A Proportional–Integral Observer-Based Dynamic Event-Triggered Consensus Protocol for Nonlinear Positive Multi-Agent Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Formulation and Preliminaries

2.1. Positive System Theory

- (i)

- The system achieves consensus;

- (ii)

- The system satisfies that .

- (i)

- A is a Schur matrix.

- (ii)

- The system exhibits stability.

- (iii)

- There exists a vector such that

- (iv)

- There exists a constant c and a Lyapunov function such that

2.2. Graph Theory

2.3. Problem Formulation

3. Main Results

3.1. Positivity Analysis

3.2. Positive Proportional–Integral Observer

3.3. Dynamic Event-Triggered Observer-Based Control Protocol

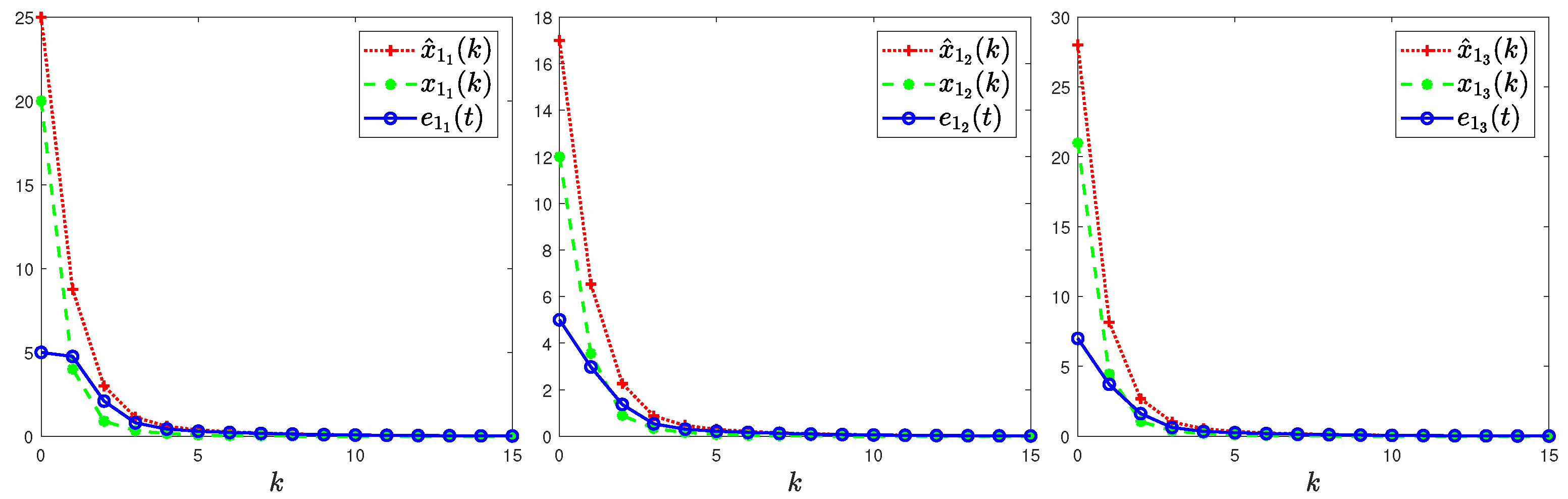

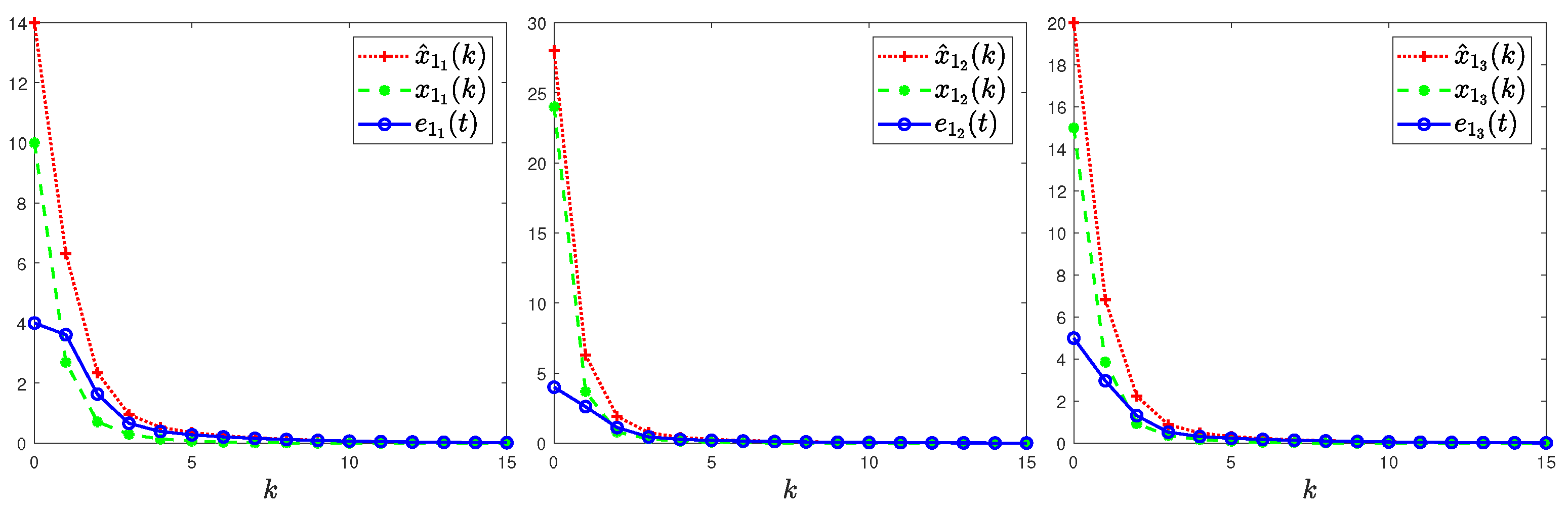

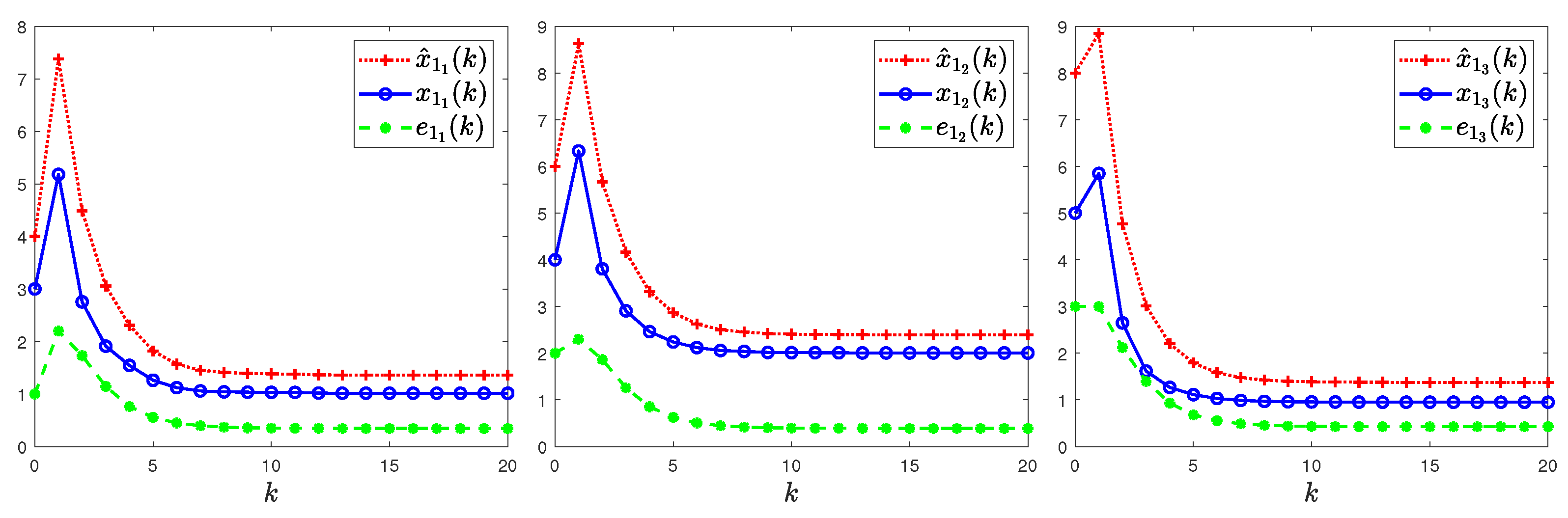

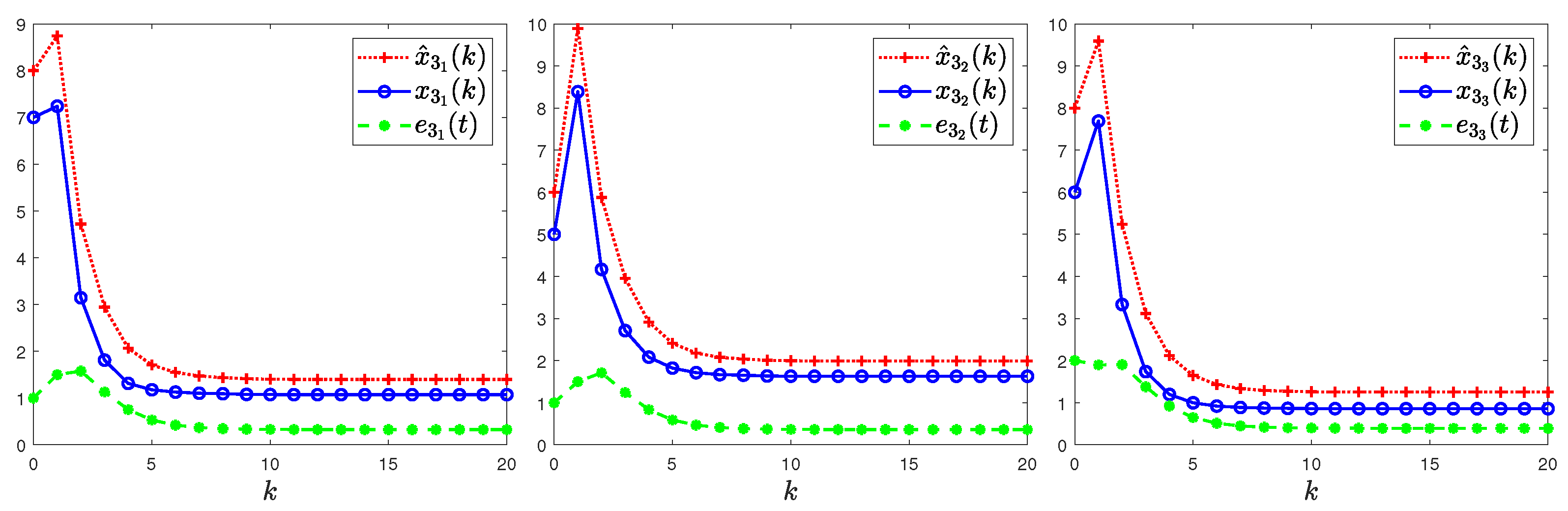

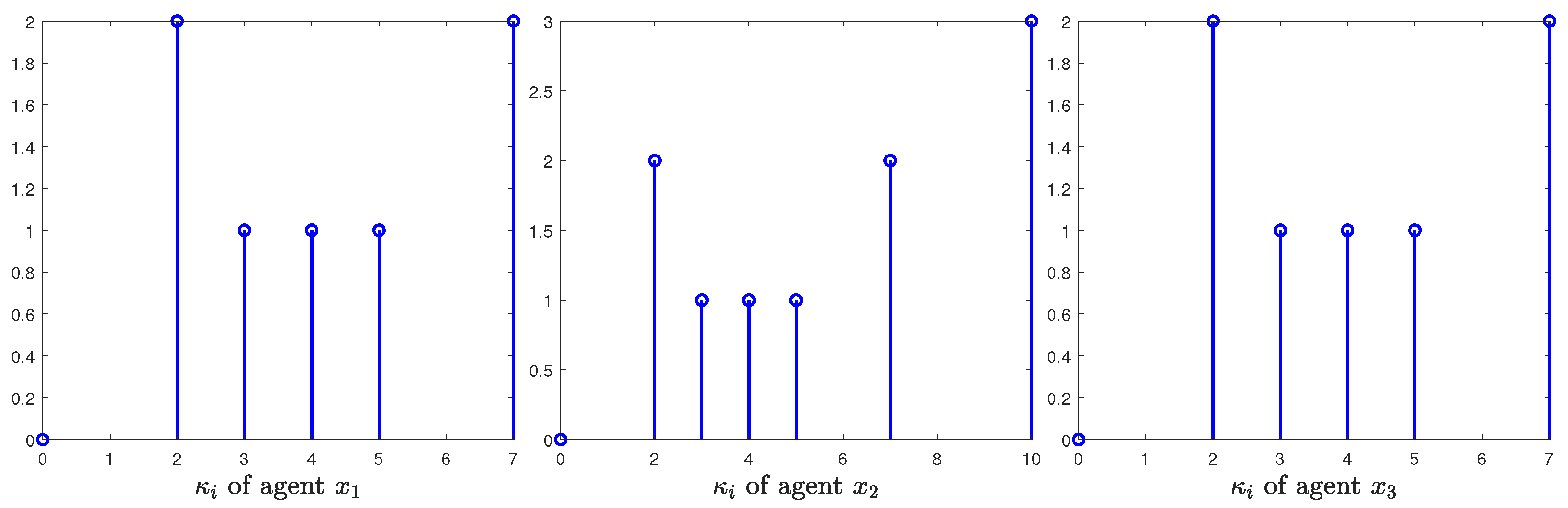

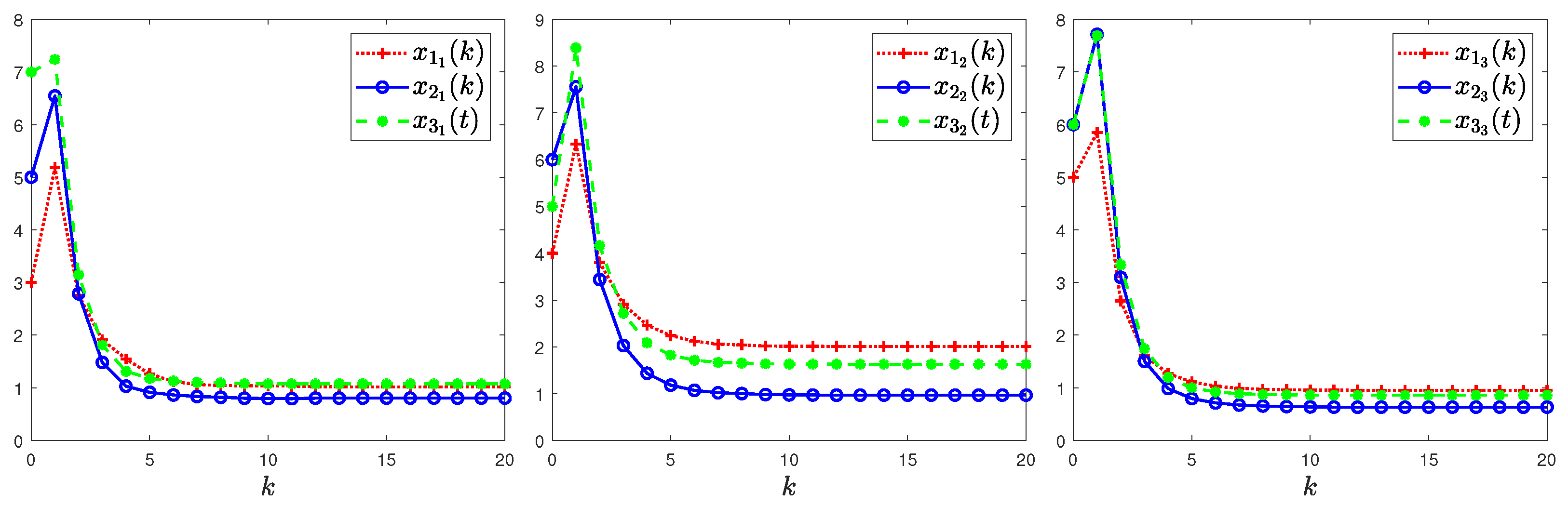

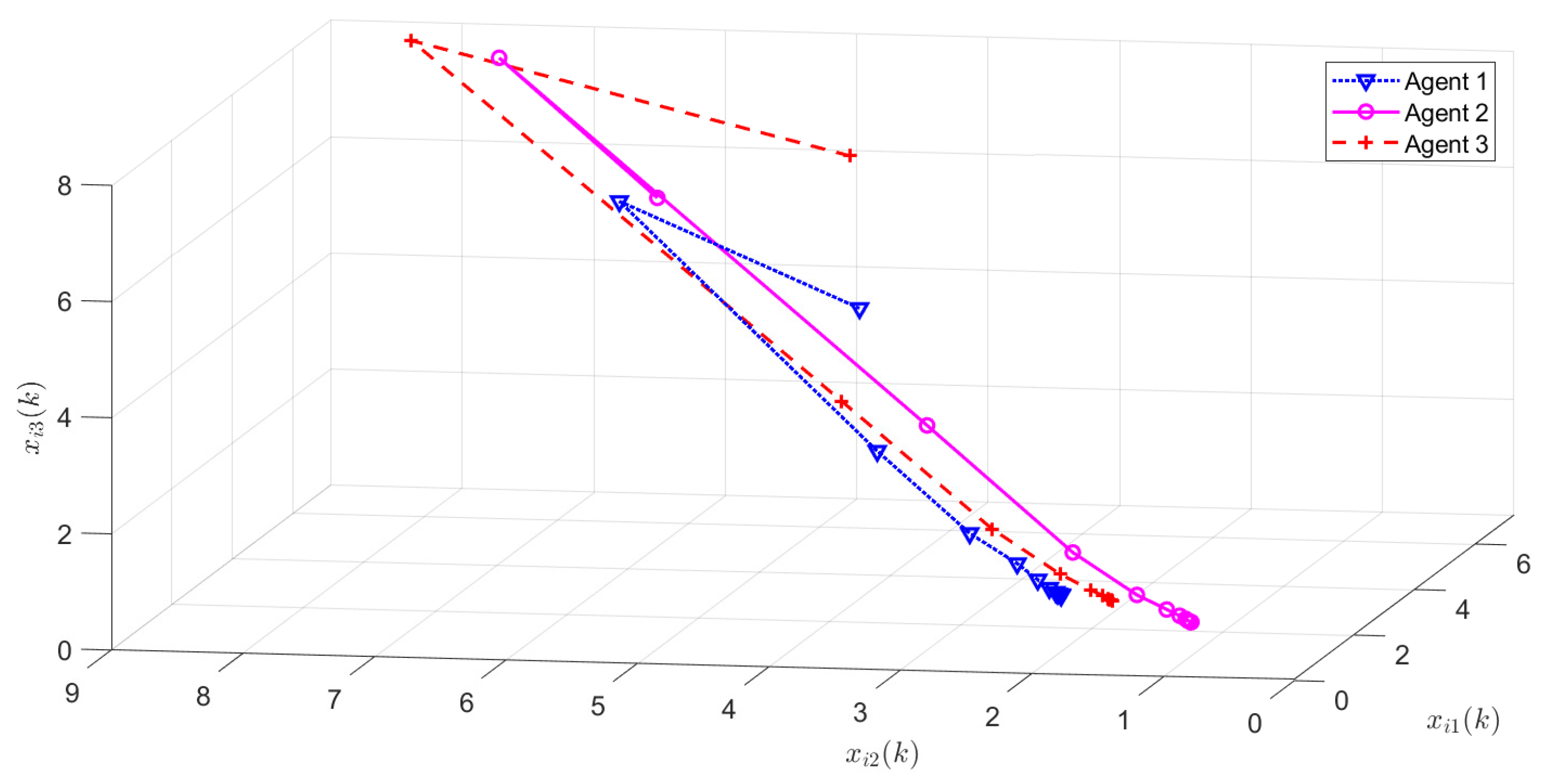

4. Illustrative Examples

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMASs | positive multi-agent systems |

| MASs | multi-agent systems |

| PIO | proportional–integral observer |

Appendix A. Supplementary Steps for (29), (42), (50), and (51) in Theorem 2

Appendix A.1. Additional Details for Step (29)

Appendix A.2. Additional Details for Step (42)

Appendix A.3. Additional Details for Step (50)

Appendix A.4. Additional Details for Step (51)

References

- Cai, J.; Kim, D.; Jaramillo, R.; Braun, J.E.; Hu, J. A General Multi-Agent Control Approach for Building Energy System Optimization. Energy Build. 2016, 127, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, C.O. Multi-Agent Systems Applications in Manufacturing Systems and Supply Chain Management: A Review Paper. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 233–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, M.; Jin, J.; Rahman, A.; Rahman, A.; Wan, J.; Hossain, E. Resource Allocation and Service Provisioning in Multi-Agent Cloud Robotics: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 842–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, S.; Ji, S.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Multi-Agent System Design and Evaluation for Collaborative Wireless Sensor Network in Large Structure Health Monitoring. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 2028–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.; Nayse, S.; Waghmare, L. Application of Wireless Sensor Networks for Greenhouse Parameter Control in Precision Agriculture. Int. J. Wirel. Mob. Netw. 2011, 3, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Atkins, E. Distributed Multi-vehicle Coordinated Control via Local Information Exchange. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2007, 17, 1002–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, M.; Kishida, M.; Lam, J. Geometric Programming for Optimal Positive Linear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 65, 4648–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Li, H.; Ma, H.; Lu, R. Finite-Time Consensus Tracking Neural Network FTC of Multi-Agent Systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Huang, J.; Wang, L. Leaderless Consensus Control of Uncertain Multi-Agents Systems with Sensor and Actuator Attacks. Inf. Sci. 2019, 505, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, B.; Han, Q.L.; Qian, F.; Kurths, J.; Cao, J. Leader-Following Consensus of Nonlinear Multiagent Systems With Stochastic Sampling. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, C. Distributed Event-Triggered Consensus of General Linear Multiagent Systems Under Directed Graphs. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Cluster-Delay Consensus in First-Order Multi-Agent Systems with Nonlinear Dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016, 83, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, G.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Y. Event-Triggered State-Feedback and Dynamic Output-Feedback Control of Positive Markovian Jump Systems with Intermittent Faults. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 68, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemels, W.; Johansson, K.; Tabuada, P. An Introduction to Event-Triggered and Self-Triggered Control. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 51st IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Maui, HI, USA, 10–13 December 2012; pp. 3270–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johan Åström, K.; Bernhardsson, B. Comparison of Periodic and Event Based Sampling for First-Order Stochastic Systems. IFAC Proc. Vol. 1999, 32, 5006–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, A.; Bosch, R. Comparison of Event-Triggered and Time-Triggered Concepts with Regard to Distributed Control Systems. Embed. World 2004, 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Tabuada, P. Event-Triggered Real-Time Scheduling of Stabilizing Control Tasks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2007, 52, 1680–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Feng, G.; Wang, Y.; Song, C. Distributed Event-Triggered Control of Multi-Agent Systems with Combinational Measurements. Automatica 2013, 49, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Huang, C. Output Consensus of Heterogeneous Linear Multiagent Systems With Directed Graphs via Adaptive Dynamic Event-Triggered Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 4606–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.X. Event-Triggered Output Feedback Consensus Tracking Control for Nonlinear Multiagent Systems with Sensor Failures. Automatica 2023, 148, 110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luenberger, D. An Introduction to Observers. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1971, 16, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Huang, J. A Distributed Observer for a Class of Nonlinear Systems and Its Application to a Leader-Following Consensus Problem. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2019, 64, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Liu, X.; Gao, X.; Wei, X. Intermediate Observer-Based Robust Distributed Fault Estimation for Nonlinear Multiagent Systems with Directed Graphs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 7426–7436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Hua, C.; You, X.; Guan, X. Finite-Time Observer-Based Leader-Following Consensus for Nonlinear Multiagent Systems with Input Delays. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 5850–5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafai, B.; Carroll, R. Design of Proportional-Integral Observer for Linear Time-Varying Multivariable Systems. In Proceedings of the 1985 24th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 11–13 December 1985; pp. 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.G.; Duan, G.R. Design of Generalized PI Observers for Descriptor Linear Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Regul. Pap. 2006, 53, 2828–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, D. Unknown Input Proportional Multiple-Integral Observer Design for Linear Descriptor Systems: Application to State and Fault Estimation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Luo, D. Battery States Online Estimation Based on Exponential Decay Particle Swarm Optimization and Proportional-Integral Observer with a Hybrid Battery Model. Energy 2020, 191, 116509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wei, G. Proportional–Integral Observer Design for Multidelayed Sensor-Saturated Recurrent Neural Networks: A Dynamic Event-Triggered Protocol. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 4619–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Liang, L.; Yan, H.; Cao, J.; Tang, S.; Shi, K. Proportional-Integral Observer-Based State Estimation for Markov Memristive Neural Networks With Sensor Saturations. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczorek, T. Positive 1D and 2D Systems; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, L.; Rinaldi, S. Positive Linear Systems: Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 50. [Google Scholar]

- Godsil, C.; Royle, G. Algebraic Graph Theory; Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Beard, R. Consensus Seeking in Multiagent Systems under Dynamically Changing Interaction Topologies. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Francis, B.; Maggiore, M. Necessary and Sufficient Graphical Conditions for Formation Control of Unicycles. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Cheng, J.; Cao, J.; Wu, Z.G.; Chen, W.H. Proportional–Integral Observer-Based State Estimation for Singularly Perturbed Complex Networks With Cyberattacks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 9795–9805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Z.; Lam, J.; Gao, H.; Du, B.; Wu, L. Positive Observers and Dynamic Output-Feedback Controllers for Interval Positive Linear Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Regul. Pap. 2008, 55, 3209–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Huang, M.; Wu, Y.; Tan, X. A Proportional–Integral Observer-Based Dynamic Event-Triggered Consensus Protocol for Nonlinear Positive Multi-Agent Systems. Axioms 2024, 13, 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms13060384

Yang X, Huang M, Wu Y, Tan X. A Proportional–Integral Observer-Based Dynamic Event-Triggered Consensus Protocol for Nonlinear Positive Multi-Agent Systems. Axioms. 2024; 13(6):384. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms13060384

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiaogang, Mengxing Huang, Yuanyuan Wu, and Xuegang Tan. 2024. "A Proportional–Integral Observer-Based Dynamic Event-Triggered Consensus Protocol for Nonlinear Positive Multi-Agent Systems" Axioms 13, no. 6: 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms13060384

APA StyleYang, X., Huang, M., Wu, Y., & Tan, X. (2024). A Proportional–Integral Observer-Based Dynamic Event-Triggered Consensus Protocol for Nonlinear Positive Multi-Agent Systems. Axioms, 13(6), 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms13060384