Abstract

In this paper, we present and justify a methodology to solve the Monge–Kantorovich mass transfer problem through Haar multiresolution analysis and wavelet transform with the advantage of requiring a reduced number of operations to carry out. The methodology has the following steps. We apply wavelet analysis on a discretization of the cost function level j and obtain four components comprising one corresponding to a low-pass filter plus three from a high-pass filter. We obtain the solution corresponding to the low-pass component in level denoted by , and using the information of the high-pass filter components, we get a solution in level j denoted by . Finally, we make a local refinement of and obtain the final solution .

MSC:

42C40; 49Q20; 65T60

1. Introduction

In recent years, schemes to approximate infinite linear programs have become very important in theory. The authors of [1] showed that under suitable assumptions, the program’s optimum value can be approximated by the values of finite-dimensional linear programs and that every accumulation point of a sequence of optimal solutions for the approximating programs is an optimal solution for the original problem. In particular, in [2] the authors studied the Monge–Kantorovich mass transfer (MT) problem on metric spaces. They considered conditions under the MT problem as solvable and, furthermore, that an optimal solution can be obtained as the weak limit of a sequence of optimal solutions to suitably approximate MT problems.

Moreover, in [3], the authors presented a numerical approximation for the value of the mass transfer (MT) problem on compact metric spaces. A sequence of transportation problems was built, and it proved that the value of the MT problem is a limit of the optimal values of these problems. Moreover, they gave an error bound for the numerical approximation. A generalization of this scheme of approximation was presented in [4,5]. They proposed an approximation scheme for the Monge–Kantorovich (MK) mass transfer problem on compact spaces that consisted of reducing to solve a sequence of finite transport problems. The method presented in that work uses a metaheuristic algorithm inspired by a scatter search in order to reduce the dimensionality of each transport problem. Finally, they provided some examples of that method.

On the other hand, the authors of [6] provided orthonormal bases for that have properties that are similar to those enjoyed by the classical Haar basis for . For example, each basis consists of appropriate dilates and translates of a finite collection of “piecewise constant” functions. The construction is based on the notion of multiresolution analysis and reveals an interesting connection between the theory of compactly supported wavelet bases and the theory of self-similar tilings. Recent applications of the wavelet filter methodology have been used in various problems arising in communication systems and detection of thermal defects (see, for example, [7,8], respectively).

In [9], the authors gave a scheme to approximate the MK problem based on the symmetries of the underlying spaces. They took a Haar-type MRA constructed according to the geometry of the spaces. Thus, they applied the Haar-type MRA based on symmetries to the MK problem and obtained a sequence-of-transport problem that approximates the original MK problem for each MRA space. Note that in the case of Haar’s classical wavelet, this methodology coincides with the methods presented in [2,3].

It is important to note that various scientific problems are modeled through the Monge–Kantorovich approach; therefore, providing new efficient methodologies to find approximations of such problems turns out to be very useful. Within the applications of problems whose solutions are the Monge–Kantorovich problem are found: the use of the transport problem for the analysis of elastic image registration (see, for example, [10,11,12]). Other optimization problems related to this topic and differential equation tools can be found in recent works such as [13,14].

The main goal of this paper is to present a scheme of approximation of the MK problem based on wavelet analysis in which we use wavelet filters to split the original problem. That is, we apply the filter to the discrete cost function in level j, which results in a cost function of level and three components of wavelet analysis. Using the information of the cost function given by the low-pass filter, which belongs to level , we construct a solution of the MK problem for that level , and using the additional information, the other three components of wavelet analysis are extended to , which is a solution to level j, where the projection of to level is . Finally, we make a local analysis of the solution to obtain an improved solution based on the type of points of that solution (we have two type of points that are defined in the base in the connectedness of the solution).

This work has three non-introductory sections. In the first of them we present the Haar multiresolution analysis (MRA) in one and two dimensions. Next, we relate this to the absolutely continuous measures over a compact in . We finish with the definition of the Monge–Kantorovich mass transfer problem and its relation to the MRA.

In the second section, we define a proximity criterion for the components of the support of the simple solutions of the problem and study in detail the problem of, given a solution at level of resolution for the problem, construct a feasible solution for the problem at level of resolution j such that it is a refinement of the solution with lees resolution.

On the other hand, in the third section we present a methodological proposal to solve the problem such that it can be summarized in a simple algorithm of six steps:

- Step 1.

- We consider a discretization of the cost function for the level j, denoted by .

- Step 2.

- We apply the wavelet transform to ; we obtain the low-pass component and three high-pass components, denoted by , and , respectively.

- Step 3.

- Using and the methodology of [3,4,9], we obtain a solution for associated with this cost function.

- Step 4.

- We classify the points of the support of the solution by proximity criteria as points of Type I or Type II.

- Step 5.

- Using the solution , the information of the high-pass components and Lemma 1, we obtain a feasible solution for the level j, which is denoted by . This feasible solution has the property that its projection to the level is equal to ; moreover, the support of is contained in the support of .

- Step 6.

- The classification of the points of induce classification of the points in by contention in the support. Over the points of Type I of the solution , we do not move those points. For the points of Type II, we apply a permutation to the solution over the two points that better improves the solution, and we repeat the process with the rest of the points.

Finally, we present a series of examples that use the proposed methodology based on wavelet analysis and compare their results with those obtained applying the methodology of [3,4,9].

2. Preliminaries

2.1. One-Dimensional MRA

The results of this and the following subsection are well known, and for a detailed exposition, we recommend consulting [15,16,17]. We begin by defining a general multiresolution analysis and developing the particular case of the Haar multiresolution analysis on . Given and , the dilatation operator and the translation operator are defined by

for every , where the latter denotes the usual Hilbert space of square integrable real functions defined on . A multiresolution analysis (MRA) on is a sequence of subspaces of such that it satisfies the following properties:

- (1)

- for every .

- (2)

- .

- (3)

- .

- (4)

- .

- (5)

- There exists a function , called the scaling function, such that the collection is an orthonormal system of translates and

We denote as the characteristic function of the set A. Then, the Haar scaling function is defined by

For each pair , we call

Hence, we define the function

The collection is called the system of Haar scaling functions. For , the collection is referred to as the system of scale Haar scaling functions. The Haar function is defined by

For each pair , we define the function

The collection is referred to as the Haar system on . For , the collection is referred to as the system of scale Haar functions. It is well known that with respect to the usual inner product in , the Haar system on is an orthonormal system. Moreover, for each , the collection of scale Haar scaling functions is an orthonormal system. Thus, for each , the approximation operator on is defined by

and the approximation space by

The collection is called Haar multiresolution analysis. Similarly, we have that for each , the detail operator on is defined by

and the wavelet space by

Note that for all . Hence, the collection

is a complete orthonormal system on ; this system is called the scale Haar system on . As a consequence, the Haar system is a complete orthonormal system on .

2.2. Two-Dimensional MRA

To obtain the Haar MRA on , we consider the Haar MRA on defined in the previous subsection with scaling and Haar functions and , and from them, through a tensor product approach we can construct a two-dimensional scaling and Haar function. First, we define the four possible products:

which are the scaling function associated with the unitary square and three Haar functions, respectively. Hence, for each , we define naturally the scaling and Haar function systems:

Then for , as in the one-dimensional case, we have that the collection

is an orthonormal basis on . Thus, the collection

is an orthonormal basis on . Then for and , the approximation operator is defined by

and for , the detail operators are

Hence, the projection can be written as

We will describe the approximation and detail operators from the geometric point of view. First of all, we fix some and define the square

Then, we have that is the characteristic function of , in symbols

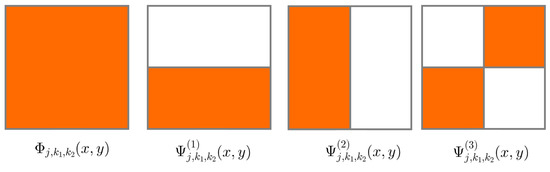

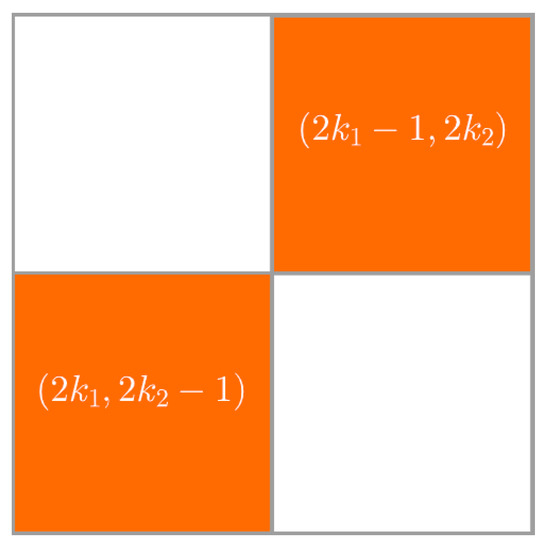

where . Therefore for , the operator acts as a discretization of f that is constant over the disjointed squares. On the other hand, we can split as follows (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Functions , , and .

- (i)

- Into two rectangles with half the height and the same width as , namely, the sets

- (ii)

- Into two rectangles with the same height and half the width as , namely,

- (iii)

- Into four squares with half the side lengths of , namely,

Hence, for , the function is defined by

(see Figure 1). Thus, the image of under the detail operator is a function formed by pieces that oscillate symmetrically on each square .

Now we have the elements to define an MRA on ; to do this, we will use the notation introduced for the one-dimensional MRA on defined in the previous subsection. For each , we define

Then the collection is the Haar multiresolution analysis on , where the dilatation and translation operators are defined by

respectively. Note that we have the following relation:

where , and . For more detail with respect to the Haar MRA, see [15].

2.3. Measures and MRA

In this subsection, we will use the two previous ones and the [9] approach to relate measures over with the Haar MRA on . The results and definitions presented in this and the following subsection can be found in the classical references [18,19]. We consider a compact subset X of and a measure such that it is absolutely continuous with respect to the Lebesgue measure . We call

the Radon–Nikodym derivative of with respect to . By construction, it necessary holds that . We additionally suppose that . Then, as a consequence of the Haar MRA on , we have that

Moreover, the compactness of X ensures that

The above allow us to define , the approximation of the measure to the level of the Haar MRA on , as the measure induced by the projection of the Radon–Nikodym to the level j. That is, is defined by the relation

We denote the expectation of a function with respect to as

Then Theorem 4 and Corollary 5 in [9] ensure that for each and , it is fulfilled that

Thus, is absolutely continuous with respect to the Lebesgue measure. If, additionally, we suppose that is a measure with support on X, then converges to in the and sense. That is, by the Riesz Theorem, we can associate each of these measures to an integrable function such that for each Lebesgue measurable set ,

and we apply the respective convergence mode. Further, the compact support of measures ensures that the sequence converges weakly to the measure , proof of which can be found in [9] Theorem 7.

2.4. M-K Problem and MRA

In this subsection, we study the Monge–Kantorovich problem from the point of view of the Haar MRA on (for a detailed exposition, we recommend consulting [9]). Let X and Y be two compact subsets of . We denote by the family of finite measures on . Given , we denote its marginal measures on X and Y as

and

for each -measurable set and . Let c be a real function defined on , and are two measures defined on X and Y, respectively. The Monge–Kantorovich mass transfer problem is given as follows:

A measure is said to be a feasible solution for the problem if it satisfies (38) and is finite. We said that the problem is solvable if there is a feasible solution that attains the optimal value for it. So is called an optimal solution for (38). If, additionally, we assume that and are absolutely continuous with respect to the Lebesgue measures on and , then in a natural way, we can discretize the problem through the Haar MRA on as follows. For , we define the problem of level j by:

where , and are the projections to level j of the measures , and , respectively, to the Haar MRA.

3. Technical Results

In this section, we present a series of results that ensure the good behavior of the methodological proposal of the next section. In order to do this, we start by assuming an problem with cost function , base sets and measure restrictions . In other words, we consider the problem of moving a uniform distribution to a uniform one with the minimum movement cost. Since in applications we work with discretized problems, then as a result of applying the MRA on , we have that our objective is to solve:

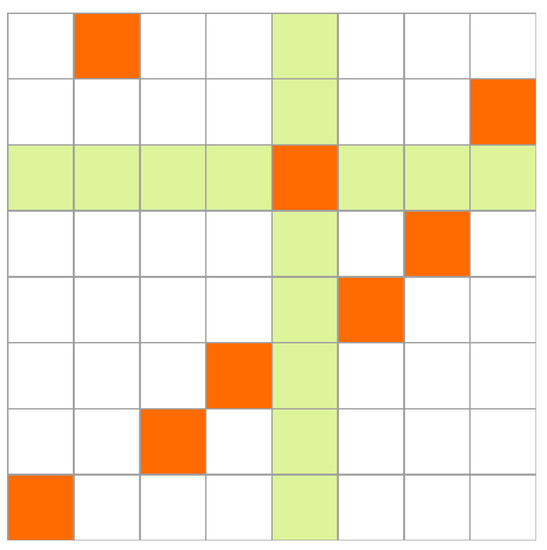

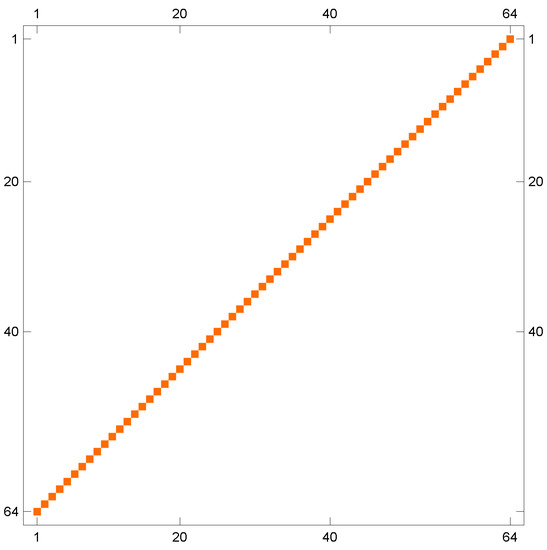

where is the portion of the initial value in the position of the x-axis allocated to the position of the y-axis. We call j-discrete unit square the grid formed by the squares (see (20)), dividing the set in blocks, in a such way that each one is identified with the point . We suppose that there is a simple solution for (40). That is, is a feasible solution such that, given with , it necessarily holds that for each and for each . Geometrically, if the measure is plotted as a discrete heat map in the j-discrete unit square, then no color element in the plot has another color element in its same row and column, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Definition 1.

We define a proximity criteria in the j-discrete unit square as follows: is a neighbor of if

In Figure 2, we plot the support of the hypothetical simple solution . Hence, the neighbors of the position in the middle of the cross are those that touch the yellow stripes. Then in this example, the middle point has four neighbors.

Figure 2.

Support of and the proximity criteria.

With this in mind, we can classify the points in as follows.

Definition 2.

We say that is a border point if or equals 0 or 1; otherwise, we call it an interior point. It is clear that a border point has at least one neighbor and at most three, whereas an interior point has at least two neighbors and at most four. Hence, we can partition into two sets as follows.

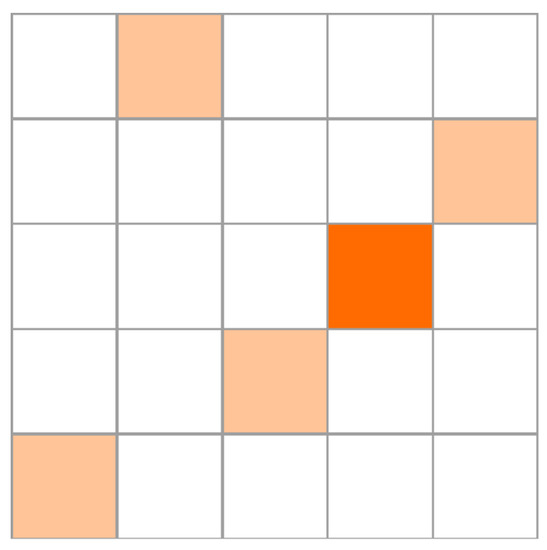

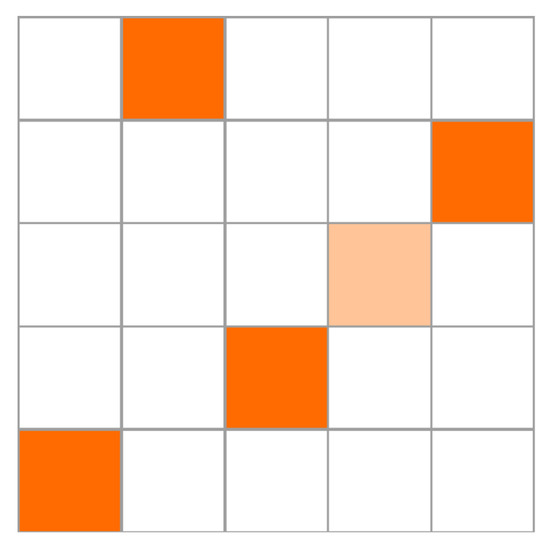

The set of the points of Type I is given by

and the set of the points of Type II is given by

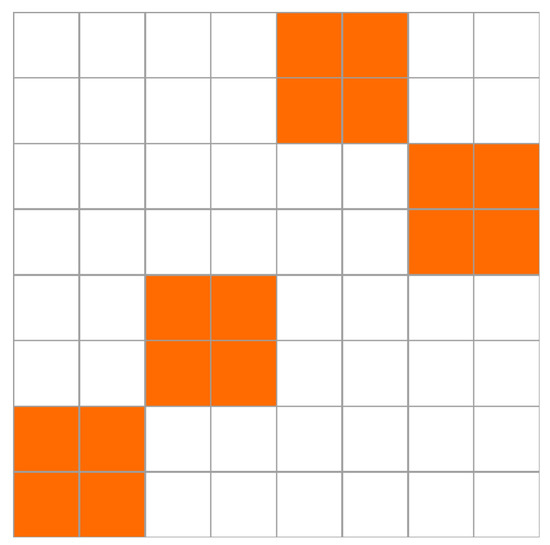

Intuitively, the set is composed of well-controlled points, whereas the set has the points that admit permutations between them, since, as we will see in the next section, in the proposed algorithm they will be permuted. See Figure 3 and Figure 4. Naturally, since is a feasible solution for (40), then given elements and for permutations over , the measure defined by

is a feasible solution.

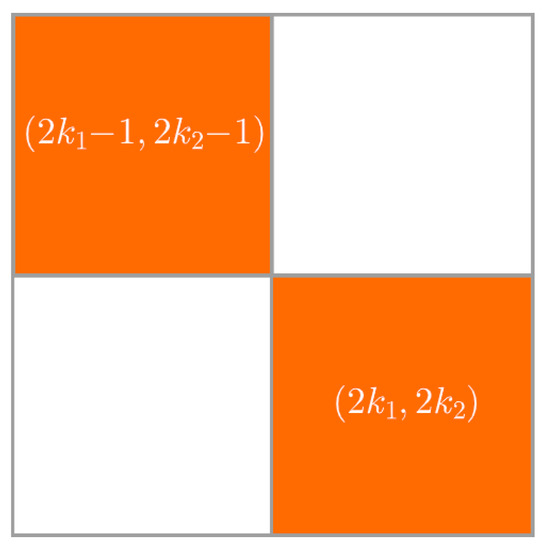

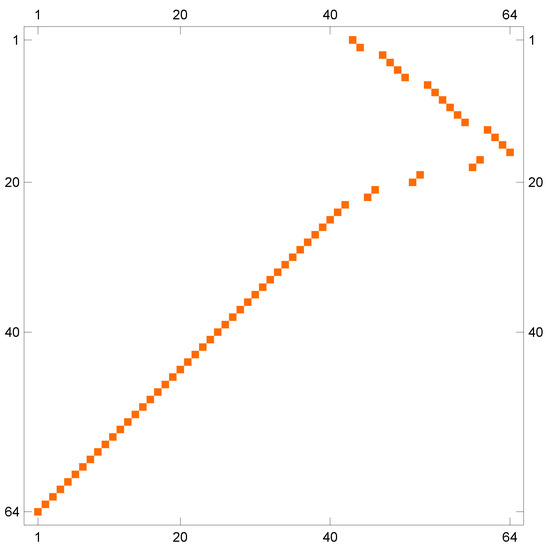

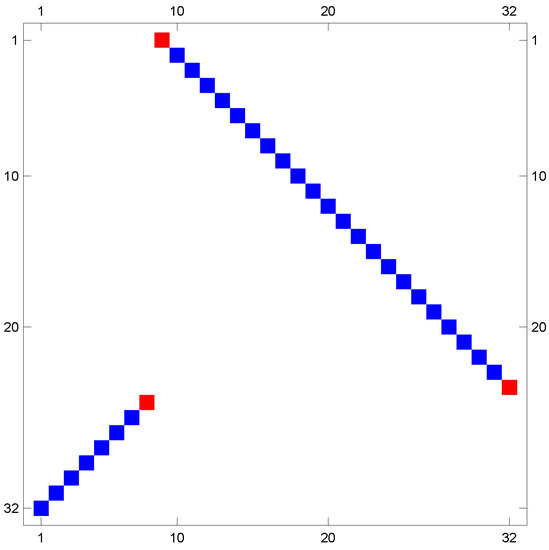

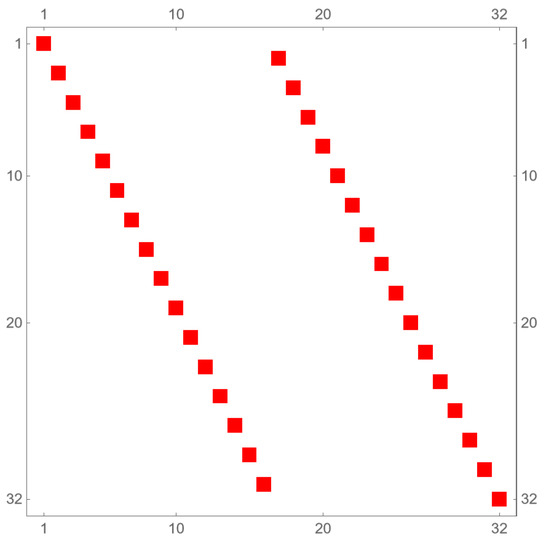

Figure 3.

Classification of the points in : Type I points.

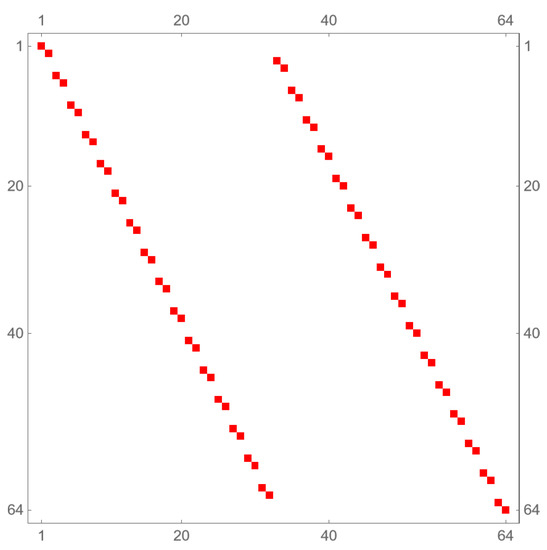

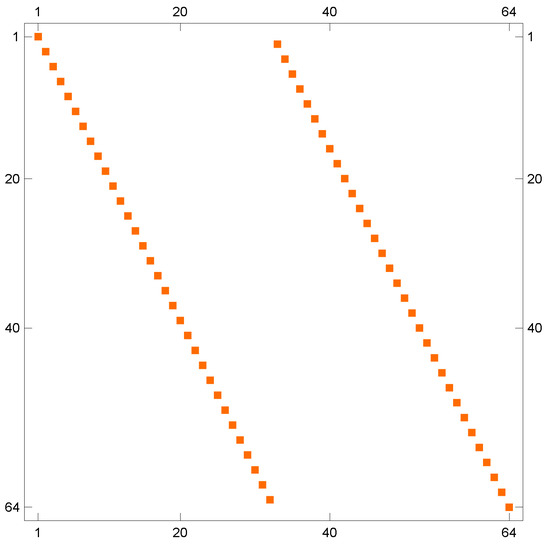

Figure 4.

Classification of the points in : Type II points.

Refining Projections

In this subsection, we study the problem of improving an optimal solution for (40) on level to a feasible solution for the next level j. Let be an optimal solution for level . Then we are looking for such that:

As described in the previous section, the measure can be decomposed in

where

From the geometric point of view, the projections are formed from differences of characteristic functions, as we mentioned in Section 2.2. So we have the following result:

Lemma 1.

Let and be an optimal solution for (40) at level . Then for each positive measure such that and , it necessarily holds that

for each Lebesgue measurable set and each . Therefore, the support of is contained in the support of .

Proof.

We only make the proof for the case , since the other two are very similar. To simplify the notation, we use the symbols and as measures or functions in the respective subspace of . Since when setting a level all the measures in question are constant in pairs of rectangles dividing , as we prove in Section 2.2, then it is enough to prove that (65) is valid on this rectangles. Let

and

as in (22). Then for , we have that

Now we will calculate each one of the expectations separately. By (17), (18) and (25), we have that

and

Then for and by (15), (16) and (22), we have that

where and

where . Similarly, but using (23) and (24), we can prove that

and

Then

Now, we will make an analogous argument for the case . Hence,

and

We have proved that if it is intended to go back to the preimage of the projection of the approximation operator from a level to a level j, the support of the level delimits that of the j level. Now, we will prove that for every measure that satisfies (45) and (46), it necessarily holds that .

Lemma 2.

Proof.

In order to perform this proof, we use the restrictions of the problem (40), which in turn, are related to the marginal measures. Therefore, we will only complete the proof for one of the projections, since the other is analogous. From the linearity of the Radon–Nikodym derivative, it follows that

That is, we are evaluating feasible solutions on rectangles whose height is half the size of the squares with which they are discretized at the j level of the Haar MRA. Now, we will develop in detail (66) evaluated on . Since is a simple solution, we call the only number such that , where is defined as in (20). With the aim of simplifying the notation, we define . By (16) and (25), we have that

By the way was defined, necessarily in the last equality it must be fulfilled that one of the terms in the expectation is equal to 0. Hence, it is fulfilled that

By a similar argument, it can be proved that

and

Hence,

Therefore, . In a similar way, we can prove that . □

Suppose we have a simple optimal solution for the problem discretized through the Haar MRA at level and that we are interested in refining that solution to the next level j. By Lemmas 1 and 2, any that satisfies (45) has its support contained in the support of and has components . Then the problem of constructing a feasible solution such that it refines is reduced to construct

which is equivalent to chosing for each a value such that

By Lemma 1 for each , it is fulfilled that

Therefore, the choice of is restricted to a compact collection, and since is a solution of the linear program (40), then

Thus, the sign of must be such that it minimizes . That is,

4. Methodological Proposal

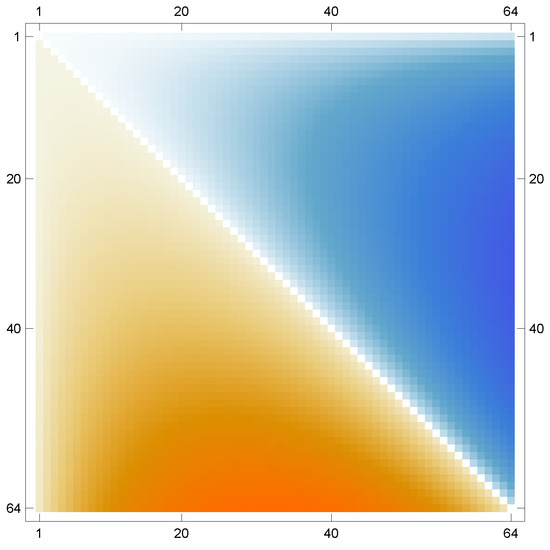

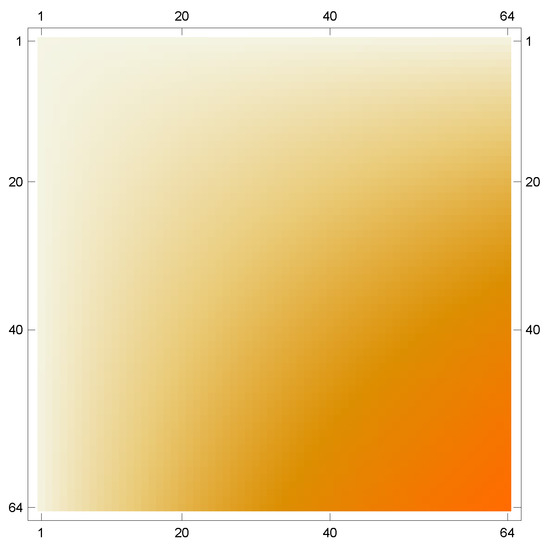

In this section, we show through examples a process that builds solutions to the problem with a reduced number of operations. First, we consider the problem with cost function defined by

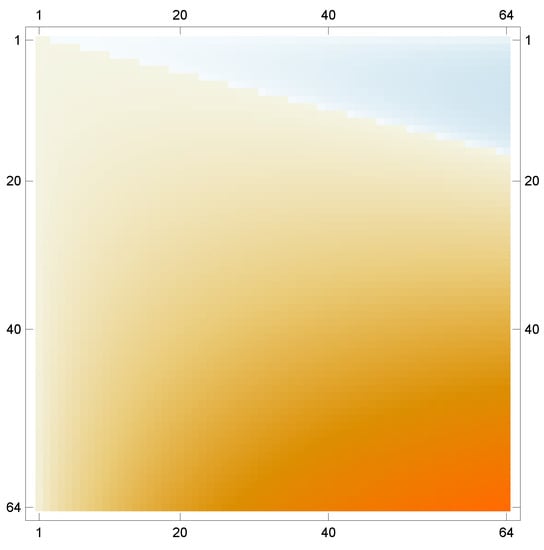

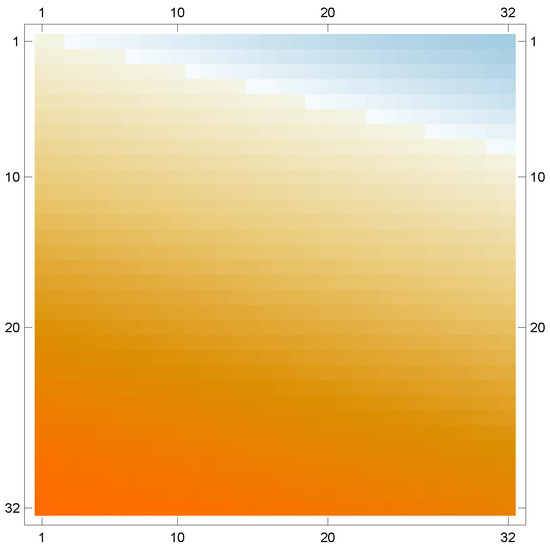

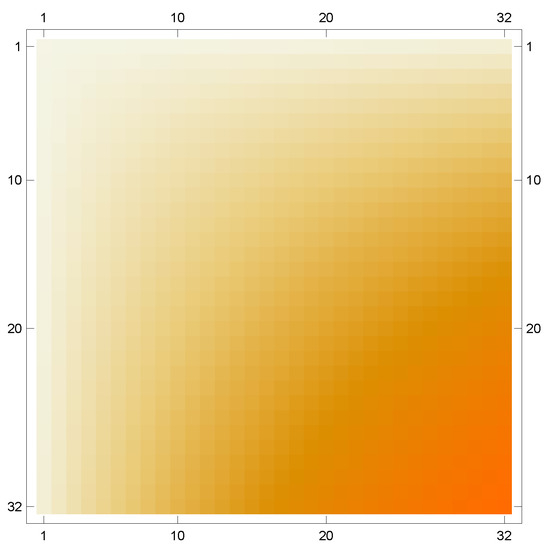

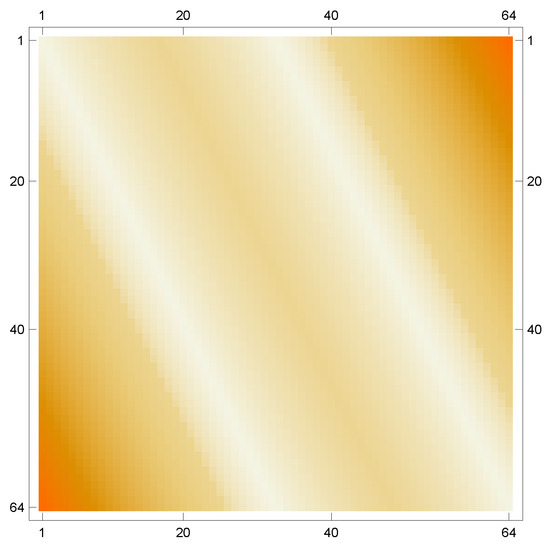

and homogeneous restrictions over . So that the algorithm can be graphically appreciated, we take a small level of discretization, namely . Thus, in the Haar MRA over at level , the cost function has the form shown in Figure 5, which can be stored in a vector of size .

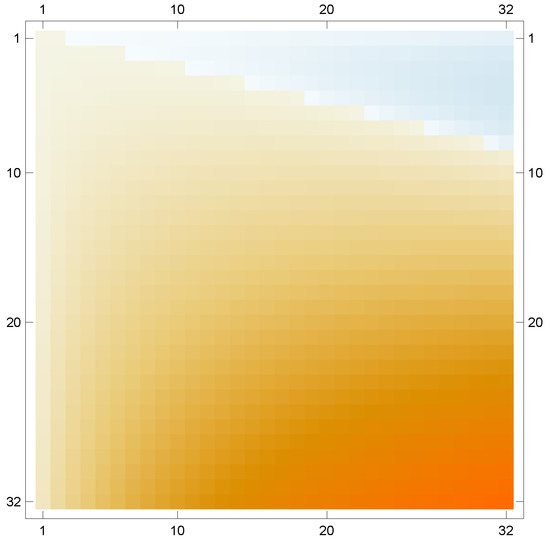

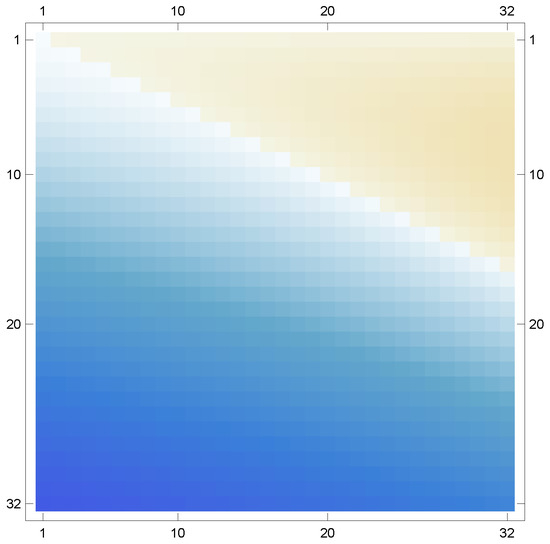

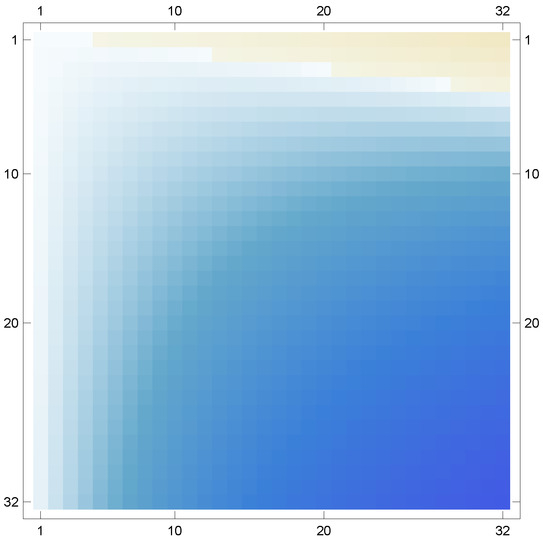

Now, we apply the filtering process to the cost function at level , which results in four functions

see Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 5.

Step 1. Discretization of the cost function to the level j, which is denoted by . In particular, the cost function is for lever .

Step 2. Filtering the original discrete function using the high-pass filter, which yield three discrete functions denoted by , and , that functions correspond to Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively, each describing local changes in the original discrete function. It is then low-pass filtered to produce the approximate discrete function , which is given by Figure 6.

Figure 6.

.

Figure 7.

.

Figure 8.

.

Figure 9.

.

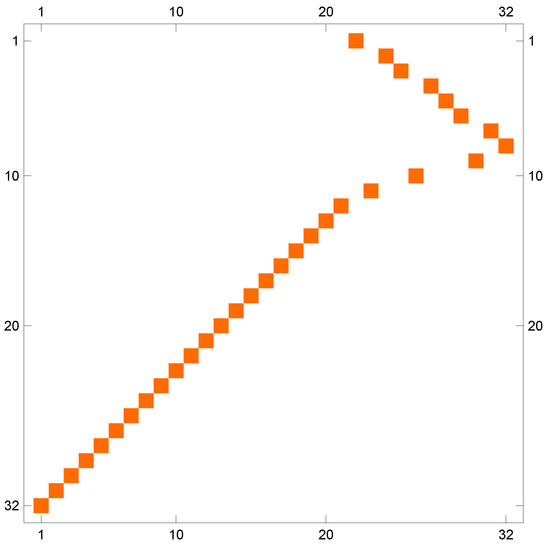

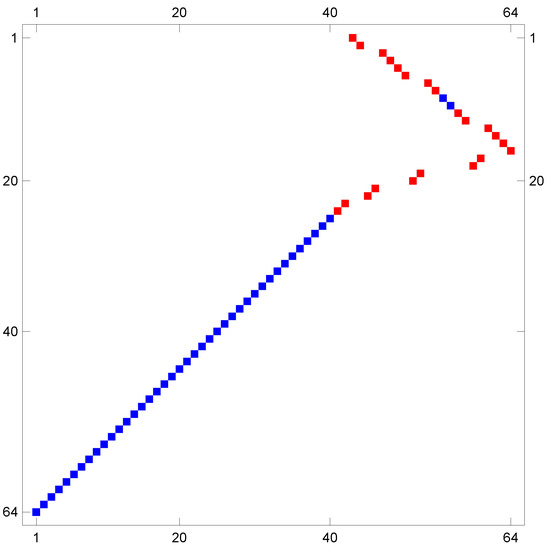

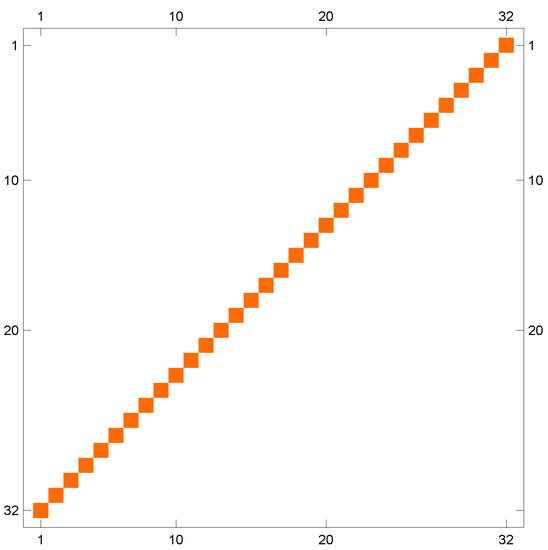

We then solve the problem for the level . That is, we find a measure that is an optimal solution for the problem with cost function . Such data can be stored in a vector of size ; see Figure 10. For each entry k, the formal application that plots this vector in a square is defined by , where and .

Figure 10.

Step 3. We obtain a solution for associated with the cost function given in Figure 6.

Since the measure is an optimal simple solution for the problem, then we can represent its support in a simple way, as we show below:

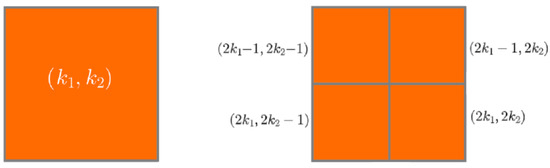

where is the square in (20). Next, we split each block into four parts as in (24); see Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Division of the components of into four parts.

From the technical point of view, in the discretization at level , we have a grid of squares that we call and identify with the points . Thus, we refine to a grid of , splitting each square into four, which in the new grid are determined by points

see Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Refinement of grid from level to j of discretization.

As we prove in Lemma 1, any feasible solution that refines has its support contained in . Therefore, we must only deal with the region delimited by the support of . By Lemma 2, in order to construct the solution , we only need to determine the values corresponding to the coefficients of the wavelet part ; however, by (77) and (78), those values are well determined and satisfy that when added with the scaling part , the result is a scalar multiple of a characteristic function. For example if the square has scaling part coefficient , then we choose . Hence, by (21) and (25), we have that

Thus, from an operational point of view, we only need to chose between two options of supporting each division of square , as we illustrate in Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Supports for refinement of the element corresponding to the level j:Option I.

Figure 14.

Supports for refinement of the element corresponding to the level j: Option II.

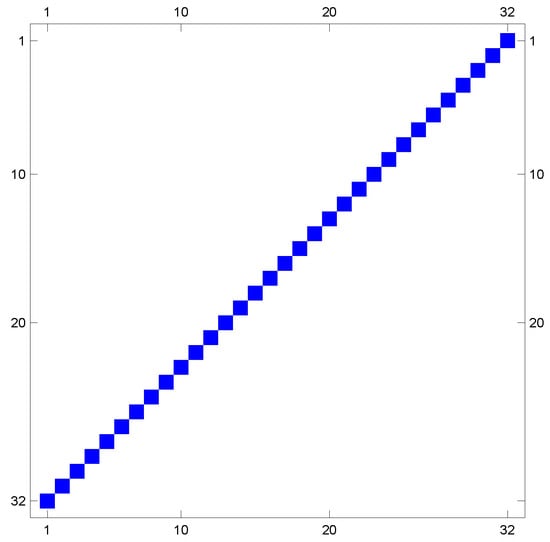

This coincides with our geometric intuition. Hence, the resulting feasible solution has its support contained in , and its weight within each square is presented in a diagonal within that block; see Figure 15. Finally, we can improve by observing the way the filtering process acts. To do this, we apply the proximity criteria (41) and split the support of into points of Type I and II. In Figure 16, we identify the points of Type I and II of solution , whereas in Figure 15, we do the same but for .

Intuitively, the division of the support into points of Type I and II allows us to classify the points so that they have an identity function form and, consequently, that come from the discretization of a continuous function—points of Type I—and in points that come from the discretization of a discontinuous function—points of Type II. Thus, the points of Type I are located in such a way that they generate a desired solution, and therefore it is not convenient to move them, whereas Type II points are free to be changed as this does not lead to the destruction of a continuous structure in the solution. As we mentioned in the previous section, each permutation of rows or columns of one weighted element with another constructs a feasible solution; see (44). Thus, as a heuristic technique to improve the solution, we check the values associated with each solution obtained by permuting rows or columns of points of Type II of the solution . We call the solution for which its permutation gives it the best performance. See Figure 17.

Figure 16.

Step 4. We classify the points of the support of the solution by proximity criteria as points of Type I ■ or Type II ■ (the measure corresponds to Figure 10).

Finally, we present Table 1 that compare the solutions of the problem, in which is the value associated with the optimal solution at level of discretization , is the value associated with an optimal solution at level of discretization , and is the value associated with the solution obtained by the heuristic method described in the previous paragraph.

Table 1.

Comparison of the values corresponding to , and .

Figure 17.

Step 6. Classification of the points of induces classification of the points in by contention in the support. Over the points of Type I of the solution , we do not move those points. For the points of Type II, we apply a permutation to the solution over the two points that improve the solution and repeat the process with the rest of the points.

5. Other Examples of This Methodology

We conclude this work with a series of examples in which we apply the proposed methodology. Each of them is divided into the six-step algorithm introduced in the previous section and corresponds to a classical example existing in the literature.

5.1. Example with Cost Function

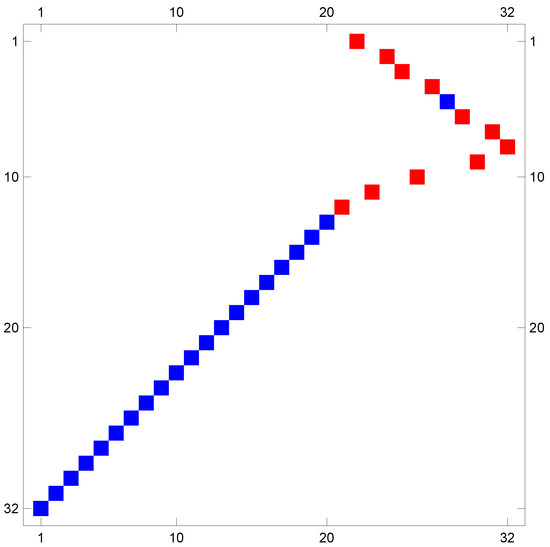

Let be the problem with cost function and uniform restrictions and over the unitary interval . In order to be more didactic, we consider the level of discretization . Next, we present the reduced algorithm.

- Step 1.

- Discretize the cost function at level j—that is, over a grid of . Figure 18.

Figure 18. Discretization of the cost function at level .

Figure 18. Discretization of the cost function at level . - Step 2.

- Apply the filtering process to the cost function at level , obtaining the filtered cost function , which is plotted on a grid of . Figure 19.

Figure 19. Filtering of the cost function c at level .

Figure 19. Filtering of the cost function c at level . - Step 3.

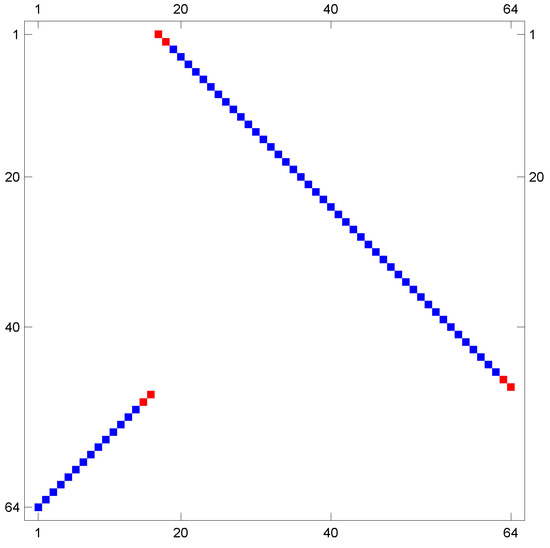

- Find an optimal simple solution for the discretized problem. That is, solve for the cost function and obtain an optimal simple solution . Figure 20.

Figure 20. solution for the filtered function c at level .

Figure 20. solution for the filtered function c at level . - Step 4.

- Apply the proximity criteria to the support of . Figure 21.

Figure 21. Classification of points of into Type I ■ and Type II ■.

Figure 21. Classification of points of into Type I ■ and Type II ■. - Step 5.

- Refine the optimal simple solution to a feasible solution , dividing each weighted square at level into four squares at level j (see (82)) and place mass according to the criteria (83). Figure 22.

Figure 22. Solution from refinement of .

Figure 22. Solution from refinement of . - Step 6.

- Permute the rows and columns of the points of Type II in using (44) to construct feasible solutions and chose the one that has better performance. Figure 23.

Figure 23. Final result .

Figure 23. Final result .

The following Table 2 contains the comparison of the proposed methodology with the two immediate levels of resolution.

Table 2.

Comparison of the values corresponding to , and .

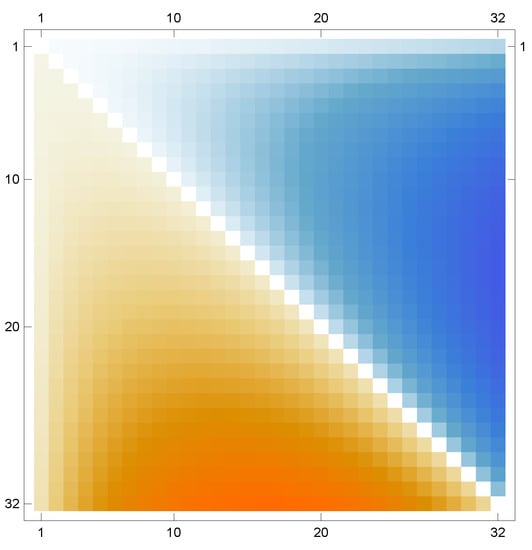

5.2. Example with Cost Function

Let be the problem with cost function and uniform restrictions and over the unitary interval . In order to be more didactic, we consider the level of discretization . Next, we present the reduced algorithm.

- Step 1.

- Discretize the cost function at level j—that is, over a grid of . Figure 24.

Figure 24. Discretization of the cost function at level .

Figure 24. Discretization of the cost function at level . - Step 2.

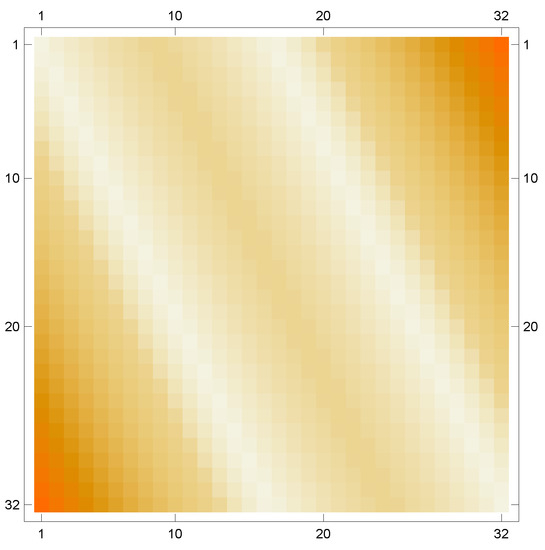

- Apply the filtering process to the cost function at level , obtaining the filtered cost function , which is plotted on a grid of . Figure 25.

Figure 25. Apply the filter to the cost function c at level .

Figure 25. Apply the filter to the cost function c at level . - Step 3.

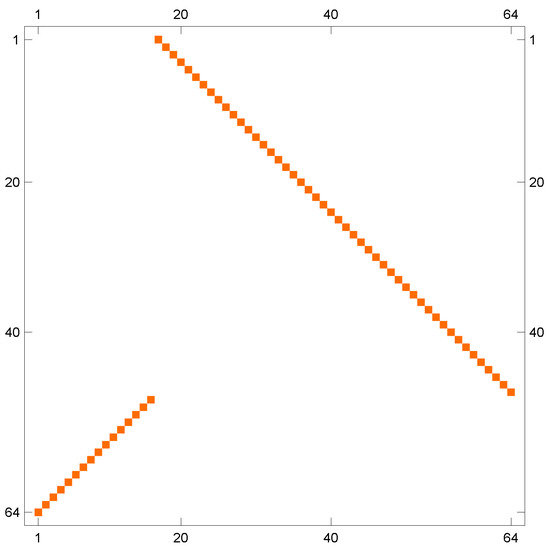

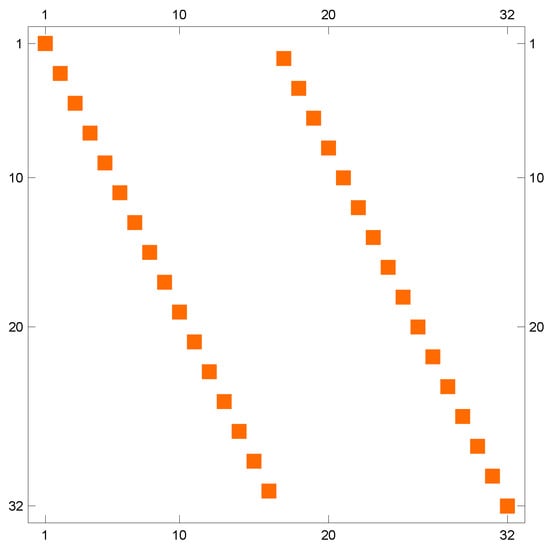

- Find an optimal simple solution for the discretized problem. That is, solve for the cost function and obtain an optimal simple solution . Figure 26.

Figure 26. Solution of the for the function c at level .

Figure 26. Solution of the for the function c at level . - Step 4.

- Apply the proximity criteria to the support of . Figure 27.

Figure 27. In this example there are only Type I points ■.

Figure 27. In this example there are only Type I points ■. - Step 5.

- Refine the optimal simple solution to a feasible solution , dividing each weighted square at level into four squares at level j (see (82)) and placing mass according to the criteria (83). Figure 28.

Figure 28. Solution from refinement of .

Figure 28. Solution from refinement of . - Step 6.

- Permute the rows and columns of the points of Type II in using (44) to construct feasible solutions and chose the one that has better performance. Figure 29.

Figure 29. Final result .

Figure 29. Final result .

The following Table 3 contains the comparison of the proposed methodology with the two immediate levels of resolution.

Table 3.

Comparison of the values corresponding to , and .

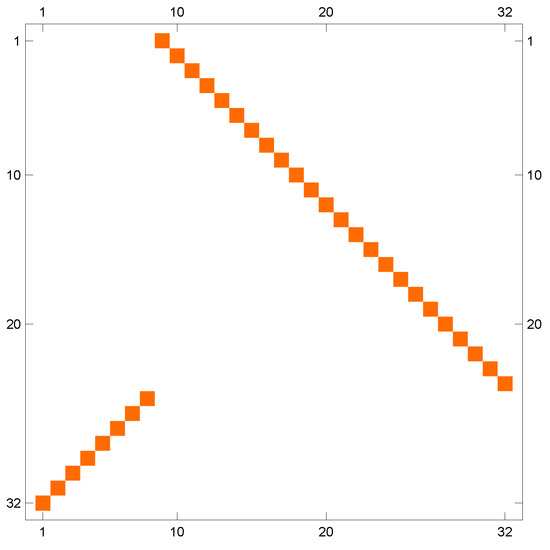

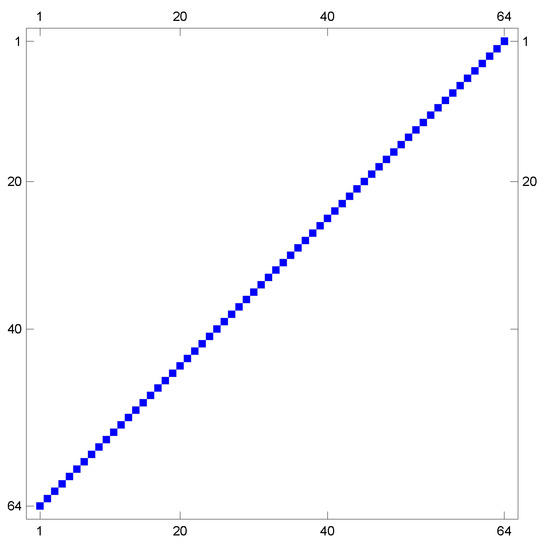

5.3. Example with Cost Function

We take the problem with cost function and homogeneous restrictions over the unitary interval. Again, we consider the level of discretization .

- Step 1.

- Discretize the cost function at level j. Figure 30.

Figure 30. Discretization of cost function for level .

Figure 30. Discretization of cost function for level . - Step 2.

- Apply the filtering process at level to the cost function. Figure 31.

Figure 31. Filtered cost function for .

Figure 31. Filtered cost function for . - Step 3.

- Find an optimal simple solution for the problem. Figure 32.

Figure 32. Solution of the problem.

Figure 32. Solution of the problem. - Step 4.

- Apply the proximity criteria to the support of . Figure 33.

Figure 33. In this example, there are only Type II points ■.

Figure 33. In this example, there are only Type II points ■. - Step 5.

Figure 34. Feasible solution from refinement of .

Figure 34. Feasible solution from refinement of .- Step 6.

- Permute points of Type II of using (44) to construct feasible solutions and chose which has better performance. Figure 35.

Figure 35. Final result .

Figure 35. Final result .

The Table 4 summarizes the results obtained.

Table 4.

Comparison of values , and .

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Note that with the methodology of [3,4,9], the authors obtain a solution of . For this, they need to resolve a transport problem with variables. We call this methodology an exhaustive method. For our methodology, in Step 3, we need to resolve a transport problem with variables, and the other steps of the methodology are methods of classification, ordering and filtering; with data for classification and ordering and data for filtering, it is clear that this method requires fewer operations to resolve transport problems.

In summary, we have the following table comparing the results of solving the examples more often used in the literature with our methodology versus the exhaustive method (using all variables).

| Cost Function | Error | ||

| Cost Function | Error | ||

| Cost Function | Error | ||

Note that our method always improves the solution of the level and for some examples give an exact solution; we use Mathematica© and basic computer equipment for programming this methodology, and maybe we can improve the results with software focused on numerical calculus and better computer equipment. It is also important to mention that the methodology presented in this work has some weaknesses. In our computational experiments, we noticed that if we did not start with a sufficient amount of information, then the methodology tended to give very distant results. In other words, if the initial level of discretization was not fine enough, then because the algorithm lowers the resolution level when executed, such loss of information generates poor performance. However, when starting with an adequate level of discretization, experimentally it can be observed that the distribution of the solutions for the discretized problems, as well as the respective optimal values, have stable behavior with a clear trend. The question that arises naturally is: “In practice, what are the parameters that determine good or bad behavior of the algorithm?” Clearly, if the cost function is fixed and we rule out the possible technical problems associated with programming and computing power, the only remaining parameter is the initial refinement level at which the algorithm is going to work—that is, the level j. However, if we reflect more deeply on the reasons why there is a practical threshold beyond which at a certain level of discretization the algorithm has stable behavior, we only have as a possible causes the level of information of the cost function that captures the MR analysis. In other words, if the oscillation of the cost function at a certain level of resolution is well determined by MR analysis, then the algorithm will have good performance.

The approach presented in this paper is far from exhaustive and, on the contrary, opens the possibility for a number of new proposals for approximating solutions to the MK problem. The above is due to the fact that in the work [9], it was proven that discretization of the MK problem can be performed from any MR analysis over . Therefore, the possibility of implementing other types of discretions remains open. In principle, as we mentioned in the previous paragraph, the most natural thing is to expect better performance if the nature of the cost function and the types of symmetric geometric structures that it induces in space are studied in order to use an MR analysis that fits this information and therefore has more efficient performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.-N. and C.G.-F.; methodology, A.S.-N., R.R.L.-M. and C.G.-F.; software, C.G.-F.; investigation, A.S.-N. and J.R.A.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.-N., J.R.A.-P. and C.G.-F.; writing—review and editing, A.S.-N. and R.R.L.-M.; project administration A.S.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hernández-Lerma, O.; Lasserre, J.B. Approximation schemes for infinite linear programs. SIAM J. Optim. 1998, 8, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, J.; Gabriel-Argüelles, J.R.; Hernández-Lerma, O. On solutions to the mass transfer problem. SIAM J. Optim. 2006, 17, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel-Argüelles, J.R.; González-Hernández, J.; López-Martínez, R.R. Numerical approximations to the mass transfer problem on compact spaces. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 2010, 30, 1121–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Garrido, M.L.; Gabriel-Argüelles, J.R.; Quintana-Torres, L.; Mezura-Montes, E. A metaheuristic for a numerical approximation to the mass transfer problem. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2016, 26, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Garrido, M.L.; Gabriel-Argüelles, J.R.; Quintana-Torres, L.; Mezura-Montes, E. An Efficient Numerical Approximation for the Monge–Kantorovich Mass Transfer Problem. In Machine Learning, Optimization, and Big Data. MOD 2015; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Pardalos, P., Pavone, M., Farinella, G., Cutello, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9432, pp. 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröchenig, K.; Madych, W.R. Multiresolution analysis, Haar bases, and self-similar tilings of Rn. Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. Trans. Inf. Theory 1992, 38, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, K.D.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.J.; Zhang, A.; Chen, Q. Millimeter-wave E-plane waveguide bandpass filters based on spoof surface plasmon polaritons. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2022, 70, 4399–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yang, Z.; Wei, W.; Gao, B.; Xin, D.; Sun, C.; Gao, G.; Wu, G. Novel detection approach for thermal defects: Study on its feasibility and application to vehicle cables. High Volt. 2023, 8, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Nungaray, A.; González-Flores, C.; López-Martínez, R.R. Multiresolution Analysis Applied to the Monge–Kantorovich Problem. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2018, 2018, 1764175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haker, S.; Tannenbaum, A.; Kikinis, R. Mass Preserving Mappings and Surface Registration; MICCAI 2001, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2208, pp. 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, Y.; Haker, S.; Tannenbaum, A. Optimal mass transport for registration and warping. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, E.; Rehman, T.; Tannenbaum, A. An efficient numerical method for the solution of the L2 optimal mass transfer problem. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2010, 32, 7–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, W. Existence of solutions for the (p, q)-Laplacian equation with nonlocal Choquard reaction. Appl. Math. Lett. 2023, 135, 108418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Hu, J.; Shi, K.; Luo, R.; Huang, R.; Ghosh, B.K.; Huang, J. A novel optimal bipartite consensus control scheme for unknown multi-agent systems via model-free reinforcement learning. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 369, 124821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walnut, D.F. An Introduction to Wavelet Analysis; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, K.; Labate, D.; Lim, W.Q.; Weiss, G.; Wilson, E. Wavelets with composite dilations and their MRA properties. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2006, 20, 202–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishtal, I.A.; Robinson, B.D.; Weiss, G.L.; Wilson, E.N. Some simple Haar-type wavelets in higher dimensions. J. Geom. Anal. 2007, 17, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaraa-Mokhtar, S.; John, J.; Hanif, D. Linear Programming and Network Flows; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 513–528. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley, P. Convergence of Probability Measures; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 27–29. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).