1. Introduction

Given the expected future scarcity of minerals essential for technological advances and the energy transition, global interest in DSM has increased significantly over the past decade [

1]. These minerals, considered critical due to high demand and supply risk, are fundamental to the development of clean and digital technologies, prompting the mining sector to seek alternative sources amid declining ore grades and the rising costs and complexity of terrestrial deposits [

2,

3]. From a technology-use perspective, several of these metals underpin key applications such as battery cathodes (e.g., Co and Ni), electrification infrastructure (e.g., Cu in wiring, motors and transformers), and high-performance magnets for wind turbines and electric-vehicle motors [

4].

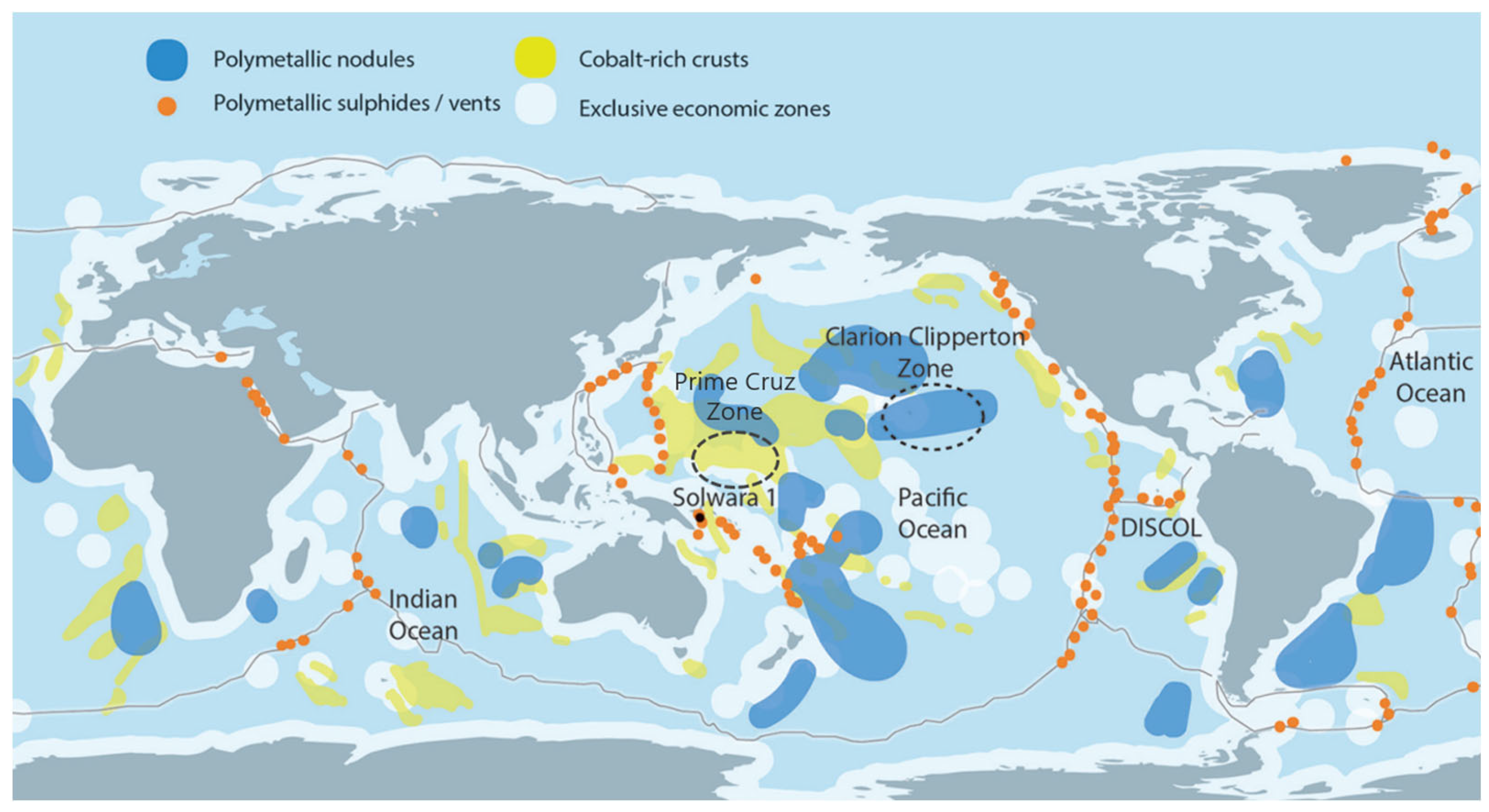

This interest is not driven by a single deposit but by a broad geographic distribution at a global oceanic scale, spanning mineralized zones across different oceans and under different jurisdictional regimes.

Figure 1 summarizes the global location of the main deposit types of interest for DSM and highlights several areas that have attracted scientific and exploratory attention.

In this context, some countries have begun to translate this interest into regulatory decisions and exploration plans. One example is Norway, which, in January 2024, became the first country to formally authorize deep-sea mineral exploration activities on its continental shelf [

6]. However, in December of the same year, the government decided to pause the granting of exploration licenses in response to growing environmental concerns, limited scientific certainty regarding the activity’s cumulative impacts, and the need to ensure a robust regulatory and scientific basis before proceeding [

7,

8]. This case highlights the inherent tensions between the drive to access new strategic resources and the requirement to establish a solid scientific and regulatory foundation prior to further development.

The extraction of mineral resources from the seafloor is primarily focused on three deposit types: polymetallic nodules, ferromanganese crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides (SMS), each of which involves different modes of interaction with the marine environment [

9]. Although other targets are also being explored, such as gas hydrates [

5], placers, phosphorites, and evaporites [

10], these three deposit types have received the greatest scientific and technological attention due to their more advanced state of research and development. They host strategic metals such as manganese, nickel, copper, cobalt, titanium, molybdenum, and rare earth elements, among others. In some cases, reported concentrations are significantly higher than those typically found in terrestrial deposits, making them resources of high economic interest, particularly in the context of the transition toward clean technologies [

3,

11].

In this context, while access to natural resources in the deep ocean represents a strategic opportunity in both financial terms and supply security, it also raises substantial challenges for achieving sustainability objectives. Key concerns relate to uncertainty regarding DSM’s potential risks to marine ecosystems and its possible social and economic effects. The literature shows recent progress; however, evidence remains nascent or fragmented in several critical areas, particularly with respect to cumulative impacts, spatial and temporal scaling, and long-term socio-economic assessments, supporting the need for broader, more structured analyses that integrate the available evidence on the impacts and opportunities associated with these activities.

However, the existing literature has largely concentrated on two main strands: on the one hand, detailed reviews of DSM’s environmental impacts and, on the other, more narrowly scoped analyses of its economic, governance, or socio-economic implications. Studies addressing social impacts have been comparatively scarce, and socio-economic approaches overall represent a minor fraction of the available corpus. As a result, explicit articulation of the three classical dimensions of sustainability within a single analytical framework remains limited [

12].

This article seeks to help address this gap through a critical and systematic review of the main mineral resources found on the seafloor, with an emphasis on polymetallic nodules, ferromanganese crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides. Building on this basis, we examine the impacts and opportunities associated with DSM across its three dimensions: environmental, social, and economic. We propose a systematic classification of environmental impacts, structured to more clearly capture the disturbances generated in deep-marine ecosystems. Finally, we discuss the main knowledge gaps identified in the literature, with the aim of guiding future research toward interdisciplinary approaches capable of rigorously and interactively addressing the complexity of DSM-related impacts and advancing an informed understanding of the opportunities and challenges posed by this emerging activity.

2. Marines Resources of Interest

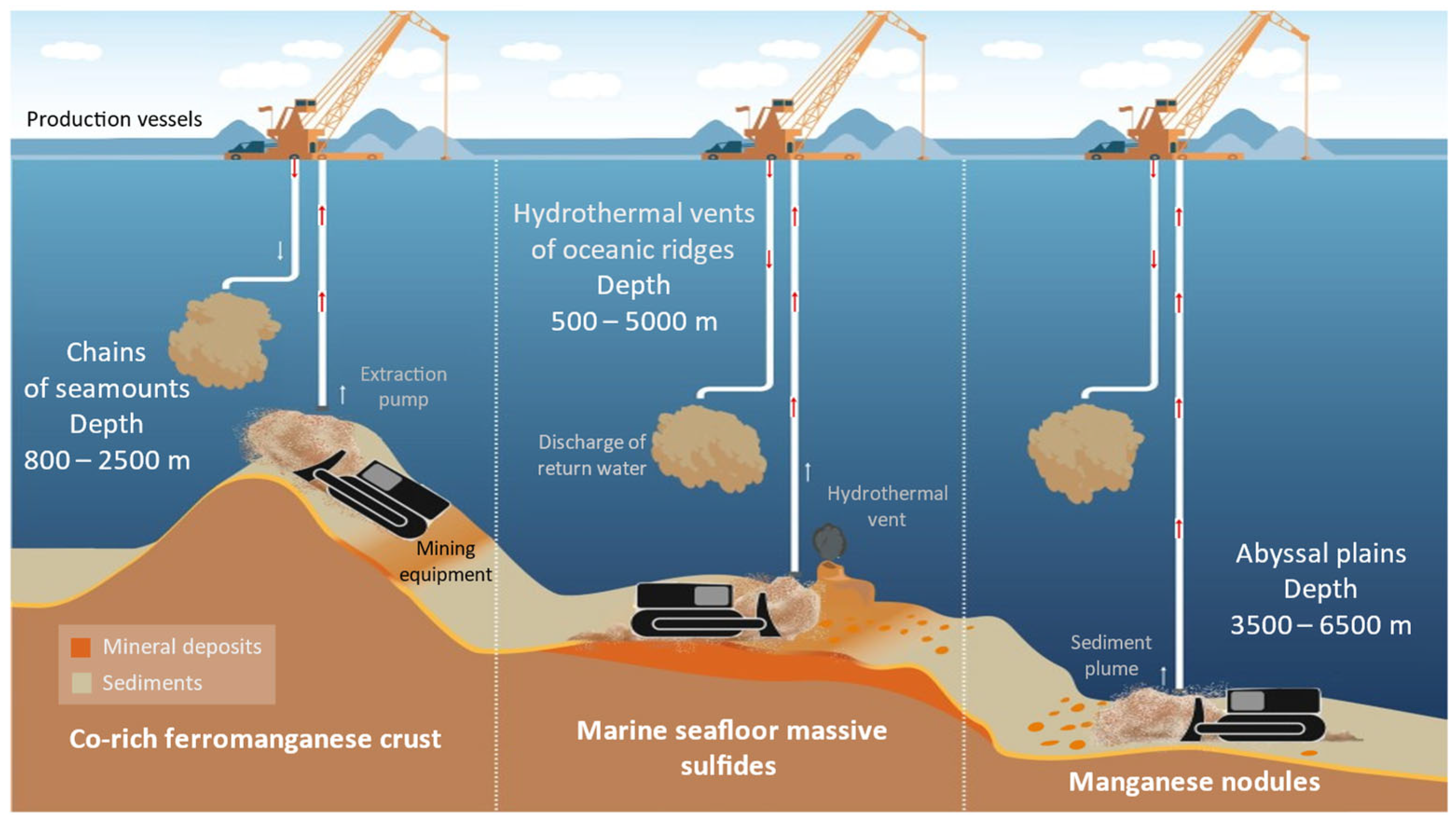

From an operational perspective, DSM involves removing material from the seafloor using specialized equipment and transporting it to a production vessel via a lifting system. In practice, exploration efforts and technological development have focused mainly on three deposit types: polymetallic nodules, seafloor massive sulfides (SMS), and ferromanganese crusts. Because these resources occur in distinct environments and depth ranges, their geological characteristics directly shape equipment design, logistics, and the potential pathways of interaction with the surrounding environment.

Figure 2 summarizes the location and depth ranges of these deposits. The main characteristics of each deposit type are presented below.

2.1. Polymetallic Nodules

Polymetallic nodules occur scattered across abyssal plains or partly buried within the upper ~10 cm of sediments, at water depths ranging from 3500 to 6500 m [

13]. They form around a hardened nucleus of mineral or biogenic origin, onto which concentric layers of metallic oxides and hydroxides are progressively deposited, giving them their characteristic rounded morphology [

3]. Nodule size typically ranges from 1 to 12 cm in diameter, with nodules between 5 and 10 cm being the most common [

14]. Growth rates are extremely slow, with estimates on the order of 2–5 mm per million years [

9,

15,

16].

Their composition is diverse, with manganese and nickel (together with cobalt and copper) standing out as the main elements of economic interest due to their industrial and technological applications; iron may also be present but is typically not an economic target. Significant amounts of copper, cobalt, molybdenum, titanium, and rare earth elements are also present [

3,

17]. A conservative estimate suggests that the Clarion–Clipperton Zone (CCZ), located in the eastern Pacific between Mexico and Hawai‘i, contains approximately 21.1 billion dry metric tonnes, including nearly 6.0 billion tonnes of manganese, 270 million tonnes of nickel, 234 million tonnes of copper, and 46 million tonnes of cobalt. These figures exceed the total known terrestrial reserves [

3,

17]. Currently, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) has issued 19 exploration contracts for polymetallic nodules to member states and international consortia.

2.2. Ferromanganese Crusts

Ferromanganese crusts are hydrogenetic mineral encrustations that form on exposed rocky surfaces of the seafloor through the direct precipitation of metallic oxides and hydroxides from seawater. They occur across a wide depth range, from approximately 400 to 7000 m [

18]. However, crusts located between about 800 and 2500 m are of particular economic interest because they tend to exhibit greater thicknesses and higher concentrations of valuable metals [

19]. Reported thicknesses vary from less than 1 mm to about 260 mm in exceptional cases [

20], and growth rates are extremely slow, on the order of 1–5 mm per million years [

21].

In terms of composition, these crusts are especially enriched in cobalt, manganese, nickel, copper, and titanium, and they also contain strategic elements in lower proportions such as molybdenum, tellurium, platinum, zirconium, niobium, bismuth, and rare earth elements [

19]. It is estimated that the Prime Crust Zone (PCZ) in the Pacific Ocean hosts approximately 7.533 million dry metric tonnes of these deposits, with cobalt and tellurium contents that are roughly four and nine times higher, respectively, than all known terrestrial reserves [

3]. Currently, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) has issued five exploration contracts for ferromanganese crusts, most of them located in the western Pacific, to member states and international consortia.

2.3. Seafloor Massive Sulfides (SMS)

SMS form from hydrothermal circulation in highly dynamic geological settings. They occur as active and inactive vent fields located in seafloor spreading environments, including mid-ocean ridges, volcanic arcs, and other tectonically active regions [

14,

22]. These systems typically develop at depths of approximately 500 to 5000 m and are associated with high-temperature hydrothermal fluids, which can exceed 400 °C at active vents [

23].

SMS deposits display substantial variability in size, ranging from small accumulations of only a few tonnes to large systems that may reach up to 420 million tonnes. Hydrothermal structures such as chimneys can grow up to 45 m in height [

2,

24]. Unlike hydrogenetic marine deposits, SMS exhibit considerably faster and more dynamic growth. This is because hydrothermal chimneys and edifices form through the sustained, direct precipitation of metal sulfides from high-temperature hydrothermal fluids, allowing structures several meters tall to accumulate over geologically short periods [

23,

25].

In terms of composition, SMS deposits contain economically relevant concentrations of industrial metals such as copper, zinc, and lead, as well as significant amounts of precious metals including gold and silver [

3,

11,

26]. Iron-bearing minerals may be present, but iron is not typically considered a primary economic target. The total accumulation of SMS in neovolcanic zones has been estimated at approximately 600 million metric tonnes [

2]. Currently, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) has issued seven exploration contracts for seafloor massive sulfides, mainly distributed across Mid-Atlantic Ridge settings and regions of the Indian Ocean, to member states and international consortia.

3. Impacts Associated with DSM

This section provides an integrated overview of the impacts associated with DSM, systematically addressing the three main dimensions through which this activity may affect marine ecosystems and human communities. While environmental, social, and economic aspects are all examined, particular emphasis is placed on environmental impacts due to their magnitude, persistence, and relevance to the stability of deep-sea ecosystems. To this end, the section presents a structured breakdown and classification of the different types of disturbances identified in the literature, with the aim of improving understanding of the processes involved and their potential cumulative effects. The social and economic dimensions are discussed subsequently, allowing the impacts of deep-sea mining to be situated within a broad analytical framework that recognizes that, despite technological progress, significant uncertainties remain regarding the future consequences of intervening in the ocean floor.

3.1. Environmental Impacts

DSM has emerged as an activity of growing concern due to the potential disturbances it may cause to deep-ocean ecosystems [

5,

16,

27]. Exploiting these resources entails intervening in ecosystems that have remained largely undisturbed for millennia and that are still poorly understood, largely because access to the deep seafloor and subseafloor is technically challenging. This combination of ecosystem vulnerability and scientific uncertainty makes DSM-related processes particularly challenging [

9,

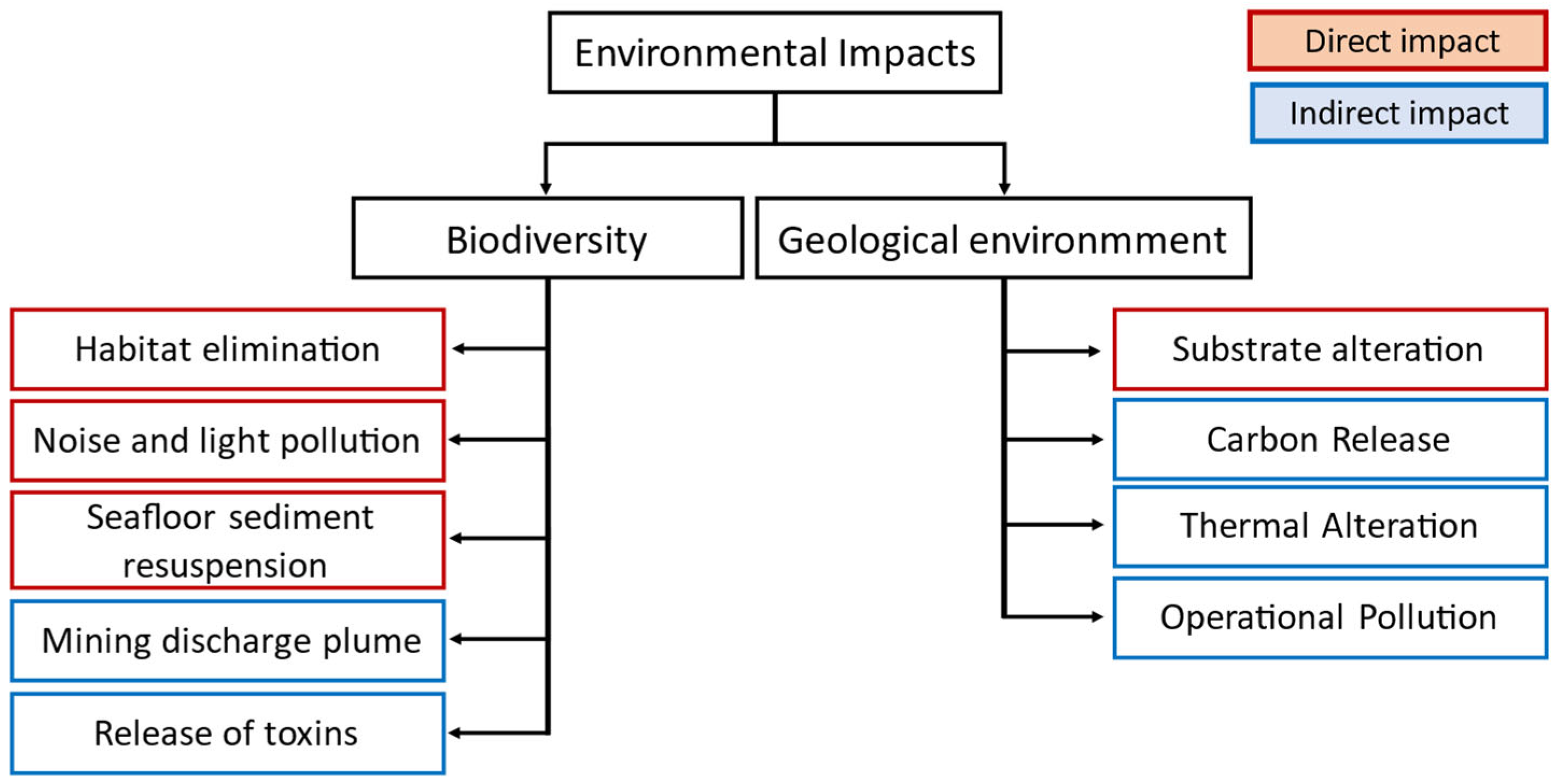

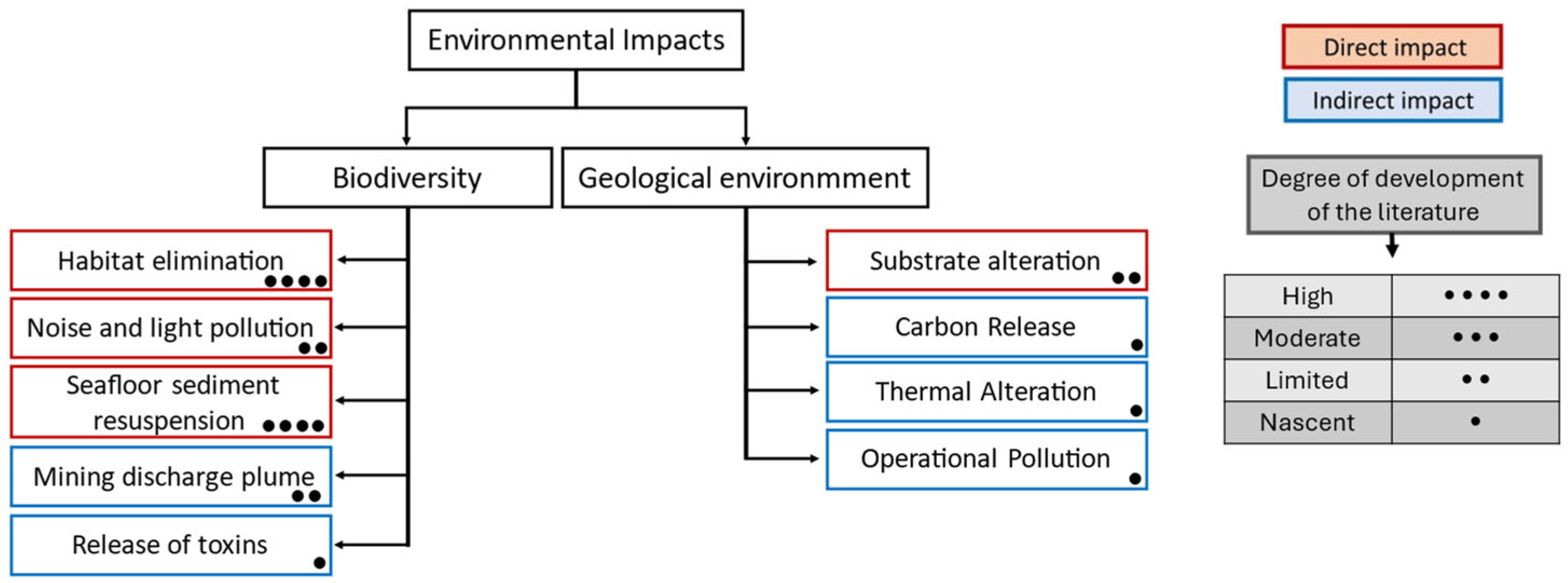

27]. Based on the literature review conducted in this study, the main environmental impacts can be identified and organized into two broad groups: those that directly affect biodiversity and those that compromise the geological environment of the seafloor, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

3.1.1. Impacts of Biodiversity

Habitat Elimination

The extraction of polymetallic nodules represents one of the most evident direct impacts of DSM, as it entails the removal of the surficial sediment layer that supports benthic communities. Experimental and observational studies indicate that this disturbance can reach depths of approximately 10–15 cm [

28]. This process can eliminate between 95% and 100% of the organisms inhabiting the upper 5–10 cm of the seafloor [

29,

30], a zone that is critical to the ecological integrity of abyssal environments. Deep-sea fauna characterized by long life cycles, slow growth, and limited recolonization capacity, is therefore particularly vulnerable to these disturbances [

31,

32].

In the Clarion–Clipperton Zone (CCZ), where economic interest in polymetallic nodules is highest, several studies have shown that the structure and composition of benthic communities can vary substantially even across depth differences of less than 1000 m [

30], highlighting the pronounced heterogeneity and sensitivity of these ecosystems. Because both nodules and sediment layers require thousands to millions of years to form, their removal results in long-lasting alterations for which natural recovery is highly uncertain [

9,

16]. Additional research in the CCZ indicates that both experimental disturbances and track marks left by trawling activities more than three decades ago still exhibit a persistent absence of epifauna, suggesting that regeneration processes in these settings are exceptionally slow [

33].

The extraction of ferromanganese crusts involves the direct removal of consolidated material attached to rocky outcrops, typically using mechanical or hydraulic equipment designed to cut, fracture, or detach the crust [

34,

35]. These operations, commonly carried out at depths between 800 and 2500 m, may negatively affect the high faunal diversity characteristic of seamounts [

36,

37]. Seamounts host fish, invertebrates, and some marine mammals that can be particularly sensitive to disturbance [

38,

39]. Available evidence indicates that these ecosystems have low productivity rates and limited recovery potential [

40]. Studies of analogous impacts, such as those caused by bottom trawling on seamounts in New Zealand and Australia, have shown that ecological recovery can be minimal or even absent more than a decade after disturbance has ceased [

31].

For SMS deposits, extraction uses machinery similar to that employed in open-pit mining, resulting in the direct removal of hydrothermal structures and sulfide deposits [

41]. This process leads to the immediate destruction of habitat and a reduction in biological diversity across multiple trophic levels [

41,

42,

43]. While active hydrothermal vents may exhibit some recovery capacity due to the dynamic nature of hydrothermal flow, inactive vents remain poorly studied, which increases uncertainty regarding their resilience and vulnerability [

44,

45]. Nevertheless, even in active systems, mining intervention may introduce disturbances that exceed natural ranges of variability, thereby increasing the risk of cumulative and long-lasting effects [

41].

Noise and Light Pollution

DSM operations on the seafloor, which rely on specialized vehicles and equipment, generate noise and artificial lighting that can alter the behavior of fish and invertebrates and may even damage photoreceptors in sensitive species [

42]. Noise produced by pumps, cutters, and hydraulic systems can propagate over long distances, facilitated by the high speed of sound in seawater, typically on the order of 1450–1550 m/s depending on oceanographic conditions. Such propagation can interfere with key processes such as communication, orientation, and feeding behavior in fish and invertebrates, as well as in marine mammals that fall within the vertical range of acoustic transmission [

42,

46].

For ferromanganese crust and SMS mining, acoustic impacts may be even more pronounced because these operations use specialized machinery to cut, crush, and fracture rocky substrates at comparatively shallower depths. These activities can increase the generation of noise and vibrations transmitted through the water column, with potential effects on mobile fauna, including fish and other sensitive organisms [

47].

Light pollution represents a second major concern, particularly in deep environments where the absence of natural light is a defining ecological feature [

40]. Exposure to intense artificial lighting can disrupt behavior, induce visual stress, and interfere with physiological processes in organisms adapted to permanent darkness. Recent evidence shows that a range of species, including deep-sea crustaceans and fishes, exhibit avoidance responses and significant behavioral changes when exposed to artificial light, even at red wavelengths that were traditionally considered less intrusive [

48,

49].

In the case of Solwara 1, operational plans envisaged continuous, 24 h operation of seafloor machinery and surface vessels, implying sustained ecosystem exposure to both light and noise. Although recent studies document behavioral responses to artificial lighting and potential effects of noise on marine fauna, the assessment of cumulative and long-term impacts under continuous operating scenarios remains subject to substantial uncertainty [

47,

48,

50].

Seafloor Sediment Resuspension

The operation of collector vehicles used to extract polymetallic nodules generates sediment plumes that can disperse widely through the water column, indirectly affecting environmental quality and associated biota [

51]. Sediments in these abyssal plains are typically composed of mixtures of fine sand, silt, clay, and gravel fragments, although highly clay-rich facies dominate in many areas [

52,

53]. In these settings, the smallest particles, particularly within clayey seafloor sediments where nodules occur, can remain suspended for prolonged periods due to their low settling velocities [

54].

Plumes generated by resuspension may extend tens to even more than one hundred kilometers from the disturbance source, affecting areas adjacent to the mined site and leading to substantial deposition over previously undisturbed habitats [

55]. Fine particles resuspended during extraction, particularly those on the order of ~10 µm, have extremely low settling velocities and can remain in suspension for extended periods. Hydrodynamic modelling studies indicate that their deposition may take several months, and in some cases more than a year, while deep currents transport them kilometers away from the disturbance point [

55]. Because abyssal-plain organisms are adapted to very low turbidity, extremely slow sedimentation rates, and limited food availability [

30], increases in sediment loads can have severe effects on these communities. Such effects may include reduced biological productivity, interference with feeding processes, and, in extreme cases, smothering or burial of benthic filter-feeding organisms as fine-sediment deposition increases [

56,

57].

In contrast, ferromanganese crust mining occurs mainly on hard substrates with little sediment cover [

20]. Although the process involves crushing rock and removing fragmented material, for both crusts and SMS deposits, sediment plumes are expected to be more localized, and the resulting particles, being denser, are likely to settle more rapidly than those in clay-rich environments [

58]. Nevertheless, the extent of dispersion depends strongly on equipment design and the application of good operational practices, which could partially mitigate the spatial reach of these impacts.

Mining Discharge Plume

In addition to the resuspension generated at the seafloor, another relevant impact arises from the discharge to the ocean of the wastewater used during mineral processing and separation. This return flow, comprising process water, fine sediments, and non-economic particles, is commonly reintroduced into the water column through deep discharge systems, at operational depths that typically range between 1000 and 1500 m depending on the design of each operation [

29]. The release of these effluents generates a secondary plume whose dynamics may differ substantially from those of the benthic plume, increasing turbidity and potentially affecting biological processes that depend on water clarity.

The dispersion of this plume depends on the discharge depth, water-column stratification, and local current regimes. Hydrodynamic simulation studies indicate that fine sediments released at intermediate depths can remain in suspension for prolonged periods and be transported tens to hundreds of kilometers, extending impacts beyond the area of direct extraction [

59]. Other studies have emphasized that reinjection depth is one of the most critical factors in the environmental design of these operations, as it determines whether discharged material interacts with mesopelagic, epipelagic, or abyssal fauna, thereby shaping both the magnitude and the spatial distribution of impacts [

51,

60].

Filter-feeding organisms and vulnerable benthic communities, including deep-sea corals, many of which exhibit longevities exceeding 2000 years and extremely slow growth rates of approximately 5 µm/year [

61,

62], may experience polyp clogging, reduced respiration, or even mortality due to the accumulation of particles associated with these residual plumes [

63,

64]. Likewise, sustained deposition of fine sediments can smother previously undisturbed habitats, reduce food availability for filter-feeding fauna, and interfere with key trophic behaviors, generating ecological effects that may extend to regional scales.

Release of Toxins

The removal and disturbance of sediments during DSM extraction operations can trigger the release of metals and potentially toxic compounds into the water column, although comprehensive studies are still needed to fully understand the magnitude of this process and its associated impact pathways. In the case of SMS deposits, particularly at active hydrothermal vents, the release of dissolved and particulate metal species has been documented, including copper, copper–mineral complexes, and associated organometallic forms [

65].

At elevated concentrations, these metals may exert toxic effects, the severity of which depends on both their chemical speciation and the biological sensitivity of the exposed species [

66]. Copper, for example, is widely recognized as one of the most toxic metals to marine invertebrates, with acute and chronic effects that can occur even at relatively low concentrations [

67]. At the ecosystem scale, disturbances involving metals and other released agents may alter the structure and functioning of benthic communities in fragile deep-vent ecosystems [

42].

Another relevant aspect is that mechanical removal and fracturing of sulfide-rich deposits can expose new reactive surfaces to seawater. Oxidation of these freshly exposed sulfides may generate acidified microenvironments and promote the secondary mobilization of trace metals, thereby intensifying the release of potentially toxic compounds following mining activity [

68].

Overall, these processes suggest that the release of metals and associated toxins during the extraction of SMS and other seafloor resources represents a significant environmental risk. Robust assessment will require a deeper understanding of post-disturbance geochemistry, dispersal mechanisms, and the sensitivity of exposed organisms.

3.1.2. Impacts of Geological Environment

Substrate Alteration

DSM entails direct physical alteration of the benthic substrate, as the removal and displacement of mineral deposits and associated sediments modify the composition, structure, and stability of the seafloor. Consequently, extracting seabed resources involves the loss of hard substrates and the homogenization of seabed relief, reducing structural complexity and seafloor roughness [

5,

47,

57,

69].

In the case of polymetallic nodule mining, both the surficial sediment layer and the concretions that provide physical heterogeneity to the seafloor are removed. In the CCZ, nodule distribution and density have been shown to control substrate structure, producing rougher and more stable surfaces than in nodule-poor areas [

70,

71]. Likewise, seafloor disturbance studies indicate that substrate alteration can persist for decades, with physical tracks still visible and sediments more compacted and homogenized compared with undisturbed areas [

33]. Complementarily, recent experiments suggest that once hard substrate is removed, recovery of the original physical structure of the seafloor is extremely slow, evidencing a prolonged alteration of the substrate that far exceeds the timescales of biological recovery [

72].

On seamounts hosting ferromanganese crusts, substrate alteration occurs primarily through mechanical stripping (spalling) of the mineralized rock. This process directly removes consolidated hard surfaces and reduces the geomorphological complexity of the relief, generating smoother surfaces depleted in physical microhabitats [

5,

57].

For seafloor massive sulfide (SMS) deposits, mining targets the hydrothermal chimneys and mounds that constitute the structural substrate of the vent system. Extraction by cutting and suction implies near-complete dismantling of these structures, replacing them with flattened surfaces and compacted sediments [

5,

41]. Because many vent-associated species are tightly linked to chimney systems and the associated physicochemical gradients, the loss of these structures results in an almost complete reduction in available substrate, compromising the physical integrity of the habitat [

47,

69].

Carbon Release

Deep-sea sediments constitute one of the planet’s largest carbon reservoirs and play a key role in ocean biogeochemical cycles and climate regulation [

73,

74]. At the global scale, marine sediments store an amount of organic carbon even greater than that in terrestrial soils, approximately 1.75 times more, and a fraction of this carbon can remain buried for thousands to millions of years if undisturbed, acting as a very long-term CO

2 sink [

73]. In abyssal plains such as the CCZ, organic carbon content in surface sediments is relatively low in percentage terms; however, the vast areal extent of these ecosystems makes the total stock significant in the context of the global carbon cycle [

75].

The dynamics of this carbon store depend largely on benthic organisms that rework the sediment, mixing particles and organic matter within the surficial layers through a process known as bioturbation. In the CCZ, a recent study indicates that this mixing extends on the order of several tens of centimeters in depth, with higher intensity than that observed in other abyssal regions, implying substantial vertical redistribution of carbon stored in the upper centimeters of the sediment [

76].

Seafloor disturbance experiments indicate that impacts on carbon cycling can persist for decades. In the DISCOL experiment in the Peru Basin, measurements taken 26 years after the intervention show that carbon fluxes associated with benthic fauna and respiration remain depressed, and that microbial activity may be locally reduced by up to a factor of four, with 30%–50% declines in cell abundance in impacted areas. These findings further suggest that microbially mediated biogeochemical functions could require more than 50 years to recover to near-reference levels [

28,

77].

At the deposit-type level, the mechanisms underlying carbon mobilization differ. For polymetallic nodules, mechanical removal by collectors and vehicle traffic produces widespread disturbance of the water–sediment interface. A recent assessment by [

78] Planet Tracker (2023), based on estimates of carbon disturbance caused by collector vehicles and on carbon burial rates in CCZ sediments, suggests that the amount of seafloor carbon mobilized annually per square kilometer mined could be several orders of magnitude greater than the carbon naturally buried within the same area, illustrating a pronounced imbalance between anthropogenic disturbance and natural carbon sequestration [

78].

For ferromanganese crusts and SMS deposits, the fine-sediment layer is typically thinner than on abyssal plains, but these deposits occur mainly on seamounts, ridge flanks, and hydrothermal fields, where organic and chemoautotrophic production, together with strong chemical gradients, play a central role in coupling the water column and the seafloor. Exploitation of these deposits may therefore alter carbon fixation by chemoautotrophic communities, organic matter degradation, and carbon fluxes mediated by microbial ecosystem services associated with these substrates [

69,

79].

Thermal Alteration

Deep-sea environments are characterized by cold, highly stable waters, with very limited thermal variability over time. This stability has shaped the adaptation of deep benthic and pelagic communities, which often exhibit narrow tolerance to abrupt physical changes and high sensitivity to external disturbances [

80,

81]. In this context, thermal alterations associated with DSM represent an additional pressure on ecosystems that are already intrinsically vulnerable [

47,

82].

During the exploitation of polymetallic nodules and ferromanganese crusts, the ore is transported to the surface mixed with deep water through the riser (lifting) system. Once onboard, the slurry is dewatered and the residual process water is subsequently discharged back to the ocean [

81]. Multiple studies show that this return water can have appreciable temperature differences relative to the receiving environment, thereby altering its density, buoyancy, and dispersal pathway [

82,

83,

84]. In deep-sea tailings discharge scenarios, significant thermal contrasts have been documented, for instance, discharge temperatures of around 7 °C released into abyssal environments of 1–2 °C, creating conditions that strongly influence plume dispersion and mixing with the surrounding waters [

85]. In addition, risk assessments widely recognize changes in seawater temperature due to the discharge of process return water as one of the key physical impacts of DSM [

86].

For SMS deposits, thermal dynamics become even more complex due to gradients associated with hydrothermal activity. Hydrodynamic models applied to SMS mining scenarios show that both the plumes generated by seafloor equipment and the process-water return plume depend strongly on water-column stratification, which is controlled by temperature and salinity profiles [

87,

88]. In these models, the discharge temperature results from mixing between deep water and surface water used by the lifting system, introducing increases on the order of ~1 °C relative to bottom water, differences that can be sufficient to modify plume stability and its interaction with the surrounding environment [

87].

Finally, studies on the physical impacts of deep-sea mining converge in indicating that even slight but persistent temperature increases may cause severe physiological effects in organisms adapted to extremely constant thermal regimes, including impaired biological performance and potential mortality in pelagic and benthopelagic fauna exposed to warmer-than-normal waters [

80].

Operational Pollution

Mechanical failures or malfunctions in the equipment used for DSM extraction, whether in seafloor vehicles, pumping systems, or support vessels, can lead to the accidental release of chemical substances, primarily hydrocarbons, lubricants, and hydraulic fluids. Recent risk assessments related to deep-sea mining anticipate that, in addition to physical impacts on the seabed, DSM will create further pressures associated with leaks, spills, and the discharge of process waters carrying high contaminant loads [

82].

Although commercial DSM operations do not yet exist, evidence from spills and emissions in other offshore industries provides a plausible analogue for potential consequences. Comparable impacts have been documented in deep-water oil and gas operations, where the release of drilling muds and other hydrocarbon- and synthetic-rich operational fluids has caused sediment contamination and significant alterations in benthic fauna [

30]. Likewise, studies in deep-sea environments affected by hydrocarbons have shown that deposition of these compounds on the seafloor results in marked increases in contaminant concentrations in sediments, accompanied by reductions in benthic macrofaunal diversity and shifts in community composition, with very slow recovery trajectories [

89,

90].

From an ecotoxicological perspective, petroleum hydrocarbons, particularly polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are well known to cause sublethal and lethal effects across a wide range of marine organisms, affecting growth, reproduction, behavior, and survival even at relatively low concentrations [

91].

3.2. Social Impacts

DSM has social implications that have received less systematic attention than environmental impacts, yet they are critical for assessing the legitimacy of how this emerging extractive sector could affect societies and communities. Recent scholarship indicates that, despite the growing body of work on ecological impacts and governance, analyses focused on social justice, participation, and benefit-sharing remain comparatively scarce and fragmented [

92,

93,

94,

95].

At the global level, Jaeckel et al. [

94] argue that DSM currently lacks social legitimacy. Among other points, they note that major brands have rejected the use of minerals sourced from DSM and that various States and organizations have called for a moratorium or precautionary pause, reflecting the absence of broad societal support. Regarding livelihoods, the same study emphasizes that seabed mining impacts may accumulate with other environmental pressures, such as climate change and overfishing, potentially affecting populations that already critically depend on pelagic fisheries. In particular, they highlight the vulnerability of tuna fisheries that spatially overlap with areas of interest for DSM and that contribute a substantial share of GDP, employment, and food security in small Pacific Island States. The study also warns that the rights to food, health, and culture of Indigenous peoples and sea-dependent communities may be undermined by marine ecosystem degradation, contamination associated with sediment or metal plumes, and the loss of spaces used for traditional practices.

Complementarily, Carver et al. [

93] provide a critical analysis showing that DSM is closely intertwined with coastal and terrestrial politics, such that decisions taken offshore can reconfigure who has voice and power in coastal territories, thereby expanding or constraining the margins of social exclusion and shaping conflicts at local, national, and global scales.

Experiences in Papua New Guinea clearly illustrate the potential for social conflict associated with this activity. Drawing on the Solwara 1 case, several studies show how the absence of social acceptance, coupled with the legacy of terrestrial mining disasters, fueled distrust in DSM and contributed to the project’s collapse. Childs [

96] documents how Nautilus sought to legitimize the operation by emphasizing the alleged remoteness of the deposit from human communities and portraying DSM as a more sustainable alternative to land-based mining, while downplaying concerns raised by local communities and organizations. Meanwhile, Van Putten et al. [

97] show that the evolution of media discourses reflects a progressive deterioration of social acceptance, characterized by power imbalances, a lack of transparent information, conflicts over marine tenure rights, and perceptions that environmental and social risks fall disproportionately on local communities.

From a socio-economic assessment perspective, Wakefield and Myers [

98] show, through social cost–benefit analyses for different hypothetical scenarios in the Pacific, that potential fiscal benefits of DSM for host States coexist with substantial uncertainty regarding environmental and cultural costs borne by communities that do not necessarily participate in decision-making. Similar concerns are raised by Carver et al. [

93] and Oztig [

92], who argue that how risks and benefits are distributed among sponsoring States, transnational corporations, and local communities remains an unresolved social justice issue and could deepen inequalities unless clear mechanisms are established to ensure equitable benefit-sharing.

3.3. Economic Impacts

Interest in DSM has been driven, on the one hand, by growing tensions over the supply of critical minerals for the energy transition and, on the other, by the prospect of adding a new source of global supply. However, compared with the rapid expansion of the literature on environmental impacts, studies that systematically address economic implications remain scarce. Lèbre et al. [

99] note that, relative to the abundant scholarship on ecological and governance impacts, assessing how DSM could affect land-based mining and global metal markets remains a major research gap.

At the project scale, the limited techno-economic analyses available focus almost exclusively on polymetallic nodule mining and suggest that it could be commercially viable under certain assumptions, albeit with substantial uncertainty. Van Nijen et al. [

100] present the first integrated stochastic assessment of a polymetallic nodule mining business in the CCZ, showing that, assuming real price growth and a relatively low payment regime (i.e., 2%–4% from a total-cost perspective), internal rates of return above 18% may be achievable, competitive with land-based mines. Complementarily, Abramowski et al. [

101] provides an updated economic evaluation for the Interoceanmetal project and shows that some scenarios may be more favorable than others. In particular, he indicates that the most promising outcomes arise when considering high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) as well as the option of selling raw ore. However, he emphasizes that many of the cost assumptions used in these analyses still need to be validated through pilot testing; therefore, these estimates should be interpreted cautiously as approximations that remain sensitive to metal price volatility.

From a macroeconomic and market perspective, emerging evidence points to potential benefits but also to significant distributional risks. Wang et al. [

102] synthesize that polymetallic nodules, ferromanganese crusts, and SMS deposits contain relevant quantities of critical minerals for energy technologies, and that several economic assessments indicate commercial potential in certain deep-ocean regions. At the same time, the authors stress that the emergence of DSM could alter supply, intensify competition in mineral markets, and increase price volatility, and they recommend that land-based producers develop adaptation and risk-management strategies.

The work of Lèbre et al. [

99] provides one of the first systematic analyses of how a new metal flow from DSM could affect land-based mining for four key battery metals (cobalt, copper, manganese, and nickel). By assessing 2449 projects, the authors show that large volumes of seabed supply could reduce the profitability of high-cost terrestrial operations, with particular vulnerability in economies that are highly dependent on mining. The study concludes that DSM has the potential to generate serious adverse effects in mining-dependent countries, including premature mine closures, projects moving into care and maintenance, or divestment, processes that often externalize environmental and social risks onto local communities.

International organizations also underscore the magnitude of economic uncertainties. The report Precautionary Management of Deep Sea Minerals (2017) emphasizes that only a very limited number of prospects have reached advanced feasibility stages and that fiscal regimes, total regulatory compliance costs, and the full economic impact of DSM remain “unproven,” making it difficult to estimate net benefits for host countries with precision [

103].

4. Discussion

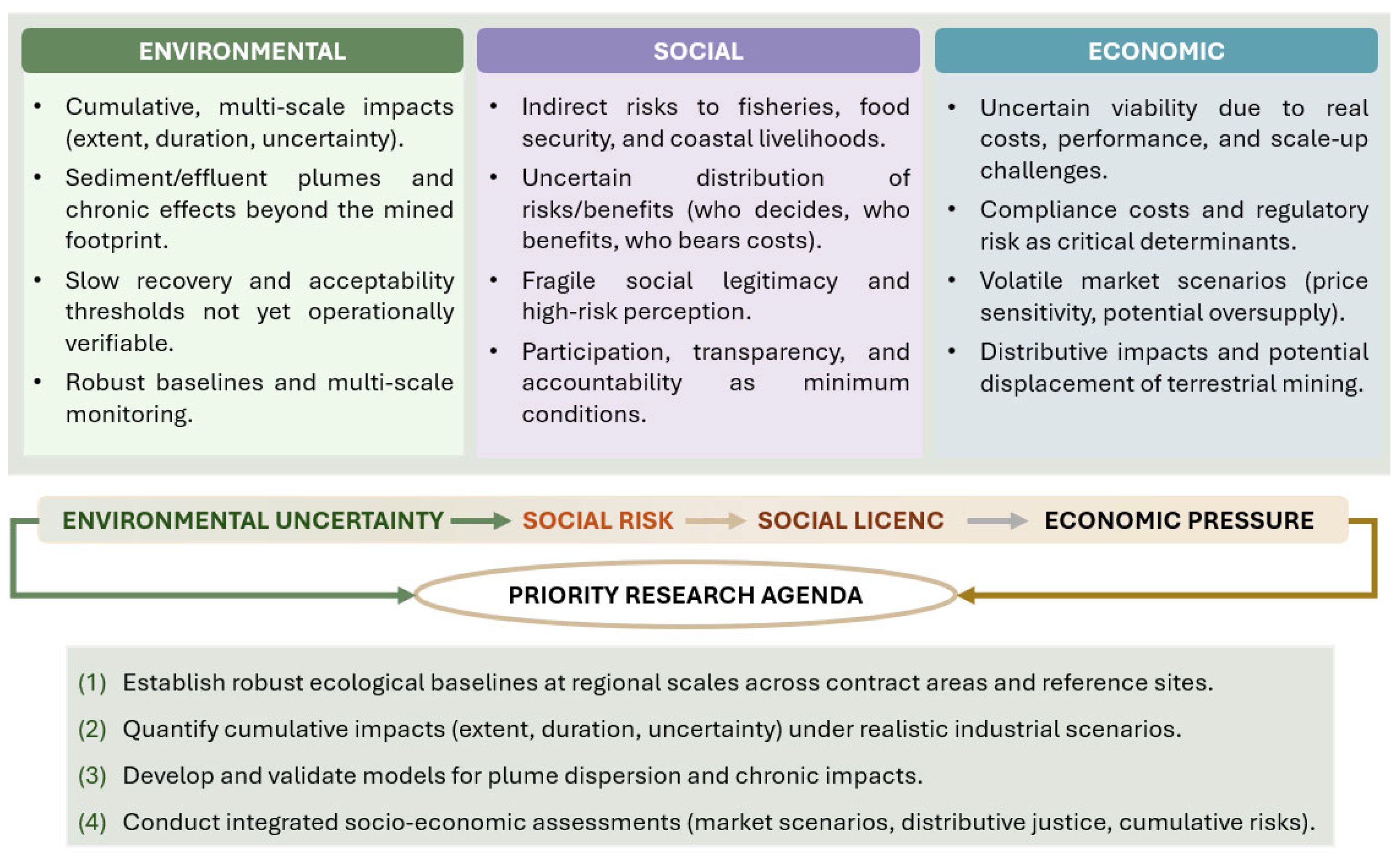

DSM is increasingly framed as an emerging response to global tensions in the supply of critical minerals, particularly in a context of energy transition and accelerating technological growth. However, the findings of this review show that the debate on its viability cannot be reduced to a false opposition between resource necessity and technological opportunity. Rather, the evidence suggests that DSM is a paradigmatic case in which ecological uncertainty, fragile social legitimacy, and economic ambiguity are intertwined, requiring the activity to be assessed under an integrative sustainability framework. Within this framework,

Figure 4 synthesizes the central axes that structure the discussion, environmental, social, and economic impacts, and the cross-cutting role of governance, while also highlighting the links between environmental uncertainty, social risk, and legitimacy, as well as the resulting research priorities.

4.1. Environmental Dimension

The main warning signal identified in the literature is the mismatch between the potential scale of intervention and the current capacity to understand and monitor abyssal ecosystems. Physical removal of substrates, loss of structural habitats, and disruption of biogeochemical functioning could produce long-lasting impacts, particularly in systems where biological and geological growth rates are extremely slow. Beyond the identification of discrete impacts, critical uncertainties persist regarding the intensity and severity of disturbances, their duration, the sensitivity and vulnerability of abyssal ecosystems, and their capacity for recovery. This combination of knowledge gaps reinforces the need to adopt a precautionary and adaptive approach to DSM, grounded in progressive performance standards, robust baselines, and multiscale monitoring.

A critical point is that much of the evidence discussed to date comes primarily from experimental and observational studies or from exploration-stage activities. This raises an additional concern: if the environmental footprint is already significant at early stages, industrial-scale operations could amplify these effects in intensity, duration, and spatial extent. Under this logic, the environmental discussion should focus not only on identifying impacts, but also on the real capacity to prevent cumulative effects and to establish operationally verifiable thresholds.

In line with the above,

Figure 5 synthesizes the main environmental impacts associated with DSM and complements the previous framework by incorporating, for each mechanism, the degree of development of the literature as assessed in this study. While there is a relatively substantial body of environmental research, the evidence base is not uniform. Processes such as habitat loss, sediment resuspension, and substrate alteration are more mature, whereas others remain comparatively nascent or fragmented. This asymmetry further supports the need for a precautionary and adaptive approach, underpinned by robust baselines, multiscale monitoring, and the definition of operationally verifiable thresholds, particularly to prevent cumulative effects at industrial scales.

4.2. Social Dimension

Social debate around DSM has progressed more slowly than the environmental debate, yet its relevance is indisputable for assessing the real-world viability of this activity. In a global context where traceability, reputational pressure, and ESG standards [

104] are reshaping supply chains, the lack of social acceptance represents a material risk for any future project. Recent literature argues that DSM still lacks robust social legitimacy, as reflected both in calls for moratoria or precautionary pauses and in the refusal of influential market actors to use minerals sourced from the deep sea.

This dimension becomes particularly complex when considering the international distribution of benefits and risks. In areas beyond national jurisdiction, persistent debates over who decides, who benefits, and who bears environmental externalities remain critical. International governance thus emerges as a cross-cutting pillar to prevent asymmetries among sponsoring States, companies, and coastal communities, especially when potential environmental impacts may translate into indirect socioeconomic effects on fisheries, food security, and cultural values. Available evidence highlights the vulnerability of pelagic fisheries that overlap with areas of DSM interest and that sustain employment, income, and a meaningful share of GDP in small Pacific Island States, in a context where cumulative pressures from climate change and overfishing already threaten resilience. This underscores the need to treat the social dimension not as an add-on, but as a structural criterion for early-stage assessment, closely linked to ecological uncertainty and the architecture of international governance.

Moreover, decisions made offshore can reconfigure power dynamics in coastal territories and widen pathways of social exclusion in the absence of effective participation, transparency, and accountability mechanisms. Early experiences in Papua New Guinea illustrate how narratives of geographic remoteness did not prevent conflict; rather, they contributed to deepening distrust when local communities perceived that environmental and social risks were being downplayed.

An additional, less-discussed social consideration is the potential reconfiguration of global metals markets. DSM could introduce volatility and undermine the profitability of high-cost terrestrial operations, increasing the risk of closures, divestment, and cost-cutting strategies that tend to externalize social impacts onto communities dependent on land-based mining. Consequently, the social acceptance of DSM will depend not only on local perceptions in coastal countries, but also on the geopolitical and socioeconomic tensions that may emerge in traditional mining economies as a new extractive competitor enters the market.

4.3. Economic Dimension

From an economic perspective, the results point to a dual landscape. On the one hand, available techno-economic scenarios suggest that exploiting certain deposits—particularly polymetallic nodules—could be profitable under optimistic assumptions regarding prices, technological performance, and fiscal regimes. On the other hand, the literature consistently notes that many of these estimates rely on variables that have not yet been demonstrated at industrial scale, including actual operating costs, the environmental expenditures associated with regulatory compliance, and financial risks arising from potential future political constraints. Consequently, uncertainty is not confined to technical feasibility; it also extends to the stability of market conditions and to the ability to internalize environmental and governance costs under realistic scenarios.

At the macroeconomic level, DSM could exert meaningful pressures on global metals markets and generate indirect effects in countries reliant on terrestrial mining. In this regard, the economic discussion should not be limited to comparing production costs per tonne, but should also incorporate supply–demand dynamics and transition risks, such as shifts in investment patterns and the potential disincentive for innovation in lower-impact terrestrial mining. In particular, a scenario of accelerated DSM expansion could contribute to a relative oversupply of certain metals, putting downward pressure on international prices and undermining the viability of terrestrial operations with higher marginal costs or more stringent environmental frameworks. This potential displacement effect suggests that economic assessments of DSM should include price-sensitivity analyses, distributive impacts, and strategic consequences for regions whose economic and social stability depends on conventional mining.

5. Conclusions

Despite technical advances and the sustained increase in interest in DSM in recent years, substantial uncertainties remain regarding its short- and long-term consequences. The evidence reviewed suggests that interventions in abyssal ecosystems, characterized by high ecological fragility and slow recovery dynamics, could produce significant impacts both within and beyond the directly disturbed areas, with recovery timescales that may extend over decades. In this context, it is critical to incorporate explicit cumulative-impact assessments that account for the spatial extent, duration, and uncertainty of ecological risk.

The social dimension emerges as an inseparable component of this debate. Geographic remoteness of the deep seafloor does not imply the absence of social impacts, particularly when considering indirect risks to fisheries, food security, and ocean-dependent livelihoods. Social legitimacy for DSM remains fragile, and strengthening it will require transparent governance, effective participation, and distributive-justice frameworks that address who decides, who benefits, and who bears environmental externalities.

In parallel, the economic viability of DSM cannot be assessed solely through optimistic techno-economic assumptions. Regulatory uncertainty, the environmental costs of compliance, and supply–demand scenarios could introduce volatility in metals markets and generate displacement effects on terrestrial operations with higher marginal costs, with social and fiscal consequences for traditional mining economies.

A central cross-cutting contribution of this review is to advance a perspective in which DSM sustainability cannot be evaluated through isolated dimensions. Ecological uncertainty translates into social risk; weak legitimacy constrains economic viability; and economic uncertainty can create pressure to accelerate regulatory decisions before sufficient evidence is available. This dynamic is evident both in the international governance of activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction, where the framework is set by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the ISA, and in national regulatory decisions within exclusive economic zones. Accordingly, the findings support the need for a precautionary approach grounded in progressive performance standards, beginning with robust ecological baselines, multi-scale monitoring plans, and governance mechanisms that enable adaptive adjustments as new evidence emerges.

Notably, the published evidence base remains comparatively limited for the social and economic dimensions of DSM, in contrast to the environmental and technological literature. Accordingly, these dimensions are discussed at a more aggregated level, and we highlight this imbalance as a key research gap and a priority for future research.

Future research should prioritize ecological characterization of contract areas, the development and validation of predictive models for plume dispersion and chronic impacts, and integrated socioeconomic assessments that incorporate market scenarios, distributive justice, and cumulative risks. Only through a robust scientific and regulatory approach will it be possible to evaluate whether DSM can contribute to mineral supply security without compromising biodiversity, social equity, and global economic stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.E.; methodology, F.E.; validation, F.E.; formal analysis, F.E.; investigation, F.E.; resources, F.E.; writing—original draft preparation, F.E.; writing—review and editing, L.F.O. and E.C.; visualization, F.E.; supervision, F.E.; project administration, F.E.; funding acquisition, F.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by ANID CIA250010 of the Advanced Mining Technology Center (AMTC), and the National Doctoral Scholarship ANID, Folio No 21250527.

Data Availability Statement

This study is a literature review and did not generate original data. All analyzed information was obtained from publicly available published sources in scientific databases and editorial repositories.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses sincere gratitude for the institutional and academic support received throughout the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCZ | Clarion–Clipperton Zone |

| DSM | Deep-sea mining |

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| HPAL | High-pressure acid leaching |

| ISA | International Seabed Authority |

| PCZ | Prime Crust Zone |

| ROV | Remotely operated vehicle |

| SMS | Seafloor massive sulfides |

| UNCLOS | United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea |

References

- Beaulieu, S.E.; Graedel, T.E.; Hannington, M.D. Should we mine the deep seafloor? Earths Future 2017, 5, 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannington, M.; Jamieson, J.; Monecke, T.; Petersen, S.; Beaulieu, S. The abundance of seafloor massive sulfide deposits. Geology 2011, 39, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.R.; Mizell, K.; Koschinsky, A.; Conrad, T.A. Deep-ocean mineral deposits as a source of critical metals for high- and green-technology applications: Comparison with land-based resources. Ore Geol. Rev. 2013, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivoda, V. Uncharted depths: Navigating the energy security potential of deep-sea mining. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Thompson, K.F.; Johnston, P.; Santillo, D. An Overview of Seabed Mining Including the Current State of Development, Environmental Impacts, and Knowledge Gaps. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 4, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delivorias, A. Norway to Mine Part of the Arctic Seabed; The Norwegian Parliament: Oslo, Norway, 2024; p. 2. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_ATA(2024)757616 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Jolly, S. Deep Sea Mining in the Norwegian Context: Contradictions and the Emergent Uncertainties Ahead; Nordlandsforskning AS: Bodø, Norway, 2025; p. 31. Available online: https://www.nordlandsforskning.no/en/publikasjoner/report/deep-sea-mining-norwegian-context-contradictions-and-emergent-uncertainties (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Singh, P.A.; Jaeckel, A.; Ardron, J.A. A Pause or Moratorium for Deep Seabed Mining in the Area? The Legal Basis, Potential Pathways, and Possible Policy Implications. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 2025, 56, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollner, S.; Kaiser, S.; Menzel, L.; Jones, D.O.B.; Brown, A.; Mestre, N.C.; Van Oevelen, D.; Menot, L.; Colaço, A.; Canals, M.; et al. Resilience of benthic deep-sea fauna to mining activities. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017, 129, 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, E.; Blasco, I.; Blanco, L.; González, F.J.; Somoza, L.; Medialdea, T. Llega la Era de la Minería Submarina, 2017th ed.; ILUSTRE Colegio Oficial de Geologos: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, S.; Krätschell, A.; Augustin, N.; Jamieson, J.; Hein, J.R.; Hannington, M.D. News from the seabed—Geological characteristics and resource potential of deep-sea mineral resources. Mar. Policy 2016, 70, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espínola, F.; Castillo, E.; Orellana, L.F. Bibliometric and PESTEL Analysis of Deep-Sea Mining: Trends and Challenges for Sustainable Development. Mining 2025, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.R.; Conrad, T.A.; Dunham, R.E. Seamount Characteristics and Mine-Site Model Applied to Exploration- and Mining-Lease-Block Selection for Cobalt-Rich Ferromanganese Crusts. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2009, 27, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, P.P.E.; Billett, D.S.M.; Van Dover, C.L. Environmental Risks of Deep-sea Mining. In Handbook on Marine Environment Protection; Salomon, M., Markus, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbach, P.; Marchig, V.; Scherhag, C. Regional variations in Mn, Ni, Cu, and Co of ferromanganese nodules from a basin in the Southeast Pacific. Mar. Geol. 1980, 38, M1–M9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A.; Mengerink, K.; Gjerde, K.M.; Rowden, A.A.; Van Dover, C.L.; Clark, M.R.; Ramirez-Llodra, E.; Currie, B.; Smith, C.R.; Sato, K.N.; et al. Defining “serious harm” to the marine environment in the context of deep-seabed mining. Mar. Policy 2016, 74, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.R.; Spinardi, F.; Okamoto, N.; Mizell, K.; Thorburn, D.; Tawake, A. Critical metals in manganese nodules from the Cook Islands EEZ, abundances and distributions. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 68, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszak, P.; Collot, J.; Josso, P.; Pelleter, E.; Etienne, S.; Patriat, M.; Cheron, S.; Boissier, A.; Guyomard, Y. Origin and Composition of Ferromanganese Deposits of New Caledonia Exclusive Economic Zone. Minerals 2022, 12, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.R.; Koschinsky, A. Deep-Ocean Ferromanganese Crusts and Nodules. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Beaudoin, Y. Deep Sea Minerals: Cobalt-Rich Ferromanganese Crusts, a Physical, Biological, Environmental, and Technical Review; The Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC): Nouméa, New Caledonia, 2014; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260596852 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Hein, J.R.; Koschinsky, A.; Bau, M.; Manhein, F.; Kang, J.-K.; Roberts, L. Cobalt-Rich Ferromanganese Crusts in the Pacific. In Handbook of Marine Mineral Deposits; Cronan, D.S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; pp. 239–279. [Google Scholar]

- Hannington, M.D.; De Ronde, C.E.J.; Petersen, S. Sea-Floor Tectonics and Submarine Hydrothermal Systems. In One Hundredth Anniversary Volume; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L.; German, C.R.; Speer, K.G.; Parson, L.M.; Vrijenhoek, R.C. Evolution and Biogeography of Deep-Sea Vent and Seep Invertebrates. Science 2002, 295, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, C.R.; Petersen, S.; Hannington, M.D. Hydrothermal exploration of mid-ocean ridges: Where might the largest sulfide deposits be forming? Chem. Geol. 2016, 420, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tivey, M.K. Generation of Seafloor Hydrothermal Vent Fluids and Associated Mineral Deposits. Oceanography 2007, 20, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, P.; Beaulieu, S.; Tivey, M.A.; Eggert, R.G.; German, C.; Glowka, L.; Lin, J. Deep-sea mining of seafloor massive sulfides. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L.; Ardron, J.A.; Escobar, E.; Gianni, M.; Gjerde, K.M.; Jaeckel, A.; Jones, D.O.B.; Levin, L.A.; Niner, H.J.; Pendleton, L.; et al. Biodiversity loss from deep-sea mining. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonnahme, T.R.; Molari, M.; Janssen, F.; Wenzhöfer, F.; Haeckel, M.; Titschack, J.; Boetius, A. Effects of a deep-sea mining experiment on seafloor microbial communities and functions after 26 years. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squillace, M. Best regulatory practices for deep seabed mining: Lessons learned from the U.S. Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. Mar. Policy 2021, 125, 104327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.R.; Levin, L.A.; Koslow, A.; Tyler, P.A.; Glover, A.G. The near future of the deep-sea floor ecosystems. In Aquatic Ecosystems; Polunin, N.V.C., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Schlacher, T.A.; Rowden, A.A.; Althaus, F.; Clark, M.R.; Bowden, D.A.; Stewart, R.; Bax, N.J.; Consalvey, M.; Kloser, R.J. Seamount megabenthic assemblages fail to recover from trawling impacts. Mar. Ecol. 2010, 31, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.R.; Althaus, F.; Schlacher, T.A.; Williams, A.; Bowden, D.A.; Rowden, A.A. The impacts of deep-sea fisheries on benthic communities: A review. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2016, 73, i51–i69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanreusel, A.; Hilario, A.; Ribeiro, P.A.; Menot, L.; Arbizu, P.M. Threatened by mining, polymetallic nodules are required to preserve abyssal epifauna. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Ortiz, A.A.; Robbins, C.S.; Morris, J.A.; Cooley, S.R.; Davies, J.; Leonard, G.H. An initial spatial conflict analysis for potential deep-sea mining of marine minerals in U.S. Federal Waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1213424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Directorate General for Parliamentary Research Services. In Deep-Seabed Exploitation: Tackling Economic, Environmental and Societal Challenges: Study; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2015; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/464059 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Schlacher, T.A.; Baco, A.R.; Rowden, A.A.; O’Hara, T.D.; Clark, M.R.; Kelley, C.; Dower, J.F. Seamount benthos in a cobalt-rich crust region of the central P acific: Conservation challenges for future seabed mining. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.B.; Cairns, S.; Reiswig, H.; Baco, A.R. Benthic megafaunal community structure of cobalt-rich manganese crusts on Necker Ridge. Deep Sea Res. Part Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2015, 104, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranto, G.H.; Kvile, K.Ø.; Pitcher, T.J.; Morato, T. An Ecosystem Evaluation Framework for Global Seamount Conservation and Management. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morato, T.; Hoyle, S.D.; Allain, V.; Nicol, S.J.; Karl, D. Seamounts are hotspots of pelagic biodiversity in the open ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9707–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.R.; Demopoulos, A.W.J. The Deep Pacific Ocean Floor; The National Geographic Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L. Tighten regulations on deep-sea mining. Nature 2011, 470, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L. Impacts of anthropogenic disturbances at deep-sea hydrothermal vent ecosystems: A review. Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 102, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschen, R.E.; Rowden, A.A.; Clark, M.R.; Pallentin, A.; Gardner, J.P.A. Seafloor massive sulfide deposits support unique megafaunal assemblages: Implications for seabed mining and conservation. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 115, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, K.L.; Macko, S.A.; Van Dover, C.L. Evidence for a chemoautotrophically based food web at inactive hydrothermal vents (Manus Basin). Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2009, 56, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A.; Mendoza, G.F.; Konotchick, T.; Lee, R. Macrobenthos community structure and trophic relationships within active and inactive Pacific hydrothermal sediments. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2009, 56, 1632–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kim, H.-W.; Yeu, T.; Choi, J.-S.; Lee, T.H.; Lee, J.-K. Technologies for Safe and Sustainable Mining of Deep-Seabed Minerals. In Environmental Issues of Deep-Sea Mining; Sharma, R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 95–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amon, D.J.; Gollner, S.; Morato, T.; Smith, C.R.; Chen, C.; Christiansen, S.; Currie, B.; Drazen, J.C.; Fukushima, T.; Gianni, M.; et al. Assessment of scientific gaps related to the effective environmental management of deep-seabed mining. Mar. Policy 2022, 138, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffroy, M.; Langbehn, T.; Priou, P.; Varpe, Ø.; Johnsen, G.; Le Bris, A.; Fisher, J.A.D.; Daase, M.; McKee, D.; Cohen, J.; et al. Pelagic organisms avoid white, blue, and red artificial light from scientific instruments. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, S.C. Vision in hydrothermal vent shrimp. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 355, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsopp, M.; Miller, C.; Atkins, R.; Rocliffe, S.; Tabor, I.; Santillo, D.; Johnston, P. Review of the Current State of Development and the Potential for Environmental Impacts of Seabed Mining Operations; Report No.: GRL-TR(R)-03-2013; Greenpeace Research Laboratories: Exeter, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spearman, J.; Taylor, J.; Crossouard, N.; Cooper, A.; Turnbull, M.; Manning, A.; Lee, M.; Murton, B. Measurement and modelling of deep sea sediment plumes and implications for deep sea mining. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.; Kolbusz, J.L.; Bond, T.; Macdonald, C.; Niyazi, Y.; Jamieson, A.J.; Stewart, H.A. Seafloor surficial sediment variability across the abyssal plains of the central and eastern pacific ocean. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1527469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, Z.; Rae, J.W.B.; Berelson, W.M.; Adkins, J.F.; Hou, Y.; Dong, S.; Lampronti, G.I.; Liu, X.; Achterberg, E.P.; Subhas, A.V.; et al. Authigenic Formation of Clay Minerals in the Abyssal North Pacific. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2022, 36, e2021GB007270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Royo, C.; Peacock, T.; Alford, M.H.; Smith, J.A.; Le Boyer, A.; Kulkarni, C.S.; Lermusiaux, P.F.J.; Haley, P.J.; Mirabito, C.; Wang, D.; et al. Extent of impact of deep-sea nodule mining midwater plumes is influenced by sediment loading, turbulence and thresholds. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolinski, S.; Segschneider, J.; Sündermann, J. Long-term propagation of tailings from deep-sea mining under variable conditions by means of numerical simulations. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2001, 48, 3469–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, R.C.; Seiderer, L.J.; Hitchcock, D.R. The Impact of Dredging Works in Coastal Waters: A Review of the Sensitivity to Disturbance and Subsequent Recovery of Biological Resources on the Sea Bed. In Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kaikkonen, L.; Venesjärvi, R.; Nygård, H.; Kuikka, S. Assessing the impacts of seabed mineral extraction in the deep sea and coastal marine environments: Current methods and recommendations for environmental risk assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 135, 1183–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisi, I.; Di Risio, M.; De Girolamo, P.; Gabellini, M. Engineering Tools for the Estimation of Dredging-Induced Sediment Resuspension and Coastal Environmental Management. In Applied Studies of Coastal and Marine Environments; Marghany, M., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segschneider, J.; Sündermann, J. Simulating large scale transport of suspended matter. J. Mar. Syst. 1998, 14, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazen, J.C.; Smith, C.R.; Gjerde, K.M.; Haddock, S.H.D.; Carter, G.S.; Choy, C.A.; Clark, M.R.; Dutrieux, P.; Goetze, E.; Hauton, C.; et al. Midwater ecosystems must be considered when evaluating environmental risks of deep-sea mining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 17455–17460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreiro-Silva, M.; Andrews, A.; Braga-Henriques, A.; De Matos, V.; Porteiro, F.; Santos, R. Variability in growth rates of long-lived black coral Leiopathes sp. from the Azores. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2013, 473, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roark, E.B.; Guilderson, T.P.; Dunbar, R.B.; Fallon, S.J.; Mucciarone, D.A. Extreme longevity in proteinaceous deep-sea corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5204–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.V. A Review of Some Environmental Issues Affecting Marine Mining. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2001, 19, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boschen, R.E.; Rowden, A.A.; Clark, M.R.; Gardner, J.P.A. Mining of deep-sea seafloor massive sulfides: A review of the deposits, their benthic communities, impacts from mining, regulatory frameworks and management strategies. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 84, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, S.G.; Koschinsky, A. Metal flux from hydrothermal vents increased by organic complexation. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemire, J.A.; Harrison, J.J.; Turner, R.J. Antimicrobial activity of metals: Mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisler, R. Copper Hazards to Fish, Wildlife, and Invertebrates; Report No.: USGS/BRD/BSR--1997-0002; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 1998; Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA347472.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Bilenker, L.D.; Romano, G.Y.; McKibben, M.A. Kinetics of sulfide mineral oxidation in seawater: Implications for acid generation during in situ mining of seafloor hydrothermal vent deposits. Appl. Geochem. 2016, 75, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcutt, B.N.; Bradley, J.A.; Brazelton, W.J.; Estes, E.R.; Goordial, J.M.; Huber, J.A.; Jones, R.M.; Mahmoudi, N.; Marlow, J.J.; Murdock, S.; et al. Impacts of deep-sea mining on microbial ecosystem services. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2020, 65, 1489–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amon, D.J.; Ziegler, A.F.; Dahlgren, T.G.; Glover, A.G.; Goineau, A.; Gooday, A.J.; Wiklund, H.; Smith, C.R. Insights into the abundance and diversity of abyssal megafauna in a polymetallic-nodule region in the eastern Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Smet, B.; Pape, E.; Riehl, T.; Bonifácio, P.; Colson, L.; Vanreusel, A. The Community Structure of Deep-Sea Macrofauna Associated with Polymetallic Nodules in the Eastern Part of the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollner, S.; Haeckel, M.; Janssen, F.; Lefaible, N.; Molari, M.; Papadopoulou, S.; Reichart, G.-J.; Trabucho Alexandre, J.; Vink, A.; Vanreusel, A. Restoration experiments in polymetallic nodule areas. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2021, 18, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwood, T.B.; Witt, A.; Mayorga, J.; Hammill, E.; Sala, E. Global Patterns in Marine Sediment Carbon Stocks. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, S.; Diesing, M.; Gies, H.; Haghipour, N.; Narman, L.; Magill, C.; Wagner, T.; Galy, V.V.; Hou, P.; Zhao, M.; et al. Unraveling Environmental Forces Shaping Surface Sediment Geochemical “Isodrapes” in the East Asian Marginal Seas. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2024, 38, e2023GB007839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, J.B.; Haffert, L.; Haeckel, M.; Koschinsky, A.; Kasten, S. Impact of small-scale disturbances on geochemical conditions, biogeochemical processes and element fluxes in surface sediments of the eastern Clarion–Clipperton Zone, Pacific Ocean. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Lin, F.; Lin, L. Bioturbation in sediment cores from the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the northeast Pacific: Evidence from excess 210Pb. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratmann, T.; Lins, L.; Purser, A.; Marcon, Y.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Ravara, A.; Cunha, M.R.; Simon-Lledó, E.; Jones, D.O.B.; Sweetman, A.K.; et al. Abyssal plain faunal carbon flows remain depressed 26 years after a simulated deep-sea mining disturbance. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 4131–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, E.; Mosnier, F. The Climate Myth of Deep Sea Mining; Planet Tracker: London, UK, 2023; p. 26. Available online: https://planet-tracker.org/the-climate-myth-of-deep-sea-mining/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Van Dover, C.L. Inactive Sulfide Ecosystems in the Deep Sea: A Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, B.; Denda, A.; Christiansen, S. Potential effects of deep seabed mining on pelagic and benthopelagic biota. Mar. Policy 2020, 114, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Llodra, E.; Trannum, H.C.; Evenset, A.; Levin, L.A.; Andersson, M.; Finne, T.E.; Hilario, A.; Flem, B.; Christensen, G.; Schaanning, M.; et al. Submarine and deep-sea mine tailing placements: A review of current practices, environmental issues, natural analogs and knowledge gaps in Norway and internationally. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 97, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Tian, C.; Teng, Y.; Diao, F.; Du, X.; Gu, P.; Zhou, W. Development of deep-sea mining and its environmental impacts: A review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1598584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulikas, D.; Katona, S.; Ilves, E.; Ali, S.H. Life cycle climate change impacts of producing battery metals from land ores versus deep-sea polymetallic nodules. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vare, L.L.; Baker, M.C.; Howe, J.A.; Levin, L.A.; Neira, C.; Ramirez-Llodra, E.Z.; Reichelt-Brushett, A.; Rowden, A.A.; Shimmield, T.M.; Simpson, S.L.; et al. Scientific Considerations for the Assessment and Management of Mine Tailings Disposal in the Deep Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Jia, Y.; Chu, F.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, N.; Li, B.; Quan, Y. Effects of Migration and Diffusion of Suspended Sediments on the Seabed Environment during Exploitation of Deep-Sea Polymetallic Nodules. Water 2022, 14, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, N.; Benbow, S.; Weller, C.; Howard, P. An Assessment of the Risks and Impacts of Seabed Mining on Marine Ecosystems; Fauna & Flora: Cambridge, UK, 2023; p. 34. Available online: https://www.fauna-flora.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/fauna-flora-deep-sea-mining-update-report-march-23.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Morato, T.; Juliano, M.; Pham, C.K.; Carreiro-Silva, M.; Martins, I.; Colaço, A. Modelling the Dispersion of Seafloor Massive Sulphide Mining Plumes in the Mid Atlantic Ridge Around the Azores. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 910940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmons, R.; De Wit, L.; De Stigter, H.; Spearman, J. Dispersion of Benthic Plumes in Deep-Sea Mining: What Lessons Can Be Learned From Dredging? Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 868701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuscher, M.G.; Baguley, J.G.; Conrad-Forrest, N.; Cooksey, C.; Hyland, J.L.; Lewis, C.; Montagna, P.A.; Ricker, R.W.; Rohal, M.; Washburn, T. Temporal patterns of Deepwater Horizon impacts on the benthic infauna of the northern Gulf of Mexico continental slope. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, C.R.; Nunnally, C.; Benfield, M.C. Persistent and substantial impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on deep-sea megafauna. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 191164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.R.; Renegar, D.A. Petroleum hydrocarbon toxicity to corals: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztig, L.I. Deep Sea Mining in Social Sciences: A Systematic Review. J. Int. Dev. 2025, 37, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, R.; Childs, J.; Steinberg, P.; Mabon, L.; Matsuda, H.; Squire, R.; McLellan, B.; Esteban, M. A critical social perspective on deep sea mining: Lessons from the emergent industry in Japan. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 193, 105242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeckel, A.; Harden-Davies, H.; Amon, D.J.; Van Der Grient, J.; Hanich, Q.; Van Leeuwen, J.; Niner, H.J.; Seto, K. Deep seabed mining lacks social legitimacy. Npj Ocean Sustain. 2023, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Rivera, M. No people, no problem—Narrativity, conflict, and justice in debates on deep-seabed mining. Geogr. Helvetica 2020, 75, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, J. Greening the blue? Corporate strategies for legitimising deep sea mining. Political Geogr. 2019, 74, 102060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Putten, E.I.; Aswani, S.; Boonstra, W.J.; De La Cruz-Modino, R.; Das, J.; Glaser, M.; Heck, N.; Narayan, S.; Paytan, A.; Selim, S.; et al. History matters: Societal acceptance of deep-sea mining and incipient conflicts in Papua New Guinea. Marit. Stud. 2023, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, J.R.; Myers, K. Social cost benefit analysis for deep sea minerals mining. Mar. Policy 2018, 95, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lèbre, É.; Kung, A.; Savinova, E.; Valenta, R.K. Mining on land or in the deep sea? Overlooked considerations of a reshuffling in the supply source mix. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 191, 106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nijen, K.; Van Passel, S.; Squires, D. A stochastic techno-economic assessment of seabed mining of polymetallic nodules in the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone. Mar. Policy 2018, 95, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowski, T.; Urbanek, M.; Baláž, P. Structural Economic Assessment of Polymetallic Nodules Mining Project with Updates to Present Market Conditions. Minerals 2021, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]