Mineralogical and Spectroscopic Investigation of Turquoise from Dunhuang, Gansu

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

3. Test Results and Analysis

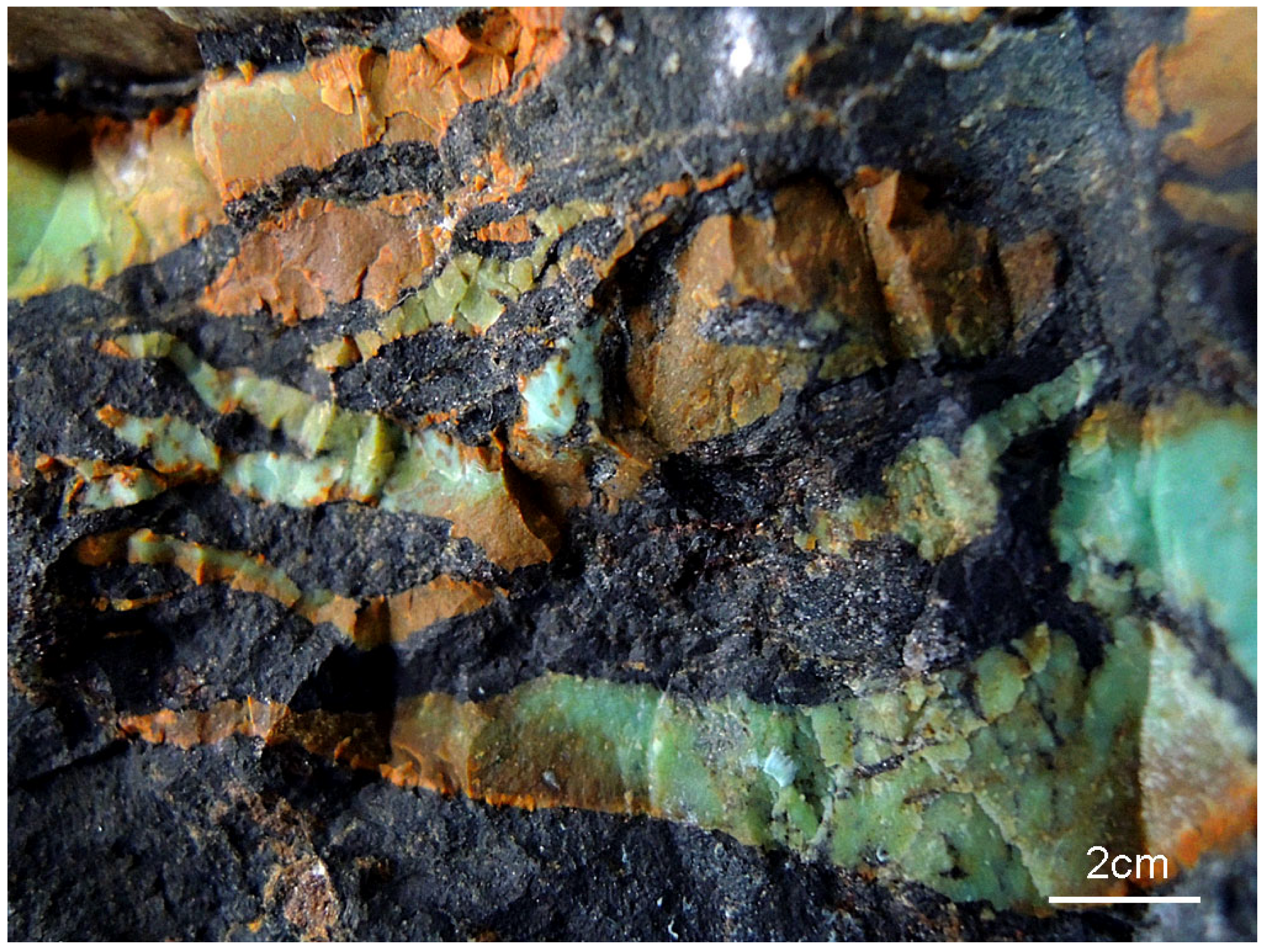

3.1. Conventional Gemological Characteristics

3.2. Material Composition

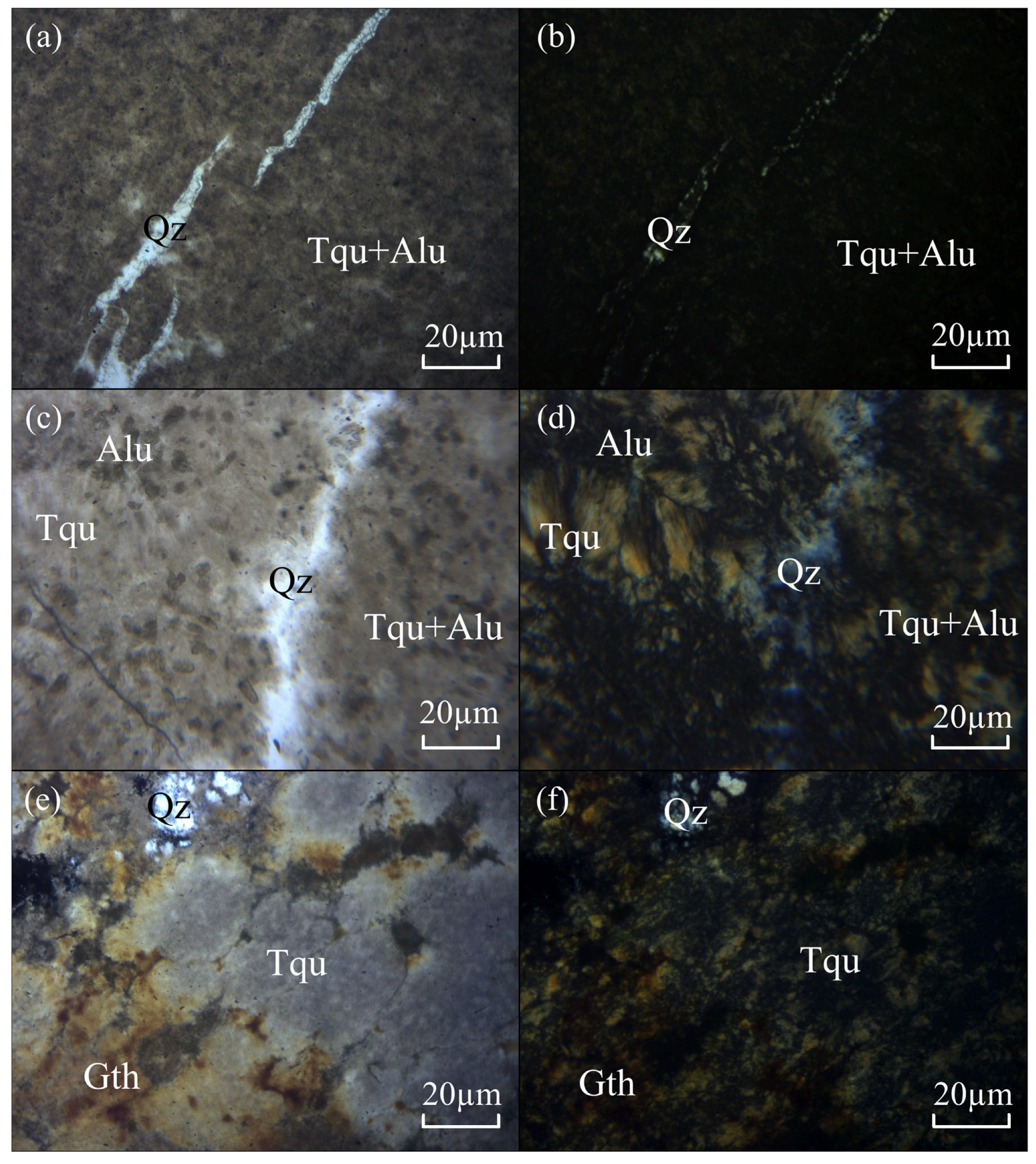

3.2.1. Polarizing Microscope

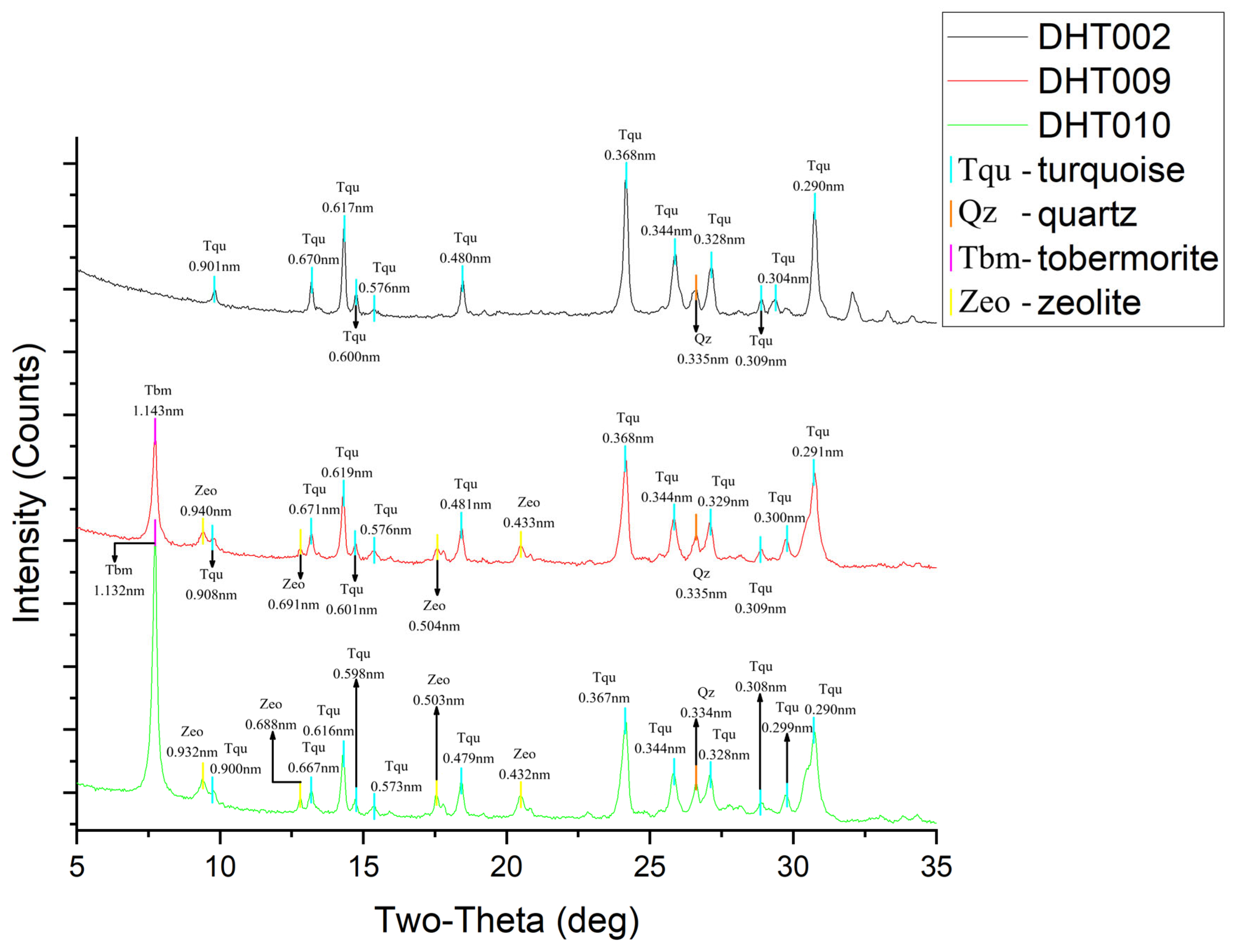

3.2.2. X-Ray Powder Diffraction

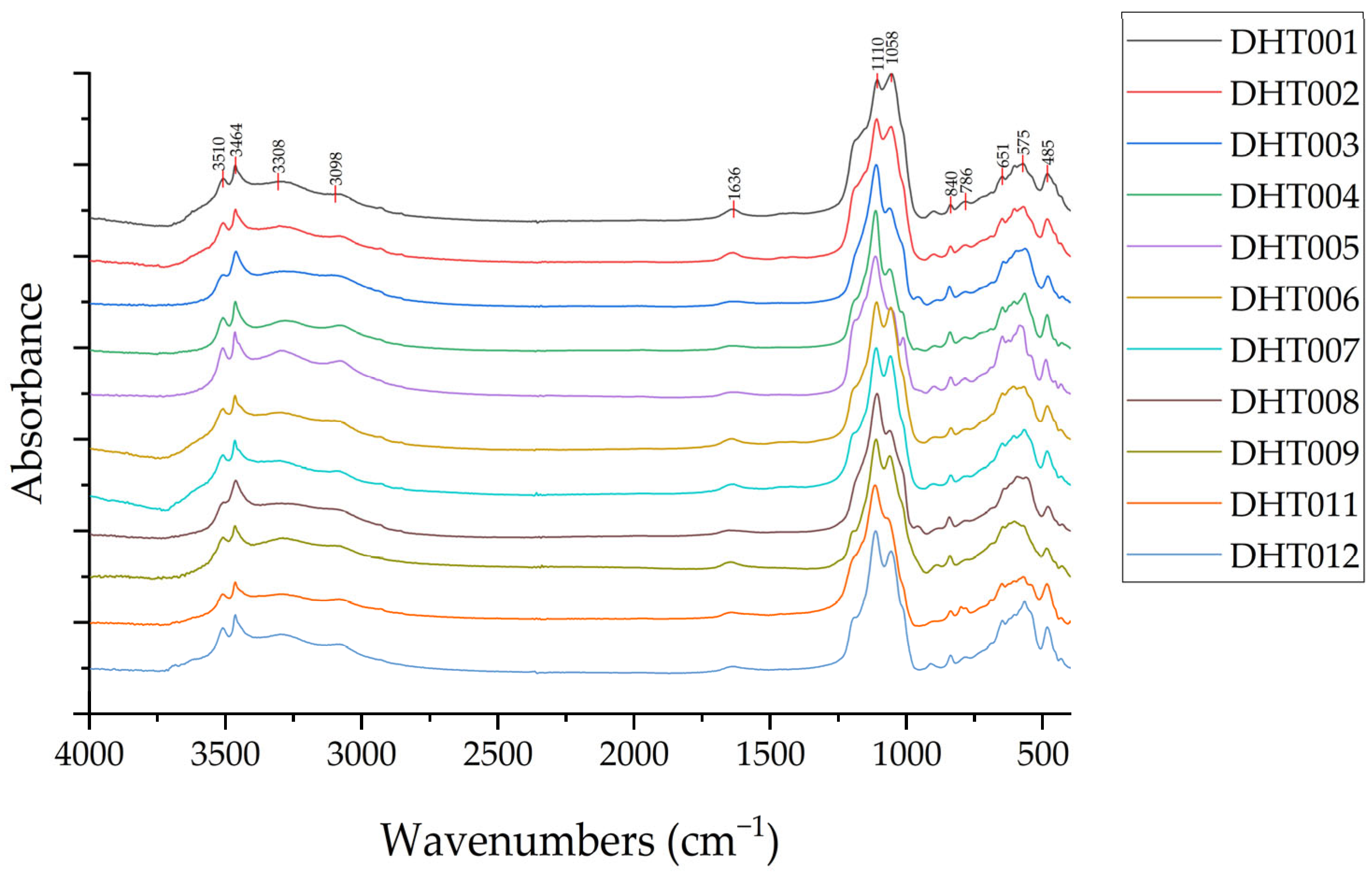

3.2.3. Infrared Spectroscopy

- Vibrational Spectra of Structural Water

- 2.

- Vibrational Spectra of Crystalline Water

- 3.

- Vibrational Spectra of Phosphate Groups

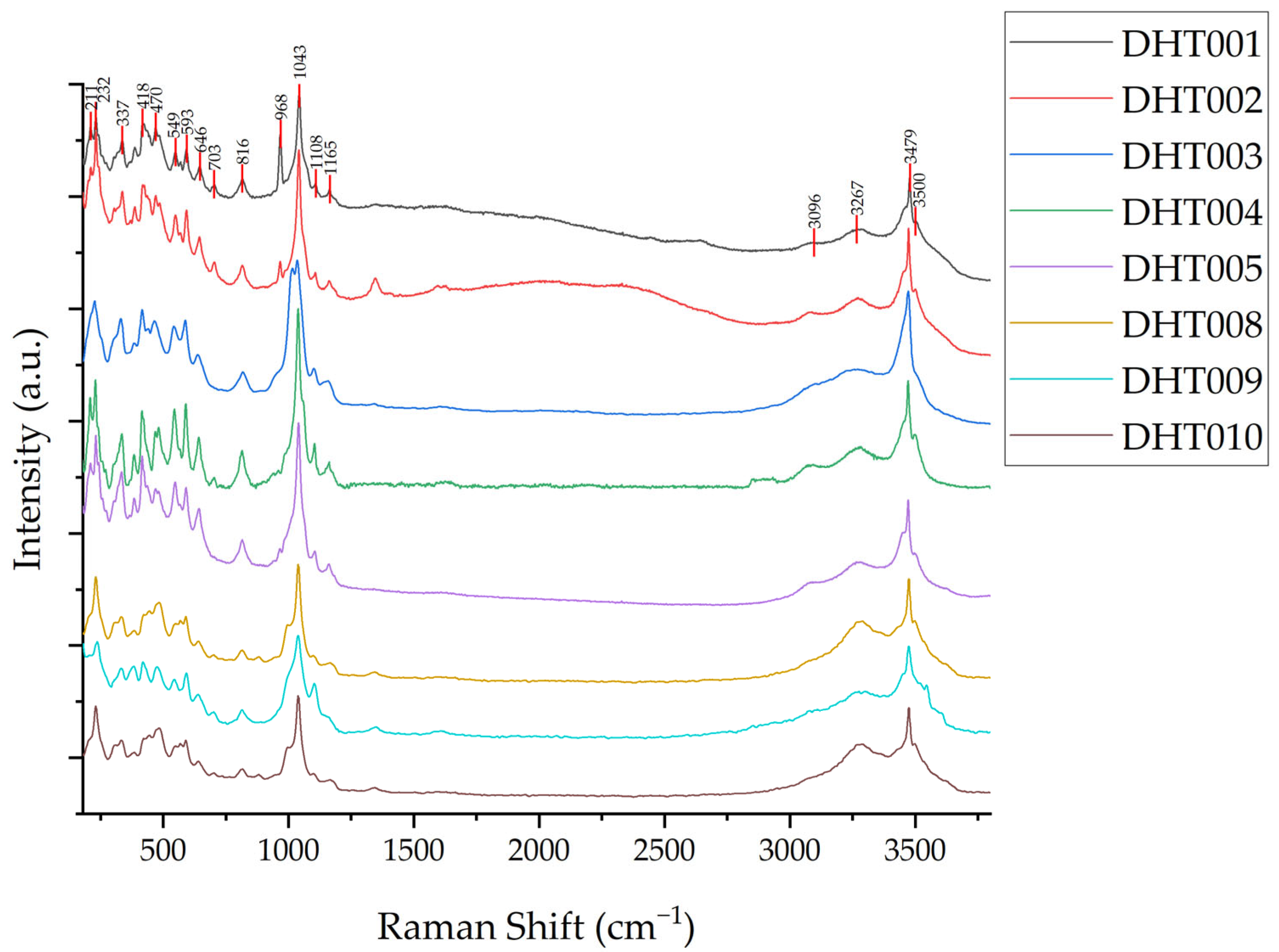

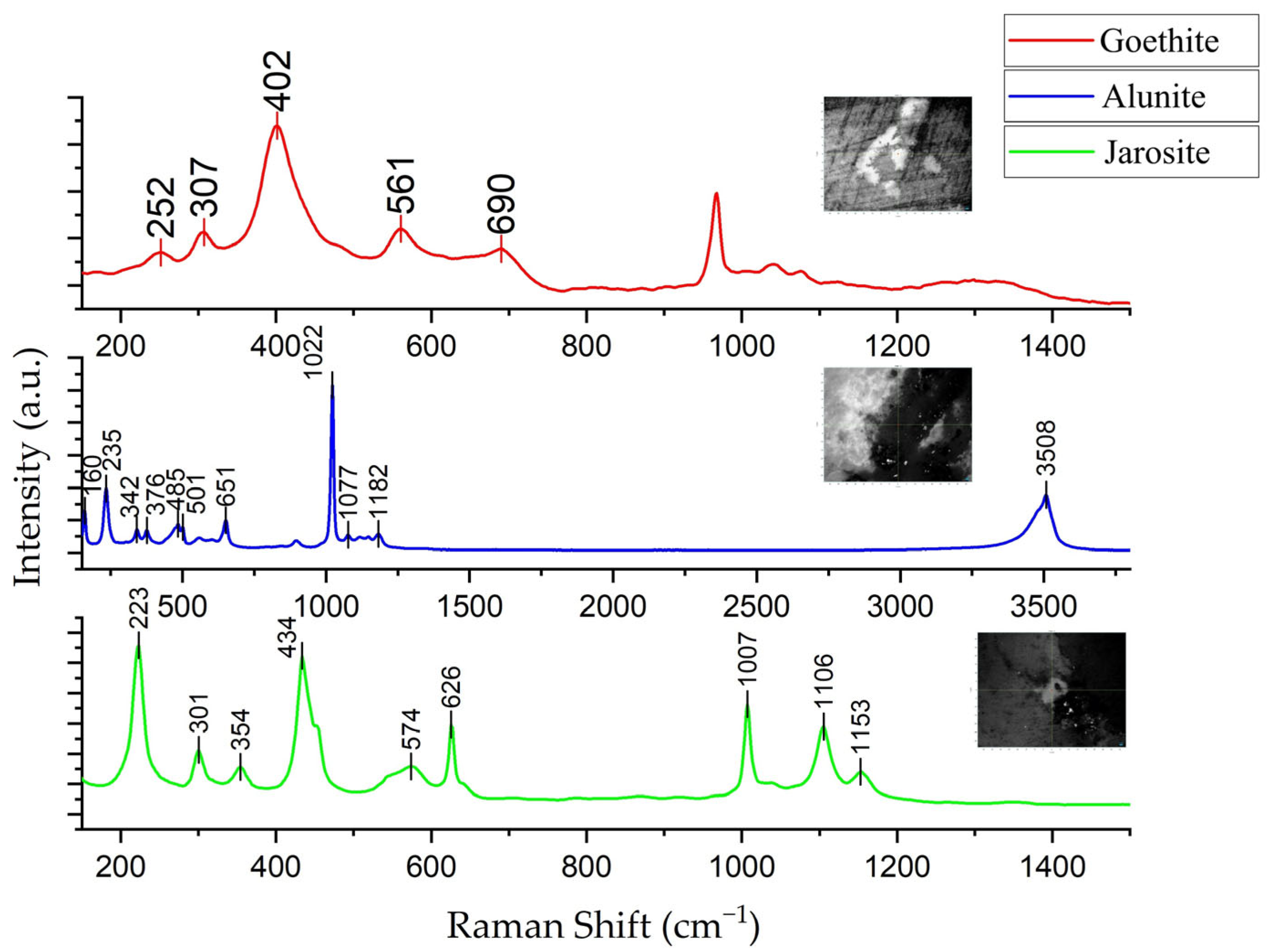

3.2.4. Raman Spectroscopy

- Vibrational Spectra of Structural Water

- 2.

- Vibrational Spectra of Crystalline Water

- 3.

- Vibrational Spectra of Phosphate Groups

3.3. Chemical Composition

3.3.1. Electron Probe Microanalysis

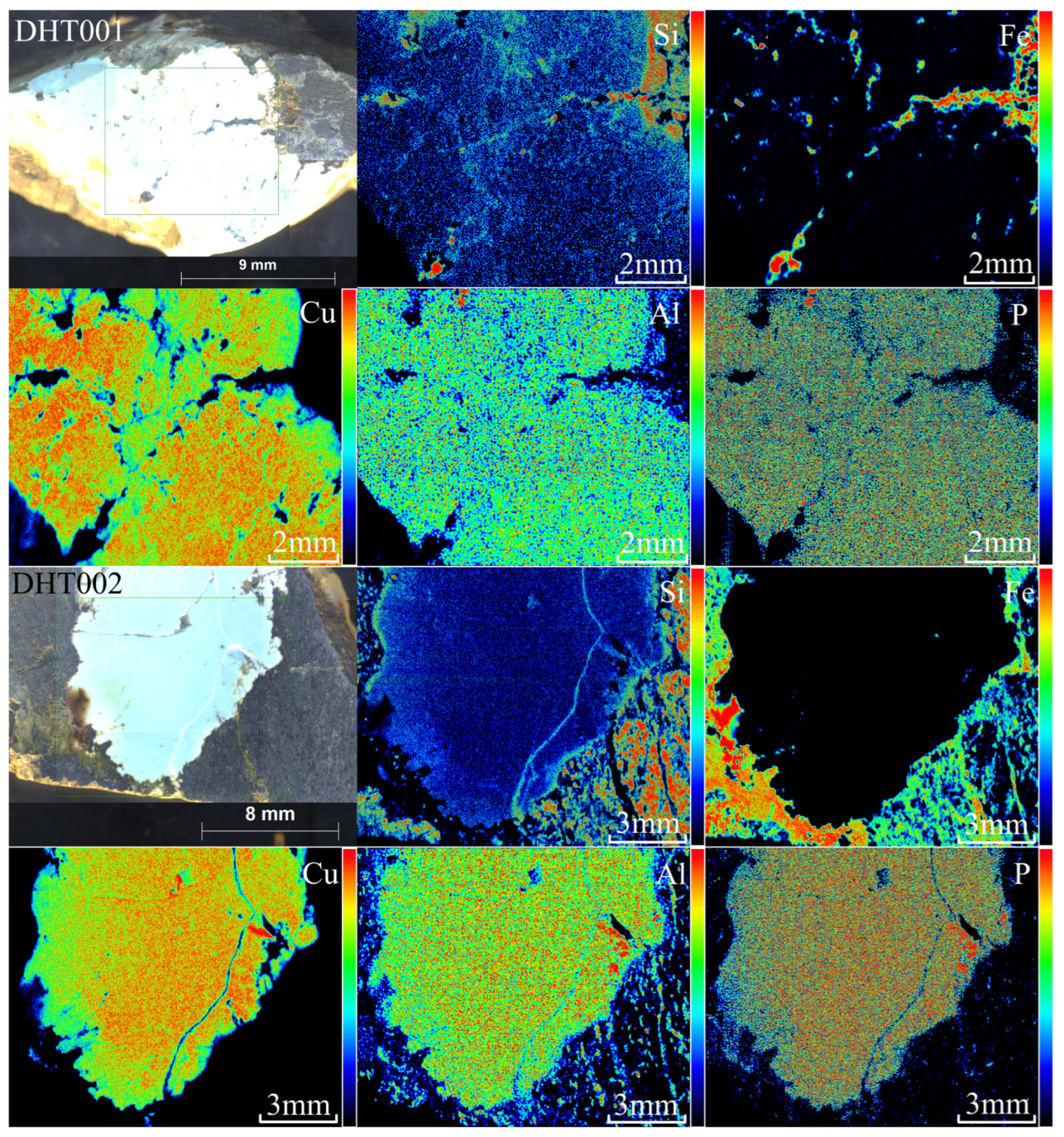

3.3.2. XRF Mapping Analysis

3.3.3. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopic Analysis

4. Conclusions

- The selected Dunhuang turquoise samples in this study have a density ranging from 2.40 to 2.77 g/cm3 and a refractive index between 1.59 and 1.65.

- The chemical composition of the turquoise samples from this area is characterized by a high content of Fe and Si and a low content of Cu. The specific oxide content ranges are: w(P2O5) between 23.83% and 33.66%, w(Al2O3) between 26.47% and 33.36%, w(CuO) between 5.26% and 7.91%, w(FeOT) between 2.46% and 4.11%, and w(SiO2) between 0.97% and 10.75%. Si and Fe are not incorporated into the crystal structure of the turquoise mineral but instead exist as secondary, micron-scale independent mineral phases (quartz, goethite and alunite).

- In the infrared absorption spectra of Dunhuang turquoise, the bands caused by ν(OH)− stretching vibrations are located at 3510 cm−1 and 3464 cm−1, respectively. The bands near 3308 cm−1 and 3098 cm−1 are assigned to ν(M-H2O) stretching vibrations. The bands caused by v[PO4]3− stretching vibrations are located near 1110 cm−1 and 1058 cm−1. The bands near 651 cm−1, 575 cm−1, and 485 cm−1 are assigned to δ[PO4]3− bending vibrations. The band near 1636 cm−1 is caused by δ(M-H2O) bending vibrations. The bands near 840 cm−1 and 786 cm−1 are caused by δ(OH)− bending vibrations.

- The Raman peaks in Dunhuang turquoise caused by ν(OH)− stretching vibrations are located near 3500 and 3479 cm−1, while the peaks near 3267 and 3096 cm−1 are attributed to ν(M-H2O) stretching vibrations. Raman peaks resulting from the asymmetric stretching vibration (v3) of phosphate groups appear near 1165, 1108, 1043, and 968 cm−1. Peaks due to in-plane bending vibration (v4) are observed near 646, 593, and 549 cm−1, and those from out-of-plane bending vibration (v2) appear near 470 and 418 cm−1. The Raman peak near 1625 cm−1, attributed to δ(M-H2O) bending vibration, could not be observed due to fluorescence interference. The peak near 816 cm−1 is caused by δ(OH)− bending vibration. Additionally, Raman peaks resulting from lattice vibrations were observed near 337, 232, and 209 cm−1.

- The hue and chroma of Dunhuang turquoise are primarily controlled by the mass fractions of Fe3+, Cu2+, and Fe2+, and the form of their hydrated ions. In the UV-Vis spectra, the absorption peak caused by O2−–Fe3+ charge transfer is mainly located near 259 nm; the characteristic absorption peak near 426 nm originates from the 6A1g → 4Eg + 4A1g (4G) d-d electronic transition of Fe3+ in [Fe(H2O)6]3+. The broad, gentle absorption band starting beyond 691 nm should be attributed to the 2Eg → 2T2g (2D) d-d electronic transition of Cu2+ in [Cu(H2O)4]2+.

- Results from polarizing microscope observation, XRD, electron probe microanalysis, and XRF mapping indicate that the Dunhuang turquoise is distributed in a finely dispersed form with particle diameters smaller than 10 μm. Associated minerals include goethite, alunite, jarosite, quartz, and others. These minerals infiltrated along fractures and replaced the primary turquoise body after its formation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| XRD | X-ray powder diffraction |

| EPMA | electron probe microanalysis |

| UV-Vis | ultraviolet-visible |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

References

- Zalinski, E.R. Turquoise in the Burro Mountains, New Mexico. Econ. Geol. 1907, 2, 464–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Song, G.; He, Y. The Identification of Binding Agent Used in Late Shang Dynasty Turquoise-Inlayed Bronze Objects Excavated in Anyang. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 59, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.; Fayek, M.; Mathien, F.J.; Roberts, H. Turquoise Trade of the Ancestral Puebloan: Chaco and Beyond. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 45, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedquist, S.L.; Thibodeau, A.M.; Welch, J.R.; Killick, D.J. Canyon Creek Revisited: New Investigations of a Late Prehispanic Turquoise Mine, Arizona, USA. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 87, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, E.; McClure, S.F.; Ostrooumov, M.; Andres, Y.; Moses, T.; Koivula, J.I.; Kammerling, R.C. The Identification of Zachery-Treated Turquoise. Gems Gemol. 1999, 35, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Li, D.; Zhu, L.; Song, S.; Liu, Y.; Shen, C. Study on Mineralogical and Spectroscopic Characteristics of Turquoise from Hami, Xinjiang. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2018, 38, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Liu, Y. A Study on Gemological and Mineralogical Characteristics of American Sleeping Beauty Turquoise. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2014, 33, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, L.; Wen, H.; Shirdam, B.; Shen, X. Mineralogical and Spectroscopic Characteristics of Turquoise and Associated Minerals from Baghu, Iran. J. Gems Gemmol. 2023, 25, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. Gemological and Mineralogical Study of Baihe Turquoise from Shaanxi Province. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Qi, L.; Dai, H.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, X. Study on the Gemological Characteristics of Dian’anshan Turquoise from Anhui Province. J. Gems Gemmol. 2013, 15, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shi, G.; Wang, Y.; Ren, J.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, H. Significance and Characteristics of FTIR and Raman Spectra of High-Quality Turquoise from Hubei and Anhui Provinces. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2018, 38, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. A Comparative Study of Natural and Treated Turquoise from Zhushan, Hubei. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xian, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Gao, Z.; Wen, R. Mineralogical Characteristics of Xichuan Turquoise from Henan Province Studied by SEM-XRD-EPMA. Rock. Miner. Anal. 2019, 38, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, M.; Li, Q.; Tang, Y.; Wen, H.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Turquoise from Tianhu East, Xinjiang, China. Gems Gemol. 2024, 60, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, T.; Schmetzer, K.; Bank, H. The Identification of Turquoise by Infrared Spectroscopy and X-Ray Powder Diffraction. Gems Gemol. 1983, 19, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fuquan, W. A Gemological Study of Turquoise in China. Gems Gemol. 1986, 22, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yin, Z.; Qi, L.; Xiong, Y. Turquoise from Zhushan County, Hubei Province, China. Gems Gemol. 2012, 48, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, M.; Li, Y. Unique Raindrop Pattern of Turquoise from Hubei, China. Gems Gemol. 2020, 56, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, Y. Spectral Study of Associated Minerals of Yellow-Green to Green Turquoise from Zhushan, Hubei Province. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2020, 40, 1815–1820. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, Y.; Yang, M. Spectral Characteristics of Blue “Water Wave Pattern” Turquoise from Shiyan, Hubei Province. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2021, 41, 636–642. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Yang, M.; Liu, L. Mineralogical and Spectral Characteristics of Alunite from the Xiaodonggou Turquoise Deposit in Baihe, Shaanxi Province. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2023, 43, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Nie, F.; Jiang, S.; Bai, D.; Wang, X.; Su, X. REE Geochemical Study of the Dunhuang Fangshankou Large-Scale Vanadium-Phosphorus-Uranium Deposit. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2003, 22, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Nie, F.; Jiang, S.; Bai, D. Geological Characteristics and Genesis of the Dunhuang Fangshankou Large-Scale Vanadium-Phosphorus-Uranium Deposit. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2002, 23, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Dun, J.-H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yuan, Y. Spectroscopic Characteristics Study of Turquoise from Nanhuatang, Shiyan, Hubei Province. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2025, 45, 2467–2474. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Chen, H.; Luo, Q. Application of GemDialogue and GemSet Colour System in Colour Description and Grading of Coloured Gemstones. J. Gems Gemmol. 2005, 7, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemological Institute of America. GIA Gem Laboratory Identification Manual, 2nd ed.; China University of Geosciences Press: Wuhan, China, 2005; pp. 111–112. ISBN 7-5625-2057-7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z. A Method for Quantitative Analysis of Whole-Rock Mineral Composition: A Case Study of Samples from the 9th Renou Cup. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2025, 45, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foord, E.E.; Taggart, J.E., Jr. A Reexamination of the Turquoise Group: The Mineral Aheylite, Planerite (Redefined), Turquoise and Coeruleolactite. Mineral. Mag. 1998, 62, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L.; Reddy, B.J.; Martens, W.N.; Weier, M. The Molecular Structure of the Phosphate Mineral Turquoise—A Raman Spectroscopic Study. J. Mol. Struct. 2006, 788, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Čejka, J.; Sejkora, J.; Macek, I.; Malíková, R.; Wang, L.; Scholz, R.; Xi, Y.; Frost, R.L. Raman and Infrared Spectroscopic Study of Turquoise Minerals. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 149, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrodier, I.; Farges, F.; Benedetti, M.; Winterer, M.; Brown, G.E.; Deveughèle, M. Adsorption Mechanisms of Trivalent Gold on Iron- and Aluminum-(Oxy)Hydroxides. Part 1: X-Ray Absorption and Raman Scattering Spectroscopic Studies of Au(III) Adsorbed on Ferrihydrite, Goethite, and Boehmite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2004, 68, 3019–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Faria, D.L.A.; Lopes, F.N. Heated Goethite and Natural Hematite: Can Raman Spectroscopy Be Used to Differentiate Them? Vib. Spectrosc. 2007, 45, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L.; Wills, R.-A.; Weier, M.L.; Martens, W.; Theo Kloprogge, J. A Raman Spectroscopic Study of Alunites. J. Mol. Struct. 2006, 785, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maubec, N.; Lahfid, A.; Lerouge, C.; Wille, G.; Michel, K. Characterization of Alunite Supergroup Minerals by Raman Spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 96, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio, C.H.; Sharma, S.K.; Ming, L.-C.; Muenow, D.W. Raman Spectroscopic Investigation on Jarosite–Yavapaiite Stability. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2010, 75, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamou, A.; Manos, G.; Messios, N.; Georgiou, L.; Xydas, C.; Varotsis, C. Probing the Whole Ore Chalcopyrite–Bacteria Interactions and Jarosite Biosynthesis by Raman and FTIR Microspectroscopies. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, D. Study on Pseudomorphic Turquoise from the Ma’anshan Area, Anhui Province. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 1995, 14, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Lv, X.; Gong, Y.; Ni, J. The Coupling Relationship Between Turquoise Quality and Water and Its Characterization by Variable-Temperature Spectroscopy. J. Gems Gemmol. 2017, 19, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.; Dai, H.; Huang, W.; Yu, L.; Deng, W. UV-Vis Spectroscopy Characteristics and Color Characterization of Tongling Turquoise from Anhui Province. J. Gems Gemmol. 2020, 22, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. The Influence of Different Metal Ions and Adsorbed Water on Turquoise Color. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Composition Analysis and Study on the Color Genesis of Ma’anshan Turquoise from Anhui Province. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences Beijing, Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Structure | Description of Appearance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| DHT001 | Massive | Shows black veinlet permeation, contains minor scattered black and yellow veining |

| DHT002 | Massive | Relatively well-developed fractures, visible black veinlets and yellow veining |

| DHT003 | Massive | Well-developed fractures filled with yellow material |

| DHT004 | Massive | Well-developed fractures filled with yellow and black material, minor yellow veining visible |

| DHT005 | Massive | Shows black veinlet permeation, contains minor yellow veining |

| DHT006 | Massive | Shows brown veinlet permeation, contains yellow filamentous veining |

| DHT007 | Massive | Shows brown veinlet permeation, contains abundant yellow filamentous veining |

| DHT008 | Massive | Shows abundant scattered yellowish-brown veining |

| DHT009 | Massive | Relatively well-developed fractures filled with black material, minor yellowish-brown veining visible |

| DHT010 | Massive | Well-developed fractures filled with black and brown material, visible yellow veinlets |

| DHT011 | Massive | Shows brown veinlet permeation |

| DHT012 | Massive | Relatively well-developed fractures filled with black material, abundant yellowish-brown veining visible |

| Sample | Color | Density (g/cm3) | Refractive Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| DHT001 | B10 | 2.54 | - |

| DHT002 | B10 | 2.44 | 1.60 |

| DHT003 | G2B40 | 2.77 | 1.65 |

| DHT004 | G2B30 | 2.75 | 1.62 |

| DHT005 | G2B50 | 2.61 | 1.62 |

| DHT006 | B2G10 | 2.40 | 1.60 |

| DHT007 | B2G10 | 2.48 | 1.60 |

| DHT008 | B2G40 | 2.76 | 1.65 |

| DHT009 | B2G30 | 2.51 | - |

| DHT010 | B2G30 | 2.53 | - |

| DHT011 | B2G30 | 2.62 | 1.61 |

| DHT012 | B2G20 | 2.47 | - |

| PDF: 00-050-1655 Turquoise | PDF: 00-025-0260 Turquoise, Ferrian | DHT002 | DHT009 | DHT010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.898 | 0.898 | 0.901 | 0.908 | 0.900 |

| 0.670 | 0.671 | 0.670 | 0.671 | 0.667 |

| 0.616 | 0.622 | 0.617 | 0.619 | 0.616 |

| 0.599 | 0.603 | 0.600 | 0.601 | 0.598 |

| 0.574 | 0.576 | 0.576 | 0.576 | 0.573 |

| 0.479 | 0.483 | 0.480 | 0.481 | 0.479 |

| 0.367 | 0.370 | 0.368 | 0.368 | 0.367 |

| 0.342 | 0.346 | 0.344 | 0.344 | 0.344 |

| 0.332 | 0.331 | 0.328 | 0.329 | 0.328 |

| 0.308 | 0.307 | 0.309 | 0.309 | 0.308 |

| 0.290 | 0.291 | 0.290 | 0.291 | 0.290 |

| Sample | ν(OH)− | ν(M-H2O) | δ(M-H2O) | δ(OH)− | ν[PO4]3− | δ[PO4]3− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHT001 | 3510, 3464 | 3308, 3098 | 1636 | 840, 786 | 1110, 1058 | 651, 575, 485 |

| DHT002 | 3509, 3465 | 3303, 3080 | 1638 | 841, 784 | 1112, 1059 | 651, 573, 485 |

| DHT003 | 3507, 3463 | 3289, 3112 | 1627 | 844, 786 | 1113, 1064 | 646, 599, 483 |

| DHT004 | 3512, 3467 | 3287, 3087 | 1654 | 844, 789 | 1117, 1066 | 652, 570, 488 |

| DHT005 | 3511, 3466 | 3298, 3084 | 1639 | 840, 787 | 1116, 1060 | 650, 586, 490 |

| DHT006 | 3510, 3466 | 3298, 3100 | 1645 | 839, 780 | 1112, 1060 | 650, 571, 485 |

| DHT007 | 3510, 3466 | 3309, 3099 | 1636 | 840, 779 | 1113, 1061 | 650, 569, 486 |

| DHT008 | 3508, 3464 | 3293, 3111 | 1651 | 845, 785 | 1110, 1064 | 643, 593, 483 |

| DHT009 | 3510, 3466 | 3291, 3081 | 1653 | 842, 785 | 1114, 1064 | 648, 572, 487 |

| DHT011 | 3514, 3467 | 3304, 3086 | 1643 | 842, 785 | 1119, 1071 | 654, 575, 488 |

| DHT012 | 3511, 3465 | 3298, 3083 | 1643 | 840, 784 | 1115, 1059 | 650, 569, 485 |

| Comment | DHT001 | DHT002 | DHT004 | DHT005 | DHT009 | DHT010 | DHT011 | DHT012 | Hubei Zhushan [18] | Anhui Ma’anshan [37] | Theoretical Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2O5 | 23.83 | 24.15 | 33.66 | 33.65 | 26.88 | 25.64 | 27.00 | 24.25 | 31.69 | 31.06 | 34.1200 |

| Al2O3 | 26.47 | 26.98 | 32.13 | 33.36 | 27.34 | 26.89 | 30.42 | 27.20 | 33.50 | 33.46 | 36.8400 |

| CuO | 5.48 | 5.77 | 7.91 | 7.33 | 5.26 | 5.44 | 5.40 | 5.27 | 3.75 | 7.04 | 9.5700 |

| FeOT | 2.46 | 2.49 | 4.11 | 2.70 | 3.83 | 3.69 | 2.96 | 3.38 | 6.64 | 4.14 | —— |

| SiO2 | 20.00 | 19.49 | 1.56 | 0.97 | 9.36 | 10.75 | 9.65 | 13.99 | 0.50 | 3.70 | —— |

| Na2O | 2.97 | 3.13 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 6.84 | 6.49 | 2.80 | 7.33 | 0.03 | Total 0.88 | —— |

| MgO | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.01 | —— | |

| K2O | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.20 | 0.86 | 0.02 | —— | |

| TiO2 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | —— | |

| SO3 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.13 | —— | —— | —— |

| CaO | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.24 | 1.24 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.01 | —— | —— |

| BaO | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | —— | —— | —— |

| ZnO | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.04 | —— | —— |

| MnO | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | —— | —— | —— |

| Cr2O3 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.04 | —— | —— | —— |

| V2O3 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.08 | —— | —— | —— |

| H2O | 19.47 | 19.47 | 19.47 | 19.47 | 19.47 | 19.47 | 19.47 | 19.47 | 22.82 | 18.36 | 19.47 |

| Total | 102.53 | 103.57 | 100.33 | 100.26 | 100.69 | 100.13 | 99.03 | 102.61 | 99.03 | 98.64 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, D.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; Lin, J.; Yan, M.; Sun, Y. Mineralogical and Spectroscopic Investigation of Turquoise from Dunhuang, Gansu. Minerals 2025, 15, 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111199

Xu D, Zhou Z, Chen Q, Lin J, Yan M, Sun Y. Mineralogical and Spectroscopic Investigation of Turquoise from Dunhuang, Gansu. Minerals. 2025; 15(11):1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111199

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Duo, Zhengyu Zhou, Qi Chen, Jiaqing Lin, Ming Yan, and Yarong Sun. 2025. "Mineralogical and Spectroscopic Investigation of Turquoise from Dunhuang, Gansu" Minerals 15, no. 11: 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111199

APA StyleXu, D., Zhou, Z., Chen, Q., Lin, J., Yan, M., & Sun, Y. (2025). Mineralogical and Spectroscopic Investigation of Turquoise from Dunhuang, Gansu. Minerals, 15(11), 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111199