Classification and Depositional Modeling of the Jurassic Organic Microfacies in Northern Iraq Based on Petrographic and Geochemical Characterization: An Approach to Hydrocarbon Source Rock Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

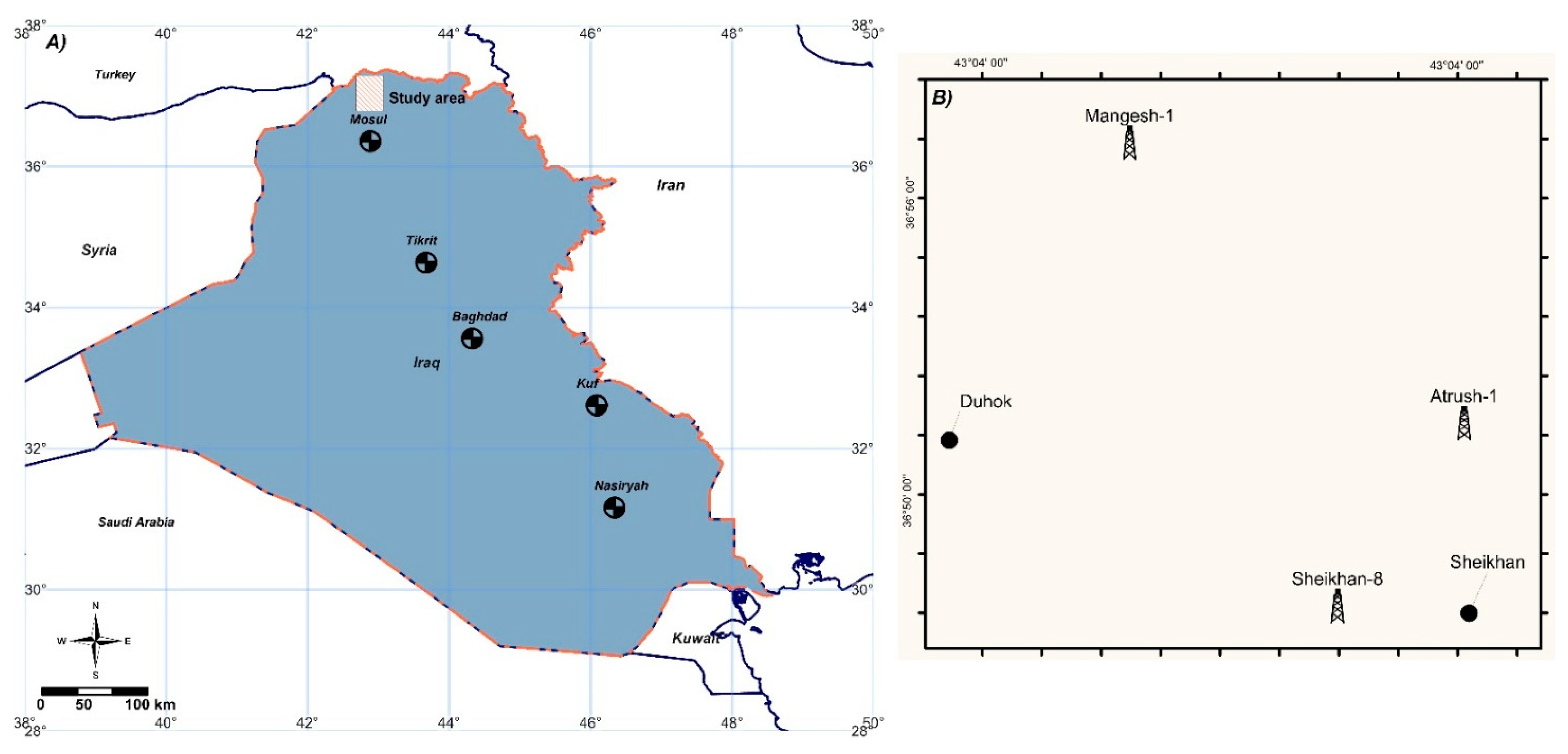

2. Geological Framework and Tectonic Evolution of Iraqi Kurdistan

2.1. Structural and Tectonic Framework

- Late Cretaceous compression inverted Neo-Tethys rift structures.

- Eocene–Miocene Arabian–Eurasian collision caused further inversion, folding, and thrusting.

- Neogene shortening shaped the current fold-and-thrust belt.

2.2. Petroleum System Context and Source Rock Relevance

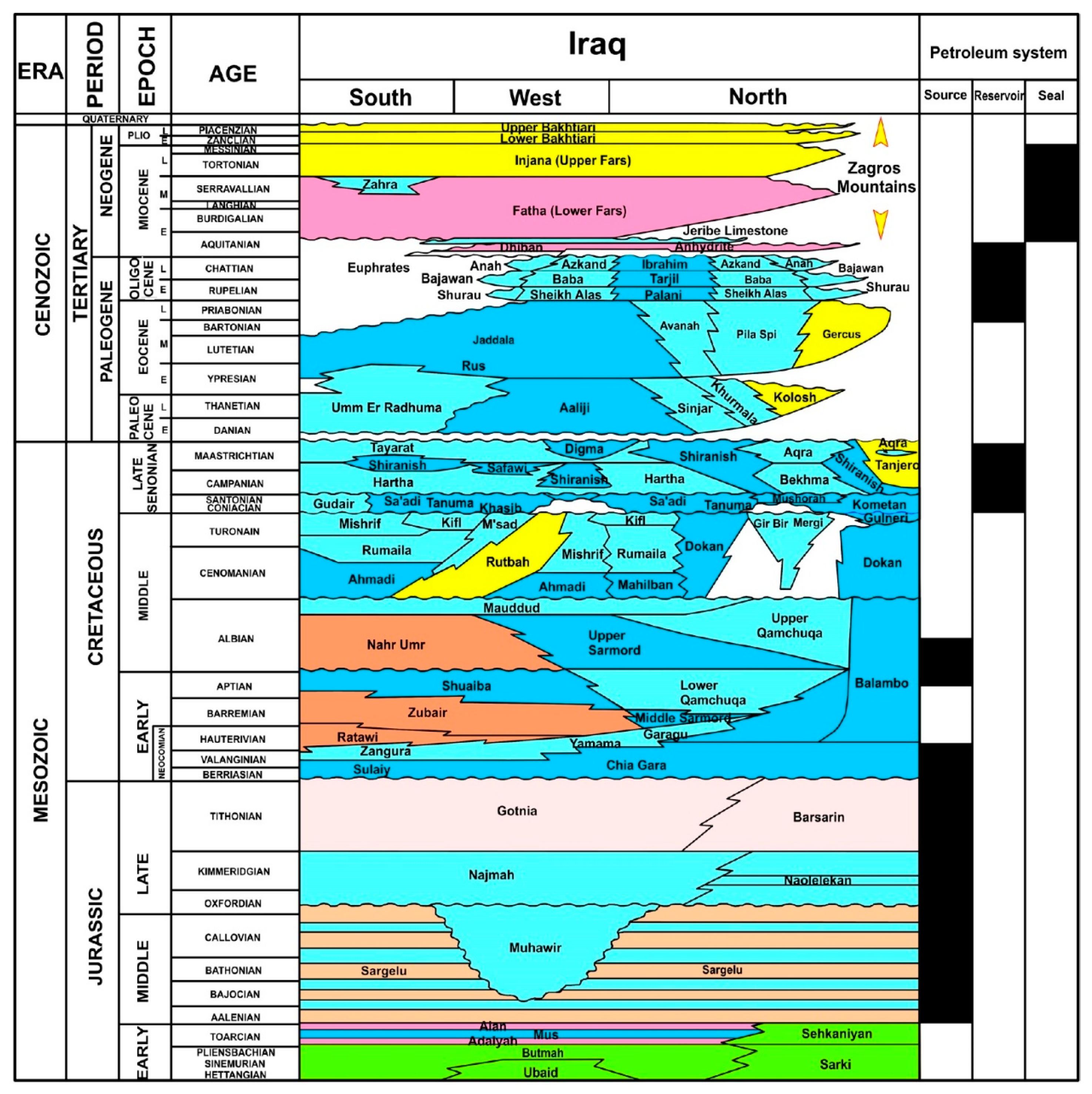

2.3. Stratigraphic Overview of Target Jurassic Formations

- Naokelekan Formation (Callovian–Upper Oxfordian): Type section is located near Naokelekan Village [17]. It conformably overlies the Sargelu and underlies the Barsarin [32,38,39]. The upper contact is often marked by a detrital, ferruginous horizon [40,41]. Subsurface lithology includes argillaceous limestone, limestone, and calcareous claystone.

- Barsarin Formation (Kimmeridgian–Oxfordian): Type section is near Barsarin Village (van Bellen et al., 1959 [17]). It comprises limestone with laminated dolomitic limestone, argillaceous, brecciated beds. It conformably overlies the Naokelekan (often with detrital horizon) and underlies Chia Gara [17,40,41].

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Sample Preparation Procedures

3.2. Organic Petrography

3.3. Screening Organic Geochemical Analysis

3.4. Molecular Organic Geochemical Analysis

4. Results

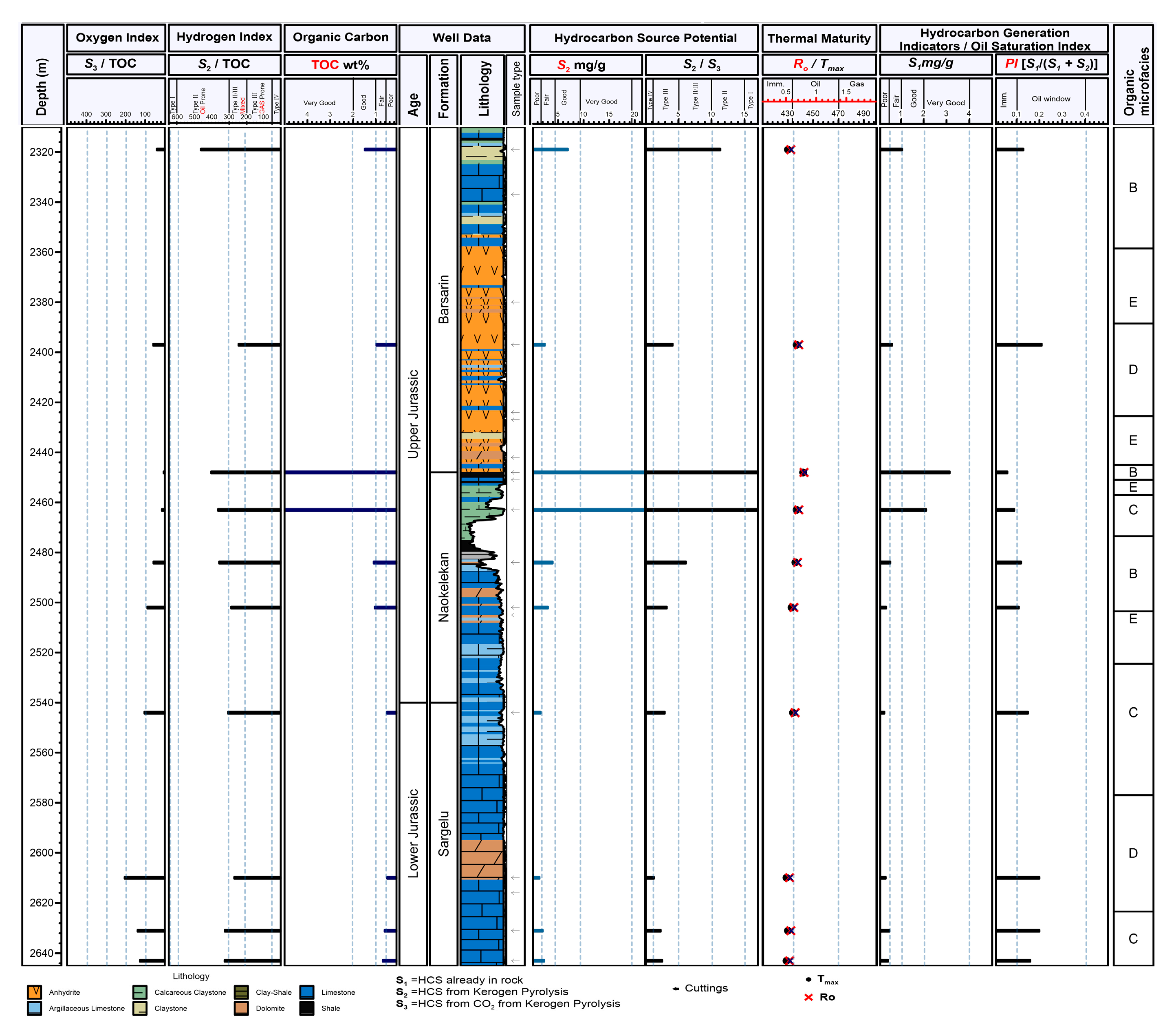

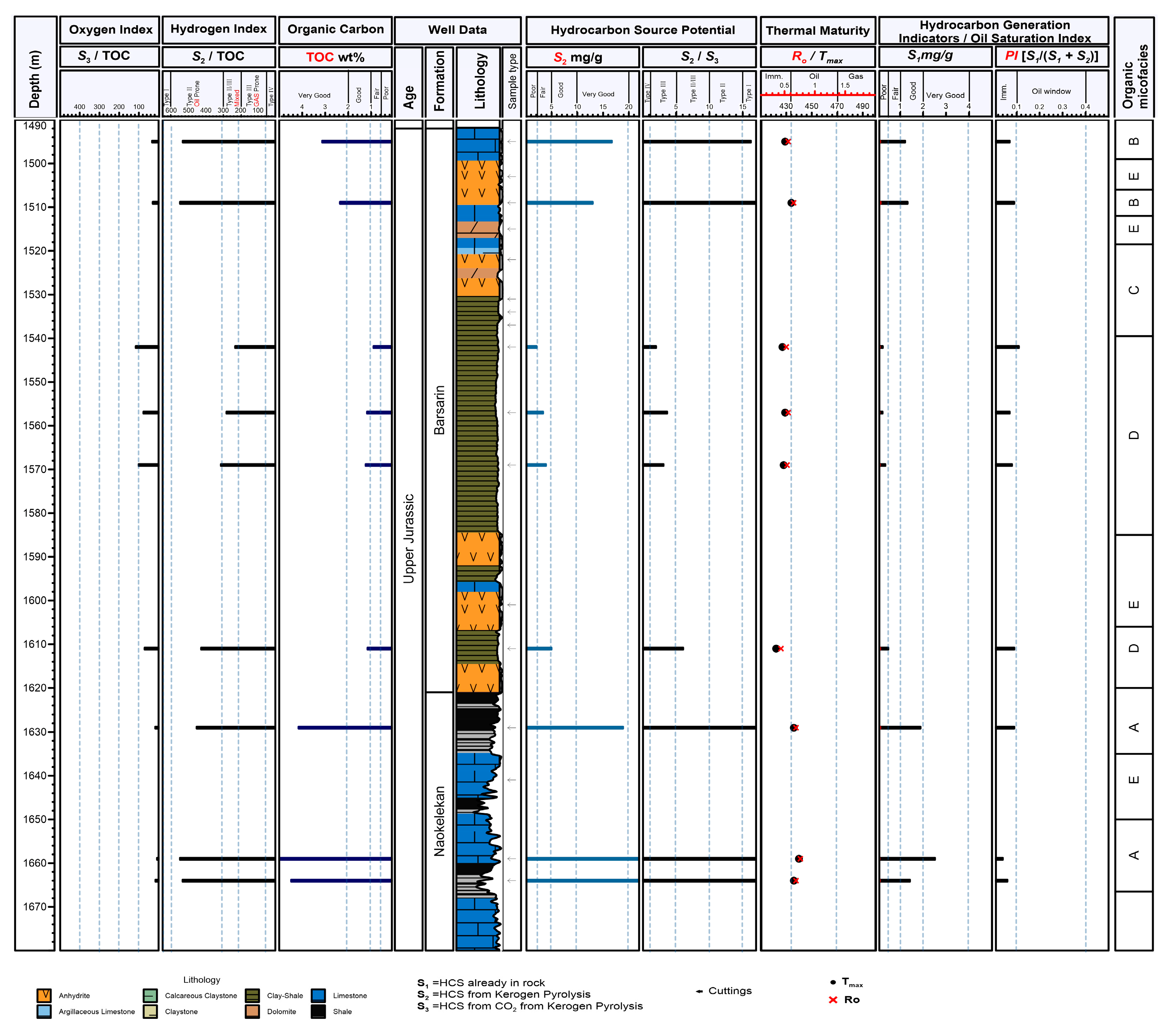

4.1. Lithological Characteristics and Electric Well Log Response

4.2. Organic Microfacies Classification and Distribution Model

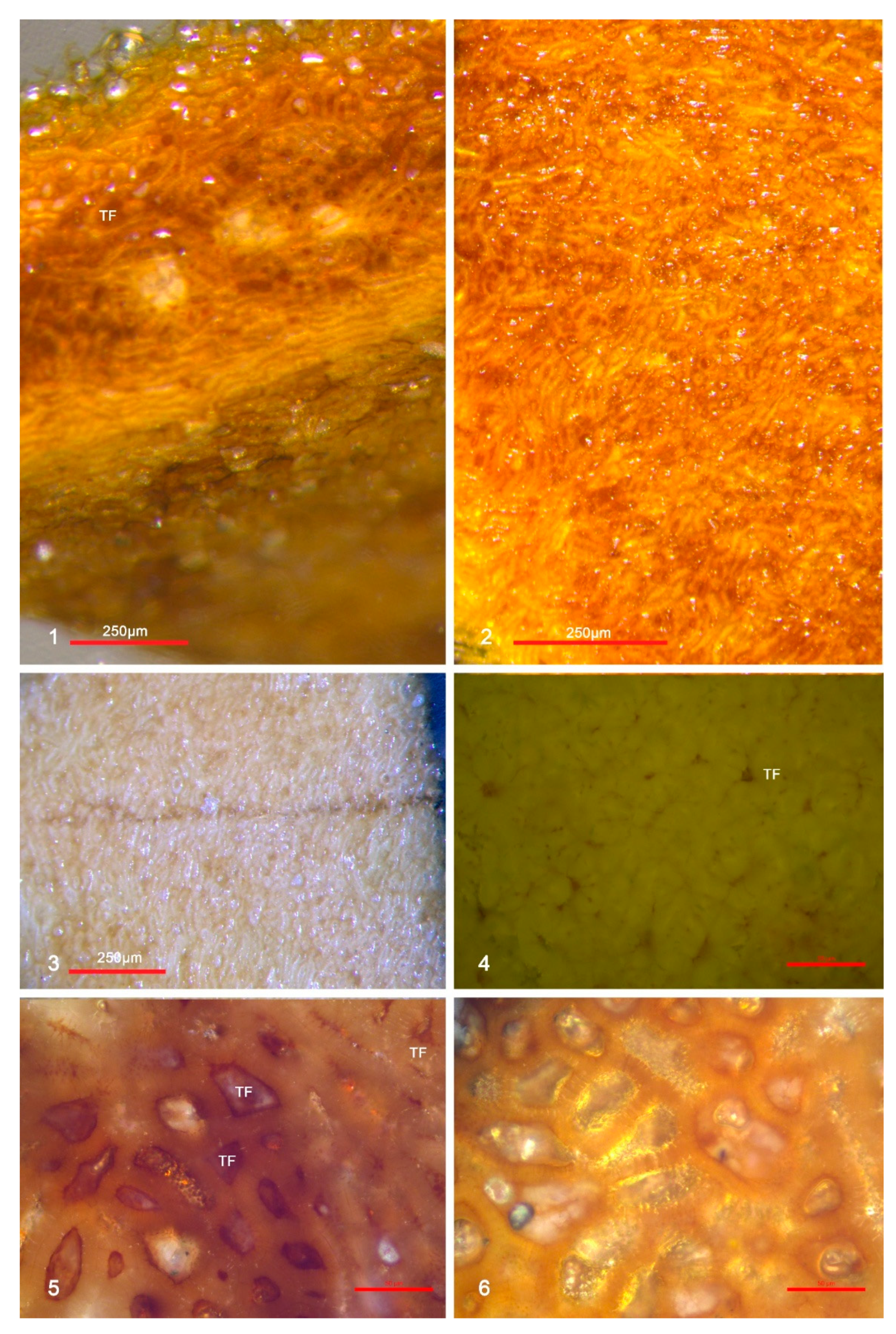

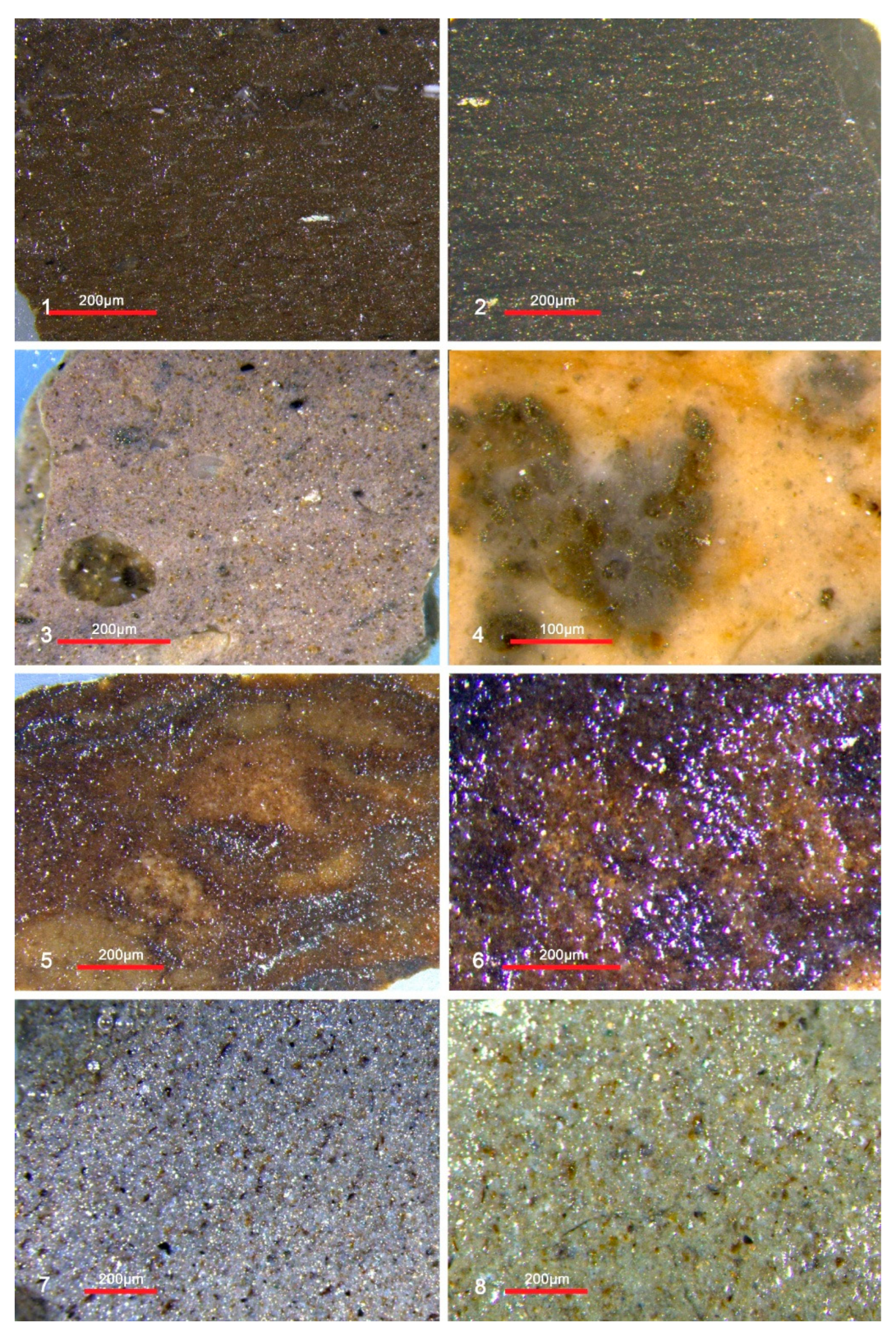

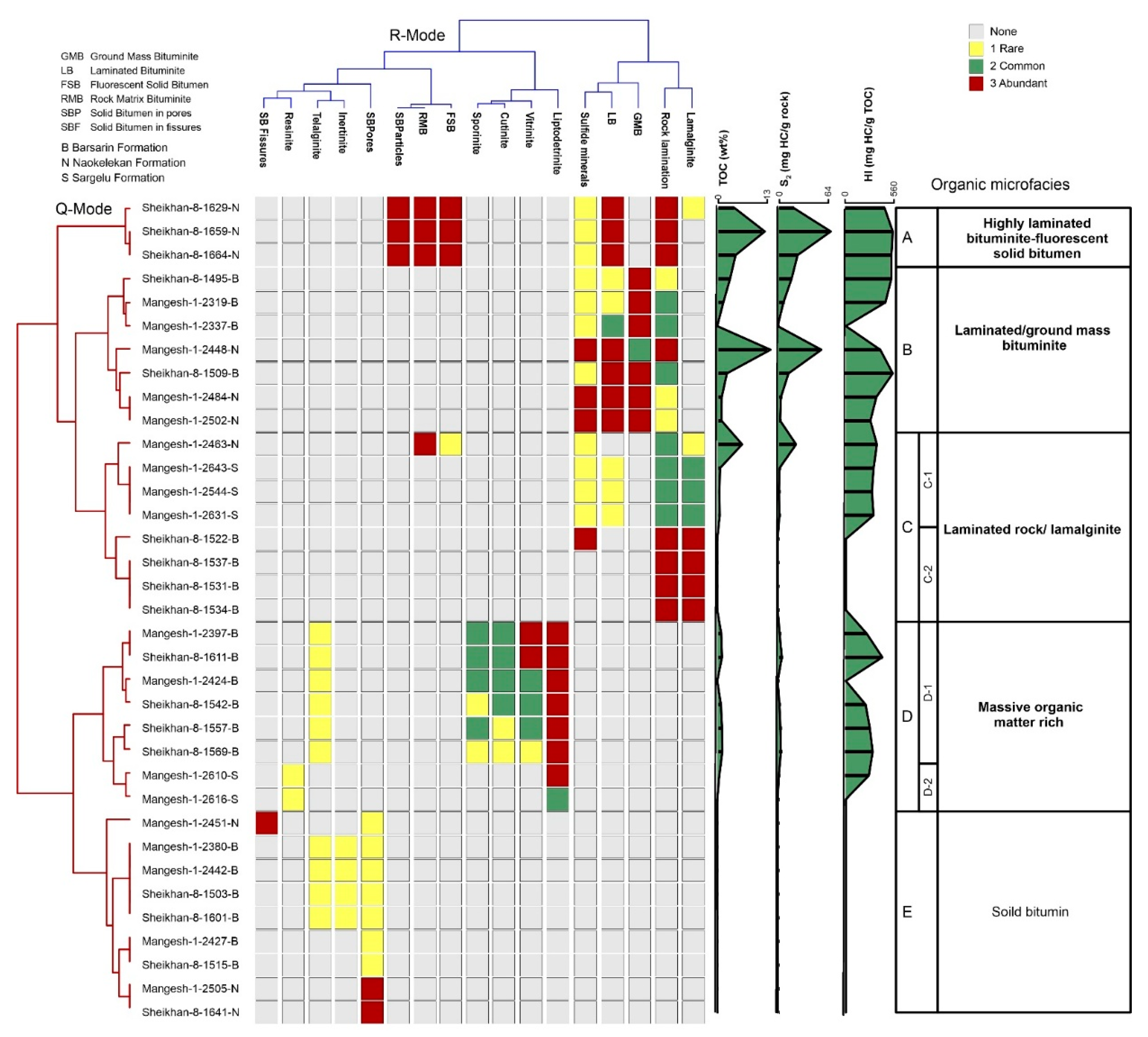

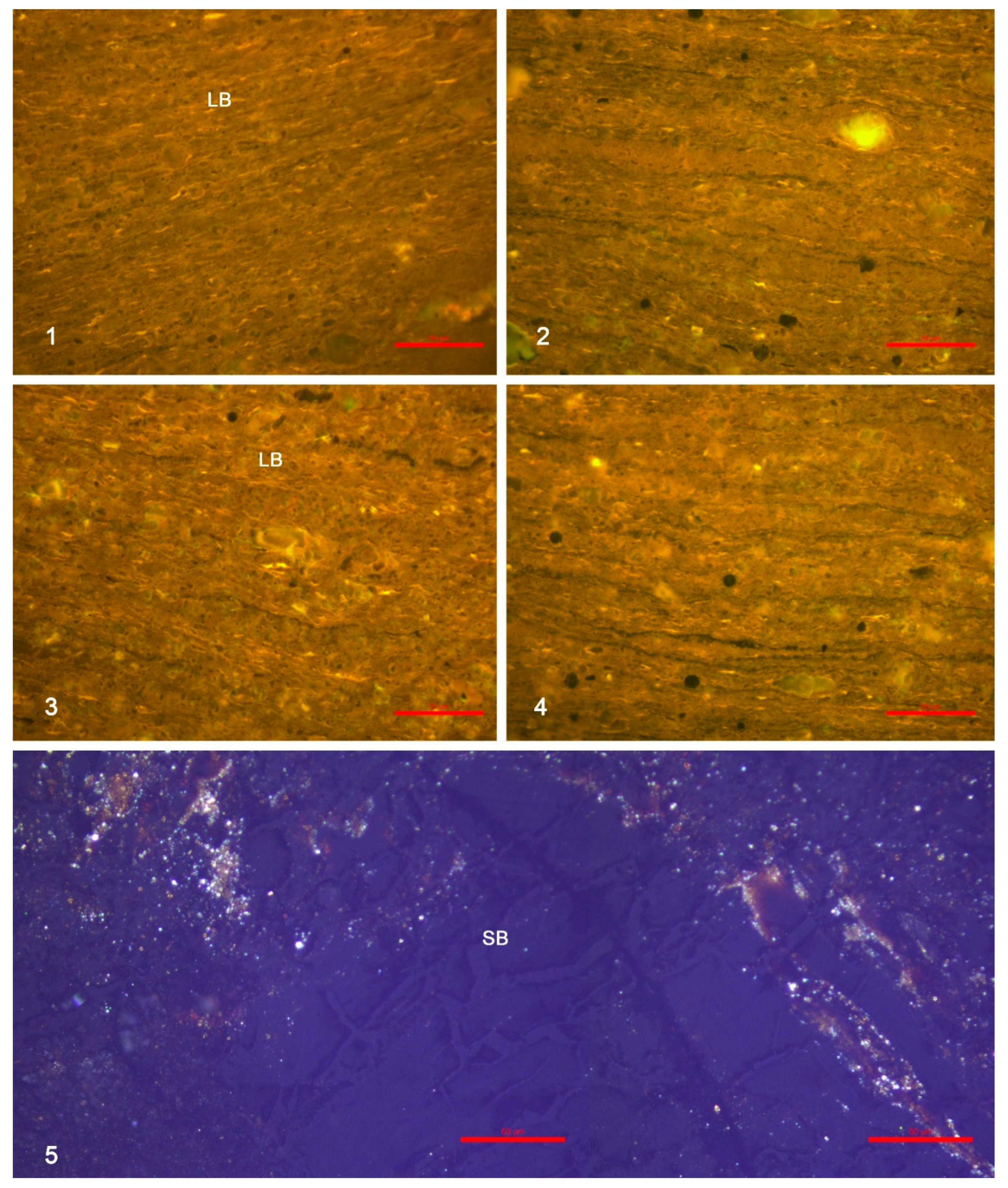

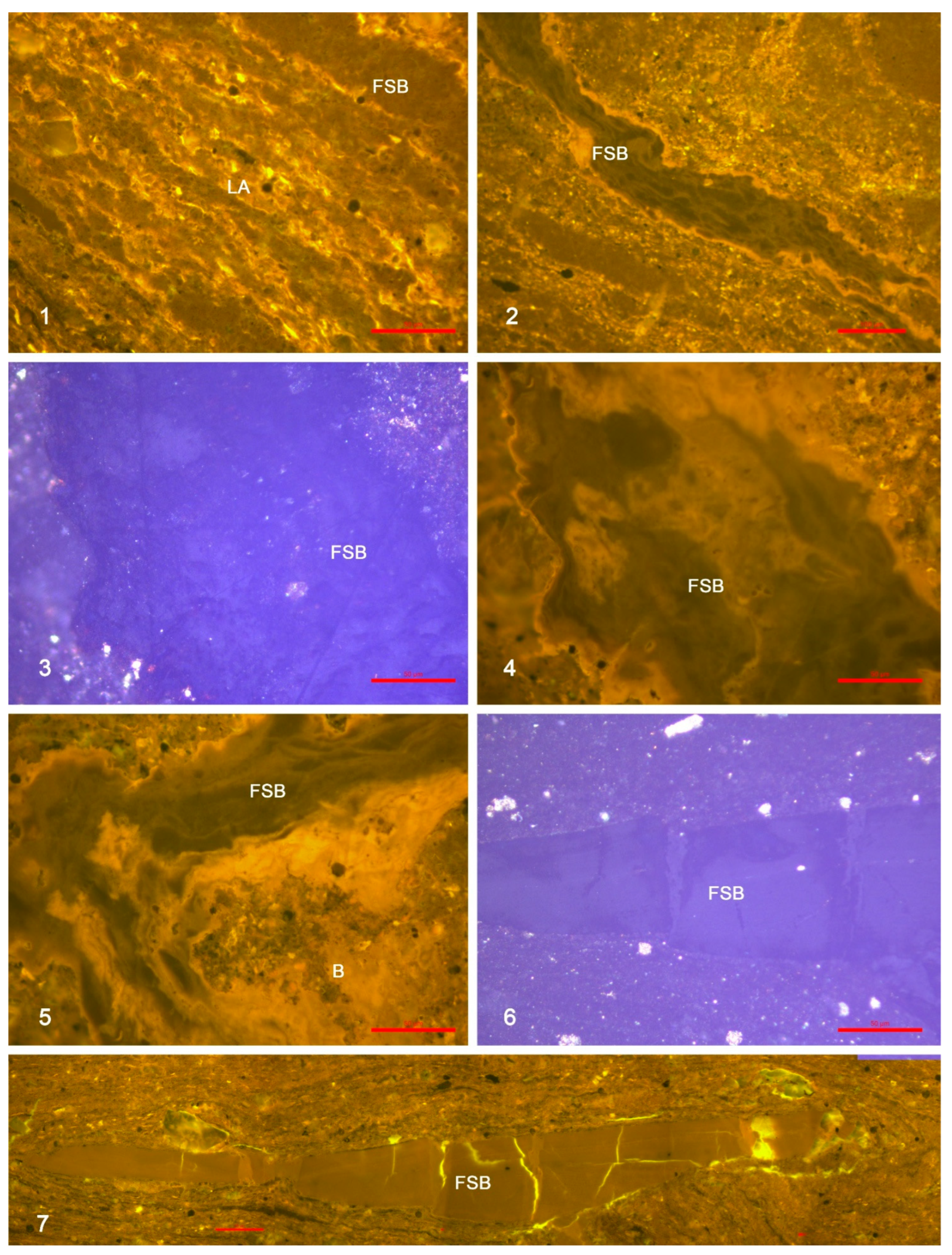

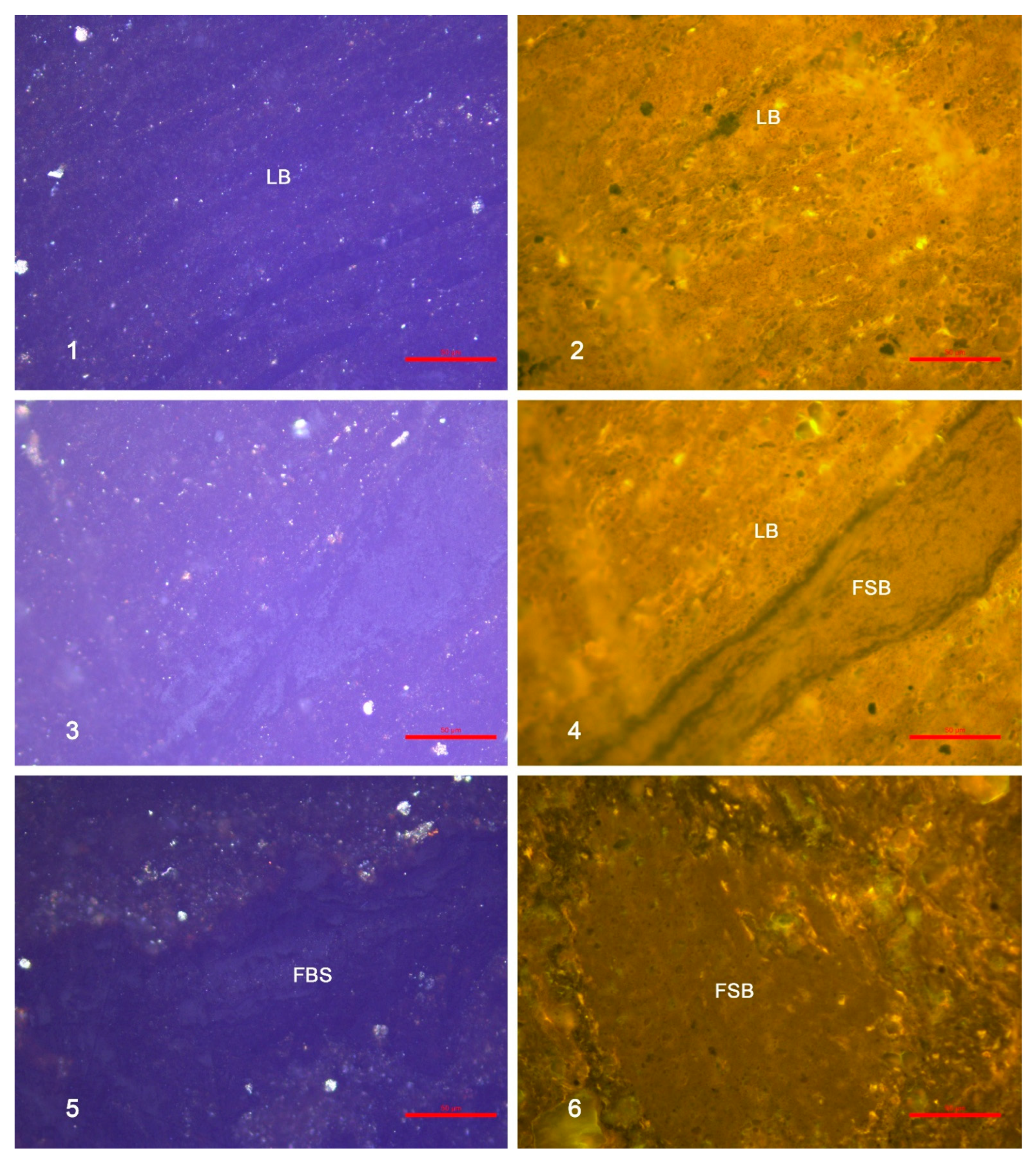

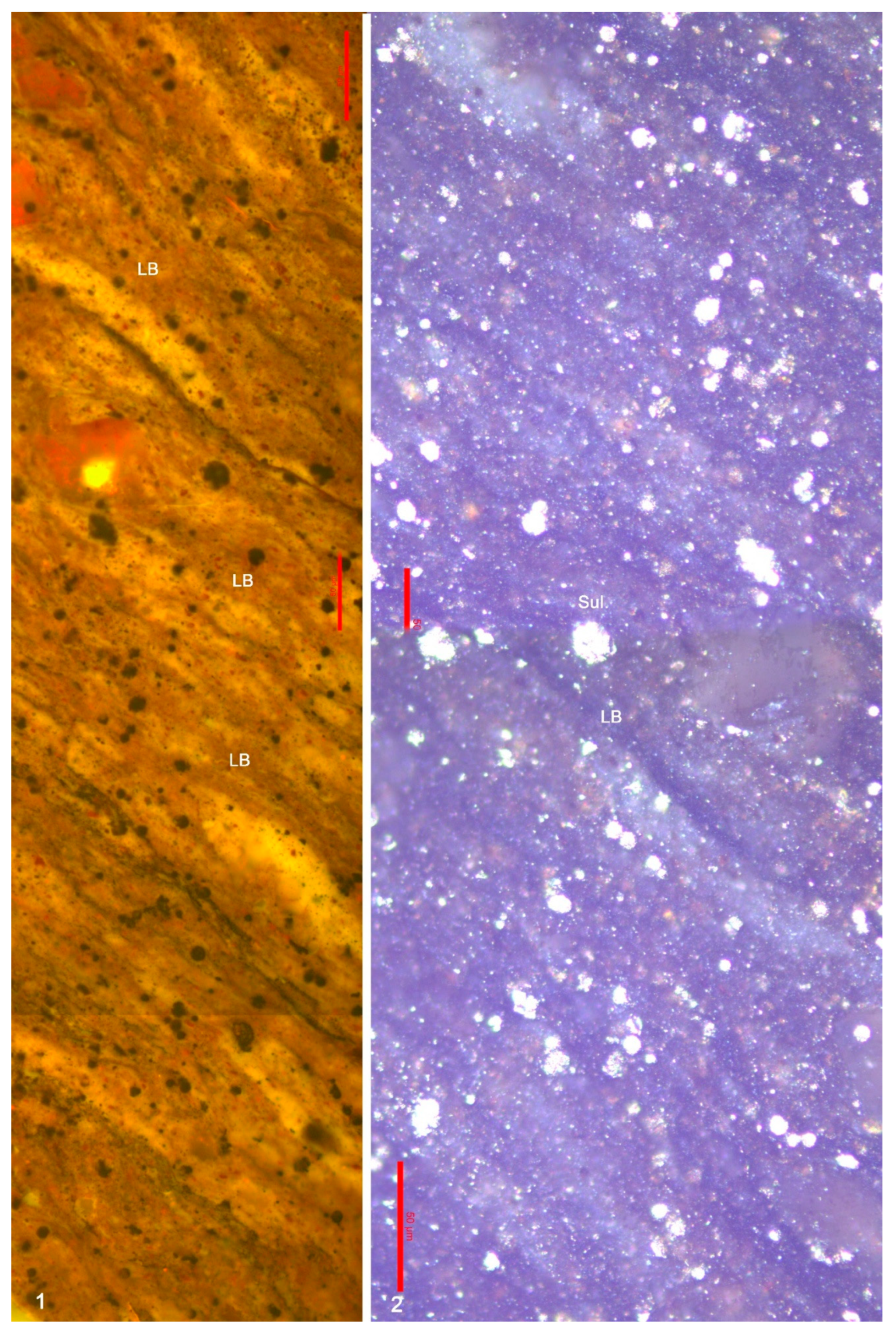

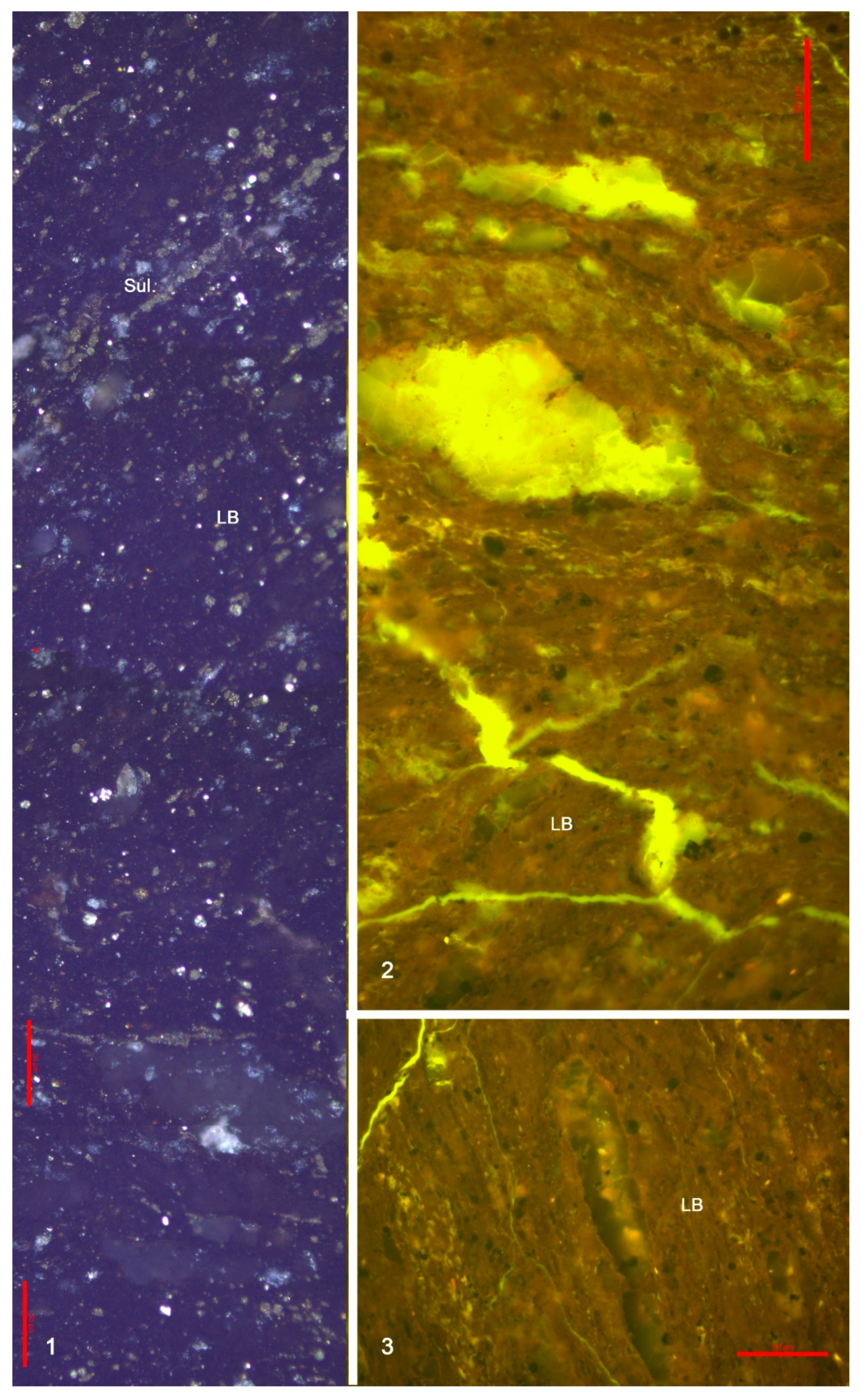

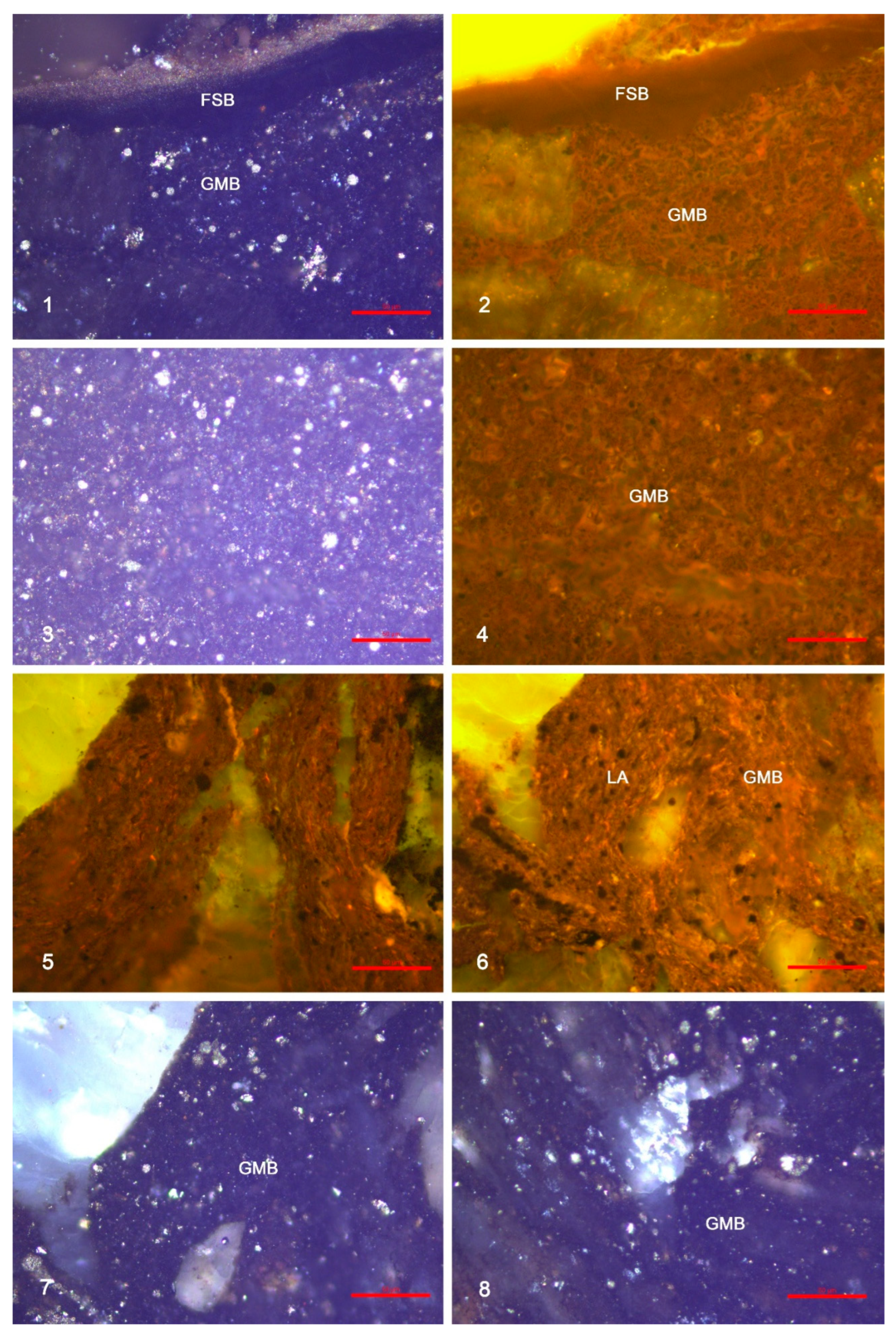

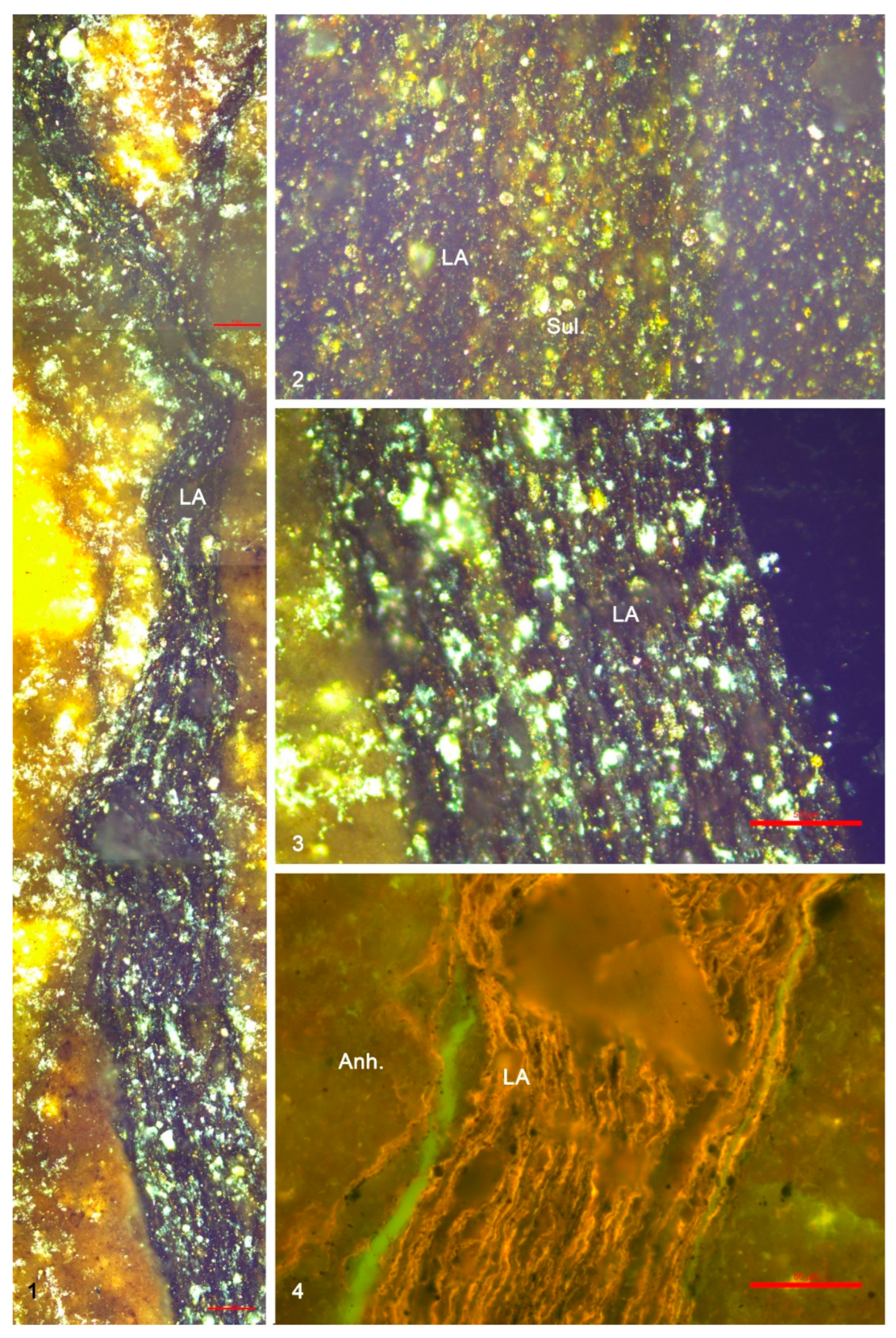

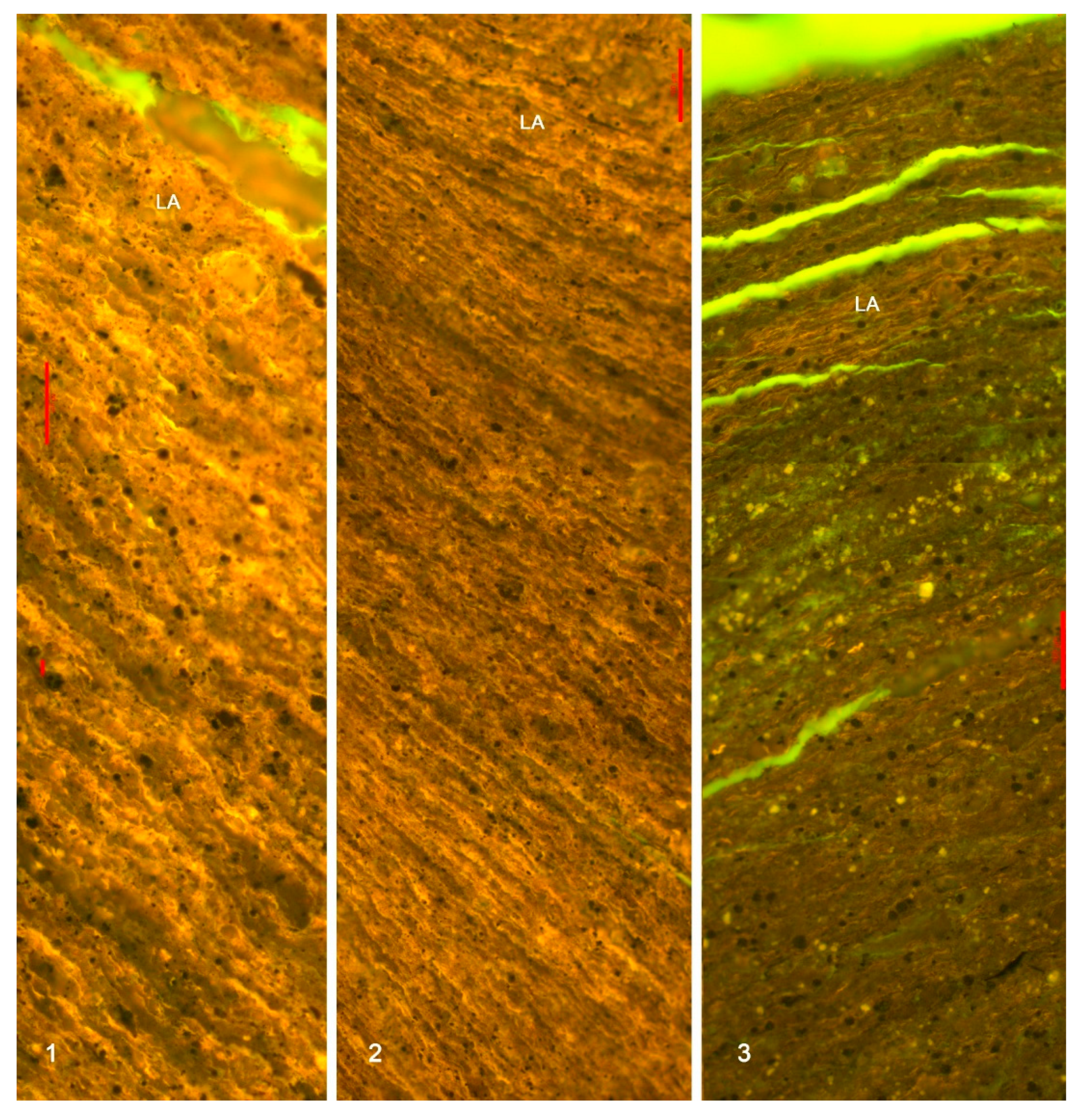

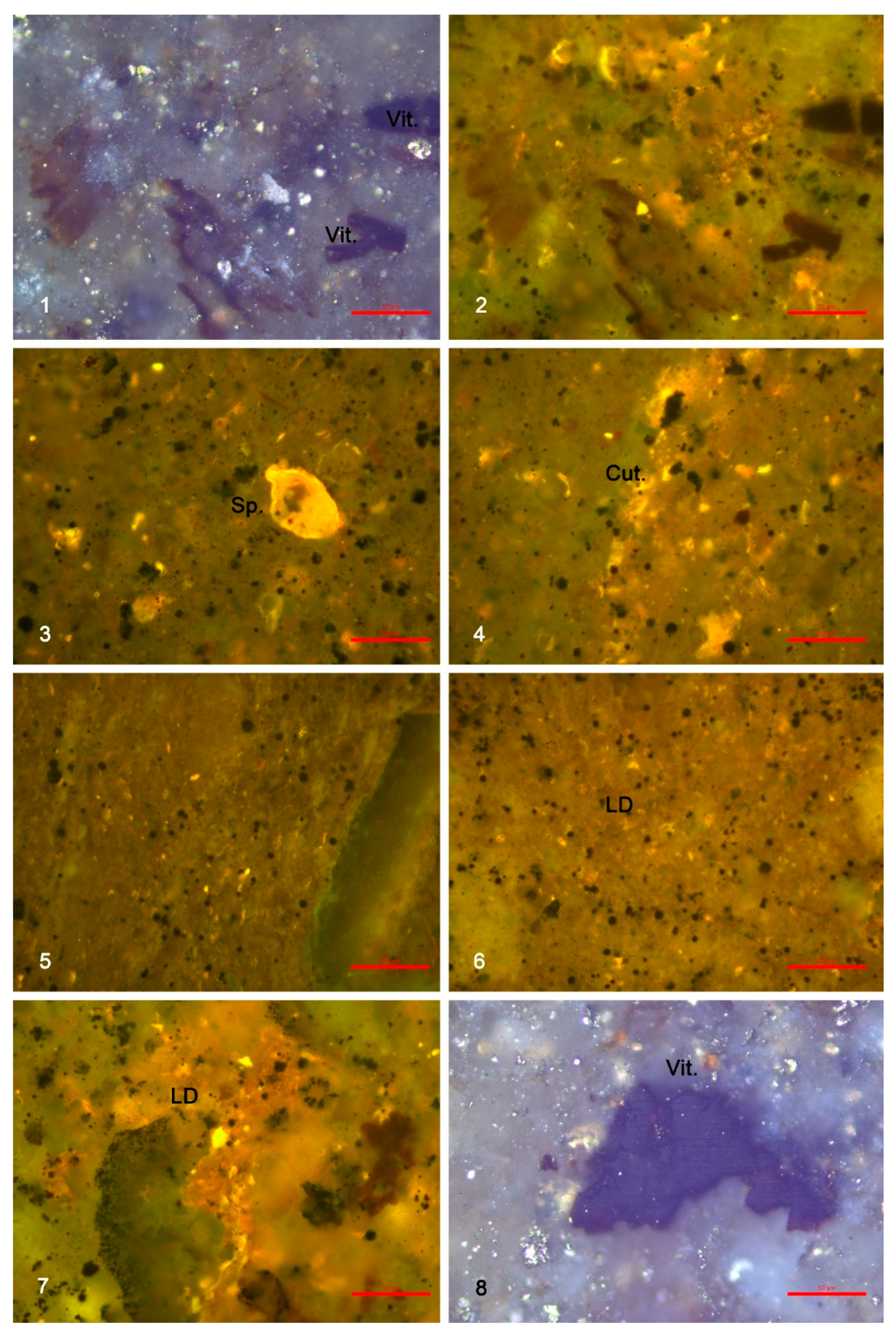

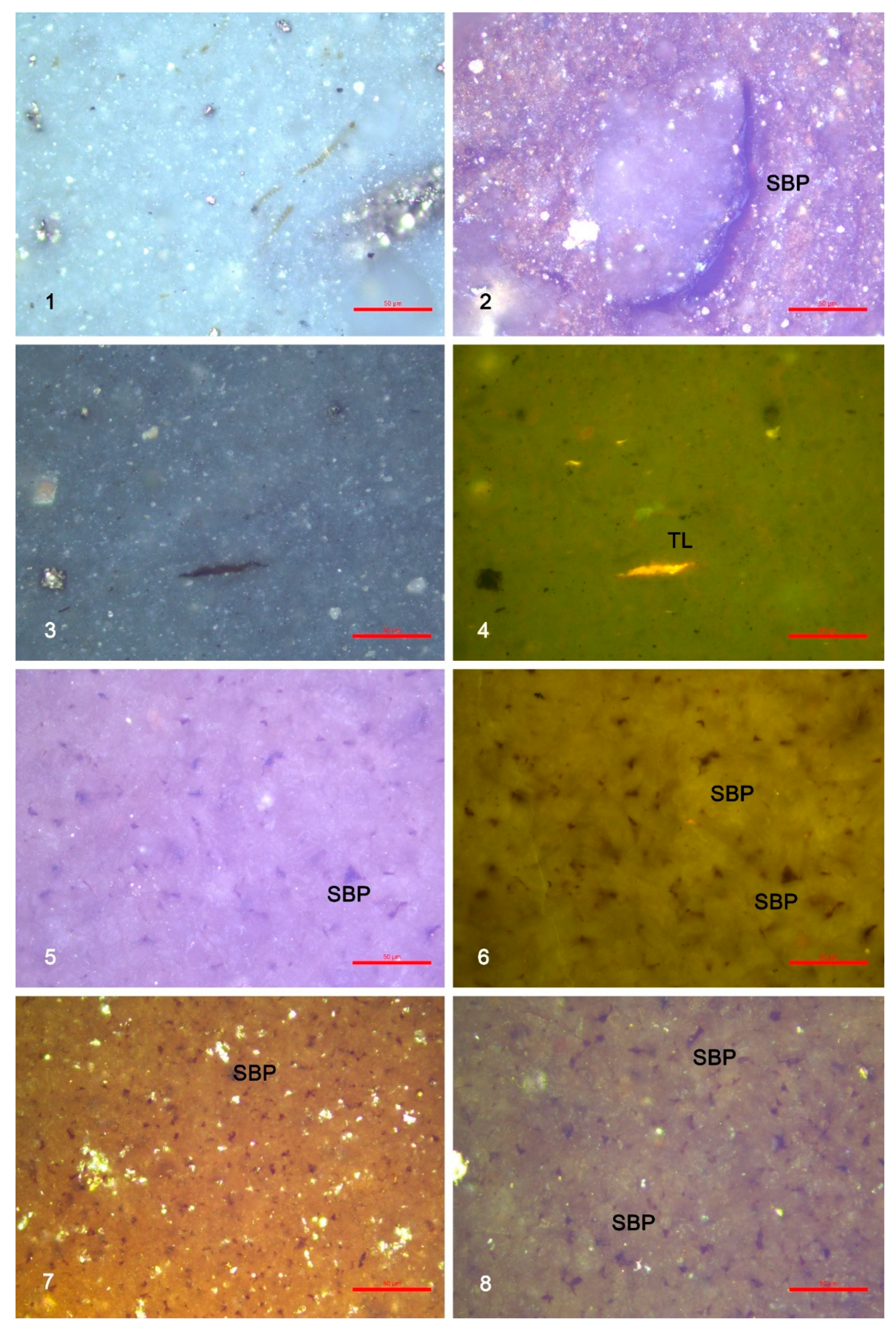

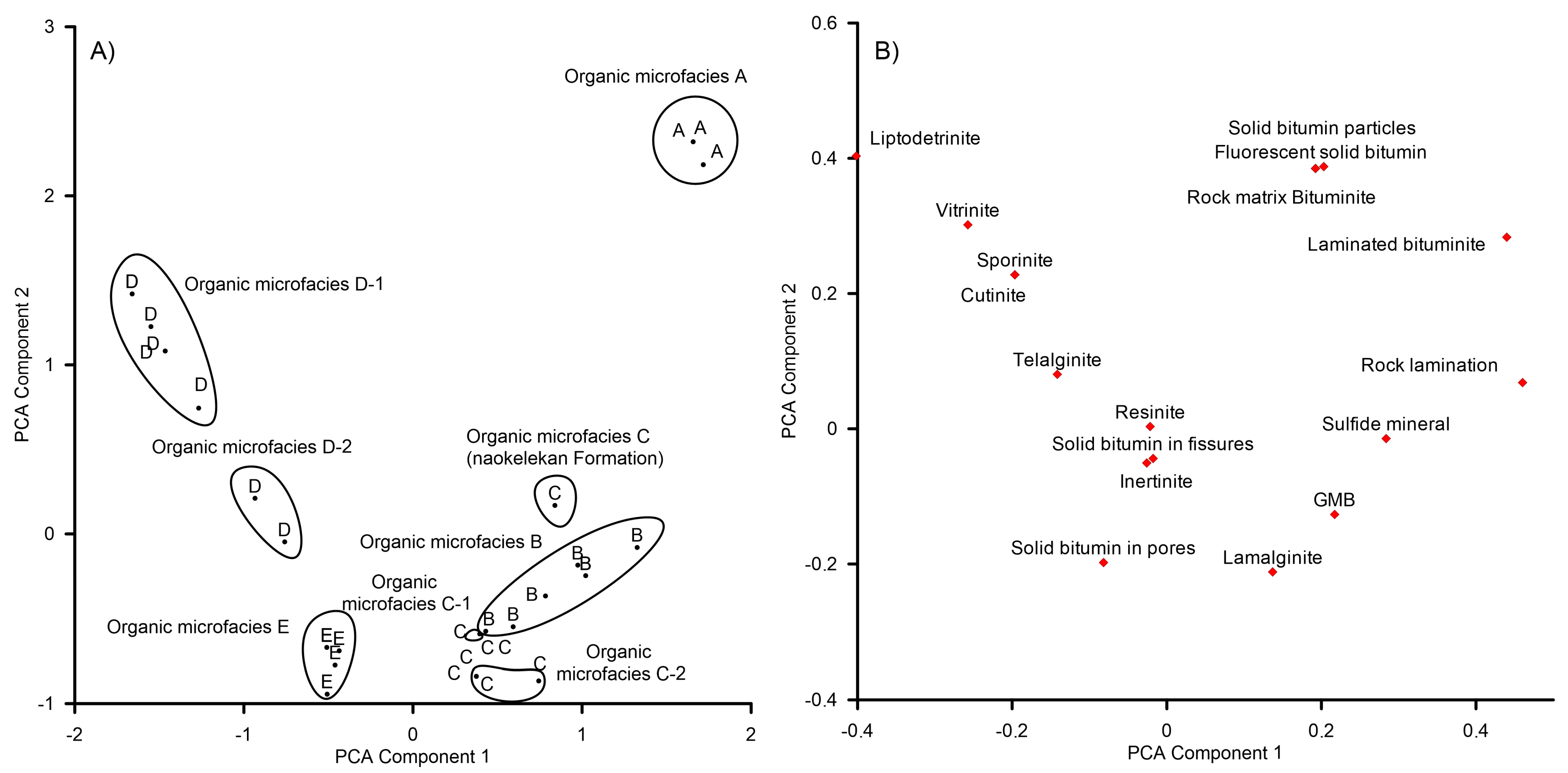

4.2.1. Organic Microfacies Classification

4.2.2. Distribution Model of Organic Microfacies

4.3. Organic Geochemical Analysis

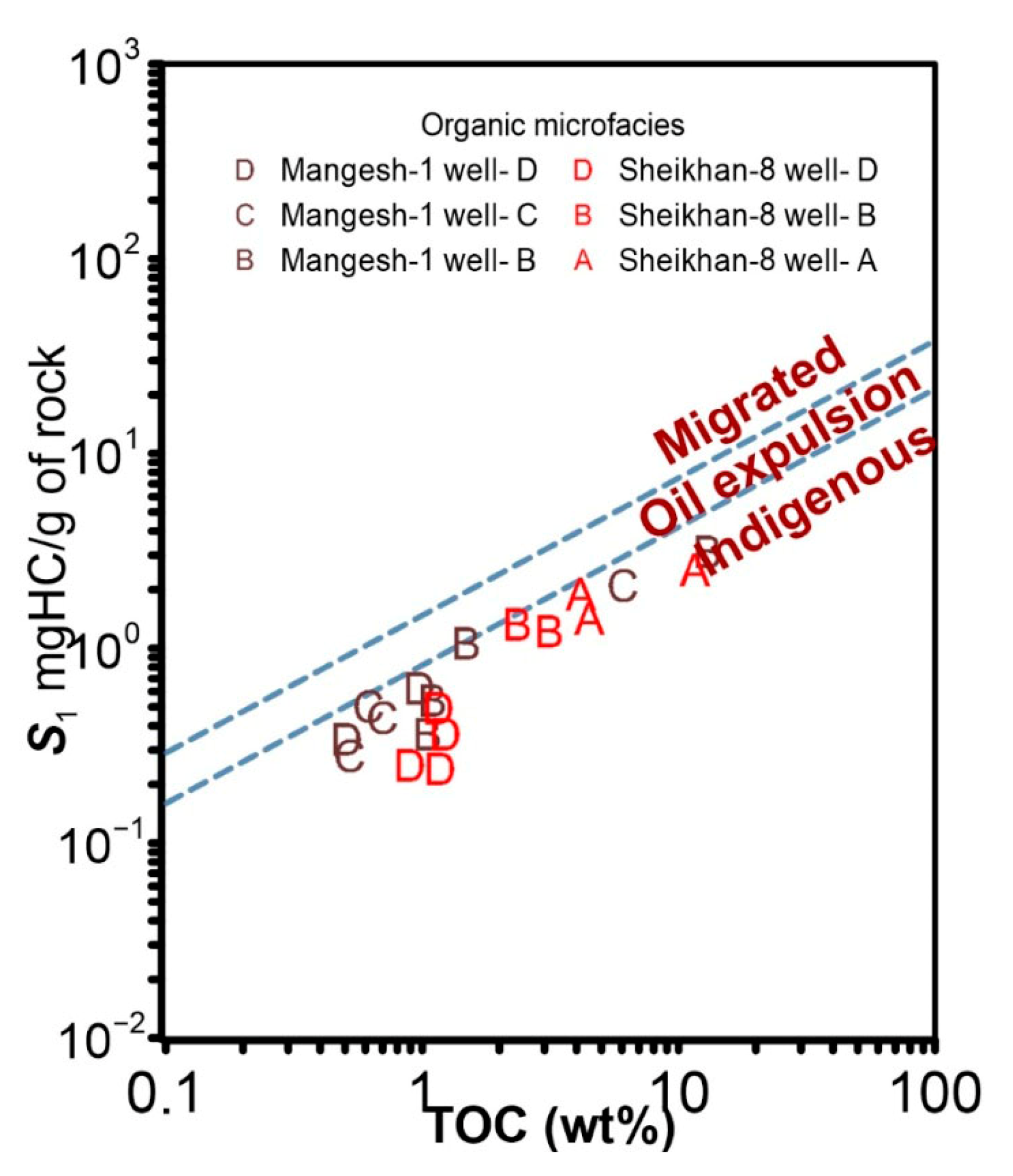

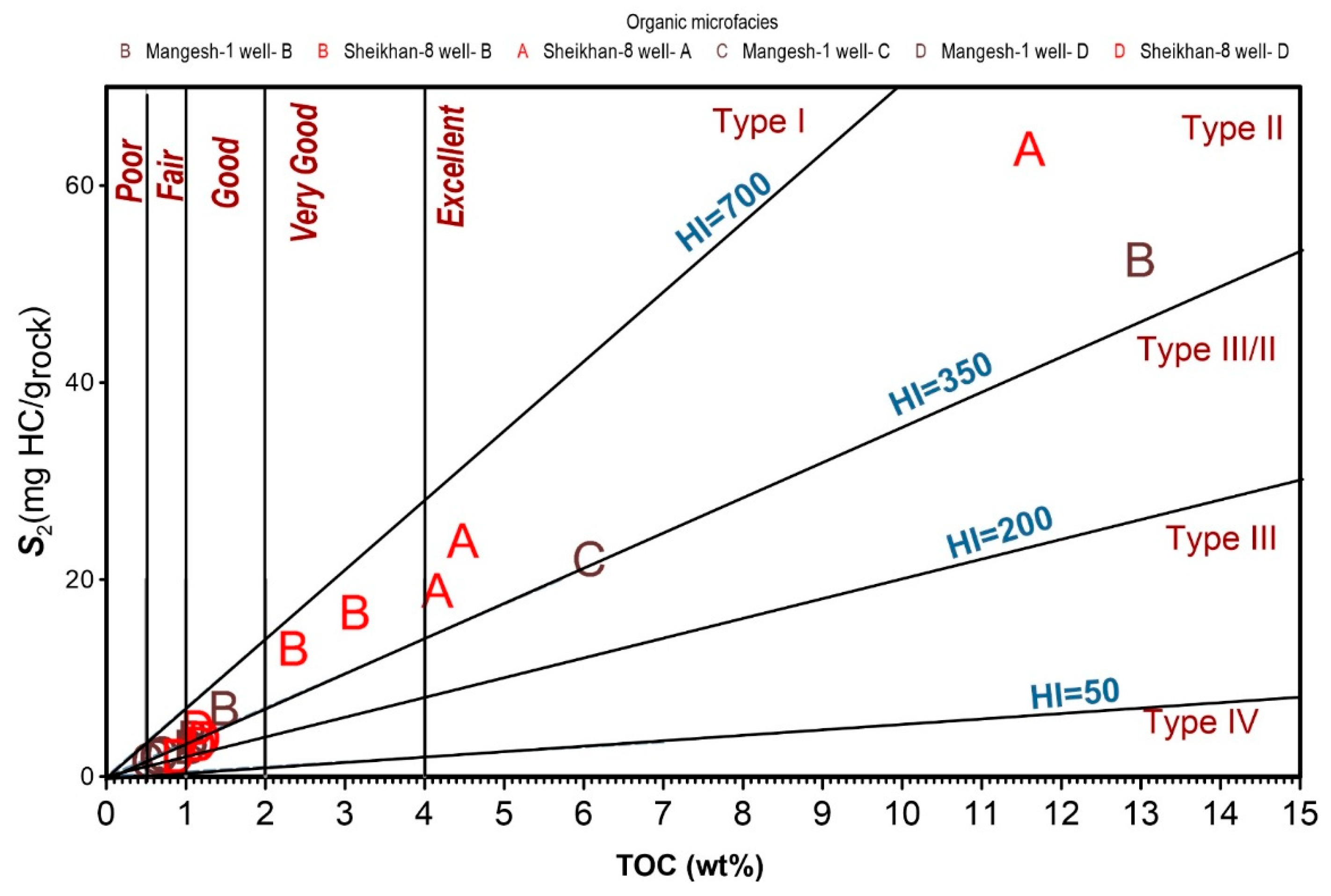

4.3.1. Organic Richness

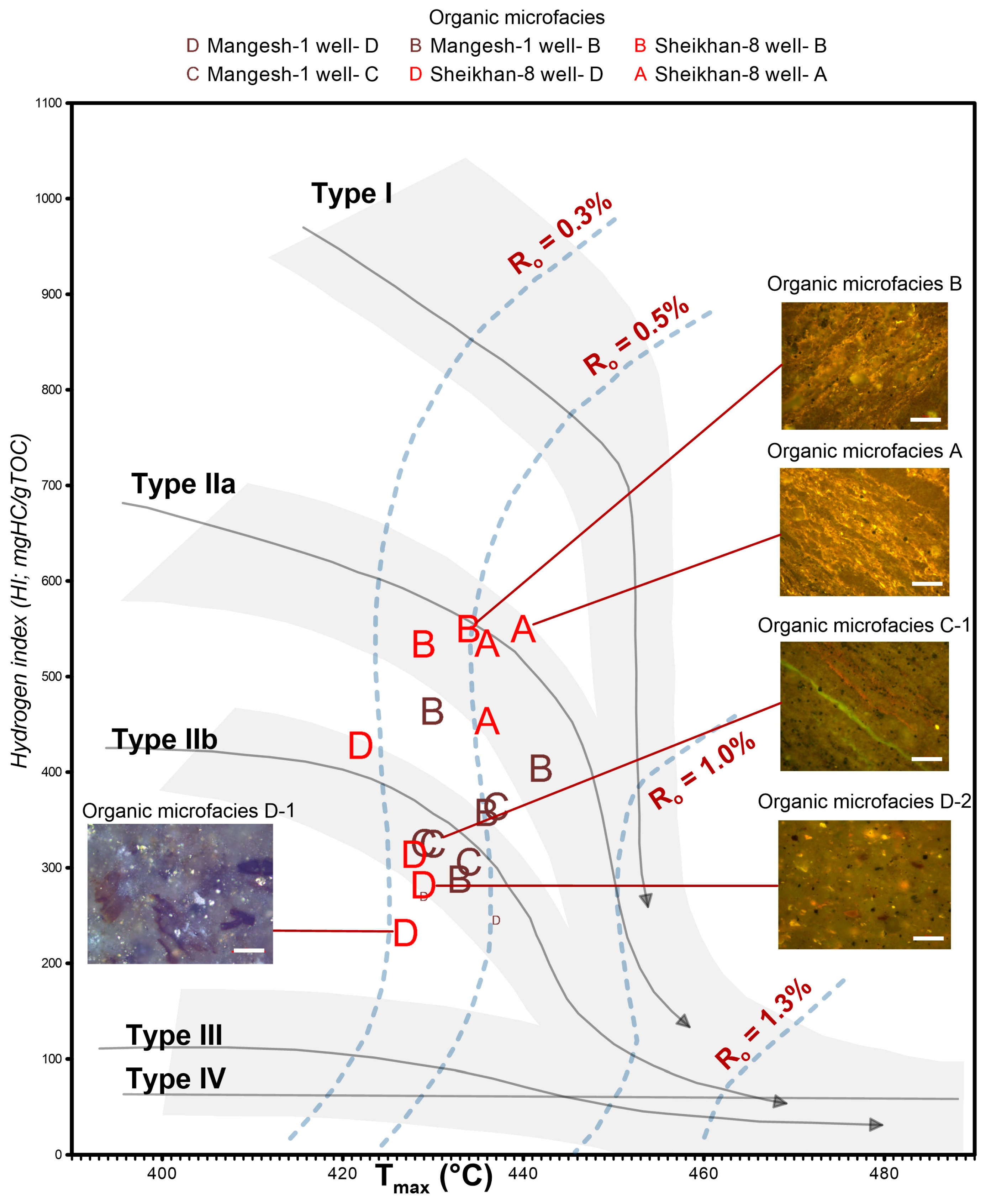

4.3.2. Organic Quality

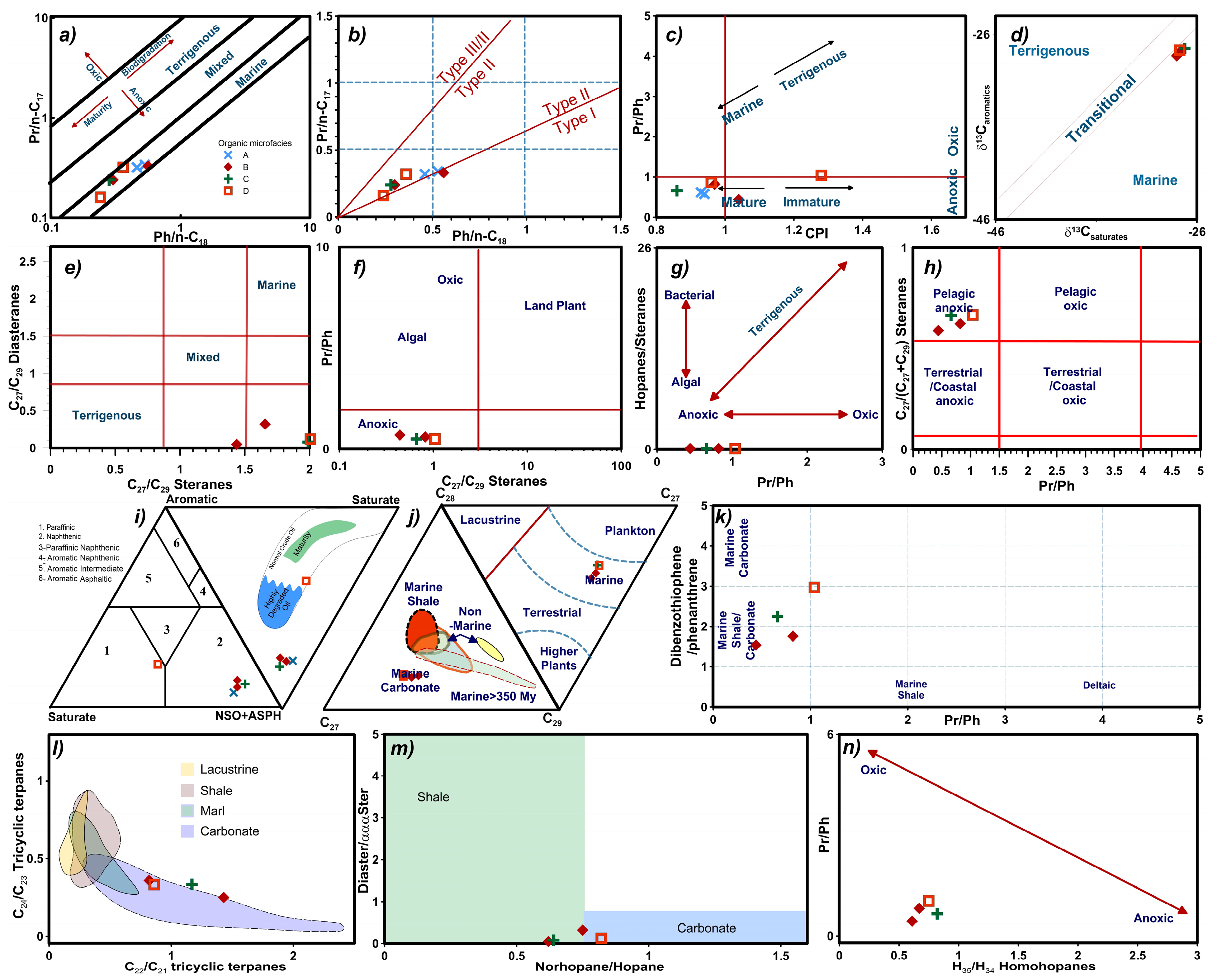

4.3.3. Molecular Organic Composition

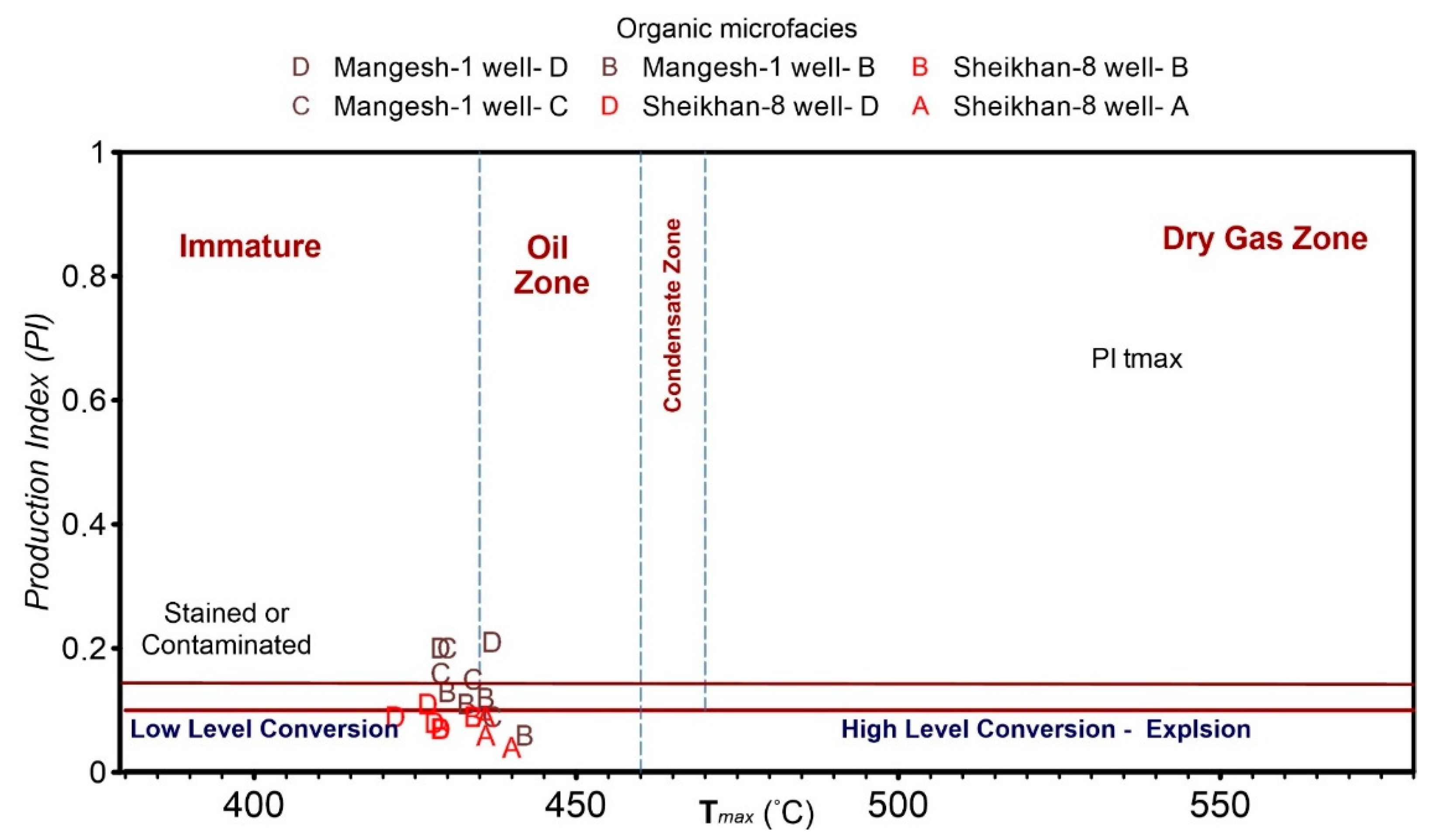

4.3.4. Thermal Maturity and Hydrocarbon Generation Indicators

5. Discussion

5.1. Paleoenvironmental Analysis of Organic Microfacies

5.2. Evolution and Modeling Organic Microfacies: An Approach to Source Rock Evaluation

5.2.1. Evolution and Change in Organic Microfacies

5.2.2. Dynamic Modeling of Organic Microfacies

5.3. The Role of Organic Microfacies in the Petroleum System

6. Conclusions

- Five distinct organic microfacies (A, B, C, D, E) were identified, each characterized by a unique assemblage of macerals, organic matter textures, and lamination patterns. These microfacies serve as sensitive indicators of varying depositional environments and organic matter preservation conditions.

- The organic geochemical parameters, including the TOC, Rock-Eval pyrolysis, molecular composition, and isotope, agree with the organic microfacies, indicating Type II kerogen and Type III kerogen.

- The Jurassic succession records a clear and progressive basin evolution, reflected in the shifting organic microfacies:

- ○

- The Sargelu Formation (Bajocian–Bathonian) was deposited in a deeper, open marine, anoxic setting, primarily characterized by organic microfacies C and D. This environment supported high marine productivity, although organic matter concentration was variably influenced by carbonate sedimentation rates.

- ○

- The Naokelekan Formation (Callovian–Oxfordian) marks a transition to a highly restricted silled intrashelf basin. Intense anoxia and significant sediment starvation during this period led to the formation of condensed sections. These sections are notably dominated by highly laminated bituminite (organic microfacies A), which signifies exceptionally high source rock potential.

- ○

- The Barsarin Formation (Kimmeridgian–Tithonian) represents the final stage of increased restriction, leading to hypersaline, evaporitic conditions. Its diverse organic microfacies (B, C, D, E) indicate a complex interplay of persistent marine productivity, episodic terrigenous input during short humid climatic events, and varying degrees of bottom water anoxia.

- Principal component analysis (PCA) proved to be an effective quantitative modeling tool, successfully defining the key paleoenvironmental gradients (e.g., redox conditions, primary productivity, terrigenous vs. marine influence, sedimentation rates) that control organic microfacies distribution. The PCA-derived microfacies classification (A–E) directly aligns with and provides quantitative support for the conceptual basin evolution model, significantly enhancing the understanding of the basin’s dynamic changes over time.

- Comprehensive organic geochemical parameters combined with widespread petrographic evidence of solid bitumen consistently indicate that all studied Jurassic intervals are within the oil window, with specific zones reaching peak generation, confirming effective hydrocarbon generation within these formations.

- Organic microfacies A, B, C, and D consistently provide direct petrographic and geochemical evidence of their role as effective source rocks, reflecting significant in situ hydrocarbon generation and excellent preservation of marine organic matter within their distinct fabrics.

- Organic microfacies E offers clear petrographic evidence of hydrocarbon migration into micro-fissures and pores within carbonates and evaporites. This indicates connectivity with other potentially underlying or adjacent source intervals, highlighting the complex migration pathways within the petroleum system.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verma, M.K.; Ahlbrandt, T.S.; Al-gailani, M. Petroleum reserves and undiscovered resources in the total petroleum systems of Iraq: Reserve growth and production implications. GeoArabia 2004, 9, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, M. Selected features of giant fields, using maps and histograms. AAPG Mem. 2004, 10068, 340. [Google Scholar]

- Gharib, A.F.; Haseeb, M.T.; Ahmed, M.S. Geochemical investigation and hydrocarbon generation–potential of the Chia Gara (Tithonian–Berriasian) source rocks at Hamrin and Kirkuk fields, Northwestern Zagros Basin, Iraq. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1300, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabbas, M.A.; Hassan, R.A. Geochemical and palynological analyses of the Serikagni Formation, Sinjar, Iraq. Arab. J. Geosci. 2013, 6, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, A.J.; Al Najm, F.M.; Al Ibrahim, R.N.; Sadooni, F.N. Geochemical investigation of Yamama crude oils and their inferred source rocks in the Mesopotamian Basin, Southern Iraq. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2019, 37, 2025–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, A.J.; Hakimi, M.H.; Ibrahim, E.-K. Organic geochemistry of oil seeps from the Abu-Jir Fault Zone in the Al-Anbar Governorate, western Iraq: Implications for early-mature sulfur-rich source rock. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 184, 106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dolaimy, A.M.S. Source rock characteristic of Sargelu and Kurrachine Formations from the selected wells in Northern Iraq. Iraqi Geol. J. 2021, 54, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, A.F.; Ozkan, A.M. Reservoir evaluation of the tertiary succession in selected wells at Ajeel Oilfield, Northern Mesopotamian Basin, NE Iraq. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, H.S.; Karim, K.H. Types of stromatolites in the Barsarin Formation (late Jurassic), Barzinja area, NE Iraq. Iraqi Bull. Geol. Min. 2010, 6, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ameri, T.K.; Zumberge, J. Middle and Upper Jurassic hydrocarbon potential of the Zagross Fold Belt, North Iraq. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2012, 36, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Juboury, A.I.; McCann, T. Petrological and geochemical interpretation of Triassic-Jurassic boundary sections from north Iraq. Geol. J. 2013, 50, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, S.Y. The potential of hydrocarbons generation in the Chia Gara Formation at Amadia area, north of Iraq. Arab. J. Geosci. 2013, 6, 3313–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdula, R. Source rock assessment of Naokelekan Formation in Iraqi Kurdistan. J. Zankoi Sulaimani Part-A (Pure Appl. Sci.) 2017, 19, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaseni, W.J.J. Petroleum potentiality and petrophysical evaluation of the Middle-Jurassic Sargelu Formation, Northern Iraq. Iraqi Geol. J. 2020, 53, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, J.K.; Steinshouer, D.; Lewan, M. Petroleum generation and migration in the Mesopotamian Basin and Zagros Fold Belt of Iraq: Results from a basin-modeling study. GeoArabia 2004, 9, 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadooni, F. Stratigraphy and petroleum prospects of Upper Jurassic carbonates in Iraq. Pet. Geosci. 1997, 3, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bellen, R.C.; Dunnington, H.V.; Wetzel, R.; Morton, D.M. Lexique Stratigraphique International: Vol. 3. Asie, Fascicule 10a Iraq; Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: Paris, France, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Aqrawi, A.A.M.; Badics, B. Geochemical characterisation, volumetric assessment and shale-oil/gas potential of the Middle Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous source rocks of NE Arabian Plate. GeoArabia 2015, 20, 99–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohialdeen, I.M.J.; Hakimi, M.H.; Al-Beyati, F.M. Geochemical and petrographic characterisation of late Jurassic-early Cretaceous Chia Gara Formation in northern Iraq: Palaeoenvironment and oil generation potential. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2013, 43, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqrawi, A.A.M.; Goff, J.C.; Horbury, A.D.; Sadooni, F.N. The Petroleum Geology of Iraq; Scientific Press: Buckinghamshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tobia, F.H.; Al-Jaleel, H.S.; Ahmad, I.N. Provenance and depositional environment of the Middle-Late Jurassic shales, northern Iraq. Geosci. J. 2019, 23, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.A. Application of organic facies concepts to hydrocarbon source-rock-evaluation. In Proc. Tenth World Pet. Congr. 1980, 10, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson, R.V. Sedimentary Organic Matter: Organic Facies and Palynofacies; Chapman and Hall: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995; p. 615. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, K.E.; Cassa, M.R. Applied source rock geochemistry. In The Petroleum System—From Source to Trap; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1994; pp. 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.W. Organic facies. In Advances in Petroleum Geochemistry; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Atroshi, J.S.; Sherwani, H.G.; Al-Naqshbandi, F.S. Assessment of the hydrocarbon potentiality of the Late Jurassic formations of NW Iraq: A case study based on TOC and Rock-Eval pyrolysis in selected oil-wells. Open Geosci. 2019, 11, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damoulianou, M.E.; Kolo, K.Y.; Borrego, A.G.; Kalaitzidis, S.P. Organic petrological and geochemical appraisal of the Upper Jurassic Naokelekan Formation, Kurdistan, Iraq. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2020, 232, 103637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, S.Z.; Goff, J.C. Geology of Iraq; Moravian Museum: Brno, Czech Republic, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, M.S. Effect of basement tectonics on hydrocarbon generation, migration, and accumulation in Northern Iraq. AAPG Bull. 1992, 76, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, J.; Jassim, S.Z.; Perincek, D. Mid-Triassic-Neogene tectonostratigraphic evolution of the northeastern active margin of the Arabian plate and its control on the evolution of the Gotnia basin. GeoArabia 2004, 9, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, R.H.; Ali, S.A.; Al-Juboury, A.I.; Rowe, H.; Zanoni, G. Mineralogical implications of the middle to upper Jurassic succession at Sargelu village in Sulaymaniyah city northeastern Iraq. Iraqi Natl. J. Earth Sci. 2024, 24, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdula, R.A.; Balaky, S.M.; Nourmohamadi, M.S.; Piroui, M. Microfacies analysis and depositional environment of the Sargelu Formation (Middle Jurassic) from Kurdistan Region, Northern Iraq. Donnish J. Geol. Min. Res. 2015, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sharland, P.R.; Archer, R.; Casey, D.M.; Hall, S.H.; Heward, A.P.; Horbury, A.D.; Simmons, M.D. Arabian Plate Sequence Stratigraphy; Gulf Petrolink: Manama, Bahrain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Buday, T. The Regional Geology of Iraq: Vol. 1. Stratigraphy and Paleogeography; State Organization for Minerals Library: Baghdad, Iraq, 1980.

- Murris, R.J. Middle East—Stratigraphic evolution and oil habitat. AAPG Bull. 1980, 64, 597–618. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Al-Gibouri, A.S. Geochemical and palynological analysis in assessing hydrocarbon potential and palaeoenvironmental deposition, North Iraq. J. Pet. Res. Stud. 2011, 190, 98–116. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Badri, A.M.S. Stratigraphy and Geochemistry of Jurassic Formations in Selected Sections-North Iraq. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Balaky, S.M.H. Sequence stratigraphic analyses of Naokelekan Formation (Late Jurassic), Barsarin area, Kurdistan Region—Northeast Iraq. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 5869–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, R.H.; Ali, S.A.; Al-Juboury, A.I.; Alarifi, N.; Lawa, F.A.; Rowe, H.; Zanoni, G.; Dettman, D.L. Mineralogy and geochemistry of the middle to upper Jurassic Sargelu, Naokelekan, and Barsarin formations from northeastern Iraq: Implications for paleoenvironmental, provenance, and tectonic setting proxies. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2025, 224, 105559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salae, A.T.S. Stratigraphy and Sedimentology of the Upper Jurassic Succession Northern Iraq. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, S.A.; Al-Jumaily, H.A.A.; Al-Juboury, A.I.; Rowe, H.; Zanoni, G.; Zumberge, A. Inorganic and organic geochemical characteristics of the Naokelekan Formation in northeastern Iraq: Implications for paleoredox conditions and organic maturity. Iraqi Geol. J. 2025, 58, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D2797; Standard Practice for Preparing Coal Samples for Microscopical Analysis by Reflected Light. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- D2799-23; Standard Test Method for Microscopical Determination of the Maceral Composition of Coal. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- D7708-23a; Standard Test Method for Microscopical Determination of the Reflectance of Vitrinite Dispersed in Sedimentary Rocks. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ICCP. The new vitrinite classification (ICCP System 1994). Fuel 1998, 77, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICCP. The new inertinite classification (ICCP System 1994). Fuel 2001, 80, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickel, W.; Kus, J.; Flores, D.; Kalaitzidis, S.; Christanis, K.; Cardott, B.J.; Misz-Kennan, M.; Rodrigues, S.; Hentschel, A.; Hamor-Vido, M.; et al. Classification of liptinite—ICCP system 1994. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2017, 169, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.H.; Teichmüller, M.; Davis, A.; Diessel, C.F.K.; Littke, R.; Roberts, P. Organic Petrology: A New Handbook Incorporating Some Revised Parts of Stach’s Textbook of Coal Petrology; Gebrüder Bornträger: Stuttgart, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.H., Jr. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Iperen, J.; Helder, W. A method for the determination of organic carbon in calcareous marine sediments. Mar. Geol. 1985, 64, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitalié, J.; Laporte, J.L.; Madec, M.; Marquis, F.; Leplat, P.; Paulet, J.; Boutefeu, A. Méthode rapide de caractérisation des roches-mères, de leur potentiel pétrolier et de leur degré d’évolution. Rev. L’institut Français Pétrole 1977, 32, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvie, D.M.; Claxton, B.L.; Henk, F.; Breyer, J.T. Oil and Shale Gas from the Barnett Shale, Fort Worth Basin, Texas. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 2001, 85, A100. [Google Scholar]

- Tissot, B.P.; Welte, D.H. Sedimentary processes and the accumulation of organic matter. In Petroleum Formation and Occurrence: A New Approach to Oil and Gas Exploration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1978; pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux, D.; Martin, H.; Leplat, P.; Paulet, J. Geochemical characterization of sedimentary organic matter by means of pyrolysis kinetic parameters. In Advances in Organic Geochemistry; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1990; Volume 16, pp. 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, F.F.; Blanc-Valleron, M.-M. Interpreting Rock-Eval pyrolysis data using graphs of pyrolizable hydrocarbons vs. total organic carbon. AAPG Bull. 1990, 74, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Krevelen, D.W. Coal: Typology-Chemistry-Physics-Constitution; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1961; 514p. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, K.E.; Walters, C.C.; Moldowan, J.M. The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and Isotopes in Petroleum Exploration and Earth History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leinfelder, R.R.; Schlagintweit, F.; Werner, W.; Ebli, O.; Nose, M.; Schmid, D.U.; Hughes, G.W. Significance of stromatoporoids in Jurassic reefs and carbonate platforms—Concepts and implications. Facies 2005, 51, 288–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, S.; Sendino, C. Labechia carbonaria Smith 1932 in the Early Carboniferous of England; affinity, palaeogeographic position and implications for the geological history of stromatoporoid-type sponges. J. Palaeogeogr. 2020, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackley, P.C.; Valentine, B.J.; Hatcherian, J.J. On the petrographic distinction of bituminite from solid bitumen in immature to early mature source rocks. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 196, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Bouroullec, J.; Dessort, D.; Albrecht, P. The microbial input in carbonate-anhydrite facies of sabkha palaeoenvironment from Guatemala: A molecular approach. Org. Geochem. 1986, 10, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, G. Significance of coniferous rain frost and related organic matter in generating commercial quantities of oil, Gippsland basin, Australia. AAPG Bull. 1985, 69, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Waples, D.W. Geochemistry in Petroleum Exploration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sofer, Z. Preparation of carbon dioxide for stable carbon isotope analysis of petroleum fractions. Anal. Chem. 1980, 52, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Diasty, W.S.; Moldowan, J.M. Application of biological markers in the recognition of the geochemical characteristics of some crude oils from Abu Gharadig Basin, north Western Desert–Egypt. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2012, 35, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, R.; Arouri, K.R.; Ward, C.R.; McKirdy, D.M. Oil generation by igneous intrusions in the northern Gunnedah Basin, Australia. Org. Geochem. 2001, 32, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-Y.; Meinschein, W.G. Sterols as ecological indicators. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1979, 43, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.W. Middle to Upper Jurassic Saudi Arabian carbonate petroleum reservoirs: Biostratigraphy, micropalaeontology, and palaeoenvironments. GeoArabia 2004, 9, 79–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembicki, H., Jr. Three common source rock evaluation errors made by geologists during prospect or play appraisals. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 2009, 93, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T. Petroleum system logic as an exploration tool in frontier setting. In The Petroleum System—From Source to Trap; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1994; pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Sonnenberg, S.A. Source rock potential of the Bakken Shales in the Williston Basin, North Dakota and Montana. In Proceedings of the Poster Presentation American Association of Petroleum Geologists Annual Convention and Exhibition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 22–25 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi, F.; Gentzis, T.; Karacan, C.Ö.; Sanei, H.; Pedersen, P.K. Petrology and geochemistry of migrated hydrocarbons associated with the Albert Formation oil shale in New Brunswick, Canada. Fuel 2019, 256, 115922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, F.; Haeri-Ardakani, O.; Gentzis, T.; Pedersen, P.K. Organic petrology and geochemistry of Tournaisian-age Albert Formation oil shales, New Brunswick, Canada. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 205, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makled, W.A.; Mostafa, T.F.; Maky, A.B.F. Mechanism of Late Campanian–Early Maastrichtian oil shale deposition and its sequence stratigraphy implications inferred from the palynological and geochemical analysis. Egypt. J. Pet. 2014, 23, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.J. Controlling factors on the source rock development—A review of productivity, preservation and sedimentation rate. In The Deposition of Organic-Carbon-Rich Sediments: Models, Mechanisms, and Consequences; SEPM: Claremore, OK, USA, 2005; pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson, R.V. The “productivity versus preservation” controversy: Cause, flaws, and resolution. In The Deposition of Organic-Carbon-Rich Sediments: Models, Mechanisms, and Consequences; SEPM: Claremore, OK, USA, 2005; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Makled, W.A.; Ashwah, A.A.E.; Lotfy, M.M.; Hegazey, R.M. Anatomy of the organic carbon related to the Miocene syn-rift dysoxia of the Rudeis Formation based on foraminiferal indicators and palynofacies analysis in the Gulf of Suez, Egypt. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 111, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makled, W.A.; Gentzis, T.; Hosny, A.M.; Mousa, D.A.; Lotfy, M.M.; Abd El Ghany, A.A.; Shahat, W.I. Depositional dynamics of the Devonian rocks and their influence on the distribution patterns of liptinite in the Sifa-1X well, Western Desert, Egypt: Implications for hydrocarbon generation. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 126, 104935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou El-Anwar, E.; Salman, S.; Makled, W.; Mousa, D.; Gentzis, T.; Shazly, T.F. Depositional mechanism of Duwi Formation organic-rich rocks in anoxic Campanian-early Maastrichtian condensed sections in the Qusseir–Safaga region in Eastern Desert of Egypt and their economic importance. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 163, 106759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumsack, H.J. Responses of the sediment regime to present coastal upwelling. In Coastal Upwelling, Its Sediment Record; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; p. 471. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, D.J.; Bustin, R.M. Sediment geochemistry of the lower Jurassic Gordondale member, northeastern British Columbia. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol. 2006, 54, 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichmüller, M. Organic petrology of source rocks, history and state of the art. Org. Geochem. 1986, 10, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littke, R.; Sachsenhofer, R.F. Organic petrology of deep sea sediments: A compilation of results from the Ocean Drilling Program and the Deep Sea Drilling Project. Energy Fuels 1994, 8, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.R.; Ludlam, S.D. Origin of laminated and graded sediments, Middle Devonian of western Canada. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1973, 84, 3527–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearman, D.J.; Fuller, J.G.C.M. Anhydrite diagenesis, calcitization, and organic laminites, Winnipegosis Formation, Middle Devonian, Saskatchewan. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol. 1969, 17, 496–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhl, J.H.; Schmid-Röhl, A. Lower Toarcian (Upper Liassic) black shales of the Central European epicontinental basin: A sequence stratigraphic case study from the SW German Posidonia shale. In The Deposition of Organic Carbon-Rich Sediments: Models, Mechanisms, and Consequences; Society for Sedimentary Geology: Claremore, OK, USA, 2005; pp. 165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Słowakiewicz, M.; Panajew, P. Organic geochemistry and origin of bitumen seeps in the Upper Permian (Zechstein) bituminous anhydrite in a Cu–Ag mine in western Poland. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2022, 111, 1373–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damoulianou, M.E.; Perleros, K.; Mohialdeen, I.M.; Khanaqa, P.; Araujo, C.V.; Kalaitzidis, S. Characterization of the bituminite-rich Chia Gara Formation in M-2 well Miran field, Kurdistan Region, NE Iraq. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2022, 263, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohialdeen, I.M.; Mustafa, K.A.; Salih, D.A.; Sephton, M.A.; Saeed, D.A. Biomarker analysis of the upper Jurassic Naokelekan and Barsarin formations in the Miran Well-2, Miran oil field, Kurdistan region, Iraq. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.; McCann, T.; Al-Juboury, A.I.; Franz, S.O. Petrography and geochemistry of the Middle-Upper Jurassic Banik section, northernmost Iraq–Implications for palaeoredox, evaporitic and diagenetic conditions. Neues Jahrb. Geol. Paläontologie-Abh. 2020, 297, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, C.T.; Abdula, R.A. Palaeoenvironment conditions during deposition of Sargelu, Naokelekan, and Najmah formations in Zey Gawara Area, Kurdistan Region, Iraq: Implications from major and trace elements proportions. Iraqi Geol. J. 2023, 56, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.B. The Deposition of Organic-Carbon-Rich Sediments: Models, Mechanisms, and Consequences—Introduction; SEPM: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, N.; Wendte, J.; Stasiuk, L.D. Productivity versus preservation controls on two organic-rich carbonate facies in the Devonian of Alberta: Sedimentological and organic petrological evidence. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol. 1995, 43, 433–460. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, M.B.; Pratt, B. Stratigraphy of the Middle Devonian Keg River and Prairie Evaporite formations, northeast Alberta, Canada. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol. 2017, 65, 5–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiuk, L.D.; Fowler, M.G. Organic facies in Devonian and Mississippian strata of Western Canada Sedimentary Basin: Relation to kerogen type, paleoenvironment, and paleogeography. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol. 2004, 52, 234–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M.A. Late Permian to Holocene paleofacies evolution of the Arabian Plate and its hydrocarbon occurrences. GeoArabia 2001, 6, 445–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wignall, P.B. Model for transgressive black shales? Geology 1991, 19, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaafary, A.S.; Hadi, A. Hydrocarbon potential, thermal maturation of the Jurassic sequences, and the genetic implication for the oil seeps in North Thrust Zone, North Iraq. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 8089–8105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdula, R. Petroleum Source Rock Analysis of the Jurassic Sargelu Formation, Northern Iraq. Master’s Thesis, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kammar, M.M.; Hussein, F.S.; Sherwani, G.H. Organic petrological and geochemical evaluation of Jurassic source rocks from North Iraq. Asian Rev. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, N.; McCann, T.; Al-Juboury, A.I.; Franz, S.O.; Zanoni, G.; Rowe, H. A comparative study of the paleoclimate, paleosalinity and paleoredox conditions of Lower Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous sediments in northeastern Iraq. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 156, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ahmed, A.A.N. Determination and applications of chemical analysis to evaluate Jurassic hydrocarbon potentiality in Northern Iraq. Arab. J. Geosci. 2013, 6, 2941–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Diasty, W.S.; El Beialy, S.Y.; Peters, K.E.; Batten, D.J.; Al-Beyati, F.M.; Mahdi, A.Q.; Haseeb, M.T. Organic geochemistry of the Middle-Upper Jurassic Naokelekan Formation in the Ajil and Balad oil fields, northern Iraq. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 166, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.; McCann, T.; Al-Juboury, A.I.; Suárez-Ruiz, I. Solid bitumen in shales from the Middle to Upper Jurassic Sargelu and Naokelekan Formations of northernmost Iraq: Implication for reservoir characterization. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharhan, A.S.; Kendall, C.S.C. Holocene coastal carbonates and evaporites of the southern Arabian Gulf and their ancient analogues. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2003, 61, 191–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Well | Sample Depth | Vitrinite | Inertinite | GMB | Laminated Bituminite | Rock Matrix Bituminite | Cutinite | Sporinite | Telalginite | Lamalginite | Resinite | Liptodetrinite | Solid Bitumen in Pores | Solid Bitumen in Fissures | Solid Bitumen Particles | Fluorescent Solid Bitumen | Rock Lamination | Sulfide Mineral | Organic Microfacies | PCA1 | PCA2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangesh-1 | 2319 | Barsarin | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | B | 0.6 | −0.5 |

| 2337 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | B | 0.8 | −0.4 | ||

| 2380 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.5 | −0.7 | ||

| 2397 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | D | −1.7 | 1.4 | ||

| 2424 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | D | −1.5 | 1.2 | ||

| 2427 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.4 | −0.7 | ||

| 2442 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.5 | −0.7 | ||

| 2448 | Naokelekan | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | B | 1.3 | −0.1 | |

| 2451 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.5 | −0.8 | ||

| 2463 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | C | 0.8 | 0.2 | ||

| 2484 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | B | 1.0 | −0.2 | ||

| 2502 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | B | 1.0 | −0.2 | ||

| 2505 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.5 | −0.9 | ||

| 2544 | Sargelu | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | C | 0.4 | −0.6 | |

| 2610 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | D | −0.9 | 0.2 | ||

| 2616 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | D | −0.8 | 0.0 | ||

| 2631 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | C | 0.4 | −0.6 | ||

| 2643 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | C | 0.4 | −0.6 | ||

| Sheikhan−8 | 1495 | Barsarin | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | B | 0.4 | −0.6 |

| 1503 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.5 | −0.7 | ||

| 1509 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | B | 1.0 | −0.2 | ||

| 1515 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.4 | −0.7 | ||

| 1522 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | C | 0.7 | −0.9 | ||

| 1531 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | C | 0.4 | −0.8 | ||

| 1534 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | C | 0.4 | −0.8 | ||

| 1537 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | C | 0.4 | −0.8 | ||

| 1542 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | D | −1.5 | 1.1 | ||

| 1557 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | D | −1.5 | 1.1 | ||

| 1569 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | D | −1.3 | 0.7 | ||

| 1601 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.5 | −0.7 | ||

| 1611 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | D | −1.7 | 1.4 | ||

| 1629 | Naokelekan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | A | 1.7 | 2.2 | |

| 1641 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | E | −0.5 | −0.9 | ||

| 1659 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | A | 1.7 | 2.3 | ||

| 1664 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | A | 1.7 | 2.3 |

| Well | Depth | Rock Formation | Organic Microfacies | TOC | S1 | S2 | S3 | HI | S2/S3 | Tmax | Ro | PI | GP | S1/TOC | OI | PI | GP | Ro | S1/TOC | S2/S3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangesh-1 | 2319 | Barsarin | B | 1.49 | 1.06 | 6.92 | 0.61 | 464.00 | 11.34 | 430.00 | 0.58 | 0.13 | 7.98 | 627.11 | 41.00 | 0.13 | 7.98 | 0.58 | 71.14 | 11.34 |

| 2397 | D | 0.98 | 0.62 | 2.40 | 0.58 | 245.00 | 4.14 | 437.00 | 0.71 | 0.21 | 3.02 | 1528.91 | 59.00 | 0.21 | 3.02 | 0.71 | 63.27 | 4.14 | ||

| 2448 | Naokelekan | B | 13.00 | 3.14 | 52.48 | 0.80 | 404.00 | 65.60 | 442.00 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 55.62 | 36.82 | 6.00 | 0.06 | 55.62 | 0.80 | 24.15 | 65.60 | |

| 2463 | C | 6.07 | 2.11 | 22.09 | 0.90 | 364.00 | 24.54 | 437.00 | 0.71 | 0.09 | 24.20 | 141.63 | 15.00 | 0.09 | 24.20 | 0.71 | 34.76 | 24.54 | ||

| 2484 | B | 1.10 | 0.54 | 3.94 | 0.64 | 358.00 | 6.16 | 436.00 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 4.48 | 797.42 | 58.00 | 0.12 | 4.48 | 0.69 | 49.09 | 6.16 | ||

| 2502 | 1.05 | 0.36 | 3.02 | 0.93 | 288.00 | 3.25 | 433.00 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 3.38 | 1055.82 | 89.00 | 0.11 | 3.38 | 0.63 | 34.29 | 3.25 | |||

| 2544 | Sargelu | C | 0.52 | 0.28 | 1.59 | 0.54 | 306.00 | 2.94 | 434.00 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 1.87 | 1828.74 | 104.00 | 0.15 | 1.87 | 0.65 | 53.85 | 2.94 | |

| 2610 | D | 0.51 | 0.34 | 1.37 | 1.04 | 270.00 | 1.32 | 429.00 | 0.56 | 0.20 | 1.71 | 5060.83 | 205.00 | 0.20 | 1.71 | 0.56 | 66.67 | 1.32 | ||

| 2631 | C | 0.62 | 0.50 | 2.01 | 0.86 | 325.00 | 2.34 | 430.00 | 0.58 | 0.20 | 2.51 | 3450.49 | 139.00 | 0.20 | 2.51 | 0.58 | 80.65 | 2.34 | ||

| 2643 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 2.28 | 0.89 | 326.00 | 2.56 | 429.00 | 0.56 | 0.16 | 2.72 | 2453.63 | 127.00 | 0.16 | 2.72 | 0.56 | 62.86 | 2.56 | |||

| Sheikhan-8 | 1629 | Naokelekan | A | 4.16 | 1.89 | 18.88 | 0.72 | 454.00 | 26.22 | 436.00 | 0.69 | 0.09 | 20.77 | 173.26 | 17.00 | 0.09 | 20.77 | 0.69 | 45.43 | 26.22 |

| 1659 | 11.60 | 2.52 | 63.75 | 0.90 | 550.00 | 70.83 | 440.00 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 66.27 | 30.67 | 8.00 | 0.04 | 66.27 | 0.76 | 21.72 | 70.83 | |||

| 1664 | 4.48 | 1.43 | 23.95 | 0.72 | 535.00 | 33.26 | 436.00 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 25.38 | 95.96 | 16.00 | 0.06 | 25.38 | 0.69 | 31.92 | 33.26 | |||

| 1495 | Barsarin | B | 3.13 | 1.22 | 16.70 | 1.03 | 534.00 | 16.21 | 429.00 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 17.92 | 240.40 | 33.00 | 0.07 | 17.92 | 0.56 | 38.98 | 16.21 | |

| 1509 | 2.36 | 1.33 | 12.99 | 0.70 | 550.00 | 18.56 | 434.00 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 14.32 | 303.69 | 30.00 | 0.09 | 14.32 | 0.65 | 56.36 | 18.56 | |||

| 1542 | D | 0.90 | 0.25 | 2.08 | 1.04 | 232.00 | 2.00 | 427.00 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 2.33 | 1388.89 | 116.00 | 0.11 | 2.33 | 0.53 | 27.78 | 2.00 | ||

| 1557 | 1.18 | 0.24 | 3.33 | 0.91 | 282.00 | 3.66 | 429.00 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 3.57 | 555.81 | 77.00 | 0.07 | 3.57 | 0.56 | 20.34 | 3.66 | |||

| 1569 | 1.24 | 0.36 | 3.89 | 1.25 | 314.00 | 3.11 | 428.00 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 4.25 | 932.91 | 101.00 | 0.08 | 4.25 | 0.54 | 29.03 | 3.11 | |||

| 1611 | 1.16 | 0.49 | 4.97 | 0.82 | 428.00 | 6.06 | 422.00 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 5.46 | 696.94 | 71.00 | 0.09 | 5.46 | 0.44 | 42.24 | 6.06 |

| Well | Depth | TOC | Weight | SAT | ARO | NSO | ASPH | δSat13‰ | δAro13‰ | CV | Pr/Ph | Pr/n-C17 | Ph/n-C18 | CPI | C27% | C28% | Rock Formation | Organic Microfacies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangesh-1 | 2397 | 0.98 | 8.6 | 0.87 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.96 | Barsarin | D | |||||||||

| 2484 | 1.1 | 33.6 | 13.42 | 9.4 | 28.19 | 48.99 | −27.9 | −27.7 | −2.55 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.3 | 0.97 | 53.2 | 14.7 | Naokelekan | B | |

| 2631 | 0.62 | 75.7 | 9.25 | 10.98 | 20.23 | 59.54 | −27.5 | −27.2 | −2.47 | 0.66 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.86 | 55.9 | 16 | Sargelu | C | |

| Sheikhan-8 | 1509 | 2.36 | 22 | 11.7 | 12.9 | 33.06 | 42.34 | −28.3 | −28 | −2.21 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.56 | 1.04 | 49.9 | 15.4 | Barsarin | B |

| 1569 | 1.24 | 1 | 42.62 | 21.02 | 20.45 | 15.91 | −27.7 | −27.7 | −3.06 | 1.04 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 1.28 | 56.6 | 15.2 | D | ||

| 1629 | 4.16 | 62.4 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.94 | Naokelekan | A | ||||||||||

| 1664 | 4.48 | 96.1 | 16.4 | 6.67 | 12.31 | 64.62 | −28.2 | −28.1 | −2.68 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 53.2 | 14.7 | A | ||

| Well | Depth | C29% | Dia/Ster | C19/C23 | C22/C21 | C23/C24 | C26/C25 | C24TT/C26T | C24T/H | G/C30H | C29/C30 | Diahop/Hop | C35/C34 | TT/Hop | C32S | DBT/P | Rock Formation | Organic microfacies |

| Mangesh-1 | 2397 | Barsarin | D | |||||||||||||||

| 2484 | 32.1 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.82 | 2.78 | 0.65 | 4.96 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.75 | 0.02 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.62 | 1.76 | Naokelekan | B | |

| 2631 | 28.1 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 1.17 | 2.99 | 0.64 | 8.36 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.82 | 0.2 | 0.62 | 2.25 | Sargelu | C | |

| Sheikhan-8 | 1509 | 34.7 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 1.43 | 3.99 | 0.62 | 9.24 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.62 | 1.54 | Barsarin | B |

| 1569 | 28.2 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.86 | 3 | 0.82 | 5.1 | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.6 | 2.97 | D | ||

| 1629 | Naokelekan | A | ||||||||||||||||

| 1664 | 32.1 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 1.01 | 3.52 | 0.71 | 14.46 | 0.68 | 0.24 | 0.71 | 0.01 | 0.81 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 2.22 | A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Auqadi, R.S.; Mamaseni, W.J.; Mahdi, A.Q.; Akram, R.K.; Makled, W.A.; Al-Juboury, A.I.; Gentzis, T.; Kamel, A.; Omar, N.; El Garhy, M.M.; et al. Classification and Depositional Modeling of the Jurassic Organic Microfacies in Northern Iraq Based on Petrographic and Geochemical Characterization: An Approach to Hydrocarbon Source Rock Evaluation. Minerals 2025, 15, 1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111202

Al-Auqadi RS, Mamaseni WJ, Mahdi AQ, Akram RK, Makled WA, Al-Juboury AI, Gentzis T, Kamel A, Omar N, El Garhy MM, et al. Classification and Depositional Modeling of the Jurassic Organic Microfacies in Northern Iraq Based on Petrographic and Geochemical Characterization: An Approach to Hydrocarbon Source Rock Evaluation. Minerals. 2025; 15(11):1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111202

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Auqadi, Rahma Sael, Wrya J. Mamaseni, Adnan Q. Mahdi, Revan K. Akram, Walid A. Makled, Ali Ismail Al-Juboury, Thomas Gentzis, Asmaa Kamel, Nagham Omar, Mohamed Mahmoud El Garhy, and et al. 2025. "Classification and Depositional Modeling of the Jurassic Organic Microfacies in Northern Iraq Based on Petrographic and Geochemical Characterization: An Approach to Hydrocarbon Source Rock Evaluation" Minerals 15, no. 11: 1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111202

APA StyleAl-Auqadi, R. S., Mamaseni, W. J., Mahdi, A. Q., Akram, R. K., Makled, W. A., Al-Juboury, A. I., Gentzis, T., Kamel, A., Omar, N., El Garhy, M. M., & Alarifi, N. (2025). Classification and Depositional Modeling of the Jurassic Organic Microfacies in Northern Iraq Based on Petrographic and Geochemical Characterization: An Approach to Hydrocarbon Source Rock Evaluation. Minerals, 15(11), 1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111202