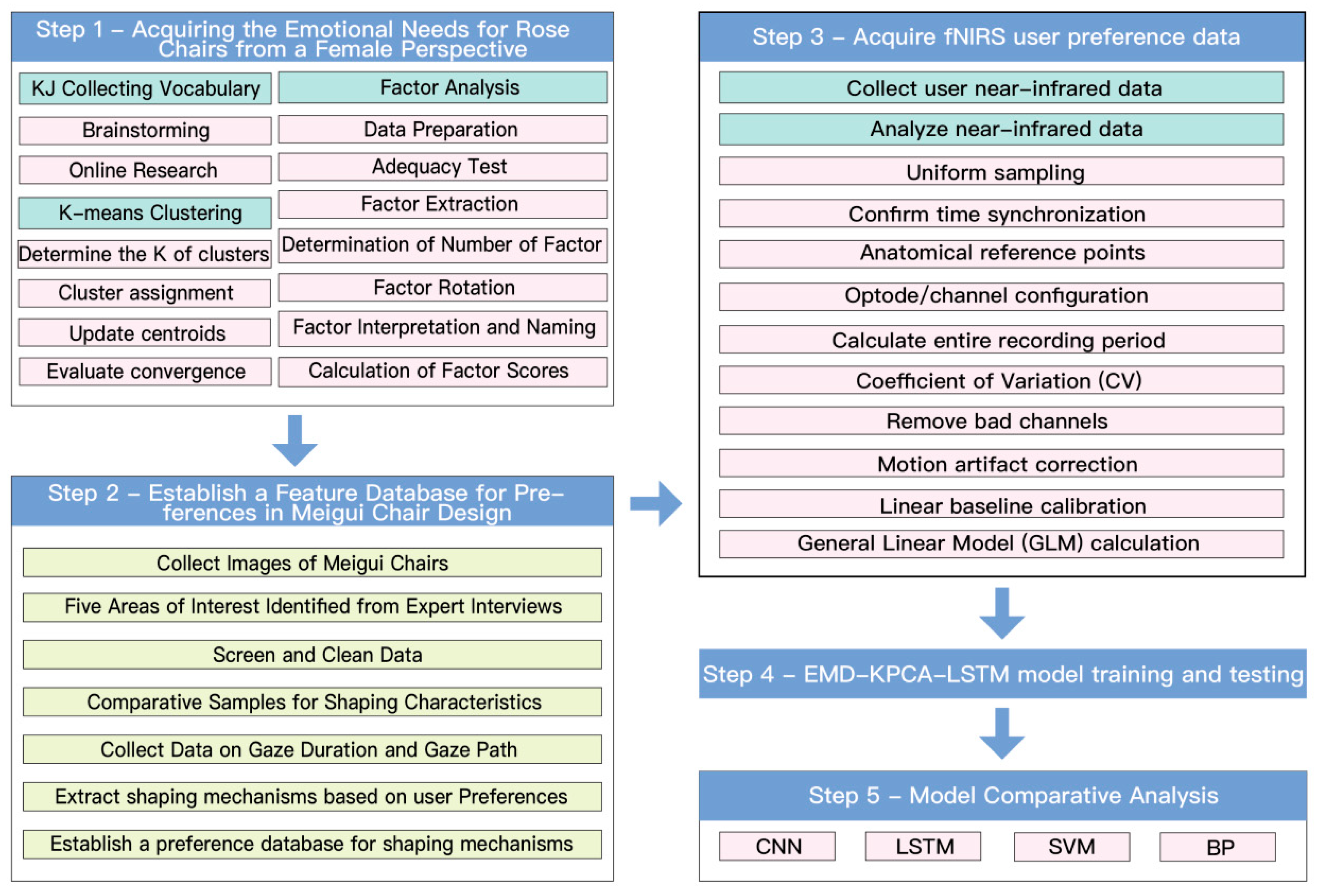

This study aims to utilize the EMD-KPCA-LSTM framework to train a dataset of visual sequences of Mei Gui (Rose) chair morphologies, with the goal of enhancing the accuracy of user preference prediction. Furthermore, this research seeks to construct a mapping model between the morphological features of Mei Gui chairs and user emotions, thereby designing Mei Gui chairs that align with user preferences. The specific research process is outlined as follows:

Step 2: Collect high-resolution images of Mei Gui chairs. Through expert interviews, partition the morphological mechanisms into regions to establish a comparative sample map of element preferences. Collect eye-tracking data from experts to create a design element table for user-preferred Mei Gui chair forms. Simultaneously, collect preference evaluation scores from female users for each Mei Gui chair design, which are subsequently transformed using triangular fuzzy numbers.

Step 3: Acquire and process functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) data. The fNIRS device used was the NirSim-100 wearable functional near-infrared brain imaging system from Wuhan Yirui Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China).

Step 4: Input the obtained eye-tracking data and user evaluations into the established EMD-KPCA-LSTM model for training.

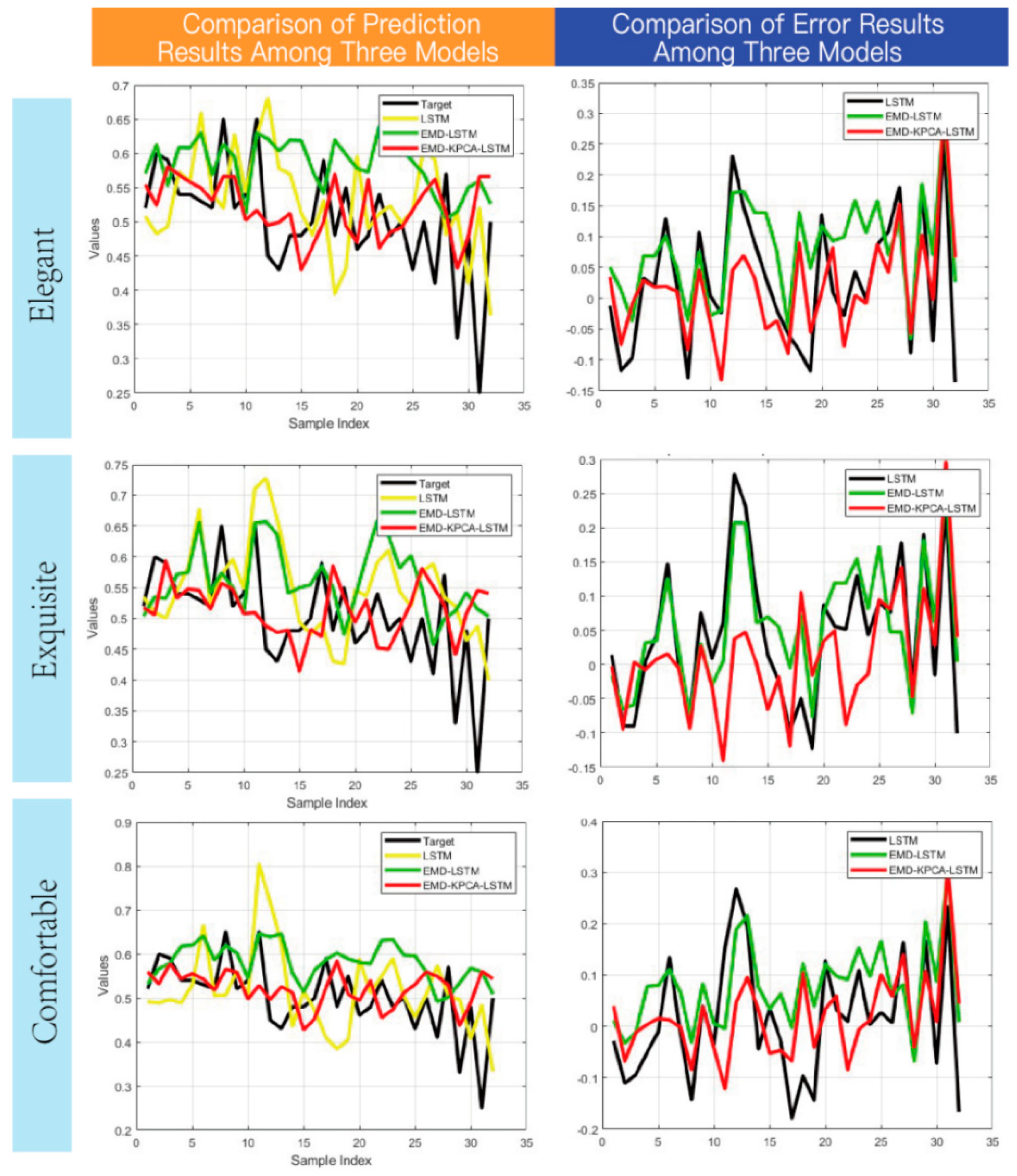

Step 5: Input the data into traditional frameworks such as CNN, SVM, and BP, and compare the results with simpler benchmark models (e.g., KPCA + SVM, Random Forest) to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed framework.

2.1. User Data Collection Process

This study collected visual sequence data and fNIRS data from 35 female participants. The experimental design was structured as follows:

A total of 94 images of Mei Gui chairs, representing the key characteristics of the dataset, were selected. The resolution and viewing angle of all stimulus samples were standardized. Based on the structural design components of the Mei Gui chair, five categories of morphological features were identified, corresponding to pre-defined Area of Interest (AOI).

Clarification on Sample Selection Criteria: The 94 images were selected from an initial pool of over 200 historical and contemporary Mei Gui chair images. The selection criteria included the following: (1) Era Representativeness: covering three main periods: Ming-style (minimalist), Qing-style (ornate), and modern innovative designs; (2) Craftsmanship Style: balanced selection of representative works from five major craftsmanship and decoration styles: Plain Carving, Comb-Back Chair, Narrow Backrest, Hollow Backrest, and Full Carving; (3) Morphological Integrity: ensuring images were high-definition (resolution no less than 1920 × 1080 pixels), frontal view, and with unobstructed main subjects; (4) Material Visibility: images needed to clearly show wood grain (e.g., rosewood, padauk, wenge wood) and any possible metal fittings. The final selected samples were balanced across style categories to ensure diversity and representativeness of the dataset.

- (2)

Participants

We recruited 35 participants, comprising 14 industry experts (including 5 designers from traditional furniture enterprises, 5 traditional furniture craftspeople, and 4 university professors in furniture design), 8 traditional furniture enthusiasts, and 13 amateur users planning to purchase traditional furniture. During the collection of visual sequence data, participants were instructed to evaluate the images using a 7-point Likert scale. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1.

Supplement on Specific Scale Questions: Participants rated each Mei Gui chair image on the following four dimensions (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree):

Esthetic Appeal: “I find this chair visually appealing.”

Perceived Comfort: “This chair looks comfortable to sit in.”

Craftsmanship Recognition: “I think the craftsmanship of this chair is of high quality.”

Purchase Intention: “If circumstances allowed, I would consider purchasing this chair.”

For the purpose of constructing machine learning models, each “participant × image” combination was treated as an independent observation. The raw data comprised a total of 35 participants × 94 images = 3290 trials. For each trial, corresponding eye-tracking and fNIRS features were extracted to form a feature vector. Therefore, each observation corresponds to the response features and multi-dimensional ratings from a specific participant for a specific image, resulting in a final dataset size of N = 3290 rows. During the subsequent model training and evaluation employing 5-fold cross-validation, a subject-based data splitting strategy was strictly implemented. This ensured that all data from the same participant (i.e., their corresponding 94 rows of observations) were always assigned to the same subset (either training or test set) in each validation fold, thereby preventing data leakage and overfitting, and guaranteeing the reliability of the model generalization assessment.

To address potential biases arising from differing levels of expertise, data from expert users (n = 14) and non-expert users (n = 21) were subjected to comprehensive analysis, subgroup analysis, and robustness checks.

- (3)

Equipment

The experiment utilized an Ergolab eye-tracking system (Tobii X60/X120) with its accompanying Tobii Pro Lab software (version 24.21), (The eye-tracking data were collected and processed using Tobii Pro Lab software (developed by Tobii Pro AB, Danderyd, Sweden).) a wearable functional near-infrared brain imaging device (NirSim-100), E-Prime 3.0, and MATLAB 2023a.

- (4)

Experimental Procedure

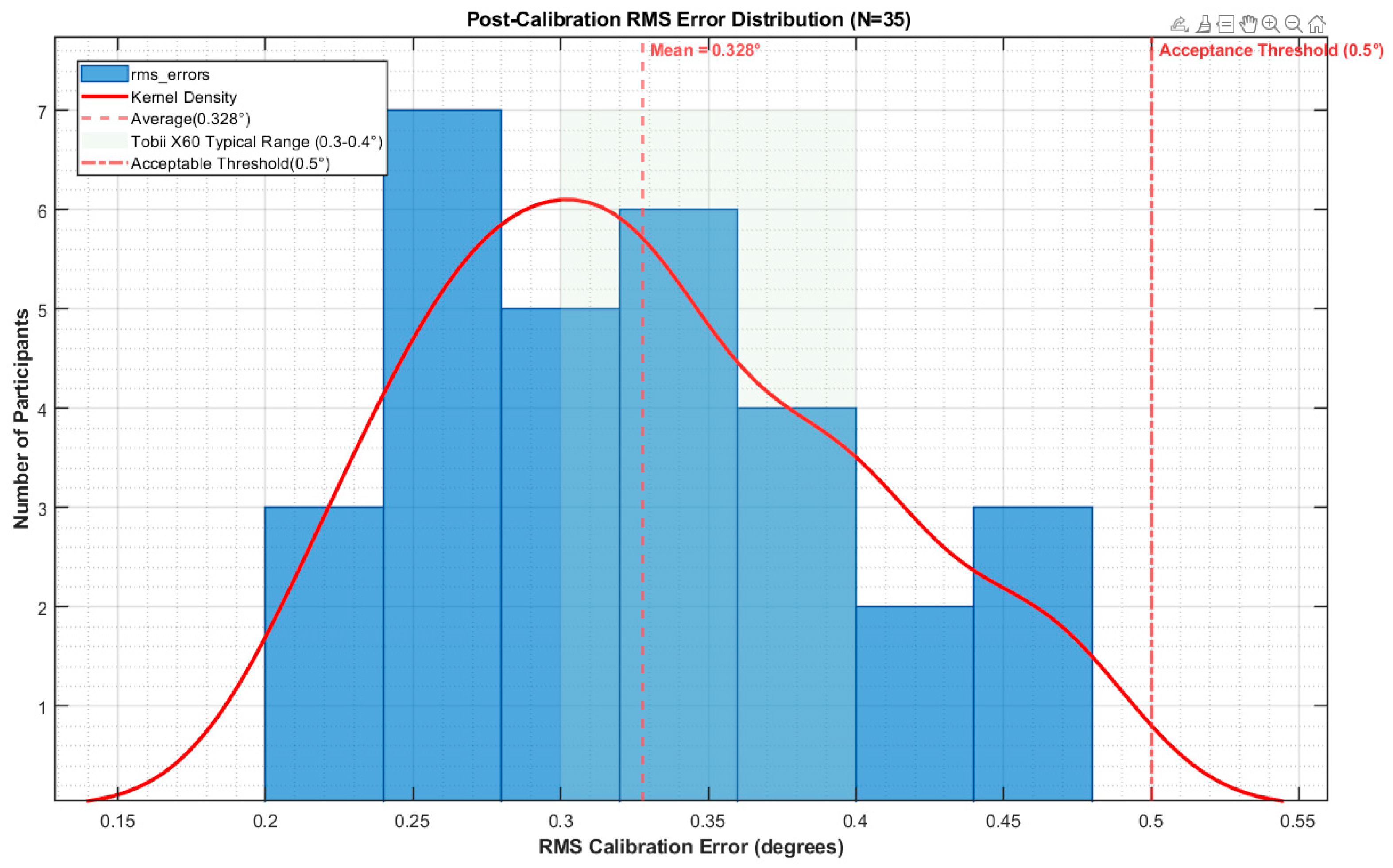

Following an introduction to the experimental workflow, participants underwent a standardized calibration and adaptation phase to ensure data validity. Calibration was performed using a nine-point grid procedure, wherein participants were instructed to sequentially fixate on red dots (diameter: 0.5° visual angle, duration: 1500 ms) displayed at predetermined positions on the screen, maintaining a viewing distance of 60 cm.

Calibration accuracy was validated through a two-step process: (1) The gaze deviation for each calibration point was required to be less than a preset acceptance threshold of 0.5° (this threshold is stricter than the device’s typical accuracy of 0.3–0.4° at 60 cm distance). (2) Operator monitoring and verification: The operator inspected the gaze trajectory in real time to ensure its consistency with the sequence of calibration points.

During the experiment, the wearable fNIRS headpiece was properly positioned, and channel alignment was performed prior to data acquisition using E-Prime 3.0.

Following the experiment, heat maps were generated using Tobii Pro Lab, and gaze sequence data were exported. These data were subsequently analyzed with the NirSim-100 proprietary software (V2.1).

2.2. Multimodal Technology

2.2.1. Eye-Tracking Technology

Eye-tracking technology is a non-invasive experimental tool that detects human eye movements to obtain data on attention distribution, eye movement trajectories, and gaze speed. This technology is based on the “brain-eye consistency hypothesis,” which posits that the location of gaze is typically related to the object of attention and thought. Currently, popular eye-tracking techniques primarily rely on video-oculographic (VOG) analysis, a non-invasive method. Its fundamental principle involves directing a beam of light (near-infrared) and a camera toward the participant’s eyes, using the light and backend analysis to infer the direction of gaze. In this study, we utilized the ErgoLAB device to capture feature data related to the design of Mei Gui chairs.

2.2.2. Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

The analysis was performed using the NirSim-100 software, adhering to the following procedural steps:

Data Import and Preprocessing.

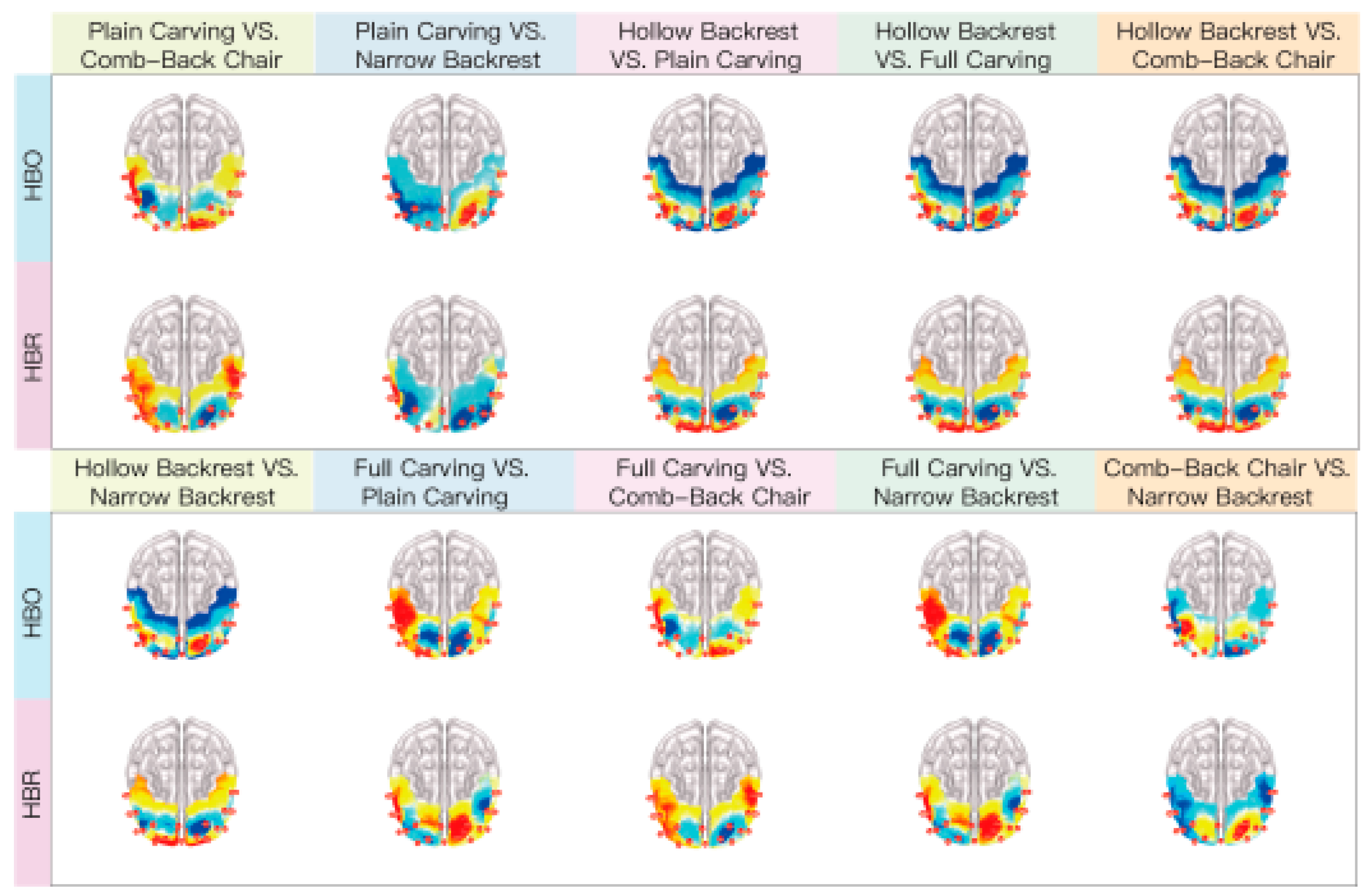

Data Import: The analyzed eye-tracking data segments were imported and categorized into five distinct groups (Plain Carving, Comb-Back Chair, Narrow Backrest, Hollow Backrest, and Full Carving), with 10 images per group, to investigate the influence of specific Mei Gui chair design types on user preferences [

11].

Sampling Rate Configuration: The sampling rate was set to 20 Hz, consistent with the data acquisition parameters [

12].

MARK Time Validation: The accuracy of the pre-configured MARK timestamps was rigorously validated. These markers correspond to the onset of the 1200 ms chair image presentation period within each trial.

Spatial Registration: Anatomical reference points and the optode channel layout were input. Brain region mapping was subsequently performed by selecting the Brodmann area map and the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas.

Quality Control: Channel-wise CV Calculation: The coefficient of variation (CV) was computed for the entire dataset, with time zero as the starting point. The bad channel threshold was established at 15%. This specific threshold was determined via Bonferroni correction: given the 20 Hz sampling rate and a 1.2 s trial duration, each channel generated 24 time points per trial. Considering the number of channels (N = 22) in the equipment used, the conventional 20% threshold was adjusted to a more stringent level (α = 0.05/N channels) to control the family-wise error rate, thereby deriving the practical CV threshold of 15%. (This value could be directly calculated and selected within the experimental apparatus software).

Block-wise CV Calculation: The CV was calculated for each individual trial, using the MARK onset as time zero. The start time was set to −200 frames (to preserve the baseline period), and the end time was set to 1200 frames (representing the stimulus presentation duration minus the baseline period). The bad channel threshold for this block level assessment was set at 20%.

Data Preprocessing: Motion Artifact Correction: Motion artifacts were corrected by applying the SPLINE interpolation method. The specific parameters employed were as follows: TmotionWEI = 0.5 (a weighting coefficient for the motion artifact time window, controlling the temporal smoothness during artifact detection), STDEVthresh = 20 (the signal standard deviation threshold, where signal fluctuations exceeding this value were identified as potential motion artifacts), TMASK = 3 (the duration for masking artifacts, used to mark and overwrite continuous data segments identified as artifacts), and AMPTHRESH = 5 (the signal amplitude threshold, where abrupt signal changes exceeding this amplitude were detected as motion artifacts) [

13].

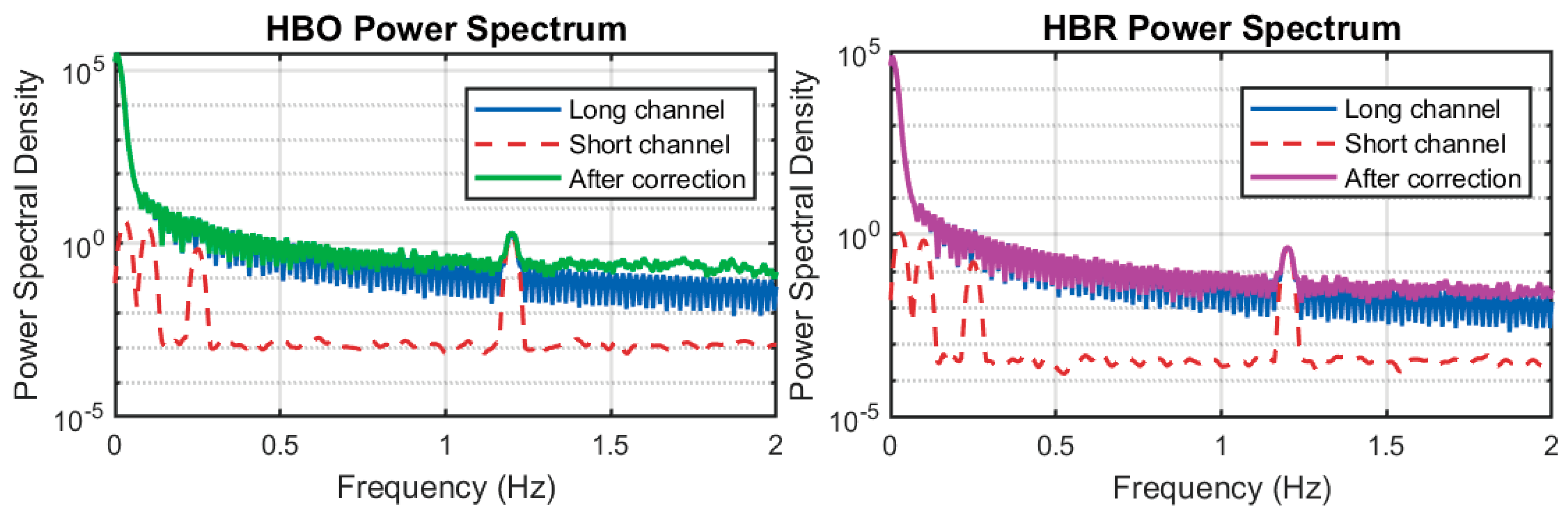

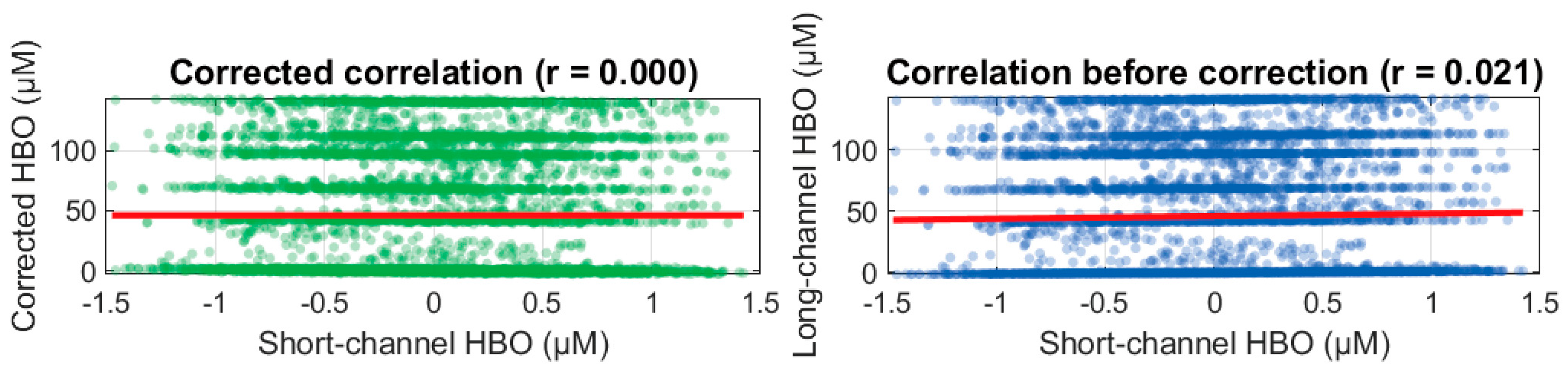

Evaluation of Motion Artifact Correction Efficacy: To assess the impact of SPLINE interpolation on signal quality and to rule out the potential introduction of spurious activation, power spectral analysis was conducted on the oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) concentration change signals, both before and after correction.

Figure 2 illustrates the power spectral density (PSD) for a representative channel, pre- and post-interpolation.

Figure 2 depicts the HbO power spectrum: the short-distance channel (serving as the reference channel dominated by motion artifacts) exhibited significantly lower PSD in the 0~2 Hz frequency band compared to the long-distance channel (the tissue signal channel) and the corrected curve. This indicates that the original long-channel signal contained elevated power components induced by motion artifacts. The high concordance between the post-correction HbO power spectrum (green curve) and the long-channel spectrum (blue) demonstrates that SPLINE interpolation effectively mitigated the power interference from motion artifacts without introducing substantial additional spectral components.

Figure 2 shows the HBR power spectrum: the corrected curve (purple) and the long-channel curve (blue) showed good consistency in PSD within the 0~2 Hz range, while the short-channel power remained markedly lower. This further validates the efficacy of the correction in suppressing motion artifacts. The absence of anomalous power peaks or extra frequency components in the post-correction spectra suggests that SPLINE interpolation did not introduce significant spurious frequencies or power components, indirectly reducing the risk of false activation. Across all datasets, segments requiring interpolation correction accounted for 5% of the total data volume. In the context of task-based data, this low percentage indicates generally good overall data quality, and the minimal interpolation further diminishes the likelihood of false activation.

Detrending: A linear detrending algorithm was applied to remove linear trend components from the signals, which typically arise from instrumental drift or slow physiological fluctuations (e.g., respiration, heart rate baseline wander).

Block Averaging: Accounting for the inherent data acquisition delay of the equipment, the temporal window for each stimulus-locked signal block was defined from −200 frames (pre-stimulus onset, preserving the baseline) to 1200 frames (the effective stimulus presentation period, constituting the signal interval after baseline subtraction). Furthermore, based on the Coefficient of Variation (CV) results, data blocks labeled as ‘bad segments’ (indicating substandard signal quality) were excluded from subsequent averaging.

Baseline Correction: Baseline correction was performed using a linear fitting approach. The baseline time interval was defined from −2 s to 0 s relative to stimulus onset (i.e., the 2 s period immediately preceding stimulus presentation was used as the baseline for calibrating the relative signal changes post-stimulus).

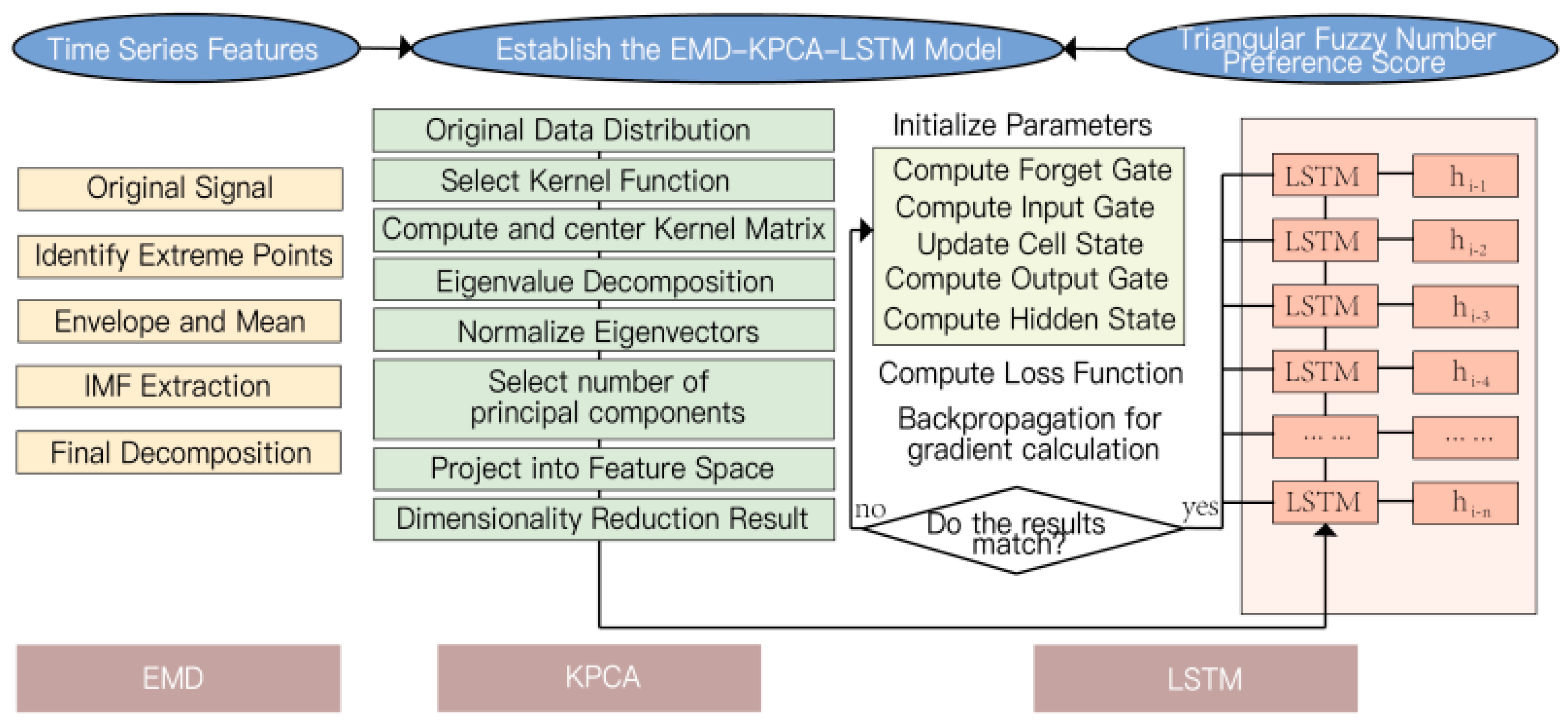

2.3. EMD-KPCA-LSTM Model

This study collected 94 sample data points from 35 participants. The raw feature dimension was 8, comprising multimodal eye-tracking and fNIRS data. The target variable was the user’s preference rating on a 7-point Likert scale [

14,

15].

Model Input Features: The eight features are as follows: (1) Total Fixation Duration, (2) Number of Fixations, (3) Average Fixation Duration, (4) Saccade Path Length, (5) Pupil Diameter Change, (6) Mean Oxygenated Hemoglobin Concentration (Δ[HbO]), (7) Mean Deoxygenated Hemoglobin Concentration (Δ[HbR]), and (8) Brain Activity Asymmetry Index (the difference in average Δ[HbO] between the left and right prefrontal cortex). These features were calculated for each trial (each participant viewing each image) to form the model’s input vector [

16].

Data Splitting and Validation Strategy: Two validation strategies were employed to ensure robust model evaluation:

- (1)

Subject-Based Stratified 5-Fold Cross-Validation: The 35 participants were randomly divided into 5 folds (7 participants per fold). In each iteration, data from 4 folds (~75 samples) were used for training, and the remaining fold (~19 samples) was used for testing [

17]. This process was repeated 5 times, ensuring each participant’s data was included in the test set once. Performance metrics are reported as the mean ± standard deviation across the 5 folds, serving as the primary evaluation method.

- (2)

Hold-Out Independent Test Set: An additional random split allocated 75% of the data for training and 25% for testing. This set was used to demonstrate the final model’s performance after hyperparameter tuning and for comparison with commonly used methods in the literature. All hyperparameter optimization was performed on the training folds of the cross-validation [

18,

19].

Data were normalized using Z-score normalization, with the mean and standard deviation calculated from the current training fold.

2.3.1. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD)

Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) is employed to decompose the complex temporal evolution of affective preferences into Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) across different time scales [

20]. Within the theoretical framework of this study, we propose an interpretative hypothesis: the different IMF components obtained from the decomposition may correspond to distinct levels of cognitive and affective responses [

7]. Specifically, high-frequency components can be interpreted as reflecting immediate emotional reactions, medium-frequency components may correspond to cognitive processing, while low-frequency components can be construed as reflecting deep-seated values and esthetic tendencies [

21]. Based on this, the study attempts to conceptually associate these hierarchical levels with the three factors of Comfort, Elegance, and Refinement, respectively. [

22]. Each IMF must satisfy two conditions: the number of extrema and the number of zero-crossings must either be equal or differ at most by one, and the mean of the envelope defined by the local maxima and the envelope defined by the local minima must be zero [

23,

24].

A zero-padding strategy was applied during decomposition to align IMF components of variable lengths, primarily for its advantage in preserving phase information. The maximum number of IMFs was set to 5, and spline interpolation was used within the EMD algorithm.

EMD Parameter Details: The maximum number of IMFs was experimentally determined to be 5. Testing showed that using 5 IMFs achieved the optimal balance between reconstruction error and the physical interpretability of the components on the training set. The zero-padding strategy was implemented as follows: IMF sequences shorter than the maximum sequence length T_max were zero-padded at the end to reach T_max. This end-padding in the time domain corresponds to sinc function interpolation in the frequency domain, which better preserves the instantaneous frequency characteristics of the IMFs and avoids phase distortion compared to linear or spline interpolation. A masking mechanism was applied at the network input to ensure the padded portions did not contribute to loss calculation.

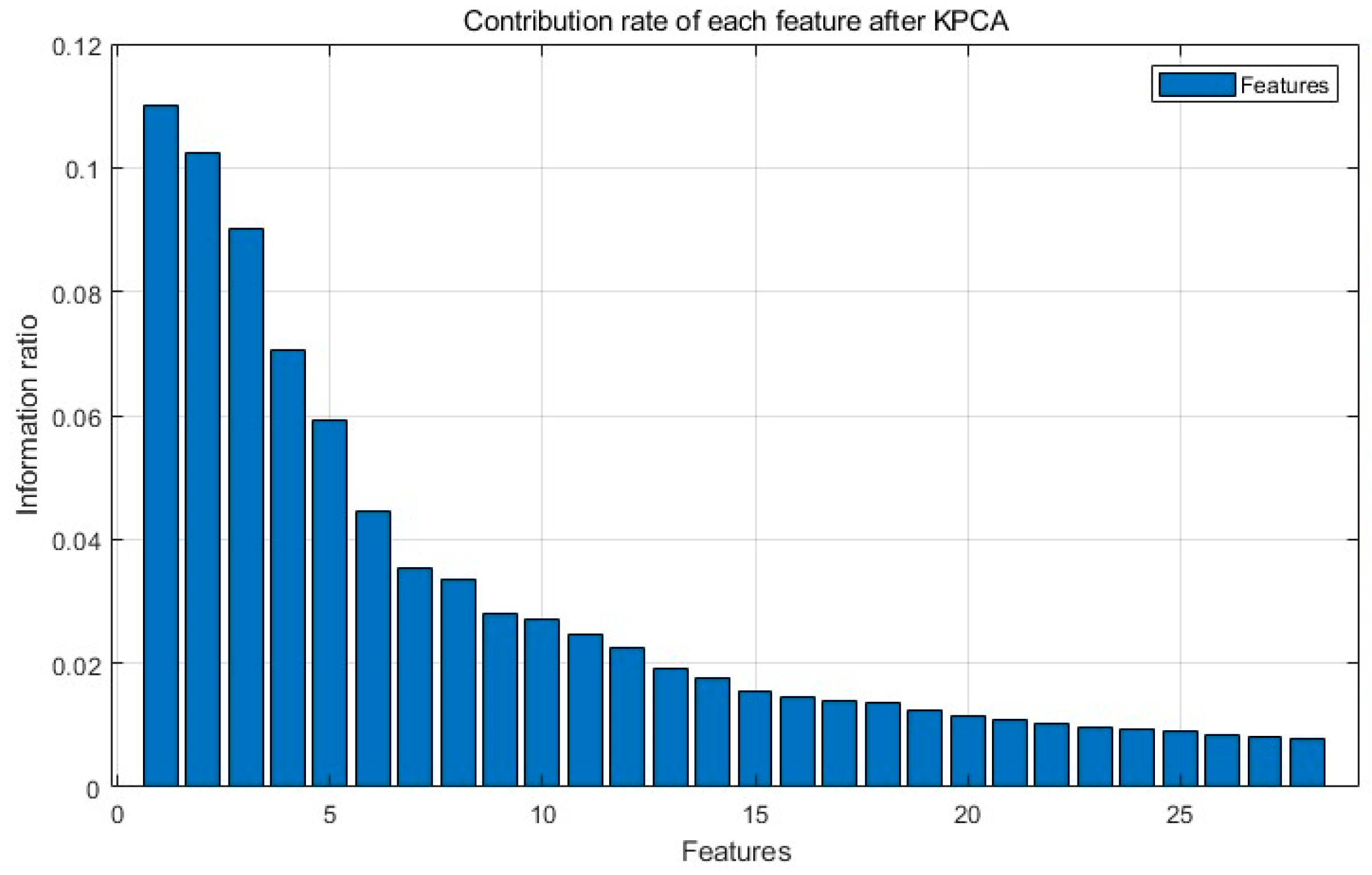

2.3.2. Kernel Principal Component Analysis (KPCA)

Emotional preference data often exhibit complex nonlinear structures, which are poorly handled by the linear assumptions of traditional PCA. KPCA addresses this by mapping the data into a high-dimensional Hilbert feature space via a kernel function, thereby transforming nonlinear relationships into linearly separable problems [

25].

In this study, the Gaussian kernel function was selected. The kernel parameter σ was optimized to 0.5 through grid search combined with 5-fold cross-validation. The top N principal components required to achieve a cumulative contribution rate exceeding 92% were retained, effectively reducing the high-dimensional feature space to N dimensions, eliminating redundancy while preserving essential information [

26].

2.3.3. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Network

LSTM was used to capture long-term dependencies within emotional preference sequences [

27]. Its gating mechanism effectively manages memory and forgetting effects during preference evolution: the Forget Gate controls the retention of historical preference information, the Input Gate regulates the storage of new preference inputs, and the Output Gate governs the output of the current preference [

28].

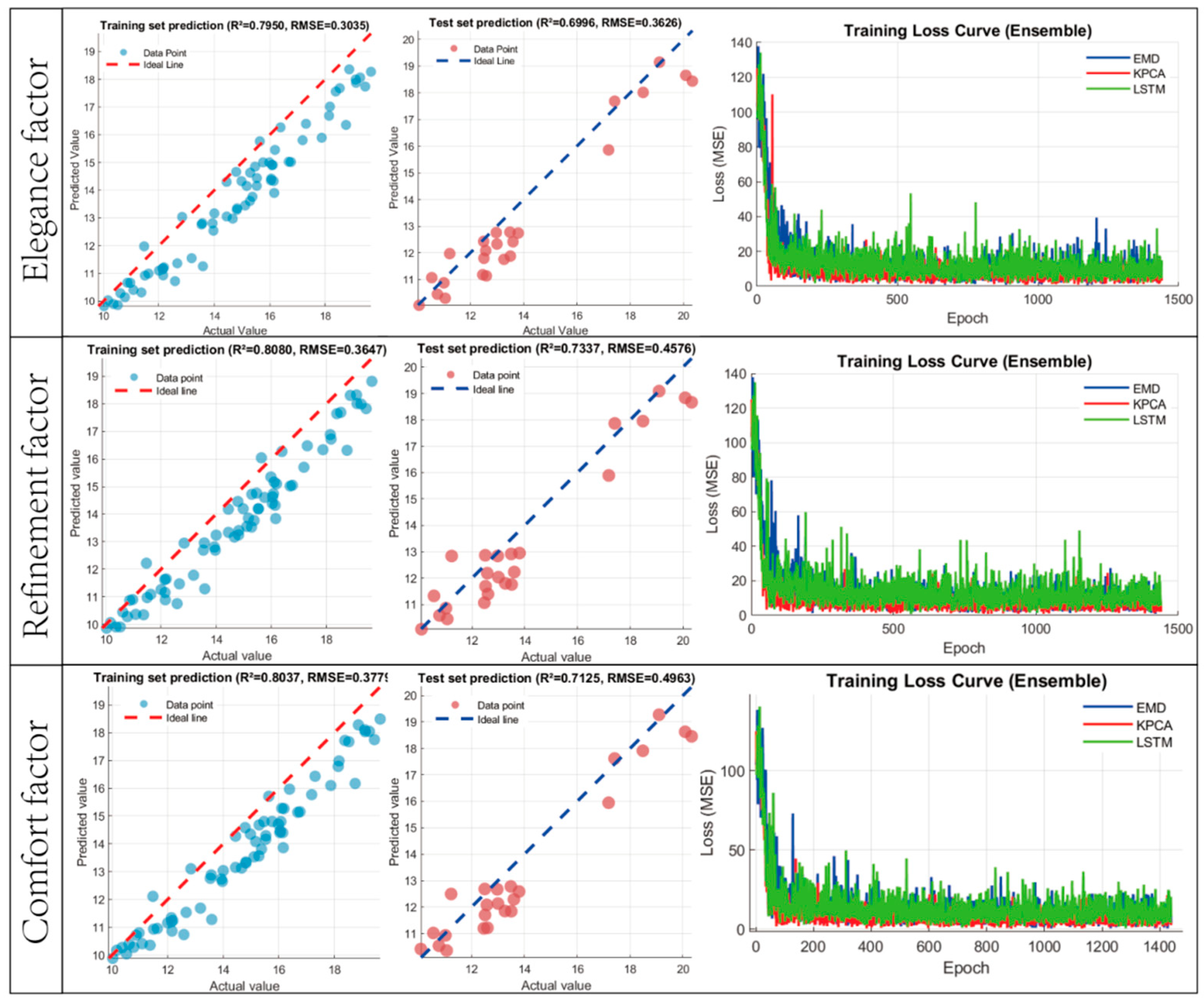

An ensemble system comprising three heterogeneous LSTM sub-models was constructed, with the final output being the average of their predictions [

29]. The specific configurations are as follows:

Model 1: A two-layer stacked LSTM (40 and 30 hidden units), followed by two fully connected layers (20 and 10 nodes). Dropout rates were set to 0.4, 0.3, and 0.2 sequentially [

30].

Model 2: A single-layer LSTM (50 hidden units), followed by two fully connected layers (25 and 12 nodes). Dropout rates were set to 0.5, 0.4, and 0.3 sequentially.

Model 3: A single-layer LSTM (45 hidden units), followed by three fully connected layers (30, 18, and 8 nodes). Dropout rates were set to 0.45, 0.35, and 0.25 sequentially [

31].

A unified training configuration was applied:

- (1)

Optimizer: Adam.

- (2)

Initial Learning Rate: 0.004.

- (3)

Learning Rate Decay: Multiply by a factor of 0.3 every 40 epochs.

- (4)

Maximum Epochs: 180.

- (5)

Early Stopping: Halt training if validation loss shows no decrease for 15 consecutive epochs.

- (6)

Regularization: L2 coefficient of 0.005; gradient clipping threshold of 1.

- (7)

Batch Size: Adaptively adjusted between 8 and 16 based on training set size.

- (8)

Loss Function: Mean Squared Error (MSE).

- (9)

Random Seed: Fixed at 42 to ensure reproducibility.