Abstract

Residuated basic logic () is the logic of residuated basic algebras, which constitutes a conservative extension of basic propositional logic (). The basic implication is a residual of a non-associative binary operator in . The conservativity is shown by relational semantics. A Gentzen-style sequent calculus , which is an extension of the distributive full non-associative Lambek calculus, is established for residuated basic logic. The calculus admits the mix-elimination, subformula, and disjunction properties. Moreover, the class of all residuated basic algebras has the finite embeddability property. The consequence relation of is decidable.

MSC:

17B35; 03G25

1. Introduction

The term ‘subintuitionistic logic’, as described in [1,2], covers logics in the language of intuitionistic logic () that are defined in the same manner as intuitionistic logic but lack some conditions on the Kripke semantics. Basic propositional logic (), which was introduced by Visser [3], is the subintuitionistic logic characterized by the class of all transitive frames. It is well known that is embedded into the modal logic via the Gödel-McKinsey-Tarski translation (see, e.g., [4]). It is also known that is embeddable into the modal logic ([1,3,5,6]). Basic propositional logic exists in the common part of and Visser’s formal provability logic . Visser [3] observed that is embeddable into the Gödel-Löb modal logic , which is incomparable with the modal logic . In the modal respect, the modal logic exists in the common part of and . Hence, the role of as a basis for and is analogous to the role of as the basis for and .

Basic propositional logic is a significant form of constructive logic. Ruitenburg [7] commented that a truly constructive logic should admit an interpretation that is non-circular and constructive in itself. Intuitionistic calculus does not satisfy this constraint. Gentzen [8] observed that the Brouwer-Heyting-Kolmogorov (BHK) interpretation of intuitionistic logic is circular in the proof semantics of implication. For example, to understand the meaning of the claim that a is a proof of in the sense of the BHK interpretation, implication elimination is equivalent to the full modus ponens axiom . In this case, the existence of a proof of from involves implication by the assumption , and hence the interpretation of the implication is circular. Ruitenburg [7] developed the truly constructive logic (basic propositional calculus), which is not circular and turns out to be equivalent to Visser’s natural deduction system for . The Kripke semantics for were originally given by Visser [3], while the soundness and completeness of under the Kripke semantics were presented by Ardeshir and Ruitenburg [9,10].

Visser’s propositional logics have been studied in, e.g., [6,9,10,11,12,13]. In the proof-theoretic respect, Gentzen-style sequent calculi for basic propositional logics are given in [14,15,16,17]. In this paper, we shall study from the perspective of substructural logics. Substructural logics are logics that drop some structural rules in sequent formalizations. Many well-known logics are substructural, such as Lambek calculus, ukasiewicz many-valued logics and relevant logics. Algebras for substructural logics are given by residuated lattices [18,19,20,21]. We shall introduce residuation into . The basic implication in is that there is no right residual of any binary operator in the language of . Thus, we introduce a new binary operator • (product), which satisfies additional conditions such that the basic implication is a residual of the product. The resulting logic is called residuated basic logic (). Algebras for are defined as bounded distributive lattices with residuation pairs and , where • satisfies the conditions of weakening and strong contraction. We prove that the basic sequent system for is a conservative extension of .

In the present paper, the Gentzen-style sequent calculus will be established for . This calculus is obtained from the distributive full non-associative Lambek calculus () by adding the structural rules of weakening and strong contraction. is obtained from the full non-associative Lambek calculus () by adding distributivity [22]. The logic [18] is obtained by adding all lattice operations and their rules to the non-associative Lambek calculus . The calculus was originally introduced by Lambek [23], and it is strongly complete with respect to residuated groupoids [18]. with unit, i.e., the groupoid logic, is studied in [24]. The associative variant (Lambek calculus) of was also introduced by Lambek [25], and it is strongly complete with respect to residuated semigroups). We shall prove that admits mix-elimination, the subformula property, and the disjunction property. The finite embeddability property (FEP) of residuated basic algebras shall be proved by applying the method of Haniková and Horčík [26]. The decidability of follows from the FEP.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 gives preliminaries on the basic propositional logic. Section 3 introduces residuated basic algebras and proves the finite embeddability property. Section 4 introduces residuated basic logic and its basic sequent calculus and proves that is a conservative extension of . Section 5 introduces the Gentzen-style sequent calculus for and proves the mix-elimination, subformula property, and decidability. Section 6 gives some concluding remarks.

2. Preliminaries

We recall some basic concepts and results on basic propositional logic, which can be found in [3,9,13]. The language of consists of a denumerable set of propositional variables and connectives , and ⊤.

Definition 1.

The set of all BPL-formulas is defined inductively by the following rule:

The complexity of a BPL-formula α is defined as the number of occurrences of binary connectives in α. A basic BPL-sequent is an expression of the form where α and β are BPL-formulas.

Definition 2.

A BPL-frame is a pair , where W is a nonempty set of states (possible worlds) and R is a transitive binary relation (accessibility relation) on W. A BPL-model is a tuple , where is a transitive frame, and is a valuation function from to the powerset of W satisfying the following persistency condition:

For every BPL-model , the truth of a BPL-formula α at a state in (notation: ) is defined inductively as follows:

iff .

and .

iff and .

iff or .

iff for all , if and , then .

A BPL-formula α is true in (notation: ) if for all .

For every BPL-frame , let , namely the reflexive closure of R. A basic BPL-sequent is true at a state w in (notation: ) if for all , if and , then . We say that is true in (notation: ) if for all . A BPL-formula α is valid (notation: ) if it is true in every BPL-model. A basic BPL-sequent is valid (notation: ) if is true in every BPL-model.

Proposition 1

(Persistency). For every BPL-model and BPL-formula α, if and , then .

Proof.

The proof proceeds by induction on the complexity of . Here we show only the case . Assume and . Suppose and . By and , we have . Furthermore, . Hence . □

The set of all valid BPL-formulas is finitely axiomatizable. A Hilbert-style axiomatic system, , can be found in Ono and Suzuki [13]. In the present paper, we shall use the basic propositional calculus () of basic BPL-sequents proposed by Ardeshir and Ruitenburg [9]. It is easy to observe that a BPL-formula is a theorem of if and only if the basic sequent is derivable in .

Definition 3.

The basic propositional calculus consists of the following axioms and rules:

- (1)

- Axioms:

- (A1)

- (A2)

- (A3)

- (A4)

- (A5)

- (A6)

- (A7)

- (2)

- Rules:

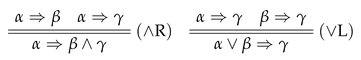

The double line in and means the sequents are derivable from each other.

A basic BPL-sequent is provable in (notation: ) if it is an axiom or derivable by a rule in .

Theorem 1

(Soundness and Completeness). For every basic BPL-sequent , if and only if .

Proof.

The soundness is easily verified by induction on the length of a derivation in . The completeness follows from the strong completeness result given in ([9], Theorem 3.7.)

□

The basic sequent system can also be characterized by basic algebras which are studied in, e.g., [11,15].

Definition 4.

An algebra is a basic algebra if its -reduct is a bounded distributive lattice, and → is a binary operator on A such that for all :

- (1)

- .

- (2)

- .

- (3)

- .

- (4)

- .

- (5)

- .

The binary operator → in a basic algebra is called the basic implication. The variety of all basic algebras is denoted by .

Fact 1

(cf. [11]). For every basic algebra and , the following hold:

- (1)

- if , then , and .

- (2)

- if , then .

- (3)

- is a Heyting algebra if and only if for all .

Let be a BPL-frame. For every and subset , let and . A subset is called an upset in if . Let be the set of all upsets in . It is easy to see that , and that is closed under ∩ and ∪. Define a binary operation by

The operation is well defined since is an upset if X and Y are upsets. The dual algebra of is defined as . Clearly is a basic algebra.

Definition 5.

Given a basic algebra , an assignment in is a function . For every assignment θ in , the function is defined as follows:

A basic BPL-sequent is valid in (notation: ) if for every assignment θ in . By we denote that is valid in all basic algebras.

Theorem 2.

For every basic BPL-sequent , if and only if .

Proof.

The soundness is easily shown by induction on the derivation of in . The completeness is shown by the standard Lindenbaum-Tarski construction (cf. [9,11,15]).

□

Now we define an alternative basic sequent system, , for basic algebras which shall be used in the following section.

Definition 6.

The basic sequent system consists of the following axioms and rules:

- (1)

- Axioms:

- (2)

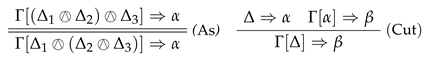

- Logical rules:

- (3)

- Cut rule:

A basic BPL-sequent is provable in (notation: ) if it is an axiom or derivable by a rule in . The prefix is omitted if no confusion arisse.

Theorem 3.

For every basic BPL-sequent , if and only if .

Proof.

The soundness is verified by induction on the length of a derivation in . The completeness is shown by the standard Lindenbaum-Tarski construction. Here, we give a sketch of the proof. The equivalence relation ≈ on the set of all BPL-formulas is defined by setting if and only if and . By the axioms and rules of , one can show that ≈ is a congruence relation. Let be the equivalence class for each BPL-formula . Furthermore, we have the Lindenbaum-Tarski algebra where is the quotient set of A modulo ≈. Suppose . Furthermore, . Let be the assignment in such that for each . By induction on the complexity of a formula , we have . Hence . Clearly . It follows that . □

By the standard Lindenbaum-Tarski construction, it is easy to show that is sound and complete with respect to , namely, for every basic BPL-sequent , if and only if . Furthermore, we get the following corollary.

Corollary 1.

For every basic BPL-sequent , (1) if and only if ; and (2) if and only if .

Proof.

It follows immediately from Theorems 1–3. □

3. Residuated Basic Logic

The Heyting implication in intuitionistic logic is the residual of ∧, i.e., for all in a Heyting algebra, if and only if . However, the basic implication is not a residual of ∧ in a basic algebra. Let us introduce a binary operator • (product) such that the basic implication is one of its residuals. For this purpose, we introduce residuated basic algebras. Furthermore, we shall prove the finite embeddability property of the variety of all residuated basic algebras.

3.1. Residuated Basic Algebras

An algebra is a residuated groupoid if is a partially ordered set, and and ← are binary operators on A such that for all :

Note that the associativity of the operator • is not assumed here.

Definition 7.

An algebra is a residuated basic algebra (RBA) if is a bounded distributive lattice, and is a residuated groupoid satisfying the following conditions for all :

where ≤ is the lattice order. These conditions for the product were studied by Restall [2,21,27]. Restall proved that these conditions are warranted by formulas. For example, the condition (Restall’s condition (Syll) [27]) is warranted by the formula . Let be the class of all RBAs.

For every RBA , it is easy to check that (i) , and (ii) (the least upper bound).

Remark 1.

The -reduct of a residuated basic algebra is not assumed to contain a unit. The condition differs from the ordinary contraction , and the name ‘strong contraction’ was proposed for by Restall [21]. The contraction is derivable from if the residuated groupoid reduct contains a unit. Thus, the unit is equal to ⊤ by , and hence , which does not hold in basic algebras.

Example 1.

Let , where and are defined as usual, namely, and . The operations and ← on A are given as follows:

It is easy to check that → and ← are residuals of • in the first and second coordinates, respectively. The product also satisfies and . Furthermore, is an RBA. Its -reduct is not a Heyting algebra because when .

Proposition 2.

For every residuated algebra and , the following hold:

- (1)

- .

- (2)

- .

- (3)

- if , then and .

- (4)

- if , then and .

- (5)

- if , then and .

Proof.

Clearly (3), (4), and (5) are monotonicity laws that hold in every residuated groupoid. By (3), and imply that . We show (1) and (2) as follows:

- (1)

- By and , we have and . Furthermore,, , which yields . Conversely, from and , by (3) we get and . Furthermore, .

- (2)

- By and , and . Furthermore,, by (3) we get . By , we get . By , .

□

Theorem 4.

The -reduct of any residuated basic algebra is a basic algebra.

Proof.

Let be a RBA. Clearly is a bounded distributive lattice. We check the conditions for basic algebras as follows:

- (1)

- Assume . By (RES), . By and , we get and . Furthermore, and . Hence, . Conversely, assume . Furthermore,, and . By (RES), and . Furthermore, . Furthermore, . Hence .

- (2)

- Assume . By (RES), . Because , we have . Furthermore,, . Similarly . By (RES), and . Hence, . Conversely, assume . Furthermore, and . By (RES), and . Furthermore, . By Proposition 2 (1), . Furthermore, . Hence .

- (3)

- Clearly . By , we have .

- (4)

- By , we have . By (RES), .

- (5)

- Assume . Furthermore, and . By (RES), and . By Proposition 2 (3), . By , we get . By (RES), . Hence .

□

3.2. Finite Embeddability Property

In this subsection, we apply the method of Haniková and Horčík [26] to prove the finite embeddability property (FEP) of residuated basic algebras. Here we recall some basic concepts. Let be an algebra of any type and . We say is a partial subalgebra of if for every n-ary function with , and for every ,

If is ordered by , we define as the restriction of to . If we want to stress that a function acts on , we write , but usually we drop it.

An embedding from an algebra into is an injection such that for every , if , then . If and are ordered, then h is required to be an order embedding, i.e., h satisfies the condition . A class of algebras has the FEP if every finite partial subalgebra of a member of can be embedded into a finite member of .

Let be a poset. A map is called a closure operator on P if it satisfies the following conditions for all :

- () ,

- () if , then ,

- () .

An element is called -closed if . A map is called an interior operator on P if it satisfies the following conditions for all :

- () ,

- () if , then ,

- () .

An element is called -open if .

Let be an RBA, and (with universe B) be a finite partial subalgebra of . It suffices to find a finite residuated basic algebra into which is embedded. Let the universe of be denoted by E. As in [26], we first obtain a bounded distributive lattice that is the bounded sublattice generated by B from , where and . Since B is finite, the distributive lattice is also finite and hence complete. Now we show that every element in A can be mapped to the least element in E above itself or the greatest element in E below itself. For each , the maps and on are defined as follows for every :

Note that for every , and exist. Moreover, is a closure operator and is an interior operator on . For every , we have . For every , the binary operations on E are defined as follows:

This completes the definition of the finite algebra .

Lemma 1.

The algebra belongs to .

Proof.

By Haniková and Horčík [26], clearly is a bounded distributive lattice ordered residuated groupoid. We recall the proof of residuation law here. Let . Furthermore,

Similarly if and only if . Now we prove satisfies , and . For , let . It suffices to show . By and , we have . Note that for all . Furthermore, . The proof of is similar. For , let . It suffices to show . By (), . By Proposition 2 (3), . By (), . By and (), . Clearly for every . Furthermore, . Hence is a RBA. □

Lemma 2.

The partial algebra is embeddable into .

Proof.

We show that the identity map is an embedding. Obviously and . It suffices to show that f preserves all operators. First, f preserves ∧ and ∨, since E is a sublattice of A generated by B. Note that and for all . Furthermore, , , and . □

Theorem 5.

The variety of residuated basic algebras has the FEP.

Proof.

It follows immediately from Lemmas 1 and 2. □

Corollary 2.

The variety of basic algebras has the FEP.

The FEP usually has consequences for the finite model property and decidability. Here we outline the proof of the universal finite model property and decidability. Consider the first-order language of algebras in . Atomic formulas are inequalities of the form where are terms. Notice that these terms are RBL-formulas in our case. A first-order formula is quantifier-free if no quantifiers occur in it. A universal sentence is a sentence of the form , where is quantifier-free and is the sequence of variables occurring in . A Horn sentence is a universal sentence where and each ) is atomic. The universal theory of is the set of all universal sentences that are valid in . The Horn theory of is the set of all Horn sentences that are valid in .

Now we show that the FEP implies the universal finite model property. Namely, every universal sentence refuted by a member of can be refuted by a finite member of . Assume that has the FEP and . Furthermore, there exists an algebra such that . Thus, there exist such that . Let be a subterm of . Furthermore, B forms a finite partial subalgebra of . By the FEP of , there exists an embedding for some finite . Since h is an embedding and , the preservation of first-order formulas under the embedding implies that . Furthermore, . This completes the proof of the universal finite model property of . It follows that the universal theory of and hence the Horn theory of are decidable.

4. Conservative Extension

Now we introduce the residuated basic logic . The language of is the extension of obtained by adding binary operators • and ←. The set of all RBL-formulas is defined inductively by the following rule:

where . A basic RBL-sequent is an expression of the form where and are RBL-formulas. A basic RBL-sequent is valid in a residuated basic algebra , if for every assignment , . The notation means that is valid in all residuated basic algebras.

In the following, we shall introduce a basic RBL-sequent system for residuated basic algebras, and show that is a conservative extension of (cf. Theorem 7).

Definition 8.

The sequent system for residuated basic algebras consists of the following axioms and rules:

- (1)

- Axioms:

- (2)

- Rules:

By we denote that is provable in . The prefix is omitted if no confusion can arise.

Theorem 6.

For every basic RBL-sequent , if and only if .

Proof.

The soundness is easily shown by induction on the proof of a sequent in . The completeness is obtained by the standard Lindenbaum-Tarski construction. □

Lemma 3.

If , then and .

Proof.

Assume . We have the following derivations:

This completes the proof. □

Remark 2.

The axioms , and in are equivalent to the following sequents respectively: ; and . By (R1) and (R2), and are derivable from each other, and and are derivable from each other. Assume (TC) holds. We have the following derivations:

By (Cut), . Clearly (i) and (ii) . By (i) and Lemma 3, and so . By (ii) and Lemma 3, . By (TC), . By (Cut), . By (R1), . Conversely, assume (Tr) holds. Clearly and . By , . By (Tr), . By (Cut), . By (R2), .

Now we show that is a conservative extension of . For this purpose, we give interpretation of the language in BPL-models.

Definition 9.

The satisfaction relation between a BPL-model with a state and an RBL-formula α is defined inductively. Besides the semantic clauses for BPL-formulas, we give the following additional semantic clauses:

- (1)

- iff and for some with .

- (2)

- iff the following conditions hold:

- (C1)

- for all , if and , then ;

- (C2)

- for all , if , and , then .

A basic RBL-sequent is true at w in (notation: ) if for all u, if and , then . Let mean for all . A sequent rule

is admissible in a BPL-model if for all imply .

Lemma 4

(Persistency). For every RBL-formula α, BPL-model , and , if and , then .

Proof.

This follows by induction on the complexity of . The BPL-cases are simple. We show the following two cases:

- (1)

- . Assume and . Furthermore, there exists such that , and . By induction hypothesis, . By the transitivity of R, we have . Hence .

- (2)

- . Assume and . We show . Assume and . By , we have . Now assume , and . By the transitivity of R, we have . By , we have . Thus, .

□

Lemma 5.

For every BPL-model , if , then .

Proof.

The proof proceeds by induction on the proof of in . Let be a BPL-model. The axioms , , and are clearly true in . The remaining axioms are shown to be true in as follows:

Assume and . Furthermore, there exists such that , and . By and Lemma 4, .

Assume and . Furthermore, there exists such that , and . Furthermore, .

The admissibility of rules , and can easily be shown. The admissibility of the residuation rules is shown as follows:

Assume . Suppose and but for some . Furthermore, there exists such that , and . Furthermore, . By the assumption, which yields a contradiction.

Assume . Suppose and but for some . Furthermore, there exists such that , and . By the assumption, . Hence which yields a contradiction.

Assume . Suppose and but for some . There are two cases:

Case 1. There exists such that , but . Furthermore, . By the assumption, which yields a contradiction.

Case 2. There exist such that , , and but . Since and , it follows from Lemma 4 that . Hence . By the assumption, we have which yields a contradiction.

Assume . Suppose , but for some . Furthermore, there exists such that , and . By the assumption, . Furthermore, , which yields a contradiction. □

Theorem 7.

(Conservativity). For every basic BPL-sequent , if and only if .

Proof.

Assume . It is easy to show . Conversely, assume . By Corollary 1, there exists a BPL-model such that . By Lemma 5, we have . □

Since is equivalent to the basic propositional calculus , we obtain that is a conservative extension of .

5. A Gentzen-Style Sequent Calculus for

The system is equivalent to the bounded distributive full Lambek calculus ([18,22]) with weakening axioms and and the strong contraction axiom . We shall introduce a Gentzen-style sequent calculus for , and show that admits mix-elimination. For general details on sequent calculi for substructural logics, see e.g., [20].

5.1. The Sequent Calculus

Definition 10.

Let ⊙ and

be structural operators for the product • and ∧ respectively. The set of all RBL-structures is defined inductively as follows:

We use , etc. for RBL-structures. Each RBL-structure Γ is associated with a formula which is defined inductively as follows:

A RBL-sequent is an expression where Γ is an RBL-structure and . An RBL-sequent is valid in a residuated basic algebra (notation: ) if .

A context is an RBL-structure with a single position − for an RBL-structure. For any context and RBL-structure , is the RBL-structure obtained from by substituting for the position −.

Definition 11.

The sequent calculus consists of the following axiom and rules:

- (1)

- Axiom:

- (2)

- The RBL-structure Γ in and is required to be nonempty. The formula with a connective in a logical rule is called principal.

- (3)

The RBL-structure Λ in is nonempty. The double line in the rule indicates that the premiss and the conclusion can be derived from each other.

A derivation in is a finite tree of sequents in which each node is either an instance of or obtained from a child node(s) by a rule. The height of a derivation is the greatest number of successive applications of rules. An instance of has height 0. We use for that the sequent is derivable in .

Remark 3.

By the definition of , if , then Γ must be nonempty. Hence is not derivable. However is an instance of in . Moreover, the following sequent rule is admissible in :

This rule is half of the associativity.

Theorem 8.

For every RBL-sequent , if and only if .

Proof.

We give an outline of the proof. For the ‘only if’ part, assume . It is easy to show that every basic sequent provable in is derivable in . Furthermore, . By the definition of , . For the ‘if’ part, assume . By the completeness of , there exists an RBA such that . Furthermore,, . Clearly is sound with respect to . Hence . □

5.2. Mix Elimination, Subformula Property and Decidability

We introduce the sequent calculus which is obtained from by replacing the (Cut) rule with the following mix rule:

where denotes the formula structure containing at least one occurrence of , and denotes the formula structure obtained by replacing at least one occurrence of in by the formula structure . The formula in the rule (Mix) is called the mixed formula. Note that (Cut) in is a special case of (Mix), and (Mix) is the finitely many times of application of (Cut). Hence is equivalent to .

Theorem 9

(Mix-elimination). Every RBL-sequent that is derivable in admits a derivation without using .

Proof.

Let an application of (Mix) in a derivation of a sequent in be

where derivations of both premisses do not use (Mix). We prove the mix-elimination by simultaneous induction on (I) the complexity of the mixed formula , (II) the height of a derivation of , and (III) the height of a derivation of . Let be obtained by and by . If is , then and the conclusion is obtained by the right premiss of (Mix). If is , then and is , which is the left premiss of (Mix). Assume is a structural rule, then we apply (Mix) to the premiss(es) and then apply the rule . The case that is a structural rule is quite similar. Now, assume that neither nor is an instance of or a structural rule. We have the following cases:

Case 1. The mixed formula is not principal in . We have the following cases:

- (1.1)

- is . The derivationis transformed intowhere denotes finitely many applications of the rule .

- (1.2)

- is a left logical rule. Apply (Mix) to and the premiss(es) of , and then apply . For example, . The derivationis transformed intowhere denotes finitely many applications of the rule .

Case 2. The mixed formula is principal only in . Furthermore, we have the following cases according to :

- (2.1)

- is a right logical rule. Apply (Mix) to and the premiss(es) of , and then apply . For example, . The derivationis transformed into

- (2.2)

- is a left logical rule. Since is not principal in , we apply (Mix) to and the premiss(es) of and then apply . For example, . The derivationis transformed into

Case 3. The mixed formula is principal both in and . We have the following cases according to the complexity of :

- (3.1)

- . Let the derivation end withBy the induction hypothesis, we have the following derivation:By induction hypothesis on and , we have the following derivation:

- (3.2)

- or . These two cases are similar. Here we show only the case . Let the derivation end withBy induction hypothesis, we have the following derivations:andBy induction hypothesis on , we haveBy induction hypothesis on , we have

- (3.3)

- or . These two cases are similar. Here we show only the case . Let the derivation end withBy induction hypothesis, we have the following derivation:By the induction hypothesis on and , we have

This completes the proof. □

Corollary 3

(Subformula Property). If , then there exists a derivation of in in which every formula is a subformula of formulas in .

Theorem 10

(Disjunction Property). For all RBL-formulas α and β, if , then or .

Proof.

Assume . Furthermore, . By Theorem 9, the last rule of a mix-free derivation of can be only or (). Assume the last application of is . Furthermore, the premiss of is or . By (), or . □

If rules for • and ← are dropped from , we get the sequent calculus with two structure operators

and ⊙. Thus, can be taken as a sequent calculus for basic propositional logic. We have the following result:

Theorem 11.

For every basic BPL-sequent , if and only if .

Proof.

Let be a basic BPL-sequent. By Theorem 7, if and only if . Clearly if and only if . By the subformula property of , if and only if . □

Finally, we consider the consequence relations of sequent calculi and . A sequent is called a consequence of a finite set of sequents in (notation: ) if there exists a derivation of in from sequents in . The consequence relation of is defined similarly. We have shown that has the FEP (Theorem 5). This property implies the universal finite model property (cf. Section 3), which yields the SFMP (cf. e.g., ([19], Chapter 6). It follows that has the strong finite model property (SFMP). That is, for every finite set of sequents , if , then there exists a finite RBA model such that all sequents in are true but is not true in . This result follows immediately from the finite embeddability property of .

Theorem 12.

The consequence relations of and are decidable.

Proof.

By the FEP of , we get the SFMP of and so the SFMP of . Thus, consequence relations of and are decidable. □

6. Concluding Remarks

The present paper makes several contributions to the study of subintuitionistic logics. First, we introduce residuated basic algebras and show the finite embeddability property. Second, the residuated basic logic is shown to be a conservative extension of basic propositional logic. Third, we introduce a cut-free sequent calculus for residuated basic algebras. Finally, the consequence relation of is decidable.

Residuation often appears in algebraic structures, and residuated logics have been developed. Lambek calculi are typical systems for some residuated algebras. The residuated basic logic given in the present paper is obtained by introducing the binary operator • such that the implication in basic propositional logic is one of the right residuals. There are some relevant results in the literature. For example, a logic for residuated paritially ordered sets with a top was developed in e.g., [28]. In the setting of fuzzy logic (cf. e.g., [29]), residuated fuzzy logics arising from continuous t-norms without non-trivial zero divisors and extended with an involutive negation are developed in [30]. Hájeck’s basic logic is quite different from Visser’s basic propositional logic since the latter was developed from the study of formal provability. The workings of residuated basic logic in the study of provability need further exploration.

There are some interesting problems for future work. It is already known that intuitionistic logic is embedded into basic propositional logic by a bounded translation [31]. Using the sequent calculus for intuitionistic logic (cf. [32]) and for residuated basic logic, we could give a purely proof-theoretic proof of this result. Embedding results of this kind could be explored in an extended setting. For example, the embedding of propositional logics into modal logics could be explored by proof-theoretic methods. We can also consider extending the approach given in this paper to more extensions of basic propositional logic. The general question is to determine subintuitionistic propositional logics, which can be formalized as analytic Gentzen-style sequent calculi. Using such sequent calculi, we may obtain the logical properties of these logics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and M.M.; investigation, Z.L. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author of this work was supported by CENTRAL UNIVERSITY BASIC RESEARCH PROJECT (Xiamen University) grant number 2072021107, while the second author was funded by CHINA FUNDING OF SOCIAL SCIENCES grant number 18ZDA033.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Celani, S.; Jansana, R. A closer look at some subintuitionistic logics. Notre Dame J. Form. Log. 2003, 42, 225–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restall, G. Subintuitionistic logics. Notre Dame J. Form. Log. 1994, 35, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, A. A propositional logic with explicit fixed points. Stud. Log. 1981, 40, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagrov, A.; Zakharyaschev, M. Modal Logic; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Corsi, G. Weak logics with strict implication. Zeitschr. F. Math. Logik Grundlagen D. Math. 1987, 33, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Wolter, F.; Zakharyaschev, M. Speaking about transitive frames in propositional languages. J. Log. Lang. Inf. 1998, 7, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruitenburg, W. Constructive logics and the paradoxes. Rev. Mod. Log. 1991, 1, 271–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gentzen, G. Die widerspruchsfreiheit der reinen zahlentheorie. Math. Ann. 1936, 112, 493–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardeshir, M.; Ruitenburg, W. Basic propositional calculus I. Math. Log. Q. 1998, 44, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardeshir, M.; Ruitenburg, W. Basic propositional calculus II. Interpolation. Arch. Math. Log. 2001, 40, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardeshir, M. Aspects of Basic Logic. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Mathematics, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Celani, S.; Jansana, R. Bounded distributive lattices with strict implication. Math. Log. Q. 2005, 51, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Ono, H. Hilbert Style Proof System for BPL; Technical Report IS-RR-97-0040F 1(8); School of Information Science, Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology: Ishikawa, Japan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Aghaei, M.; Ardeshir, M. Gentzen-style axiomatizations for some conservative extensions of basic propositional logic. Stud. Log. 2001, 68, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, K. Proof Theoretical Investigations for Visser’s Logics, Classical Logic and the First-Order Arithmetic. Ph.D. Thesis, Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Ishikawa, Japan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, K.; Kashima, R.; Kikuchi, K. Sequent calculi for Visser’s propositional logics. Notre Dame J. Form. Log. 2001, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Sasaki, K. A cut-free Gentzen formulation of basic propositional calculus. J. Log. Lang. Inf. 2003, 12, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buszkowski, W. Lambek calculus and substructural logics. Linguist. Anal. 2010, 36, 15–48. [Google Scholar]

- Galatos, N.; Jipsen, P.; Kowalski, T.; Ono, H. Residuated Lattices: An Algebraic Glimpse at Substructural Logics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, H. Substructural logics and residuated lattices–an introduction. In Trends in Logic: 50 Years of Studia Logica; Hendricks, V.F., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 177–212. [Google Scholar]

- Restall, G. Relevant and substructural logics. In Logic and the Modalities in the Twentieth Century; Gabbay, D., Woods, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 7, pp. 289–398. [Google Scholar]

- Buszkowski, W.; Farulewski, M. Nonassociative Lambek calculus with additives and context-free languages. In Languages: From Formal to Natural, LNCS 5533; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lambek, J. On the calculus of syntactic types. Struct. Lang. Its Math. Asp. 1961, 12, 166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Galatos, N.; Ono, H. Cut elimination and strong separation for substructural logics: An algebraic approach. Ann. Pure Appl. Log. 2010, 161, 1097–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambek, J. The mathematics of sentence structure. Am. Math. Mon. 1958, 65, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniková, Z.; Horčík, R. The finite embeddability property for residuated groupoids. Algebra Univ. 2014, 72, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restall, G. On Logics without Contraction. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Philosophy, University of Queensland, Woolloongabba, Australia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morsi, N.N. A small set of axioms for residuated logic. Inf. Sci. 2005, 175, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hájek, P. Metamathematics of Fuzzy Logic; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Esteva, F.; Godo, L.; Hájeck, P.; Navara, M. Residuated fuzzy logics with an involutive negation. Arch. Math. Log. 2000, 39, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, M.; Ardeshir, M. A bounded translation of intuitionistic propositional logic into basic propositional logic. Math. Log. Q. 2000, 46, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyckhoff, R. Contraction-free sequent calculi for intuitionistic logic. J. Symb. Log. 1992, 57, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).