Two-Degree-of-Freedom Digital RST Controller Synthesis for Robust String-Stable Vehicle Platoons

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Related Works

1.3. Contributions

- We propose a fully decentralized two-layer platoon-control architecture that integrates modular velocity-reference generation with a two-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) RST controller.

- We design a discrete-time two-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) digital RST controller tailored to this symmetrical structure. Using pole placement and sensitivity shaping, the controller enables independent tuning of tracking and disturbance rejection while remaining lightweight for embedded implementation.

- We develop a stability analysis showing that the proposed architecture ensures internal stability and satisfies string stability under the constant time-headway policy.

- We provide a comparative analysis against another controller proposed in the literature. The proposed method achieves better tracking, faster recovery, and smoother actuation, demonstrating clear performance advantages.

1.4. Organization

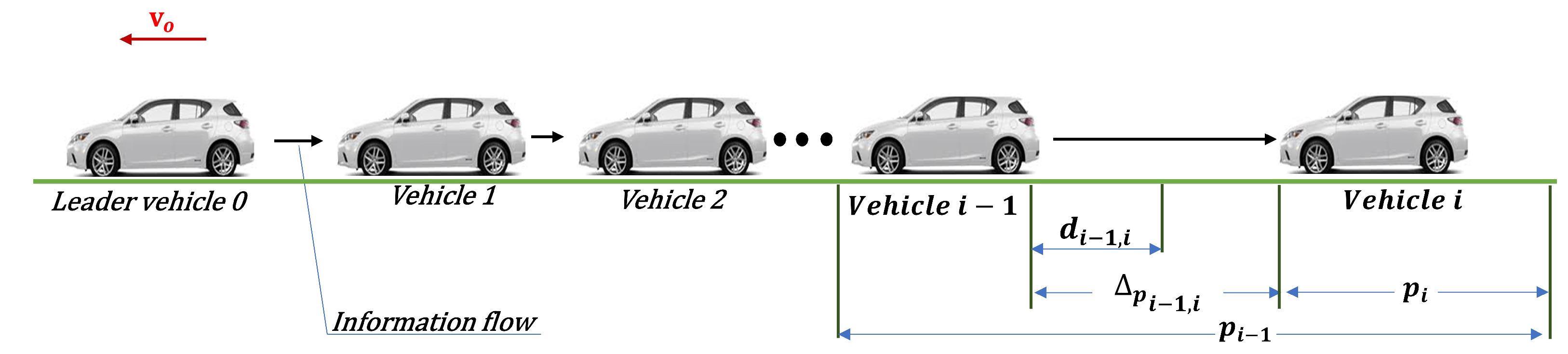

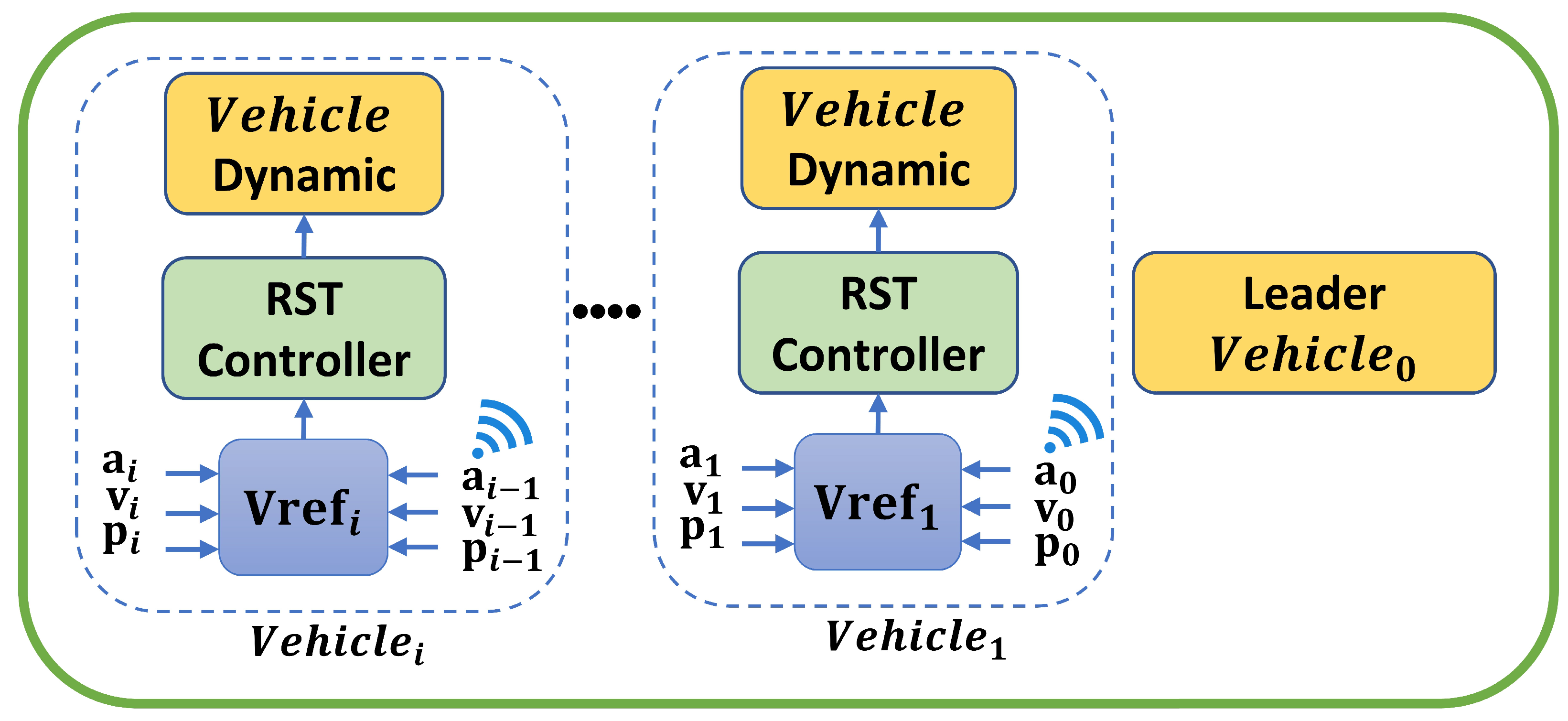

2. System Model

- An Upper-Layer Velocity Reference Generation: This layer computes a desired velocity reference for each follower vehicle based on relative measurements of position, velocity, and acceleration with respect to its immediate predecessor. This design decouples the spacing policy from the underlying tracking control, resulting in a modular and flexible architecture that enables independent tuning of both spacing and velocity tracking performance.

- A Lower-Layer RST-Based Tracking and Regulation Control: A discrete-time, two-degree-of-freedom RST controller is implemented to track the velocity reference. This structure allows for independent tuning of regulation and tracking behavior by explicitly shaping the sensitivity functions. Proper shaping improves disturbance rejection, enhances robustness to modeling uncertainties and actuator lag, and ensures a favorable transient response throughout the platoon.

3. Velocity Reference Generation

4. RST Digital Controller Design

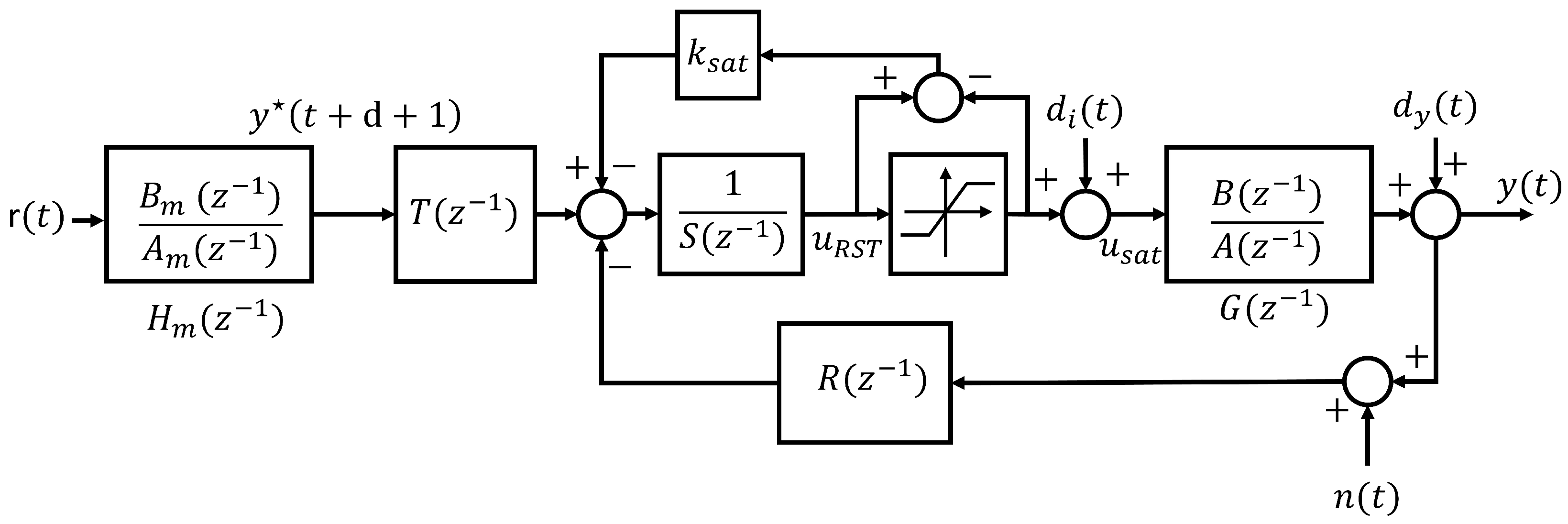

4.1. RST Controller Architecture

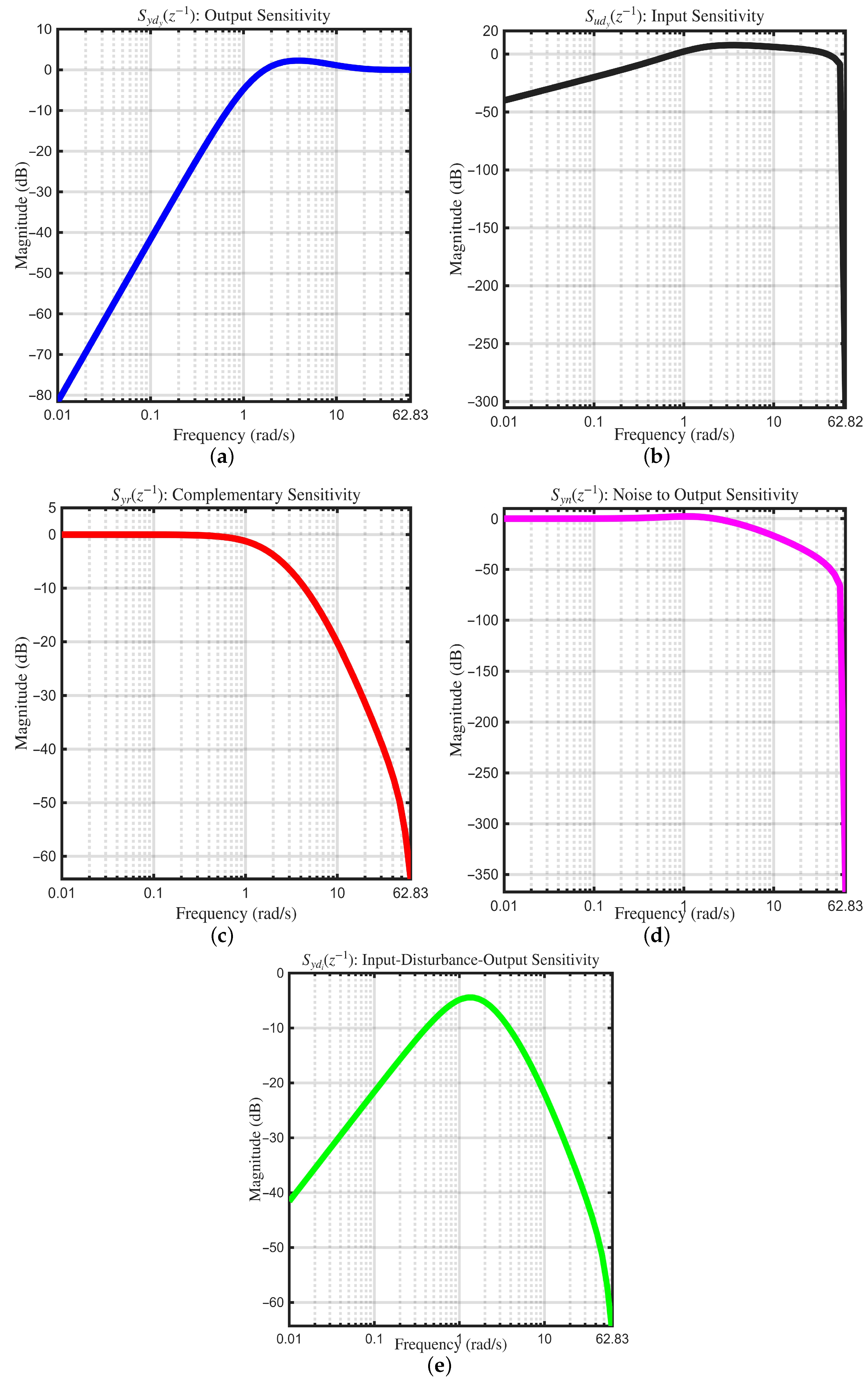

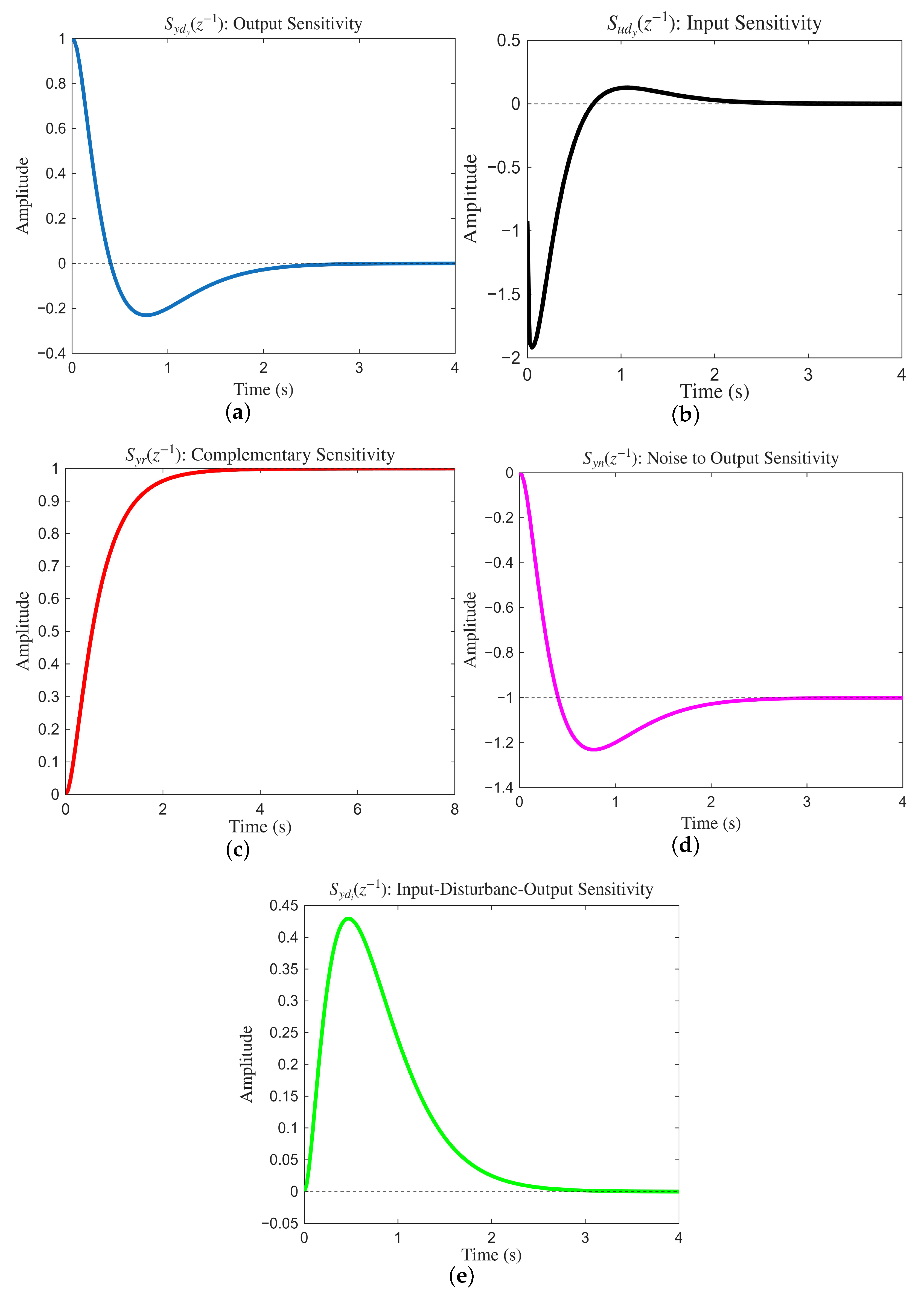

4.2. The Sensitivity Functions

4.3. Design Procedure for Pole Placement and Sensitivity Shaping

- Check: Evaluate the sensitivity functions and , and verify whether they are consistent with their target robustness templates.

- If yes→ Proceed to Finalization.

- If no→ Identify the specific violation and apply the following correction rules:

- -

- Peak in near the desired bandwidth → add complex zeros to .

- -

- too large at high frequencies → add real high-frequency poles to .

- -

- Large at frequencies where the plant gain is low → add complex zeros to .

5. RST Controller Design for Vehicle Platooning

- Output Sensitivity Function :to ensure adequate stability margins and robustness.

- Input Sensitivity Function :to maintain control accelerations within for passenger comfort.

- Complementary Sensitivity Function :

6. Stability Analysis

6.1. Internal Stability Analysis

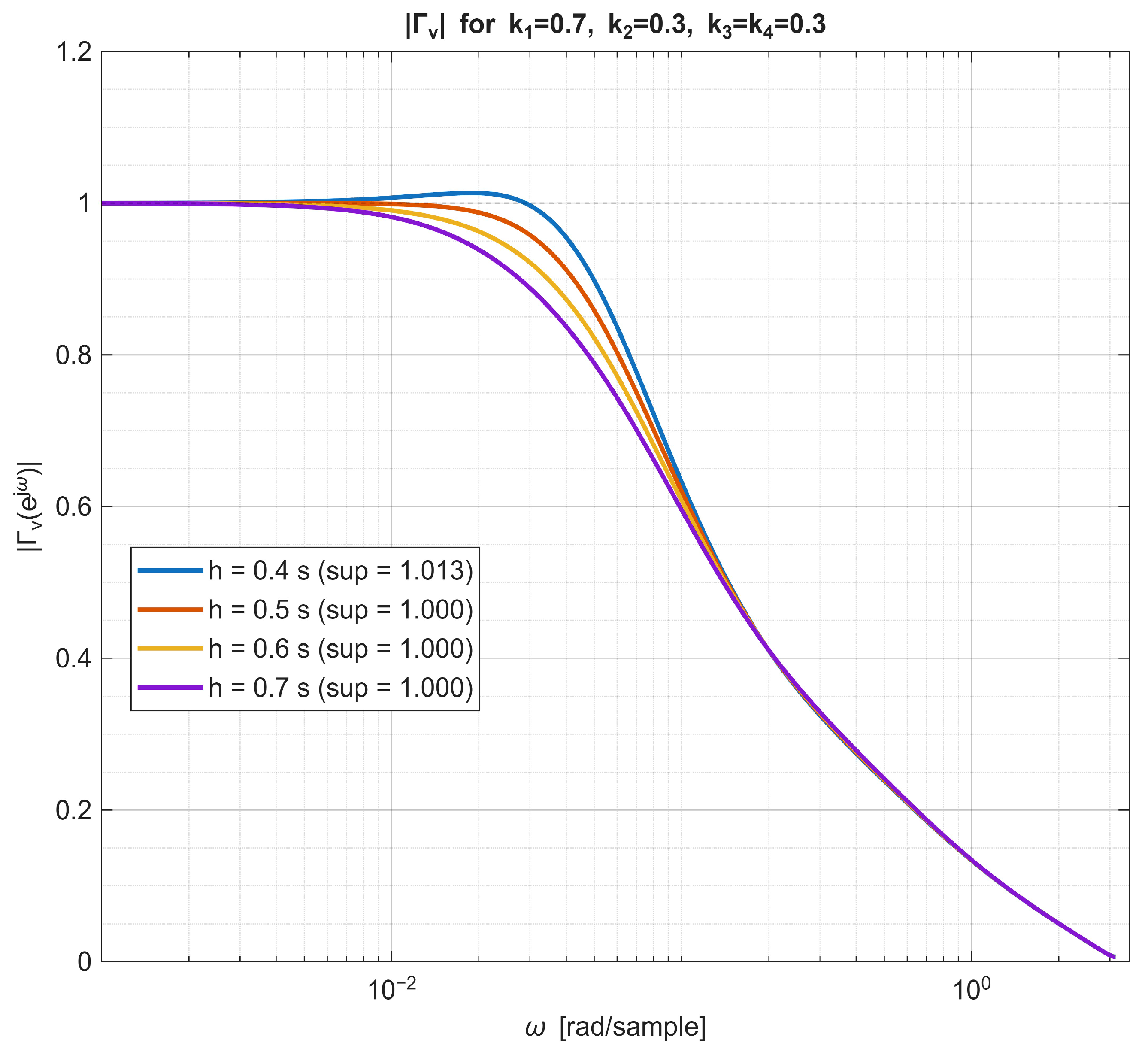

6.2. String-Stability Analysis

- (i)

- exists;

- (ii)

- for all .

7. Numerical Results

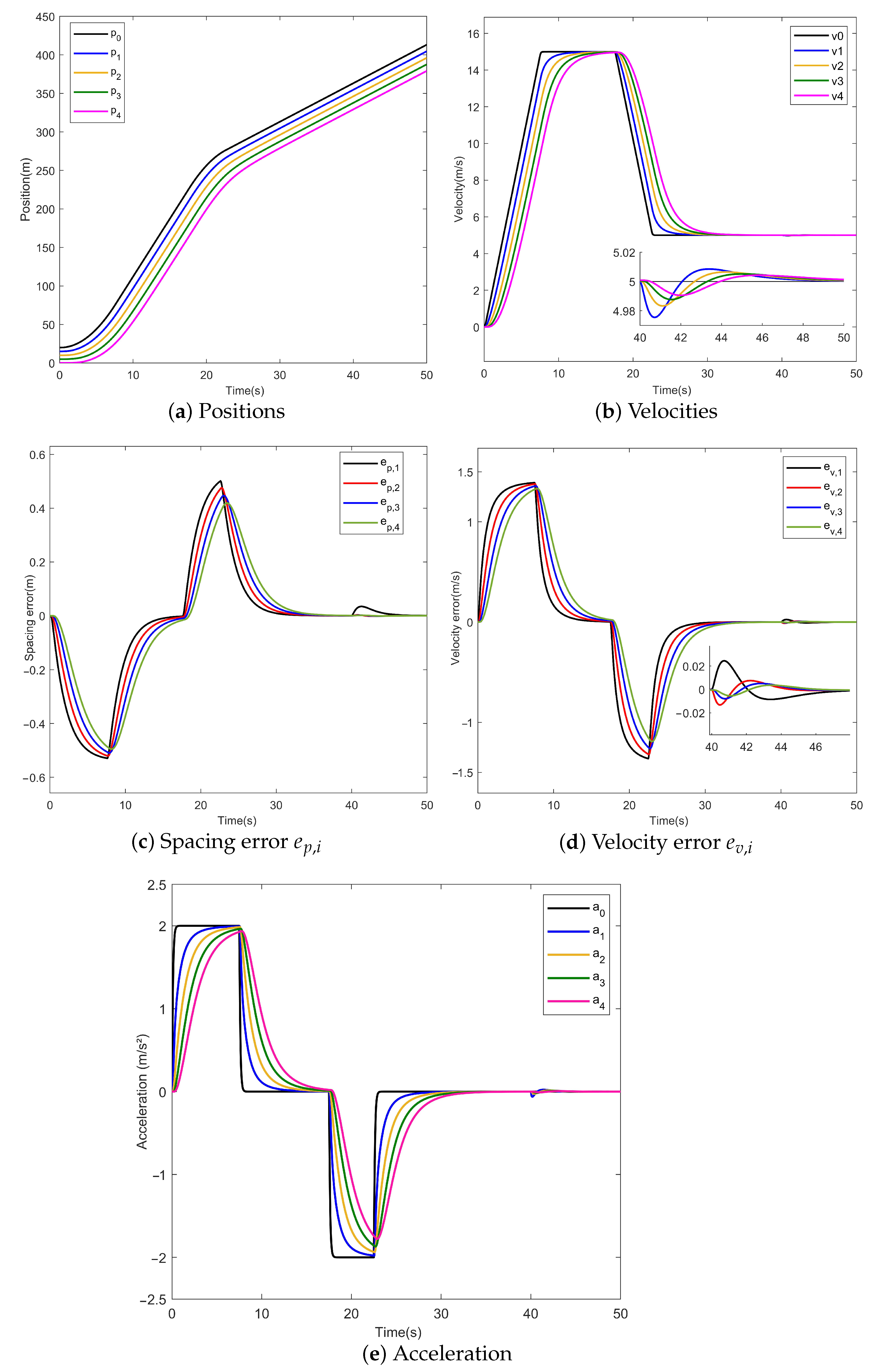

7.1. Simulation Setting

7.2. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2DOF | Two-Degree-of-Freedom |

| ACC | Adaptive Cruise Control |

| AW | Anti-Windup |

| BD | Bidirectional (information topology) |

| BIBO | Bounded-Input Bounded-Output |

| CACC | Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control |

| CAV | Connected and Automated Vehicle |

| CD | Constant Distance (spacing policy) |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CTH | Constant Time Headway |

| DMPC | Distributed Model Predictive Control |

| DMRAC | Distributed Model Reference Adaptive Control |

| HOV | High-Occupancy Vehicle |

| H-infinity (robust control) | |

| ITF | Information Flow Topology |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation Systems |

| L2 | (energy) norm |

| LQR | Linear Quadratic Regulator |

| LTI | Linear Time-Invariant |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MPF | Multi-Predecessor-Following (topology) |

| NLD | Nonlinear Distance (spacing policy) |

| PD | Proportional-Derivative |

| PF | Predecessor-Following (topology) |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PI | Proportional-Integral |

| PLF | Predecessor-Leader-Following (topology) |

| SISO | Single-Input Single-Output |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| Ts | Sampling Period |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything |

| ZOH | Zero-Order Hold |

References

- Elassy, M.; Al-Hattab, M.; Takruri, M.; Badawi, S. Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities. Transp. Eng. 2024, 16, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladimeji, D.; Gupta, K.; Kose, N.A.; Gundogan, K.; Ge, L.; Liang, F. Smart transportation: An overview of technologies and applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bian, Y.; Shladover, S.E.; Wu, G.; Li, S.E.; Barth, M.J. A survey on cooperative longitudinal motion control of multiple connected and automated vehicles. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2019, 12, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.E.; Zheng, Y.; Li, K.; Wu, Y.; Hedrick, J.K.; Gao, F.; Zhang, H. Dynamical modeling and distributed control of connected and automated vehicles: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2017, 9, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanés, V.; Shladover, S.E. Modeling cooperative and autonomous adaptive cruise control dynamic responses using experimental data. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2014, 48, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shladover, S.E.; Nowakowski, C.; Lu, X.Y.; Ferlis, R. Cooperative adaptive cruise control: Definitions and operating concepts. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2489, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, M.; van Arem, B. Traffic flow impacts of converting an HOV lane into a dedicated CACC lane on a freeway corridor. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2019, 12, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammert, M.P.; Duran, A.; Diez, J.; Burton, K.; Nicholson, A. Effect of platooning on fuel consumption of class 8 vehicles over a range of speeds, following distances, and mass. SAE Int. J. Commer. Veh. 2014, 7, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, M.; Holden, J.; Lammert, M.; Duran, A.; Young, S.; Gonder, J. Potentials for Platooning in US Highway Freight Transport; Technical report; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Xing, L.; Liu, S.; Wei, X. Evaluation of the impacts of cooperative adaptive cruise control on reducing rear-end collision risks on freeways. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 98, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploeg, J.; Van De Wouw, N.; Nijmeijer, H. Lp string stability of cascaded systems: Application to vehicle platooning. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2013, 22, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeg, J.; Shukla, D.P.; Van De Wouw, N.; Nijmeijer, H. Controller synthesis for string stability of vehicle platoons. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2013, 15, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, S.E.; Wang, J.; Cao, D.; Li, K. Stability and scalability of homogeneous vehicular platoon: Study on the influence of information flow topologies. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 17, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Hu, H. Formation control for a fleet of autonomous ground vehicles: A survey. Robotics 2018, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, K.C.; Yan, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shen, H.; Chowdhury, M.; Yu, L.; Qiu, C.; Soundararaj, V. A review of communication, driver characteristics, and controls aspects of cooperative adaptive cruise control (CACC). IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 17, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badnava, S.; Meskin, N.; Gastli, A.; Al-Hitmi, M.A.; Ghommam, J.; Mesbah, M.; Mnif, F. Platoon transitional maneuver control system: A review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 88327–88347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaju, A.; Southward, S.; Ahmadian, M. Pid-based longitudinal control of platooning trucks. Machines 2023, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunagwera, A.; Zengin, A.T. A longitudinal inter-vehicle distance controller application for autonomous vehicle platoons. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarouf, A.; Bin Salamah, Y.; Ahmad, I. Decentralized Control Framework for Optimal Platoon Spacing and Energy Efficiency. Electronics 2025, 14, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, C. PD Control with Feedforward Compensation for String Stable Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control in Vehicle Platoons. Sensors 2025, 25, 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayitno, A.; Nilkhamhang, I. Distributed model reference adaptive control for vehicle platoons with uncertain dynamics. Eng. J. 2021, 25, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Yu, S. Optimal Control for Vehicle Platoon Considering External Disturbances. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Macau, China, 8–12 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Borneo, A.; Zerbato, L.; Miretti, F.; Tota, A.; Galvagno, E.; Misul, D.A. Platooning cooperative adaptive cruise control for dynamic performance and energy saving: A comparative study of linear quadratic and reinforcement learning-based controllers. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, L.; Phan, T.L.; Pham, H.T.; Hoang, T.; Le, M.t. Stability of adaptive cruise control of automated vehicle platoon under constant time headway policy. Int. J. Automot. Sci. Technol. 2024, 8, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, J.; Wu, W.; Negenborn, R.R. Cooperative distributed predictive control for collision-free vehicle platoons. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 13, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wang, M.; Alkim, T.; Van Arem, B. A robust longitudinal control strategy of platoons under model uncertainties and time delays. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 9852721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yu, S.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, S.; Yu, J.; Chen, H. Distributed MPC of vehicle platoons with guaranteed consensus and string stability. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Liu, H.X.; Li, L. Tube-based discrete controller design for vehicle platoons subject to disturbances and saturation constraints. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2019, 28, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C. Longitudinal Control of Vehicle Platoon Based on Sliding Mode Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Robotics and Control Engineering, Wuhan, China, 17–19 March 2023; pp. 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.B.; Liu, C.L.; Shan, L. Fixed-time integral terminal sliding mode control for vehicle platoon with prescribed performance. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 2024, 22, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tong, T.; Cao, J.; Li, S. Distributed sliding mode control approach with adaptive spacing policy for vehicle platoons in communication interruption scenario. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayacan, E. Multiobjective H∞ control for string stability of cooperative adaptive cruise control systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2017, 2, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viadero-Monasterio, F.; Gutiérrez-Moizant, R.; Meléndez-Useros, M.; López Boada, M.J. Static output feedback control for vehicle platoons with robustness to mass uncertainty. Electronics 2024, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, I.; Zito, G. Digital Control Systems: Design, Identification and Implementation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mohssine, C. A Comparative Study of PI, RST and ADRC Control Strategies of a Doubly Fed Induction Generator Based Wind Energy Conversion System. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2018, 8, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurraqeeb, A.M.; Al-Shamma’a, A.A.; Alkuhayli, A.; Noman, A.M.; Addoweesh, K.E. RST digital robust control for DC/DC buck converter feeding constant power load. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baziyad, A.G.; Ahmad, I.; Bin Salamah, Y.; Alkuhayli, A. Robust tracking control of a piezo-actuated nanopositioning stage using improved inverse LSSVM hysteresis model and RST controller. Actuators 2022, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihoub, Y.; Moreau, S.; Hassaine, S. Real Time Implementation of Adaptive Discrete Fuzzy-RST Speed Control and Nonlinear Backstepping Currents Control Techniques for PMSM Drive. Artif. Intell. Renew. Towards Energy Transit. 2020, 174, 361. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maarouf, A.; Ahmad, I.; Bin Salamah, Y. Two-Degree-of-Freedom Digital RST Controller Synthesis for Robust String-Stable Vehicle Platoons. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122067

Maarouf A, Ahmad I, Bin Salamah Y. Two-Degree-of-Freedom Digital RST Controller Synthesis for Robust String-Stable Vehicle Platoons. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122067

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaarouf, Ali, Irfan Ahmad, and Yasser Bin Salamah. 2025. "Two-Degree-of-Freedom Digital RST Controller Synthesis for Robust String-Stable Vehicle Platoons" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122067

APA StyleMaarouf, A., Ahmad, I., & Bin Salamah, Y. (2025). Two-Degree-of-Freedom Digital RST Controller Synthesis for Robust String-Stable Vehicle Platoons. Symmetry, 17(12), 2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122067