Specifying the Measures of the Time Delays in Gravitationally Lensed Quasar Q2237+0305 Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

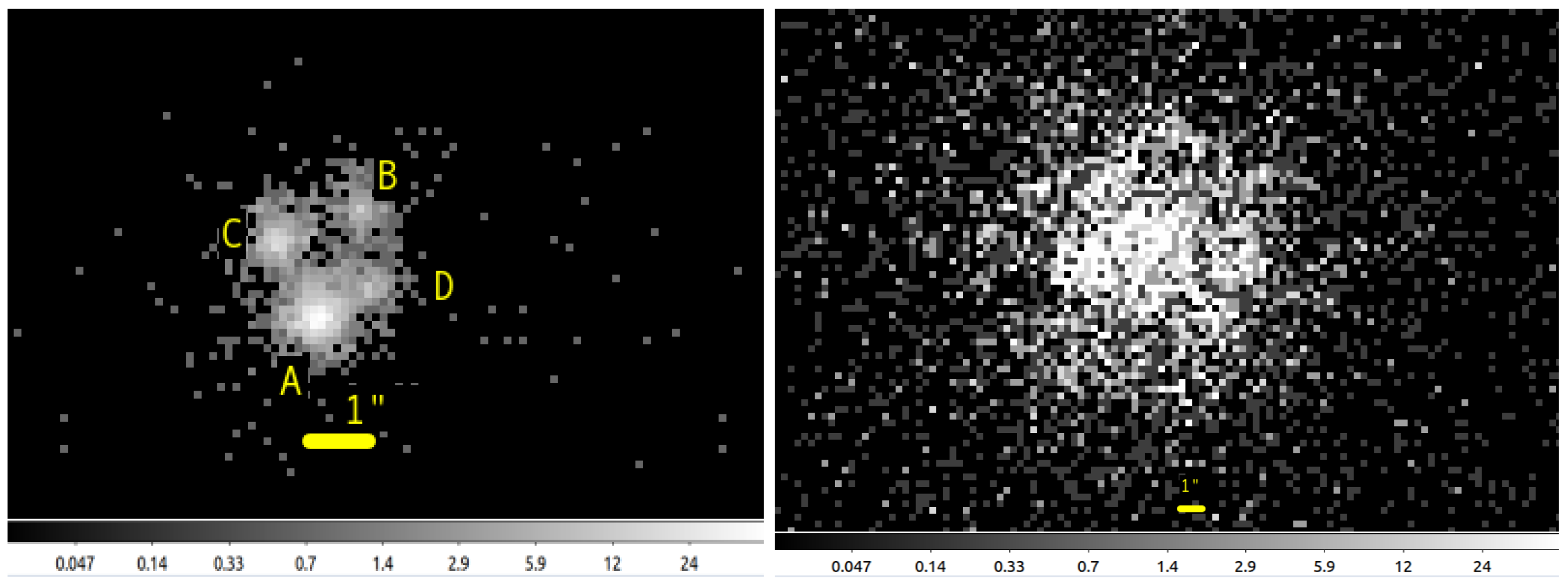

2. Q2237+0305 the Einstein Cross

3. The Data Reduction

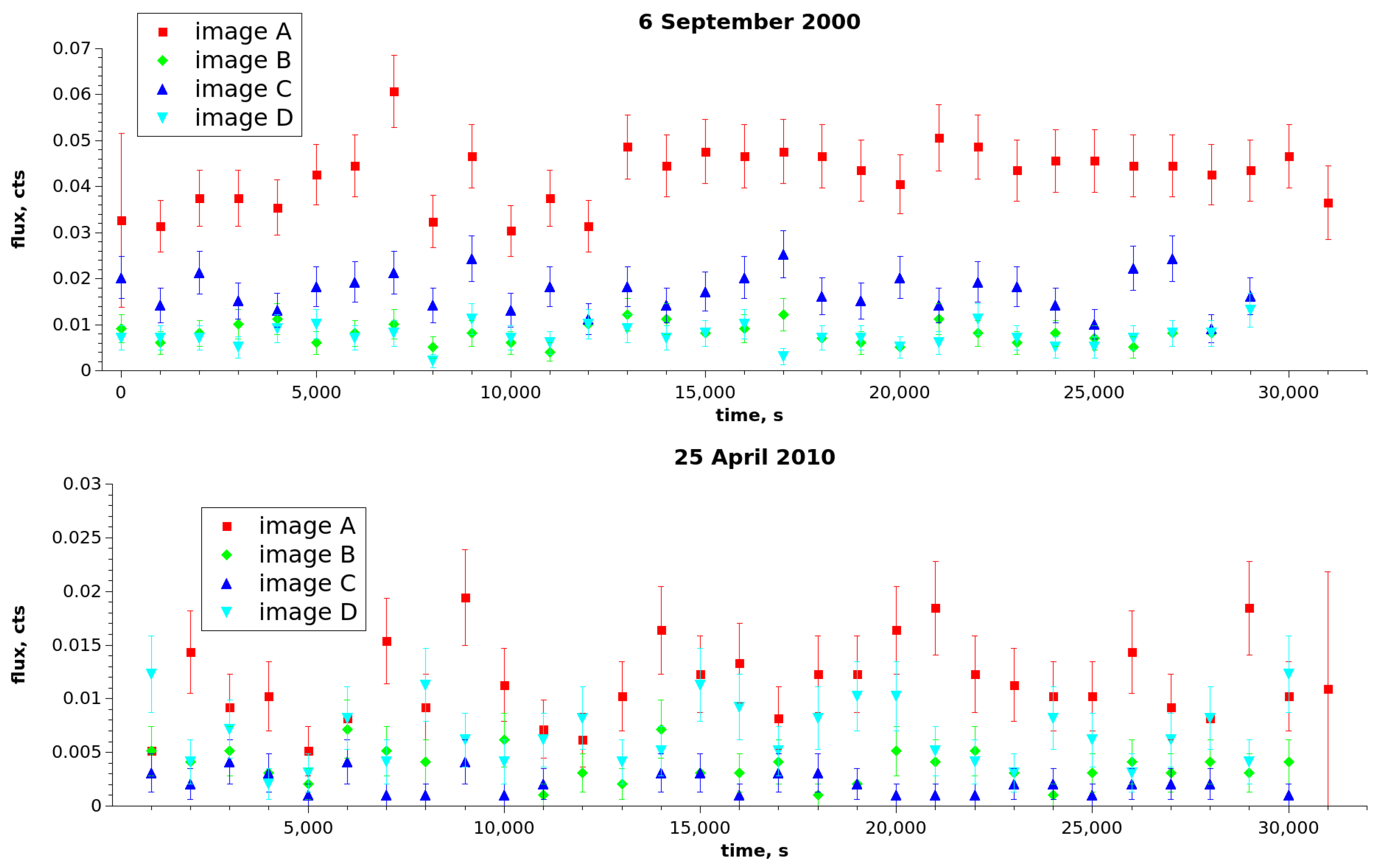

3.1. Chandra

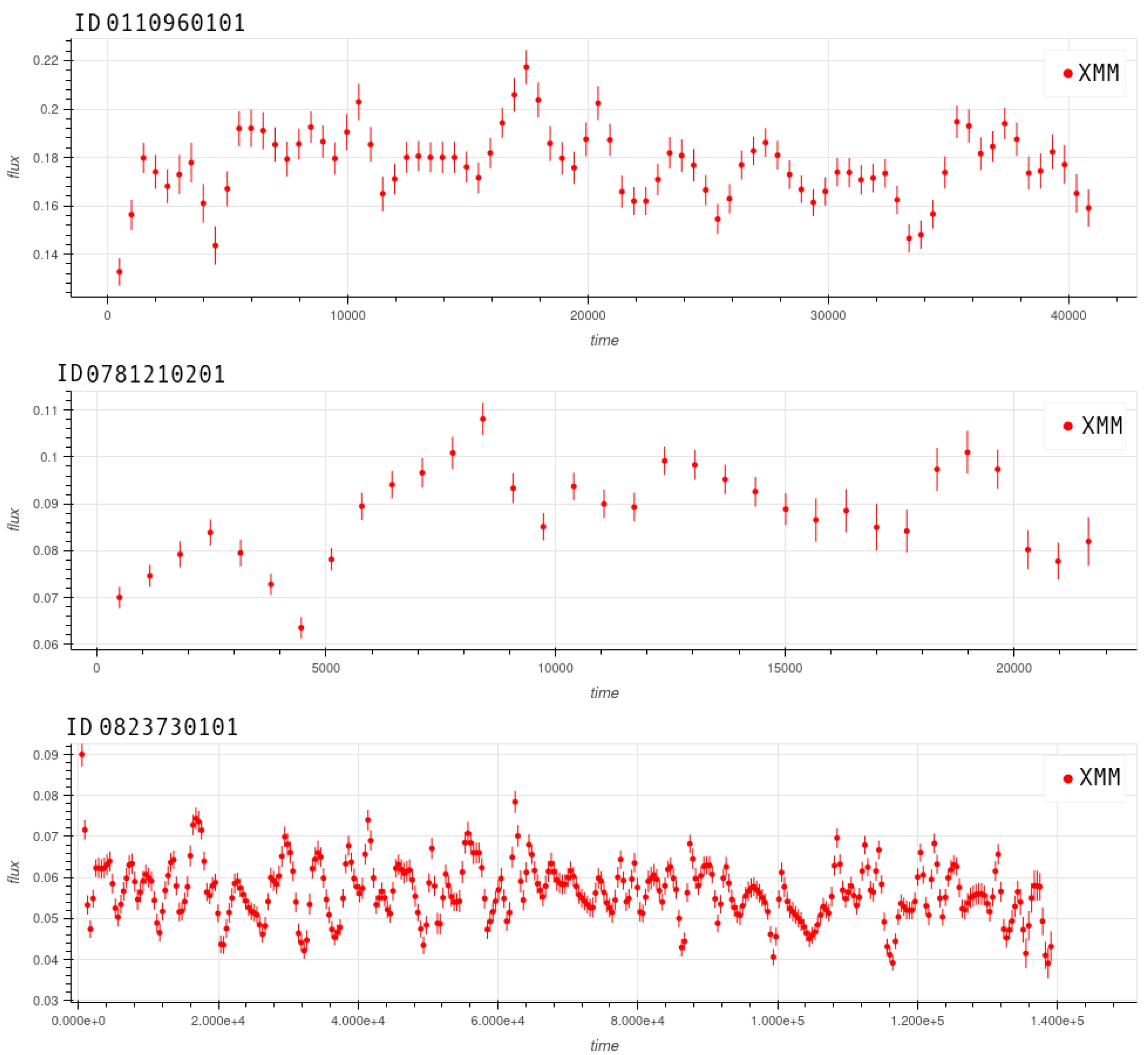

3.2. XMM-Newton

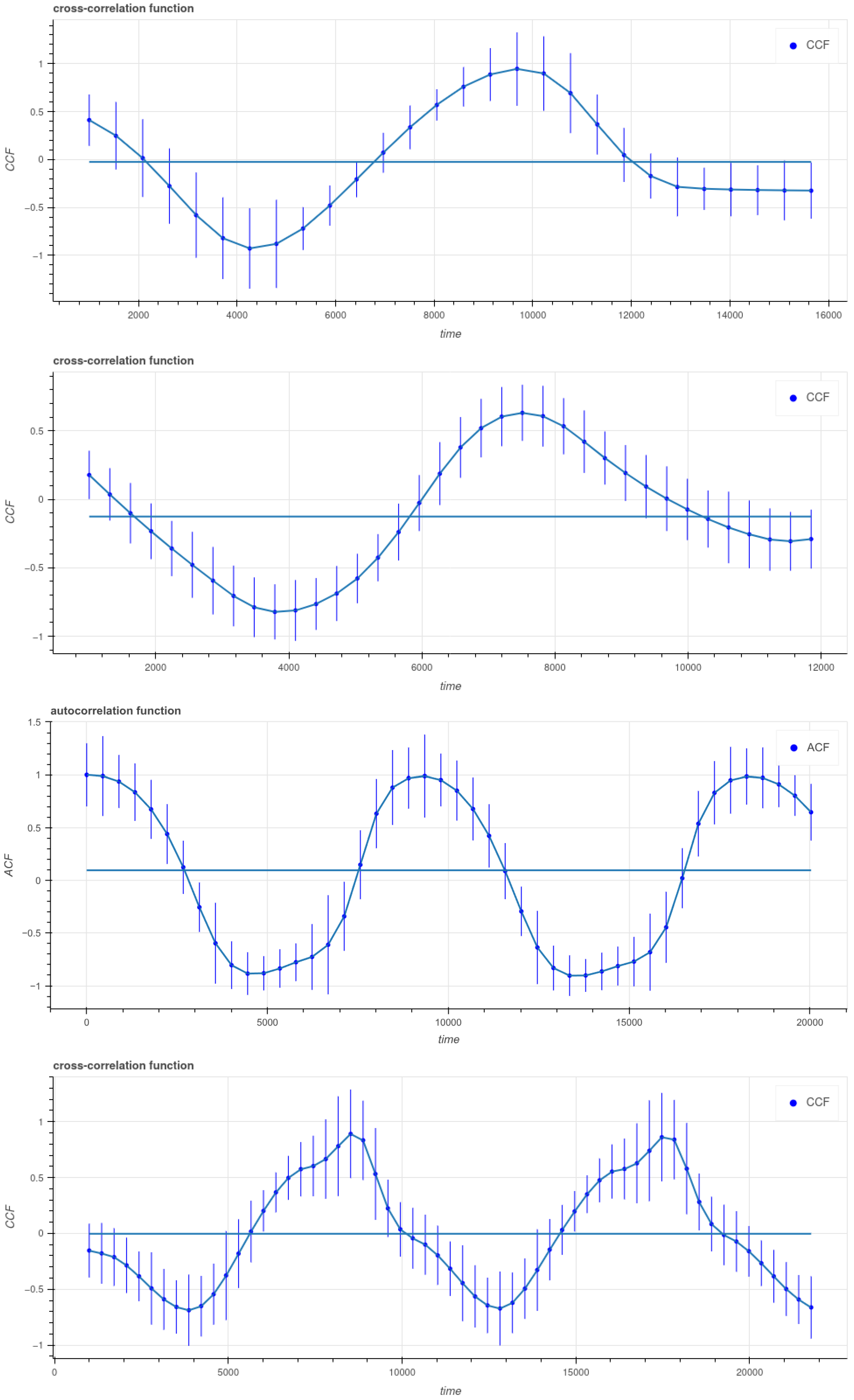

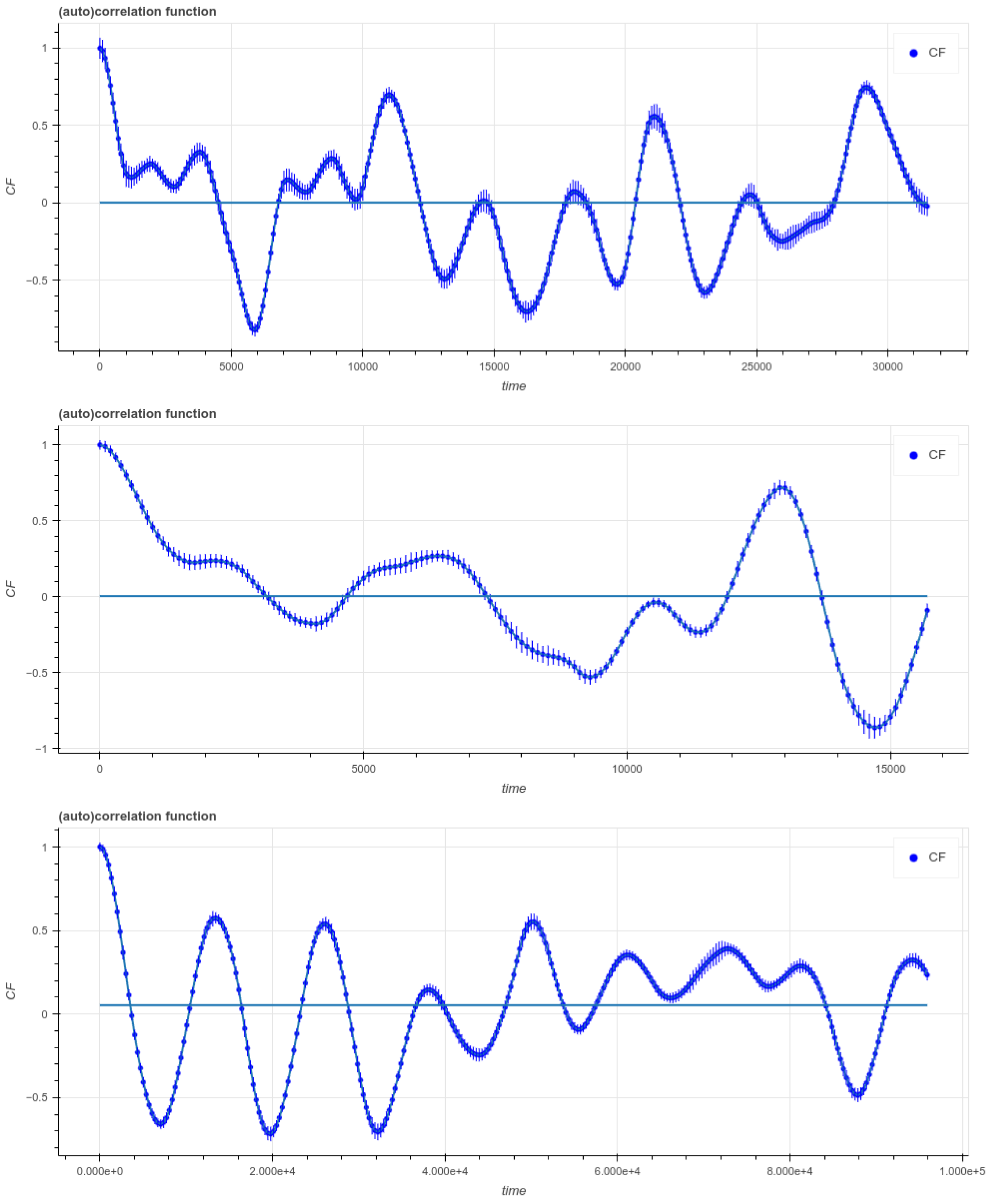

4. Auto/Cross-Correlation Functions and the Web Tool for Correlation Analysis

- Translational symmetry in the case of periodic signals: , where T is the period. The period T is the same for both and . In the case of time lag between nonperiodic signals the symmetry is absent, thus the situation with the lag can be distinguished from that of periodicity using this property of CCF;

- CCF is non commutative if a time lag is present () and it is not symmetric about the abscissa axis;

- If the signals are stochastic, it does not necessarily have a maximum at unless the signals are identical and real.

5. Time Delays in Q2237+0305 Images

5.1. Chandra

5.2. XMM-Newton

5.3. Periodicity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Acronyms

| ACF | AutoCorrelation Function |

| ACIS | Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer |

| AGN | Active Galactic Nucleus |

| AXAF | Advanced X-ray Astrophysics Facility |

| AXIS | Advanced X-ray Imaging Satellite |

| CCD | Charge-Coupled Device |

| CCF | Cross-Correlation Function |

| CIAO | Chandra Interactive Analysis of Observations |

| CMBH | Central Massive Black Hole |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| COSMOGRAIL | COSmological MOnitoring of GRAvItational Lenses |

| EPIC | European Photon Imaging Camera |

| GAIA GRAL | Gaia GRAvitational Lens systems |

| GL | Gravitational Lensing |

| GLS | Gravitational Lens System |

| HEASARC | High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center |

| HF | High Frequency |

| ISCO | Innermost Stable Circular Orbi |

| LF | Low Frequency |

| MOS | Metal Oxide Semi-conductor |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NSIE | Non-Singular Isothermal Ellipsoid |

| OGLE | Optical Gravitational Lens Experiment |

| PN | Pixelated seNsor |

| QPO | Quasi Periodic Oscillation |

| RGS | Reflection Grating Spectrometer |

| ROSAT | ROentgen SATellite |

| SAS | Scientific Astronomical Software |

| SIE | Singular Isothermal Ellipsoid |

| TDE | Tidal Disruption Event |

| XMM-Newton | X-ray Multimirror Mission Newton |

References

- Refsdal, S. The gravitational lens effect. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1964, 128, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrer, S.; Millon, M.; Sluse, D.; Shajib, A.J.; Courbin, F.; Erickson, S.; Koopmans, L.V.E.; Suyu, S.H.; Treu, T. Time-Delay Cosmography: Measuring the Hubble Constant and Other Cosmological Parameters with Strong Gravitational Lensing. Space Sci. Rev. 2024, 220, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, C.S.; Schechter, P.L. The Hubble Constant from Gravitational Lens Time Delays. In Measuring and Modeling the Universe; Freedman, W.L., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; p. 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, P.L. The Hubble Constant from Gravitational Lens Time Delays. In Gravitational Lensing Impact on Cosmology, IAU Symposium; Mellier, Y., Meylan, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; Volume 225, pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.A.; Kochanek, C.S.; Fohlmeister, J.; Wambsganss, J.; Falco, E.; Forés-Toribio, R. The Longest Delay: A 14.5 yr Campaign to Determine the Third Time Delay in the Lensing Cluster SDSS J1004+4112. Astrophys. J. 2022, 937, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulik, V.; Schild, R.; Dudinov, V.; Nuritdinov, S.; Tsvetkova, V.; Burkhonov, O.; Akhunov, T. Observational determination of the time delays in gravitational lens system Q2237+0305. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 447, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, O.; Stern, D.; Krone-Martins, A.; Delchambre, L.; Ducourant, C.; Gråe Jørgensen, U.; Dominik, M.; Burgdorf, M.; Surdej, J.; Mignard, F.; et al. Gaia GraL: Gaia DR2 gravitational lens systems. IV. Keck/LRIS spectroscopic confirmation of GRAL 113100-441959 and model prediction of time delays. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 628, A17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofek, E.O.; Maoz, D. Time-Delay Measurement of the Lensed Quasar HE 1104-1805. Astrophys. J. 2003, 594, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewes, M.; Courbin, F.; Meylan, G.; Kochanek, C.S.; Eulaers, E.; Cantale, N.; Mosquera, A.M.; Magain, P.; Van Winckel, H.; Sluse, D.; et al. COSMOGRAIL: The COSmological MOnitoring of GRAvItational Lenses. XIII. Time delays and 9-yr optical monitoring of the lensed quasar RX J1131-1231. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 556, A22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchra, J.; Gorenstein, M.; Kent, S.; Shapiro, I.; Smith, G.; Horine, E.; Perley, R. 2237+0305: A new and unusual gravitational lens. Astrophys. J. 1985, 90, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdina, L.; Tsvetkova, V.S. Detection of the rapid variability in the Q2237+0305 quasar. Adv. Astron. Space Phys. 2017, 7, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Webster, R.L.; Lewis, G.F. Weighing a galaxy bar in the lens Q2237+0305. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 295, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, O.; Surdej, J. Asymptotic solutions for the case of SIE lens models and application to the quadruply imaged quasar Q2237+0305. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 442, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambsganss, J.; Brunner, H.; Schindler, S.; Falco, E. The gravitationally lensed quasar Q2237+0305 in X-rays: ROSAT/HRI detection of the “Einstein Cross”. Astron. Astrophys. 1999, 346, L5–L8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Chartas, G.; Agol, E.; Bautz, M.W.; Garmire, G.P. Chandra Observations of QSO 2237+0305. Astrophys. J. 2003, 589, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, E.V.; Zhdanov, V.I.; Vignali, C.; Palumbo, G.G.C. Q2237+0305 in X-rays: Spectra and variability with XMM-Newton. Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 490, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Dai, X.; Kochanek, C.S.; Chartas, G.; Blackburne, J.A.; Kozłowski, S. Discovery of Energy-dependent X-Ray Microlensing in Q2237+0305. Astrophys. J. 2011, 740, L34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonehara, A.; Umemura, M.; Susa, H. Quasar Mesolensing—Direct Probe to Substructures around Galaxies. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn. 2003, 55, 1059–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonehara, A.; Umemura, M.; Susa, H. Quasar Mesolensing as a Probe of CDM Substructures; Dark Matter in Galaxies, IAU Symposium; Ryder, S., Pisano, D., Walker, M., Freeman, K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; Volume 220, p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- Zackrisson, E.; Riehm, T. Gravitational Lensing as a Probe of Cold Dark Matter Subhalos. Adv. Astron. 2010, 2010, 478910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, E.; Sliusar, V.M.; Zhdanov, V.I.; Alexandrov, A.N.; Del Popolo, A.; Surdej, J. Gravitational microlensing as a probe for dark matter clumps. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 457, 4147–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yan, J.Z.; Liu, Q.Z. Two Quasi-periodic Oscillations in ESO 113-G010. Chin. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 44, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakura, N.I.; Sunyaev, R.A. Black Holes in Binary Systems: Observational Appearances. In X- and Gamma-Ray Astronomy; IAU Symposium; Bradt, H., Giacconi, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973; Volume 55, p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen, J.M.; Petterson, J.A. The Lense-Thirring Effect and Accretion Disks around Kerr Black Holes. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1975, 195, L65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbert, P.W.; Fabian, A.C.; Rees, M.J. Spectral and variability constraints on compact sources. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1983, 205, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, B.; Misra, R. Pseudo-Newtonian Potentials to Describe the Temporal Effects on Relativistic Accretion Disks around Rotating Black Holes and Neutron Stars. Astrophys. J. 2003, 582, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remillard, R.A.; McClintock, J.E. X-Ray Properties of Black-Hole Binaries. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 44, 49–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, T.; Li, X.D.; Ray, S.; Dey, M.; Dey, J. kHz QPOs in LMXBs, relations between different frequencies and compactness of stars. New Astron. 2012, 17, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, L.; Vietri, M.; Morsink, S.M. Correlations in the Quasi-periodic Oscillation Frequencies of Low-Mass X-Ray Binaries and the Relativistic Precession Model. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1999, 524, L63–L66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, D.; Sponholz, H.; Chakrabarti, S.K. Resonance Oscillation of Radiative Shock Waves in Accretion Disks around Compact Objects. Astrophys. J. 1996, 457, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowicz, M.A.; Kluźniak, W. A precise determination of black hole spin in GRO J1655-40. Astron. Astrophys. 2001, 374, L19–L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezzolla, L.; Yoshida, S.; Zanotti, O. Oscillations of vertically integrated relativistic tori - I. Axisymmetric modes in a Schwarzschild space-time. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2003, 344, 978–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagger, M.; Pellat, R. An accretion-ejection instability in magnetized disks. Astron. Astrophys. 1999, 349, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagoner, R.V. Relativistic diskoseismology. Phys. Rep. 1999, 311, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, A.; Done, C.; Fragile, P.C. Low-frequency quasi-periodic oscillations spectra and Lense-Thirring precession. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2009, 397, L101–L105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, A.; Done, C. Modelling variability in black hole binaries: Linking simulations to observations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 419, 2369–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittman, J.D.; Bertschinger, E. The Harmonic Structure of High-Frequency Quasi-periodic Oscillations in Accreting Black Holes. Astrophys. J. 2004, 606, 1098–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.C.; Srivastava, A.K.; Wiita, P.J. Periodic Oscillations in the Intra-Day Optical Light Curves of the Blazar S5 0716+714. Astrophys. J. 2009, 690, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bartos, I.; Fragione, G.; Haiman, Z.; Kowalski, M.; Márka, S.; Perna, R.; Tagawa, H. Tidal Disruption on Stellar-mass Black Holes in Active Galactic Nuclei. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 933, L28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.W.; Kochanek, C.S.; Morgan, N.D.; Falco, E.E. The Quasar Accretion Disk Size-Black Hole Mass Relation. Astrophys. J. 2010, 712, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cackett, E.M.; Bentz, M.C.; Kara, E. Reverberation mapping of active galactic nuclei: From X-ray corona to dusty torus. iScience 2021, 24, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lightman, A.P.; Press, W.H.; Price, R.H.; Teukolsky, S.A. Problem Book in Relativity and Gravitation; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sluse, D.; Schmidt, R.; Courbin, F.; Hutsemékers, D.; Meylan, G.; Eigenbrod, A.; Anguita, T.; Agol, E.; Wambsganss, J. Zooming into the broad line region of the gravitationally lensed quasar QSO 2237 + 0305 ≡ the Einstein Cross. III. Determination of the size and structure of the C iv and C iii] emitting regions using microlensing. Astron. Astrophys. 2011, 528, A100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agol, E.; Jones, B.; Blaes, O. Keck Mid-Infrared Imaging of QSO 2237+0305. Astrophys. J. 2000, 545, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, C.S. Quantitative Interpretation of Quasar Microlensing Light Curves. Astrophys. J. 2004, 605, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, D.; Blackburne, J.A.; Rappaport, S.; Schechter, P.L. X-Ray and Optical Flux Ratio Anomalies in Quadruply Lensed Quasars. I. Zooming in on Quasar Emission Regions. Astrophys. J. 2007, 661, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assef, R.J.; Denney, K.D.; Kochanek, C.S.; Peterson, B.M.; Kozłowski, S.; Ageorges, N.; Barrows, R.S.; Buschkamp, P.; Dietrich, M.; Falco, E.; et al. Black Hole Mass Estimates Based on C IV are Consistent with Those Based on the Balmer Lines. Astrophys. J. 2011, 742, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla, E.; Jiménez-vicente, J.; Muñoz, J.A.; Mediavilla, T. Resolving the Innermost Region of the Accretion Disk of the Lensed Quasar Q2237+0305 through Gravitational Microlensing. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2015, 814, L26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla, E.; Jimenez-Vicente, J.; Muñoz, J.A.; Mediavilla, T.; Ariza, O. Statistics of Microlensing Caustic Crossings in Q 2237+0305: Peculiar Velocity of the Lens Galaxy and Accretion Disk Size. Astrophys. J. 2015, 798, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goicoechea, L.J.; Alcalde, D.; Mediavilla, E.; Muñoz, J.A. Determination of the properties of the central engine in microlensed QSOs. Astron. Astrophys. 2003, 397, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutsemékers, D.; Sluse, D. Geometry and kinematics of the broad emission line region in the lensed quasar Q2237+0305. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 654, A155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C. The Advanced Imaging X-ray Satellite (AXIS). In AAS/High Energy Astrophysics Division; American Astronomical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Volume 20, p. 306.02. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C.S.; Kara, E.A.; Mushotzky, R.F.; Ptak, A.; Koss, M.J.; Williams, B.J.; Allen, S.W.; Bauer, F.E.; Bautz, M.; Bogadhee, A.; et al. Overview of the advanced x-ray imaging satellite (AXIS). In UV, X-Ray, and Gamma-Ray Space Instrumentation for Astronomy XXIII; Conference Series; Siegmund, O.H., Hoadley, K., Eds.; Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE): Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12678, p. 126781E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, M.; Aftab, N.; Allen, S.W.; Amato, R.; An, H.; Andreoni, I.; Anguita, T.; Arcodia, R.; Ayres, T.; Bachetti, M.; et al. The Advanced X-ray Imaging Satellite Community Science Book. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.00253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millon, M.; Courbin, F.; Bonvin, V.; Paic, E.; Meylan, G.; Tewes, M.; Sluse, D.; Magain, P.; Chan, J.H.H.; Galan, A.; et al. COSMOGRAIL. XIX. Time delays in 18 strongly lensed quasars from 15 years of optical monitoring. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 640, A105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.R.; Narasimha, D. Determination of time delay from the gravitational lens B1422+231. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2001, 326, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalyapin, V.N.; Goicoechea, L.J.; Dyrland, K.; Dahle, H. Andromeda’s Parachute: Time Delays and Hubble Constant. Astrophys. J. 2023, 955, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornachione, M.A.; Morgan, C.W.; Millon, M.; Bentz, M.C.; Courbin, F.; Bonvin, V.; Falco, E.E. A Microlensing Accretion Disk Size Measurement in the Lensed Quasar WFI 2026-4536. Astrophys. J. 2020, 895, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, V.; Chan, J.H.H.; Millon, M.; Rojas, K.; Courbin, F.; Chen, G.C.F.; Fassnacht, C.D.; Paic, E.; Tewes, M.; Chao, D.C.Y.; et al. COSMOGRAIL. XVII. Time delays for the quadruply imaged quasar PG 1115+080. Astron. Astrophys. 2018, 616, A183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.T.; Rusin, D.; Fassnacht, C.D.; Blandford, R.D.; Pearson, T.J.; Readhead, A.C.S.; Jackson, N.; Browne, I.W.A.; Marlow, D.R.; Wilkinson, P.N.; et al. CLASS B1152+199 and B1359+154: Two New Gravitational Lens Systems Discovered in the Cosmic Lens All-Sky Survey. Astrophys. J. 1999, 117, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S. Modelling the 10-image lensed system B1933+503. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 301, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Images | Time Delay, Hours | Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A B | 2.0 | Bar accounted | [12] |

| 2.6 ± 0.7 | SIE lens | [13] | |

| 2.5 ± 0.5 | NSIE + | [13] | |

| A C | −16.2 | Bar accounted | [12] |

| −18.0 ± 0.7 | SIE lens | [13] | |

| −18.0 ± 0.6 | NSIE + | [13] | |

| A D | −4.9 | Bar accounted | [12] |

| −5.4 ± 0.4 | SIE lens | [13] | |

| −5.4 ± 0.4 | NSIE + | [13] | |

| B C | −18.3 | Bar accounted | [12] |

| −20.6 | SIE lens | [13] | |

| −20.5 | NSIE + | [13] | |

| B D | −6.9 | Bar accounted | [12] |

| −8.0 | SIE lens | [13] | |

| −7.9 | NSIE + | [13] | |

| C D | 11.3 | Bar accounted | [12] |

| 12.6 ± 0.7 | SIE lens | [13] | |

| 12.6 ± 0.6 | NSIE + | [13] |

| obs. ID | obs. | obs. Time, | Total ACIS | Variance/σ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | ks | Counts * | Image A | Image B | Image C | Image D | |

| 431 | 2000-09-06 | 30.7 | 3145 | 1.17 | 1.09 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| 1632 | 2001-12-08 | 9.66 | 864 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 1.07 |

| 6831 | 2006-01-09 | 7.44 | 460 | 0.41 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.88 |

| 6832 | 2006-05-01 | 8.13 | 500 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 1.05 | 0.59 |

| 6833 | 2006-05-27 | 8.14 | 264 | 0.48 | 1.05 | 0.71 | 1.07 |

| 6834 | 2006-06-25 | 8.13 | 636 | 0.5 | 0.85 | 1.02 | 0.86 |

| 6835 | 2006-07-21 | 8.05 | 594 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.65 | 0.71 |

| 6836 | 2006-08-17 | 8.12 | 325 | 1.03 | 1.36 | 0.95 | 1.11 |

| 6837 | 2006-09-16 | 8.14 | 336 | 0.79 | 1.07 | 0.87 | 1.35 |

| 6838 | 2006-10-09 | 8.18 | 303 | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.97 | 0.91 |

| 6839 | 2006-11-29 | 8.06 | 1075 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| 6840 | 2007-01-14 | 8.17 | 897 | 0.63 | 0.99 | 0.74 | 0.87 |

| 11534 | 2009-12-31 | 29.14 | 3862 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 1.02 |

| 11535 | 2010-04-25 | 30.14 | 960 | 1.24 | 1.15 | 0.91 | 1.01 |

| 11536 | 2010-06-27 | 28.56 | 744 | 1.64 | 1.16 | 0.95 | 0.79 |

| 11537 | 2010-08-07 | 30.06 | 462 | 1.01 | 1.26 | 0.99 | 1.18 |

| 11538 | 2010-10-02 | 30.06 | 1320 | 0.83 | 1.11 | 0.87 | 0.74 |

| 11539 | 2010-11-23 | 10.07 | 208 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.66 |

| 13195 | 2010-11-26 | 10.07 | 156 | 0.63 | 1.47 | 1.21 | 0.99 |

| 13191 | 2010-11-27 | 10.07 | 232 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 0.71 | 0.8 |

| 12831 | 2011-05-14 | 30.01 | 4686 | 1.1 | 1.14 | 1.25 | 1.18 |

| 12832 | 2011-12-27 | 30.51 | 726 | 0.94 | 1.0 | 1.29 | 1.23 |

| 13960 | 2012-01-09 | 30.07 | 704 | 0.91 | 1.26 | 0.89 | 0.96 |

| 13961 | 2012-08-02 | 29.94 | 1696 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 1.25 |

| 14513 | 2012-12-26 | 29.31 | 1674 | 1.08 | 0.98 | 1.17 | - |

| 14514 | 2013-01-05 | 30.06 | 1532 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| 16316 | 2013-08-26 | 10.07 | 269 | 1.38 | 1.12 | 0.88 | 1.06 |

| 16317 | 2013-08-28 | 10.07 | 247 | 1.12 | 0.93 | 1.18 | 0.57 |

| 14515 | 2013-08-31 | 9.97 | 336 | 0.42 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 1.39 |

| 14516 | 2013-10-01 | 30.06 | 608 | 1.32 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 1.11 |

| 14517 | 2014-05-14 | 30.06 | 1260 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 1.22 | 1.17 |

| 14518 | 2014-06-08 | 29.98 | 1280 | 1.44 | 1.01 | 1.22 | 1.55 |

| 18804 | 2016-04-24 | 30.06 | 1504 | 1.23 | 0.99 | 1.19 | 1.24 |

| 19638 | 2016-12-22 | 34.15 | 648 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

| 19639 | 2017-01-04 | 33.72 | 540 | 1.14 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 1.02 |

| 19640 | 2017-12-20 | 35.06 | 740 | 1.21 | 1.33 | 1.26 | 0.95 |

| 19641 | 2018-01-14 | 35.06 | 684 | 1.08 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.98 |

| 19642 | 2018-12-27 | 33.06 | 684 | 0.89 | 1.25 | 1.32 | 1.01 |

| 19643 | 2019-01-07 | 10.06 | 276 | 0.67 | 1.1 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| 22042 | 2019-01-13 | 25.06 | 980 | 0.95 | 1.21 | 0.70 | 0.91 |

| obs. ID | obs. Date | obs. Time, ks | Total EPIC Counts * | Variance/σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0110960101 | 2002-05-28 | 48.9 | 10988 | 2.47 |

| 0781210201 | 2016-11-26 | 24.9 | 4002 | 3.15 |

| 0823730101 | 2018-05-19 | 141.6 | 10947 | 3.78 |

| obs. ID | Time Delays, Hours | Periods, Hours | Mean Period, | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | DA | DB | A | B | C | D | Hours | |

| 431 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 11535 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | - | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1.97 ± 0.19 |

| 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | ||||||

| 5.1 ± 0.3 | ||||||||

| 11536 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 11537 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 12831 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | |

| 4.1 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | ||||||

| 12832 | - | - | 0.6 ± 0.2 | - | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.4 |

| 2.2 ± 0.6 | ||||||||

| 3.9 ± 0.5 | ||||||||

| 6.0 ± 0.4 | ||||||||

| 13191/5 | - | - | - | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | - | ||

| 14516 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 14517 | - | 1.4 ± 0.3 | - | 0.8 | - | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| - | 2.8 ± 0.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| - | 4.2 ± 0.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 14518 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | |

| 4.2 ± 0.3 | ||||||||

| 18804 | - | 1.3 ± 0.3 | - | 1.4 ± 0.3 | - | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| - | 2.2 ± 0.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| - | 6.0 ± 0.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 19638 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 19639 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| 4.2 ± 0.9 | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| - | - | >6.3 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 19640 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 19642 | - | - | 5.6 ± 0.5 | |||||

| Mean | 4.5 ± 0.2 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| obs. ID | Exposure, ks | Time Delays, Hours | Interpretation | Model/ Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0110960101 | 48.9 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | AB | SIE/NSIE [13]/Chandra (this work, [15]) |

| 6.0 ± 0.3 | DA or DB | SIE/NSIE [13] (DA); Bar accounted [12]/this work (DB) | ||

| 8.1 ± 0.3 | DB | SIE/NSIE [13] | ||

| 0781210201 | 24.9 | periodicity? | - | |

| 2.9 ± 0.3 | AB | SIE/NSIE [13]/Chandra (this work, [15]) | ||

| 4.6 ± 0.3 | DA | Chandra (this work)/[11]/Bar accounted [12] | ||

| 0823730101 | 141.6 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | AB? | [11] |

| 6.9 ± 0.6 | DA | Bar accounted [12], Chandra (this work) | ||

| AC or BC | Bar accounted [12], SIE/NSIE [13] | |||

| 25.0 ± 1.7 | periodicity? | - | ||

| 29.7 ± 0.8 | periodicity? | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fedorova, E.; Del Popolo, A. Specifying the Measures of the Time Delays in Gravitationally Lensed Quasar Q2237+0305 Images. Symmetry 2026, 18, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010162

Fedorova E, Del Popolo A. Specifying the Measures of the Time Delays in Gravitationally Lensed Quasar Q2237+0305 Images. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010162

Chicago/Turabian StyleFedorova, Elena, and Antonino Del Popolo. 2026. "Specifying the Measures of the Time Delays in Gravitationally Lensed Quasar Q2237+0305 Images" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010162

APA StyleFedorova, E., & Del Popolo, A. (2026). Specifying the Measures of the Time Delays in Gravitationally Lensed Quasar Q2237+0305 Images. Symmetry, 18(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010162