Discussion on the Genesis of Vein-Type Copper Deposits in the Northern Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Regional Metallogenetic Background

3. Geological Characteristics of Ore Deposits

4. Sample Testing and Results

4.1. Samples and Methods

4.2. Result

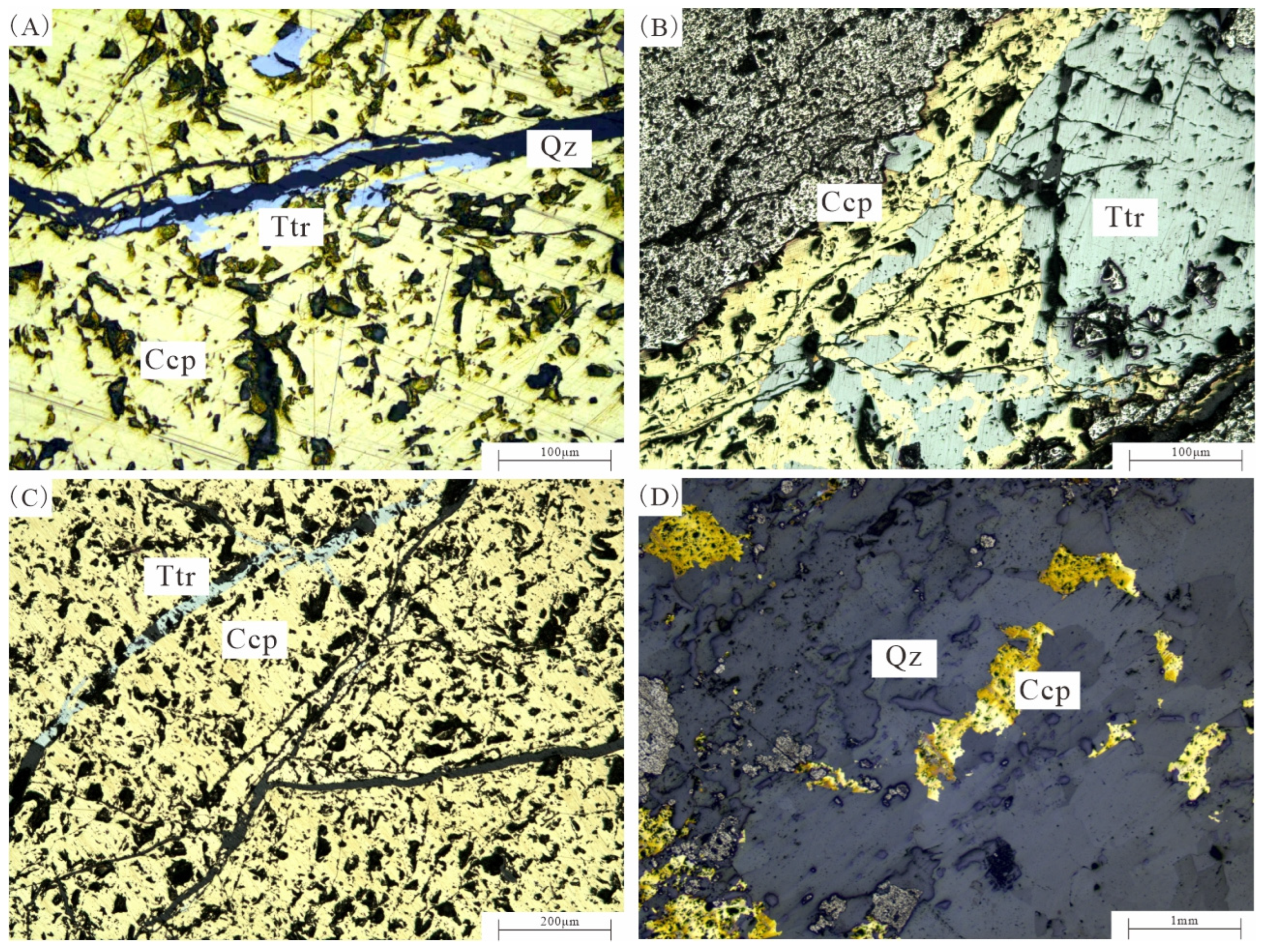

4.2.1. Petrographic Characteristics

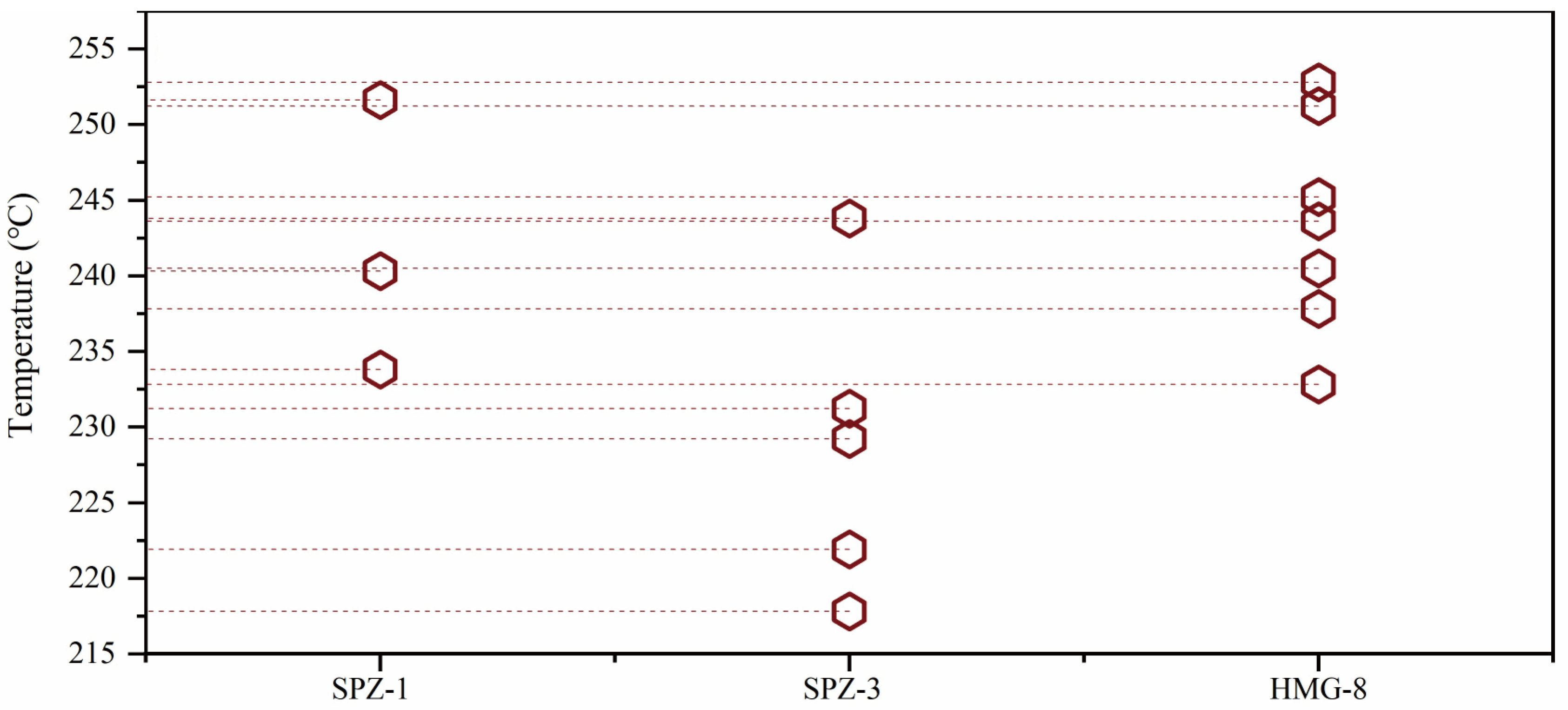

4.2.2. Results of Fluid Inclusion Thermometry

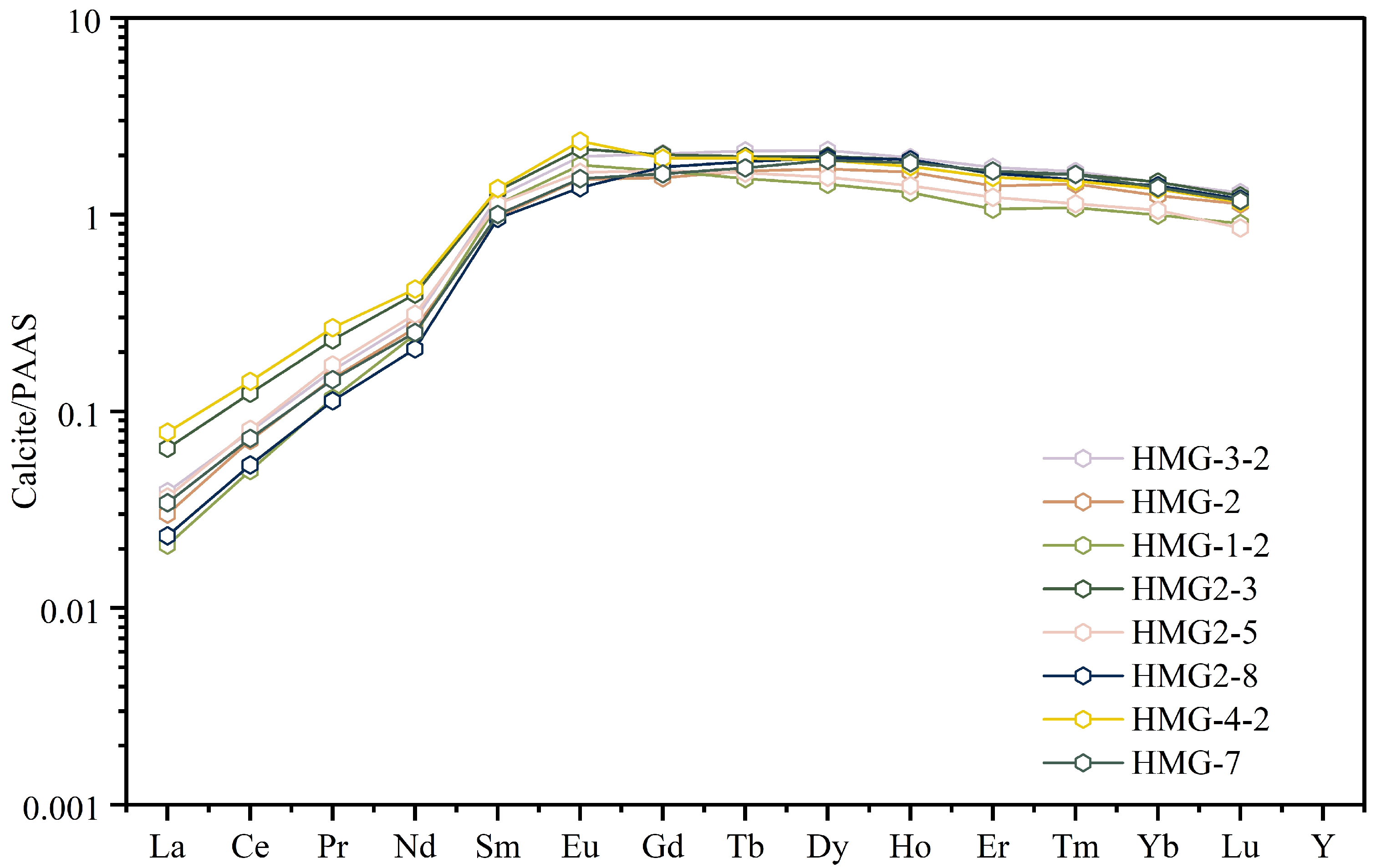

4.2.3. REE

4.2.4. Sr Isotopes

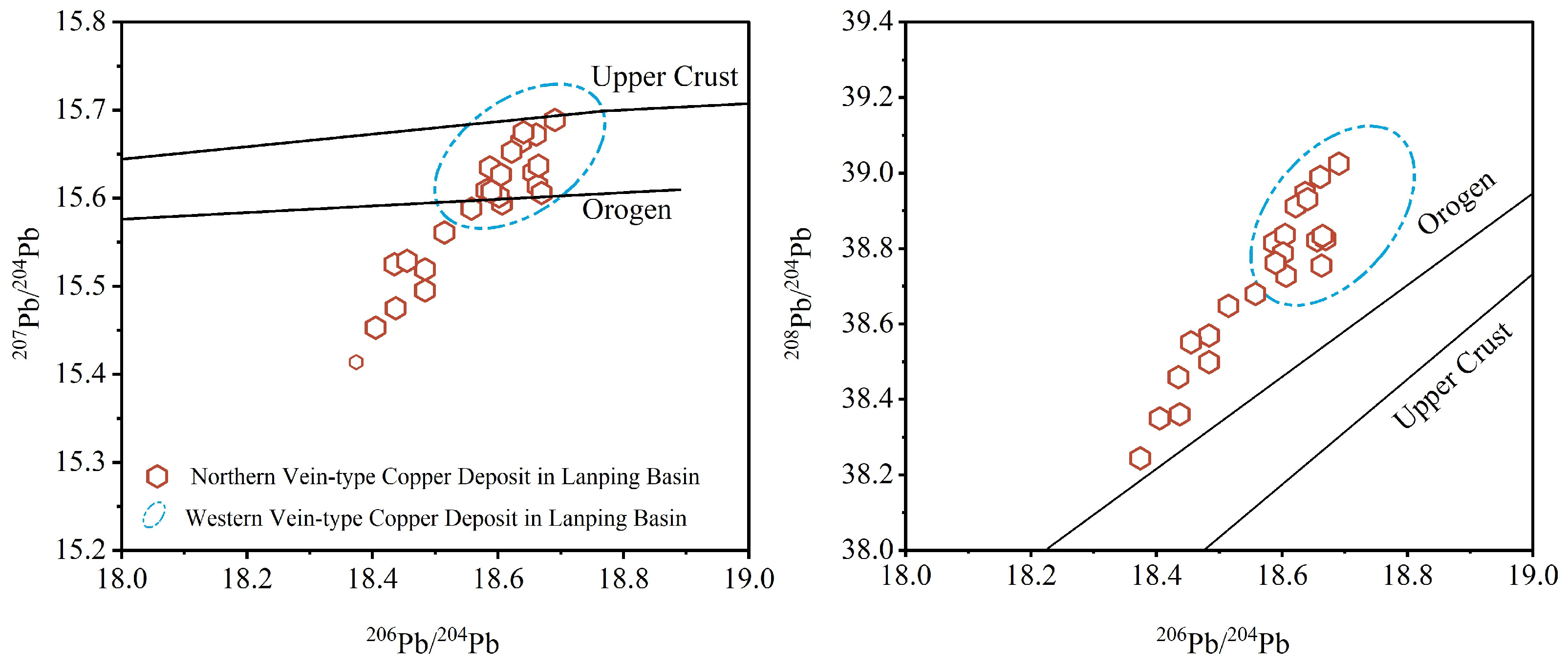

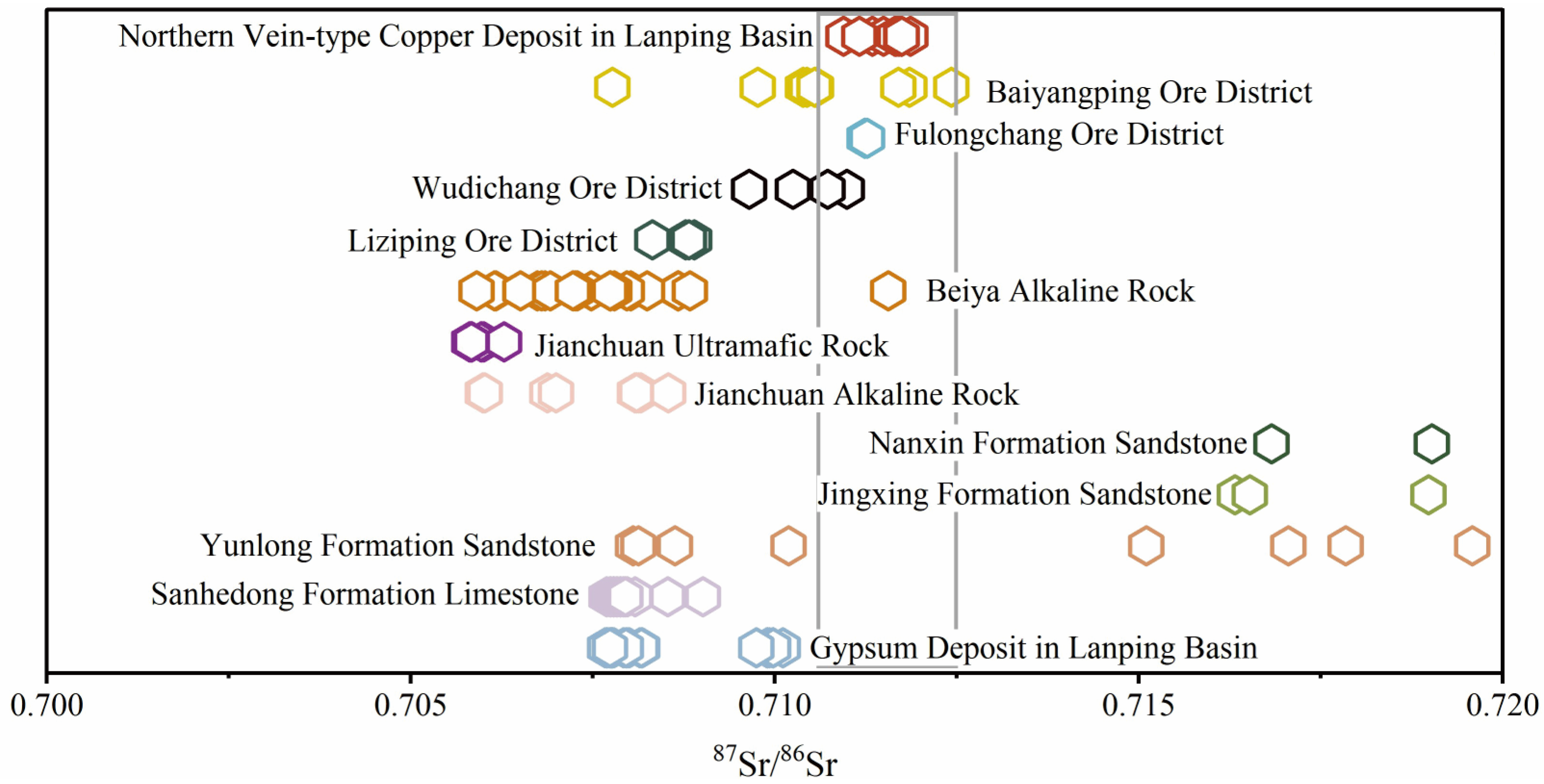

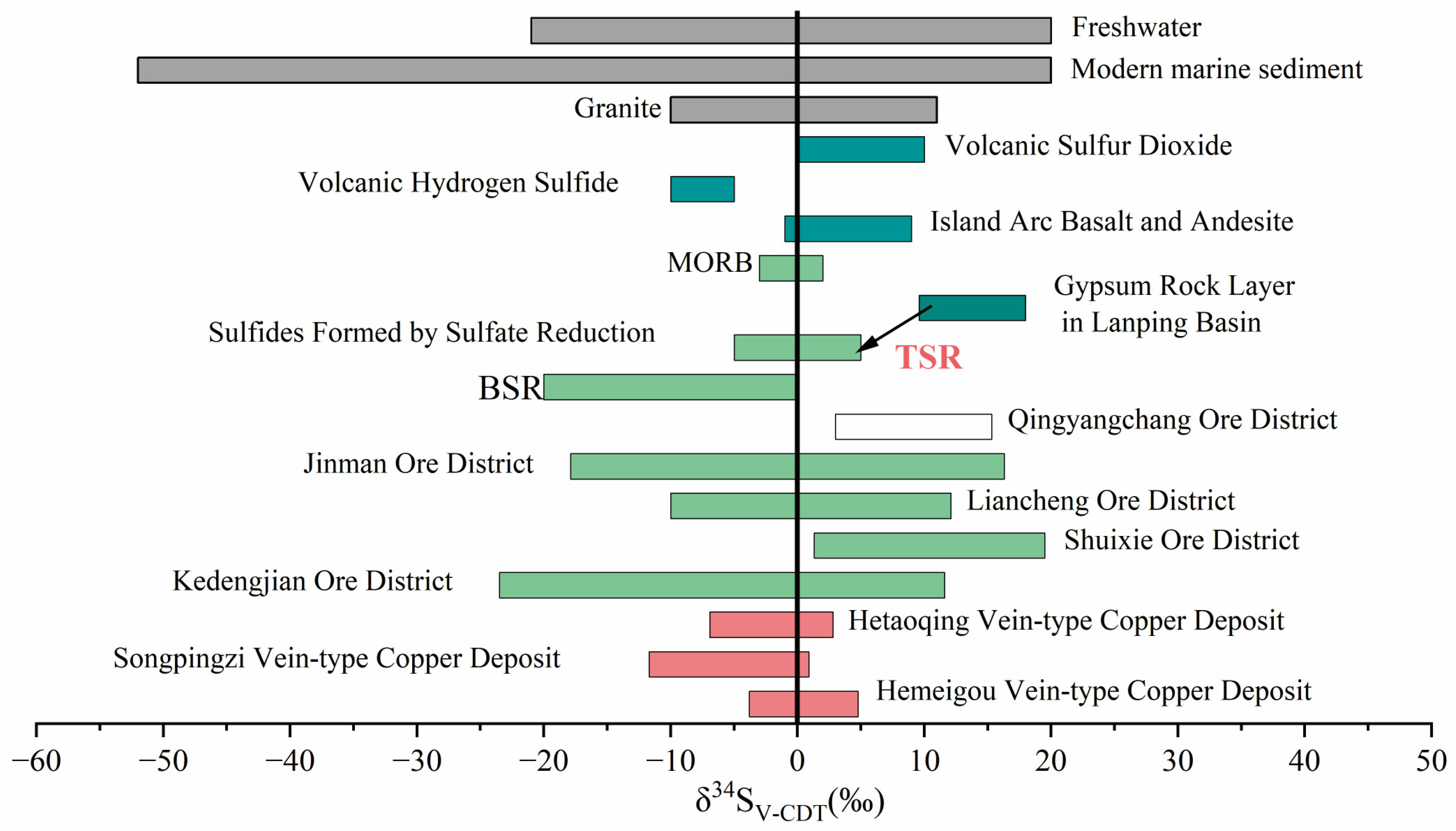

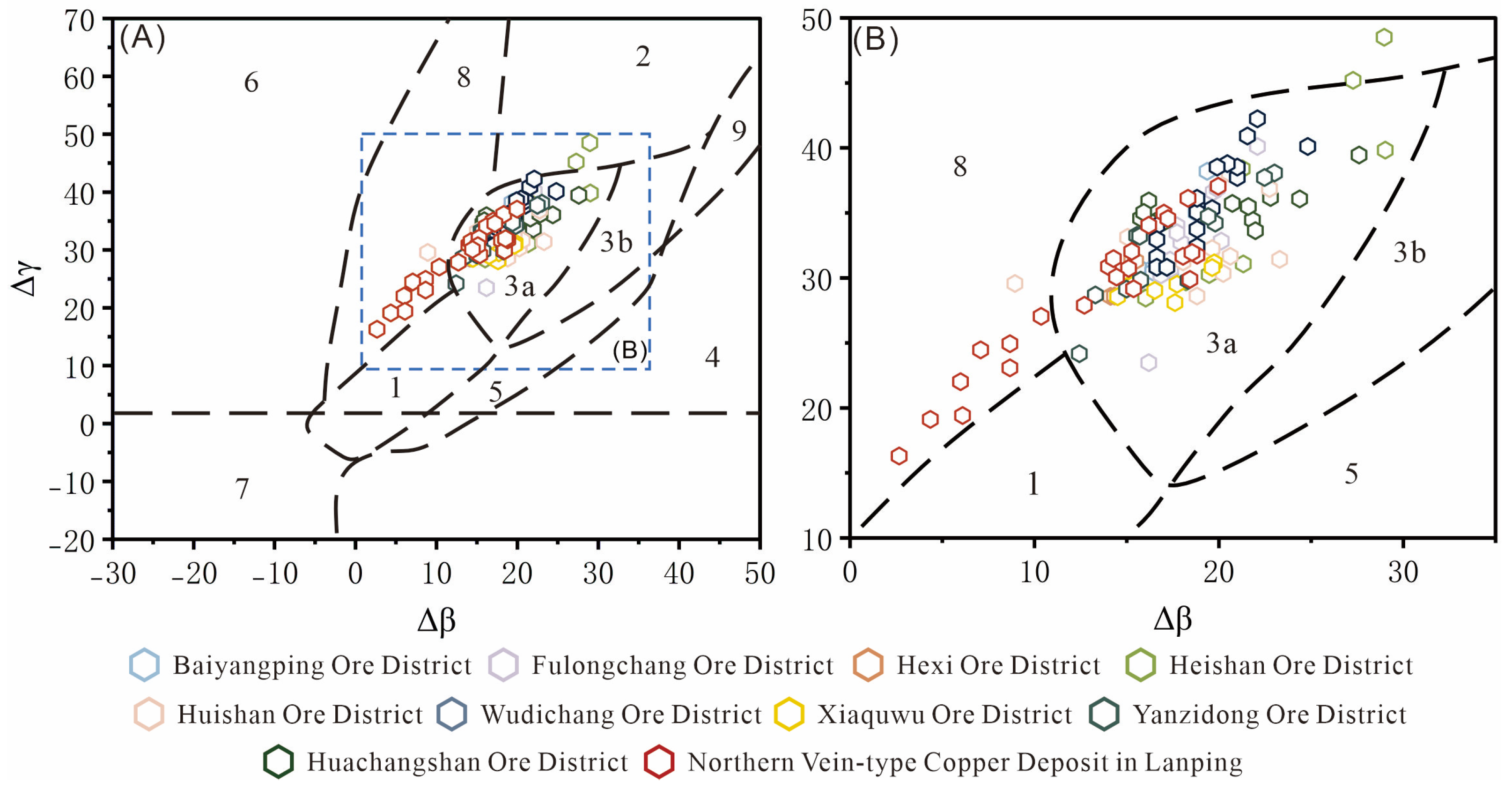

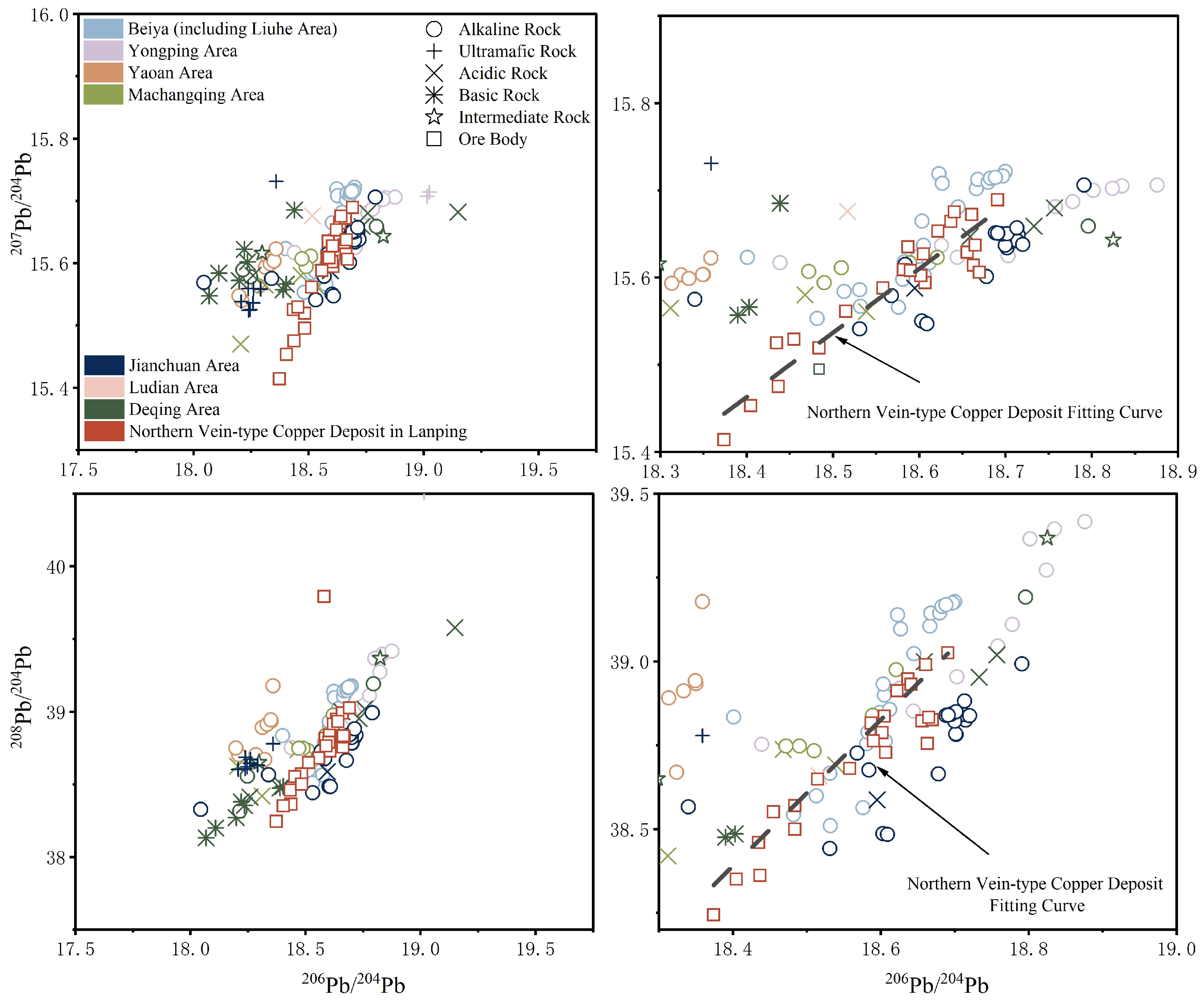

4.2.5. S and Pb Isotopes

5. Discussion

5.1. Properties and Sources of Ore-Forming Fluids

5.2. Ore-Forming Material

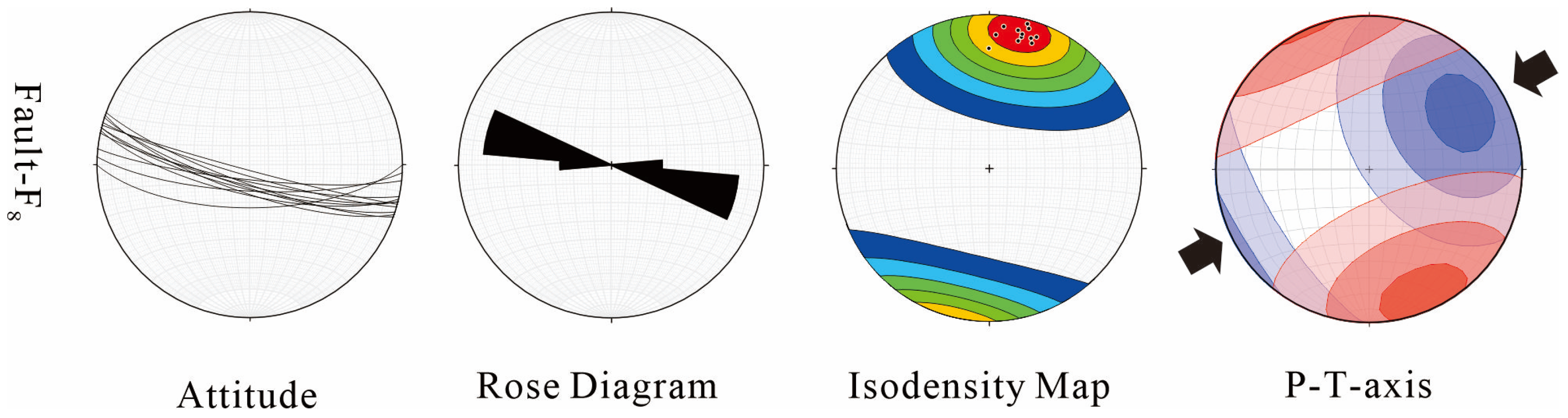

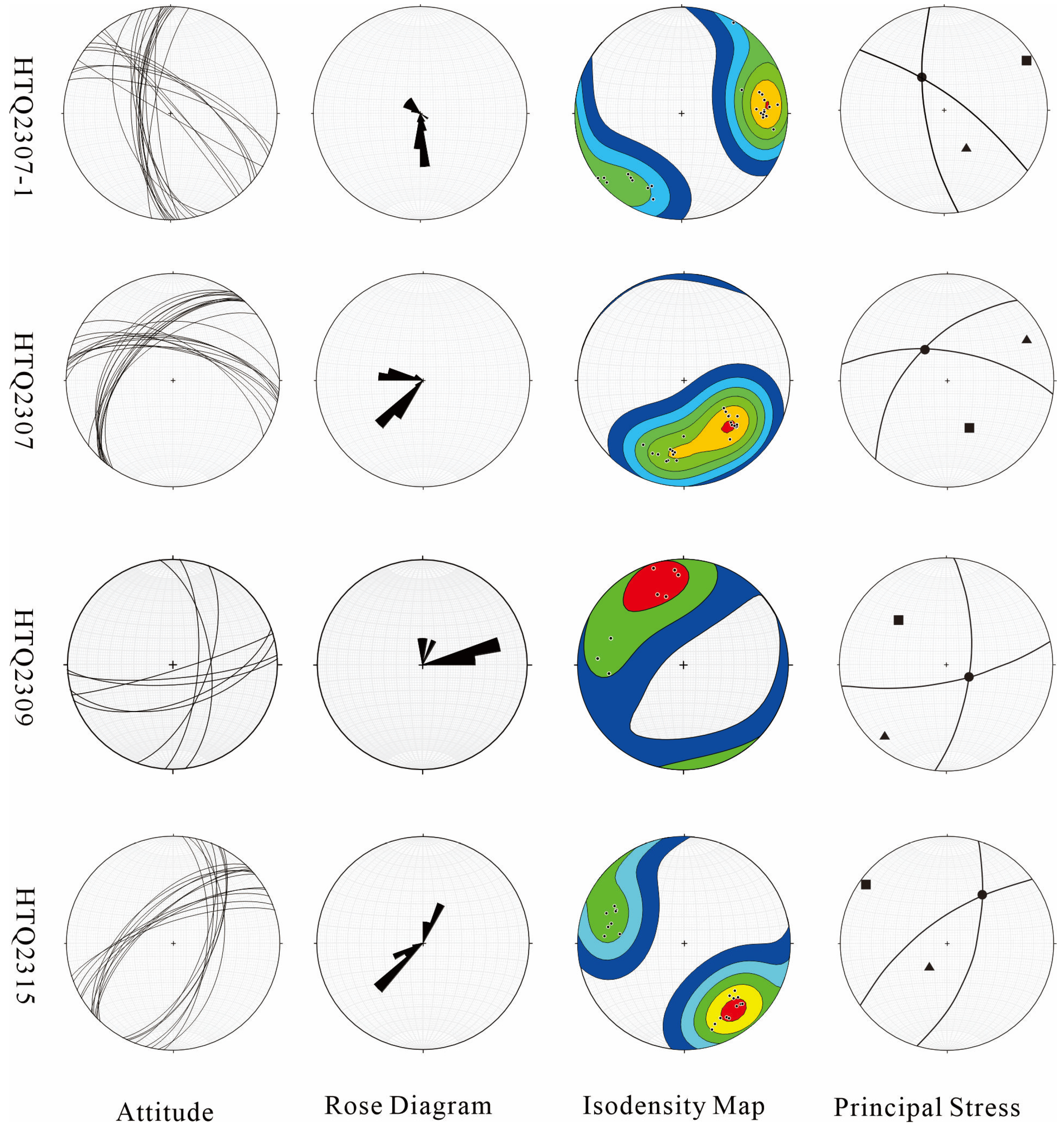

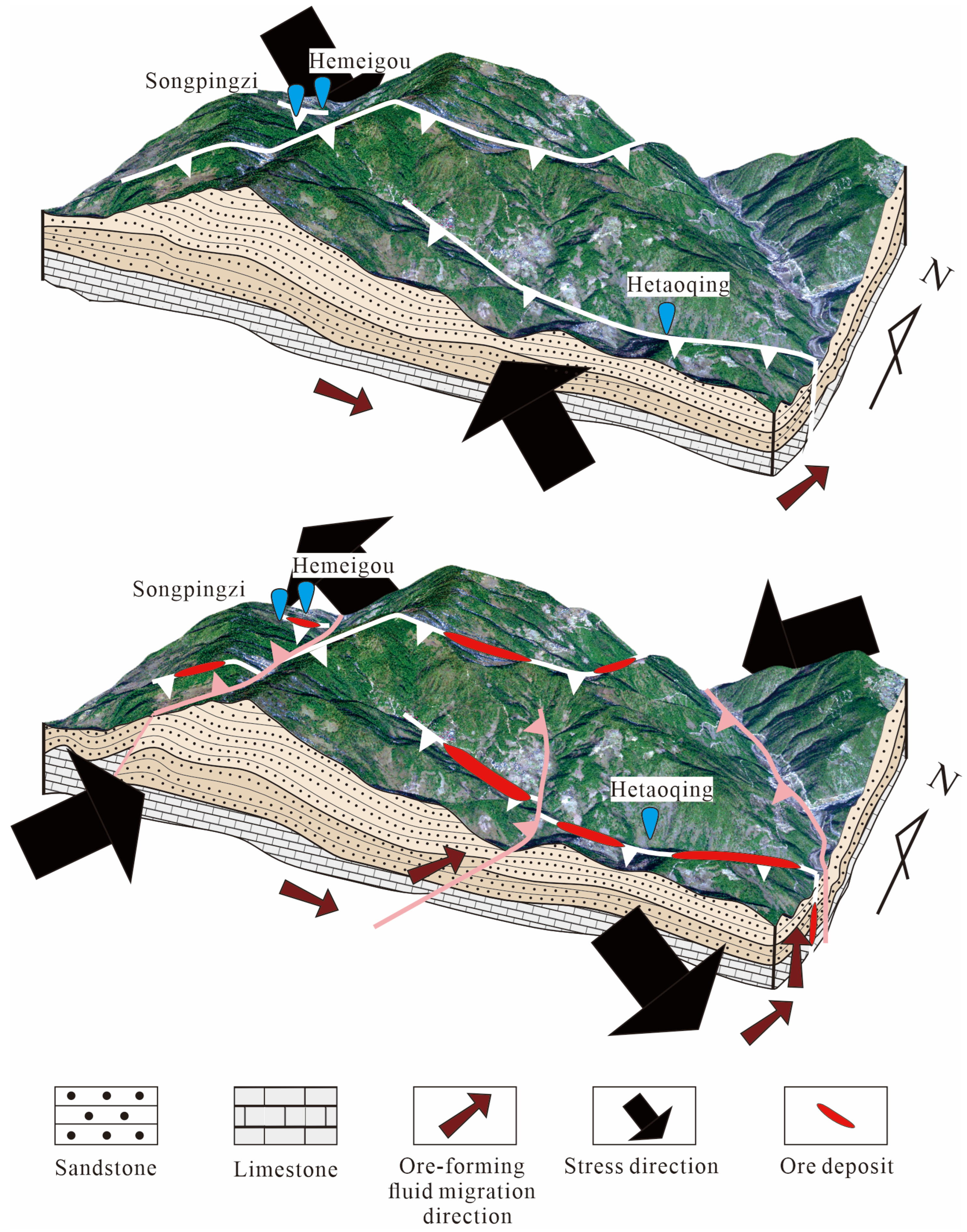

5.3. Ore-Controlling Structures

5.4. Genesis of Mineral Deposit

| Deposit | S Source | Pb Source | Metallogenic Epoch | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Vein-type Copper Deposit in Lanping | Mixed source of deep magmatic hydrothermal sulfur generated during basin tectonic activities and gypsum rock sulfur reduced by organic matter (i.e., thermochemical sulfate reduction, TSR). | Mainly from orogenic-belt lead, with certain contributions from magmatic sources on both sides of the basin and metamorphic rocks. | This paper | This paper |

| Jinman Copper Deposit in Lanping | Deep metamorphic rock series may also have contributions from surrounding rocks, sedimentary rocks, biogenic sulfur, and bacterial reduction in sulfates to the sulfur source. | Mainly from sedimentary rocks of the upper crust in the Lanping Basin; may have some addition of deep lead. | 56–54 Ma | [102,162,176,177] |

| Liancheng Copper Deposit in Lanping | Mainly from the deep part; in the late stage, sulfur from the strata of surrounding rocks in the basin is added. | Mainly from sedimentary rocks of the upper crust in the Lanping Basin and mixed with the mantle, leading to varying degrees. | 51–48 Ma | [102,155,162,178] |

| Qingyangchang Copper Deposit in Lanping | From evaporite (gypsum-salt) formations in basin strata, being the reduction product of sulfates. | \ | \ | [99] |

| Shuixie Copper Deposit in Lanping | Mainly from evaporite strata in the basin. | Mainly from sedimentary strata in the basin and may have some addition of minerals from the basement rock series. | 59.2 ± 0.8 Ma | [177,179] |

| Kedengjian Copper Deposit in Lanping | The main sulfur source is marine sulfate. | Lead mainly comes from upper crustal sedimentary rocks with the involvement of the deep crust. | ~100 Ma | [19,100,101] |

6. Conclusions

- Integrated geological, geochemical, and structural analysis of the vein-type copper deposits in the northern Lanping Basin leads to the following conclusions: the ore-forming materials primarily originated from deep magmatic hydrothermal activities. The lead isotope compositions of the northern copper deposits are consistent with other copper deposits within the basin and exhibit a close affinity to the Cenozoic alkaline rocks around the basin. The sulfur source is closely linked to TSR.

- Strontium isotope signatures indicate that the ore-forming fluids were derived from, or at least interacted extensively with, the gypsum-salt strata within the basin, indicating the migration path of the fluid. Data from rare-earth elements (REEs), including LREE depletion, negative Ce anomalies, and positive Eu anomalies, collectively reveal that the ore-forming fluids underwent significant water–rock interaction during their migration.

- The mineralization was structurally prepared and triggered by specific tectonic events. Pre-ore NE–SW compression created the primary fault architectures (e.g., the F8 fault system) that provided conduits and spaces for fluid migration and ore emplacement. The actual precipitation of ore-forming materials was likely facilitated by a late Cenozoic abrupt change in the stress field, which caused fluid pressure release and mixing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Conjugate Joints | Fault | Fault Striations | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTQ2307-1 | HTQ2307 | HTQ2309 | HTQ2315 | HTQ2311 | HTQ2318 | HTQ2311 | HTQ2318 | ||||||||

| Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Trend | Plunge | Trend | Plunge |

| 321 | 44 | 267 | 60 | 83 | 60 | 330 | 69 | 193 | 74 | 177 | 76 | 119 | 32 | 252 | 40 |

| 305 | 38 | 249 | 51 | 94 | 70 | 329 | 71 | 194 | 79 | 167 | 81 | 115 | 37 | 252 | 37 |

| 307 | 41 | 270 | 64 | 110 | 62 | 318 | 59 | 180 | 67 | 177 | 81 | 118 | 33 | 263 | 13 |

| 308 | 45 | 261 | 68 | 160 | 60 | 317 | 67 | 192 | 81 | 163 | 75 | 125 | 39 | 248 | 34 |

| 312 | 50 | 265 | 80 | 166 | 56 | 316 | 68 | 196 | 84 | 179 | 76 | 121 | 38 | 247 | 30 |

| 310 | 55 | 266 | 72 | 177 | 74 | 320 | 66 | 195 | 87 | 133 | 64 | 120 | 33 | 254 | 32 |

| 312 | 56 | 268 | 67 | 163 | 85 | 342 | 74 | 199 | 75 | 158 | 71 | 127 | 35 | 254 | 23 |

| 322 | 60 | 255 | 65 | 175 | 79 | 334 | 67 | 198 | 78 | 152 | 73 | 120 | 38 | 242 | 34 |

| 309 | 45 | 257 | 67 | 339 | 70 | ||||||||||

| 311 | 56 | 271 | 66 | 319 | 55 | ||||||||||

| 304 | 51 | 269 | 67 | 313 | 55 | ||||||||||

| 313 | 52 | 272 | 69 | 315 | 61 | ||||||||||

| 310 | 55 | 273 | 66 | 102 | 62 | ||||||||||

| 312 | 54 | 280 | 77 | 98 | 51 | ||||||||||

| 9 | 57 | 50 | 84 | 95 | 64 | ||||||||||

| 11 | 56 | 52 | 89 | 116 | 60 | ||||||||||

| 7 | 58 | 47 | 85 | 115 | 60 | ||||||||||

| 8 | 60 | 210 | 88 | 118 | 63 | ||||||||||

| 23 | 64 | 24 | 66 | 111 | 67 | ||||||||||

| 19 | 63 | 22 | 63 | 105 | 60 | ||||||||||

| 11 | 66 | 18 | 74 | 311 | 25 | ||||||||||

| 12 | 67 | 36 | 67 | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 65 | 41 | 65 | ||||||||||||

| 32 | 61 | 38 | 66 | ||||||||||||

References

- Hou, Z.Q.; Song, Y.C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.L.; Yang, Z.M.; Yang, Z.S.; Liu, Y.F.; Tian, S.H.; He, L.Q.; Chen, K.X. Thrust-controlled, sediments-hosted Pb-Zn-Ag-Cu deposits in eastern and northern margins of the Tibetan orogenic belt: Geological features and tectonic model. Miner. Depos. 2008, 27, 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Santosh, M. Cenozoic Tectono-Magmatic and Metallogenic Processes in the Sanjiang Region, Southwestern China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 138, 268–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Zaw, K.; Pan, G.; Mo, X.; Xu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Li, X. Sanjiang Tethyan Metallogenesis in S.W. China: Tectonic Setting, Metallogenic Epochs and Deposit Types. Ore Geol. Rev. 2007, 31, 48–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Wang, C. Tethys Tectonic Evolution and Its Bearing on the Distribution of Important Mineral Deposits in the Sanjiang Region, SW China. Gondwana Res. 2014, 26, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.Q.; Pan, G.T.; Wang, A.J.; Mo, X.X.; Tian, S.H.; Sun, X.M.; Ding, L.; Wang, E.Q.; Gao, Y.F.; Xie, Y.L. Metallogenesis in Tibetan collisional orogenic belt:II. Mineralization in a late-collisional transformation setting. Miner. Depos. 2006, 25, 521–543. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.; Zeng, R.; Liu, S.; Chi, G.; Qing, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, D. Geologic, Fluid Inclusion and Isotopic Characteristics of the Jinding Zn–Pb Deposit, Western Yunnan, South China: A Review. Ore Geol. Rev. 2007, 31, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yan, C.; He, Y.; Zhao, E.; Su, J.; Li, J.; Dong, S. Summary of Triassic Paleogene Geological History in Lanping Simao Area, Western Yunnan. Yunnan Geol. 2024, 43, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.J.; Zhu, Z.J.; Ding, T.; Ma, Y.C.; Wang, T.; Zhou, S.H. Geochemical characteristics and geological significance of the Upper Triassic Sanhedong Formation limestone in the Hexi Area of Northwest Yunnan Province. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2024, 43, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, C.; Rodríguez-López, J.P.; Yi, H.; Xia, G.; Wagreich, M. Mid-Cretaceous Aeolian Desert Systems in the Yunlong Area of the Lanping Basin, China: Implications for Palaeoatmosphere Dynamics and Paleoclimatic Change in East Asia. Sediment. Geol. 2018, 364, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.-Y.; Bi, X.-W.; Fayek, M.; Hu, R.-Z.; Wu, L.-Y.; Zou, Z.-C.; Feng, C.-X.; Wang, X.-S. Microscale Sulfur Isotopic Compositions of Sulfide Minerals from the Jinding Zn–Pb Deposit, Yunnan Province, Southwest China. Gondwana Res. 2014, 26, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Ludington, S.D.; Zhou, S.; Tan, Y.; Yan, G.; Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhu, Q.; Qiu, L.; Ren, X.; et al. Discussion on the Dextral Movement and Its Effect in Continental China and Adjacent Areas since Cenozoic. China Geol. 2018, 1, 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, D.; Yang, T.N.; Liang, M.J.; Liao, C.; Dong, M.M.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.K. Ore-controling structural analysis of thrust-and-tear fault associations in the Baiyangchang copper deposit in western Yunnan. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2022, 38, 3515–3530. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z.; Cook, N.J. Metallogenesis of the Tibetan Collisional Orogen: A Review and Introduction to the Special Issue. Ore Geol. Rev. 2009, 36, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiming, L.; Jiajun, L.; Ruizhong, H.; Mingqin, H.; Yuping, L.; Chaoyang, L. Tectonic Setting and Nature of the Provenance of Sedimentary Rocks in Lanping Mesozoic-Cenozoic Basin: Evidence from Geochemistry of Sandstones. Chin. J. Geochem. 2003, 22, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Xiang, J.; Jin, Y.; Cen, W.; Zhu, G.; Shen, C. Petroleum Evolution and Its Genetic Relationship with the Associated Jinding Pb Zn Deposit in Lanping Basin, Southwest China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 294, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Geology and genesis of the Baiyangping lead zinc copper silver polymetallic deposit in the Lanping Basin. Chin. Acad. Geo-Log. Sci. 2011, 37, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y. Study on the Vein Structure and Ore-Forming Fluid of Maocaoping Vein Shaped Cu Deposit in Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan, China. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.C.; Hou, Z.Q.; Yang, T.N.; Zhang, H.R.; Yang, Z.S.; Tian, S.H.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, X.H.; Liu, Y.X.; Xue, C.D. Sediment hosted Himalayan base metal deposits in Sanjiang region characteristics and genetic types. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2011, 30, 355–380. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xu, L.-L.; Bi, X.-W.; Tang, Y.-Y.; Sheng, X.-Y.; Yu, H.-J.; Liu, G.; Ma, R. New Titanite U–Pb and Molybdenite Re–Os Ages for a Hydrothermal Vein-Type Cu Deposit in the Lanping Basin, Yunnan, SW China: Constraints on Regional Metallogeny and Implications for Exploration. Min. Depos. 2021, 56, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Hou, Z.; Xue, C.; Huang, S. New Mapping of the World-Class Jinding Zn-Pb Deposit, Lanping Basin, Southwest China: Genesis of Ore Host Rocks and Records of Hydrocarbon-Rock Interaction. Econ. Geol. 2020, 115, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Song, Y.; Hou, Z.; Xue, C. Chemical and Stable Isotopic (B, H, and O) Compositions of Tourmaline in the Maocaoping Vein-Type Cu Deposit, Western Yunnan, China: Constraints on Fluid Source and Evolution. Chem. Geol. 2016, 439, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bagas, L.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D.; Du, B.; Shi, K. The Genesis of the Liancheng Cu–Mo Deposit in the Lanping Basin of SW China: Constraints from Geology, Fluid Inclusions, and Cu–S–H–O Isotopes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 92, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.; Xue, C. Abundance of CO2-Rich Fluid Inclusions in a Sedimentary Basin-Hosted Cu Deposit at Jinman, Yunnan, China: Implications for Mineralization Environment and Classification of the Deposit. Min. Depos. 2011, 46, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.-F.; Zhou, M.-F.; Hitzman, M.W.; Li, J.-W.; Bennett, M.; Meighan, C.; Anderson, E. Late Paleoproterozoic to Early Mesoproterozoic Tangdan Sedimentary Rock-Hosted Strata-Bound Copper Deposit, Yunnan Province, Southwest China. Econ. Geol. 2012, 107, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, D.; Wang, X.; Qu, J.; Guo, L. Structural Feature and Its Significance of the Northernmost Segment of the Tertiary Biluoxueshan-Chongshan Shear Zone, East of the Eastern Himalayan Syntaxis. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2011, 54, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.R.; Hou, Z.Q. The style and process of continental collisional orogeny: Examples from the Tethys collisional orogenic belt. Acta Geol. Sin. 2015, 89, 1539–1559. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.Q.; Song, H.B.; Ran, C.Y.; Yan, J. Evidence on the gene-sis of the transformation of the Jinman copper deposit in Lanping, Yunnan Province. Geol. Explor. 1998, 17, 15–17+20. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Li, Z.Y. The geochemical characteristics and hydrothermal sedimentary genesis of a new type of copper deposit. Geochimica 1997, 26, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Song, Y.C.; Hou, Z.Q.; Xue, C.D.; Huang, S.Q.; Han, C.H.; Zhuang, L.L. Fluid inclusitions and stable isotopes study of Maocaoping vein Cu deposit in Lanping basin, western Yunnan. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2015, 33, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.P.; Jiang, S.Y.; Liao, Q.L.; Pan, J.Y.; Dai, B.Z. Lead and sulfur isotope geochemistry and the ore sources of the Yunnan province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2003, 19, 799–807. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Song, Y.; Chen, K.; Hou, Z.; Yu, F.; Yang, Z.; Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. Thrust-Controlled, Sediment-Hosted, Himalayan Zn–Pb–Cu–Ag Deposits in the Lanping Foreland Fold Belt, Eastern Margin of Tibetan Plateau. Ore Geol. Rev. 2009, 36, 106–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijlen, W.; Banks, D.A.; Muchez, P.; Stensgard, B.M.; Yardley, B.W.D. The Nature of Mineralizing Fluids of the Kipushi Zn-Cu Deposit, Katanga, Democratic Repubic of Congo: Quantitative Fluid Inclusion Analysis Using Laser Ablation ICP-MS and Bulk Crush-Leach Methods. Econ. Geol. 2008, 103, 1459–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.-J.; Fan, H.-R.; Liu, X.; Yang, K.-F.; Hu, F.-F.; Xu, W.-G.; Wen, B.-J. Mineralogy, Chalcopyrite ReOs Geochronology and Sulfur Isotope of the Hujiayu Cu Deposit in the Zhongtiao Mountains, North China Craton: Implications for a Paleoproterozoic Metamorphogenic Copper Mineralization. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 78, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.-L.; Li, J.; Lan, T.-G.; Liu, G.; Bi, X.-W. Genesis of a Sediment-Hosted Vein-Type Cu Deposit in the Lanping Basin, SW China: New Insights from Geology and LA–ICP–MS Analysis of Fluid Inclusions. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 168, 106051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.B.; Wang, B.D.; Tang, Y.; Luo, L.; He, J.; Jiang, L.L.; Zhao, H.S.; Chen, L. Research progress and prospects of Tethys in. Sanjiang orogenic belt, Southwest China. Geol. Bull. China 2021, 40, 1799–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.F.; Shi, K.X.; Wang, C.M.; Wu, B.; Du, B.; Chen, J.Y.; Xia, J.S.; Chen, J. Ore genesis of the Jinman copper deposit in the Lanping Basin, Sanjiang Orogen: Constraints by copper and sulfur isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2016, 32, 2392–2406. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.W.; Ke, X.; He, W.H.; Xu, Y.D.; Luo, L.; Kong, L.Y.; Chen, F.N.; Zhang, K.X. The Late Paleozoic-Mesozoic Ocean plate stratigraphy tectonic-stratigraphic realms and framework of the Tethyan orogenic system in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Earth Sci. 2024, 50, 3651–3678. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Wang, C.M.; Li, G.J. Style and process of the superimposed mineralization in the Sanjiang Tethys. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2012, 28, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.Q.; Chen, K.X.; Yu, F.M.; Wei, J.Q.; Yang, A.P.; Li, H. The overthrust structure and its ore controlling effect in Lanping Basin, Yunnan Province. Geol. Explor. 2004, 4, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Z.; Chen, Y. Nature and Evolution of Lanping-Simao Basin Prototype. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2005, 33, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.H.; Fan, W.M.; Lin, G. Deep Processes and Mantls-Crust Compound Mineralization in The Evolution of The Lanping-Simao Mesozoic-Cenozoic Diwa Basin in Western Yunan, China. Geotecton. Metallog. 1990, 14, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Yang, T.; Xue, C.; Xin, D.; Yan, Z.; Liao, C.; Han, X.; Xie, Z.; Xiang, K. Complete Deformation History of the Transition Zone between Oblique and Orthogonal Collision Belts of the SE Tibetan Plateau: Crustal Shortening and Rotation Caused by the Indentation of India into Eurasia. J. Struct. Geol. 2022, 156, 104545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, C.L.; Wang, J.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, L.S. Evolution of the Lanping Mesozoic Cenozoic sedimentary basin. J. Miner. Pet. 1999, 19, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, W.; Ren, H.C.; Li, J.Y. Analysis of lithostratigraphic and biostratigraphy characteristics and sedimentary environment of Huakaizuo Formation in West Yunnan Province. Miner. Explor. 2024, 15, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.K.; Yang, D.J.; Sun, G.R.; Yang, X.X.; Zhao, Q.H.; Hong, Z.M.; Zhao, C. Sedimentary facies and regional tectonic significance of Cretaceous in the middle of Lanping Basin, Yunnan Province. Geol. Surv. China 2023, 10, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, J.-W.; Cawood, P.A.; Fan, W.-M.; Wang, Y.-J.; Tohver, E.; McCuaig, T.C.; Peng, T.-P. Triassic Collision in the Paleo-Tethys Ocean Constrained by Volcanic Activity in SW China. Lithos 2012, 144–145, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.W.; Yang, T.N.; Liang, M.J.; Shi, P.L. LA-ICP-MS zircon U-Pb geochronology and geochemistry of volcanic rocks on the western margin of Lanping Basin in western Yunnan and their tectonic implications. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2014, 33, 471–490. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.C.; Wang, B.D.; He, J.; Wang, Q.Y.; Wu, Z. Petrogenesis of Middle Triassic bimodal volcanic rocks in the Weixi area, Yunnan Province and geological implication for the formation and evolution of the Jinshajiang arc–basin. Geol. Bull. China 2021, 40, 1892–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.M.; Peng, T.P.; Wang, Y.J. Triassic magmatism in the southern Lancangjiang zone, southwestern China and its constraints on the tectonic evolution of Paleo-Tethys. Earth Sci. Front. 2009, 16, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T. Magmatism, Rock Genesis, and Tectonic Significance of the Triassic Collision in the Lancang Jiangnan Belt. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry), Guangzhou, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Qi, X.X.; Chang, Y.L.; Ji, F.B.; Zhang, S.Q. Determination of the Formation Age of the Xiaodingxi Formation Volcanic Rocks in the Central South Section of the Lancang River Structural Belt and Its Structural Significance. Acta Georg. Sin. 2016, 90, 3192–3214. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.S.; Liu, X.P. Geochemical characteristics of collisional volcanic rocks in northwest Yunnan. Geochimica 1994, 23, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Yang, T.; Xue, C.; Liang, M.; Xin, D.; Xiang, K.; Jiang, L.; Shi, P.; Zhu, W.; Wan, L.; et al. Eocene Basins on the SE Tibetan Plateau: Markers of Minor Offset along the Xuelongshan–Diancangshan–Ailaoshan Structural System. Acta Geol. Sin. 2020, 94, 1020–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, Q. Subduction and Collision of the Jinsha River Paleo-Tethys: Constraints from Zircon U-Pb Dating and Geochemistry of the Ludian Batholith in the Jiangda–Deqen–Weixi Continental Margin Arc. Acta Geol. Sin. 2020, 94, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, C.; Bagas, L.; Du, B.; Shi, K.; Yang, L.; Zhu, J.; Duan, H. Petrogenesis of the Late Triassic Biluoxueshan Granitic Pluton, SW China: Implications for the Tectonic Evolution of the Paleo-Tethys Sanjiang Orogen. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2021, 211, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Exploration of the Geochemical Characteristics of Evaporite Rocks in the Lanping Basin and Their Relationship with Metal Mineralization. Master’s Thesis, East China University of Technology, Nanchang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.Y.; Li, L.X.; Zhang, H.Y. The ore-forming conditions and genesis of the Hetaoqing copper deposit in Lanping County, Yunnan Province. Yunnan Geol. 2017, 36, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, G.; Du, M.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Hou, M.; Bao, Y. Detailed Geological Investigation Report on Hetaojing Copper Mine, Lanping County, Yunnan Province; Yunnan Hongsheng Chiyuan Resources Co., Ltd.: Nujiang, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement; International Organization for Standardization: Genf, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- DZ/T 0184.14-1997; Determination of Sulfur Isotopic Composition in Sulfides. Ministry of Geology and Mineral Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1997.

- GB/T 17672-1999; Determinations for Isotopes of Lead, Strontium and Neodymium in Rock Samples. The State Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision: Beijing, China, 1999.

- Nance, W.B.; Taylor, S.R. Rare Earth Element Patterns and Crustal Evolution—I. Australian Post-Archean Sedimentary Rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1976, 40, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Han, Z.; Li, C.; Gao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, G. REE, Fe and Mn Contents of Calcites and Their Prospecting Significance for the Banqi Carlin-type Gold Deposit in Southwestern China. Geotecton. Metallog. 2018, 42, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Ling, H. S-Pb isotope geochemistry and Rb-Sr geochronology of the Penglai goldfield in the eastern Shangdong province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2006, 22, 2525–2533. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.F.; Yang, H.M. Sulfur isotope tracing of ore-forming hydrothermal fluid for metallic sulfide deposit. Adv. Earth Sci. 2016, 31, 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.X.; Bi, X.W.; Hu, R.Z.; Liu, S.; Wu, L.Y.; Tang, Y.Y.; Zou, Z.C. Study on paragenesis-separation mechanism and source of ore-forming element in the Baiyangping Cu-Pb-Zn-Ag polymetallic ore deposit, Lanping basin, southwestern China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2011, 27, 2609–2624. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J. S-Pb Isotopic Geochemistry of Copper Multi-Metal Deposits in Hexi, Yunnan Province. Geol. Miner. Resour. South China 2001, 03, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, E. Genesis of the West Ore Belt Deposit in Lanping Baiyangping Copper Silver Polymetallic Ore Concentration. Area. Yunnan Geol. 2005, 24, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.C.; Hu, R.Z.; Bi, X.W.; Wu, L.Y.; Feng, C.X.; Tang, Y.Y. Study on isotope geochemistry compositions of the Baiyangping silver-copper polymetallic ore deposit area, Yunnan Province. Geochemistry 2012, 41, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.X.; Hu, R.Z.; Bi, X.W.; Peng, J.T.; Tang, Q.L. Ore lead isotopes as a tracer for ore-forming material sources: A review. Geol. Geochem. 2002, 30, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.Q.; Chen, K.X.; Wei, J.Q.; Yu, F.M. Geological and geochemical characteristics and genesis of ore deposits in eastern ore belt of Baiyangping area, Yunnan Province. Miner. Depos. 2005, 24, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.C.; Wang, J.B.; Zhu, X.Y.; Li, C.H.; Wu, J.J.; Wang, Y.B.; Shi, M.; Guo, Y.H. Precise discrimination on the mineralization processes of the Jinding Pb-Zn deposit, Lanping Basin, western Yunnan, China: Evidence from in situ trace elements and S-Pb isotopes of sulfides. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2023, 39, 2511–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S. The Geochemical Mechanism of the Formation of Copper Silver Polymetallic Ore Fields in the Baiyangping area. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q. The Relationship Between Fluid and Mineralization of Baiyangping Silver Polymetallic Deposit in Lanping, Yunnan: A study of Fluid Inclusions. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, B. The Ore-Forming Characteristics and Genesis of the Huachangshan Lead-Zinc Polymetallic Deposit in Yunnan Province. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H. Geological characteristics of the Lanshan polymetallic deposit in Lanping. Yunnan Geol. 1998, 17, 83–86+88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; He, M.Y. Lead and sulfur isotopic tracing of the ore-forming material from the Baiyangping copper-silver polymetallic deposit in Lanping, Yunnan. Sediment. Geol. Tethyan Geol. 2003, 23, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Pan, X.; Guo, T. Geochemical Characteristics and Metallogenic Age of the East Ore Belt in Baiyangping Polymetallic Ore Concentration Area. J. Geomech. 2016, 22, 294–309. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.D.; Zhou, L. Ore-forming Fluid Migration in Relation to Mineralization Zoning in Cu-Polymetallic Mineralization District of Northern Lamping, Yunnan: Evidence from Lead Isotope and Mineral Chemistry of Ores. Miner. Depos. 2004, 23, 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H. Metallogenic Characteristics and Geological Conditions of Copper Polymetallic Deposits in the Central and Northern Parts of the Lanping Basin in Western Yunnan. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zartman, R.E.; Doe, B.R. Plumbotectonics—the Model. Tectonophysics 1981, 75, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.B.; Li, Z.Y. REE geochemical study of Jinding super large lead-zinc deposit. Geochemistry 1991, 04, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, M.; MÖller, P. Rare Earth Element Fractionation in Metamorphogenic Hydrothermal Calcite, Magnesite and Siderite. Mineral. Petrol. 1992, 45, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, W.P.; Fu, A.Z.; Zheng, B.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.J.; Zhao, Z.H. Study on trace element geochemical characteristics of pyrite in Yongxin gold deposit, Duobaoshan copper molybdenum gold mineralization belt. Gold 2024, 45, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, E.W.; Land, L.S. Subtidal Holocene Dolomite, Baffin Bay, Texas. J. Sediment. Res. 1972, 42, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.J.; Zhang, G.Q.; Shang, P.Q.; Qi, Y.Q. Ore-forming material sources of the Dachayuan uranium deposit, Zhejiang Province: Evidence from C-O and Sr-Nd isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2019, 35, 2817–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.B.; Xue, C.D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.H.; Deng, Y.; Li, Z.Q. Continental hydrothermal sedimentary origin of the Hexi strontium deposit in western Yunnan Province, SW China: Evidence from elemental and Sr-S isotopic compositions of celestines. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2024, 43, 1411–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Study on the Geochemical Characteristics of Gypsum Deposits in the Hexi Area of the Lanping Basin in Western Yunnan Province. Master’s Thesis, East China University of Technology, Nanchang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, P.; Mo, X.; Yu, X. Nd, Sr and Pb Isotopic Characteristics of the Alkaline-rich Porphyries in Western Yunnan and Its Compression Strike-slip Setting. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2002, 21, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.M.; Huang, X.; Zhong, D.L. Rock characteristics and genesis of Cenozoic alkali rich porphyry in western Yunnan. Sci. Geol. Sin. 1998, 33, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, K.; Zhao, F.F.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Peng, H.J.; Xia, Y.; Wang, R.Q.; Ren, K.F.; Gao, Y.; Yang, M.M.; Gong, J. Petrogenesis and metallogenic potential of Eocene alkaline porphyry in Xiaoqiaotou, western Yunnan: Evidence from mineralogy, geochemistry, and geochronology. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2025, 53, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Q.; Jie, G.H.; Masuda, A. Geochemistry of Cenozoic Basalt in Eastern China (II) Sr, Nd, Ce Isotope Composition. Geochemistry 1995, 24, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.R.; Shen, S.Y.; Mo, X.X.; Lu, F.X. Nd Sr Pb isotope system characteristics of materials from the ancient Tethys volcanic source area in the Sanjiang region. J Miner. Pet. 2003, 23, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.Y.; Mo, X.X.; Yu, X.H.; Dong, G.C.; He, Z.H.; Huang, X.F.; Li, X.W.; Jiang, L.L. Genesis and geodynamic settings of lamprophyres from Beiya, western Yunnan: Constraints from geochemistry, geochronology and Sr-Nd-b-Hf isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2014, 30, 3287–3300. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.J.; Gao, Y.B.; Zeng, R.; Chi, G.X.; Qing, H.R. Organic petrography and geochemistry of the giant Jinding deposit, Lanping basin, northwestern Yunnan, China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23, 2889–2900. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.J.; Gao, Y.B.; Chi, G.X.; Leach, D.L. Possible Former Oil-gas Reservoir in the Giant Jinding Pb-Zn Deposit, Lanping, NW-Yunnan:the Role in the Ore Accumulation. J. Earth Sci. Environ. 2009, 31, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Ding, T.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Tian, Y.; Wu, J.; Yan, J. The trace elemental and isotopic characteristics of gypsum and its significance in the Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan. J. Salt Lake Res. 2024, 32, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.J.; Guo, F.S. The geochemical characteristics and indicative significance of gypsum in Jinding lead-zinc mining area, Lanping Basin, western Yunnan Province. J. East China Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 41, 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y. Exploration of Geochemical Characteristics and Genesis of Vein Shaped Copper Rich Ore Body in Qingyangchang, Yongping, Western Yunnan. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.R.; Wen, H.J. Sulfur and lead isotope compositions and tracing of copper deposits on the western border of the Lanping Basin, Yunnan Province. Geochemistry 2012, 41, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.R.; Wen, H.J.; Zou, Z.C. Geology and geochemistry of the Kedengjian vein–type copper deposit in western Lanping basin. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2016, 35, 692–702. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.R.; Wen, H.J.; Zou, Z.C.; Du, S.J.; Gu, C.Y. Copper and sulfur isotopic characteristics of the Jinman–Liancheng vein–type copper deposit in the western Lanping Basin and its significance. Geochemistry 2023, 52, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollinson, H.R. Using Geochemical Data: Evaluation, Presentation, Interpretation; Longman Geochemistry Ser; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-582-06701-1. [Google Scholar]

- Machel, H.G.; Krouse, H.R.; Sassen, R. Products and Distinguishing Criteria of Bacterial and Thermochemical Sulfate Reduction. Appl. Geochem. 1995, 10, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. The gold Mineralization of the Cenozoic Alkali Rich Porphyry in Western Yunnan. Master’s thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, L. Alkali Rich Magmatic Activity and Gold Polymetallic Mineralization System in Northwest Yunnan. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Shao, S.X.; Liu, Z.H. Determination and application of the upper mantle lead composition in western Yunnan. Geol. Geochem. 2002, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Xie, Y.W.; Li, X.H.; Qiu, H.N.; Zhao, Z.H.; Liang, H.Y.; Zhong, S.L. Isotope Characteristics of Magma Rocks in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau: Petrogenesis and Structural Significance. Sci. China (Ser. D) 2000, 30, 493–498. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, X.H.; Mo, X.X.; Zhang, J.; Lv, B.X. Petrological and Geochemical Characteristics of Cenozoic Alkali-Rich Porphyries and Xenoliths Hosted in Western Yunnan Province. Geoscience 2004, 18, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger, R.W.; Cardozo, N.; Fisher, D. Structural Geology Algorithms: Vectors and Tensors in Structural Geology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo, N.; Allmendinger, R.W. Spherical Projections with OSXStereonet. Comput. Geosci. 2013, 51, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghfouri, S.; Rastad, E.; Borg, G.; Hosseinzadeh, M.R.; Movahednia, M.; Mahdavi, A.; Mousivand, F. Metallogeny and Temporal–Spatial Distribution of Sediment-Hosted Stratabound Copper (SSC-Type) Deposits in Iran; Implications for Future Exploration. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 127, 103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarasvandi, A.; Pourkaseb, H.; Fatemi, A.-K.; Fereydouni, Z.; Ghasemi, M. Geology and Geochemistry of Cu Mineralization in the Dehmadan and DarreYas indices, Charmahal va Bakhtiari Province. JAAG 2020, 10, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaraien, H.; Shahabpour, J.; Aminzadeh, B. Metallogenesis of the Sediment-Hosted Stratiform Cu Deposits of the Ravar Copper Belt (RCB), Central Iran. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 81, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asael, D.; Matthews, A.; Bar-Matthews, M.; Halicz, L. Copper Isotope Fractionation in Sedimentary Copper Mineralization (Timna Valley, Israel). Chem. Geol. 2007, 243, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, R.W.R. An Unconformity in the Corocoro Basin, Bolivia, and Its Relation to Copper Mineralization. Econ. Geol. 1966, 61, 962–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breit, G.N.; Meunier, J.-D. Fluid Inclusion, δ18O, and 87Sr/86Sr Evidence for the Origin of Fault-Controlled Copper Mineralization, Lisbon Valley, Utah, and Slick Rock District, Colorado. Econ. Geol. 1990, 55, 884–891. [Google Scholar]

- Subías, I.; Fanlo, I.; Mateo, E.; García-Veigas, J. A Model for the Diagenetic Formation of Sandstone-Hosted Copper Deposits in Tertiary Sedimentary Rocks, Aragón (NE Spain): S/C Ratios and Sulphur Isotope Systematics. Ore Geol. Rev. 2003, 23, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utrilla, R.; Pierre, C.; Orti, F.; Pueyo, J.J. Oxygen and Sulphur Isotope Compositions as Indicators of the Origin of Mesozoic and Cenozoic Evaporites from Spain. Chem. Geol. 1992, 102, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K.; Symons, D.T.A. Palaeomagnetism of the Howards Pass Zn-Pb Deposits, Yukon, Canada: Howards Pass Zn-Pb Deposits. Geophys. J. Int. 2012, 190, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.A.; Slack, J.F.; Dumoulin, J.A.; Kelley, K.D.; Falck, H. Sulfur Isotopes of Host Strata for Howards Pass (Yukon–Northwest Territories) Zn-Pb Deposits Implicate Anaerobic Oxidation of Methane, Not Basin Stagnation. Geology 2018, 46, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torremans, K.; Kyne, R.; Doyle, R.; Güven, J.F.; Walsh, J.J. Controls on Metal Distributions at the Lisheen and Silvermines Deposits: Insights into Fluid Flow Pathways in Irish-Type Zn-Pb Deposits. Econ. Geol. 2018, 113, 1455–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, C.J. The Ballynoe Stratiform Barite Deposit, Silvermines, County Tipperary, Ireland. Minerals 2024, 14, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large, D.; Walcher, E. The Rammelsberg Massive Sulphide Cu-Zn-Pb-Ba-Deposit, Germany: An Example of Sediment-Hosted, Massive Sulphide Mineralisation. Miner. Depos. 1999, 34, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltrin, L.; Oliver, N.H.S.; Kelso, I.J.; King, S. Basement Metal Scavenging during Basin Evolution:Cambrian and Proterozoic Interaction at the Century ZnPbAg Deposit, Northern Australia. J. Geochem. Explor. 2003, 78–79, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltrin, L.; McLellan, J.G.; Oliver, N.H.S. Modelling the Giant, Zn–Pb–Ag Century Deposit, Queensland, Australia. Comput. Geosci. 2009, 35, 108–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Feng, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y. Three-Dimensional Numerical Modeling of Salinity Variations in Driving Basin-Scale Fluid Flow Related to the Formation of the Mount Isa SEDEX Deposits, Northern Australia. J. Geochem. Explor. 2009, 101, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnall, J.M.; Gleeson, S.A.; Stern, R.A.; Newton, R.J.; Poulton, S.W.; Paradis, S. Open System Sulphate Reduction in a Diagenetic Environment – Isotopic Analysis of Barite (δ34S and δ18O) and Pyrite (δ34S) from the Tom and Jason Late Devonian Zn–Pb–Ba Deposits, Selwyn Basin, Canada. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 180, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, C.; Creus, P.; Neal, S. Geology of the Shear Zone Hosted Dugald River Zn-Pb-Ag Deposit, Mt Isa Inlier, NW QLD. In Proceedings of the 3rd AEGC: Geosciences for a Sustainable World, Online, 13–17 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H.D.; Hutcheon, I. Geochemistry, Mineralogy, and Geology of the Jason Pb-Zn Deposits, Macmillan Pass, Yukon, Canada. Econ. Geol. 1985, 80, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.E. Biogenic and Thermogenic Sulfate Reduction in the Sullivan Pb–Zn–Ag Deposit, British Columbia (Canada): Evidence from Micro-Isotopic Analysis of Carbonate and Sulfide in Bedded Ores. Chem. Geol. 2004, 204, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senol, N.S.; Gregory, D.D.; Mukherjee, I.; Román, N.; Kyne, R.; Boucher, K.S. Testing Pyrrhotite Trace Element Chemistry as a Vector Towards the Mineralization in the Sullivan Deposit, B.C. Minerals 2025, 15, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, E. The Importance of Structural Mapping in Ore Deposits—A New Perspective on the Howard’s Pass Zn-Pb District, Northwest Territories, Canada. Econ. Geol. 2017, 112, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, R.D.; Bailes, R.J. Stratiform Lead-Zinc Sulfides, Mudflows, Turbidites: Devonian Sedimentation along a Submarine Fault Scarp of Extensional Origin, Jason Deposit, Yukon Territory, Canada. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1987, 98, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.A.; Ethier, V.G. Environment of Deposition of the Sullivan Orebody. Mineral. Depos. 1983, 18, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G. Microstructural Evidence for an Epigenetic Origin of a Proterozoic Zinc-Lead-Silver Deposit, Dugald River, Mount Isa Inlier, Australia. Mineralium Deposita 1997, 32, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.J. A Review of Fluid Inclusion Constraints on Mineralization in the Irish Ore Field and Implications for the Genesis of Sediment-Hosted Zn-Pb Deposits. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, A.L.; Hollis, S.P.; Menuge, J.F.; Lyons, C.; Piercey, S.J.; Boyce, A.J.; Slezak, P.; Torremans, K.; Güven, J. Evidence for Metal Sources, Fluid-Mixing Processes, and S Isotope Recycling within the Feeder Zone of an Irish Type Zn-Pb Deposit. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 182, 106660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, M.; Röhner, M.; Cook, N.J.; Gilbert, S.; Ciobanu, C.L.; Güven, J.F. Mineralogy, Mineral Chemistry, and Genesis of Cu-Ni-As-Rich Ores at Lisheen, Ireland. Miner Deposita. 2025, 60, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Wang, J.B.; Xiao, R.G.; Chen, X.Z. Metallogenesis of Continental Hydrothermal Sedimentation in Western Yunnan Region. Uranium Geol. 1993, 9, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J.; Li, C.Y.; Pan, J.Y.; Liu, X.F.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.P. Ore-Forming Material Sources of the Copper Deposits from Sandstone and Shale in Lanping—Simao Basin, Western Yunnan and Their Genetic Implications. Miner. Explor. 2000, 36, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, R. Geology, Fluid Inclusions, and Isotopic Geochemistry of the Jinman Sediment-Hosted Copper Deposit in the Lanping Basin, China. Resour. Geol. 2017, 67, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, D.L.; Sangster, D.F.; Kelley, K.D.; Large, R.R.; Garven, G.; Allen, C.R.; Gutzmer, J.; Walters, S. Sediment-Hosted Lead-Zinc Deposits: A Global Perspective; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Bai, X.Z.; Zhang, C.Y.; Tang, Y. Geochemistry of ore-forming fluids in Baiyangping ore field, Yunnan and its geological significance. Acta Mineral. Sin. 2009, 29, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Fu, W.M.; Li, L. The Material Origin of the Regional Metallogenesis of Cu Deposits in Red Beds of West Yunnan. Yunnan Geol. 1997, 16, 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J.; Li, C.Y.; Pan, J.Y.; Hu, R.Z.; Liu, X.F.; Zhang, Q. Isotopic Geochemistry of Copper Deposits in Sandstone and Shale of Lanping-Simao Basin, Western Yunnan. Miner. Depos. 2000, 19, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.G.; Chen, H.Q.; Shuai, K.Y.; Yan, Z.F. Mineralization of Jinman Copper Deposit in Mesozoic Sedimentary Rocks in Lanping, Yunnan Province. Geoscience 1994, 8, 490–496. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wen, H.; Qiu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Du, S.; Wu, S. Spatial–Temporal Evolution of Ore-Forming Fluids and Related Mineralization in the Western Lanping Basin, Yunnan Province, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 67, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.B.; Li, Z.Y. Geochemical Characteristics and Source of Ore-Forming Fluid for Jinman Copper Deposit in Western Yunnan Province, China. Acta Mineral. Sin. 1998, 18, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.J.; Chen, Y.C.; Wang, D.H.; Yang, J.M.; Yang, W.G.; Zeng, R. Geology and He, Ne, Xe Isotope Compositions and Metallogenic Age of Jinding and Baiyangping Deposits in Northwestern Yunnan. Sci. China (Ser. D) 2003, 33, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Characteristics and Evolution of Ore-Forming Fluids in Pb Zn Cu Ag Deposits in Lanping Basin. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J.; Li, C.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.Y.; Liu, Y.P.; Liu, X.F.; Liu, S.R.; Yang, W.G. Wood structure and its genetic significance in the Jinman copper deposit in western Yunnan. Sci. China (Ser. D) 2001, 44, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.C.; Xie, Q.Q.; Lu, S.M.; Chen, T.H.; Huang, Z.; Yue, S.C. Fluid inclusion characteristics of copper deposits on the western border of Lanping Basin, Yunnan Province. Acta Mineral. Sin. 2005, 25, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.G.; Yu, X.H.; Li, W.C.; Dong, F.L.; Mo, X.X. The characteristics of metallogenic fluids and metallogenic mechanism in baiyangping silver and polymetallic mineralization concentration area in yunnan province. Geoscience 2003, 17, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.R.; Wen, H.J.; Qin, C.J.; Wang, J.S. Fluid inclusion and stable isotopes study of Liancheng Cu-Mo polymetallic deposit in Lanping basin, Yunnan Province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2012, 28, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.R.; Wen, H.J.; Zou, Z.C.; Du, S.J. Origin of CO2-rich ore-forming fluids in the vein-type Cu deposits in western Lanping Basin, Yunnan: Evidence from He and Ar isotopes. Geochimica 2015, 44, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.R.; Wen, H.J.; Zou, Z.C. Ore-Forming Fluid Characteristics of the Jinman Vein-Type Copper Deposits in the Western Lanping Basin and Its Metallogenic Significance. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2017, 47, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Hou, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, T.; Xue, C. Fluid Inclusion and Isotopic Constraints on the Origin of Ore-forming Fluid of the Jinman–Liancheng Vein Cu Deposit in the Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan, China. Geofluids 2016, 16, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Sun, X. Field Emission from One-Dimensional Nanostructured Zinc Oxide. IJNT 2004, 1, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Chi, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Qing, H. Two Fluid Systems in the Lanping Basin, Yunnan, China — Their Interaction and Implications for Mineralization. J. Geochem. Explor. 2006, 89, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etschmann, B.E.; Liu, W.; Testemale, D.; Müller, H.; Rae, N.A.; Proux, O.; Hazemann, J.L.; Brugger, J. An in Situ XAS Study of Copper(I) Transport as Hydrosulfide Complexes in Hydrothermal Solutions (25–592 °C, 180–600 Bar): Speciation and Solubility in Vapor and Liquid Phases. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 4723–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Study on the Genesis of Jinman Liancheng Vein Copper Deposit in Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sillitoe, R.H.; Perello, J.; Garcia, A. Sulfide-Bearing Veinlets Throughout the Stratiform Mineralization of the Central African Copperbelt: Temporal and Genetic Implications. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailteux, J.; Binda, P.L.; Katekesha, W.M.; Kampunzu, A.B.; Intiomale, M.M.; Kapenda, D.; Kaunda, C.; Ngongo, K.; Tshiauka, T.; Wendorff, M. Lithostratigraphical Correlation of the Neoproterozoic Roan Supergroup from Shaba (Zaire) and Zambia, in the Central African Copper-Cobalt Metallogenic Province. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 1994, 19, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, H.; Kisters, A.; Basson, I.J. Deformation, Alteration and Implicit 3D Geomodelling of Deposit-Scale Controls of Vein-Hosted Copper Mineralization of the Frontier Mine, Democratic Republic of Congo. Min. Depos. 2025, 60, 1409–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, M.D.; Hitzman, M.W.; Wood, D.; Humphrey, J.D.; Wendlandt, R.F. Geology of the Fishtie Deposit, Central Province, Zambia: Iron Oxide and Copper Mineralization in Nguba Group Metasedimentary Rocks. Min. Depos. 2015, 50, 717–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrtzman, M.W.; Broughton, D.; Selley, D.; Woodhead, J.; Wood, D.; Bull, S. The Central African CopperbeltDiverse Stratigraphic, Structural, and Temporal Settings in the World’s Largest Sedimentary Copper District; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, CO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kampunzu, A.B.; Cailteux, J. Tectonic Evolution of the Lufilian Arc (Central Africa Copper Belt) During Neoproterozoic Pan African Orogenesis. Gondwana Res. 1999, 2, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, S.; Muchez, P.; Vets, J.; Fernandez-Alonzo, M.; Tack, L. Multiphase Origin of the Cu–Co Ore Deposits in the Western Part of the Lufilian Fold-and-Thrust Belt, Katanga (Democratic Republic of Congo). J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2006, 46, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitzman, M.W.; Broughton, D.W. Discussion: “Age of the Zambian Copperbelt” by Sillitoe et al. (2017) Mineralium Deposita. Min. Depos. 2017, 52, 1273–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailteux, J.L.H.; Kampunzu, A.B.; Lerouge, C.; Kaputo, A.K.; Milesi, J.P. Genesis of Sediment-Hosted Stratiform Copper–Cobalt Deposits, Central African Copperbelt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2005, 42, 134–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Kisters, A. Regional and Local Controls of Hydrothermal Fluid Flow and Gold Mineralization in the Sheba and Fairview Mines, Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 144, 104805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treagus, S.H.; Fletcher, R.C. Controls of Folding on Different Scales in Multilayered Rocks. J. Struct. Geol. 2009, 31, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, D.W.; Podladchikov, Y.Y. Fold Amplification Rates and Dominant Wavelength Selection in Multilayer Stacks. Philos. Mag. 2006, 86, 3409–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noten, K.; Muchez, P.; Sintubin, M. Stress-State Evolution of the Brittle Upper Crust during Compressional Tectonic Inversion as Defined by Successive Quartz Vein Types (High-Ardenne Slate Belt, Germany). JGS 2011, 168, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Li, Z.M.; Liu, Y.P.; Li, C.Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, M.Q.; Yang, W.G.; Yang, A.P.; Sang, H.Q. The metallogenic age of Jinman vein copper deposit, Western Yunnan. Geoscience 2003, 17, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.C.; Huang, Z.; Xie, Q.Q.; Yue, S.C.; Liu, Y. Ar-Ar Isotopic Ages of Jinman and Shuixie Copper Polymetallic Deposits in Yunnan Province, and Their Geological Implications. Geol. J. China Univ. 2004, 10, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.H.; Song, Y.C.; Hou, Z.Q.; Wang, X.H.; Yang, Z.S.; Yang, T.N.; Liu, Y.X.; Jiang, Y.F.; Pan, X.F.; Zhang, H.R. Re-Os dating of molybdenite from Liancheng vein copper deposit in Lanping basin and its geological significance. Miner. Depos. 2009, 28, 413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.R.; Wen, H.J.; Qiu, Y.Z.; Zou, Z.C. Ages of the Cu–Ag–Pb–Zn Polymetallic Deposits in Western Lanping Basin, Yunan Province. Geol. J. China Univ. 2016, 22, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Song, Y.; Deng, T.; Zhuang, L.; Wu, W. Mass Transfer during Hydrothermal Bleaching Alteration of Red Beds in the Lanping Basin, SW China: Implications for Regional Cu(–Co) and Pb-Zn Mineralization. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 163, 105744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, I.F.; Barton, M.D.; Thorson, J.P. Characteristics of Cu and U-V Deposits in the Paradox Basin (Colorado Plateau) and Associated Alteration. Soc. Econ. Geol. 2018, 59, 74–102. [Google Scholar]

- Garden, I.R.; Guscott, S.C.; Burley, S.D.; Foxford, K.A.; Walsh, J.J.; Marshall, J. An Exhumed Palaeo-hydrocarbon Migration Fairway in a Faulted Carrier System, Entrada Sandstone of SE Utah, USA. Geofluids 2001, 1, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.A.; Parry, W.T.; Bowman, J.R. Diagenetic Hematite and Manganese Oxides and Fault-Related Fluid Flow in Jurassic Sandstones, Southeastern Utah. Bulletin 2000, 84, 1281–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Type | Homogenization Temp. (°C) | Homogenization Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPZ-1 | Three-Phase | 251.6 | L + L + V → L |

| Three-Phase | 240.3 | L + L + V → L | |

| Three-Phase | 233.8 | L + L + V → L | |

| Three-Phase | 233.8 | L + L + V → L | |

| SPZ-3 | Liquid-Rich Phase | 243.8 | L + V → L |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 221.9 | L + V → L | |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 217.8 | L + V → L | |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 231.2 | L + V → L | |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 229.2 | L + V → L | |

| HMG—8 | Liquid-Rich Phase | 232.8 | L + V → L |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 240.5 | L + V → L | |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 251.2 | L + V → L | |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 245.2 | L + V → L | |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 237.8 | L + V → L | |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 252.8 | L + V → L | |

| Liquid-Rich Phase | 243.6 | L + V → L |

| Sample | HMG-3-2 | HMG-2 | HMG-1-2 | HMG2-3 | HMG2-5 | HMG2-8 | HMG-4-2 | HMG-7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | |||||||||

| La (μg/g) | 1.49 | 1.15 | 0.8 | 2.48 | 1.4 | 0.89 | 3 | 1.31 | |

| Ce (μg/g) | 6.31 | 5.67 | 3.98 | 9.84 | 6.46 | 4.26 | 11.3 | 5.8 | |

| Pr (μg/g) | 1.43 | 1.3 | 1.03 | 2.04 | 1.52 | 1 | 2.35 | 1.28 | |

| Nd (μg/g) | 9.9 | 9.01 | 8.34 | 13.4 | 10.6 | 7.05 | 14.2 | 8.55 | |

| Sm (μg/g) | 6.86 | 5.44 | 6.28 | 7.34 | 6.3 | 5.31 | 7.53 | 5.56 | |

| Eu (μg/g) | 5 | 1.63 | 1.93 | 2.33 | 1.77 | 1.48 | 2.56 | 1.65 | |

| Gd (μg/g) | 9.5 | 7.17 | 7.77 | 9.41 | 7.8 | 8.15 | 9.03 | 7.53 | |

| Tb (μg/g) | 1.63 | 1.29 | 1.18 | 1.53 | 1.26 | 1.44 | 1.5 | 1.34 | |

| Dy (μg/g) | 9.95 | 8 | 6.69 | 9.28 | 7.26 | 9.13 | 8.85 | 8.85 | |

| Ho (μg/g) | 1.77 | 1.5 | 1.18 | 1.73 | 1.28 | 1.73 | 1.6 | 1.67 | |

| Er (μg/g) | 4.96 | 3.99 | 3.04 | 4.59 | 3.49 | 4.63 | 4.42 | 4.75 | |

| Tm (μg/g) | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.6 | 0.65 | |

| Yb (μg/g) | 4.11 | 3.53 | 2.81 | 4.14 | 2.97 | 3.96 | 3.81 | 3.87 | |

| Lu (μg/g) | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.5 | 0.51 | |

| Y (μg/g) | 45.7 | 36 | 29.9 | 43.1 | 33.3 | 44.8 | 40 | 42.9 | |

| w(Y/Ho) | 25.82 | 24.00 | 25.34 | 24.91 | 26.02 | 25.90 | 25.00 | 25.69 | |

| Ce/Ce* | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.87 | |

| Eu/Eu* | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.30 | 1.32 | 1.19 | 1.06 | 1.46 | 1.20 | |

| ∑REE | 106.97 | 86.75 | 75.76 | 112.40 | 86.24 | 94.96 | 111.25 | 96.22 | |

| Serial Number | Sample | Mineral | 87Sr/86Sr |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HMG-6 | Siderite | 0.710949 |

| 2 | HMG-1-2 | Dolomite | 0.711341 |

| 3 | HMG-2 | Dolomite | 0.711707 |

| 4 | HMG-2-3 | Dolomite | 0.711494 |

| 5 | HMG-2-5 | Dolomite | 0.711667 |

| 6 | HMG-2-8 | Dolomite | 0.711164 |

| 7 | HMG-3-2 | Dolomite | 0.711651 |

| 8 | HMG-4-2 | Dolomite | 0.711741 |

| 9 | HMG-7 | Dolomite | 0.711864 |

| 10 | SPZ-5 | Calcite | 0.711743 |

| Sample | Mineral | δ34SV-CDT (‰) | 206Pb/204Pb | 207Pb/204Pb | 208Pb/204Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPZ-1 | Chalcopyrite | −6.9 | 18.663 | 15.614 | 38.755 |

| SPZ-1 | Chalcocite | −5.7 | 18.515 | 15.561 | 38.648 |

| SPZ-3 | Chalcopyrite | −3 | 18.67 | 15.606 | 38.825 |

| SPZ-4 | Chalcopyrite | −0.6 | 18.665 | 15.637 | 38.833 |

| SPZ-5 | Bornite | −4.1 | 18.437 | 15.475 | 38.361 |

| SPZ-5 | Chalcopyrite | −1.3 | 18.405 | 15.453 | 38.35 |

| SPZ-6 | Chalcocite | 2.8 | 18.374 | 15.414 | 38.244 |

| SPZ-6 | Chalcopyrite | 9.4 | - | - | - |

| HMG-1-2 | Chalcopyrite | −11.5 | 18.691 | 15.689 | 39.025 |

| HMG2 | Chalcopyrite | −6.8 | 18.641 | 15.675 | 38.931 |

| HMG-3-2 | Chalcopyrite | - | 18.656 | 15.629 | 38.822 |

| HMG-3-2 | Pyrite | 0.1 | - | - | - |

| HMG-4-1 | Chalcopyrite | −1.6 | - | - | - |

| HMG-4-2 | Chalcopyrite | −11.2 | 18.605 | 15.627 | 38.836 |

| HMG-7 | Chalcopyrite | −8.7 | 18.602 | 15.602 | 38.787 |

| HMG-8 | Chalcopyrite | - | 18.435 | 15.525 | 38.459 |

| HMG-8 | Pyrite | 0.9 | - | - | - |

| HMG2-3 | Chalcopyrite | −9.1 | 18.484 | 15.519 | 38.569 |

| HMG2-5 | Chalcopyrite | −11.7 | 18.558 | 15.588 | 38.68 |

| HMG2-5 | Pyrite | −11.2 | 18.59 | 15.608 | 38.762 |

| HMG2-8 | Chalcopyrite | −5.3 | 18.455 | 15.529 | 38.551 |

| LP14006-5 | Chalcopyrite | 1.1 | 18.587 | 15.635 | 38.815 |

| LP14006-6 | Chalcopyrite | −1.4 | 18.637 | 15.664 | 38.947 |

| LP14006-7 | Chalcopyrite | −1.5 | 18.622 | 15.653 | 38.912 |

| LP14006-9 | Chalcopyrite | −2.5 | 18.661 | 15.672 | 38.99 |

| Point | Joint Attitude | σ1 (°) | σ2 (°) | σ3 (°) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | Dip Direction | Dip Angle | |

| HTQ2307 | 308 | 45 | 7 | 58 | 58 | 13 | 315 | 45 | 160 | 42 |

| HTQ2307-1 | 268 | 67 | 41 | 65 | 153 | 48 | 336 | 42 | 245 | 1 |

| HTQ2309 | 95 | 64 | 168 | 71 | 220 | 6 | 119 | 62 | 313 | 27 |

| HTQ2315 | 324 | 65 | 107 | 61 | 213 | 58 | 38 | 32 | 306 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, T. Discussion on the Genesis of Vein-Type Copper Deposits in the Northern Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan. Minerals 2026, 16, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010033

Chen Z, Wang X, Song Y, Liu T. Discussion on the Genesis of Vein-Type Copper Deposits in the Northern Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhangyu, Xiaohu Wang, Yucai Song, and Teng Liu. 2026. "Discussion on the Genesis of Vein-Type Copper Deposits in the Northern Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan" Minerals 16, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010033

APA StyleChen, Z., Wang, X., Song, Y., & Liu, T. (2026). Discussion on the Genesis of Vein-Type Copper Deposits in the Northern Lanping Basin, Western Yunnan. Minerals, 16(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010033