Abstract

Ruled surfaces play an important role in various types of design, architecture, manufacturing, art, and sculpture. They can be created in a variety of ways, which is a topic that has been the subject of a lot of discussion in mathematics and engineering journals. In geometric modelling, ideas are successful if they are not too complex for engineers and practitioners to understand and not too difficult to implement, because these specialists put mathematical theories into practice by implementing them in CAD/CAM systems. Some of these popular systems such as AutoCAD, Solidworks, CATIA, Rhinoceros 3D, and others are based on simple polynomial or rational splines and many other beautiful mathematical theories that have not yet been implemented due to their complexity. Based on this philosophy, in the present work, we investigate a simple method of generating ruled surfaces whose generators are the curvature axes of curves. We show that this type of ruled surface is a developable surface and that there is at least one curve whose curvature axis is a line on the given developable surface. In addition, we discuss the classifications of developable surfaces corresponding to space curves with singularities, as these curves and surfaces are most often avoided in practical design. Our research also contributes to the understanding of the singularities of developable surfaces and, in their visualisation, proposes the use of environmental maps with a circular pattern that creates flower-like structures around the singularities.

Keywords:

singularity; curvature axis; developable surface; ruled surface; differential geometry; Frenet frame; visualisation of surfaces MSC:

53Axx; 65D17

“If people do not believe that mathematics is simple, it is only because they do not realize how complicated life is.”

—John von Neumann

1. Introduction

The theory of curves and the theory of ruled surfaces are closely related topics, both of which are essential in space kinematics. A few years ago, we came across a problem concerning the relationship between space curves and ruled surfaces for which we could find no study in the literature. Specifically, it is obvious and simple that the curvature axis of a space curve draws a ruled surface along the curve. However, this fact has not yet been studied in the literature. The only theory known so far that combines these two topics is E. Study’s correspondence principle [1].

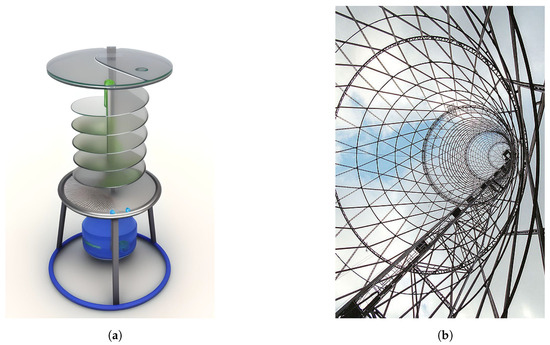

Ruled surfaces are a class of mathematical surfaces that can be generated by moving lines, also known as generators [2,3,4]. In CAD systems, such surfaces can be generated by moving the cross-section along the rail curve [5]. A developable surface is a special type of ruled surface that can be flattened into a plane without stretching or tearing. Due to their simplicity and ease of fabrication, they are used in a variety of fields [6,7,8] (interested readers can watch this YouTube video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-jZfFgfGj1M (accessed on 22 October 2023) about the applications of ruled surfaces in architecture.).

Ruled surfaces are widely used in the modelling and design of complex shapes and structures while facilitating the analysis of algebraic surface properties [9,10,11,12]. In addition, their practical importance extends to various industries, including manufacturing and construction, where they provide a streamlined process for fabricating flat sheets of material. Ruled surfaces play a central role in mechanical engineering, contributing to the design of aircraft, automobiles, and applications ranging from agriculture to light manufacturing and arts (see examples in Figure 1 and Figure 2, and in Appendix A).

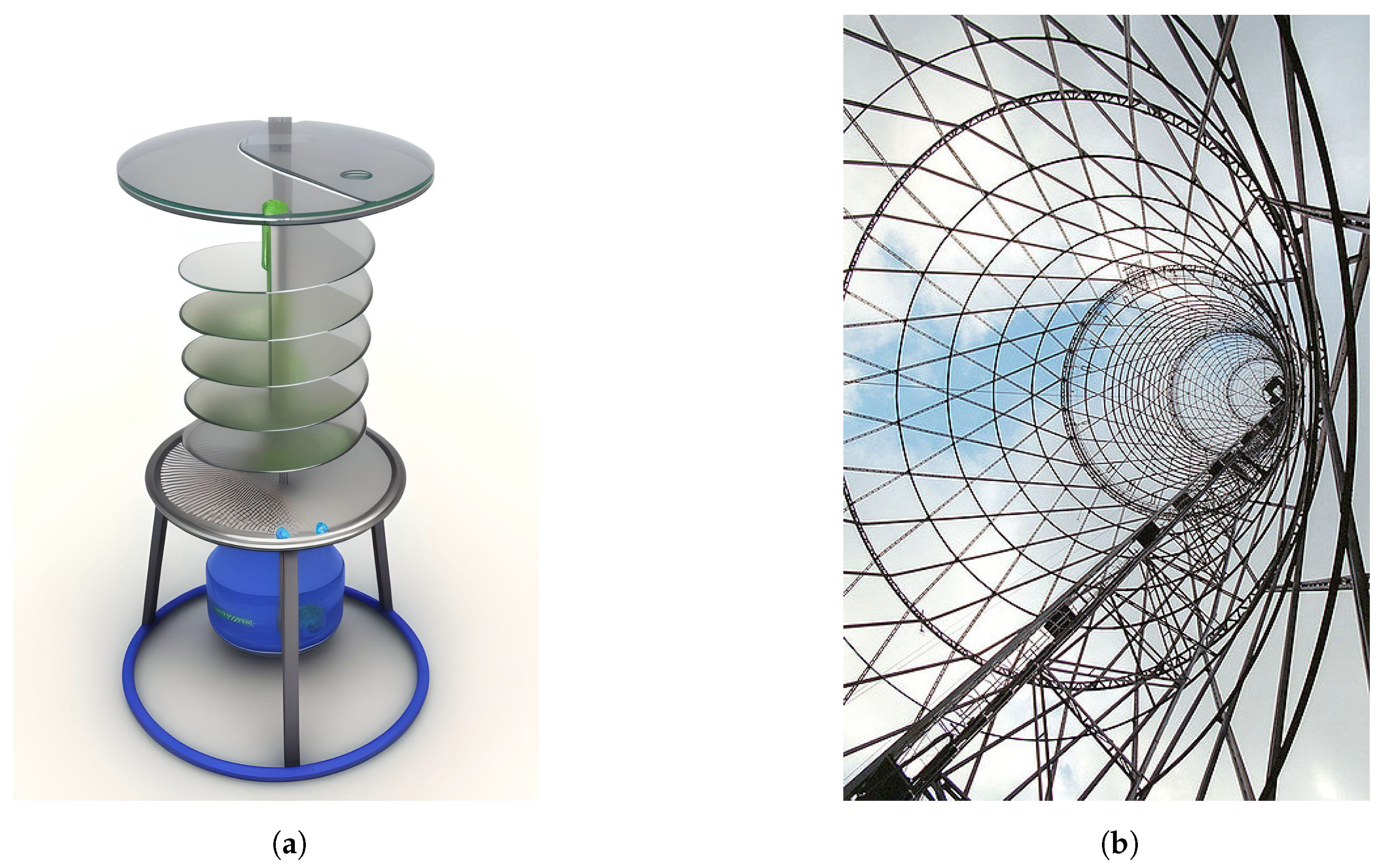

Figure 1.

Applications of ruled surfaces: (a) AI-enhanced image of a dew collector based on a ruled surface (helicoid) [13]. (b) The grid shell of the Shukhov Tower in Moscow, whose sections are doubly ruled. The image has been adapted from Wikipedia.

Figure 2.

AI image generated from a Wikipedia photo of hyperbolic cooling towers (the surface can be doubly ruled) at Didcot Power Station, UK.

Discussing the importance and applications of developable surfaces, the paper in [14] reviews techniques and patents in geometric modelling and highlights developments in this field and concludes that further research is needed in several key areas of developable surfaces. Some special curves construct ruled surfaces with the help of the Frenet frame and there are also very good papers on this subject, such as [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

The main references on developable surfaces [2,15,16,17] have shown that developable surfaces can be created by moving lines across the surfaces. In addition to the differential geometric properties of developable surfaces, such as Gaussian and mean curvatures, singularities are also studied. The main papers on singularities are [15,21,24]. However, there is no information on developable surfaces that can be created from the curvature axis of a curve.

The present work aims to fill this gap by investigating the properties of developable surfaces generated by the curvature axis and their properties in differential geometry. The idea is to exploit the relationship between the curvature axis and the developable surface to obtain a new type of ruled surface with interesting properties. We provide a result similar to the correspondence principle [1], but between space curves and developable surfaces. Our work explores the relationship between the curvature axis of a curve and the developable ruled surface it generates, filling a gap in the existing literature and contributing to the understanding of the relationship between curves and developable surfaces.

The paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we provide some preliminary definitions and concepts related to curves, the curvature axis, ruled surfaces, and developable surfaces. In Section 3, we show that moving the curvature axis along a curve yields a developable surface. In Section 4, we discuss finding from some types of developable surfaces. Finally, in Section 5, we study the singularities of the developable surface and conclude our work in Section 6.

2. Preliminary Concepts and Definitions

This section provides a brief overview of some basic concepts and definitions related to space curves and their kinematic frames. In particular, we define what a curve is and how to calculate its curvature and torsion. We also define what a ruled surface is and give an example of a developable surface. Finally, we introduce the concept of a curvature axis, its properties, and its relationship to the Frenet framework.

Theorem 1.

(The Frenet–Serret formulas) Let α be a regular and smooth curve whose first and second derivatives (i.e., velocity and acceleration vectors) are not required to be proportional. Then there is a rigid motion on the curve α defined by its Frenet frame [2,24,25,26,27,28,29]:

where and τ are the curvature and torsion functions of the curve α, respectively, and refers to the derivative of the curve with respect to its arc-length parameterisation. The curvature at a given point on a differentiable curve is essentially the curvature of the osculator circle, i.e., the circle that provides the best approximation of the curve near that point. This close relationship of the circle to curvature is due to the fact that it has the same curvature at the same point.

Definition 1.

An osculator circle is a planar geometric object. Therefore, it is determined via the elements t,n that stretch the tangent plane of the curve, which are the elements that determine the planar behavior of the curve at the point where it touches the curve and the curvature of the curve, which is inversely proportional to the distance from that point to the centre of the osculator circle. The centre of the osculator circle at a given point on the curve α is as follows [2,24,25,27]:

Definition 2.

The tangents of a curve α form a surface along the curve. This surface is called the tangent surface. The lines on this tangent surface that intersect perpendicular to the tangents of α are called the involutes, represented by β, of the curve α, and can be given as follows:

where c is constant [25,26,27].

Conversely, is the evolute of . But there is a difference; the fact that is perpendicular to the tangent of means that its tangent lies in the normal plane of . So, the equation for the evolute is given by

These curves are now involute–evolute mates.

Definition 3.

At a point of the curve α, there are spheres whose order of contact with the curve is greater than 3, and these spheres are called osculator spheres [25,27]:

The locus of the centres of these spheres generates a line called the curvature axis, which passes through the centre of curvature of the curve.

Definition 4.

The curvature axis of a space curve α is represented by the following equation:

In this formula:

- represents a line at the point .

- is a position vector associated with a point on a curve at a particular parameter value .

- is the normal component, where represents the curvature of the curve at the point , and is the unit normal vector at that point. This component ensures that is displaced from the curve in the direction of its normal.

- is the binormal component, where is the unit binormal vector at the point , and is a scaling factor that determines how far is from the curve along the binormal direction [25,26,27,30].

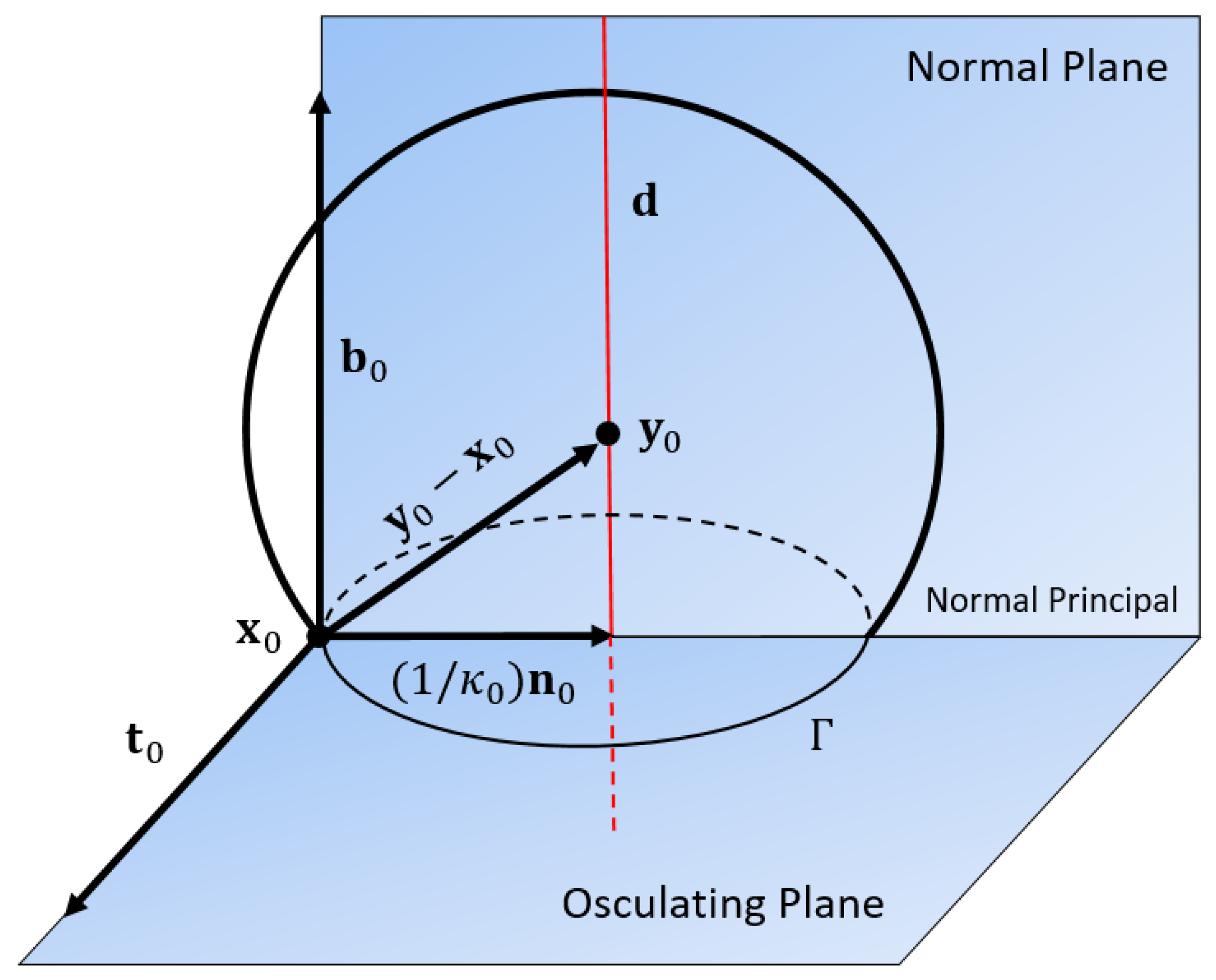

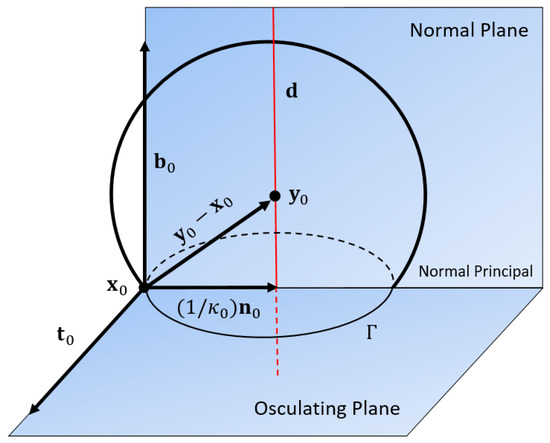

This formula is often used to describe the position of a point near a curve, considering its position on the curve (), the effect of curvature (), and the binormal direction (). It is a part of the mathematics used to study the geometry of curves in 3D space. Generally speaking, there is a correspondence between a point lying on the curve and a line (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The curvature axis (in red) of a regular curve and its Frenet frame.

Definition 5.

A ruled surface is a surface that admits a parameterization of the form

where and are curves called the base curve and directrix of and , respectively, with [2].

If u is fixed, i.e., then generates a line that passes through and has unit direction vector . These lines are called the rulings of . If is constant, then is called a cylinder. If never vanishes, then is called a non-cylindrical surface.

A parameterisation for non-cylindrical ruled surfaces can also be given by striction curves [17]. This curve does not depend on the base curve on the surface and does not have to be regular. If we want to re-parameterise the developable surface with this curve, then we have

Note that is parallel to .

Remark 1.

The characterization of a developable surface can be determined using the following equation [17]:

The equation is a condition that must be satisfied for a curve parameterised by s to be a trajectory of a certain type of differential equation. This type of differential equation is known as a Hamiltonian system [31,32,33].

Helicoid, which has many applications in engineering [13], is a very good example of this type of developable surface. It is also known as the tangent-developable surface of a circular helix curve.

3. Construction of the Developable Ruled Surface

Here, we investigate the geometric properties of the developable surface that is generated by the curvature axis of a curve and how these properties are related to the curvature and torsion of the curve. The developable surface can be described using several parameters, such as its generators, directrices, and ruling lines, which can be calculated using the curvature and torsion of the curve. Curvature theory encompasses several closely related concepts in geometry. Essentially, curvature describes the extent to which a curve differs from being perfectly flat or a surface from being perfectly flat. Flat surfaces are generally known as developable surfaces.

The relationship between the parameters of the developable surface and the curvature and torsion of the curve is important because it helps us understand the behavior of the surface and how it changes with variations in the shape of the curve. For example, changes in the curvature of the curve can affect the shape of the developable surface and its parameters, which in turn can affect its suitability for various applications such as architecture, product design, mechanical materials, and manufacturing.

We give the derivation of the equations for the curvature axis of a curve. If we consider this axis (line) through the curve, then we obtain a ruled surface.

Theorem 2.

Let be a smooth curve, s be arc-length parameterisation, and be its Frenet–Serret apparatus, then the trajectory

generates a developable surface.

Proof.

In order for to be a developable surface, it must satisfy Equation (5). In terms of fitting into the equation,

Using the Frenet–Serret kinematic formulation given for the curve , we obtain

So the developability condition

is fulfilled. □

4. Finding the Curve

What we have done so far is to find the developable surfaces corresponding to the given space curves. Now let us try to find the curve from a given ruled surface. For this, we need to look at the classes of developable surfaces.

In general, except planes, there are three types of developable ruled surfaces [29] (readers interested in the classification of non-developable ruled surfaces are referred to the work in [34]). For each classification, we assume the equation of the ruled surface as follows:

All comparisons below are made according to Equation (7).

4.1. Generalized Cylinder-Developable Surfaces

4.2. Conical-Developable Surfaces

4.3. Tangent-Developable Surface

These surfaces are generated by moving a straight line that is parallel to the tangent along the curve.

of the curve (), i.e., the curve of regression.

4.4. Comparisons

To determine whether the surfaces generated by the curvature axis of a curve fit with cylindrical, conical, or tangent surfaces, we can compare Equation (6) with the equations for these types of surfaces. This allows us to examine the geometric properties of the surfaces and determine their compatibility with these types of surfaces.

The binormal of curve is a constant vector, which means that is a planar curve, i.e., .

Solving this differential equation gives us the following coordinate functions:

where are constants.

So, by differentiating Equation (11) and substituting it into Equation (12), we obtain

and then

resulting in

This means that curve is a slant helix. If we rewrite Equation (11), we obtain the following second-order linear ordinary differential equation (ODE) with variable coefficients:

Assuming , we can obtain differential equations for all coordinate functions of the curve :

Solving these differential equations, we obtain the coordinate functions of the curve as follows:

where are constants.

Corollary 1.

Thus, if we have a developable surface, there exists at least one curve α for which every line on the developable surface can serve as a curvature axis at every corresponding regular point. There are, of course, many more if the constant numbers change.

Example 1.

We give a tangent-developable surface example. Let be a standard cylindrical helix:

where its curvature is . The constants are as follows: . Then, from Equations (6), we have

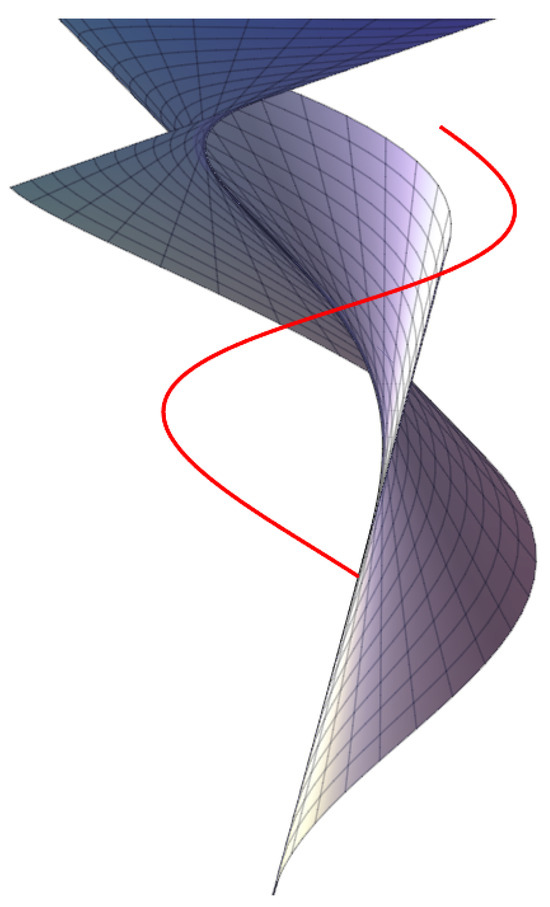

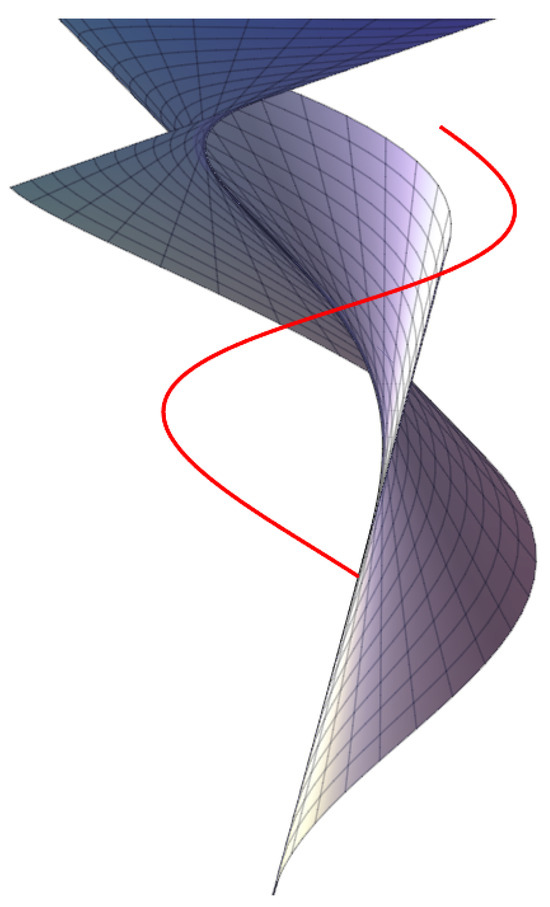

Thus, as can be seen in Figure 4, the curve corresponding to the curve is found.

Figure 4.

The tangent-developable surface corresponding to (red one).

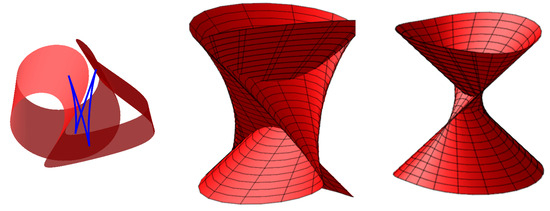

5. Singularities

A singular point on a surface is a point at which the usual rules of calculus, such as continuity or differentiability, break down. Singularities are crucial to understanding the behavior of surfaces, especially in the context of deformations and transformations, and are given special attention in CAGD. Figure 5 shows an example of a surface with a cusp singularity created in Rhinoceros 3D software.

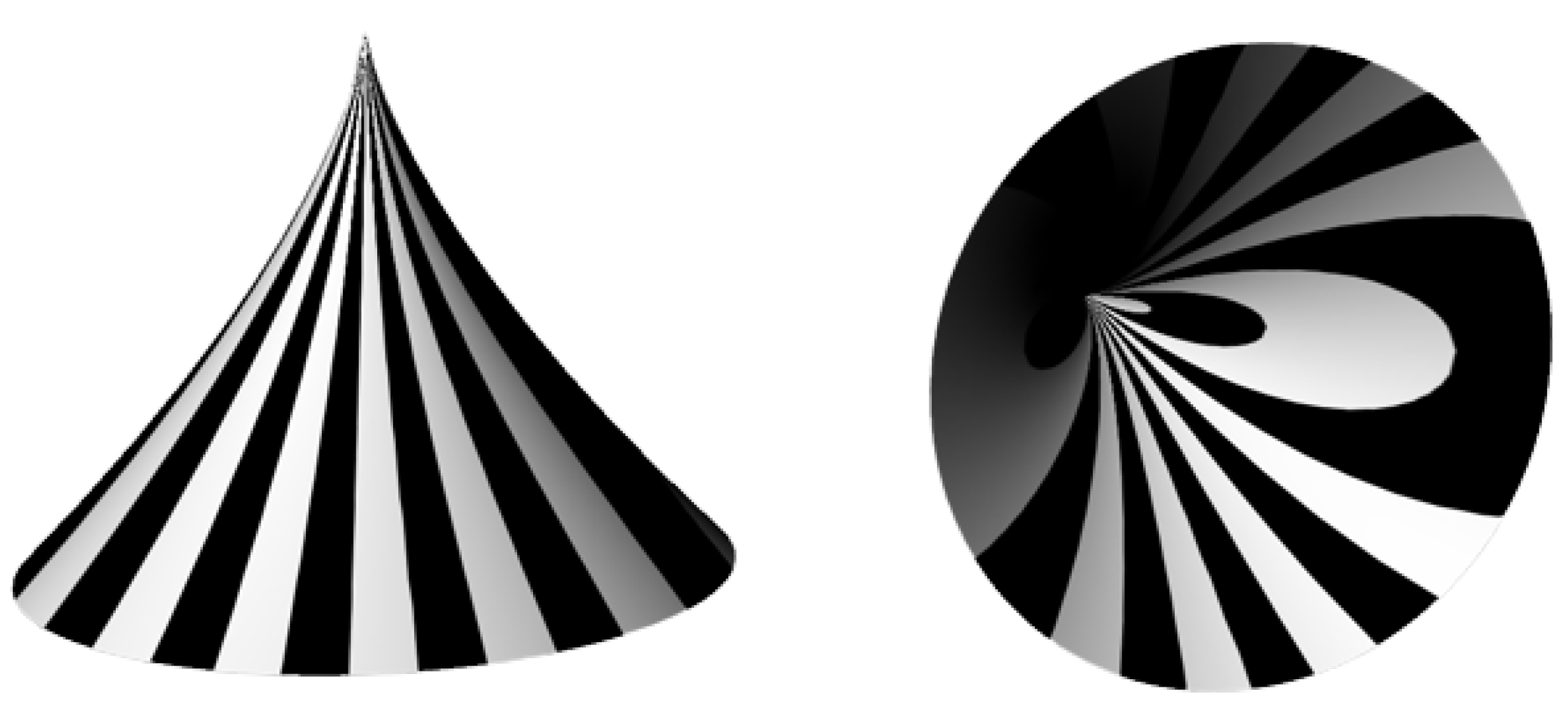

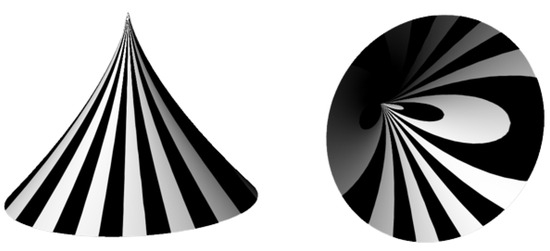

Figure 5.

A surface of revolution with a cusp singularity created by rotating a cuspidal NURBS curve around an axis. Zebra stripes on the outer and inner parts of the surface behave in a specific way around the singularity.

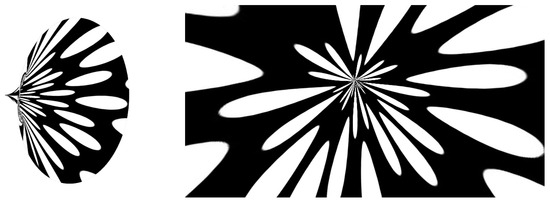

Another good way to illustrate singularities on surfaces is to use an environment map with uniformly distributed white circles on a black background. In this case, the circles will form flower-like patterns around the singularity (Figure 6). An environment map is a surface analysis tool used in CAD systems to visually evaluate surface smoothness, curvature, and other important properties using an image reflected in the surface. In principle, any image can be used as an environment map, and readers interested in environment maps in Rhinoceros 3D software are referred to [35]. Also, readers should not confuse environment maps with environments that have the *.renv file extension.

Figure 6.

Environmental map with a circular pattern applied to the surface with a singularity. White circles tend to be elongated and increase in number around a single point, forming a flower-like pattern.

Combining these concepts, singularities of a developable surface refer to specific points on a developable surface where the surface cannot be flattened smoothly. These points are particularly interesting in applications involving surface unfolding, such as paper folding, sheet metal fabrication, or computer-aided design.

There are several types of developable surface singularities. For example, cusps occur when a surface folds back on itself, creating a sharp point. Imagine folding a piece of paper; the folded corner forms a bump. The other is self-intersection. This occurs when a surface intersects itself. In the context of developable surfaces, this means that the surface folds in such a way that parts of it intersect.

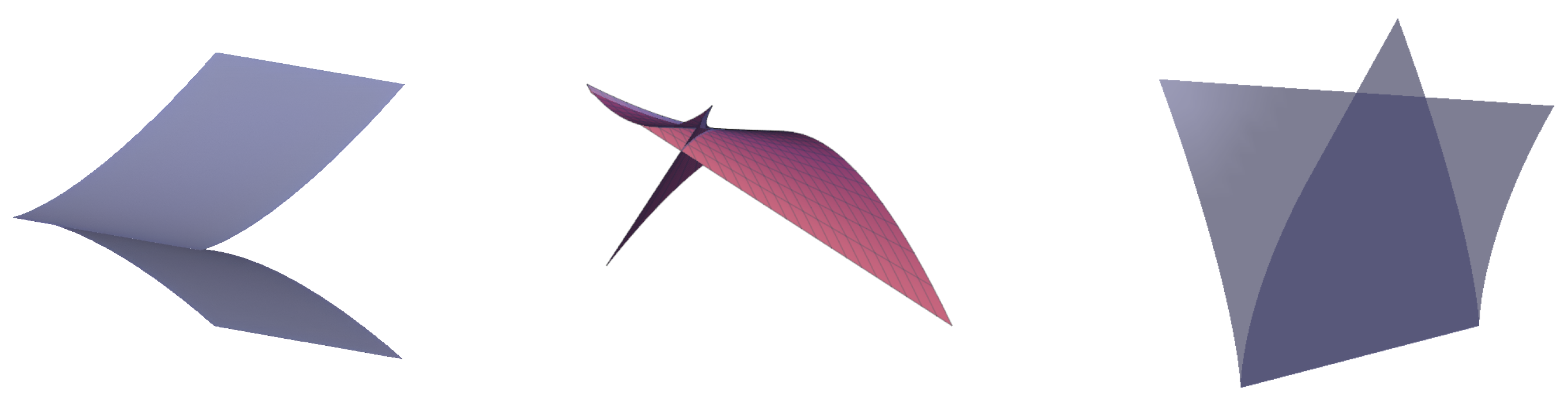

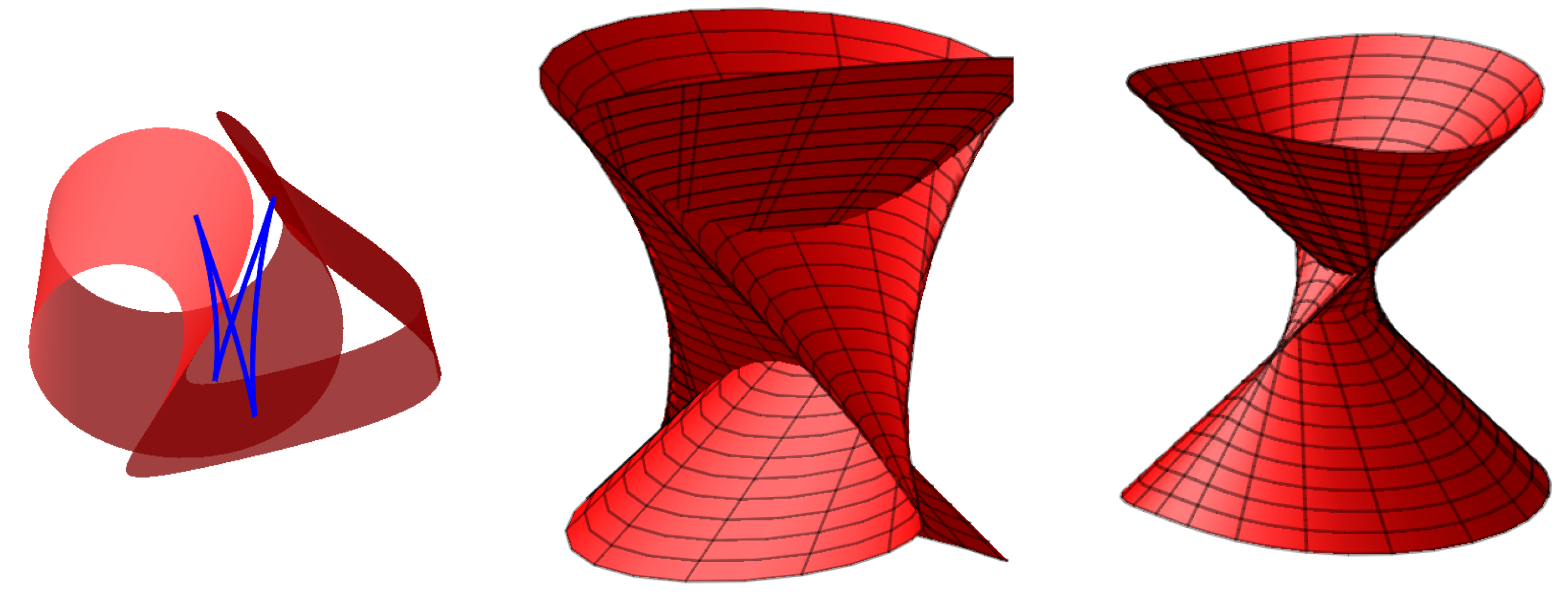

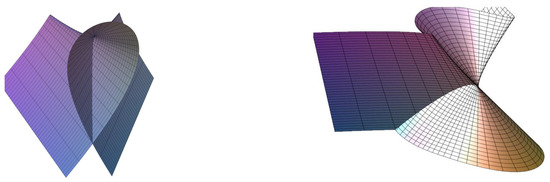

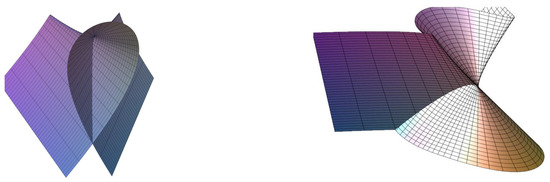

Developable surfaces with singularities are investigated in [21,24]. There are three types of singularities: cuspidal edge, swallowtail, and cuspidal cross-cap, see Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Singular developable surfaces: cuspidal-edge (left), swallowtail (center), and cuspidal cross-cap (right).

These surfaces exhibit singularities along the base curves (see Figure 4) [29]. The base curve of a tangent-developable surface is also its striction curve.

- A tangent-developable surface is considered a cuspidal edge surface along if .

- The tangent-developable surface of a space curve possesses a cuspidal cross-cap singularity at if and .

These conditions are considered generic for space curves, making the cuspidal cross-cap singularity a common singularity of tangent-developable surfaces.

Now we can check the conditions for space curves that correspond to tangent-developable surfaces. We know that the striction curve of the tangent-developable surface carries the singularity of the surface. So these regular curves ( in (6)) correspond to regular curves .

Vise-versa, we can construct developable surfaces via the curvature axis of singular space curves.

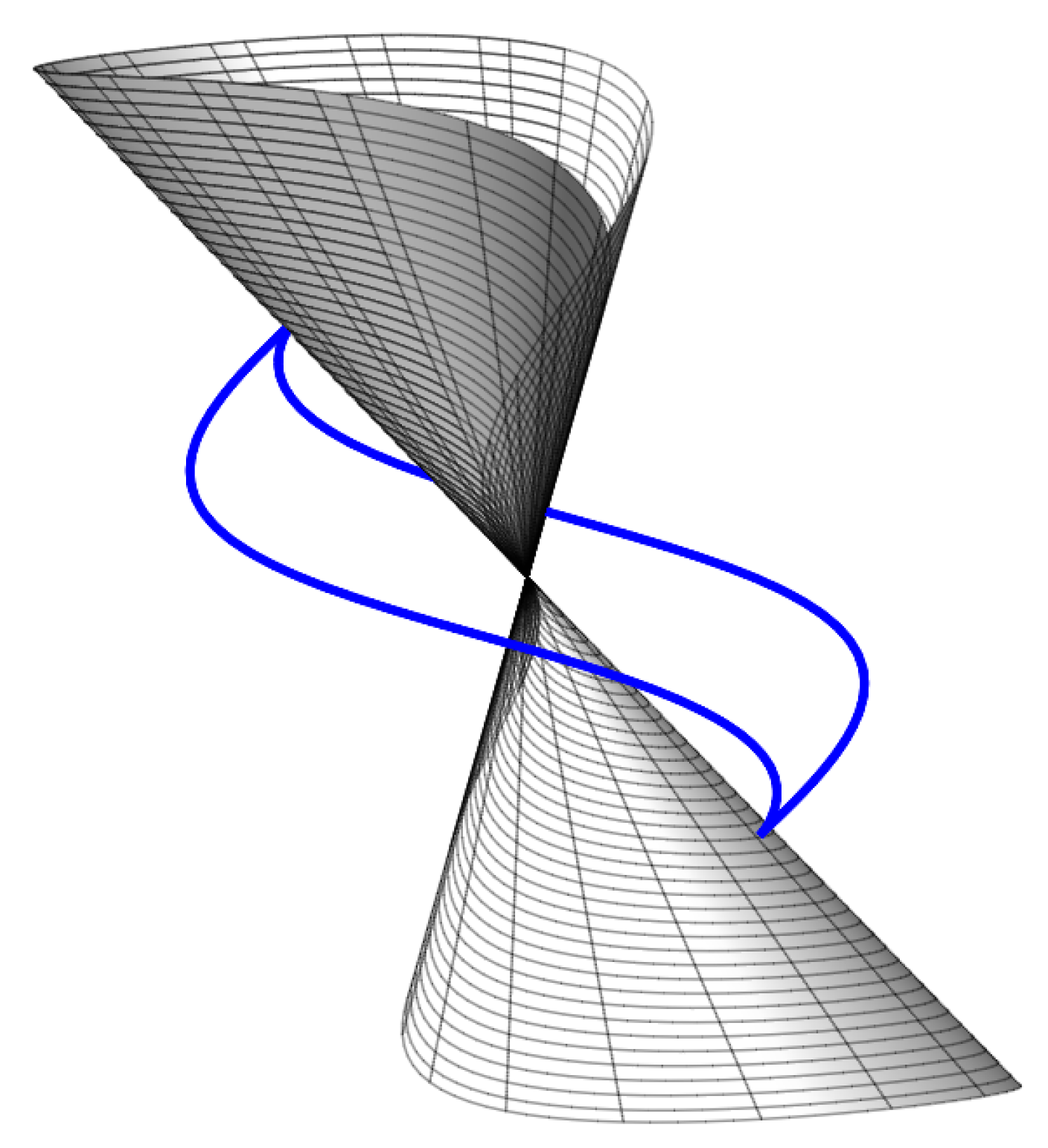

This time, we have a space curve whose tangent vanishes identically at a point . Therefore, we can state the following theorem:

Theorem 3.

Let α be a space curve that is singular at . Then, the developable surface generated by the curvature axis of α has a singularity.

Example 2

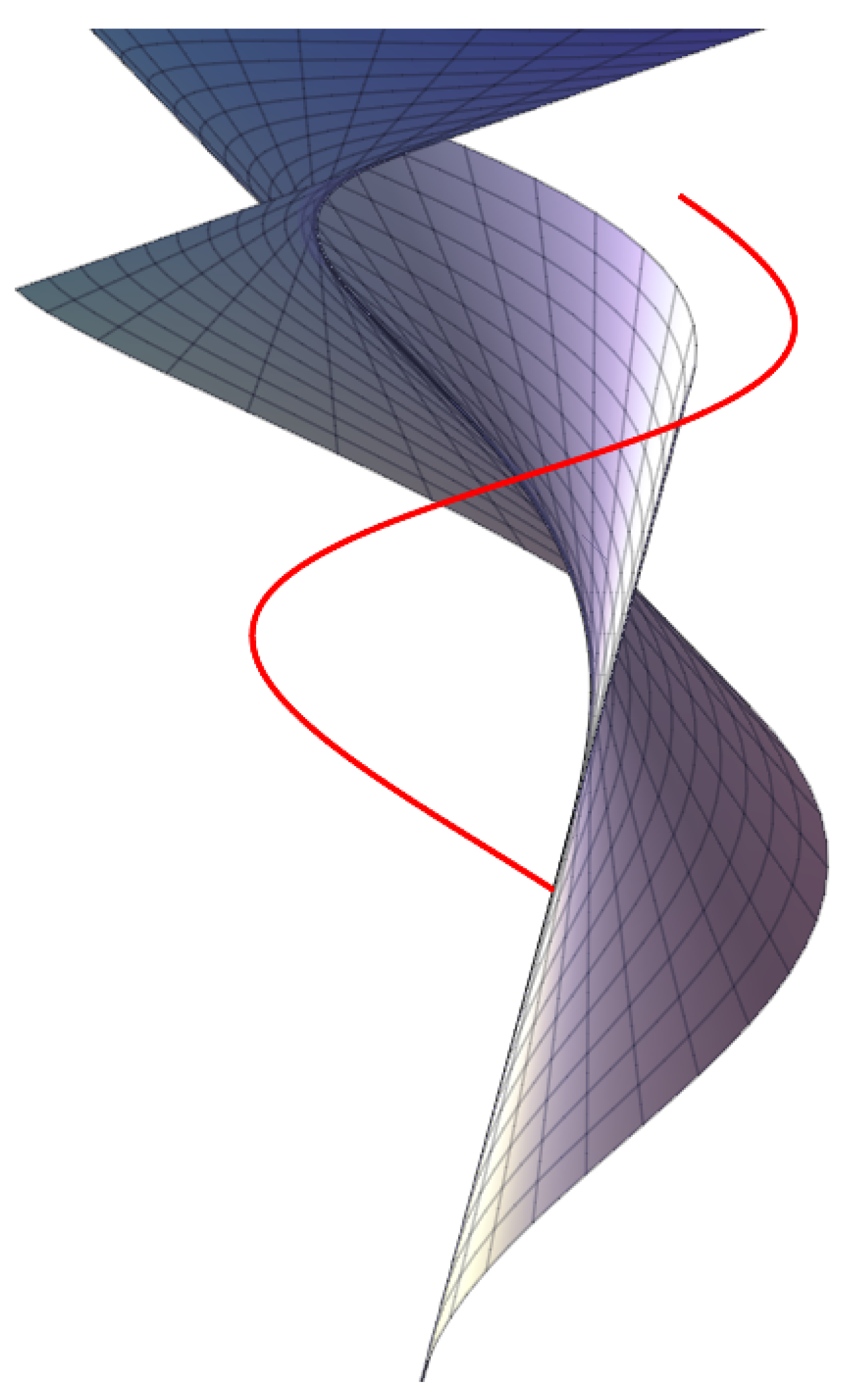

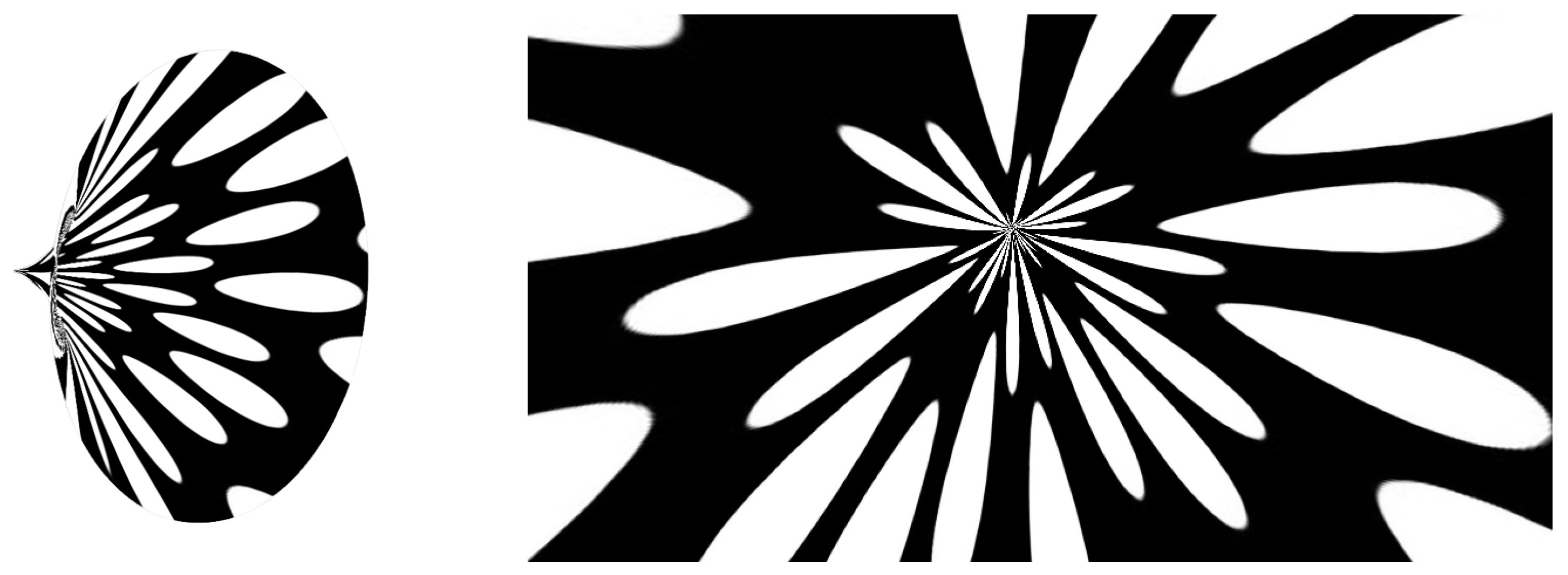

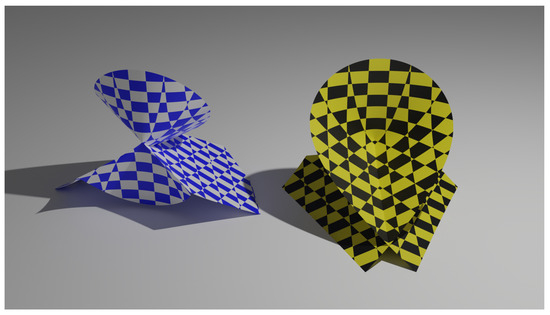

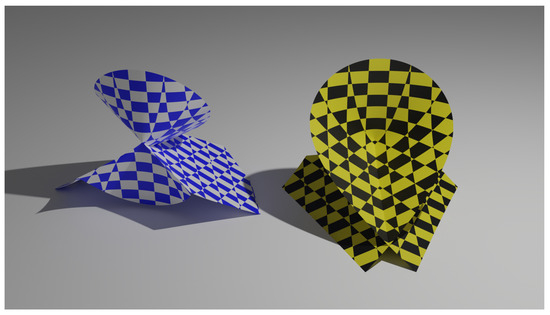

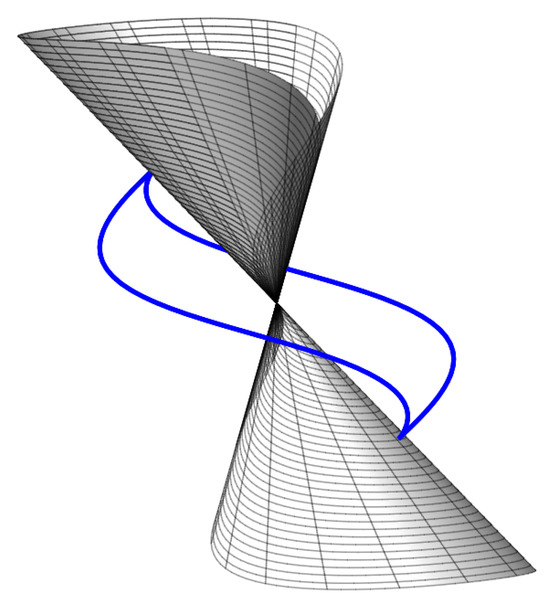

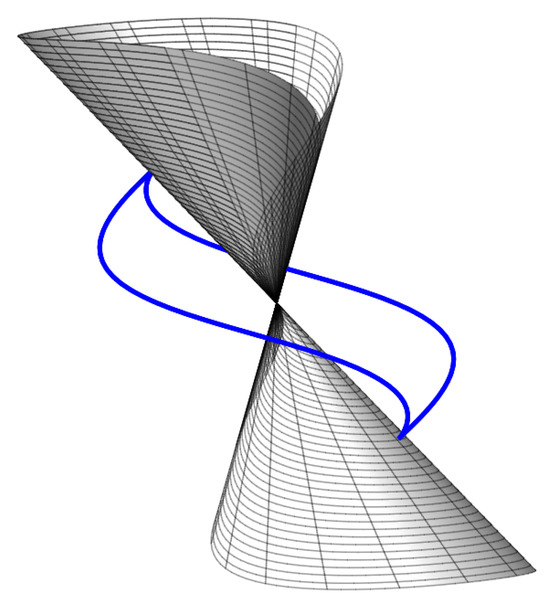

(3D Twisted Curve). For example, consider the parametric singular space curve . Obviously, the curve has a singularity at the origin. If we calculate the curvature axis of this curve from Equation (6), then we have a cuspidal cross-cap swallowtail developable surface; see Figure 8 and Figure 9. This is a fascinating result.

Figure 8.

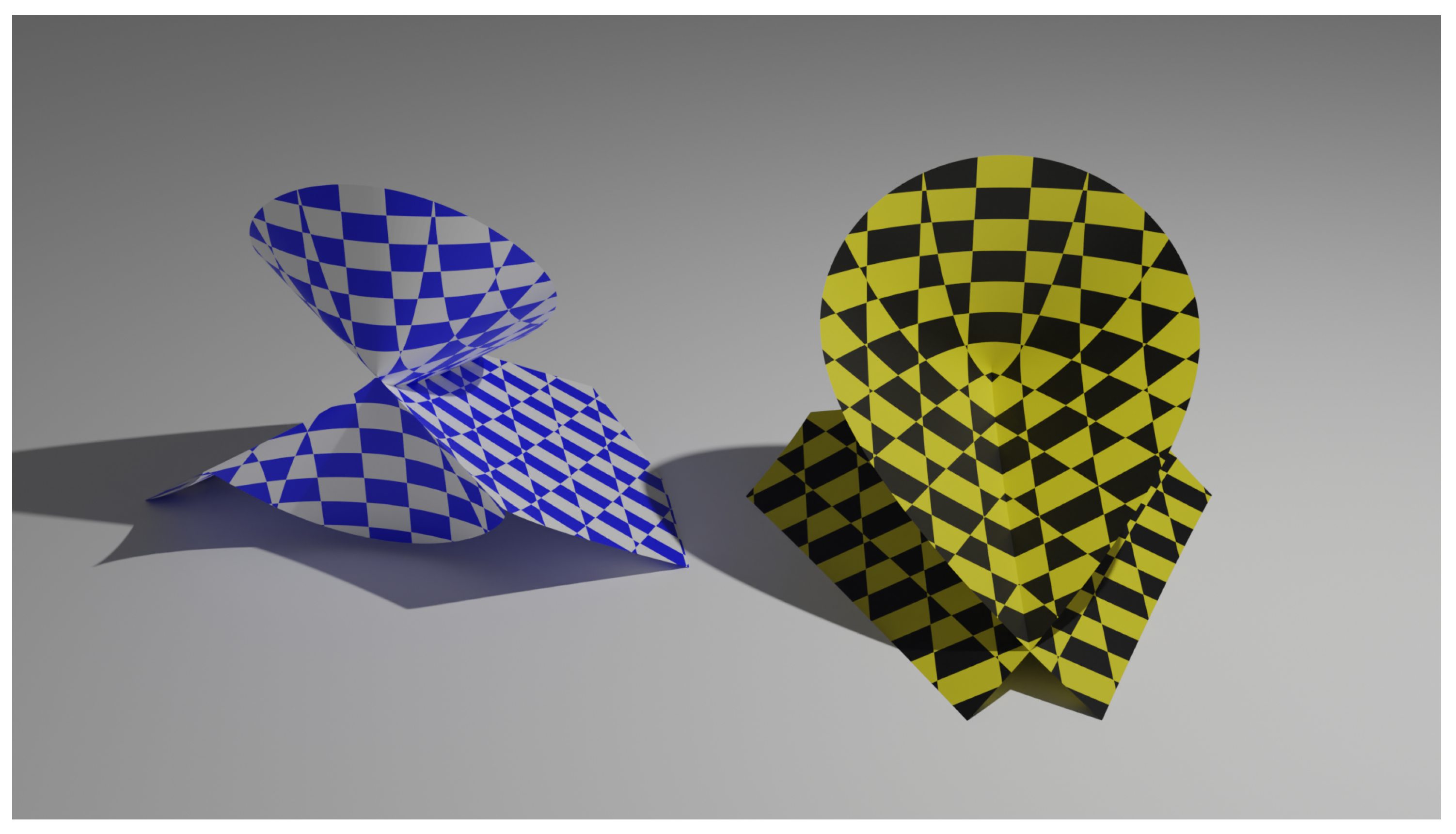

Cuspidal cross-cap swallowtail developable surface generated by the curvature axis of the singular space curve .

Figure 9.

Cuspidal cross-cap swallowtail developable surface visualisation using checker textures, where self-intersection and singularity point are not clearly visible. The example shows that other surface quality methods such as zebra lines or Gaussian curvature visualisation can be used, or an environmental map with a circular pattern can be applied.

We can provide two more examples of singular space curves for the construction of singular developable surfaces.

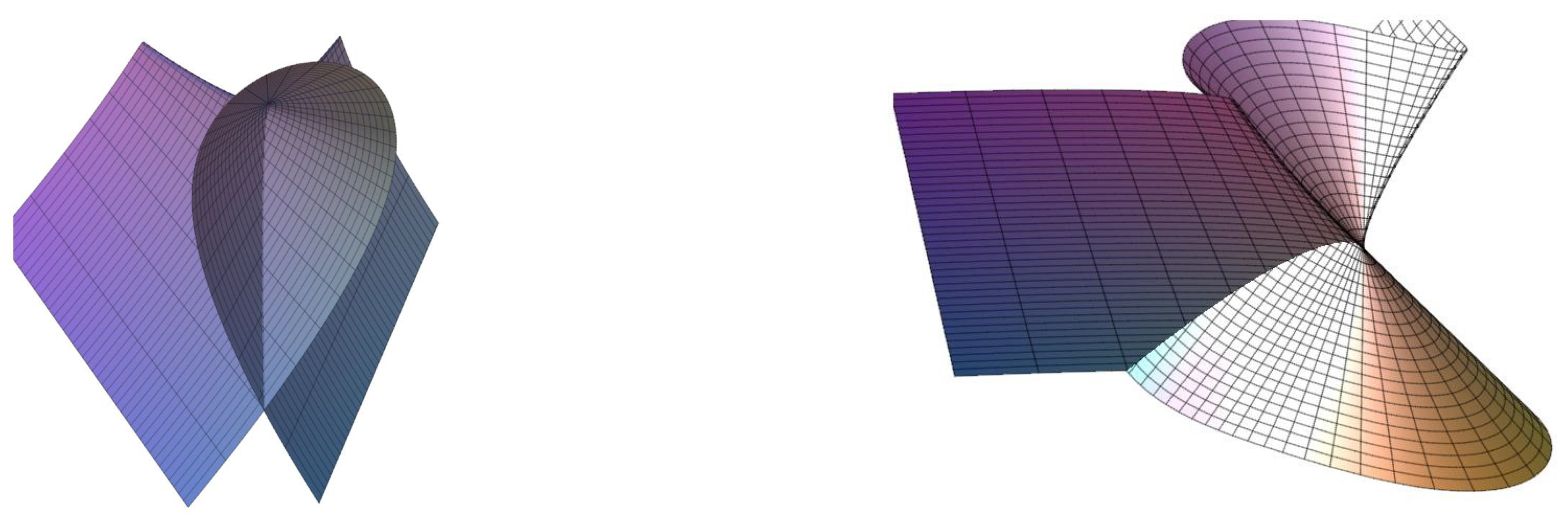

Example 3

(3D Asteroid Curve). Let α be parametrised as . Then, its singular developable surface is described as follows (see Figure 10):

Figure 10.

Singular developable surfaces associated with the 3D asteroid curve (blue). From left to right: different values of .

Example 4

(The Spherical Nephroid Curve). Let α parametrised as

then we obtain a cone-type singular developable surface (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The spherical nefroid and its singular developable surface.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Work

Motion is an essential component of our lives. The geometry of lines is one of the most practical areas of geometry, and the motion of the curvature axis is a classic topic in differential geometry. In this study, we examined the motion of the curvature axis of a curve that generates a ruled surface in space. We also demonstrated that for each developable surface, there exists at least one space curve whose curvature axis coincides with any line on the ruled surface. Thus, we established a correspondence between space curves and developable surfaces. Additionally, we shed light on the classifications of developable surfaces corresponding to space curves with singularities. Our research also contributes to the understanding of the singularities of developable surfaces, such as those that can be generated by moving a line along a cuspidal evolute of log-aesthetic curves [36] approximated by Bézier curves.

Ruled surfaces are mathematically simple and elegant, and their practical implementation has a long history. However, new types of curves are being discovered that can be used as generators of ruled surfaces in the near future. For example, there is currently an interest in high-quality shapes that include log-aesthetic curves [36,37,38] and superspirals [39], and these curves can be used to generate high-quality and aesthetic ruled surfaces. Such an approach may have applications in automotive and road design, as well as shipbuilding. We would also be interested in applying our work to the study of umbrella surfaces [40].

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers for their critical comments, which have undoubtedly helped to improve the quality of our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAGD | computer-aided geometric design |

| CAD | computer-aided design |

| ODE | ordinary differential equation |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

Appendix A. Ruled Surfaces in Art

Barbara Hepworth is a British sculptor. Her work is exhibited in many countries. See Figure A1 for some images of her art.

Figure A1.

Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures related to ruled surfaces (copyright for personal or educational use only from https://barbarahepworth.org.uk/, accessed on 22 October 2023).

Figure A1.

Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures related to ruled surfaces (copyright for personal or educational use only from https://barbarahepworth.org.uk/, accessed on 22 October 2023).

References

- Study, E. Geometrie der Dynamen. In Druck und Verlag von BG Teubner; Mathematiker Deutschland Publisher: Leibzig, German, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Pottmann, H.; Wallner, J. Computational Line Geometry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tas, F.; Gürsoy, O. On the Line Congruences. Int. Electron. J. Geom. 2018, 11, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, F.; İlarslan, K. A new approach to design the ruled surface. Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 2019, 16, 1950093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, P.; Fan, H.; Bartoň, M. Efficient 5-axis CNC trochoidal flank milling of 3D cavities using custom-shaped cutting tools. Comput. Aided Des. 2022, 151, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.H.; Wang, C.C.; Tsai, C.R. Computer aided geometric design of strip using developable Bézier patches. Comput. Ind. 2008, 59, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peternell, M. Developable surface fitting to point clouds. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2004, 21, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Wang, R.H.; Zhu, C.G. An approach for designing a developable surface through a given line of curvature. Comput. Aided Des. 2013, 45, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoston, M.K.; Agoston, M.K. Computer Graphics and Geometric Modeling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Jambrina, L. B-spline control nets for developable surfaces. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2007, 24, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Röschel, O. Developable (1, n)-Bézier surfaces. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 1992, 9, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravani, B.; Ku, T.S. Bertrand offsets of ruled and developable surfaces. Comput. Aided Des. 1991, 23, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziatdinov, R.; Nabiyev, R.; Kim, H.; Lim, S.H. The Concept of a Dew Collection Device Based on the Mathematical Model of Sliding Liquid Drops on an Inclined Solid Surface. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 272, p. 022091. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J. An Overview of Developable Surfaces in Geometric Modeling. Recent Patents Eng. 2022, 16, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumiya, S.; Takeuchi, N. New special curves and developable surfaces. Turk. J. Math. 2004, 28, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, S. Developable surfaces: Their history and application. Nexus Netw. J. 2011, 13, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottmann, H.; Wallner, J. Approximation algorithms for developable surfaces. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 1999, 16, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Bo, P.; Wallner, J.; Pottmann, H. Interactive design of developable surfaces. Acm Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2016, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pottmann, H.; Wallner, J.; Yang, Y.L.; Wang, W. Geometric modeling with conical meshes and developable surfaces. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2006 Papers; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 681–689. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, G.; Gruber, F. Developable surfaces in contemporary architecture. J. Math. Arts 2007, 1, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, G. Singularities of developable surfaces. In London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant, J.S.; Maekawa, T. Design for manufacturing using B-spline developable surfaces. J. Ship Res. 1998, 42, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.T.; Aziz, H.S.A.; Sorour, A.H. Ruled surfaces generated by some special curves in Euclidean 3-Space. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 2013, 21, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumiya, S.; Romero Fuster, M.C.; Ruas, M.A.S.; Tari, F. Differential Geometry from a Singularity Theory Viewpoint; World Scientific Publishing Co., Pte. Ltd.: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lipschutz, M.M. Schaum’s Outline of Theory and Problems of Differential Geometry; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Struik, D.J. Lectures on Classical Differential Geometry; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Somasundaram, D. Differential Geometry: A First Course; Alpha Science Int’l Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Umehara, M.; Yamada, K. Differential Geometry of CURVES and Surfaces; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abbena, E.; Salamon, S.; Gray, A. Modern Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces with Mathematica; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hacisalihoglu, H.H. Diferensiyel Geometri; Inonu University Yayinlari: Malatya, Turkey, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, H.; Poole, C.P.; Safko, J.L. Classical Mechanics, 3rd ed.; Addison Wesley: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; ISBN 0201657023. [Google Scholar]

- Cassiday, G.L.; Fowles, G.R. Analytical Mechanics; Saunders College: Rochester, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos with Student Solutions Manual: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Jung, S.D. Ruled invariants and total classification of non-developable ruled surfaces. J. Geom. 2022, 113, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emap. Rhino. Available online: https://docs.mcneel.com/rhino/5/help/en-us/commands/emap.htm (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Yoshida, N.; Saito, T. Interactive aesthetic curve segments. Vis. Comput. 2006, 22, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, N.; Fukuda, R.; Saito, T. Log-aesthetic space curve segments. In Proceedings of the 2009 SIAM/ACM Joint Conference on Geometric and Physical Modeling, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–8 October 2009; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, K.T.; Suzuki, S.; Gobithaasan, R.U.; Usuki, S. A new log-aesthetic space curve based on similarity geometry. Comput. Aided Des. Appl. 2019, 16, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziatdinov, R. Family of superspirals with completely monotonic curvature given in terms of Gauss hypergeometric function. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2012, 29, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.; Suzuki, A.; Maekawa, T.; Takizawa, K. Geometric modeling of umbrella surfaces based on piecewise bilinear surfaces. Proc. Des. Syst. Conf. 2021, 31, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).