

Figure 10.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

44).

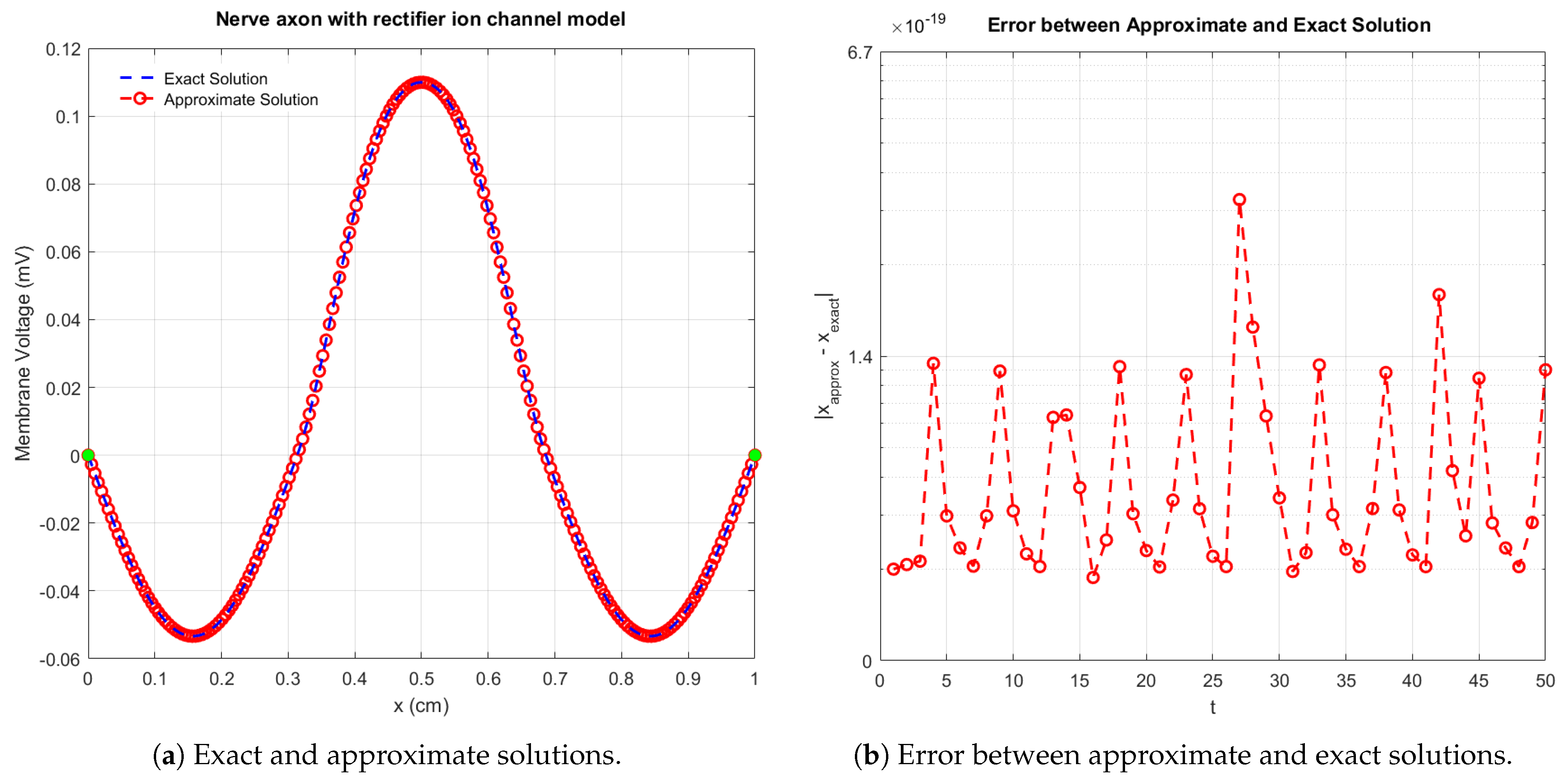

Figure 11.

Comparison of exact and approximate solutions for the ABVP in Example 5.

Figure 11.

Comparison of exact and approximate solutions for the ABVP in Example 5.

Figure 12.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

47).

Figure 12.

The ANN-based SMV-AN scheme’s training performance, MSE, gradient evolution, error histogram, and regression accuracy for solving (

47).

Table 1.

Comparison of iterative approximations and residual errors for the schemes TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, and SMV applied to in Example 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of iterative approximations and residual errors for the schemes TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, and SMV applied to in Example 1.

| Scheme | | | | | Residual Error |

|---|

| TAV | | | | | |

| AEV | | | | | |

| FAV | | | | | |

| HAV | | | | | 1.25 × 10−1

0.76 × 10−7

0.35 × 10−19 † |

| SMV | | | | | 1.29 × 10−4

0.08 × 10−18 †

0.10 × 10−27 † |

Table 2.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (SMV-AN) applied to Example 1, reporting iterations, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive parameter .

Table 2.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (SMV-AN) applied to Example 1, reporting iterations, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive parameter .

| Scheme | Epoch | MSE | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) | Gradient | |

|---|

| SMV-AN | 200 | | 3.4354 | 23,048 | | |

Table 3.

Performance evaluation of SMV-AN for Instants 0–3 in Example 1.

Table 3.

Performance evaluation of SMV-AN for Instants 0–3 in Example 1.

| Scheme | Instant 0 | Instant 1 | Instant 2 | Instant 3 | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) |

|---|

| SMV-AN | † | † | † | † | | |

Table 4.

Performance comparison of iterative schemes (TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, SMV) applied to Example 2, reporting iteration count (It), maximum error (Max-E), CPU time, memory usage, function evaluations (Func-E), and LU factorizations.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of iterative schemes (TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, SMV) applied to Example 2, reporting iteration count (It), maximum error (Max-E), CPU time, memory usage, function evaluations (Func-E), and LU factorizations.

| Scheme | It | Max-E | CPU-Time | Memory (Kb) | Func-E | LU |

|---|

| TAV | 16 | † | 13.3001 | 22,765 | 41 | 23 |

| AEV | 16 | † | 12.0556 | 26,547 | 37 | 21 |

| FAV | 16 | † | 16.1876 | 35,476 | 45 | 27 |

| HAV | 16 | † | 13.0012 | 19,557 | 37 | 17 |

| SMV | 16 | † | 8.1554 | 15,143 | 30 | 13 |

Table 5.

Randomly generated initial vectors used for ANN training (70%) and testing/validation (30%) in Example 2.

Table 5.

Randomly generated initial vectors used for ANN training (70%) and testing/validation (30%) in Example 2.

| | | | | | | | | | | ⋯ | |

|---|

| 0.202 | 0.7675 | 0.2435 | 0.3048 | 0.6550 | 0.1098 | 0.1098 | 0.5002 | 0.9283 | 0.1828 | ⋯ | 0.4798 |

| 0.193 | 0.8266 | 0.3464 | 0.2567 | 0.3978 | 0.3660 | 0.3853 | 0.7587 | 0.6200 | 0.3246 | ⋯ | 0.1391 |

| 0.520 | 0.8566 | 0.7853 | 0.3323 | 0.4000 | 0.1320 | 0.4774 | 0.3528 | 0.2641 | 0.7817 | ⋯ | 0.2772 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋯ | ⋮ |

Table 6.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (SMV-AN) applied to Example 2, reporting iterations, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive parameter .

Table 6.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (SMV-AN) applied to Example 2, reporting iterations, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive parameter .

| Scheme | Epoch | MSE | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) | Gradient | |

|---|

| SMV-AN | 200 | | 2.1903 | 24,197 | | |

Table 7.

Numerical outcomes of the hybride scheme SMV-AN for various instant 0–3 for solving AVE used in Example 2.

Table 7.

Numerical outcomes of the hybride scheme SMV-AN for various instant 0–3 for solving AVE used in Example 2.

| Scheme | Instant 0 | Instant 1 | Instant 2 | Instant 3 | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) |

|---|

| SMV-AN | † | † | † | † | | |

Table 8.

Performance comparison of iterative schemes (TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, SMV) applied to Example 3, reporting iteration count (It), maximum error (Max-E), CPU time, memory usage, function evaluations (Func-E), and LU factorizations.

Table 8.

Performance comparison of iterative schemes (TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, SMV) applied to Example 3, reporting iteration count (It), maximum error (Max-E), CPU time, memory usage, function evaluations (Func-E), and LU factorizations.

| Scheme | It | Max-E | CPU-Time | Memory (Kb) | Func-E | LU |

|---|

| TAV | 16 | † | 12.4354 | 21,018 | 40 | 21 |

| AEV | 16 | † | 11.3464 | 25,675 | 35 | 19 |

| FAV | 16 | † | 15.7853 | 33,234 | 40 | 20 |

| HAV | 16 | † | 14.3436 | 19,875 | 39 | 19 |

| SMV | 16 | † | 7.4426 | 16,030 | 32 | 16 |

Table 9.

Randomly generated initial vectors used for ANN training (70%) and testing/validation (30%) for the strongly nonsmooth AVE in Example 3.

Table 9.

Randomly generated initial vectors used for ANN training (70%) and testing/validation (30%) for the strongly nonsmooth AVE in Example 3.

| | | | | | | | | | | ⋯ | |

|---|

| 1.02 | −0.55 | 0.98 | 1.05 | −1.12 | 0.49 | −0.47 | 1.15 | −0.62 | 0.85 | ⋯ | 0.33 |

| −0.88 | 1.11 | −0.53 | 0.75 | 1.09 | −0.67 | 0.91 | −1.03 | 0.44 | 0.67 | ⋯ | −0.28 |

| 0.45 | −0.97 | 1.08 | −0.88 | 0.72 | −1.15 | 1.02 | 0.56 | −0.49 | 1.14 | ⋯ | 0.41 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋯ | ⋮ |

Table 10.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (denoted SMV-AN) for Example 3, reporting iteration count, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive learning parameter .

Table 10.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (denoted SMV-AN) for Example 3, reporting iteration count, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive learning parameter .

| Scheme | Epoch | MSE | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) | Gradient | |

|---|

| SMV-AN | 200 | | 2.1003 | 22,147 | | |

Table 11.

Error profile of the SMV-AN method for solving AVE at different iterations (Example 3).

Table 11.

Error profile of the SMV-AN method for solving AVE at different iterations (Example 3).

| Scheme | Instant 0 | Instant 1 | Instant 2 | Instant 3 | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) |

|---|

| SMV-AN | † | † | † | † | | |

Table 12.

Performance comparison of iterative schemes (TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, SMV) for Example 4, evaluated across different discretization levels (D). Metrics include iteration count (It), computational time (C-Time), memory usage (Mem), and maximum error (Max-Err).

Table 12.

Performance comparison of iterative schemes (TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, SMV) for Example 4, evaluated across different discretization levels (D). Metrics include iteration count (It), computational time (C-Time), memory usage (Mem), and maximum error (Max-Err).

| Scheme | D | 32 | 64 | 256 | 1024 | 4096 |

|---|

| TAV | | | | | | |

| AEV | | | | | | |

| FAV | | | | | | |

| HAV | | | | | | |

| SMV | | | | | | |

Table 13.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (denoted SMV-AN) for Example 4, reporting iteration count, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive learning parameter .

Table 13.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (denoted SMV-AN) for Example 4, reporting iteration count, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive learning parameter .

| Scheme | Epoch | MSE | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) | Gradient | |

|---|

| SMV-AN | 1000 | | 3.4354 | 24,129 | | |

Table 14.

Computational performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (SMV-AN) for Example 4, evaluated across different discretization levels (D). Metrics include iteration count (It), computational time (C-Time), memory usage (Mem), and maximum error (Max-Err).

Table 14.

Computational performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (SMV-AN) for Example 4, evaluated across different discretization levels (D). Metrics include iteration count (It), computational time (C-Time), memory usage (Mem), and maximum error (Max-Err).

| Scheme | D | 32 | 64 | 256 | 1024 | 4096 |

|---|

| SMV-AN | | | | | | |

Table 15.

Comparison of residual decay of SMV-AN for instants 0–3 (Example 4).

Table 15.

Comparison of residual decay of SMV-AN for instants 0–3 (Example 4).

| Scheme | Instant 0 | Instant 1 | Instant 2 | Instant 3 | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) |

|---|

| SMV-AN | † | † | † | † | | |

Table 16.

Computational performance of different iterative methods (TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, SMV) for Example 5, evaluated across various discretization levels (D). Metrics include iteration count (It), computational time (C-Time), memory usage (Mem), and maximum error (Max-Err).

Table 16.

Computational performance of different iterative methods (TAV, AEV, FAV, HAV, SMV) for Example 5, evaluated across various discretization levels (D). Metrics include iteration count (It), computational time (C-Time), memory usage (Mem), and maximum error (Max-Err).

| Scheme | D | 32 | 64 | 256 | 1024 | 4096 |

|---|

| TAV | | | | | | |

| AEV | | | | | | |

| FAV | | | | | | |

| HAV | | | | | | |

| SMV | | | | | | |

Table 17.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (denoted SMV-AN) for Example 5, reporting iteration count, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive learning parameter .

Table 17.

Performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (denoted SMV-AN) for Example 5, reporting iteration count, mean squared error (MSE), CPU time, memory usage, gradient magnitude, and adaptive learning parameter .

| Scheme | Epoch | MSE | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) | Gradient | |

|---|

| SMV-AN | 1500 | | 2.0176 | 23,849 | | |

Table 18.

Computational performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (SMV-AN) for the ABVP in Example 5, evaluated across different discretization levels (D). Metrics include iteration count (It), computational time (CPU Time), memory usage (Mem), and maximum error (Max-Err).

Table 18.

Computational performance of the ANN-accelerated SMV scheme (SMV-AN) for the ABVP in Example 5, evaluated across different discretization levels (D). Metrics include iteration count (It), computational time (CPU Time), memory usage (Mem), and maximum error (Max-Err).

| Scheme | D | 32 | 64 | 256 | 1024 | 4096 |

|---|

| SMV-AN | | | | | | |

Table 19.

SMV-AN method precision and performance metrics for AVE (Example 5).

Table 19.

SMV-AN method precision and performance metrics for AVE (Example 5).

| Scheme | Instant 0 | Instant 1 | Instant 2 | Instant 3 | CPU Time | Memory (Kb) |

|---|

| SMV-AN | † | † | † | † | | |