1. Introduction

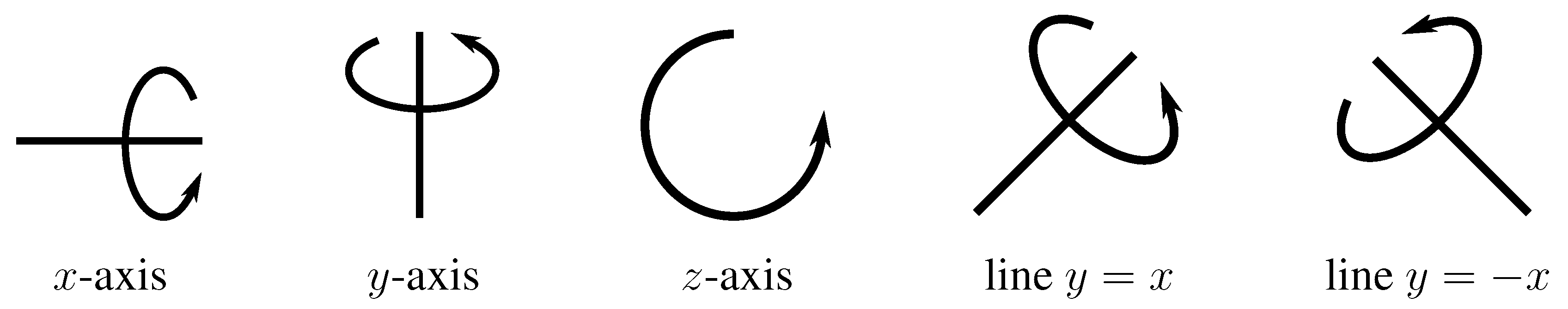

The symmetry group of a link

L is defined to be the mapping class group

(or

) of the pair

. The study of this symmetry group is a classical topic in knot theory, and these groups have now been computed for prime knots and links in several ways. Kodama and Sakuma [

1] used a method in Bonahon and Siebenmann [

2] to compute these groups for all but three of the knots of 10 and fewer crossings in 1992. In the same year, Weeks and Henry used the program SnapPea to compute the symmetry groups for hyperbolic knots and links of 9 and fewer crossings [

3]. These efforts followed earlier tabulations of symmetry groups by Boileau and Zimmermann [

4], who found symmetry groups for non-elliptic Montesinos links with 11 or fewer crossings.

We consider a different group of symmetries of a link

L given by the image of the natural homomorphism

Since these symmetries record an action on

L itself (and only record the orientation of the ambient

), we will call them “intrinsic” symmetries of

L to distinguish them from the standard symmetry group and denote them as

, cf. Definition 4.5. Following Whitten [

5], we denote all possible intrinsic symmetries as

; see Definition 4.1.

Unlike the elements in the Sym group, which may be somewhat difficult to describe explicitly, each of the elements in corresponds to an isotopy of L which may exchange the position of some components, which may reverse the orientation of the ambient space—this mirrors any diagram of L, and which may reverse orientations of some components. Neither the Boileau–Zimmerman or the Henry–Weeks-SnapPea method gives much insight into what those isotopies might look like. In addition, it is worth noting that SnapPea is a large and complicated computer program, and while its results are accurate for the links in our table, it is always worthwhile to have alternate proofs for results that depend essentially on nontrivial computer calculations.

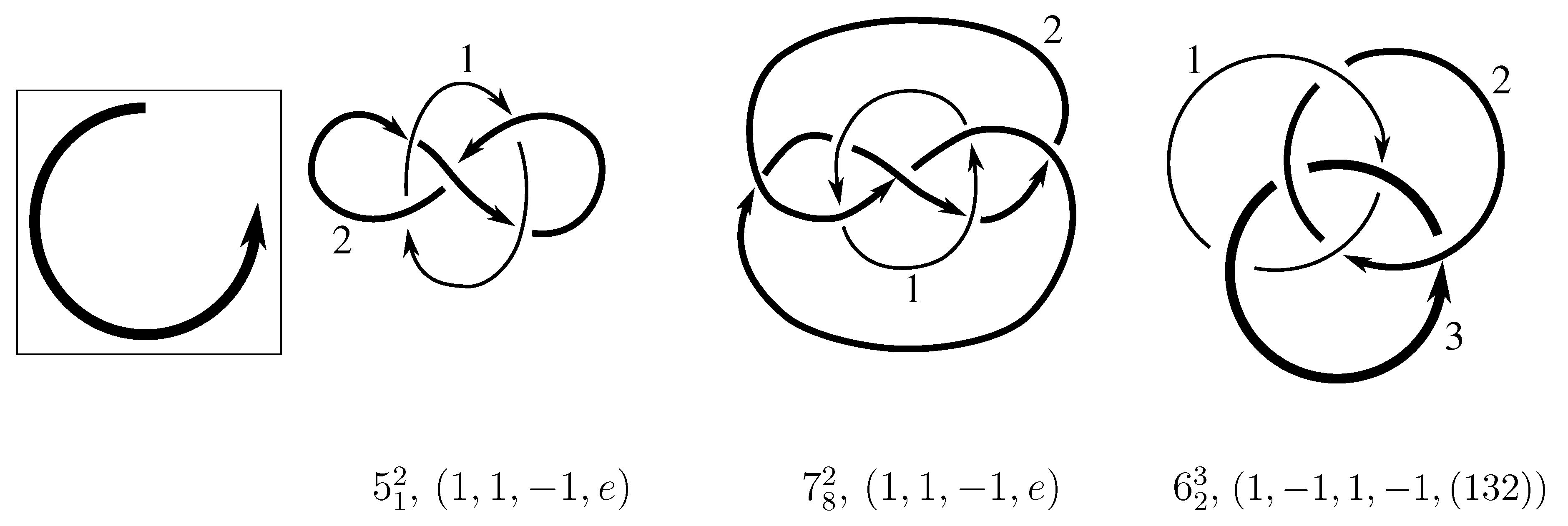

In this spirit, the present paper presents an elementary and explicit derivation of the

groups for all links of 8 and fewer crossings. We rule out certain isotopies using elementary and polynomial invariants to provide an upper bound on the size of

for each link in our table and then present explicit isotopies generating

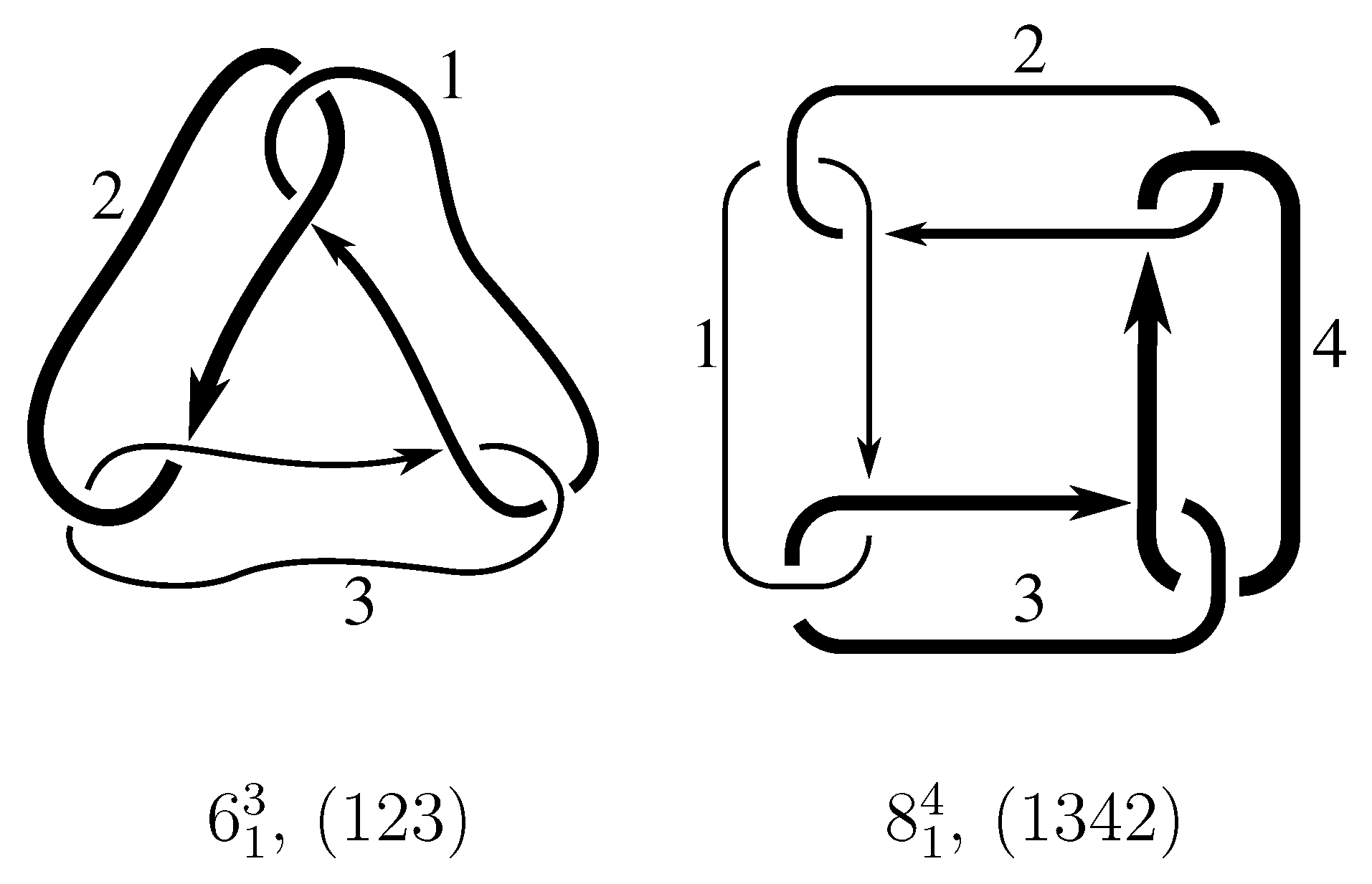

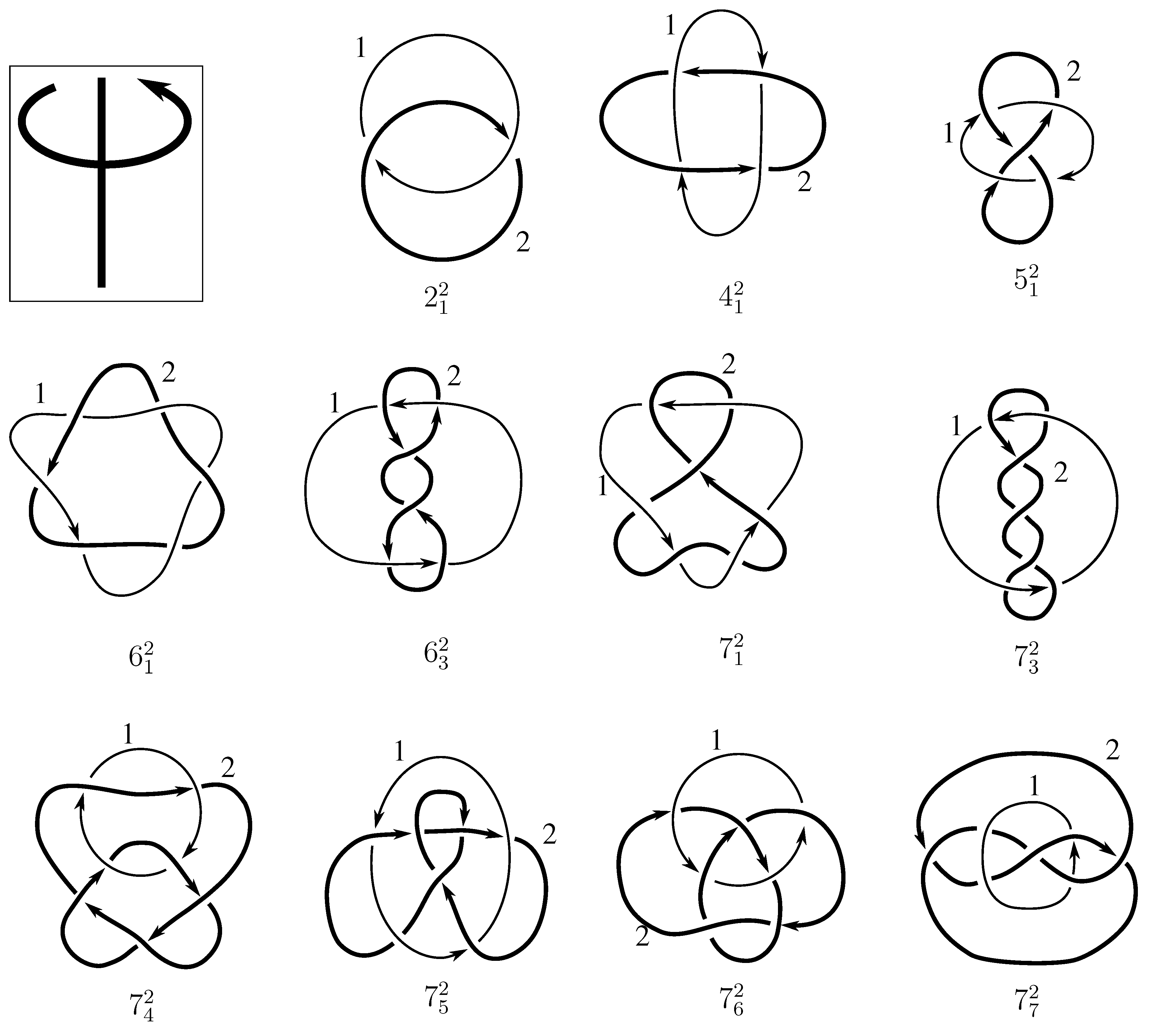

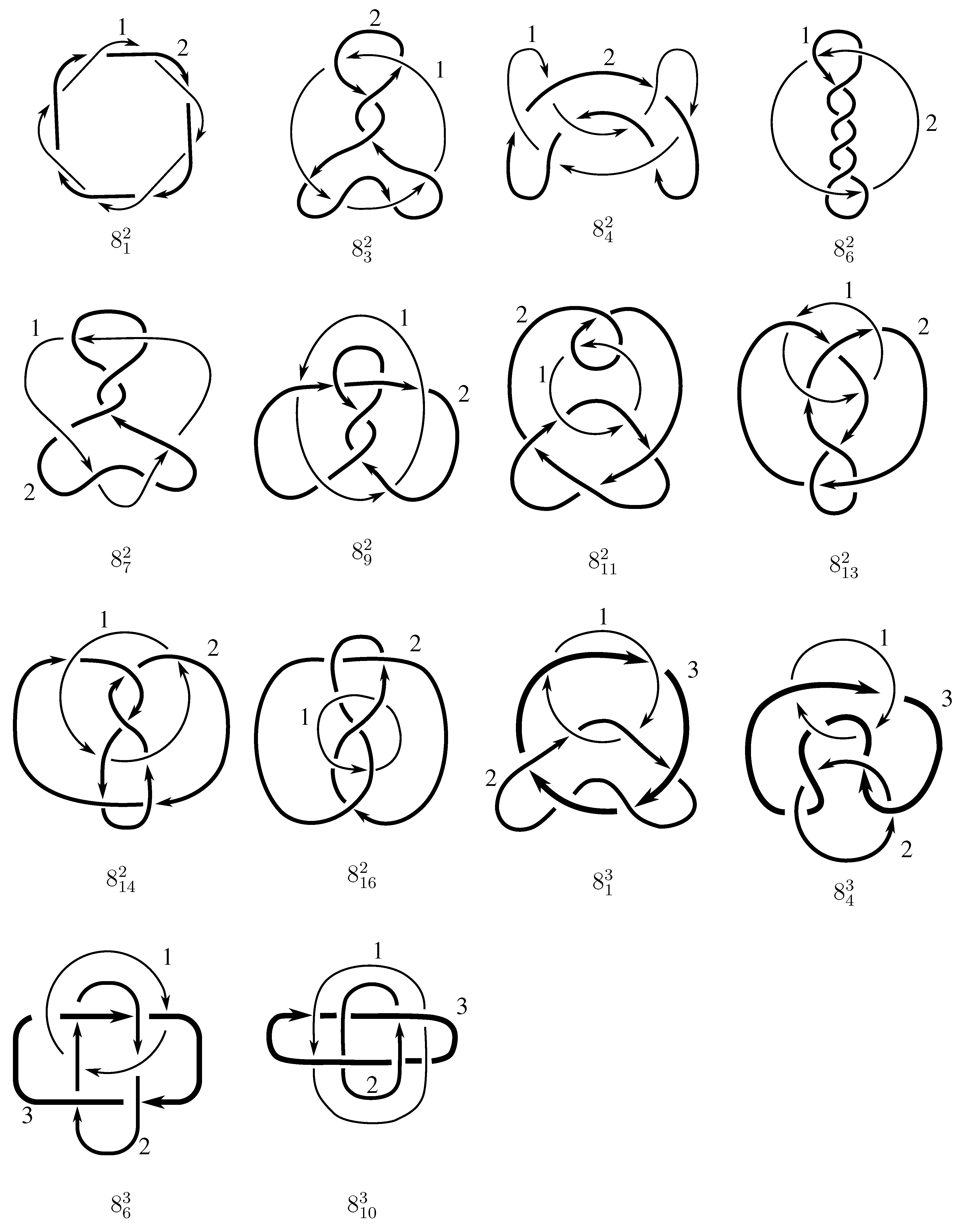

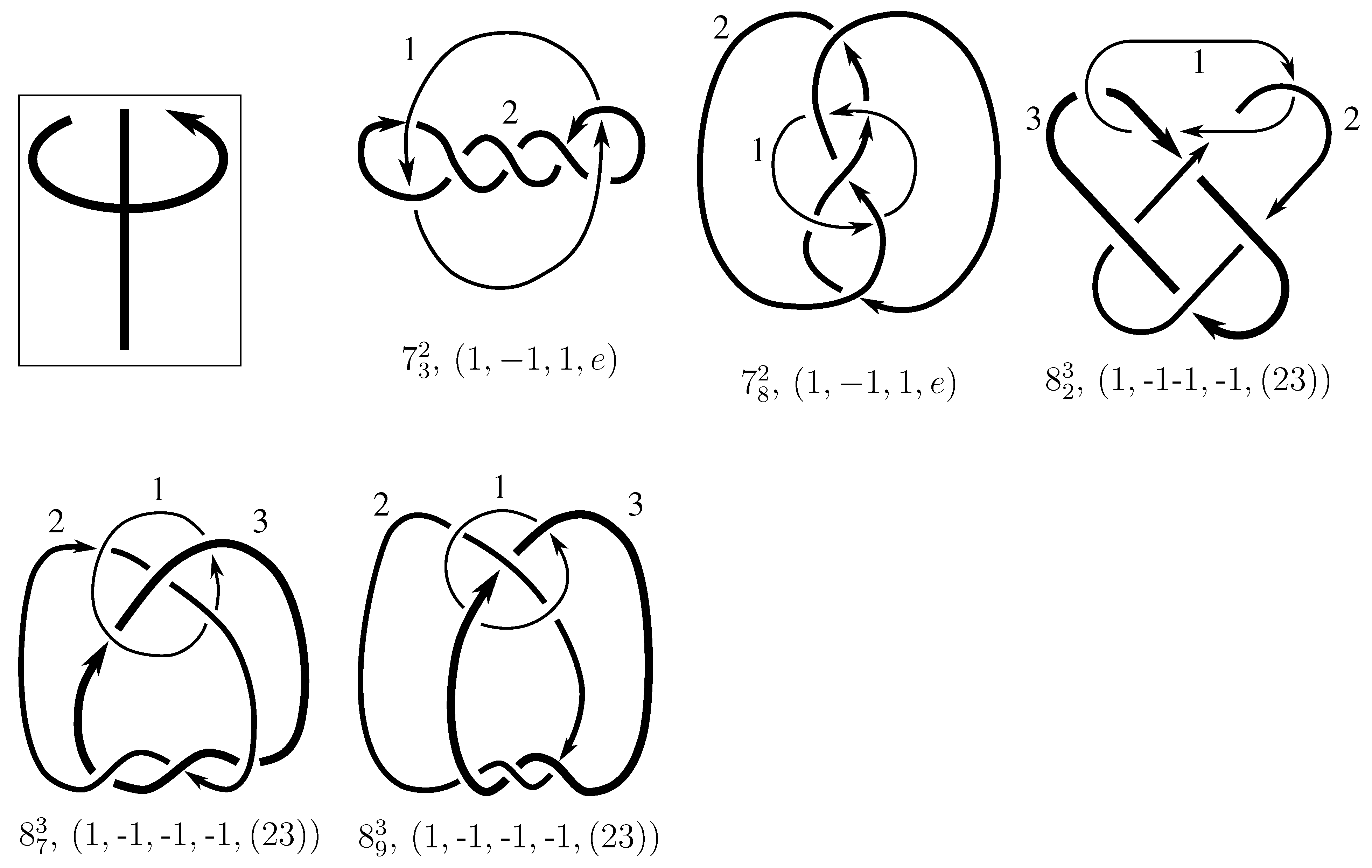

starting with the configurations of the link in Cerf’s table of alternating oriented links [

6] or (for nonalternating links) Doll and Hoste’s table [

7]. For two links in our table,

and

, an additional construction is needed to rule out certain “component exchange” symmetries using satellites and the Jones polynomial. This shows that the polynomial invariants are powerful enough to compute

for these links. For one link in our table,

, even this construction does not rule out all the isotopies outside the symmetry group and we must fall back on the hyperbolic structure of the link to compute the symmetry group. We give the first comprehensive list of

groups that we know of, though Hillman [

8] provides examples of various two-component links (including some split links) with symmetry groups equal to 12 different subgroups of

.

Why are the

groups interesting? First, it is often more natural to consider the restricted group

than the generally larger

. Sakuma [

9] has shown that a knot

K has a finite symmetry group if and only if

K is a hyperbolic knot, a torus knot, or a cable of a torus knot. Thus for many [

10] knots, the group

contains infinitely many elements which act nontrivially on the complement of

L but fix the link itself. We ignore such elements, which lie in the kernel of the natural homomorphism

. In fact, even when

is finite, we give various examples below where

has nontrivial kernel. It is often difficult to describe an element of

in

explicitly, but it is always simple to understand the exact meaning of the statement

.

As an application, if one is interested in classifying knots and links up to oriented, labeled ambient isotopy, it is important to know the symmetry group

for each prime link type

L, since links related by an element in

outside

are not (oriented, labeled) ambient isotopic. The number of different links related by an element of

to a given link of prime link type

L is given by the number of cosets of

in

. If we count these cosets instead of prime link types, the number of actual knots and link types of a given crossing number is actually quite a bit larger than the usual table of prime knot and link types suggests. (See

Table 1.)

Second, seems likely to be eventually relevant in applications. For instance, when studying DNA links, each loop of the link generally has a unique sequence of base pairs which provide an orientation and an unambiguous labeling of each component of the link. In such a case, the question of whether two components in a link can be interchanged may prove to be of real significance.

Last, we are interested in the topic of tabulating composite knots and links. Since the connect sum of different symmetry versions of the same knot type can produce different knots (such as the square knot, which is the connect sum of a trefoil and its mirror image, and the granny knot, which is the connect sum of two trefoils with the same handedness), keeping track of the action of

is a crucial element in this calculation. We treat this topic in a forthcoming manuscript [

11].

2. The Symmetry and Intrinsic Symmetry Groups

As we will describe below, the group

was first studied by Whitten in 1969 [

5], following ideas of Fox. They denoted this group

or

, where

is the number of components of

L. We can write this group as a semidirect product of

groups encoding the orientation of each component of the link

L with the permutation group

exchanging components of

L (cf. Definition 4.1), finally crossed with another

recording the orientation of

:

It is clear that an element

acts on

L to produce a new link

. If

, then

and

L are the same as sets (but the components of

L have been renumbered and reoriented), while if

the new link

is the mirror image of

L (again with renumbering and reorientation). We can then define the symmetry subgroup

by

For knots,

. Here the five subgroups of

correspond to the standard descriptions of the possible symmetries for a knot, as shown in

Table 2.

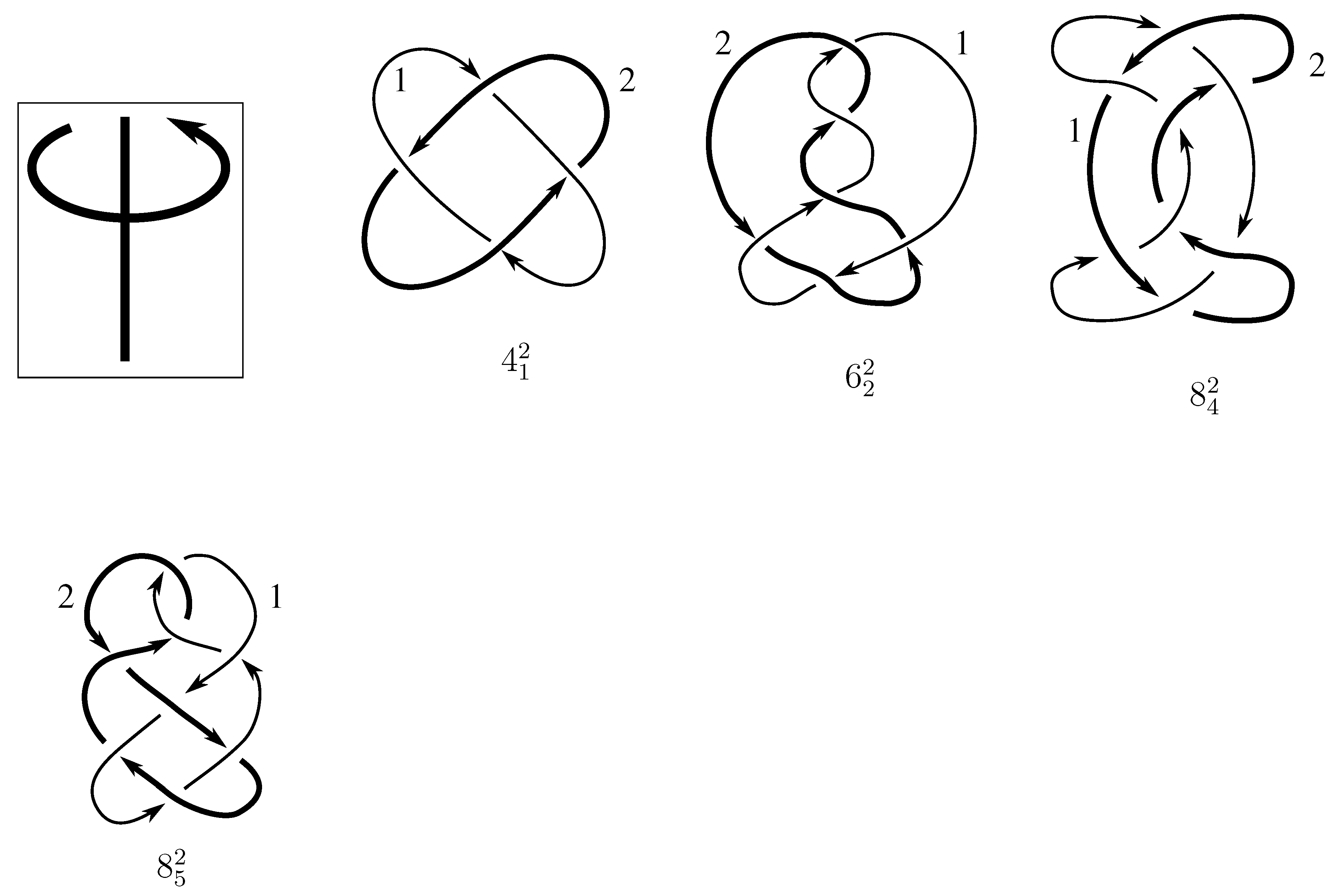

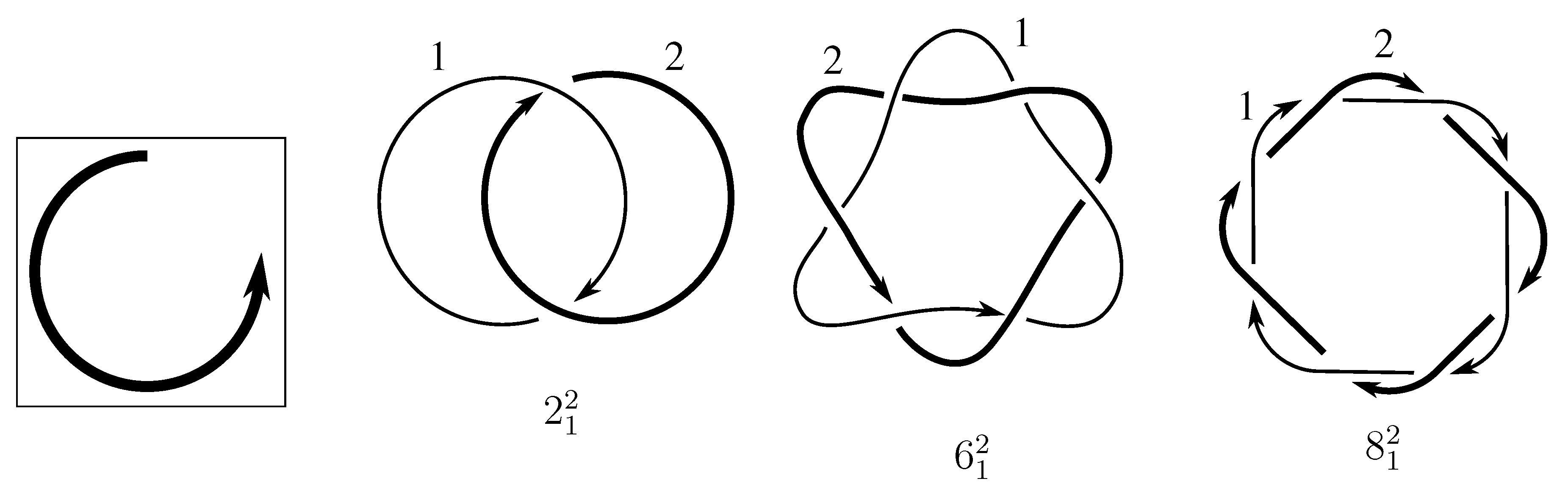

For links, the situation is more interesting, as the group

is more complicated. In the case of two-component links, the group

is a non-Abelian 16 element group isomorphic to

. The various subgroups of

do not all have standard names, but we will call a link

purely invertible if

, and say that components

have a

pure exchange symmetry if

. For two-component links, we will say that

L has pure exchange symmetry if its two components have that symmetry. The question of which links have this symmetry goes back at least to Fox’s 1962 problem list in knot theory, cf. Problem 11 in [

13] and [

14]. For example,

(the Hopf link) has pure exchange symmetry while we will show that

does not.

We similarly focus on the pure invertibility symmetry: we show that 45 out of the 47 prime links with 8 crossings or less are purely invertible. The two exceptions are

(the Borromean rings) and

; we show that both of these are invertible using some nontrivial permutation,

i.e.,

for some

. (Whitten found examples of more complicated links which are not invertible even when a nontrivial permutation is allowed [

15].)

Increasing the number of components in a link greatly increases the number of possible types of symmetry.

Table 3 lists the number of subgroups of

; each different subgroup represents a different intrinsic symmetry group that a

-component link might have. We note that if

is the symmetry subgroup of link

L, then the symmetry subgroup of

is the conjugate subgroup

. Therefore, it suffices to only examine the number of mutually nonconjugate subgroups of

in order to specify all of the different intrinsic symmetry groups.

Table 3 also lists the number of conjugacy classes of subgroups of

, and the number of these which appear for prime links of 8 or fewer crossings.

4. The Whitten Group

We begin by giving the details of our construction of the Whitten group

and the symmetry group

. Consider operations on an oriented, labeled link

L with

components. We may reverse the orientation of any of the components of

L or permute the components of

L by any element of the permutation group

. However, these operations must interact with each as well: if we reverse component 3 and exchange components 3 and 5, we must decide whether the orientation is reversed before or after the permutation. Further, we can reverse the orientation on the ambient

as well, a process which is clearly unaffected by the permutation. To formalize our choices, we follow [

5] to introduce the Whitten group of a

-component link.

Definition 4.1 Consider the homomorphism given bywhere is defined asFor and , we define the Whitten group

as the semidirect product with the group operationWe will also use the notation to refer to the Whitten group . 4.1. Link Operations

Given a link L consisting of oriented knots in , we may order the knots and write

Consider the following operations on L:

Let

be a combination of any of the moves (1), (2), or (3). We think of

as an element of the set

in the following way. Let

and

Lastly, let

be the permutation of the

associated to

. To be explicitly clear, permutation

p permutes the labels of the components; the component originally labeled

i will be labeled

after the action of

.

For each element,

in

, we define

where

is

with orientation reversed,

is the mirror image of

and the

appears above if and only if

. Note that the

ith component of

is

the possibly reversed or mirrored

th component of

L. Since we are applying

instead of

to

we are taking the convention of first permuting and then reversing the appropriate components.

Example 4.2 Let and . Then, .

Example 4.3 Let and . Then, . Since we have reversed the orientation on , note that will be the mirror image of L as well.

We now confirm that this operation defines a group action of the Whitten group on the set of links obtained from L by such transformations.

Proposition 4.4 The Whitten group is isomorphic to the group .

We know that L is a disjoint union of copies of denoted . Further, the mapping class groups of and are both , where the elements correspond to orientation preserving and reversing diffeomorphisms of and . In general, the mapping class group of disjoint copies of a space is the semidirect product of the individual mapping class groups with the permutation group . This means that and the Whitten group has a bijective map to .

It remains to show that the group operation * in the Whitten group maps to the group operation (composition of maps) in

. To do so, we introduce some notation. Let

and

. We must show

where

is the operation of the Whitten Group,

.

Then,

where

denotes the

i-th component

of

.

Note that

, which implies

Now,

and acts on

L as

We have dropped the notation for mirroring throughout the proof, because the two links clearly agree in this regard. The element preserves the orientation of if and only if , i.e., if either both or neither of and mirror L.

We can now define the subgroup of which corresponds to the symmetries of the link L.

Definition 4.5 Given a link, L and , we say thatL admits

when there exists an isotopy taking each component of L to the corresponding component of which respects the orientations of the components. We define as the Whitten symmetry group

of L, The Whitten symmetry group is a subgroup of , and its left cosets represent the different isotopy classes of links among all symmetries . By counting the number of cosets, we determine the number of (labeled, oriented) isotopy classes of a particular prime link.

Next, we provide a few examples of symmetry subgroups. Recall that the first Whitten group has order four and that is a non-Abelian 16 element group.

Example 4.6 Let , the figure eight knot. Since , we have , so the figure eight knot has full symmetry. There is only one coset of and hence only one isotopy class of knots.

Example 4.7 Let , a trefoil knot. It is well known that and , but , so we have . This means that the two cosets of are and , and there are two isotopy classes of knots. A trefoil knot is thus invertible.

Example 4.8 Let , whose components are an unknot and a trefoil . In Section 7.2, we determine all symmetry groups for two-component links, but we provide details for here. Since the components and are of different knot types, we conclude that no symmetry in can contain the permutation . Since , we cannot mirror L, i.e., the first entry of cannot equal . The linking number of L is nonzero, so we can rule out the symmetries and by Lemma 7.6. Last, L is purely invertible, meaning isotopic to . Thus, is the two element group . There are 8 cosets of this two element group in the 16 element group , so there are 8 isotopy classes of links. We now prove

Proposition 4.9 The Whitten symmetry group is the image of under the map .

Given a map , we see that if f is orientation-preserving on , then it is homotopic to the identity on since . This homotopy yields an ambient isotopy between L and , proving that . If f is orientation-reversing on , it is homotopic to a standard reflection r. Composing the homotopy with r provides an ambient isotopy between L and , proving that . This shows .

Now suppose . The isotopy from L to generates an orientation-preserving (since it is homotopic to the identity) diffeomorphism which either fixes L or takes L to . In the first case, . In the second, the map .

5. The Linking Matrix

For each link L, our overall strategy will be to explicitly give isotopies for certain elements of the symmetry subgroup , generate the subgroup containing those elements, and then rule out the remainder of using invariants. For three- and four-component links, a great deal of information about can usually be obtained by considering the collection of pairwise linking numbers of the components of the link.

We recall a few definitions:

Definition 5.1 Given a n-component link, with components , we let the linking matrix of L be the matrix so that and where is the linking number of and . We let denote the set of symmetric, integer-valued matrices with zeros on the diagonal.

The linking number can also be computed by counting the signed crossings of one knot over another. Among minimal crossing number diagrams of alternating links, the following three numbers are also useful link invariants:

Definition 5.2 The (overall) linking number of L is half the sum of the entries of the linking matrix. (This is half of the intercomponent signed crossings of L.) The writhe is the sum of all signed crossings of L. The self-writhe is the sum of the intracomponent signed crossings of L. Clearly, .

Murasugi and Thistlethwaite separately showed that writhe was an invariant of reduced alternating link diagrams [

19,

20]. Since linking number is an invariant for all links, self-writhe is also an invariant of reduced alternating diagrams. We will utilize this invariance to rule out certain symmetries of links, cf. Lemma 7.6.

The Whitten group

acts on the set of linking matrices

. Further, for a given link

L, the symmetry subgroup

must be a subgroup of the stabilizer of

under this action. This means that it is worthwhile for us to understand this action and make a classification of linking matrices according to their orbit types. We start by writing down the action:

Proposition 5.3 The action of the Whitten group on n-component links gives rise to the following action on the set of linking matrices : Equation (

1) reminds us that

This means that the

ith component of

is component

of

L. Recall that linking number is reversed by changing the orientation of either curve or the ambient

, which proves that we should multiply by

as claimed.

Corollary 5.4 For , let . The action of on can be writtenwhere as sets. In principle, this description of the action provides all the information one needs to compute orbits and stabilizers for any given matrix (for instance, by computer). However, that brute force approach does not yield much insight into the structure of the problem. We now develop enough theory to understand the situation without computer assistance in the case of three-component links.

5.1. Linking Matrix for Three-Component Links

We first observe that there is a bijection between

and

given by

We would like to understand the action of

on

by reducing it to the natural action of the simpler group

on

.

Proposition 5.5 The action of on descends to the natural action of on via the surjective homomorphism defined bywhere We first check that

. Now

. This means that

since

for any permutation

p. But

This proves that

f is a homomorphism. In order to show that

f is surjective we will compute the kernel. Consider the image

. Then the product

since

.

Note that direct computation shows that the pre-image of a general element is given by and . So suppose that . It is clear that and . Since , if , then and . Likewise, if , then as well, and .

Since is a group of order 96 and the kernel of f has order 2, the image of f has order 48. Since the target group also has order 48, we conclude that f is surjective, as claimed.

By Corollary 5.4, the

action on

maps each entry

in the linking matrix to

,

i.e.,

By the definition of

f, the natural action of

on

is

This triple corresponds precisely to the new linking matrix (

3) obtained from the

action, so we have shown the two actions correspond.

We are now in a position to classify linking matrices according to their orbit types, and compute their stabilizers in . The stabilizer of a linking matrix as a subgroup of under the group action of Proposition 5.3 is the pre-image under the homomorphism f of Proposition 5.5 of the stabilizer of the corresponding triple under the natural action of on . Since the kernel of f has order 2, stabilizers in are twice the size of the corresponding stabilizers in .

There are 10 orbit types of triples under this action. To list the orbit types, we write a representative triple in terms of variables a, b, and c which are assumed to be integers with distinct nonzero magnitudes. To list the stabilizers, we either give the group explicitly as a subgroup of or provide a list of generators in the form . One of these groups, , is more complicated and is described below.

The group

is a 6 element group isomorphic to

(or

) given by

Using the pre-image formula in the proof of Proposition 5.5, it is easy to compute the stabilizer of a given linking matrix in directly from the table above; we simply conjugate by a permutation to bring the corresponding triple into one of the forms above and then apply the pre-image formula.

We can now draw some amusing conclusions which might not be obvious otherwise, such as:

Lemma 5.6 If L is a three-component link and any element of reverses orientation on then at least one pair of components of L has linking number zero.

The stabilizer of includes an element of the form if and only if some element in the stabilizer of the corresponding triple has since we showed in the proof of Proposition 5.5 that equaled .

A negative will switch the sign of the linking number ; to stabilize the triple there must be an even number of sign changes unless some . Hence, if L has some mirror symmetry, i.e., one with , then which produces an odd number of sign changes, so some linking number .

Example 5.7 We will see that the linking matrix for has corresponding triple in the form . This means that the stabilizer of this linking matrix is a group of order 12 isomorphic to in conjugate to the pre-image of the stabilizer . Using the pre-image formula of Proposition 5.5, we can explicitly compute

Conjugating this subgroup by , we obtain the stabilizer of :

We know that is a subgroup of this stabilizer; actually, it equals the stabilizer, which we show in Section 8.4. 5.2. Linking Matrix for Four-Component Links

For four-component links, we will need to develop a different observation. There are only three prime four-component links with 8 or fewer crossings, and fortunately they all possess a particular type of linking matrix. While the situation seems too complicated to make a full analysis of the

action on the 6 nonzero elements of a general

linking matrix, it is relatively simple to come up with a theory which covers our cases. We first give a correspondence between certain

linking matrices and elements of

:

Equivalently, we let

If we let

act on the matrix

as usual, matrices in this form are fixed by the subgroup with permutations in an 8 element subgroup of

isomorphic to

which we will call

.

Proposition 5.8 Let denote the subgroup (isomorphic to ) of . The action of the subgroup on descends to the natural action of on via the homomorphismwhere is defined as A series of easy but lengthy direct computations show that this homomorphism has a kernel of order 4 given by

and the image of

f in

is

. The pre-image of such an element is the 4 element set

, where

and

are arbitrary.

To show that the action of

G on

descends to the natural action of

on

,

i.e.,

we need only check that

for all

. This is another straightforward, if lengthy, computation.

We now need to find stabilizers for a few carefully chosen linking matrix types.

Lemma 5.9 The stabilizers in of , , and are all 8 element groups isomorphic to . These produce 32-element stabilizers for the corresponding linking matrices in isomorphic to . The individual stabilizers in are in the form where the are determined uniquely by p. For , the . In the other two cases, the pattern of signs is more intricate. We give the subgroups explicitly below in Table 7. As before, we can draw some conclusions about links from this theory which we might not have noticed otherwise. For example,

Corollary 5.10 If L is a four-component link with linking matrix in the form of Equation (4), then no element of exchanges components 1 and 3 without also exchanging components 2 and 4. 7. Two-Component Links

This section records the symmetry group

for all prime two-component links with eight or fewer crossings; there are 30 such links to consider. Our results are summarized in

Section 7.1, which names and lists the symmetry groups which appear (see

Table 8). We count how frequently each group appears by crossing number in

Table 9. The symmetry group for each link is listed in

Table 4 and

Table 10, by group and by link, respectively. Proofs of these assertions appear in

Section 7.2 7.1. Symmetry Names and Results

The Whitten group

of all possible symmetries for two-component links is a non-Abelian 16 element group isomorphic to

. The symmetry group

of a given link must form a subgroup of

. There are 27 mutually nonconjugate subgroups of

; of these possibilities, only seven are realized as the symmetry subgroup of a prime link with 9 or fewer crossings (see

Table 8). An eighth appears as the symmetry subgroup of a 10-crossing link.

Question 7.1 Do all 27 nonconjugate subgroups of appear as the symmetry group of some (possibly composite, split) link? Of some prime, non-split link?

Hillmann [

8] provided examples for a few of these symmetry subgroups, but some of his examples were split links. Here are the groups we found among links with 8 or fewer crossings.

The first seven nontrivial groups in

Table 8 are realized as the symmetry group of a link with nine or fewer crossings, while

appears to be the symmetry group of a 10-crossing link. We know of no nontrivial links with full symmetry but speculate that they exist. We now give three tables of results.

Table 9 records the frequency of each group.

Table 10 lists the prime two-component links of eight or fewer crossings by symmetry group. And

Table 4 lists each two-component link and its corresponding Whitten symmetry group.

Theorem 7.2 The symmetry groups for all prime two-component links up to 8 crossings are as listed in Table 4. The proof of this theorem is divided into five cases, based on the five symmetry groups that appear in

Table 4; these proofs are found in

Section 7.2. Many of our arguments generalize to various families of links. As this paper focuses on these first examples, we ask for the reader’s understanding when we eschew the most general argument in favor of a simpler, more expedient one.

7.2. Proofs for Two-Component Links

Below, we attempt to provide a general framework for determining symmetry groups for two-component links. Since is a subgroup of , the order of the symmetry group must divide . Our strategy begins by exhibiting certain symmetries via explicit isotopies. With these in hand, we next use various techniques to rule out some symmetries until we can finally determine the symmetry group . These techniques generally involve using some link invariant to show . Among link invariants, the linking number and self-writhe (for alternating links) are easily applied since they count signed crossings; we also use polynomials and other methods.

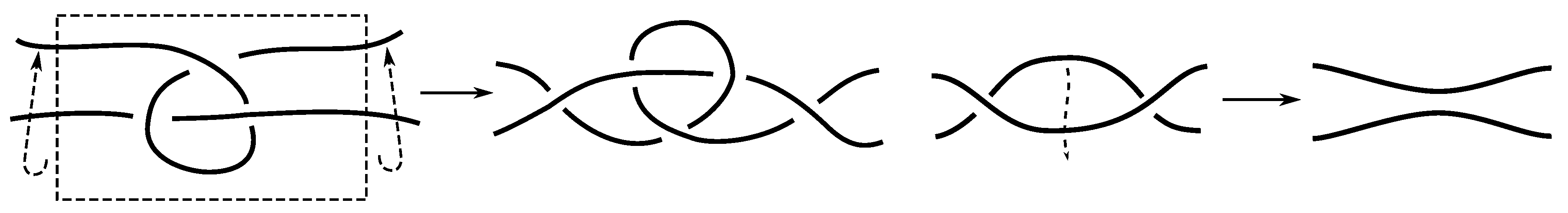

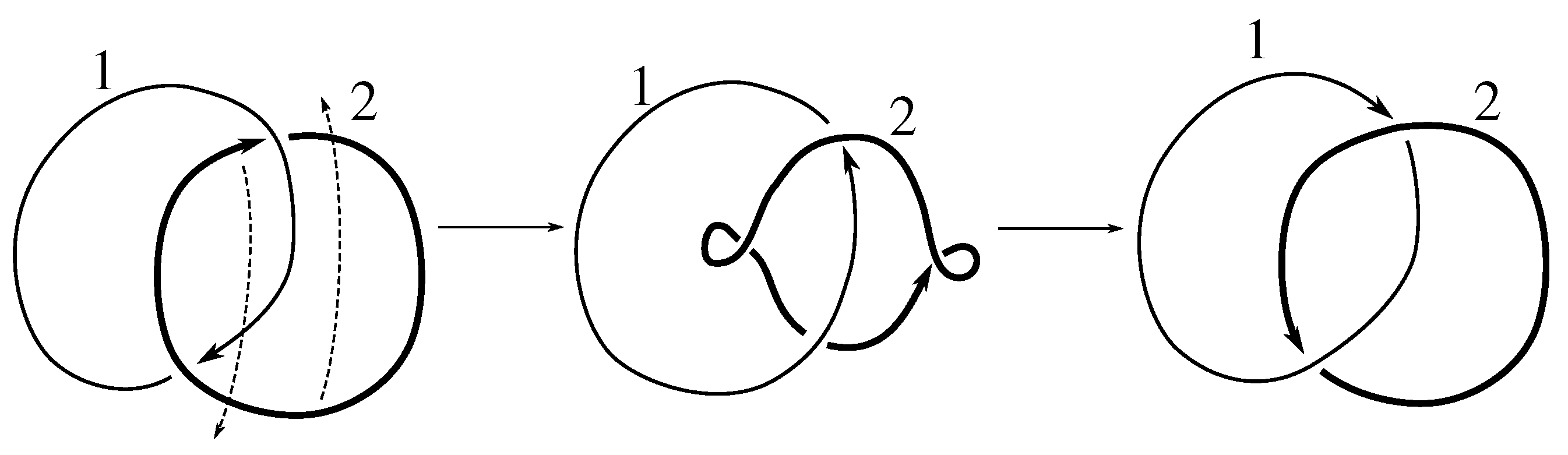

We focus on the 30 prime links with eight or fewer crossings. Our first results indicate which of these 30 links have either a pure invertibility or a pure exchange symmetry, which we prove explicitly by exhibiting isotopies. Recall that a link is purely invertible if reversing all components’ orientations produces an isotopic link; a link has pure exchange symmetry if swapping its two components is an isotopy.

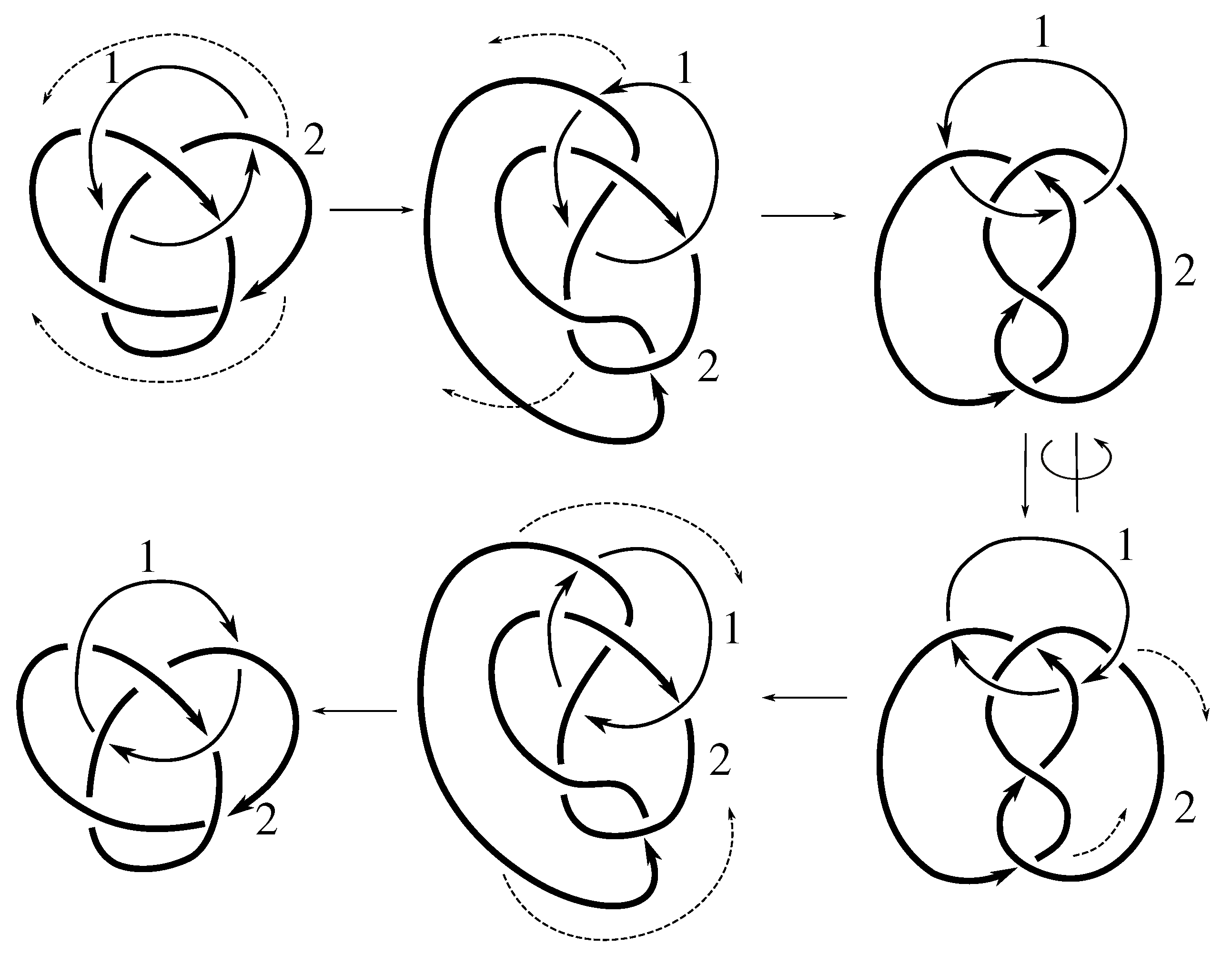

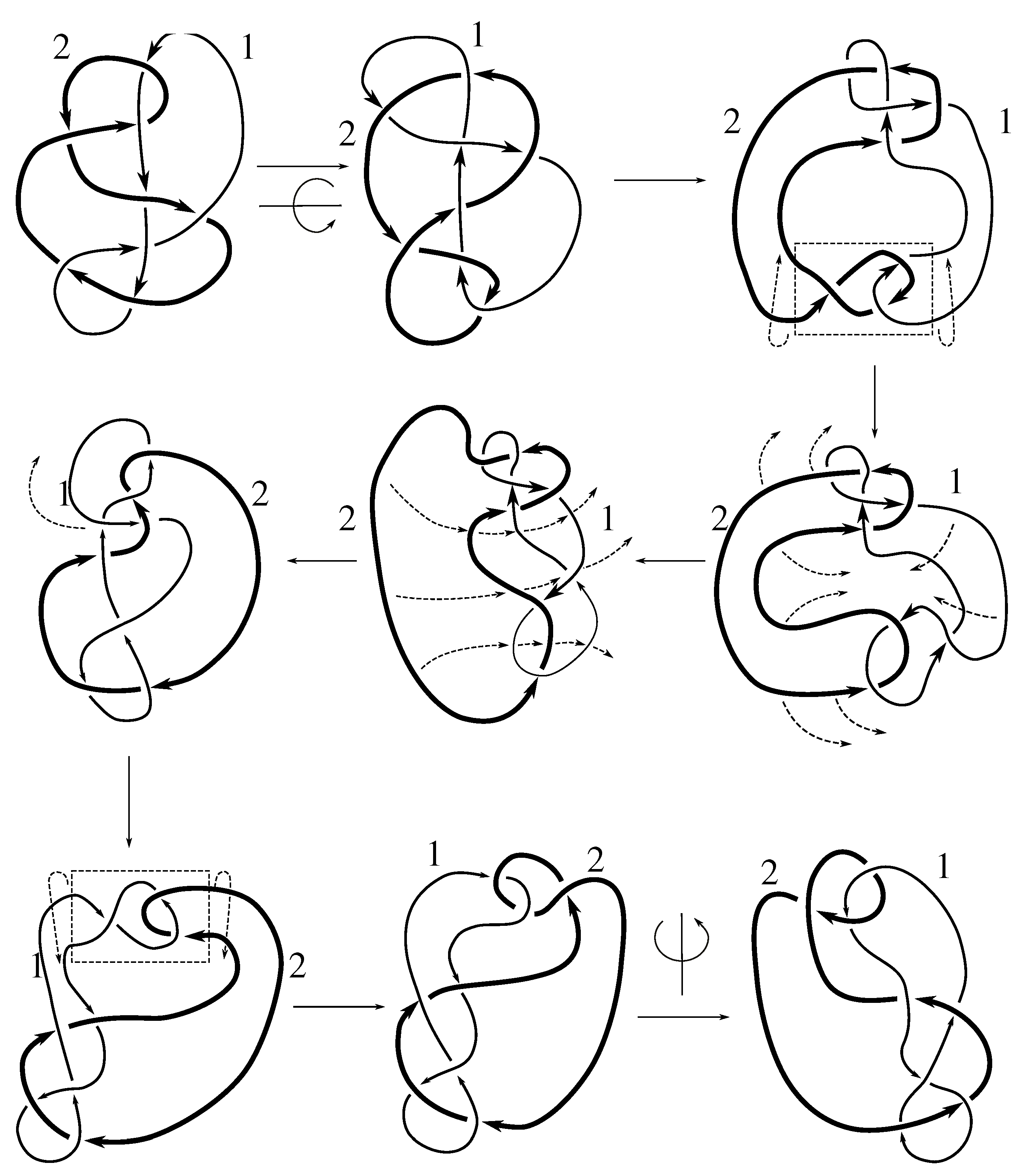

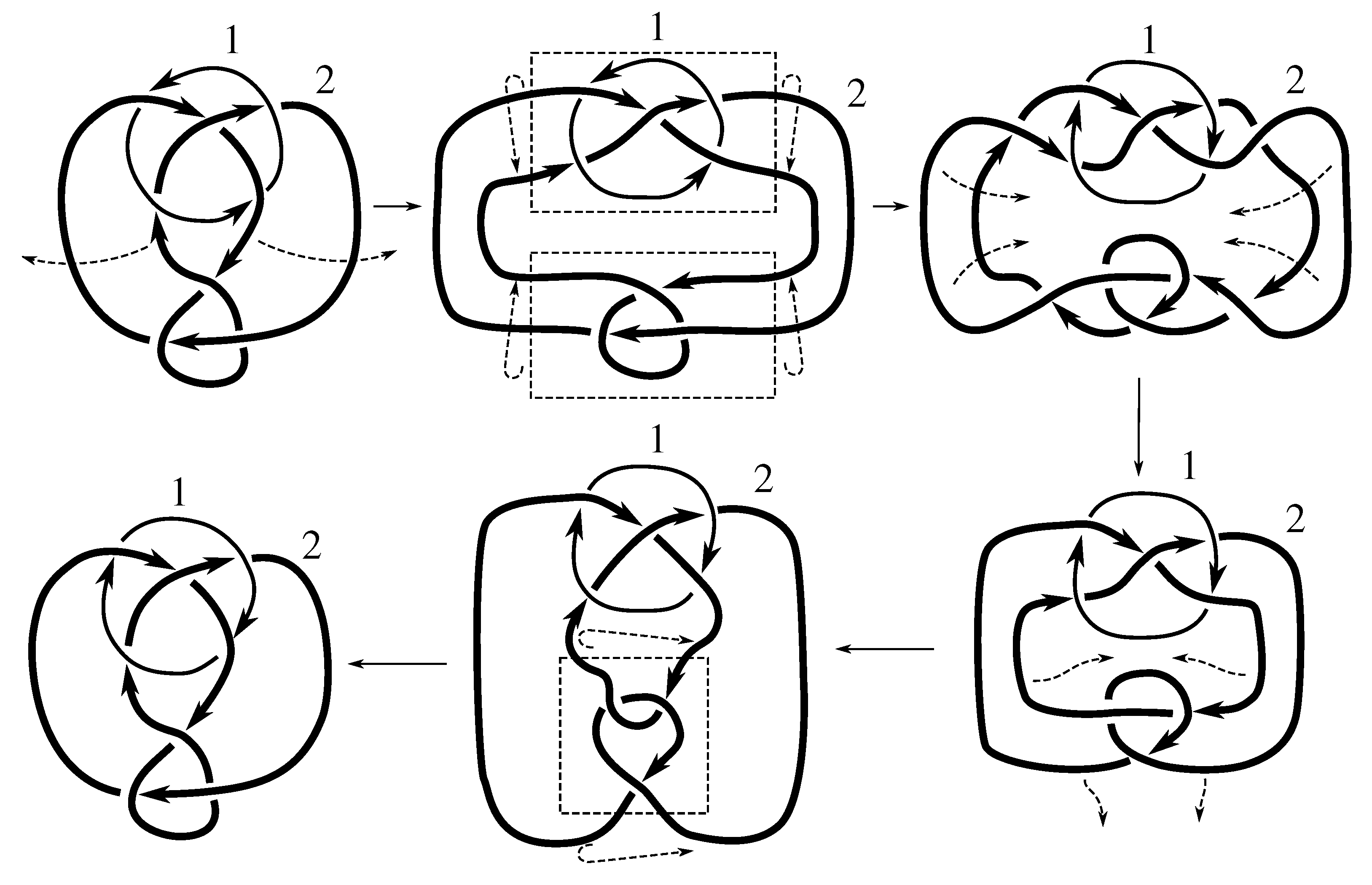

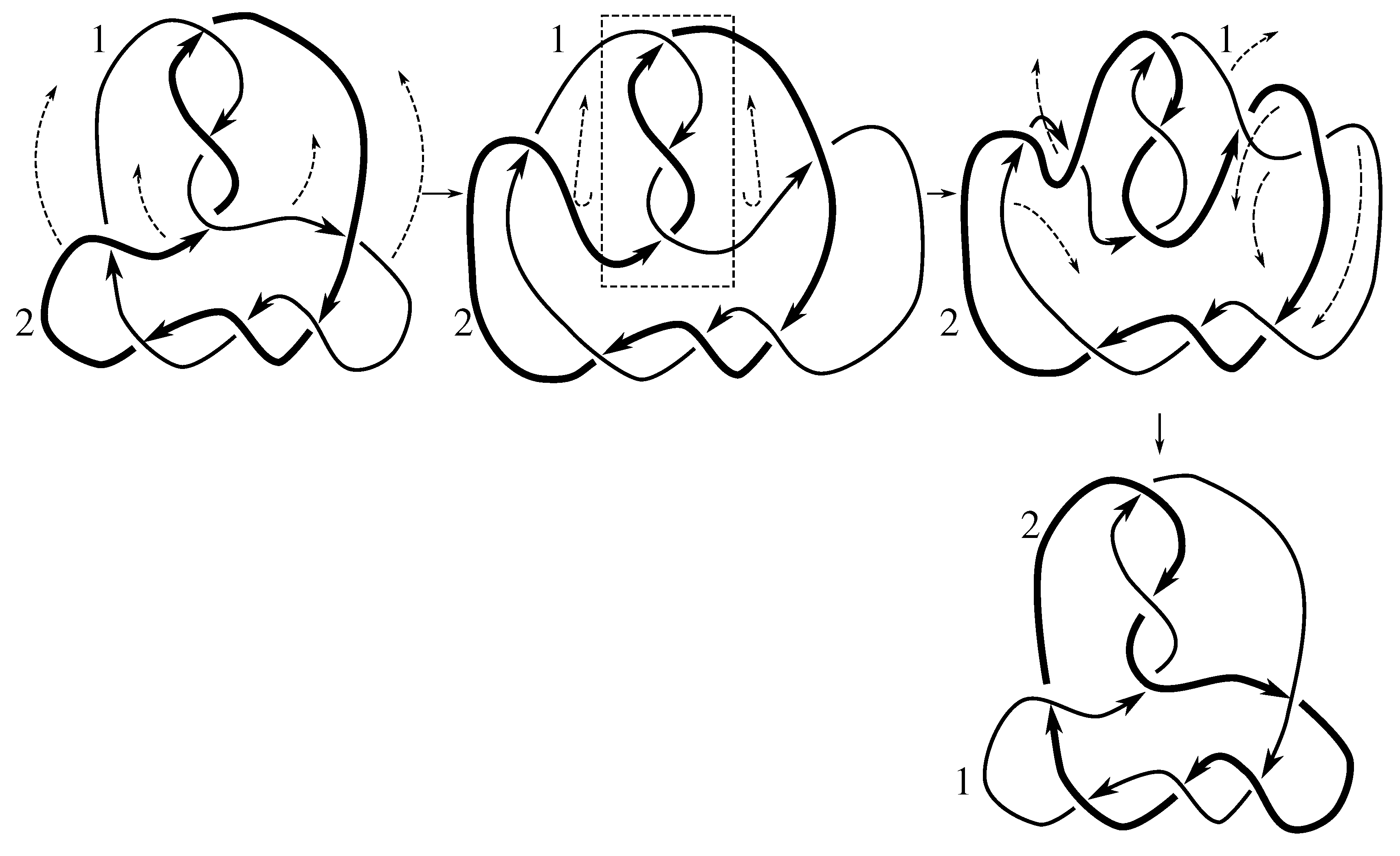

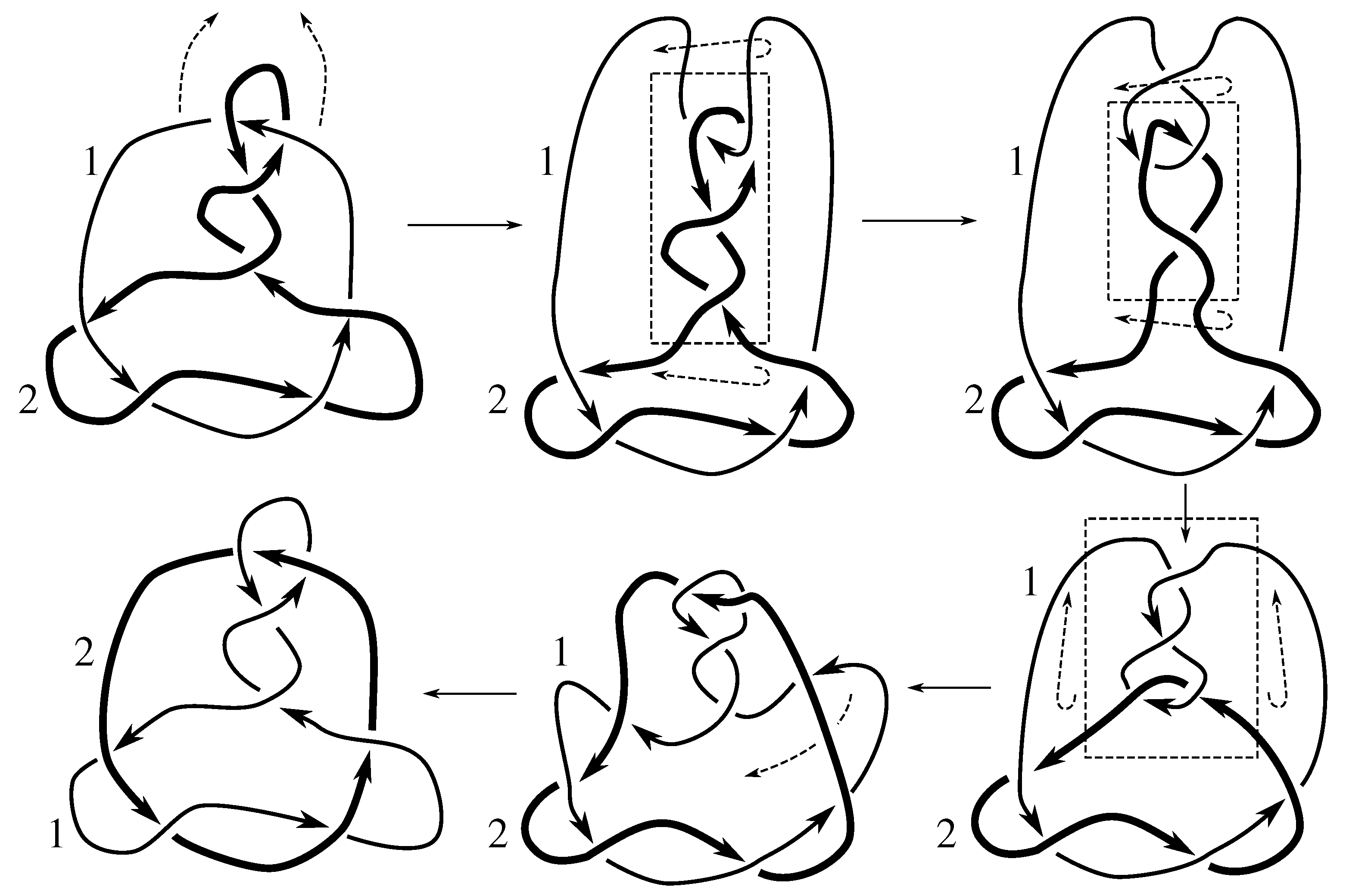

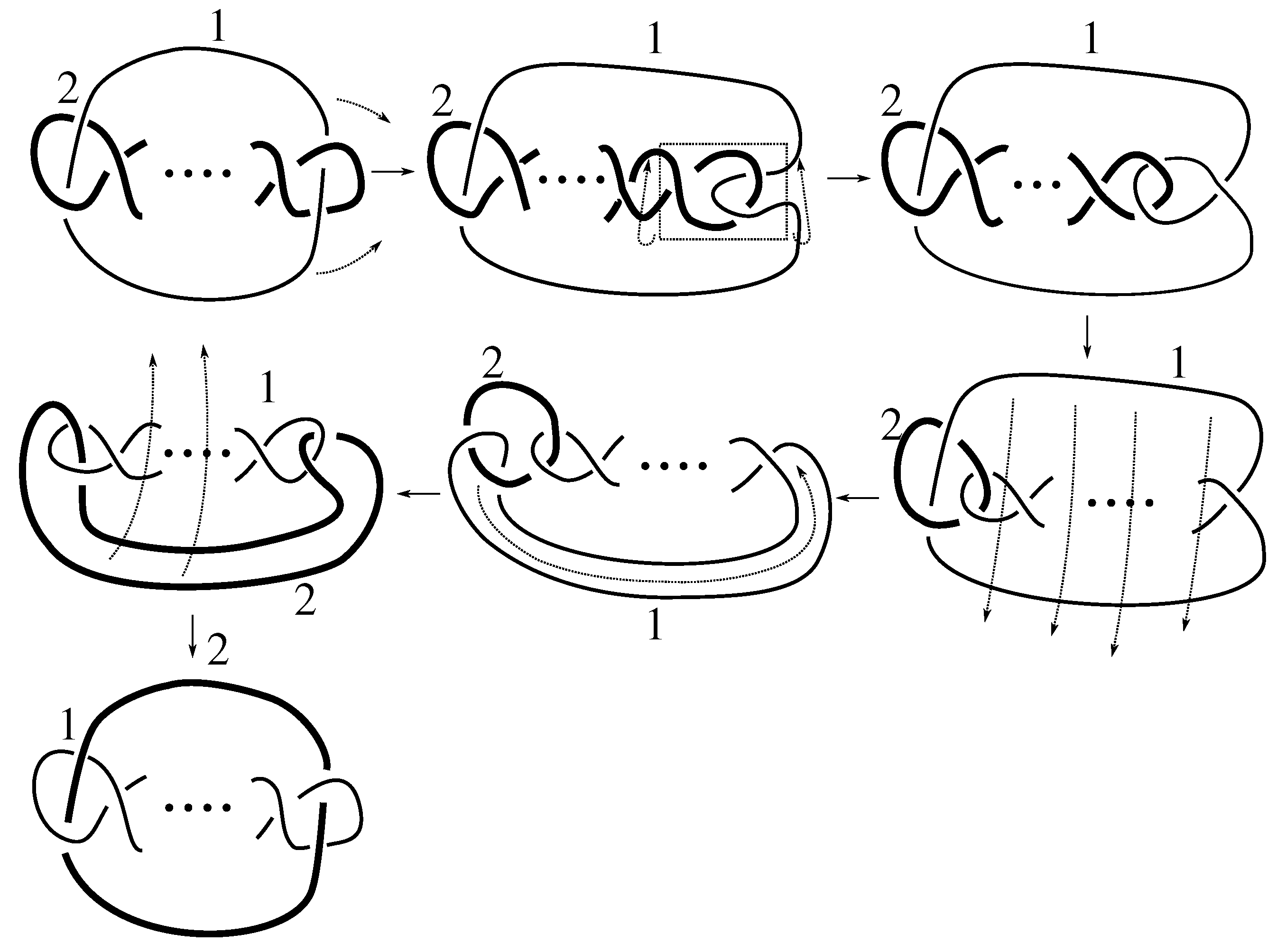

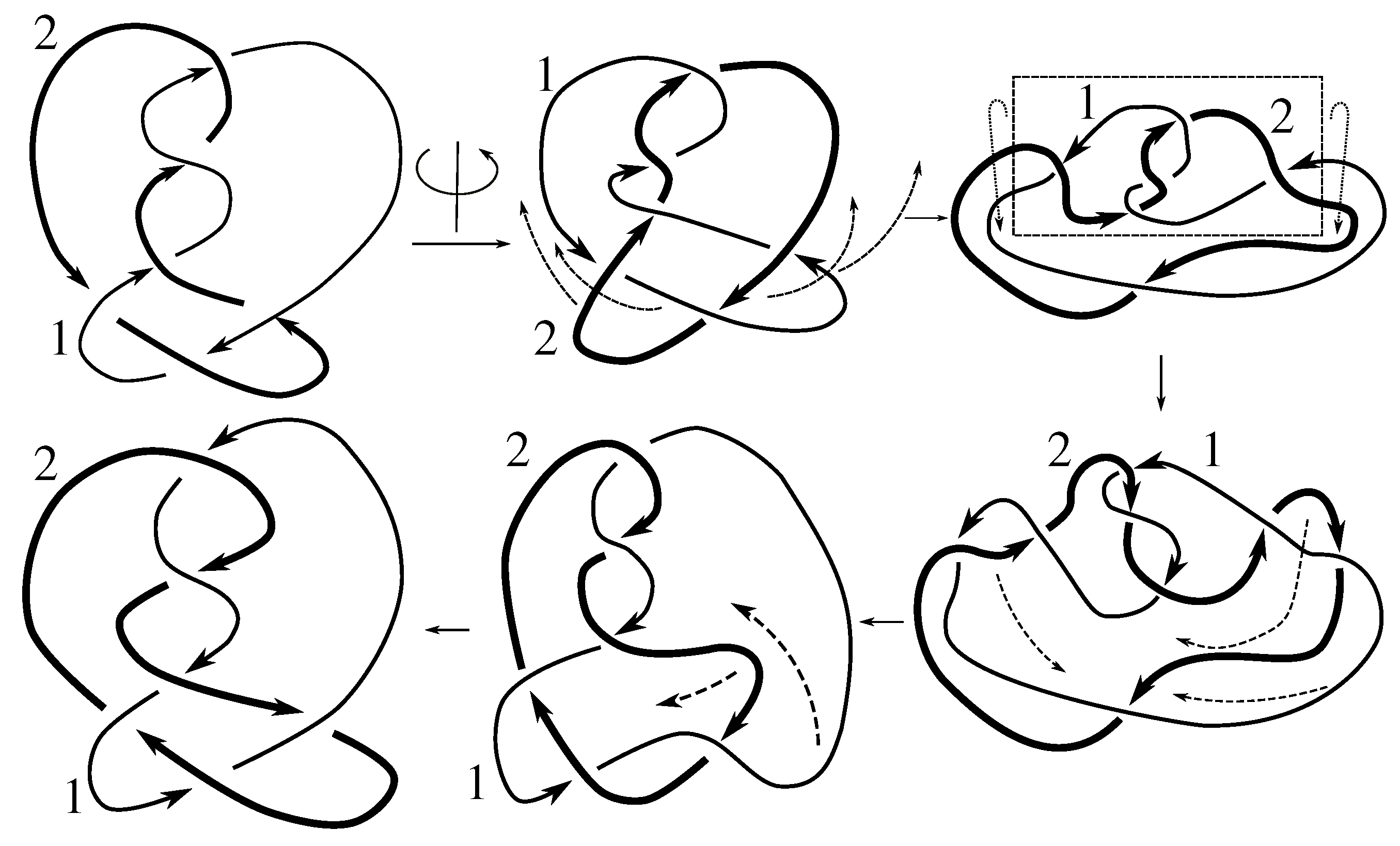

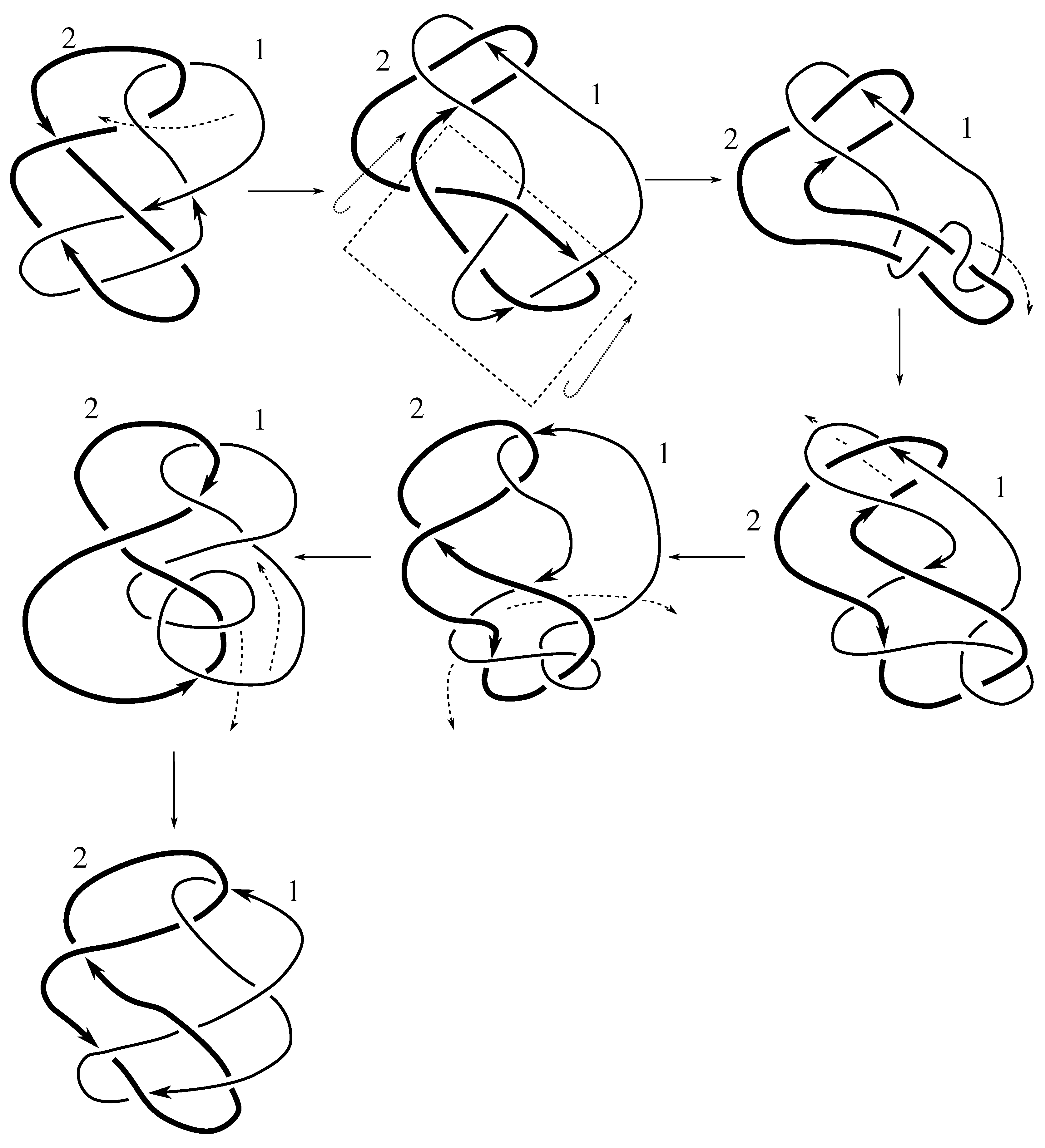

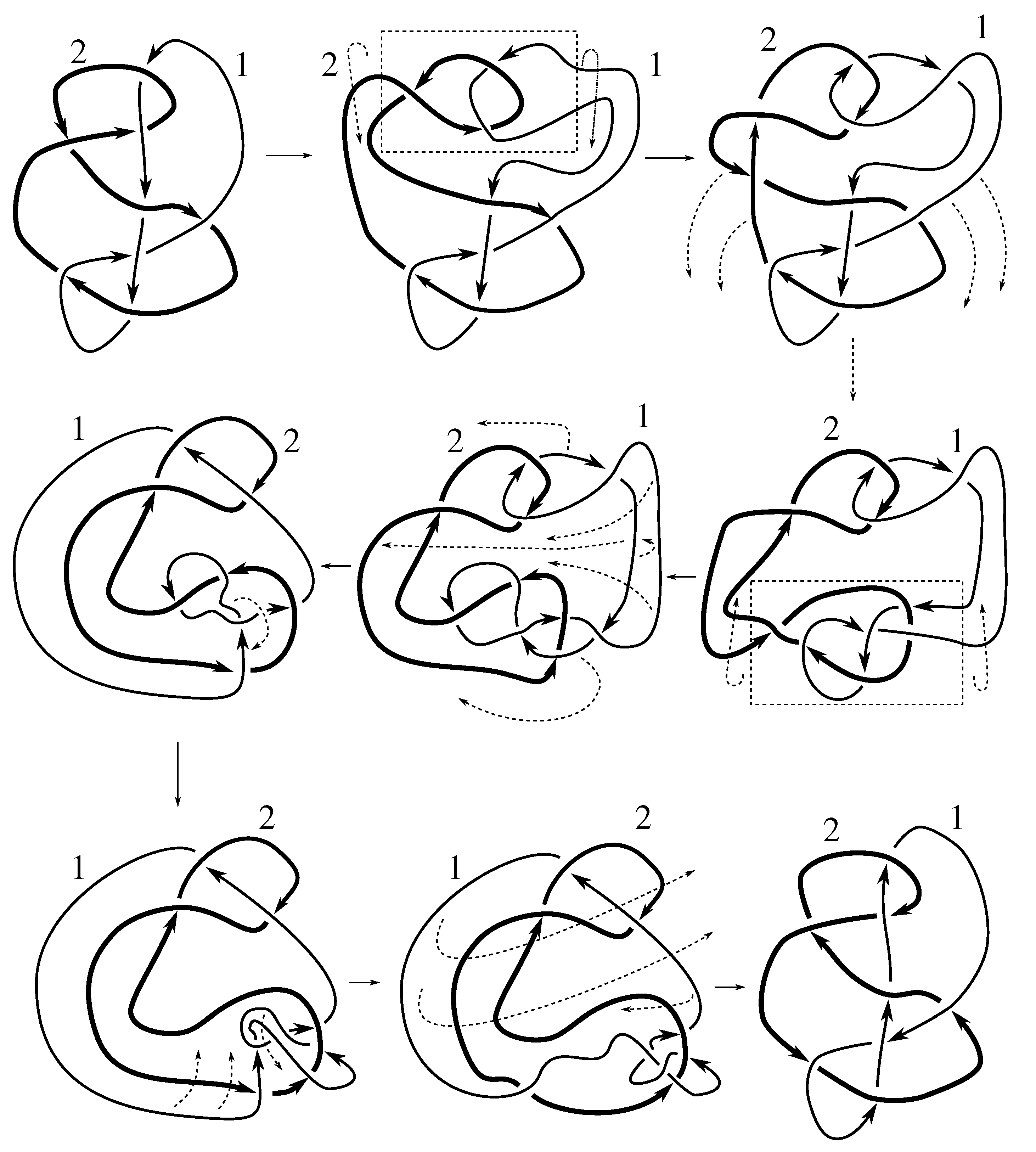

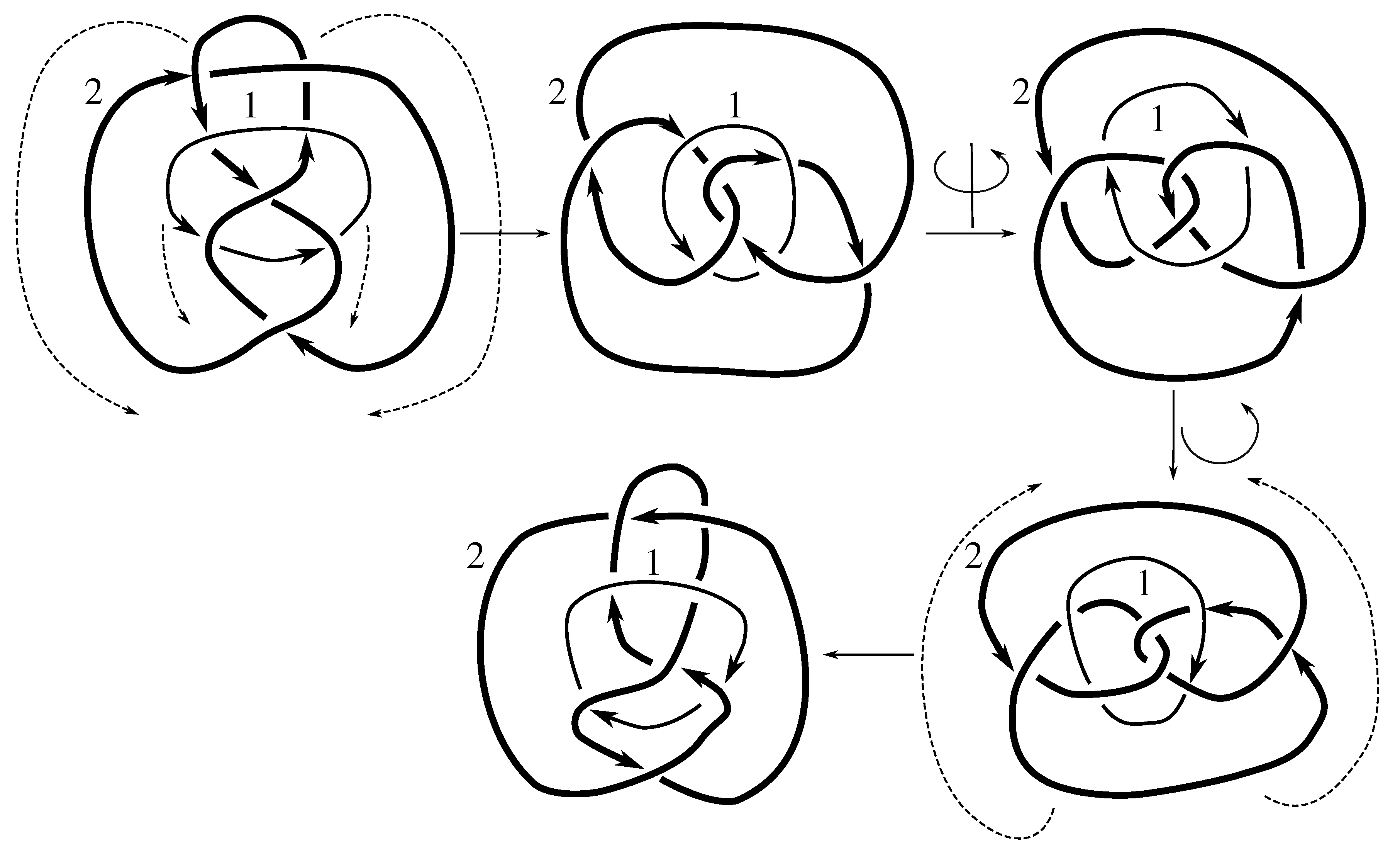

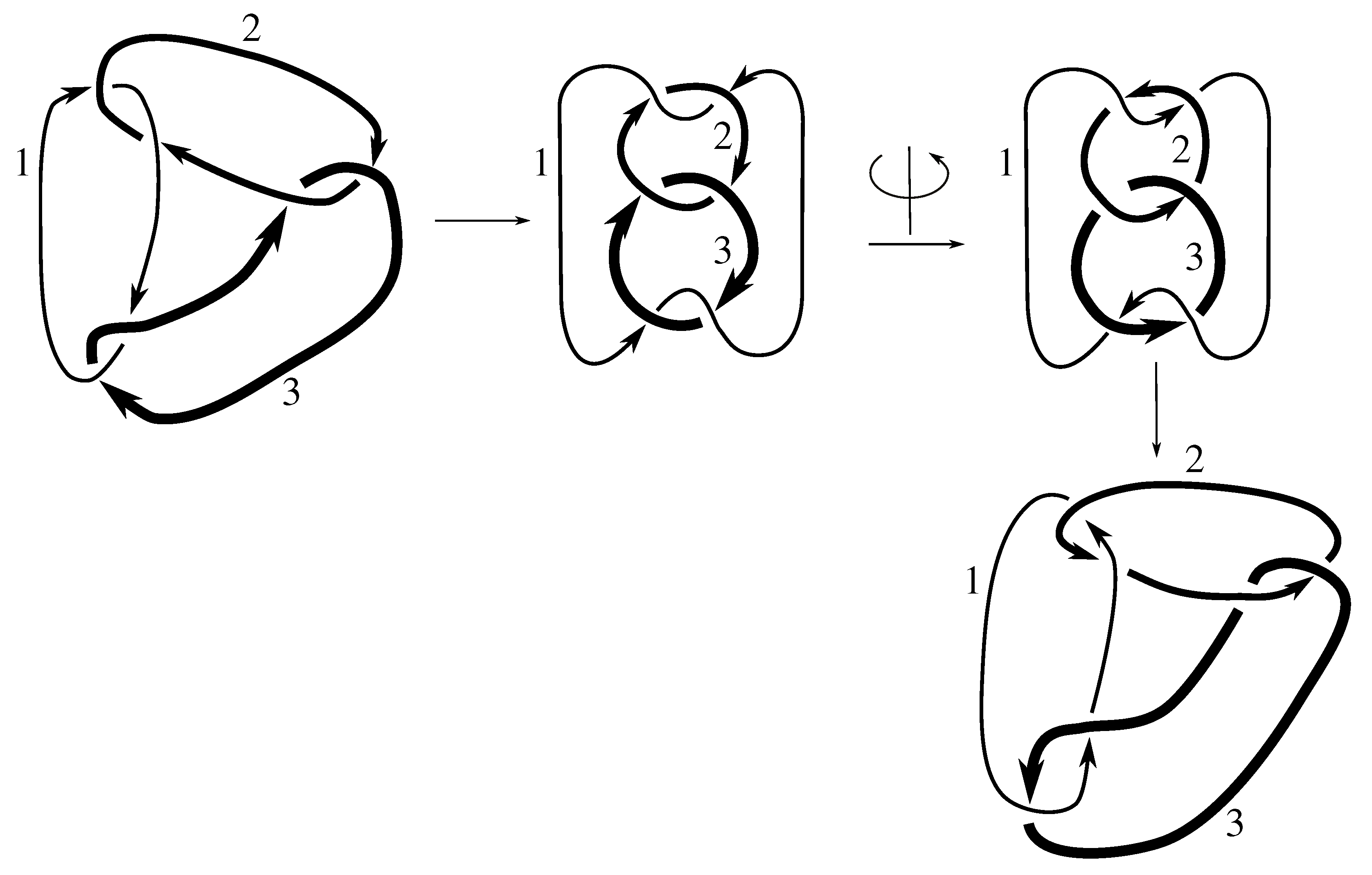

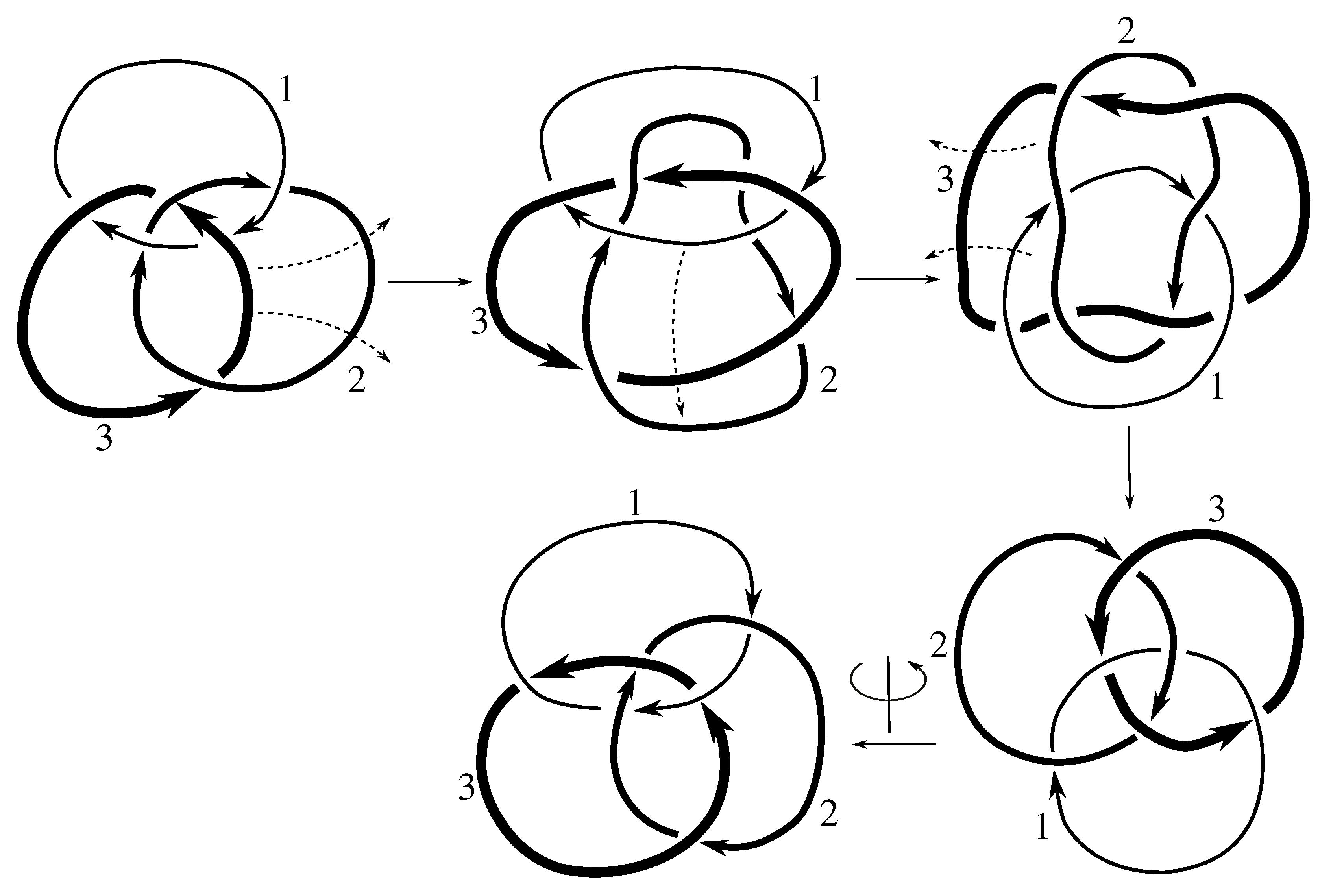

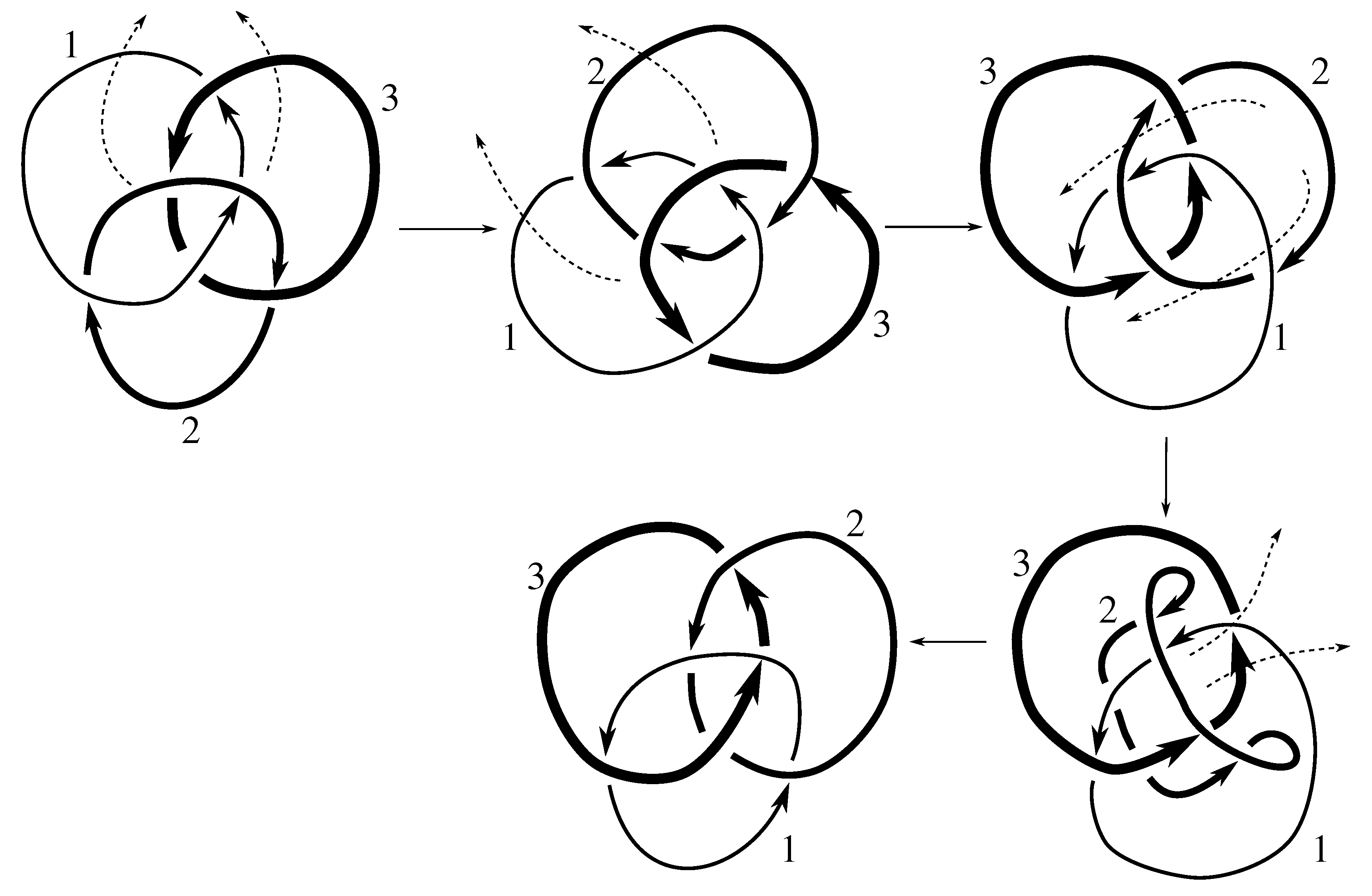

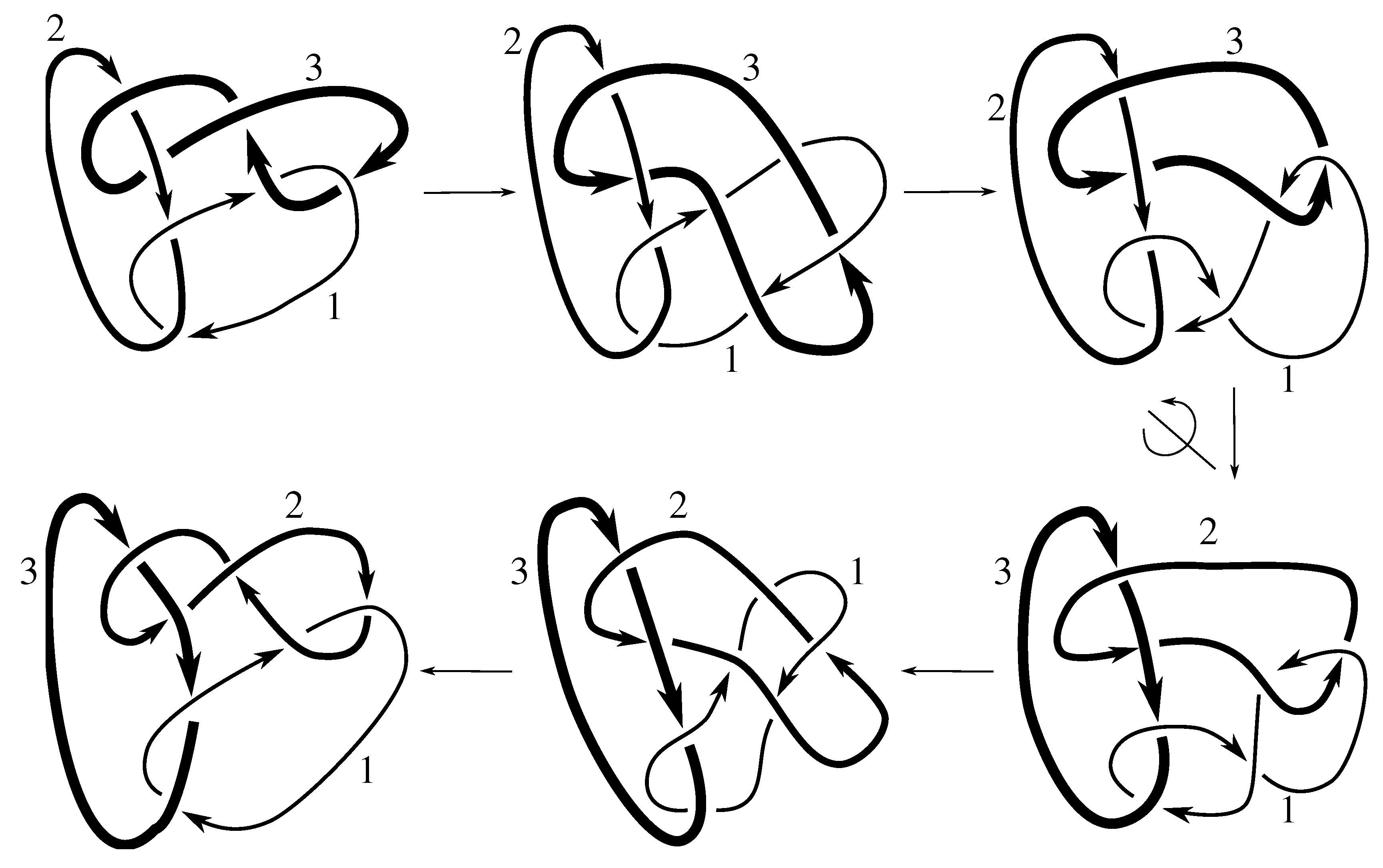

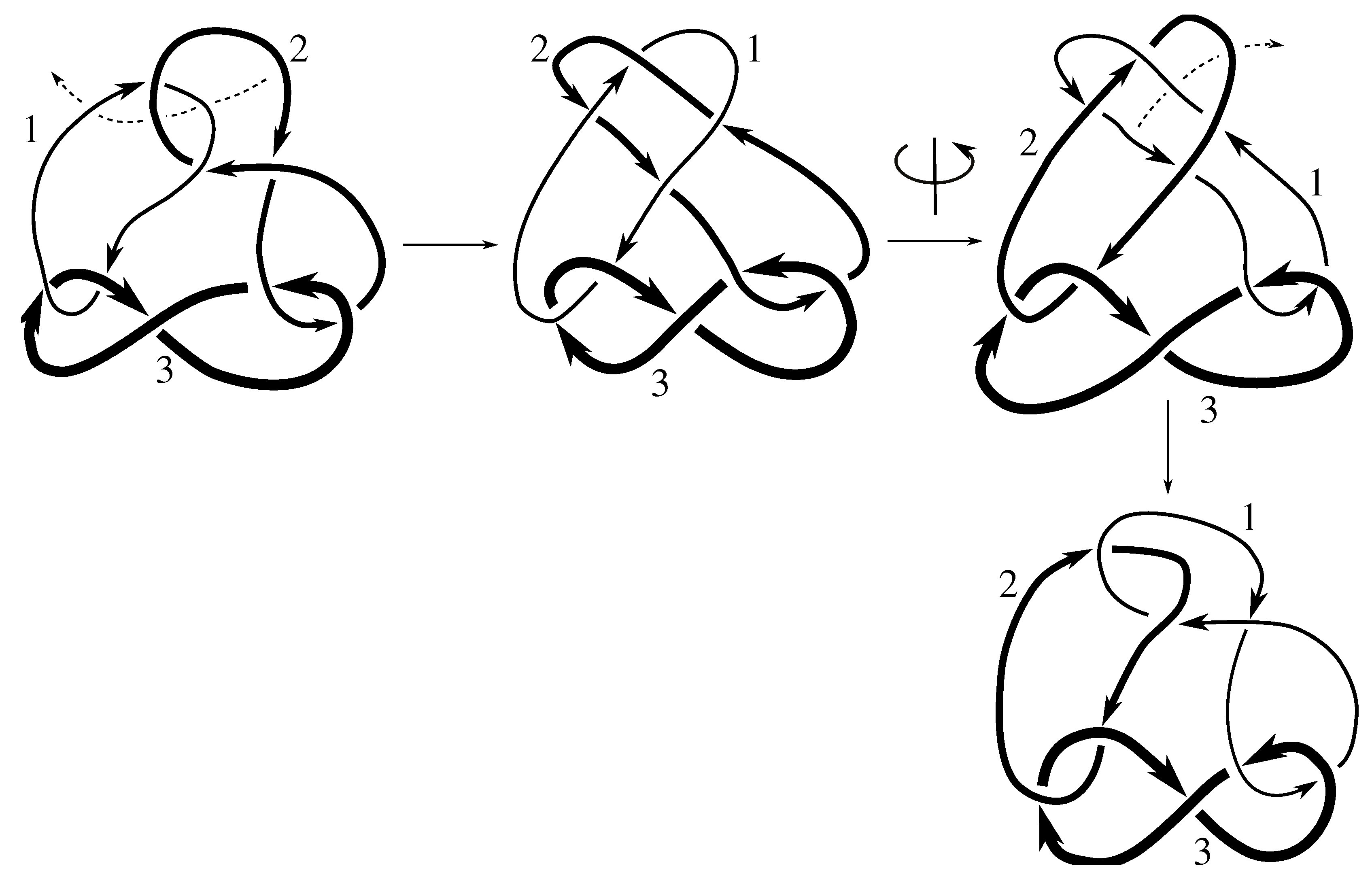

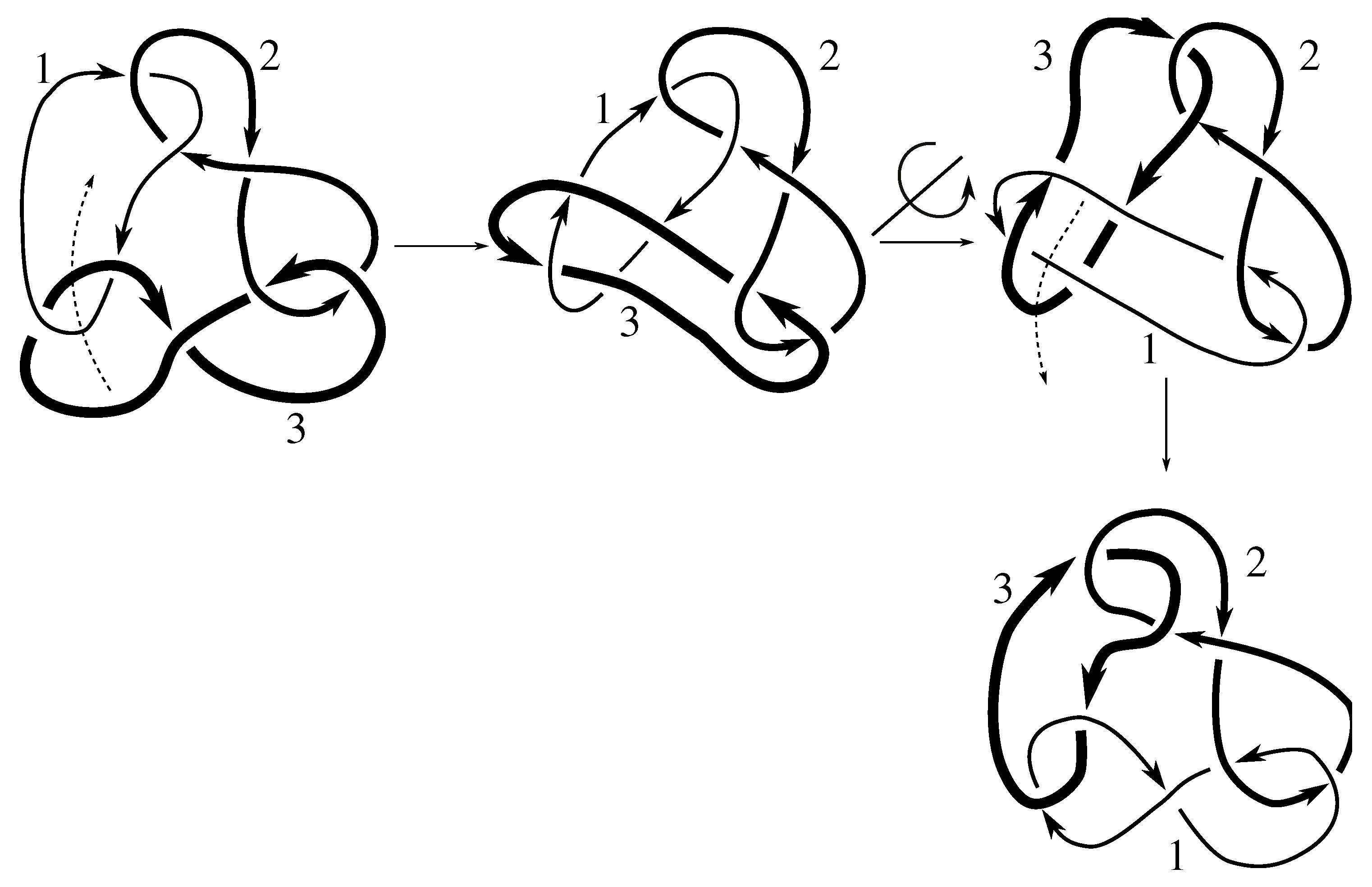

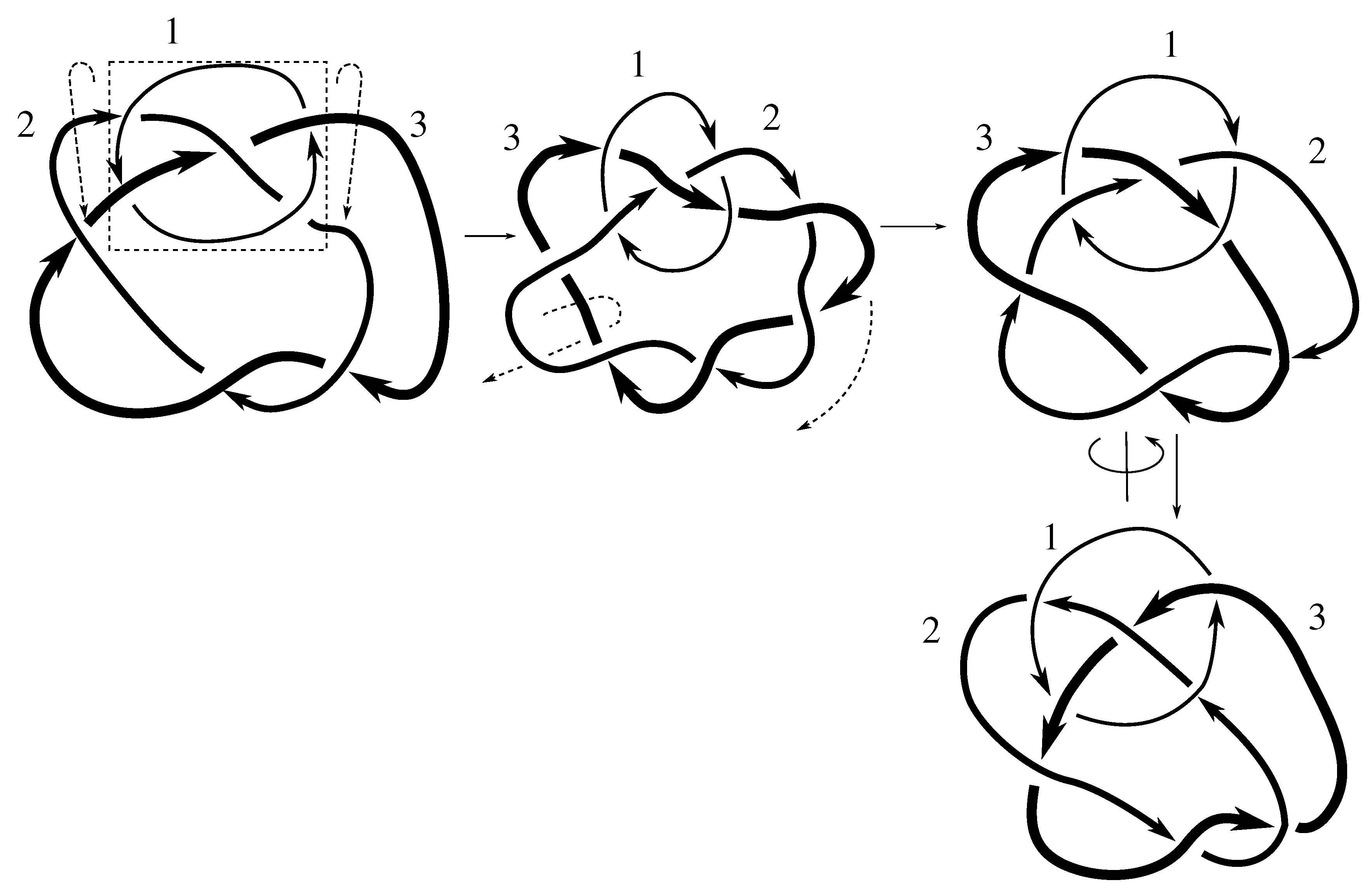

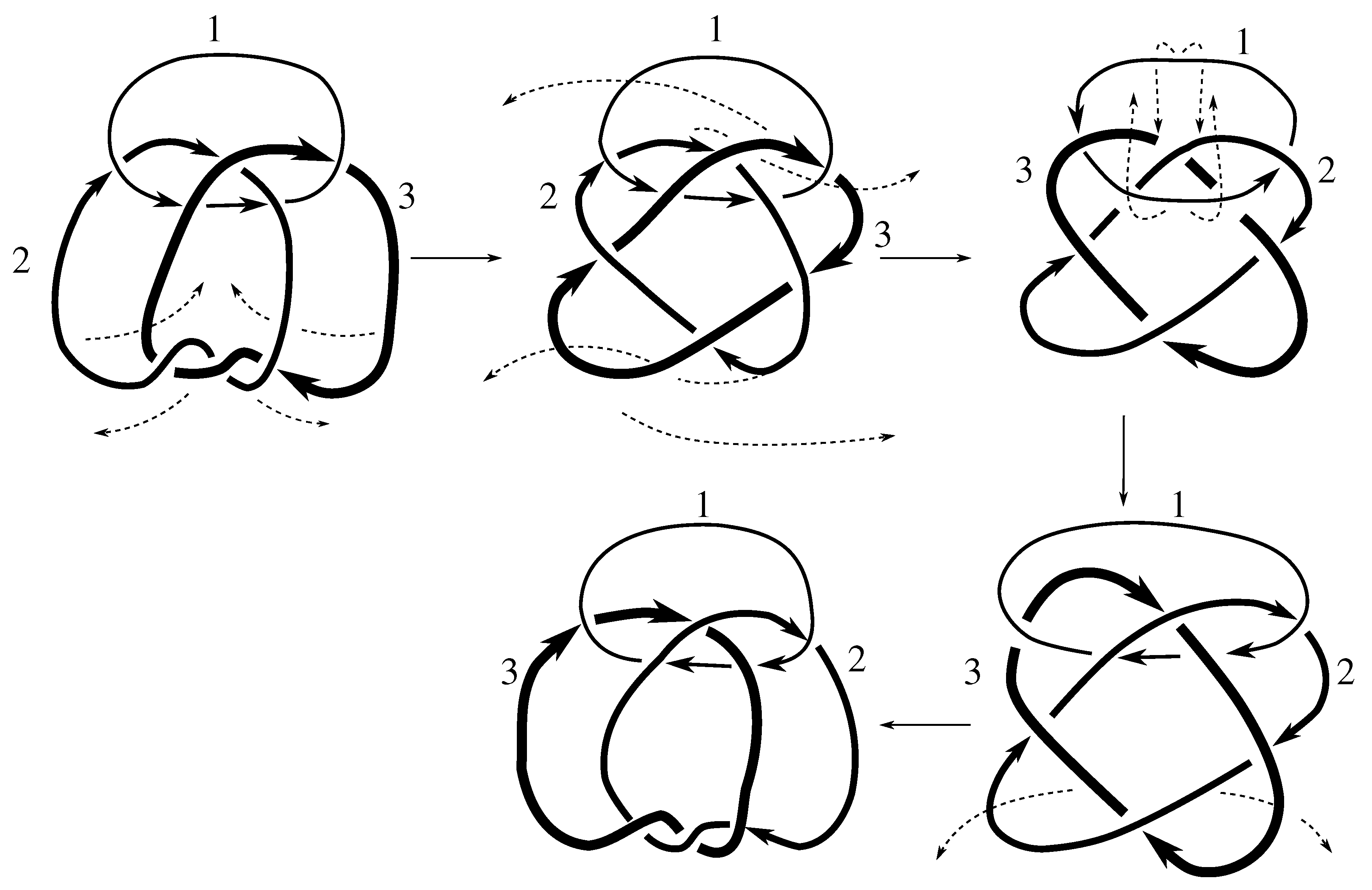

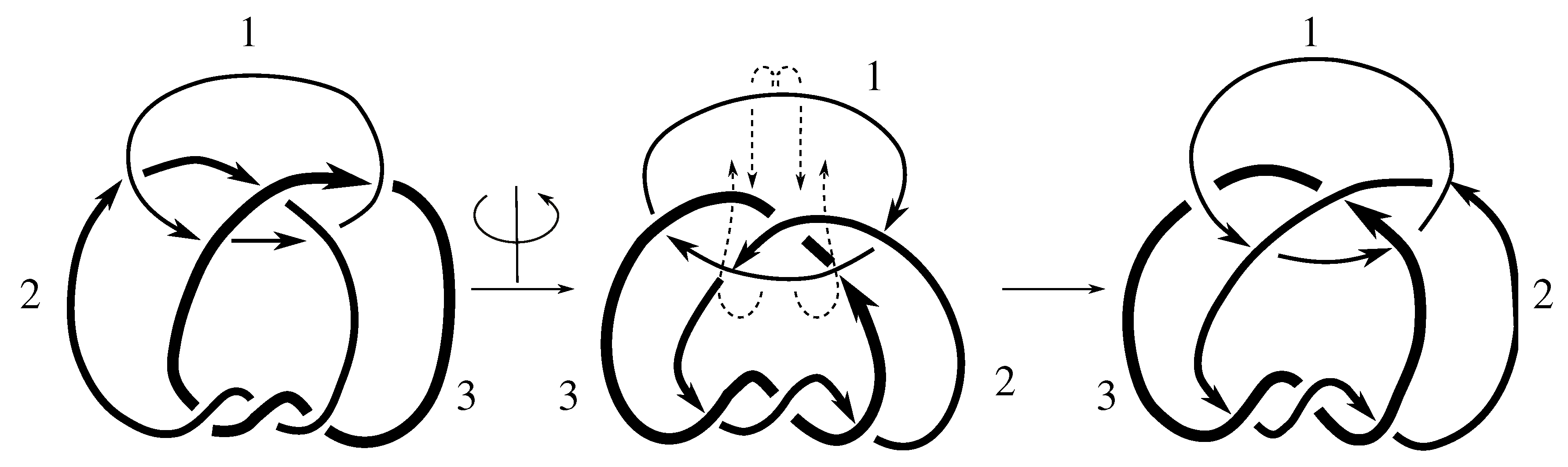

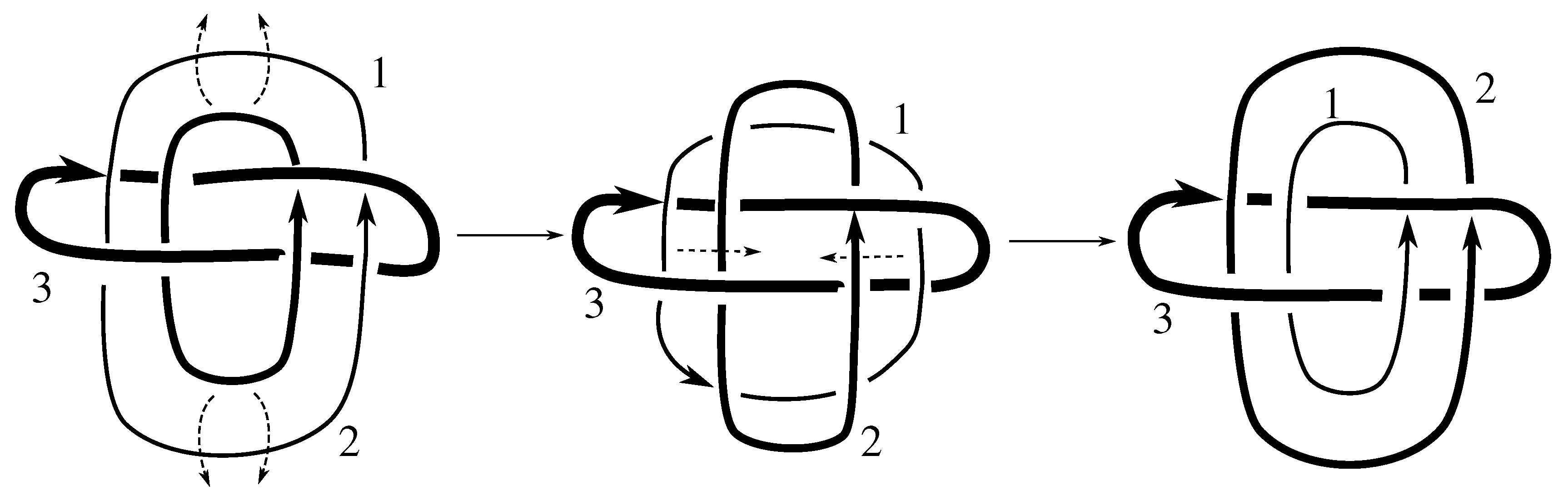

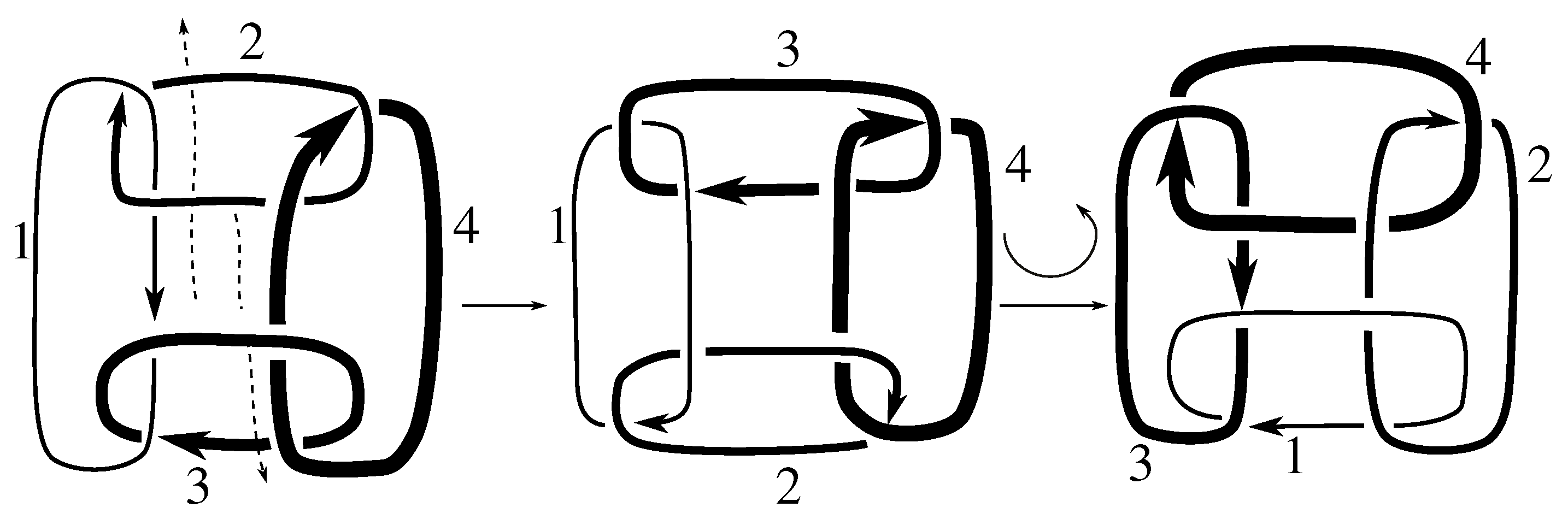

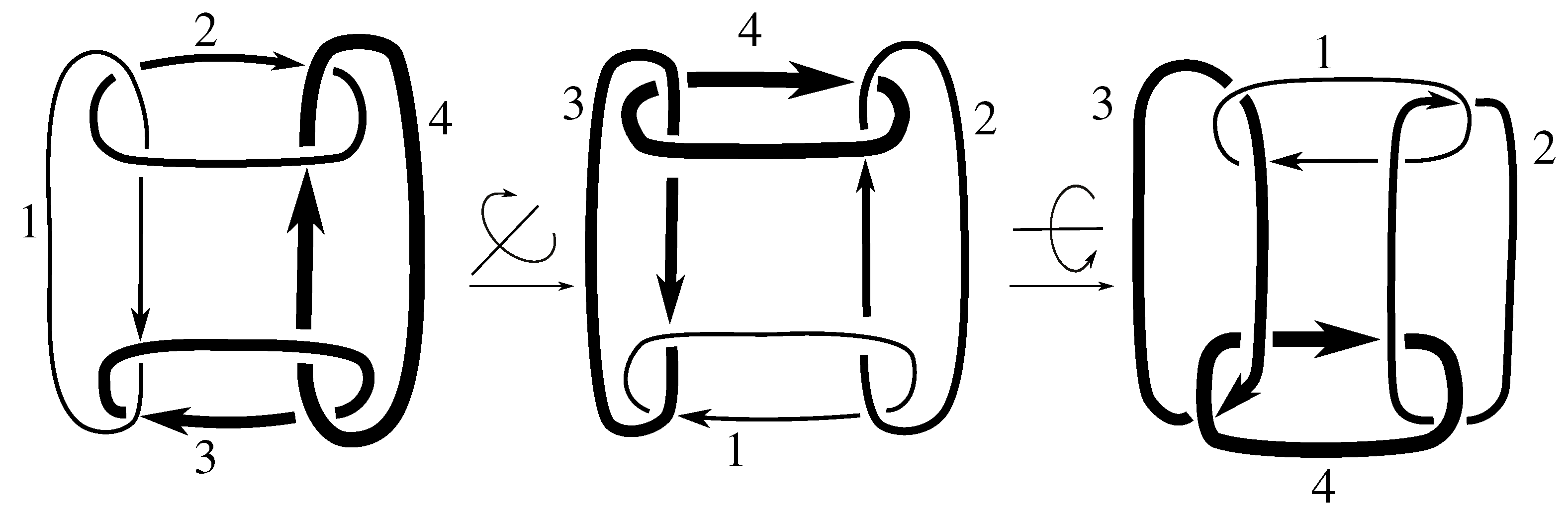

Lemma 7.3 Via the isotopies exhibited in Figure B1, Figure B2, and Figure C10, Figure C11, Figure C12, Figure C13, Figure C14, Figure C15 and Figure C16 in Appendix B.1 and Appendix C.1, the following 17 links have pure exchange symmetry:i.e., belongs to the symmetry group of each of these links. As we determine symmetry groups, we will establish that the remaining 13 links in consideration do not have pure exchange symmetry.

Cerf [

6] states that all prime, alternating two-component links of 8 or fewer crossings are invertible, though this may involve exchanging components. Via the isotopies exhibited in

Figure B3 and

Figure C17,

Figure C18,

Figure C19,

Figure C20,

Figure C21,

Figure C22,

Figure C23 and

Figure C24 of

Appendix B.2 and

Appendix C.2, we extend Cerf’s result to non-alternating links, and we show that the invertibility is pure (

i.e., without exchanging components). To obtain invertibility for

, combine the results of

Figure B4 and

Figure B5, which show that each of its components can be individually inverted.

Lemma 7.4 All 30 prime two-component links with eight or fewer crossings are purely invertible.

We note that the pure exchange and pure invertibility symmetries, corresponding to Whitten elements and , respectively, generate the subgroup of . This implies our first result about link symmetry groups.

Lemma 7.5 Any two-component link, such as those listed in Equation (6), that has both pure exchange symmetry and (pure) invertibility, must have as a subgroup of its symmetry group . By examining signed crossings of a link, we calculate its linking number and self-writhe; if one of these is nonzero, we may rule out some symmetries.

Lemma 7.6. - 1.

If the linking number , then .

- 2.

For L alternating, if the self-writhe , then .

- 3.

For L alternating, if and , then .

Consider the effect of each symmetry operation upon linking number (see Proposition 5.3): mirroring a link or inverting one of its components will swap the sign of the linking number, while exchanging its components fixes the linking number. As for the self-writhe of a link, it is fixed by inverting any component or exchanging the two components; however, mirroring a link swaps the sign of .

Thus, the elements of that will swap the sign of a linking number are precisely those of the form with . If the linking number is nonzero, these cannot possibly produce a link isotopic to the original link L, so these eight elements are not part of . The remaining eight symmetry elements form , which proves the first assertion.

Self-writhe is an invariant of reduced diagrams of alternating links, and any symmetry operation which mirrors the link will swap the sign of . If the self-writhe is nonzero, then no element which mirrors, i.e., , can lie in . The remaining elements form .

The last assertion follows as an immediate corollary of the first two. If both hypotheses are satisfied, then .

Lemma 7.7 Let L be a two-component link.

- 1.

If L is purely invertible, then .

- 2.

If the components of L are different knot types, then .

- 3.

If both hypotheses above are true, and

- (a)

if , then is either or .

- (b)

if L is alternating and , then is either or .

If the components of L have different knot types, then no exchange symmetries are permissible; the permutation never appears in . Hence the symmetry group is contained in the “No exchanges” group .

Combining these two results with the previous lemma proves the third assertion. If the linking number is nonzero and the components of L have different knot types, then . If L is also purely invertible, then . This implies that the order of equals 2 or 4, so it is either or .

If instead self-writhe is nonzero and the first two hypotheses hold, then . This implies that the order of equals 2 or 4, so it is either or .

With these five lemmas in hand, we are now prepared to begin proving Theorem 7.2, which we treat by each symmetry group.

7.2.1. Links with Symmetry Group

Claim 7.8 Links and have symmetry group .

All of these links are purely invertible, so . Also, all of them have components of different knot types and nonzero linking numbers; thus by Lemma 7.7, their symmetry groups are either or .

Three of the alternating links have nonzero self-writhe, so we apply Lemma 7.7 again. We conclude that they have only the purely invertible symmetry, and is their symmetry group.

For the remaining three links in this case

, consider the action of the Whitten element

. We consider the Jones polynomials of

L and

. They are unequal, as demonstrated below, which implies

is not isotopic to

L. Thus

, so it must be

.

7.2.2. Links with Symmetry Group

Claim 7.9 Links and have symmetry group .

All five of these links appear in our list Equation (

6) of pure exchange symmetry links; also, they all are purely invertible and have nonzero linking numbers. Lemmas 7.3 and 7.6 imply that

.

For each link, the Conway polynomials differ for

L and

, where

. Thus each link cannot have

as its symmetry group and must therefore have

. We display the Conway polynomials in

Table 11 below.

Claim 7.10 Links and have symmetry group .

These links have both pure exchange and pure invertibility symmetries; they also have nonzero self-writhes and linking numbers. By Lemmas 7.3 and 7.6, their symmetry group must be .

7.2.3. Links with Symmetry Group

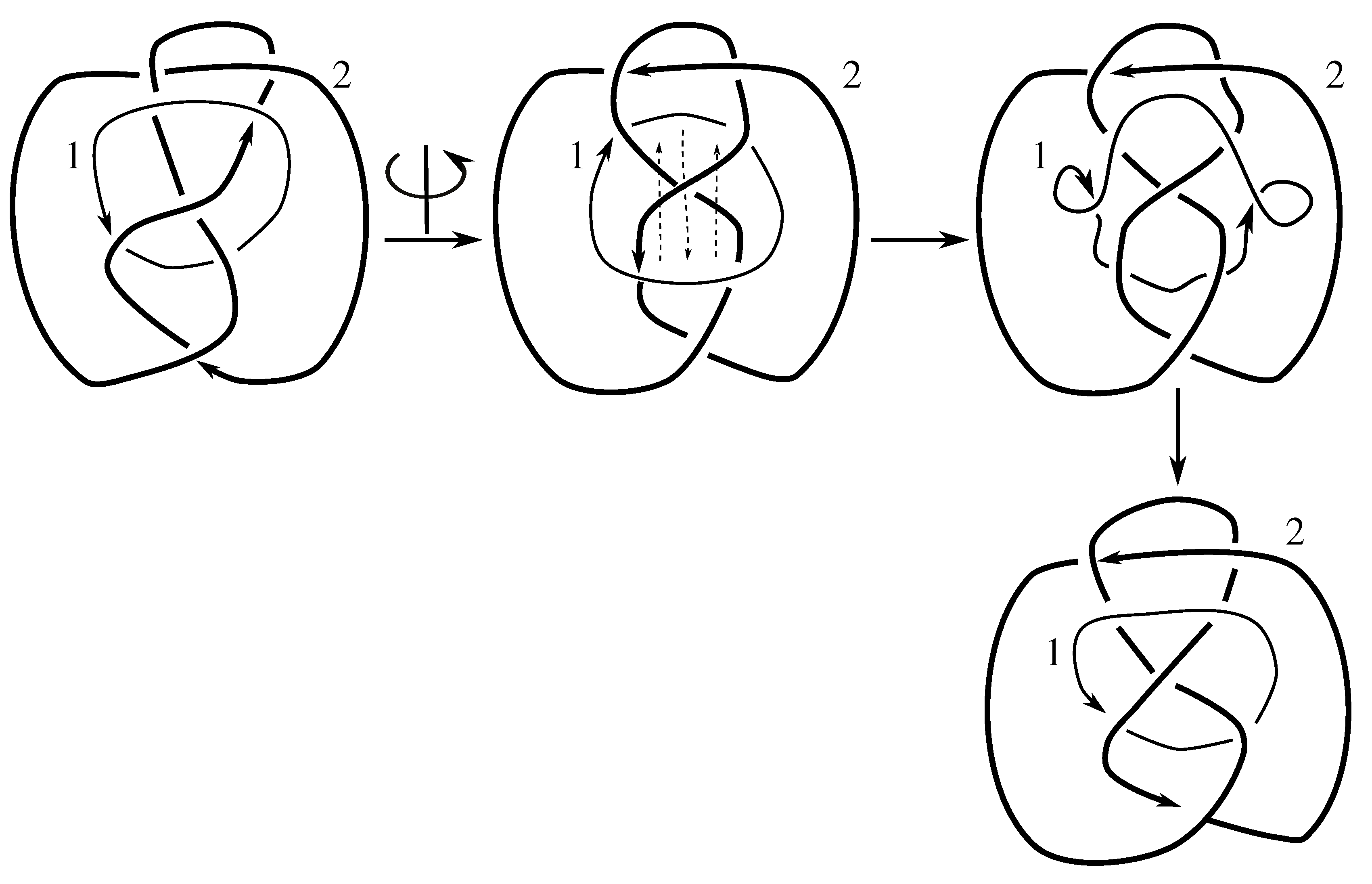

Claim 7.11 Links and have symmetry group .

These links are purely invertible, comprised of different knot types, and have self-writhe ; thus, Lemma 7.6 implies .

Figure C3 and

Figure C7 exhibit an isotopies which shows that

for each link, which means

is their symmetry group.

Claim 7.12 Links and have symmetry group .

These links are purely invertible and comprised of different knot types; thus, Lemma 7.6 implies .

First, we use the Jones polynomial to rule out mirror symmetry,

i.e., the element

does not lie in

. That means order of the subgroup

is between 2 and 7; hence it is either a 2 or 4 element subgroup. Here are the Jones polynomials:

Next, for each link we depict an isotopy which reverses the orientation of just one component, i.e., we show either or lies in . This means is the symmetry group for these three links.

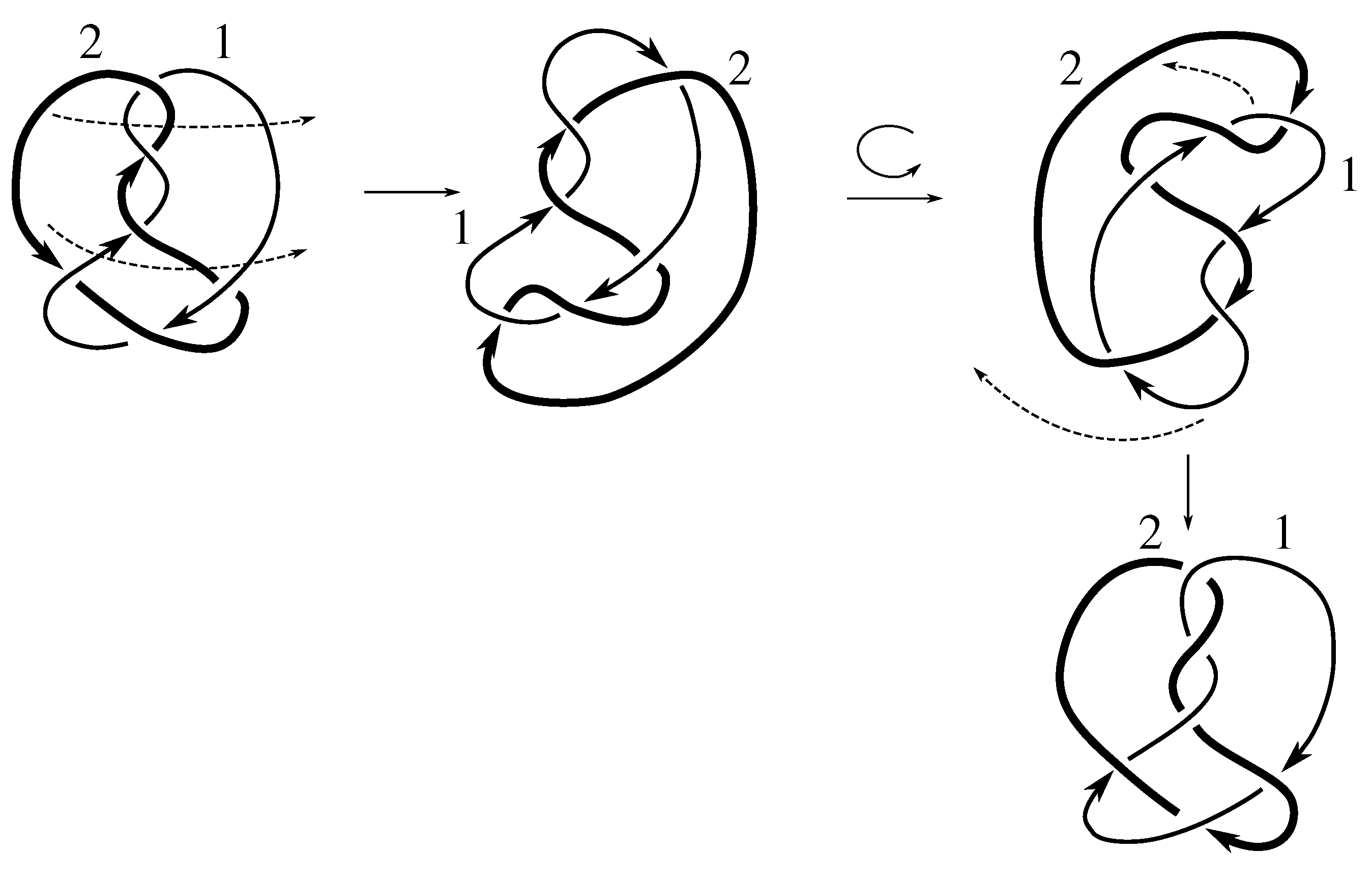

Claim 7.13 Links and have symmetry group .

These links are purely invertible and have nonzero self-writhe; thus Lemma 7.6 implies .

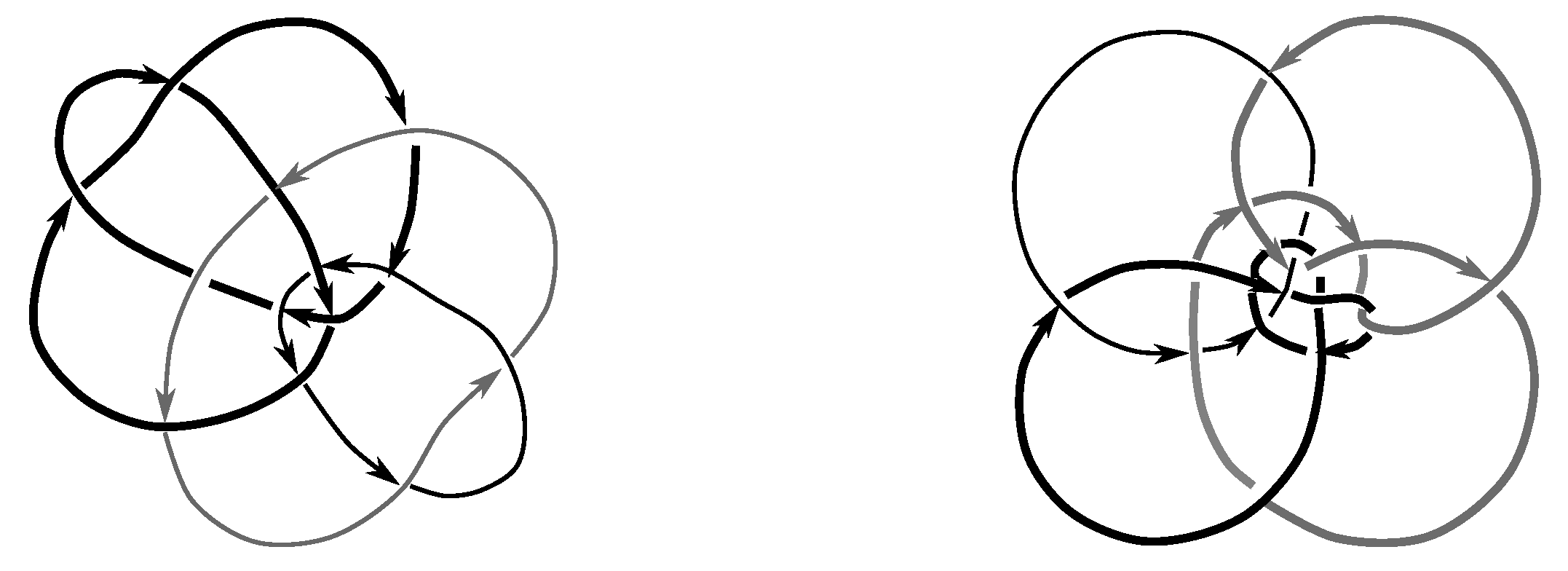

We take the satellites,

of the first and second component of

L, for

, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, and then compute the Jones polynomial for each.

Since the Jones polynomials of the two different satellites are not equal for either link L, we have that L is not isotopic to for by Lemma 6.3. Thus, .

Figure C4 and

Figure C8 exhibit isotopies that show

for both of these links. Therefore, we conclude

for these two links.

7.2.4. Links with Symmetry Group

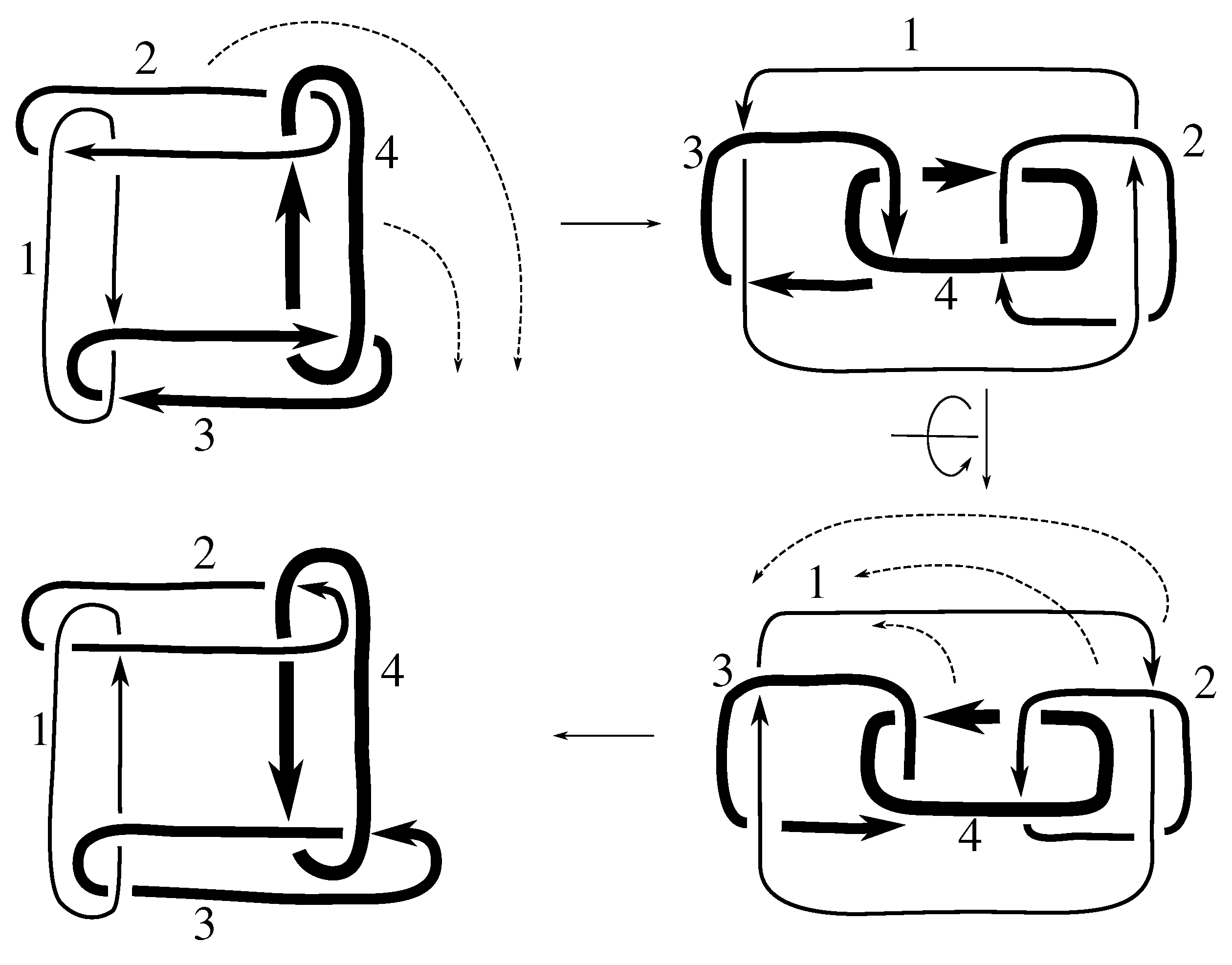

Claim 7.14 Links and have symmetry group .

These two links have the pure exchange and pure invertibility symmetries, and their self-writhes are nonzero; thus Lemma 7.6 implies

. We show, in

Figure B4 and

Figure B5, that each symmetry group includes either

or

, neither of which is an element of

. Therefore, we conclude

for these two links.

7.2.5. Links with Symmetry Group

Claim 7.15 Links and have symmetry group .

These three links have the pure exchange and pure invertibility symmetries, and their linking numbers are nonzero; thus Lemma 7.6 implies .

Figure C1,

Figure C2, and

Figure C5 display the isotopies which show

lies in the symmetry group for each of these three links. Since this element is not in

, we may conclude all three links have symmetry group

.

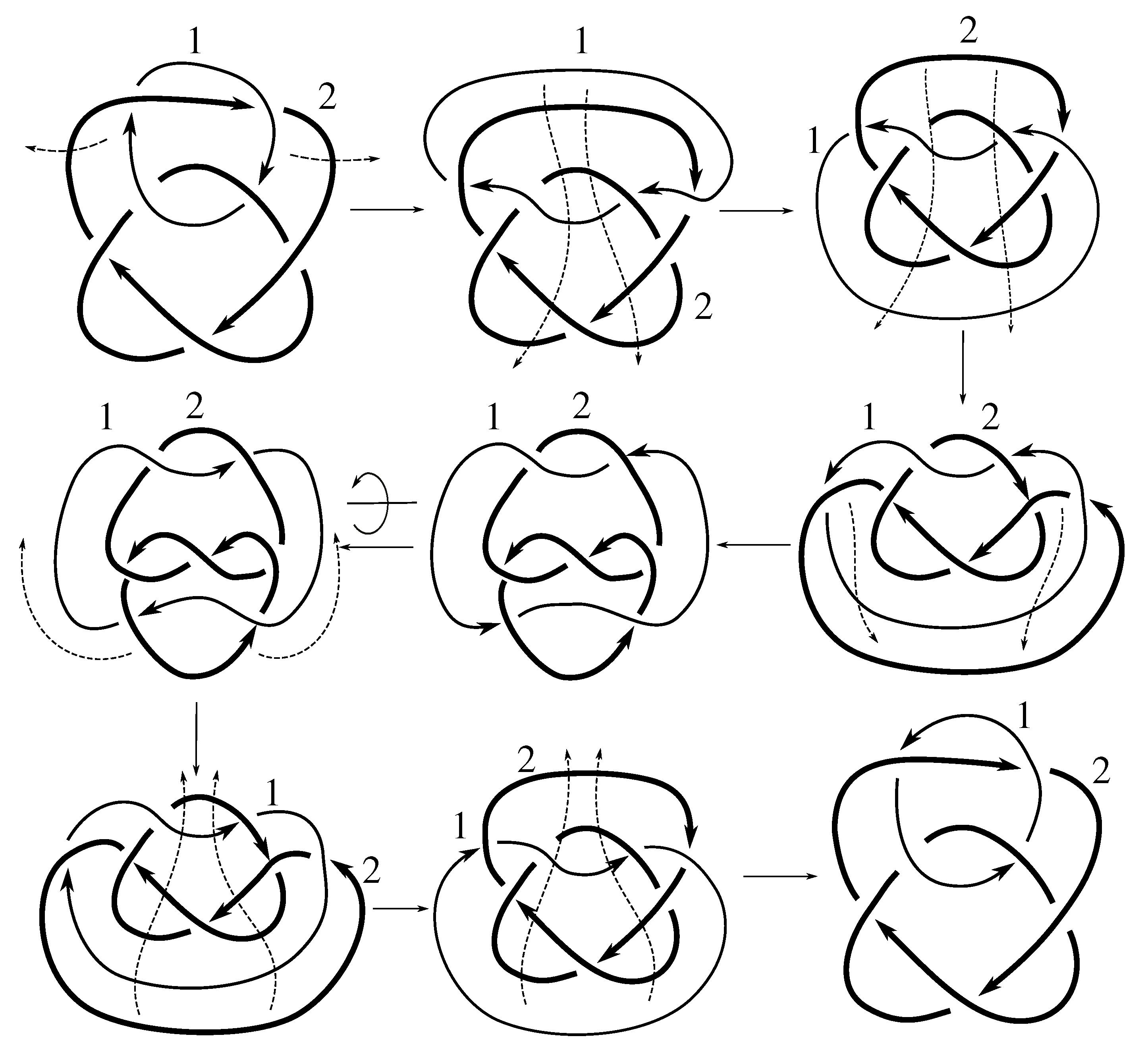

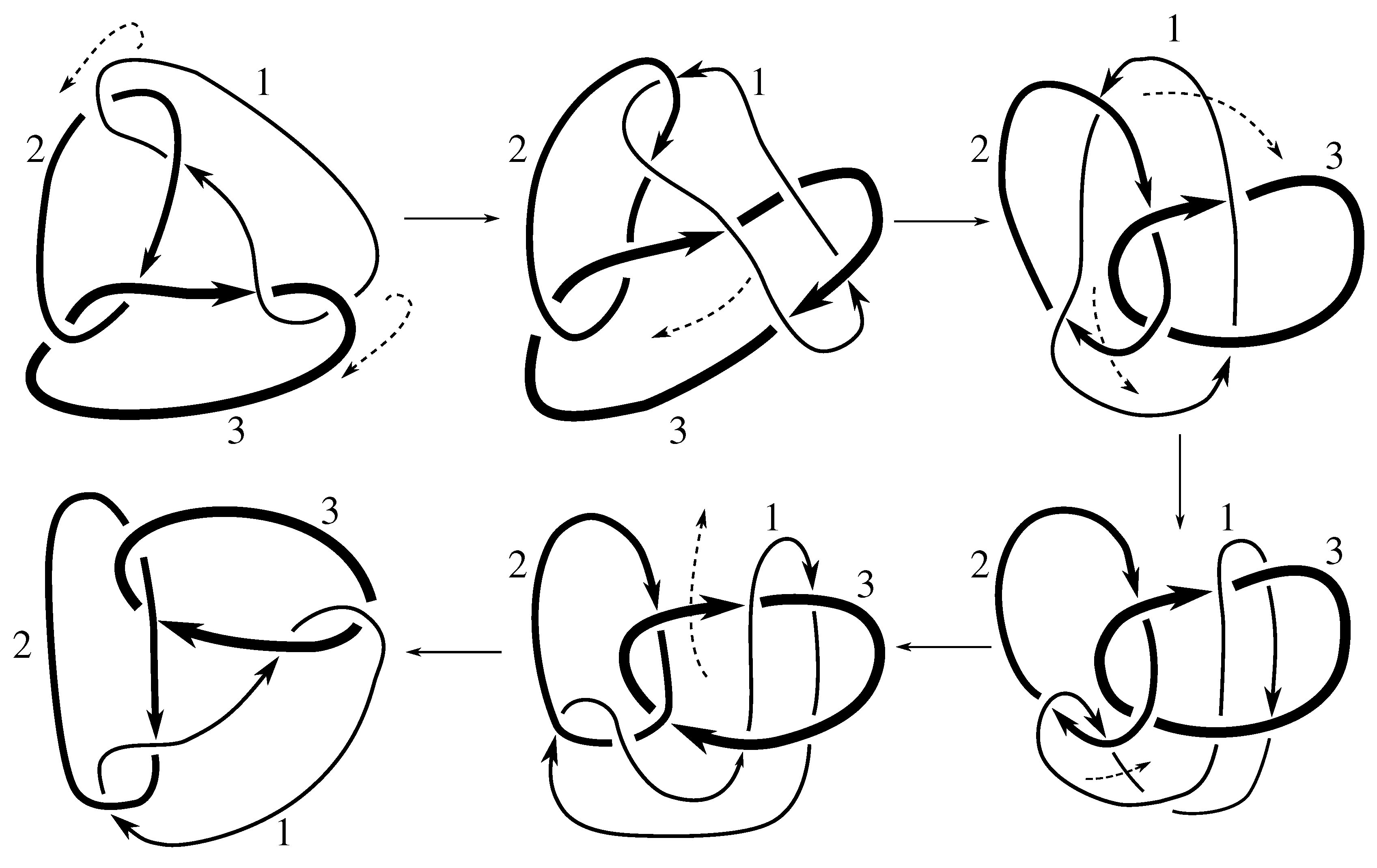

8. Three-Component Links

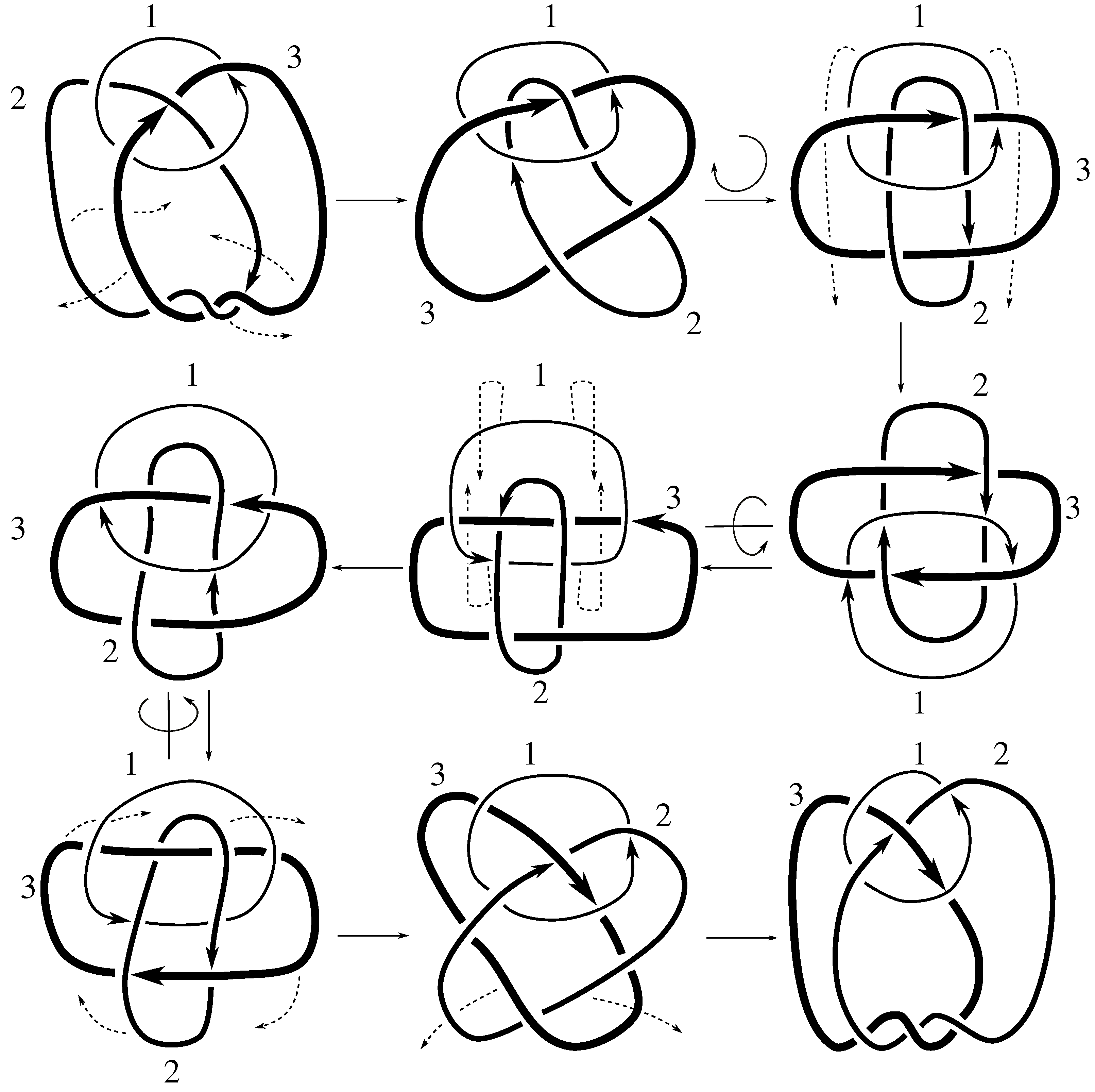

There are 14 three-component links with 8 or fewer crossings. In this section, we determine the symmetry group for each one;

Table 5 summarizes the results. We obtain 11 different symmetry subgroups inside

, which represent 7 different conjugacy classes of subgroups (out of the 131 possible).

For each link, our first task is to calculate the linking matrix. Then, we utilize

Table 12 to determine the stabilizer of this matrix within

; we know that the symmetry group

must be a subgroup of this stabilizer. From there, we proceed by ruling out other elements using polynomial invariants and by exhibiting isotopies to show that certain symmetries do lie in

until we can discern the symmetry group.

Here are the results, listed in terms of generators for each group. We use the following notation for common group elements:

PI, for pure invertibility, i.e., the element

PE, for having all pure exchanges, i.e., all elements where

We note that all but two of these links are purely invertible, even though PI might not be part of a minimal set of generators. Neither the Borromean rings or the link are purely invertible. Both of these links are, however, invertible. The Borromean rings can be inverted using any odd permutation p, i.e., they admit the symmetry ; the link is invertible using .

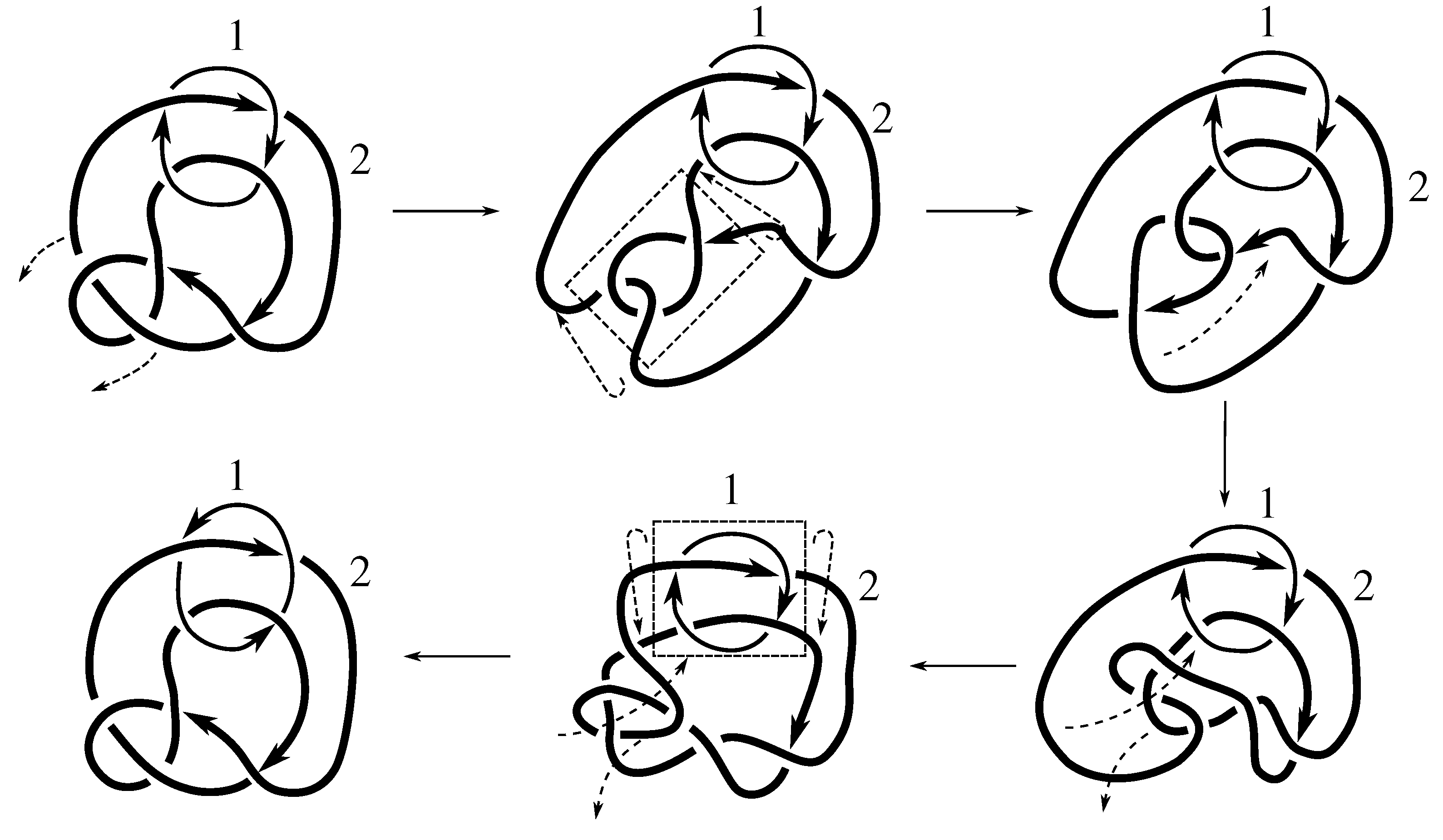

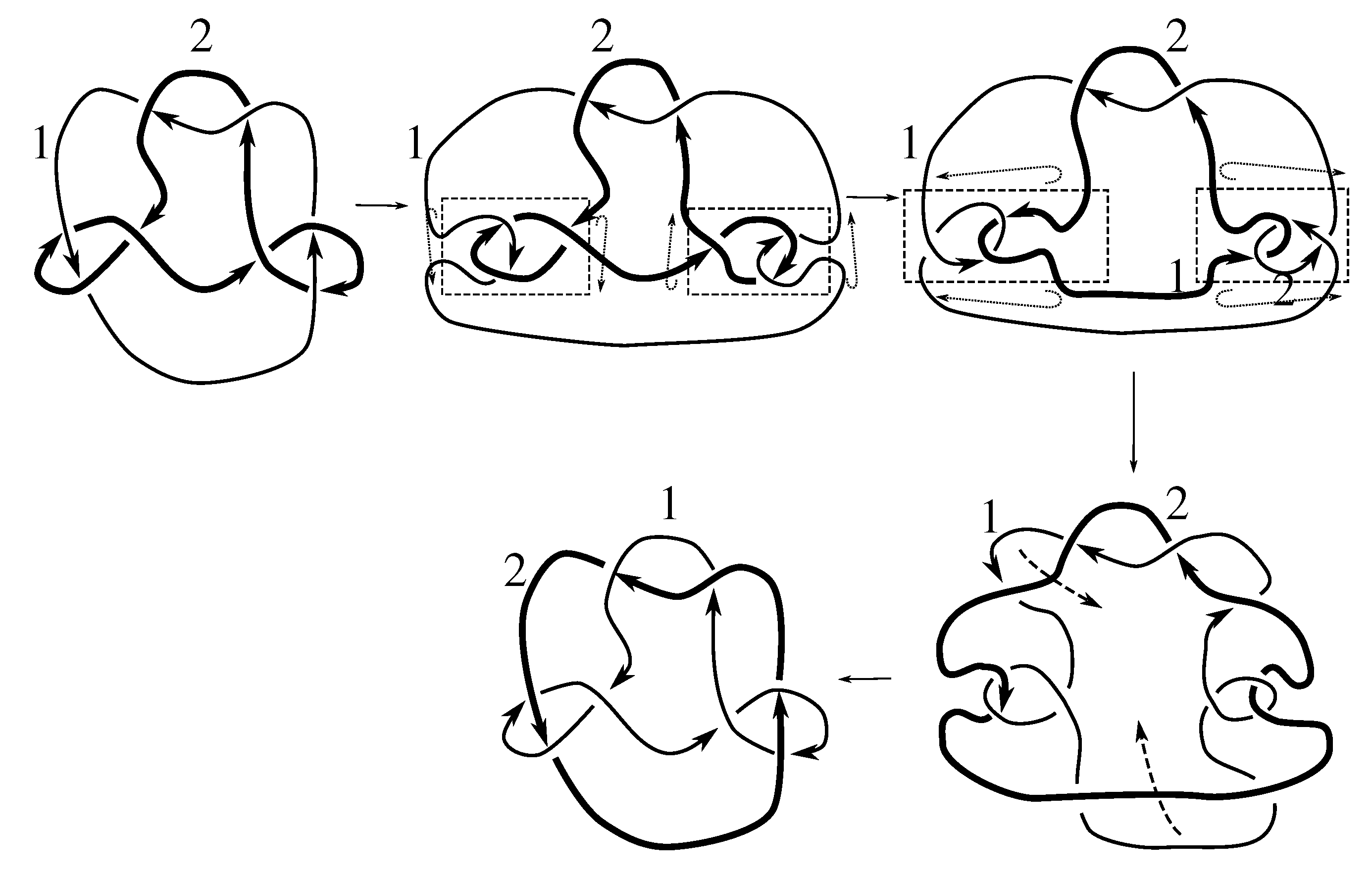

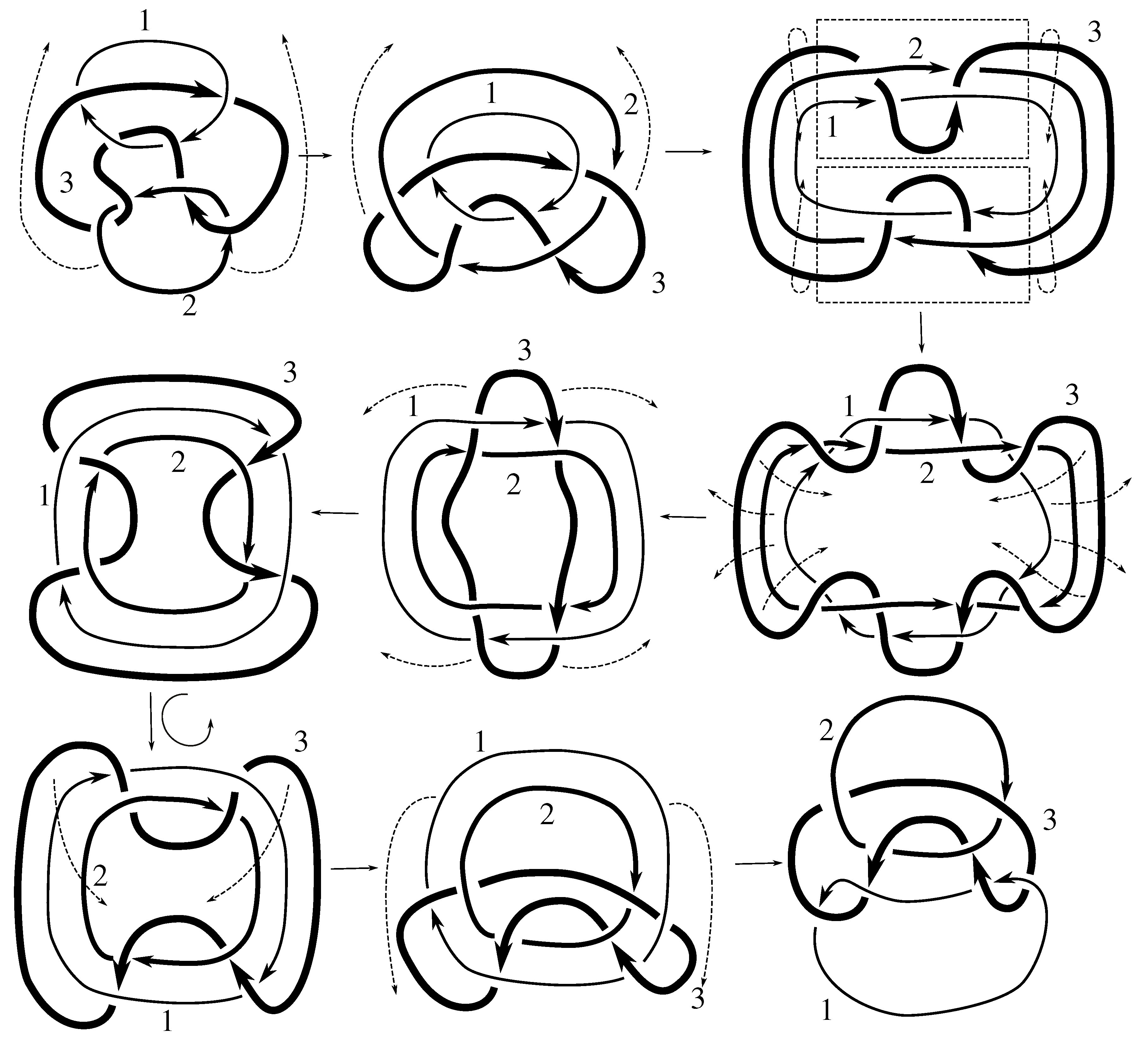

Claim 8.1 The subgroup is the 12 element group isomorphic to generated by pure exchanges and pure invertibility.

The linking matrix for

is

which is in the standard form

. We know that

is a subgroup of the stabilizer of this matrix under the action of

on linking matrices. Consulting

Table 12, we see that this stabilizer is the group in the claim. We must now show that all these elements are in the group.

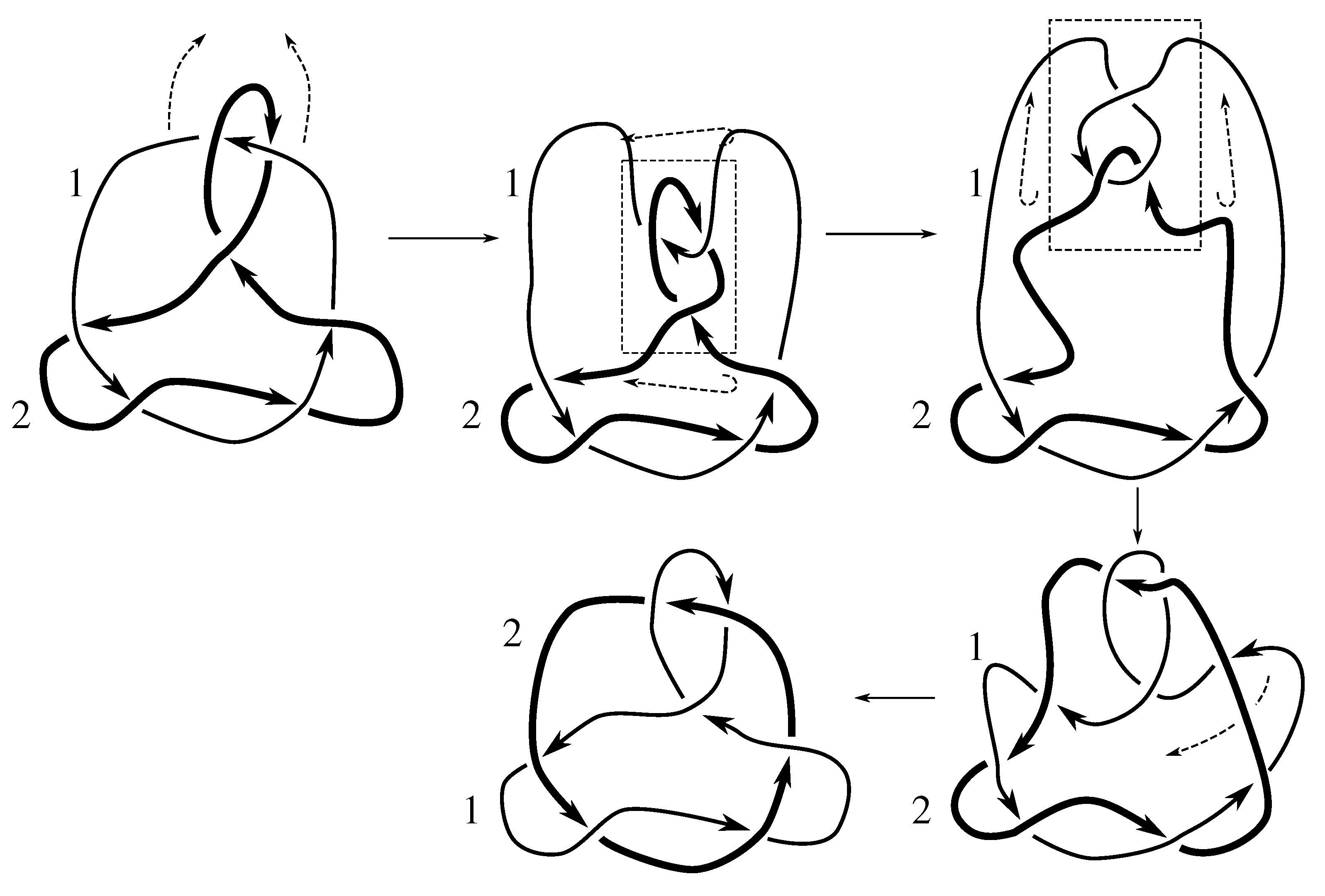

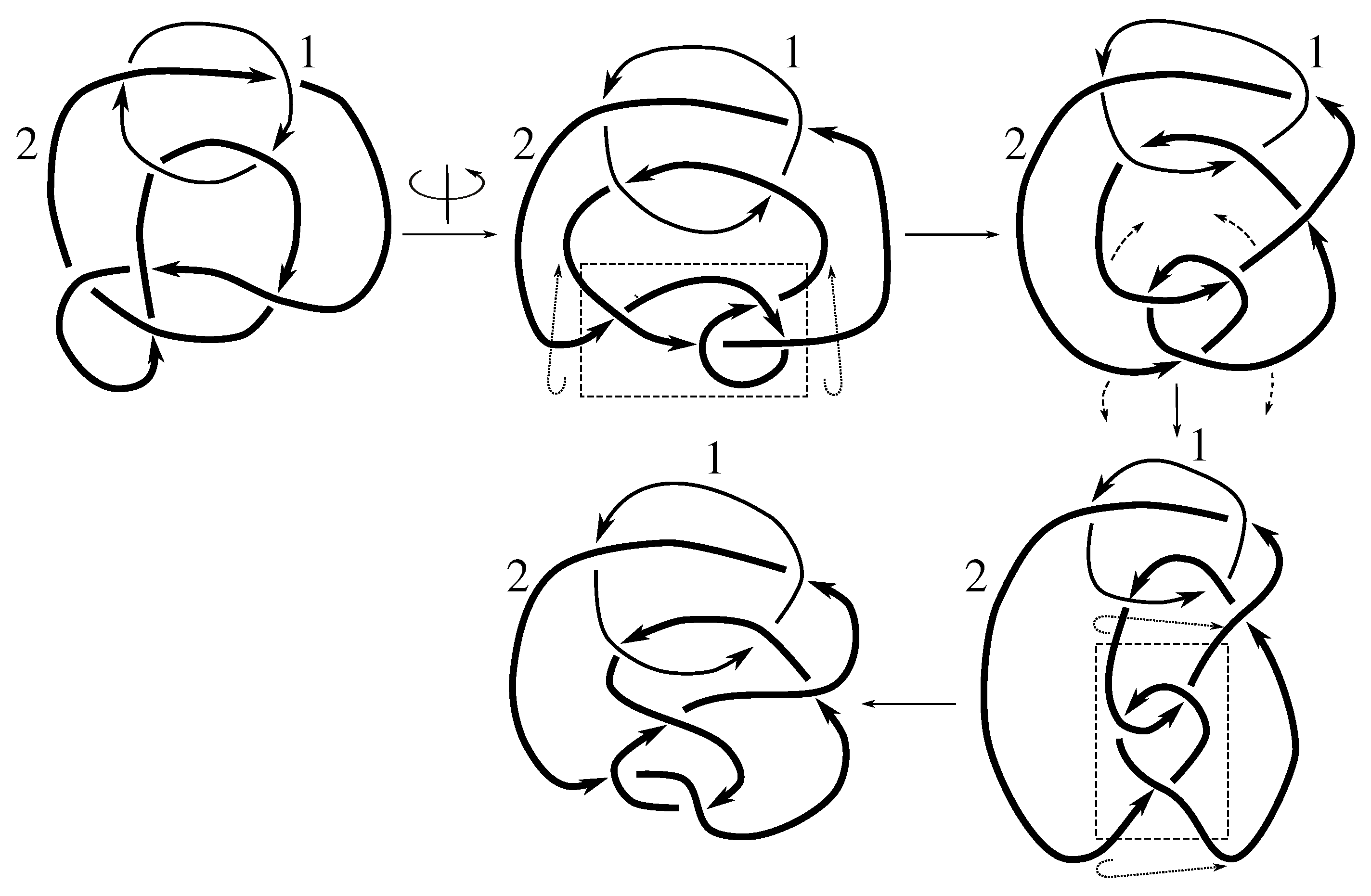

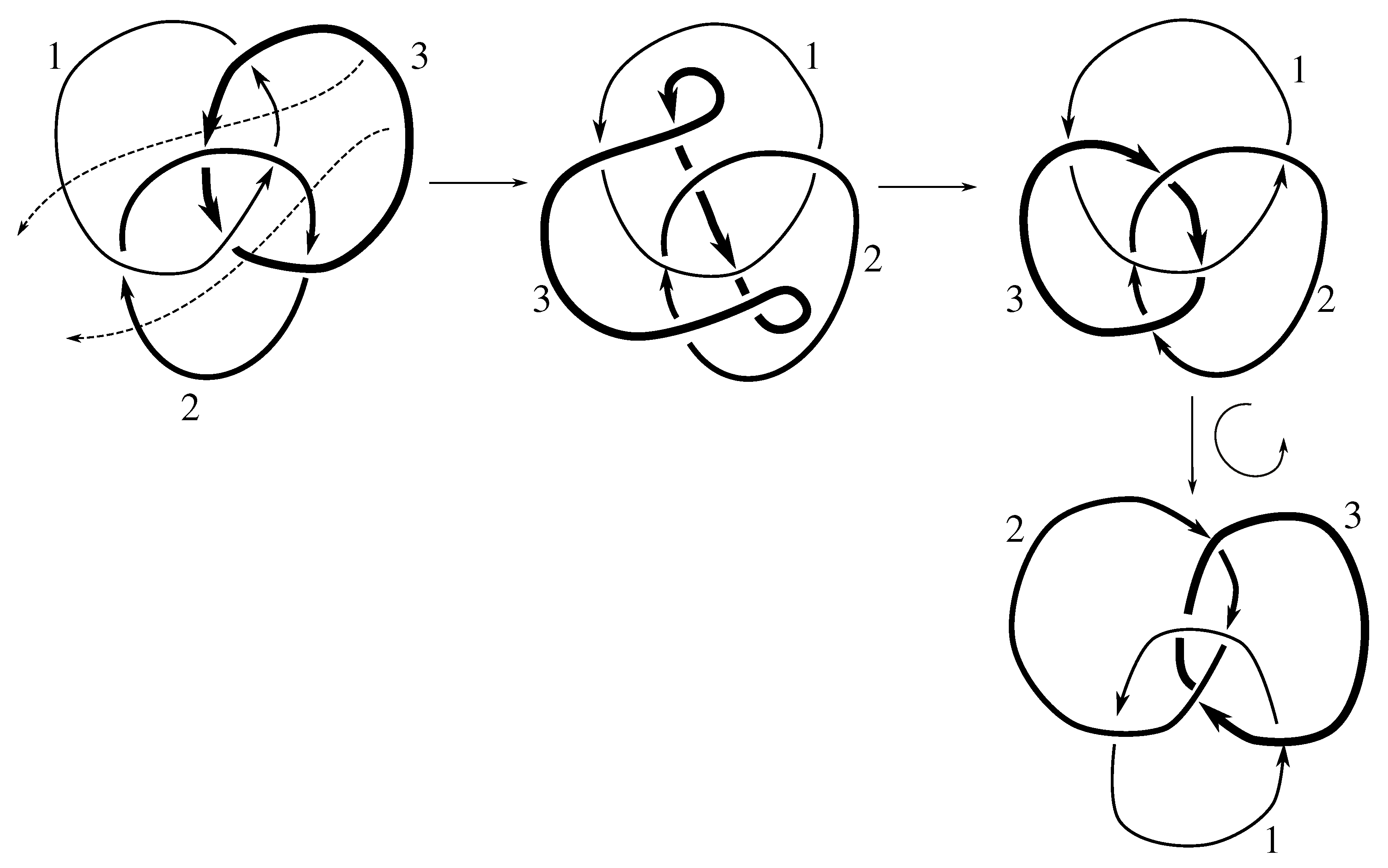

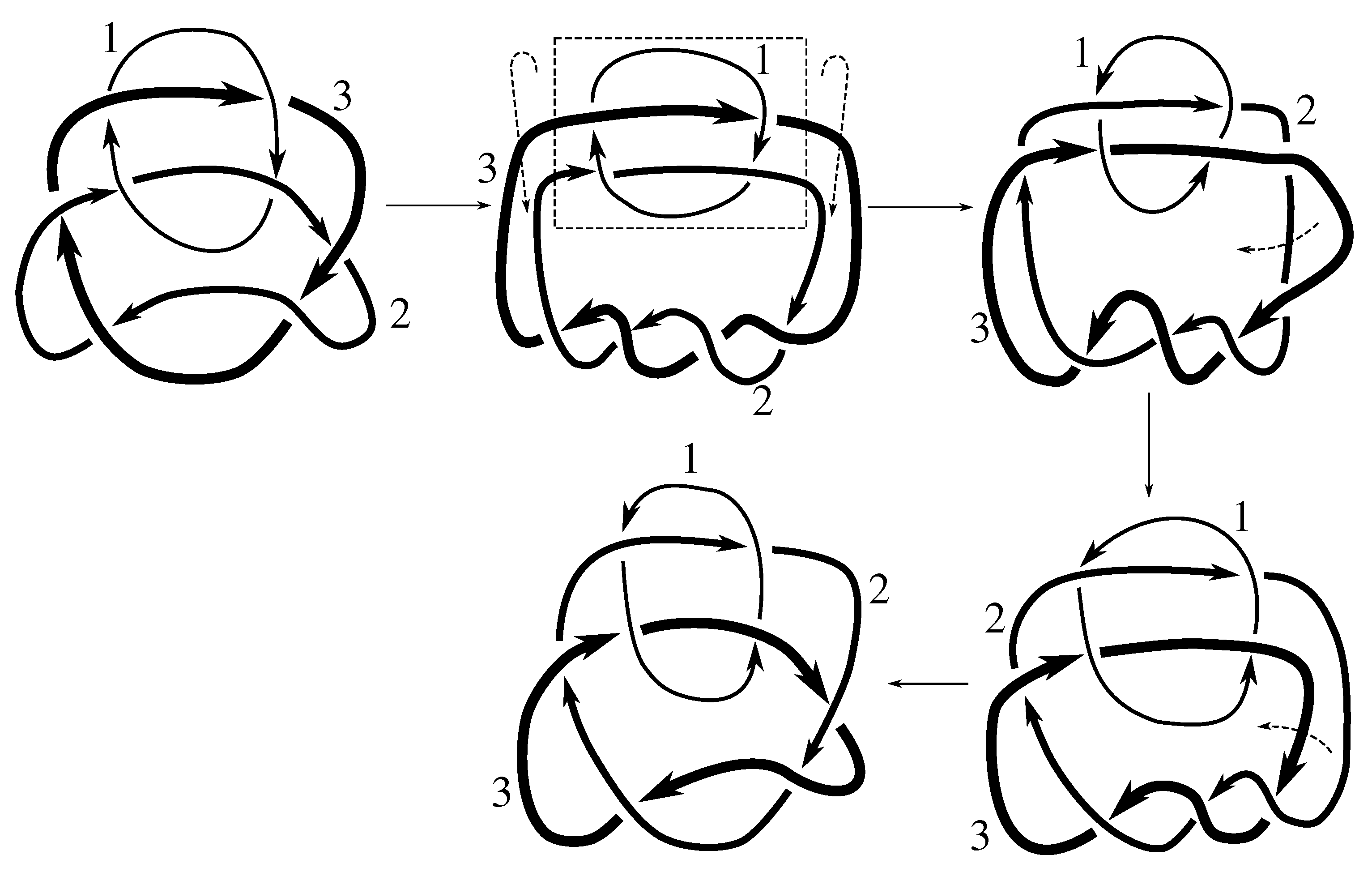

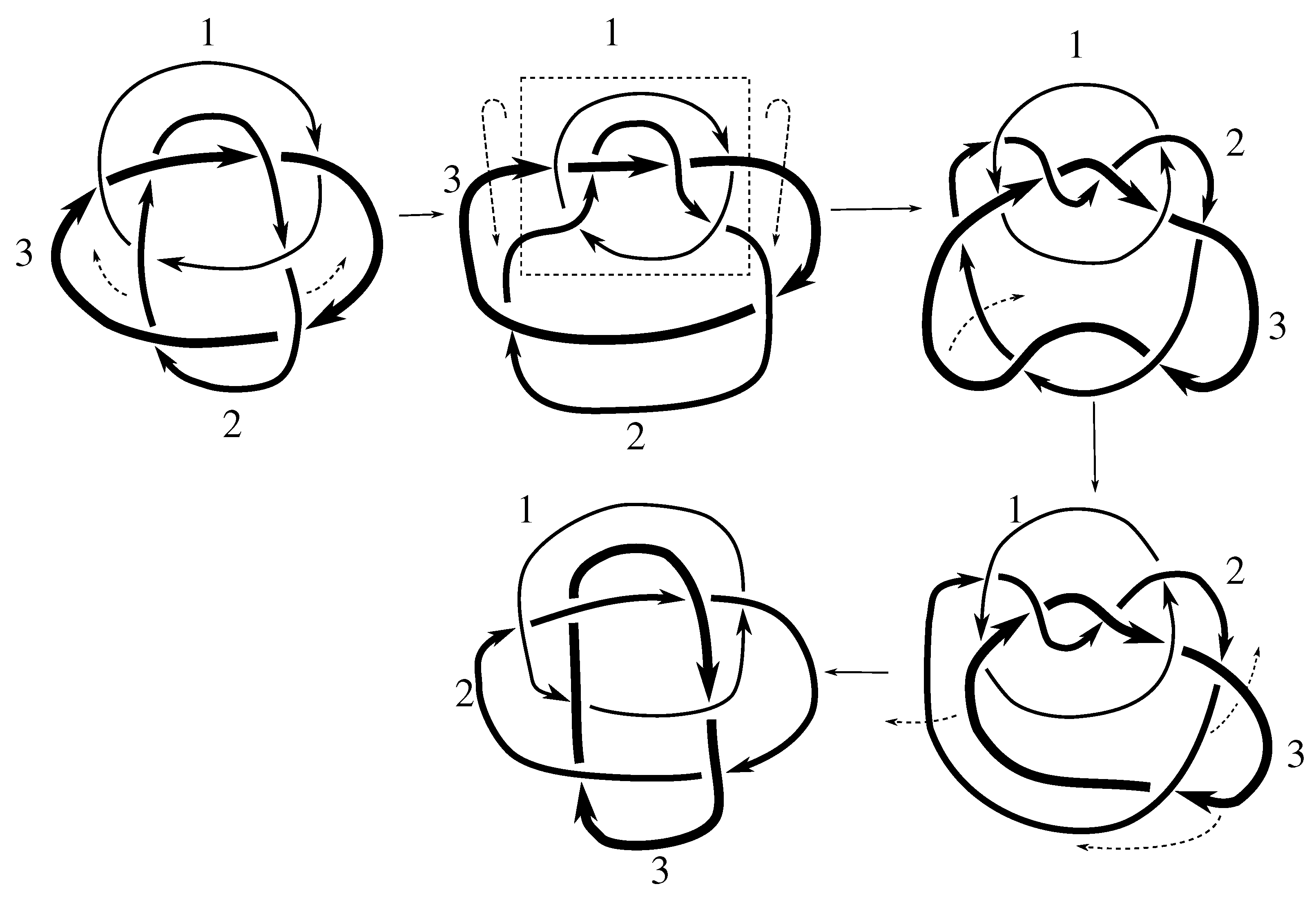

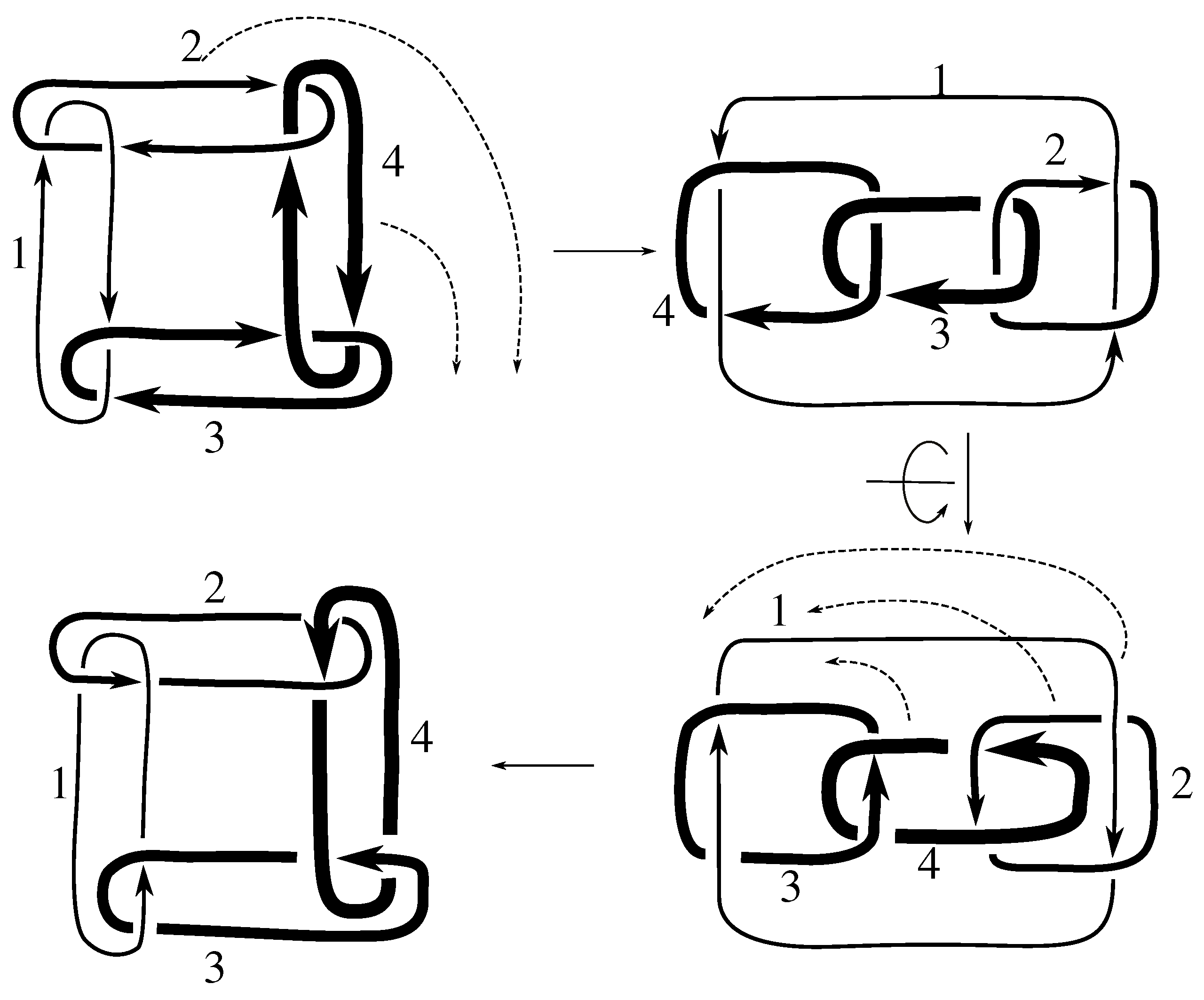

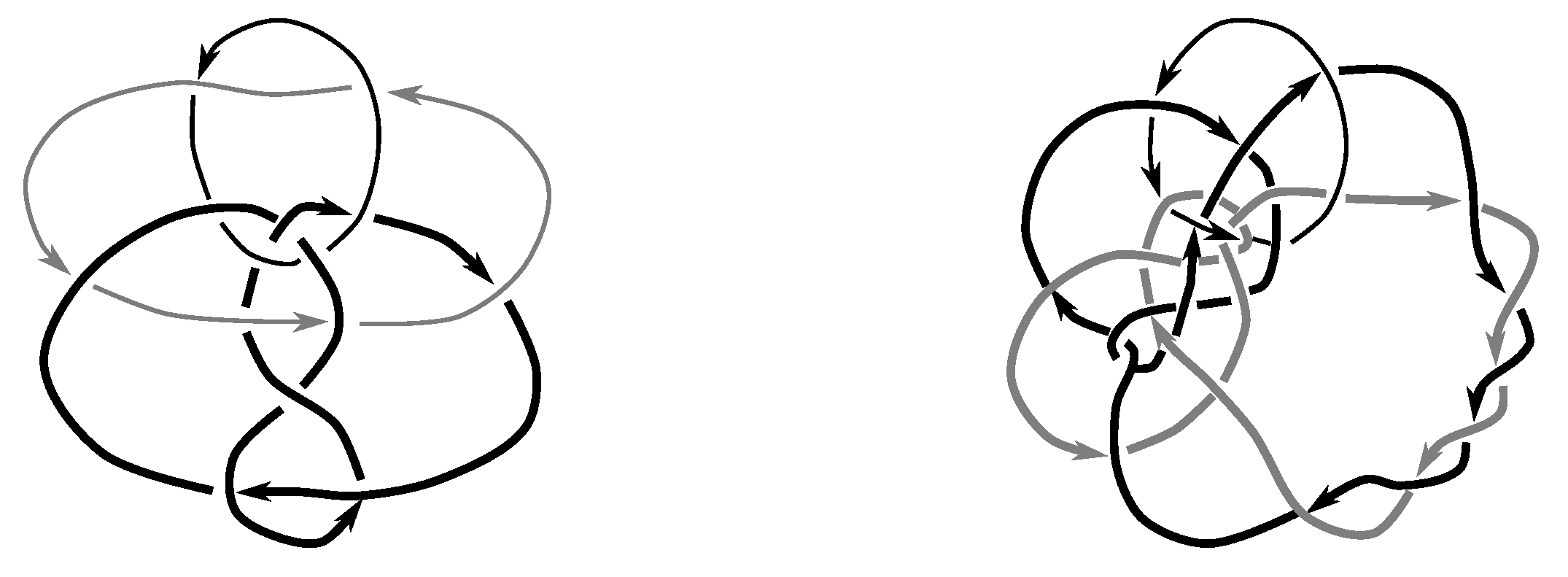

Figure B2 and

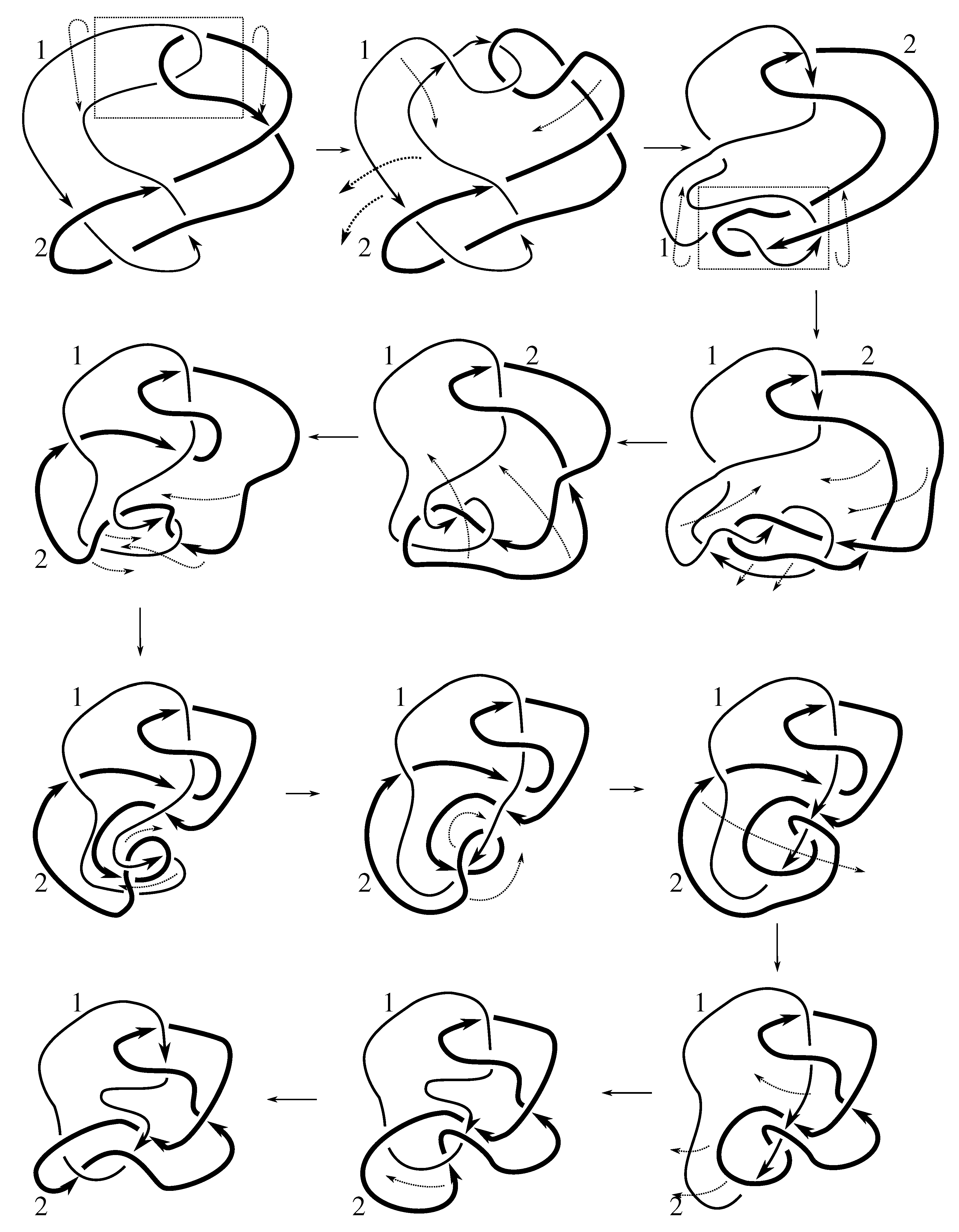

Figure D2 show that

Since any 3-cycle and 2-cycle generate

, we have the rest of the pure exchanges as well.

Figure D1 shows that this link is purely invertible, completing the proof.

Claim 8.2 The subgroup is the 48 element group where is in the group if either

- (a)

and p is an even permutation, or

- (b)

and p is odd.

Figure B5,

Figure D3, and

Figure D4 tell us that

contains the elements

which clearly obey the rules in the claim. In fact, they generate a group of 48 such elements. Since the order of

must divide

, it is either these 48 elements or it is all of

. But in [

21], Montesinos proves that

is not purely invertible. Thus,

cannot be in

, which completes the proof.

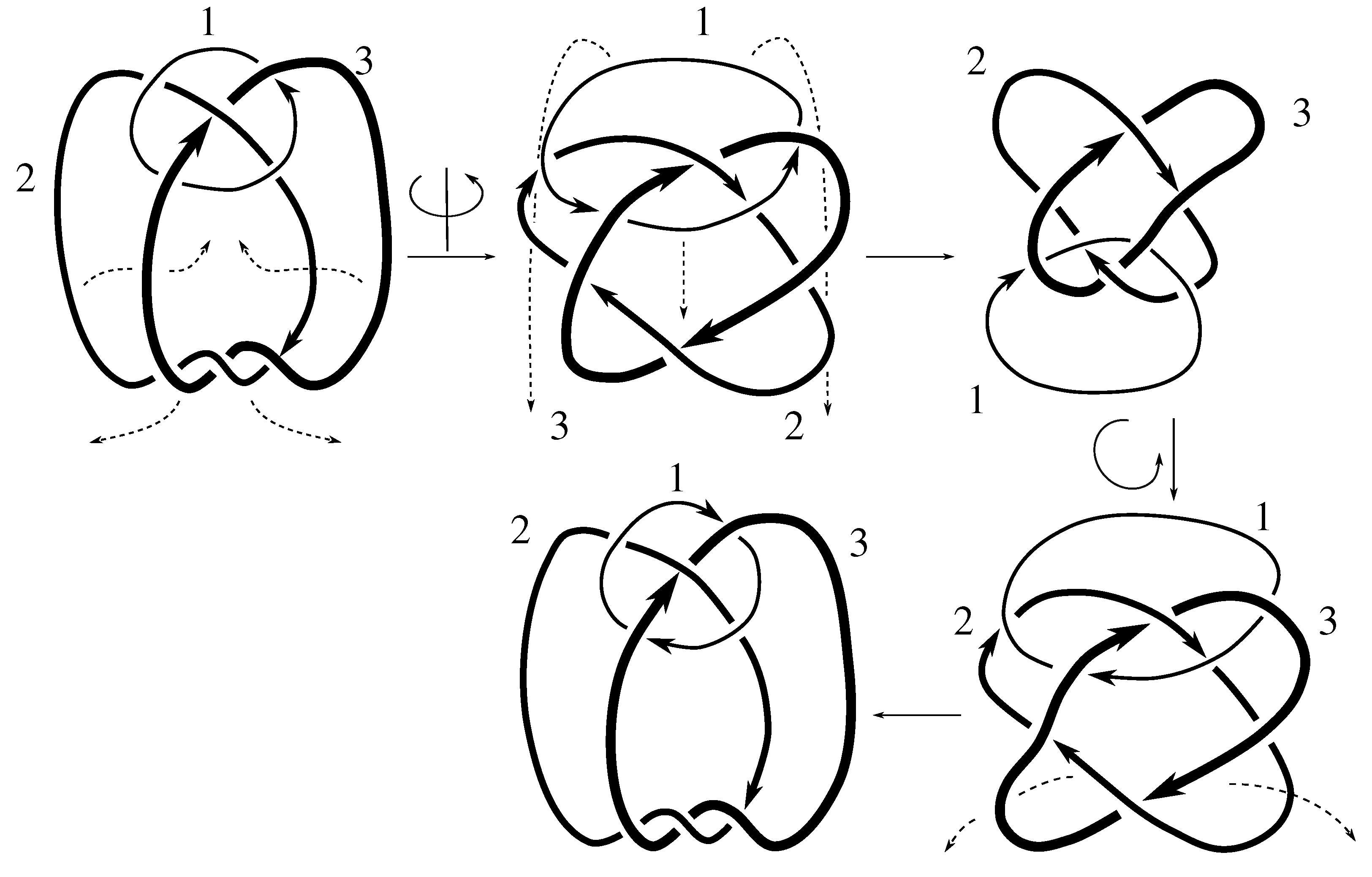

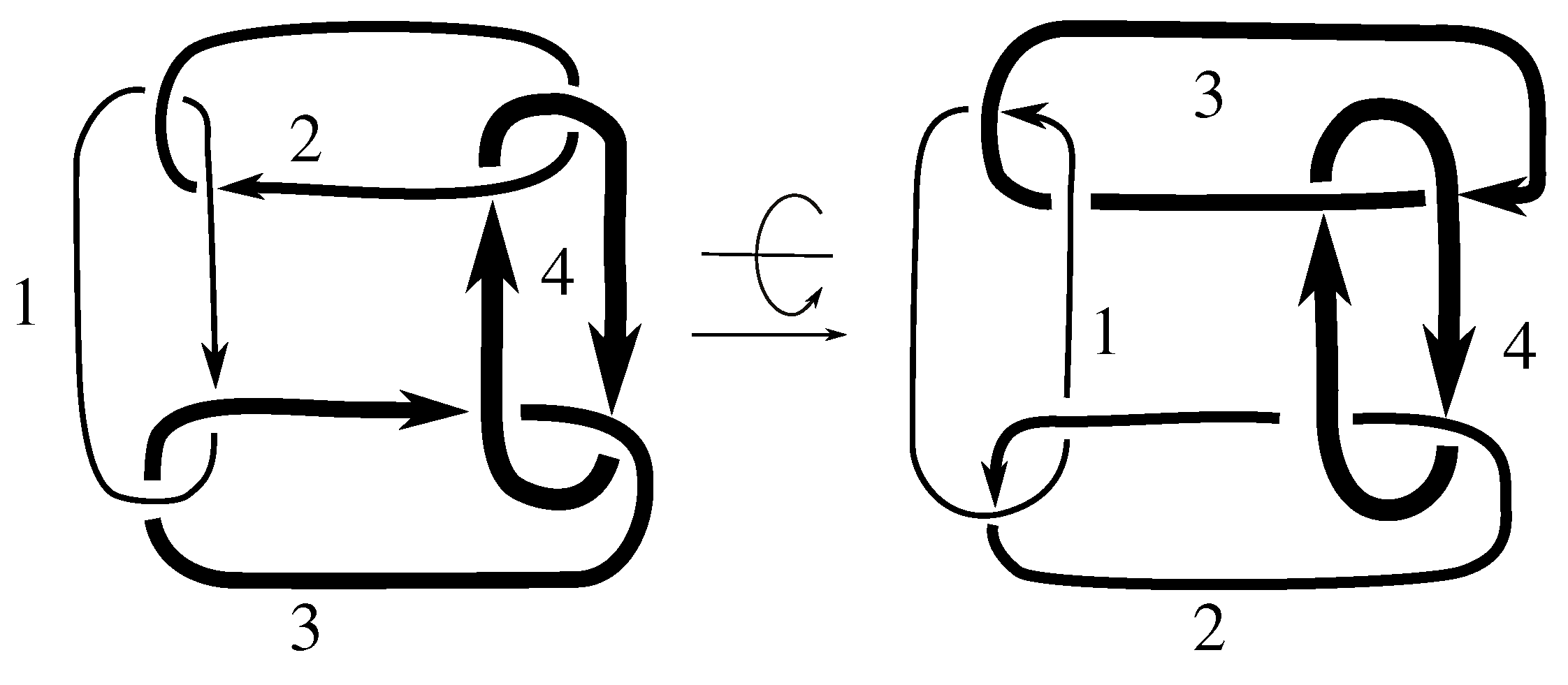

Claim 8.3 The subgroup is the 12 element group isomorphic to given by .

Figure D5 and

Figure D6 imply that

contains

These three elements generate the 12 element group of the claim. Now the linking matrix for

is

which is in the standard form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that this means

divides 12, the order of the stabilizer. Since we already have 12 elements in the symmetry group, it must equal the stabilizer, which completes the proof.

Claim 8.4 The subgroup is the 12 element subgroup isomorphic to that is conjugate to by .

The linking matrix for

is

which corresponds to the triple

and has the same orbit type as

. Thus, the stabilizer of this linking matrix is a 12 element group conjugate to the stabilizer

by

.

Figure D7 and

Figure D8 show that

These elements generate a 12 element group, so this stabilizer is the entire symmetry group of

, as claimed. We note that this stabilizer was worked out explicitly as Example 5.7.

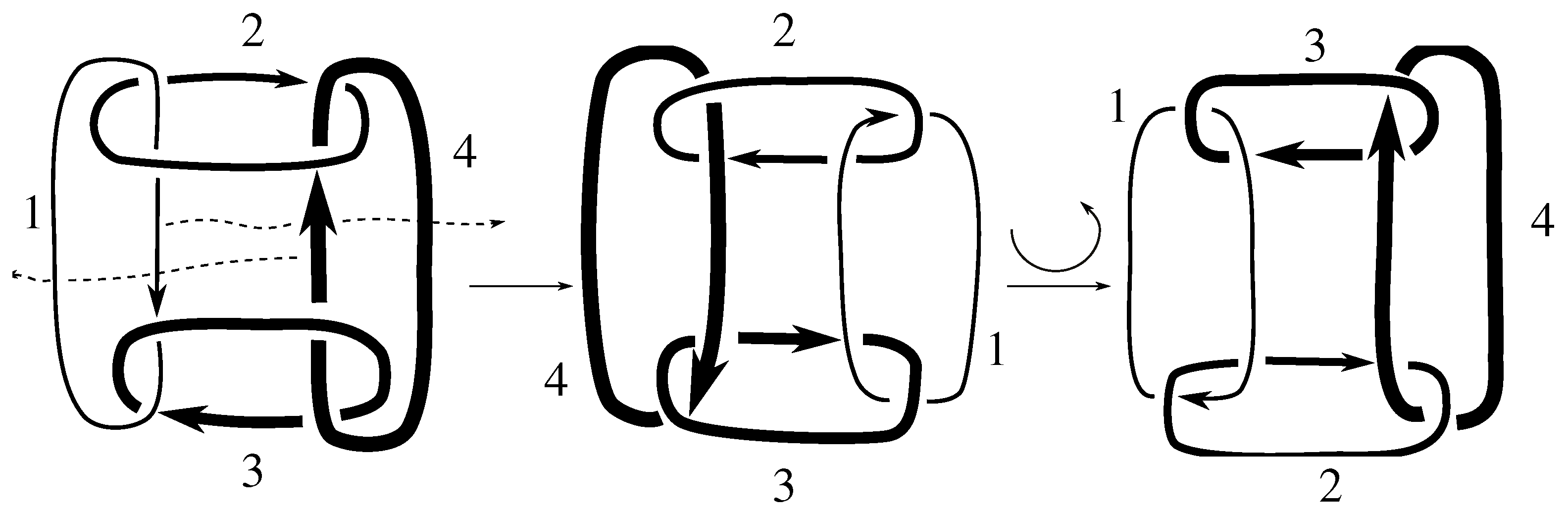

Claim 8.5 The subgroup is the 4 element group isomorphic to generated by pure invertibility and .

The linking matrix for

is

which is in the standard form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that the stabilizer of this linking matrix in

has order 4. But

Figure B3 and

Figure D9 show stabilizer elements

which means that we also have

. Therefore these three elements, plus the identity, must form the symmetry group

.

Claim 8.6 The subgroup is the 4 element group isomorphic to generated by the pure exchange and pure invertibility.

The linking matrix for

is

which is in the standard form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that the stabilizer of

has order 4.

Figure B4 and

Figure D10 show

and these generate the 4 element subgroup of the claim, which equals the stabilizer.

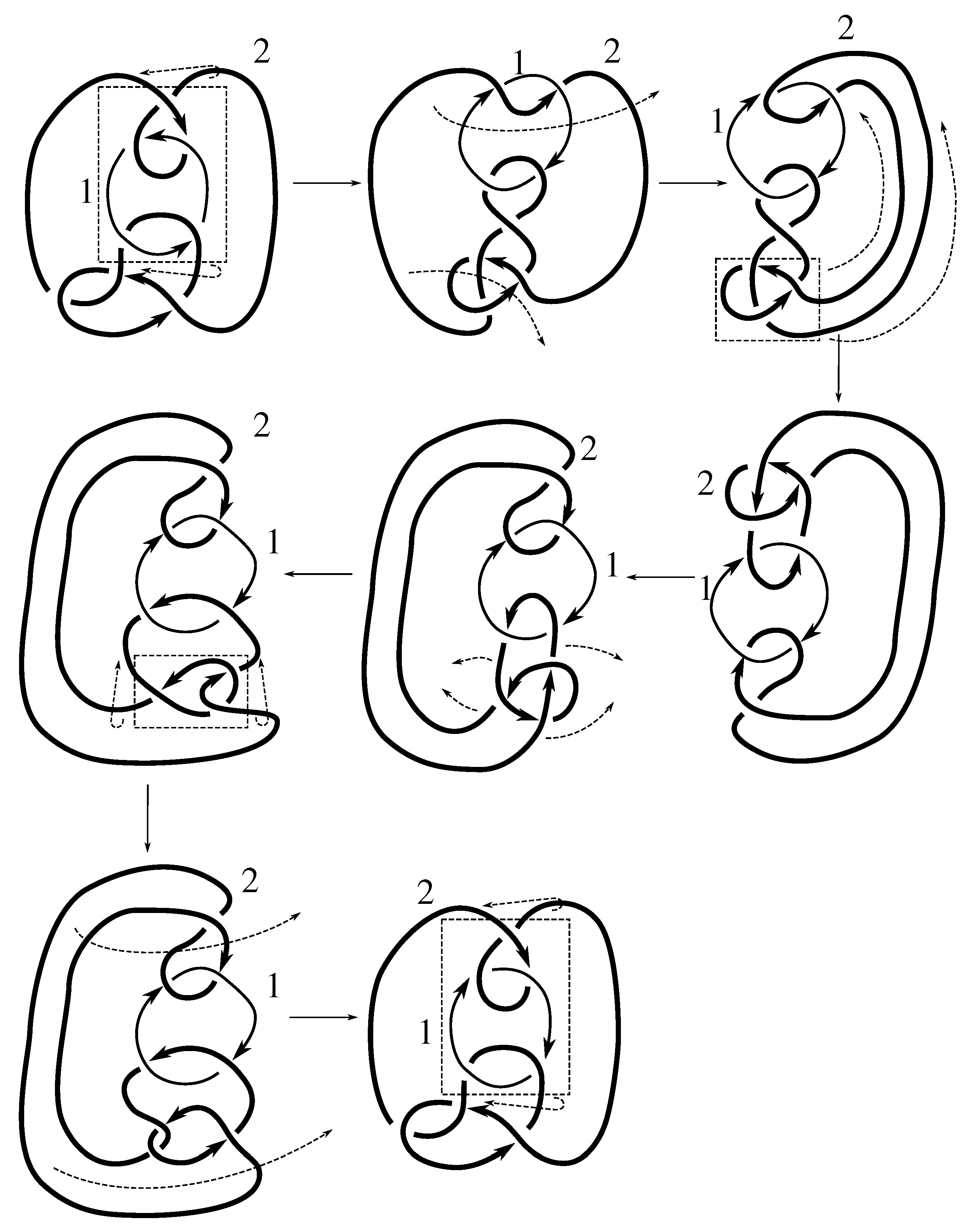

Claim 8.7 The subgroup is the 12 element group isomorphic to generated by pure exchanges and pure invertibility.

The linking matrix for

is

which is in the form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that the stabilizer of

has order 12, and hence

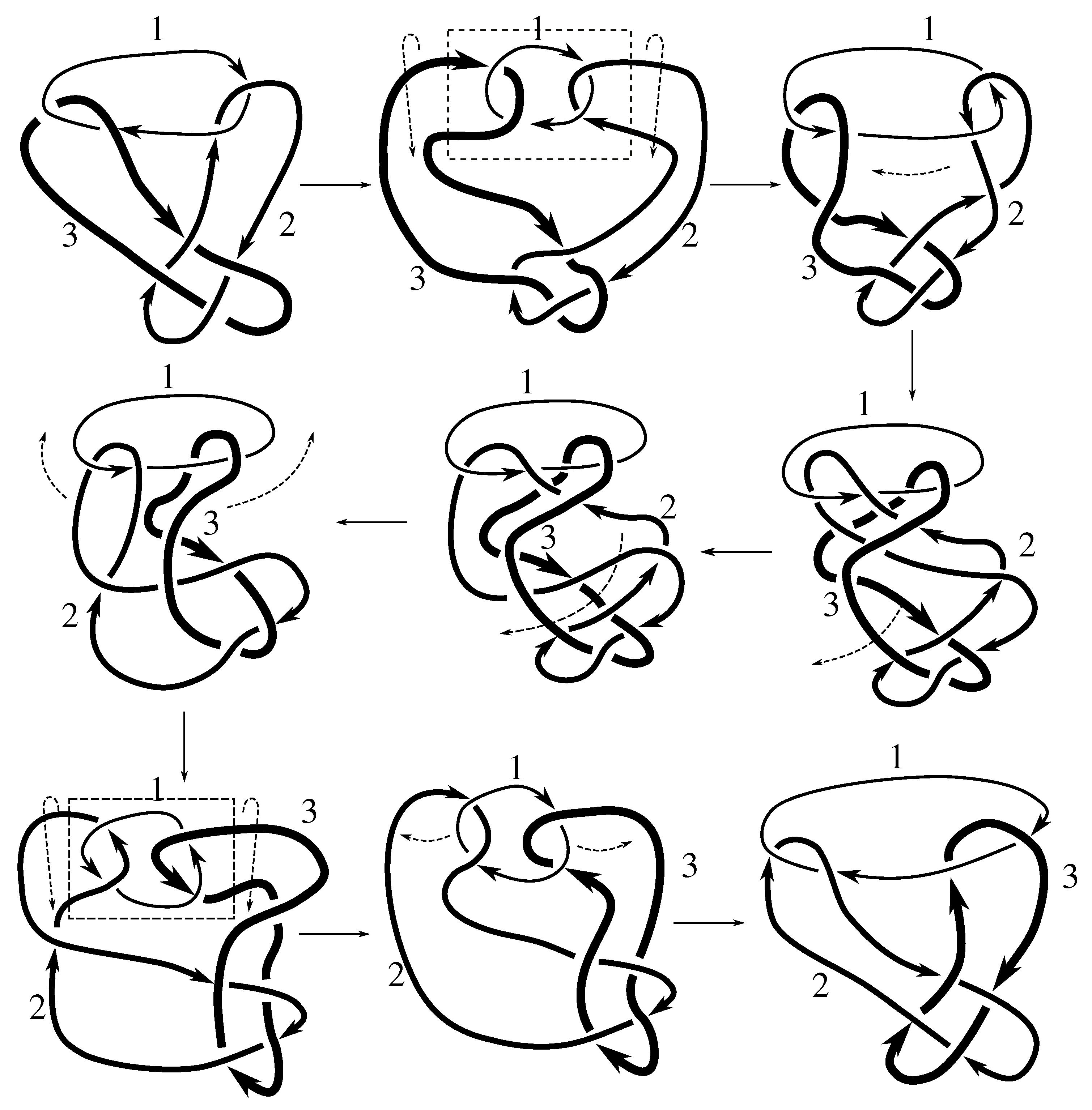

divides 12. Now

Figure D12 and

Figure D13 show that

Since the cycles

and

generate all of

, we know that all 6 of the pure exchanges are in

.

Figure D11 shows that

is purely invertible as well, completing the proof.

Finally, we note that we have encountered this symmetry group before, as .

Claim 8.8 The subgroup is the 4 element group isomorphic to generated by pure invertibility and .

The linking matrix for

is

which is in the standard form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that the stabilizer of

is the 8 element group

, which is generated by

, and pure invertibility. Hence,

divides 8.

Figure B3 and

Figure D14 show that the latter two of these generators, namely pure invertibility and

, are in

.

To finish the proof, we now show that the third stabilizer generator

does not lie in the symmetry group. Applying it to

, we get a link with HOMFLYPT polynomial

However, the base

has HOMFLYPT polynomial

This means that

and hence that

is generated by

and pure invertibility, as claimed.

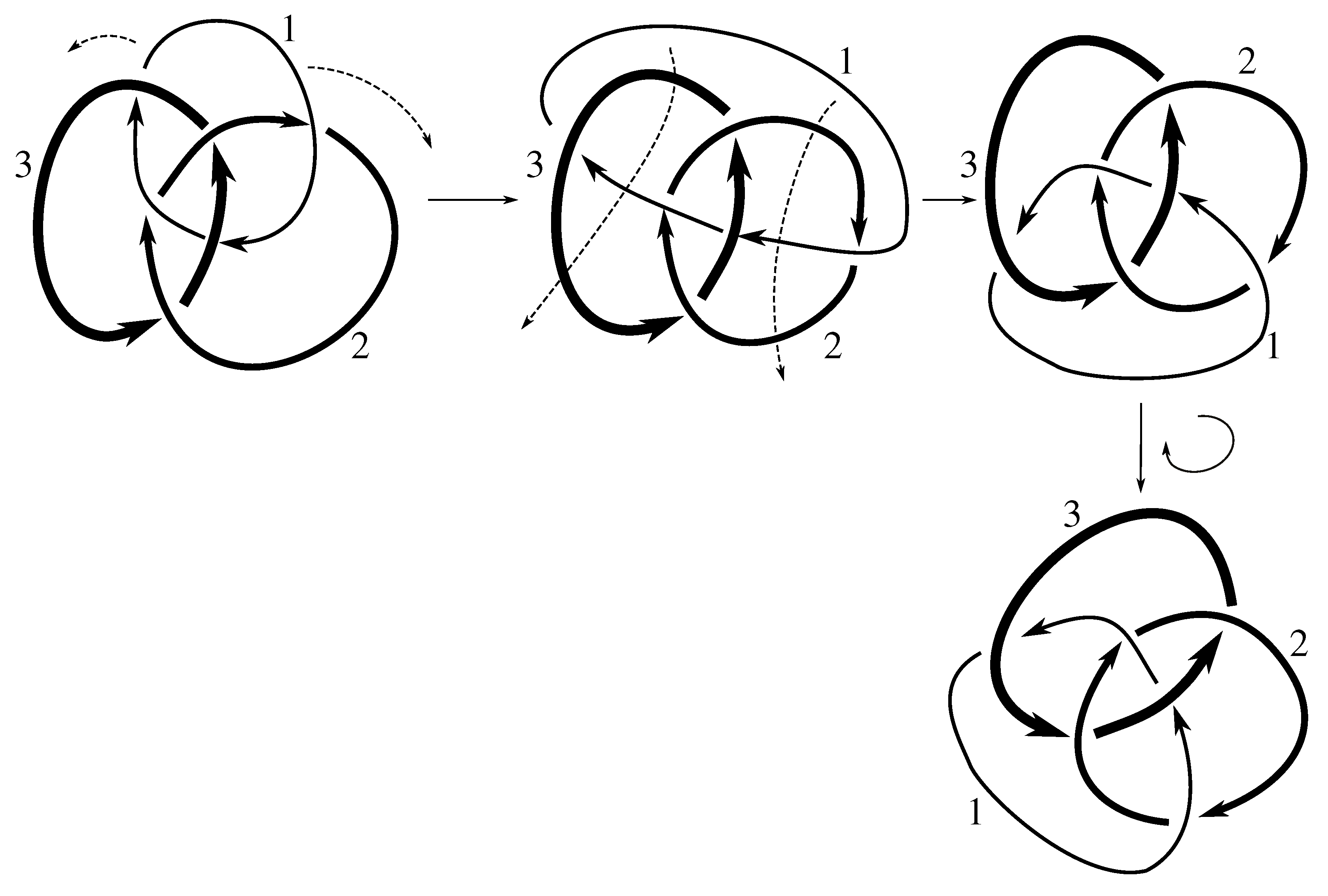

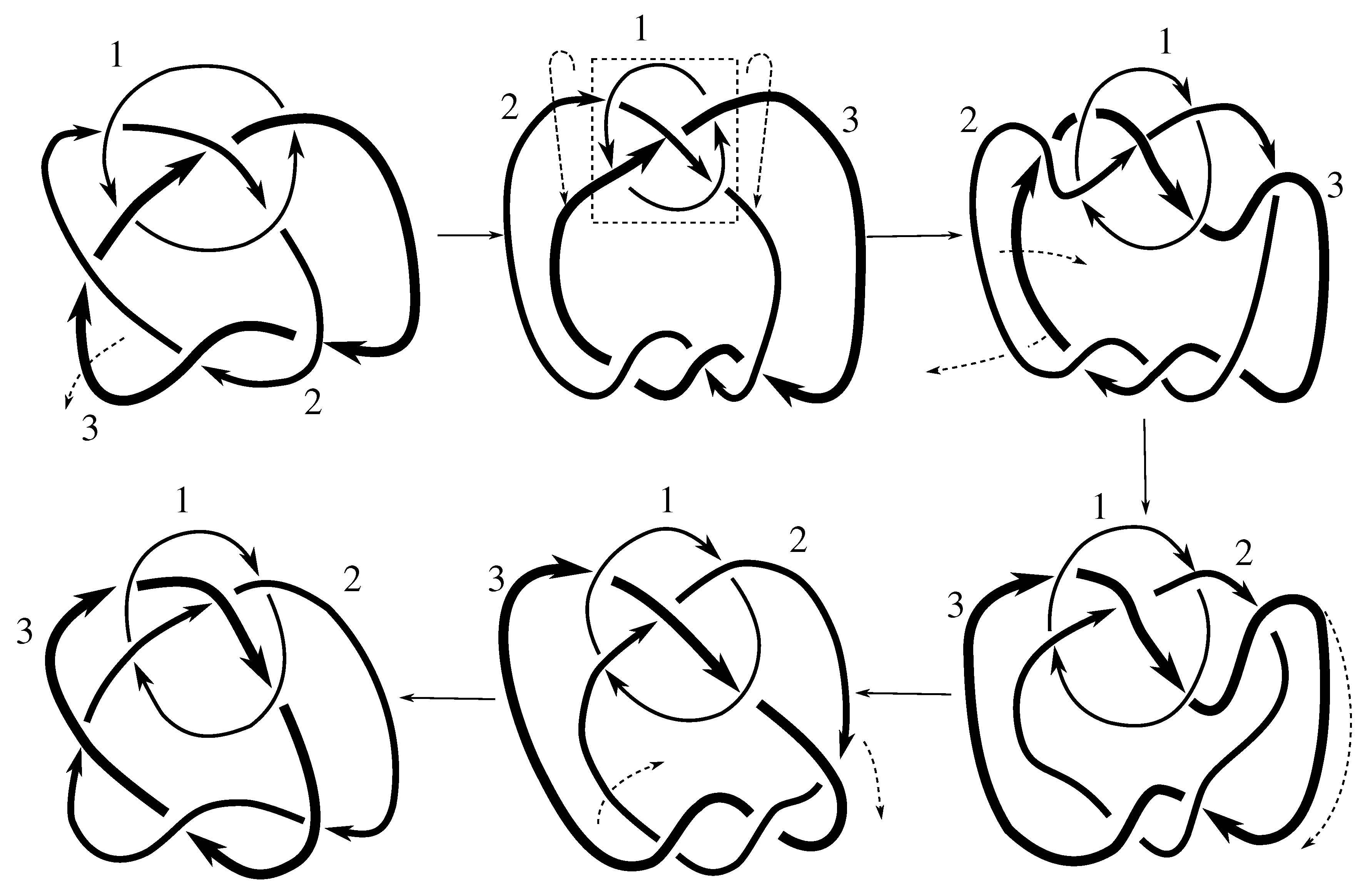

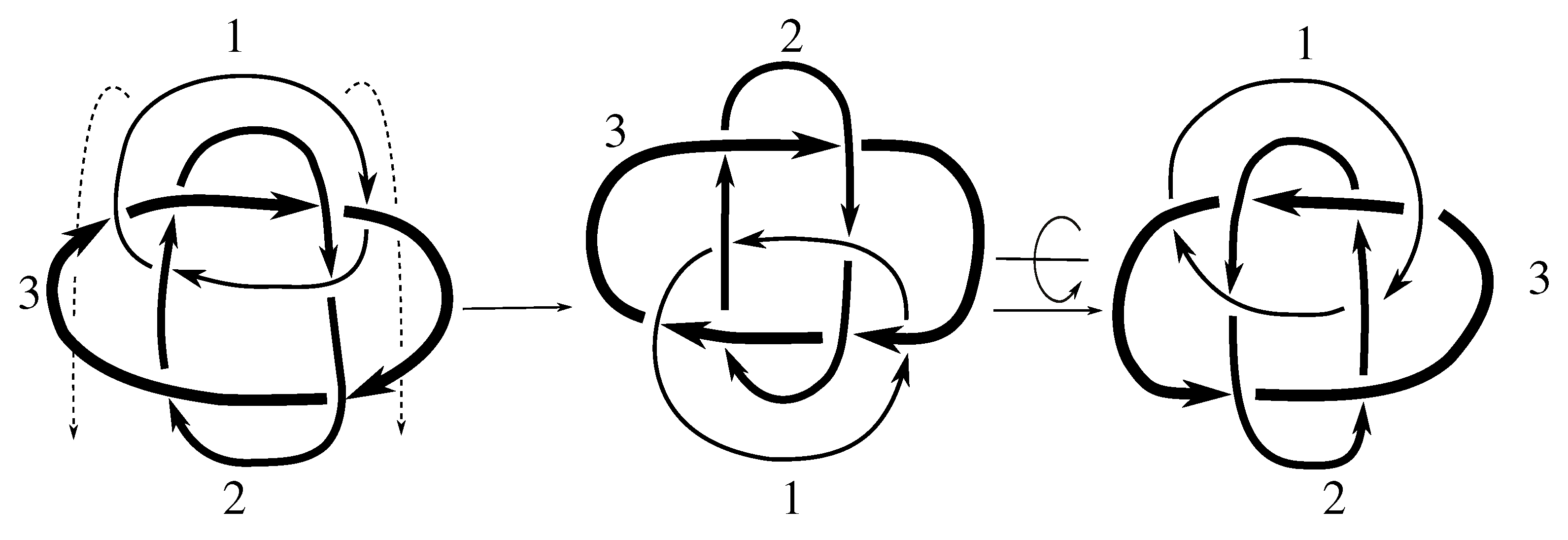

Claim 8.9 The symmetry group is the four element group isomorphic to generated by and .

Figure D15 and

Figure D16 imply that the four element group given above is a subgroup of

. Now the linking matrix for

is

which is in the standard form

. This means that the symmetry group must be a subgroup of the 16 element pre-image of

in

. Computing this pre-image, we observe next that if we apply any of the group elements

in this pre-image to our link, we get a link with Jones polynomial

while the base link has Jones polynomial

This rules out those 8 elements, leaving us with a subgroup of 8 possible elements remaining. Interestingly, even framing the various components of the knot and using the satellite lemma does not allow us to rule out any of the remaining symmetries. However, this link is hyperbolic, and Henry and Weeks[

3] use SnapPea to show that the symmetry group has four elements. Thus the four element subgroup of

generated by the isotopies in

Figure D15 and

Figure D16 must be the entire group.

Claim 8.10 The subgroup is the 8 element group isomorphic to which is generated by Figure B3,

Figure D17, and

Figure D18, respectively, imply that the three generators above lie in the symmetry group

. Now the linking matrix for

is

which corresponds to the triple

and has the same orbit type as

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that the stabilizer of the linking matrix is precisely the group above, and hence equals

, which completes the proof.

Claim 8.11 The subgroup is the 4 element group isomorphic to generated by the pure exchange and pure invertibility.

Figure B4 and

Figure D19 show that

, which implies that the subgroup above is contained in

. Now the linking matrix for

is

which is in the standard form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that

divides 4. Since we already have 4 elements in the group, this completes the proof.

Finally, we note that we have encountered this symmetry group before, as .

Claim 8.12 The subgroup is the four element subgroup isomorphic to generated by pure invertibility and .

Figure D20 and

Figure D21 show that

, which implies that

contains the claimed group. Now the linking matrix for

is

which is in the standard form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that

divides 4. This completes the proof, since we already have 4 elements in the subgroup.

Finally, we note that we have encountered this symmetry group before, as .

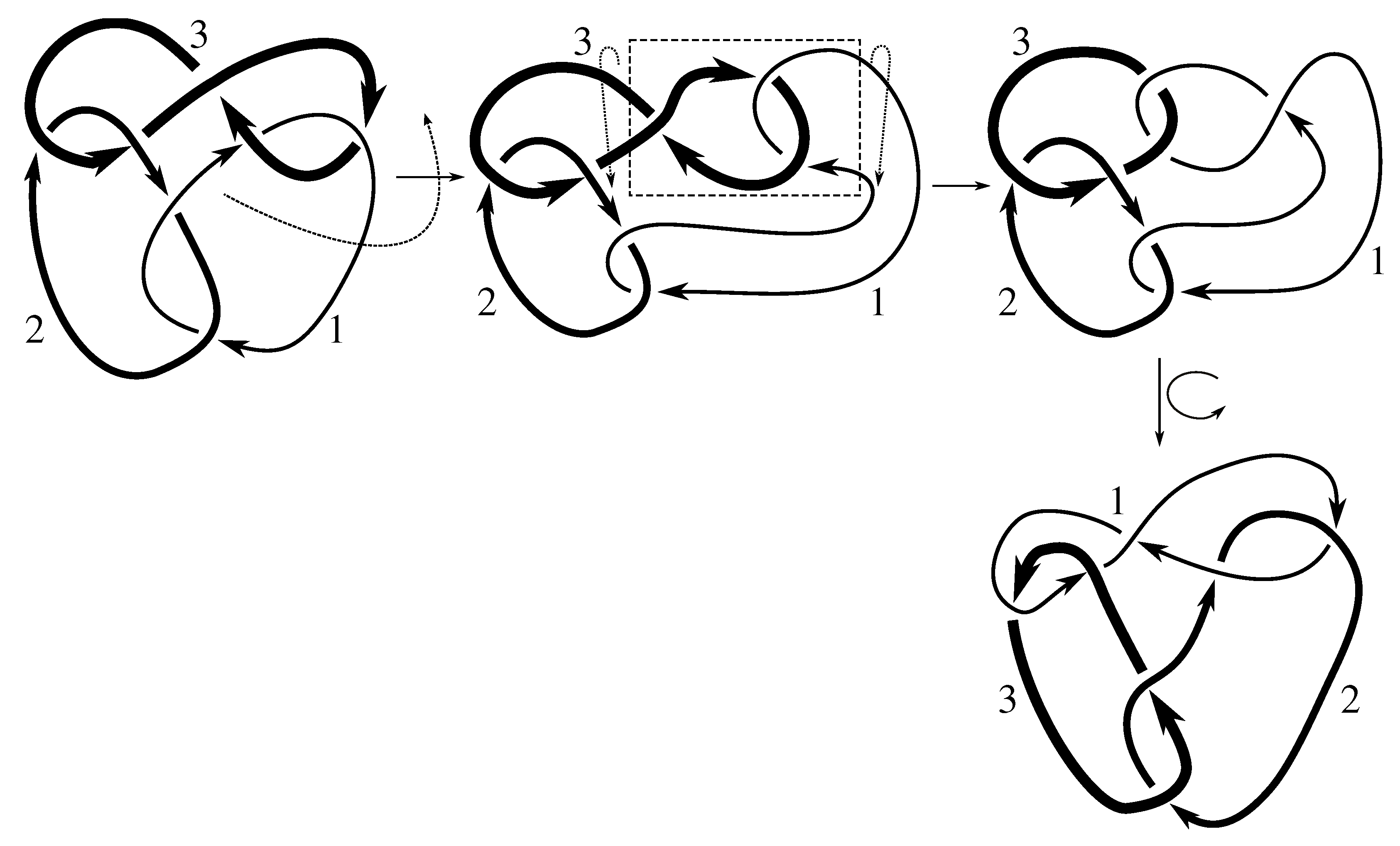

Claim 8.13 The subgroup is the 8 element group isomorphic to generated by pure invertibility, the pure exchange and .

Figure B4,

Figure D22, and

Figure D23 show that

, which implies that the 8 element subgroup generated by these elements is a subgroup of

. Now the linking matrix for this link is

which is in the standard form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that

divides 16. Working out these 16 elements as in the case of

, we see that if we apply any of the elements

to

, we get a link with Jones polynomial

while the Jones polynomial of the base

link is

This leaves only the subgroup claimed. We note that while

and

have the same stabilizer, the symmetry group

is a proper subgroup of

.

Claim 8.14 The subgroup is the 4 element group isomorphic to generated by pure invertibility and the pure exchange .

Figure B3 and

Figure D24 show that

and

are in

. Now the linking matrix for

is

which has the standard form

. Consulting

Table 12, we see that this matrix has an 8 element stabilizer in

given by the inverse image of

under the map

f. Now we observe that if we apply any of the four elements

in this stabilizer to

, we get a link with Jones polynomial

while the base

link has Jones polynomial

This rules out all but the four element subgroup above, completing the proof.

9. Isotopies for Four-Component Links

There are three prime four-component links with 8 crossings. They are quite similar in appearance, with only some crossing changes distinguishing them. Their symmetry computations are made somewhat more difficult by the fact that we are working in the 768 element group . All three of these links are composed of four unknots linked together so that component 1 is linked to 2 and 3, and 2 and 3 are linked to 4.

Here are the symmetry groups for these links, listed in terms of generators for each group. Again, we denote the purely invertible symmetry, i.e., element , by PI; all three links admit this symmetry.

Our approach mimics the one used for three-component links. After calculating the linking matrix, we utilize

Table 7 to determine the stabilizer of this matrix within

; we know that the symmetry group

must be a subgroup of this stabilizer. Next, we show some elements are in the symmetry group by exhibiting isotopies and rule others out using polynomial invariants until we can discern the symmetry group.

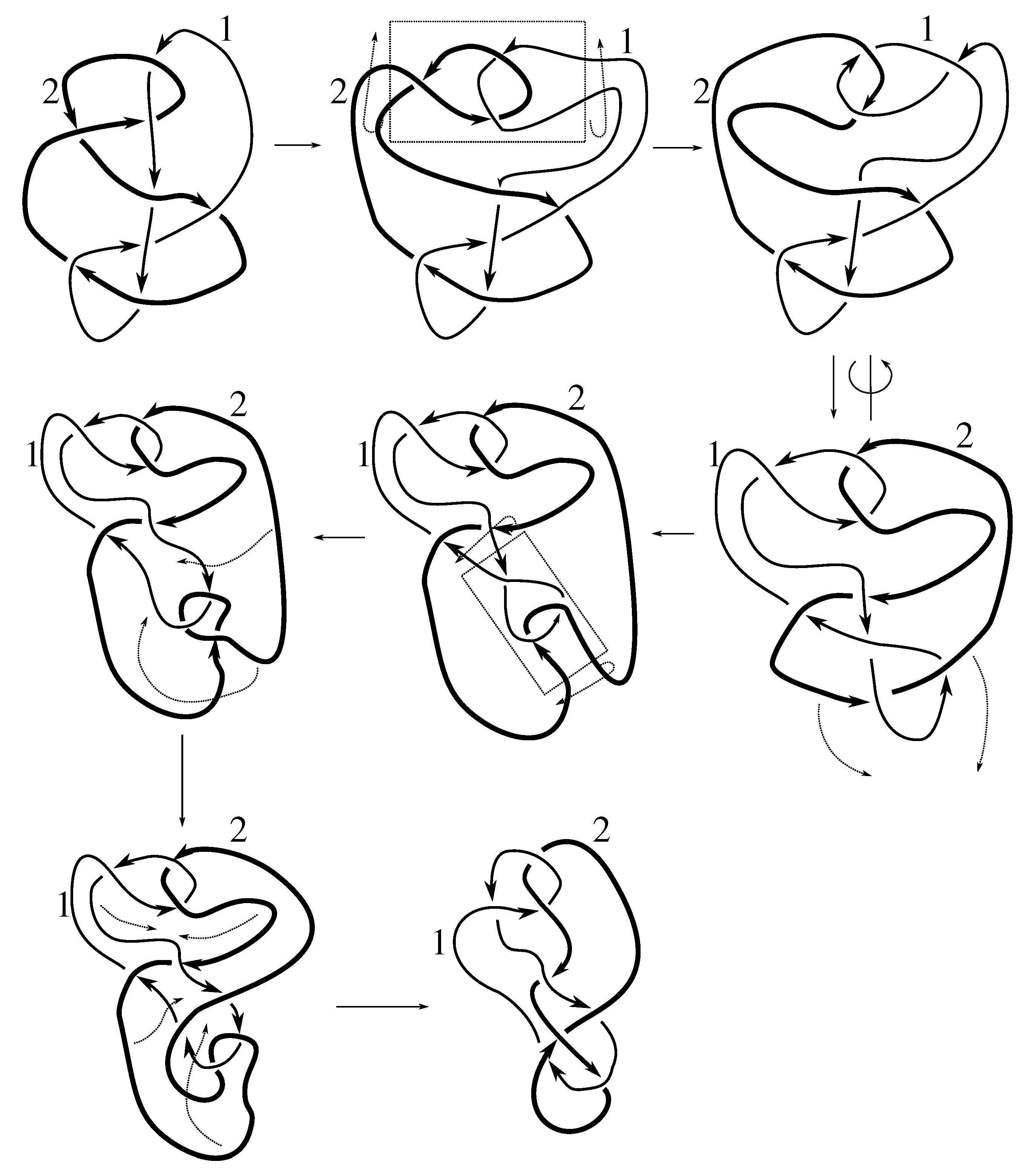

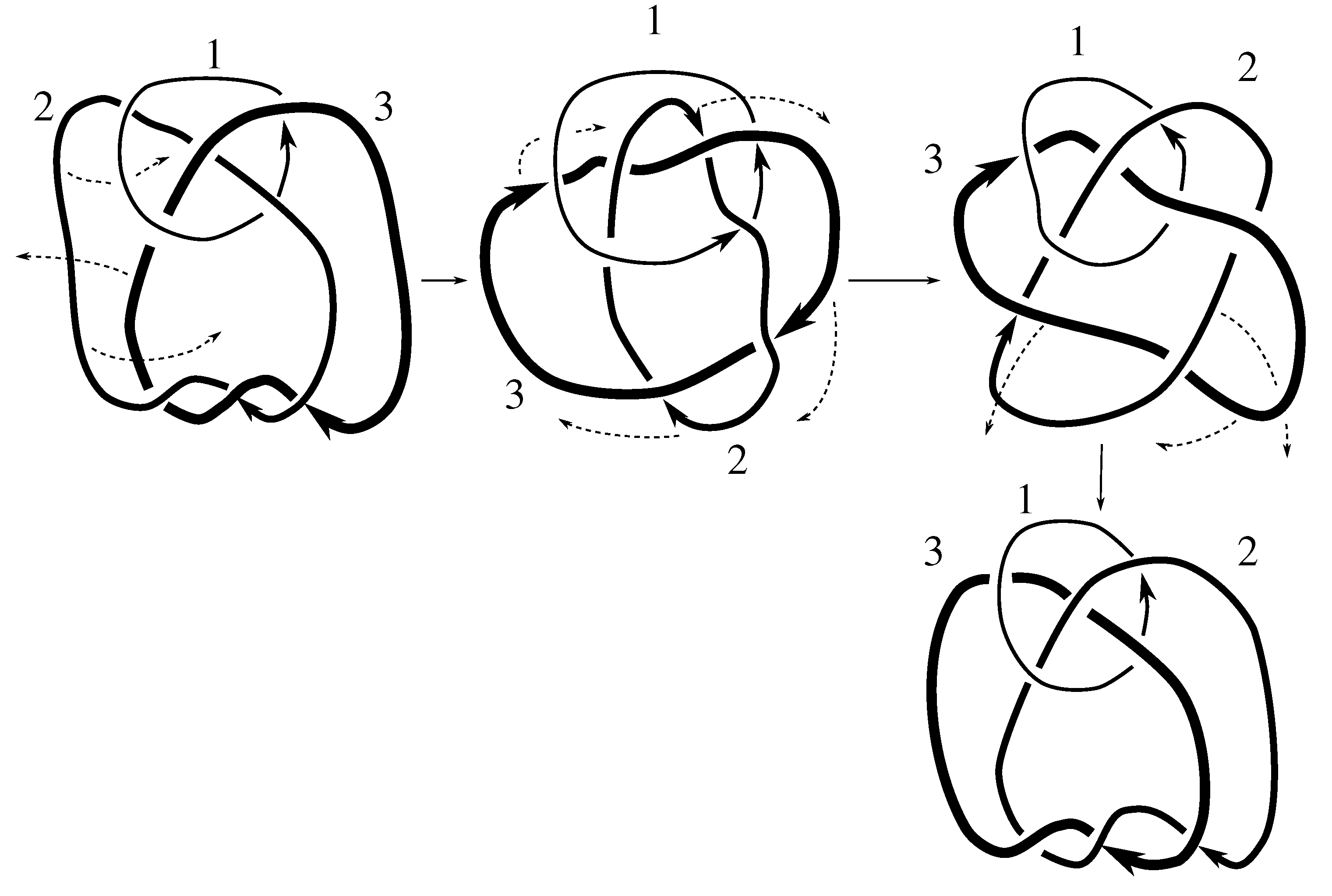

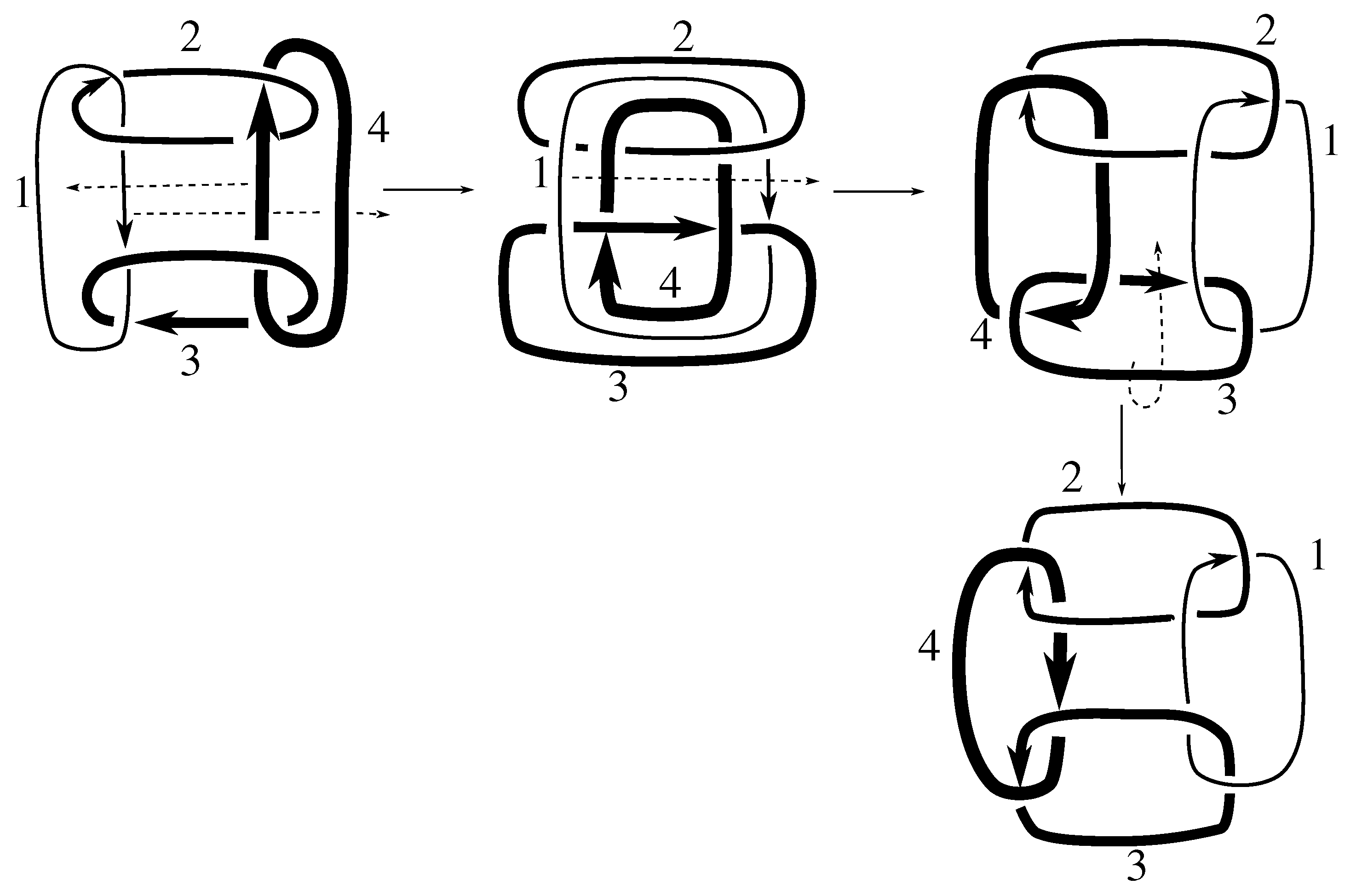

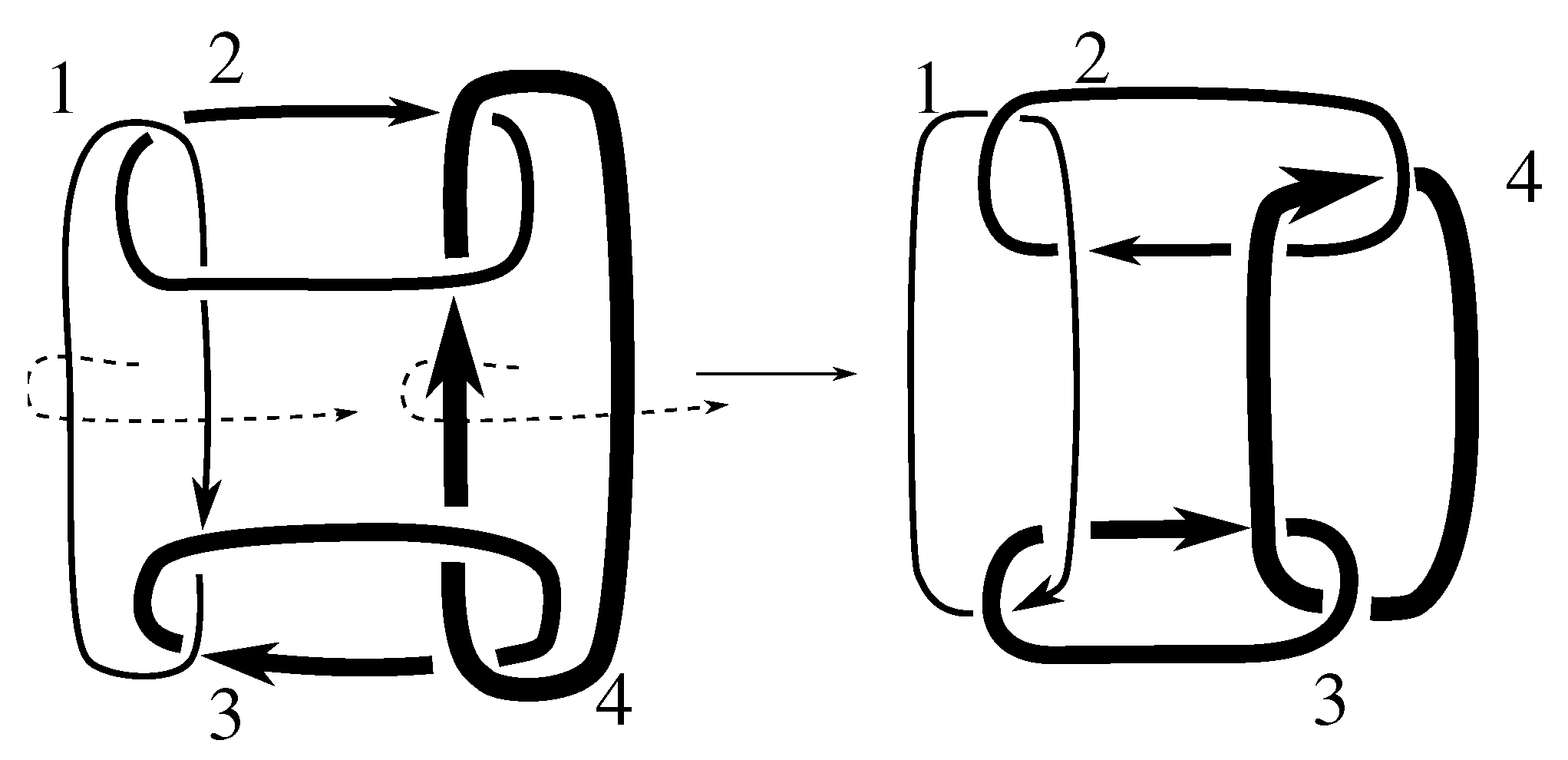

Claim 9.1 The symmetry subgroup for is the 16 element group isomorphic to given by the -orientation-preserving elements of the inverse image .

The linking matrix for

is

which corresponds to the standard form

. By Lemma 5.9,

must be a subgroup of the 32 element stabilizer

of the linking matrix.

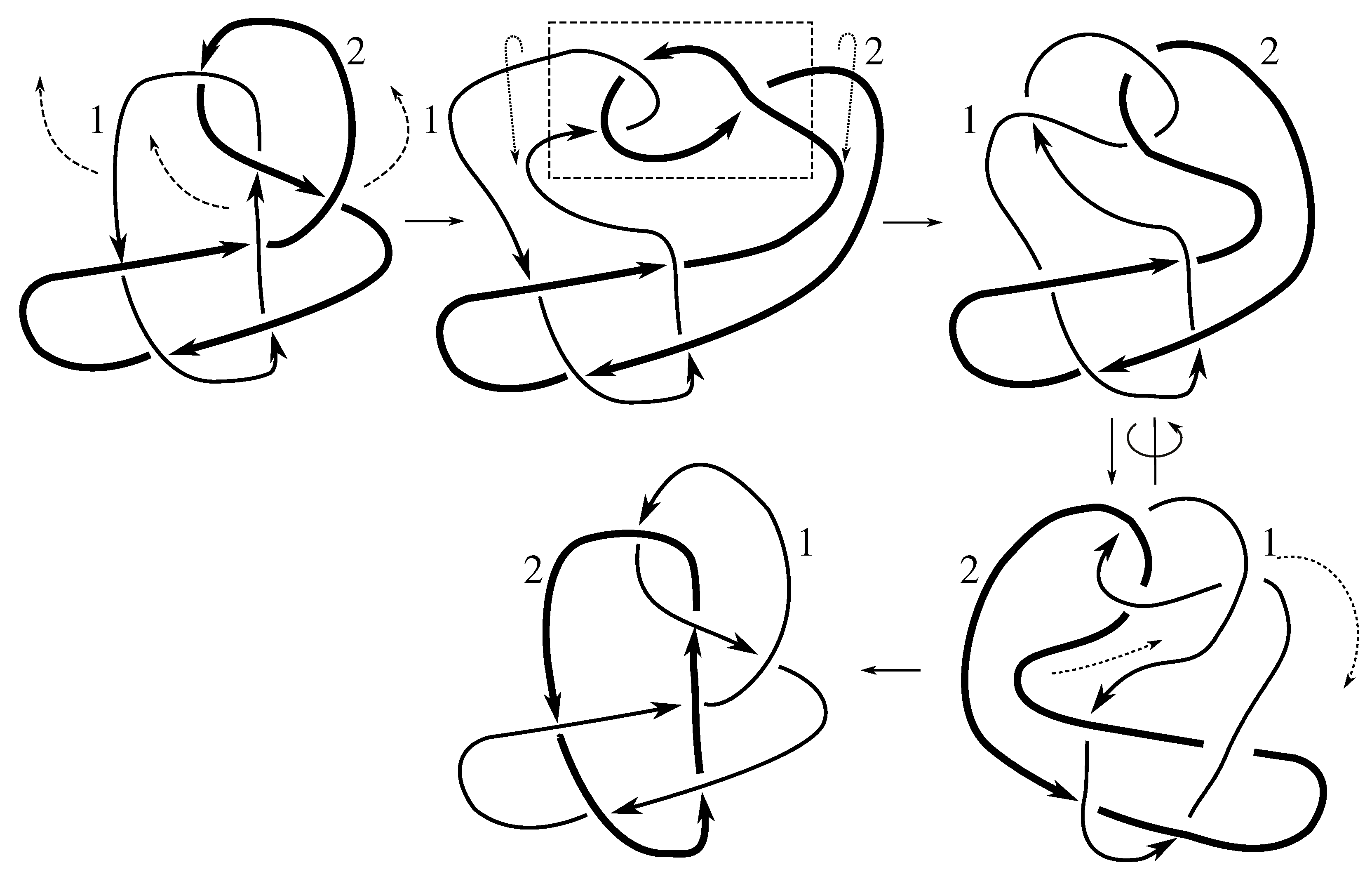

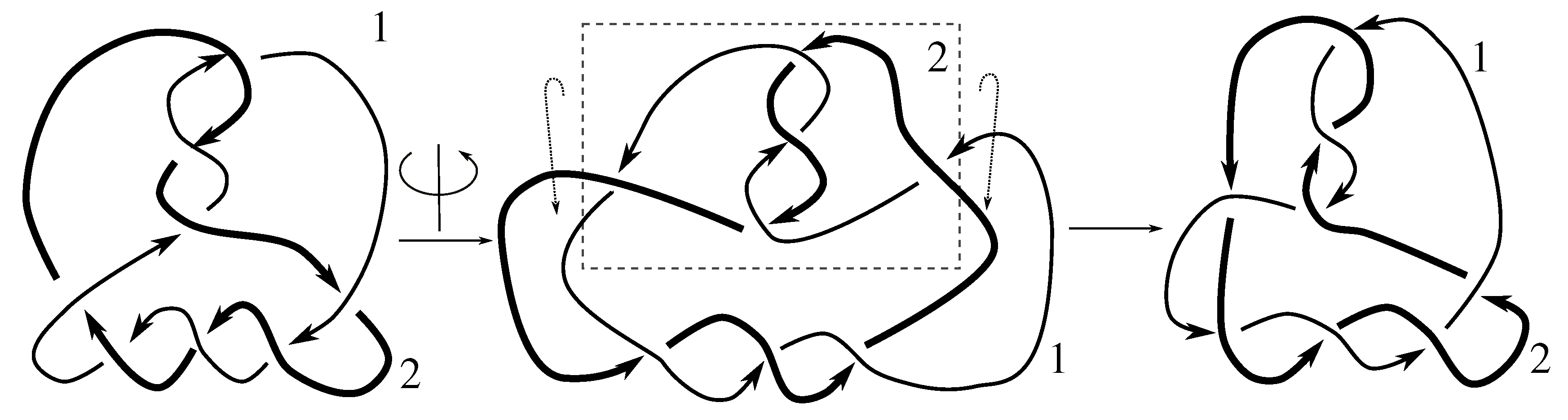

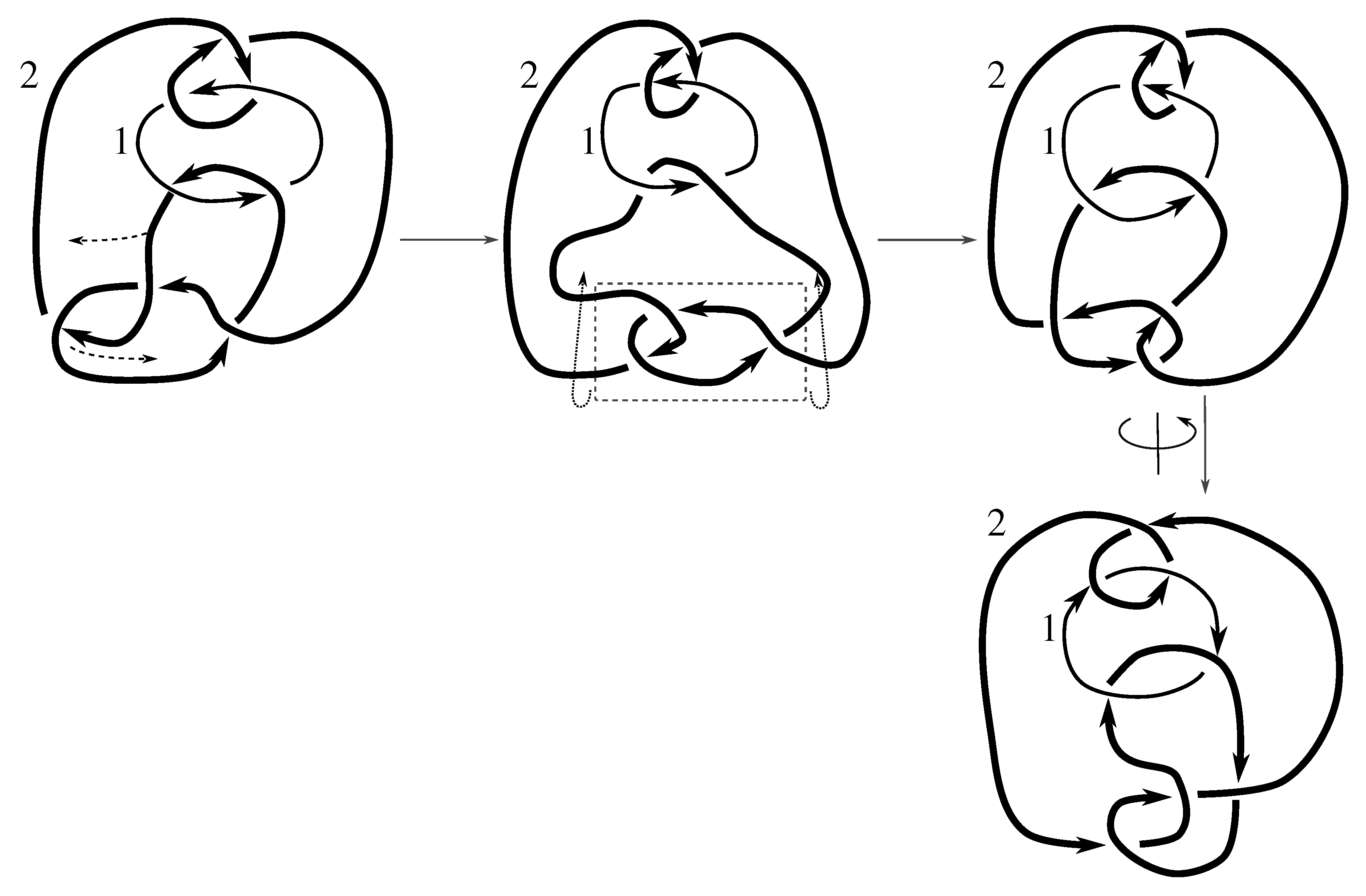

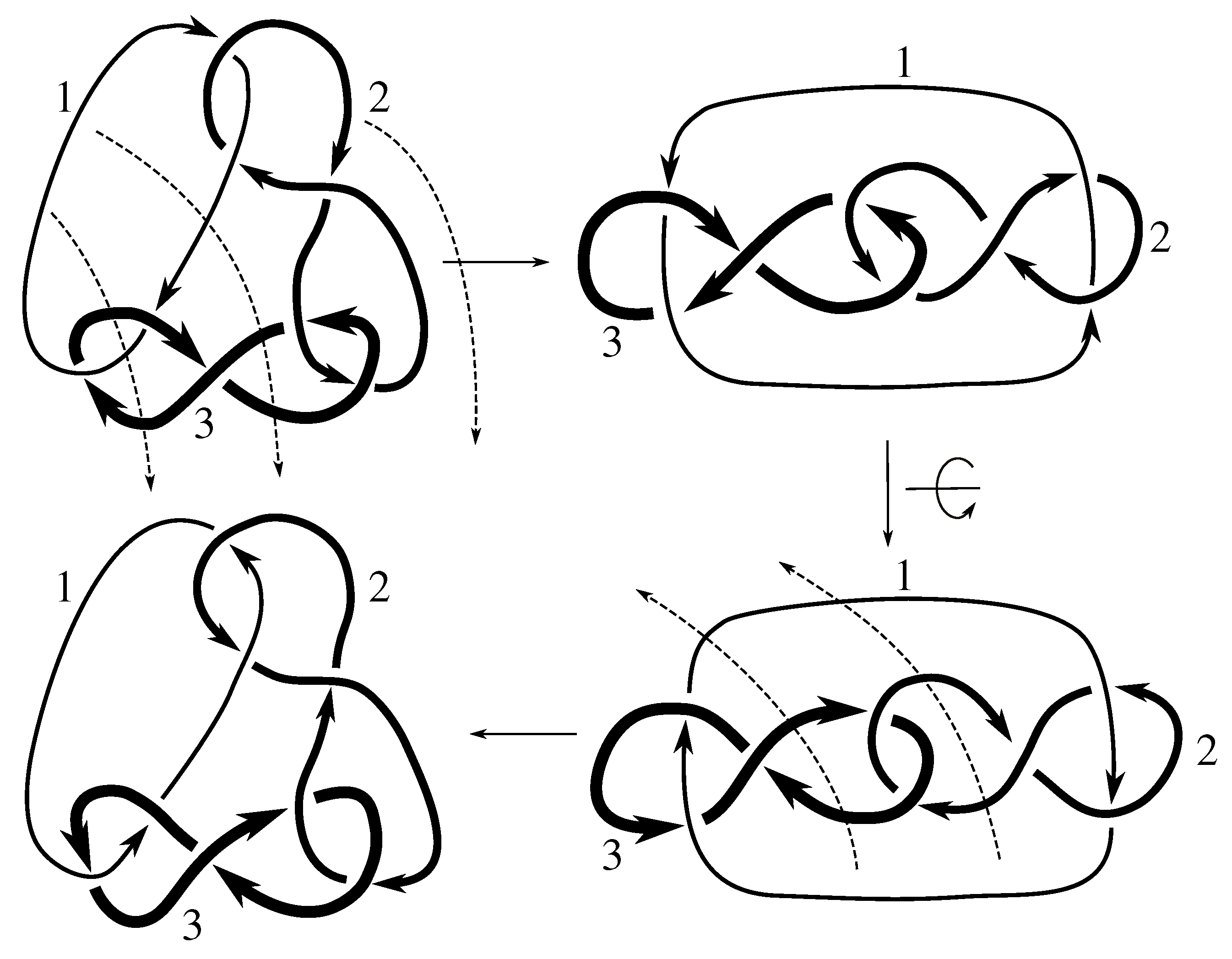

Figure E1,

Figure E2, and

Figure B2 show that pure invertibility and

and

are all in

. Together, these generate the 16 element group of the claim.

We must show that the 16

-orientation-reversing elements of the stabilizer (

i.e., elements of the form

) are not in the symmetry group. If we apply any of these 16 elements to the base link, we obtain a link with Jones polynomial

But the Jones polynomial of the base

is

This rules out all 16 of these remaining elements, which proves the claim.

Claim 9.2 The symmetry subgroup for is the 16 element group isomorphic to given by the -orientation-preserving elements of .

The linking matrix for

is

which corresponds to the standard form

(remember that the ordering of elements given by Equation (

4) is not obvious). By Lemma 5.9 the stabilizer of this linking matrix in

is a 32 element subgroup isomorphic to

.

Figure E3 and

Figure E4 show that

and

are in

. Together, these generate the 16 element group of the claim.

We must show that the 16

-orientation-reversing elements of the stabilizer (

i.e., elements of the form

) are not in the symmetry group. If we apply any of these 16 elements to the base link, we obtain a link with Jones polynomial

while the base link has Jones polynomial

This rules out these 16 remaining elements, so the claim is proven.

Claim 9.3 The symmetry subgroup for is the 32 element group isomorphic to given by .

The linking matrix for

is

which corresponds to the standard form

. By Lemma 5.9 the stabilizer of this linking matrix in

is a 32 element subgroup isomorphic to

. This group is generated by the isotopies in

Figure E5,

Figure E6,

Figure E7, and

Figure E8, which show that pure invertibility, along with elements

10. Comparison of Intrinsic Symmetry Groups with Ordinary Symmetry Groups for Links

We now compare our results on intrinsic symmetry groups to the existing literature on symmetry groups for links. Henry and Weeks [

3,

22] report

groups for hyperbolic links up to 9 crossings, while Boileau and Zimmerman [

4] computed

groups for non-elliptic Montesinos links with up to 11 crossings, and Bonahon and Siebenmann computed

for the Borromean rings link (

) as an example of their methods in [

2] (Theorem 16.18).

Comparing all this data with ours, we see that

Lemma 10.1 Among all links of 8 and fewer crossings with known groups, the Whitten symmetry group is not isomorphic to only for the links in Table 13. Our results provide some data on symmetry groups of torus links as well.

Lemma 10.2 For the , and torus links (, , and ), we have . For the Hopf link, the torus link, we know that .

Goldsmith computed [

23] the “motion groups”

for torus knots and links in

. Combining her Corollary 1.13 and Theorem 3.7, we see that for the

torus link

, the subgroup

of orientation preserving symmetries is homeomorphic to

if

is odd, and an index two quotient group of

if

is even. The motion group itself is either

or an 8-element quaternion group. But in either case

.

Now the motion group by itself does not provide any information about the orientation reversing elements in Sym. However, any such element in would map to an element in which reversed orientation on . Since we have already shown that there are no such elements in for , , , we see that for these links . For the Hopf link such an orientation reversing element does exist in . So, is a extension of and thus is isomorphic to

By Proposition 4.9, the group

is the image of

under a homomorphism, and hence a quotient group of

. Further, if

has only orientation-preserving elements (on

) then

does as well. Thus we know something about the

groups of all our links;

Table 14 summarizes the new information provided by our approach.