Selective Synthesis of FAU- and CHA-Type Zeolites from Fly Ash: Impurity Control, Phase Stability, and Water Sorption Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Zeolite Synthesis

2.2.1. Acid Leaching

2.2.2. Alkali Fusion

2.2.3. Hydrothermal Synthesis

2.3. Water Sorption Measurements

2.4. Characterization

3. Results

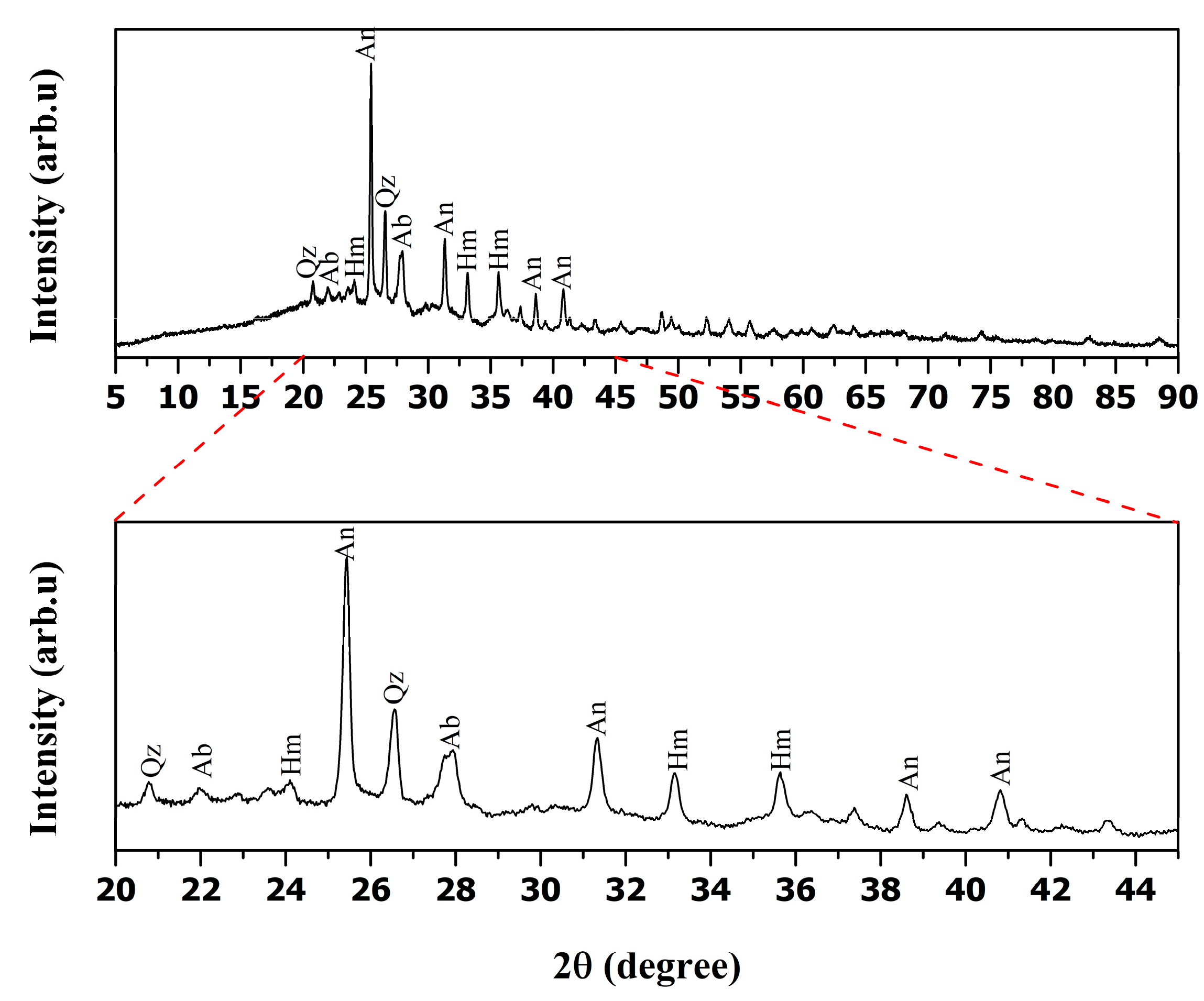

3.1. Characterization of Fly Ash

3.2. Acid Leaching

3.3. FAU-Type Zeolite Synthesis

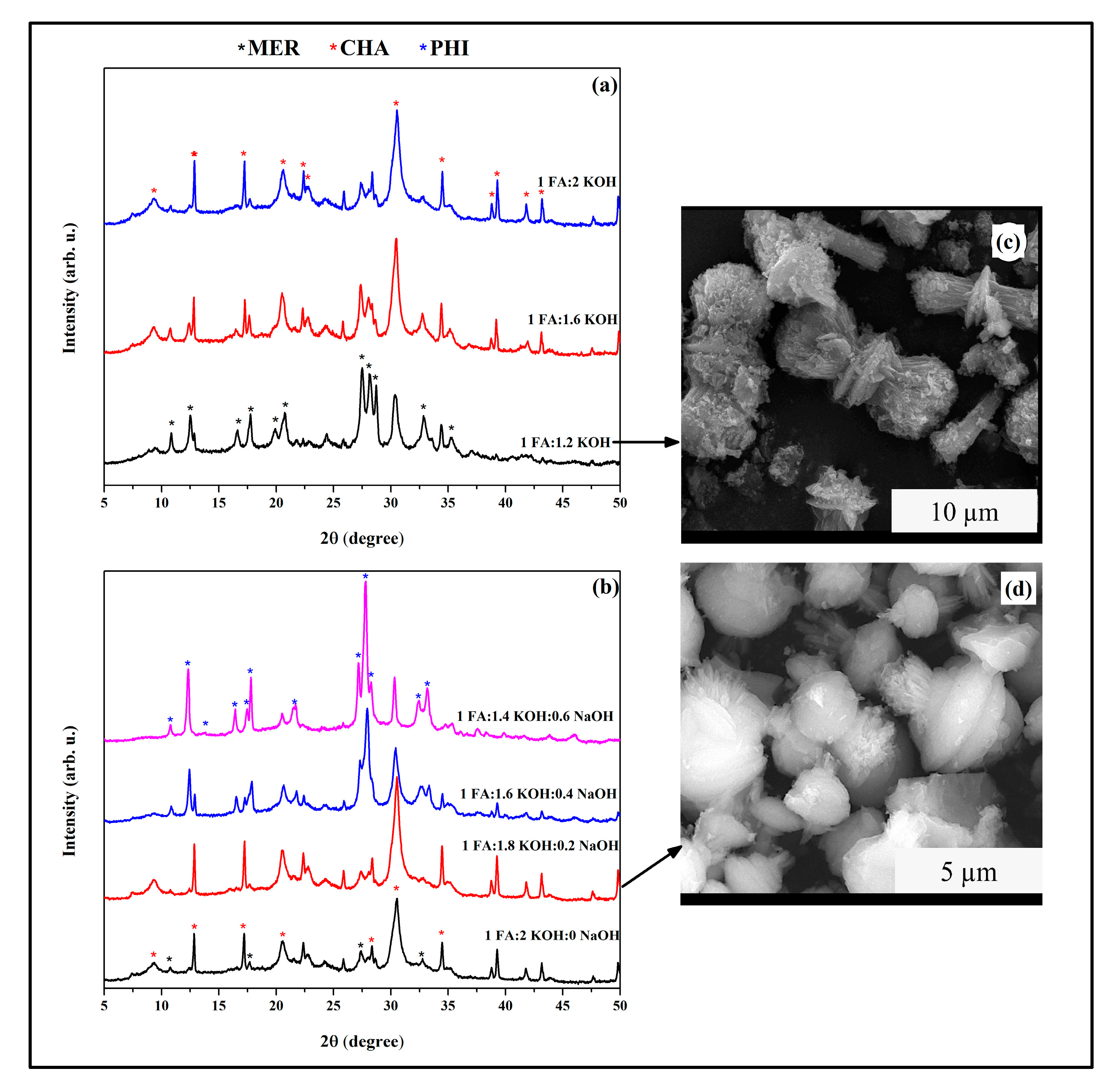

3.4. CHA-Type Zeolite Synthesis

3.5. Water Sorption Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Acid pretreatment (5 M HCl) effectively removed Ca-, Fe-, and S-bearing impurities and increased the Si/Al ratio from 1.2 to 2.6, enabling the formation of high-silica frameworks.

- FAU crystallization was optimized at 95 °C for 12 h, while longer synthesis promoted transformation into GIS, demonstrating the metastable–stable transition governed by Ostwald’s step rule.

- CHA crystallization was favored under moderate KOH or mixed-alkali conditions, whereas higher KOH concentrations stabilized MER and PHI. SEM confirmed distinct morphologies associated with each framework.

- Water sorption tests revealed that metastable FAU and CHA exhibited superior adsorption capacities (~23 wt% and ~18 wt%) compared to their stable analogues GIS and MER (~12–13 wt%).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAR | Silicon-to-Aluminum Ratio |

| FAU | Faujasite (zeolite framework type) |

| CHA | Chabazite (zeolite framework type) |

| GIS | Gismondine (zeolite framework type) |

| MER | Merlinoite (zeolite framework type) |

| LTA | Linde Type A zeolite |

| SOD | Sodalite zeolite |

| OSDA | Organic Structure Directing Agent |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction |

| XRF | X-Ray Fluorescence |

| SEM/FE-SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy/Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (surface area method) |

| DDW | Double-Distilled Water |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

References

- International Energy Agency. Global Energy Review 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Belviso, C. State-of-the-Art Applications of Fly Ash from Coal and Biomass: A Focus on Zeolite Synthesis Processes and Issues. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 65, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akın, S.Ş.; Kirdeciler, S.K.; Kazanç, F.; Akata, B. Critical Analysis of Zeolite 4A Synthesis through One-Pot Fusion Hydrothermal Treatment Approach for Class F Fly Ash. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 325, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, J. Zeolite Greenly Synthesized from Fly Ash and Its Resource Utilization: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M. A Review on the Utilization of Fly Ash. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 327–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, A. Handbook of Pollution Control and Waste Minimization; CRC PRESS: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; ISBN 0824705815. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.T.; Ji, X.S.; Sarker, P.K.; Tang, J.H.; Ge, L.Q.; Xia, M.S.; Xi, Y.Q. A Comprehensive Review on the Applications of Coal Fly Ash. Earth Sci. Rev. 2015, 141, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shen, Q.; Li, J.; Hao, Z.; Xu, Z.P.; Lu, G.Q.M. Iron-Exchanged FAU Zeolites: Preparation, Characterization and Catalytic Properties for N2O Decomposition. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 344, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Deimund, M.A.; Bhawe, Y.; Davis, M.E. Organic-Free Synthesis of CHA-Type Zeolite Catalysts for the Methanol-to-Olefins Reaction. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4456–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Singh, R.; Xiao, P.; Webley, P.A.; Zhai, Y. Zeolite Synthesis from Waste Fly Ash and Its Application in CO2 Capture from Flue Gas Streams. Adsorption 2011, 17, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzano, R.; Spagnuolo, M.; Medici, L.; Tateo, F.; Ruggiero, P. Characterization of Different Coal Fly Ashes for Their Application in the Synthesis of Zeolite X as Cation Exchanger for Soil Remediation. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2005, 14, 263–267. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W.; Wan, Z.; Daniels, J.; Li, Z.; Xiao, G.; Yu, J.; Xu, D.; Guo, H.; Zhang, D.; May, E.F.; et al. Synthesis of High Quality Zeolites from Coal Fly Ash: Mobility of Hazardous Elements and Environmental Applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Soe, J.T.; Zhang, S.; Ahn, J.W.; Park, M.B.; Ahn, W.S. Synthesis of Nanoporous Materials via Recycling Coal Fly Ash and Other Solid Wastes: A Mini Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 317, 821–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksiak, M.D.; Rimer, J.D. Synthesis of Zeolites in the Absence of Organic Structure-Directing Agents: Factors Governing Crystal Selection and Polymorphism. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2014, 30, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, M.; Oleksiak, M.D.; Chinta, S.; Rimer, J.D. Controlling Crystal Polymorphism in Organic-Free Synthesis of Na-Zeolites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, Y.; Miyake, K.; Tanaka, S.; Nishiyama, N.; Fukuhara, C.; Kong, C.Y. Phase-Controlled Synthesis of Zeolites from Sodium Aluminosilicate under OSDA/Solvent-Free Conditions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 2021, 1405–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Jin, Y. FAU Zeolites from Coal/Rice Husk Co-Combustion Ash (Co-Ash) for CO2 Adsorption: Synthesis, Characterization, Adsorption and Regeneration Performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 369, 133147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Zamora, R.M.; Solís-López, M.; Robles-Gutierrez, I.; Reyes-Vidal, Y.; Espejel-Ayala, F. A Statistical Industrial Approach for the Synthesis Conditions of Zeolites Using Fly Ash and Kaolinite. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2018, 37, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Poole, C. A Comparative Study Using Two Methods to Produce Zeolites from Fly Ash. Miner. Eng. 2004, 17, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Vaughan, J.; Xia, F.; Etschmann, B.; Brugger, J.; Brand, H.; Peng, H. Revealing the Effect of Anions on the Formation and Transformation of Zeolite LTA in Caustic Solutions: An In Situ Synchrotron PXRD Study. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 3660–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Pang, H.; Bai, R.; Wang, Q.; Chen, W.; Zheng, A.; Yan, W.; Yu, J. Anionic Tuning of Zeolite Crystallization. CCS Chem. 2021, 3, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksiak, M.D.; Soltis, J.A.; Conato, M.T.; Penn, R.L.; Rimer, J.D. Nucleation of FAU and LTA Zeolites from Heterogeneous Aluminosilicate Precursors. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 4906–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.P.; Mintova, S. Nanoporous Materials with Enhanced Hydrophilicity and High Water Sorption Capacity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 114, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijen, E.J.P.; Martens, J.A.; Jacobs, P.A. Zeolites and Their Mechanism of Synthesis. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1994, 84, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, A.; Mallette, A.J.; Jain, R.; Le, N.; Robles Hernández, F.C.; Rimer, J.D. Crystallization of Potassium-Zeolites in Organic-Free Media. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 341, 112026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasabeyoglu, P.; Akata, B. Calcination Effects on Meta-Forms of Kaolin and Halloysite: Role of Al-Si Spinel Crystallization in Zeolite Synthesis. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2025, 391, 113626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618–17a; Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://store.astm.org/c0618-17a.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Vassilev, S.V.; Vassileva, C.G. A New Approach for the Classification of Coal Fly Ashes Based on Their Origin, Composition, Properties, and Behaviour. Fuel 2007, 86, 1490–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Ding, M.; Vaughan, J. The Anion Effect on Zeolite Linde Type A to Sodalite Phase Transformation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 10292–10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, Y.; Ohmichi, T.; Mori, K.; Katayama, I.; Yamashita, H. Synthesis of Zeolite from Steel Slag and Its Application as a Support of Nano-Sized TiO2 Photocatalyst. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 2407–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, D.; Groppo, J.G.; Joshi, P.; Preda, D.V.; Gamliel, D.P.; Beers, T.; Schrock, M.; Hopps, S.D.; Morgan, T.D.; Zechmann, B.; et al. Electron Microbeam Investigations of the Spent Ash from the Pilot-Scale Acid Extraction of Rare Earth Elements from a Beneficiated Kentucky Fly Ash. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2025, 303, 104738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panitchakarn, P.; Klamrassamee, T.; Laosiripojana, N.; Viriya-Empikul, N.; Pavasant, P. Synthesis and Testing of Zeolite from Industrial-Waste Coal Fly Ash as Sorbent for Water Adsorption from Ethanol Solution. Eng. J. 2014, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.M.; Wang, B.; Li, W.; Cui, L.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, F. High-Efficiency Leaching of Al and Fe from Fly Ash for Preparation of Polymeric Aluminum Ferric Chloride Sulfate Coagulant for Wastewater Treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 306, 122545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akın, S.Ş. Pore Engineering and Surface Functionalization of Porous Carbon Structures Derived from Biochar, and Zeolites Derived from Fly Ashes; Middle East Technical University: Ankara, Turkey, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Valeev, D.; Mikhailova, A.; Atmadzhidi, A. Kinetics of Iron Extraction from Coal Fly Ash by Hydrochloric Acid Leaching. Metals 2018, 8, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treacy, M.M.J.; Higgins, J.B. Collection of Simulated XRD Powder Patterns for Zeolites Editors; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Julbe, A.; Drobek, M. Zeolite A Type. In Encyclopedia of Membranes; Drioli, E., Giorno, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Luo, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. The Thermodynamics and Kinetics for the Removal of Copper and Nickel Ions by the Zeolite y Synthesized from Fly Ash. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Ji, N.; Song, C.; Ma, D.; Yan, G.; Liu, Q. Synthesis of CHA Zeolite Using Low Cost Coal Fly Ash. Procedia Eng. 2015, 121, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gong, H.; Goyal, N.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fang, X.; Jia, H.; Li, G.; Du, T. Green Synthesis Strategy of Chabazite Membrane and Its CO2/N2 Separation Performance. J. Porous Mater. 2021, 28, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Fang, X.; Wei, Y.; Shang, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, L. Synthesis of Nanocontainer Chabazites from Fly Ash with a Template- and Fluoride-Free Process for Cesium Ion Adsorption. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 4301–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, J.; Fan, Q.; Yang, R.; Yu, L. High Silica Zeolite Phi, a CHA Type Zeolite with ABC-D6R Stacking Faults. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 248, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Hayashida, N.; Yokoi, T.; Tatsumi, T. Direct Crystallization of CHA-Type Zeolite from Amorphous Aluminosilicate Gel by Seed-Assisted Method in the Absence of Organic-Structure-Directing Agents. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 196, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Shibata, J. Zeolite Synthesis from Coal Fly Ash by Hydrothermal Reaction Using Various Alkali Sources. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2002, 77, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skofteland, B.M.; Ellestad, O.H.; Lillerud, K.P. Potassium Merlinoite: Crystallization, Structural and Thermal Properties. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2001, 43, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, S.; Tan, Z.; Liu, X.; Cao, J. Rapid and High Efficient Synthesis of Zeolite W by Gel-like-Solid Phase Method. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 281, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, D.H. Synthesis of Faulted CHA-Type Zeolites with Controllable Faulting Probability. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 256, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Gao, F.; Sun, K.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhou, R. Green Synthesis of Highly CO2-Selective CHA Zeolite Membranes in All-Silica and Fluoride-Free Solution for CO2/CH4 Separations. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 11307–11314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Botella, E.; Valencia, S.; Rey, F. Zeolites in Adsorption Processes: State of the Art and Future Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 17647–17695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghojavand, S.; Dib, E.; Mintova, S. Flexibility in Zeolites: Origin, Limits, and Evaluation. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12430–12446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gölboylu, S.C. Synthesis of FAU and CHA Zeolites from Class C Fly ASH; Middle East Technical University: Ankara, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cundy, C.S.; Cox, P.A. The Hydrothermal Synthesis of Zeolites: Precursors, Intermediates and Reaction Mechanism. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 82, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Bruce, E.L.; Kencana, K.S.; Hong, J.; Wright, P.A.; Hong, S.B. Highly Cooperative CO2 Adsorption via a Cation Crowding Mechanism on a Cesium-Exchanged Phillipsite Zeolite. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202305816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, F.; Hashmi, A.R.; Zheng, X.; Pan, Q.; Wang, B.; Gan, Z. Progress in Zeolite–Water Adsorption Technologies for Energy-Efficient Utilization. Energy 2024, 308, 133001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, H.; Mseddi, S.; Djemel, S. Preparation and Characterization of Na-LTA Zeolite from Tunisian Sand and Aluminum Scrap. Phys. Procedia 2009, 2, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, R.C.F.; Da, D.; Oliveira, S.; Pergher, S.B.C.; Zubkova, N.V.; Djerdj, I. Interzeolitic Transformation of Clinoptilolite into GIS and LTA Zeolite. Minerals 2021, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkowski, A.; Michalik, M. Statistical Approach to the Transformation of Fly Ash into Zeolites. Mineral. Pol. 2007, 38, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pasabeyoglu, P.; Moumin, G.; de Oliveira, L.; Roeb, M.; Akata, B. Solarization of the Zeolite Production: Calcination of Kaolin as Proof-of-Concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| wt.% | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | SO3 | Fe2O3 | Other Oxides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fly Ash | 36.4 | 23.3 | 14.7 | 9.26 | 7.81 | 8.53 |

| Phase Name | Content (%) |

|---|---|

| Anhydrite (CaSO4) | 56 |

| Quartz (SiO2) | 12.4 |

| Albite, calcian (NaCaAlSi3O8) | 21.2 |

| Lime (CaO) | 2.0 |

| Hematite (Fe2O3) | 8.7 |

| Sample | Si/Al Ratio | SO3 (%) | CaO (%) | Fe2O3 (%) | Impurity Phases (XRD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Fly Ash | 1.33 | 9.26 | 14.7 | 7.81 | Albite (Ca), Hematite, Anhydrite |

| 1M HCl-Leached FA | 1.69 | 6.01 | 7.47 | 8.18 | Minor Albite (Ca), Hematite, Trace Anhydrite |

| 2M HCl-Leached FA | 2.19 | 3.29 | 4.31 | 8.74 | Minor Albite (Ca), Minor Hematite |

| 3M HCl-Leached FA | 2.57 | 3.01 | 3.62 | 6.41 | Very Minor Hematite |

| 4M HCl-Leached FA | 2.77 | 1.96 | 3.35 | 4.28 | Trace Hematite |

| 5M HCl-Leached FA | 2.85 | 0.97 | 2.65 | 2.22 | - |

| Zeolites | Gel Composition (FA:KOH:NaOH:H2O) | Temperature (°C) | Synthesis Time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAU | 1:0:1.2:10 | 95 | 12 |

| GIS | 1:0:1.2:10 | 95 | 24 |

| CHA | 1:1.8:0.2:10 | 100 | 96 |

| MER | 1:1.2:0:10 | 100 | 96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gölboylu, S.C.; Akın, S.Ş.; Akata, B. Selective Synthesis of FAU- and CHA-Type Zeolites from Fly Ash: Impurity Control, Phase Stability, and Water Sorption Performance. Minerals 2025, 15, 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111153

Gölboylu SC, Akın SŞ, Akata B. Selective Synthesis of FAU- and CHA-Type Zeolites from Fly Ash: Impurity Control, Phase Stability, and Water Sorption Performance. Minerals. 2025; 15(11):1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111153

Chicago/Turabian StyleGölboylu, Selin Cansu, Süleyman Şener Akın, and Burcu Akata. 2025. "Selective Synthesis of FAU- and CHA-Type Zeolites from Fly Ash: Impurity Control, Phase Stability, and Water Sorption Performance" Minerals 15, no. 11: 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111153

APA StyleGölboylu, S. C., Akın, S. Ş., & Akata, B. (2025). Selective Synthesis of FAU- and CHA-Type Zeolites from Fly Ash: Impurity Control, Phase Stability, and Water Sorption Performance. Minerals, 15(11), 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111153