Effect of Ammonium Chloride on the Efficiency with Which Copper Sulfate Activates Marmatite: Change in Solution Composition and Regulation of Surface Composition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Flotation Experiments

2.3. Adsorption Tests

2.4. XPS Analysis

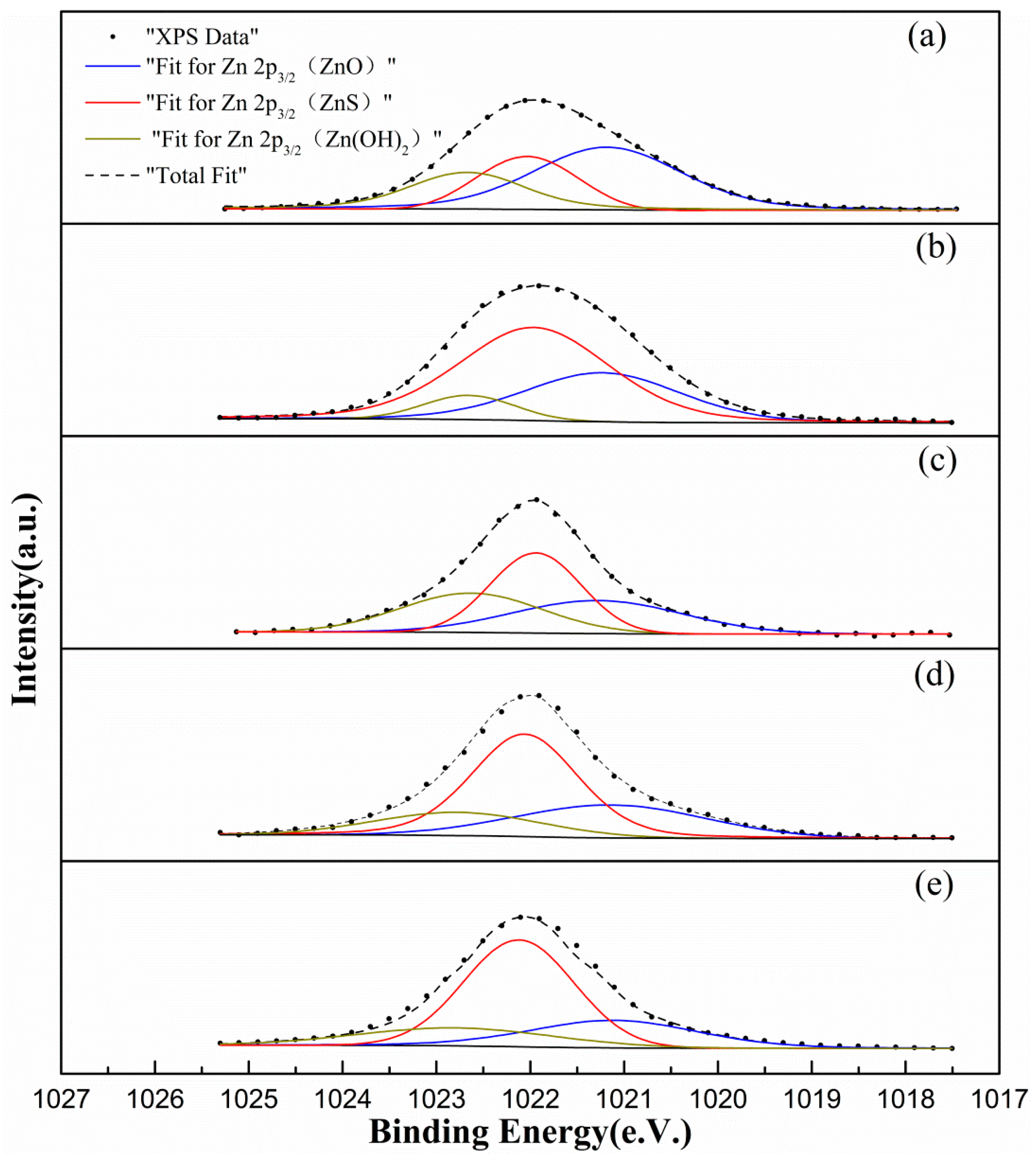

- (a)

- Deionized water,

- (b)

- 6 × 10−4 mol/L NH4Cl,

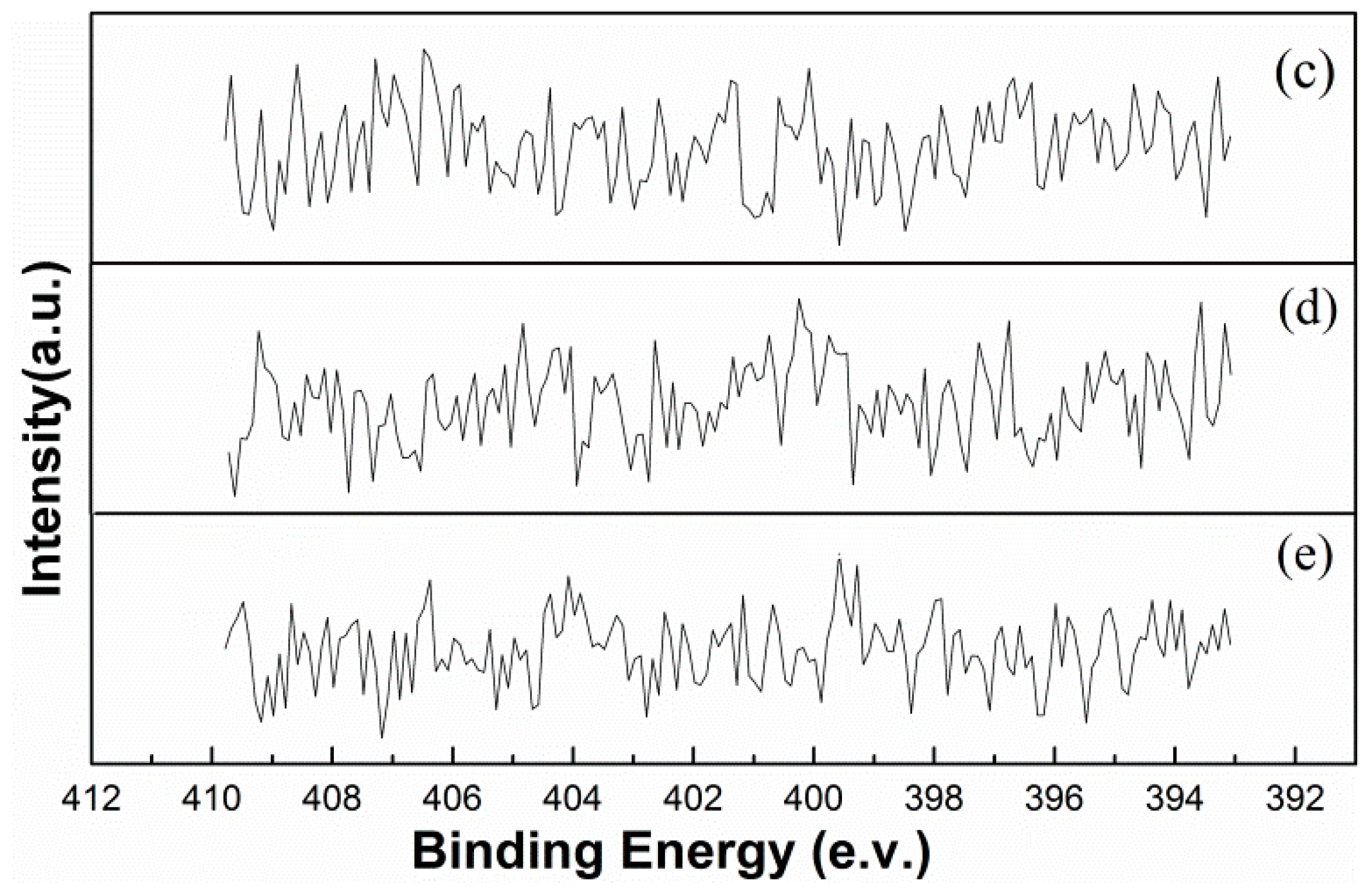

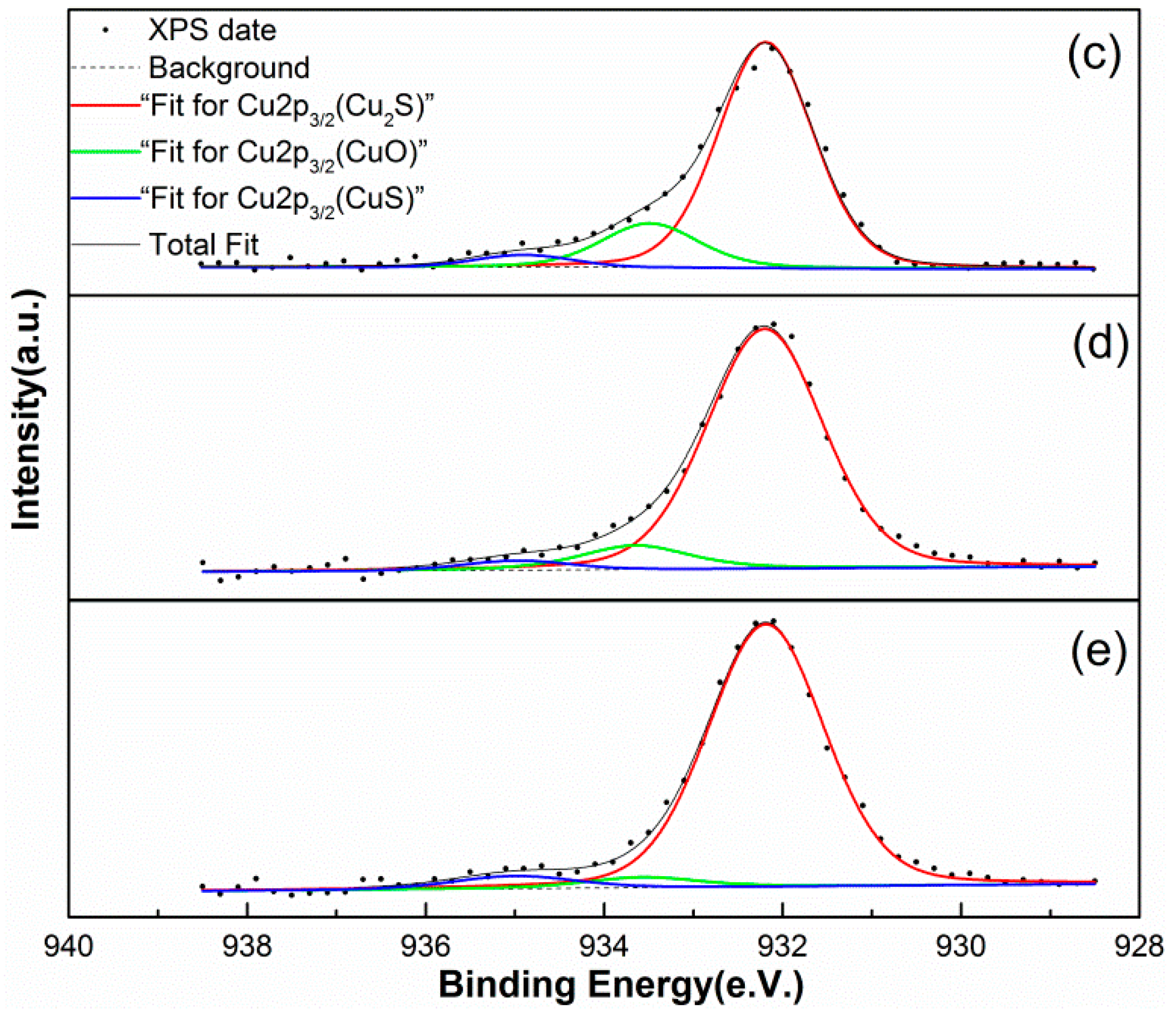

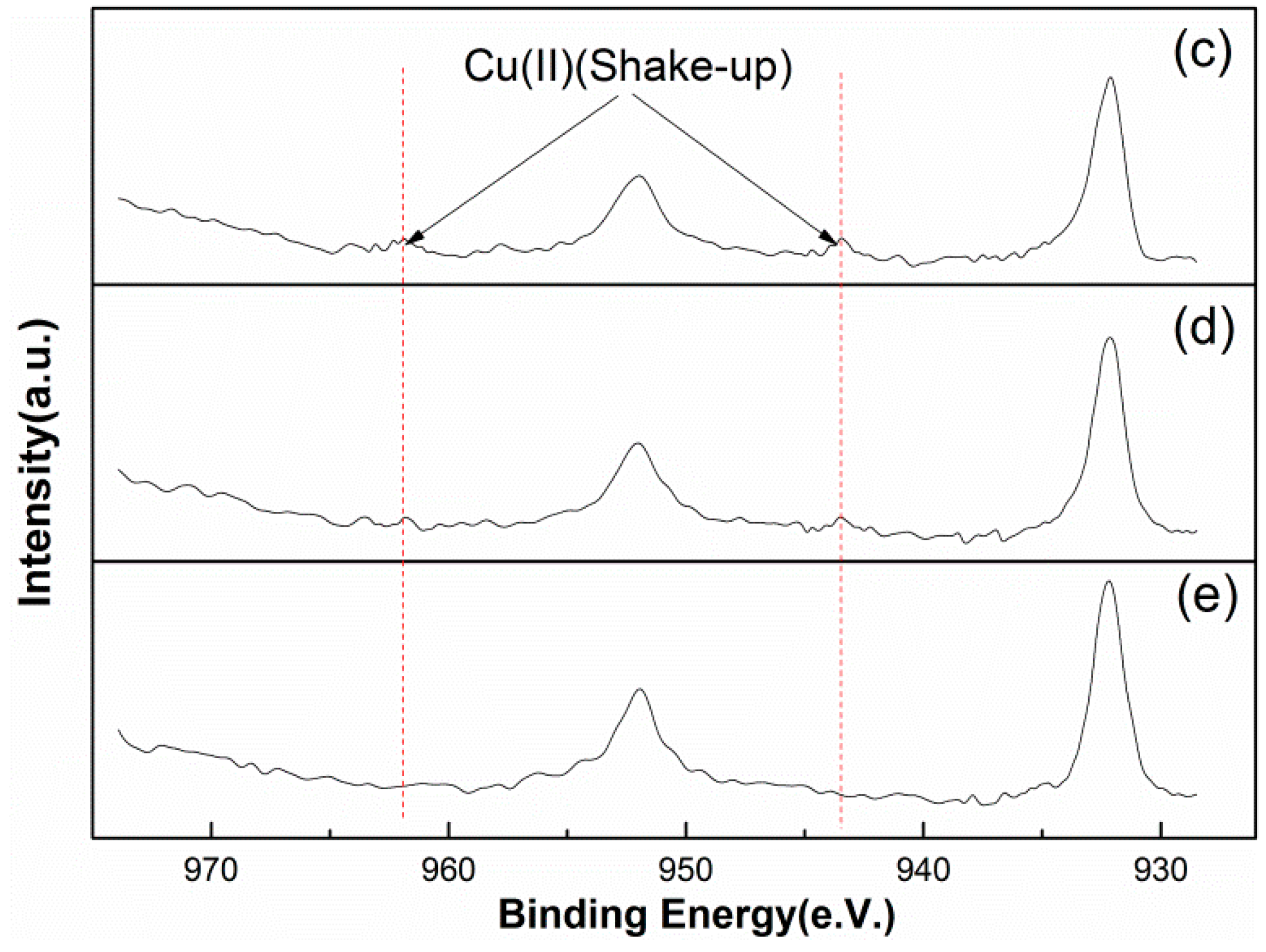

- (c)

- 3 × 10−5 mol/L CuSO4,

- (d)

- 3 × 10−5 mol/L CuSO4 + 3 × 10−4 mol/L NH4Cl,

- (e)

- 3 × 10−5 mol/L CuSO4 + 6 × 10−4 mol/L NH4Cl.

2.5. Concentration of Copper in Solution

3. Results

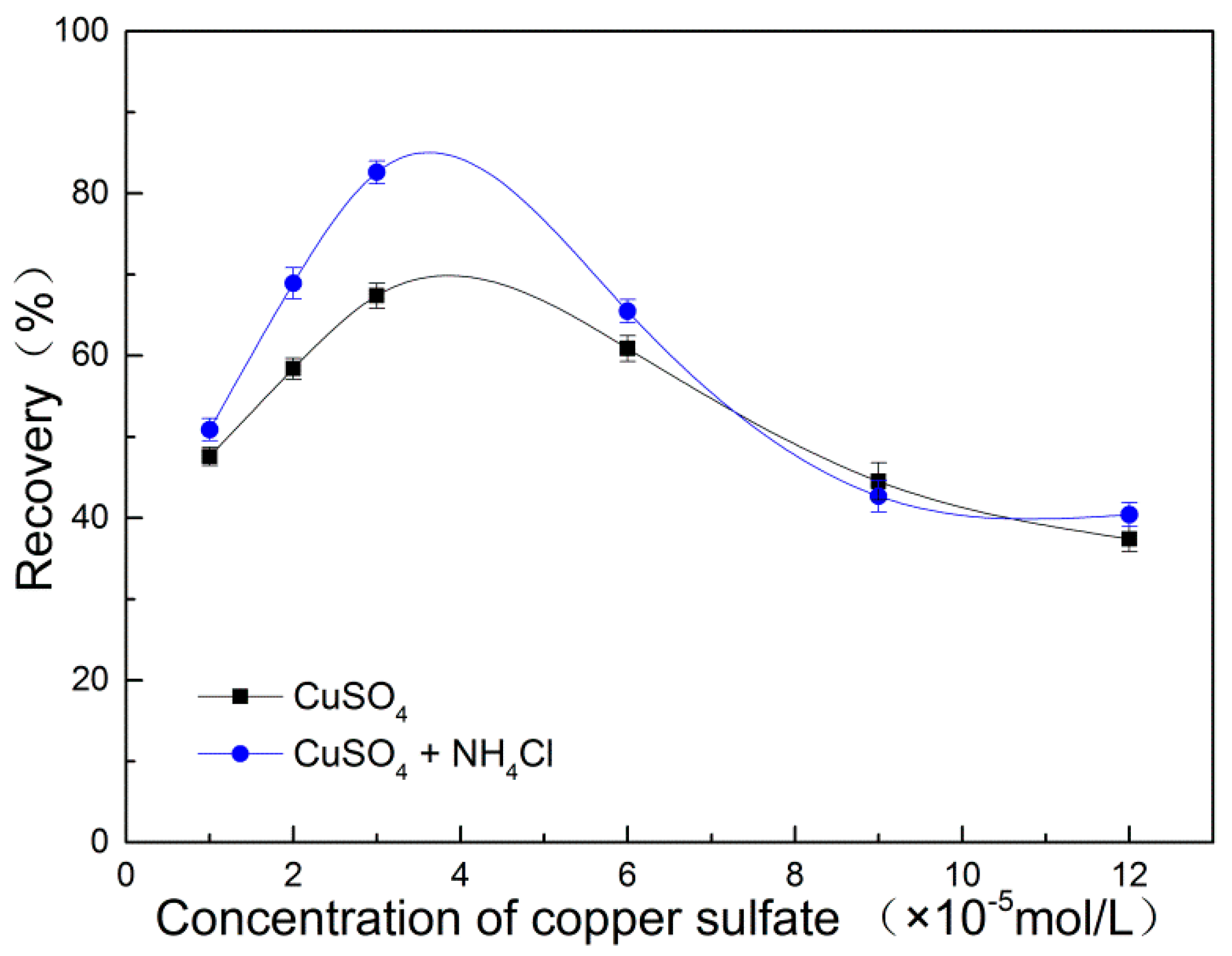

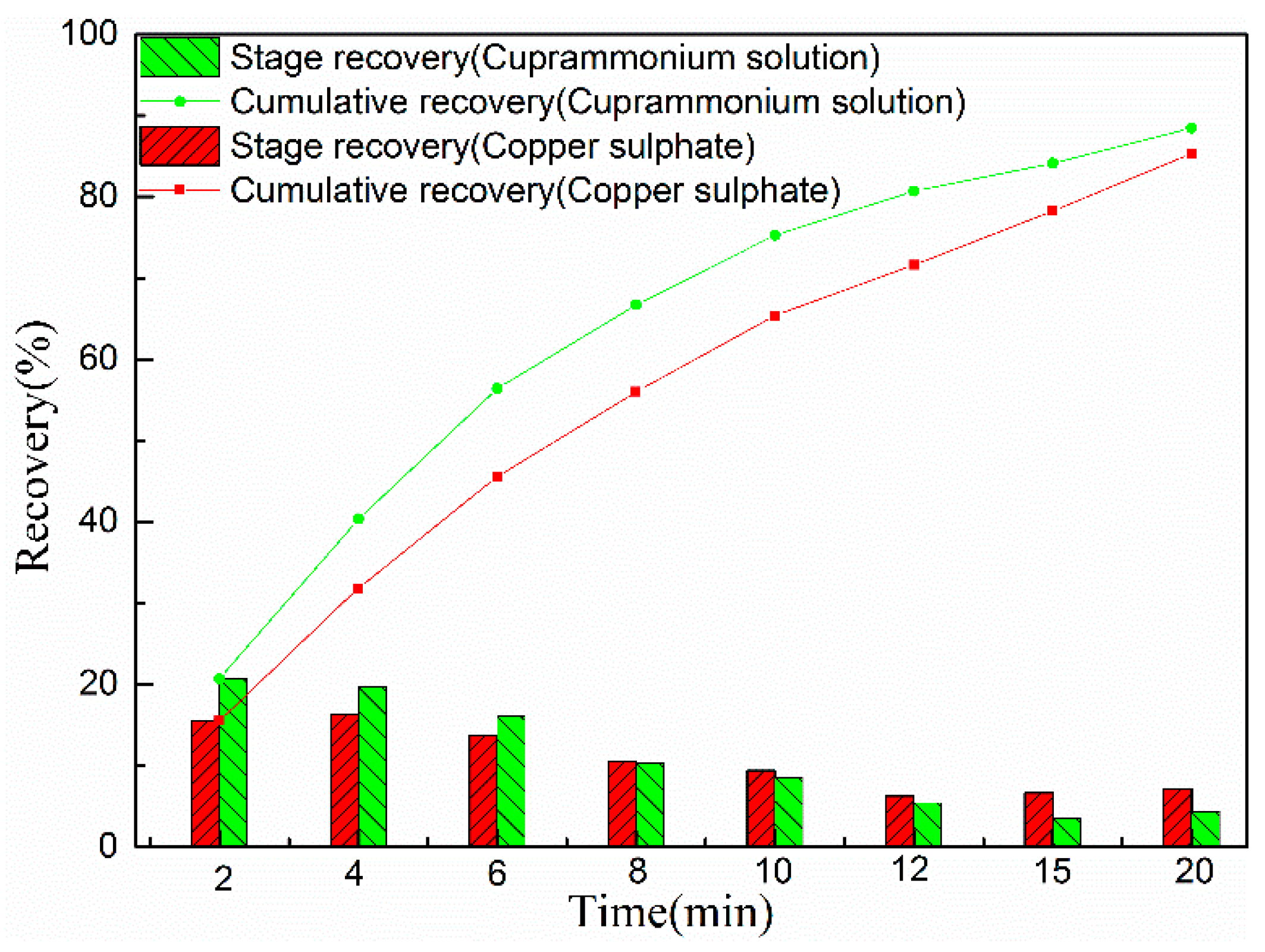

3.1. Flotation Results

3.2. Adsorption Test Results

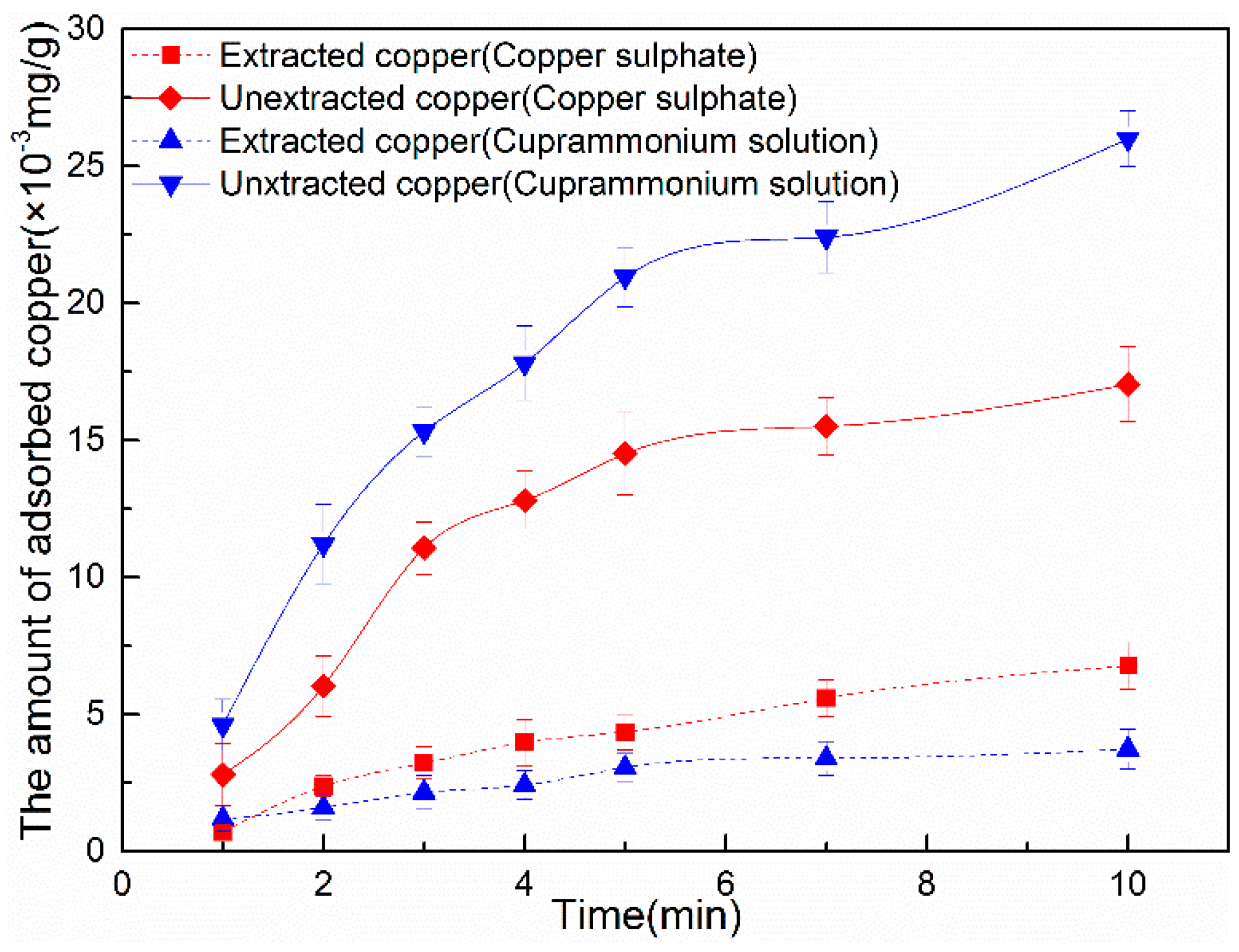

3.2.1. Copper Adsorption

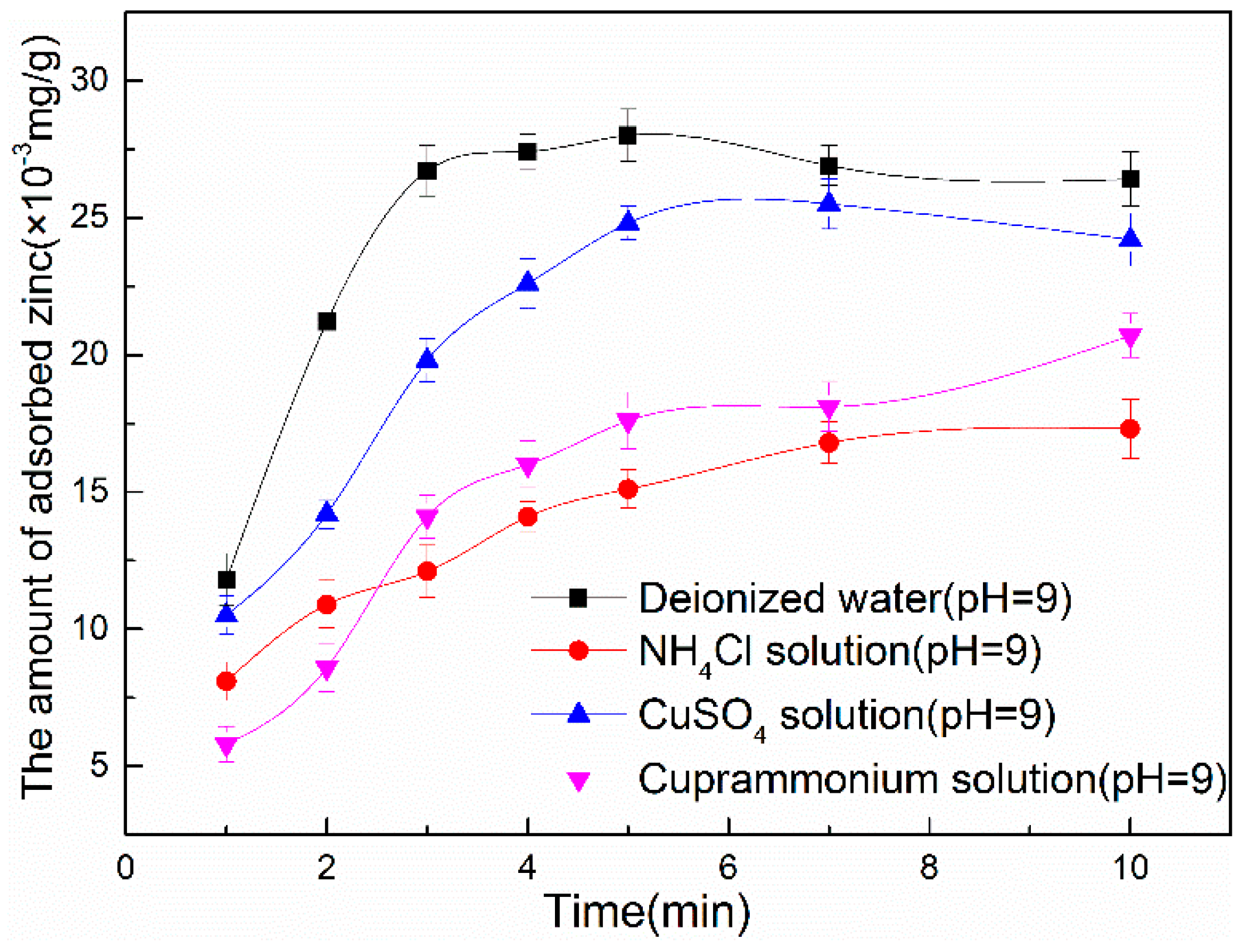

3.2.2. Zinc Hydroxide Adsorption

3.3. XPS Studies

3.3.1. Surface Nitrogen Analysis

3.3.2. Surface Zinc Analysis

3.3.3. Surface Copper Analysis

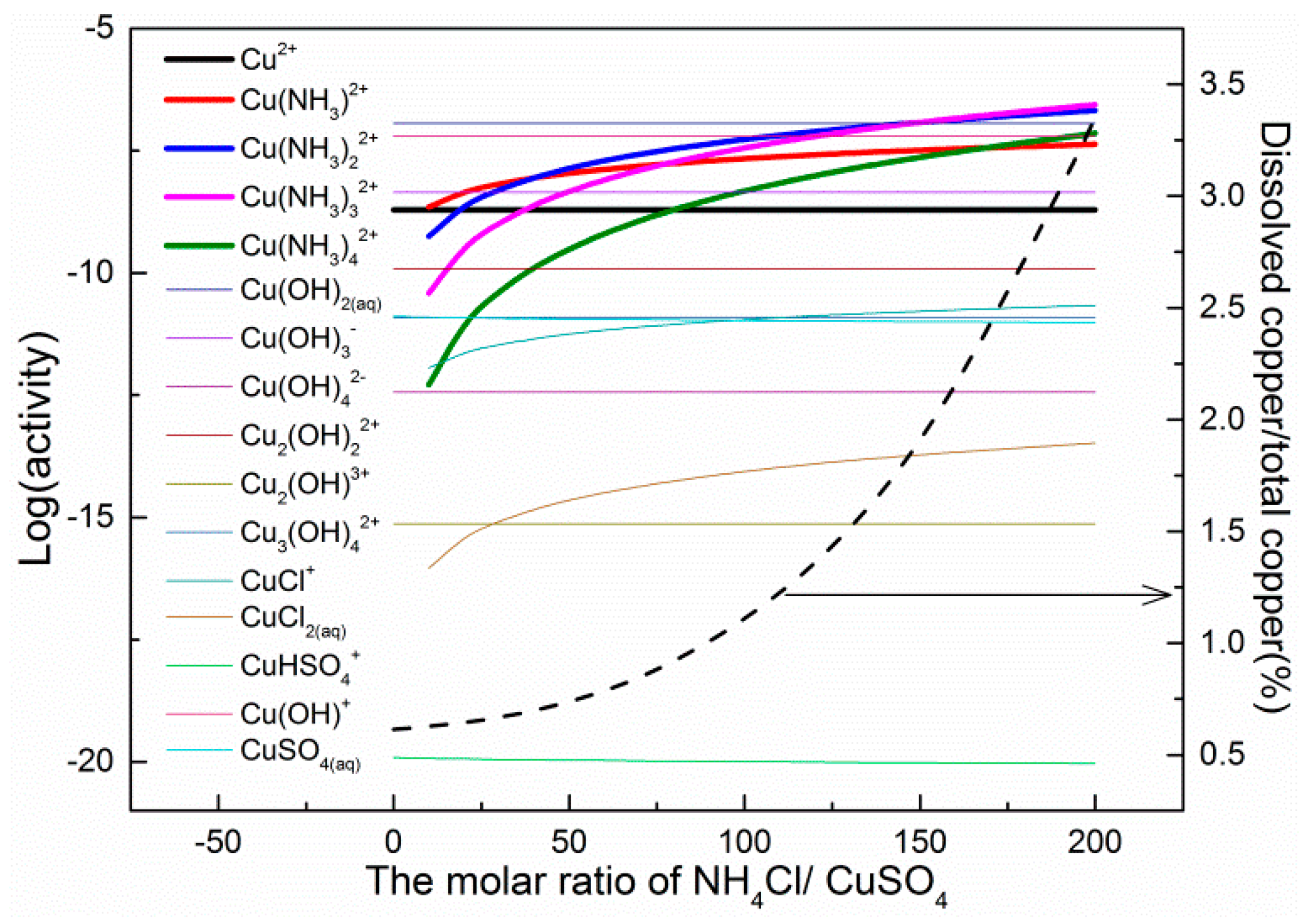

3.4. Solution Components

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

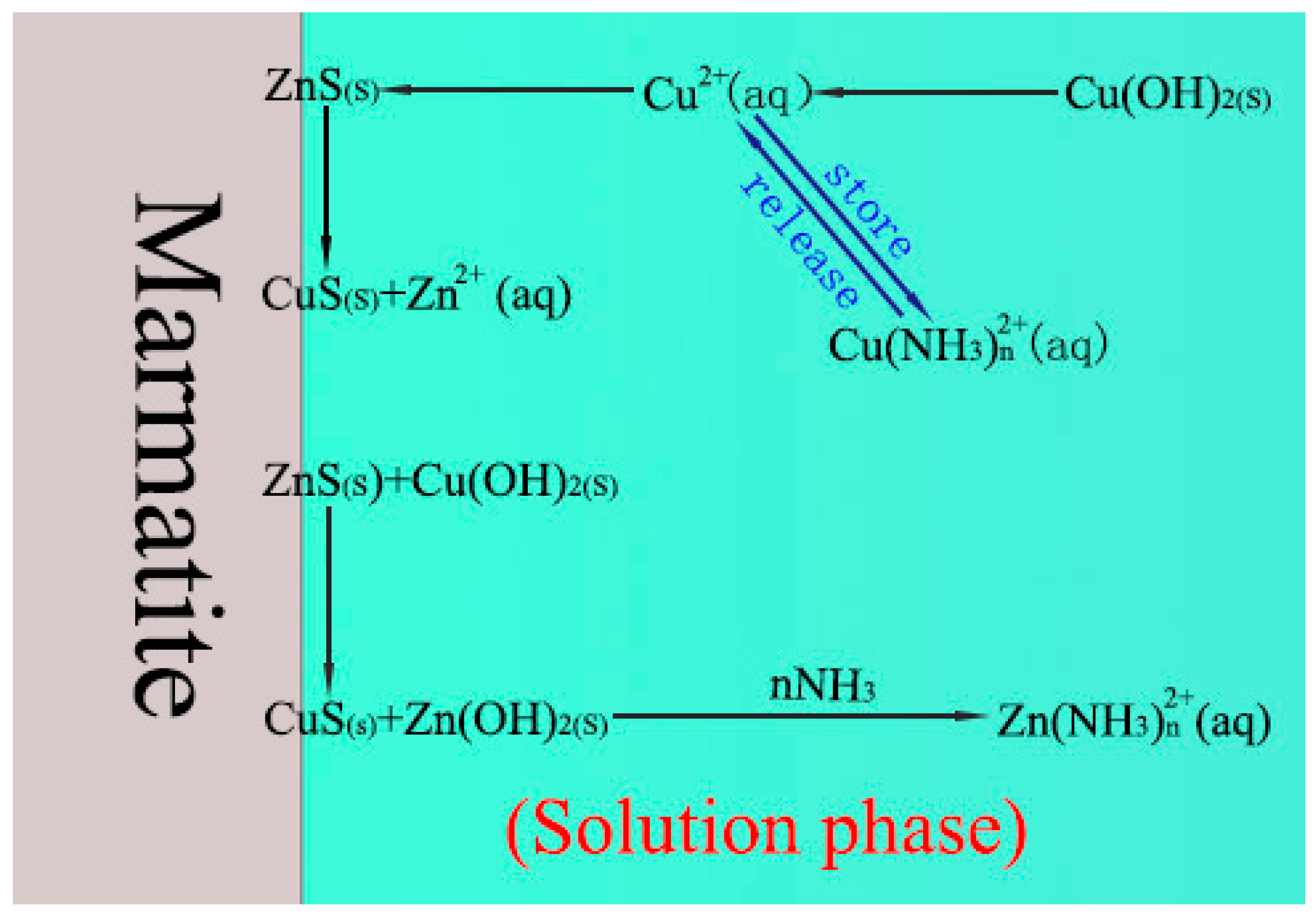

- The addition of NH4Cl to the copper sulfate results in a significant change in the composition of the solution (critically, it causes the presence of NH3(aq) and Cu(NH3)n2+). These changes subsequently lead to the regulation of the surface composition of the marmatite.

- (2)

- Aqueous ammonia, NH3(aq), promotes the dissolution of zinc hydroxide on the marmatite surface through the formation of zinc–ammonia complex ions and then promotes the conversion of copper hydroxide to copper sulfide on the mineral surface. This increases the amount of copper sulfide on the surface, and also significantly reduces the hydrophilic hydroxide content of the surface, thereby enhancing the activation effect.

- (3)

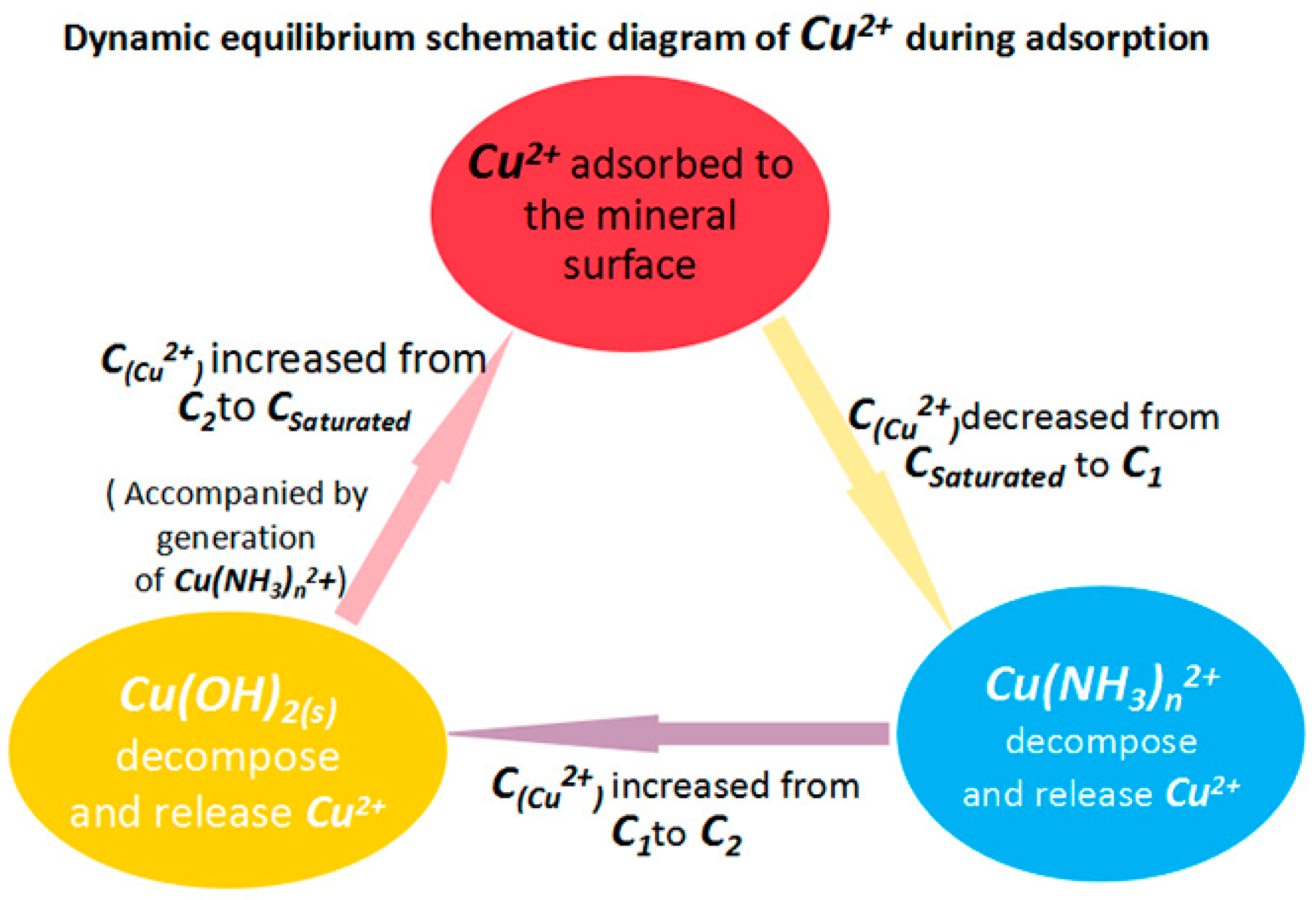

- The Cu(NH3)n2+ species buffer the copper ion concentration by storing and releasing copper ions (and hence resists large drops in Cu2+ ion concentration). This effect helps facilitate the adsorption of copper ions and formation of copper sulfide and finally promotes the activation effect.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mudd, G.M.; Jowittl, S.M.; Werner, T.T. The world’s lead–zinc mineral resources: Scarcity, data, issues and opportunities. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 80, 1160–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irannajad, M.; Ejtemaei, M.; Gharabaghi, M. The effect of reagents on selective flotation of smithsonite-calcite-quartz. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, A.N.; Rashchi, F. Separation of oxidized zinc minerals from tailings: Influence of flotation reagents. Miner. Eng. 2008, 21, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Lauten, R.A. The depression of pyrite in selective flotation by different reagent systems—A Literature revie. Miner. Eng. 2016, 96–97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.R.; Leja, J. Surface Chemistry of Forth Flotation: Reagents and Mechanisms; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, A.; Fornasiero, D.; Ralston, J. Characterisation of sphalerite and pyrite flotation samples by XPS and ToF–SIMS. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2003, 70, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Fornasiero, D.; Skinner, W. Correlation between copper-activated pyrite flotation and surface species: effect of pulp oxidation potential. Miner. Eng. 2005, 18, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Bozkurt, V.; Finch, J.A. Pyrite flotation in the presence of metal ions and sphalerite. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1997, 52, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.Z.; Fornasiero, D.; Ralston, J. Effect of collectors, conditioning pH and gases in the separation of sphalerite from pyrite. Miner. Eng. 1998, 11, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichmann, T.K.; Finch, J.A. The role of copper ions in sphalerite–pyrite flotation selectivity. Miner. Eng. 2001, 14, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J.A.; Rao, S.R.; Nesset, J.E. Iron control in mineral processing. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Mineral Processors of CIM, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 23–25 January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lascelles, D.; Sui, C.C.; Finch, J.A.; Butler, I.S. Copper ion mobility in sphalerite activation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2001, 186, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisener, C.; Gerson, A. An investigation of the Cu (II) adsorption mechanism on pyrite by ARXPS and SIMS. Miner. Eng. 2000, 13, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.; Fornasiero, D.; Ralston, J. Effect of iron content in sphalerite on flotation. Miner. Eng. 2005, 18, 1120–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.C.P.; Grano, S.R. Mechanism for the recovery of silicate gangue minerals in the flotation of ultrafine sphalerite. Miner. Eng. 2007, 20, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Grano, S. Galvanic interaction of grinding media with pyrite and its effect on flotation. Miner. Eng. 2005, 18, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmeleva, T.N.; Skinner, W.; Beattie, D.A. Depressing mechanisms of sodium bisulphite in the collectorless flotation of copper–activated sphalerite. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2005, 76, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, N.P. The activation of sulphide minerals for flotation: A review. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1997, 52, 81–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, A.R.; Lange, A.G.; Prince, K.E.; Smart, R.S.C. The mechanism of copper activation of sphalerite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1999, 137, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasiero, D.; Ralston, J. Effect of surface oxide/hydroxide products on the collectorless flotation of copper-activated sphalerite. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2006, 78, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestidge, C.A.; Skinner, W.M.; Ralston, J.; Smart, R.S.C. Copper (II) activation and cyanide deactivation of zinc sulphide under mildly alkaline conditions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1997, 108, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, A.N.; Skinner, W.M.; Harmer, S.L.; Pring, A.; Lamb, R.N.; Fan, L.J.; Yang, Y.W. Examination of the proposition that Cu (II) can be required for charge neutrality in a sulfide lattice-Cu in tetrahedrites and sphalerite. Can. J. Chem. 2007, 85, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñals, J.; Fuentes, G.; Hernández, M.C.; Herreros, O. Transformation of sphalerite particles into copper sulfide particles by hydrothermal treatment with Cu (II) ions. Hydrometallurgy 2004, 75, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yoon, R.H. Electrochemistry of copper activation of sphalerite at pH 9.2. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 58, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, J.; Healy, T.W. Activation of zinc sulphide with CuII, CdII and PbII: II. Activation in neutral and weakly alkaline media. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1980, 7, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirnezami, M.; Restrepo, L.; Finch, J.A. Aggregation of sphalerite: Role of zinc ions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 259, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Song, S.; He, J.; Rao, F.; Lopez-Valdivieso, A. Activation of high–iron marmatite in froth flotation by ammoniacal copper(II) solution. Miner. Eng. 2007, 20, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Hou, K.; Yang, B.; Tong, X. Activation of sphalerite by ammoniacal copper solution in froth flotation. J. Chem. 2016, 2016, 7614890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumball, J.A.; Richmond, G.D. Richmond. Measurement of oxidation in a base metal flotation circuit by selective leaching with disodium EDTA. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1996, 48, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, C.H.F.; Rogers, J.W., Jr.; Shinn, N.D.; Kidd, K.B.; Tsang, K.L. Thermally grown Si3N4 thin films on Si (100): Surface and interfacial composition. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 15622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, T.; Mera, N.; Kanai, Y.; Nishimoto, C.; Tsutsui, S.; Hirakawa, T.; Negishi, N. Origin of visible-light activity of N-doped TiO2 photocatalyst: Behaviors of N and S atoms in a wet N-doping process. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 128, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.K.; Seong, T.Y. Electrical characteristics of Pt Schottky contacts on sulfide-treated n-type ZnO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 022101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroubaix, G.; Marcus, P. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy analysis of copper and zinc oxides and sulphides. Surf. Interface Anal. 1992, 18, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Leung, K.T. Controlled growth of two-dimensional and one-dimensional ZnO nanostructures on indium tin oxide coated glass by direct electrodeposition. Langmuir 2008, 24, 9707–9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piva, D.H.; Piva, R.H.; Rocha, M.C.; Dias, J.A.; Montedo, O.R.K.; Malavazi, I.; Morelli, M.R. Antibacterial and photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanoparticles from Zn(OH)2, dehydrated by azeotropic distillation, freeze drying, and ethanol washing. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefedov, V.I.; Salyn, Y.V.; Solozhenkin, P.M.; Pulatov, G.Y. X-ray photoelectron study of surface compounds formed during flotation of minerals. Surf. Interface Anal. 1980, 2, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Tomizuka, H.; Takahashi, M.; Hoshi, T. Methods of Powder Sample Mounting and Their Evaluations in XPS Analysis. Hyomen Kagaku 1995, 16, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotbi, M.Y.; Rahmati, Z. Nanostructured copper and copper oxide thin films fabricated by hydrothermal treatment of copper hydroxide nitrate. Mater. Des. 2015, 85, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.P.; Gerson, A.R. A review of the fundamental studies of the copper activation mechanisms for selective flotation of the sulfide minerals, sphalerite and pyrite. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 145, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Zhong, H.; Xu, H.; Jia, H.; Liu, G. Flotation behavior and adsorption mechanism of α–hydroxyoctylphosphinic acid to malachite. Miner. Eng. 2015, 71, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.; Roig, N.; Papiol, G.G.; Pérez-Gallego, E.; Schuhmacher, M. Prediction of the bioavailability of potentially toxic elements in freshwaters. Comparison between speciation models and passive samplers. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, M.; Renman, G.; Gustafsson, J.P.; Renman, A. Phosphorus removal performance and speciation in virgin and modified argon oxygen decarburisation slag designed for wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2015, 87, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, G.; Zhang, H.; Krampe, J.; Muster, T.; Gao, B.; Zhu, N.; Jin, B. Applying a chemical equilibrium model for optimizing struvite precipitation for ammonium recovery from anaerobic digester effluent. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöstedt, C.; Löv, Å.; Olivecrona, Z.; Boye, K.; Kleja, D.B. Improved geochemical modeling of lead solubility in contaminated soils by considering colloidal fractions and solid phase EXAFS speciation. Appl. Geochem. 2018, 92, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchik, D.; Sánchez, A.; Garrido, J.M. Simulation and experimental validation of multiple phosphate precipitates in a saline industrial wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 118, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUPAC Stability Constants Database, Sc–Database and Mini–Scdatabase, Timble; Academic Software: Otley, UK, 2001.

| Component | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | S | Fe | Pb | Cu | Si | CaO | MgO | |

| Content (%) | 57.18 | 32.41 | 8.51 | 0.15 | 0.039 | 1.27 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| Sample | Atomic Concentration (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C 1s | O 1s | S 2p | Fe 2p | Zn 2p | Cu 2p | |

| a | 29.57 | 29.45 | 19.80 | 2.80 | 18.38 | 0.00 |

| b | 32.48 | 18.35 | 24.03 | 3.62 | 21.52 | 0.00 |

| c | 30.23 | 22.93 | 19.80 | 2.46 | 14.92 | 9.66 |

| d | 34.47 | 16.53 | 19.91 | 2.59 | 15.46 | 11.04 |

| e | 31.61 | 14.48 | 22.14 | 2.76 | 16.50 | 12.51 |

| Sample | Binding Energy (eV) | Total Amount of Zn Present (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn in ZnO | Zn in ZnS | Zn in Zn(OH)2 | As ZnO | As ZnS | As Zn(OH)2 | |

| a | 1021.18 | 1022.03 | 1022.67 | 50.53 | 24.75 | 24.72 |

| b | 1021.23 | 1021.96 | 1022.65 | 31.42 | 60.21 | 8.38 |

| c | 1021.28 | 1021.94 | 1022.63 | 30.43 | 39.38 | 30.18 |

| d | 1021.14 | 1022.06 | 1022.77 | 28.05 | 54.69 | 17.26 |

| e | 1021.11 | 1022.12 | 1022.79 | 24.34 | 58.13 | 17.53 |

| Sample | Binding Energy (eV) | Total Amount of Cu Present (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu in Cu2S | Cu in CuO | Cu in CuS | As Cu2S | As CuO | As CuS | |

| c | 932.19 | 933.57 | 934.96 | 79.35 | 16.57 | 4.07 |

| d | 932.20 | 933.65 | 934.98 | 88.71 | 8.28 | 3.01 |

| e | 932.17 | 933.56 | 935.00 | 90.52 | 3.95 | 5.53 |

| Molar Ratio of NH4Cl:CuSO4 | Measured Copper Concentration (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0506 |

| 10 | 0.0675 |

| 20 | 0.0796 |

| 50 | 0.0972 |

| 100 | 0.1078 |

| 200 | 0.1215 |

| Equilibrium | log K a |

|---|---|

| Zn2+ + NH3 ⇌ Zn(NH3)2+ | 2.35 |

| Zn2+ + 2NH3 ⇌ Zn(NH3)22+ | 4.80 |

| Zn2+ + 3NH3 ⇌ Zn(NH3)32+ | 7.31 |

| Zn2+ + 4NH3 ⇌ Zn(NH3)42+ | 9.46 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Feng, D.; Tong, X.; Yang, B.; Xie, X. Effect of Ammonium Chloride on the Efficiency with Which Copper Sulfate Activates Marmatite: Change in Solution Composition and Regulation of Surface Composition. Minerals 2018, 8, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8060250

Zhang S, Feng D, Tong X, Yang B, Xie X. Effect of Ammonium Chloride on the Efficiency with Which Copper Sulfate Activates Marmatite: Change in Solution Composition and Regulation of Surface Composition. Minerals. 2018; 8(6):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8060250

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shengdong, Dongxia Feng, Xiong Tong, Bo Yang, and Xian Xie. 2018. "Effect of Ammonium Chloride on the Efficiency with Which Copper Sulfate Activates Marmatite: Change in Solution Composition and Regulation of Surface Composition" Minerals 8, no. 6: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8060250

APA StyleZhang, S., Feng, D., Tong, X., Yang, B., & Xie, X. (2018). Effect of Ammonium Chloride on the Efficiency with Which Copper Sulfate Activates Marmatite: Change in Solution Composition and Regulation of Surface Composition. Minerals, 8(6), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8060250