1. Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) was recognized by the World Health Organization as the leading cause of disability worldwide, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 4.4% in the general population [

1]. Symptoms of MDD included persistent low mood, anhedonia (i.e., diminished interest or pleasure), changes in appetite and sleep patterns, fatigue, psychomotor agitation or retardation, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, diminished ability to concentrate, and suicidal ideation. Depression was projected to become the leading cause of global disease burden by 2030 [

2]. However, a meta-analysis of 50,371 patients across 118 studies reported a depression recognition rate of only 47.3% [

3], which highlighted the urgent need for more effective and objective diagnostic methods to address the high incidence and low recognition rate of depression.

Currently, depression diagnosis relies primarily on subjective assessment methods, such as clinician–patient interviews and standardized psychiatric questionnaires [

4]. However, these approaches were susceptible to physician bias and patient-related factors, such as denial or symptom camouflage, which reduced diagnostic accuracy and objectivity [

5]. In recent years, advancements in neuroimaging technologies, including positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and electroencephalography (EEG), have enabled more objective, non-invasive studies of brain function and related diseases [

6]. For instance, PET could detect metabolic abnormalities in specific brain regions by monitoring brain metabolic activity [

7], while MRI provides high-resolution images to assess structural changes in gray and white matter [

8]. EEG offered a distinct advantage by capturing real-time electrical activity from cortical neurons, allowing the detection of synchronized neuronal oscillations and abnormal firing patterns [

9]. These tools have proven valuable for exploring the neurobiological basis of MDD and for providing objective diagnostic support [

10]. However, PET and MRI were costly and required specialized technical support [

11]. Moreover, PET involves exposure to radioactive tracers, posing additional cost and safety concerns [

12]. In contrast, EEG was non-invasive, cost-effective, and simple to administer, offering high temporal resolution that made it ideal for investigating the dynamic properties of brain bioelectrical activity [

13]. In particular, a close relationship has been found between EEG signal characteristics and MDD [

14]. For instance, several studies have reported significant EEG abnormalities in MDD patients, particularly in bilateral temporal regions [

15,

16,

17]. Compared to healthy controls, MMD patients generally exhibit elevated EEG activity in the delta, theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands, with pronounced depression-related signals in the higher frequency alpha and beta bands [

18,

19]. These findings demonstrated that EEG signals contain rich, multidimensional features that were valuable for investigating both the neural mechanisms and diagnostic markers of MDD.

With the continuous development of intelligent detection technologies such as deep learning, numerous studies have extracted features from EEG data to detect neurological disorders. While EEG signals offered insight into linear dynamics in the time and frequency domains, the brain was inherently nonlinear, with cognitive processes driven by complex neuronal interactions. One effective method to capture such nonlinear characteristics was through the construction of functional brain connectivity networks. This approach has shown promise in identifying and monitoring changes in brain function and structure associated with mental disorders [

20]. An EEG-based brain functional network is a macroscopic method that analyzes the association of functional connectivity patterns and neurological disorders. This was often analyzed through graph theory, where electrodes were treated as network nodes and signal connections between them as edges [

21,

22]. For example, Kalpana et al. used 16-channel resting-state EEG data to analyze functional connectivity in depressed individuals and found that the alpha-band networks had reduced clustering coefficients and shorter path lengths [

23]. Similarly, Guo et al. observed shorter path lengths and higher global efficiency in the brain networks of MDD patients, alongside reduced node efficiency in the frontal regions [

24]. These findings supported the utility of brain functional networks in identifying MDD-specific patterns of information flow. However, most of these studies utilizing resting-state EEG signals construct brain networks based on a fixed-length time window [

25]. This overlooked the dynamic and state-dependent nature of brain activity, even during rest [

26]. Since different mental states may occur within varied durations, fixed-window approaches failed to adequately capture brain functional connectivity patterns under different states and thus were unable to effectively characterize the nonlinear features associated with specific brain neurological diseases [

27]. In contrast, constructing networks using microstate sequences as windows—that is, dividing time windows based on the brain’s actual functional states—aligns brain state transitions across spatiotemporal domains. This approach respects the brain’s inherent state dependency and dynamics, more accurately reflecting connectivity structures within specific microstates rather than representing a “blended average of multiple states” [

28]. Research utilizing microstate windows to construct a series of functional connectivity networks and analyze their spatiotemporal variability demonstrates that microstate-based windows better reflect disease-related brain network dynamics than fixed-time-window methods [

29].

The spatial distribution of EEG scalp potentials reflected underlying neuronal activity and could be used to identify recurring topographical patterns, representing the brain in different states of brain activity. Brain activity in the resting state could be represented by four alternating time sequences of brain topographies, called microstates [

30]. Time series composed of the same microstates indicate that the brain is in a similar state of neural activity. Many studies have explored the neural mechanisms of neurological disorders by analyzing the temporal patterns of microstate presentation. For example, by differentially analyzing the microstate features of closed-eye EEG data from depressed and normal subjects and exploring the correlation with scale scores, Chen Xueying et al. found that relative to healthy controls, depressed patients had a higher number of occurrences and coverage ratios of microstate C, and a higher probability of transitions to other microstates. In contrast, their microstate D had a lower average duration and a lower transition probability to microstate B, along with a reduced number of occurrences. In addition, microstate C and microstate D showed significant correlations with both depression scales and anxiety scales, indicating that EEG microstate-based methods could capture the abnormal brain dynamic properties of patients with depression [

31]. Zhang et al. explored the temporal dynamics of brain network changes in disorders of consciousness and found that EEG microstate analysis could provide an analysis for the further study of brain dynamics changes in patients suffering from disorders of consciousness [

32]. Microstates could effectively characterize the changes in brain activity associated with neurological diseases, and provide a key technical tool for portraying the dynamics of functional brain networks. The definition of microstates was closely related to the characteristics of brain networks, and their stability over a short period of time could be characterized by the same or similar patterns of brain functional connectivity [

33,

34,

35]. We believed that since the same microstate sequence reflected a similar pattern of brain activity, constructing symmetrical microstate–brain networks using the same microstate sequence as a time window could obtain more accurate nonlinear features in the time and space domains, and thus effectively characterize depressive brain activity.

In this study, we analyzed resting-stage EEG data to identify four microstate types in MDD patients. Symmetrical microstate–brain networks were then constructed for each microstate by using time series of four types of microstates as dynamic windows. And then we compared microstate features (duration, occurrence, coverage, transition probability) and brain network parameters (clustering coefficient, characteristic path length, local and global efficiency) between MDD patients and healthy controls to analyze the characteristics of the changes in the brain activities of the patients with MDD and the topological patterns of the functional connectivity. By integrating microstate and brain network features, we captured the temporal and spatial characteristics of MDD-related brain activity and validated their diagnostic utility using our previously proposed MSCAN model. Our study provided a computation method for the intelligent diagnosis of MDD and a reference for clinical research on the neural mechanisms of MDD. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

We proposed a novel method to construct symmetrical microstate–brain networks using EEG microstate time series as dynamic windows, resulting in four distinct brain networks (A, B, C, and D) that more accurately reflect the brain activity patterns associated with MDD.

- (2)

The metrics analysis of microstate and network revealed that MDD patients exhibit frequent microstate transitions, reduced network efficiency, and high energy consumption, which may suggest greater internal focus and reduced responsiveness to external stimuli, hallmarks of strong desires to dissociate from the external environment.

- (3)

By jointly analyzing temporal and spatial features of symmetrical microstate–brain networks, we constructed a time-spatial representation of MDD-related brain activity. Using this time-spatial representation, our proposed MSCAN model achieved a significantly improved diagnostic performance for MDD detection.

2. Materials and Methods

To investigate the role of symmetrical microstate–brain networks in major MDD, we employed a structured analytical pipeline. Resting-state EEG signals were first preprocessed following standard protocols. We then calculated the Global field power (GFP) and extracted its peak time points to obtain EEG topographies with high signal-to-noise ratios. These topographies were clustered into four canonical microstates (A, B, C, D) using the K-means algorithm. Subsequently, the full EEG time series of each participant was segmented by assigning each data point to the best-fitting microstate, resulting in a temporal sequence composed of four distinct microstate classes. Each microstate provides a transient but stable representation of brain activity. We quantified their temporal characteristics using four parameters: duration, occurrence, coverage, and transfer. Unlike conventional brain network analyses that rely on fixed-length time windows, we used the actual duration of each microstate as a dynamic window for network construction. For each microstate type, a corresponding 80 × 80 functional connectivity matrix was computed using PLV values between selected EEG channels, resulting in four microstate-specific networks: BN_A, BN_B, BN_C, and BN_D. Each network was characterized by computing graph-theoretic measures, including the clustering coefficient, characteristic path length, and both local and global efficiency. These features, along with the microstate parameters, were used to capture both linear and nonlinear patterns of brain activity. All extracted features were integrated into our previously developed MSCAN model for MDD classification. This model leverages multiscale information from EEG signals, microstates, and functional connectivity to support intelligent depression diagnosis. An overview of the full methodological pipeline is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

The dataset used in this study was obtained from the MODMA dataset [

36], a publicly available EEG dataset for depression research provided by the Key Laboratory of Wearable Computing at Lanzhou University. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Lanzhou University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The dataset included EEG recordings from 24 patients diagnosed with clinical depression and 29 healthy controls, selected based on Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scores, as well as clinical diagnoses made by physicians. EEG data were collected using a 128-channel HydroCel Geodesic Sensor Net system with a Net Station device, sampled at 250 Hz. All recordings were conducted in a quiet, dimly lit, electromagnetically shielded room. Participants were seated and instructed to remain still with eyes closed for approximately five minutes, while staying awake and avoiding active thoughts or body movements to minimize electromyography and electrooculography artifacts.

Statistical analyses were conducted to compare demographic and clinical characteristics between the depression and control groups. As summarized in

Table 1, there were no significant differences in age or sex between the groups. However, patients with depression exhibited significantly higher PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores compared to the control group.

EEG preprocessing was conducted using EEGLAB (v14.1.2) [

38]. First, electrode locations were standardized using a default electrode position file. Segments contaminated by noise, motion artifacts, or other interferences were manually identified and removed. A band-pass filter (1–50 Hz) was applied to remove the industrial frequency interference and high-frequency noise. Subsequently, to further eliminate artifacts such as blinks and eye or head movements, independent component analysis was performed on the 128-channel data, and noise-related components were removed. A whole-brain averaging reference was used to reduce individual electrode voltage deviation effects on the overall data and improve signal stability and reliability. Data were normalized to ensure consistency and comparability with the dimensions N × T × C, where N is the number of subjects, T is the number of sampling points, and C is the number of channels [

37].

2.2. Microstate Analysis

2.2.1. Calculation of Microstates

The EEGLAB microstate plugin and MATLAB (vR2020b) capability were used to implement microstate analysis. The global field power (GFP) was first computed:

where

is the mean voltage across all electrodes at time,

is the number of electrodes, and

is the EEG voltage vector at time

. There is a favorable link between GFP and signal-to-noise ratio in topographic maps with distinct or many peaks. In order to reduce redundancy and computational strain, topographic maps at GFP peaks were chosen to characterize surrounding EEG signals.

To find representative microstate classes, each topographic map was then geographically grouped. The K-means clustering algorithm was applied to group the maps into spatially distinct microstate prototypes. Based on previous studies and cross-validation results on our datasets, we selected four microstate classes, which explained the maximum amount of variance while maintaining interpretability [

39,

40]. Each EEG time point was classified into one of four microstates by maximal spatial correlation with prototype maps, producing microstate label time series for all MDD and healthy control participants.

2.2.2. Calculation of Microstate Parameters

Several quantitatively useful factors of neurological importance can be derived from EEG data by fitting microstate regression models. We computed four microstate parameters: length, occurrence frequency, coverage, and transition probability in order to compare differences between MDD and healthy control (HC) groups [

41,

42].

- (1)

Duration

Duration, typically measured in seconds or milliseconds, represents the average time a microstate persists per occurrence [

41,

42], reflecting its temporal stability and involvement in overall brain dynamics. Its calculation is as follows:

where

is the number of occurrences of the microstate and

is the duration at the

occurrence.

- (2)

Occurrence

The occurrence rate represents the average number of microstate appearances per second [

41,

42], quantitatively describing their temporal distribution and dynamic characteristics. Its calculation is as follows:

where T is the total observation period (measured in seconds) and M is the total number of instances of the microscopic condition.

- (3)

Coverage

Coverage, which is usually stated as a percentage, measures the percentage of total record time that a particular microstate occupies [

41,

42]. Its importance and dominance in brain dynamics are reflected in this indication. The following is how it is calculated:

where

is the total duration of the microstate, and

is the total recording time.

- (4)

Transfer

The transition probability captures the possibility of switching from one microstate to another, revealing dynamic switching behavior between brain states [

41,

42]. It is calculated as follows:

where

denotes the probability of transitioning from microstate

to

,

is the number of observed transitions, and

is the total number of transitions originating from microstate

.

2.3. Brain Network Analysis

2.3.1. Construction of Brain Network Based on Symmetrical Microstate Time Series

Traditional brain network construction methods often use fixed-length time windows [

43,

44]. However, the EEG signal within a fixed-time window may fail to reflect similar activity states in the brain, possibly causing the brain networks to mask the changes over time. Here, we proposed a method that leverages microstate-informed time windows for network construction.

Following microstate segmentation, the EEG signals of each participant were divided into segments based on the time points associated with each microstate class. These segments, corresponding to variable-length microstate windows, were then used to calculate functional connectivity using the PLV. Due to the fast transient changes and low signal-to-noise ratio of the participants’ EEG signals, PLV has strong frequency sensitivity and is able to analyze the phase components individually. It is calculated as follows:

The number of time points , where denotes the index of the th time point, represents the instantaneous phase of Signal 1 at the th time point, denotes the instantaneous phase of Signal 2 at the th time point, is the phase difference between the two signals, is the complex number obtained by mapping the phase difference onto the unit circle (Euler’s formula), and is the average of the phase differences across all time points.

In our previous work, we conducted a channel selection process on the 128-channel MODMA EEG dataset and identified 80 channels that were most informative for the detection of MDD. Building on this result, the present study used these 80 channels as network nodes to construct functional brain networks. Specifically, for each participant, we computed PLV matrices based on EEG signals during four identified microstates. Each matrix was of size 80 × 80, with PLV values representing the connection strengths between channel pairs. The resulting microstate-specific functional networks were denoted as BN_A, BN_B, BN_C, and BN_D, corresponding to microstates A, B, C, and D, respectively.

2.3.2. Calculation of Brain Network Properties

To analyze functional connectivity patterns and identify spatial features associated with MDD, we calculated the following attributes of the brain network: clustering coefficient [

45], characteristic path length [

45], and local and global efficiencies [

46].

- (1)

Clustering coefficient

The clustering coefficient quantifies the degree to which a node’s neighbors are interconnected [

45]. A higher clustering coefficient indicates more connections, forming a relatively tight local network structure, while a lower clustering coefficient implies a more random connection. It is calculated as follows:

where

denotes the number of connections between neighbors of node

. The degree of node

is

.

- (2)

Characteristic Path Length

The characteristic path length is a critical parameter for assessing the internal structure of a network and plays a key role in the efficiency of information transfer [

45]. The shortest path between two nodes represents the optimal path for transmitting information, enabling rapid communication while conserving system resources. Specifically, the path with the least number of edges between two nodes

and

is defined as the shortest path, and the number of edges on that path represents its length, denoted by

. The characteristic path length

of the network refers to the average value of the shortest path length between any two nodes in the network, which is an important indicator of the overall efficiency of the network. It is calculated as follows:

where

is the number of nodes and

is the distance between nodes

and

. When the length of the characteristic path is smaller, it means that the information transmission speed of the network is faster.

- (3)

Global efficiency

Global efficiency characterizes the information transmission efficiency of a network on a global scale and is an important indicator of its overall performance [

46]. A higher global efficiency implies a higher connectivity and reliability of information transfer between any two nodes in the network, and information can be propagated more efficiently throughout the network. It is calculated as follows:

where

is the number of nodes and

is the shortest path length between nodes

and

.

- (4)

Local efficiency

Local efficiency is defined as the global transmission efficiency of a node and its surrounding nodes that maintains the information transmission capability within the neighborhood after removing the node [

46]. It is an important index for evaluating the local information transmission capability of nodes in the network and the structural characteristics of the neighborhood. It reflects the local characteristics of the network and describes the connectivity and information flow capacity within the local range where a node is located. It is calculated as follows:

where

is the degree of node

, i.e., the number of nodes directly connected to node

, and

is the shortest path length between nodes

and

in the neighborhood after node

is removed. The local efficiency can reflect the fault tolerance of the network to some extent.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate group-level differences in EEG microstate parameters (duration, occurrence, coverage, and transfer) and in brain network metrics (clustering coefficient, characteristic path length, global efficiency, and local efficiency) between participants with MDD and healthy controls (HC), we performed independent sample t-tests. These comparisons were conducted separately for each microstate (MS_A, MS_B, MS_C, MS_D) and corresponding brain network (BN_A, BN_B, BN_C, BN_D). Statistical significance was determined at a threshold of p < 0.05. Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied where appropriate to account for violations of sphericity, with adjusted degrees of freedom. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22. Additionally, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for each comparison to assess the precision of effect estimates.

2.5. Multiscale Convolutional Attention Network

In this study, we applied the recognition model MSCAN, which we proposed in a previous MDD study [

37], to validate the time-frequency characteristics of depression based on microstate-brain network computation. The MSCAN model includes two key modules: the Multiscale Convolutional Attention (MSCA) and temporal end-aware self-attention (TTSA) modules. As shown in

Figure 2, the MSCA module first extracts spatio-temporal features from the EEG through one-dimensional temporal convolution and one-dimensional spatial convolution. Channel attention enables the model to automatically identify which electrode channels are more discriminative, while spatial attention emphasizes which spatial regions (brain region topology) are more important and suppresses irrelevant areas. The resulting features thus preserve EEG’s temporal dynamics while enhancing the collaborative information between channels and spatial regions. For EEG microstates or brain network features, this enables the model to adaptively focus on the most valuable brain regions at any given moment. When the brain is in a particular microstate, this mechanism helps capture corresponding spatiotemporal coupling features, providing subsequent modules with more discriminative and functionally relevant representations. The TTSA module models the temporal dimension: it first processes the features output by MSCA through two 1D causal convolutional layers to extract local contextual information at each time point, ensuring each point accesses only past information while maintaining temporal alignment. Subsequently, it calculates dependencies between different time points via reshaping and multi-head attention mechanisms, normalizes the weights, and finally restores the data to the same time-series format as the input. Thus, TTSA’s output incorporates not only short- and medium-term context but also integrates long-term temporal dynamics. Combined with MSCA’s spatiotemporal features, the entire model achieves deep fusion of EEG signals across spatial, channel, and temporal dimensions, simultaneously capturing brain region interaction patterns and long-term brain network changes.

2.6. Experimental Validation

To verify that the microstates and brain networks computed in this study could effectively characterize the EEG signals of patients with depression, we used EEG timing signals, microstate parameters, and brain network attributes as data for the detection of depression using the MSCAN model. Specifically, to validate the two brain network construction methods based on microstate time series and fixed time windows, we used the brain networks obtained from these two methods as data for depression detection using the MSCAN model. To verify whether microstates and brain networks can provide effective feature information for the diagnosis of depression, we conducted ablation experiments using three types of data: EEG time-series signals, microstate parameters, and brain network properties. In addition, to validate the generalizability of the spatiotemporal features provided by microstates and brain networks in depression detection, we compared the detection results with and without microstate and brain network data using several State-of-the-Art depression detection models. In this study, we used the Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, and F1-score to evaluate the classification efficiency of MSCAN for MDD.

where true positive (TP) is the amount of positive EEG data predicted by the model as positive samples, false positive (FP) is the amount of negative EEG data predicted by the model as positive samples, false negative (FN) is the amount of positive data predicted by the model as negative samples, and true negative (TN) is the amount of negative EEG data predicted by the model as negative samples [

37].

3. Results and Analyses

3.1. The Parameters of Microstates

Using K-means clustering, we obtained four types of microstates in the MDD and HC groups. In early studies, topography with a right frontal-to-left posterior configuration was labeled as microstate A [

47], and topography with a left frontal-to-right posterior configuration was labeled as microstate B [

48]. Moreover, the topography with a symmetric anterior-to-posterior configuration was labeled microstate C, and the topography that displayed the frontocentral configuration was labeled microstate D [

49,

50]. The topography we obtained here was consistent with these previous studies. Thus, we defined the four types of microstates for the MDD and HC groups as microstates A, B, C, and D, as shown in

Figure 2.

We computed the microstate parameters—duration, occurrence, coverage, and transfer—for each of the four microstate types (A, B, C, and D), and assessed group-level differences between the MDD and HC groups. The statistical results are summarized in

Table 2.

Statistical analyses of EEG microstate parameters between the HC and MDD groups are presented in

Figure 3. Overall, the MDD group demonstrated significant alterations in microstate dynamics, particularly in Duration, Occurrence, and Coverage, across multiple microstate classes. Regarding Duration, MDD patients exhibited significantly shorter durations in MS_B (t = 5.542,

p < 0.0005), MS_C (t = 6.859,

p < 0.0005), and MS_D (t = 8.762,

p < 0.0005), with the most pronounced difference observed in MS_D. Although the reduction in MS_A did not reach statistical significance (t = 1.738,

p = 0.088), a downward trend was still evident. In terms of Occurrence, the MDD group showed significantly increased frequencies in MS_A, MS_C, and MS_D, with the most substantial difference in MS_C (t = −9.293,

p < 0.0005; MDD: 6.0976 ± 0.3715 occurrences/s vs. HC: 5.2992 ± 0.2513). Notably, the Occurrence of MS_B did not differ significantly between groups (t = −1.033,

p = 0.306). Regarding Coverage, MDD patients exhibited a significant reduction in MS_A (t = 6.013,

p < 0.0005) and a significant increase in MS_C (t = −10.899,

p < 0.0005), while changes in MS_B and MS_D were not statistically significant (

p = 0.944 and

p = 0.057, respectively). These patterns reflect key differences in the temporal dynamics of microstates between the two groups. As defined by Khanna et al., Duration reflects the mean temporal span of consecutive maps belonging to the same microstate class and is thought to index the synchronous activity of intracortical generators [

51]. Occurrence is a measure of how frequently specific brain configurations are repeatedly engaged; it is the average number of times a microstate appears per second. In this regard, our results imply that MDD patients have shorter-lived but more frequent microstates, suggesting that their brains change between functional states more frequently but less steadily. Notably, these abnormalities were especially pronounced in MS_C, which showed both increased Occurrence and Coverage along with shortened Duration. This pattern may point to a state of hyperactivation of MS_C and an aberrant temporal organization of brain activity in MDD. Such disruptions could reflect instability in specific functional brain networks and may underlie the cognitive and emotional dysregulation characteristic of depressive disorders.

The chart on the right displays the comparative results between the HC and MDD groups across different microstates. Overall, the MDD group exhibited higher values than the HC group in terms of Duration, Occurrence, and Coverage, with significant differences observed across several microstates. Specifically, comparisons between MS_B and MS_D, as well as MS_C and MS_D, revealed highly significant differences in both groups (p < 0.0005). Additionally, the comparison between MS_A and MS_D also reached statistical significance (p < 0.05) in both groups. These findings suggest that individuals with MDD exhibit distinct patterns of EEG microstate dynamics compared to healthy controls, with particularly pronounced alterations observed in MS_B and MS_D.

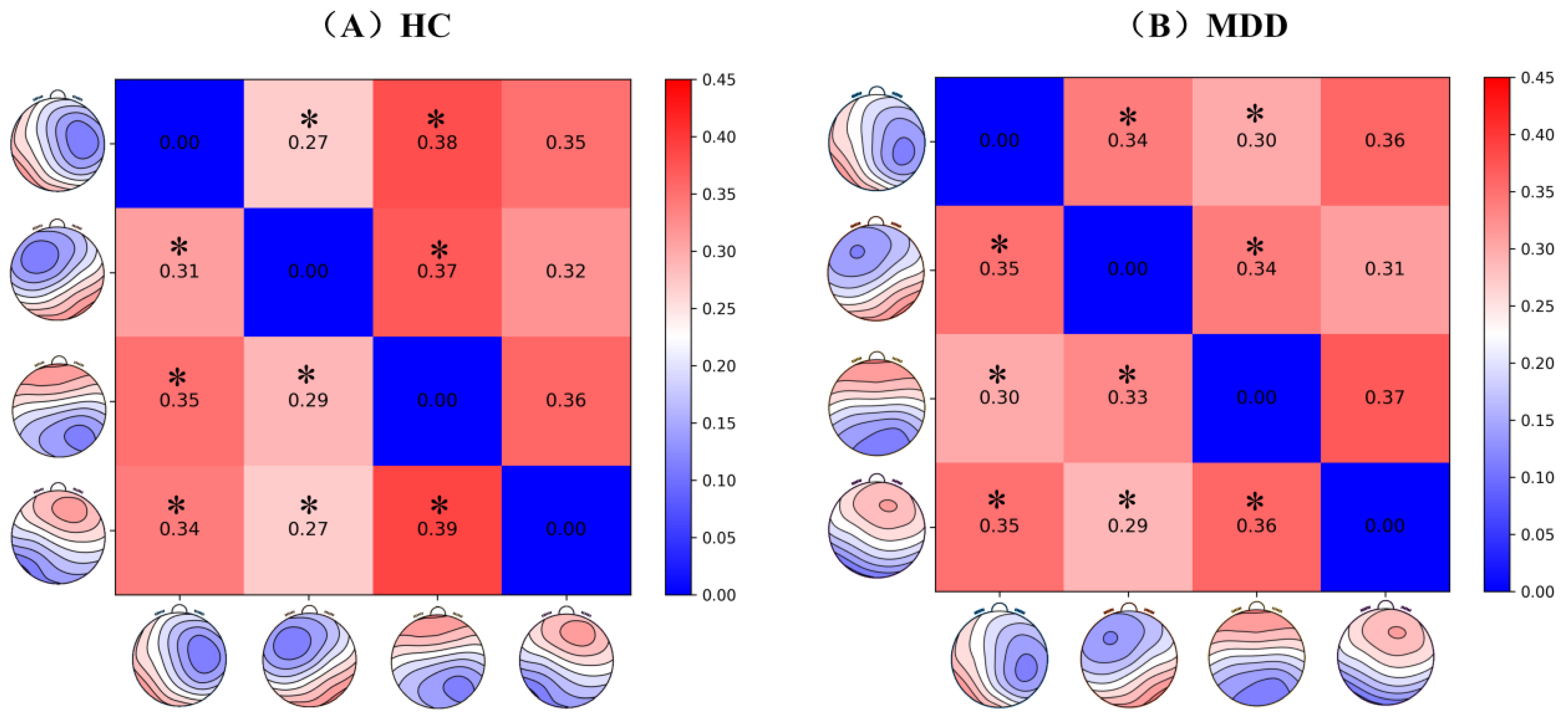

The analysis results for the transition of microstates between the MDD and HC groups are shown in

Table 3.

The statistical results of microstate transition probabilities are illustrated in

Figure 4, revealing significant differences across multiple transition paths between the MDD and HC groups. Specifically, the transition probability from MS_A to MS_B was significantly increased in the MDD group (HC: 0.2748 ± 0.0185 vs. MDD: 0.3316 ± 0.0378, t = −7.145,

p < 0.0005), whereas the transition from MS_A to MS_C was significantly reduced (HC: 0.3771 ± 0.0155 vs. MDD: 0.3124 ± 0.0373, t = 8.508,

p < 0.0005). A similar reduction was observed in the transition from MS_B to MS_C (HC: 0.3661 ± 0.0209 vs. MDD: 0.3300 ± 0.0326, t = 4.880,

p < 0.0005). Additionally, the transition from MS_C to MS_A was significantly lower in the MDD group (HC: 0.3433 ± 0.0162 vs. MDD: 0.3088 ± 0.0231, t = 6.390,

p < 0.0005), as was the transition from MS_D to MS_C (HC: 0.3889 ± 0.0171 vs. MDD: 0.3616 ± 0.0426, t = 3.280,

p = 0.002). Other transitions also exhibited significant group differences, including MS_B → MS_A (t = −2.519,

p = 0.015), MS_C → MS_B (t = −5.237,

p < 0.0005), MS_D → MS_A (t = −2.523,

p = 0.015), and MS_D → MS_B (t = −2.877,

p = 0.006). In contrast, no significant differences were found for transitions MS_A → MS_D (

p = 0.778), MS_B → MS_D (

p = 0.425), and MS_C → MS_D (

p = 0.458). These results suggest widespread abnormalities in microstate transition dynamics in individuals with MDD, characterized by significantly altered probabilities in specific transition pathways. The findings imply impaired neural flexibility and dysfunctional dynamic reconfiguration of brain networks in depression.

3.2. The Properties of Brain Networks

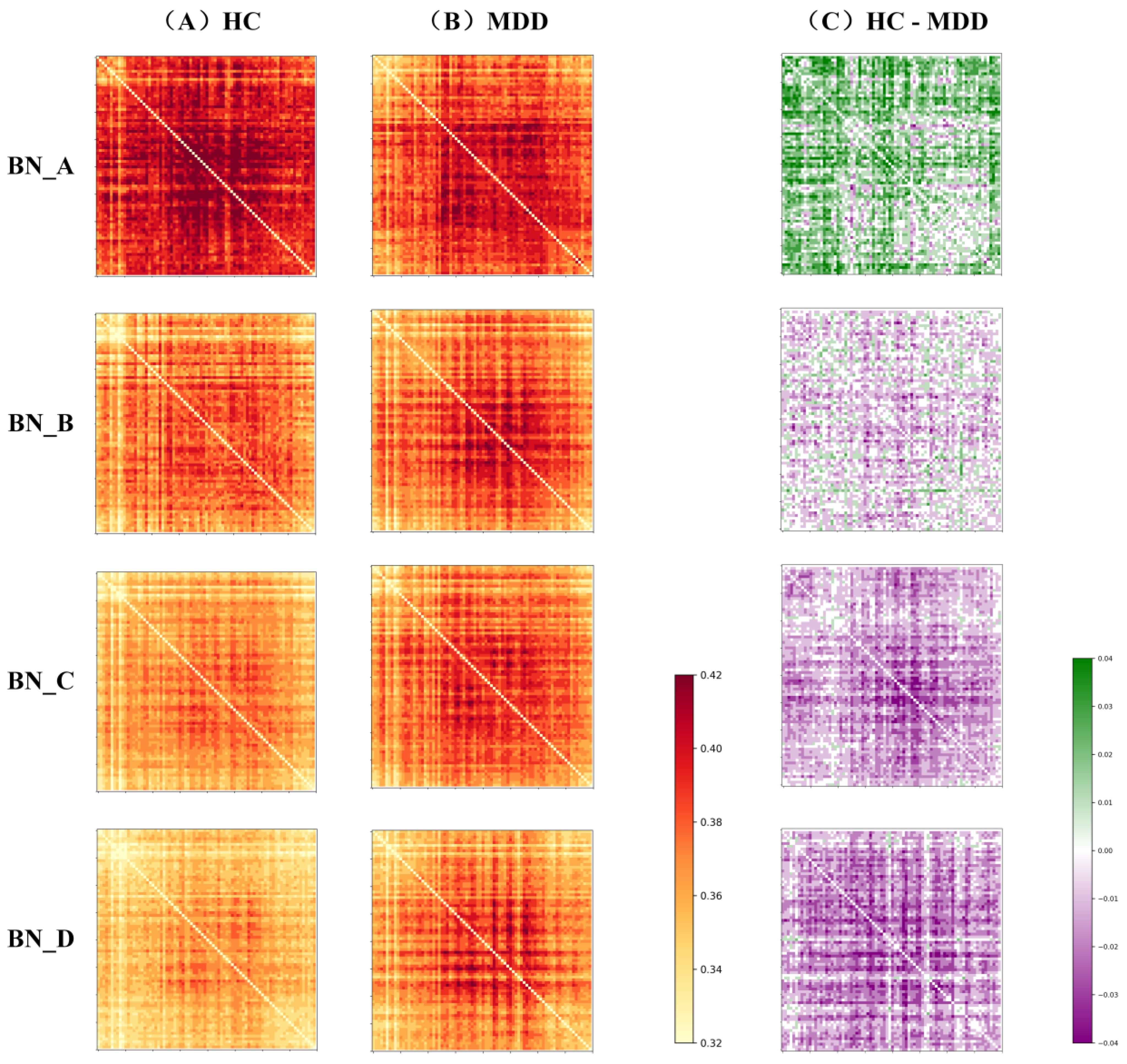

Based on the results of microstate segmentation, the EEG signals of each subject were segmented according to microstates A to D, and the corresponding 80 × 80 functional connectivity matrices were constructed using the PLV method, which were denoted as BN_A, BN_B, BN_C, and BN_D, respectively.

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 illustrate the average connectivity matrices and their differences between the HC group and MDD group under each microstate (HC-MDD), where green color denotes that HC connections are stronger than MDD, and purple indicates that MDD connections are stronger than HC, with darker colors indicating more significant differences. According to the results, there is a significant functional remodeling of the brain network in depressed patients in these two neural states. The differences between the BN_A and BN_B states were the most noticeable, displaying a wide range of significant connection differences in the difference matrix. The differences in the BN_C state were more uniformly distributed and did not show a significant shift, indicating that the effect on the brain network structure in this stage is relatively weak. The BN_D state, on the other hand, showed localized variance changes, and the overall network maintained strong stability despite the significant connection strength in some regions. The above results suggest that MS_A and MS_B may more sensitively reflect the abnormal connectivity characteristics of depressed patients during specific neurodynamic processes, and have a high potential for identification.

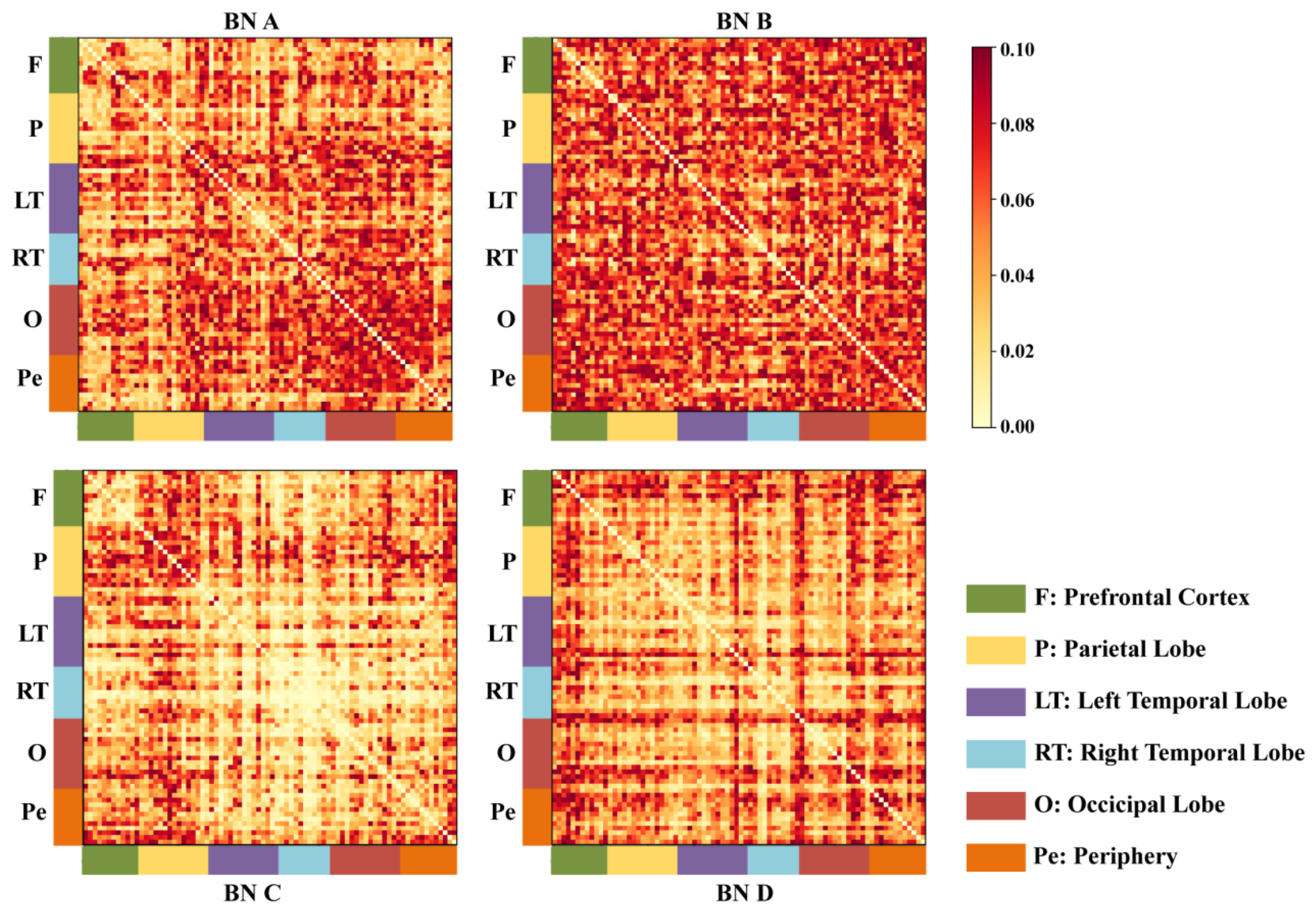

In this paper, we compared the differences in connectivity between various brain regions in the MDD group and the HC group under different microstates, and the results of the analysis are detailed in

Table 4.

As shown in

Figure 7, the results of the analyses indicate that the connectivity of the prefrontal, left temporal lobe, right temporal lobe, and peripheral regions was significantly enhanced or abnormal in the MDD group under MS_A and MS_C, suggesting that these microstates may be involved in the functional reorganization or abnormal activity associated with depression. MS_D mainly exhibited localized connectivity differences in the occipital and peripheral regions, although the overall network connectivity was relatively stable. In contrast, the differences in MS_B were smaller, suggesting that depression had a more limited effect on brain region connectivity. These results suggest that patients with depression experience significant changes in brain connectivity patterns across microstates, particularly in MS_A and C, and that such changes may be closely related to the pathomechanisms of depression.

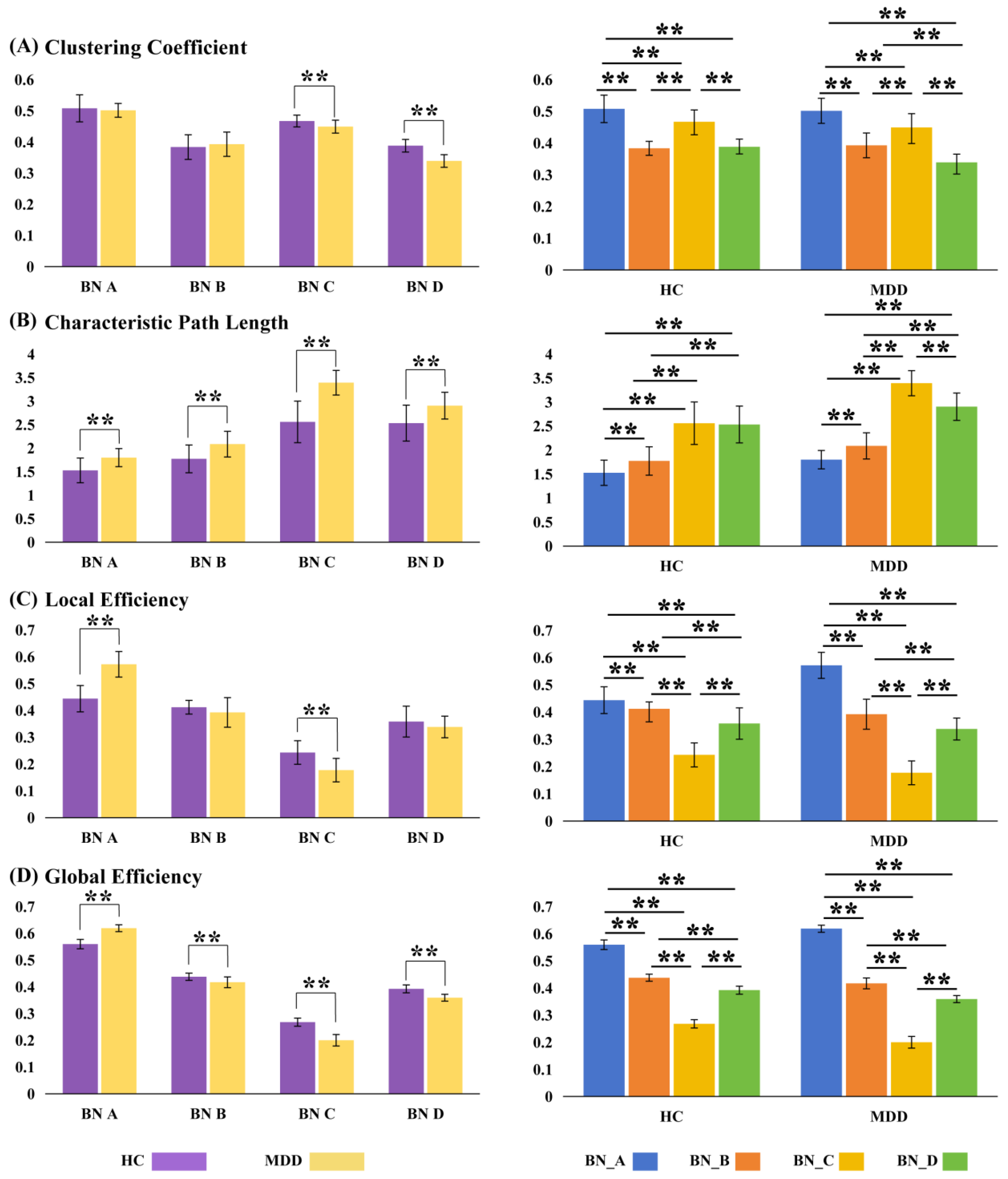

In graph theory-based methods for analyzing complex brain networks, the characteristic path length and clustering coefficient are the most commonly used metrics that reflect the basic principles of functional brain networks, that is, functional integration and functional separation. Other important indicators of brain networks include global and local efficiency. In this study, the characteristic path length, clustering coefficient, global efficiency, and local efficiency were extracted from the brain network to quantify its structural characteristics and functional efficiency of the brain network. To compare the differences in network properties between the two groups in MS_A, MS_B, MS_C, and MS_D, a two-sample t-test was used to analyze the results, which are detailed in

Table 5.

As illustrated in

Figure 8, statistical analyses were performed to compare the topological properties of brain functional networks between the HC and MDD groups. The results revealed significant alterations in BN_C among MDD patients. Specifically, the clustering coefficient was significantly reduced (HC: 0.4672 ± 0.0190 vs. MDD: 0.4492 ± 0.0208, t = 3.284,

p = 0.002), while the characteristic path length was significantly increased (HC: 2.5584 ± 0.4423 vs. MDD: 3.3920 ± 0.2619, t = −8.121,

p < 0.0005). Furthermore, both local efficiency (HC: 0.2428 ± 0.0440 vs. MDD: 0.1771 ± 0.0438, t = 5.419,

p < 0.0005) and global efficiency (HC: 0.2678 ± 0.0153 vs. MDD: 0.2001 ± 0.0216, t = 13.323,

p < 0.0005) were markedly decreased in the MDD group. These topological disruptions suggest reduced efficiency in information processing and increased energy consumption within BN_C in individuals with depression. Taken together with prior research indicating that BN_C is associated with self-referential thinking, and with our present findings that MS_C in the MDD group was characterized by shorter durations but higher occurrences, it is plausible that patients with MDD may engage in frequent, yet inefficient, self-referential cognitive processes. This may represent a critical neural mechanism underlying their impaired cognitive functioning.

The results showed that compared to the HC group, the functional connectivity pattern of BN_C in the MDD group changed. The overall BN_C in patients with MDD showed a decrease in the clustering coefficient, local efficiency, and global efficiency, and an increase in the length of the characteristic path. From the viewpoint of graph theory, this characteristic network connection pattern becomes less optimized with lower efficiency and higher consumption when processing information, which is not conducive to the efficient transmission of information. The BN_C is constructed based on the MS_C time series; therefore, its structure reflects the functional connectivity pattern of the brain in MS_C. Studies have shown that MS_C is associated with task-negative thoughts, mind wandering, self-related thoughts, and emotional and interoceptive processing. Compared to the HC group, the lower mean duration, increased incidence, and coverage of MS_C in the MDD group suggest that the MDD group had a greater percentage of brain activity in MS_C, but was in MS_C for a short period at a time, or that the MDD patients were frequently in the process of transition to MS_C. Combined with the cognitive significance of MS_C, these results may suggest that individuals with MDD are frequently and repeatedly in a state of self-consciousness and that, in this state, the brain’s information processing mode is in a state of low efficiency and high energy consumption.

MS_D is primarily associated with executive processes, such as working memory, cognitive control, reorientation of attention, and detection of behaviorally relevant stimuli [

52]. A previous study [

53] observed a negative association between the ARSQ domain of Self and the duration of MS_D, indicating that less MS_D is associated with greater dissociation from the external environment and stronger internal mentation during the eyes-closed resting state. Moreover, in the present study, the occurrence of MS_D was higher in the MDD group than in the HC, which is consistent with the results of a previous study [

54]. Milz et al. observed a higher occurrence rate of MS_D during no-task resting than during object visualization. The authors have associated microstate D with increased interoceptive processing. In this study, we observed a decreased duration and increased incidence of MS_D in the MDD group, potentially corresponding to deficits in cognitive control. This may account for both a general impairment in goal-directed behavior and a specific bias towards internal thought at the expense of neglecting the external world [

55].

3.3. Effectiveness of Brain Networks Constructed Based on Microstate Time Series and Fixed Time Windows in the Diagnosis of Depression

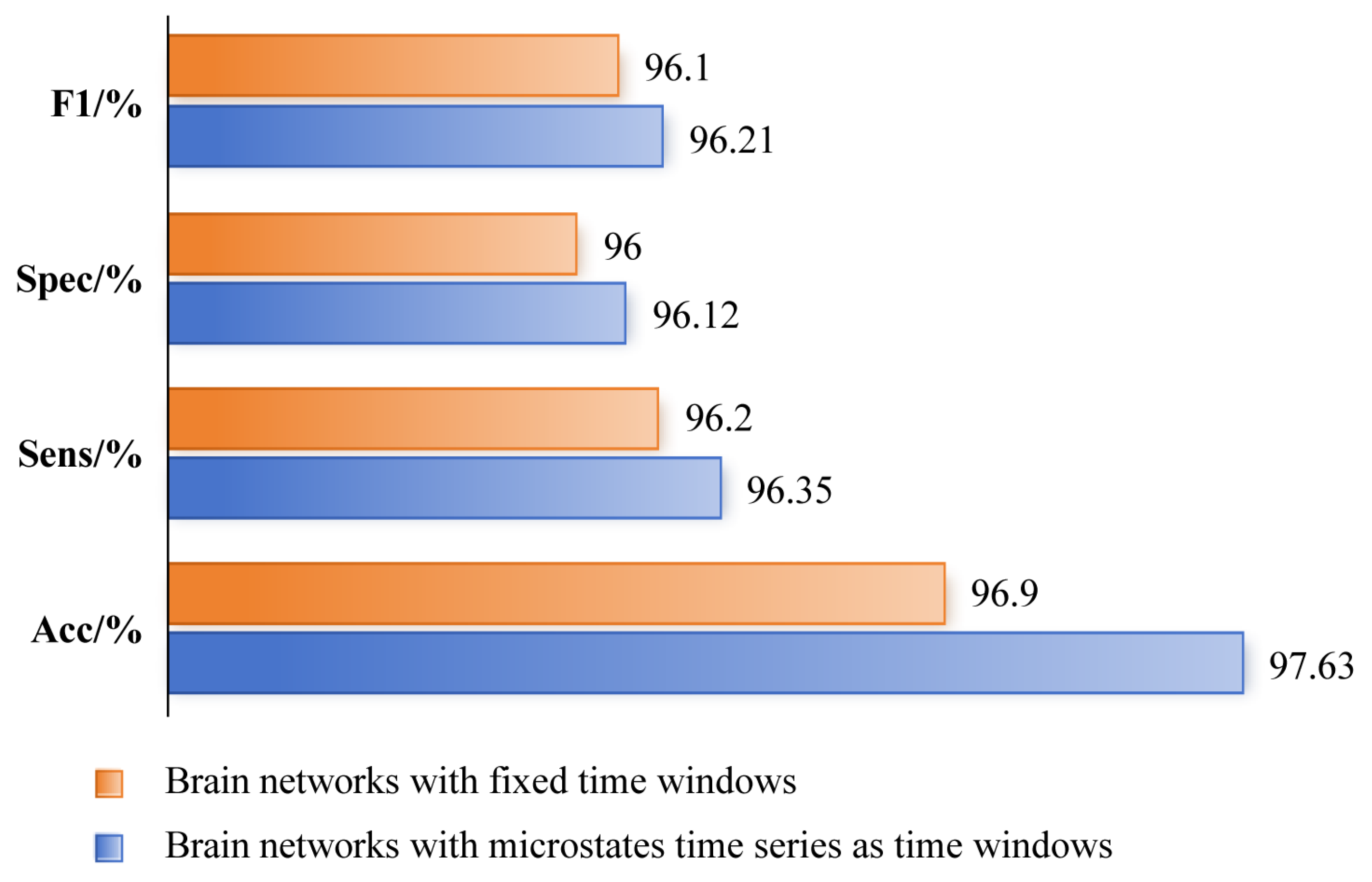

Compared with the brain network constructed according to a fixed time window, we believe that the brain network constructed based on microstate time sequences can more accurately reflect the cognitive state of the brain and, therefore, provide more feature information for depression identification. We compared the brain networks constructed using these two methods as features of the MSCAN model to determine their contribution to the effect of depression recognition. The results are shown in

Figure 9. The results showed that the Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, and F1-score of the MSCAN model for the diagnosis of depression reached 97.63%, 96.35%, 96.12%, and 96.21%, respectively, when the brain network constructed based on microstate time series was used as a feature. Compared to the brain network constructed based on fixed time windows as a feature, the depression diagnosis results were improved, indicating that the brain network constructed based on the microstate time series could characterize the brain functional connectivity features of depression more effectively.

3.4. Data Modal Ablation Experimental Results

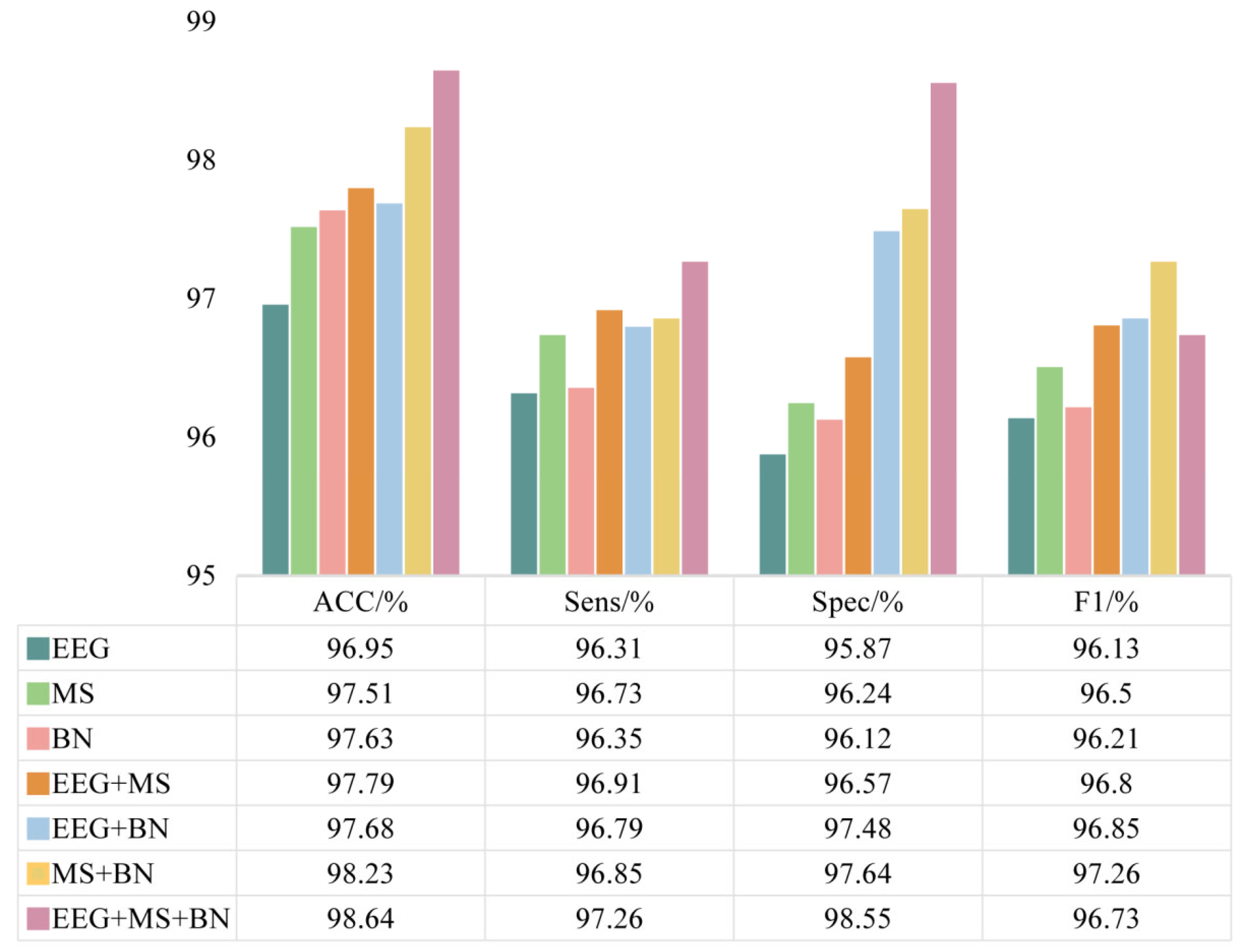

In this study, we combined EEG data, EEG microstates, and brain networks constructed based on microstate time series as multimodal data for the diagnosis of depression using the MSCAN model. To verify the contribution of these different modal data to depression diagnosis, we designed an ablation experiment with three sets of modal data. The results are shown in

Figure 10.

From the experimental results, it can be observed that the model performance is relatively low for a single modal input. The recognition accuracy based on EEG data was 96.95%, sensitivity was 96.31%, specificity was 95.87%, and F1 score was 96.13%. In contrast, microstate parameter-based and brain network features outperformed EEG data in some of the metrics, with microstate parameter-based diagnosis reaching 97.51% and 96.73% in terms of accuracy and sensitivity, respectively, and brain network feature-based diagnosis reaching 96.12% and 96.21% in terms of specificity and F1 score. The recognition performance improved when both sets of modal data were used simultaneously. The combination of EEG data with microstate features increased the accuracy to 98.23%, while the combination of EEG data with brain network features improved the specificity to 97.48%. In addition, the combination of microstate features and brain network features reached 97.26% in terms of F1 score. The overall recognition performance of the MSCAN model was optimized when the EEG data, microstate parameters, and brain network features were used simultaneously. The accuracy increased to 98.64%, the sensitivity reached 97.26%, the specificity increased to 98.55%, and the F1 score reached 96.73%. These results indicate that all three modal data, EEG data, microstate parameters, and brain network features contribute to different degrees to the recognition of depression in the MSCAN model, and that the brain activity features integrating multiple modal data improve the recognition of depression.

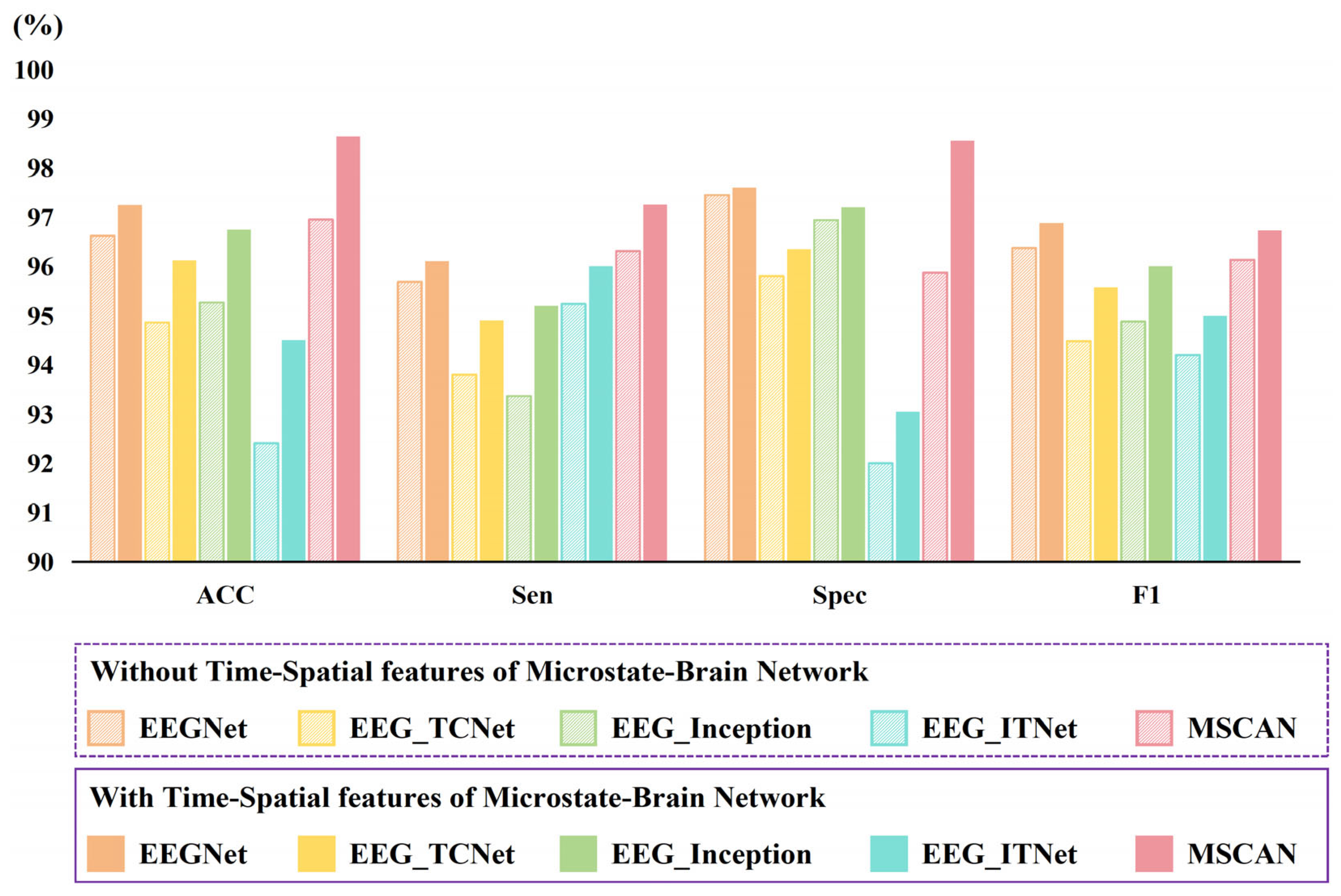

3.5. Comparison with Other MDD Diagnostic Models

In this study, we computed microstates based on EEG data and constructed brain networks corresponding to microstate time series. The microstates and brain networks changed the expression form of the EEG data to reflect the brain activity characteristics in terms of the spatial distribution of potentials and functional connectivity patterns, which effectively enhanced the effect of depression recognition. To verify the generalizability of the role of characterizing MDD brain activity with microstates and brain networks for depression recognition, we compared the depression recognition effect of using only EEG data and three modal data (EEG data, microstates, and brain networks) on other models, and the results are shown in

Table 6.

The results showed that several of the classical EEG signal recognition models used showed significant improvements in depression recognition with the addition of microstate and brain network data. Specifically, the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score of the EEGNet model were improved from 96.62%, 95.68%, 97.45%, and 96.37% to 97.25%, 96.1%, 97.6%, and 96.88%, respectively. The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score of the EEG_TCNet model improved from 94.86%, 93.8%, 95.8%, and 94.48% to 96.12%, 94.9%, 96.35%, and 95.58%, respectively. The Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, and F1-score of the EEG_Inception model improved from 95.27%, 93.37%, 96.94%, and 94.88% to 96.75%, 95.2%, 97.2%, and 96%, respectively. The Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, and F1-score of the EEG_ITNet model were improved from 92.41%, 95.24%, 92%, and 94.2% to 94.5%, 96%, 93.05%, and 95%, respectively. These results suggest that microstate parameters and brain network attributes can effectively provide depressive characteristics and enhance a model’s ability to recognize depression. The microstate parameters and brain network properties played a role not only in our proposed MSCAN model but also in other models (

Figure 11), suggesting the generalizability of the approach to characterize brain activity in depression using microstates and brain networks. In addition, the recognition results of our proposed MSCAN model for depression were higher than those of all the other compared models, which also proves that our proposed model can mine more feature information and has some advantages in depression recognition tasks. More importantly, MSCAN’s superior high sensitivity (true-positive rate) enables it to reliably identify genuine depression patients compared to traditional EEG-based methods, significantly reducing the risk of missed diagnoses—a feature of major clinical significance for early depression screening or large-scale initial screening tools. Simultaneously, while maintaining high specificity, the enhanced sensitivity indicates improved overall discriminative power, achieved without compromising the correct identification (specificity) of HC subjects.

3.6. Comparison with Advanced Methods

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, we compared it with several State-of-the-Art EEG-based depression recognition methods using the same dataset (MODMA). As shown in

Table 7, compared to 1DCNN [

56], 1TD+L-TCN [

57], AMG [

58], MGSN [

59], CNN+GRU [

60], SparNet [

61], and other models that rely solely on a single feature dimension (temporal, spatial, or frequency domain), our approach achieves efficient spatio-temporal feature fusion by constructing the MSCAN model. This model enhances EEG spatial feature extraction through the MSCA module and deeply mines long-term temporal features of EEG signals via the TTSA module. This achieves superior classification performance (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score of 98.64%, 97.26%, 98.55%, and 97.63%, respectively). Experimental results demonstrate that this approach fully leverages the multidimensional features of EEG signals to enhance classification capabilities. It provides novel insights for constructing depression recognition models and offers theoretical foundations and technical support for clinical detection.

4. Conclusions

This study utilized resting-state EEG signals to partition data from patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) into four microstates (A, B, C, D), constructing corresponding functional connectivity networks based on the temporal windows during which each microstate occurred. We computed graph-theoretic metrics (clustering coefficient, characteristic path length, global/local efficiency) for each network and combined these with spatio-temporal dynamic parameters of the microstates (duration, occurrence frequency, coverage, transition rate) to comprehensively characterize the spatio-temporal dynamics of brain activity in MDD patients. Building upon this, these features were input into the previously proposed MSCAN model and other EEG-classification models. Results demonstrated that incorporating microstate and network features significantly improved classification accuracy, reaching a maximum of 98.64%. Compared to healthy controls, MDD patients exhibited frequent microstate transitions, alongside functional connectivity networks characterized by reduced efficiency and increased energy expenditure. The pattern of poor coordination or imbalance in the functional networks of MDD patients may reflect weaknesses in cognitive control. This not only leads to general deficits in goal-directed behavior but also results in specific biases towards internal thought processes, at the expense of neglecting the external world.

Although our proposed diagnostic framework for major depressive disorder (MDD) based on resting-state EEG and functional connectivity networks holds potential as a clinical tool for auxiliary diagnosis, classification, or long-term monitoring due to EEG’s non-invasive nature, low cost, high temporal resolution, and ease of repeated measurement, its clinical translation still faces challenges. First, most current studies (including ours) suffer from limited sample sizes and single-source data, restricting the stability, reproducibility, and cross-site generalisability of results. Second, EEG signals exhibit relatively low spatial resolution and are susceptible to artefacts (e.g., environmental noise) and individual variability. These uncertainties may compromise the reliable extraction of microstates and network features, thereby reducing the stability and accuracy of real-time applications. Finally, the deep neural network employed in this study incorporates multiple convolutional layers and attention mechanisms, resulting in high computational demands and numerous parameters. This complexity compromises real-time performance. Therefore, future research should focus on reducing model complexity and computational/resource overhead. Concurrently, larger-scale, multi-center, multi-device, multimodal, and standardized studies are needed to validate the stability, reliability, and applicability of these approaches.