Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm with Errors and Variable Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm for Nonexpansive Mappings in Symmetric Banach Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

- (i)

- For and , exists;

- (ii)

- If, in addition, the dual space of E has the KK-property, then the weak limit set of , denoted by is a singleton.

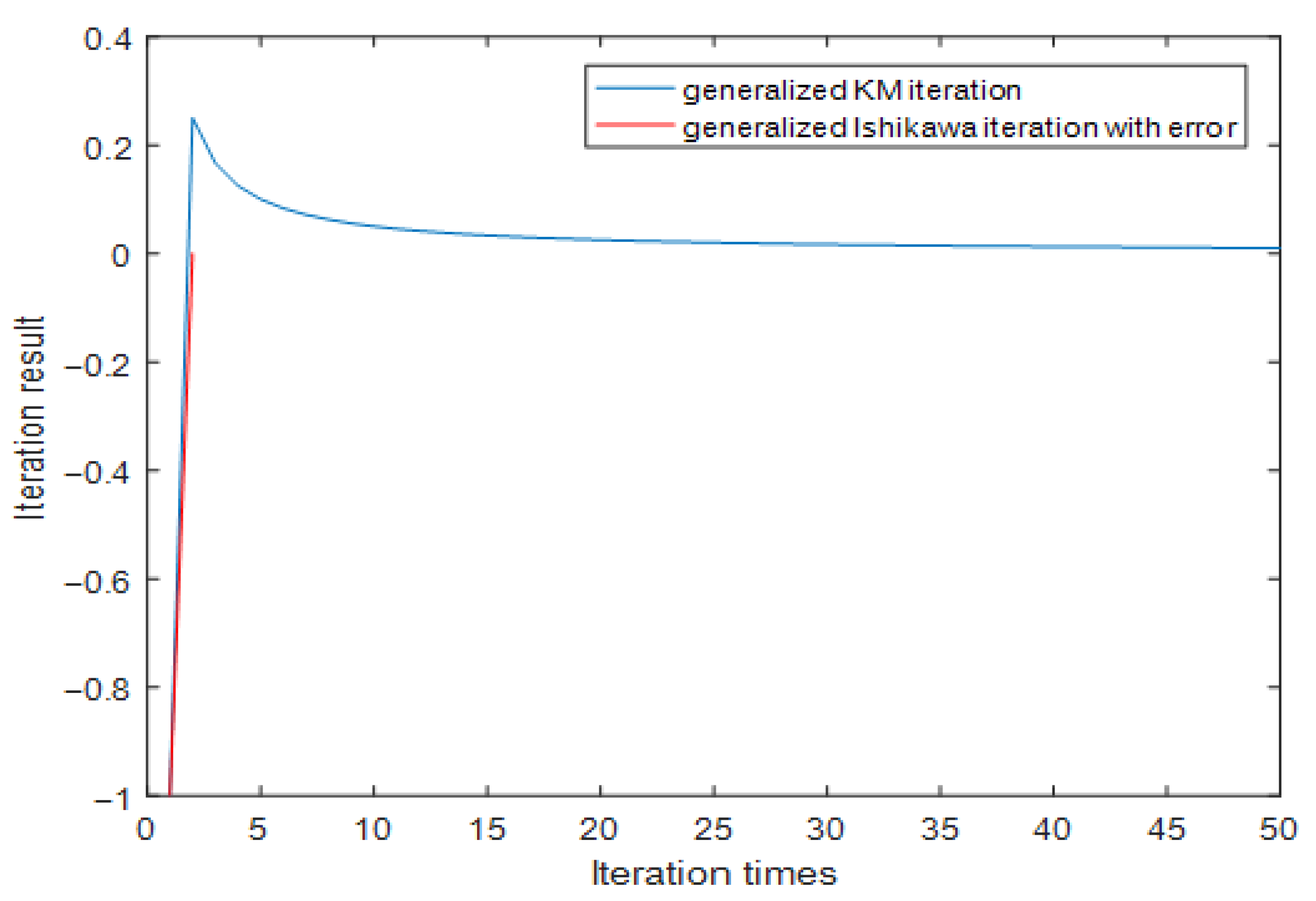

3. On the Convergence of the Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm with Errors Term and Its Applications

3.1. Weak Convergence of Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm with Errors

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- , ;

- (iii)

- , ;

- (iv)

- .

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- , ;

- (iii)

- .

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- .

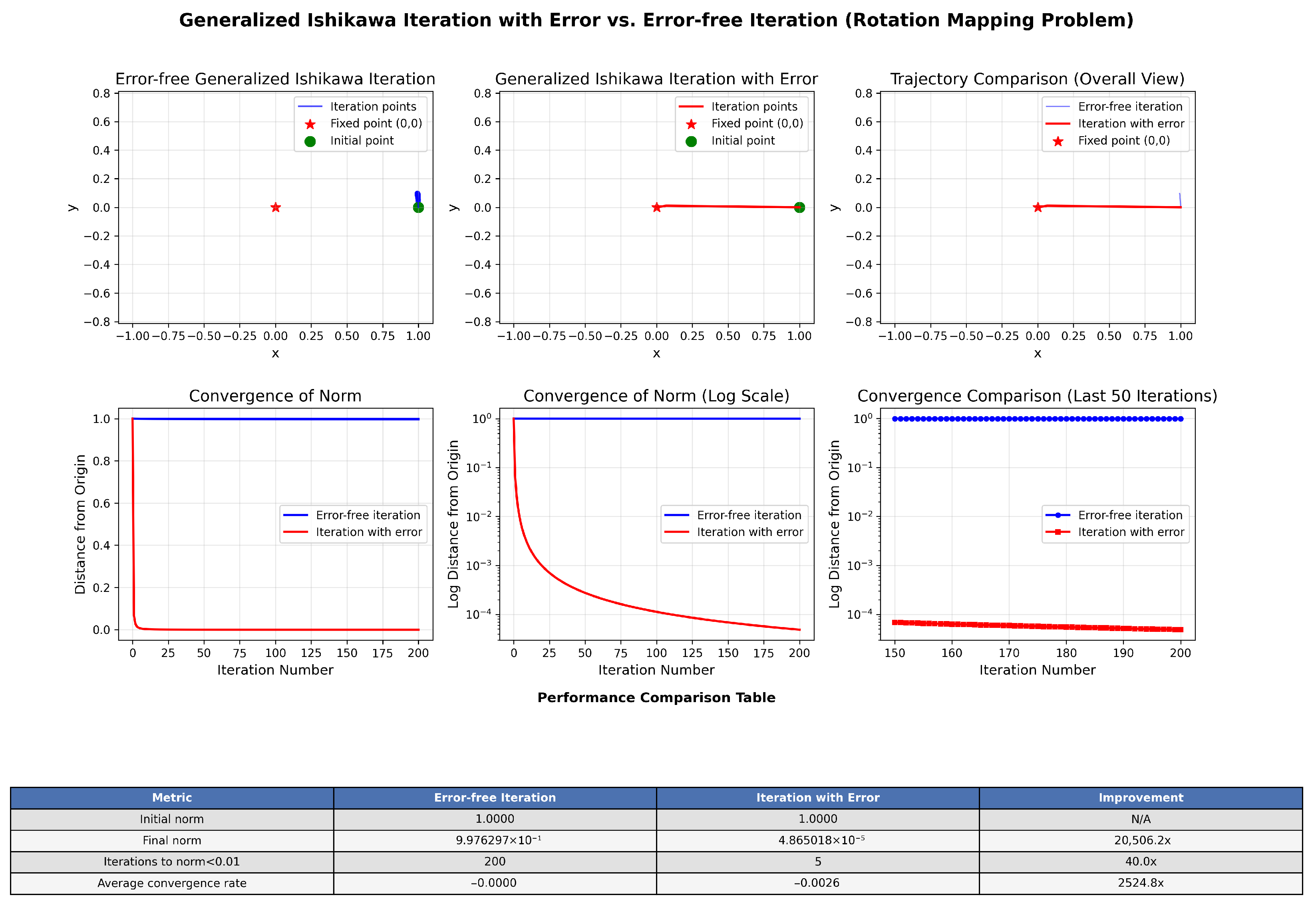

3.2. Application of Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm with Errors

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- , ;

- (iii)

- , ;

- (iv)

- .

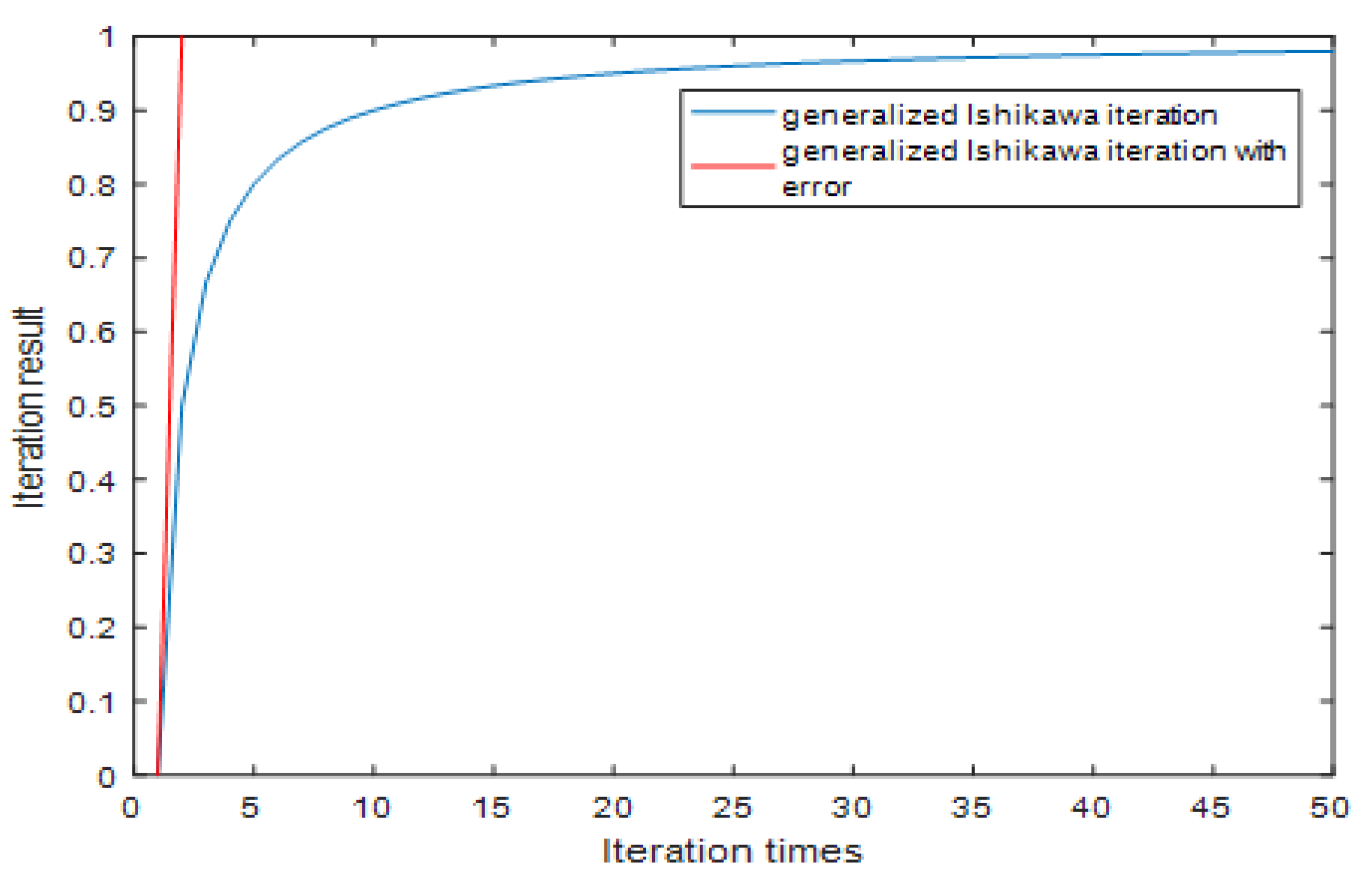

4. Convergence of Variable Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm and Its Application

4.1. Weak Convergence of Variable Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- , ;

- (iv)

- , , wherethen the sequence generated by the iteration (23) converges weakly to the fixed point of T.

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- , ;

- (iv)

- , , wherethen the sequence generated by the iteration (23) converges weakly to the fixed point of T.

4.2. Application of Variable Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Browder, F.E. Nonexpansive nonlinear operators in a banach space. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1965, 54, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, W.A. A fixed point theorem for mappings which do not increase distances. Am. Math. Mon. 1965, 72, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnosel’skiı, M.A. Two remarks on the method of successive approximations. Uspekhi Mat. Nauk. 1965, 10, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, W.R. Mean value methods in iteration. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1953, 4, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, S. Weak convergence theorems for nonexpansive mappings in banach spaces. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1979, 67, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzow, C.; Shehu, Y. Generalized krasnoselskii–mann-type iterations for nonexpansive mappings in hilbert spaces. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2017, 67, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Guo, K.; Wang, T. Generalized krasnoselskii–mann-type iteration for nonexpansive mappings in banach spaces. J. Oper. Res. Soc. China 2021, 9, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C. Generalized KM Iterative Algorithm and Its Applications in Zero Point Problems and Split Feasibility Problems. Master’s Thesis, West China Normal University, Nanchong, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, S. Fixed points by a new iteration method. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1974, 44, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.K.; Xu, H.K. Approximating fixed points of non-expansive mappings by the ishikawa iteration process. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1993, 178, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Guo, K.; Zhao, S.L. A class of generalized ishikawa iterations in hilbert spaces and its application to variational inequalities. J. Xihua Norm. Univ. Natural Sci. Ed. 2018, 33, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, A. Iterative scheme generating method beyond Ishikawa iterative method. Math. Ann. 2024, 391, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, A.; Alam, H.K.; Sajid, M.; Rohen, Y.; Singh, S.S. Fibonacci-Ishikawa iterative method in modular spaces for asymptotically non-expansive monotonic mathematical operators. J. Inequalities Appl. 2025, 2025, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragadeeswarar, V.; Gopi, R.; Park, C.; Lee, J.R. Convergence of Fixed Points for Relatively Nonexpansive Mappings via Ishikawa Iteration. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2025, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Song, X.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y. Distributed Ishikawa algorithms for seeking the fixed points of multi-agent global operators over time-varying communication graphs. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2025, 457, 116250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, F.E. Convergence theorems for sequences of nonlinear operators in banach spaces. Math. Z. 1967, 100, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Xu, H.K. Robustness of mann’s algorithm for nonexpansive mappings. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 327, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinet, B. Regularisation d’inequations variationelles par approximations successives. Rev. Fr. D’Informatique Rech. Oper. 1970, 4, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, G.; Martlnmarquez, V.; Wang, F.; Xu, H.K. Forward-backward splitting methods for accretive operators in banach spaces. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012, 2012, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censor, Y.; Elfving, T. A multiprojection algorithm using Bregman projections in a product space. Numer. Algorithms 1994, 8, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. Iterative oblique projection onto convex sets and the split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2002, 18, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. A unified treatment of some iterative algorithms in signal processing and image reconstruction. Inverse Probl. 2003, 20, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.K. A variable Krasnosel’skii–Mann algorithm and the multiple-set split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2006, 22, 2021–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, Q. Several solution methods for the split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2005, 21, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, W. Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm with Errors and Variable Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm for Nonexpansive Mappings in Symmetric Banach Spaces. Symmetry 2026, 18, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010125

Yu L, Zhu Y, Zhao W. Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm with Errors and Variable Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm for Nonexpansive Mappings in Symmetric Banach Spaces. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010125

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Liangjuan, Yuhan Zhu, and Wenying Zhao. 2026. "Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm with Errors and Variable Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm for Nonexpansive Mappings in Symmetric Banach Spaces" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010125

APA StyleYu, L., Zhu, Y., & Zhao, W. (2026). Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm with Errors and Variable Generalized Ishikawa Iterative Algorithm for Nonexpansive Mappings in Symmetric Banach Spaces. Symmetry, 18(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010125