Multidisciplinary Constraints on the Lithospheric Architecture of the Eastern Heihe-Hegenshan Suture (NE China) from Magnetotelluric Imaging and Laboratory-Based Conductivity Experiment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedures and Data Acquirement

2.1. Magnetotellurics (MT)

2.2. Analysis of Rock Composition

2.3. In Situ Electrical Conductivity Measurement

3. Results

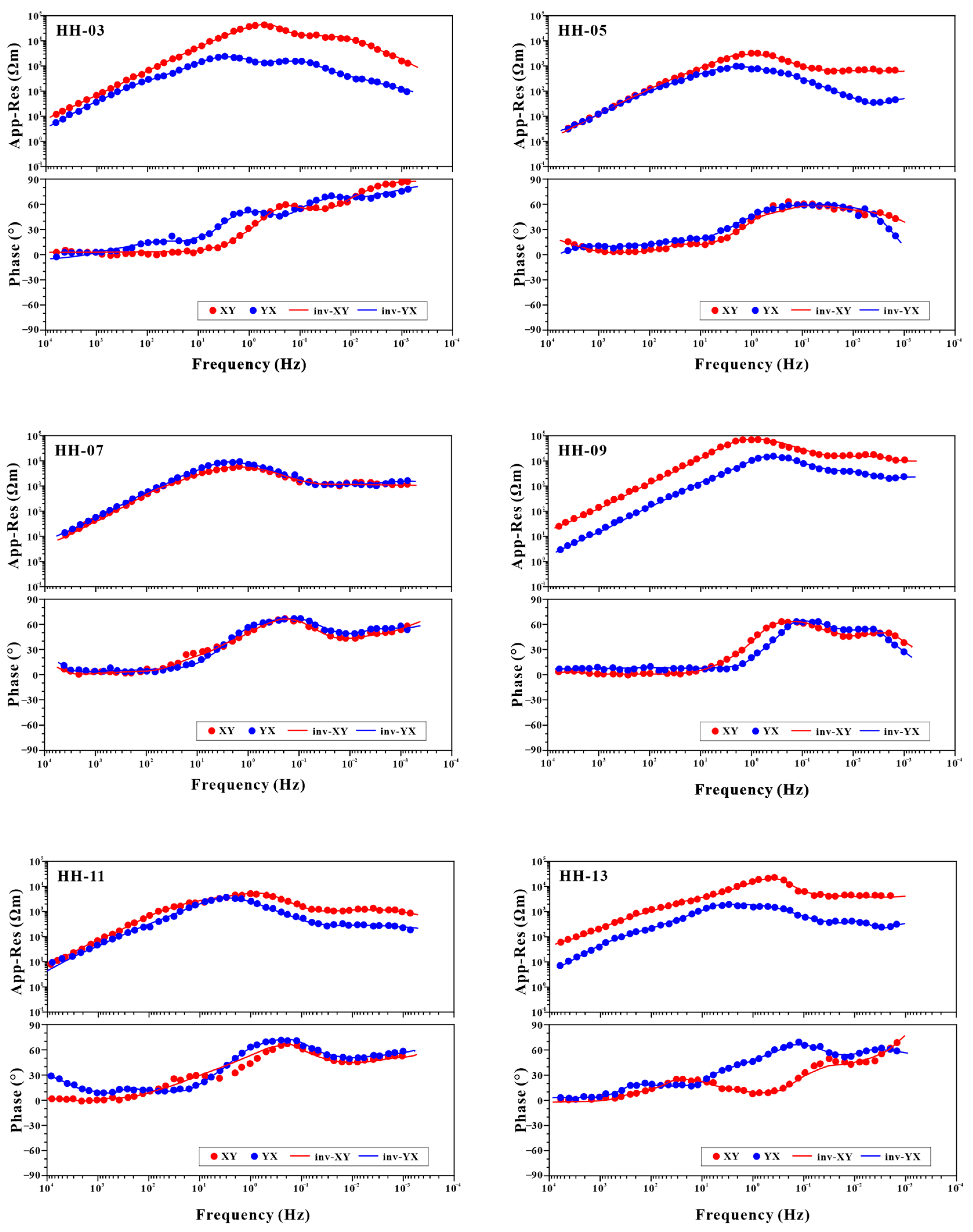

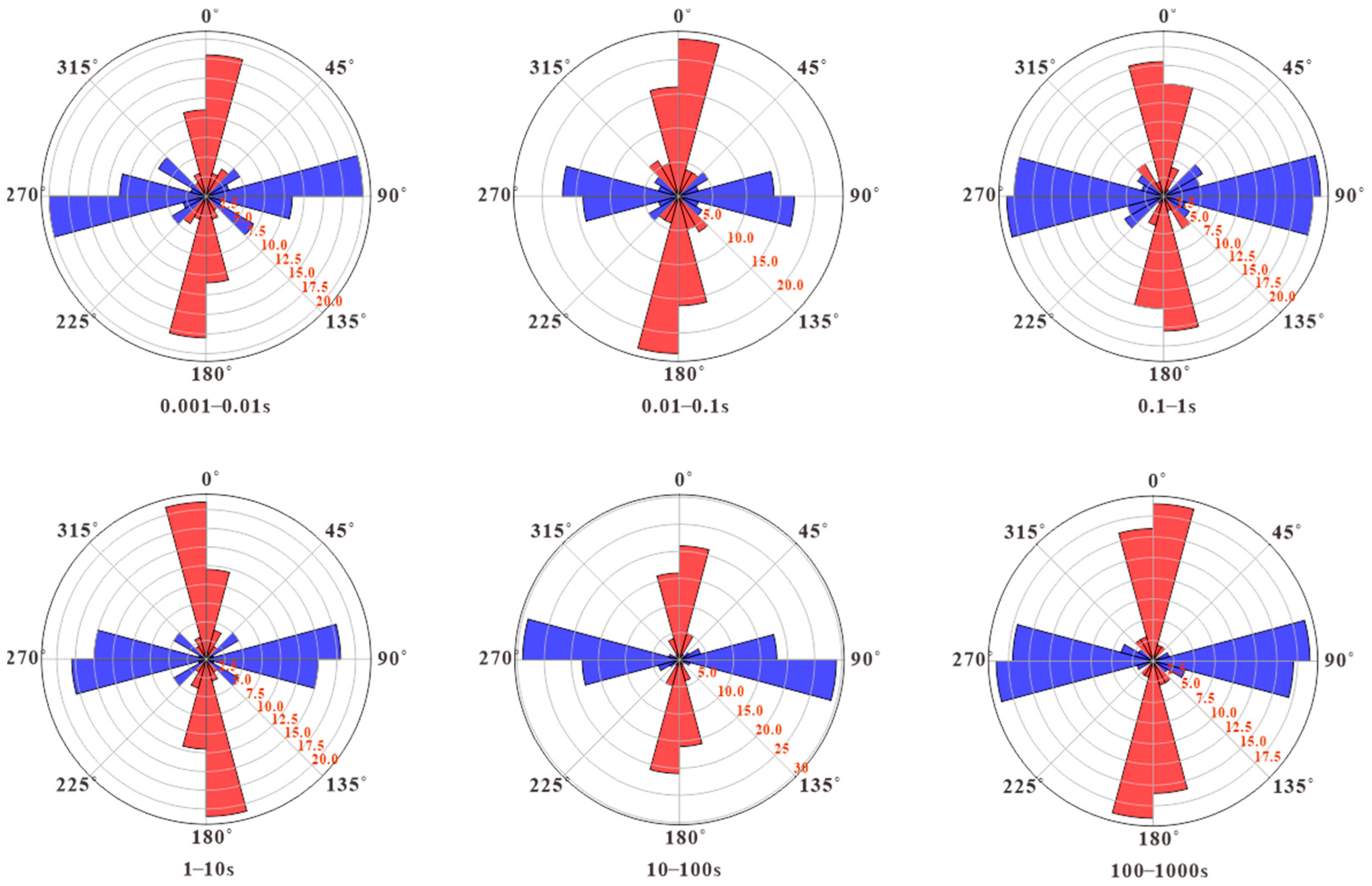

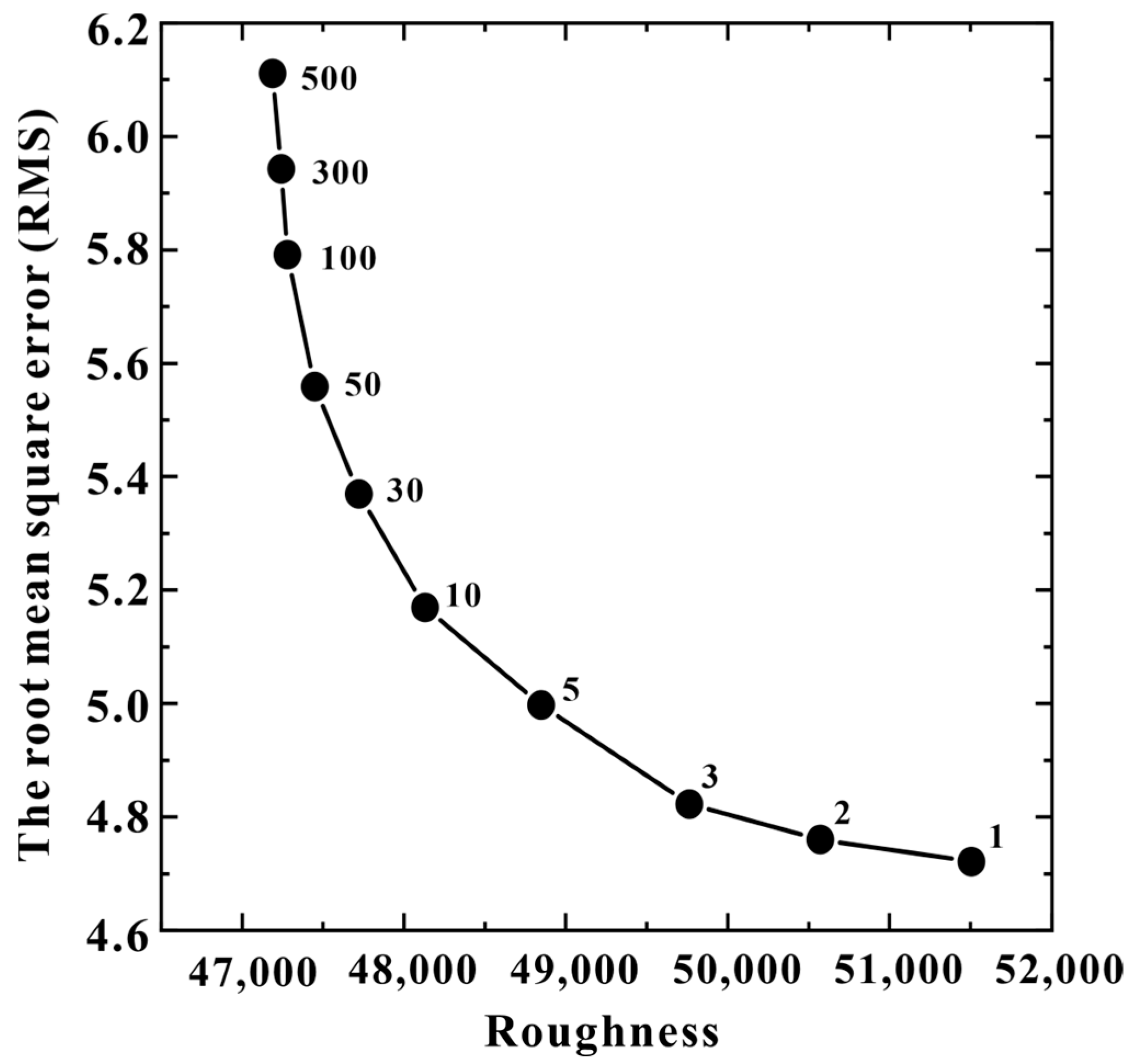

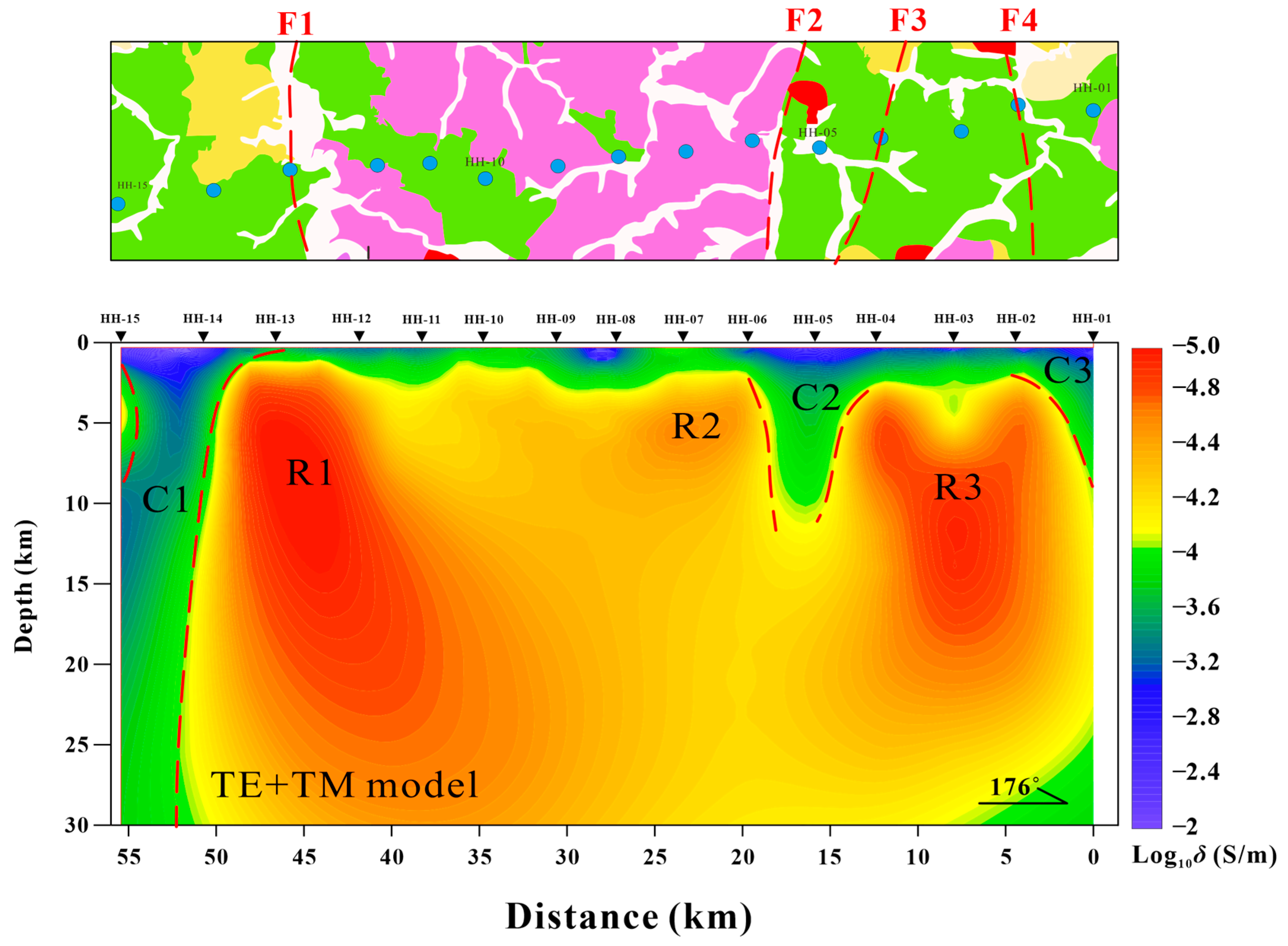

3.1. Magnetotellurics (MT)

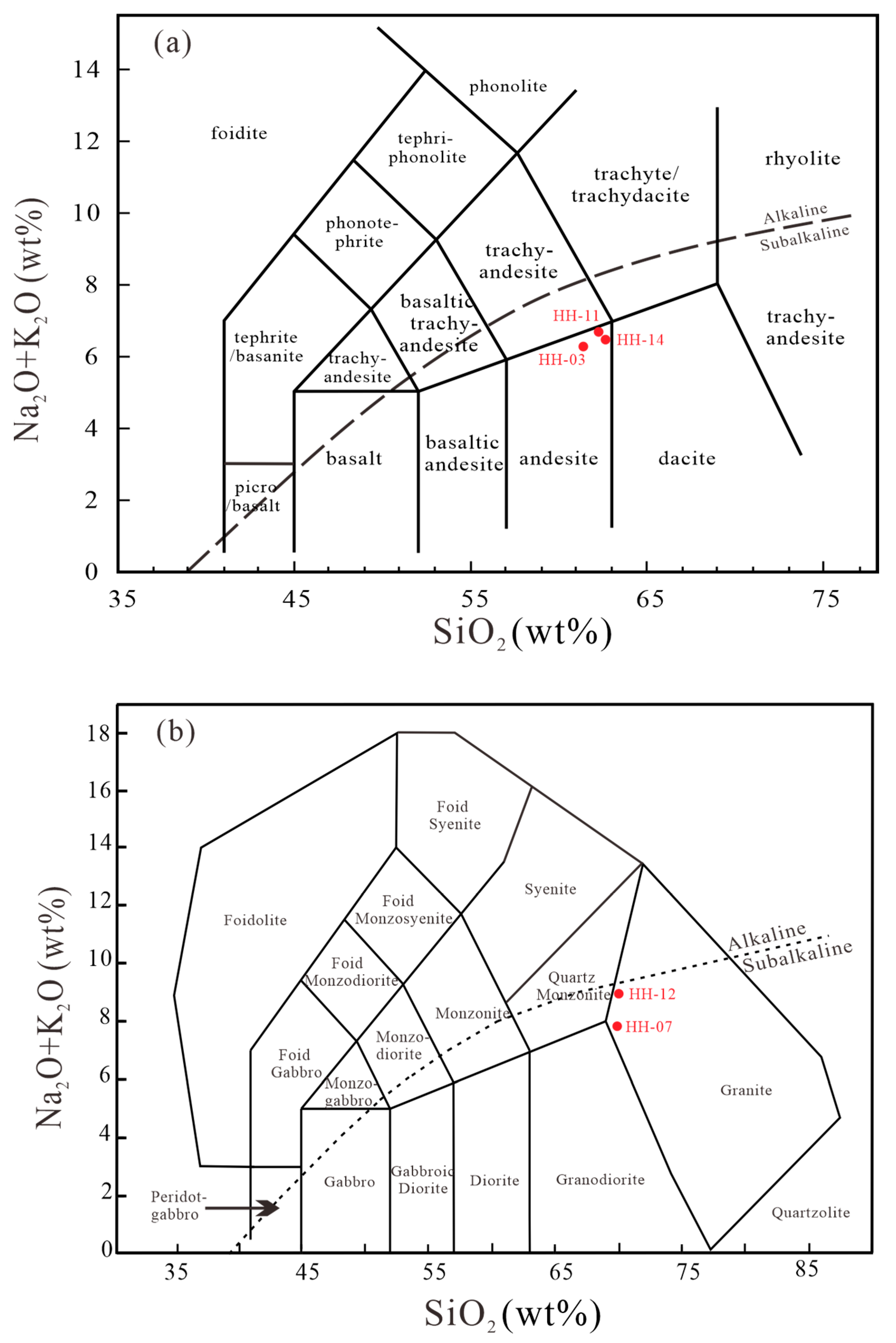

3.2. Analysis of Rock Composition

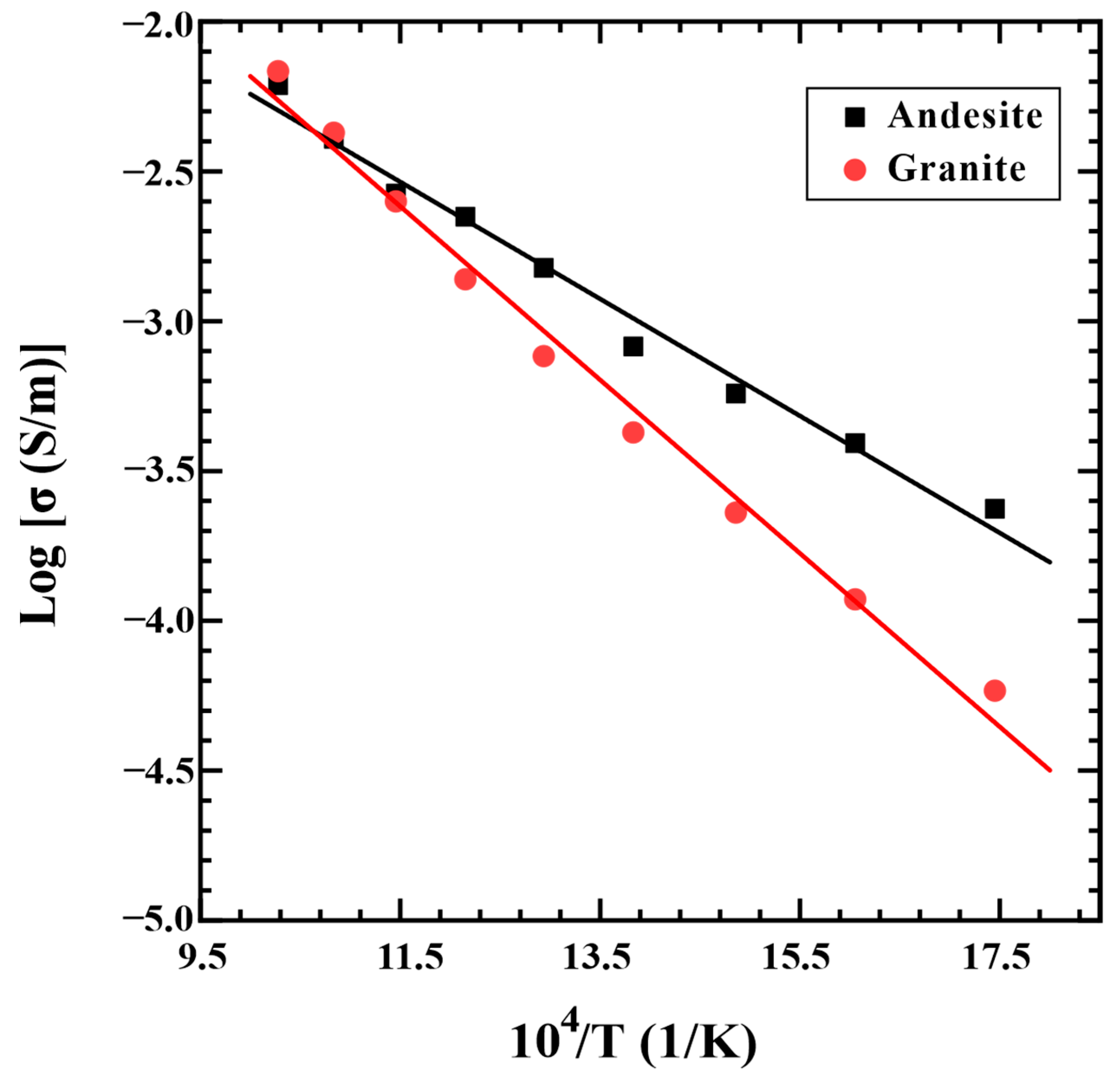

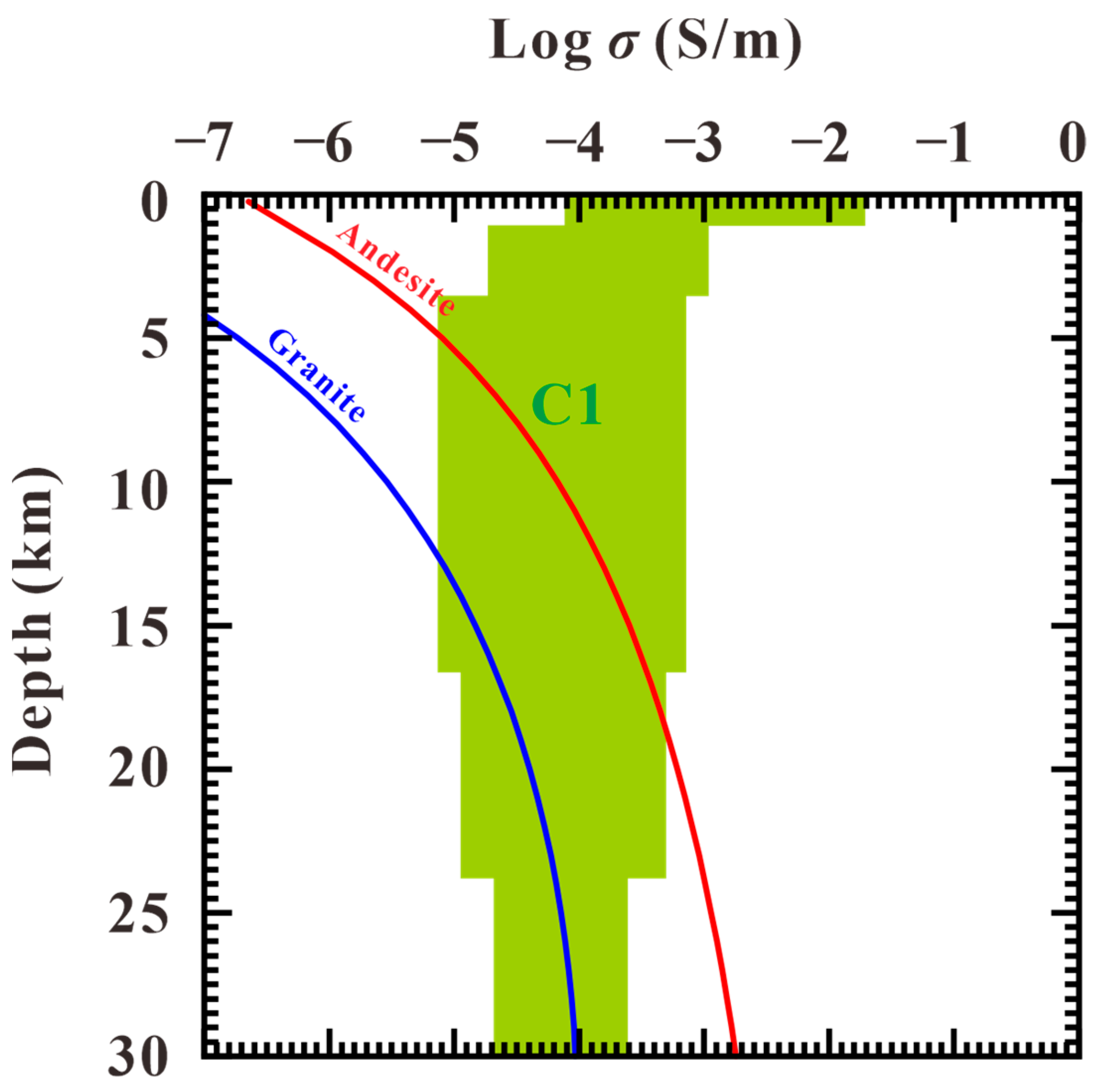

3.3. In-Suit Electrical Conductivity Measurement

4. Discussion

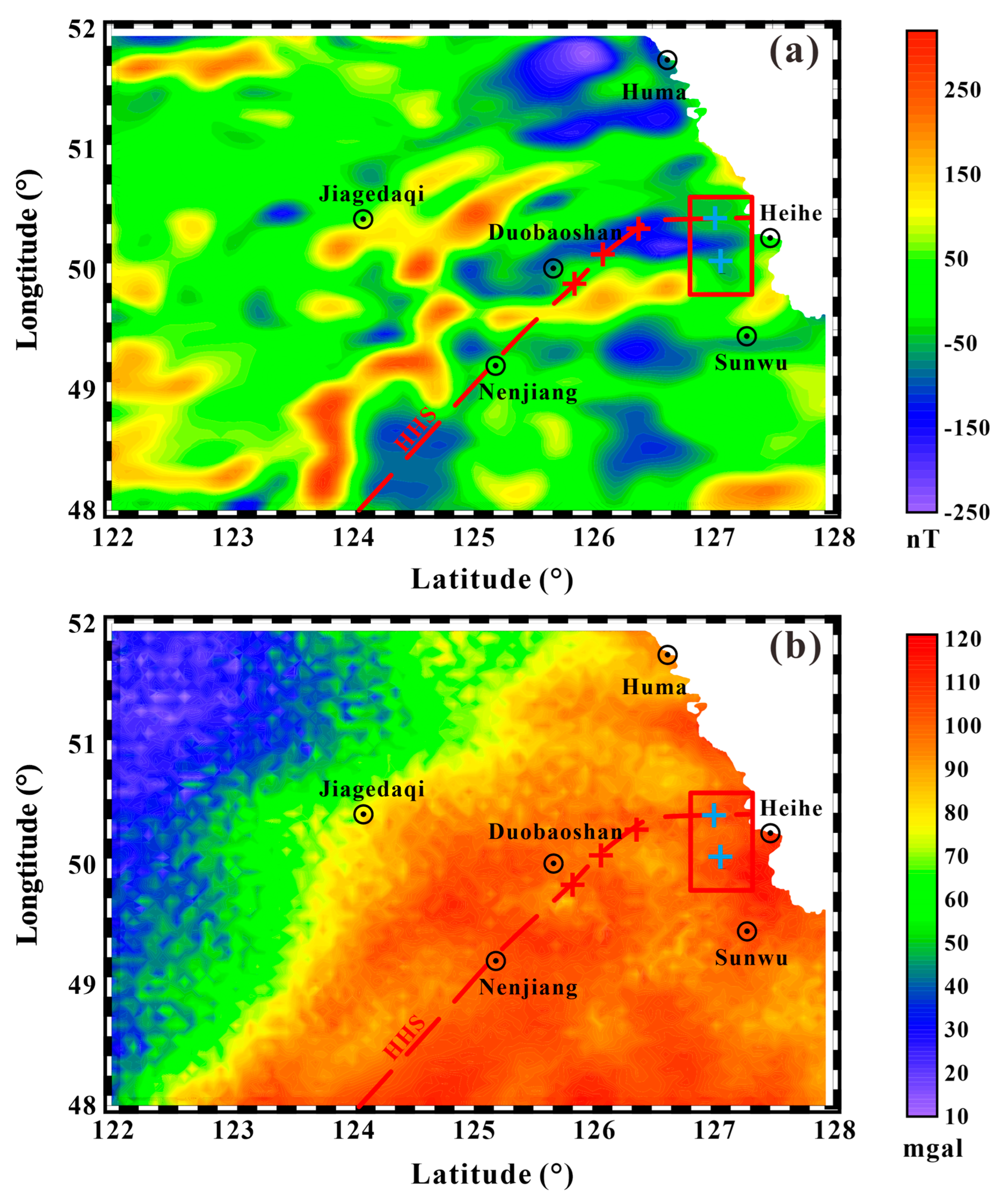

4.1. The Strike Direction and Spatial Extent of the Heihe-Hegenshan Suture in the Heihe Region

4.2. Depth-Dependent Electrical Structure and Its Dominant Controlling Factors of the Suture Zone

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jahn, B.-M.; Wu, F.Y.; Chen, B. Granitoids of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt and continental growth in the Phanerozoic. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 2000, 91, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, B.-M.; Windley, B.; Natal’in, B.; Dobretsov, N. Phanerozoic continental growth in Central Asia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2004, 5, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windley, B.F.; Alexeiev, D.; Xiao, W.J.; Kröner, A.; Badarch, G. Tectonic models for accretion of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Geol. Soc. 2007, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J.; Song, D.F.; Windley, B.F.; Li, J.J.; Han, C.M.; Wan, B.; Zhang, J.E.; Ao, S.J.; Zhang, Z.Y. Accretionary processes and metallogenesis of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Advances and perspectives. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 329–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.B.; Wilde, S.A.; Zhao, G.C.; Han, J. Nature and assembly of microcontinental blocks within the Paleo-Asian Ocean. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 186, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.J.; Guan, Q.B.; Liu, B.R.; Xiao, W.J.; Li, S.Z.; Chen, Z.X.; Peskov, A.Y. Tectonic evolution of the eastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt during the Carboniferous–Permian. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2025, 262, 105046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, W.M.; Feng, Z.Q.; Wen, Q.B.; Neubauer, F.; Liang, C.Y. A review of the Paleozoic tectonics in the eastern part of Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 2017, 43, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, W.M.; Ma, Y.F.; Feng, Z.Q.; Guan, Q.B.; Li, S.Z.; Chen, Z.X.; Liang, C.Y.; Wen, Q.B. An orocline in the eastern central Asian orogenic belt. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 221, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Sun, D.Y.; Ge, W.C.; Zhang, Y.B.; Grant, M.L.; Wilde, S.A.; Jahn, B.-M. Geochronology of the Phanerozoic granitoids in northeastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.Y.; Wu, F.Y.; Li, H.M.; Lin, Q. Emplacement age of the postorogenic A-type granites in Northwestern Lesser Xing’an Ranges, and its relationship to the eastward extension of Suolunshan-Hegenshan-Zhalaite collisional suture zone. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2001, 46, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Z.; Yang, B.J.; Wu, F.Y.; Liu, G.X. The lithosphere structure of Northeast China. Front. Earth Sci. China 2007, 1, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.Z.; Xue, C.J.; Lü, X.B.; Zhao, X.B.; Yang, Y.S.; Li, C.C. Genesis of the Zhengguang gold deposit in the Duobaoshan ore field, Heilongjiang Province, NE China: Constraints from geology, geochronology and S-Pb isotopic compositions. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 84, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.Y.; Wang, K.Y.; Li, J.; Fu, L.J.; Lai, C.K.; Liu, H.L. Geology, geochronology and geochemistry of large Duobaoshan Cu–Mo–Au orefield in NE China: Magma genesis and regional tectonic implications. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 265–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.B.; Li, G.Y.; Wilde, S.A. The nature and spatial–temporal evolution of suture zones in Northeast China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 241, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.X.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.C.; Yuan, H. Electric Structure of Crust and Upper Mantle Along the Xilinhot-Dongwuqi Profile in Inner Mongolia. Chin. J. Geophys. 2011, 54, 580–589. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.H.; Gao, R.; Li, H.Y.; Hou, H.S.; Wu, H.C.; Li, Q.S.; Yang, K.; Li, C.; Li, W.H.; Zhang, J.S.; et al. Crustal structures revealed from a deep seismic reflection profile across the Solonker suture zone of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, northern China: An integrated interpretation. Tectonophysics 2014, 612–613, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.D.; Gao, R.; Hou, H.S.; Liu, G.X.; Han, J.T.; Han, S. Lithospheric electrical structure of the Great Xing’an Range. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 113, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.S.; Wang, H.Y.; Gao, R.; Li, Q.S.; Li, H.Q.; Xiong, X.S.; Li, W.H.; Tong, Y. Fine crustal structure and deformation beneath the Great Xing’an Ranges, CAOB: Revealed by deep seismic reflection profile. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 113, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Hou, H.S.; Gao, R.; Zhou, J.B.; Zhang, X.Z.; Pan, Z.D.; Huang, S.Q.; Guo, R. Lithospheric structures of the northern Hegenshan-Heihe suture: Implications for the Paleozoic metallogenic setting at the eastern segment of the central Asian orogenic belt. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 137, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.W.; Liu, Y.H.; Han, J.T.; Hou, H.S.; Liu, L.J.; Kang, J.Q.; Guo, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.H. Paleozoic suture and Mesozoic tectonic evolution of the lithosphere between the northern section of the Xing’an Block and the Songnen Block: Evidence from three-dimensional magnetotelluric detection. Tectonophysics 2022, 823, 229210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Q.; Ma, G.Q.; Comeau, M.J.; Becken, M.; Zhou, Z.K.; Liu, W.Y.; Kang, J.Q.; Han, J.T. Evidence for the superposition of tectonic systems in the northern Songliao Block, NE China, revealed by a 3-D electrical resistivity model. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB022827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, R.J. Potential Theory in Gravity and Magnetic Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hinze, W.J.; Von Frese, R.; Saad, A.H. Gravity and Magnetic Exploration: Principles, Practices, and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pommier, A. Interpretation of magnetotelluric results using laboratory measurements. Surv. Geophys. 2014, 35, 41–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.D.; Hu, H.Y.; Jiang, J.J.; Sun, W.Q.; Li, H.P.; Wang, M.Q.; Vallianatos, F.; Saltas, V. An overview of the experimental studies on the electrical conductivity of major minerals in the upper mantle and transition zone. Materials 2020, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.D.; Hu, H.Y.; Liu, X.; Manthilake, G.; Saltas, V.; Jiang, J.J. Editorial: High-pressure physical behavior of minerals and rocks: Mineralogy, petrology and geochemistry. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 112646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Gaillard, F.; Villaros, A.; Yang, X.S.; Laumonier, M.; Jolivet, L.; Unsworth, M.; Hashim, L.; Scaillet, B.; Richard, G. Melting conditions in the modern Tibetan crust since the Miocene. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Y.; Dai, L.D.; Li, H.P.; Sun, W.Q.; Li, B.S. Effect of dehydrogenation on the electrical conductivity of Fe-bearing amphibole: Implications for high conductivity anomalies in subduction zones and continental crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018, 498, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Li, W.C.; Ni, H.W. Electrical conductivity of shoshonitic melts with application to magma reservoir beneath the Wudalianchi volcanic field, northeast China. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter 2020, 306, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.Q.; Jiang, J.J.; Dai, L.D.; Hu, H.Y.; Wang, M.Q.; Qi, Y.Q.; Li, H.P. Electrical properties of dry polycrystalline olivine mixed with various chromite contents: Implications for the high conductivity anomalies in subduction zones. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Q.; Dai, L.D.; Hu, H.Y.; Hu, Z.M.; Jing, C.X.; Yin, C.Y.; Luo, S.; Lai, J.H. Electrical conductivity of anhydrous and hydrous gabbroic melt under high temperature and high pressure: Implications for the high conductivity anomalies in the region of mid-ocean ridge. Solid Earth 2023, 14, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Q.; Sun, T.; Hong, M.L.; Hu, Z.M.; Yin, Q.C.; Dai, L.D. The Electrical Properties of Dacite Mixed with Various Pyrite Contents and Its Geophysical Applications for the High-Conductivity Duobaoshan Island Arc. Minerals 2024, 14, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, T.G.; Bibby, H.M.; Brown, C. The magnetotelluric phase tensor. Geophys. J. Int. 2004, 158, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodi, W.; Mackie, R.L. Nonlinear conjugate gradients algorithm for 2D magnetotelluric inversion. Geophysics 2001, 66, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemost, E.A.K. Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.S.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.P.; Dai, L.D.; Hu, H.Y.; Jiang, J.J.; Sun, W.Q. Experimental study on the electrical conductivity of quartz andesite at high temperature and high pressure: Evidence of grain boundary transport. Solid Earth 2015, 6, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.S.; Dai, L.D.; Li, H.P.; Hu, H.Y.; Jiang, J.J.; Sun, W.Q.; Zhang, H. Experimental study on the electrical conductivity of pyroxene andesite at high temperature and high pressure. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2017, 174, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.D.; Hu, H.Y.; Li, H.P.; Jiang, J.J.; Hui, K.S. Influence of temperature, pressure, and chemical composition on the electrical conductivity of granite. Am. Mineral. 2014, 99, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Guo, X.Z.; Wang, X.B.; Zhang, J.F.; Özaydin, S.; Li, D.W.; Clark, S.M. The electrical conductivity of granite: The role of hydrous accessory minerals and the structure water in major minerals. Tectonophysics 2023, 856, 229857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.D.; Gao, R.; Xue, S.; Yang, Z. Lithospheric electrical structure between the Erguna and Xing’an Blocks: Evidence from broadband and long period magnetotelluric data. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2020, 308, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau, M.J.; Becken, M.; Käufl, J.S.; Grayver, A.V.; Kuvshinov, A.V.; Tserendug, S.; Batmagnai, E.; Demberel, S. Evidence for terrane boundaries and suture zones across Southern Mongolia detected with a 2-dimensional magnetotelluric transect. Earth Planets Space 2020, 72, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.W.; Zhou, L.H.; Xiao, D.Q.; Gao, J.R.; Yuan, S.Q.; Tu, G.H.; Zhu, D.Y. The characteristics of crust structure and the gravity and magnetic fields in northeast region of China. Prog. Geophys. 2006, 21, 730–738, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.A.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhou, X.H.; Zhang, L.Q.; Tang, K.D. The relationship between mafic-ultramafic rocks and suture zone in Hegenshan, Inner Mongolia—Evidence from geophysical data. Chin. J. Geophys. 2020, 63, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Jiang, S.H.; Li, S.Z.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W.; Lu, L.L.; Guo, L.L.; Liu, Y.J.; Santosh, M. Paleozoic to Mesozoic micro-block tectonics in the eastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Insights from magnetic and gravity anomalies. Gondwana Res. 2022, 102, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; Cheng, B.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, K.; Cui, X.; Yin, Y.; Li, C. Spatial Analysis of Structure and Metal Mineralization Based on Fractal Theory and Fry Analysis: A Case Study in Nenjiang-Heihe Metallogenic Belt. Minerals 2023, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.Z.; Hu, S.B.; Shi, Y.Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.T.; Hu, D. Terrestrial heat flow of continental China: Updated dataset and tectonic implications. Tectonophysics 2019, 753, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.Z.; Jiang, G.Z.; Shi, S.M.; Wang, Z.C.; Wang, S.J.; Wang, Z.T.; Hu, S.B. Terrestrial heat flow and its geodynamic implications in the northern Songliao Basin, Northeast China. Geophys. J. Int. 2022, 229, 962–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, H.L. Thermal and rheological structure of lithosphere beneath Northeast China. Tectonophysics 2022, 840, 229560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Q.; He, L.J.; Fan, Y.X.; Wu, J.H.; Zhang, H.H.; Guo, L.Y. The contradiction between lithospheric thermal and seismic structures reveals a nonsteady thermal state–A case study from Northeast China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2024, 269, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.W.; Li, S.R.; Li, C.L.; Santosh, M.; Alam, M.; Zeng, Y.J. Geochemical and isotopic composition of auriferous pyrite from the Yongxin gold deposit, Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Implication for ore genesis. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 93, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.Z.; Li, C.L.; Rong, Y.M.; Chen, D.; Zhou, T.; Wang, X.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Lehmann, B.; Yin, R.S. Different metal sources in the evolution of an epithermal ore system: Evidence from mercury isotopes associated with the Erdaokan epithermal Ag-Pb-Zn deposit, NE China. Gondwana Res. 2021, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Hofstra, A.H.; Qin, K.Z.; Xu, H. Formation of bonanza Au-Ag-telluride ores in epithermal systems: Constraints from Cu-O isotopes and modeling. Am. Mineral. 2025, 110, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | HH-05 | HH-11 | HH-14 | HH-07 | HH-12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andesite | Granite | ||||

| SiO2 | 61.45 | 62.24 | 62.64 | 69.50 | 69.67 |

| Al2O3 | 16.98 | 17.38 | 16.39 | 13.49 | 13.56 |

| FeO | 9.06 | 8.93 | 9.41 | 5.54 | 5.24 |

| MgO | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.16 | 0.57 |

| CaO | 2.87 | 2.06 | 2.39 | 1.84 | 1.71 |

| Na2O | 4.20 | 4.43 | 4.34 | 1.92 | 1.80 |

| K2O | 2.17 | 2.33 | 2.22 | 7.03 | 5.99 |

| MnO | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| P2O5 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| TiO2 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.50 |

| LOI | 1.21 | 1.02 | 1.06 | 0.10 | 0.80 |

| Total | 99.71 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.01 | 100.00 |

| A/CNK | 1.84 | 1.97 | 1.83 | 1.25 | 1.43 |

| A/NK | 2.67 | 2.57 | 2.50 | 1.51 | 1.74 |

| Na2O+K2O | 6.37 | 6.77 | 6.56 | 8.94 | 7.79 |

| K/A | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 3.67 | 3.33 |

| Sample | P (GPa) | T (K) | Log [σ0 (S/m)] | ΔH (eV) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andesite | 1 | 573–973 | −0.29 ± 0.12 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 98.56 |

| Granite | 1 | 573–973 | 0.71 ± 0.15 | 0.58 ± 0.02 | 98.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, T.; Wang, M.; Yin, Q.; Wang, K.; Yang, H.; Zhang, T.; Feng, J.; Yuan, H. Multidisciplinary Constraints on the Lithospheric Architecture of the Eastern Heihe-Hegenshan Suture (NE China) from Magnetotelluric Imaging and Laboratory-Based Conductivity Experiment. Minerals 2025, 15, 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111144

Sun T, Wang M, Yin Q, Wang K, Yang H, Zhang T, Feng J, Yuan H. Multidisciplinary Constraints on the Lithospheric Architecture of the Eastern Heihe-Hegenshan Suture (NE China) from Magnetotelluric Imaging and Laboratory-Based Conductivity Experiment. Minerals. 2025; 15(11):1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111144

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Tong, Mengqi Wang, Qichun Yin, Kang Wang, Huaben Yang, Tianen Zhang, Jia Feng, and He Yuan. 2025. "Multidisciplinary Constraints on the Lithospheric Architecture of the Eastern Heihe-Hegenshan Suture (NE China) from Magnetotelluric Imaging and Laboratory-Based Conductivity Experiment" Minerals 15, no. 11: 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111144

APA StyleSun, T., Wang, M., Yin, Q., Wang, K., Yang, H., Zhang, T., Feng, J., & Yuan, H. (2025). Multidisciplinary Constraints on the Lithospheric Architecture of the Eastern Heihe-Hegenshan Suture (NE China) from Magnetotelluric Imaging and Laboratory-Based Conductivity Experiment. Minerals, 15(11), 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111144