Nanoparticles Composed of β-Cyclodextrin and Sodium p-Styrenesulfonate for the Reversible Symmetric Adsorption of Rhodamine B

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of M-β-CD

2.3. Preparation of M-β-SCDP

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

2.5. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

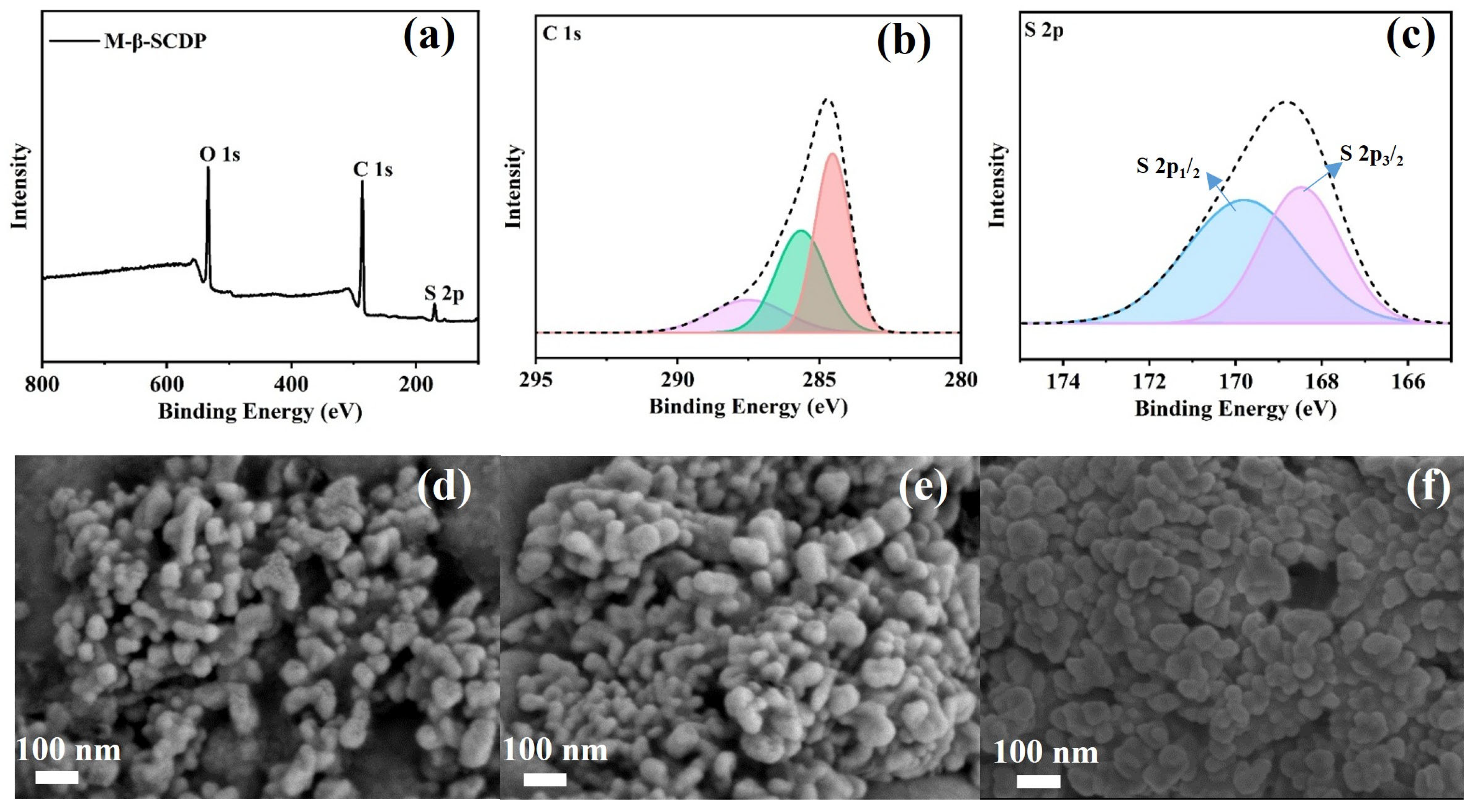

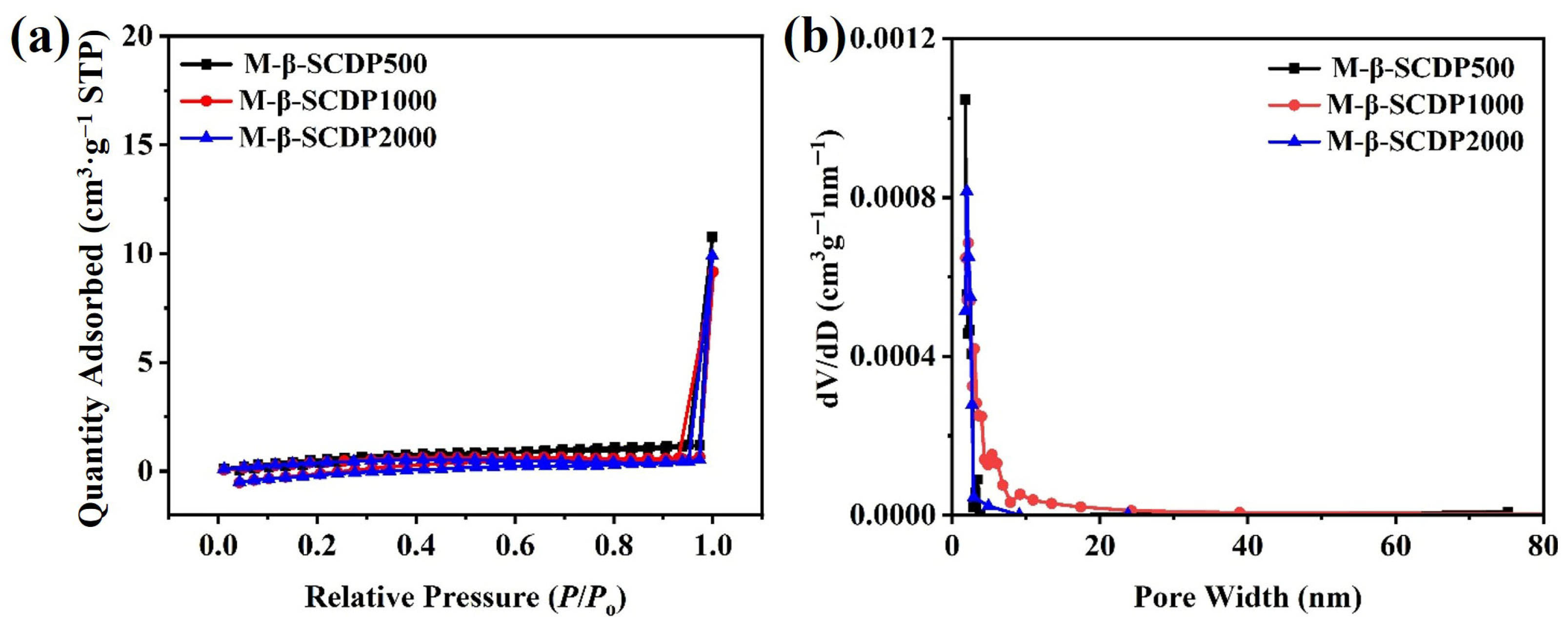

3.1. Structural Characterization

3.2. Evaluation of Adsorption Performance of M-β-SCDP for RhB

3.2.1. Solution pH

3.2.2. Adsorbent Dosage

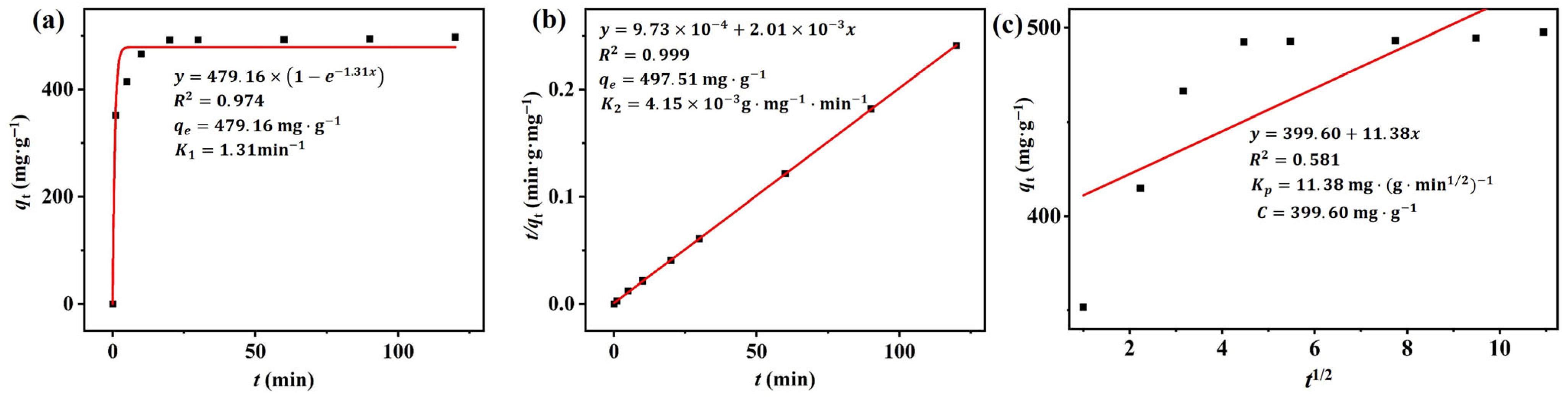

3.2.3. Kinetic Studies

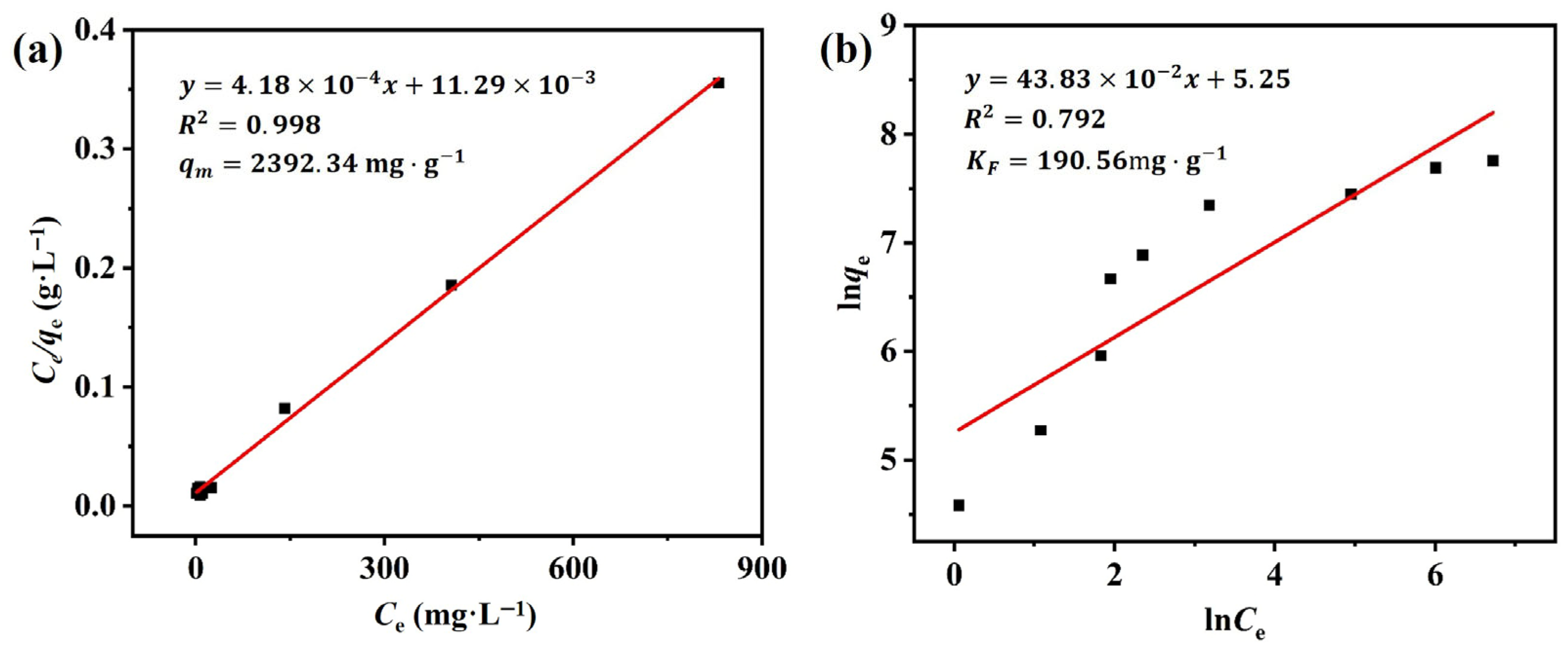

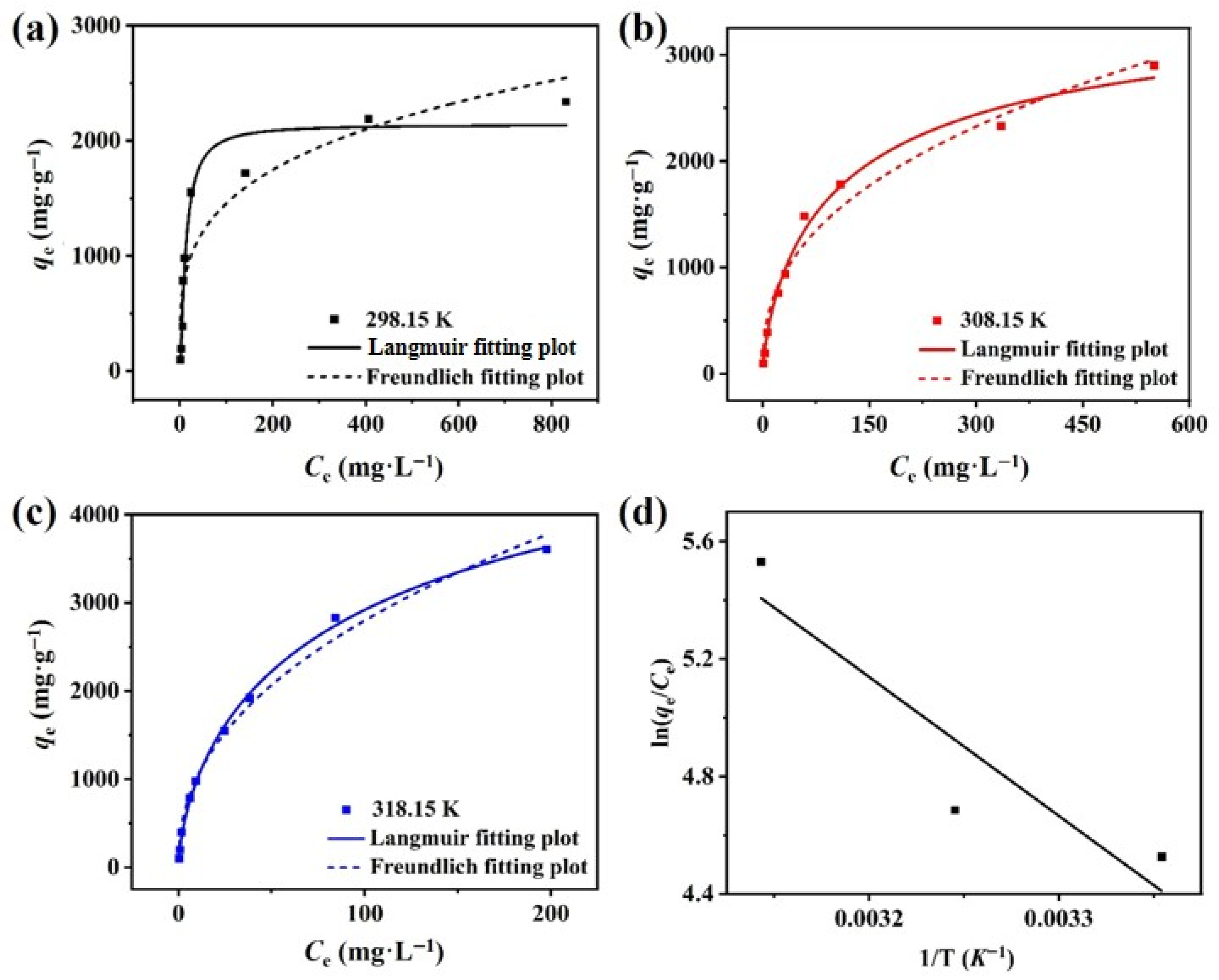

3.2.4. Adsorption Isotherm

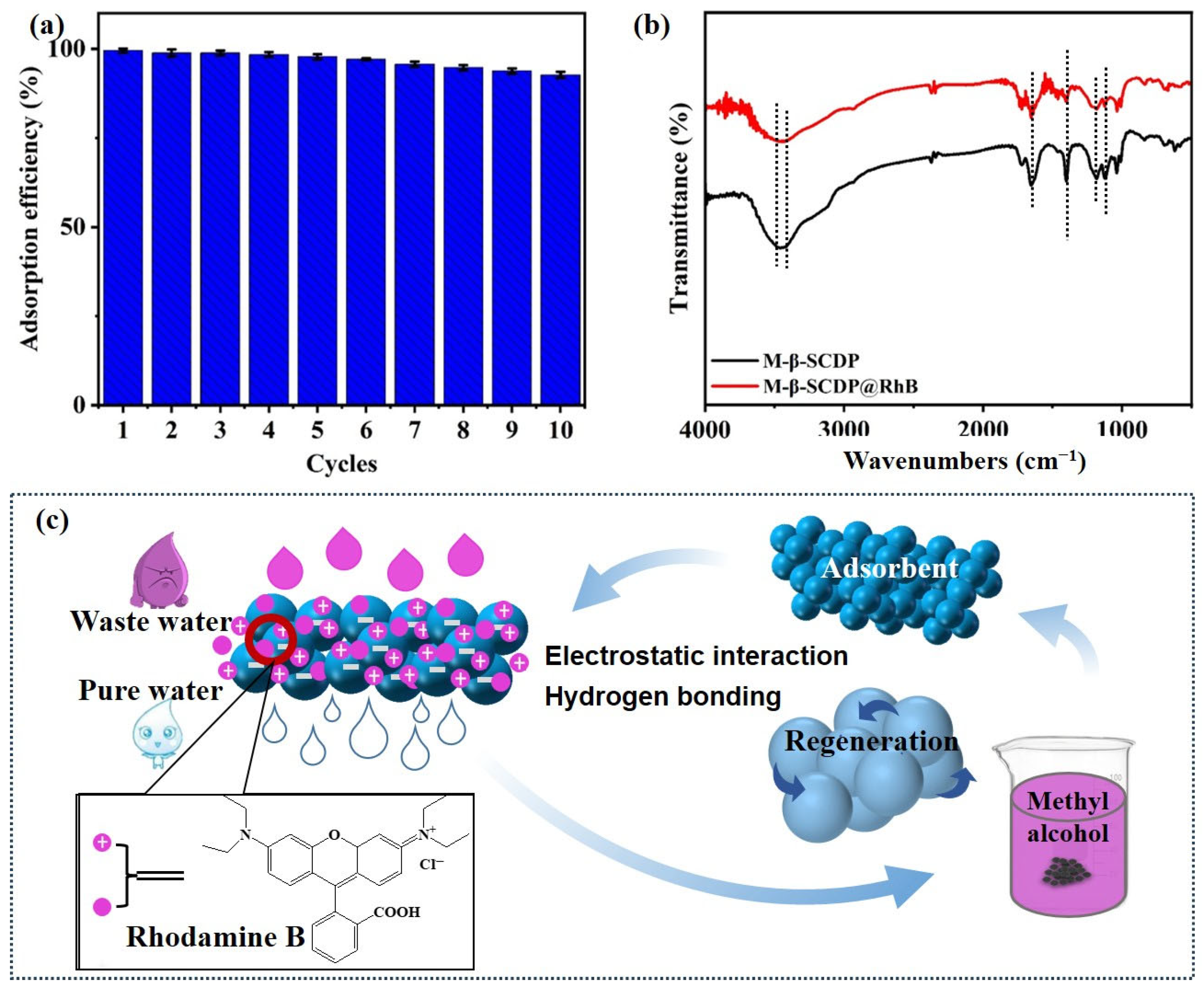

3.2.5. Thermodynamic Studies and Recyclability

3.2.6. Adsorption Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amalina, F.; Abd Razak, A.S.; Krishnan, S.; Zularisam, A.W.; Nasrullah, M. A review of eco-sustainable techniques for the removal of Rhodamine B dye utilizing biomass residue adsorbents. Phys. Chem. Earth 2022, 128, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Ren, X.; Yan, B.; Ding, G. Preparation of Sodium Phthalocyanine Cobalt Sulfonate/Porous γ-Alumina Composites for Photocatalytic Reduction of Rhodamine B. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2025, 39, e70078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Xiao, S. PDA-assisted immobilization of nZVI on cotton fabric for the removal of rhodamine B and chromium (VI) ion. Cellulose 2024, 32, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumphon, J.; Ahmed, R.; Imboon, T.; Giri, J.; Chattham, N.; Mohammad, F.; Kityakarn, S.; Mangala Gowri, V.; Thongmee, S. Boosting photocatalytic activity in rhodamine B degradation using Cu-doped ZnO nanoflakes. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 9337–9350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendri, Y.N.; Rati, Y.; Auni, A.K.E.; Marlina, R.; Munir, M.M.; Patah, A.; Darma, Y. Controlled pyrolysis of Zn-based metal organic framework-derived ZnO/C for Rhodamine-B degradation. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennah, A.; Khan, M.A.; Zbair, M.; Ait Ahsaine, H. NiO/AC active electrode for the electrosorption of rhodamine B: Structural characterizations and kinetic study. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, H.B.; Chenari Bouket, A.; Pourhassan, Z.; Alenezi, F.N.; Silini, A.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Oszako, T.; Luptakova, L.; Golińska, P.; Belbahri, L. Diversity of synthetic dyes from textile industries, discharge impacts and treatment methods. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaquén, T.B.; Carraro, P.M.; Eimer, G.A.; Urzúa-Ahumada, J.; Poon, P.S.; Matos, J. Rice husks as a biogenic template for the synthesis of Fe2O3/MCM-41 nanomaterials for polluted water remediation. Molecules 2025, 30, 12484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thottathil, S.; Puttaiahgowda, Y.M.; Selvaraj, R.; Vinayagam, R. Sustainable quercetin-based porous organic polymer for efficient rhodamine B dye removal and phytotoxicity assessment. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Tang, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, D. Chloride anion adsorption from wastewater using a chitosan/β-cyclodextrin-based composite. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2022, 45, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Li, Z.; Shi, Q.; Zhao, L.; Ma, J.; Li, R.; Liu, X.E. Industrial scale utilization of bamboo-based columnar activated carbon for efficient treatment of Rhodamine B: Process optimization and performance analysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G. Effective adsorption of rhodamine B by N/O Co-doped AC@CNTs composites prepared through catalytic coal pyrolysis. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 46, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Li, H.; Jia, X.; Ma, P.-C. Facile preparation of ZIF-8 functionalized basalt fiber felt and its high adsorption capacity for iodine. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 41, 103318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, B.; Januszewicz, K. Advancing sustainable wastewater treatment with biomass-based highly porous activated carbon: Insights into sorption mechanisms and efficiency. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, B.; Xu, J.; Pan, K.; Hou, H.; Hu, J.; Yang, J. Cross-linked chitosan/β-cyclodextrin composite for selective removal of methyl orange: Adsorption performance and mechanism. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 182, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Peindy, H.; Gimbert, F.; Robert, C. Removal of C.I. Basic Green 4 (Malachite Green) from aqueous solutions by adsorption using cyclodextrin-based adsorbent: Kinetic and equilibrium studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 53, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Loh, X.J. Cyclodextrin-based supramolecular architectures: Syntheses, structures, and applications for drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1000–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgın, U.; Alomari, İ.; Soyer, N.; Salgın, S. Adsorption of bisphenol A onto β-Cyclodextrin-based nanosponges and innovative supercritical green regeneration of the sustainable adsorbent. Polymers 2025, 17, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amran, F.; Zaini, M.A.A. Beta-cyclodextrin adsorbents to remove water pollutants—a commentary. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2022, 16, 1407–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y. Novel cyclodextrin-based adsorbents for removing pollutants from wastewater: A critical review. Chemosphere 2019, 241, 125043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Dexian, C.; Jie, M. Synthesis of cyclodextrin-based adsorbents and its application for organic pollutant removal from water. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 1976–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Korin Manor, N.; Radian, A. Iron–montmorillonite–cyclodextrin composites as recyclable sorbent catalysts for the adsorption and surface oxidation of organic pollutants. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 52873–52887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozelcaglayan, E.D.; Parker, W.J. β-cyclodextrin functionalized adsorbents for removal of organic micropollutants from water. Chemosphere 2023, 320, 137964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajandran, P.; Masngut, N.; Abdul Manas, N.H.; Wan Azelee, N.I.; Mohd Fuzi, S.F.Z.; Bunyamin, M.A.H. Column adsorption studies on carbazole removal using β-cyclodextrin-functionalized activated rice hull biochar. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 69, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohith, M.; Rohith, P.; Daya, V.P.; Girija, P. Facilitating the excision of toxic dyes from wastewater via a green citric acid crosslinked β-CYCAL sorbent and its comparative study. J. Polym. Res. 2024, 31, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, B.; Chai, S.-H.; Liu, H.; Dai, S. Hyper-crosslinked β-cyclodextrin porous polymer: An adsorption-facilitated molecular catalyst support for transformation of water-soluble aromatic molecules. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Sun, Y.; Yang, R.; Qu, L.; Li, Z. Poly(sodium styrene sulfonate) functionalized graphene as a highly efficient adsorbent for cationic dye removal with a green regeneration strategy. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 152, 109973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, P.; Patra, A.S.; Mukherjee, A.K.; Pal, S. Development of a highly efficient selective flocculant based on functionalized β-cyclodextrin toward beneficiation of low-quality iron ore. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 2169–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Lv, X.; Xu, W.; Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Jia, H.; Yi, S.; Fang, D. Hectorite-modified sodium alginate/γ-cyclodextrin microspheres with tunable interlayers for dye removal. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 13743–13754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Yao, T.; Qian, C. Synthesis and Application for Pb2+ Removal of a Novel Magnetic Biochar Embedded with FexOy Nanoparticles. Symmetry 2025, 17, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Liu, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lincoln, S.F.; Guo, X.; Wang, J. Cyclodextrin Hydrogels: Rapid Removal of Aromatic Micropollutants and Adsorption Mechanisms. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2020, 65, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, W.; Yun, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Fu, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, G. Preparation and characterization of a modified-β-cyclodextrin/β-carotene inclusion complex and its application in pickering emulsions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 12875–12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-H.; Fung, M.-P.; Chen, Y.-Q.; Chiu, Y.-C. Development of mucoadhesive methacrylic anhydride-modified hydroxypropyl methylcellulose hydrogels for topical ocular drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 93, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Zhang, X.; Shao, S.; Xiang, T.; Zhou, S. Covalently crosslinked sodium alginate/poly(sodium p-styrenesulfonate) cryogels for selective removal of methylene blue. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 301, 120356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Shi, X.; Wang, A. Enhanced swelling and responsive properties of an alginate-based superabsorbent hydrogel by sodium p-styrenesulfonate and attapulgite nanorods. Polym. Bull. 2013, 70, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, A.A.; Abd Elmageed, M.H.; Malash, G.F.; Tamer, T.M.; Omer, A.M.; Mohy-Eldin, M.S.; Khalifa, R.E. Development of novel cellulose acetate-g-poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) proton conducting polyelectrolyte polymer. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, C. Magnetic nickel cobalt sulfide/sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate with excellent ciprofloxacin adsorption capacity and wide pH adaptability. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 127208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, S.; Yu, X.; Wang, X.; Ruan, D.; Qiao, Z.; Wang, Y. Sodium ion diffusion behavior in multiple open/closed pore ratios of novel β-cyclodextrin-derived hard carbon anode materials. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Colletti, C.G.; Lazzara, G.; Guernelli, S.; Noto, R.; Riela, S. Synthesis and characterization of halloysite–cyclodextrin nanosponges for enhanced dyes adsorption. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3346–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, V.; Gubitosa, J.; Signorile, R.; Fini, P.; Cecone, C.; Matencio, A.; Trotta, F.; Cosma, P. Cyclodextrin nanosponges as adsorbent material to remove hazardous pollutants from water: The case of ciprofloxacin. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 411, 128514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiba, U.; Siddique, A.; Li Lee, J.; Joo, C.; Ang, C.; Afifi, M. Adsorption study of methyl orange by chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol/zeolite electrospun composite nanofibrous membrane. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 191, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagiewka, J.; Pajdak, A.; Zawierucha, I. Adsorption performance and mechanism of a novel composite based on β-cyclodextrin polymer and chitosan: Selective and rapid removal of acid orange 7. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 353, 123297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, J.; Gao, J.; Shen, J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, C. Preparation of magnetic graphene/β-cyclodextrin polymer composites and their application for removal of organic pollutants from wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Xu, G.; Jiang, L.; Hu, X.; Xu, J.; Xie, X.; Li, A. Amphiphilic hyper-crosslinked porous cyclodextrin polymer with high specific surface area for rapid removal of organic micropollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 123015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayranli, B. Adsorption efficiency of groundnut husk biochar in reduction of rhodamine B, recycle, and reutilization. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 25501–25513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wei, L. One-step synthesis of mesoporous manganese silicate for efficient adsorption of methylene blue, rhodamine B, and brilliant green. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G. Ultrahigh-capacity adsorption of rhodamine B by N, S co-doped carbon nanotube composites derived from coal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 134045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptaszkowska-Koniarz, M.; Goscianska, J.; Pietrzak, R. Removal of rhodamine B from water by modified carbon xerogels. Colloids Surf. A 2018, 543, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayeeye, F.; Sattar, M.; Chinpa, W.; Sirichote, O. Kinetics and thermodynamics of rhodamine B adsorption by gelatin/activated carbon composite beads. Colloids Surf. A 2017, 513, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozhiarasi, V.; Natarajan, T.S. Bael fruit shell–derived activated carbon adsorbent: Effect of surface charge of activated carbon and type of pollutants for improved adsorption capacity. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 14, 8761–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Kaczmarek, A.M.; Van Hecke, K. Ratiometric Thermometers based on rhodamine B and fluorescein dye-incorporated (nano) cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 14367–14379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukali, R.; Radovic, I.; Stojanovic, D.; Sevic, D.; Radojevic, V.; Jocic, D.; Aleksic, R. Electrospinning of laser dye rhodamine B-doped poly(methyl methacrylate) nanofibers. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2014, 79, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, Y.; Ishiwata, T.; Sugikawa, K.; Kokado, K.; Sada, K. Nano- and microsized cubic gel particles from cyclodextrin metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10566–10569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Adsorbent | Pollutant | Pseudo-First Order | Pseudo-Second Order | Particle Diffusion Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q1e (mg·g−1) | K1 (min−1) | R2 | q2e (mg·g−1) | K2 (g·mg−1·min−1) | R2 | Kp | C | R2 | ||

| M-β-SCDP500 | RhB | 479.16 | 1.31 | 0.974 | 497.51 | 0.999 | 11.38 | 399.60 | 0.581 | |

| Adsorbents | Pollutants | qm (mg·g−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin-based novel porous organic polymer (QPOP) | RhB | 499.52 | [9] |

| Bamboo-based columnar activated carbons (BAC-10) | RhB | 300.3 | [11] |

| Groundnut husk biochar (GHB) | RhB | 182.24 | [45] |

| Mesoporous manganese silicate (MH) | RhB | 420.63 | [46] |

| Carbon nanotube composites (SCTNs/AC) | RhB | 3242.04 | [47] |

| M-β-SCDP500 | RhB | 2392.34 | This work |

| Adsorbents | Pollutant | ΔH° (kJ·mol−1) | ΔS° (J·mol−1·K−1) | ΔG° (kJ·mol−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298.15 K | 308.15 K | 313.15 K | ||||

| M-β-SCDP500 | RhB | 12.17 | 78.46 | −11.21 | −24.18 | −24.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Qian, J.; Zhang, P.; Yang, X. Nanoparticles Composed of β-Cyclodextrin and Sodium p-Styrenesulfonate for the Reversible Symmetric Adsorption of Rhodamine B. Symmetry 2026, 18, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010055

Liu Y, Zhou Q, Zuo Y, Qian J, Zhang P, Yang X. Nanoparticles Composed of β-Cyclodextrin and Sodium p-Styrenesulfonate for the Reversible Symmetric Adsorption of Rhodamine B. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yinli, Qingfeng Zhou, Yiyang Zuo, Jintao Qian, Pan Zhang, and Xiaogang Yang. 2026. "Nanoparticles Composed of β-Cyclodextrin and Sodium p-Styrenesulfonate for the Reversible Symmetric Adsorption of Rhodamine B" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010055

APA StyleLiu, Y., Zhou, Q., Zuo, Y., Qian, J., Zhang, P., & Yang, X. (2026). Nanoparticles Composed of β-Cyclodextrin and Sodium p-Styrenesulfonate for the Reversible Symmetric Adsorption of Rhodamine B. Symmetry, 18(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010055