Preliminary Study of Geochemical, Mineralogical and Magnetic Susceptibility Properties of Flotation Tailings from the Pb-Zn-Cu-Ag Rudnik Mine, Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

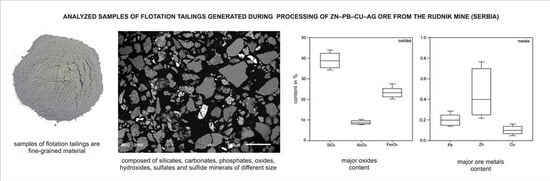

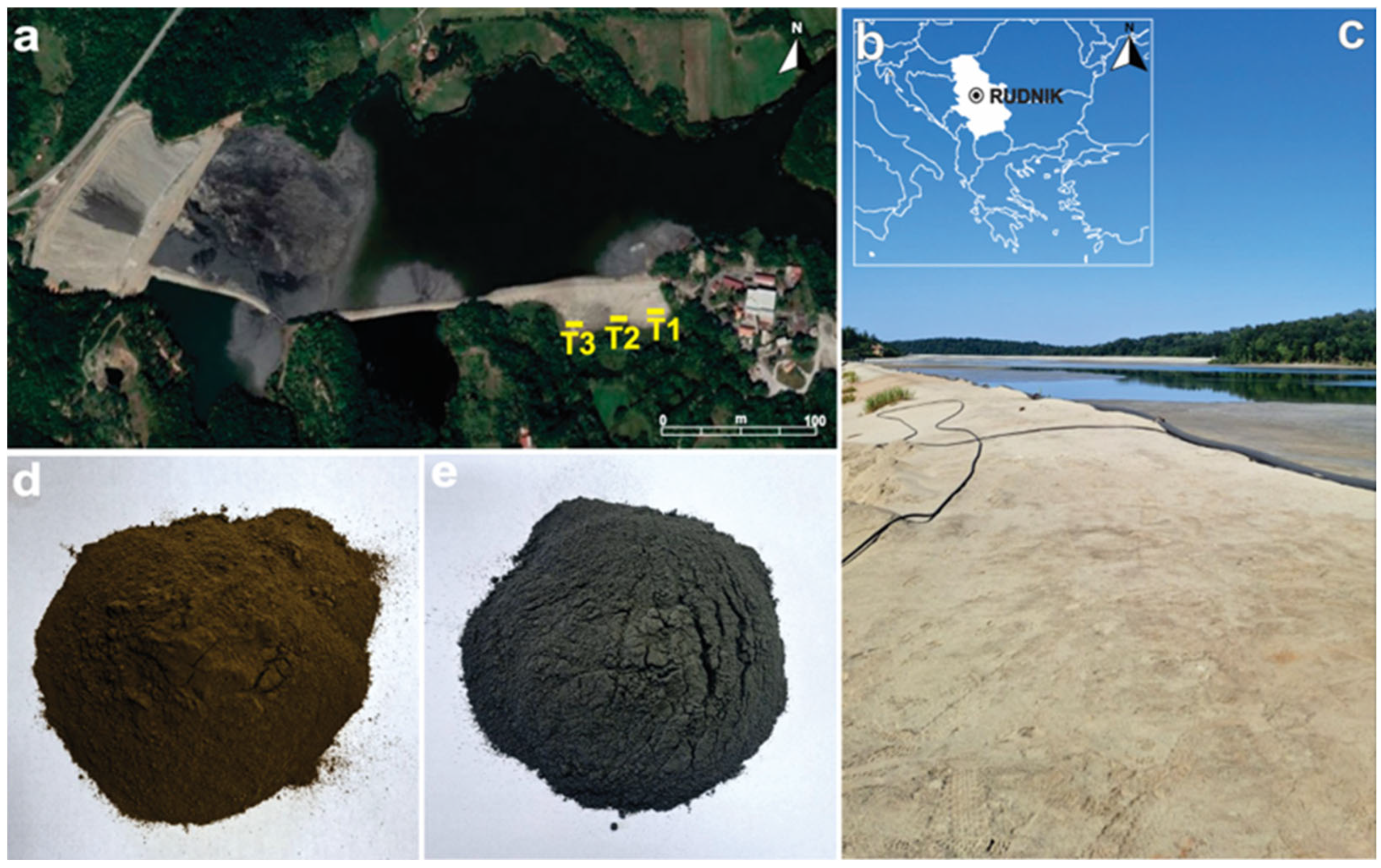

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

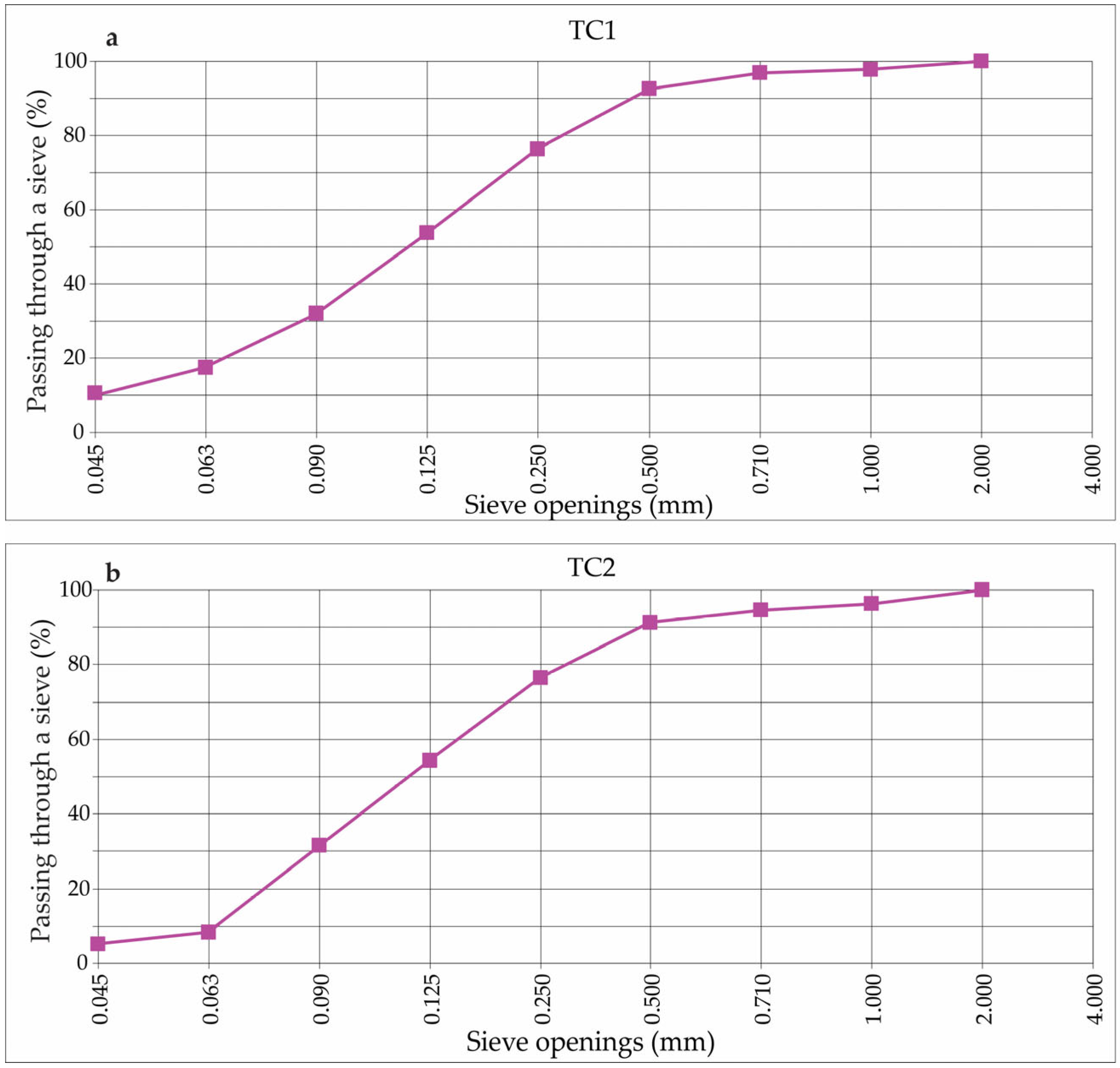

2.2. Granulometrical Analysis

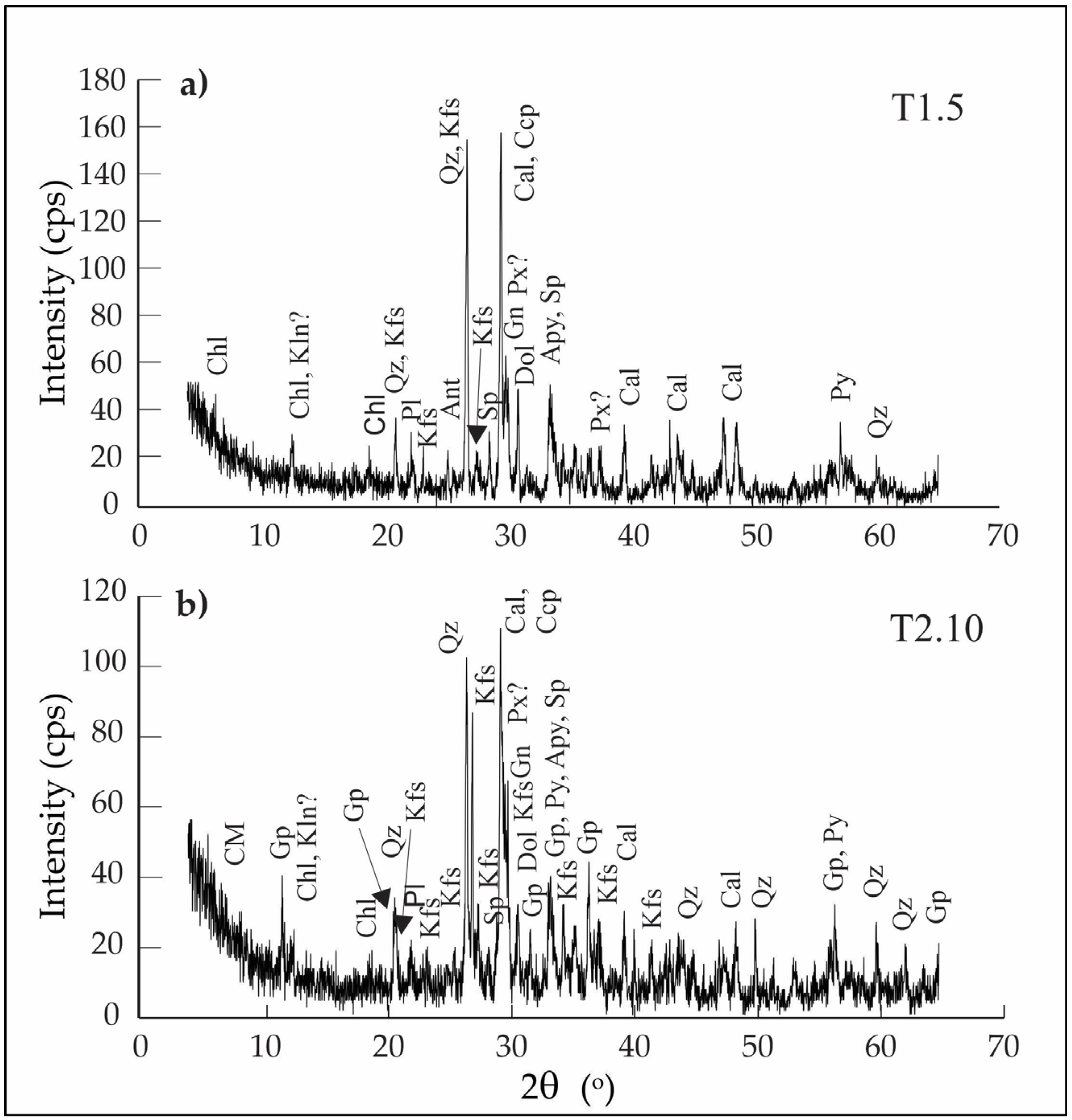

2.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.4. Optical and Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

2.5. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF)

2.6. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.7. Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES)

2.8. Laboratory Measurement of Magnetic Susceptibility (MS)

3. Results

3.1. Grain Size Distribution

3.2. Mineralogy

3.2.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

3.2.2. FTIR Analysis

3.2.3. Optical and Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

3.3. Geochemistry

3.4. Magnetic Susceptibility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Complex mineral associations and microtextural intergrowths of rock-forming minerals with sulfides hinder efficient flotation of the primary ore.

- Flotation tailings are dominated by quartz, calcite, orthoclase and accompanied by Ca-garnets, Ca-pyroxenes and epidote. Economically valuable sulfides—sphalerite, galena, and chalcopyrite—are mostly present in fractions finer than 400 µm (mostly below 100 µm) and occur as dispersed grains within a silicate–carbonate matrix. Post-depositional oxidation is moderately developed; pyrite is often replaced by hematite, galena by cerussite, and chalcopyrite by malachite, while other sulfides remain relatively unaltered.

- High SiO2 and Al2O3 contents confirm the dominance of silicate and aluminosilicate minerals, whereas elevated Fe2O3 and S reflect the presence of iron sulfides. Zn, Pb, and Cu concentrations are below 1%, while minor elements such as Ag and Bi, although present at low levels, may hold future economic potential.

- Mass magnetic susceptibility data support the mineralogical observations: samples with higher Fe2O3 and S show elevated susceptibility, whereas samples with lower Fe2O3 exhibit reduced susceptibility, consistent with XRD and SEM-EDS analyses.

- Given the relatively low metal concentrations and the complex intergranular associations of the minerals, the most realistic immediate valorization pathway is the use of the tailings as low-value construction aggregates. Future research will include various mineral processing techniques for further characterization and evaluation of the tailings. Selective pre-treatment for trace-metal recovery could also be investigated as a secondary option following detailed characterization and a technical–economic assessment.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Mining Waste; European Commission—Environment. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/mining-waste_en#law (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Gavrilovic, D. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia; Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2024; 446p. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, T.M.C.; Bertrandsson Erlandsson, V.; Šajn, R.; Melcher, F. Preliminary chemical and mineralogical characterization of tailings from base metal sulfide deposits in Serbia and North Macedonia. Geol. Croat. 2022, 75, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šajn, R.; Ristović, I.; Čeplak, B. Mining and metallurgical waste as potential secondary sources of metals—A case study for the West Balkan region. Minerals 2022, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djokić, B.V.; Jović, V.; Jovanović, M.; Ćirić, A.; Jovanović, D. Geochemical behaviour of some heavy metals of the Grot flotation tailing, Southeast Serbia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 66, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramović, F.; Cvetkov, V.; Ilić, A.; Životić, D. Korelacija magnetnog susceptibiliteta i sadržaja metala u flotacijskom jalovištu. In Proceedings of the 18. Kongres Geologa Srbije “Geologija Rešava Probleme”, Divčibare, Serbia, 1–4 June 2022; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lazić, P.; Nikšić, Đ.; Miković, B.; Tomanec, R. Copper minerals flotation in flotation plant of the “Rudnik” mine. Podzemni Rad. 2019, 35, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, P.; Nikšić, D.; Tomanec, R.; Vučinić, D.; Cvetičanin, L. Chalcopyrite floatability in flotation plant of the Rudnik mine. J. Min. Sci. 2020, 56, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikšić, D.; Lazić, P.; Kostović, M. Flotability of chalcopyrite from the Rudnik deposit. J. Min. Sci. 2021, 57, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, R.; Umeljić, G. Metallogeny of the Rudnik Mountain, Position in Time and Space; Rudnik doo: Belgrade, Serbia, 2015; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V.; Šarić, K.; Pécskay, Z.; Gerdes, A. The Rudnik Mts. volcano-intrusive complex (central Serbia): An example of how magmatism controls metallogeny. Geol. Croat. 2016, 69, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerler, J.; Von Quadt, A.; Burkhard, R.; Peytcheva, I.; Cvetković, V.; Baker, T. The Karavansalija mineralized center at the Rogozna Mountains in SW Serbia: Magma evolution and time relationship of intrusive events and skarn Au±Cu–Pb–Zn mineralization. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 9, 798701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, S.; Bakker, R.J.; Cvetković, V.; Jelenković, R. Multiphase evolution of fluids in the Rudnik hydrothermal-skarn deposit (Serbia): New constraints from study of quartz-hosted fluid inclusions. Mineral. Petrol. 2024, 118, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, J.; Radosavljević-Mihajlović, A.; Radosavljević, S.; Vuković, N.; Pačevski, A. Mineralogy and genetic characteristics of the Rudnik Pb-Zn/Cu, Ag, Bi, W polymetallic deposit (Central Serbia)—New occurrence of Pb (Ag) Bi sulfosalts. Period. Mineral. 2016, 85, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- OREAS 135. Available online: https://www.oreas.com/crm/oreas-135/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Whitney, D.L.; Evans, B.W. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. Am. Mineral. 2010, 95, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerstenau, D.W.; Phatak, P.B.; Kapur, P.C.; Abouzeid, A.Z. Simulation of the grinding of coarse/fine (heterogeneous) systems in a ball mill. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2011, 99, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, L.; Mainza, A.N.; Becker, M.; Wiese, J.G. Using mineralogical and particle shape analysis to investigate enhanced mineral liberation through phase boundary fracture. Powder Technol. 2016, 301, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, J.N.; Radosavljević, S.A.; Tošović, R.D.; Pačevski, A.M.; Radosavljević-Mihajlović, A.S.; Kašić, V.D.; Vuković, N.S. A review of the Pb-Zn-Cu-Ag-Bi-W polymetallic ore from the Rudnik orefield, Central Serbia. Geol. Anal. Balk. Poluostrva 2018, 79, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Ballester, A.; Gonzalez, F.; Blázquez, M.L. Pyrite behaviour in a tailings pond. Hydrometallurgy 2005, 76, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravković, A.; Cvetković, V.; Pačevski, A.; Rosić, A.; Šarić, K.; Matović, V.; Erić, S. Products of oxidative dissolution on waste rock dumps at the Pb-Zn Rudnik mine in Serbia and their possible effects on the environment. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 181, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, D.J.; Corkhill, C.L. Mineralogy of sulfides. Elements 2017, 13, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.L.; Cook, N.J.; Ciobanu, C.L. Partitioning of trace elements in co-crystallized sphalerite–galena–chalcopyrite hydrothermal ores. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 77, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.L.; Cook, N.J.; Crowe, B.B.; Ciobanu, C.L. Trace elements in hydrothermal chalcopyrite. Mineral. Mag. 2018, 82, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godirilwe, L.L.; Gayratov, B.; Jeon, S.; Shibayama, A. Utilization of pyrite-rich tailings in sulfation roasting for efficient recovery of copper, nickel, and cobalt from smelter slag. In Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on Mechanical, Chemical, and Material Engineering (MCM 2025), Paris, France, 19–21 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, D.J.; Özdemir, Ö. Rock Magnetism: Fundamentals and Frontiers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Trench | Samples ID | Depth (m) | Material Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T1.1 | 0.0–0.5 | Grey material |

| T1.2 | 0.5–1.0 | ||

| T1.3 | 1.0–1.5 | ||

| T1.4 | 1.5–2.0 | ||

| T1.5 | 2.0–2.5 | Brown material | |

| T1.6 | 2.5–3.0 | ||

| T1.7 | 3.0–3.5 | Grey material, interbedded with Brown | |

| T1.8 | 3.5–4.0 | ||

| T2 | T2.9 | 0.0–1.0 | Grey material |

| T2.10 | 1.0–2.0 | ||

| T2.11 | 2.0–3.0 | Brown material | |

| T2.12 | 3.0–4.0 | Grey material | |

| T3 | T3.13 | 0.0–1.0 | Grey material |

| T3.14 | 1.0–2.0 | ||

| T3.15 | 2.0–3.0 | Brown material | |

| T3.16 | 3.0–4.0 | Grey material |

| Sieve, mm | TC1, % | TC2, % |

|---|---|---|

| F9: 1.0–2.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| F8: 0.710–1.0 | 97.6 | 96.2 |

| F7: 0.500–0.710 | 97.0 | 94.5 |

| F6: 0.250–0.500 | 92.7 | 91.1 |

| F5: 0.125–0.250 | 76.4 | 76.3 |

| F4: 0.090–0.125 | 53.8 | 54.3 |

| F3: 0.063–0.090 | 32.0 | 31.6 |

| F2: 0.045–0.063 | 17.3 | 8.1 |

| F1: <0.045 | 10.6 | 5.1 |

| Group | Mineral | Confirmation Method | Relative Abundance in the Samples | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1.1 | T1.2 | T1.3 | T1.4 | T1.5 | T1.6 | T1.7 | T1.8 | T2.9 | T2.10 | T2.11 | T2.12 | T3.13 | T3.14 | T3.15 | T3.16 | |||||||||||

| Silicates, phosphates, carbonates, sulfates | Quartz | XRD, Optical, SEM-EDS, FTIR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Calcite | XRD, Optical, SEM-EDS, FTIR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Epidote | SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ca-garnet | SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orthoclase (K-feldspar) | XRD, SEM-EDS, FTIR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ca-clinopyroxene | SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Apatite | SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zircon | SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gypsum | XRD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chlorite | XRD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Plagioclase | XRD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sulfides and native elements | Pyrite | XRD, Optical, SEM-EDS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arsenopyrite | XRD, Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pyrrhotite | XRD, Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sphalerite | XRD, Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chalcopyrite | XRD, Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Galena | XRD, Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native bismuth | Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native silver | Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native copper | Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pentlandite | Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxides and hydroxides (weathering minerals) | Hematite | Optical, SEM-EDS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bismite | Optical, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cerussite | SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malachite | SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anatase | XRD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Goethite | XRD, SEM-EDS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| major | moderate | minor | trace | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| T1.1 | T1.2 | T1.3 | T1.4 | T1.5 | T1.6 | T1.7 | T1.8 | T2.9 | T2.10 | T2.11 | T2.12 | T3.13 | T3.14 | T3.15 | T3.16 | AV | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 (%) | 44.30 | 35.74 | 35.10 | 35.10 | 34.45 | 40.23 | 43.01 | 37.24 | 43.87 | 38.31 | 33.81 | 37.66 | 41.73 | 41.30 | 43.23 | 38.73 | 38.99 | 3.60 |

| TiO2 (%) | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.06 |

| Al2O3 (%) | 9.98 | 8.30 | 7.69 | 7.96 | 7.82 | 8.71 | 9.05 | 8.13 | 9.43 | 8.66 | 7.84 | 8.22 | 10.17 | 10.24 | 10.57 | 9.26 | 8.88 | 0.96 |

| Fe2O3 (%) | 21.31 | 23.02 | 22.59 | 25.17 | 25.88 | 21.31 | 23.31 | 23.31 | 19.02 | 22.88 | 25.45 | 23.45 | 28.74 | 27.31 | 21.02 | 20.59 | 23.40 | 2.58 |

| CaO (%) | 9.49 | 10.30 | 12.54 | 9.63 | 10.71 | 9.30 | 9.48 | 9.53 | 7.91 | 9.27 | 8.65 | 12.88 | 4.49 | 5.11 | 7.56 | 7.62 | 9.03 | 2.23 |

| MgO (%) | 1.68 | 1.46 | 1.36 | 1.34 | 1.46 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.41 | 1.69 | 1.83 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 1.24 | 1.46 | 1.91 | 1.71 | 1.50 | 0.20 |

| S (%) | 2.20 | 2.24 | 3.28 | 5.05 | 4.54 | 2.94 | 3.99 | 4.25 | 4.22 | 3.11 | 2.66 | 2.93 | 12.30 | 10.90 | 4.16 | 3.49 | 4.52 | 2.90 |

| Cu (%) | 0.059 | 0.100 | 0.153 | 0.137 | 0.161 | 0.085 | 0.070 | 0.144 | 0.047 | 0.069 | 0.127 | 0.103 | 0.171 | 0.139 | 0.075 | 0.049 | 0.106 | 0.042 |

| Pb (%) | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.06 |

| Zn (%) | 0.24 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.24 |

| Co (%) | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| Ni (%) | 0.016 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.003 |

| Mn (%) | 0.164 | 0.161 | 0.189 | 0.180 | 0.177 | 0.150 | 0.164 | 0.164 | 0.123 | 0.145 | 0.156 | 0.188 | 0.105 | 0.104 | 0.119 | 0.132 | 0.151 | 0.028 |

| Cr (%) | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.036 | 0.036 | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.027 | 0.025 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.022 | 0.007 |

| Ba (%) | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| As (%) | 0.132 | 0.034 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.035 | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.732 | 0.266 | 0.065 | 0.032 | 0.541 | 0.550 | 0.195 | 0.163 | 0.179 | 0.228 |

| Bi (%) | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.003 |

| Ag (µg/g) | 8 | 11 | 16 | 19 | 16 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 8 | 6 | 12 | 3 |

| MS [10−6 m3kg−1] | 1.465 | 1.997 | 1.528 | 2.230 | 2.766 | 2.034 | 2.428 | 1.673 | 2.363 | 0.687 | 1.217 | 1.502 | 4.643 | 4.724 | 1.965 | 1.991 | 2.201 | 1.093 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrović, S.; Nikolić, N.; Stojanović, J.; Cvetkov, V.; Simić, V.; Malbašić, J.; Obrenović, L.; Životić, D. Preliminary Study of Geochemical, Mineralogical and Magnetic Susceptibility Properties of Flotation Tailings from the Pb-Zn-Cu-Ag Rudnik Mine, Serbia. Minerals 2025, 15, 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121287

Petrović S, Nikolić N, Stojanović J, Cvetkov V, Simić V, Malbašić J, Obrenović L, Životić D. Preliminary Study of Geochemical, Mineralogical and Magnetic Susceptibility Properties of Flotation Tailings from the Pb-Zn-Cu-Ag Rudnik Mine, Serbia. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121287

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrović, Stefan, Nenad Nikolić, Jovica Stojanović, Vesna Cvetkov, Vladimir Simić, Jovana Malbašić, Ljiljana Obrenović, and Dragana Životić. 2025. "Preliminary Study of Geochemical, Mineralogical and Magnetic Susceptibility Properties of Flotation Tailings from the Pb-Zn-Cu-Ag Rudnik Mine, Serbia" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121287

APA StylePetrović, S., Nikolić, N., Stojanović, J., Cvetkov, V., Simić, V., Malbašić, J., Obrenović, L., & Životić, D. (2025). Preliminary Study of Geochemical, Mineralogical and Magnetic Susceptibility Properties of Flotation Tailings from the Pb-Zn-Cu-Ag Rudnik Mine, Serbia. Minerals, 15(12), 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121287