Abstract

Based on equivalence relation R on X, equivalence class of a point and equivalence class of a subset represent the neighborhoods of x and A, respectively. These neighborhoods play the main role in defining separation axioms, metric spaces, proximity relations and uniformity structures on an approximation space depending on the lower approximation and the upper approximation of rough sets. The properties and the possible implications of these definitions are studied. The generated approximation topology on X is equivalent to the generated topologies associated with metric d, proximity and uniformity on X. Separated metric spaces, separated proximity spaces and separated uniform spaces are defined and it is proven that both are associating exactly discrete topology on X.

Keywords:

approximation space; rough set; separation axioms; metric spaces; proximity relations; uniform structures MSC:

03E02; 03E20; 54D010; 54D15; 54E35; 54E05; 54E15

1. Introduction

Originally, Pawlak in [1] initiated the notions of lower approximation set and upper approximation set of subset A of universal set X depending on the equivalence classes formed by equivalence relation R on X. The pair is then called an approximation space. From the set difference, , a boundary region area is formed and is called the boundary region set . Any subset in is then a rough set (whenever ) or an exact set (whenever ). The importance of this boundary region set is in its role in many real applications; refs. [2,3] are samples of research work of such applications. Decision Theory and Data Mining are the most intercept branches with the concept of rough sets. Yao in [4,5] extended the research work on rough sets and explained the algebraic properties of rough sets. Some researchers paid their attention to the approximation spaces constructed by an arbitrary (not equivalence) relation R on X. As an example, ref. [6] objected to the effects on the notion of rough sets by reflexive relations or transitive relation or both. Generating approximation topology associated with is explained well in [7,8], whenever is constructed by arbitrary relation R on X. Then, we obtain left approximation neighborhoods and right approximation neighborhoods at each point . That is, the notion of rough sets has a generalized form (as found in [4,9]) in which the definition of Pawlak is a special case. Kozae, in [10], introduced a generalization of rough sets using the intersection of left and right approximation neighborhoods and , respectively, at point . The resulting rough sets (in [10]) have fewer boundary region sets than those defined in [1,4,9], and so it is a good generalized definition. Following that generalized definition in [10], Ibedou et al. [11,12] introduced two types of generalizations of rough sets in the fuzzy case. Also, in this paper, we follow the same strategy. For all basics in general topology, please refer to [13,14,15].

The aim of this paper is to construct a proximity relation and a uniformity structure on an approximation space , and also define a metric function and separation axioms based on the rough sets in . In Section 2, we present (in the sense of Pawlak) some basics of rough sets and introduce the definitions of separation axioms in . In Section 3, we focus on defining metric d on approximation space and study its usual properties. In Section 4, we define proximity relation on and study its properties. In Section 5, we define a uniform structure , similar to that defined in [16], on . We study the relations in between notion separation axioms in , metric spaces , proximity spaces and uniform spaces based on the rough sets defined by an equivalence relation R on X. Finally, in Section 6, we explain the deviations in these notions whenever R is not an equivalence relation on X.

2. Preliminaries

Throughout the paper, we let X be a universal set of objects, let be the power set of X and let denote the set of all characteristic functions on X. Then, in the set theory, it is well known that there is a one-to-one correspondence between and . Thus, we use subset A and characteristic function A without distinction.

Relation R on X is mapping defined by the following: for any

R is called an equivalence relation on X if it satisfies the following conditions:

- (1)

- R is reflexive, that is, for all we have ,

- (2)

- R is symmetric, that is, for any ,

- (3)

- R is transitive, that is, for any ,

where

The pair is called an approximation space (see [1]).

The equivalence relation R is partitioning X into equivalence classes for each , where an equivalence class is mapping defined, for each , as follows:

Then, for any , we have

and moreover, and are disjointed:

Now, for each , the equivalence class of A is defined by

Then, that is,

For each and each , we have and , respectively, and these equivalence classes, and , are called the neighborhoods of x and A, respectively.

In general, let us define an equivalence class as follows:

Remark 1.

For where A which is not a singleton or B is not a singleton, we have but not the converse. For example, we let , , , . Then, , . That is, while . Thus, for non-singleton sets, may be found but are not identical as the case with two singletons. and implies , and in general , . Moreover, implies . We recall that

Lemma 1.

For any , the following properties are fulfilled:

- (1)

- implies ,

- (2)

- ,

- (3)

- implies , while implies ,

- (4)

- If , then there is such that and .

Proof.

- (1)

- This is easily proven using Remark 1.

- (2)

- is clear. Now, we let . Then, there is such that ; that is, there is or such that . Thus, or . So, ; that is, . Hence, .

- (3)

- implies ; that is, , while implies that .

- (4)

- The proof is straightforward.

□

Based on the meaning of neighborhoods , the lower and the upper approximations of any subset of X were defined. For subset A of X, we define approximation subsets using

Lemma 2.

If is an approximation space with R an arbitrary relation on X, then, for any

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- implies that

Proof.

The proof is direct. □

Whenever R is reflexive, for any we have ,

If R is also transitive, . For any subset A of X, the lower approximation and the upper approximation are defined by

The boundary region set is defined by the set difference, , and moreover, the accuracy value of rough set A is given by the ratio

Whenever , is not empty and set A has a roughness region. Thus, A is called a rough set. As a special case, if . Then, , and A is called a totally rough set. However, if , then , and set A is called an exact set.

From Lemma 2 and the definitions of and , we have the following consequences.

Lemma 3.

Let be an approximation space with R as an arbitrary relation. Then, for any , the following properties are fulfilled:

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- implies that

Proof.

The proof is straightforward from Lemma 2. □

Note that if R is a reflexive relation, the equality holds in (5), Lemma 3, and moreover, if R is a transitive relation, the equality holds in (3), Lemma 3. Thus, we can deduce that approximation topology on approximation space is associated, for each , with the interior and the closure defined by and .

Now, we recall two operators on X and both operators generate topologies on X, respectively (both are dual).

Mapping is called a closure operator on X (see [14]) if it satisfies the following conditions: for any

(C.1)

(C.2)

(C.3)

(C.4)

Mapping is called an interior operator on X (see [14]) if it satisfies the following conditions: for any

(I.1)

(I.2)

(I.3)

(I.4)

Lemma 4

([14]). Let c be a closure operator on X. Then, topology is generated on X such that for each , where is the closure of A with respect to topology . In fact,

Lemma 5

([14]). Let i be an interior operator on X. Then, topology is generated on X such that for each , where is the interior of A with respect to topology . In fact,

We let be an approximation space. We define mappings , respectively, for each as follows:

Then, from Lemma 3, we can easily check that i is an interior operator and c is a closure operator on X. Thus, by Lemmas 5 and 4, there are topologies and on X such that and for each . Furthermore, we have and . So, , and we denote both of the topologies by . Hence, we consider approximation space as the topological space equipped with the interior operator defined by (4) or the closure operator defined by (5). Moreover, the generated topology on X is given by

Since , . Also, since , . In general, each with is an open and closed set in . That is, , and then A is an exact set. That means no roughness of A.

Example 1.

Let and . Then,

(1) If or . Then, obtain

(2) If or . Then, obtain

(3) Since , and , the lower approximation and the upper approximation of any of these subsets are equal, , and then only subsets are exact sets and the other four non-empty subsets are rough sets.

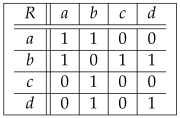

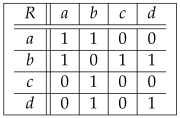

Example 2.

Let and . Then, have

(1) If , and . Thus, these subsets are totally rough sets.

(2) If , and .

(3) If , and .

(4) If , and .

(5) If , and . These subsets appearing in he previous items (2)–(5) are rough sets.

(6) If , determine that the lower approximation and the upper approximation of any of these subsets are equal, that is, . Thus, these subsets are exact sets without roughness.

Example 3.

Let and . Then, have

(1) If , and These subsets are rough sets. Moreover, the boundary set is , and the accuracy is .

(2) If , and . These subsets are rough sets. Moreover, the boundary set is , and the accuracy is .

(3) If , . These non-empty subsets are exact sets. Moreover, the boundary set is , and the accuracy is 1.

Example 4.

Let be a finite approximation space such that for all (only equal elements are related). Then, for each . Thus, any subset A of X is open and closed, that is, for all , and hence the boundary set is ∅. So, each is an exact subset of X without roughness.

Definition 1.

An approximation space is said to be

(i) a -space if for all , then for all or for all ,

(ii) a -space if for all , then for all for all , that is, ,

(iii) a -space if for all , then ,

(iv) regular if for all , then for all for all , that is, ,

(v) a space if it is regular and ,

(vi) normal if for all with , for all for all , that is, ,

(vii) a space if it is normal and .

Remark 2.

- (1)

- Suppose is a -space and let . Then, either or . Thus, every approximation space cannot be a -space except for all .

- (2)

- is a -space if and only if for all if and only if for all from Equation (5).

- (3)

- It is obvious that , and separation axioms are equivalent definitions in an approximation space .

Proposition 1.

From Definition 1, .

3. Metric Distance in Approximation Spaces

Let be a mapping satisfying the following conditions:

- (D1)

- implies that ,

- (D2)

- for all ,

- (D3)

- for all ,

- (D4)

- implies that .

d is called a metric on X if mapping d satisfies only conditions (D1)–(D3). Then, d is called a pseudo-metric on X if d satisfies only conditions (D1), (D3). Then, d is called a quasi-pseudo-metric on X, and if d satisfies only conditions (D1), (D3), (D4), d is called a quasi-metric on X.

Let be an approximation space with an equivalence relation R on X and a mapping defined as a relation on X in the following way:

From (6), it is obvious that implies . Since , . Also, it is clear that . On the other hand, if , then, clearly, but Thus, d defines a pseudo-metric on X. In this case, the pair is called a pseudo-metric space induced by and we write the topology on X induced by d or associated to d as . The pair is the associated topological space.

It is clear that there is a distance between x and y in X if and only if .

For each and each , the distance between x and A, denoted by , is defined as follows:

which is equivalent to

For any , the distance between A and B, denoted by , is defined as follows:

which is equivalent to

Thus, from Equations (4) and (5), obtain

where and denote the interior and the closure of A with respect to topology , respectively. So, it can easily be seen that

Pseudo-metric d on the approximation space is a metric on X, if implies , that is, for all . The associated topological space proves that it is a normal topological space. Based on the definition of a metric d, and that R is given by for all , otherwise , is a space. Thus, is a space, which means satisfying all the separation axioms; . Recall that in this case is exactly a discrete topological space, i.e., all subsets are open and closed. Moreover, Equations (7) and (8) could be rewritten as

Proposition 2.

Let be a pseudo-metric space and let be the topology associated to d. Then, is a normal space. Moreover, if d is a metric, then is a space.

Proof.

We suppose d is a metric on X. From Equation (6), we determine that if if , and then and . Hence, is a space.

We let , with . Then, we have

Thus, and . We assume that say, . Then, there exist and such that and . Thus, . So, and and both are contradictions. Hence, . Therefore, is normal. □

4. Proximity Relation in Approximation Spaces

Binary relation on is called a nearness relation or a proximity on X, provided that the negation of , denoted by (called a farness relation), for any , fulfills the following conditions (see [15]):

(P1) implies ,

(P2) if and only if and ,

(P3) or implies ,

(P4) implies ,

(P5) if . Then, there is such that and .

The pair is called a proximity space. Note that is the negation of , that is, .

(P1) and (P2) imply the following condition:

(P2′) if and only if and .

In the following proposition, we show that there is a proximity on an approximation space .

Proposition 3.

Let be an approximation space and let δ be a binary relation on defined, for any , as follows:

Then, δ is a proximity on X. In this case, δ is called a proximity on X induced by R and the pair is called a proximity space of

Proof.

(P1) Suppose for any . Then, by the definition of , Thus, . So, by Lemma 1 (3), . Hence, .

(P2) Suppose for any Then, clearly, Thus, by Lemma 1 (2), that is, So, and . Hence, and .

Conversely, suppose and . Assume that , that is, . Then, there is and for some . Thus, for some or . So, or , that is, or . Both are contradicting and . Hence, .

(P3), (P4) The proofs are straightforward.

(P5) Suppose for any Then, clearly, , that is, . Thus, there is such that . Thus, and , which is equivalent to there is such that and . □

Let be a proximity on an approximation space . Consider two mappings, defined, for each respectively, as follows:

and

Then, it can easily be checked that is an interior operator and a closure operator on X. Thus, by Lemmas 4 and 5, there is topology (called the topology associated to) on X. In fact,

The pair is the associated topological space to . It is obvious that .

Proximity on approximation space is said to be separated if implies . It is obvious that is a separated proximity if and only if for all , that is, is a -space if and only if the pseudo-metric d is a metric.

In the following Proposition, it is proven that topological space associated to proximity space is a space.

Proposition 4.

Let be the proximity space for an approximation space and let be the topology associated to δ. Then, is a normal space. Moreover, if δ is separated, is a space.

Proposition 5.

Let be a topological approximation space. Then, the constructed proximity δ on X fulfills, for any the following property:

Proof.

From conditions (P1), (P2), . Also, . □

Let be the pseudo-metric space induced by an approximation space . Then, we can define proximity on X in the following way: for any

It is easy to see that satisfies Conditions (P1)–(P5) depending on the properties of the pseudo-metric d. Moreover, if d is a metric on X, is a separated proximity on X. Thus, the resulting interior operators and closure operators in both of and (as shown in Equations (11)–(14)) generate equivalent topologies and . So, both of them are equivalent to discrete topology generated on X. Hence, all subsets of X have identical lower approximations and upper approximations.

In this case,

5. Uniform Structure in Approximation Spaces

In this section, we study the relation between the uniform spaces and the separation axioms given in Section 2, the defined pseudo-metric in Section 3 and the defined proximity in Section 4.

For a non-empty set X, the top relation and the bottom relation on X, denoted by and , are relations on X, respectively, defined, for any , as follows:

denotes the bounded set of all relations on X.

For each the inverse relation of R, denoted by , is a relation on X defined, for any , as follows:

Binary operations ∧ and ∨ on between arbitrary relations are defined, for any and any by

For any the composition of and , denoted by , is a relation on X defined as follows: for any ,

The order relation ≤ on is defined, for any and by

Definition 2.

Filter on is mapping satisfying the following conditions:

(i) , ( to be a proper filter),

(ii) implies for all ,

(iii) for all .

The inverse of is defined by for all .

The principal filter on of a pair in is defined, for each by

It is clear that for all . Then, where denotes the set of all reflexive relations on X.

For any two filters and , we say that is finer than , denoted by , if for each

Definition 3.

Let and be two filters on such that and for any Then, the composition of and , denoted by , is a filter on defined, for each by

The notion of uniformity was introduced by Weil in [15]. Here, we construct a uniform structure in an approximation space .

Definition 4.

Uniformity on X is a filter on satisfying the following conditions:

(U1) for all ,

(U2) ,

(U3) .

The pair is called a uniform space.

From the above definition, we can easily see that , where denotes the set of all equivalence relations on X.

Definition 5.

Let be a filter on such that for all and let be a filter on X. Then, the image of with respect to , denoted by , is the mapping defined in [16], for each and each by

where , and set is defined so that

From Equation (1), determine that for all .

It is obvious that is a filter on X.

The principal filter on X at a point is defined by for all . It is clear that for all .

Let be a uniformity on a set X and let be the mappings defined, respectively, as follows: for each , any and each :

Then, it can easily be proven that and are the interior and the closure operators on X, respectively. Thus, there is topology on X induced by or .

Since any equivalence relation R on X is an element of a uniformity on X, in an approximation space , from Equations (4) and (5), obtain

and

Uniformity on X is said to be separated, if for all there is such that and , that is, . In this case, pair is called a separated uniform space.

As in Section 2, as separation axioms. So, separated uniform spaces satisfy all these axioms.

Generated topology on approximation space is explained during the lower and the upper sets of a rough set. It is equivalent to induced topology generated by constructed proximity on X, and also is equivalent to the generated topology by pseudo-metric d constructed on X. Moreover, all these topologies are equivalent to generated topology the constructed uniformity on X. According to the definitions of a metric, a separated proximity and a separated uniformity, obtain a similar result to Proposition 2 and Proposition 4 related to the defined separation axioms in Section 2.

Proposition 6.

Let X be a set, a uniform structure on X and the topology induced by . Then, is a normal space, and moreover

6. Arbitrary Relation in Approximation Spaces

In this section, we recall the strategy of Kozae in [10]. We let R be an arbitrary relation on X. Then, the right and left neighborhoods (the after and fore sets) of element are sets in given, respectively, by

We let be defined as

and be defined as

are called minimal right neighborhoods and minimal left neighborhoods of ;

is called the minimal neighborhood of .

For any subset A of X, the lower approximation and the upper approximation are defined by where

The resulting lower and upper approximation sets of set A are typically those defined by Kozae in [10]. The interior operator and the closure operator defined, respectively, in Equations (4) and (5) did not satisfy the common properties of interior and closure operators to generate a topology on . In the case R is a reflexive relation, , but this is still not sufficient to generate a topology on . At least, in Equations (4) and (5), R needs to be reflexive and transitive to produce topology on . In the case R is an equivalence relation, the well-known definition of Pawlak [1] is obtained, and Equations (4) and (5) define topology on X.

In the case R is an arbitrary relation on , the separation axiom could be satisfied and the separation axiom is not satisfied. That is, the given equivalence in Section 2 is not correct.

Remark 3.

Whenever R is arbitrary relation on X, we have to replace with in all the notations introduced in Section 2, Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5. If R is not reflexive, it may be , that is, . Hence, condition (D1) is not satisfied and we can not build pseudo-metric d on according to Equation (6). According to Equation (13), we may have which is a contradiction to condition (P4), and then we cannot build proximity δ on . Also, condition (U1) is not satisfied, and so construction of uniformity on is not possible. If R is not symmetric, Conditions (D2), (P1) and (U2) are not satisfied, and thus it fails to build a metric (pseudo-metric), a proximity or a uniformity in , but it could be a quasi-metric (quasi-pseudo-metric), a quasi-proximity or a quasi-uniformity in . Also, if R is not transitive, Conditions (D3), (P5) and (U3) are not satisfied, and thus it fails to build any of metric (pseudo-metric), proximity or uniformity in .

Examples 1–4 are given for equivalence relations. Now, we offer an example of arbitrary relation R on X.

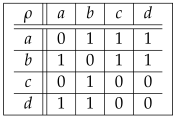

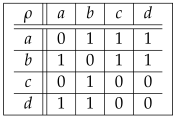

Example 5.

Let R be a relation on set as shown below.

, , , and , , , . Then, , , , and , , , and then, , , , .

(1) For subset , we compute as follows: , , and thus , and the accuracy value is .

(2) For subset , we compute as follows: , and then , and thus , and the accuracy value is .

(3) For subset we have , , and thus , and the accuracy value is .

From Remark 3, we determine that , and thus this example cannot satisfy any axiom of the separation axioms as given in Definition 1.

Also, from computed in this example, we can deduce function ρ (neither a metric nor a pseudo-metric) as follows:

7. Conclusions

This aim of paper was to construct a proximity relation and a uniformity structure on approximation space and also define metric function and separation axioms based on the rough sets in . We presented some basics of rough sets and introduced the definitions of separation axioms in . We focused on defining metric d on approximation space and studied its usual properties. We defined proximity relation on and studied its properties. Following the definition of uniformity structure introduced by Gahler on , we studied the relations in between notion separation axioms in , metric spaces , proximity spaces and uniform spaces based on the rough sets defined by an equivalence relation R on X. At last, we explained the deviations in these notions whenever R is not an equivalence relation on X. In a future work, we will discuss these results and their applications in the fuzzy approximation spaces, the soft approximation spaces and the soft fuzzy approximation spaces.

Author Contributions

Methodology and Funding, J.I.B.; Validation and Formal analysis, K.H. and J.I.B.; Investigation, S.E.A. and I.I.; Resources, I.I. and J.I.B.; Writing-original draft, I.I. and S.E.A.; Reviewing the final form, I.I. and K.H.; Visualization, I.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was partially supported by Wonkwang University in 2023.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewer for his encouragement and valuable suggestions for improving this paper. The authors would like to thank Wonkwang University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pawlak, Z. Rough Sets. Int. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1982, 11, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bably, M.K.; Al-Shami, T.M. Different kinds of generalized rough sets based on neighborhoods with a medical application. Int. J. Biomath. 2021, 14, 2150086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bably, M.K.; Abo-Tabl, E.A. A topological reduction for predicting of a lung cancer disease based on generalized rough sets. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 41, 3045–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.Y. Two views of the theory of rough sets in finite universes. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 1996, 15, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.Y. Constructive and Algebraic methods of the theory of rough sets. Inf. Sci. 1998, 109, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Yang, J.; Pei, Z. Generalized rough sets based on reflexive and transitive. Inf. Sci. 2008, 178, 4138–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuchro, M. On rough sets in topological Boolean algebra. In Rough Sets, Fuzzy Sets and Knowledge Discovery; Ziarko, W., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Z.; Pei, D.; Zheng, L. Topology vs. generalized rough sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2011, 52, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, A.A.; Bakeir, M.Y.; Abo-Tabl, E.A. New approach for basic rough set concepts. In International Workshop on Rough Sets, Fuzzy Sets, Data Mining and Granular Computing; Lecture notes in artificial intelligence 3641; Springer: Regina, Canada, 2005; pp. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kozae, A.M.; El-Sheikh, S.A.; Hosny, M. On generalized rough sets and closure spaces. Int. J. Appl. Math. 2010, 23, 997–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Alsulami, S.H.; Ibedou, I.; Abbas, S.E. Fuzzy roughness via ideals. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 39, 6869–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibedou, I.; Abbas, S.E. Generalization of rough fuzzy sets based on a fuzzy ideal. Iran. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 20, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Csaszar, A. General Topology; Akade´miai Kiado´: Budapest, Hungary, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Pervin, W.J. Foundations of General Topology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, A. Sur les Espaces à Structures Uniformes et Sur la Topologie Générale; Hermann: Paris, France, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Gähler, W.; Bayoumi, F.; Kandil, A.; Nouh, A. The theory of global L-neighborhood structures, (III), Fuzzy uniform structures. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1998, 98, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).