Prescribed Performance Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control for Nonlinear System with Actuator Faults and Dead Zones

Abstract

1. Introduction

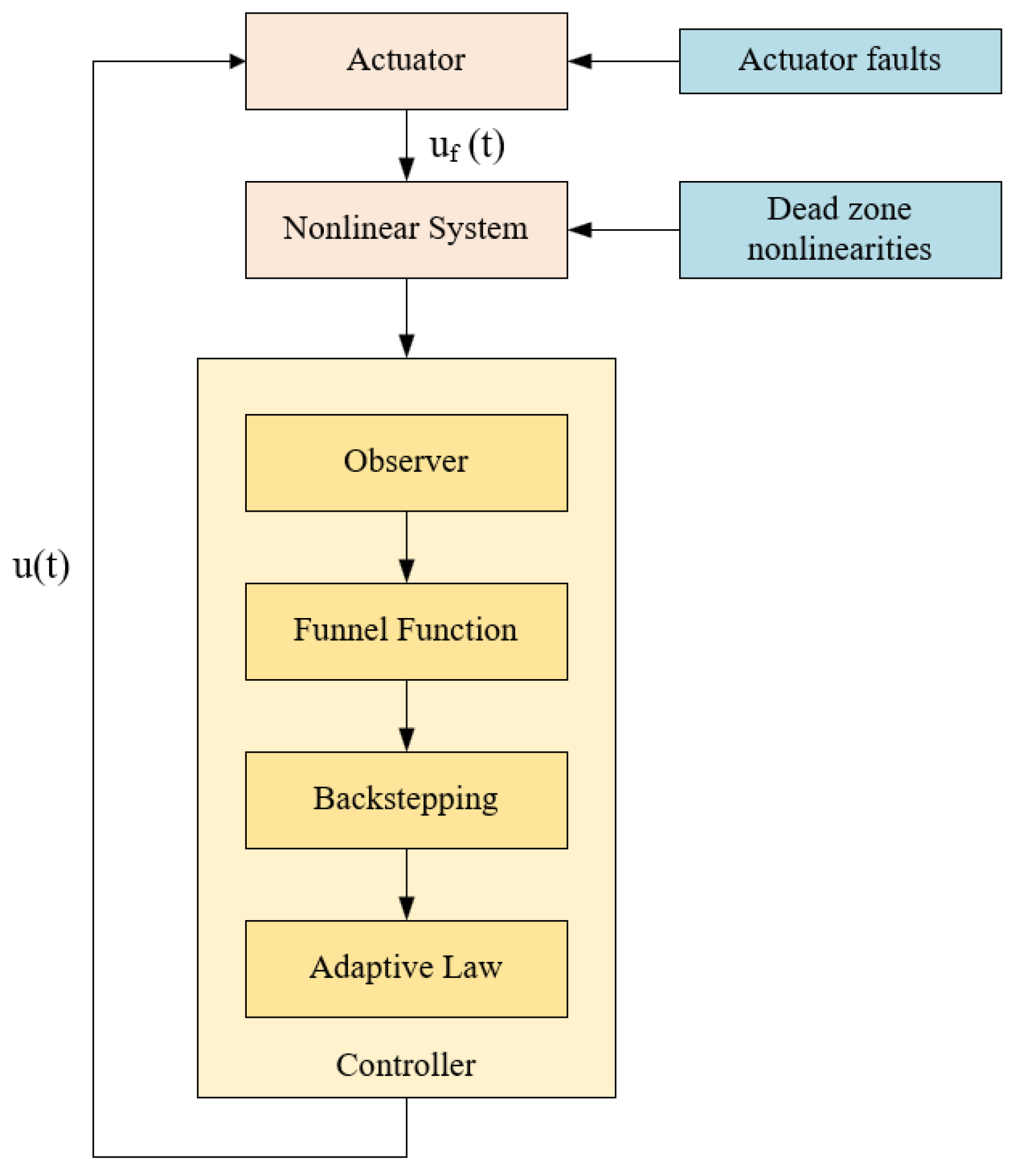

- To circumvent the obstacle caused by unmeasured state variables, an adaptive state observer is further designed. This provides the foundation for adaptive output-feedback control and prescribed performance tracking control design of high-order nonlinear systems.

- Different from [10,11,12,13,14,15] and [18,19,20] where only a single constraint problem is considered, and these methods cannot be applied to address the coupling effects of unknown actuator faults and dead zones. The bounded estimation method and adaptive technique are used to compensate for the coupling effects of unknown actuator faults and dead zones.

- By integrating a barrier Lyapunov function with a special form of funnel function, a new prescribed performance control strategy is developed. Compared with traditional prescribed performance control methods, the proposed design overcomes the dependence on initial conditions and ensures global prescribed transient performance.

2. Problem Formulation and Preliminaries

2.1. Problem Formulation

- Prescribed Performance Adaptive FTC (PPAFTC) Control Objective: For a class of time-varying nonlinear systems affected by unknown actuator faults and dead-zone nonlinearities simultaneously, the control objective of this study is to design an adaptive fault-tolerant control strategy satisfying the following:

- (1)

- All the signals of the closed-loop system are globally and uniformly bounded.

- (2)

- For arbitrary but prescribed parameters (settling time) and (precision), the tracking error satisfies for any .

- (3)

- The desired reference trajectory can be achieved.

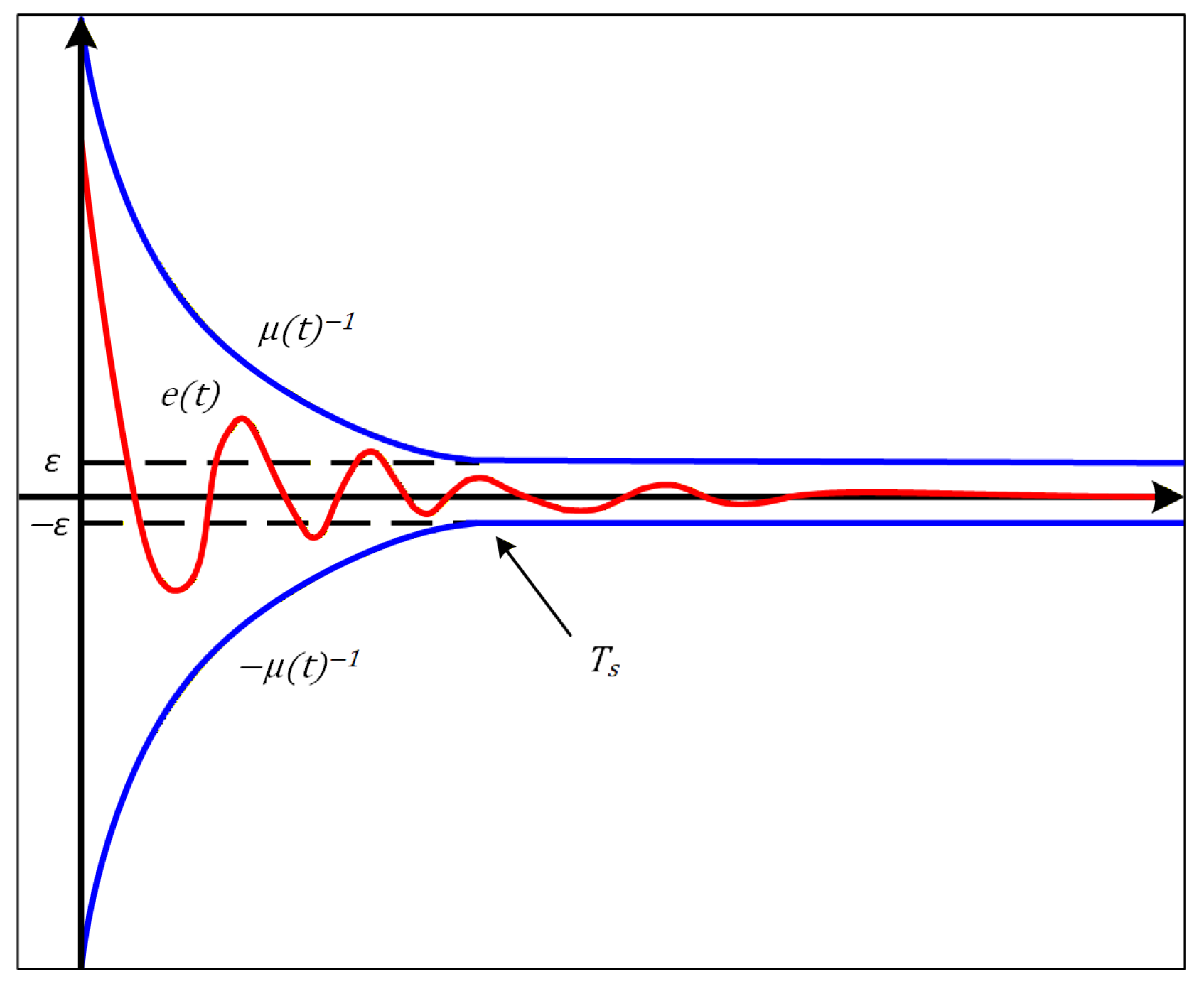

2.2. Prescribed-Time Performance Funnel Function

- (1)

- and remains positive for any ;

- (2)

- , i.e., it is bounded and has a bounded derivative;

- (3)

- There exists some for which the inequality is satisfied for all .

- (1)

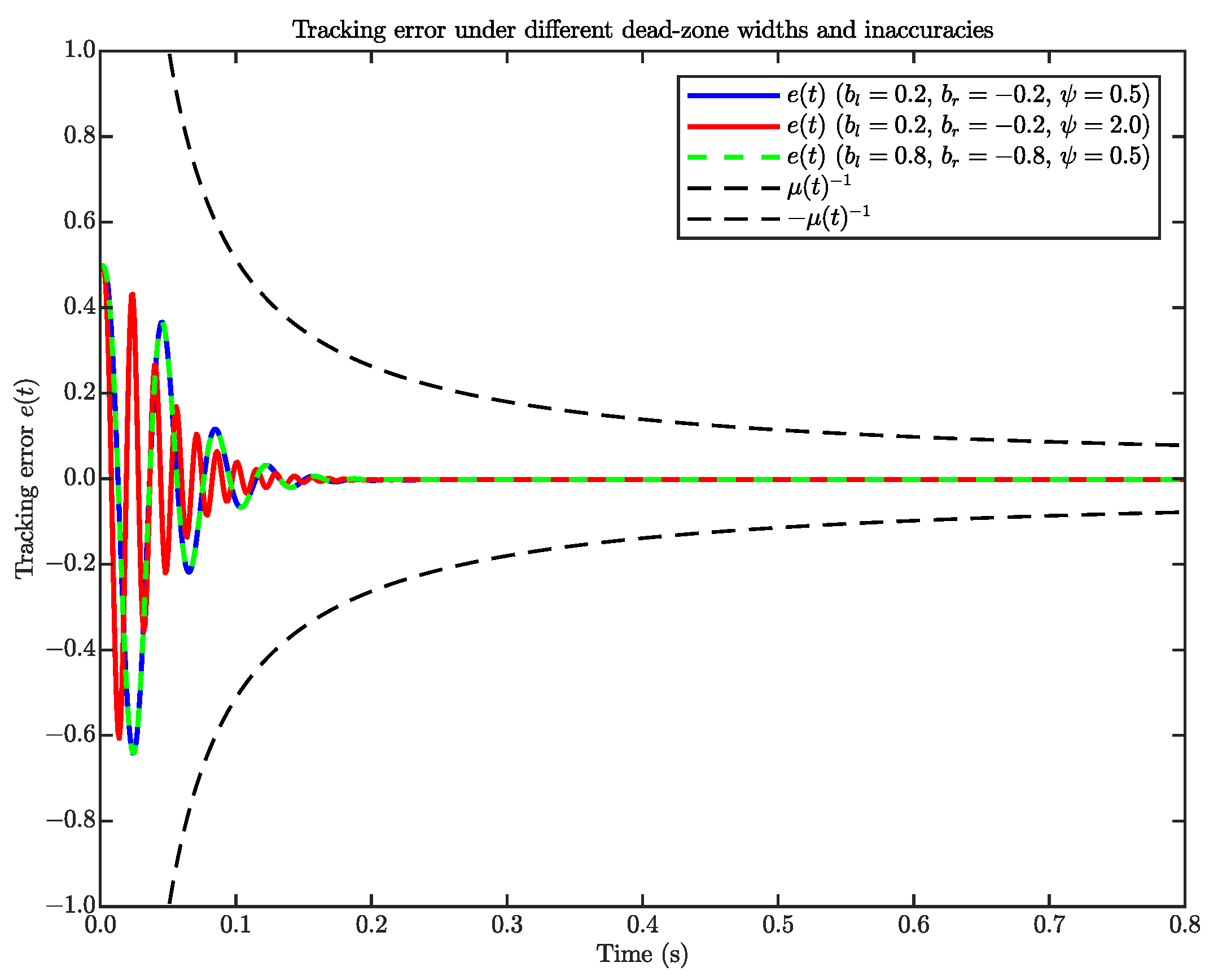

- The funnel boundary is determined by μ, which allows the transient behavior of to be constrained without forcing the error to converge to zero. It is only required that eventually remains inside the funnel boundary.

- (2)

- Since , the condition is naturally satisfied, meaning no strict limitation is imposed on the initial error. This improves the controller’s robustness to uncertain initial states.

- (3)

- The funnel is defined by parameters ε and , which are predefined and independent of system dynamics or initial conditions. This allows the controller to guarantee the desired performance within a given time interval, especially in time-sensitive scenarios.

2.3. Preliminaries

3. Control Design and Convergence Analysis

3.1. Adaptive State Observer Design

3.2. Adaptive Backstepping Controller Design

- Step 1: The dynamics of can be derived by combining (1) and the funnel function

- Step 2: The time derivative of can be derived by combining (13) and (27)

- Step i: The detailed derivation of step i is provided in Appendix A.

- Step n: By combining (10) and (27), the derivative of can be obtained

3.3. Stability Analysis

- (1)

- It can be guaranteed that all closed-loop signals are globally bounded.

- (2)

- The tracking error remains within the prescribed performance bounds imposed by the funnel function.

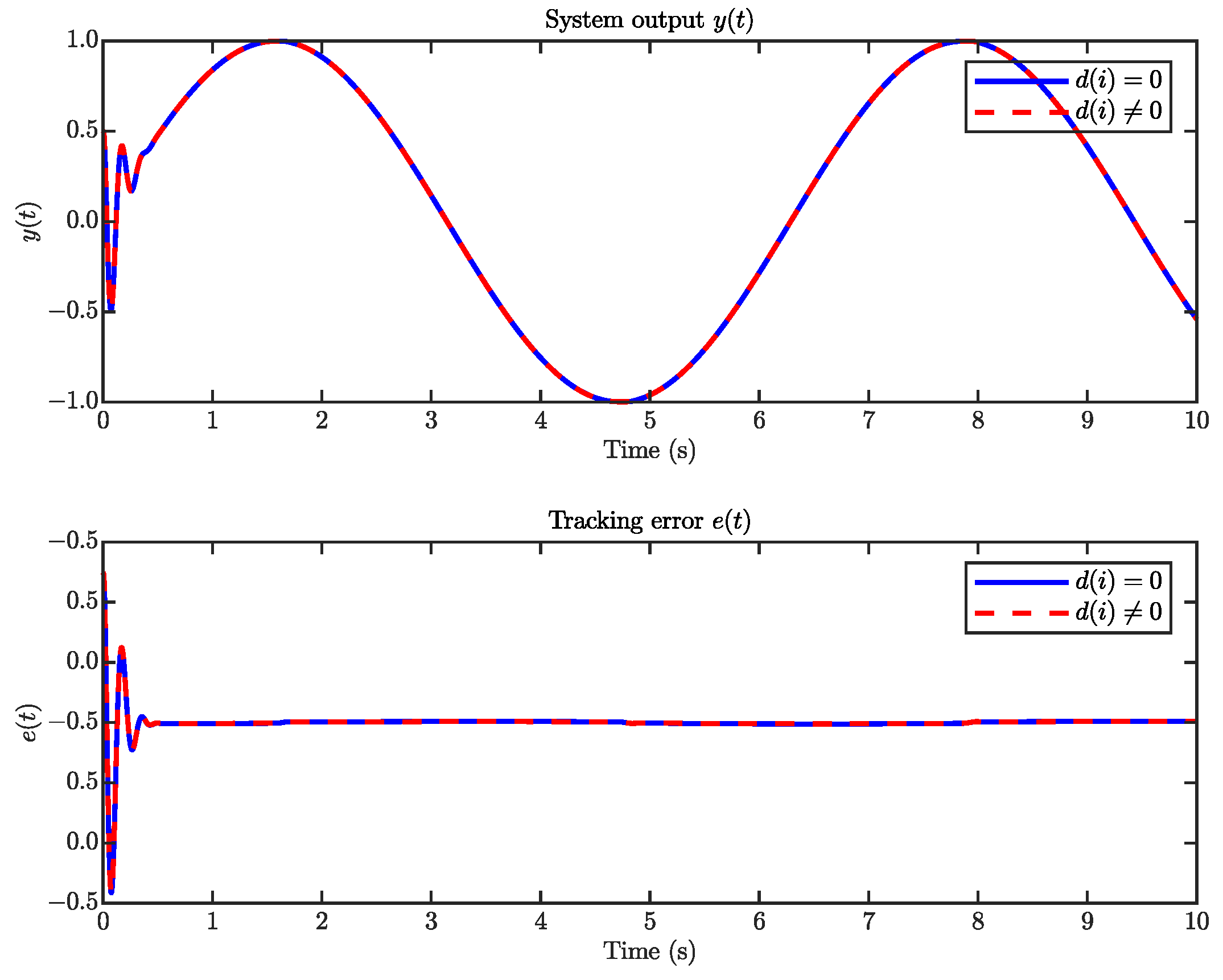

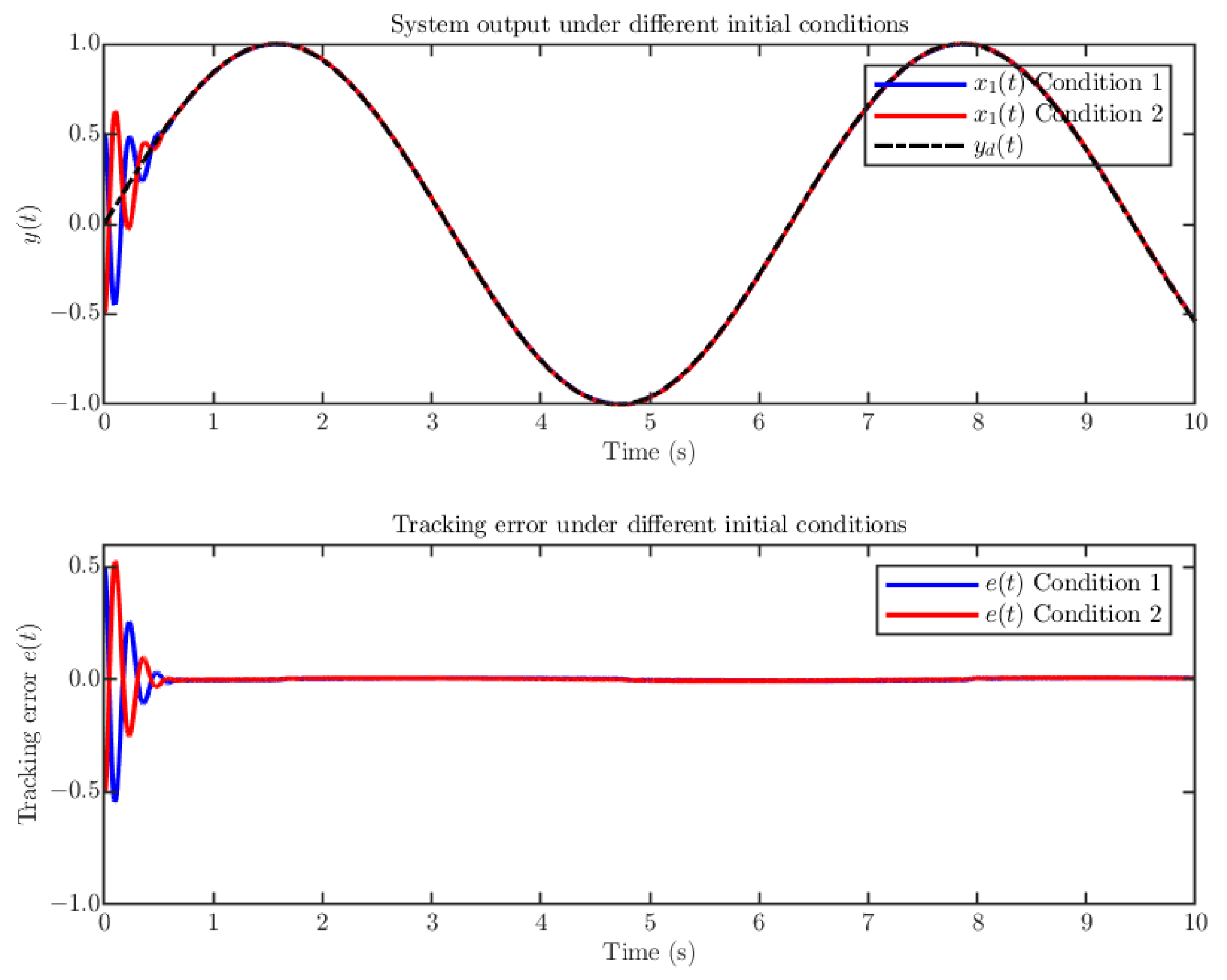

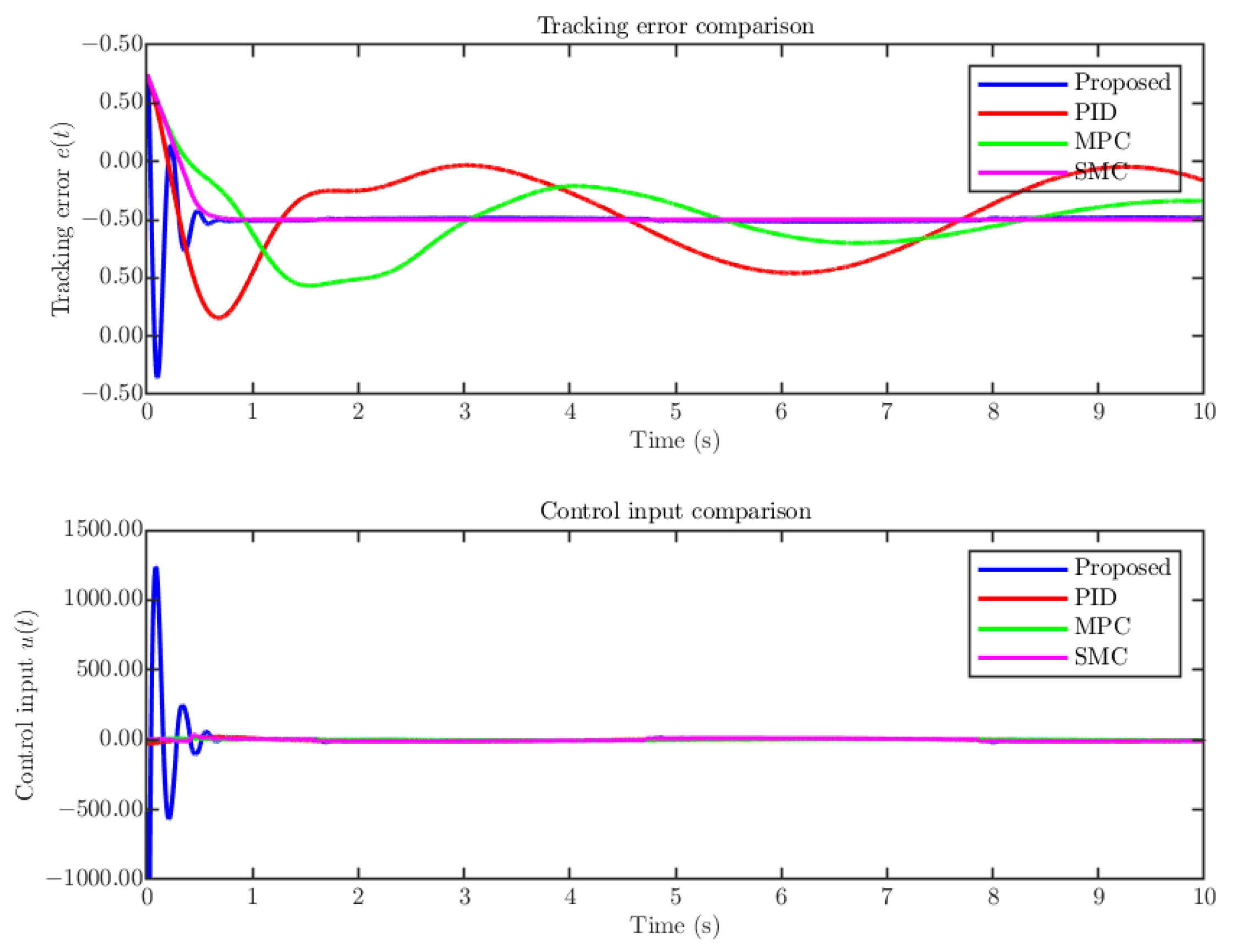

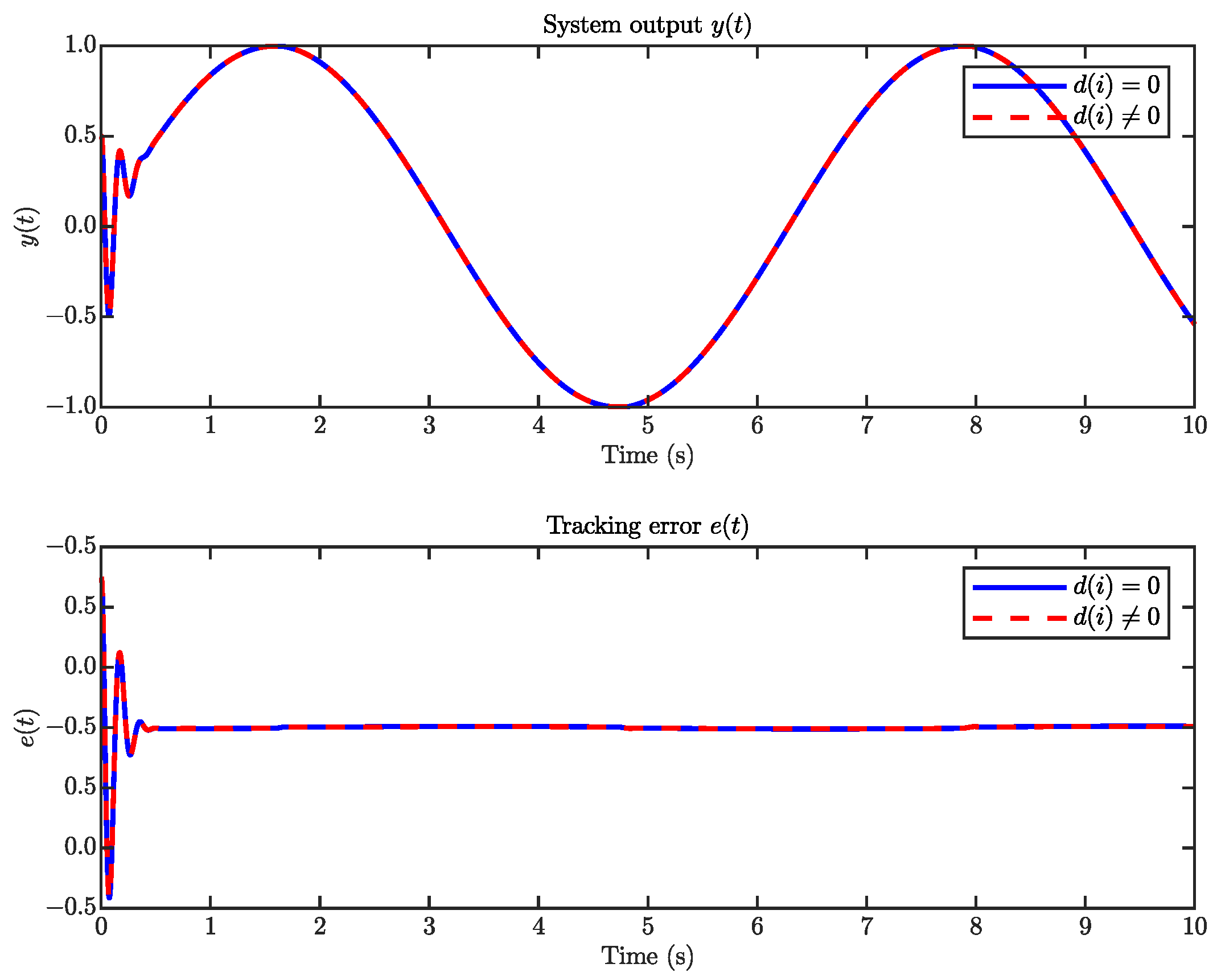

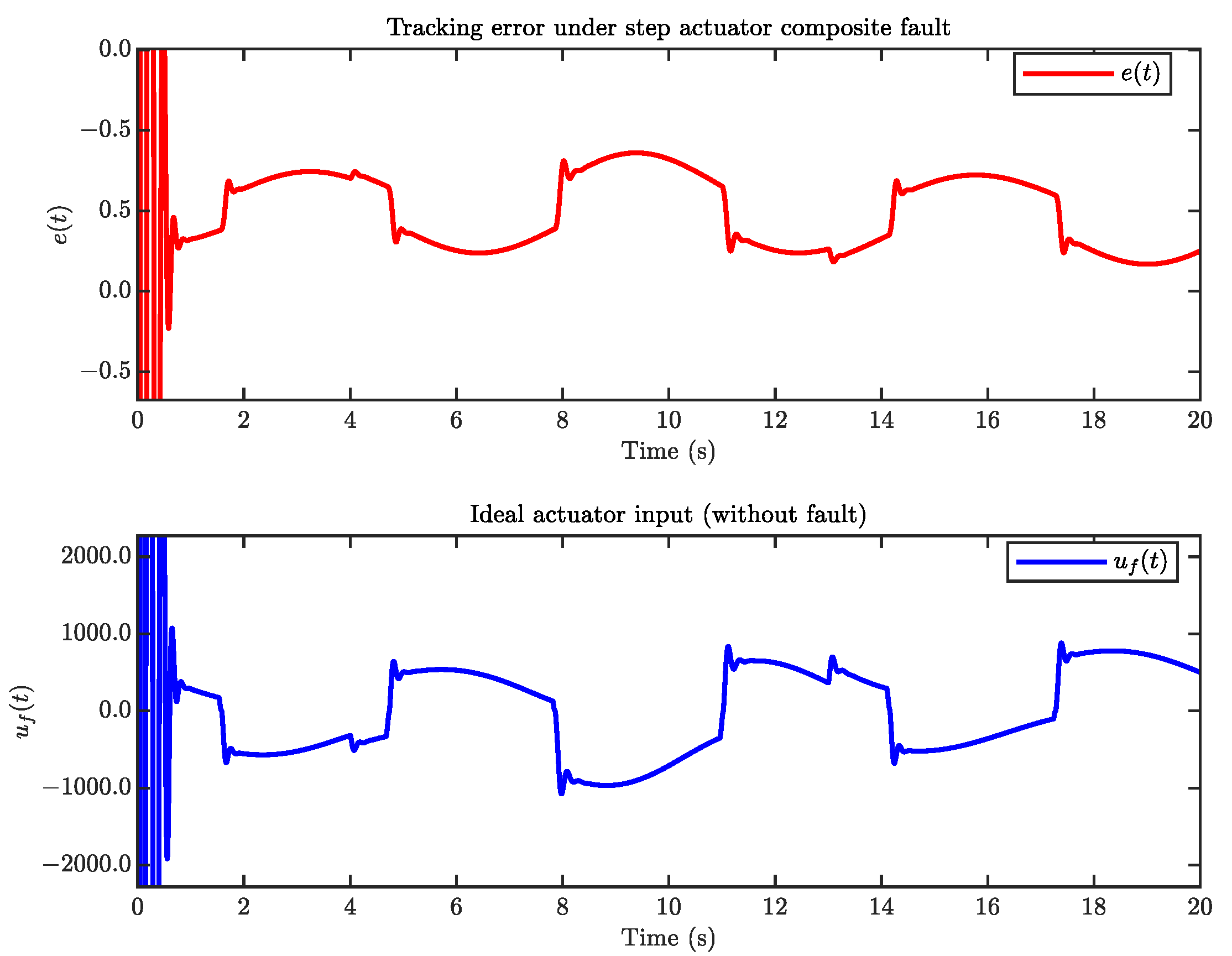

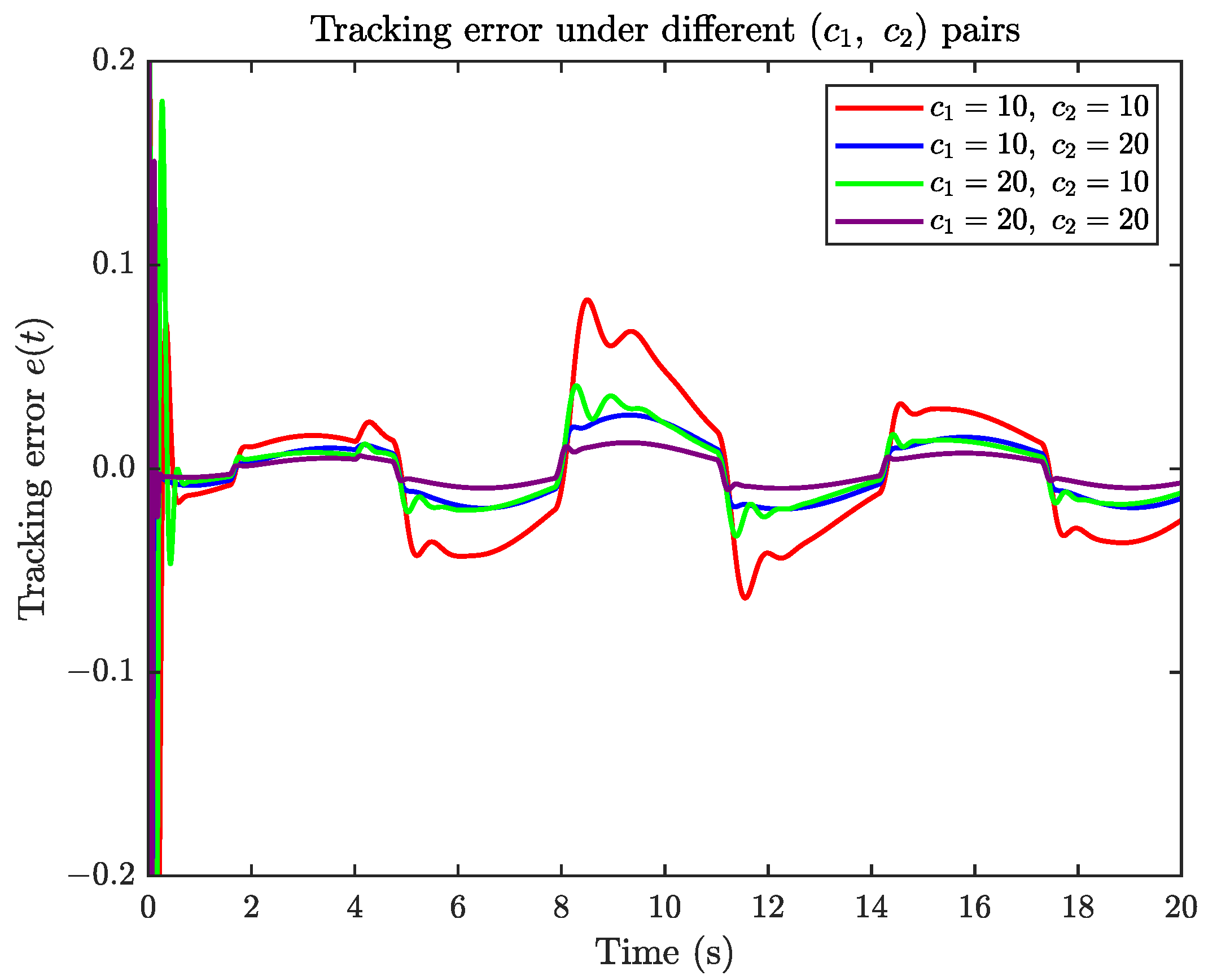

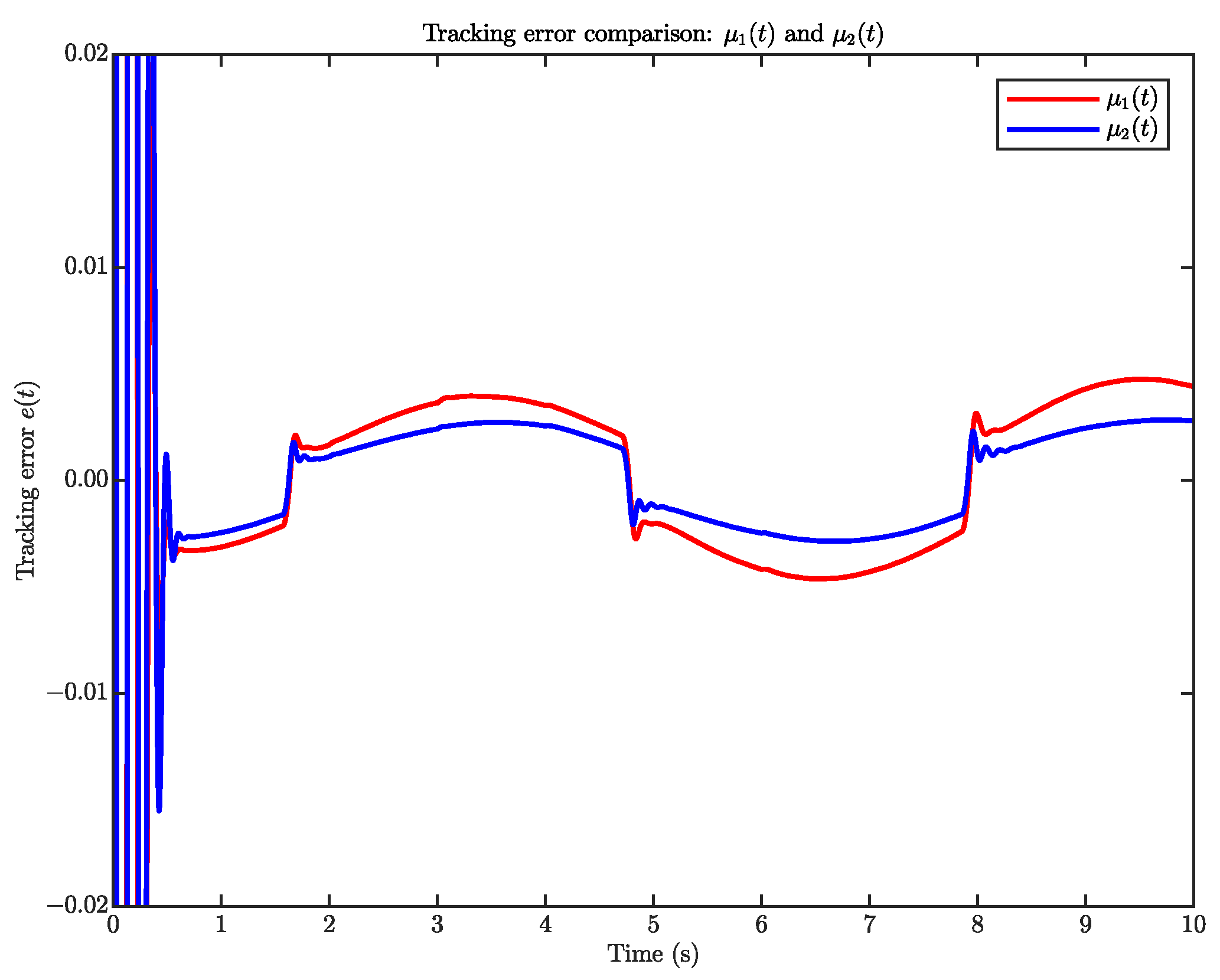

4. Simulation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Step i (): The dynamics of can be derived by combining (10) and (27)

References

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guan, X.; Hu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, S.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J.; Li, G. Direction and Trajectory Tracking Control for Nonholonomic Spherical Robot by Combining Sliding Mode Controller and Model Prediction Controller. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 11617–11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Ji, H.; Yang, P. Research on Sensorless Control System of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor for CNC Machine Tool. In Proceedings of the 2021 40th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 1592–1595. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Zhu, Q.; Zheng, W.X. Stability Analysis of Switched Stochastic Nonlinear Systems with State-Dependent Delay. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 2567–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. Event-Triggered Sampling Problem for Exponential Stability of Stochastic Nonlinear Delay Systems Driven by Lévy Processes. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2025, 70, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sain, C.; Biswas, P.K.; Satpathy, P.R.; Babu, T.S.; Alhelou, H.H. Self-Controlled PMSM Drive Employed in Light Electric Vehicle—Dynamic Strategy and Performance Optimization. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 57967–57975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ren, W.; Sun, X.M. Current-Constrained Adaptive Robust Control for Uncertain PMSM Drive Systems: Theory and Experimentation. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 4158–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sousy, F.F.M.; Alenizi, F.A.F. Optimal Adaptive Super-Twisting Sliding-Mode Control Using Online Actor-Critic Neural Networks for Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 82508–82534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ren, Y.; Mu, C.; Zou, T.; Hong, K.S. Adaptive Neural-Network-Based Fault-Tolerant Control for a Flexible String with Composite Disturbance Observer and Input Constraints. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 12843–12853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; He, W.; Hong, K.S.; Li, H.X. Boundary Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control for a Flexible Timoshenko Arm with Backlash-Like Hysteresis. Automatica 2021, 130, 109690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, M.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Polycarpou, M.M.; Parisini, T. Distributed Fault-Tolerant Control of Multiagent Systems: An Adaptive Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 31, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Yu, X.; Pan, H.; Rodríguez-Andina, J.J. Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control of Linear Motors Under Sensor and Actuator Faults. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 9829–9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Chen, Y. Robust Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control of Four-Wheel Independently Actuated Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 2882–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pan, L.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Fixed-Time Sliding Mode Tracking Control for Steer-by-Wire System with Dual-Three-Phase PMSM. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 7554–7564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Gu, T.; Zhang, K. Fault Tolerant Control of 4-Wheel Independent Drive Vehicle Subject to Actuator Faults Based on Feasible Region. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 1652–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J. Memory-Based Event-Triggered Fault-Tolerant Consensus Control of Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems and Its Applications. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 7941–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Gao, W.; Jiang, X.; Su, C.; Li, P. Two-dimensional model-free Q-learning-based output feedback fault-tolerant control for batch processes. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2024, 182, 108583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, L. Observer-Based Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Tracking Control of Nonlinear Nonstrict-Feedback Systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 29, 3022–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, D.; Alessandri, A.; Zaccarian, L. Stubborn and Dead-Zone Redesign for Nonlinear Observers and Filters. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2021, 66, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadei, G.; Astolfi, D.; Alessandri, A.; Zaccarian, L. Synchronization in Networks of Identical Nonlinear Systems via Dynamic Dead Zones. IEEE Control. Syst. Lett. 2019, 3, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Li, P.; Cai, W.C.; Song, Y.D.; Chen, H.J. Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control of Wind Turbines with Guaranteed Transient Performance Considering Active Power Control of Wind Farms. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Hu, Q.; Friswell, M.I. Fixed-Time Attitude Control for Rigid Spacecraft with Actuator Saturation and Faults. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2016, 24, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, S.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.J.; Huang, L.; Deng, Z. Adaptive Neural Network-Based Finite-Time Online Optimal Tracking Control of the Nonlinear System with Dead Zone. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Ma, H. Improved Adaptive Fuzzy Output-Feedback Dynamic Surface Control of Nonlinear Systems with Unknown Dead-Zone Output. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 29, 2122–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechlioulis, C.P.; Rovithakis, G.A. Robust Adaptive Control of Feedback Linearizable MIMO Nonlinear Systems with Prescribed Performance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 2090–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilchmann, A.; Ryan, E.P.; Sangwin, C.J. Tracking with Prescribed Transient Behaviour. ESAIM: Control. Optim. Calc. Var. 2002, 7, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilchmann, A.; Ryan, E.P.; Trenn, S. Tracking Control: Performance Funnels and Prescribed Transient Behaviour. Syst. Control. Lett. 2005, 54, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, A.; Rovithakis, G.A. A Simplified Adaptive Neural Network Prescribed Performance Controller for Uncertain MIMO Feedback Linearizable Systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 26, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechlioulis, C.P.; Rovithakis, G.A. Adaptive Control with Guaranteed Transient and Steady State Tracking Error Bounds for Strict Feedback Systems. Automatica 2009, 45, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.D.; Guo, X.G.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.L.; Park, J.H. PTNDO-based distributed active fault-tolerant control for leader–follower vehicular formation with unknown direction faults. Automatica 2025, 182, 112540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Lê, H.H.; Reis, T. Funnel Control for Nonlinear Systems with Known Strict Relative Degree. Automatica 2018, 87, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cong, J.; Bian, Y.; Han, L. Attitude-Tracking Control for Over-Actuated Tailless UAVs at Cruise Using Adaptive Dynamic Programming. Drones 2023, 7, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T. Fault-Tolerant Funnel Control for Uncertain Linear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2021, 66, 4349–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Ilchmann, A.; Ryan, E.P. Funnel Control of Nonlinear Systems. Math. Control. Signals Syst. 2021, 33, 151–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verginis, C.K.; Dimarogonas, D.V. Asymptotic Tracking of Second-Order Nonsmooth Feedback Stabilizable Unknown Systems with Prescribed Transient Response. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2021, 66, 3296–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Sun, C.; Liu, Q. Output-feedback prescribed performance control for the full-state constrained nonlinear systems and its application to DC motor system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 3898–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Xie, X.; Ahn, C.K. Adaptive fuzzy predefined accuracy control for output feedback cooperation of nonlinear multiagent systems under input quantization. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 32, 2283–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| > 0 | > 0 | ||

| > 0 | > 0 | ||

| > 0 | > 0 | ||

| > 0 | > 0 | ||

| m | m > 0 | > 0 | |

| > 0 | > 0 | ||

| 0 < < 1 | > 0 | ||

| 0 < < 1 | > 0 | ||

| 0 < < 1 | > 0.5 | ||

| 0 < < 1 | > 0 | ||

| 0 < < 1 | > 0 | ||

| > 1 | |||

| 0 < < 1 |

| Item of Comparison | [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] | [14,15] | [16,17,18,19,20,21] | [22,23,24,25,26,27,28] | [29] | [30] | This Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescribed performance control | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Unknown dead zones | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Actuator faults | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Hashimoto, S.; Kurita, N.; Nie, P.; Xu, S.; Kawaguchi, T. Prescribed Performance Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control for Nonlinear System with Actuator Faults and Dead Zones. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111915

Wang Z, Hashimoto S, Kurita N, Nie P, Xu S, Kawaguchi T. Prescribed Performance Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control for Nonlinear System with Actuator Faults and Dead Zones. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111915

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhenlin, Seiji Hashimoto, Nobuyuki Kurita, Pengqiang Nie, Song Xu, and Takahiro Kawaguchi. 2025. "Prescribed Performance Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control for Nonlinear System with Actuator Faults and Dead Zones" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111915

APA StyleWang, Z., Hashimoto, S., Kurita, N., Nie, P., Xu, S., & Kawaguchi, T. (2025). Prescribed Performance Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control for Nonlinear System with Actuator Faults and Dead Zones. Symmetry, 17(11), 1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111915