Research on Buckling Failure Test and Prevention Strategy of Boom Structure of Elevating Jet Fire Truck

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Scheme and Purpose

- 1.

- Accurately simulating the actual multi-axial combined stress state

- 2.

- Separating the evolution processes of buckling initiation (weakened version) and final failure (reinforced version)

- 3.

- Establishing the mapping relationship between load percentage control and real failure modes

- (1)

- Structural model accuracy verification (through systematic comparison between test results in the linear phase and simulation results)

- (2)

- Research on the evolution mechanism of boom failure (through high-density data to track the initiation and propagation path of local buckling)

2.2. Test Equipment

2.3. Simulation Method

2.4. Material Properties

2.5. Constraints and Loads

3. Results

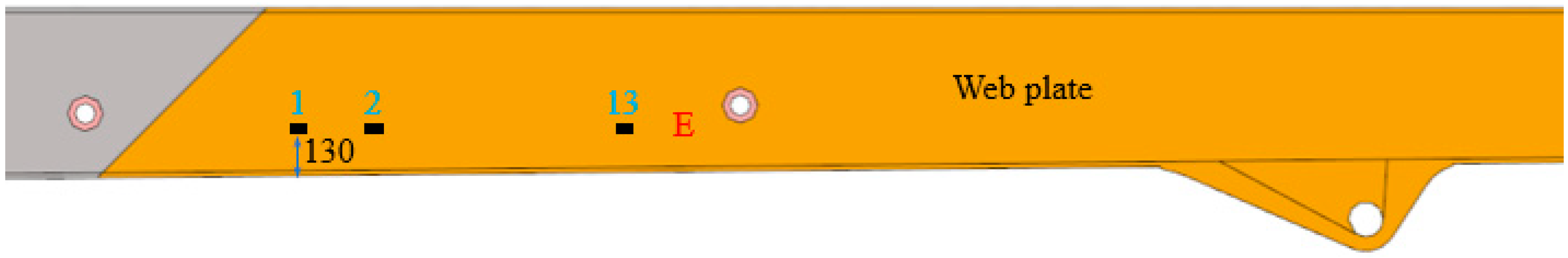

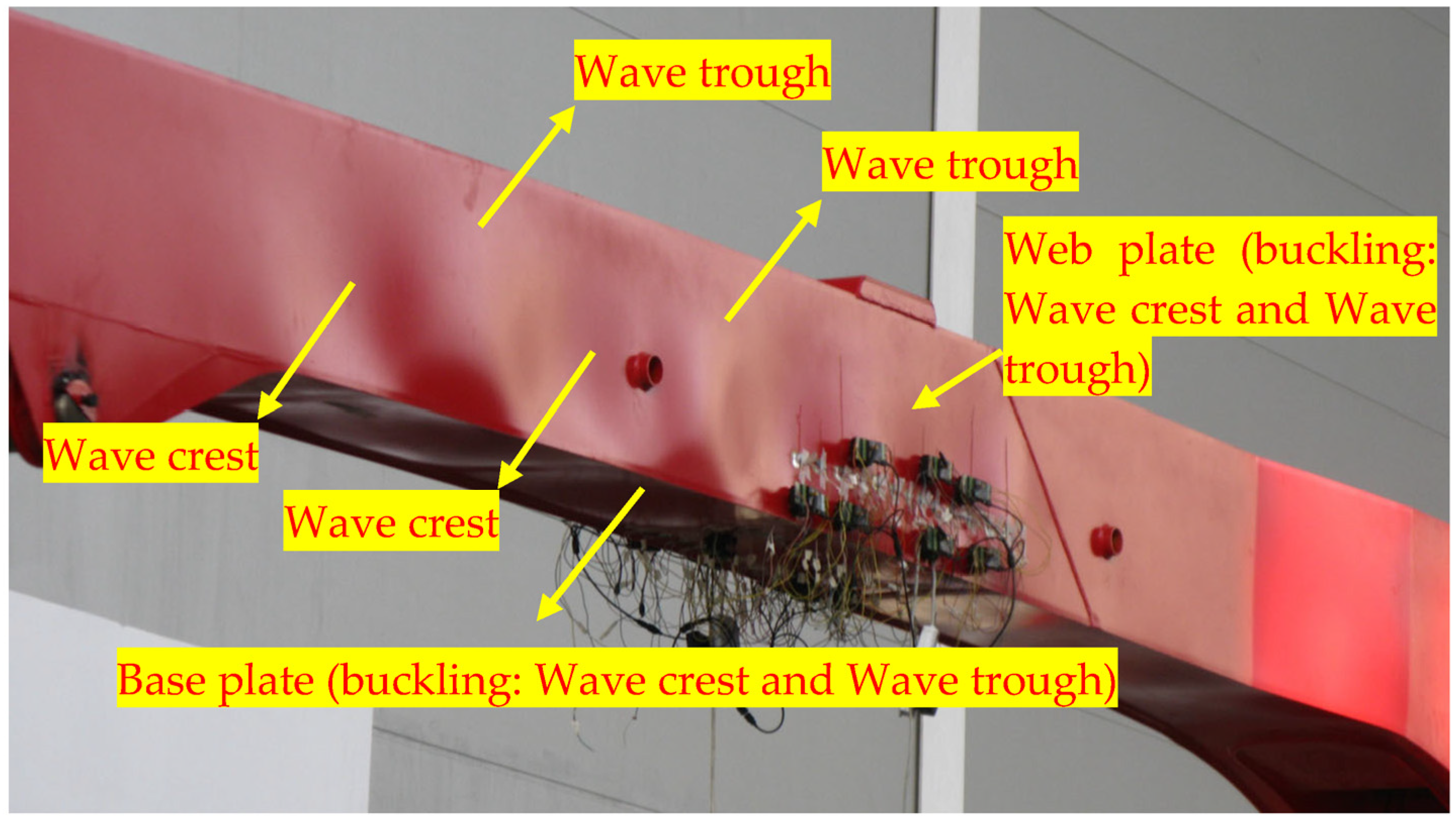

3.1. Boom Buckling Test Results

3.2. Boom Buckling Simulation Results

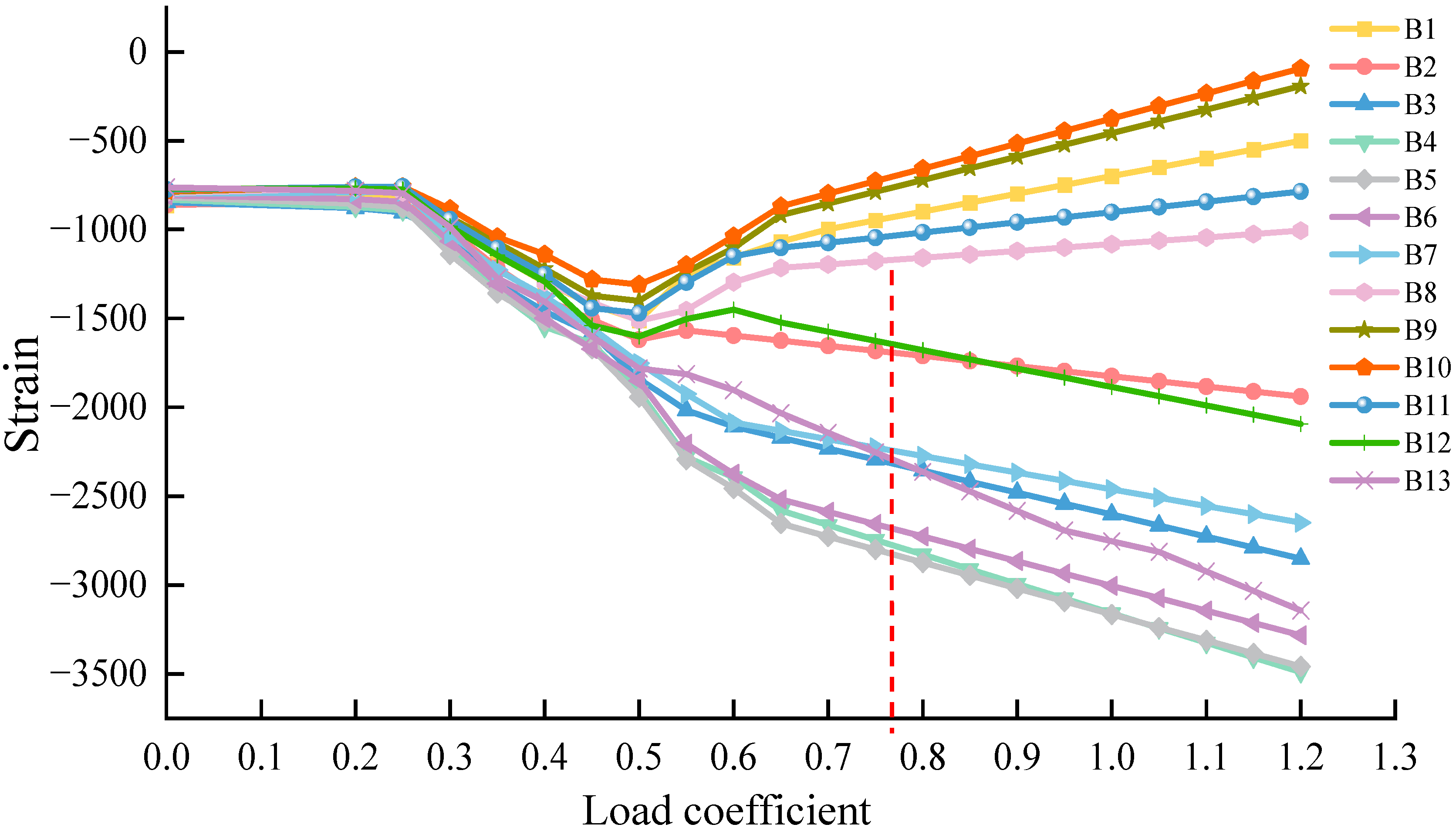

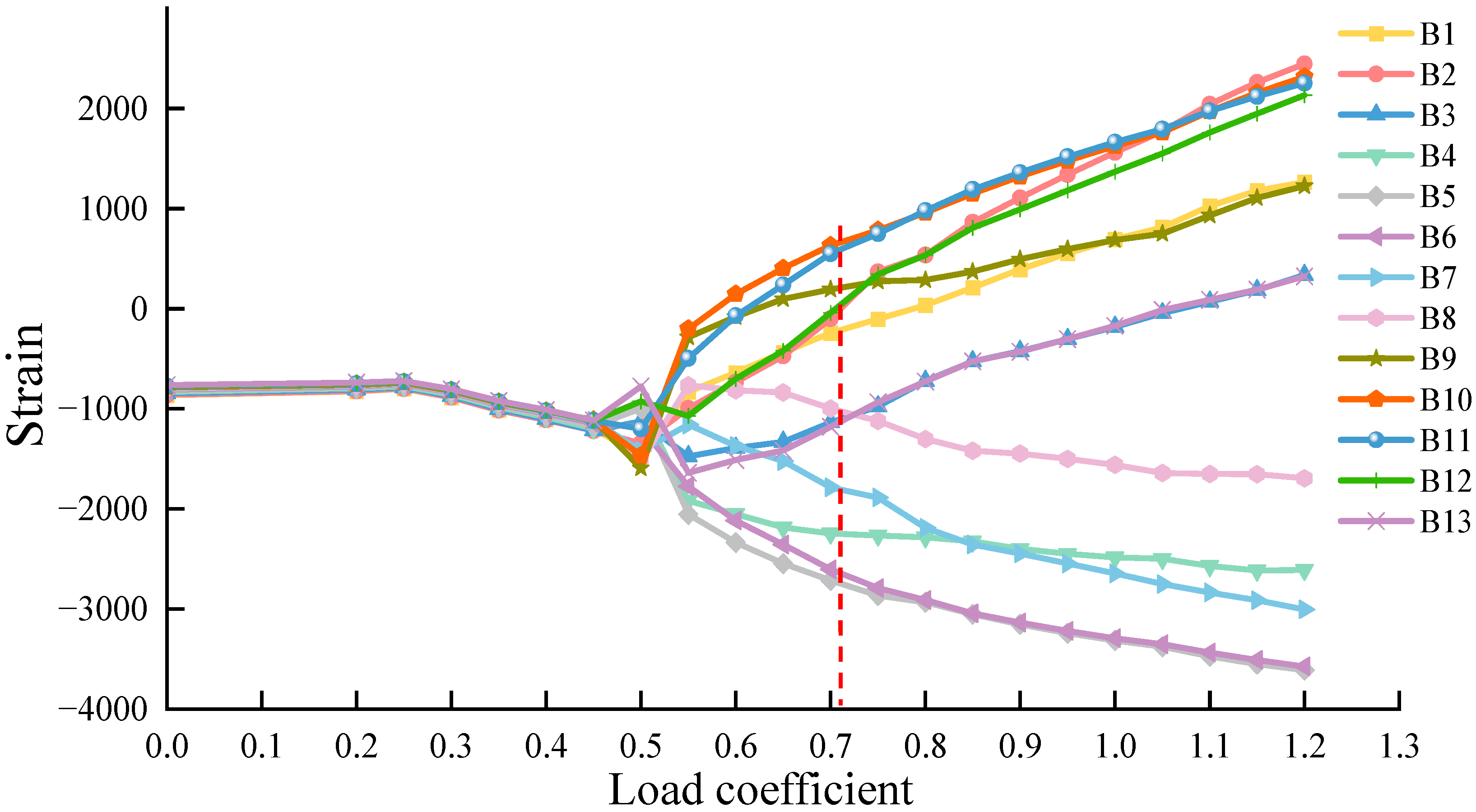

- (1)

- Initial stable stage (load coefficient: 0–0.45): Parameter convergence under low loadIn this stage, all strains are maintained in the range of −1468 με to −721 με, with gentle fluctuations and no significant differentiation. When the load coefficient increases from 0 to 0.45, the maximum absolute value of strain increases by 46.2–70.0%, and the difference between strains is always less than 100 με. Since the load does not exceed the “initial load-bearing threshold”, the structure only undergoes elastic deformation, and the responses of each monitoring point are convergent.

- (2)

- Critical mutation stage (load coefficient: 0.5–0.55): Extreme parameter differentiation after load exceeds the threshold. In this stage, parameters show extreme differentiation after the load exceeds the “critical buckling threshold”. At a load coefficient of 0.5, the values of the negative extreme group (B4–B8) drop sharply (B9 reaches −1593.7 με with a decrease of 43.5%), while the decrease range of the transition group (B1–B3, B10–B13) is less than 30%; at a load coefficient of 0.55, B5 reaches −2055.1 με (a decrease of 106.0% compared with that at 0.5), and the maximum strain difference expands to 1770.1 με. This is due to local buckling of the structure, which leads to a prominent difference in the mechanical states of different monitoring points.

- (3)

- Unidirectional extension stage (load coefficient: 0.6–1.2): Bidirectional stable extension of parameters under high load. In this stage, the parameters show “bidirectional monotonic extension”. The positive extension group (B1–B3, B9–B13) changes from negative compressive strain to positive tensile strain; for example, B1 increases from −638.6 με to 1265.1 με, with an increase of 100–200 με for every 0.05 increase in load coefficient. The negative extension group (B4–B8) maintains compressive strain and the absolute value increases; for example, B5 decreases from −2335.4 με to −3612.7 με, with a constant difference of 1000–1200 με. This is because the structure completes buckling reconstruction and enters a “plastic stable load-bearing state”.

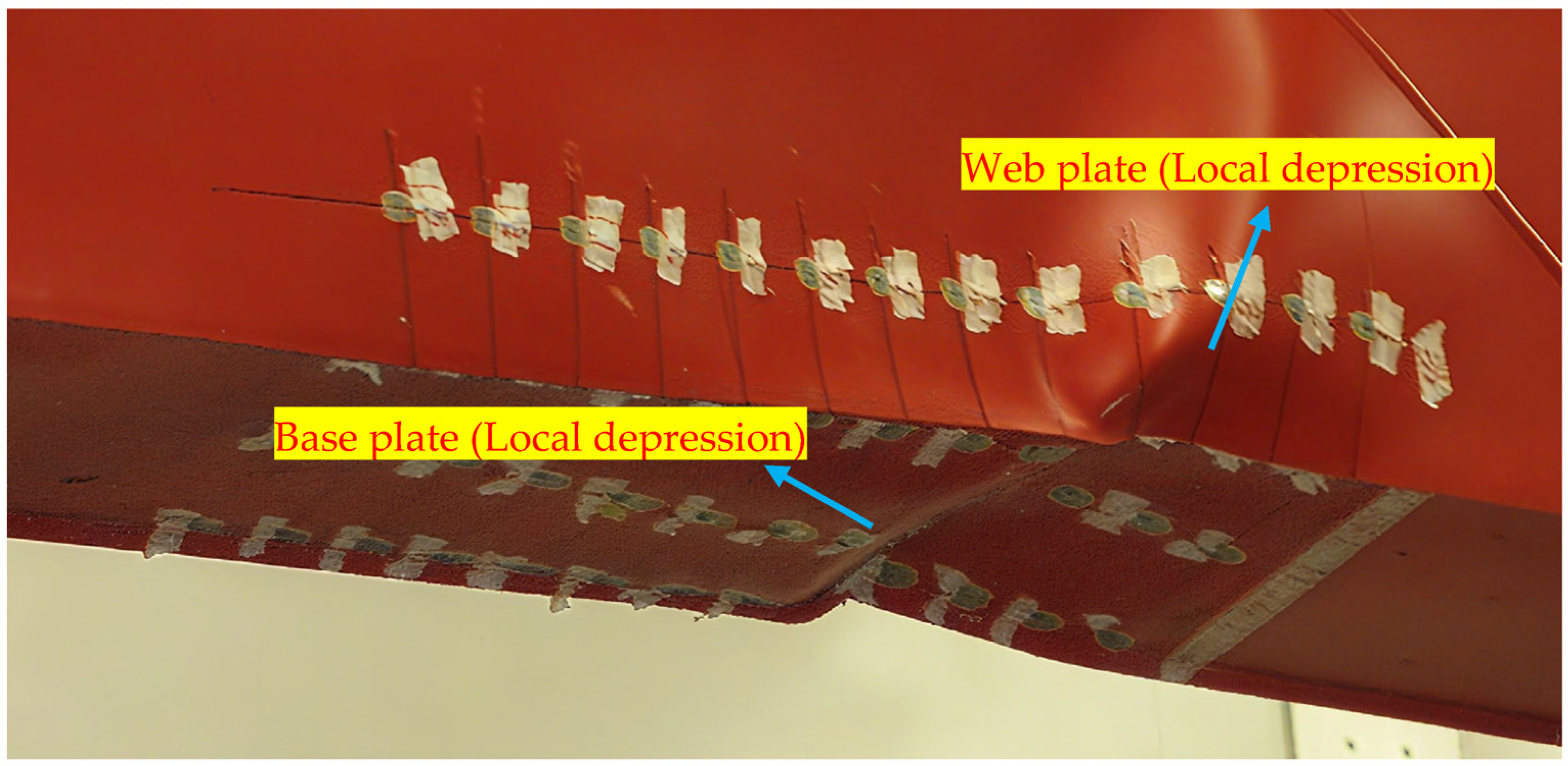

3.3. Boom Buckling Failure Results

3.4. Deviation Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion on Boom Buckling Test Results

4.2. Discussion on Boom Buckling Calculation Results

- (1)

- Initial Stage (Load Factor ≤ 0.25): The strain-load relationship at all measurement points exhibits a strict linear proportionality, with the strain curve cluster forming parallel straight lines. The structure remains in a linear elastic equilibrium state, with internal force distribution conforming to classical beam theory. Elastic strain energy accumulates steadily without nonlinear disturbances, and the in-plane load-bearing capacity of the base plate is unaffected. This stage represents the “stable load-bearing period” prior to buckling.

- (2)

- When the load factor is in the range of 0.25–0.45, the strain increment maintains linear growth, but the curve slope exhibits a systematic negative deviation, revealing that accumulated compressive stress gradually weakens section stiffness. This phenomenon arises from the coupled interaction between microscopic lattice distortion hardening effects and the initial emergence of macroscopic geometric nonlinearity. At this stage, the structure exists in a metastable equilibrium state, with no significant buckling occurring yet, but the weakening of stiffness already harbors instability, constituting the “pre-buckling transition stage.”

- (3)

- Upon reaching a load factor of 0.45, the strain field undergoes an irreversible transformation, marking the onset of buckling feature transition. The eight upper measurement points exhibit strain sign reversal, abruptly transitioning from compressive to tensile strains with a maximum jump of 300% relative to the initial value. This originates from mid-surface tension deformation induced by buckling half-wave elevation, transforming the originally uniaxially compressed areas into biaxially tensioned states. Simultaneously, the five lower measurement points display a 200% increase in compressive strain gradient, forming triaxial stress confinement singularity zones and triggering localized plastic flow bands. The neutral strain layer shifts downward along the plate thickness, with its displacement magnitude serving as a quantifiable indicator of buckling mode deformation amplitude.

4.3. Discussion on the Comparison Results of Boom Buckling Test and Calculation

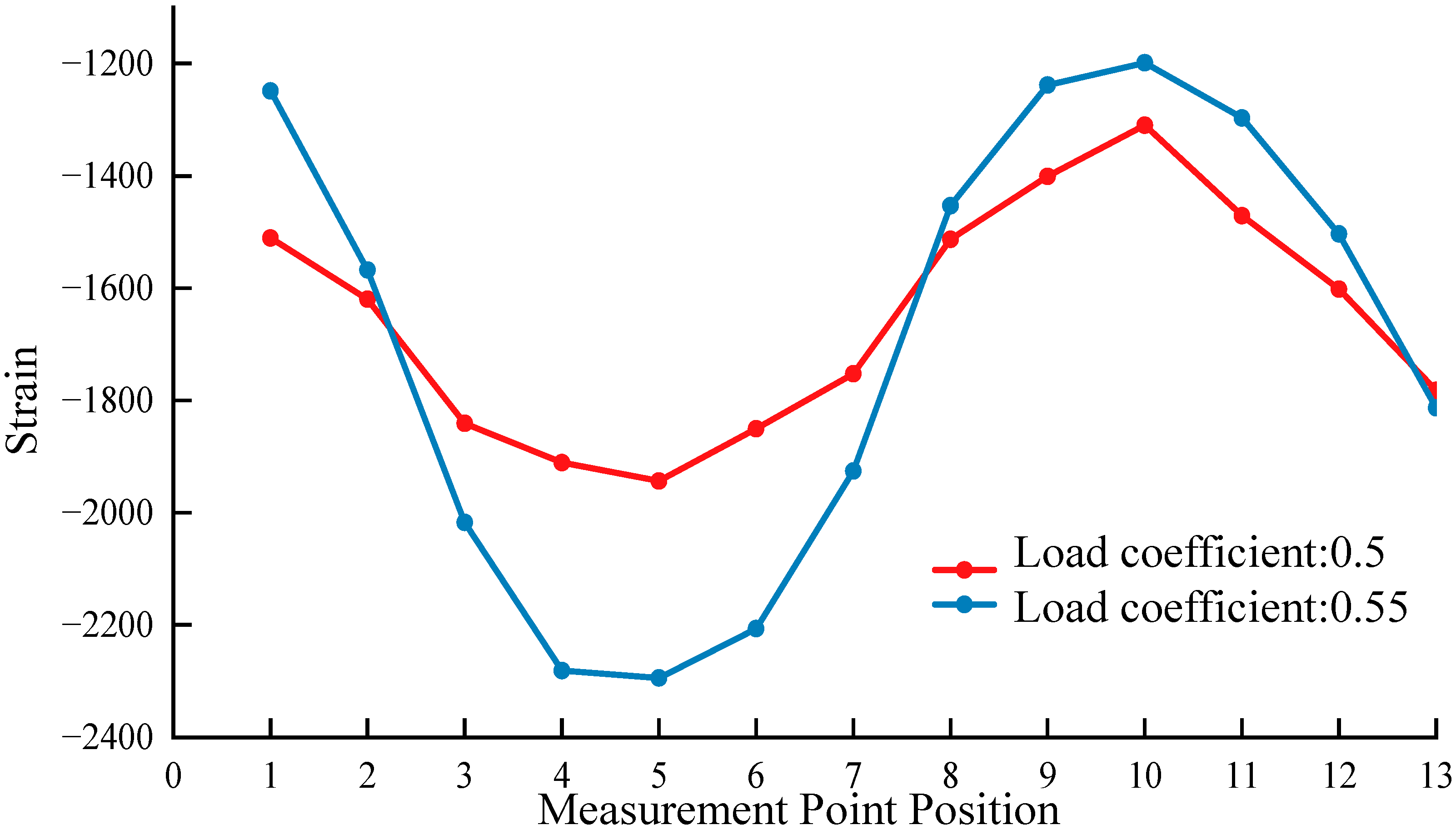

- (1)

- When the load factor increases to 0.5, the strain curves exhibit a typical sinusoidal buckling waveform with a peak-to-peak value of 650 με. The spatial phase characteristics of this waveform provide three critical instability diagnostic criteria: First, the zero-crossing points of the waveform precisely correspond to the projected position of the base plate’s theoretical neutral surface, confirming the geometric completeness of the buckling mode through the symmetry of the cosine function, indicating the formation of a regular half-wave buckling morphology. Second, upon reaching a load factor of 0.55, the peak-to-peak value of the waveform nonlinearly increases to 1100 με—a 69.2% rise—attributable to the nonlinear coupling between membrane compression effects in the wave trough region and bending curvature, reflecting the rapid development phase of buckling. Third, the peak spacing of the waveform stabilizes at 675 mm, fully consistent with finite element predictions, confirming that the buckling mode has entered an energy-stable state and validating its reliability.

- (2)

- Mechanistically, experimental data reveals two critical instability evolution mechanisms: At the material level, the 650 με waveform amplitude triggers microscopic plastic flow in steel, forming plastic strain concentration zones (local strains exceeding 1100 με), marking the transition from elastic to plastic behavior. Morphologically, the displacement of extrema in the cosine function’s derivative reveals the migration of buckling half-wave inflection points toward the boundaries.

- (3)

- This phenomenon establishes a predictive framework from experimental strain to engineering failure: The relative deflection of the base plate corresponding to the 650 με cosine amplitude at initial buckling approaches the elastic limit for thin plate deformation. Once the amplitude exceeds 1000 με, accumulated plasticity will accelerate structural stiffness degradation. The mutual validation of experimental and theoretical findings demonstrates that the sinusoidal waveform at a 0.5 load factor serves as morphological evidence of buckling initiation. Its phase symmetry, amplitude discontinuity, and constant wavelength constitute a triple verification system for instability criteria, forming a cross-scale diagnostic paradigm of “morphological identification → amplitude alerting → wavelength calibration.” This reveals the complete mechanism of buckling from initiation, development to approaching failure.

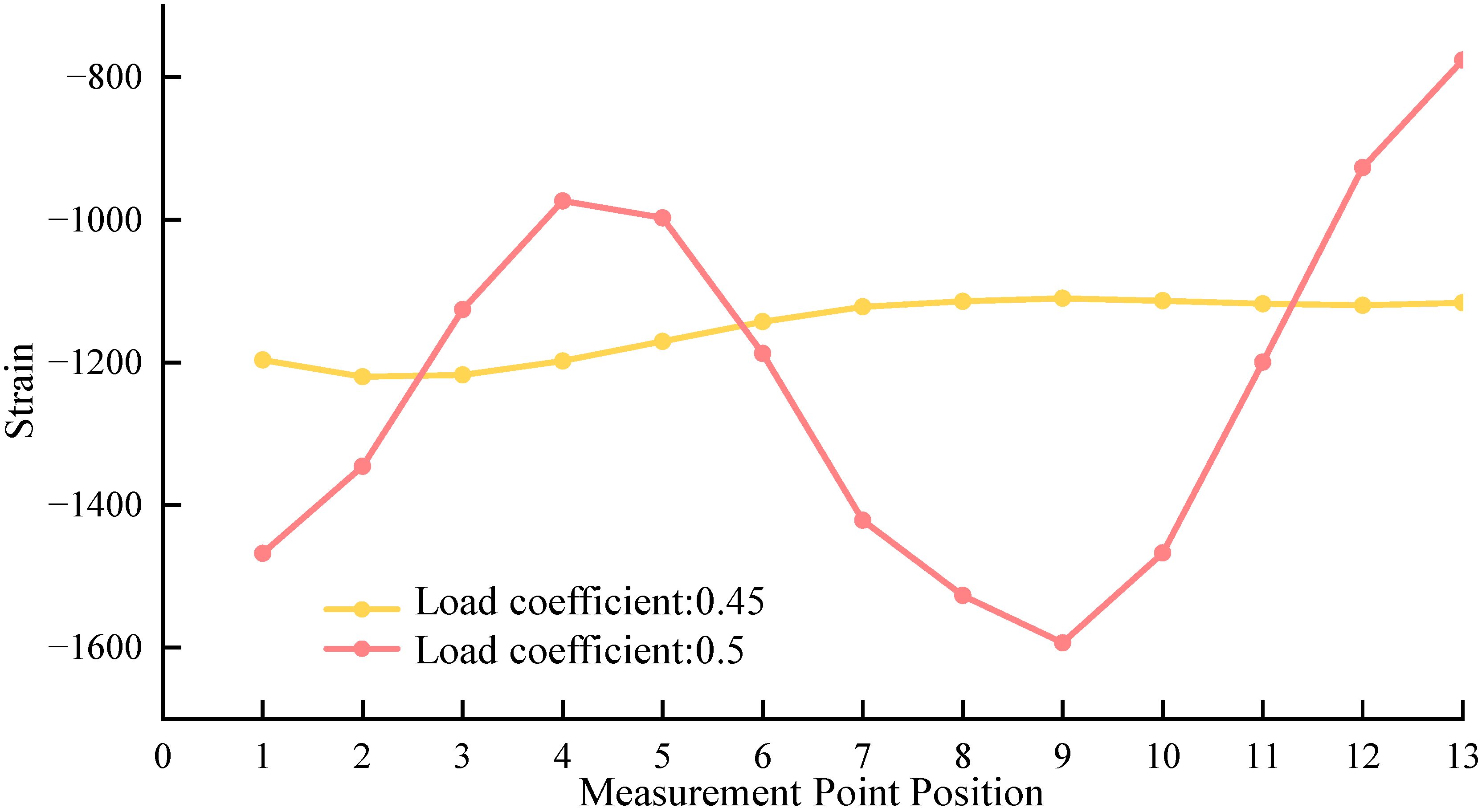

- (1)

- Upon reaching a load factor of 0.45 times the critical value, the axial strain distribution exhibits an initial buckling mode with fixed wavelength, forming a complete sinusoidal waveform characterized by a peak-to-peak strain of 140 με. The spatial positioning of its peaks and troughs demonstrates a high degree of alignment with the phase characteristics of the first-order instability mode predicted by classical plate-shell buckling theory. This marks the initiation of buckling in the base plate, signifying the departure from planar equilibrium and entry into the pre-instability phase.

- (2)

- When the load factor increases to 0.5, the buckling morphology enters an enhanced development stage, characterized by a sudden increase in strain peak-to-peak value from 140 με to 750 με—a remarkable 434% rise. This dramatic amplification stems from the coupled interaction of membrane tension and bending deformation under geometric nonlinearity: out-of-plane buckling of the base plate induces additional tensile stress in the mid-surface, which, superimposed on the original bending stresses, leads to disproportionate strain growth. During this phase, the distance between wave peaks stabilizes at 600 mm, yielding a span-to-buckling-wavelength ratio of 1:2.34, fully consistent with theoretical analytical results for rectangular plate buckling wavelengths.

- (3)

- This evolutionary sequence reveals two fundamental mechanical mechanisms: First, the magnitude jump in strain amplitude signifies the transition of the buckling equilibrium path from the pre-buckling to post-buckling branch, reflecting physically the release of mid-surface strain energy triggered by buckling half-wave elevation, propelling the structure from an elastic stable state toward a nonlinear instability state. Second, the sustained stability of the waveform’s spatial phase confirms the energy optimization characteristic of the buckling mode, indicating that the structure inherently selects the path of minimal potential energy to achieve energy dissipation minimization. The study confirms that the initial sinusoidal waveform and its spatial evolution characteristics at a 0.45 load factor clearly indicate that the base plate of Section 2 has entered the buckling state, providing critical experimental validation for thin-walled plate buckling mechanisms.

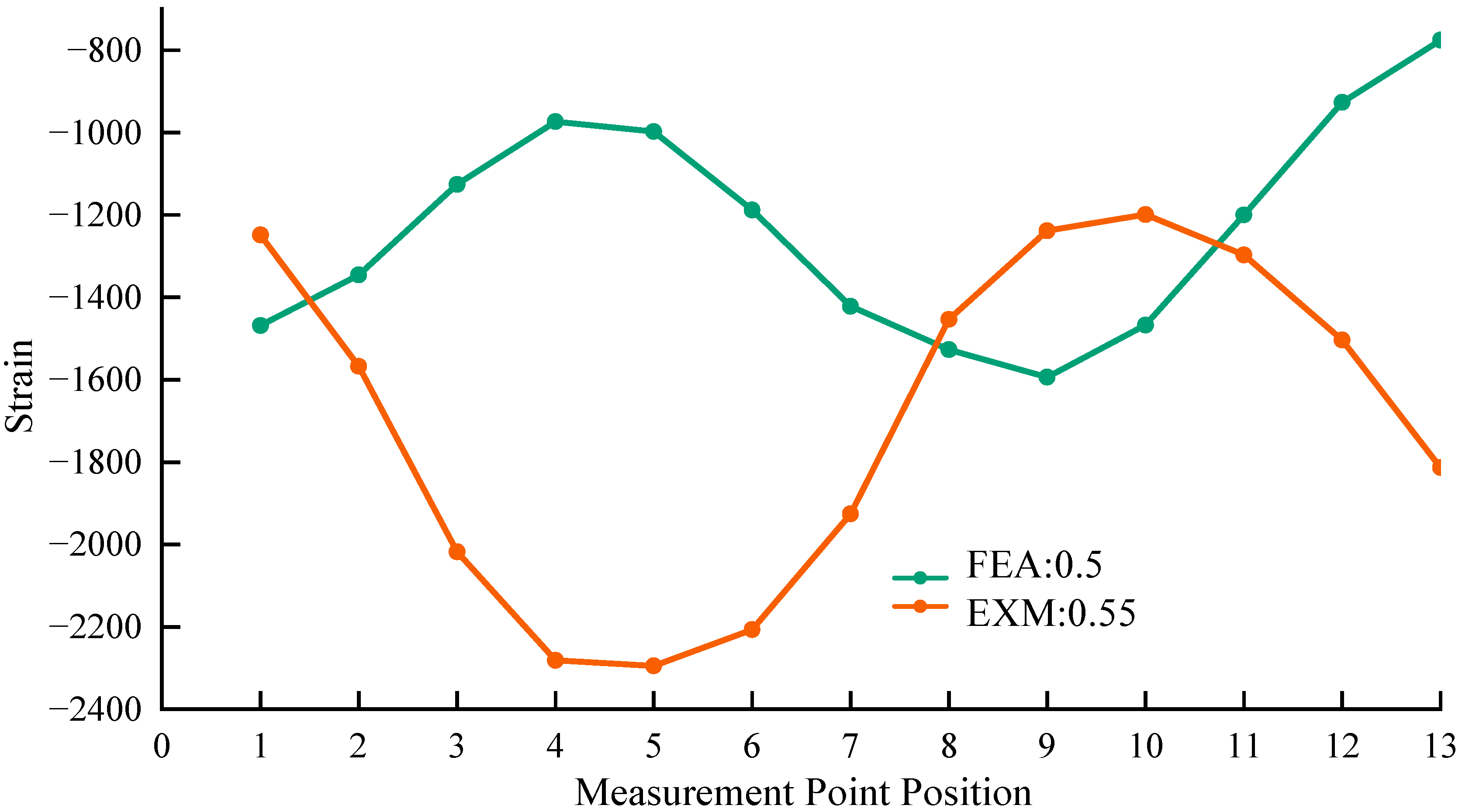

- (1)

- Based on an ideal geometric configuration, the finite element model derived a standard sinusoidal buckling wave, characterized by theoretical zero points strictly coinciding with the neutral surface and peak positions analytically determined by boundary constraints, representing an idealized defect-free buckling mode. Experimental observations revealed a buckling waveform shifted axially by 75 mm and exhibiting a cosine morphology inverted relative to the theoretical wave. This discrepancy originates from the cumulative effect of third-order defect fields introduced throughout the manufacturing process of Boom 2.

- (2)

- At the geometric level, laser cutting-induced thermal deformation creates edge gradients in individual panels, which are further amplified during welding assembly to form localized warping, causing an axial offset of the actual neutral surface. Mechanistically, residual tensile stresses from weld cooling interact asymmetrically with the compressive zone of the base material, generating an asymmetric membrane stress field that induces phase rotation in the buckling mode. This results in an axial shift of 75 mm between the experimental and theoretical waveforms along the patch direction. At the physical essence level, the thermal cycles during welding alter the microstructural texture of the wave node zone, creating localized yield strength disparities that force the buckling equilibrium path from symmetric bifurcation toward asymmetric instability, ultimately manifesting as a deterministic 180° directional inversion between experimental and finite element solutions.

- (3)

- This phenomenon validates the sequence-dependent regulatory role of initial defects in thin-walled box beam buckling behavior: manufacturing processes introduce coupled chains of geometric imperfections, residual stresses, and microstructural defects that modify the structural potential energy surface topology. This prompts the critical buckling mode to migrate along specific hypersurfaces in the phase space, ultimately manifesting as deterministic phase and directional shifts in the waveform. The discrepancy between finite element and experimental waveforms is not a contradiction of mechanical principles but an inevitable consequence of the interaction between the ideal model and actual manufacturing defects in the structure.

- (4)

- As core load-bearing components of heavy machinery, boom performance and reliability directly determine equipment operational safety. Common structural overweight issues in multi-section boom systems of large-scale heavy machinery not only increase the self-weight load of the boom system but also disrupt load distribution rationality through force transmission coupling effects, posing potential impacts on carrying stability and service safety. Therefore, lightweight optimization of boom sections represents a crucial research direction for enhancing the comprehensive performance of boom systems. Scientific lightweight design can effectively reduce boom self-weight while synergistically decreasing the load-bearing burden of undercarriage structures, improving overall anti-overturning performance, and optimizing equipment load distribution. This provides technical support for enhancing boom mechanical performance and extending service life, holding significant academic and engineering value in promoting the development of heavy machinery toward lightweighting, efficiency enhancement, and extended service life.

5. Conclusions

- Clear buckling mechanism: The boom base plate undergoes buckling deformation when the load coefficient ranges from 0.45 to 0.5, with the strain curve presenting a typical sine waveform. The wavelength is consistent with the theoretical prediction, which confirms the instability mechanism of thin-walled plates when the in-plane compressive stress exceeds the critical value.

- Relationship between load and deformation: The buckling deformation has a nonlinear relationship with the load. After the load exceeds the critical threshold, the strain amplitude increases sharply, the waveform amplitude rises significantly, and the buckling mode enters the stage of intensified development. This is consistent with the theoretical expectation of the coupling effect between geometric nonlinearity and material plasticity.

- Consistency between simulation and experiment: The finite element simulation results are highly consistent with the experimental data, verifying the accuracy and applicability of the model and providing a reliable numerical tool for the buckling analysis of thin-walled structures.

- Failure mode: The structure suffers local buckling failure under the ultimate load, and the failure location is consistent with the simulation prediction. This indicates that the stress concentration in the connection area is the key factor leading to failure.

- Based on the research findings, a box girder buckling evaluation criterion with both scientific rigor and engineering applicability is established. This criterion must satisfy two core conditions: first, the surface of the box girder must exhibit typical buckling ripples, forming a visual buckling characterization; second, during the buckling critical mutation stage, the strain amplitude must reach and exceed 40%.

- The boom involved in the buckling accident discussed in this paper adopted the measure of optimizing plate thickness, with the original plate thickness increased by 1 mm. For similar or analogous thin-walled box-section structures, the buckling deformation can be suppressed by means of design approaches such as optimizing plate thickness and adding stiffening ribs, thereby significantly improving the anti-instability performance and service safety level of the structures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, T.; Zhong, M.; Fei, L.G. Selection of high—Arm fire trucks for urban emergency preparedness based on evidential linguistic critic-bwm approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 287, 128064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, J.H.; Chen, T. Research status and development trends of rescue equipment for major natural disasters. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 21, 10552–10565. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Lin, J.; Chen, T.M.; Lin, X.; Song, Z.Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, B.B. Research on the heavy powder multifunctional elevating firetruck. Fire Sci. Technol. 2018, 37, 788–790. [Google Scholar]

- Wesierski, T. Study of the extent and degree of water and heavy foam coverage of streams generated by a firefighting vehicle equipped with an SO3 jet engine. Fire Saf. J. 2023, 140, 103870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Su, A.D.; Yang, H. Local buckling behavior and bearing capacity of cold-formed S700 high strength steel built-up box-section stub columns. Thin Walled Struct. 2025, 216, 113590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lan, X.Y.; Chen, J.B. Local buckling behaviour and CSM-based improved design method for high strength steel tubular beam-columns. Thin Walled Struct. 2025, 213, 113232. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.C.; Su, A.D.; Wang, Y.Y. Flexural buckling behaviour and resistances of S700 high strength cold-formed steel (CFS) built-up I-section columns. Thin Walled Struct. 2025, 211, 113068. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.S.; Choi, S.K. Failure analysis of connecting bolts in the collapsed tower crane. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2013, 36, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Qiu, X.M.; Zhou, Z.P.; Fu, Y.; Xing, F.; Zhao, E. Buckling failure analysis of all-terrain crane telescopic boom section. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2015, 57, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.R.; Hassan, S.F.; Amin, M.A.; Arif-Uz-Zaman, K.; Karim, M.A. Failure Analysis of a Mobile Crane: A Case Study. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2018, 18, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Fuentes, L.; Torres-López, M.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, M.A.L.; Garcia-Sanchez, E. Failure analysis of steel wire rope used in overhead crane system. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 118, 104893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, R.A. Failure analysis of a collapsed crane boom. Adv. Mater. Process. 1999, 156, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Deng, M. Research on luffing vibration characteristics of aerial work platform boom. J. Vib. Shock. 2020, 39, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, P.B.; Ferreira, A.J.M.; Gomes, H.M.; Tita, V. Trigonometric shear deformation theories for geometric nonlinear analysis of curved composite laminated shells: Post-buckling prediction using a parallelized approach. Thin Walled Struct. 2025, 214, 113379. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.H.; Shi, K.Z.; Xu, J.Z. Compression buckling and post-buckling behavior of web structures for wind turbine blades. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2023, 44, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Xie, T.; Qin, Y.X. Buckling failure analysis of slender composite structure with telescopic boom and truss. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2024, 24, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Rizzi, N.L.; Eremeyev, V.A.; Reccia, E.; Cazzani, A. Post-buckling behaviour of corrugated-edge shells: Numerical insights. Structures 2024, 65, 106758. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.H.; Yang, C.L.; Xu, X.P.; Song, D.; Wu, F. Layout design of stiffened plates for large-scale box structure under moving loads based on topology optimization. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8843657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Shao, F.; Bai, L.Y.; Xie, X.; He, X. Experimental research on local buckling of BS700 high-strength steel thin-walled box-section members under axial compression. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 2299–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Ni, M.; Xie, X.K.; Bai, L.; He, L. Local and global interactive buckling capacity of thin-walled box-section members of bs700 high—Strength steel under axial compression. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9259324. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.J.; Tang, Z.C.; Chen, B.; Han, T. Simulation and analysis of mechanical properties of large rotating steel structure based on cae technology. Adv. Roll. Equip. Technol. 2011, 145, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patuelli, C.; Cestino, E.; Frulla, G. A nonlinear beam finite element with bending–torsion coupling formulation for dynamic analysis with geometric nonlinearities. Aerospace 2024, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.W.; Jia, J.R.; Chen, H.Z.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, Q.J.; Yang, J.L.; Tao, Y.; Liu, M. Linear and nonlinear analysis of hoisting for thin-plate blocks of cruise ships. Ship Ocean. Eng. 2024, 53, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, E.; Saxena, K. Buckling analysis of folded structures. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Wang, J.W.; Liang, Y.N.; Peng, B.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y. Optimum design research on the link mechanism of the jp72 lifting jet fire truck boom system. J. Mech. Transm. 2024, 48, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.S.; Yan, S.; Rasmussen, K.J.R. Test-and-fe-based method for obtaining complete stress-strain curves of structural steels including fracture. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 224, 109095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, C.A.; Gantes, C.J. Comparison of alternative algorithms for buckling analysis of slender steel structures. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2012, 44, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Su, Y.C.; Xu, G.N.; Su, J.F.; Liu, B.B.; Yang, L. Fast prediction method for fatigue life of pump truck boom structure based on ensemble learning model. J. Mech. Strength 2025, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.Z.; Li, W.J.; Liu, Y.H. Fatigue life prediction for boom structure of concrete pump truck. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 60, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Jang, B.S. Fatigue life prediction of ship and offshore structures under wide-banded non-Gaussian random loadings: Part II: Extension to wide-banded non-Gaussian random processes. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2021, 106, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somodi, B.; Kövesdi, B. Residual stress measurements on welded square box sections using steel grades of S235-S960. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018, 123, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhang, L.B.; Wang, W.Y. Test on post-fire residual mechanical properties of high strength Q690 steel considering tensile stress in fire. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 194, 107340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.J.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.Q. Experimental and constitutive model study of structural steel under cyclic loading. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharshiduzzaman, M.; Gianneo, A.; Bernasconi, A. Experimental analysis of the response of fiber bragg grating sensors under non-uniform strain field in a twill woven composite. J. Compos. Mater. 2019, 53, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Su, A.D.; Yang, H. S890 hot-rolled ultra-high strength steel (UHSS) seamless circular hollow section beam-columns: Testing, modelling and design. Thin Walled Struct. 2024, 197, 111583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, E.H. The mean and standard deviation: What does it all mean? J. Surg. Res. 2004, 119, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibzadeh, F. On using standard deviation or standard error of the mean. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 50, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Laod Coefficient | F1/kN | F2/kN | Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.20 | 47.8 | −56.4 | Rated Load 20% |

| 0.25 | 59.8 | −70.5 | Rated Load 25% |

| … | … | … | … |

| 1.00 | 239.2 | −282.1 | Rated Load 100% |

| 1.05 | 251.2 | −296.2 | Rated Load 105% |

| … | … | … | … |

| 1.90 | 454.6 | −536.0 | Rated Load 190% |

| Material Property | Q890D |

|---|---|

| Density (kg/m3) | 7850 |

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) | 210 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.3 |

| Tensile Yield Stress (MPa) | 890 |

| Ultimate Tensile Stress (MPa) | 1000 |

| Load Coefficient | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | B8 | B9 | B10 | B11 | B12 | B13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −865.3 | −861.4 | −847.2 | −831.6 | −818.3 | −808.0 | −799.3 | −794.9 | −787.9 | −782.1 | −776.0 | −770.0 | −763.5 |

| 0.2 | −808.6 | −848.8 | −879.3 | −872.5 | −855.0 | −830.3 | −791.0 | −766.5 | −760.1 | −761.3 | −760.4 | −769.1 | −782.2 |

| 0.25 | −806.9 | −849.0 | −904.9 | −892.1 | −875.7 | −843.8 | −787.8 | −790.6 | −763.2 | −759.4 | −758.0 | −775.3 | −796.3 |

| 0.3 | −919.7 | −999.1 | −1053.2 | −1093.2 | −1139.6 | −1066.8 | −1025.9 | −942.3 | −933.1 | −884.2 | −943.0 | −982.4 | −987.6 |

| 0.35 | −1145.6 | −1216.0 | −1302.4 | −1344.4 | −1358.7 | −1305.4 | −1228.1 | −1109.5 | −1073.8 | −1043.0 | −1105.8 | −1146.1 | −1274.6 |

| 0.4 | −1296.0 | −1392.2 | −1460.7 | −1547.9 | −1516.8 | −1498.7 | −1374.8 | −1297.8 | −1220.7 | −1139.7 | −1253.2 | −1293.1 | −1404.5 |

| 0.45 | −1421.9 | −1506.8 | −1585.4 | −1638.9 | −1670.7 | −1673.1 | −1555.1 | −1410.7 | −1372.2 | −1281.4 | −1442.4 | −1540.6 | −1601.4 |

| 0.5 | −1510.6 | −1619.8 | −1840.9 | −1910.9 | −1943.6 | −1850.3 | −1752.6 | −1512.9 | −1401.1 | −1309.7 | −1471.0 | −1601.6 | −1782.1 |

| 0.55 | −1248.6 | −1567.5 | −2017.4 | −2281.0 | −2294.4 | −2206.5 | −1925.8 | −1453.3 | −1238.4 | −1198.8 | −1296.8 | −1503.6 | −1813.1 |

| 0.6 | −1158.7 | −1596.2 | −2109.2 | −2393.8 | −2457.0 | −2375.2 | −2085.6 | −1296.4 | −1103.7 | −1038.3 | −1150.2 | −1450.7 | −1903.2 |

| 0.65 | −1068.8 | −1624.9 | −2171.1 | −2580.8 | −2654.6 | −2518.7 | −2132.6 | −1215.9 | −919.7 | −869.1 | −1103.1 | −1523.2 | −2033.2 |

| 0.7 | −998.9 | −1653.6 | −2232.9 | −2663.5 | −2727.6 | −2588.2 | −2179.6 | −1196.8 | −853.7 | −798.6 | −1074.4 | −1575.1 | −2143.3 |

| 0.75 | −949.0 | −1682.3 | −2294.7 | −2746.2 | −2800.7 | −2657.7 | −2226.6 | −1177.8 | −787.6 | −728.1 | −1045.6 | −1626.9 | −2253.3 |

| 0.8 | −899.1 | −1711.0 | −2356.6 | −2828.9 | −2873.7 | −2727.2 | −2273.6 | −1158.7 | −721.6 | −657.6 | −1016.9 | −1678.8 | −2363.4 |

| 0.85 | −849.2 | −1739.7 | −2418.4 | −2911.6 | −2946.8 | −2796.7 | −2320.6 | −1139.7 | −655.5 | −587.1 | −988.1 | −1730.6 | −2473.4 |

| 0.9 | −799.3 | −1768.4 | −2480.2 | −2994.3 | −3019.8 | −2866.2 | −2367.6 | −1120.6 | −589.5 | −516.6 | −959.4 | −1782.5 | −2583.5 |

| 0.95 | −749.4 | −1797.1 | −2542.0 | −3077.0 | −3092.9 | −2935.7 | −2414.6 | −1101.6 | −523.4 | −446.1 | −930.6 | −1834.3 | −2693.5 |

| 1 | −699.5 | −1825.8 | −2603.9 | −3159.7 | −3165.9 | −3005.2 | −2461.6 | −1082.5 | −457.4 | −375.6 | −901.9 | −1886.2 | −2753.6 |

| 1.05 | −649.6 | −1854.5 | −2665.7 | −3242.4 | −3239.0 | −3074.7 | −2508.6 | −1063.5 | −391.3 | −305.1 | −873.1 | −1938.0 | −2813.6 |

| 1.1 | −599.7 | −1883.2 | −2727.5 | −3325.1 | −3312.0 | −3144.2 | −2555.6 | −1044.4 | −325.3 | −234.6 | −844.4 | −1989.9 | −2923.7 |

| 1.15 | −549.8 | −1911.9 | −2789.4 | −3407.8 | −3385.1 | −3213.7 | −2602.6 | −1025.4 | −259.2 | −164.1 | −815.6 | −2041.7 | −3033.7 |

| 1.2 | −499.9 | −1940.6 | −2851.2 | −3490.5 | −3458.1 | −3283.2 | −2649.6 | −1006.3 | −193.2 | −93.6 | −786.9 | −2093.6 | −3143.8 |

| Load Coefficient | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | B8 | B9 | B10 | B11 | B12 | B13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −863.7 | −861.4 | −847.1 | −831.4 | −818.3 | −808.0 | −799.2 | −794.7 | −787.9 | −782.0 | −776.0 | −770.0 | −763.5 |

| 0.2 | −824.6 | −822.6 | −809.8 | −795.9 | −784.5 | −775.7 | −768.2 | −764.4 | −758.7 | −753.9 | −748.9 | −744.0 | −738.6 |

| 0.25 | −799.7 | −797.9 | −785.9 | −772.9 | −762.4 | −754.4 | −747.5 | −744.1 | −739.0 | −734.7 | −730.2 | −725.9 | −721.0 |

| 0.3 | −885.9 | −885.9 | −873.2 | −858.6 | −846.5 | −837.3 | −829.8 | −826.2 | −821.1 | −817.0 | −812.5 | −808.2 | −803.2 |

| 0.35 | −1010.3 | −1014.6 | −1001.6 | −984.1 | −968.6 | −956.5 | −947.2 | −943.1 | −938.1 | −934.5 | −930.4 | −926.1 | −920.7 |

| 0.4 | −1102.4 | −1112.6 | −1101.4 | −1081.9 | −1062.3 | −1046.2 | −1034.3 | −1029.6 | −1025.1 | −1023.0 | −1020.3 | −1017.0 | −1011.6 |

| 0.45 | −1196.5 | −1220.0 | −1217.5 | −1198.1 | −1170.5 | −1142.9 | −1121.8 | −1114.4 | −1110.2 | −1113.4 | −1117.8 | −1119.9 | −1116.4 |

| 0.5 | −1468.0 | −1345.8 | −1125.9 | −973.4 | −997.2 | −1187.7 | −1421.5 | −1527.0 | −1593.7 | −1467.3 | −1199.8 | −926.7 | −775.6 |

| 0.55 | −830.4 | −995.2 | −1473.8 | −1918.1 | −2055.1 | −1773.4 | −1157.4 | −764.6 | −285.0 | −200.6 | −496.9 | −1069.7 | −1638.8 |

| 0.6 | −638.6 | −734.0 | −1390.5 | −2051.7 | −2335.4 | −2115.9 | −1371.1 | −814.9 | −79.6 | 145.2 | −69.4 | −699.1 | −1510.8 |

| 0.65 | −436.2 | −472.4 | −1329.7 | −2185.4 | −2546.6 | −2355.6 | −1521.5 | −837.2 | 97.9 | 403.9 | 236.8 | −421.5 | −1416.6 |

| 0.7 | −241.6 | −99.5 | −1136.2 | −2245.1 | −2714.2 | −2604.5 | −1784.8 | −996.7 | 192.7 | 631.3 | 550.2 | −41.6 | −1178.7 |

| 0.75 | −100.9 | 367.6 | −976.2 | −2265.3 | −2865.6 | −2792.6 | −1887.4 | −1122.6 | 275.0 | 782.7 | 750.5 | 344.2 | −933.2 |

| 0.8 | 35.0 | 536.0 | −722.5 | −2282.3 | −2931.7 | −2911.4 | −2189.3 | −1302.3 | 285.5 | 959.1 | 978.7 | 536.3 | −727.6 |

| 0.85 | 211.1 | 863.7 | −525.3 | −2324.8 | −3050.6 | −3042.5 | −2356.0 | −1418.7 | 370.5 | 1149.6 | 1191.8 | 806.4 | −524.8 |

| 0.9 | 393.6 | 1106.9 | −425.7 | −2400.0 | −3153.4 | −3135.7 | −2444.8 | −1446.9 | 494.8 | 1319.5 | 1360.6 | 992.7 | −428.1 |

| 0.95 | 554.5 | 1340.2 | −304.6 | −2449.4 | −3240.7 | −3220.0 | −2545.8 | −1500.3 | 596.2 | 1477.8 | 1517.8 | 1182.2 | −304.0 |

| 1 | 694.1 | 1562.0 | −181.4 | −2485.0 | −3315.5 | −3292.2 | −2644.6 | −1559.8 | 686.5 | 1625.5 | 1662.1 | 1367.3 | −170.8 |

| 1.05 | 814.2 | 1772.4 | −44.9 | −2499.0 | −3375.9 | −3352.4 | −2749.6 | −1641.8 | 749.9 | 1762.5 | 1794.6 | 1550.3 | −12.6 |

| 1.1 | 1024.3 | 2042.0 | 71.0 | −2570.8 | −3473.0 | −3436.4 | −2836.0 | −1650.1 | 933.0 | 1971.8 | 1973.1 | 1759.3 | 87.4 |

| 1.15 | 1180.2 | 2261.0 | 184.8 | −2616.0 | −3551.0 | −3508.3 | −2912.1 | −1653.7 | 1105.6 | 2156.5 | 2120.8 | 1947.4 | 190.7 |

| 1.2 | 1265.1 | 2445.1 | 336.1 | −2609.9 | −3612.7 | −3573.5 | −3003.7 | −1694.0 | 1225.4 | 2315.9 | 2253.3 | 2131.5 | 324.1 |

| Load Coefficient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 6.6 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 5.6 |

| 0.25 | 0.9 | 6.0 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 10.6 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 6.4 | 9.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, W.; Cheng, K.; Zhao, Y.; Guan, B.; Wu, B.; Zhao, E. Research on Buckling Failure Test and Prevention Strategy of Boom Structure of Elevating Jet Fire Truck. Symmetry 2026, 18, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010039

Sun W, Cheng K, Zhao Y, Guan B, Wu B, Zhao E. Research on Buckling Failure Test and Prevention Strategy of Boom Structure of Elevating Jet Fire Truck. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Wuhe, Kai Cheng, Yan Zhao, Bowen Guan, Bin Wu, and Erfei Zhao. 2026. "Research on Buckling Failure Test and Prevention Strategy of Boom Structure of Elevating Jet Fire Truck" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010039

APA StyleSun, W., Cheng, K., Zhao, Y., Guan, B., Wu, B., & Zhao, E. (2026). Research on Buckling Failure Test and Prevention Strategy of Boom Structure of Elevating Jet Fire Truck. Symmetry, 18(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010039