1. Introduction

The adaptive finite element method (AFEM) serves as a powerful and dependable approach for numerically solving partial differential equations, with its origins tracing back to the foundational work reported in [

1]. For a comprehensive discussion, see the books by Ainsworth [

2], Babuška [

3], and Verfürth [

4], as well as the review articles reported in [

5,

6], together with their cited references. Recent years have witnessed significant advances in the convergence analysis of AFEMs. The foundational work by Dörfler [

7] introduced a key marking strategy, now widely referred to as Dörfler’s marking strategy, and established strict energy reduction of the adaptive conforming

element method for the Poisson equation under the condition that the initial mesh (

) satisfies a specific fineness assumption. Morin et al. [

8,

9] eliminated initial mesh restrictions by introducing the concepts of data oscillation and the interior node property, establishing the convergence rate of the adaptive conforming

element method. Carstensen and Hoppe [

10] pioneered convergence proofs for the adaptive nonconforming finite element method (ANFEM) and extended results to the mixed finite element method (FEM) [

11]. The field of AFEMs has also seen substantial theoretical developments in quasi-optimality analyses. Binev et al. [

12] first established the complexity of two-dimensional newest-vertex bisection, demonstrating that the cumulative number of elements added to maintain mesh conformity does not excessively increase the total number of marked elements. Leveraging this property, they proved the optimality of the AFEM by incorporating an additional coarsening step. Later, Stevenson [

13] generalized the complexity to three-dimensional newest-vertex bisection and proved coarsening unnecessary for quasi-optimality. The optimal complexity results for adaptive algorithms mentioned above can be understood as follows: if the exact solution can be approximated by a given class of finite element methods at a certain rate (measured as the ratio of accuracy to the number of unknowns), then the sequence of meshes generated by the adaptive algorithm with newest-vertex bisection will achieve this optimal convergence rate, up to a constant multiplicative factor. Cascon et al. advanced the theory by proving the convergence of AFEMs without an interior node property and the quasi-optimality of AFEMs for self-adjoint elliptic problems [

14]. More recently, a convergence and optimality result of the adaptive Wilson element method was obtained in [

15], where the authors used a special property of the Wilson element whose shape function space is composed of two parts (a conforming

part and a nonconforming bubble-function part) orthogonal to each other, i.e., the Wilson element is very close to conforming with the

element. The first quasi-optimality result of the ANFEM for a second-order elliptic problem was obtained by Becker et al. [

16], who considered the nonconforming

element (Crouzeix–Raviart element [

17]) with an adaptive algorithm based on a balance of contributions of two parts in the estimator in each step. Later, Mao et al. established the quasi-optimality of the adaptive Crouzeix–Raviart element method by using a simple Dörfler collective marking strategy in each step, without comparison of the two contributions in the estimator [

18]. The quasi-optimality result of an ANFEM for a fourth-order elliptic problem was obtained by Hu et al. [

19], who considered Morley element in their paper. The quasi-optimality results of the adaptive nonconforming

element method for optimal control problems were studied in [

20,

21]. Convergence and optimality analysis of ANFEMs in all these papers crucially relies on the fact that, for the lowest order nonconforming element, the discrete pressure (or the discrete stress) is a piecewise constant vector (tensor).

This paper will establish the quasi-optimal convergence for a family of adaptive nonconforming finite element methods that preserve weak continuities across elements’ edges, where the corresponding discrete pressure is not a piecewise constant vector. The lowest order case in this family is the Lin–Tobiska–Zhou element [

22]. To the best of my knowledge, it is the first optimal convergence result using an adaptive algorithm with a nonconforming finite element and high-order terms preserving weak continuities. It will be proven that the adaptive algorithm based on this family of nonconforming finite elements on rectangular meshes is convergent by establishing a new quasi-orthogonality. More importantly, it will be proven that the above-mentioned adaptive algorithm possesses optimal complexity, and a new discrete reliability will be proven by establishing a new discrete Helmholtz decomposition for this family of nonconforming elements for the first time. It is noticed that the nonconforming quadrilateral

element [

23] also be seen as a member of the family of nonconforming finite elements considered in this paper. Therefore, the convergence and optimality results presented in this paper are valid for the adaptive nonconforming quadrilateral

element [

23] method applied to general quadrilateral meshes.

This work addresses a gap in prior analyses of adaptive nonconforming methods, which have predominantly relied on the piecewise-constant nature of the discrete stress/pressure field (as in the case of the Crouzeix–Raviart element). New analytical tools are developed, including a novel quasi-orthogonality relation, a discrete reliability bound derived from a novel Helmholtz decomposition tailored to this class of elements, and accompanying technical estimates. These tools are integrated with standard Dörfler marking to establish the convergence and quasi-optimality of the adaptive algorithm for rectangular/quadrilateral meshes.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the preliminaries, including the notations, the problem under consideration, and the definition of a nonconforming element and some of its key properties. In

Section 3, the a posteriori error estimation and the adaptive algorithm will be presented.

Section 4 will prove one main result of this paper, i.e., the convergence of the AFEM algorithm will be proven, and a new quasi-orthogonality will be established in the beginning of

Section 4.

Section 5 will establish a new discrete reliability result and provide an asymptotic estimate for the optimality of the adaptive algorithm, which is the other main result of the paper. Some numerical experiments are presented in

Section 6.

2. Preliminaries and Notations

This section introduces some essential notations. Following standard definitions for Sobolev spaces (cf. [

24]), the seminorm and norm of a function (

v) defined on an open domain (

G) are defined as follows:

Let

be a bounded polygonal domain that is partitioned by a rectangular mesh (

). This paper focuses on the following second-order elliptic problem with discontinuous coefficients: find

such that

where

and

is a positive, piecewise-constant coefficient matrix. Assume that

remains constant on each element of the initial mesh (

).

Let

denote the

inner product, where the subscript

is omitted when

for simplicity. For any

, the variational formulation of the problem (

1) can be expressed as follows:

where

.

Let denote the cardinality of a finite set (J). The meshes considered in this paper are described next. Assume that is a graded adaptive mesh generated through a refinement process as follows: the domain () is initially partitioned into elements () of mesh-level 0, where is conforming, meaning that for any distinct elements (), their intersection () is either empty, a common node, or a common edge. Starting from an element (), an existing element (K) can be refined by splitting it into four new elements, referred to as its sons and denoted by for . The son elements are formed by connecting the midpoints of opposite edges of the original element (K). For a newly created element (), the original element (K) is designated as the father element of , denoted by . When an element (K) undergoes refinement, the domain partition () is updated by replacing K with its four son elements (, ). The new elements can be refined again and again and so the final partition () of is created.

Definition 1. For an element () generated from the initial mesh () by the refinement process described above, the refinement level () is defined as if and if there exists a chain of m father elements (, where , starting from and defined by for ) such that .

The above definition of is equal to the number of refinement steps required to generate element K from an element in the coarsest mesh ().

Definition 2. A mesh () generated by the above refinement process from a regular initial mesh () is called k-irregular (where and ) if the following condition holds for any pair of neighboring elements () sharing a one-dimensional manifold boundary (): Here, and denote the refinement levels of elements K and , respectively.

Note that condition (

3) does not need to hold for element pairs (

K and

) sharing a single vertex. A 0-irregular mesh is conforming (without hanging nodes), whereas this work exclusively examines 1-irregular meshes, which permit hanging nodes. AFEMs on quadrilateral meshes without hanging nodes were presented in [

25]. The corresponding local refinement procedure for 1-irregular meshes is detailed in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Local refinement on 1-irregular quadrilateral meshes. |

| Input: A 1-irregular mesh with a marked elements set (If , is required as a conforming mesh). |

- (1)

For each marked element , subdivide it into 4 smaller elements by connecting the barycenters of its opposite edges (see Figure 1). - (2)

If any pair of neighboring elements violates the 1-irregularity condition (i.e., ( 3) with ), refine the less-refined element by splitting it into 4 sub-elements (as in Step 1). - (3)

Repeat Step 2 until the 1-irregularity condition holds for all neighboring elements in the mesh.

|

| Output: The refined graded adaptive mesh . |

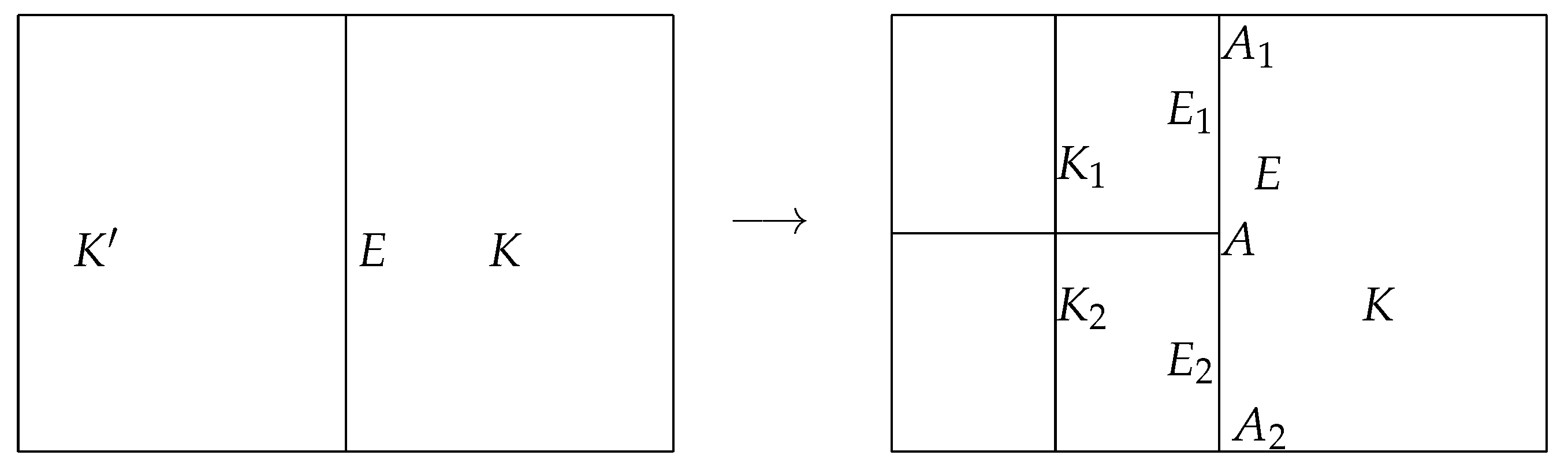

Figure 1.

(Left) Regular interior edge () connecting two associated elements (K and ); (Right) Hanging node A, along with its neighboring regular nodes ( and ) and its irregular interior edge () subdivided into two son edges (), where each son edge corresponds to a single element ( or ).

Figure 1.

(Left) Regular interior edge () connecting two associated elements (K and ); (Right) Hanging node A, along with its neighboring regular nodes ( and ) and its irregular interior edge () subdivided into two son edges (), where each son edge corresponds to a single element ( or ).

The above local bisection refinement result holds for the following complexity result [

26].

Lemma 1. Let be a sequence of quadrilateral meshes generated by Algorithm 1, starting from an initial mesh () with denoting the marked elements refined at step k. Then, is uniformly shape-regular, with its regularity constant depending only on . Furthermore, the total elemental increase satisfies the following:where is a constant determined by . Let

denote the set of four edges of an element (

). Let

be the set of all elements’ edges of the mesh.

can be decomposed as follows:

where

describes the set of all edges located at the boundary (

) of

and

denotes the set of edges of

located in the interior of

. An edge (

) is called a son edge of an edge (

) if

and

(see

Figure 1). The set of all son edges of

E is denoted by

. The set of all irregular interior edges (

) is defined as follows:

Let

be a son edge of

; then, edge

E is termed the father edge of

and is written as

. The set of all son edges is defined as

Let

denote the collection of regular interior edges:

It is easy to see that set

is empty for each regular edge (

). Using these definitions, the set of all interior edges (

) can be decomposed as

Let to be the set of vertices of any element (). The set of all nodes of the mesh () reads . Obviously, son edges appear in pairs. The common vertex of a pair of two son edges is called a hanging node.

A node (

) is defined as a regular node if it does not serve as a hanging node. A representative scenario involving a hanging node (

A) and its connected regular nodes (

) is illustrated in

Figure 1. Specifically, a node (

) is classified as a hanging node if there exists a mesh element (

) such that

A lies on the boundary (

) but is not one of the vertices of

K.

For each element (

) and edge (

), we define

and

. For each edge (

), we define

For each element (

), we define

and

where

is the set of all the neighboring elements of element

. For any

, we define

It is noticed that the shape regularity of rectangular mesh

implies the existence of a constant (

) such that

where

is the diameter along each coordinate axis of element

K. The definition of the shape regularity of general quadrilateral meshes can be found in [

24,

27].

This study focuses on the following family of nonconforming FEMs with some weak continuity at interelement boundaries, which means the corresponding finite element function preserves the continuity of the integral across internal edges of elements.

The corresponding interpolation operator related to degrees of freedom is presented next. For a reference element (

), we define the polynomial space as follows:

The finite element interpolation operator (

) is defined for any

as follows:

and for any boundary (

) of

,

and

For a reference element (

) with four edges (

, and

), the degrees of freedom (DOFs) of function

are defined as

The nonconforming finite element function space (

) defined on mesh

can be given as

where

represents the linear transformation from the standard reference element (

) to the actual rectangular element (

K),

is the jump of

across interior edge

E, and

for any boundary edge (

). Thus, the interpolation operator (

) is followed by the above linear mapping.

Remark 1. The above definition includes a family of nonconforming finite elements. For the low-order case of , the above nonconforming finite element is the Lin–Tobiska–Zhou element [22]. In addition, if one defines in (9), then the quadrilateral/hexahedral nonconforming element [23] is also included in the above nonconforming element family with the case of , and the convergence and optimality results presented in this paper are also valid for this element. Remark 2. If (8) is replaced by a continuity at the center of E, then the other versions of nonconforming finite elements are obtained, which preserve the continuity at centers of interelement boundaries. In addition, it is easy to see that is not well defined based on the weak continuity condition (continuity at the midpoint or continuity of the integral) on four edges of the reference element (). Therefore, nonconforming finite elements that preserve some weak continuity across interelement boundaries usually exclude terms of multiplication between ξ and η. Without any confusion, is also denoted as in this paper.

Obviously, for any irregular edge (

), some additional constraints should be imposed on degrees of freedom of

E and its two son edges in order to keep the integral continuity across

E. One can cite [

27] for more details.

Let

denote the discrete gradient operator and

denote the curl operator. The discrete weak form of (

2) is defined as

where

.

is the following mesh-dependent energy norm:

Obviously, the above mesh-dependent energy norm is equivalent to the mesh-dependent

norm (

), i.e.,

where the above constants (

and

) depend on

.

As rectangular meshes are considered in this paper, it is easy to see that for any , is a constant on any line E, where E is parallel to an axis and is a unit normal of E.

Lemma 2. The following properties hold for the finite element space and the interpolation operator.

- (i)

Operator holds for the following stability: - (ii)

Operator has the following approximation property with a constant (C) dependent only on the shape regularity of the initial mesh such that - (iii)

For any three nested meshes (, , and , where is finer than and is finer than ), the following orthogonal properties hold: - (iv)

For any two nested meshes ( and , where is finer than ), and any , let be the projection of on space related to the energy norm (), there exists a conforming bilinear function () such that

Proof. (i) and (ii) are standard results. The proof is limited to (iii) and (iv). The proof begins with (

16). By integration by parts, for any

and any

, one can obtain

where (

9) and (

8) are used in the last two steps. Similarly, one can verify that (

16) holds for any

and any

, any

and any

, or any

and any

.

(iv) is now proven. Since

is the projection of

on space

, one can see that for any

,

For any interior element edge (

),

denotes the related basis function on

E. Taking

and integrating by parts yields

which means

. Therefore,

. For any element (

),

denotes the related basis function in

K. Taking

and integrating by parts yields

As the above identity holds for basis functions related to DOFs in the interior of

K and noticing that

, it must hold that

, which, together with

, leads to

. Therefore, there exists a function (

q) belonging to

with

such that

. For any

,

with coefficients

. Then, one can obtain

Let and insert it into the above identity. Thus, one can find that when or , which means . Therefore, q is a conforming function. □

Remark 3. It is noticed that (17) actually establishes the discrete Helmholtz decomposition for this family of nonconforming finite elements, i.e.,for any and any , where is a conforming piecewise function related to mesh . In this paper, when a mesh is denoted as , the subscript h is also replaced by k correspondingly, such as , and so on. In addition, for a subset (), the notation of is also adopted.

3. Adaptive Algorithm

This section will present an adaptive nonconforming finite element algorithm. To this end, the reliability and efficiency of the a posteriori error estimation should be established. The following a posteriori error estimator for nonconforming FEMs is presented [

28,

29].

For any

, define the normal jump across an interior edge (

E) as follows:

where

is the unit normal of

E. For any

, define the tangential jump across an interior edge (

E) as follows:

where

is the unit tangential of

E.

For

, define the residual term for

as

where

. For

, define the jump term for

as

The notation of and is adopted for any subset (). For brevity, and are used as shorthand notations.

Lemma 3. Let be the solution of (12) on mesh ; then, it holds thatwhere C is a positive constant dependent only on the mesh’s shape regularity and polynomial degree. Proof. If

, let

to be the nonconforming element basis function on

E. One can see from the definition of

that

. Therefore, direct calculations lead to

Notice that the integral of

on

is zero. By using integration by parts and Cauchy–Schwartz inequality and noticing

is a constant, one can obtain

Combining the above two inequalities yields the final result (

22). If

, then there must exist an element (

K) on one side of

E with

. Meanwhile, there must exist two elements (

and

) on the other side of edge

E with

and

, where

and

are two son edges of

E (see

Figure 1). Let

to be the restriction in

K of the nonconforming element basis function related to

E. Let

to be the restriction in

of the nonconforming element basis function related to

, where

. We define

It is easy to see from the definition of

that

. Therefore, one can similarly obtain (

22). If

, then one can consider the father edge of

E, denoted by

, which belongs to

, and obtain

□

For any

, we define the error estimator for

as

For any given subset (

), we define

For brevity, is set when and . When the mesh is denoted by with an integer of k, the notation of is adopted to represent the error estimator over , while is used to denote the error estimator over the entire mesh ().

Lemma 4 (Global upper bound).

There exists a constant () depending on the shape regularity of the mesh (), the polynomial degree, and such that for the discrete solution () of (12), it holds that Proof. Based on the result of [

29] (see (4.8) in [

29]), one can obtain

which, combined with Lemma 3, leads to (

24). □

The efficiency of the a posteriori error estimator is subsequently provided. For a non-negative integer (

m), let

be the

-best approximation operator on the set of discontinuous polynomials that belong to

over

. For any

, we define the oscillation term as

For rectangular meshes (

), it is easy to see that

over

, which means

However, the above identity is usually incorrect on general quadrilateral meshes, as the term

will not be a polynomial in general. Refer to [

30] for more details. The notation of

is adopted for brevity. If the mesh is denoted by

with an integer of

k,

is also used to stand for the oscillation term over

and

is used to stand for the oscillation term over the entire mesh (

).

Lemma 5 (Lower bound).

There exists a constant () depending on the shape regularity of the mesh , the polynomial degree, and such that the discrete solution () of (12) satisfiesandand The above results can be similarly proven by the arguments in [

2,

4,

30,

31,

32].

The adaptive finite element algorithm based on the aforementioned error estimator is introduced at the end of this section. Moving forward,

is also used to represent a mesh (

) with a non-negative integer (

k). The same applies to other associated quantities.

| Algorithm 2 . |

|

Select a Dörfler marking parameter , choose an initial mesh , and initialize . |

- (1)

Solve the weak formulation as defined in ( 12) over the current mesh and obtain the discrete solution . - (2)

Compute the error estimator for each element . - (3)

Identify a subset of with the smallest possible number of elements that satisfies the condition: - (4)

Apply the local refinement algorithm specified in Algorithm 1 to the marked elements and generate the refined mesh ; - (5)

Set and return to step (1).

|

6. Numerical Examinations

Numerical experiments with the are presented here. In this section, the adaptive Lin–Tobiska–Zhou(LTZ) element method is used in numerical experiments. The number of DOFs in the finest mesh exceeds 10 million in all numerical examples.

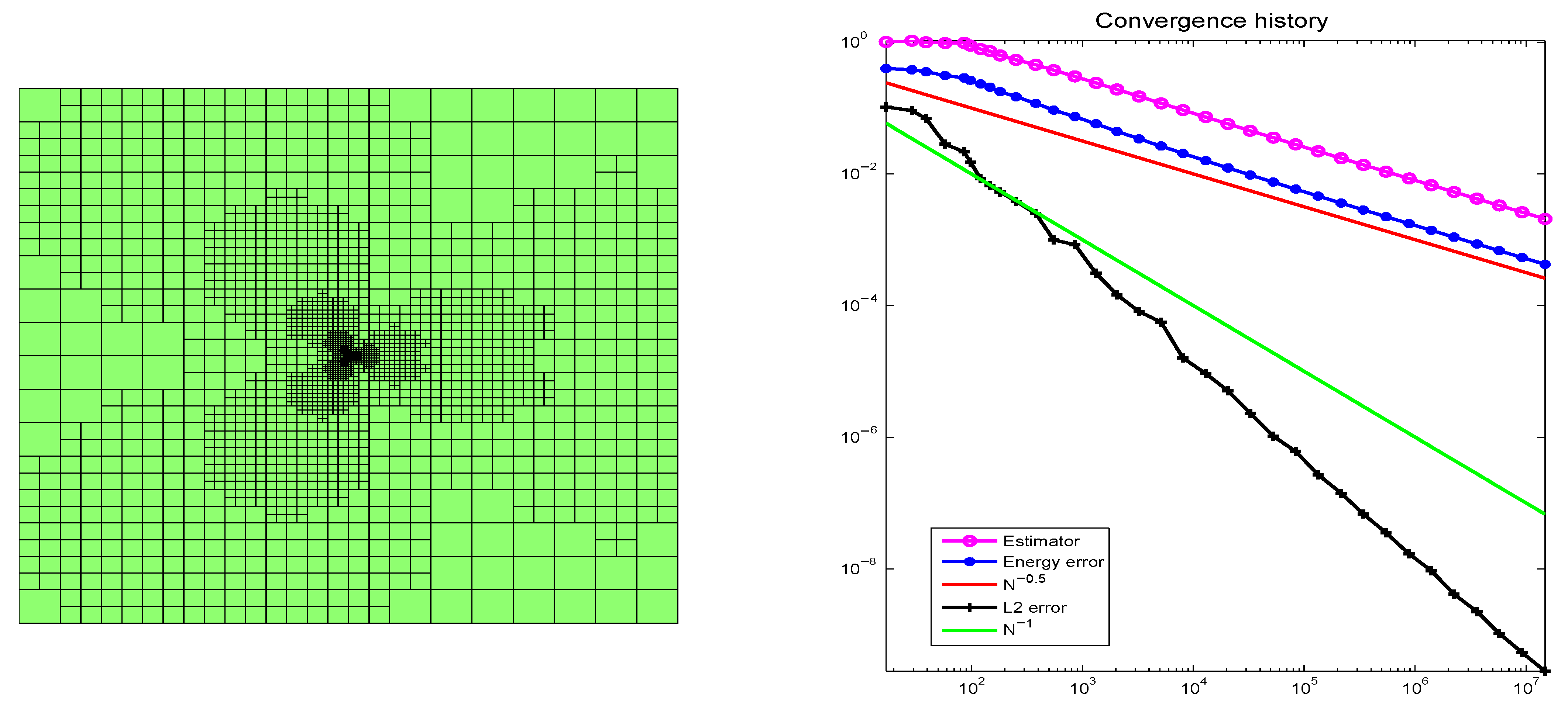

Example 1 (

Crack problem).

The domain (Ω

) is given by . In this domain, the solution (u) adheres to the Poisson equation: By selecting g appropriately, the exact solution u can be expressed in polar coordinates as follows: The two pictures in

Figure 2 are the 17th-level adaptive mesh generated by the LTZ element method and the corresponding convergence history of the

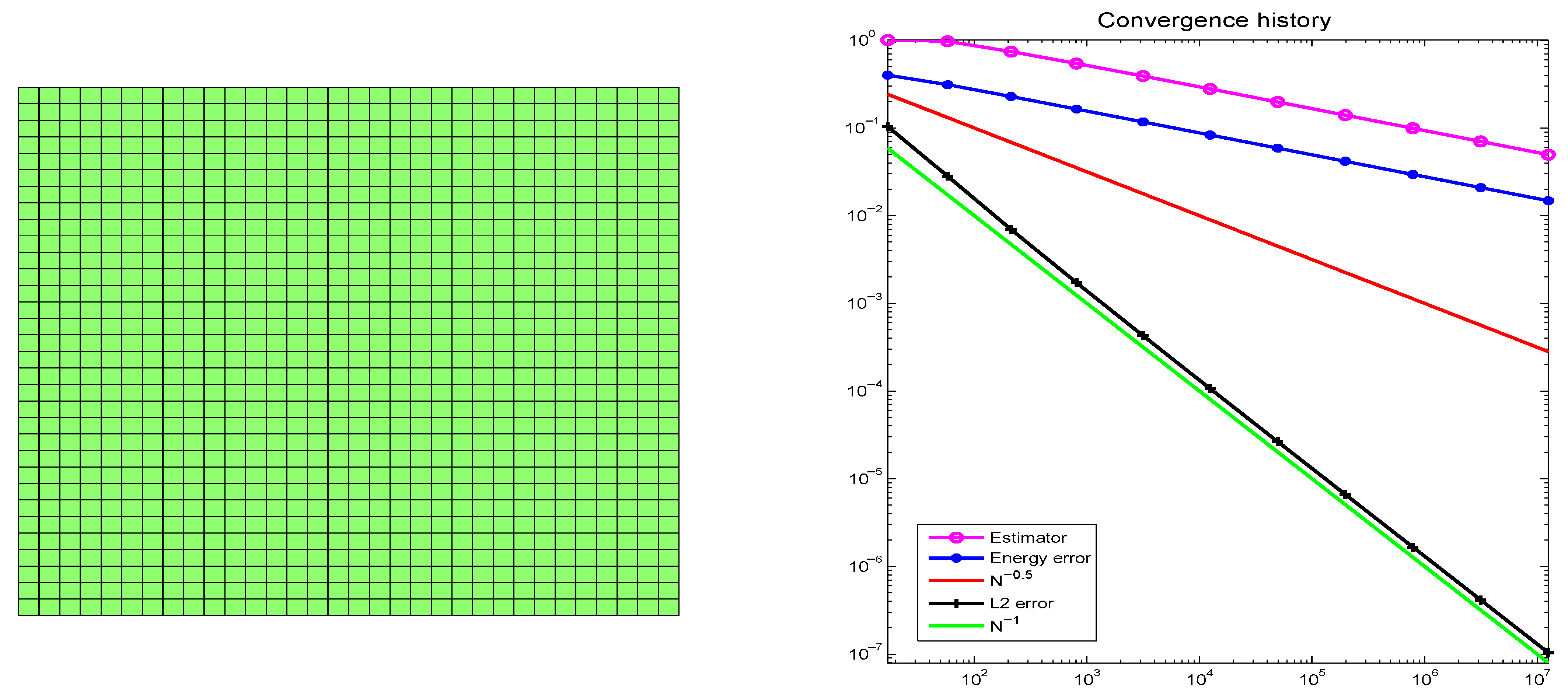

with 14,823,276 DOFs in the final mesh. The two pictures in

Figure 3 are the 4th-level uniform mesh generated by the LTZ element method and the corresponding convergence history with 12,588,032 DOFs in the final mesh. Obviously, the adaptive LTZ element method is optimally convergent, while the LTZ element method with uniform refinement is not.

Example 2 (

Kellogg problem)

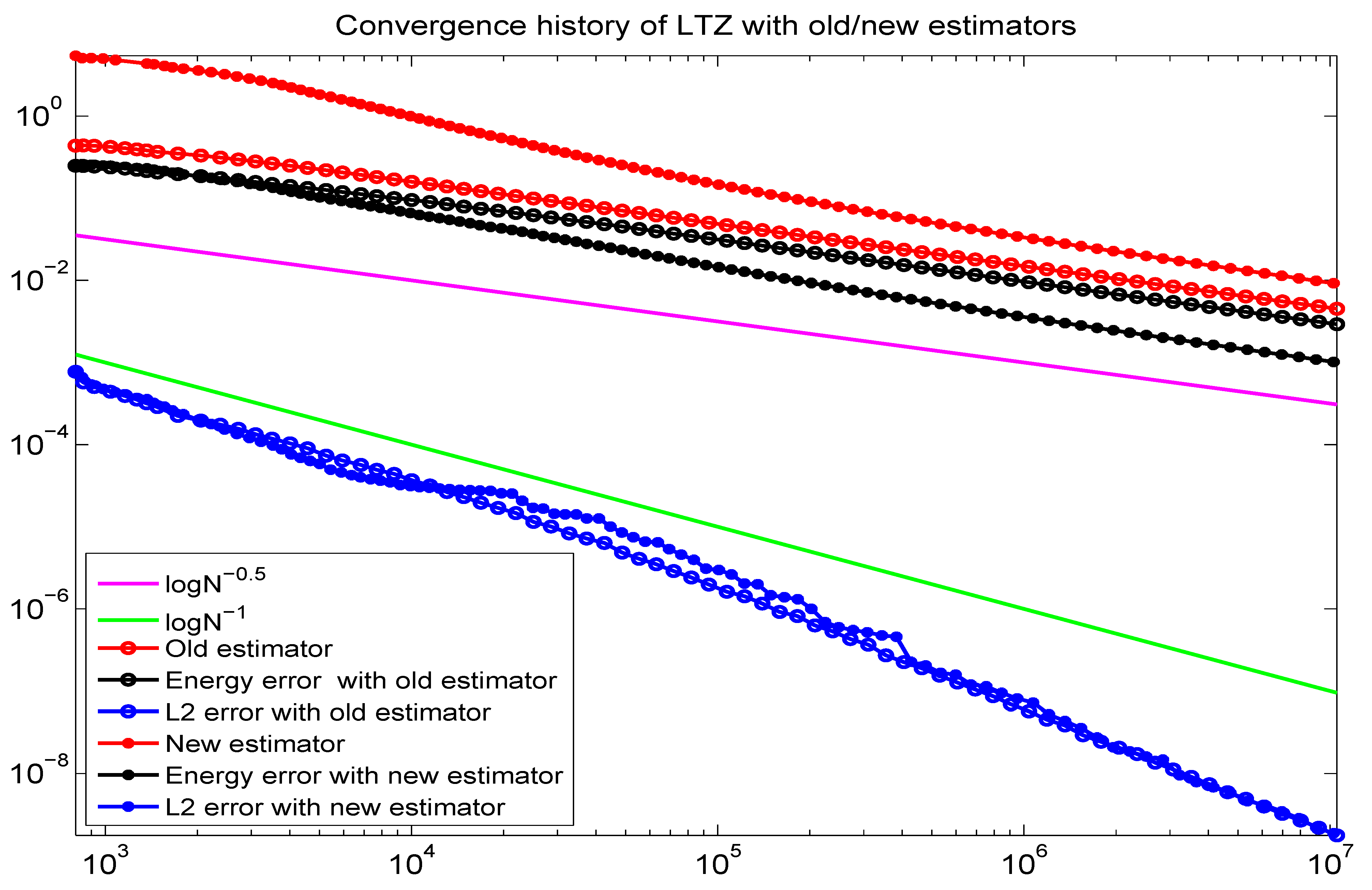

. Consider the following elliptic problem with piecewise constant coefficients and a vanishing right-hand side (f). Let , in the first and third quadrants and in the second and fourth quadrants, where R is a constant to be specified later. The problem is defined as follows: The boundary function () is chosen to match an exact solution (u), which is expressed in polar coordinates as follows: , where The τ, ρ, and σ parameters satisfy the following nonlinear relationships: The solution of u belongs to space with . For , solving the above nonlinear equation (Equation (70)) yields This problem is first solved using the error estimator (

23) (called the old estimator hereafter) by the

with the LTZ element method. Second, this problem is solved using a modified posteriori error estimator (called the new estimator hereafter) by the

with the LTZ element method. For any

and any

, the new estimator is defined as

where

For this new estimator, the following reliability result holds:

where

is a constant dependent only on the shape regularity of mesh

and independent of

.

The Dörfler parameter is in all adaptive finite element computations for the Kellogg problem.

Figure 4 shows the convergence history of the

with the LTZ element method using the old estimator and new estimator. Although both adaptive methods converge with the optimal rate, energy norm errors of the adaptive LTZ element method with a new estimator are smaller than those of the old estimator under the same scale.

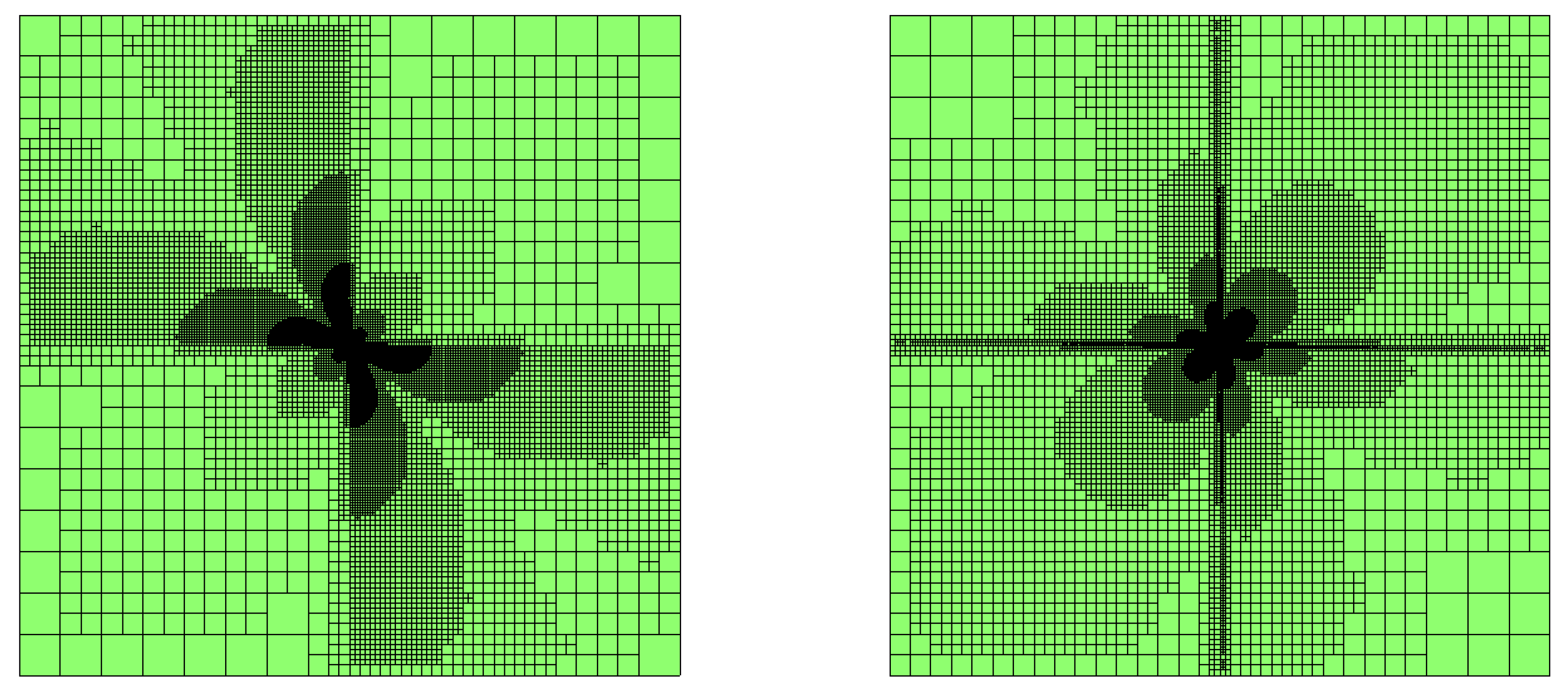

Figure 5 shows two intermediate meshes generated by the above two ANFEMs. As demonstrated by the two images in

Figure 5, the new estimator demonstrates superior efficiency in detecting singularities, consequently achieving more favorable results.