A Novel Framework for Assessing Facial Attractiveness Based on Facial Proportions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Proposed Framework

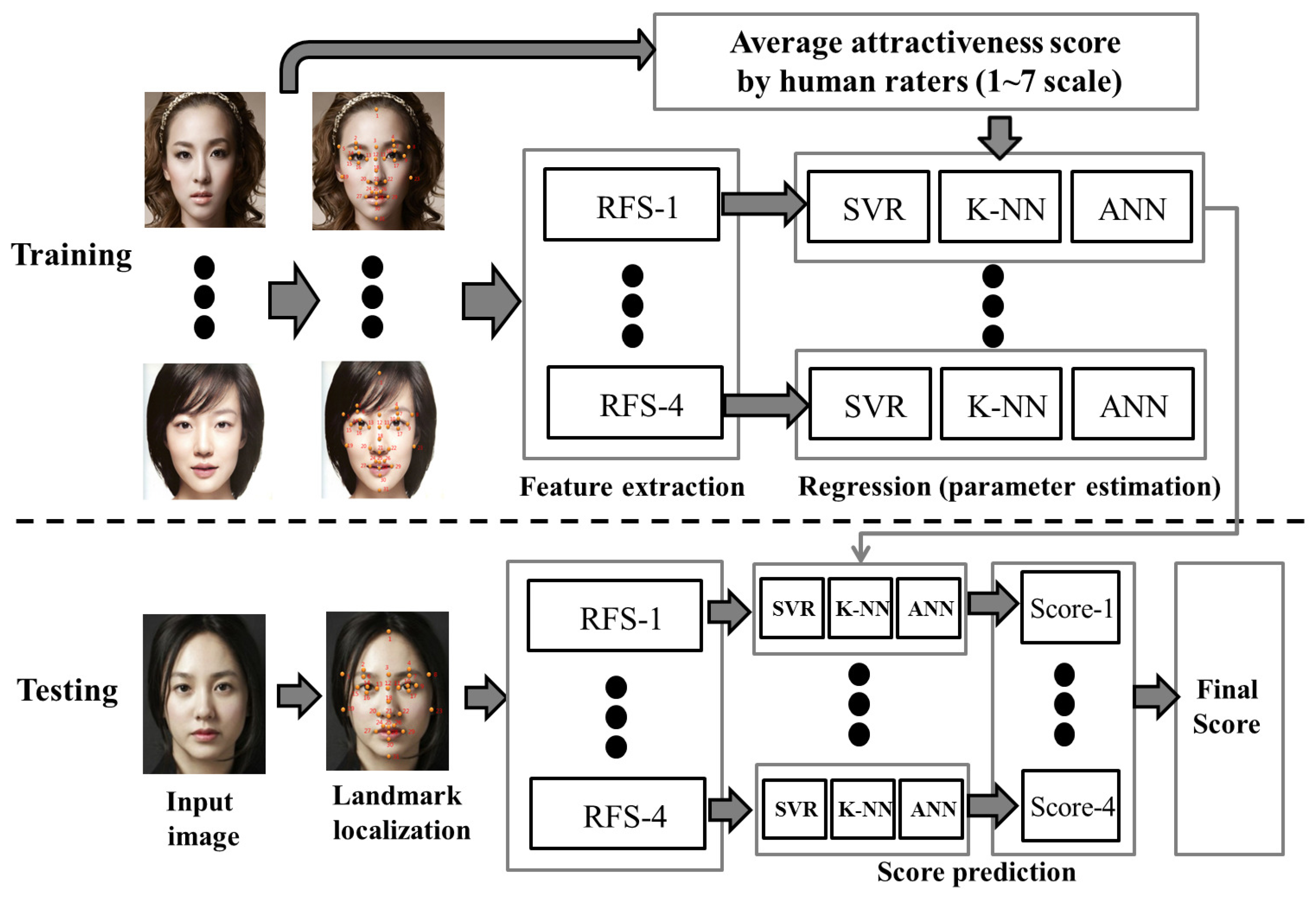

3.1. Training Procedure

3.1.1. Facial Landmark Localization

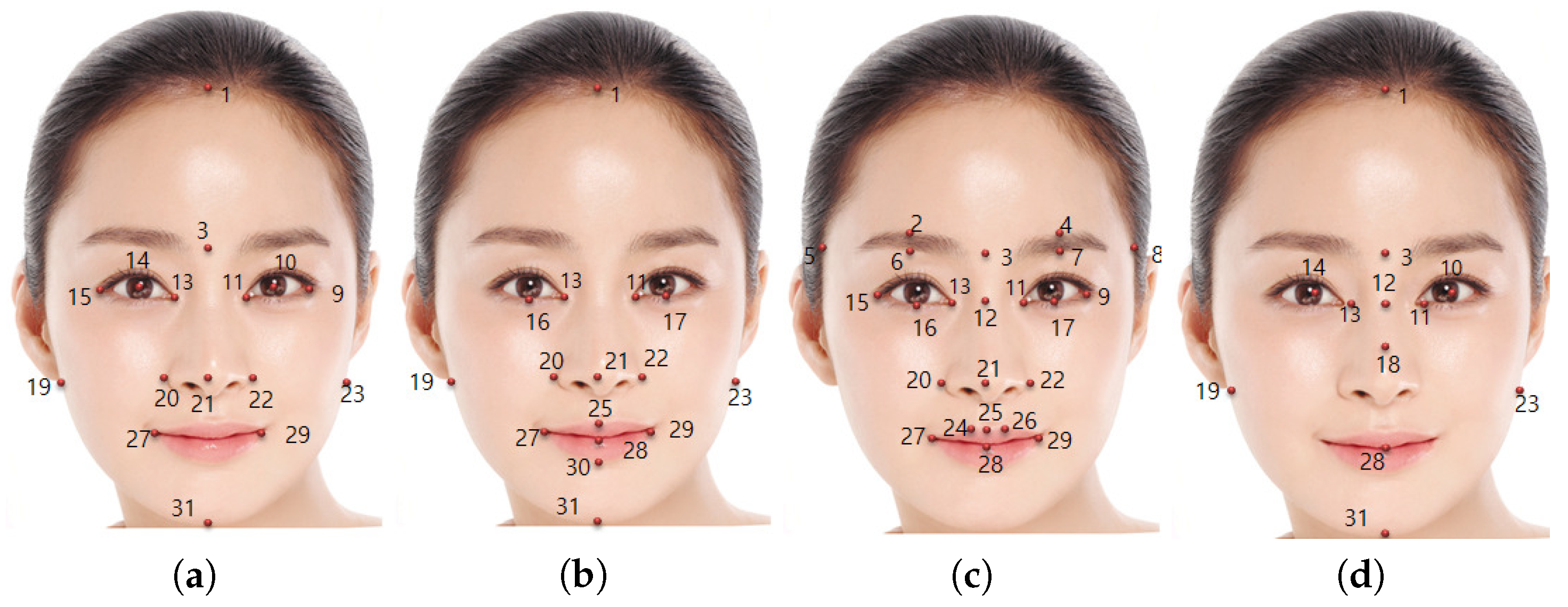

3.1.2. Ratio Feature Set (RFS) Extraction

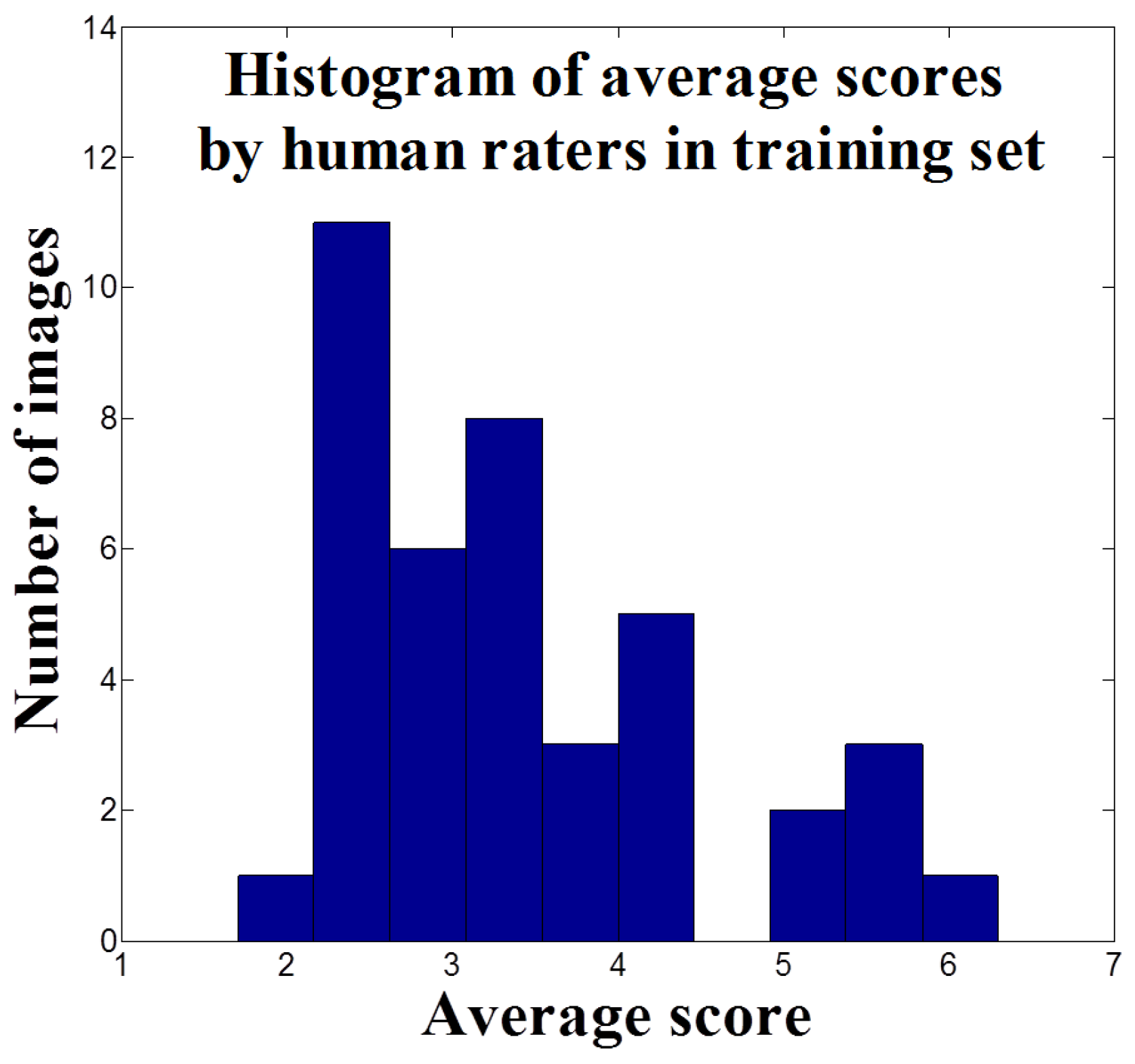

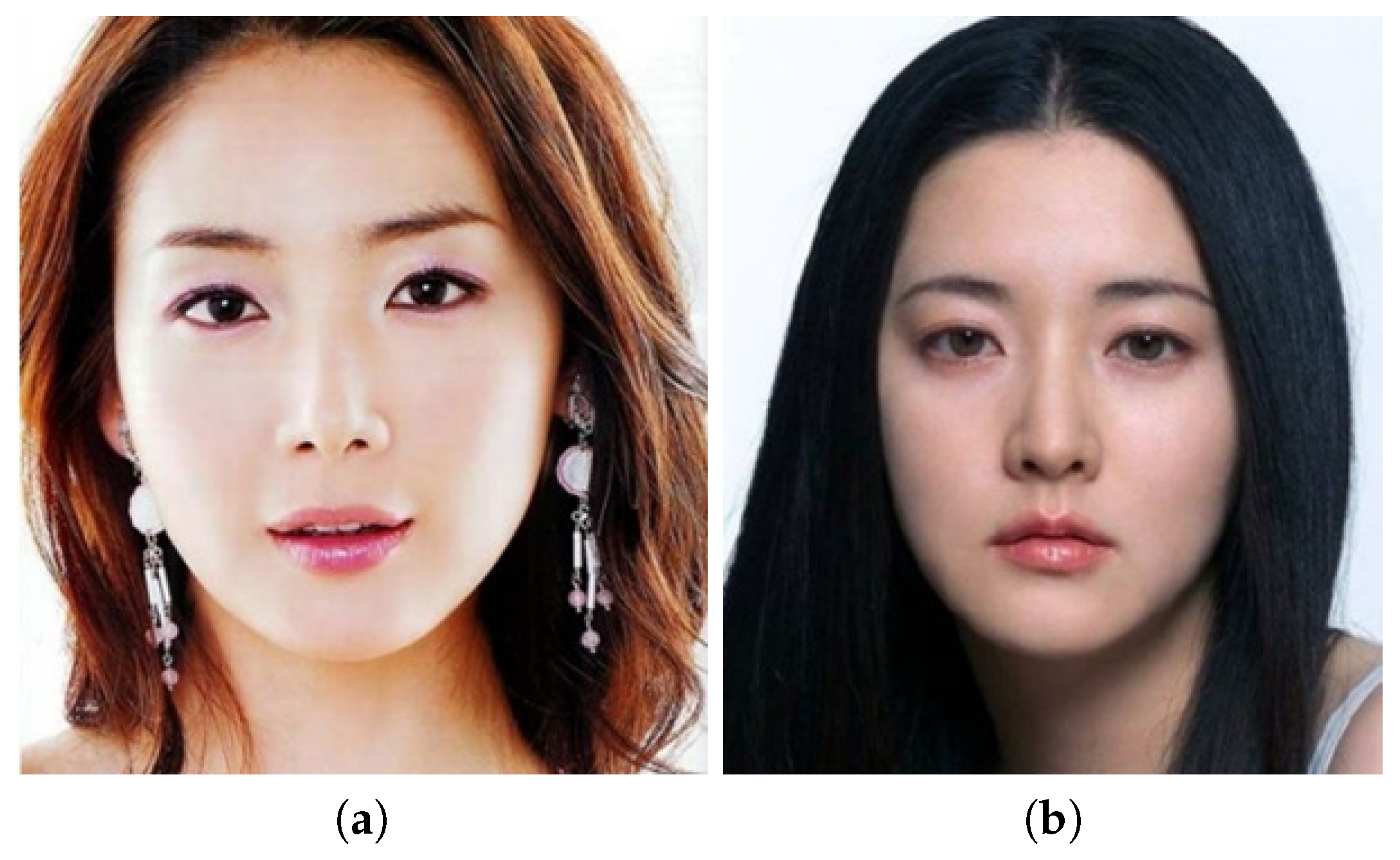

3.1.3. Dataset and Facial Attractiveness Rating by Humans

3.1.4. Predictor Construction

3.2. Testing Procedure

4. Experimental Results

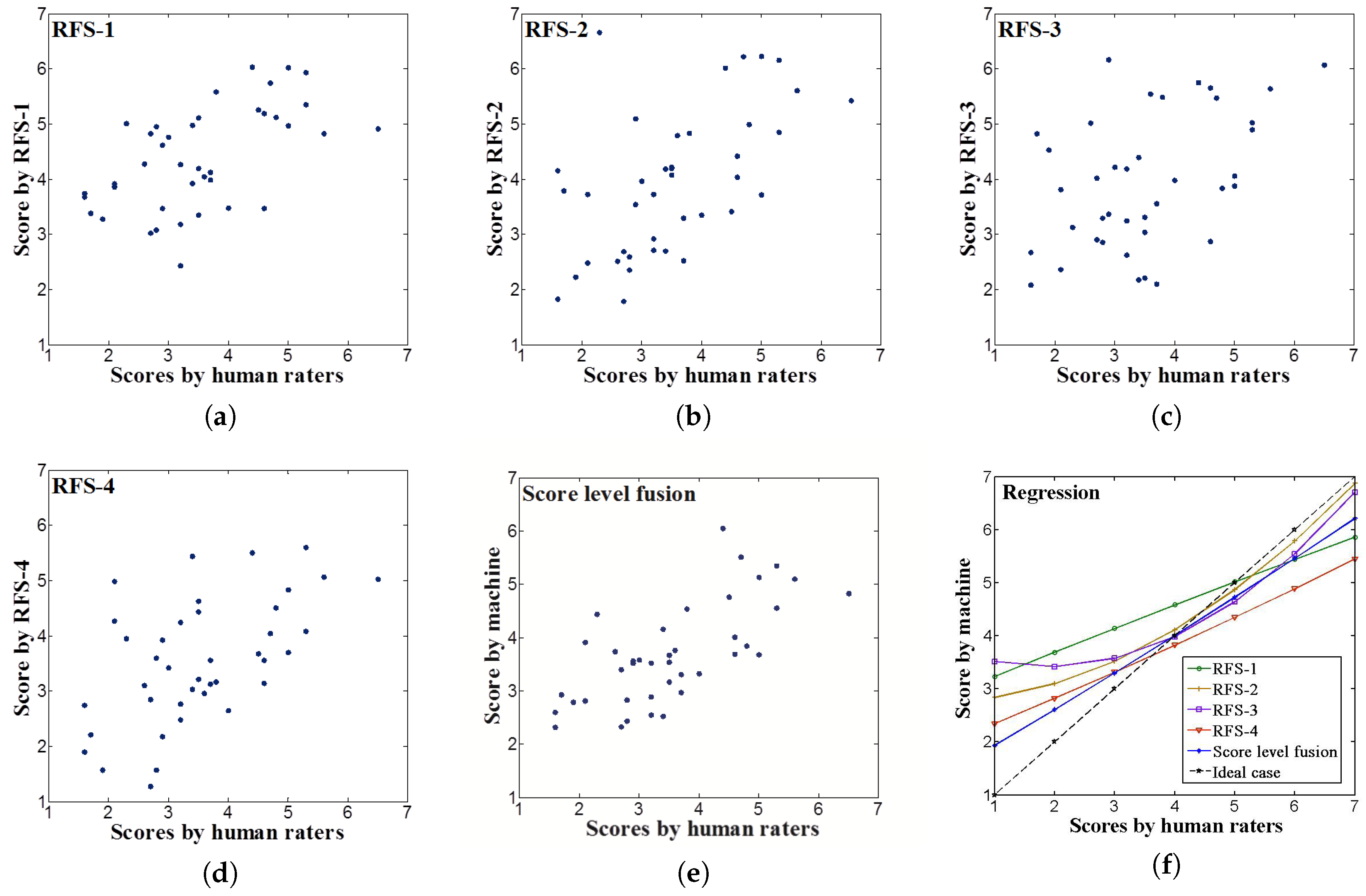

4.1. Comparison with Human-Level Performance

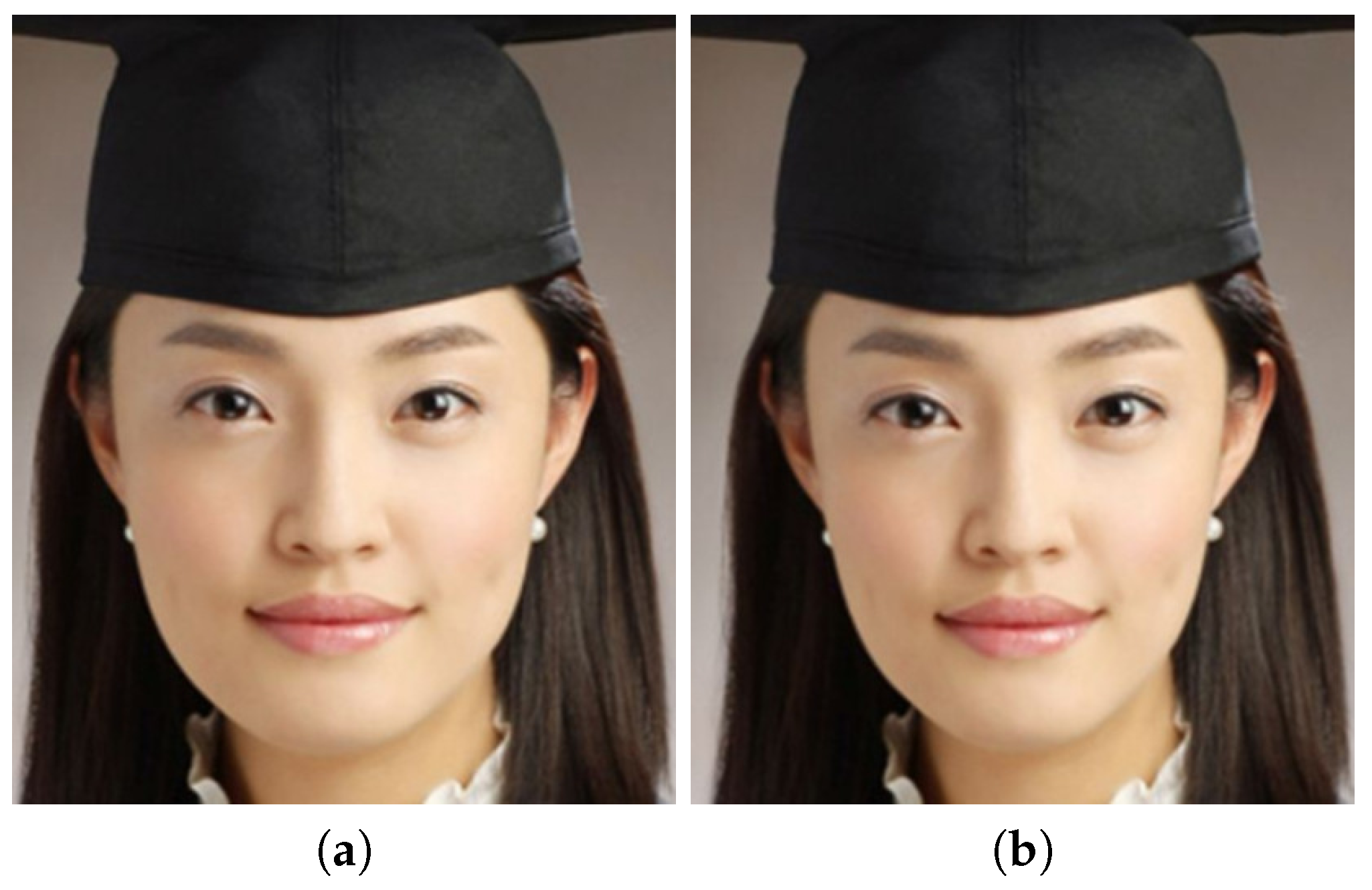

4.2. Applications

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhodes, G. The evolutionary psychology of facial beauty. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, C.P.; Todorov, A. A statistical model of facial attractiveness. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, P.A.; Galli, S.K.D. Modern concepts of beauty. Plast. Surg. Nurs. 2009, 29, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrett, D.I.; May, K.A.; Yoshikawa, S. Facial shape and judgements of female attractiveness. Nature 1994, 368, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winston, J.S.; O’Doherty, J.; Kilner, J.M.; Perrett, D.I.; Dolan, R.J. Brain systems for assessing facial attractiveness. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, A.J.; Kalakanis, L.; Langlois, J.H. Infant preferences for attractive faces: A cognitive explanation. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlois, J.H.; Roggman, L.A. Attractive faces are only average. Psychol. Sci. 1990, 1, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, G.; Proffitt, F.; Grady, J.M.; Sumich, A. Facial symmetry and the perception of beauty. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 1998, 5, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, B.; Grammer, K.; Thornhill, R. Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness in relation to skin texture and color. J. Comp. Psychol. 2001, 115, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.L.; Russell, R.; Ward, R. Cosmetics Alter Biologically-Based Factors of Beauty: Evidence from Facial Contrast. Evol. Psychol. 2015, 13, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagian, A.; Dror, G.; Leyvand, T.; Cohen-Or, D.; Ruppin, E. A humanlike predictor of facial attractiveness. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3 December 2007; pp. 649–656. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.L. The influence of shape and colour cue classes on facial health perception. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, L.G.; Hreczko, T.A.; Kolar, J.C.; Munro, I.R. Vertical and horizontal proportions of the face in young adult north american caucasians: A revision of neoclassical canons. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1985, 75, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narain, D.L. The Golden Ratio. Availabel online: http://cuip.uchicago.edu/~dlnarain/golden/ (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Jefferson, Y. Facial beauty: Establishing a universal standard. Int. J. Orthod. 2004, 15, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Galton, F. Composite portraits, made by combining those of many different persons into a single resultant figure. J. Anthropol. Inst. Greatt. Br. Irel. 1879, 8, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.A.; Michael, R.C. Averaged faces are attractive, but very attractive faces are not average. Psychol. Sci. 1991, 2, 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Grammer, K.; Thornhill, R. Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: The role of symmetry and averageness. J. Comp. Psychol. 1994, 108, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrett, D.I.; Lee, K.J.; Penton-Voak, I.; Rowland, D.; Yoshikawa, S.; Burt, D.M.; Henzi, S.P.; Castlesm, D.L.; Akamatsu, S. Effects of sexual dimorphism on facial attractiveness. Nature 1998, 394, 884–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheib, J.E.; Gangestad, S.W.; Thornhill, R. Facial attractiveness, symmetry and cues of good genes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1999, 266, 1913–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronstad, P.M.; Russell, R. Computational models of facial attractiveness judgments. Perception 2008, 37, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.C.; Little, A.C.; Burt, D.M.; Perrett, D.I. When facial attractiveness is only skin deep. Perception 2004, 33, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarabi, P.; Hughes, D.; Mohajer, K.; Emami, M. The automatic measurement of facial beauty. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Tucson, AZ, USA, 7–10 October 2001; Volume 4, pp. 2644–2647. [Google Scholar]

- Gunes, H.; Piccardi, M. Assessing facial beauty through proportion analysis by image processing and supervised learning. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 1184–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenthal, Y.; Dror, G.; Ruppin, E. Facial attractiveness: Beauty and the machine. Neural Comput. 2006, 18, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, K.; Marx, D.; Samal, A. Computation of a face attractiveness index based on neoclassical canons, symmetry, and golden ratio. Pattern Recogn. 2008, 41, 2710–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyvand, T.; Cohen-Or, D.; Dror, G.; Lischinski, D. Data-driven enhancement of facial attractiveness. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 11–15 August 2008; pp. 38.1–38.9. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, A.J.; Price, T.; Vetter, T.; Bartlett, J.C.; Blanz, V. 3D shape and 2D surface textures of human faces: The role of “averages” in attractiveness and age. Image. Vis. Comput. 1999, 18, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, B.; Grammer, K.; Matts, P.J. Visible skin color distribution plays a role in the perception of age, attractiveness, and health in female faces. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2006, 27, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.S.; Bayome, M.; Park, J.H.; Park, K.H.; Moon, H.B.; Kook, Y.A. A three-dimensional photogrammetric analysis of the facial esthetics of the Miss Korea pageant contestants. Korean J. Orthod. 2017, 47, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezzetti, E.; Marcolin, F.; Tornincasa, S.; Ulrich, L.; Dagnes, N. 3D geometry-based automatic landmark localization in presence of facial occlusions. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolin, F.; Vezzetti, E. Novel descriptors for geometrical 3D face analysis. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 13805–13834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Jin, X.; Zeng, W. Enhancing the Symmetry and Proportion of 3D Face Geometry. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2012, 18, 1704–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cootes, T.; Taylor, C.; Cooper, D.; Graham, J. Active shape models—Their traning and application. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 1995, 61, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milborrow, S.; Nicolls, F. Locating facial features with an extended active shape model. In Proceedings of the ECCV, Marseille, France, 12–18 October 2008; pp. 504–513. [Google Scholar]

- Torsello, F.; Mirigliani, L.; D’Alessio, R.; Deli, R. Do the neoclassical canons still describe the beauty of faces? An anthropometric study on 50 Caucasian models. Prog. Orthod. 2010, 11, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mommaerts, M.Y.; Moerenhout, B.A. Ideal proportions in full face front view, contemporary versus antique. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2011, 39, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naini, F.B.; Moss, J.P.; Gill, D.S. The enigma of facial beauty: Esthetics, proportions, deformity, and controversy. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 2006, 130, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancherz, H.; Knapp, V.; Erbe, C.; Heiss, A.M. Divine proportions in attractive and nonattractive faces. World J. Orthod. 2010, 11, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magne, P.; Gallucci, G.O.; Belser, U.C. Anatomic crown width/length ratios of unworn and worn maxillary teeth in white subjects. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, E.; Brown, R.A.; Richmond, S. Peer assessment of dental attractiveness. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 2006, 130, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.R. Measuring the physical in physical attractiveness: Quasi-experiments on the sociobiology of female facial beauty. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, V.S.; Franklin, M. Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Ethol. Sociobiol. 1993, 14, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etcoff, N.L. Beauty and the beholder. Nature 1994, 368, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Nandakumar, K.; Ross, A. Score normalization in multimodal biometric systems. Pattern Recogn. 2005, 38, 2270–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Reference | Feature(s) | Measurement(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D | Aarabi et al. [23] | Facial ratio | 8-element vector of ratios |

| Gunes and Piccardi [24] | Facial ratio | Golden ratio, facial thirds | |

| Schmid et al. [26] | Facial ratio | Golden ratio, symmetry, canons | |

| Perrett et al. [4] | Facial landmarks | Averageness | |

| Bronstad and Russell [21] | Landmark distance, pixels | Symmetry, averageness, sexual dimorphism | |

| Kagian et al. [11] | Landmark distance, skin | Geometric features | |

| Jones [12] | Landmark distance, skin | Symmetry, averageness, femininity, skin tones | |

| Galton et al. [16] | Shape, pixels | Averageness | |

| Eisenthal et al. [25] | Shape, hair color | Symmetry | |

| Jones et al. [22] | Skin | Skin patches | |

| Fink et al. [9] | Skin | Skin colors, texture | |

| 3D | Fink et al. [29] | Skin | Skin colors |

| O’Toole et al. [28] | Shape, texture | Shape, texture | |

| Liao et al. [33] | Facial ratio | Golden ratio, symmetry, canons |

| RFS-1: Neoclassical Canons | RFS-2: Golden Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Description (Distance/Distance) | Ratio vector | Description (Distance/Distance) | Ratio vector |

| facetop-eyebrows/eyebrows-nose | dist(1,3)/dist(3,21) | under eyes/interocular | dist(16,17)/dist(13,11) |

| eyebrows-nose/nose-jaw | dist(3,21)/dist(21,31) | under eyes/nose width | dist(16,17)/dist(20,22) |

| facetop-eyebrows/nose-jaw | dist(1,3)/dist(21,31) | mouth width/interocular | dist(27,29)/dist(13,11) |

| interocular/nose width | dist(11,13)/dist(20,22) | upper lip-aw/interocular | dist(25,31)/dist(13,11) |

| interocular/pupil-outer eye(right) | dist(11,13)/dist(13,15) | upper lip-jaw/nose width | dist(25,31)/dist(20,22) |

| interocular/pupil-outer eye(left) | dist(11,13)/dist(9,11) | interocular/lip height | dist(13,11)/dist(25,30) |

| right eye width/left eye width | dist(13,15)/dist(9,11) | nose width/interocular | dist(20,22)/dist(13,11) |

| mouth width/(1.5× nose width) | dist(27,29)/(1.5× dist(20,22)) | nose width/upper lip height | dist(20,22)/dist(25,28) |

| face width/(4× nose width) | dist(19,23)/(4× dist(20,22)) | interocular/nose-mouth | dist(13,11)/dist(21,28) |

| RFS-3: Symmetry | lip height/nose-mouth | dist(25,30)/dist(21,28) | |

| Descriptions(Distance/Distance) | Ratio vector | face height/face width | dist(1,31)/dist(19,23) |

| Eyebrows | dist(2,3)/dist(4,3) | nose-jaw/mouth-jaw | dist(21,31)/ dist(28,31) |

| dist(6,3)/dist(7,3) | nose width/nose-mouth | dist(20,22)/dist(21,28) | |

| Eyes | dist(6,3)/dist(7,3) | mouth width/nose width | dist(27,29)/dist(20,22) |

| dist(11,12)/dist(13,12) | RFS-4: 8-Ratio Vectors | ||

| dist(16,12)/dist(17,12) | Descriptions (Distance/Distance) | Ratio vector | |

| Nose | dist(20,21)/dist(22,21) | interpupillary/eyes-mouth | dist(10,14)/dist(12,28) |

| interpupillary/face width | dist(10,14)/dist(19,23) | ||

| Mouth | dist(24,21)/dist(26,25) | eyes-mouth/face height | dist(12,28)/dist(1,31)) |

| right pupil-mouth/ left pupil-mouth | dist(14,28)/dist(10,28) | ||

| dist(27,28)/dist(27,29) | facetop-eyebrows/eyes-jaw | dist(1,3)/dist(12,31) | |

| nose-mouth/mouth-jaw | dist(12,28)/dist(1,31) | ||

| Face | dist(5,3)/dist(8,3) | eyes center-nose/nose-jaw | dist(12,18)/dist(18,31) |

| eye center-face center/face width | dist(mid(13,11),12)/dist(19,23) | ||

| Predictor | Parameter | Range |

|---|---|---|

| RBF-SVR | 0.1∼10 | |

| C | 1∼10 | |

| 0.1∼0.9 | ||

| K-NN | K | 1∼30 |

| ANN | No. hidden layer | 1∼2 |

| No. neurons | 3∼20 |

| Feature/Predictor | SVR | KNN | ANN | SVR + KNN | ANN + KNN | SVR + ANN | SVR + ANN + KNN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFS-1 | 0.459 | 0.376 | 0.504 | 0.471 | 0.493 | 0.525 | 0.567 |

| RFS-2 | 0.457 | 0.486 | 0.544 | 0.492 | 0.554 | 0.541 | 0.569 |

| RFS-3 | 0.446 | 0.445 | 0.436 | 0.449 | 0.441 | 0.453 | 0.466 |

| RFS-4 | 0.511 | 0.484 | 0.536 | 0.521 | 0.526 | 0.536 | 0.553 |

| Feature Set | Pearson Correlation | MSE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFS-1 | 0.567 | 0.206 | 0.282 |

| RFS-2 | 0.569 | 0.193 | 0.301 |

| RFS-3 | 0.466 | 0.220 | 0.197 |

| RFS-4 | 0.553 | 0.170 | 0.241 |

| Score fusion | 0.689 | 0.151 | 0.449 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, Y.-J.; Nam, G.P.; Choi, H.; Cho, J.; Kim, I.-J. A Novel Framework for Assessing Facial Attractiveness Based on Facial Proportions. Symmetry 2017, 9, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9120294

Hong Y-J, Nam GP, Choi H, Cho J, Kim I-J. A Novel Framework for Assessing Facial Attractiveness Based on Facial Proportions. Symmetry. 2017; 9(12):294. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9120294

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Yu-Jin, Gi Pyo Nam, Heeseung Choi, Junghyun Cho, and Ig-Jae Kim. 2017. "A Novel Framework for Assessing Facial Attractiveness Based on Facial Proportions" Symmetry 9, no. 12: 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9120294

APA StyleHong, Y.-J., Nam, G. P., Choi, H., Cho, J., & Kim, I.-J. (2017). A Novel Framework for Assessing Facial Attractiveness Based on Facial Proportions. Symmetry, 9(12), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9120294