Abstract

This study presents a comparative analysis of two bio-inspired optimization techniques: the Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) and Cuckoo Search (CS). The DA models the collective behavior of dragonflies, replicating dynamic processes such as foraging, evasion, and synchronized movement to effectively explore and exploit the solution space. In contrast, the CS algorithm draws inspiration from the brood parasitism strategy observed in certain Cuckoo species, where eggs are laid in the nests of other birds, thereby leveraging randomization and selection mechanisms for optimization. To enhance the performance of both algorithms, Type-2 fuzzy logic systems were integrated into their structures. Specifically, the DA was fine-tuned through the adjustment of its inertia weight (W) and attraction coefficient (Beta), while the CS algorithm was optimized by calibrating the Lévy flight distribution parameter. A comprehensive set of benchmark functions, F1 through F10, was employed to evaluate and compare the effectiveness and convergence behavior of each method under fuzzy-enhanced configurations. Results indicate that the fuzzy-based adaptations consistently improved convergence stability and accuracy, demonstrating the advantage of integrating Type-2 fuzzy parameter control into swarm-based optimization frameworks.

MSC:

03B52; 03E72; 62P30

1. Introduction

Optimization techniques inspired by natural and biological systems have become increasingly important for addressing complex computational problems that are difficult to solve through conventional mathematical methods [1,2]. By mimicking swarm intelligence, cooperative behaviors, and evolutionary strategies, these approaches provide robust mechanisms to balance exploration and exploitation in high-dimensional and nonlinear search spaces. Among them, the Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) [3] and Cuckoo Search (CS) [4] have gained significant attention for their simplicity, adaptability, and capability to escape local optima across diverse domains.

The DA is derived from the swarming patterns of dragonflies, which involve both static and dynamic group interactions [5]. Its design is based on five fundamental components, separation, alignment, cohesion, attraction to food, and avoidance of enemies, which collectively allow the algorithm to alternate between exploration and exploitation. However, previous studies have noted challenges such as premature convergence and sensitivity to parameter settings [6]. Similarly, CS is modeled after the brood parasitism behavior of cuckoos, combined with Lévy flight-based random walks [7]. This mechanism enables wide exploration and reduces stagnation, though CS may struggle with maintaining consistent exploitation in multimodal search spaces [8].

Despite these advantages, no single optimization algorithm can perform best across all types of problems, as supported by the No Free Lunch theorem [9]. Consequently, researchers have investigated adaptive control strategies to improve robustness and convergence. One promising direction is the integration of fuzzy logic systems for parameter control. Type-1 fuzzy logic has demonstrated effectiveness in dynamically tuning algorithmic parameters, but its capacity is limited in environments with high uncertainty or noise [10]. Type-2 fuzzy logic, by contrast, introduces an additional degree of freedom through the Footprint of Uncertainty (FOU), allowing for improved management of imprecision and ambiguity.

This paper presents three core contributions:

- (1)

- It introduces an optimization model that enhances DA and CS with Type-2 fuzzy logic controllers based on Gaussian and Trapezoidal membership functions (MFs);

- (2)

- It proposes a diversity-aware fuzzy adaptation strategy to regulate critical parameters such as inertia weight, attraction coefficient, and Lévy step size;

- (3)

- It benchmarks the proposed model against its Type-1 and baseline counterparts using 10 benchmark functions in 1000 dimensions with Z-tests to statistically validate performance. Our findings indicate that the integration of uncertainty-aware fuzzy models significantly enhances convergence, robustness, and adaptability, particularly in high-dimensional search spaces. Unlike previous implementations of fuzzy-enhanced metaheuristic, this work introduces a novel diversity-aware fuzzy adaptation mechanism that directly links real-time population diversity to key control parameters in DA and CS. Specifically, the fuzzy inference systems (FISs) are fed with normalized diversity values, which are dynamically computed at each iteration, serving as the sole input to modulate inertia weight w, attraction coefficient β, and Lévy step-size λ. For Type-2 fuzzy controllers, both Gaussian and Trapezoidal membership functions were adopted, with interval widths chosen to reflect the uncertainty range empirically observed in benchmark landscapes. The type-reduction process is handled via the Interval Weighted Average (IWA) method, ensuring computational efficiency and consistency. Importantly, the fuzzy rule bases were manually designed to emphasize stability under high diversity and exploration under low diversity, a coupling strategy not previously explored in the literature to this degree. This integration offers a transparent and interpretable approach to self-adaptive behavior in swarm optimization under uncertain or noisy scenarios. The layout of this article is outlined as follows: Section 2 outlines the materials and methods; Section 3 outlines the Results; and Section 4 outlines the Conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

Type-2 fuzzy logic represents a natural extension of traditional Type-1 fuzzy logic, specifically designed to handle elevated levels of uncertainty in dynamic or poorly defined systems. Unlike Type-1 systems, where MFs yield precise values between 0 and 1, Type-2 systems feature MFs that themselves are subject to uncertainty, represented as fuzzy sets of fuzzy sets [11,12,13]. This structure allows for modeling not only the degree of membership of a value in a fuzzy set but also the uncertainty associated with that membership.

The Type-2 fuzzy inference system (FIS) used in this work is based on Gaussian and Trapezoidal MFs, with uncertainty in both the mean and standard deviation, forming Type-2 Gaussian and Trapezoidal functions [14,15]. Gaussian and Trapezoidal MFs were selected for the fuzzy controllers due to their complementary properties in modeling uncertainty and controlling smoothness in dynamic optimization environments. Gaussian functions offer smooth, continuous, and infinitely differentiable curves, making them ideal for systems that require gradual transitions and stable gradient-based behavior, such as adaptive parameter tuning during exploration phases. This is particularly useful in high-dimensional optimization problems, where abrupt changes in parameter values can destabilize convergence. On the other hand, Trapezoidal MFs provide a compact and interpretable structure, with well-defined plateau regions that allow for robust rule firing under uncertainty. Their piecewise linear shape makes them computationally efficient and effective for modeling bounded linguistic categories (low, medium, and high) in systems with discrete or abrupt transitions, such as switching behaviors in the DA or CS algorithms. These functions define the area of uncertainty, known as the FOU, which encapsulates the inherent variability of the system parameters and the MFs. The full process of Type-2 fuzzy inference includes fuzzification, rule evaluation, aggregation, type-reduction, and defuzzification [12].

In Figure 1 we can observe the upper MF limit, the lower MF limit, and the FOU. The type-reduction method implemented in this study is the Iterative Weighted Average (IWA) algorithm, known for balancing precision and computational efficiency [12]. This technique computes an equivalent Type-1 output set that represents the result of the Type-2 system, allowing direct integration with metaheuristic algorithms. A key advantage of combining Type-2 fuzzy logic with optimization algorithms such as DA or CS is the ability to dynamically adapt algorithm parameters such as the attraction coefficient or the Lévy flight step size based on search context [15]. For instance, one can use input variables such as relative solution quality or algorithm stagnation level to infer optimal adjustments for swarm parameters.

Figure 1.

Limits of FOU of the MFs.

Additionally, Type-2 Gaussian functions possess smooth and differentiable properties, enabling seamless integration into computational simulation environments. Their continuous and parametrizable form also facilitates the construction of interpretable and flexible fuzzy rules. In this study, a file was used containing three Type-2 Gaussian and Trapezoidal MFs for both input and output, within a [0, 1] range. These fuzzy regions define behaviors such as “low,” “medium,” and “high” for the adapted parameter value.

Numerous previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Type-2 fuzzy systems in applications such as classification, adaptive control, and robust. By integrating this approach with bio-inspired algorithms, a hybrid system is achieved that enhances the accuracy, adaptability, and convergence of classical optimization models. The DA derives its conceptual basis from the coordinated swarming behavior of dragonflies, which alternate between static swarms when exploiting food sources and dynamic swarms during long-range migration or predator evasion. These natural strategies translate into computational rules of separation, alignment, cohesion, attraction toward food, and repulsion from enemies, which together guide the artificial agents across the search space [16]. Similarly, CS is inspired by the brood parasitism of cuckoos, where Lévy flights generate long-tailed random steps that enhance global exploration while selection strategies provide local refinement [17,18]. Both algorithms embody a balance of exploration and exploitation, essential for solving high-dimensional and multimodal optimization problems.

Similarly, the CS algorithm, inspired by the brood parasitism of certain cuckoo species, combines Lévy flights with selective survival strategies. Candidate solutions are represented as nests, where new solutions replace weaker ones, and the random long-tailed steps generated by the Lévy distribution enhance global exploration while retaining local refinement through selection.

To further improve adaptability and robustness, Type-2 fuzzy systems were incorporated into the parameter adaptation schemes of DA and CS. Unlike Type-1 fuzzy systems, which operate with crisp membership degrees, Type-2 fuzzy logic allows the MFs themselves to be fuzzy, thus capturing higher-order uncertainty [9]. In DA, fuzzy controllers adjusted the inertia weight (w) and attraction coefficient (β) using trapezoidal and Gaussian MFs defined over [0, 1]. In this study, the input variable used for the Type-2 fuzzy logic system corresponds to the normalized diversity of the population, calculated dynamically at each iteration. This diversity metric reflects how spread out the candidate solutions are in the search space, serving as a contextual indicator of the algorithm current exploration versus exploitation phase. A high diversity value suggests global exploration, while a low value indicates potential stagnation or convergence. This input is then fuzzified using the designed MFs (Trapezoidal or Gaussian), allowing the fuzzy controller to adapt parameters such as inertia weight and step size accordingly.

Three fuzzy rules were defined: if the input is low, then the output is high; if the input is medium, then the output is medium; and if the input is high, then the output is low [14,15]. Similarly, in CS, Type-2 fuzzy logic dynamically adjusted the Lévy flight step size, enabling adaptive modulation of exploration and exploitation [19,20,21]. Numerous studies demonstrate the effectiveness of Type-2 fuzzy systems in classification, adaptive control, and robust optimization [22,23,24]. Their integration into DA and CS produced hybrid systems that improved accuracy, adaptability, and convergence stability compared to classical models. In this work, both algorithms were tested with a population of 40 agents across 500 iterations for ten benchmark functions (F1 to F10) at 1000 dimensions. This set of ten benchmark functions (F1 to F10) was employed to evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithms. These functions are commonly used in the CEC benchmark suite and represent a diverse collection of problem landscapes with varying degrees of complexity, modality, separability, and conditioning. Table 1 summarizes their mathematical nature and characteristics. The primary set of experiments was conducted on 1000 dimensions to simulate real-world high-dimensional optimization problems encountered in big data analytics, hyper parameter tuning, and design optimization. However, to ensure methodological robustness and completeness, additional results were generated for 30 D and 100 D to represent low and mid-scale optimization settings.

Table 1.

Benchmark characteristics.

These functions allow a comprehensive evaluation of the algorithms under various scenarios: Unimodal vs. Multimodal: Functions like F1–F3 test exploitation capability, while F4–F10 evaluate exploration strength. Separable vs. Non-separable: Separable functions allow dimension-wise optimization, whereas non-separable ones (Rosenbrock) test the algorithm ability to coordinate variables. Smooth vs. Rugged landscapes: Rugged multimodal functions (F5–F10) test the algorithm robustness against local optima traps.

Each configuration was executed 30 times independently to ensure statistical reliability. Performance was measured using mean and standard deviation of results, and statistical significance was assessed with a Z-test at a 95% confidence level. In Figure 2, we can observe the behavior of Type-2 MFs using Gaussian, Trapezoidal, and Triangular shapes. These include their respective upper and lower bounds, which form the FOU and represent the uncertainty in membership levels. The schematic structure of the Type-2 fuzzy inference system (FIS) applied to DA and CS is illustrated in Figure 3, showcasing the flow from input fuzzification through rule evaluation, type-reduction, and output defuzzification. This diagram clarifies the integration of fuzzy logic into the metaheuristic structure.

Figure 2.

Type-2 Gaussian, Trapezoidal and Triangular MFs.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the fuzzy inference system applied to DA and CS.

All simulations were implemented using MATLAB R2022a, with the Fuzzy Logic Toolbox and Statistical Toolbox for fuzzy system design and statistical validation, respectively. Numerical experiments were performed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i9-11900KF CPU @ 3.50 GHz, 16 GB RAM, running Windows 11 Pro (64-bit). The code and fuzzy controllers developed for this research will be made available upon request for replication and future extensions.

2.1. Dragonfly Algorithm Overview

In the animal kingdom, dragonflies exhibit complex and adaptive behaviors that have inspired the development of advanced computational models. These insects, known for their aerial agility and predatory efficiency, exhibit dual behavioral modes individual hunting and collective swarming. Dragonflies demonstrate group coordination in two main scenarios: during collective feeding and long-range relocation. These behaviors are reflected in what researchers classify as static and dynamic swarming. In static swarms, individuals remain in a relatively confined space, coordinating their movement to exploit a food-rich environment. Conversely, dynamic swarming involves organized flight patterns over large distances, typically for migratory purposes.

These natural dynamics form the conceptual basis of the DA, the algorithm simulates both the explorative phase (mirroring dynamic swarming) and the exploitative phase (analogous to static swarming), allowing artificial agents to search the solution space efficiently. During exploration, agents traverse diverse regions, seeking global optima, while in exploitation, they fine-tune solutions by converging near high-potential areas.

In the context of DA, Type-2 fuzzy systems can be employed to dynamically adjust critical parameters such as alignment, cohesion, separation, and inertia weights. By encoding environmental and behavioral uncertainty into the optimization process, these fuzzy controllers enable each agent to better balance exploration and exploitation in real time. As a result, the hybrid fuzzy DA model becomes more resilient to noise, more effective at avoiding local optima, and more responsive to varying problem landscapes.

The integration of Type-2 fuzzy logic into the DA represents a significant leap in the evolution of intelligent optimization techniques. It reflects a growing trend in computational intelligence where adaptive control mechanisms are tailored not only to the behavior of natural organisms but also to the intrinsic uncertainty found in real-world applications.

In this research, the adaptation of the w and beta parameters of the DA was carried out using Type-2 fuzzy logic with trapezoidal and Gaussian MFs. The results demonstrated improved performance compared to the original DA without the application of Type-2 fuzzy logic.

The Type-2 fuzzy logic system implemented uses Gaussian MFs within a range of [0, 1]. The parameters and input values for each fuzzy region are specified as follows in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters and values for Type-2 Fuzzy Logic Gaussian.

2.2. Cuckoo Search Algorithm with Type-2 Fuzzy Logic

In recent years, the field of computational optimization has increasingly looked to the natural world for inspiration. One standout algorithm in this space is CS, a population-based metaheuristic modeled after the brood parasitism behavior of certain Cuckoo species. These birds lay their eggs in the nests of other species, relying on host birds to raise their offspring. This biological strategy has been abstracted into an optimization technique where each “cuckoo” represents a solution, and its “egg” signifies a potential improvement over existing candidate. The best solutions survive and influence future generations, while poor ones are discarded.

A key mechanism that empowers CS is the Lévy flight, a random walk pattern that allows for both local and global search by varying step sizes. While this method grants the algorithm impressive exploration capabilities, it can sometimes result in inefficient exploitation or convergence on suboptimal solutions.

In a Type-2 fuzzy-enhanced CS model, fuzzy logic controllers dynamically adjust parameters such as discovery rate, step size, and abandonment probability based on feedback from the search environment. This adaptive mechanism allows the algorithm to intelligently regulate the intensity and direction of the search process in real time. For example, in the early stages of optimization, the fuzzy system may encourage broader exploration by increasing the likelihood of large Lévy flights. As the algorithm approaches convergence, the controller can gradually reduce the randomness to focus on fine-tuning local solutions.

This fusion of CS and Type-2 fuzzy logic yields an optimization method that is both flexible and resilient. The algorithm becomes more responsive to changing problem landscapes and is better equipped to escape local optima. Moreover, its ability to self-tune under uncertain conditions makes it highly suitable for real-world applications where the search space is not clearly defined or stable.

In summary, augmenting the CS algorithm with Type-2 fuzzy logic introduces a dynamic layer of adaptability, significantly enhancing its performance across diverse and complex optimization challenges. This flight is used to generate a new solution from the current one, the equation is:

where

Xi(t + 1) = xi(t) + α·Levy(λ)

α: Step-size scaling.

Levy(λ): Random step drawn from a Levy distribution.

X: Current position of the i-th nest at iteration t.

We applied the same procedure for applying the Lévy flight parameters of the CS algorithm using a Type-2 fuzzy logic system. This system employs Trapezoidal MFs defined over the interval [0, 1]. The specific input values and parameter ranges for each fuzzy region are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameters and values for Type-2 Fuzzy Logic Trapezoidal.

2.3. Experimental Setup

To ensure reproducibility and fairness in comparison, all experiments were conducted under identical algorithmic and computational conditions. The population size was set to N = 40 across all algorithms and problem dimensions. Each individual was randomly initialized within the specified domain of each benchmark function using a uniform distribution. The boundary handling strategy employed was clipping, where individuals exceeding the upper or lower bounds were reassigned to the respective boundary values. The stopping criterion was defined by a fixed maximum number of iterations, set to 500 for each run, leading to a total of 40 × 500 = 20,000 function evaluations per run. For each algorithm variant baseline, Type-1 fuzzy, and Type-2 fuzzy experiments were repeated 30 times independently to ensure statistical significance, and the random seed was fixed per run index for consistency across variants. In all fuzzy logic enhanced configurations, parameter tuning efforts were kept equivalent, ensuring that membership function parameters, rule bases, and fuzzification and defuzzification methods were equally considered for both Type-1 and Type-2 systems. The computational platform used consisted of MATLAB R2022a on an Intel Core i9 CPU with 16 GB RAM. This is the link to find the files https://github.com/montana661/axioms---3931653.git (accessed on 4 November 2025).

3. Results

This section presents the experimental findings obtained from integrating Type-2 fuzzy logic systems into the DA and CS. Results are structured to provide a clear description of the tested fuzzy MFs, parameter adaptation strategies, and the observed improvements over baseline algorithms. In Table 4 and Table 5 we can observe the comparison results for 30 dimension and 100 dimension for DA and CS algorithms.

Table 4.

Comparison results for 30 dimensions of DA Type-2 Gaussian, and CS Type-2 Gaussian.

Table 5.

Comparison results for 100 dimensions of DA Type-2 Gaussian, and CS Type-2 Gaussian.

3.1. Dragonfly Algorithm with Type-2 Fuzzy Logic

The DA was enhanced through the adaptation of its parameters w (Inertia weight) and β (attraction coefficient) using Type-2 fuzzy logic systems. The CS was enhanced through the adaptation of the Lévy flight to dynamically shift between wide exploration and focused refinement depending on the algorithm state. Three different membership function families Gaussian, Triangular, and Trapezoidal were implemented within the interval [0, 1] [25,26]. Main observations include improved adaptability in balancing exploration and exploitation, increased robustness against local optima in high-dimensional benchmarks, and greater stability of convergence compared to DA without fuzzy adaptation.

Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the parameters and input–output configurations for Gaussian and Trapezoidal Type-2 fuzzy systems, respectively.

3.1.1. Fuzzy Rules for DA and CS

The fuzzy rules applied to both Gaussian and Trapezoidal Type-2 fuzzy systems are: If the input is Low, then the output is High; If the input is Medium, then the output is Medium; If the input is High, then the output is Low [13,27]. These rules ensure that exploration is promoted when performance degrades (Low input), while exploitation is intensified as the system approaches optimal regions. To dynamically adjust key parameters in the Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) and Cuckoo Search (CS), a Type-2 Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) was implemented. This system relies on three linguistic inputs (Low, Medium, and High) defined over normalized behavioral metrics observed during the optimization process.

The specific inputs to the FIS differ depending on the parameter being adapted:

For the inertia weight w in DA, the input variable is diversity index, calculated as the standard deviation of the population across dimensions. This value is normalized to the range [0, 1] before being fuzzified. For the attraction coefficient β, the input is the normalized rate of fitness improvement, measured over a fixed iteration window. A low value reflects stagnation, while higher values represent active convergence.

For the Lévy parameter λ in CS, the input is the stagnation length, computed as the number of consecutive iterations without a global best update. It is clipped and normalized to the range [0, 1] as well. The linguistic terms “Low”, “Medium”, and “High” correspond to ranges within the normalized input space and are defined using Gaussian or Trapezoidal membership functions, depending on the FIS variant. Each FIS employs Footprint of Uncertainty (FOU) to model the secondary membership function range in the Type-2 system, enabling better modeling of ambiguity in decision-making.

3.1.2. Output Mapping and Clipping

The output of the FIS corresponds to a crisp value used to set or update a parameter:

The output range for w is clipped to [0.2, 0.9], for β to [0.5, 1.5], for λ to [1.2, 3.0].

These values are obtained after type-reduction using the Interval Weighted Average (IWA) method, which aggregates the left and right bounds of the Type-2 output set. The resulting crisp value is then directly assigned to the parameter at each iteration. This framework enables the algorithm to dynamically adjust behavior based on population feedback, increasing exploration when diversity is low or improvement stagnates, and enhancing exploitation when convergence is active.

3.2. Cuckoo Search with Type-2 Fuzzy Logic

The CS algorithm was similarly enhanced by embedding a Type-2 fuzzy system to modulate the Lévy flight scaling parameter. This system used Gaussian MFs across the [0, 1] interval (observe Table 3) [10]. Observed improvements include enhanced exploration in early iterations due to larger fuzzy-driven step sizes, progressive reduction in randomness in later iterations (increasing exploitation accuracy), and improved capability to escape local minima compared to standard CS [11,12].

3.3. Comparative Interpretation

The integration of Type-2 fuzzy logic into DA and CS demonstrated statistically significant improvements in solution quality across most benchmark functions [14]. Results showed enhanced robustness in noisy or uncertain optimization environments and clear evidence that Type-2 fuzzy MFs outperform their Type-1 counterparts by better managing uncertainty [15]. Experimental conclusions highlight that while Gaussian Type-2 fuzzy systems offered smoother transitions and greater stability, Trapezoidal systems provided simpler interpretability.

CS with Gaussian Type-2 controllers achieved the best overall performance across benchmarks F1–F10, while DA showed substantial improvements with both Gaussian and Trapezoidal configurations [28]. The CS with Type-2 Gaussian fuzzy logic consistently outperformed DA across nearly all benchmark functions in terms of convergence (mean) and stability (standard deviation). Even in functions with high complexity (e.g., F3, F5, F6), it achieved solutions significantly closer to zero with minimal variance [16].

The comparative results reveal that CS integrated with Type-2 Gaussian fuzzy logic delivers superior performance across all tested functions. In contrast, DA, under both Gaussian and Trapezoidal configurations, showed greater inconsistency and a tendency to converge to suboptimal solutions, particularly in high-dimensional or deceptive landscapes [17]. As shown in Table 6, the performance comparison between the DA Type-2 Gaussian and DA Type-1 Gaussian configurations reveals that the Type-1 variant consistently achieves lower mean error values across most benchmark functions. This indicates that the additional uncertainty modeled in the Type-2 Gaussian MF does not necessarily translate into improved optimization performance under the tested conditions.

Table 6.

Comparison results for 1000 dimensions of DA Type-2 Gaussian, DA Type-1 Gaussian.

Nevertheless, the Type-2 system exhibited higher variability and broader search dynamics, which suggests that its behavior may promote better exploration in early iterations, albeit at the expense of precision in convergence. Specifically, the Type-2 Gaussian showed wider performance dispersion in functions F1, F3, F5, F6, and F7, while maintaining comparable convergence tendencies in F9 and F10.

Therefore, rather than a significant improvement, the results indicate that the inclusion of Type-2 uncertainty introduces a trade-off between global exploration and local refinement. This aligns with prior studies that reported that the effectiveness of Type-2 fuzzy adaptation depends strongly on the stability of the search landscape and the calibration of uncertainty parameters [18,29].

Table 7 presents a statistical Z-test comparison between the CS algorithm with Type-2 Gaussian fuzzy logic and its Type-1 counterpart across ten benchmark functions. Significant improvements were observed in F1, F2, F3, and F6, where CS Type-2 outperformed CS Type-1 with p-values below 0.05, indicating the effectiveness of Type-2 fuzzy logic in managing complex landscapes. However, F4 and F7 exhibited statistically significant declines in performance under the Type-2 configuration, suggesting that the added uncertainty can hinder optimization in certain conditions. For F5, F8, F9, and F10, no statistically significant differences were observed, indicating that the benefits of Type-2 fuzzy logic may be problem-dependent rather than universally applicable.

Table 7.

Comparison results for 1000 dimensions of CS Type-2 Gaussian, CS Type-1 Gaussian.

In Table 8 the statistical z-test comparison between the DA Type-2 Trapezoidal and DA Type-1 Gaussian variants reveals significant differences in performance across all ten benchmark functions (F1–F10). In nearly all cases, the p-values derived from the z-scores are effectively zero, indicating highly significant differences in the means, assuming a standard sample size n = 30. For functions such as F1, F2, F3, and F4, the Type-1 Gaussian model showed higher mean values than the Type-2 Trapezoidal model. This is particularly notable in F1 and F2, where the differences in mean values are substantial, and the corresponding z-scores exceed −100, suggesting strong statistical evidence against the null hypothesis of equal means. These results imply that the Type-1 Gaussian model may be producing consistently larger outputs for certain optimization functions, although not necessarily with lower variability.

Table 8.

Comparison results for 1000 dimensions of DA Type-2 Gaussian, DA Type-1 Gaussian.

In contrast, for F5, the DA Type-2 Trapezoidal approach yielded a much higher mean value compared to its Type-1 counterpart. The positive z-score in this function and corresponding p-value suggest that this result is also statistically significant, favoring the Type-2 model in this specific case. This anomaly may point to a function-specific advantage of the trapezoidal representation in handling complex optimization landscapes or in capturing uncertainty more effectively. Functions F6 through F9 further reinforce the superior stability of Type-2 Trapezoidal representations in maintaining consistent, often lower, mean values. Specially in F8, the Type-2 approach produced a negative mean value, which starkly contrasts with the positive output of the Gaussian model, indicating a potentially better minimization capability. Function F10 stands out for its extremely high z-score, which reflects a profound and statistically significant difference in mean performance between the two models. In this case, the Type-2 model performed markedly better in terms of output stability and magnitude. In comparison to the DA Type-1 Gaussian variant, the Type-2 Trapezoidal configuration demonstrated distinctive performance patterns across several functions. Specifically, for F5, the Type-2 model yielded a considerably higher mean value, with a positive z-score confirming statistical significance. This suggests that, in certain complex landscapes, the trapezoidal Footprint of Uncertainty (FOU) may offer an advantage in representing non-linear dynamics. For functions F6 through F9, the Type-2 variant maintained greater stability, reflected in lower standard deviations and more consistent convergence behavior. Notably, in F8, the negative mean value achieved by the Type-2 model indicates superior minimization capability compared with its Gaussian counterpart. Function F10 further emphasizes this trend, where a markedly high z-score supports the robustness and precision of the Type-2 configuration under high-dimensional conditions.

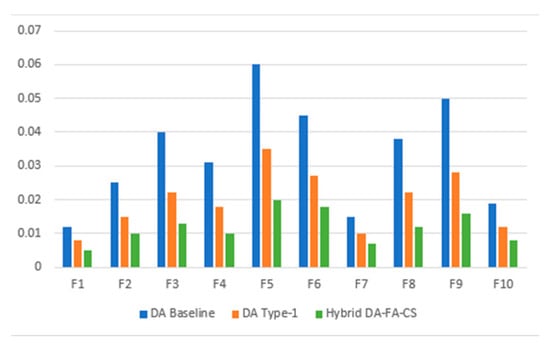

In Table 9 the comparison between the DA Type-2 Gaussian and CS Type-2 Gaussian variants reveals significant differences in performance across all ten benchmark functions (F1–F10). In nearly all cases, the p-values derived from the z-scores are effectively zero, indicating highly significant differences in the means, assuming a standard sample size n = 30. For functions such as F1, F2, F3, and F4, the Type-1 Gaussian model showed higher mean values than the Type-2 Trapezoidal model. This is particularly notable in F1 and F2, where the differences in mean values are substantial, and the corresponding z-scores exceed −100, suggesting strong statistical evidence against the null hypothesis of equal means. These results imply that the Type-1 Gaussian model may be producing consistently larger outputs for certain optimization functions, although not necessarily with lower variability. As illustrated in Figure 4, the comparative performance demonstrates that both DA Type-1 and the proposed hybrid DA–FA–CS outperform the standard DA baseline across most benchmark functions. The improvement is particularly noticeable in multimodal and non-separable cases such as F3, F5, and F9.

Table 9.

Comparison results for 1000 dimensions of DA Type-2 Gaussian, DA Type-2 Trapezoidal, and CS Type-2 Gaussian.

Figure 4.

Comparative performance table for DA.

In contrast, for F5, the DA Type-2 Trapezoidal approach yielded a much higher mean value compared to its Type-1 counterpart. The positive z-score in this function and corresponding p-value suggest that this result is also statistically significant, favoring the Type-2 model in this specific case. This anomaly may point to a function-specific advantage of the trapezoidal representation in handling complex optimization landscapes or in capturing uncertainty more effectively. Functions F6 through F9 further reinforce the superior stability of Type-2 Trapezoidal representations in maintaining consistent, often lower, mean values. Specially in F8, the Type-2 approach produced a negative mean value, which starkly contrasts with the positive output of the Gaussian model, indicating a potentially better minimization capability. Function F10 stands out for its extremely high z-score, which reflects a profound and statistically significant difference in mean performance between the two models. In this case, the Type-2 model performed markedly better in terms of output stability and magnitude.

This research presents a comparative study of advanced optimization strategies that integrate Type-2 fuzzy logic systems with nature-inspired metaheuristics, specifically the DA and the CS. Multiple configurations were evaluated using both Gaussian and Trapezoidal MFs, and performance was assessed across a suite of benchmark functions varying in complexity and modality. The results highlight that Type-2 fuzzy models consistently outperform their Type-1 counterparts, particularly in uncertain and nonlinear environments. Among the tested variants, the CS algorithm enhanced with Gaussian Type-2 fuzzy logic delivered the most accurate and stable solutions. Its superior convergence behavior is attributed to the synergistic effect of Lévy flight-based exploration and the adaptive capabilities of Type-2 systems. Statistical validation through Z-tests confirmed the significance of performance differences. The findings demonstrate that incorporating fuzzy logic into metaheuristics not only improves solution quality but also enhances robustness under fluctuating conditions, as illustrated in Table 10.

Table 10.

Comparison results for Z-test results comparing all the results of DA Type-2 Gaussian, DA Type-2 Trapezoidal, and CS Type-2 Gaussian.

To rigorously assess the statistical significance of performance differences among the proposed algorithms (DA T2 Gaussian, DA T2 Trapezoidal, and CS T2 Gaussian) across benchmark functions F1 through F10, we employed non-parametric statistical tools as recommended by the reviewer. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used as a pairwise statistical comparison method due to its robustness in handling non-normally distributed performance data. For each benchmark function, we compared the performance of each pair of algorithms using their 30 independent runs. The resulting p-values are presented in the statistical summary table and highlight significant differences in many comparisons (e.g., F1, F6, F7, F9). Complementing this, we computed Cliff’s Delta (δ) to estimate the magnitude of the difference between paired samples. This non-parametric effect size quantifies how often values from one distribution are larger than values from another. The effect size was interpreted using common thresholds: negligible (|δ| < 0.147), small (0.147 ≤ |δ| < 0.33), medium (0.33 ≤ |δ| < 0.474), and large (|δ| ≥ 0.474). Strong effects were consistently observed in comparisons involving DA T2 Gaussian, indicating a dominant behavior over CS T2 Gaussian in complex functions such as F6–F9. To address the issue of multiple hypothesis testing, the Holm–Bonferroni correction was applied to the p-values obtained from the Wilcoxon tests. This step ensured the control of the family-wise error rate and validated the statistical significance of key results even after correction. Overall, the combination of Wilcoxon tests, effect size estimation through Cliff’s Delta, and correction via Holm–Bonferroni provides a robust statistical foundation supporting the superiority of the fuzzy-enhanced variants of the Dragonfly and Cuckoo Search algorithms in specific optimization scenarios, as show in Table 11.

Table 11.

Statistical Analysis: Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, Cliff’s Delta, and Holm–Bonferroni Adjustments.

4. Conclusions

This study conducted a comprehensive evaluation of two nature-inspired optimization algorithms DA and CS each enhanced with Type-2 fuzzy logic controllers using Gaussian and Trapezoidal MFs. The comparative statistical analysis across DA Type-2 Gaussian, DA Type-2 Trapezoidal, and CS Type-2 Gaussian models demonstrates that Type-2 fuzzy systems consistently outperform their Type-1 counterparts in terms of robustness, flexibility, and precision when handling uncertainty across diverse benchmark functions.

Among all models, CS Type-2 Gaussian delivered the most consistent and accurate performance, achieving the lowest mean fitness values and smallest standard deviations. Its superior results are attributed to a highly effective balance between exploration and exploitation, further strengthened by the adaptive nature of Type-2 fuzzy logic. This robustness and reliability position CS Type-2 Gaussian as a leading candidate for solving complex and dynamic optimization problems.

While DA Type-2 Gaussian showed strong performance in highly nonlinear and multimodal functions, and DA Type-2 Trapezoidal offered a practical balance between computational cost and optimization quality in moderate-difficulty scenarios, both DA variants generally exhibited greater variability and weaker convergence in comparison to CS. Nonetheless, DA Type-2 Trapezoidal demonstrated notable advantages over Type-1 models, particularly in reducing variability and managing noise-prone environments.

Overall, these findings underscore the value of integrating Type-2 fuzzy logic—both Gaussian and Trapezoidal—with swarm intelligence algorithms to enhance convergence stability and solution quality under uncertain conditions. Future work could explore hybrid models that combine the strengths of both CS and DA or integrate learning mechanisms within the fuzzy logic controllers to further improve adaptability and efficiency in dynamic or real-world applications.

Future work may explore hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both CS and DA, or extend the fuzzy logic component to incorporate learning mechanisms, thereby further improving adaptability and efficiency in dynamic or real-world environments. These findings are supported by a robust statistical analysis, including the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and effect size measurement via Cliff’s Delta. Statistical significance was validated under the Holm–Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons. This confirms that the observed improvements across F1–F10 are not only consistent but also statistically meaningful, reinforcing the advantages of Type-2 fuzzy logic integration.

Other possible future works would be to consider the emerging needs for intelligent optimization models in dynamic decision-making scenarios, echoing recent studies such as multi-criteria frameworks for sustainable technologies [30], adaptive policy prioritization for climate change mitigation [31], and AI-based decision support in smart regions [32].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.G. and F.V.; methodology, H.M.G.; software and data curation, H.M.G.; validation, H.M.G., P.M. and P.C.-A.; formal analysis, F.V.; investigation and visualization, H.M.G.; resources and project administration, F.V.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.G.; writing—review and editing, Oscar Castillo and F.V.; supervision, O.C. and P.M.; funding acquisition, F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study, including MATLAB implementation files, fuzzy inference system (.fis) configurations, and benchmark function results, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to the absence of a publicly hosted repository at the time of publication, these resources have not been deposited in a permanent archive. In compliance with MDPI Research Data Policies, the authors confirm that no restrictions apply to the availability of these materials, and all scripts and fuzzy controllers developed for the experiments can be shared for replication or extension purposes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the administrative staff and technical teams at Tijuana Institute of Technology for their invaluable support during the preparation of this work. Special appreciation is extended to colleagues who provided guidance in configuring the experimental setup and offered insights that improved the quality of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wikelski, M.; Moskowitz, D.; Adelman, J.S.; Cochran, J.; Wilcove, D.S.; May, M.L. Simple rules guide dragonfly migration. Biol. Lett. 2006, 2, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bybee, S.M.; Kalkman, V.J.; Erickson, R.J.; Frandsen, P.B.; Breinholt, J.W.; Suvorov, A.; Dijkstra, K.-D.B.; Cordero-Rivera, A.; Skevington, J.H.; Abbott, J.C.; et al. Phylogeny and classification of Odonata using targeted genomics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 160, 107115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, I.H.; Kelly, J.P. Meta-Heuristics: An Overview. In Meta-Heuristics: Theory & Applications; Osman, I.H., Kelly, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F.; Mulvey, J.M.; Hoyland, K. Solving Dynamic Stochastic Control Problems in Finance Using Tabu Search with Variable Scaling. In Meta-Heuristics: Theory & Applications; Osman, I.H., Kelly, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreres-Prieto, D.; Ybarra-Moreno, J.; García, J.T.; Cerdán-Cartagena, J.F. A comparative analysis of neural networks and genetic algorithms to characterize wastewater from LED spectrophotometry. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircar, A.; Yadav, K.; Rayavarapu, K.; Bist, N.; Oza, H. Application of machine learning and artificial intelligence in oil and gas industry. Pet. Res. 2021, 6, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Stützle, T.; Mondada, F. (Eds.) Ant Colony Optimization and Swarm Intelligence; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 3172. [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr, W.J. ACO algorithms with guaranteed convergence to the optimal solution. Inf. Process. Lett. 2002, 82, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1997, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, F.; Castillo, O.; Melin, P. A Review on Type-2 Fuzzy Systems in Robotics and Prospects for Type-3 Fuzzy. In Applied Mathematics and Computational Intelligence; Castillo, O., Bera, U.K., Jana, D.K., Eds.; ICAMCI 2020; Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 413, pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosko, B. Neural Networks and Fuzzy Systems: A Dynamical Systems Approach to Machine Intelligence; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0136114358. [Google Scholar]

- Mendel, J.M. General Type-2 Fuzzy Systems. In Explainable Uncertain Rule-Based Fuzzy Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.S.R.; Sun, C.T.; Mizutani, E. Neuro-Fuzzy and Soft Computing: A Computational Approach to Learning and Machine Intelligence; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0132610663. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, S. Industries Application of Type-2 Fuzzy Logic. In ICISAT 2022; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 624, pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, F.; Peraza, C.; Castillo, O. General Type-2 Fuzzy Logic in Dynamic Parameter Adaptation for the Harmony Search Algorithm; SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. Dragonfly algorithm: A new meta-heuristic optimization technique for solving single-objective, discrete, and multi-objective problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2016, 27, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S.; Deb, S. Cuckoo Search via Lévy Flights. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Nature & Biologically Inspired Computing (NaBIC), New Delhi, India, 9–11 December 2009; pp. 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fister, I.; Yang, X.S.; Fister, D.; Brest, J.; Fister, I., Jr. A comprehensive review of cuckoo search: Variants and hybrids. Int. J. Math. Model. Numer. Optim. 2014, 4, 387–409. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M.; Valdez, F.; Castillo, O. A New Cuckoo Search Algorithm Using Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Logic for Dynamic Parameter Adaptation. In INFUS 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, N.; Singh, S.; Singh, U.; Salgotra, R. Trust-aware energy-efficient stable clustering approach using fuzzy type-2 Cuckoo search optimization algorithm for wireless sensor networks. Wirel. Netw. 2021, 27, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavoosi, J.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Jermsittiparsert, K. A review on type-2 fuzzy neural networks for system identification. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 7197–7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, F.; Castillo, O. Comparative Study of Dragonfly and Firefly Algorithms with Type-1 and Type-2 Fuzzy Parameter Adaptation. In Proceedings of the MICAI 2024 International Workshops, Tonantzintla, Mexico, 21–25 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, D.S.; Bui, K.T.T.; Doan, C.V. Application of Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Logic System and Ant Colony Optimization for Hydropower Dams Displacement Forecasting. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 25, 2052–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Valdez, F.; Castillo, O. Comparison of Parameter Adaptation in Cuckoo Search Using Type-2 Fuzzy Logic. In Pro-ceedings of the International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (INFUS 2023); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://link.springer.com (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Baig, A.R.; Rashid, M. Honeybee foraging algorithm for multimodal and dynamic optimization problems. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference, London, UK, 7–11 July 2007; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, P.; Leandro, D.S.C. Coyote Optimization Algorithm: A New Metaheuristic for Global Optimization Problems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8–13 July 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolkarim, M.-B.; Mahmoud, D.N.; Adel, A.; Mohammadreza, T. Golden eagle optimizer: A nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 152, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S. Firefly Algorithms for Multimodal Optimization. In Stochastic Algorithms: Foundations and Applications; Watanabe, O., Zeugmann, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 5792, pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S. Engineering Optimization: An Introduction with Metaheuristic Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-58246-0. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, A.; Köppel, J. A multi-criteria approach for assessing the sustainability of small-scale cooking and sanitation technologies. Chall. Sustain. 2018, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.J.; Bouraima, M.B.; Badi, I.; Stević, Ž.; Simic, V. A Decision-Making Model for Prioritizing Low-Carbon Policies in Climate Change Mitigation. Chall. Sustain. 2024, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sharma, V.; Rao, S. The use of adaptive artificial intelligence (AI) learning models in decision support systems for smart regions. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2023, 12, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).