Abstract

In this work, a Lotka–Volterra type predator–prey system with time delay and stage structure for the predators is proposed and analyzed. By using the permanence theory for infinite dimensional system, we get that the system is permanent if some conditions are satisfied. The local and global stability of the positive equilibrium is presented. The existence of Hopf bifurcation around the positive equilibrium is observed. Further, by using the normal form theory and center manifold approach, we derive the explicit formulas determining the stability of bifurcating periodic solutions and the direction of Hopf bifurcation. Numerical simulations are carried out by Matlab software to explain the theoretical results. We find that combined time delay and stage structure can affect the dynamical behavior of the system.

MSC:

92B05; 34K18

1. Introduction

Differential equations are a powerful tool for characterizing natural phenomena [1,2]. The predator–prey model is a very classic model, which plays a key role in population ecology. Many predator–prey models have been investigated by some researchers [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. From [10], we know that if the following classical autonomous Lotka–Volterra type predator prey model,

exists in a positive equilibrium , it must be globally asymptotically stable. Time lag is pervasive in nature. The stability issues for the Lotka-Volterra system with different types of time delays have been extensively studied. In [11], by using Lyapunov functional, He examined the global attraction for a kind of delayed n-species Lotka–Volterra-type system. In [12], Gopalsamy et al. examined the global stability of a delay nonautonomous n-species competition system. In [13], He investigated the global asymptotic stability of a nonautonomous Lotka–Volterra system with “pure-delay type”. In [14], Wang et al. proved that delays are harmless for the two-dimensional delayed Lotka–Volterra system. As a special case of Lotka–Volterra-type systems with delays, Chen et al. proposed a model of two species’ growth delays as a reasonable generalization of the Lotka–Volterra model, which takes the form [10]:

System (2) is one of the simplest predator–prey models with a delay. Its stability and Hopf bifurcations, both local and global, have been widely investigated. For example, Wang et al. [14] found that system (2) was uniformly persistent irrespective of the size of the delays. He [11] showed that the positive equilibrium is locally and globally asymptotically stable.

In the real world, however, many consumer species may go though multiple life phases as they progress from birth to death. In [15,16], the authors studied the delayed stage structure models. In those models, a constant time lag represented the time from birth to maturity. References [17,18] have examined the stage structure of species when the transformation rate of the mature population is proportional to the existing immature population. Motivated by the works of Chen [10], He et al. [11,12,13], Cui et al. [15] and Song et al. [16], we built a predator–prey model based on system (2), which includes a time delay due to negative feedback of prey and the stage structure for the predators. This paper’s purpose is to explore the combined effects of both delay and stage structure on the predator–prey system’s dynamical behavior.

2. The Model

We consider a delayed predator–prey system with a stage structure among predator populations of the following form:

where expresses prey density at time t, and and represent densities of the mature and the immature predator species at time t. In model (3), and represent the capturing rates of the predators; k is the intrinsic rate of increase for the prey; r represents the mature predator’s death rate; represents the conversion rate; is the immature predator’s death rate; c denotes the birth rate of the immature predators; is a constant delay. All the parameters (i.e., k, , r, , , c, , and ) are positive constants.

The initial conditions for system (3) have the following form:

We suppose that is the solution of system (3) with the initial conditions (4). Obviously, under the initial conditions given in (4), the solution of system (3) exists in the interval . Further, it remains positive for all . In fact, from the 1st equation of (3), we obtain

for . Set , we can rewrite the last two equations of (3) as

Obviously, there is a unique solution of system (3) in a maximal interval [19]. We can prove that the interval is . Since (5) is a quasimonotone system, is a subsolution and with and is a supersolution [19]. This shows that and are bounded in and hence exist for all . Suppose . We can obtain and . This shows that is a solution of (5) at and hence it is zero in . This is a contradiction. Hence, , for . Thereby, for .

If the conditions

and

hold, all the equilibria are nonnegative.

3. Permanence of System (3)

We first introduce the definition of permanence.

Definition 1

Proof.

Suppose is a positive solution of system (3) with initial condition (4). According to the first equation of system (3), it follows from the positivity of the solution that

The solution of the auxiliary equation

has the following properties: there exist and such that for . Hence, by comparing the theorems for ordinary differential equations, we have for .

Denote . Then,

We define

Along the last two equations of system (3), we calculate the upper-right derivative of :

Then, there exist two positive constants , , such that

Denote . Then, for .

Next, we discuss the permanence of system (3).

To prove that system (3) is persistent, we will use Theorem 4.1 in [20]. □

Proof.

We begin by showing that sets , , and repel the positive solution of system (3) uniformly. Let us define

This choice meets the conditions in Theorem 4.1 in [20]. It suffices to show that, for any solution of system (3) initiating from , there exists an such that . To this end, we shall verify that all the conditions of Theorem 4.1 in [20] are satisfied. It is easy to see that and are positively invariant. Obviously, conditions and of Theorem 4.1 in [20] are satisfied. In the following, we shall only need to validate conditions and .

There are three constant solutions, , , , in .

In the set or , system (3) becomes

Clearly, , . Hence, for any solution of system (3) initiating from , we obtain as .

In the set , system (3) becomes

Obviously, is globally asymptotically stable. Therefore, any solution of system (3) initiating from is such that as .

In the set , system (3) becomes

Clearly, is globally asymptotically stable. Hence, for any solution of system (3) which initiates from , we have as .

Obviously, are isolated invariant, and is isolated and is an acyclic covering.

It is obvious that . Next, we will show that , .

Assume . Then, in system (3) there exists a positive solution such that as . Hence, we have , that is, for , there exists such that . From system (3), for ,

From (10), we can find that This is a contradiction. Therefore, we have .

Assume . Then, there is a positive solution of (3) that as . Hence, , as . From system (3), for , we have

From (6), we find that as . This is a contradiction. Therefore, we have .

At this time, we can conclude that repels the positive solutions of system (3) which initiates from uniformly.

Thus, there exists an such that

From the 3rd equation of system (3), we obtain

Then as . Denote , then . □

4. Stability of Equilibria

In this section, we will discuss the sufficient conditions for the stability of all the equilibrium points for system (3).

Firstly, we analyze the local stability of the equilibria , , .

The characteristic equation of equilibrium is

Obviously, the above equation always has a positive eigenvalue . Hence, is unstable.

The characteristic equation of equilibrium is

Let

The characteristic equation of equilibrium is

Denote

Then, , , so (13) has a positive root. Then the equilibrium is unstable.

In the following, we shall discuss the local and global properties of positive equilibrium .

Theorem 3.

Proof.

Linearizing system (3) at the equilibrium leads to

We obtain the characteristic equation of the form

where

When , we can easily check that all the characteristic roots have negative real parts. We will show that all the characteristic roots have negative real parts for all , which implies that is locally asymptotically stable for (3). Obviously, the characteristic Equation (15) has no positive real parts roots. Now, we suppose that there exists a characteristic root of (15) on the imaginary axis of the complex plane for some . Let be such a characteristic root. It is straightforward to see that . Substituting into (15) and separating the real and imaginary parts, we obtain

and

Furthermore,

Squaring and adding the two equations yields

Let and

Then, must have a positive zero because (17) and . What is more, the coefficients of , and in (18) need to be positive. In fact, the coefficients of and are expressed in the following ways:

Furthermore,

Hence, . Therefore, has no positive roots, which is a contradiction. We complete the proof. □

Theorem 4.

Proof.

Let be any solution of system (3) satisfying initial condition (4). Define

where , , are suitable positive constants to be determined in the subsequent steps. It is easy to see that V is a positive definite function in the region except at where it vanishes. Further,

Calculating the upper right derivative of V along the solutions of system (3), we have:

Let . Then,

Let . If (19) holds, then

Therefore, by using a Lyapunov–Lasalle type theorem [21], we have , , as . □

5. Existence of Hopf Bifurcation

In this section, we shall find the conditions under which a Hopf bifurcation may occur around the positive equilibrium point when delay passes through some critical values.

From (18) we can see that if and , then , and . Hence, Equation (15) has a unique positive root. Then, we have the following lemma.

Lemma 1.

Let us suppose when . From (16) we have

Theorem 5.

Proof.

Let be a root of Equation (15). Substituting in (15) and separating real and imaginary parts, we get the transcendental equations

and

Obviously, is stable when . Hence, remains stable for ( is the smallest value for which where is a solution to (15) with real part zero). We now have to show that when .

Hence,

Since , then at , , , the transversality condition holds. Hence, Hopf bifurcation occurs at , . □

6. Direction and Stability of the Hopf Bifurcation

In this section, we shall discuss the direction and stability of the Hopf bifurcation via the method introduced in [22].

Let , , , , (i = 1, 2, 3), . System (3) is transformed into functional differential equation (FDE) in given by

where and

By the Riesz representation theorem, there exists a matrix function of bounded variation for , such that

for .

In practice, one can choose:

where denotes the Dirac delta function. For , we define

and

Then, system (24) is equivalent to

where , .

For , we define the adjoint operator of A as

and a bilinear inner product given by

where . Clearly, and are a pair of adjoint operators. From the discussions in Section 5, we know that are eigenvalues of . Thus, they are also eigenvalues of . In the next, we shall calculate the eigenvector of and eigenvector of corresponding to and , respectively.

Let be the eigenvector of corresponding to , then . From the definition of and (25), (27) and (28), we can obtain that

From above, it is easy to obtain , where , . Similarly, assuming that is the eigenvector of corresponding to , we can get , by the definition of and (25)–(27). In order to ensure , we need to determine the value of D. From (31), we have

Thus, we can select D as

Using the same notations as in [22], we first calculate the coordinates to describe the center manifold at . Let be the solution of (30) when . Define

On the center manifold we have

where

z and are local coordinates for center manifold in the direction of and . Note that W is real if is real. We only consider real solutions. For solution of (30), since , we have

We rewrite this equation as

where

It follows together with (26) that:

Comparing the coefficients with (34), we have:

Substituting the corresponding series into (38) and comparing the coefficients, we obtain

From (38), we know that for ,

Notice that , hence

where is a constant vector. Similarly, from (40) and (43), we obtain

where is also a constant vector.

In what follows, we shall seek appropriate and . From the definition of A and (40), we obtain

and

where . By (38), we have

and

It follows that:

where

Thus, we can determine and from (44) and (45). Furthermore, in (37) can be expressed by the parameters and delay. Then, we can compute the following values:

In conclusion, we have the results as following.

Theorem 6.

(1) If (), Hopf bifurcation is subcritical (supercritical); (2) If (), the bifurcating periodic solution is stable (unstable); (3) If (), the period increases (decreases).

7. Numerical Simulations

In this section, we provide numerical examples of Theorems 5 and 6 by using Matlab.

Let , , , , , , . Hence, , , , , , , ,

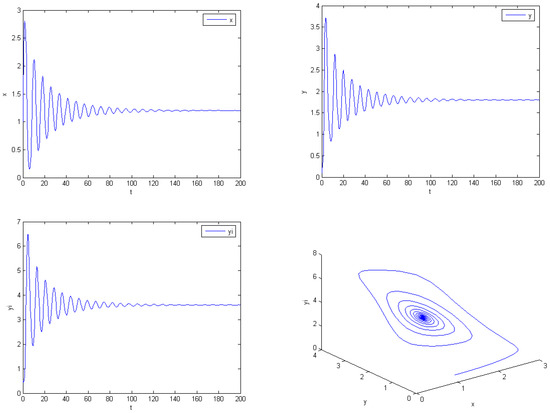

(i) . In this case, the numerical simulation (see Figure 1) shows that the predator and prey populations spiral toward the equilibrium ;

Figure 1.

, , , , , , , . The solution tends to the positive equilibrium. The initial value is constant function for .

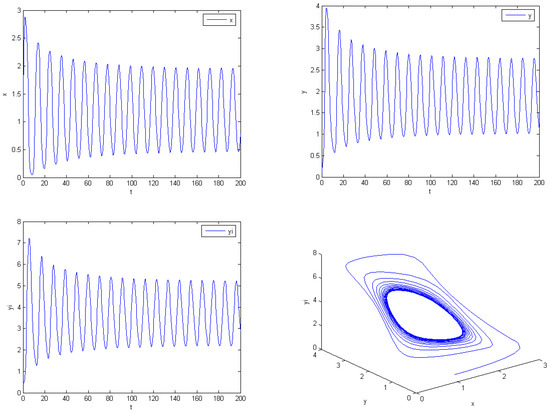

(ii) By calculation, we obtain By Theorem 5.1, a Hopf bifurcation occurs when . Select . From Figure 2, we can find that both the predator and prey populations reach periodic oscillations around the equilibrium in finite time;

Figure 2.

Trajectory of the system with same parameters as Figure 1. except that . The solution tends to the periodic solution. The initial value is constant function for .

8. Discussion

In this paper, a new dynamics for a predator–prey model with staged structure and time delay has been analyzed. We discuss the influence of the parameter on the dynamics of the system (3). The system (3) is permanent under some conditions. The local and global stability of the positive equilibrium is presented. By choosing as a bifurcation parameter, we prove that the delay loss of stability phenomenon appears under the conditions and . That is to say, there is a critical value of such that system (3) is stable in the range at positive equilibrium (see Figure 1); when , a Hopf bifurcation occurs around ; when , the system is unstable (see Figure 2) and there are always Hopf bifurcations near the positive equilibrium when takes other critical values. We derive explicit formulae for determining the properties of Hopf bifurcation at the critical value of via the ideas of Hassard et al. If we do not consider the staged structure of the predator, system (2) has no periodic solutions, which shows that the staged structure of the predator can severely affect the dynamical behavior of the system. However, for system (3), there is no chaotic behavior of the system (3) by numerical simulations.

Funding

This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Henan (222300420521), Program for Innovative Research Team (in Science and Technology) in University of Henan Province (21IRTSTHN014) and Nanhu Scholars Program for Young Scholars of XYNU.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous referees for their careful reading of the original manuscript and their many valuable comments and suggestions that greatly improve the presentation of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Conejero, J.A.; Murillo-Arcila, M.; Seoane, J.M.; Seoane-Sepúlveda, J.B. When Does Chaos Appear While Driving? Learning Dynamical Systems via Car-Following Models. Math. Mag. 2022, 95, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Shi, X.; Wei, M. Dynamical behavior and optimal control of a stochastic mathe-matical model for cholera. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 156, 111854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolabi, K.M. Computational dynamics of predator–prey model with the power-law k-ernel. Results Phys. 2021, 21, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Alamri, S.; Rajhi, A.A.; Anqi, A.E.; Riaz, M.B.; Elagan, S.K.; Jawa, T.M. A novel piece-wise approach to modeling interactions in a food web model Author links open overlay panel. Results Phys. 2021, 31, 104951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K.; Sahoo, D.; Samanta, G.P. Impact of fear in a delay-induced predator–prey system with intraspecific competition within predator species. Math. Comput. Simul. 2022, 191, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, D.; Hayat, T. Dynamics of stochastic predator-prey models with distributed delay and stage structure for prey. Int. J. Biomath. 2021, 14, 2150020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsakaji, H.J.; Kundu, S.; Rihan, F.A. Delay differential model of one-predator two-prey system with Monod-Haldane and holling type II functional responses. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 397, 125919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, F.; Semmar, B.; Al Nasr, K. Dynamics and simulations of discretized Caputo-conformable fractional-order Lotka-Volterra models. Nonlinear Eng. 2022, 11, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, F.; Semmar, B.; Al Nasr, K. Incommensurate conformable-type three-dimensional Lotka–Volterra model: Discretization, stability, and bifurcation. Arab. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 29, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.S.; Song, X.Y.; Lu, Z.Y. Mathematica Models and Methods in Ecology; Sichuan Science and Technology: Chengdu, China, 2003. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, X.Z. The Lyapunov functionals for delay Lotka Volterra type models. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1998, 58, 1222–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalsamy, K.; He, X.Z. Global stability in n-species competition modelled by “pure-delay type” systems II: Nonautonomous case. Can. Appl. Math. Q. 1998, 6, 17–43. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.Z. Global stability in nonautonomous Lotka–Volterra systems of “pure-delay type”. Differ. Integral Equations 1998, 11, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.D.; Ma, Z.E. Harmless delays for uniform peristence. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1991, 158, 256–268. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.A.; Chen, L.S.; Wang, W.D. The effect of dispersal on population growth with stage- structure. Comput. Appl. Math. 2000, 39, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Song, X.Y.; Cui, J.A. The Stage-structured predator–prey System with Delay and Harvesting. Appl. Anal. 2002, 81, 1127–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, W.G.; Freedman, H. A time-delay model of single-species growth with stage structure. Math. Biosci. 1990, 101, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Fan, J.; Gard, T.C. The effects of state-dependent time delay on a stage-structured population growth model. Nonlinear Anal. Theory Methods Appl. 1992, 19, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, W. Ordinary Differential Equations. Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: Now York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, J.K.; Waltman, P. Persistence in inffnite-dimensional systems. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1989, 20, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y. Delay Differential Equations with Applications in Population Dynamics; Academic Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hassard, B.D.; Kazarini, N.D.; Wan, Y.H. Theory and Application of Hopf Bifurcation; London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, 41; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).