1. Introduction

Coupled systems consist of two or more subsystems interconnected through dynamic linkages and exhibit significant mutual interactions. Such systems are prevalent across numerous multidisciplinary fields, including engineering and scientific research. Representative examples include mechanical coupling between structural components in building seismic analysis, multi-body interactions among the deck, cables, and towers in bridge dynamics, and vibroacoustic coupling between structural vibration and acoustic propagation. These coupling effects induce intricate emergent behaviors, such as multivariate correlations, which considerably complicate system modeling, performance analysis, and controller design. The decomposition of a multi-degree-of-freedom system into mutually independent single-degree-of-freedom subsystems constitutes a significant research objective, as it facilitates targeted analysis and optimization of specific components while improving the efficiency of complex system design and modification. This represents the fundamental objective of decoupling.

Second-order linear dynamical systems constitute a cornerstone model in scientific and engineering disciplines [

1]. Such systems are typically governed by the following equation:

where

,

, and

represent the given coefficient matrices. Mathematically, this family of systems admits mature and rigorous analytical and computational methods. Considerable theoretical and numerical advances have been made in decoupling second-order linear dynamical systems [

1,

2].

Undamped systems, where

, can be interpreted as a generalized eigenvalue problem (GEP). The eigenvectors obtained from its solution form a congruence transformation matrix, which effectively decouples the system. Based on this theoretical foundation,

classical modal analysis has been developed to decouple

classically damped systems [

3], which are characterized by symmetric coefficient matrices with positive-definite

, non-negative-definite

and

, and satisfaction of the Caughey-O’Kelly commutativity condition [

4] [Theorem 2].

For general

non-proportionally damped systems, several decoupling methods have been developed, as reported in [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, most existing approaches depend on complete spectral information of the system, a requirement that is often infeasible in practical engineering applications.

Spectral decomposition constitutes another analytical technique for decoupling second-order linear dynamical systems. Any solution

to the

quadratic eigenvalue problem (QEP) [

1,

11,

12]

yields a fundamental solution

to the differential system (

1). The spectral properties of the quadratic pencil

dictates the dynamic behavior of the system. For example, the quadeig in [

13] and the polyeig in

Matlab R2011b. Nevertheless, this method depends on obtaining the complete set of eigeninformation, a demanding requirement that is often infeasible in practical applications.

The phase synchronization technique [

14,

15] converts non-classically damped modes into classically damped forms, thereby enabling system decoupling through classical modal analysis. In contrast to classically damped modes characterized by real eigenvectors, non-classically damped modes exhibit complex conjugate eigenvector pairs [

16]. This approach alters modal properties by synchronizing phase differences among modal components via phase shifts, reflecting the fundamental principle of phase synchronization. Nevertheless, the method still requires complete eigeninformation of the system.

In our previous work on decoupling second-order linear dynamical systems, we developed the structure-preserving isospectral transformation flow (SPITF) algorithm [

17]. This framework enables decoupling without requiring complete spectral information. Specifically, SPITF constructs a transformation matrix that preserves the Lancaster structure. Through simultaneous congruence transformations applied to the coefficient matrices

,

, and

, total decoupling is achieved. Preservation of the Lancaster structure ensures invariance of the system’s spectral properties, thereby maintaining consistent dynamic characteristics during decoupling. The theoretical foundation of the SPITF algorithm will be comprehensively presented in

Section 4.

Second-order nonlinear dynamical systems occur more frequently in practical applications. Although decoupling techniques for linear systems have been extensively studied, their extension to nonlinear systems remains limited. Nonlinear systems exhibit inherently complex coupling mechanisms that pose substantially greater challenges for analysis and decoupling compared to their linear counterparts. Consequently, research on decoupling for second-order nonlinear dynamical systems carries significant theoretical and practical importance.

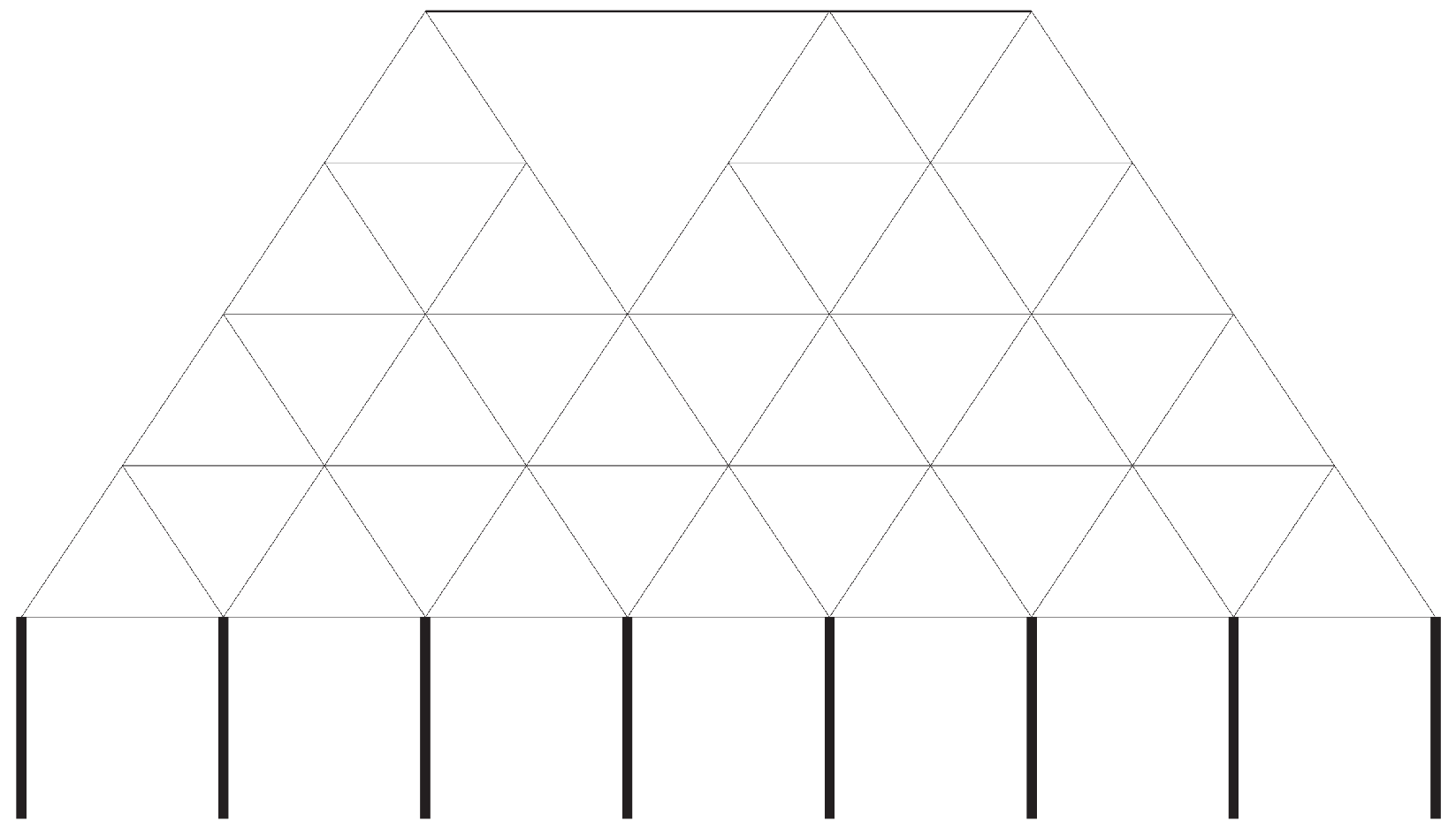

This paper addresses the decoupling of 2D lattice vibration systems, a representative category of second-order nonlinear dynamical systems. Consider a 2D network comprising n masses interconnected by normal springs and dampers in a specified configuration. An example of a 3-mass system is illustrated in

Figure 1, where each mass connects to a fixed end with different sprint elements while the internal sprints consist of one spring and one damper. The configuration in

Figure 1 depicts a fundamental 2D lattice system, with

Figure 2 demonstrating more complex architectures featuring multi-layered spring networks. Such lattice systems find broad applicability across scientific and engineering disciplines [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. In medical domain, they enable analysis of soft tissue elasticity in skin lesions [

26,

27]. In quantum materials research, they enable investigation of the interplay between quantum and topological phase formation [

28]. These systems typically exhibit complex dynamics characterized by multi-degree-of-freedom coupling, presenting substantial challenges in theoretical modeling, numerical implementation, and computational simulation. Consequently, developing decoupling methodologies for these systems carries significant theoretical importance while offering substantial potential for practical engineering applications.

This paper extends the SPITF framework to second-order nonlinear dynamical systems, achieving total decoupling of 2D lattice vibration systems. The work is organized into five sections.

Section 2 develops a mathematical model for 2D lattice vibration systems, with rigorous validation of dynamic properties to ensure analytical soundness.

Section 3 addresses system nonlinearity through linearization, transforming the model into a standard second-order linear ODE system. This transformation represents an essential prerequisite for achieving total decoupling. Building on this foundation,

Section 4 reviews the SPITF framework for decoupling second-order linear dynamical systems, establishing the core methodology for total decoupling of 2D lattice systems. Finally,

Section 5 presents experimental results and corresponding analyses.

2. Model Development

This section addresses vibration analysis in lattice systems within space. Key notations and definitions are first introduced, followed by the development of a mathematical model. Lastly, the model’s validity is verified through dynamic behavior analysis.

Let denote the matrix whenever masses and are connected by a spring with stiffness . We shall use the diagonal element to denote the stiffness of a spring attached solely by the mass to a fixed end but not others. Likewise, let be matrix recording damper linkages. In a sense, both matrices can be considered as adjacency matrices. For each mass , let denote the set of masses linked to by a spring and the set of masses linked to by a damper. We may also assume that the mass is attached to a set of fixed rotational joints at with spring stiffness and damping , . If , then is a free end.

Using vector notation, the following discussion remains valid in higher dimension. It is more convenient to use the position

of the mass

to describe the equation of motion. Assume that the rest position of

is at

. For small deformation, we may assume also that the Hooke’s law is applicable [

29]. Assume additionally that the springs are allowed to move translationally in the direction joining the masses and, thus, involve no angular nor torsional movement. Then the equation of motion is given by the nonlinear differential system

The first two terms are the linear damping and elastic restoring forces between mass

and fixed point

, whereas the latter two are the corresponding forces between masses

and

, with both pairs generated by dampers and springs, respectively. It is important to note that the system might have additional equilibrium points. An equilibrium point of the system (

3) necessarily satisfies the system of equations

which certainly is satisfied by the initial rest position. It is possible that at new equilibrium, the lattice has been distorted and the springs are exerting forces. However, forces from all directions add to zero and, hence, the lattice stays stable.

Suppose that there are

n masses which are linked internally according to the configuration specified by the index subsets

and

, and peripherally by

,

. The total kinetic energy

T is given by

Each spring has a quadratic potential due to the change of its linear length. The total potential energy

P is given by

where we assume that

if

and

are not linked. The total energy within the system is

which is time dependent. we now argue that (

3) is always dissipative in the following sense.

Lemma 1. If damping is present, the total energy of the system (3) decreases. Proof. Out goal is to show that

and is zero only under special circumstances. We first calculate

Terms in the third double sum appear in pairs such as

and

which we can combine into

Likewise, terms in the last double sum appear in pairs such as

and

which we can combine to

we can also calculate

Clearly, every term on the right-hand side is non-negative. So . Further more, unless every term is exactly zero. ☐

Lemma 1 indicates that the nonlinear system (

3) continuously dissipates energy during vibration. The motion ceases when the total energy is depleted, while remaining independent of variations in the original rest positions

, fixed-end points

, positions

, or initial velocity

. Nevertheless, the system is not guaranteed to return to its original rest position. Under certain configurations, alternative equilibrium positions may exist for fixed

and

when the initial velocity is altered. This results from the inherent nonlinear coupling characteristics of lattice vibration systems. This aspect requires further investigation beyond the present scope.

3. Linearized System

To achieve total decoupling of 2D lattice vibration systems using the SPITF framework, the second-order nonlinear system (

3) developed in

Section 2 requires linearization. This process determines the coefficient matrices

,

, and

, thereby enabling the application of SPITF to accomplish decoupling.

The linear system can model the nonlinear system only in the vicinity of an equilibrium point. Assuming that the vibration is tiny, we should be able to consider the linearized system near the rest position [

30]. The linearization is actually an approximation for the displacement vectors

.

Lemma 2. For (3), the first-order approximation of the displacement vector is given by the Proof. It suffices to demonstrate the linearization of the second and fourth summations on the right-hand side of (

3). Rewrite

The actions of the Fréchet derivatives of Equations (

9) and (

10) on

at

are given by

Upon substitution and simplification, we obtain the expression for the summations of the last two terms in (

8). ☐

We can rewrite the Equation (

8) as the standard second-order linear ODE system

except that the coefficient matrices are block structured in a special way. The matrices

,

, and

are respectively the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices. For convenience, denote the matrices

where for each

i, the existence of

depends on the index subsets

and

, respectively; otherwise, they are set to zero matrices. Note all these

matrices are symmetric and positive semi-definite. Note also that

and

. Then

with ⊗ standing for the Kronecker product. For a free-end system,

. With the coefficient matrices

,

, and

now determined, total decoupling of the 2D lattice vibration system can be realized.

4. Total Decoupling

Total decoupling requires a stringent condition than simultaneous diagonalization, specifically the preservation of eigeninformation throughout the decoupling process. The SPITF framework is founded on the Lancaster form [

31]

which enables linearization of the QEP (

2). There must exist a matrix

that performs a congruence transformation on

, such that the structure remains invariant under this transformation [

32], namely

where

,

and

are the coefficient matrices of the total decoupled system and

denotes the invariant spectrum. The implementation procedure is detailed in this section.

The initial coefficient matrices

,

and

of the second-order linear system (

11) are employed to construct the Lancaster structure

Given the symmetry of the matrices defined in Equations (

12)–(14), there exists a one-parameter

transformation

satisfying

where

start from

with

. It means this transformation maintain Lancaster structure for all

t during decoupling, thereby ensuring that

are isospectral to

for any

t.

Differentiate Equation (

18) with respect to the parameter t, we can find

the block matrix

is determined by the following equation

where

are all

matrices. By synthesizing all the information, there are

equations must be satisfied:

We define the matrix

through two free parameter matrices

and

, establishing the parameterization

Clearly,

is an skew-symmetric matrix. The substitution of (

22) into (

19) gives rise to an autonomous differential system

for the matrices

,

, and

, which is independent of the choice of

and

.

For a spring-mass-damper system, since mass properties are generally dominated by diagonal terms in the mass matrix [

27], it is reasonable to approximate

. Throughout the transition, we seek to further ensure that

. By ensuring

, we find that

with

. The structure of flow

is given in the following form

Total decoupling of system (

11) requires appropriate selection of the

-dimensional parameter matrices

and

to govern the transformation flow (

25), thereby generating the spectrum-preserving transformation

. This objective is achieved through the formulation of an open-loop optimal control problem

The control

may be chosen to minimize the deviation between

and

. This reduces to finding the least-squares solution

to problem

Hence, the problem (

26) translates into solving the closed-loop dynamical system

where

stands for the Moore-Penrose generalized inverse of

.

Let

and

denote projection operators such that

and

extract the components of

and

, respectively, that deviate from the specified patterns. To precisely characterize this deviation, we define the operators

and

which set all off-diagonal elements of

and

to zero, respectively. This establishes the formal definition:

The matrices

and

are derived from (

18) as follows:

Define the objective function as:

and

are adjustable weights, where

denotes the Frobenius norm, respectively. This readily yields

Given the skew-symmetry of matrices

and

, their strictly upper triangular components are represented by vectors

and

, respectively, leading to the compact representation:

where

denotes the linear transformation matrix. Consequently, we define

Then, the control vectors

and

are obtained via the least-squares solution of

In summary, the total decoupling of system (

11) is equivalent to solving the initial value problem

5. Numerical Experiments

This section describes three numerical experiments designed to achieve total decoupling of the 2D lattice vibration system. The transformation

is first obtained by numerically solving the initial value problem (

34). Subsequently, this matrix is applied in the congruence transformation (

16) to derive the decoupled system’s coefficient matrices

,

and

. In this context, total decoupling requires that

,

and

attain block-diagonal forms. Specifically, each block in these matrices corresponds to a

submatrix representing an independent single-degree-of-freedom subsystem.

The numerical implementation utilizes Matlab’s ODE15s solvers [

33], which control global error by bounding the local error at each integration step. The InitialStep is set to

with auto_control enabled (control_intensity

). The tolerances AbsTol and RelTol are set to

. Although no rigorous theory currently relates final accuracy to tolerance settings, precision can be enhanced by reducing these tolerances when necessary. This work aims to achieve total decoupling of system (

11). Since

converges to a point

that constitutes a local minimizer of the objective function

, the system is considered decoupled when

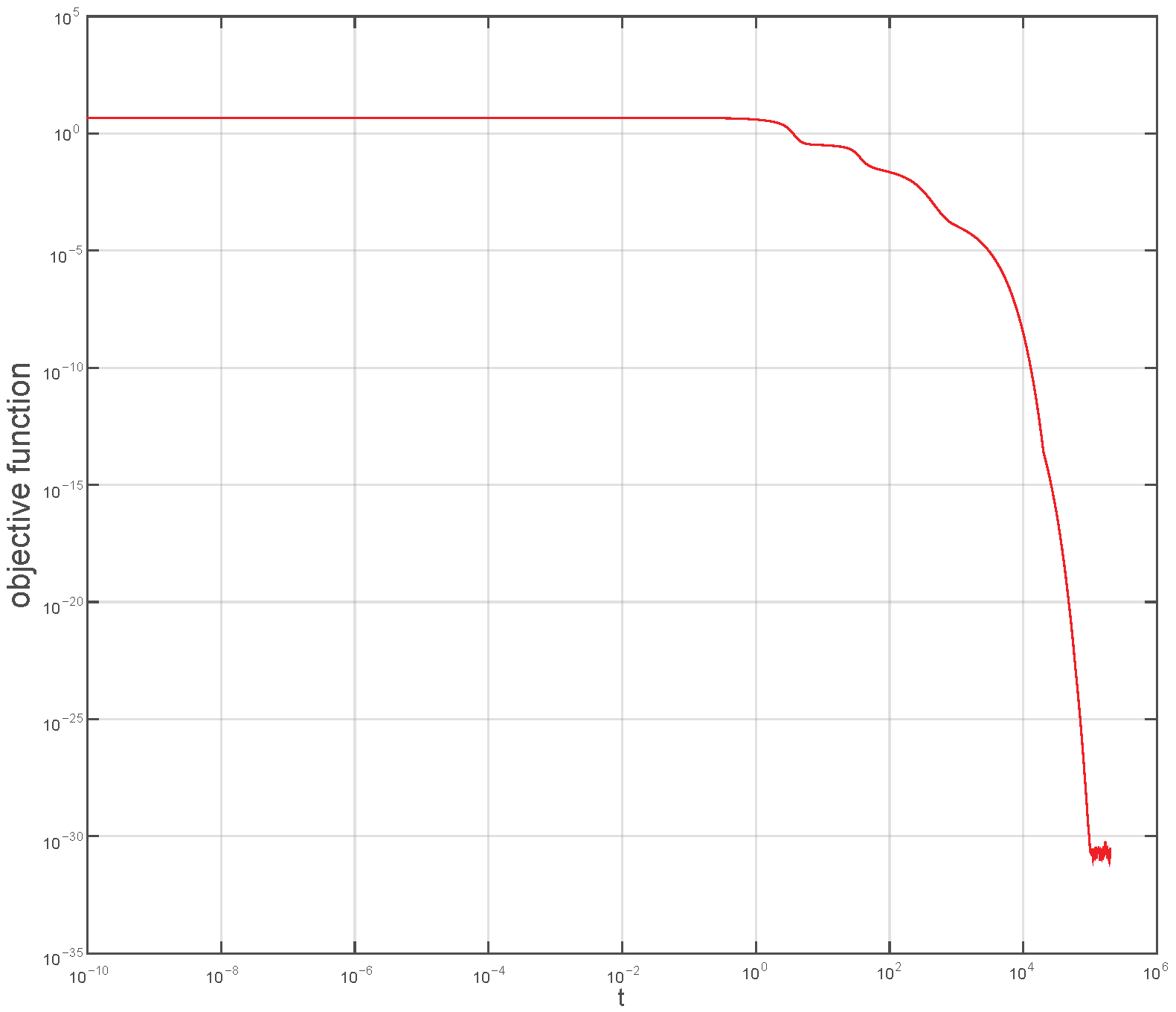

approaches zero within specified tolerance. Numerical results are reported with four significant digits.

Example 1. For a spring-mass-damper system with the configuration shown in Figure 1, we randomly generate a set of coefficient matrices where and The initial damping matrix

and stiffness matrix

exactly follow the structure specified in (

13) and (

14). Numerical integration of (

34) yields a transformation

that drives the objective function (

29) to near-zero values when the iterative computation converges at

. Using this matrix, the decoupled damping matrix

and stiffness matrix

are obtained as follows:

Both matrices and possess a block-diagonal structure composed of blocks, indicating total decoupling into three independent subsystems. The dynamic properties of each subsystem are encoded within their respective block structures.

Figure 3 depicts the evolution of the objective function (

29) during integration. It is evident that

approaches zero when the system achieves total decoupling.

Example 2. We consider a system with a specific triangular configuration where one vertex forms a right angle. First, a set of initial damping and stiffness matrices conforming to the structure shown in (13) and (14) are generated byand . The congruence transformationonce obtained, yields the decoupled coefficient matrices Each

block matrix corresponds to an independent subsystem, and the composite system formed by these three independent subsystems is dynamically equivalent to the undamped system.

Figure 4 presents the variation of the objective function during the integration process. As evidenced by this figure, the system has achieved total decoupling.

Example 3. In this example, we consider a self-adjoint second-order system with These initial coefficient matrices conform to the structures of matrices

and

as defined in

Section 3. While preserving its spectrum

decoupling the system we find damping and stiffness matrices

This decoupling is effected by the transformation

The block-diagonal configuration of matrices and demonstrates total decoupling. Since these subsystems are mutually independent, their dynamic properties can be analyzed separately, providing complete characterization of the initial system’s behavior.

Figure 5 illustrates the evolution of the objective function, concurrently demonstrating the transformation of the coefficient matrices into block-diagonal form during total decoupling.