Safe Trajectory Tracking for Robotic Manipulator with Prescribed Performance in Confined Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- This paper presents novel and robust model-free control method for robotic manipulators to tackle the aforementioned challenge. By leveraging the potential robustness of error transformation techniques, it eliminates the necessity for the robotic manipulators’ model knowledge [29], thereby achieving model-free tracking control;

- (ii)

- The proposed controller features a simple and implementation-friendly structure, requiring neither adaptive techniques [30,31,32,33,34] nor approximation-based components such as neural networks [35,36] or fuzzy logic systems [37,38]. This structural simplicity makes the controller easier to tune, and highly suitable for practical deployment on real robotic platforms.

- (iii)

- This work introduces a unified safe trajectory tracking framework that couples motion planning with control through a Monte Carlo–based search of configuration-dependent error bounds. This integration ensures safety at both the planning and control layers, allowing the reference trajectory and its admissible error bounds to be autonomously determined based on the geometric structure of the surrounding environment.

2. System Description and Problem Formulation

2.1. System Description

2.2. Problem Formulation

3. Method

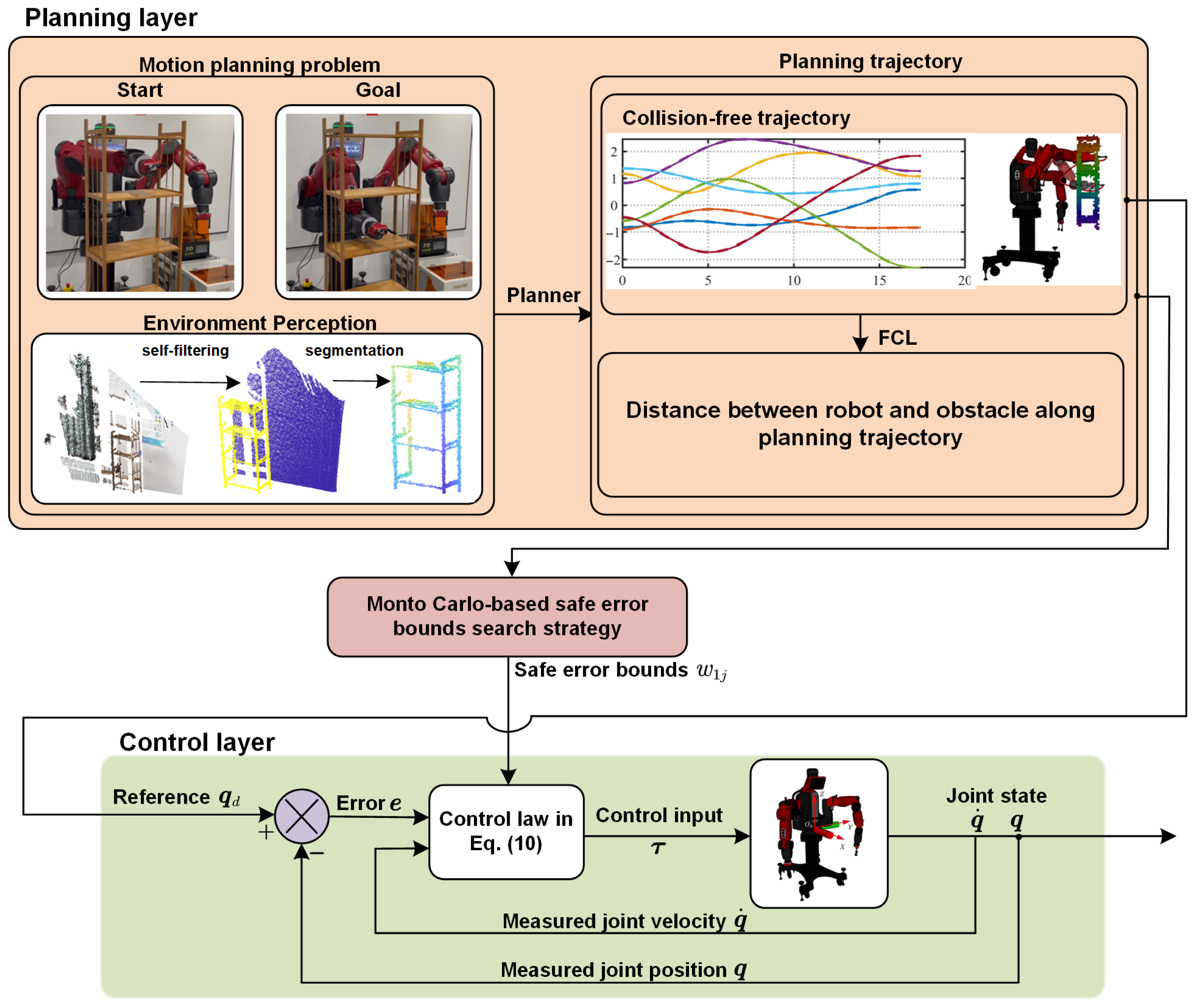

3.1. Overview of Algorithm

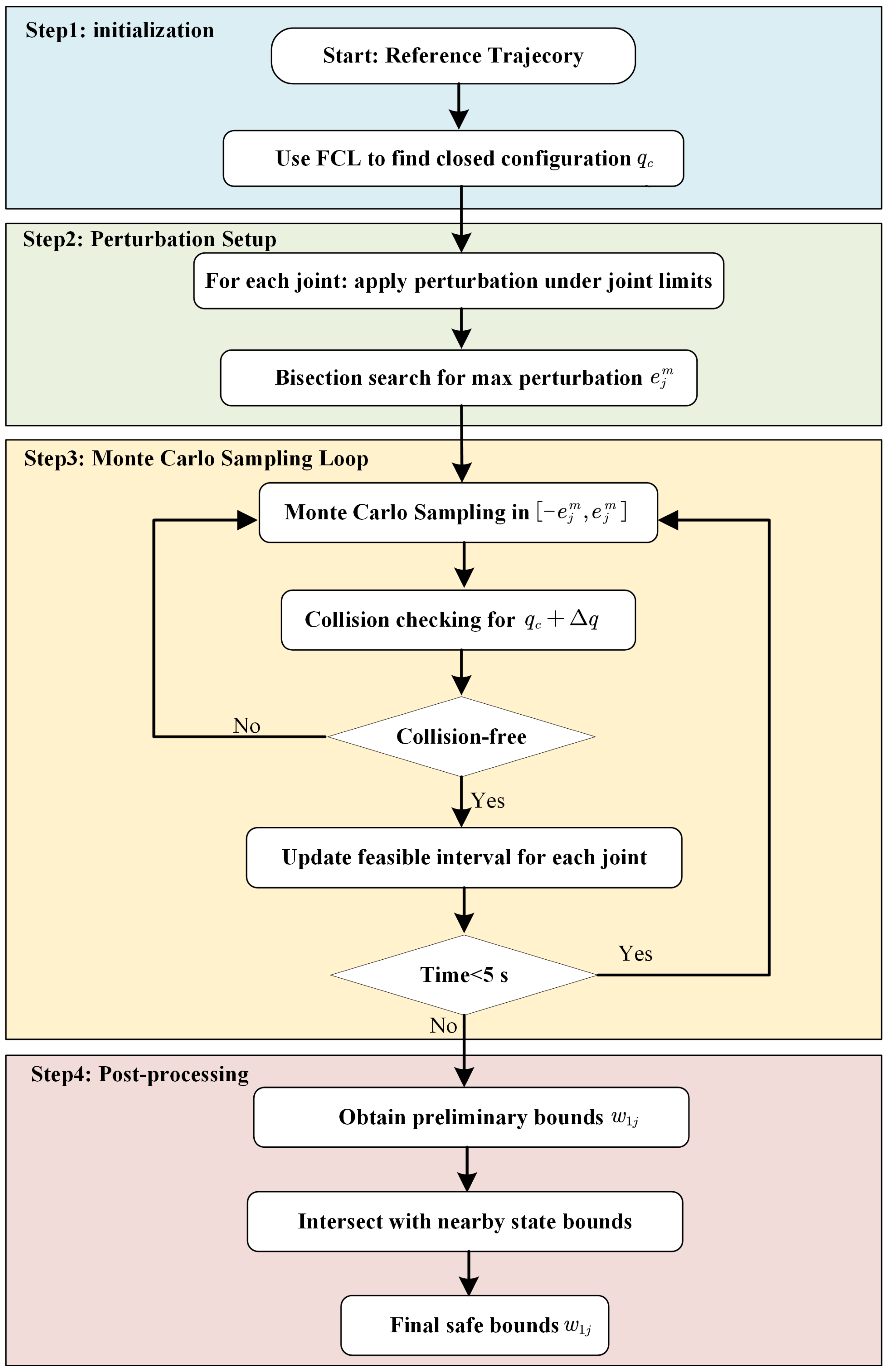

3.2. Monte Carlo–Based Search Procedure

4. Controller Design

5. Stability Analysis

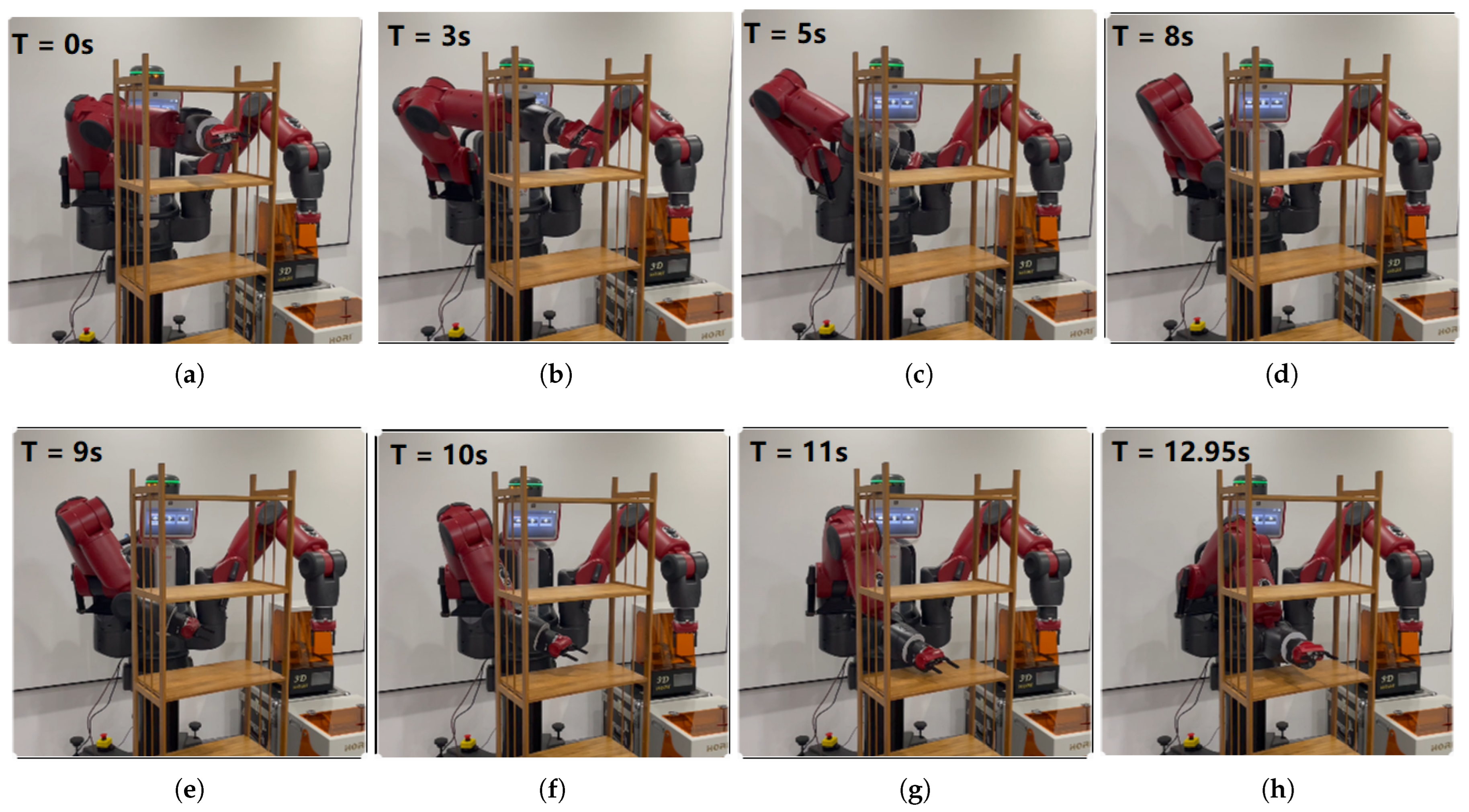

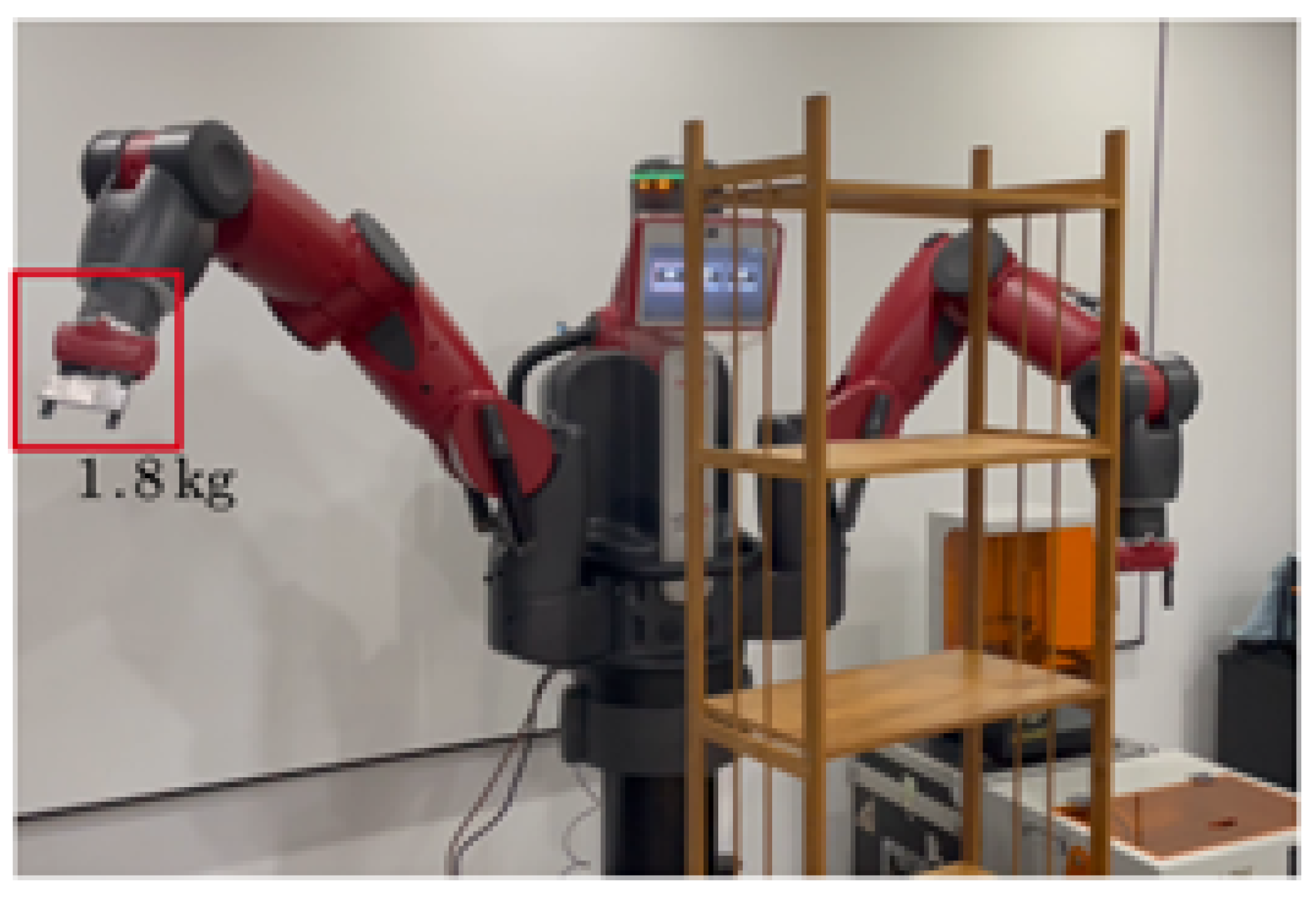

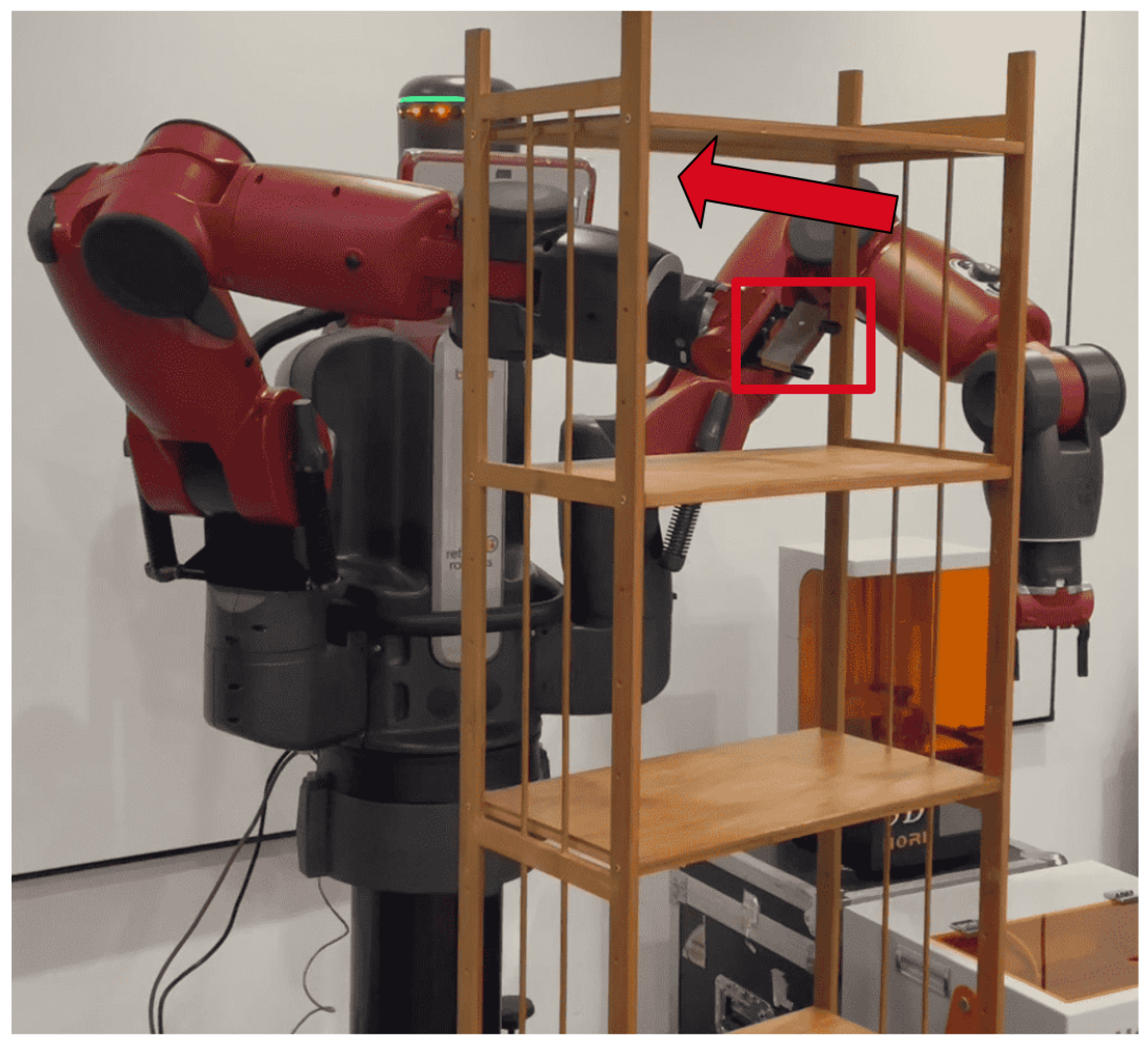

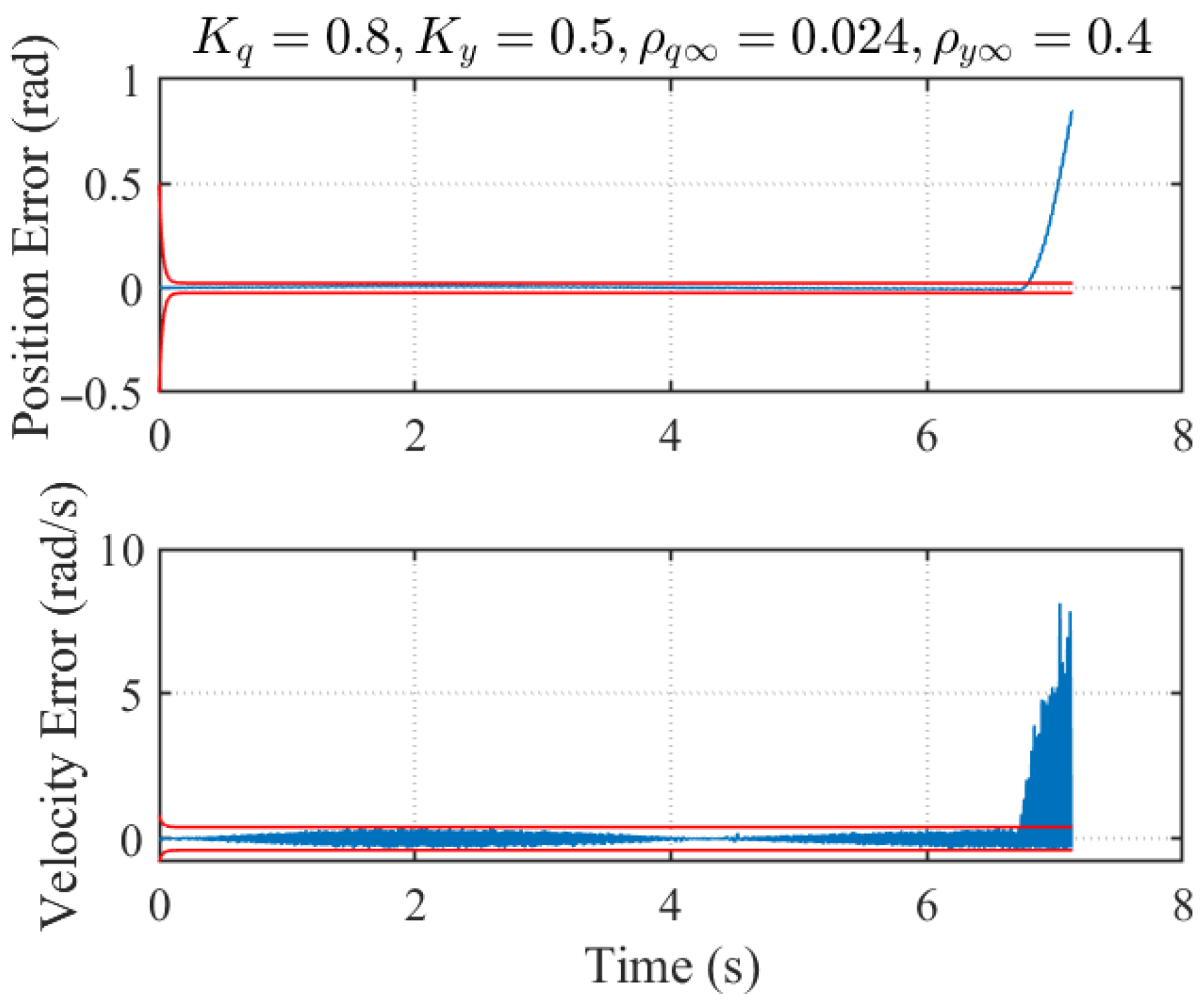

6. Experiments and Results

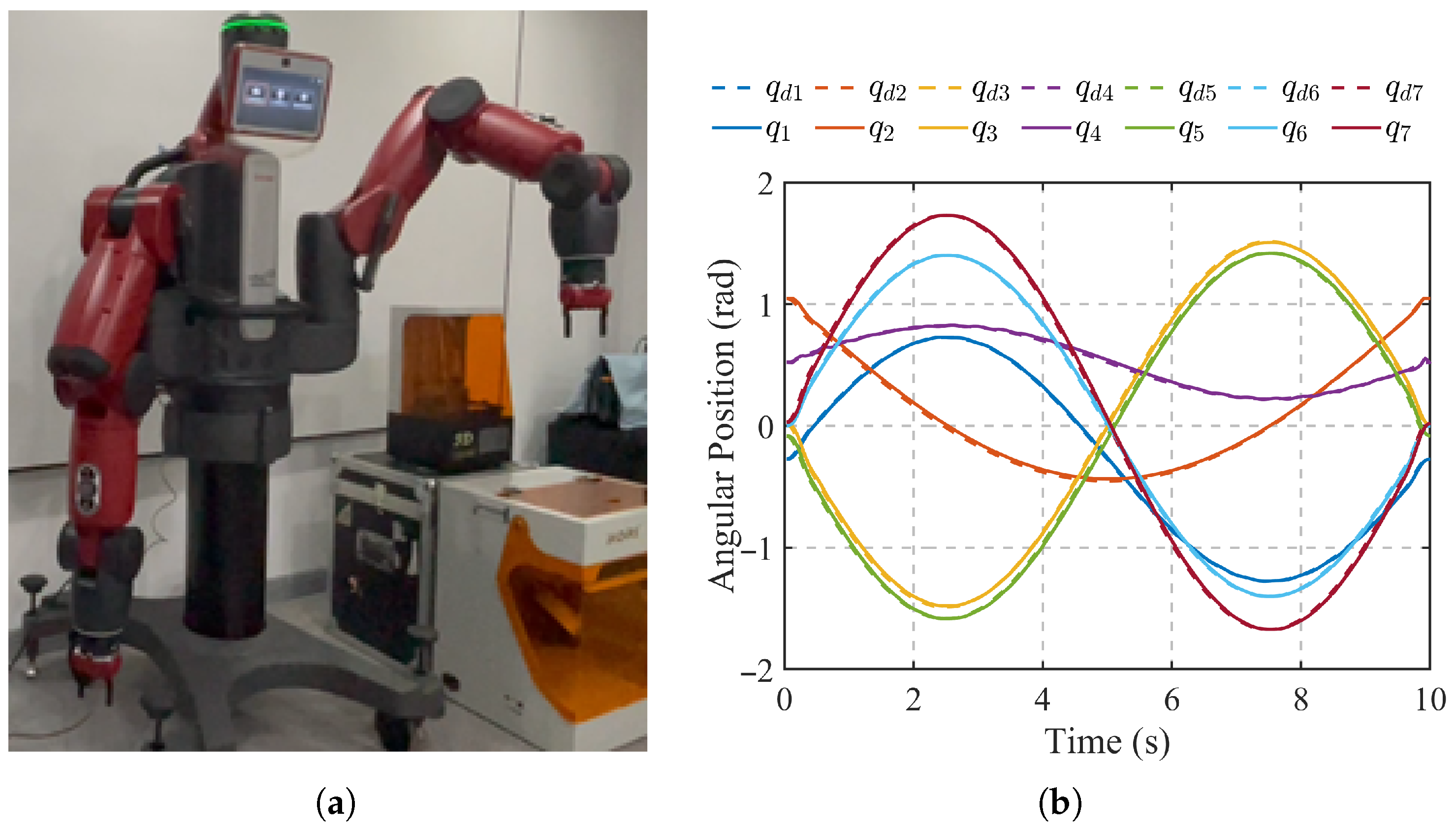

6.1. Experimental Setups

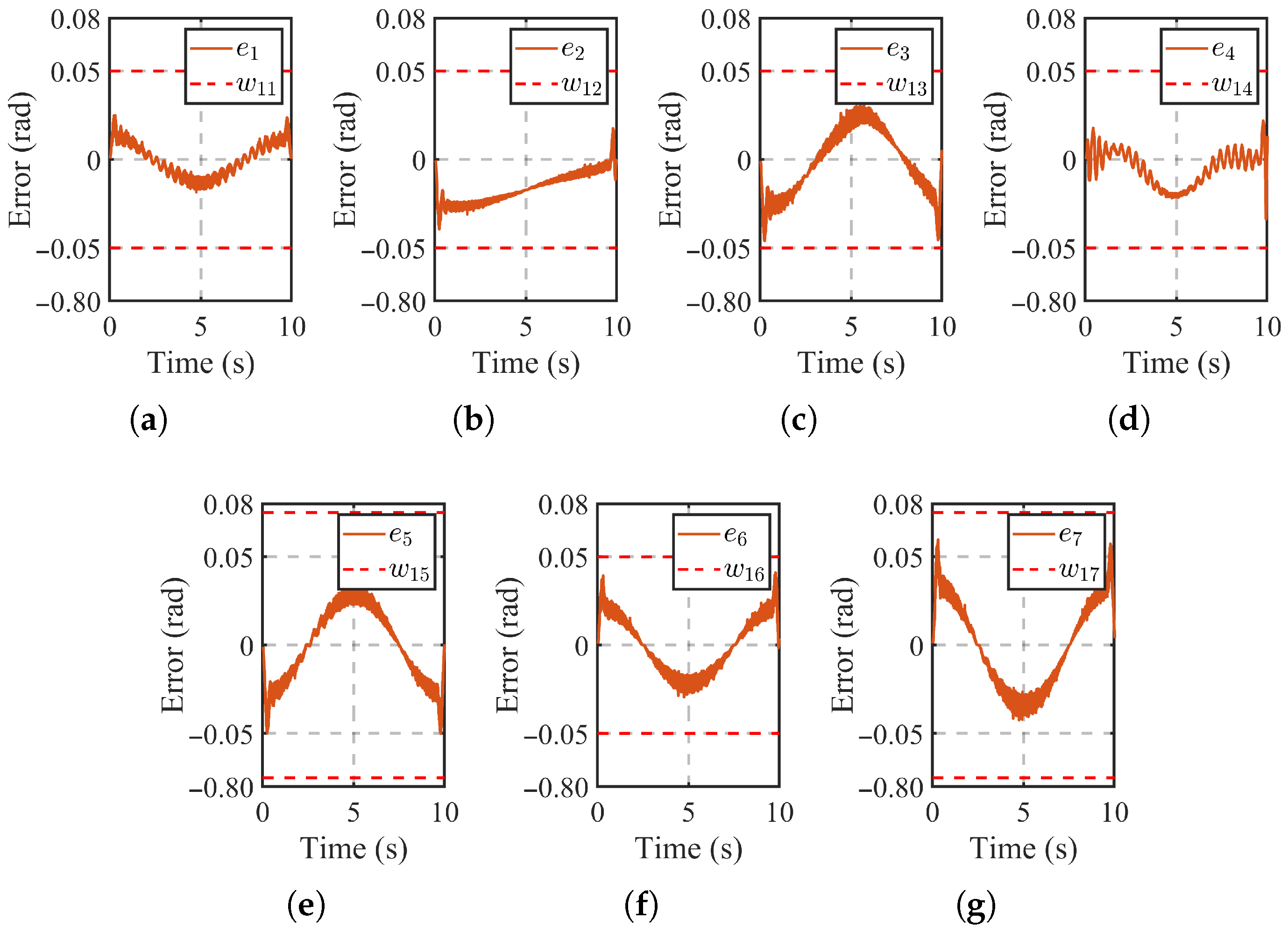

6.2. Experimental Results

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, D. Narrow Passage Path Planning Using Collision Constraint Interpolation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–23 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Orthey, A.; Toussaint, M. Section patterns: Efficiently solving narrow passage problems in multilevel motion planning. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1891–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubert, J.; Köhler, J.; Berenz, V.; Allgöwer, F.; Trimpe, S. Safe and fast tracking on a robot manipulator: Robust mpc and neural network control. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 3050–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhai, D.; Huang, T.; Xia, Y. Robust model predictive tracking control for robot manipulators with disturbances. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 4288–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gosselin, C. Optimal design of safe planar manipulators using passive torque limiters. J. Mech. Robot. 2016, 8, 011008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batkovic, I.; Ali, M.; Falcone, P.; Zanon, M. Safe trajectory tracking in uncertain environments. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 68, 4204–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orthey, A.; Chamzas, C.; Kavraki, L.E. Sampling-based motion planning: A comparative review. Annu. Rev. Control. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 7, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, M.L.; Flaieh, E.H.; Humaidi, A.J. Embedded system design of path planning for planar manipulator based on chaos A* algorithm with known-obstacle environment. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2022, 17, 4047–4064. [Google Scholar]

- Lippi, M.; Marino, A. Human multi-robot safe interaction: A trajectory scaling approach based on safety assessment. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2020, 29, 1565–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. Fuzzy adaptive fixed-time quantized feedback control for a class of nonlinear systems. Acta Autom. Sin. 2021, 47, 2823–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xu, K.; Zhang, H. Adaptive finite-time tracking control of nonlinear systems with dynamics uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 68, 5737–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, P.X. Singularity-free adaptive fixed-time tracking control for MIMO nonlinear systems with dynamic uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Part II Express Briefs 2023, 71, 1356–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ortiz, D.; Chairez, I.; Poznyak, A. Sliding-mode control of full-state constraint nonlinear systems: A barrier lyapunov function approach. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 6593–6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X. Prescribed performance control approaches, applications and challenges: A comprehensive survey. Asian J. Control 2023, 25, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wen, S.; Yan, Z.; Wen, G.; Huang, T. A survey on the control lyapunov function and control barrier function for nonlinear-affine control systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F.L.; Dawson, D.M.; Abdallah, C.T. Robot Manipulator Control: Theory and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Huang, D.; He, W.; Cheng, L. Neural control of robot manipulators with trajectory tracking constraints and input saturation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 4231–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, H.; Yao, Q.; Khan, M.I.; Moroz, I. Unified neural output-constrained control for space manipulator using tan-type barrier Lyapunov function. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 71, 3712–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajeri, M.S.; Abdullah, F.; Christofides, P.D. Control Lyapunov barrier function-based predictive control of nonlinear systems using physics-informed recurrent neural networks. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 321, 122695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Buss, M. Concurrent learning-based adaptive control of an uncertain robot manipulator with guaranteed safety and performance. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 52, 3299–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechlioulis, C.P.; Rovithakis, G.A. Robust adaptive control of feedback linearizable MIMO nonlinear systems with prescribed performance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 2090–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W. Adaptive fuzzy output-feedback control for nonaffine MIMO nonlinear systems with prescribed performance. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, A. Dynamic learning from adaptive neural control of robot manipulators with prescribed performance. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 47, 2244–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y. Adaptive neural tracking control for manipulators with prescribed performance under input saturation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2022, 28, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayiannidis, Y.; Papageorgiou, D.; Doulgeri, Z. A model-free controller for guaranteed prescribed performance tracking of both robot joint positions and velocities. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2016, 1, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Lai, N.; He, B.; Miao, Z.; Wang, Y. Low-complexity prescribed performance control for unmanned aerial manipulator robot system under model uncertainty and unknown disturbances. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2021, 18, 4632–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; Yin, Z.; Luo, J. An overview of prescribed performance control and its application to spacecraft attitude system. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 2021, 235, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Hao, L.; Yang, H.; Xiang, C. Model-free tracking control of continuum manipulators with global stability and assigned accuracy. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 52, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humaidi, A.J.; Abdulkareem, A.I. Design of Augmented Nonlinear PD Controller of Delta/Par4-Like Robot. J. Control Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 7689673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xie, N.; Shen, H.; Hu, X.; Liu, Q. Extended state observer-based adaptive prescribed performance control for a class of nonlinear systems with full-state constraints and uncertainties. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 105, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, H.; Lu, R. Adaptive prescribed performance control of a flexible-joint robotic manipulator with dynamic uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 12905–12915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Chen, C.P.; Tong, S. A novel adaptive NN prescribed performance control for stochastic nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 3196–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Adaptive prescribed performance control of unmanned aerial manipulator with disturbances. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 20, 1804–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ferik, S.; Hashim, H.A.; Lewis, F.L. Neuro-adaptive distributed control with prescribed performance for the synchronization of unknown nonlinear networked systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 48, 2135–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Ahn, C.K.; Liu, L.; Liu, C. Prescribed performance fixed-time recurrent neural network control for uncertain nonlinear systems. Neurocomputing 2019, 363, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerari, N.; Chemachema, M. Robust adaptive neural network prescribed performance control for uncertain CSTR system with input nonlinearities and external disturbance. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 10541–10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, Y. Fuzzy adaptive optimization prescribed performance control for nonlinear vehicle platoon. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 32, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Yu, J.; Shi, P. Observer-based finite-time adaptive fuzzy control with prescribed performance for nonstrict-feedback nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 30, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.M.; Li, Z.; Sastry, S.S. A Mathematical Introduction to Robotic Manipulation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Yang, G.H. Fault-tolerant output-constrained control of unknown Euler–Lagrange systems with prescribed tracking accuracy. Automatica 2020, 111, 108606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Yang, G.H. Adaptive fuzzy fault-tolerant control of uncertain Euler–Lagrange systems with process faults. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 28, 2619–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Baek, J.; Kwon, W.; Han, S. An adaptive model uncertainty estimator using delayed state-based model-free control and its application to robot manipulators. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 4573–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Chitta, S.; Manocha, D. FCL: A general purpose library for collision and proximity queries. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, St Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 3859–3866. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Yang, G.H. Fault-tolerant fixed-time trajectory tracking control of autonomous surface vessels with specified accuracy. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 4889–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, A.; Wurm, K.M.; Bennewitz, M.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. OctoMap: An efficient probabilistic 3D mapping framework based on octrees. Auton. Robot 2013, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Joint | Min. Pos. (rad) | Max. Pos. (rad) | Max. Vel. (rad/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | −1.7016 | 1.7016 | 3.5 |

| S1 | −2.147 | 1.047 | 3.5 |

| E0 | −3.0541 | 3.0541 | 3.5 |

| E1 | −0.05 | 2.618 | 3.5 |

| W0 | −3.059 | 3.059 | 4.0 |

| W1 | −1.5707 | 2.094 | 4.0 |

| W2 | −3.059 | 3.059 | 4.0 |

| Joint | Joint Trajectories | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | 0.05 | 3 | 15 | 35 | |

| S1 | 0.05 | 3.5 | 15 | 35 | |

| E0 | 0.05 | 3.5 | 15 | 35 | |

| E1 | 0.05 | 3.5 | 10 | 30 | |

| W0 | 0.075 | 3.5 | 10 | 30 | |

| W1 | 0.05 | 3.5 | 15 | 30 | |

| W2 | 0.075 | 3.5 | 10 | 15 |

| Joint | Proposed PPC | PID | Yiannis’s PPC |

|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | 0.0149 | 0.0202 | 0.0104 |

| E0 | 0.0053 | 0.0151 | 0.0052 |

| Joint | Proposed PPC | PID | Yiannis’s PPC |

|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | 0.0169 | 0.0284 | 0.0093 |

| E0 | 0.0100 | 0.0259 | 0.0065 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Gao, X.; Zhang, K. Safe Trajectory Tracking for Robotic Manipulator with Prescribed Performance in Confined Spaces. Symmetry 2026, 18, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010002

Li X, Gao X, Zhang K. Safe Trajectory Tracking for Robotic Manipulator with Prescribed Performance in Confined Spaces. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xingchen, Xifeng Gao, and Kai Zhang. 2026. "Safe Trajectory Tracking for Robotic Manipulator with Prescribed Performance in Confined Spaces" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010002

APA StyleLi, X., Gao, X., & Zhang, K. (2026). Safe Trajectory Tracking for Robotic Manipulator with Prescribed Performance in Confined Spaces. Symmetry, 18(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010002