Lime and Cement Plasters from 20th Century Buildings: Raw Materials and Relations between Mineralogical–Petrographic Characteristics and Chemical–Physical Compatibility with the Limestone Substrate

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. State of Art and Aims of Research

1.2. Location of Site in the Historical Context of Cagliari

2. Limestone Rocks Outcropping in the Site

2.1. Geological Setting

2.2. Use and Decay of Limestone Rocks in Historical Period

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Compositional Characterisation of Mortars

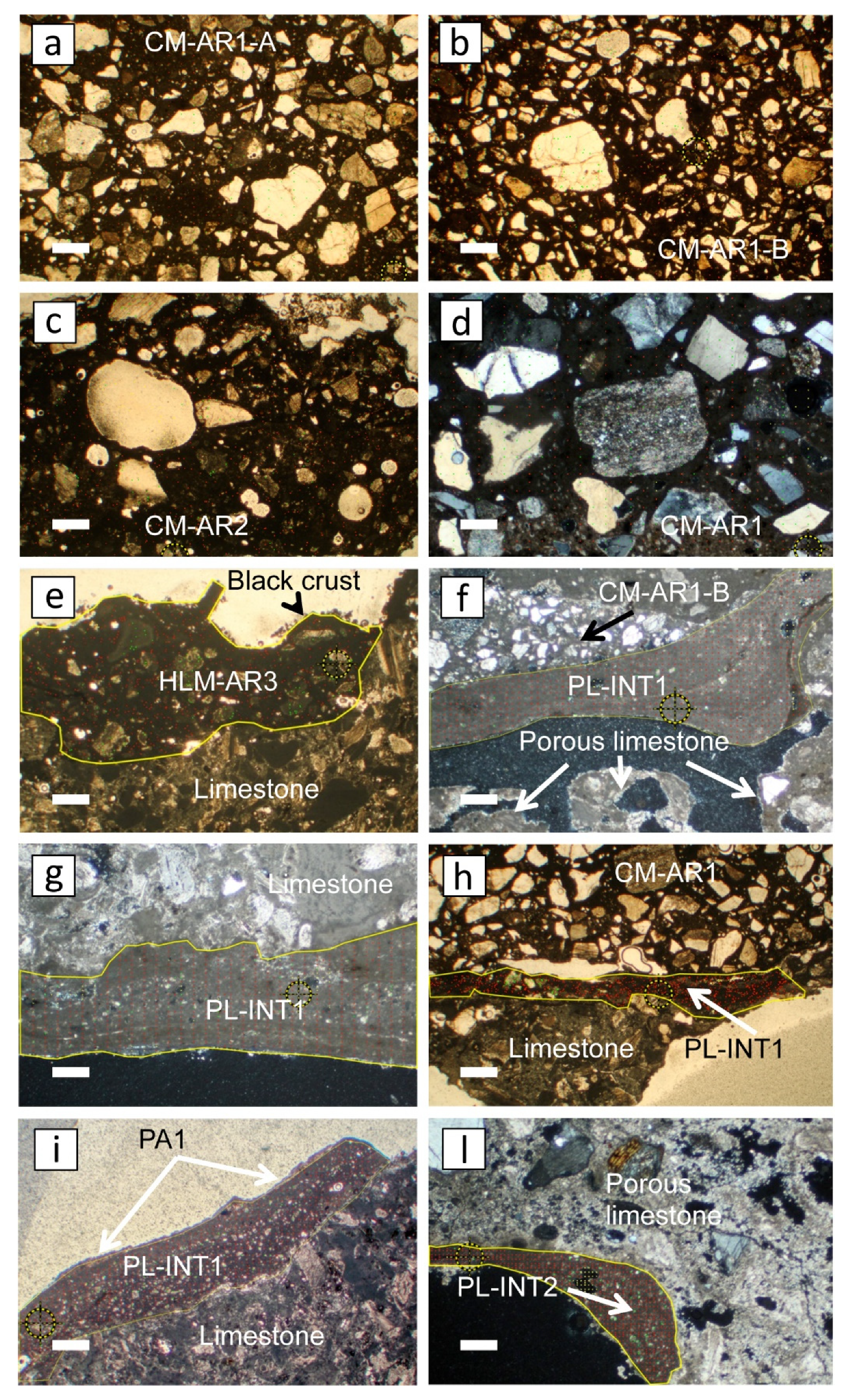

4.1.1. Classification of Samples

- (1)

- Cement mortars (signed as CM) are present unevenly in the cave inner wall, and sometimes are also used for the installation of hydraulic or lighting systems, or to fill wall voids and/or to consolidate fractures and discontinuities (Figure 5b,c,g). They are characterised by a typical greyish to brown-grey cement-based binder (thus with high hydraulic degree) and a silicate aggregate (mainly quartz and feldspars). During the sample collection they appeared quite hard, suggesting heavy mechanical strength. Two types have been distinguished from the binder/aggregate ratio (B/A) measured by image analyses: CM-AR1, with an average B/A of about 56:42%, and CM-AR2, with a B/A of 67:20%.

- (2)

- Hydraulic lime mortars (signed as HLM), consisting of fine-grained quartz and feldspar aggregates (Figure 5b,e–g) and a whitish hydraulic lime binder, according to the EN 459-1:2015 standard [80] can be classified as HL mortars. Mechanical strength and hydraulic grade appear to be lower than those of cement mortars. All HLM samples look quite similar in grain-size, colour, and B/A but strongly differ in thickness; this parameter has been chosen to distinguish the three categories, and to evaluate if different HLMs were employed to achieve different thicknesses.

- (3)

- Finishing plasters (intonachino, signed as PL) consist of fine aggregate and a lime (or feebly hydraulic)-based binder with very low mechanical strength (Figure 5a,d,h). According to the EN 459-1:2015 standard [80], the PL samples can be classified as air lime plasters. PL samples have been subdivided into three types depending on their macroscopic aspect, on the adhesion to the substrate and on their “stratigraphic” position.

- -

- arriccio layers (AR) are the plasters with coarse-grained aggregate (mainly ranging in 1–2 mm) used to fill voids and fractures, to flatten the rock substrate, and to create a rough surface that allows the grip of the finishing plaster. They are commonly 7 to 12 mm thick but can reach 25–30 mm when used as filler for voids. The AR binder layers can be either cement or hydraulic lime and they were found to be applied directly on the rocky substrate or above older plasters.

- -

- intonachino layers (INT) are the finishing plaster characterised by finer aggregates (<0.5 mm) and a low thickness (2–4 mm). They usually adhere to the AR layer, although one sampling point was found to lie directly on the rock substrate. All INT layers have a lime-based binder and a little amount of fine aggregates.

4.1.2. Stratigraphy of Plasters and Decay

4.1.3. Petrographic Characteristics

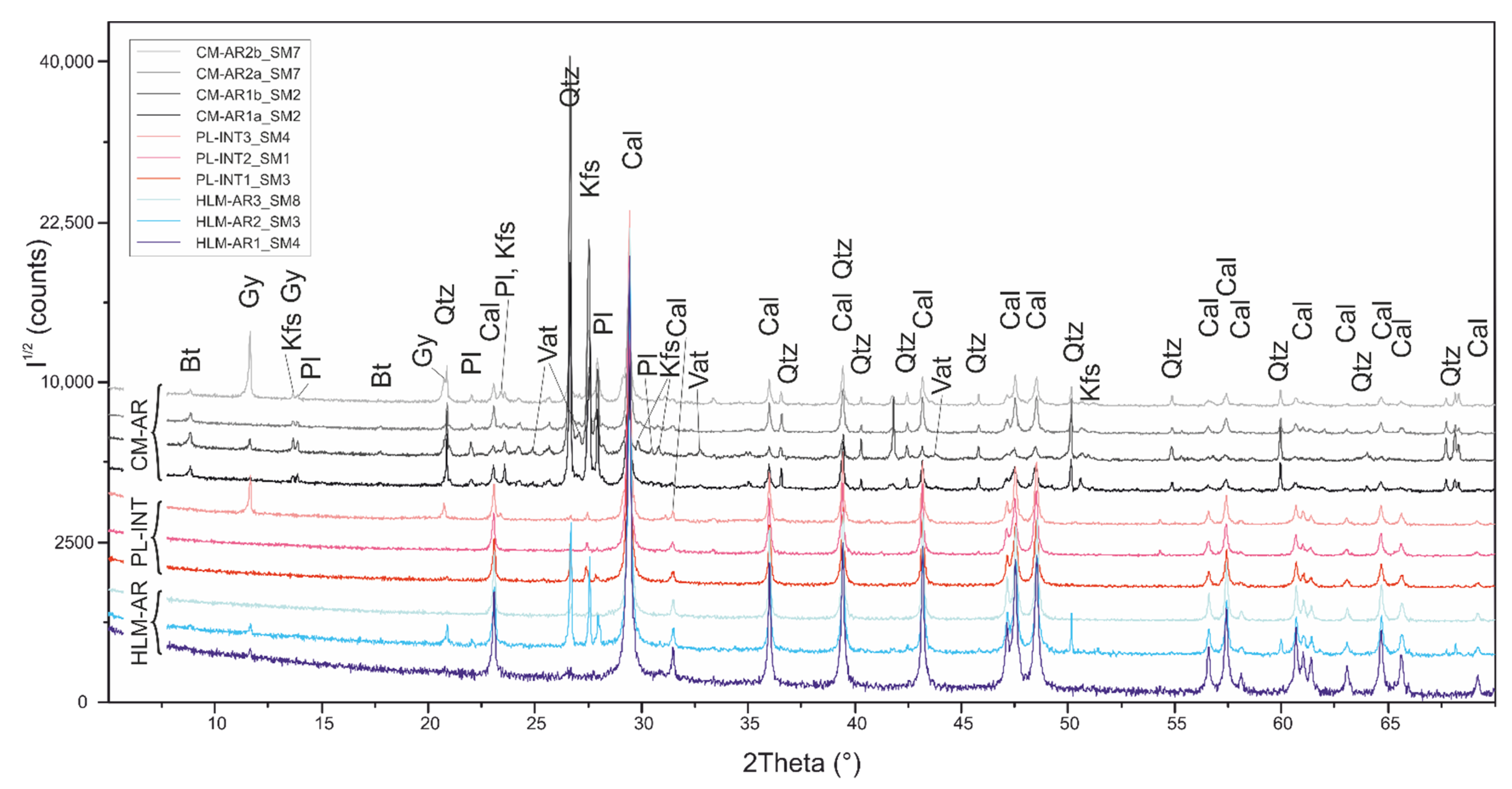

4.1.4. X-ray Diffraction

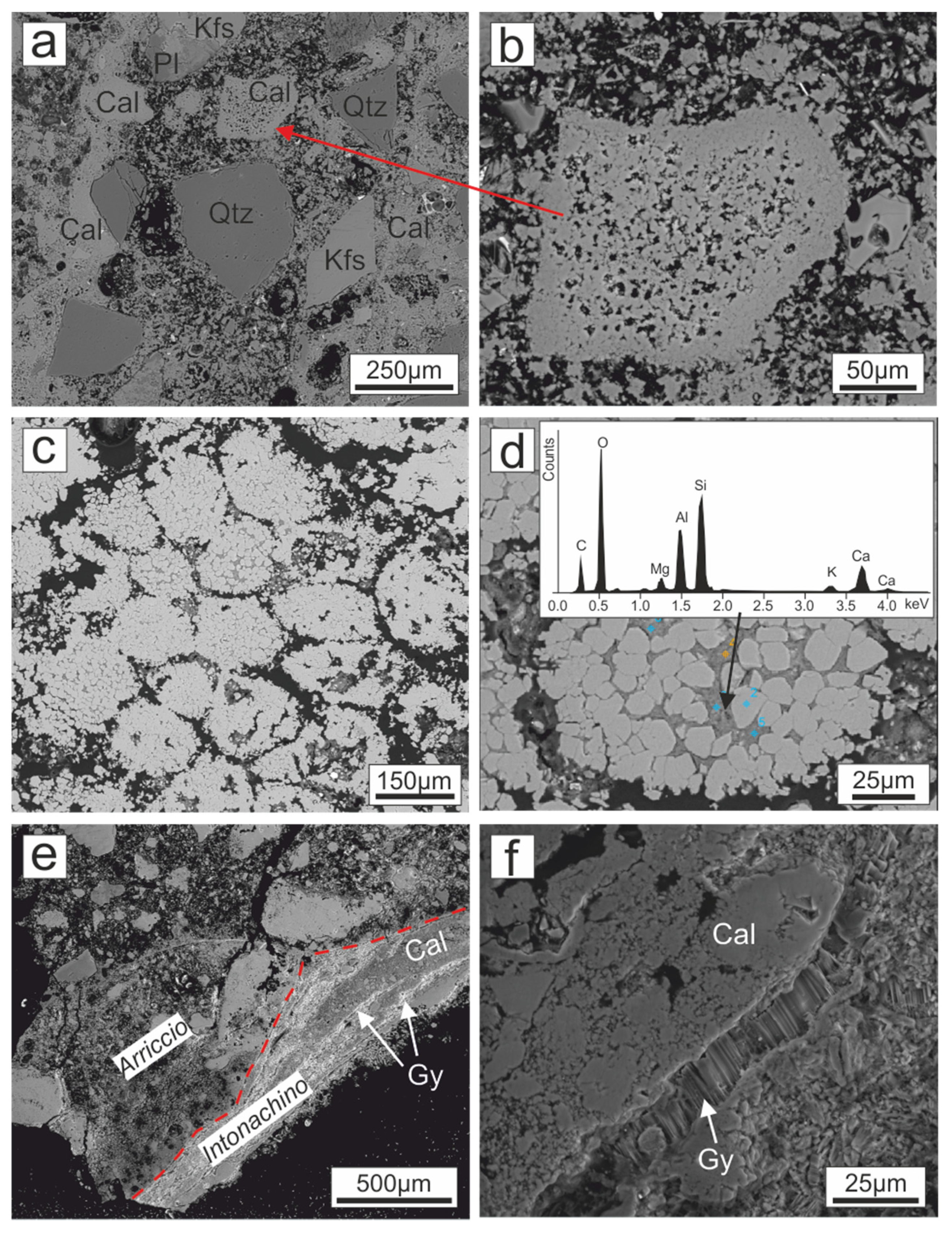

4.1.5. SEM Imaging and EDS Analyses

- (i)

- anhedral to subhedral grains (commonly micrometre-sized but locally reaching 100 μm; Figure 11a,b) of Si-rich Al-silicates (SiO2 ~ 66 wt.%, Al2O3 ~ 13 wt.%, K2O ~ 5 wt.% with 2–3 wt.% of both CaO and Na2O) resembling the composition of a zeolite, specifically a K-rich mordenite;

- (ii)

- C-S-H fibrous aggregates of hydrated Ca-rich calcium silicates, attributable to the hydrated alite (according to Cement Chemist Notation acronym: C3S = 3CaO•SiO2) and belite (C2S = 2CaO•SiO2, with CaO = 58–59 wt.% and SiO2 = 32–34 wt.%) phases typical of cement, with minor amounts of Al, Na, Mg, and K oxides (Figure 11b);

- (iii)

- anhedral subrounded grains of hydrated Si-rich calcium silicates (CaO = 33–35 wt.% and SiO2 = 32–34 wt.% = CaO•SiO2), with subordinate amounts of Al, Mg, and Fe oxides (Figure 11c);

- (iv)

- mixed phases of C-A-H and C-S-H (as hydrated mono-calcium aluminate and type iii phase) and of C4AF phases (with formation of aluminates (C-A-H) and ferrites (C-F-H) hydrates), overall, mainly consisting of CaO = 43–44 wt.%, Al2O3 = 18–20 wt.%, Fe2O3 = 17–18 wt.%, and SiO2 = 10–14% (Figure 11c);

- (v)

- subrounded aggregates of fibrous crystals (Figure 11d) made up by CaO ~ 34 wt.%, SO3 ~ 22 wt.%, SiO2 ~ 11 wt.%, and Al2O3 ~ 6 wt.% that approximate the composition of a ettringite–thaumasite-like phase, derived by a reaction between the Ca-alluminates and the gypsum used to delay the setting of the cement;

- (vi)

- (vii)

- rare anhedral calcite grains randomly distributed within the binder, derived by the carbonatation of residual Ca(OH)2, produced by the hydration reaction of alite (C3S) and belite (C2S) phases.

4.1.6. Binder/Aggregate Ratio of Mortars

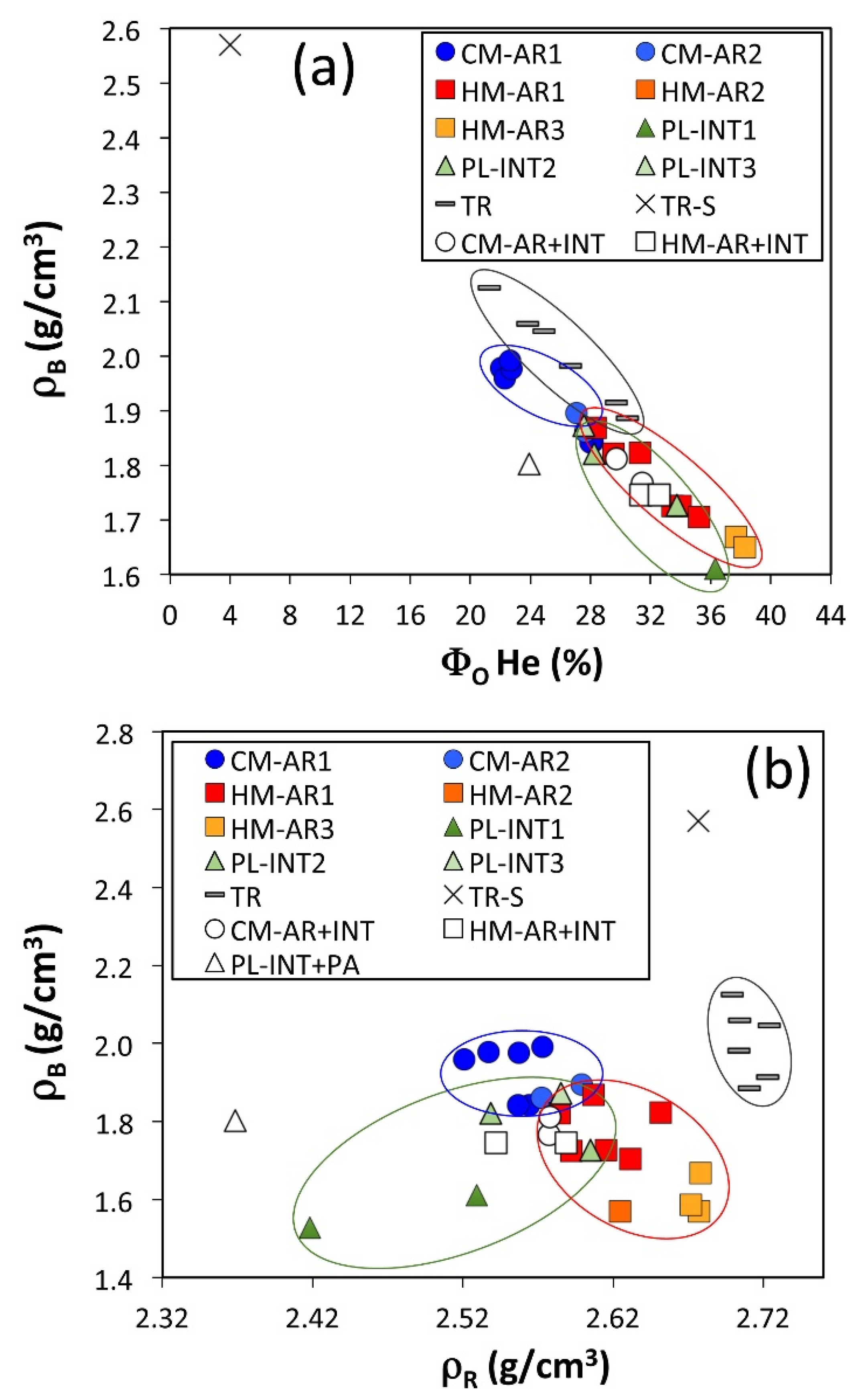

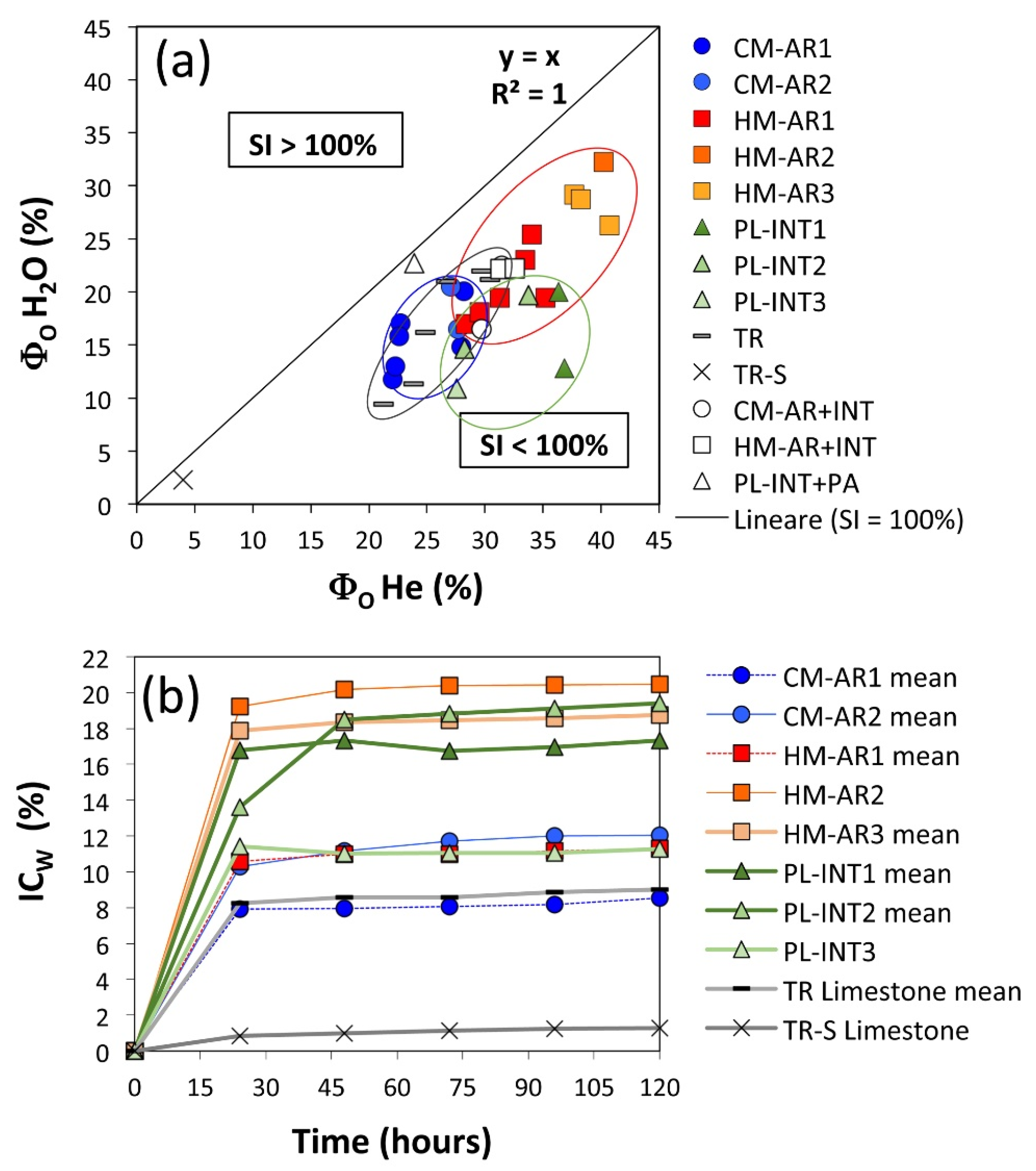

4.2. Physical Properties

4.2.1. Plaster Samples

- (1)

- (2)

- calcium aluminate hydrate C-A-H as C3AH6 and C4AH13, with density 2.04 g/cm3 whose formation implies the presence of portlandite C-H, having a density of 2.26 g/cm3 [84].

4.2.2. Limestone Samples

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- two layers of cement mortars (CM-AR1, CM-AR2), usually adhered to the limestone substrate, with a cement binder composed mainly of C-S-H, C-A-H, and C-F-H phases, and a subordinate amount of calcite derived from the carbonation of Ca hydroxide, resulting from the hydration of the anhydrous alite and belite phases. Such mortars are generally fat, as they show a greater binder/aggregate (about 3/2) ratio than the standard mix. The aggregate mainly consists of quartz, K-feldspar, plagioclase, biotite, lithoclasts and a subordinate amount of marine Ca-carbonate fossil remains, indicating a probable supply from the sands of local Cagliari beaches. Given their high hydraulic degree and physical properties, characterised by low water open porosity (on average from 15.4 to 18.5%) and a high stiffness in mechanical behaviour, the cement mortars were often found detached from the substrate or leading to the detachment of the overlying layers, although at times demonstrating good adhesion to the limestone from a chemical point of view; moreover, they are frequently loaded with salt efflorescence, especially of intrinsic derivation, not only from the rock water circulating solutions. The laying of these cement layers can be ascribed to the first restoration interventions in the Grotta Marcello room, probably during or immediately after the Second World War, which locally affected the walls of the cave (perhaps to cover the traces of the electrical installations of the internal lighting).

- (2)

- mortars based on hydraulic lime (HLM-AR), characterised by a binder substantially composed of C-S-H, C-A-H phases, and, to a greater extent than cement mortars, calcite, derived from the carbonation of portlandite (Ca(OH)2) that is normally present in lime and only to a much lesser extent due to the belite hydration. The aggregate is mainly silicatic and it is similar to those of CM mortars, although with a more variable mineralogy that also includes subordinate amounts of sedimentary rocks. These mortars showed a good adhesion to PL-INT plaster layers, as well as to the limestone substrate, demonstrating excellent adaptability on a physical-mechanical and chemical point of view. Moreover, due to a greater He-gas open porosity (on average from 32 to 38.9%), HLM mortars show a good breathability. Their use is attributable to more recent periods (especially HLM-AR2 and HLM-AR3 layers). This is due to the need to level out some of the gaps created in the internal walls over time as a result of degradation, trying to maintain chromatic characteristics similar to those of the underlying stone as far as possible. In fact, it must be remembered that Grotta Marcello is a state property and under the control of the Superintendency, and for these reasons must respond as much as possible to respect the original locations.

- (3)

- finishing plasters (intonachino, PL-INT) consist of air lime-based binder with high incidence (86–88 vol.%) and a very fine aggregate (generally <1 mm) with a mainly carbonatic composition and rare presence of quartz crystals. It is possible to refer their laying to a more or less long-time span (about 60 years). The first layer (PL-INT1, light beige in colour) was almost always laid directly on the rocky substrate of the local limestone (Tramezzario) and locally also on the cement mortars (CM). The PL-INT layers can be traced back to the first treatment of the walls immediately after the Second World War (1950s). The subsequent PL-INT2 and INT3 layers, also based on lime, have similar compositional characteristics to PL-INT1. The intonachino PL-INT2 is often inhomogeneous in composition, and showed alternating calcite and calcite/gypsum levels. The contact between PL-INT2 and HLM-AR/CM-AR is locally marked by micrometre-sized fractures filled by fibrous gypsum crystals, growing perpendicular to the interface. The intonachino layers were laid in the following decades; they were probably used in part to sanitise (for the same reasons mentioned above), and in part to cover up, missing parts of the previous layers.

- (4)

- lime paints (beige and light blue coloured), overlapping the other plasters and consisting of one/two layers, were probably used as “quicklime” to be slaked on site (CaO + H2O), to eliminate (given the exothermic reaction that produces the slaking, up to 80–90 °C) the moulds created in the large wet areas due to the persistence of moisture in the rock-walls of the cave-room, by virtue of their medium–high porosity (from 27.6 to 36.6%). Due to the low amount of aggregate and the thin thickness that gives an elastic physical–mechanical behaviour, the paints showed a good adaptability to the irregular surface of the cave-room walls. However, sometimes there are some evident detachments from the wall substrate.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elsen, J. Microscopy of historic mortars—A review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carran, D.; Hughes, J.; Leslie, A.; Kennedy, C. The Effect of Calcination Time upon the Slaking Properties of Quicklime. In Historic Mortars; RILEM Bookseries; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 7, pp. 283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, A. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000-586 BCE; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Elert, K.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C.; Sebastian Pardo, E.; Hansen, E.; Cazalla, O. Lime Mortars for the Conservation of Historic Buildings. Stud. Conserv. 2002, 47, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, R.; Cau Ontiveros, M.A.; Miriello, D.; Pecci, A.; Le Pera, E.; Bloise, A.; Crisci, G.M. Archaeometric study of mortars and plasters from the Roman City of Pollentia (Mallorca-Balearic Islands). Period. Mineral. 2013, 82, 353–379. [Google Scholar]

- Columbu, S. Petrographic and geochemical investigations on the volcanic rocks used in the Punic-Roman archaeological site of Nora (Sardinia, Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramacciotti, M.; Rubio, S.; Gallello, G.; Lezzerini, M.; Columbu, S.; Hernandez, E.; Morales-Rubio, A.; Pastor, A.; De La Guardia, M. Chronological classification of ancient mortars employing spectroscopy and spectrometry techniques: Sagunto (Valencia, Spain) Case. J. Spectrosc. 2018, 2018, 9736547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Columbu, S.; Verdiani, G. Digital Survey and Material Analysis Strategies for Documenting, Monitoring and Study the Romanesque Churches in Sardinia, Italy. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation and Protection, 5th International Conference, EuroMed 2014, Limasol, Cyprus, 3–8 November 2014; Magnenat-Thalmann, I., Zarnic, F., Quac, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 446–453. ISSN 03029743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aquino, A.; Pagnotta, S.; Pecchioni, E.; Cecchi, V.M.; Columbu, S.; Lezzerini, M. The role of 3D modelling for different stone objects: From mineral to artefact. In Proceedings of the 2020 IMEKO TC-4 International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Trento, Italy, 22–24 October 2020; pp. 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Columbu, S.; Sitzia, F.; Verdiani, G. Contribution of petrophysical analysis and 3D digital survey in the archaeometric investigations of the Emperor Hadrian’s Baths (Tivoli, Italy). Rend. Lincei 2015, 26, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattuso, C.; Gazineo, F.; La Russa, F. Characterisation of archaeological mortars from Pompeii (Campania, Italy) and identification of construction phases by compositional data analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 2207–2223. [Google Scholar]

- Miriello, D.; Antonelli, F.; Apollaro, C.; Bloise, A.; Bruno, N.; Catalano, M.; Columbu, S.; Crisci, G.M.; De Luca, R.; Lezzerini, M.; et al. A petro-chemical study of ancient mortars from the archaeological site of Kyme (Turkey). Period. Mineral. 2015, 84, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vola, G.; Gotti, E.; Brandon, C.; Oleson, J.P.; Hohlfelder, R.L. Chemical, mineralogical and petrographic characterization of roman ancient hydraulic concretes cores from Santa Liberata, Italy, and Caesarea Palestinae, Israel. Period. Mineral. 2011, 80, 317–338. [Google Scholar]

- Miriello, D.; Antonelli, F.; Bloise, A.; Ceci, M.; Columbu, S.; De Luca, R.; Lezzerini, M.; Pecci, A.; Mollo, B.S.; Brocato, P. Archaeometric approach for studying architectural earthenwares from the archaeological site of St. Omobono (Rome-Italy). Minerals 2019, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Columbu, S.; Gaviano, E.; Costamagna, L.G.; Fancello, D. Mineralogical-petrographic and physical-mechanical features of the construction stones in Punic and Roman temples of Antas (SW Sardinia, Italy): Provenance of the raw materials and conservation state. Minerals 2021, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Columbu, S.; De Vos Raaijmakers, M.; Andreoli, M. An archaeometric contribution to the study of ancient millstones from the Mulargia area (Sardinia, Italy) through new analytical data on volcanic raw material and archaeological items from Hellenistic and Roman North Africa. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 50, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S. Provenance and alteration of pyroclastic rocks from the Romanesque Churches of Logudoro (north Sardinia, Italy) using a petrographic and geochemical statistical approach. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2017, 123, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, C.; De Bonis, A.; Guarino, V.; Graziano, S.F.; Di Benedetto, C.; Esposito, R.; Morra, V.; Cappelletti, P. The ancient pozzolanic mortars of the Thermal Complex of Baia (Campi Flegrei, Italy). J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 40, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Sitzia, F.; Ennas, G. The ancient pozzolanic mortars and concretes of Heliocaminus baths in Hadrian’s Villa (Tivoli, Italy). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2017, 9, 523–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, C.; De Bonis, A.; Esposito, R.; Graziano, S.F.; Langella, A.; Mercurio, M.; Morra, V.; Cappelletti, P. Unveiling the secrets of roman craftsmanship: Mortars from Piscina Mirabilis (Campi Flegrei, Italy). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Antonelli, F.; Lezzerini, M.; Miriello, D.; Adembri, B.; Blanco, A. Provenance of marbles used in the Heliocaminus Baths of Hadrian’s Villa (Tivoli, Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 49, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramacciotti, M.; Rubio, S.; Gallello, G.; Lezzerini, M.; Raneri, S.; Hernandez, E.; Calvo, M.; Columbu, S.; Morales, A.; Pastor, A.; et al. Chemical and mineralogical analyses on stones from Sagunto Castle (Spain). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2019, 24, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Columbu, S.; Gioncada, A.; Lezzerini, M.; Marchi, M. Hydric dilatation of ignimbritic stones used in the Church of Santa Maria di Otti (Oschiri, northern Sardinia, Italy). Ital. J. Geosci. 2014, 133, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Columbu, S.; Lezzerini, M.; Miriello, D. Petrographic characterisation and provenance determination of the white marbles used in the roman sculptures of Forum Sempronii (Fossombrone, Marche, Italy). Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2014, 115, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Garau, A.M. Mineralogical, petrographic and chemical analysis of geomaterials used in the mortars of Roman Nora theatre (south Sardinia, Italy). Ital. J. Geosci. 2017, 136, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raneri, S.; Pagnotta, S.; Lezzerini, M.; Legnaioli, S.; Palleschi, V.; Columbu, S.; Neri, N.F.; Mazzoleni, P. Examining the reactivity of volcanic ash in ancient mortars by using a micro-chemical approach. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. Int. Sci. J. 2018, 18, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Lisci, C.; Sitzia, F.; Lorenzetti, G.; Lezzerini, M.; Pagnotta, S.; Raneri, S.; Legnaioli, S.; Palleschi, V.; Gallello, G.; et al. Mineralogical, petrographic and physical-mechanical study of Roman construction materials from the Maritime Theatre of Hadrian’s Villa (Rome, Italy). Measurement 2018, 127, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Palomba, M.; Sitzia, F.; Carcangiu, G.; Meloni, P. Pyroclastic Stones as Building Materials in Medieval Romanesque Architecture of Sardinia (Italy): Chemical-Physical Features of Rocks and Associated Alterations. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2020, 16, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Lezzerini, M.; Verdiani, G. Geochemical and petrographic analysis on the stones and integrated digital survey of the Cathedral of Sant’Antioco di Bisarcio (Ozieri, Italy). In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Cassino, Italy, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki, P.; Bakolas, A.; Moropoulou, A. Physico-chemical study of Cretan ancient mortars. Cem. Concr. 2003, 33, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Giamello, M.; Pagnotta, S.; Aquino, A.; Lezzerini, M. Ca-oxalate films on the stones of the medieval architecture: The case-study of Romanesque Churches. In Proceedings of the 2020 IMEKO TC-4 International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Trento, Italy, 22–24 October 2020; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrame, M.; Sitzia, F.; Liberato, M.; Columbu, S.; Mirão, J. Comparative pottery technology between the Middle Ages and Modern times (Santarém, Portugal). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Palomba, M.; Sitzia, F.; Murgia, M.R. Geochemical, mineral-petrographic and physical-mechanical characterisation of stones and mortars from the Romanesque Saccargia Basilica (Sardinia, Italy) to define their origin and alteration. Ital. J. Geosci. 2018, 137, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezzerini, M.; Raneri, S.; Pagnotta, S.; Columbu, S.; Gallello, G. Archaeometric study of mortars from the Pisa’s Cathedral Square (Italy). Measurement 2018, 126, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Columbu, S.; Meloni, P.; Carcangiu, G.; Fancello, D. Workability and chemical-physical degradation of limestone frequently used in historical Mediterranean architecture. In Proceedings of the 2020 IMEKO TC-4 International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Trento, Italy, 22–24 October 2020; pp. 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Sitzia, F.; Beltrame, M.; Columbu, S.; Lisci, C.; Miguel, C.; Mirão, J. Ancient restoration and production technologies of Roman mortars from monuments placed in hydrogeological risk areas: A case study. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Columbu, S.; Gioncada, A.; Lezzerini, M.; Sitzia, F. Mineralogical-chemical alteration and origin of ignimbritic stones used in the old Cathedral of Nostra Signora di Castro (Sardinia, Italy). Stud. Conserv. 2019, 64, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Garau, A.M.; Lugliè, C. Geochemical characterisation of pozzolanic obsidian glasses used in the ancient mortars of Nora Roman theatre (Sardinia, Italy): Provenance of raw materials and historical–archaeological implications. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 2121–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Lisci, C.; Sitzia, F.; Buccellato, G. Physical-mechanical consolidation and protection of Miocenic limestone used on Mediterranean historical monuments: The case study of Pietra Cantone (Southern Sardinia, Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezzerini, M.; Antonelli, F.; Columbu, S.; Gadducci, R.; Marradi, A.; Miriello, D.; Parodi, L.; Secchiari, L.; Lazzeri, A. Cultural heritage documentation and conservation: Three-dimensional (3D) laser scanning and geographical information system (GIS) techniques for thematic mapping of facade stonework of St. Nicholas Church (Pisa, Italy). Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2016, 10, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschelli, M.; Columbu, S.; Elter, F.M.; Cruciani, G. Giant Garnet Crystals in Wollastonite–Grossularite–Diopside-Bearing Marbles from Tamarispa (NE Sardinia, Italy): Geosite Potential, Conservation, and Evaluation as Part of a Regional Environmental Resource. Geoheritage 2021, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Piras, G.; Sitzia, F.; Pagnotta, S.; Raneri, S.; Legnaioli, S.; Palleschi, V.; Lezzerini, M.; Giamello, M. Petrographic and mineralogical charecterization of volcanic rocks and surface-depositions on Romanesque monuments. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2018, 18, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buosi, C.; Columbu, S.; Ennas, G.; Pittau, P.; Scanu, G.G. Mineralogical, petrographic, and physical investigations on fossiliferous middle Jurassic sandstones from central Sardinia (Italy) to define their alteration and experimental consolidation. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 729–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Carboni, S.; Pagnotta, S.; Lezzerini, M.; Raneri, S.; Legnaioli, S.; Palleschi, V.; Usai, A. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy analysis of the limestone Nuragic statues from Monte Prama site (Sardinia, Italy). Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2018, 149, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragoni, M.C.; Giacopetti, L.; Arca, M.; Carcangiu, G.; Columbu, S.; Gimeno, D.; Isaia, F.; Lippolis, V.; Meloni, P.; Ezquerra, A.N.; et al. Ammonium monoethyloxalate (AmEtOx): A new agent for the conservation of carbonate stone substrates. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 5327–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, A.M.; Szadurski, E.M.; Banfill, P.F.G. Deterioration of natural hydraulic lime mortars, I: Effects of chemically accelerated leaching on physical and mechanical properties of uncarbonated materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 72, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banfill, P.F.G.; Szadurski, E.M.; Forster, A.M. Deterioration of natural hydraulic lime mortars, II: Effects of chemically accelerated leaching on physical and mechanical properties of carbonated materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Apostolopoulou, M.; Bakolas, A.; Kotsainas, M. Mechanical and physical performance of natural hydraulic lime mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 290, 123272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanas, J.; Bernal, J.L.P.; Bello, M.A.; Alvarez Galindo, J.I. Mechanical properties of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Figueiredo, C.; Lawrence, M.; Ball, R.J. Mechanical properties of standard and commonly formulated NHL mortars used for retrofitting. In Proceedings of the Integrated Design Conference, Bath, UK, 29 June 2016; Emmitt, S., Adeyeye, K., Eds.; University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, B.A.; Pinto, A.P.F.; Gomes, A. Influence of natural hydraulic lime content on the properties of aerial lime-based mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 72, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Xu, C.; Zhai, M.; Ma, X. Comparative study on the properties of three hydraulic lime mortar systems: Natural hydraulic lime mortar, cement-aerial lime-based mortar and slag-aerial lime-based mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, M.; Armaghani, D.J.; Bakolas, A.; Douvika, M.G.; Moropoulou, A.; Asteris, P.G. Compressive strength of natural hydraulic lime mortars using soft computing techniques. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 17, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X. Influence of pozzolanic materials on the properties of natural hydraulic lime based mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 244, 118360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S. Evolution of mechanical properties and drying shrinkage in lime-based and lime cement-based mortars with pure limestone aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 77, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, R.; Pinto, A.P.F.; Gomes, A. Design and behavior of traditional limebased plasters and renders. Review and critical appraisal of strengths and weaknesses. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 89, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardabasso, S.; Atzeni, A. Il bacino Oligocenico di Oschiri-Berchidda nella Sardegna nord-occidentale. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1962, 3, 717. [Google Scholar]

- Cherchi, A.; Montadert, L. Oligo-Miocene rift of Sardinia and the early history of the western Mediterranean basin. Nature 1982, 298, 736–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherchi, A.; Mancin, N.; Montadert, L.; Murru, M.; Putzu, M.T.; Schiavinotto, F.; Verrubbi, V. The stratigraphic response to the Oligo-Miocene extension in the western Mediterranean from observations on the Sardinia graben system (Italy). Bull. Soc. Geol. Fr. 2008, 179, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccenna, C.; Speranza, F.; D’Ajello Caracciolo, F.; Mattei, M.; Oggiano, G. Extensional tectonics on Sardinia (Italy): Insights into the arc–back-arc transitional regime. Tectonophysics 2002, 356, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Oggiano, G.; Cocherie, A. A restored section of the “southern Variscan realm” across the Corsica–Sardinia microcontinent. C. R. Geosci. 2009, 341, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casula, G.; Cherchi, A.; Montadert, L.; Murru, M.; Sarria, E. The Cenozoic graben system of Sardinia (Italy): Geodynamic evolution from new seismic and field data. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2001, 18, 863–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funedda, A.; Oggiano, G.; Pasci, S. The Logudoro Basin; a key area for the Tertiary tectono-sedimentary evolution of north Sardinia. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2000, 119, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Carmignani, L.; Oggiano, G.; Funedda, A.; Conti, P.; Pasci, S. The geological map of Sardinia (Italy) at 1: 250,000 scale. J. Maps 2016, 12, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrocu, G. Urban geology and hydrogeology of the Metropolitan Area of Cagliari. In Il Caso di Studio dell’Area Metropolitana di Cagliari: Pianificazione Sostenibile: Paesaggio, Ambiente, Energia. Future Mac 09; Abis, E., Ed.; Gangemi Editore S.p.A.: Roma, Italy, 2010; pp. 116–121. ISBN 9788849219449. [Google Scholar]

- Barrocu, G.; Crespellani, T.; Loi, A. Caratteristiche geologico-techiche del sottosuolo dell’area urbana di Cagliari. Riv. Ital. Geotec. 1981, 15, 98–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cherchi, A. Appunti biostratigrafici sul Miocene della Sardegna (Italia). Mém. BRGM 1974, 78, 433–445. [Google Scholar]

- Cherchi, A.; Montadert, L. Il sistema di rifting oligo-miocenico del Mediterraneo occidentale e sue conseguenze paleogeografiche sul terziario sardo. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1982, 24, 387–400. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi, R.; Porcu, A. Contributo alla conoscenza delle microfacies mioceniche delle colline di Cagliari (Sardegna). Riv. Ital. Paleontol. Stratigr. 1967, 73, 313–348. [Google Scholar]

- Pecorini, G.; Cherchi, A.P. Ricerche geologiche e biostratigrafiche sul Campidano meridionale (Sardegna). Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1969, 8, 421–451. [Google Scholar]

- RAS. Regione Autonoma della Sardegna, Carta Geologica di Base della Sardegna in Scala 1:25,000. 2010. Available online: https://www.sardegnageoportale.it/index.php?xsl=2420&s=40&v=9&c=14479&es=6603&na=1&n=100&esp=1&tb=14401 (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Carmignani, L.; Oggiano, G.; Barca, S.; Conti, P.; Salvadori, I.; Eltrudis, A.; Funedda, A.; Pasci, S. Geologia della Sardegna. Note Illustrative della Carta Geologica in Scala 1:200,000. Mem. Descr. Carta Geol. It., LX.; Servizio Geologico d’Italia: Roma, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, F.; Pontillo, C.; Spano, C.; Carmignani, L.; Sassi, F.P. Benthic paleocommunities of the middle–upper Miocene lithostratigraphic units from the Cagliari hills (Southern Sardinia, Italy). Contrib. Geol. Italy Spec. Regard Paleoz. Basement IGCP Proj. 1992, 276, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bertorino, G.; Franceschelli, M.; Marchi, M.; Lugliè, C.; Columbu, S. Petrographic characterisation of polished stone axes from Neolithic Sardinia: Archaeological implications. Period. Miner. 2002, 71, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Columbu, S.; Antonelli, F.; Sitzia, F. Origin of Roman worked stones from St. Saturno Christian Basilica (South Sardinia, Italy). Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2018, 18, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovisato, D. Le Calcaire grossier jaunâtre de Pirri del Lamarmora e i Calcari di Cagliari come Pietra di Costruzione; Tipo-Litografia Commerciale: Cagliari, Italy, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations Nor.Ma.L. 3/80 Stone Materials: Sampling; Reprint 1988; CNR-ICR: Roma, Italy, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Columbu, S.; Mulas, M.; Mundula, F.; Cioni, R. Strategies for helium pycnometry density measurements of welded ignimbritic rocks. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2021, 173, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Cruciani, G.; Fancello, D.; Franceschelli, M.; Musumeci, G. Petrophysical properties of a granite-protomylonite-ultramylonite sequence: Insight from the Monte Grighini shear zone, central Sardinia, Italy. Eur. J. Mineral. 2014, 27, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 459-1:2015; Building Lime—Part 1: Definitions, Specifications and Conformity Criteria. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/588081bb-ff4e-4421-997c-2d7dcab1b6ac/en-459-1-2015 (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Bonaccorsi, E.; Merlino, S.; Taylor, H.F.W. The crystal structure of jennite, Ca9Si6O18(OH)6·8H2O. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.F.W. Cement Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 1997; p. 457. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.; Kirkpatrick, R.J. Thermal dehydration of tobermorite and jennite. Concr. Sci. Eng. 1999, 1, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Balonis, M.; Glasser, F. The Density of Cement Phases. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridi, F.; Fratini, E.; Baglioni, P. Cement: A two thousand year old nano-colloid. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 357, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, S. The microstructure of cement paste and concrete—A visual primer. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2004, 26, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultrone, G.; Sebastián, E.; Ortega Huertas, M. Forced and natural carbonation of lime-based mortars with and without additives: Mineralogical and textural changes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 2278–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backbier, L.; Rousseau, J.; Bart, J.C.J. Analytical study of salt migration and efflorescence in a mediaeval cathedral. Anal. Chim. Acta 1993, 283, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smellie, J.A.T. Maqarin Natural Analogue Study: Phase III; SKB Technical Report; SKB: Stockholm, Sweden, 1998; Volume 98-04. [Google Scholar]

- Lothenbach, B.; Bernard, E.; Mäder, U. Zeolite formation in the presence of cement hydrates and albite. Phys. Chem. Earth 2017, 99, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, M.; Karatasios, I.; Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki, P.; Kilikoglou, V. The role of aggregate characteristics on the performance optimization of high hydraulicity restoration mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardi, C.; Brito de Carvalho Bello, C.; Ferrara, L.; Cecchi, A. Self-healing lime mortars: An asset for restoration of heritage buildings. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Materials Systems and Structures, Rovinj, Croatia, 20–22 March 2019; Baričević, A., Jelčić Rukavina, M., Damjanović, D., Guadagnini, M., Eds.; RILEM Publications: Marne-la-Vallée, France; pp. 652–659. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J.; Hilsdorf, H.K. 74. Ancient and new lime mortars–the correlation between their composition, structure and properties. In Conservation of Stone and Other Materials: Proceedings of the International RILEM/UNESCO Congress Held at the UNESCO Headquarters, Paris, France, June 29–July 1 1993; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1993; pp. 605–612. [Google Scholar]

- Papayianni, I.; Stefanidou, M. Mortars for intervention in monuments and historical buildings. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2003, 66, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.A.; Pinto, A.P.F.; Gomes, A. Natural hydraulic lime versus cement for blended lime mortars for restoration works. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 94, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Mortar/Rock Classification | Sample | Sampling Point | Minerals of Aggregate/Stone | Binder/Rock Matrix Phases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qz | K-Fds | Other Phases | Fossil | Cc | C-S-H | C-A-H | ||||

| Cement mortar | Arriccio 1 | CM-AR1-A | SM2 | xxx | xx | Pl, Bt, Se, (Ti), (Va), (Ep) | x | x | xx | x |

| CM-AR1-B | SM2 | xxx | xx | Pl, Bt, Va, Se, (Ti), (Ep) | (x) | (x) | xxx | xx | ||

| CM-AR1-A | SM3 | xxx | xx | Pl, Bt, (Ti), (Va), (Ep) | (x) | x | xx | x | ||

| CM-AR1-B | SM3 | xxx | xx | Pl, Bt, Va, (Ti), (Ep) | x | (x) | xxx | xx | ||

| CM-AR1-A | SM6 | xxx | xx | Pl, Bt, Fe-Ti, (Ep), (Zr) | (x) | x | xx | x | ||

| CM-AR1-B | SM6 | xxx | xx | Pl, Bt, Fe-Ti, (Zr), (Ep) | x | (x) | xxx | xx | ||

| Arriccio 2 | CM-AR2-A | SM7 | xx | x | Pl, Bt, (Ti), (Ep) | x | x | xx | x | |

| CM-AR2-B | SM7 | xx | x | Pl, (Bt), Gy, (Ti), (Ep) | x | x | xx | x | ||

| Hydraulic lime mortar | Arriccio 1 | HLM-AR1 | SM2 | (x) | (x) | Bt, Pl, Py, Ti, Cc | x | xx | x | x |

| HLM-AR1 | SM4 | ( ) | (x) | (Pl) | / | xx | x | x | ||

| HLM-AR1-A | SM5 | x | x | Bt, Pl, Py, Ti, Cc, (Gy) | x | xxx | xx | x | ||

| HLM-AR1-B | SM5 | x | (x) | Bt, Pl, Py, Cc, (Gy) | x | xxx | xx | x | ||

| HLM-AR1-A | SM7 | (x) | (x) | Bt, Pl, Py, Ti, Cc | x | xxx | x | x | ||

| HLM-AR1-B | SM7 | (x) | (x) | Bt, Pl, Py, Ti, Cc | x | xxx | x | x | ||

| Arriccio 2 | HLM-AR2 | SM3 | x | (x) | Pl, Gy | x | xx | (x) | x | |

| Arriccio 3 | HLM-AR3-A | SM8 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | x | xxx | (x) | x | |

| HLM-AR3-B | SM8 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | x | xxx | (x) | x | ||

| HLM-AR3-C | SM8 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | x | xxx | (x) | x | ||

| Finishing air lime plaster | Intonachino 1 | PL-INT1 | SM3 | ( ) | ( ) | n.d. | ( ) | xxxx | ( ) | ( ) |

| PL-INT1 | SM4 | ( ) | ( ) | n.d. | ( ) | xxxx | ( ) | ( ) | ||

| Intonachino 2 | PL-INT2 | SM1 | ( ) | ( ) | n.d. | ( ) | xxxx | ( ) | ( ) | |

| PL-INT2 | SM5 | ( ) | ( ) | n.d. | ( ) | xxxx | ( ) | ( ) | ||

| Intonachino 3 | PL-INT3 | SM4 | ( ) | ( ) | Gy | ( ) | xxxx | ( ) | ( ) | |

| Finishing lime paint | Lime paint | PA1, 2, 3 | SM1/4/5 | ( ) | ( ) | n.d. | ( ) | xx | ( ) | ( ) |

| Tramezzario stone | Limestone | TR | SM1 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | xxx | xxxx | n.d. | n.d. |

| TR | SM3 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | xxx | xxxx | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| TR | SM5 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | xxx | xxxx | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| TR | SM6 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | xxx | xxxx | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| TR | SM7 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | xxx | xxxx | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| TR | SM8 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | xxx | xxxx | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| TR | SM4 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | xxx | xxxx | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Strong Limestone | TR-S | SM2 | (x) | (x) | n.d. | xxx | xxxx | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Sample | Sampling Point | Mortar Group | Mortar/Rock Classification | Binder (%) | Aggregate (%) | Macro-pores (%) |

| CM-AR1-A | SM2 | Cement mortar | Arriccio 1 | 52.3 | 43.7 | 4.1 |

| CM-AR1-B | SM2 | 56.2 | 43.7 | 0.1 | ||

| CM-AR1-B | SM3 | 62.8 | 36.7 | 0.5 | ||

| CM-AR1-A | SM6 | 53.1 | 44.4 | 2.5 | ||

| CM-AR2-A | SM7 | Cement mortar | Arriccio 2 | 66.8 | 20.0 | 13.2 |

| Mean | 58.2 | 37.7 | 4.1 | |||

| St. Dev. | 6.3 | 10.4 | 5.3 | |||

| HLM-AR1 | SM7 | Hydraulic lime mortar | Arriccio 1 | 66.8 | 20.0 | 13.2 |

| HLM-AR2 | SM3 | Arriccio 2 | 62.8 | 36.7 | 0.5 | |

| HLM-AR3 | SM8 | Arriccio 3 | 78.0 | 17.3 | 4.7 | |

| Mean | 69.2 | 24.7 | 6.1 | |||

| St. Dev. | 7.9 | 10.5 | 6.5 | |||

| PL-INT1 | SM3 | Finishing air lime plaster | Intonachino 1 | 92.9 | 3.1 | 4.0 |

| PL-INT1 | SM4 | 86.7 | 6.4 | 6.9 | ||

| PL-INT1 | SM6 | 89.7 | 7.2 | 3.1 | ||

| Mean | 89.8 | 5.6 | 4.6 | |||

| St. Dev. | 3.6 | 1.9 | 1.7 | |||

| PL-INT2 | SM5 | Finishing air lime plaster | Intonachino 2 | 88.1 | 6.3 | 5.6 |

| PL-INT2 | SM1 | 80.7 | 18.1 | 1.2 | ||

| Mean | 84.4 | 12.2 | 3.4 | |||

| St. Dev. | 5.3 | 8.4 | 3.1 | |||

| PL-INT3 | SM4 | Finishing air lime plaster | Intonachino 3 | 87.4 | 8.1 | 4.5 |

| Groups | ρR | ρB | ΦO He | ΦO H2O | ΦC H2O | ICW | SI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/cm3 | g/cm3 | % | % | % | % | % | |

| CM-AR1 | 2.54 | 1.98 | 22.1 | 11.8 | 10.3 | 6.0 | 53.4 |

| CM-AR1 | 2.52 | 1.96 | 22.3 | 13.0 | 9.3 | 6.6 | 58.5 |

| CM-AR1 | 2.56 | 1.84 | 28.2 | 20.1 | 8.1 | 10.9 | 71.5 |

| CM-AR1 | 2.56 | 1.84 | 28.0 | 14.9 | 13.1 | 8.1 | 53.2 |

| CM-AR1 | 2.56 | 1.98 | 22.7 | 17.1 | 5.7 | 8.7 | 75.3 |

| CM-AR1 | 2.57 | 1.99 | 22.6 | 15.8 | 6.8 | 8.0 | 70.1 |

| Mean | 2.55 | 1.93 | 24.3 | 15.4 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 63.7 |

| St. Dev. | 0.02 | 0.07 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 9.8 |

| CM-AR2 | 2.57 | 1.86 | 27.6 | 16.5 | 11.1 | 8.9 | 59.8 |

| CM-AR2 | 2.60 | 1.90 | 27.1 | 20.5 | 6.6 | 10.8 | 75.8 |

| Mean | 2.59 | 1.88 | 27.4 | 18.5 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 67.8 |

| St. Dev. | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 1.4 | 11.3 |

| HLM-AR1 | 2.61 | 1.87 | 28.4 | 17.0 | 11.4 | 9.1 | 60.1 |

| HLM-AR1 | 2.59 | 1.72 | 33.5 | 23.0 | 10.5 | 13.4 | 68.9 |

| HLM-AR1 | 2.62 | 1.73 | 34.0 | 25.4 | 8.6 | 14.8 | 74.9 |

| HLM-AR1 | 2.58 | 1.82 | 29.5 | 18.1 | 11.5 | 9.9 | 61.3 |

| HLM-AR1 | 2.63 | 1.70 | 35.2 | 19.5 | 15.8 | 11.4 | 55.3 |

| HLM-AR1 | 2.65 | 1.82 | 31.3 | 19.5 | 11.8 | 10.7 | 62.3 |

| Mean | 2.61 | 1.78 | 32.0 | 20.4 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 63.8 |

| St. Dev. | 0.02 | 0.07 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 7.0 |

| HLM-AR2 | 2.62 | 1.57 | 40.2 | 32.2 | 8.0 | 20.6 | 80.3 |

| HLM-AR3 | 2.68 | 1.67 | 37.7 | 29.2 | 8.5 | 17.5 | 77.6 |

| HLM-AR3 | 2.68 | 1.59 | 40.7 | 26.3 | 14.4 | 16.6 | 64.7 |

| HLM-AR3 | 2.67 | 1.65 | 38.3 | 28.8 | 9.5 | 17.5 | 75.3 |

| Mean | 2.68 | 1.63 | 38.9 | 28.1 | 10.8 | 17.2 | 72.5 |

| St. Dev. | 0.003 | 0.04 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 6.9 |

| PL-INT1 | 2.53 | 1.61 | 36.3 | 20.0 | 16.3 | 12.4 | 55.1 |

| PL-INT1 | 2.42 | 1.53 | 36.8 | 12.8 | 24.0 | 8.4 | 34.8 |

| Mean | 2.47 | 1.57 | 36.6 | 16.4 | 20.2 | 10.4 | 44.9 |

| St. Dev. | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.4 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 2.9 | 14.4 |

| PL-INT2 | 2.54 | 1.82 | 28.2 | 14.6 | 13.6 | 8.1 | 52.0 |

| PL-INT2 | 2.61 | 1.73 | 33.7 | 19.7 | 14.0 | 11.4 | 58.5 |

| Mean | 2.57 | 1.77 | 31.0 | 17.2 | 13.8 | 9.7 | 55.2 |

| St. Dev. | 0.05 | 0.07 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 4.7 |

| PL-INT3 | 2.59 | 1.87 | 27.6 | 10.9 | 16.6 | 5.8 | 39.7 |

| TR | 2.70 | 2.13 | 21.3 | 9.4 | 11.8 | 4.4 | 44.4 |

| TR | 2.70 | 2.06 | 23.8 | 11.3 | 12.5 | 5.5 | 47.7 |

| TR | 2.71 | 1.89 | 30.4 | 21.1 | 9.3 | 11.2 | 69.6 |

| TR | 2.72 | 1.91 | 29.7 | 22.0 | 7.7 | 11.5 | 74.2 |

| TR | 2.72 | 2.05 | 24.9 | 16.2 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 65.1 |

| TR | 2.70 | 1.98 | 26.7 | 21.0 | 5.7 | 10.6 | 78.8 |

| TR | 2.71 | 2.12 | 21.9 | 10.2 | 11.7 | 4.8 | 46.6 |

| Mean | 2.71 | 2.02 | 25.5 | 15.9 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 60.9 |

| St. Dev. | 0.01 | 0.09 | 3.6 | 5.6 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 14.4 |

| TR-S | 2.68 | 2.57 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 56.9 |

| Groups Sigle | mD | mW 24 h | mW 48 h | mW 72 h | mW 96 h | mW 120 h | ICW 24 h | ICW 48 h | ICW 72 h | ICW 96 h | ICW 120 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g | g | g | g | g | g | % | % | % | % | % | |

| CM-AR1 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 6.1 |

| CM-AR1 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 7.2 |

| CM-AR1 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 11.5 |

| CM-AR1 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 7.4 |

| CM-AR1 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 8.2 | 7.2 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.5 |

| CM-AR1 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 7.7 | 9.5 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.5 |

| Average | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.5 |

| St. Dev. | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| CM-AR2 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 10.6 |

| CM-AR2 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 11.5 | 12.8 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 13.5 |

| Average | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 10.3 | 11.2 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 12.1 |

| St. Dev. | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| HLM-AR1 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 8.6 | 10.2 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 10.2 |

| HLM-AR1 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 13.9 | 14.5 | 13.8 | 14.3 | 14.5 |

| HLM-AR2 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 15.6 | 16.0 | 15.5 | 15.5 | 16.0 |

| HLM-AR3 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 12.2 |

| HLM-AR3 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 12.9 | 12.9 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 13.1 |

| HLM-AR5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Mean | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 11.2 | 11.3 |

| St. Dev. | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.0 |

| HLM-AR2 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 19.2 | 20.2 | 20.4 | 20.4 | 20.5 |

| HLM-AR3 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 16.9 | 17.0 | 17.8 | 17.8 | 17.8 |

| HLM-AR3 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 18.0 | 18.9 | 19.1 | 19.1 | 19.3 |

| HLM-AR3 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 18.6 | 19.2 | 18.5 | 18.8 | 19.2 |

| Mean | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 17.9 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 18.6 | 18.8 |

| St. Dev. | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| PL-INT1 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 21.1 | 21.4 | 21.5 |

| PL-INT1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 13.0 | 13.1 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 13.1 |

| Mean | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 16.7 | 16.9 | 17.3 |

| St. Dev. | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.0 |

| PL-INT2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 15.2 | 22.8 | 23.4 | 23.6 | 23.6 |

| PL-INT2 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 12.0 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.6 | 15.2 |

| Mean | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 13.6 | 18.5 | 18.8 | 19.1 | 19.4 |

| St. Dev. | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 6.0 |

| PL-INT3 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 11.3 |

| TR | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 5.8 |

| TR | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 6.4 |

| TR | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 11.3 | 11.7 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 12.3 |

| TR | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 11.3 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 12.3 | 12.3 |

| TR | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 9.5 |

| TR | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 11.6 |

| TR | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.3 |

| Mean | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.9 |

| St. Dev. | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| TR-S | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Columbu, S.; Usai, M.; Rispoli, C.; Fancello, D. Lime and Cement Plasters from 20th Century Buildings: Raw Materials and Relations between Mineralogical–Petrographic Characteristics and Chemical–Physical Compatibility with the Limestone Substrate. Minerals 2022, 12, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12020226

Columbu S, Usai M, Rispoli C, Fancello D. Lime and Cement Plasters from 20th Century Buildings: Raw Materials and Relations between Mineralogical–Petrographic Characteristics and Chemical–Physical Compatibility with the Limestone Substrate. Minerals. 2022; 12(2):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12020226

Chicago/Turabian StyleColumbu, Stefano, Marco Usai, Concetta Rispoli, and Dario Fancello. 2022. "Lime and Cement Plasters from 20th Century Buildings: Raw Materials and Relations between Mineralogical–Petrographic Characteristics and Chemical–Physical Compatibility with the Limestone Substrate" Minerals 12, no. 2: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12020226

APA StyleColumbu, S., Usai, M., Rispoli, C., & Fancello, D. (2022). Lime and Cement Plasters from 20th Century Buildings: Raw Materials and Relations between Mineralogical–Petrographic Characteristics and Chemical–Physical Compatibility with the Limestone Substrate. Minerals, 12(2), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12020226