Kaolinite Illitization Under Hydrothermal Conditions: Experimental Insight into Transformation Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identify the conditions under which kaolinite transforms into illite.

- Examine morphological and textural changes in kaolinite-derived illite compared to natural illite.

- Assess the effect of varying fluid compositions (synthetic KCl–MgCl2 vs. natural Red Sea water) on illitization.

2. Geological Background of the Starting Material

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Hydrothermal Reactor Experiments

3.2. Thin-Section Petrography

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

Clay Fraction XRD Sample Preparation and Procedure

3.4. Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS)

Ion Chromatography

4. Results

4.1. Mineralogy and Texture of the Starting Material

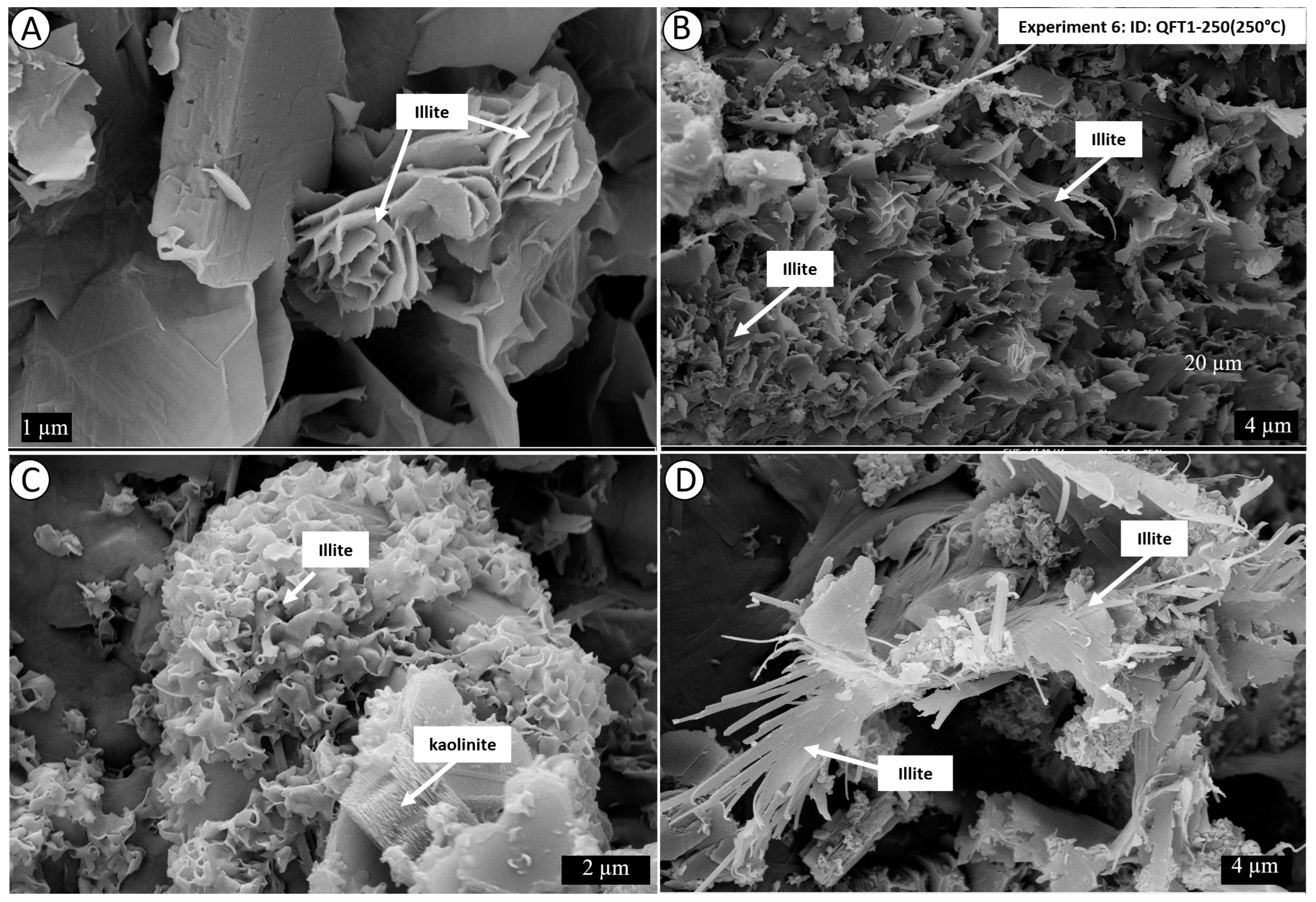

4.2. Post-Experiment Composition

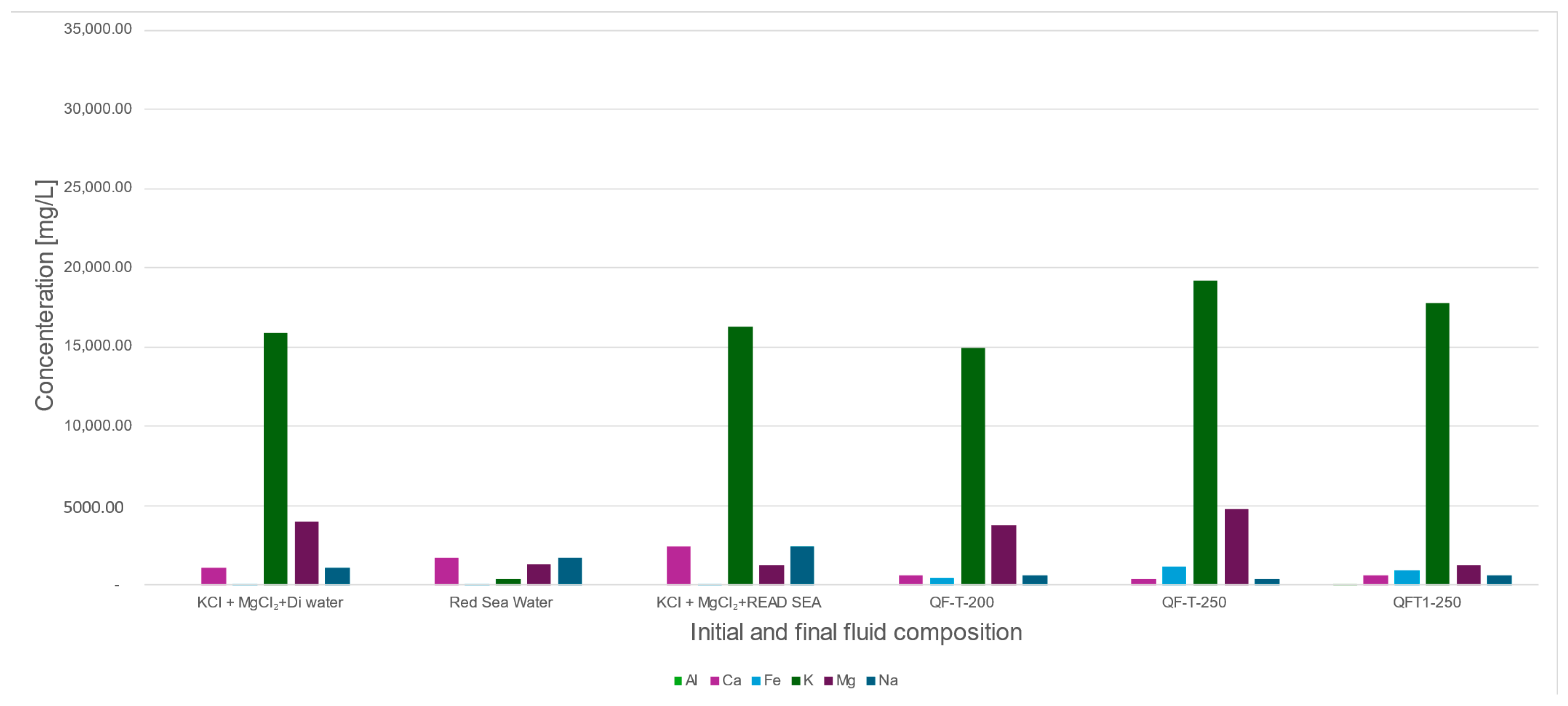

4.3. Chemical Changes (ICP-MS and Ion Chromatography Analysis)

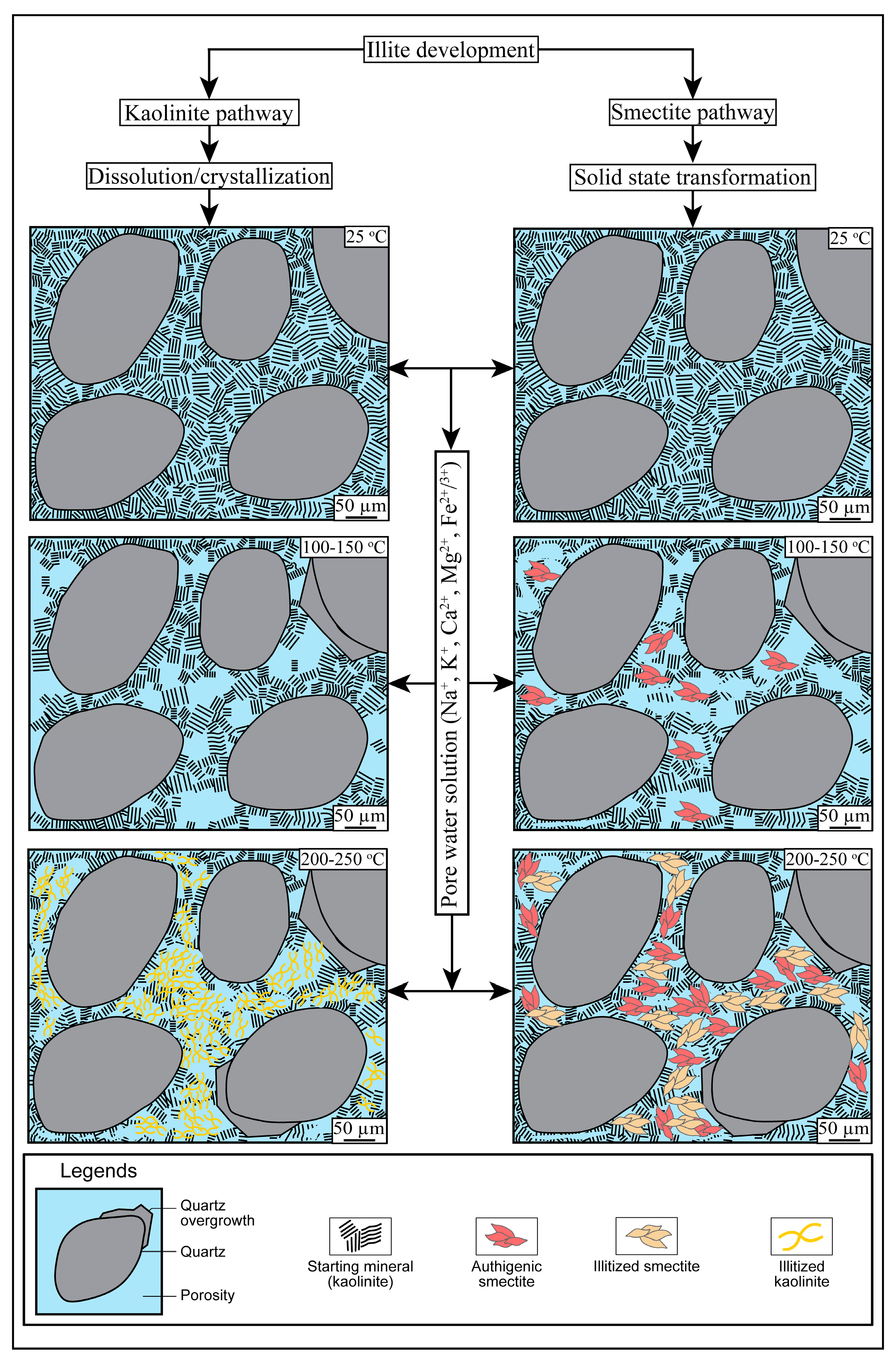

5. Discussion

5.1. Mechanism of Conversion of Kaolinite into Illite

5.1.1. Smectite Pathway

5.1.2. Kaolinite Pathway

5.2. Role of Fluid Composition and Temperature

5.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akinlotan, O.O.; Moghalu, O.A.; Hatter, S.J.; Okunuwadje, S.; Anquilano, L.; Onwukwe, U.; Haghani, S.; Anyiam, O.A.; Jolly, B.A. Clay Mineral Formation and Transformation in Non-Marine Environments and Implications for Early Cretaceous Palaeoclimatic Evolution: The Weald Basin, Southeast England. J. Palaeogeogr. 2022, 11, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, D.; Hower, J. The Hydrothermal Transformation of Sodium and Potassium Smectite into Mixed-Layer Clay. Clays Clay Min. 1977, 25, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.D.; Pittman, E.D. Authigenic Clays in Sandstones; Recognition and Influence on Reservoir Properties and Paleoenvironmental Analysis. J. Sediment. Res. 1977, 47, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.H.; Burley, S.D. Sandstone Diagenesis: The Evolution of Sand to Stone. In Sandstone Diagenesis; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 1–44. ISBN 9781444304459. [Google Scholar]

- Ajdukiewicz, J.M.; Lander, R.H. Sandstone Reservoir Quality Prediction: The State of the Art. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 2010, 94, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ramadan, K. Illitization of Smectite in Sandstones: The Permian Unayzah Reservoir, Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2014, 39, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, A.M.; Algheryafi, H.; Bello, A.M.; Amao, A.O.; Al-Otaibi, B.; Al-Ramadan, K. Depositional and Diagenetic Controls on the Reservoir Quality of Marginal Marine Sandstones: An Example from the Early Devonian Subbat Member, Jauf Formation, Northwest Saudi Arabia. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 170, 107147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.M.; Salisu, A.M.; Alqubalee, A.; Amao, A.O.; Al-Hashem, M.; Al-Hussaini, A.; Al-Ramadan, K. Diagenetic Controls on the Quality of Shallow Marine Sandstones: An Example from the Cambro-Ordovician Saq Formation, Central Saudi Arabia. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2024, 215, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.M.; Usman, M.B.; Abubakar, U.; Al-Ramadan, K.; Babalola, L.O.; Amao, A.O.; Sarki Yandoka, B.M.; Kachalla, A.; Kwami, I.A.; Ismail, M.A.; et al. Role of Diagenetic Alterations on Porosity Evolution in the Cretaceous (Albian-Aptian) Bima Sandstone, a Case Study from the Northern Benue Trough, NE Nigeria. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 145, 105851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowey, P.J.; Hodgson, D.M.; Worden, R.H. Pre-Requisites, Processes, and Prediction of Chlorite Grain Coatings in Petroleum Reservoirs: A Review of Subsurface Examples. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2012, 32, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, S.N. Preservation of Anomalously High Porosity in Deeply Buried Sandstones by Grain-Coating Chlorite: Examples from the Norwegian Continental Shelf1. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 1993, 77, 1260–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeshidayatullah, A.; Trower, E.J.; Li, X.; Mukerji, T.; Lehrmann, D.J.; Morsilli, M.; Al-Ramadan, K.; Payne, J.L. Quantitative Evaluation of the Roles of Ocean Chemistry and Climate on Ooid Size across the Phanerozoic: Global versus Local Controls. Sedimentology 2022, 69, 2486–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, A.M.; Alqubalee, A.; Bello, A.M.; Al-Hussaini, A.; Adebayo, A.R.; Amao, A.O.; Al-Ramadan, K. Impact of Kaolinite and Iron Oxide Cements on Resistivity and Quality of Low Resistivity Pay Sandstones. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 158, 106568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walderhaug, O. Kinetic Modeling of Quartz Cementation and Porosity Loss in Deeply Buried Sandstone Reservoirs1. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 1996, 80, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwiller, D.N. Illite/Smectite Formation and Potassium Mass Transfer during Burial Diagenesis of Mudrocks; a Study from the Texas Gulf Coast Paleocene-Eocene. J. Sediment. Res. 1993, 63, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.; Morad, S. Clay Minerals in Sandstones: Controls on Formation, Distribution and Evolution. In Clay Mineral Cements in Sandstones; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 34, pp. 1–41. ISBN 9781444304336. [Google Scholar]

- Lander, R.H.; Walderhaug, O. Predicting Porosity through Simulating Sandstone Compaction and Quartz Cementation1. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 1999, 83, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, E.F. Quartz Cement in Sandstones: A Review. Earth Sci. Rev. 1989, 26, 69–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.M.; Sanchez, A.C.; Boisvert, L.; Payne, C.B.; Ho, T.A.; Wang, Y. Understanding Smectite to Illite Transformation at Elevated. Chem. Geol. 2023, 615, 121214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, P.H.; Wilson, J.; McHardy, W.J.; Tait, J.M. The Conversion of Smectite to Illite during Diagenesis: Evidence from Some Illitic Clays from Bentonites and Sandstones. Miner. Mag. 1985, 49, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pytte, A.M.; Reynolds, R.C. The Thermal Transformation of Smectite to Illite. In Thermal History of Sedimentary Basins: Methods and Case Histories; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; pp. 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ajdukiewicz, J.M.; Larese, R.E. How Clay Grain Coats Inhibit Quartz Cement and Preserve Porosity in Deeply Buried Sandstones: Observations and Experiments. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 2012, 96, 2091–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, L.J.; Worden, R.H.; Griffiths, J.; Utley, J.E.P. Clay-Coated Sand Grains in Petroleum Reservoirs: Understanding Theirdistribution via a Modern Analogue. J. Sediment. Res. 2017, 87, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millot, G. Geology of Clays: Weathering Sedimentology Geochemistry; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISSN 3662416093. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwadebi, A.G.; Taylor, K.G.; Dowey, P.J. Diagenetic Controls on the Reservoir Quality of the Tight Gas Collyhurst Sandstone Formation, Lower Permian, East Irish Sea Basin, United Kingdom. Sediment. Geol. 2018, 371, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.M.; Usman, M.B.; Ismail, M.A.; Mukkafa, S.; Abubakar, U.; Kwami, I.A.; Al-Ramadan, K.; Amao, A.O.; Al-Hashem, M.; Salisu, A.M.; et al. Linking Diagenesis and Reservoir Quality to Depositional Facies in Marginal to Shallow Marine Sequence: An Example from the Campano-Maastrichtian Gombe Sandstone, Northern Benue Trough, NE Nigeria. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 155, 106386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.M.; Usman, M.B.; Amao, A.O.; Al-Ramadan, K.; Al-Hashem, M.; Kachalla, A.; Abubakar, U.; Salisu, A.M.; Mukkafa, S.; Kwami, I.A.; et al. Diagenesis and Reservoir Quality Evolution of Estuarine Sandstones: Insights from the Cenomanian-Turonian Yolde Formation, Northern Benue Trough, NE Nigeria. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 169, 107073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walderhaug, O.; Porten, K.W. How Do Grain Coats Prevent Formation of Quartz Overgrowths? J. Sediment. Res. 2022, 92, 988–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanson, B.; Sakharov, B.; Claret, F.; Drits, V. Diagenetic Smectite-to-Illite Transition in Clay-Rich Sediments: A Reappraisal of X-Ray Diffraction Results Using the Multi-Specimen Method. Am. J. Sci. 2009, 309, 476–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.M.; Charlaftis, D.; Jones, S.J.; Gluyas, J.; Acikalin, S.; Cartigny, M.; Al-Ramadan, K. Experimental Diagenesis Using Present-Day Submarine Turbidite Sands. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Ali, M.; Littke, R. Paleozoic Petroleum Systems of Saudi Arabia: A Basin Modeling Approach. GeoArabia 2005, 10, 131–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, S.; McGowen, J.H. Influence of Depositional Environment on Reservoir Quality Prediction. Reserv. Qual. Assess. Predict. Clastic Rocks 1994, 30, 952690. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, A.M.; Al-Ramadan, K.; Koeshidayatullah, A.I.; Amao, A.O.; Herlambang, A.; Al-Ghamdi, F.; Malik, M.H. Impact of Magmatic Intrusion on Diagenesis of Shallow Marine Sandstones: An Example from Qasim Formation, Northwest Saudi Arabia. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1105547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.M.; Salisu, A.M.; Amao, A.O.; Mustapha, U.; Al Ramadan, K. Experimental Development of Chlorite: Insights from a Kaolinite Precursor. J. Sediment. Res. 2025, 95, 462–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, A.M.; Bello, A.M.; Amao, A.O.; Lander, R.H.; Al-Ramadan, K. Experimental Study of Smectite Authigenesis and Its Subsequent Illitization: Insights From Modern Estuary Sediments. J. Sediment. Res. 2025, 95, 562–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, A.M.; Bello, A.M.; Amao, A.O.; Al-Ramadan, K. The Role of Fluid Chemistry in the Diagenetic Transformation of Detrital Clay Minerals: Experimental Insights from Modern Estuarine Sediments. Minerals 2025, 15, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.M.; Amao, A.O.; Salisu, A.M.; Al-Ramadan, K. Clay-Driven Dolomitization at Moderate to High Temperatures: Evidence from Hydrothermal Experiments. Geology 2025, 53, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amao, A.; Al-Ramadan, K.; Koeshidayatullah, A. Automated Mineralogical Methodology to Study Carbonate Grain Microstructure: An Example from Oncoids. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqubalee, A.; Muharrag, J.; Salisu, A.M.; Eltom, H. The Negative Impact of Ophiomorpha on Reservoir Quality of Channelized Deposits in Mixed Carbonate Siliciclastic Setting: The Case Study of the Dam Formation, Saudi Arabia. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 140, 105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, B.G.; Hellevang, H.; Aagaard, P.; Jahren, J. Experimental Nucleation and Growth of Smectite and Chlorite Coatings on Clean Feldspar and Quartz Grain Surfaces. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2015, 68, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, J.M.; Worden, R.H.; Ruffell, A.H. Smectite in Sandstones: A Review of the Controls on Occurrence and Behaviour during Diagenesis. Clay Miner. Cem. Sandstones 1999, 34, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.N.; Franks, S.G.; Hussain, A.; Amao, A.O.; Bello, A.M.; Al-Ramadan, K. Depositional and Diagenetic Controls on the Reservoir Quality of Early Miocene Syn-Rift Deep-Marine Sandstones, NW Saudi Arabia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2024, 259, 105880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment | Sample ID | pH (25 °C) | Total Dissolved Solid (ppm) | Starting Solution (M) | Temperature (°C) | Duration (Hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | QF-T-80 | 6.77 | 79.23 | 0.5 KCl, 0.2 MgCl2. H2O | 80 | 336 |

| 2 | QF-T-150 | 5.99 | 79.47 | 0.5 KCl, 0.2 MgCl2. H2O | 150 | 336 |

| 3 | QF-T-200 | 5.84 | 60.81 | 0.5 KCl, 0.2 MgCl2. H2O | 200 | 336 |

| 4 | QF-T-250 | 5.7 | 60.38 | 0.5 KCl, 0.2 MgCl2. H2O | 250 | 336 |

| 5 | QF-RS-T-250 | 5.6 | 61.46 | Red Sea water (see Table 2 for composition) | 250 | 336 |

| 6 | QFT1-T250 | 3.3 | 108.5 | 0.5 KCl, 0.2 MgCl2 + Red Sea water | 250 | 504 |

| SAMPLE ID Method | Al ICP-MS | Ca Ion-C | Fe ICP-MS | K Ion-C | Mg Ion-C | Na Ion-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCl + MgCl2+Di water | ND | 1104.56 | 7.14 | 15,849.59 | 3979.41 | 1104.56 |

| Red Sea Water | ND | 1671.44 | 6.79 | 392.64 | 1277.04 | 1671.44 |

| KCl + MgCl2+RED SEA | ND | 2389.08 | 7.15 | 16,243.02 | 1266.02 | 2389.08 |

| QF-T-200 | ND | 615.13 | 461.27 | 14,931.69 | 3771.10 | 615.13 |

| QF-T-250 | ND | 373.90 | 1121.53 | 19,173.69 | 4758.35 | 373.90 |

| QFT1-250 | 0.57 | 597.80 | 933.09 | 17,737.03 | 1248.17 | 597.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alfaraj, M.A.; Bello, A.M.; Salisu, A.M.; Al-Ramadan, K. Kaolinite Illitization Under Hydrothermal Conditions: Experimental Insight into Transformation Pathways. Minerals 2026, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010004

Alfaraj MA, Bello AM, Salisu AM, Al-Ramadan K. Kaolinite Illitization Under Hydrothermal Conditions: Experimental Insight into Transformation Pathways. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfaraj, Mashaer A., Abdulwahab Muhammad Bello, Anas Muhammad Salisu, and Khalid Al-Ramadan. 2026. "Kaolinite Illitization Under Hydrothermal Conditions: Experimental Insight into Transformation Pathways" Minerals 16, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010004

APA StyleAlfaraj, M. A., Bello, A. M., Salisu, A. M., & Al-Ramadan, K. (2026). Kaolinite Illitization Under Hydrothermal Conditions: Experimental Insight into Transformation Pathways. Minerals, 16(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010004