Mining Exploration, Raw Materials and Production Technologies of Mortars in the Different Civilization Periods in Menorca Island (Spain)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Site Description

3. Geological Setting of Menorca Island

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Optical Microscopy and X-ray Diffractometry

4.3. Physical and Mechanical Tests

4.4. Binder/Aggregate Ratio by Imaging Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Mineralogical and Petrographic Characteristics of Mortars

- Pit sector

- Cistern sector

- House-fort sector

5.1.1. Samples from the Pit

- Group P1—Cocciopesto Mortar (Samples MIN2, MIN7)

- Group P2a—Blackish Cocciopesto Mortar (MIN3, MIN4)

- Groups P2b—Cocciopesto Mortars with Compacted Clay (MIN1)

- Group P3—Fine Lime Plaster with Rare Cocciopesto (MIN6, MIN8)

- Group P4—Limestone Samples from the Mortars (MIN5, MIN9, MIN10)

5.1.2. Samples from the Ancient Water Cistern

5.1.3. Samples from the House-Fort

- Group H—Mortar with Lime/Gypsum Binder (MIN13)

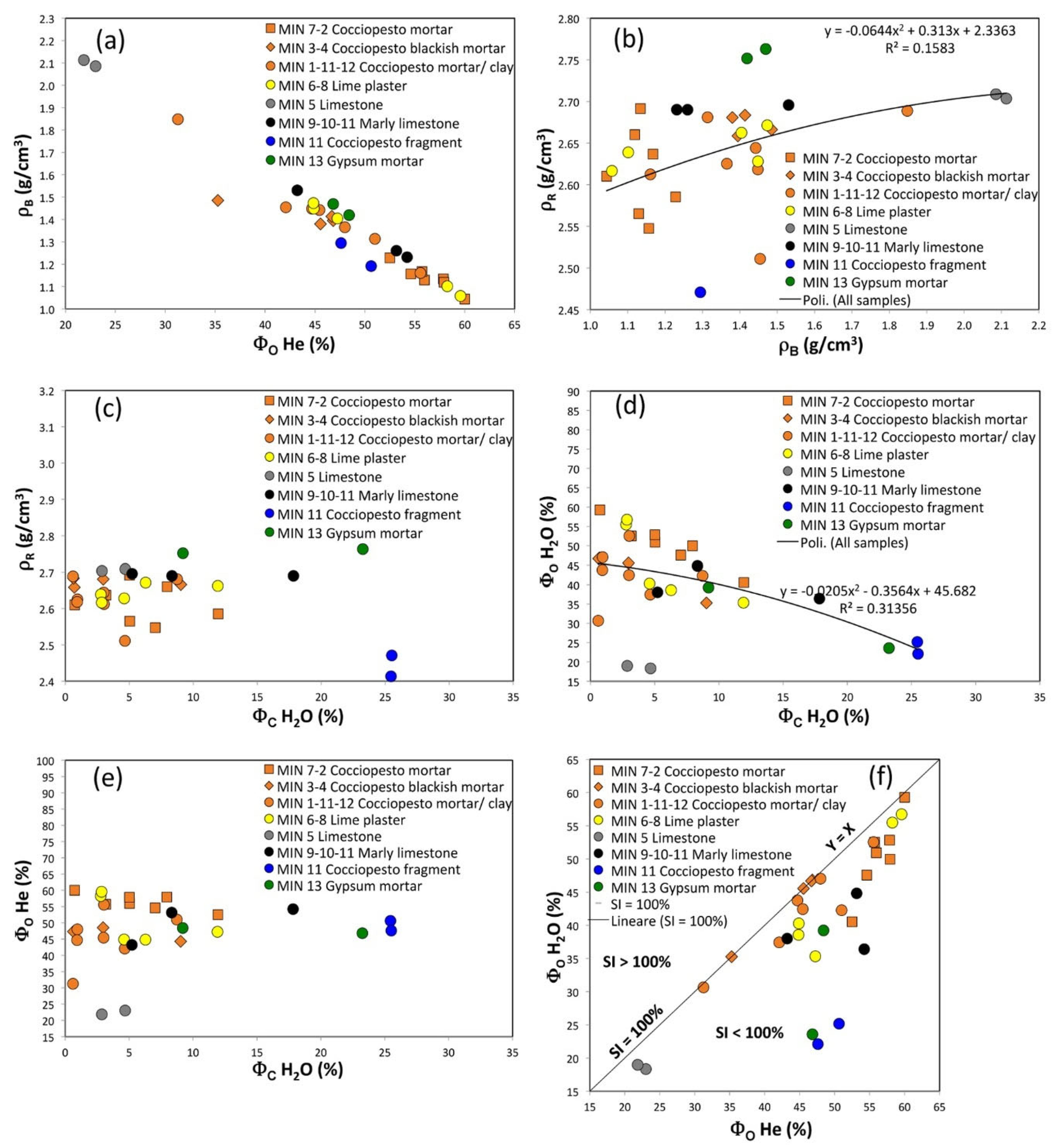

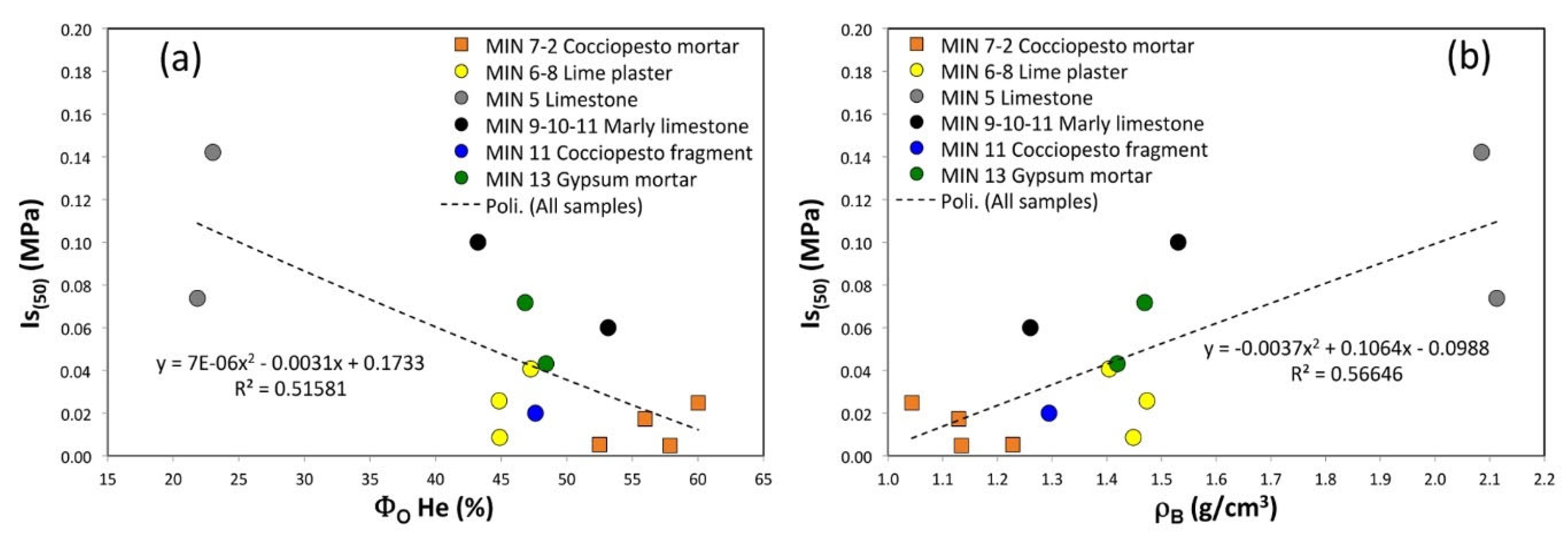

5.2. Physical-Mechanical Features of Mortars

6. Discussion

6.1. Function of Mortars and Compositional Features

- cocciopesto mortars from the pit (groups P1, P2a) with a subordinate fraction of silicate aggregate (e.g., quartz, feldspar, other minor phases) which in some cases shows combustion traces (Group P2);

- mortars with a cocciopesto aggregate from the pit (subgroups P2b) and from cistern (subgroups C1, C2) with a significant fraction of silicate phases (represented by quartz, feldspars and biotite), and with subordinate clay and particles resulting from combustion adhering to the surface;

- fine mortars from the pit (group P3) made with a very fine silicate aggregate (substantially of Qtz) in very low percentages (usually <7%) and only in a very subordinate way by small fragments of cocciopesto (probably occasional) and limestone;

- mortars with a substantially quartz aggregate and subordinate presence of cocciopesto and limestone fragments (group H).

- mortars (P1, P2a, P2b, P3, C1 groups) with a binder consisting mainly of calcite and pseudo-crystalline-amorphous Ca-carbonatic phases co-precipitated during the carbonation of the binder or secondary phases induced by the alteration of CaCO3;

- mortars (H group) with a lime and gypsum-based binder, with the presence of bassanite, magnesite and anhydrite deriving from the prolonged drying phase of the samples in the oven (T = 115 °C, during the laboratory preparation of samples) which led to the dehydration of the original plaster.

6.2. Materials from the Pit and the Cistern

- laying of the various mortar samples on a poorly- to well-compacted clay layer, referable to the substrate of the flooring or of the wall underlying the mortar;

- presence of fine-grained mortar samples with a very high binder/aggregate ratio (95/5%), probably referable to the external finishing layer;

- poor resistance of the mortars which would not have had good physical-mechanical characteristics to withstand the loads of the imposing stone walls.

6.3. Mortars from the House-Fort

6.4. Provenance of Raw Materials

7. Conclusions

- Mortars were not used in the constructions of the Talaiotic phase as highlighted, for instance, by the water cistern, whose sealing by plastering occurred in later times;

- The use of mortars to seal the cistern occurred during the Roman phase as testified by cocciopesto aggregates and further confirmed by radiocarbon dating carried out on charcoal frustules inside two cocciopesto-mortars found at the bottom of the cistern, that date the materials at 1st century BC—4th century AD ([62], in press);

- Two kinds of mortars, one with a coarse aggregate, another with a finer aggregate, were found. The coarser one, called Rudus, was used in contact with the rock as indicated by soil adhering to the samples); the finer one rich in cocciopesto was a kind of finishing plaster;

- The strong decay of these mortars is largely due to the weathering but indicates also a low hydraulicity of mortars and thus a low reactivity of cocciopesto. This led us to make some hypotheses on the provenance of pottery used to produce cocciopesto that are worth being further investigated.

- The mortars from the house-fort are significantly different from those from the cistern, being gypsum based. By checking the literature, it is found that gypsum was widely used for plastering in the period of the house-fort settlement (17th–18th century) in different parts of Spain and that a local source of raw materials is found in the nearby Mallorca Island.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karner, D.B.; Lombardi, L.; Marra, F.; Fortini, P.; Renne, P.R. Age of ancient monuments by means of building stone provenance: A case study of the Tullianum, Rome, Italy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2001, 28, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Antonelli, F.; Lezzerini, M.; Miriello, D.; Adembri, B.; Blanco, A. Provenance of marbles used in the Heliocaminus Baths of Hadrian’s Villa (Tivoli, Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 49, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Gaviano, E.; Costamagna, L.G.; Fancello, D. Mineralogical-petrographic and physical-mechanical features of the construction stones in Punic and Roman temples of Antas (SW Sardinia, Italy): Provenance of the raw materials and conservation state. Minerals 2021, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, G. Ceramic raw materials. In The Oxford Handbook of Archaeological Ceramic Analysis; Hunt, A.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, A.; Kilikoglou, V. Ceramic raw materials: How to recognize them and locate the supply basins: Chemistry. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L.A.; Zuluaga, M.C.; Alonso-Olazabal, A.; Murelaga, X.; Alday, A. Petrographic and geochemical evidence for long-standing supply of raw materials in neolithic pottery (Mendandia site, Spain). Archaeometry 2010, 52, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. The raw materials of early glass production. Oxf. J. Archaeol. 1985, 4, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degryse, P.; Schneider, J. Pliny the Elder and Sr–Nd isotopes: Tracing the provenance of raw materials for Roman glass production. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brems, D.; Degryse, P.; Hasendoncks, F.; Gimeno, D.; Silvestri, A.; Vassilieva, E.; Luypaers, E.; Honings, J. Western Mediterranean sand deposits as a raw material for Roman glass production. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 2897–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Garau, A.M.; Lugliè, C. Geochemical characterisation of pozzolanic obsidian glasses used in the ancient mortars of Nora Roman theatre (Sardinia, Italy): Provenance of raw materials and historical–archaeological implications. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 2121–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Sitzia, F.; Ennas, G. The ancient pozzolanic mortars and concretes of Heliocaminus baths in Hadrian’s Villa (Tivoli, Italy). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2017, 9, 523–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, J.; Mutterlose, J.; Kaplan, U. Calcareous nannofossils in medieval mortar and mortar-based materials: A powerful tool for provenance analysis. Archaeometry 2021, 63, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L.A.; Zuluaga, M.C.; Alonso-Olazabal, A.; Insausti, M.; Ibañez, A. Geochemical characterization of archaeological lime mortars: Provenance inputs. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsen, J.; Mertens, G.; Van Balen, K. Raw materials used in ancient mortars from the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Tournai (Belgium). Eur. J. Mineral. 2011, 23, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Garau, A.M. Mineralogical, petrographic and chemical analysis of geomaterials used in the mortars of Roman Nora theatre (south Sardinia, Italy). Ital. J. Geosci. 2017, 136, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquafredda, P.; Muntoni, I.M. Obsidian from Pulo di Molfetta (Bari, Southern Italy): Provenance from Lipari and first recognition of a Neolithic sample from Monte Arci (Sardinia). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiore, C.M.; Ricca, M.; La Russa, M.F.; Ruffolo, S.A.; Galli, G.; Barca, D.; Malagodi, M.; Vallefuoco, M.; Sprovieri, M.; Pezzino, A. Provenance study of building and statuary marbles from the Roman archaeological site of “Villa dei Quintili” (Rome, Italy). Ital. J. Geosci. 2016, 135, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S. Petrographic and geochemical investigations on the volcanic rocks used in the Punic-Roman archaeological site of Nora (Sardinia, Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLaine, J. Production, transport and on-site organisation of Roman mortars and plasters. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2021, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavon, N.; Mazzocchin, G.A. The provenance of sand in mortars from Roman villas in NE Italy: A chemical–mineralogical approach. Open Mineral. J. 2009, 3, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Borsoi, G.; Silva, A.S.; Menezes, P.; Candeias, A.; Mirão, J.A.P. Analytical Characterization of Ancient Mortars from the Archaeological Roman Site of Pisões (Beja, Portugal). Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 204, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Columbu, S.; Lisci, C.; Sitzia, F.; Lorenzetti, G.; Lezzerini, M.; Pagnotta, S.; Raneri, S.; Legnaioli, S.; Palleschi, V.; Gallello, G.; et al. Mineralogical, petrographic and physical-mechanical study of Roman construction materials from the Maritime Theatre of Hadrian’s Villa (Rome, Italy). Measurement 2018, 127, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, C.; De Bonis, A.; Esposito, R.; Graziano, S.F.; Langella, A.; Mercurio, M.; Morra, V.; Cappelletti, P. Unveiling the secrets of roman craftsmanship: Mortars from Piscina Mirabilis (Campi Flegrei, Italy). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Palomba, M.; Sitzia, F.; Murgia, M.R. Geochemical, mineral-petrographic and physical-mechanical characterisation of stones and mortars from the Romanesque Saccargia Basilica (Sardinia, Italy) to define their origin and alteration. Ital. J. Geosci. 2018, 137, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, F.; D’Ambrosio, E.; Gaeta, M.; Mattei, M. Petrochemical identification and insights on chronological employment of the volcanic aggregates used in ancient Roman mortars. Archaeometry 2016, 58, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocka, D.; Michniewicz, J.; Pawlyta, J.; Pazdur, A. Application of radiocarbon method for dating of lime mortars. Geochronometria 2005, 24, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pavía, S.; Caro, S. An investigation of Roman mortar technology through the petrographic analysis of archaeological material. Constr. Build. Mat. 2008, 22, 1807–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramacciotti, M.; Rubio, S.; Gallello, G.; Lezzerini, M.; Columbu, S.; Hernandez, E.; Morales-Rubio, A.; Pastor, A.; De La Guardia, M. Chronological classification of ancient mortars employing spectroscopy and spectrometry techniques: Sagunto (Valencia, Spain) Case. J. Spectrosc. 2018, 2018, 9736547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sitzia, F. The San Saturnino Basilica (Cagliari, Italy): An Up-Close Investigation about the Archaeological Stratigraphy of Mortars from the Roman to the Middle Ages. Heritage 2021, 4, 1836–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waelkens, M.; Herz, N.; Moens, L. Ancient Stones: Quarrying, trade and provenance: Interdisciplinary studies on stones and stone technology in Europe and near East from the Prehistoric to the Early Christian Period (No. 4); Leuven University Press: Leuven, Belgium, 1992; ISBN 978-9061864943. [Google Scholar]

- Columbu, S.; Palomba, M.; Sitzia, F.; Carcangiu, G.; Meloni, P. Pyroclastic Stones as Building Materials in Medieval Romanesque Architecture of Sardinia (Italy): Chemical-Physical Features of Rocks and Associated Alterations. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2022, 16, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moropoulou, A.; Polikreti, K.; Bakolas, A.; Michailidis, P. Correlation of physicochemical and mechanical properties of historical mortars and classification by multivariate statistics. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 33, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Gioncada, A.; Lezzerini, M.; Sitzia, F. Mineralogical-chemical alteration and origin of ignimbritic stones used in the old Cathedral of Nostra Signora di Castro (Sardinia, Italy). Stud. Conserv. 2019, 64, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragoni, M.C.; Giacopetti, L.; Arca, M.; Carcangiu, G.; Columbu, S.; Gimeno, D.; Isaia, F.; Lippolis, V.; Meloni, P.; Ezquerra, A.N.; et al. Ammonium monoethyloxalate (AmEtOx): A new agent for the conservation of carbonate stone substrates. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 5327–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzia, F.; Beltrame, M.; Columbu, S.; Lisci, C.; Miguel, C.; Mirão, J. Ancient restoration and production technologies of Roman mortars from monuments placed in hydrogeological risk areas: A case study. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Degryse, P.; Elsen, J.; Waelkens, M. Study of ancient mortars from Sagalassos (Turkey) in view of their conservation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morricone, A.; Macchia, A.; Campanella, L.; David, M.; de Togni, S.; Turci, M.; Maras, A.; Meucci, C.; Ronca, S. Archeometrical analysis for the characterization of mortars from Ostia Antica. Procedia Chem. 2013, 8, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Columbu, S. Provenance and alteration of pyroclastic rocks from the Romanesque Churches of Logudoro (north Sardinia, Italy) using a petrographic and geochemical statistical approach. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2017, 123, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vola, G.; Gotti, E.; Brandon, C.; Oleson, J.P.; Hohlfelder, R.L. Chemical, mineralogical and petrographic characterization of roman ancient hydraulic concretes cores from Santa Liberata, Italy, and Caesarea Palestinae, Israel. Period. Miner. 2011, 80, 317–338. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, F.; Columbu, S.; Lezzerini, M.; Miriello, D. Petrographic characterisation and provenance determination of the white marbles used in the roman sculptures of Forum Sempronii (Fossombrone, Marche, Italy). Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2014, 115, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Columbu, S.; De Vos Raaijmakers, M.; Andreoli, M. An archaeometric contribution to the study of ancient millstones from the Mulargia area (Sardinia, Italy) through new analytical data on volcanic raw material and archaeological items from Hellenistic and Roman North Africa. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 50, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depalmas, A. New data from fortified coastal settlement of Cap de Forma, Mahon, Menorca (Balearic Islands). Radiocarbon 2014, 56, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarda Mata, F. (Ed.) Menorca Talayótica; Alfajarin, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-96810-41-9. [Google Scholar]

- Plantalamor Massanet, L.; Tanda, G.; Tore, G.; Baldaccini, P.; Del Vais, C.; Depalmas, A.; Marras, G.; Mameli, P.; Mulé, P.; Oggiano, G.; et al. Cap de Forma (Minorca): La navigazione nel Mediterraneo occidentale dall’età del bronzo all’età del ferro. Nota preliminare. In Antichità Sarde. Studi e Ricerche 5; Tanda, G., Ed.; Stamperia Artistica; Università di Sassari: Sassari, Italy, 1999; pp. 11–160. [Google Scholar]

- SEGUÍ, T. Las excavaciones de Cap de Forma descubren una cisterna talayótica. Menorca.info. Maó: Editorial Menorca S.A., Spain. 2011. Edición electrónica en. Available online: https://www.menorca.info/menorca/local/2011/06/26/1404306/excavaciones-cap-forma-descubren-cisterna-talayotica.html (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Depalmas, A.; Columbu, S. Modern Age Fortifications of the Mediterranean Coast–Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean: XV to XVIII Centuries (Fortmed 2015); Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València, Ed.; Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2015; Volume II, pp. 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero-Mozo, M.J.; Martín-Chivelet, J.; Goy, A.; López-Gómez, J. Middle-Upper Triassic carbonate platforms in Minorca (Balearic Islands): Implications for Western Tethys correlations. Sediment. Geol. 2014, 310, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, E.; Wortel, M.J.R.; Spakman, W.; Sabadini, R. The role of slab detachment processes in the opening of the western–central Mediterranean basins: Some geological and geophysical evidence. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 1998, 160, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sàbat, F.; Gelabert, B.; Rodriguez-Perea, A.R. Minorca, an exotic Balearic island (western Mediterranean). Geol. Acta 2018, 16, 411–426. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell, J.; Elízaga, E. Evolución tectosedimentaria del Paleozoico de la isla de Menorca. Bol. Geol. Min. 1989, 100, 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Elízaga, E.; Rosell, J.; Gómez, D. Mapa Geológico de la Isla de Menorca a escala 1:100.000. Cartografía geológica regional, 1992. ©Instituto Geológico y Minero de España (IGME). Available online: http://info.igme.es/cartografiadigital/geologica/mapa.aspx?parent=../geologica/geologiaregional.aspx&Id=2&language=es (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Linol, B.; Bercovici, A.; Bourquin, S.; Diez, J.B.; López-Gómez, J.; Broutin, J.; Durand, M.; Villanueva-Amadoz, U. Late Permian to Middle Triassic correlations and palaeogeographical reconstructions in south-western European basins: New sedimentological data from Minorca (Balearic Islands, Spain). Sediment. Geol. 2009, 220, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornós, J.J.; Pomar, L.; Ramos-Guerrero, E. Balearic Islands. In The Geology of Spain; Gibbons, W., Moreno, T., Eds.; The Geological Society: London, UK, 2002; pp. 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Obrador, A.; Pomar, L.; Rodriguez, A.; Jurado, M.J. Unidades deposicionales del Neógeno menorquín. Acta Geol. Hispán. 1983, 18, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pomar, L.; Obrador, A.; Westphal, H. Sub-wavebase cross-bedded grainstones on a distally steepened carbonate ramp, Upper Miocene, Menorca, Spain. Sedimentology 2002, 49, 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Mulas, M.; Mundula, F.; Cioni, R. Strategies for helium pycnometry density measurements of welded ignimbritic rocks. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2021, 173, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, S.; Cruciani, G.; Fancello, D.; Franceschelli, M.; Musumeci, G. Petrophysical properties of a granite-protomylonite-ultramylonite sequence: Insight from the Monte Grighini shear zone, central Sardinia, Italy. Eur. J. Mineral. 2014, 27, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISRM-Int. Society for Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. Suggested method for determining the point load strength index. In International Society for Rock Mechanics; Document 1: 8–12; Committee on Field Tests, ISRM: Lisbon, Portugal, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- ISRM-International Society for Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. Suggested method for determining the point load strength. In International Society for Rock Mechanics; Abstr 22: 51–60; ISRM Commission for Testing Methods, Working Group on Revision of the Point Load Test Methods, ISRM: Lisbon, Portugal, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Roduit, N. JMicroVision: Image Analysis Toolbox for Measuring and Quantifying Components of High-Definition Images. Version 1.3.3. Available online: https://jmicrovision.github.io (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Anglada, M.; Ferrer, A.; Plantalamor, L.; Ramis, D.; Van Strydonck, M.; De Mulder, G. Chronological framework for the early Talayotic period in Menorca: The settlement of Cornia Nou. Radiocarbon 2014, 56, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depalmas, A. Cap de Forma–Maó. Un asentamiento costero de la Edad del Bronce. Aracne: Roma, Italy, in press.

- Ranieri, G.; Godio, A.; Loddo, F.; Stocco, S.; Casas, A.; Capizzi, P.; Messina, P.; Orfila, M.; Cau, M.A.; Chávez, M.E. Geophysical prospection of the Roman city of Pollentia, Alcúdia (Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain). J. Appl. Geophys. 2016, 134, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J. A Study of the Circulation of Ceramics in Cyprus from the 3rd Century BC to the 3rd Century AD; Aarhus University Press: Aarhus, Denmark, 2015; ISBN 978 87 7124 450 2. [Google Scholar]

- Freestone, I.C.; Rigby, V. The introduction of Roman ceramic styles and techniques into Roman Britain: A case study from the King Harry Lane Cemetery, St. Albans, Hertfordshire. In MRS Online Proceedings Library Archive; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988; Volume 123. [Google Scholar]

- Plantalamor Massanet, L. L’arquitectura prehistòrica i protohistòrica de Menorca i el seu marc cultural. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.S.; Cruz, T.; Paiva, M.J.; Candeias, A.; Adriano, P.; Schiavon, N.; Mirão, J.A.P. Mineralogical and chemical characterization of historical mortars from military fortifications in Lisbon harbour (Portugal). Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 63, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R.; Ontiveros, M.C.; Miriello, D.; Pecci, A.; Le Pera, E.; Bloise, A.; Crisci, G.M. Archaeometric study of mortars and plasters from the Roman City of Pollentia (Mallorca-Balearic Islands). Period. Mineral. 2013, 82, 353–379. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran, S.; Anbalagan, G. Thermal decomposition of natural dolomite. Bull. Mat. Sci. 2007, 30, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Artioli, G.; Secco, M.; Addis, A. The Vitruvian legacy: Mortars and binders before and after the Roman world. EMU Notes Miner. 2019, 20, 151–202. [Google Scholar]

- Aphane, M.E. The hydration of magnesium oxide with different reactivities by water and magnesium acetate. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell, J.R.; Haurie, L.; Navarro, A.; Cantalapiedra, I.R. Influence of the traditional slaking process on the lime putty characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 55, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki, P.; Bakolas, A.; Moropoulou, A. Physico-chemical study of Cretan ancient mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet, J.M.; Gosselin, C.; Bromblet, P.; Rolland, O.; Vergès-Belmin, V.; Kloppmann, W. Origin of salts in stone monument degradation using sulphur and oxygen isotopes: First results of the Bourges cathedral (France). J. Geochem. Expl. 2006, 88, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J.; Artieda, O.; Hudnall, W.H. Gypsum, a tricky material. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2009, 73, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickels-Taves, L.B.; Allsopp, P.D. Lime and its place in the 21st century: Combining tradition, innovation, and science in building preservation. In Proceedings of the International Building Lime Symposium, Orlando, FL, USA, 9–11 March 2005; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Cowper, A.D. Lime and Lime Mortars; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781873394298. [Google Scholar]

- Rampazzi, L.; Pozzi, A.; Sansonetti, A.; Toniolo, L.; Giussani, B. A chemometric approach to the characterisation of historical mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pujol, L.; Roig-Munar, F.X.; Fornós, J.J.; Balaguer, P.; Mateu, J. Provenance-related characteristics of beach sediments around the island of Menorca, Balearic Islands (western Mediterranean). Geo-Marine Lett. 2013, 33, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- La Spina, V.; Mileto, C.; Vegas, F. Characterisation of Roman and Mediaeval renderings. The case of the remains found in archaeological excavations in the city of Valencia (Spain). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 10, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileto, C.; Vegas, F.; La Spina, V. Is gypsum external rendering possible? The use of gypsum mortar for rendering historic façades of Valencia’s city centre. In Advanced Materials Research; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Bäch, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 250, pp. 1301–1304. [Google Scholar]

- La Spina, V.; Fratini, F.; Cantisani, E.; Mileto, C.; Vegas López-Manzanares, F. The ancient gypsum mortars of the historical façades in the city center of Valencia (Spain). Period. Mineral. 2013, 82, 443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Fullana, A.G.; Bestard, D.C.; Arbós, P.B. Els forns de guix en les explotacions mineres històriques de la Serra de na Burguesa (Mallorca). Boll. Soc. Arqueol. Lul Liana Rev. D’estudis Històrics 2016, 72, 221–247. [Google Scholar]

- Bover, P.; Ginard, A.; Crespí, D.; Vicens, D.; Vadell, M.; Serra, J.; Santandreu, G.; Barceló, M.A. Les cavitats de la Serra de na Burguesa. Zona 6: La mineria a la Serra d’en Marill (Palma, Mallorca). Publicació D’espeleologia 2004, 26, 59–82. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/Endins/article/view/122499 (accessed on 23 December 2021).

| Sampling Points | Sector Strat. Unit | Localis. | Solid/ Powder | Material Description | Layer Nr. | Colour | Xeno-Components | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface | Matrix | |||||||

| MIN1 | D4e1 US25 | Pit | Solid | Mortar with silicatic aggregate, cocciopesto, with a layer of slightly compacted clay | 2 | Brown | Layer 1: red; Layer 2: Grey | Combustion traces of clay layer |

| MIN2 | D4e1 US25 | Pit | Solid incoherent | Mortar with cocciopesto, silicatic aggregate and lithics | 1 | Brown | Reddish | Bone/wood fragments |

| MIN3 | D42d US22 | Pit | Solid semi-incoherent | Blackish mortar with cocciopesto, silicatic aggregate, limestone fragments | 1 | Blackish | Whitish | Combustion traces |

| MIN4 | D42d US22 | Pit | Solid incoherent | Blackish mortar with cocciopesto, silicatic aggregate, limestone fragments | 2 | Brown | Layer 1: red; Layer 2: black | Combustion traces |

| MIN5 | D42d US22 | Pit | Solid compacted | Limestone with small mortar layer | 1 | Whitish/ brown | Grey | / |

| MIN6 | D42d US22 | Pit | Solid | Fine lime plaster with rare silicatic aggregate, cocciopesto and limestone fragments | 1 | Whitish/Light brown | Whitish | / |

| MIN7 | D42d US22 | Pit | Solid incoherent | Mortar with cocciopesto, silicatic aggregate and lithics | 2 | Whitish/Light brown | Reddish | Combustion traces |

| MIN8 | D42d US22 | Pit | Solid | Fine lime plaster with rare silicatic aggregate, cocciopesto and limestone fragments | 2 | Light brown | Whitish | / |

| MIN9 | D4e1 US25 | Pit | Solid compacted | Fine porous limestone | n.d. | Whitish/Brown/Black | Whitish | / |

| MIN10 | D4e1 US25 | Pit | Solid compacted | Fine porous limestone + mortar layer | 1 + mortar patina | Strong brown | Grey | Combustion traces |

| MIN11-1 | C7e3-4,d3-4 US153-154 | Cistern | Incoherent + fragments | Fine marly limestone | n.d. | Ochre | Beige | / |

| MIN11-2 | C7e3-4,d3-4 US153-154 | Cistern | Solid | Cocciopesto mortar with a layer of slightly compacted clay | 2 | Whitish/Light brown | Whitish | Clay |

| MIN11-3 | C7e3-4,d3-4 US153-154 | Cistern | Solid | Cocciopesto fragment | n.d. | Reddish | Reddish | / |

| MIN12 | C7e3-4,d3-4 US153-154 | Cistern | Incoherent + small fragments | Cocciopesto mortar with a layer of slightly compacted clay | 2 | Brown/Blackish | Whitish | Clay |

| MIN13 | A5d5 US134 | House-fort | Solid | Mortar with silicatic aggregate and binder | 1 | Whitish/Light brown | Whitish | / |

| Sample | Site | Group | Material Type | Imaging Analysis | Microscopic Analysis (PL-OM) | Minerals by XRD Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregate % | Binder % | Components | Aggregate | Binder | ||||

| MIN2 | Pit | P1 | Mortar | 28.1 | 70.9 | cocciopesto, quartz, limestone lithics, rare feldspar | Qtz, Cal, Dol, Arg | Cal |

| MIN7 | Pit | P1 | Mortar | n.d. | n.d. | cocciopesto, quartz, lithics | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN3 | Pit | P2a | Mortar | n.d. | n.d. | cocciopesto, quartz, limestone lithics | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN4 | Pit | P2a | Mortar | 35.8 | 58.3 | quartz, cocciopesto, calcareous lithics | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN1 | Pit | P2b | Mortar | 16.3 | 76.3 | quartz, rare feldspar and biotite, cocciopesto, limestone lithics | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN6 | Pit | P3 | Mortar | n.d. | n.d. | quartz, cocciopesto | Qtz, Cal, Dol | Cal, Per |

| MIN8 | Pit | P3 | Mortar | 4.8 | 92.5 | quartz, cocciopesto, limestone fragments | Qtz, Cal, Dol | Cal, Per, (Mgs) |

| MIN9 | Pit | P4a | Limestone/Mortar | n.d. | n.d. | microcrystalline calcite (in limestone), quartz (in mortar layer) | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN10 | Pit | P4a | Limestone/Mortar | 4.9 | 89.6 | microcrystalline calcite (in limestone), quartz and cocciopesto (in mortar layer) | Cal, Dol, Mag | Cal |

| MIN5 | Pit | P4b | Mortar/Limestone | 10.1 | 84.8 | microcrystalline calcite (in limestone), cocciopesto (in mortar layer) | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN12 | Cistern | C1 | Cocciopesto | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Qtz, Cal, Dol, Arg, Fsp, Bt | Cal |

| MIN11-2 | Cistern | C1 | Mortar | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN11-3 | Cistern | C2 | Cocciopesto | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN11-1 | Cistern | C3 | Limestone/Mortar | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Qtz, Cal, Dol, Fsp, Bt | Cal |

| MIN13 | House-fort | H | Mortar | 28.2 | 66.1 | brown lithic not identified, fibrous mineral (gypsum), quartz, mafic minerals (?) | Qtz, Dol | Bas, Anh, Mgs |

| Sample | Groups | Aggregate | ρR | ρB | ΦO He | ΦO H2O | ΦC H2O | ICW | SI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (g/cm3) | (g/cm3) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | ||

| MIN 2-1 | Group P1 | 28 | 2.57 | 1.13 | 56.0 | 50.9 | 5.0 | 45.0 | 91.0 |

| MIN 2-2 | 30 | 2.61 | 1.04 | 60.0 | 59.3 | 0.7 | 56.7 | 98.8 | |

| MIN 7-1 | 27 | 2.69 | 1.13 | 57.9 | 52.8 | 5.0 | 46.5 | 91.3 | |

| MIN 7-2 | 32 | 2.59 | 1.23 | 52.5 | 40.6 | 11.9 | 33.0 | 77.2 | |

| MIN 7-3 | 29 | 2.55 | 1.16 | 54.6 | 47.6 | 7.0 | 41.1 | 87.1 | |

| MIN 7-4 | 31 | 2.66 | 1.12 | 57.9 | 50.0 | 8.0 | 44.6 | 86.3 | |

| MIN 7-5 | 28 | 2.64 | 1.17 | 55.7 | 52.5 | 3.2 | 44.9 | 94.3 | |

| MIN 3-1 | Group P2a | 37 | 2.66 | 1.39 | 47.5 | 46.8 | 0.7 | 33.5 | 98.5 |

| MIN 4-1 | 36 | 2.68 | 1.38 | 48.5 | 45.6 | 3.0 | 32.9 | 93.9 | |

| MIN 4-2 | 34 | 2.68 | 1.41 | 47.3 | 46.7 | 0.6 | 33.0 | 98.7 | |

| MIN 4-3 | 38 | 2.67 | 1.49 | 44.3 | 35.3 | 9.0 | 23.7 | 79.6 | |

| MIN 1-1 | Group P2b | 16 | 2.51 | 1.45 | 42.1 | 37.4 | 4.7 | 25.7 | 88.9 |

| MIN 1-2 | 17 | 2.63 | 1.37 | 48.0 | 47.0 | 0.9 | 34.4 | 98.0 | |

| MIN 1-3 | 20 | 2.62 | 1.45 | 44.7 | 43.8 | 0.9 | 30.2 | 97.9 | |

| MIN 1-4 | 16 | 2.64 | 1.44 | 45.4 | 42.4 | 3.0 | 29.4 | 93.4 | |

| MIN 6-1 | Group P3 | 5 | 2.64 | 1.10 | 58.3 | 55.5 | 2.8 | 50.3 | 95.2 |

| MIN 6-2 | 7 | 2.62 | 1.06 | 59.6 | 56.7 | 2.8 | 53.5 | 95.2 | |

| MIN 8-1 | 5 | 2.63 | 1.45 | 44.9 | 40.3 | 4.6 | 27.8 | 89.7 | |

| MIN 8-2 | 7 | 2.66 | 1.40 | 47.3 | 35.3 | 11.9 | 25.1 | 74.8 | |

| MIN 8-3 | 6 | 2.67 | 1.47 | 44.8 | 38.6 | 6.3 | 26.1 | 86.0 | |

| MIN 9-1 | Group P4a | n.d. | 2.69 | 1.26 | 53.2 | 44.8 | 8.3 | 35.5 | 84.3 |

| MIN 10-1 | 2.70 | 1.53 | 43.2 | 38.0 | 5.2 | 24.8 | 87.9 | ||

| MIN 5-1 | Group P4b | n.d. | 2.71 | 2.09 | 23.0 | 18.3 | 4.7 | 8.8 | 79.6 |

| MIN 5-2 | 2.70 | 2.11 | 21.8 | 19.0 | 2.9 | 9.0 | 86.9 | ||

| MIN 11-2 | Group C1 | 33 | 2.61 | 1.16 | 55.6 | 52.5 | 3.0 | 45.2 | 94.6 |

| MIN 11-5 | 31 | 2.68 | 1.31 | 51.0 | 42.3 | 8.7 | 32.1 | 82.9 | |

| MIN 12-1 | 30 | 2.69 | 1.85 | 31.3 | 30.7 | 0.6 | 16.6 | 98.1 | |

| MIN 11-3 | Group C2 | n.d. | 2.41 | 1.19 | 50.6 | 25.2 | 25.5 | 21.1 | 49.7 |

| MIN 11-4 | 2.47 | 1.29 | 47.6 | 22.1 | 25.5 | 17.0 | 46.4 | ||

| MIN 11-1 | Group C3 | n.d. | 2.69 | 1.23 | 54.2 | 36.4 | 17.8 | 29.5 | 67.1 |

| MIN 13-1 | Group H | 28 | 2.75 | 1.42 | 48.4 | 39.2 | 9.2 | 27.6 | 81.0 |

| MIN 13-2 | 29 | 2.76 | 1.47 | 46.8 | 23.6 | 23.2 | 16.0 | 50.4 |

| Sample | Groups | P | W | H | De2 | De | Is | F | Is(50) | RC | RT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm2) | (mm) | (N/mm2) | / | (MPa) | (MPa) | (kg/cm2) | (MPa) | (kg/cm2) | ||

| MIN 2-1 | Group P1 | 0.15 | 1.40 | 1.25 | 2.23 | 1.49 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 4.59 | 0.02 | 0.18 |

| MIN 2-2 | 0.15 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.40 | 1.18 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.65 | 6.58 | 0.02 | 0.25 | |

| MIN 7-1 | 0.05 | 1.70 | 1.30 | 2.81 | 1.68 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.0039 | 0.13 | 1.28 | 0.0048 | 0.05 | |

| MIN 7-2 | 0.05 | 1.70 | 1.15 | 2.49 | 1.58 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.0042 | 0.14 | 1.41 | 0.0053 | 0.05 | |

| MIN 7-3 | n.d. | 1.50 | 0.90 | 1.72 | 1.31 | n.d. | 0.19 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 7-4 | n.d. | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.91 | 1.38 | n.d. | 0.20 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 7-5 | n.d. | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.80 | n.d. | 0.16 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 3-1 | Group P2a | n.d. | 1.60 | 0.90 | 1.83 | 1.35 | n.d. | 0.20 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN 4-1 | n.d. | 1.50 | 0.80 | 1.53 | 1.24 | n.d. | 0.19 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 4-2 | n.d. | 1.60 | 1.00 | 2.04 | 1.43 | n.d. | 0.20 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 4-3 | n.d. | 1.40 | 1.30 | 2.32 | 1.52 | n.d. | 0.21 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 1-1 | Group P2b | n.d. | 1.20 | 0.90 | 1.38 | 1.17 | n.d. | 0.18 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN 1-2 | n.d. | 1.40 | 1.00 | 1.78 | 1.34 | n.d. | 0.20 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 1-3 | n.d. | 1.60 | 1.40 | 2.85 | 1.69 | n.d. | 0.22 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 1-4 | n.d. | 1.50 | 1.30 | 2.48 | 1.58 | n.d. | 0.21 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 6-1 | Group P3 | n.d. | 1.70 | 0.90 | 1.95 | 1.40 | n.d. | 0.20 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN 6-2 | n.d. | 1.70 | 1.20 | 2.60 | 1.61 | n.d. | 0.21 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 8-1 | 0.10 | 1.70 | 1.50 | 3.25 | 1.80 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 2.29 | 0.01 | 0.09 | |

| MIN 8-2 | 0.45 | 1.60 | 1.50 | 3.06 | 1.75 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 1.06 | 10.79 | 0.04 | 0.42 | |

| MIN 8-3 | 0.25 | 1.50 | 1.35 | 2.58 | 1.61 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.67 | 6.84 | 0.03 | 0.26 | |

| MIN 9-1 | Group P4a | 0.40 | 1.15 | 1.10 | 1.61 | 1.27 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 1.55 | 15.76 | 0.06 | 0.61 |

| MIN 10-1 | 0.80 | 1.60 | 1.00 | 2.04 | 1.43 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 2.58 | 26.27 | 0.10 | 1.01 | |

| MIN 5-1 | Group P4b | 0.90 | 1.30 | 0.90 | 1.49 | 1.22 | 0.60 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 3.69 | 37.66 | 0.14 | 1.45 |

| MIN 5-2 | 0.15 | 0.90 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 1.92 | 19.56 | 0.07 | 0.75 | |

| MIN 11-2 | Group C1 | n.d. | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.96 | n.d. | 0.17 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN 11-5 | n.d. | 0.70 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.60 | n.d. | 0.14 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 12-1 | n.d. | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.80 | n.d. | 0.16 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| MIN 11-3 | Group C2 | n.d. | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.78 | n.d. | 0.15 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN 11-4 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.55 | 5.62 | 0.02 | 0.22 | |

| MIN 11-1 | Group C3 | n.d. | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.48 | n.d. | 0.12 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| MIN 13-1 | Group H | 0.15 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 1.12 | 11.43 | 0.04 | 0.44 |

| MIN 13-2 | 0.15 | 0.80 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 1.86 | 19.01 | 0.07 | 0.73 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Columbu, S.; Depalmas, A.; Brodu, G.; Gallello, G.; Fancello, D. Mining Exploration, Raw Materials and Production Technologies of Mortars in the Different Civilization Periods in Menorca Island (Spain). Minerals 2022, 12, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12020218

Columbu S, Depalmas A, Brodu G, Gallello G, Fancello D. Mining Exploration, Raw Materials and Production Technologies of Mortars in the Different Civilization Periods in Menorca Island (Spain). Minerals. 2022; 12(2):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12020218

Chicago/Turabian StyleColumbu, Stefano, Anna Depalmas, Giovanni Brodu, Gianni Gallello, and Dario Fancello. 2022. "Mining Exploration, Raw Materials and Production Technologies of Mortars in the Different Civilization Periods in Menorca Island (Spain)" Minerals 12, no. 2: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12020218

APA StyleColumbu, S., Depalmas, A., Brodu, G., Gallello, G., & Fancello, D. (2022). Mining Exploration, Raw Materials and Production Technologies of Mortars in the Different Civilization Periods in Menorca Island (Spain). Minerals, 12(2), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/min12020218